Have you ever found yourself captivated by the allure of solving a mystery? The irresistible sensation that accompanies the search for truth, like assembling the scattered fragments of a puzzle until the bigger picture emerges?

We as humans are natural seekers, forever yearning to understand and make sense of the world around us.

In this vast labyrinth of knowledge and experiences, we often stumble upon intriguing riddles, tantalizing enigmas that beckon us to embark on a quest for answers.

And it is within these quests that we unearth our most cherished treasures chest of information, helping us answer the missing pieces of the puzzles, the ones that brings clarity and enlightenment to the whole.

The puzzle, in its fragmented form, represents the gaps in our understanding, the questions that linger at the back of our minds, urging us to explore, to unravel, and to connect the dots.

It could be an elusive concept we yearn to comprehend, a forgotten chapter in the annals of history, or an unexplored parts of our own selves, concealed beneath layers of societal expectations.

While the pursuit of knowledge has been a constant companion throughout human history, the digital age has gifted us with an unprecedented advantage—the power of connectivity.

This amazing technology has and will continue to allow us to share and exchange ideas, experiences, and discoveries instantaneously.

Throughout the pages of Intwined, I’ve tried my upmost to embark upon a insightful journey, lead by my passion for discovery and the pursuit of truth, while peering through the prism of time to reveal forgotten tales that hold the key to understanding our present. With every search of the web, records office, church records and burial grounds, I am one step closer, to my very own self discovery.

As I embark upon this voyage to uncover the hidden gems and reveal the missing pieces of the puzzles in our family history, the pursuit for knowledge and the pursuit of truth, has not only discovered the most amazing charterers, their passions, strength, skills, determination, wisdom, sense of humour, not forgetting purpose, but also a deeper understanding of oneself and my place in the intricate mosaic of existence.

However this journey is constantly a reminder that the puzzle is not a static entity but one that grows and transforms with each and every new piece of information or documentation. And I’m more than happy to say, I am well on my way to putting the missing pieces of of my forbearer lives together, especially the life of my maternal 3rd Great Grandmother, Susan Mary Lagden.

I began to tell you about her life, once before, way back when I first started intwined, but the brick walls were high and those missing pieces of knowledge were unreachable. But with consistency and determination, I believe I have managed to find enough of her life puzzle pieces, so be able to share the rest of her story, and what an honour it is to do so.

So without further ado, I give you,

Discovering the Missing Piece of the Puzzle,

The Updated Life Of,

Susan Mary Lagden,

1858-1937.

Welcome to the year 1858, England.

Queen Victoria sat proudly upon the throne.

It was the 17th Parliament.

The Prime Minister was Henry Temple, 3rd Viscount Palmerston (Whig) until the 19th of February and then Edward Smith-Stanley, 14th Earl of Derby(Conservative) starting the 20th of February.

The year 1858 witnessed significant social, scientific, and political changes, contributing to the transformation of the country and its influence on the world.

These included, The Great Stink: The summer of 1858 was particularly notorious for what became known as the “Great Stink” in London. The city’s sewage system, primarily composed of open sewers and cesspits, had become overwhelmed, resulting in a horrific stench that engulfed the capital. The unbearable odor led to increased efforts to address the city’s sanitation issues, eventually leading to the construction of a modern sewer system.

The East India Company Dissolution: In 1858, the British Parliament passed the Government of India Act, which effectively ended the rule of the British East India Company in India. This act transferred the governance of India directly to the British Crown, marking the beginning of direct British control over the subcontinent as the British Raj.

The Indian Rebellion of 1857: Though the rebellion began the previous year, its impact was still felt in 1858. It was a major uprising against British rule in India, led by Indian soldiers and civilians. The British response was swift and brutal, resulting in widespread violence and casualties. The rebellion was eventually suppressed, and its aftermath led to significant changes in the administration of India.

Darwin’s “On the Origin of Species”: In November 1859, Charles Darwin published his groundbreaking book “On the Origin of Species.” However, in 1858, Darwin presented his preliminary ideas to the scientific community during a joint meeting of the Linnean Society of London and the Royal Society. This event is often referred to as the “1858 Darwin-Wallace Paper” as it included the contributions of Alfred Russel Wallace, who independently arrived at similar evolutionary theories.

The Big Ben’s Construction: The famous Big Ben clock tower, part of the Palace of Westminster in London, had its construction completed in 1858. The iconic tower, officially known as the Elizabeth Tower, was designed by architect Augustus Pugin and is recognized as one of London’s most recognizable landmarks.

Education Act 1858: The United Kingdom introduced the Education Act in 1858, aimed at expanding educational opportunities for children. It established school boards to oversee the creation and management of schools, with the goal of providing elementary education to all children.

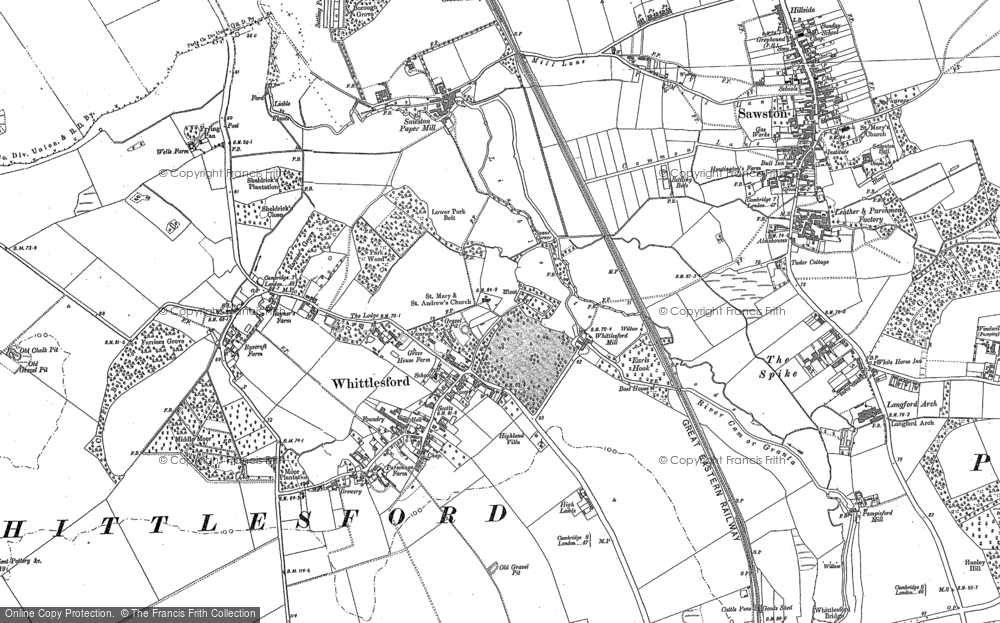

And in Whittlesford, Duxford, Cambridgeshire, England, a village situated on the Granta branch of the River Cam, seven miles south of Cambridge.

My 4th Great Grandparents, William Henry Lagden and Elizabeth Lagden nee Prime, welcomed their new born daughter, into their family of 5, (Father William, Mother Elizabeth, their children, Sarah Elizabeth Prime, Elizabeth Emma Lagden and, James Frederick Lagden.) on Saturday the 13th of November, 1858.

They named her, Susan Mary Lagden.

Elizabeth registered Susan’s birth, on the 4th of January 1859.

She gave Williams occupation as a Bricklayer and their abode as, Whittleford.

A birth in 1858 would have been quite different from the modern birthing experiences we have today. There would have been, limited medical knowledge about childbirth compared to today.

Obstetrics, the branch of medicine specializing in childbirth, was still evolving, and many medical practices were based on tradition rather than scientific evidence.

Most births during this time would have taken place at home rather than in hospitals. Midwives, who were experienced women in the community, attended to the birthing process. They relied on their knowledge and experience, often passing down techniques from generation to generation.

Pain relief options during childbirth were extremely limited. The use of anesthesia, such as chloroform or ether, was available but not widely used. Women typically relied on natural pain management techniques like breathing exercises, massages, and the support of family and friends.

In the 19th century, the risk of complications during childbirth was significantly higher compared to modern times. Infections, hemorrhages, and obstructed labor were common and could result in the loss of both mother and child.

Maternal mortality rates were relatively high, especially in cases where medical intervention was necessary.

Prenatal care as we know it today was virtually non-existent during this period. Expectant mothers mainly relied on traditional remedies and advice from midwives or experienced women in their community.

Women gave birth surrounded by a network of female relatives and friends who provided support and assistance.

Of course, like childbirth today, childbirth in 1858 would also have been influenced by cultural and social factors.

William and Elizabeth, baptised, Susan Mary, on Sunday the 27th of February, 1859, at St Mary’s and St Andrews, Whittlesford, Cambridge, England.

The first record of the church in Whittlesford dates from 1217, but there has certainly been a church on the present site since at least Norman times. The church has been dedicated to Saint Andrew since medieval times, and from the 16th century the dedication to Saint Marywas added.

The present building consists of a chancel and nave with south chapel, south aisle and a central tower. It is built of field stones with ashlar dressings. The north wall of the nave dates from the 11th century Norman church as well as the base of the tower and several south windows. The chancel dates from the 13th century and the south chapel from the 15th century. The church contains a square 13th century font. A late 12th or early 13th-century Sheela na Gig can be observed on a high window arch of the church, accompanied by an ithyphallic male figure. Between the 17th and 19th centuries, the church had strong links with Jesus College, Cambridge and vicars were frequently fellows of the college. It is a Grade I listed building. A Primitive Methodist chapel was built in the village in the early 19th century, but was closed before the end of the century. A Congregational chapel was built in 1903.

During the Victorian era in England, baptisms were significant events in the lives of families and communities.

Baptisms during this time were primarily religious ceremonies conducted by the Church of England. They were typically held in the local parish church and officiated by a clergyman.

Baptisms generally took place shortly after the birth of the child, usually within a few weeks or months. Delaying a baptism was uncommon, as it was believed that an unbaptized child was vulnerable to spiritual harm.

The child being baptized would typically be dressed in a white or cream-colored christening gown. These gowns were often heirlooms passed down through generations and were worn by both boys and girls. They symbolized purity and were meant to reflect the solemnity of the occasion.

Similar to modern practices, the child would have godparents, usually two or more. Godparents were typically chosen from among close friends or relatives and held a significant role in the child’s life. They were expected to provide spiritual guidance and support.

The baptism ceremony itself would involve several religious rituals. The clergyman would recite prayers and blessings, perform the baptismal rite, and anoint the child with holy water.

The godparents and parents would make promises on behalf of the child, renouncing evil and affirming their commitment to raising the child in the Christian faith.

Baptisms were often community events, with family, friends, and members of the local community in attendance. The congregation would witness the baptism and participate in hymns and prayers during the ceremony.

Following the baptism, it was common for the family to host a reception or a small gathering to celebrate the occasion. This could be held at the family’s home or at a nearby venue, where guests would enjoy refreshments and to socialise.

Of course, practices and traditions would like today, vary depending on factors such as social status, geographical location, and religious belief’s.

Jumping forward the the year 1861, the Monarch was still Queen Victoria. It was the 18th Parliament and the Prime Minister was Henry John Temple, 3rd Viscount Palmerston (Liberal).

The London Metropolitan Police introduces the first standard police whistle, known as the Acme Thunderer. It becomes a widely used tool for law enforcement officers.

The British Parliament passes the House of Commons (Redistribution of Seats) Act 1861, which redistributes parliamentary seats in England and Wales based on population changes.

The University of London awards its first Bachelor of Science degree, making it the first British university to offer degrees in scientific subjects. The Great Comet of 1861, also known as Comet C/1861 J1, reached its closest approach to Earth. It became visible to the naked eye and attracts significant attention from astronomers and the general public.

The first issue of the magazine “Punch, or The London Charivari” was published. It gained popularity for its satirical humor and political commentary.

The Prince of Wales, Albert Edward (later King Edward VII), contracted typhoid fever whilst on a visit to Ireland. His illness raised concerns about the future of the British monarchy.

The London Necropolis railway station, a dedicated station for funeral trains, opened in Brookwood Cemetery, Surrey. It allowed for efficient transportation of the deceased and mourners.

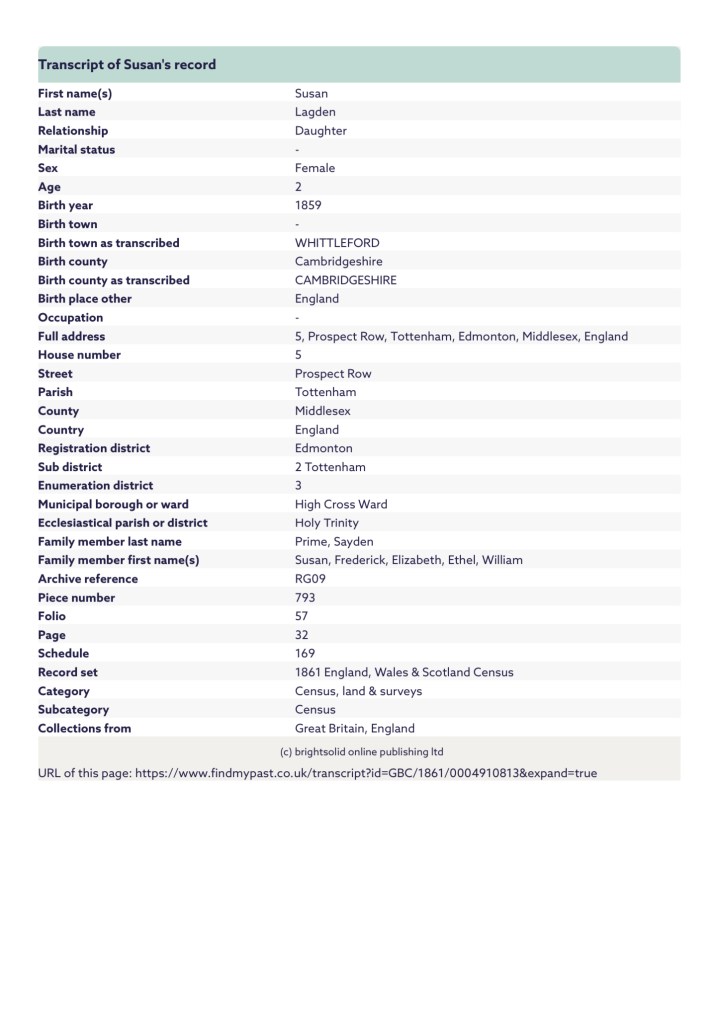

And the 1861 census was taken on the 7th April, which shows Susan, her Father William, her Mother Elizabeth, her siblings Sarah, Elizabeth and James Frederick and her Grandmother, Susan Prime nee Marshall, residing at, 5 Prospect Row, Tottenham, Middlesex, England.

James was listed/named as Frederick.

William was working as a, Journeyman Bricklayer.

The 1861 Census was conducted in several countries around the world.

In the United Kingdom, the 1861 Census was conducted under the authority of the General Register Office (GRO). The GRO was responsible for collecting and compiling vital statistics, including population data. The census was conducted on the night of Sunday, April 7, 1861.

The process of taking the census involved enumerators visiting every household and collecting information from the residents. Enumerators were appointed and assigned to specific areas or districts within their respective regions. They were typically schoolteachers, constables, or other trusted individuals within the community.

Prior to the census night, the enumerators distributed schedules to each household. The schedules were forms that residents were required to complete with information about themselves and their households. The schedules included details such as name, age, sex, occupation, place of birth, and marital status of each individual residing in the household.

On the census night, the enumerators would visit each household to collect the completed schedules. They would check the accuracy and completeness of the information and address any questions or clarifications that may have arisen. The enumerators had to exercise caution to ensure that no houses were missed or counted twice.

Once the enumerators had collected all the schedules, they would return them to the central authority, the General Register Office. There, the information from the schedules would be compiled, tabulated, and analyzed to produce statistical reports on the population of the country.

It’s worth noting that the 1861 Census was the first to include a comprehensive set of occupation categories, providing valuable insights into the industrial and occupational structure of the population.

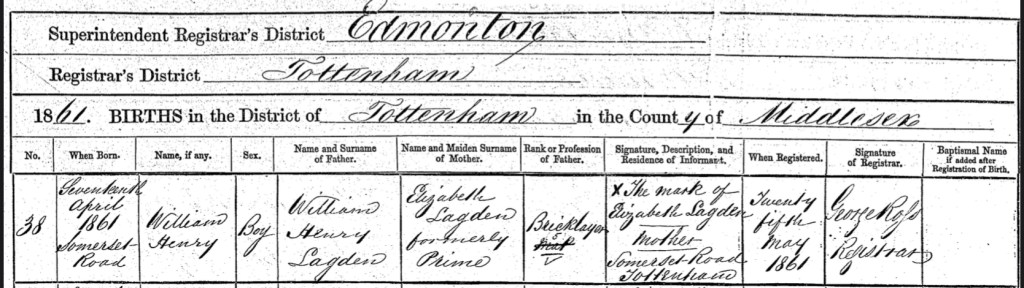

Susan’s brother, William Henry Lagden, was born on Wednesday the 17th April 1861, their home in, Somerset Road, Tottenham, Middlesex, England. Susan’s mum, Elizabeth, registered Williams birth in Edmonton, on Saturday the 25th May 1861.

Elizabeth left her mark.

She gave her husbands Williams occupation as a Bricklayer.

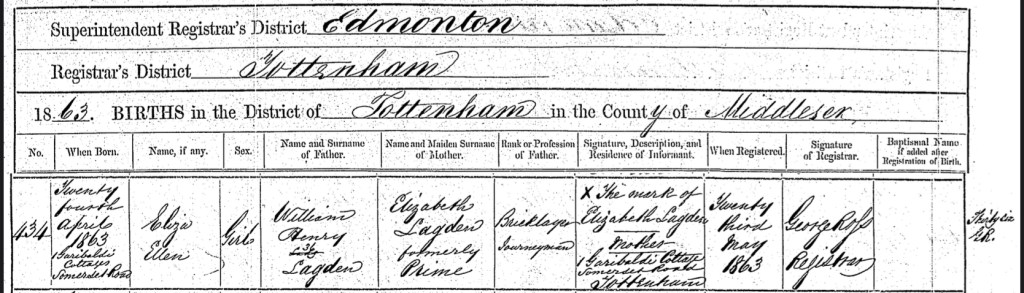

A few years later, in 1863, Susan’s sister, Eliza Ellen Lagden, was born on Friday the 24th of April 1863, at their home, 1 Garibaldi Cottage, Tottenham, Edmonton, Middlesex, England.

Susan’s mum, Elizabeth, registered Eliza’s birth in Edmonton, on Saturday the 23rd of May 1863.

Elizabeth left her mark.

She gave her husbands Williams occupation as a Bricklayer, Journeyman.

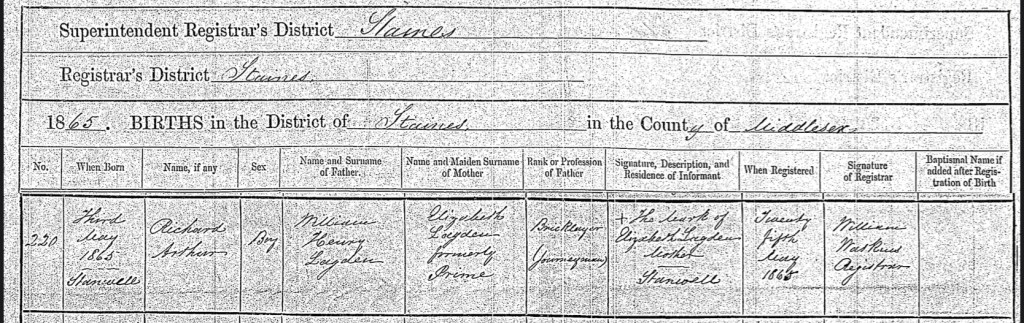

On Wednesday the 3rd of May, 1865, Susan’s brother, Richard Arthur Lagden, was born on Wednesday the 3rd of May 1865, at Stanwell, Staines, Middlesex, England. Elizabeth registered Richards birth on the 25th of May 1865 in Staines. She gave her husband William’s occupation as a Bricklayer Journeyman and their abode as Stanwell. Elizabeth left her mark.

Another sister joined the Lagden Clan, in 1867, in Sunbury, Middlesex, England.

Emily Caroline Lagden, was born on the 1st of October 1867, Sunbury, Staines, Middlesex, England.

Susan’s mum, Elizabeth, registered Emily’s birth in Staines, on the 7th of November 1867.Elizabeth left her mark.

She gave her husbands Williams occupation as a Bricklayer.

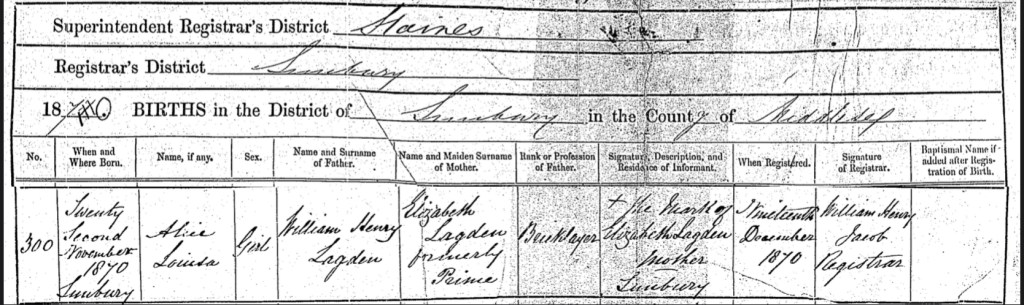

Susan’s sister, Alice Louisa Lagden, was born on Tuesday the 22nd of November, 1870, at Sunbury, Staines, Middlesex, England.

Susan’s mum, Elizabeth, registered Alice’s birth on Monday the 19th of December 1870, In Sunbury, Staines.

Elizabeth left her Mark.

She gave her husband William’s occupation as a Bricklayer.

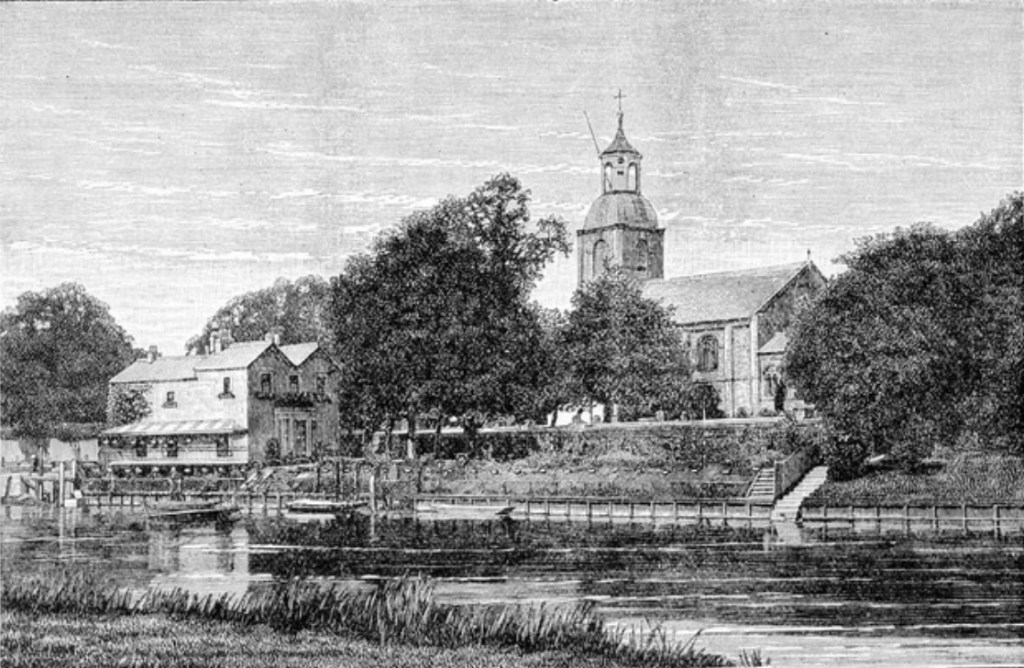

Alice Louisa Lagden, was baptised on the 3rd Jan 1871 at St Mary’s Church, Sunbury on Thames, Staines, London, England.

St Mary’s Church, was built originally in the medieval period, to which its foundations date. It was entirely rebuilt in 1752, designed by Stephen Wright (Clerk of Works to Hampton Court Palace); it has a tall apsidal (dome-like) chancel with a south chapel and western extensions to aisles added in extensive remodelling designed by architect Samuel Sanders Teulon in 1857. A solitary central monument in the church itself is to Lady Jane Coke (died 1761), stained glass and a vestry much extended in the early 20th century. It is a listed building in the mid-category, Grade II*

Jumping forward to the year 1871, Queen Victoria was sat proudly upon the throne. It was the 20th Parliament and the Prime Minister was William Ewart Gladstone(Liberal).

The United Kingdom and Brazil signed the Treaty of Montevideo, establishing diplomatic relations between the two countries.

The Bank of Ireland Act 1871 was passed, creating the Bank of Ireland as a distinct legal entity separate from the Bank of England.

The Bank Holidays Act 1871 was enacted, designating four official bank holidays in England, Wales, and Ireland: Easter Monday, Whit Monday, First Monday in August, and Boxing Day.

The University Tests Act 1871 was passed, allowing students at Oxford, Cambridge, and Durham universities to affirm or declare their belief in the Thirty-Nine Articles of the Church of England instead of taking religious tests.

The Football Association (FA) was founded in England, becoming the governing body for association football in the country. It established rules and regulations for the game.

The Trade Union Act 1871 was passed, granting legal recognition to trade unions in the United Kingdom and protecting their funds from legal claims.

The Treaty of Washington was signed between the United Kingdom and the United States, resolving various disputes related to the American Civil War and establishing international arbitration as a means of settling future conflicts.

And the 1871 census was taken. The census was the sixth national census conducted in the country. It took place on the night of April 2, 1871, and aimed to collect comprehensive data about the population and housing across England, Wales, Scotland, and Ireland.

The enumeration process involved the distribution of household schedules to each dwelling, which were then filled in by the head of the household or their representative.

The 1871 census recorded a population of approximately 32.5 million in England and Wales, 3.4 million in Scotland, and 5.4 million in Ireland. Noteworthy events and developments during this time period include:

The census captured the effects of the ongoing industrial revolution, which had transformed large parts of the country. It revealed the growing concentration of population in urban areas and the emergence of industrial towns and cities.

The population of major cities, such as London, Manchester, Birmingham, Glasgow, and Edinburgh, continued to grow rapidly. The census provided valuable information on the size, composition, and living conditions of these urban populations.

The census collected data on occupations, literacy rates, birthplaces, and relationships within households. It shed light on the diverse social and economic circumstances of individuals across different regions and social classes.

The census recorded information about migration patterns within the UK and immigration from other countries. It helped in understanding the movement of people and the impact of migration on local populations.

The census data allowed for the analysis of demographic trends, including birth rates, death rates, and population growth. This information was crucial for policy planning, public health initiatives, and the allocation of resources.

The 1871 census also collected data on topics such as housing conditions, education, religion, and language. It played a significant role in providing a comprehensive snapshot of the population and societal changes during the late 19th century.

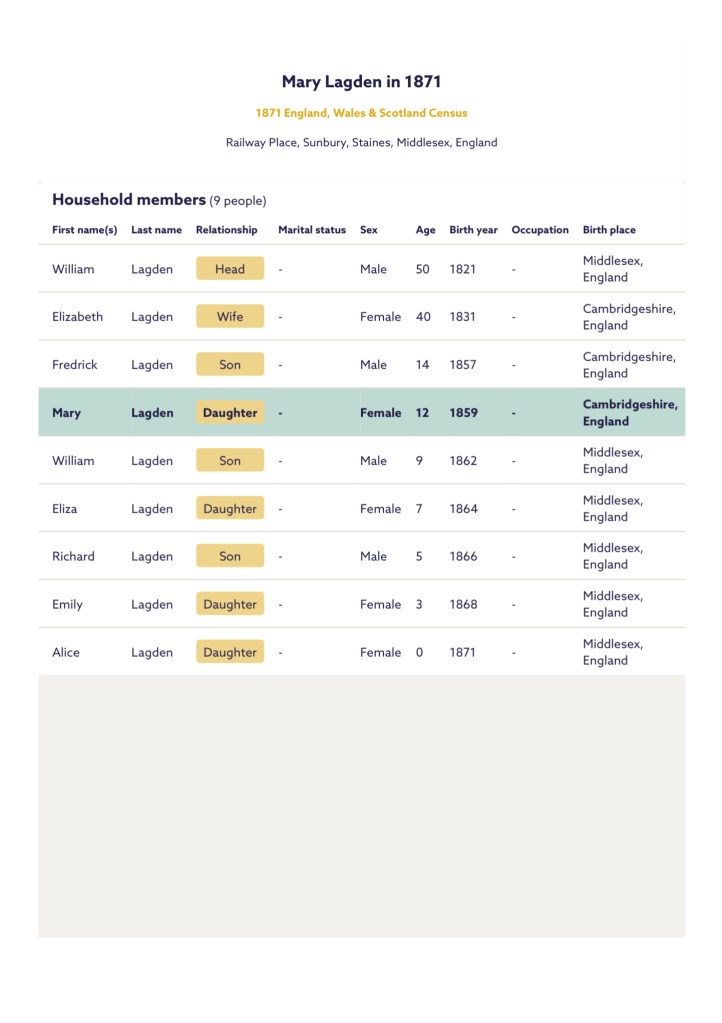

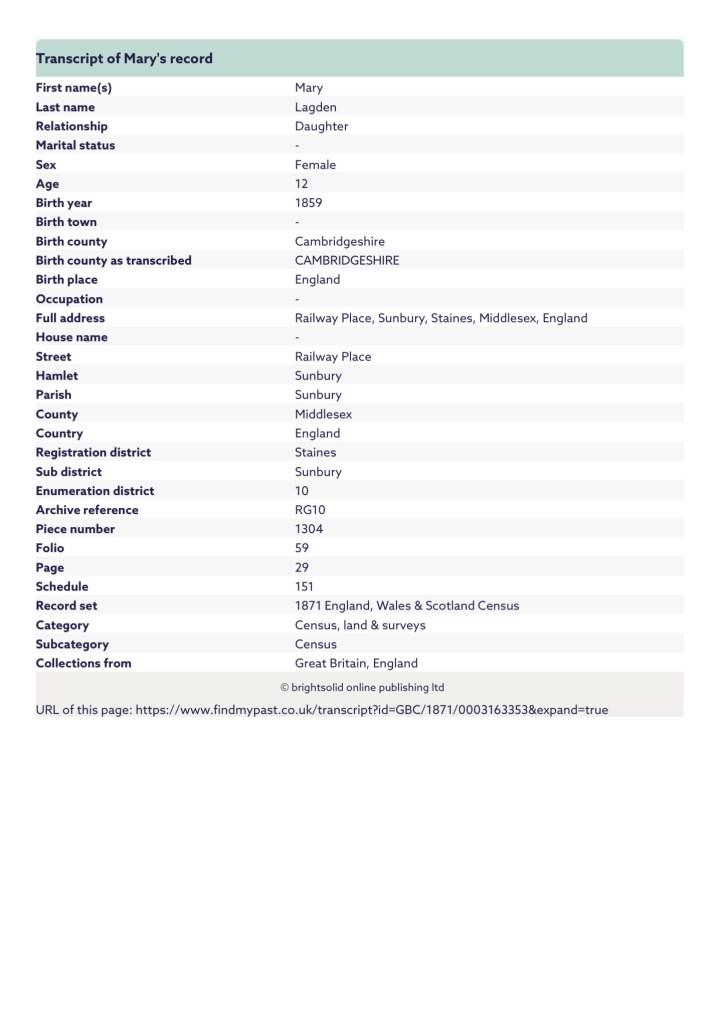

The 1871 census shows, Susan and the Lagden family, William, Elizabeth and their childen, Frederick, Eliza, William, Richard, Emily and Alice, were residing at, Railway Place, Sunbury, Middlesex, England.

William, was working as a Bricklayer.

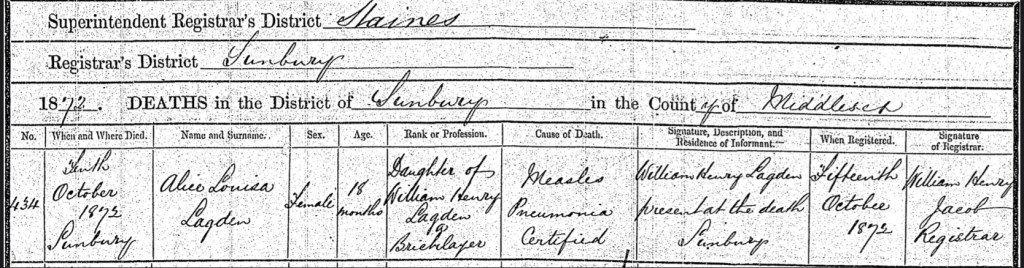

Just a short while after, the family were shook to the core, when Susan’s sister, 18 months old, Alice Louisa Lagden, sadly died from Measles Pneumonia, on Thursday the 10th of October 1872, at Sunbury, Staines, Middlesex, England.

Her father William Henry Lagden, a Bricklayer, was present and registered Alice’s death on Tuesday the 15th of October 1872 in Sunbury, Staines.

Alice Louisa Lagden, was laid to rest on Saturday the 19th October 1872 at Sunbury, Middlesex, England. I assume in, Sunbury Cemetery.

A funeral and burial in England in 1872 would have followed certain customs and traditions prevalent during that era.

When a person passed away, family members would notify the local clergy or a funeral director. The death would be registered with the local registrar of births, deaths, and marriages.

The funeral director/undertaker, would assist the family in making funeral arrangements.

They would handle logistics such as transporting the deceased, providing coffins, and organizing the funeral service.

The deceased would be laid out at home, and family and friends would visit to pay their respects. The body might be displayed in a simple wooden coffin, with the deceased dressed in their best attire. Mourners would offer condolences to the family and spend time reflecting on the deceased’s life. On the day of the funeral, the coffin would be transported to the church or cemetery in a hearse, pulled by horses. The family and mourners would walk behind the hearse in a solemn procession. The route might pass through the streets, allowing people to pay their respects as the procession passed by.

The funeral service would typically be held in a local church, led by a clergyman or minister. The service would include prayers, hymns, readings from the Bible, and a eulogy. The clergy would offer comfort and words of solace to the bereaved family.

Following the service, the coffin would be carried to the gravesite in the cemetery. A brief graveside ceremony would be conducted, during which final prayers would be said, and the deceased would be committed to the earth. The coffin would be lowered into the grave, and mourners might drop flowers or handfuls of soil as a final farewell.

It was customary for mourners to wear black attire as a sign of respect for the deceased. The immediate family might wear mourning attire for an extended period, with widows often wearing black for a year or more.

After the funeral, a mourning period would follow, during which the family would observe certain customs to express their grief. This could include refraining from social events and wearing specific clothing or armbands to indicate mourning.

Over time, gravestones or memorials would be placed at the gravesite, typically inscribed with the name, dates of birth and death, and sometimes a short epitaph or message.

Of course funeral practices in 1872 could vary depending on religious beliefs, regional customs, and individual family preferences.

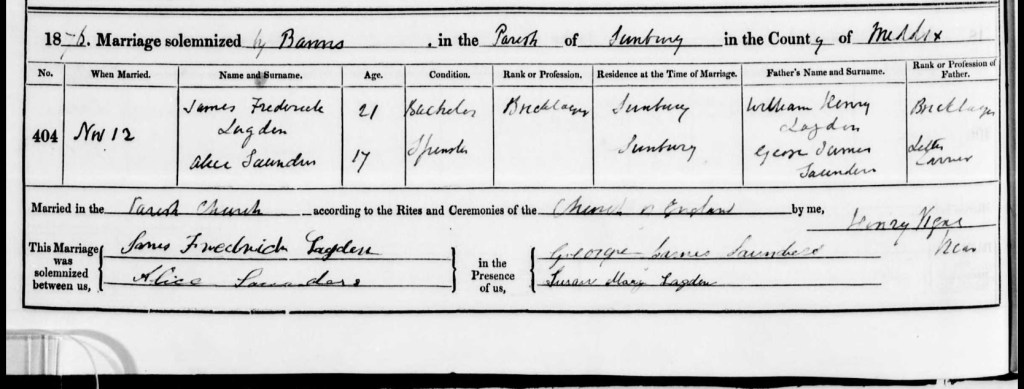

Jumping forward to the year 1876, Susan’s bother, 21 year old, bachelor, Bricklayer, James Frederick Lagden married 17 year old, spinster, Alice Saunders, daughter of, George James Saunders, a Letter Carrier, on Sunday the Sunday 12th November 1876, at St. Mary’s Church, Sunbury, Middlesex, England.

Susan and Alice’s father, George James Saunders were their witnesses. James and Alice were both residing in Sunbury at the time of their marriage.

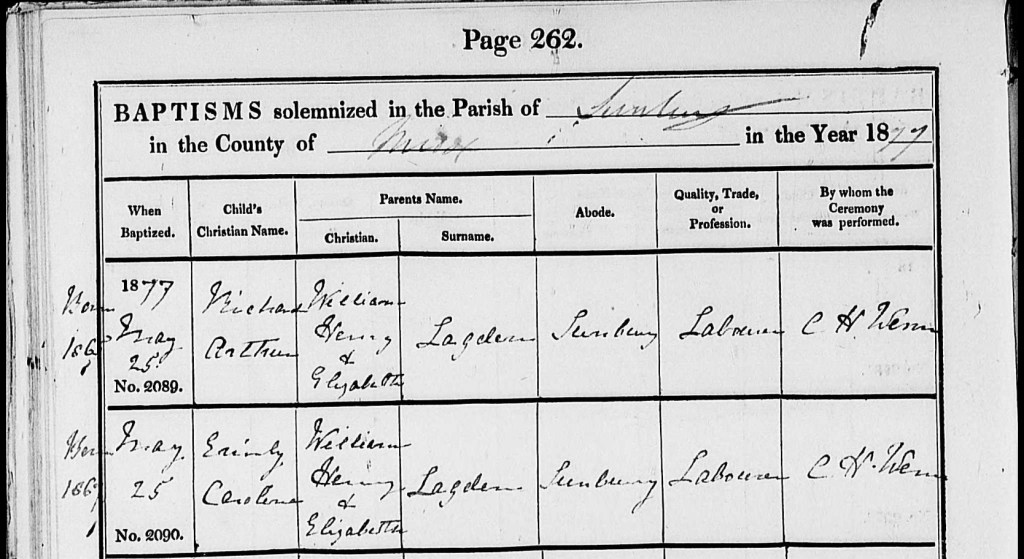

The following Year, Susan’s siblings, Eliza, Richard and Emily, were baptised on Friday the 25th of May, 1877, at St Mary’s Church, Sunbury, Middlesex, England.

Their father William, occupation was given as a labourer and their abode as, Sunbury.

Later that year, Susan’s sister, 21 year old spinster, Elizabeth Emma Lagden, married 19 year old bachelor, William Kimpton, a Labourer, son of Seaman, Thomas Kimpton, on Sunday the 2nd of September, 1877, at St Mary’s Church, Sunbury, Surrey, England.

Their witnesses were, Eliza and Frederick Lagden.

Elizabeth and William were both residing in Sunbury, at the time of their marriage.

It wasn’t long until Susan fell in love with a man called Alfred Kirby, the son of Thomas Kirby and Ellen Tilley.

Alfred was a carman and I wonder if that is how they met?

I can picture it quite clearly in my mind. Their eyes meeting and their hearts all a flutter.

Was it love at first sight or did Alfred have to woo her?

I wonder where they went on their first date? How long it was before Alfred asked Susan to marry him? And how did he proposed? Did he ask Susan’s father William, for his daughter hand in marriage? And did Alfred get down on one knee?

If only historical records showed us these details, how wonderful would that be. ❤️

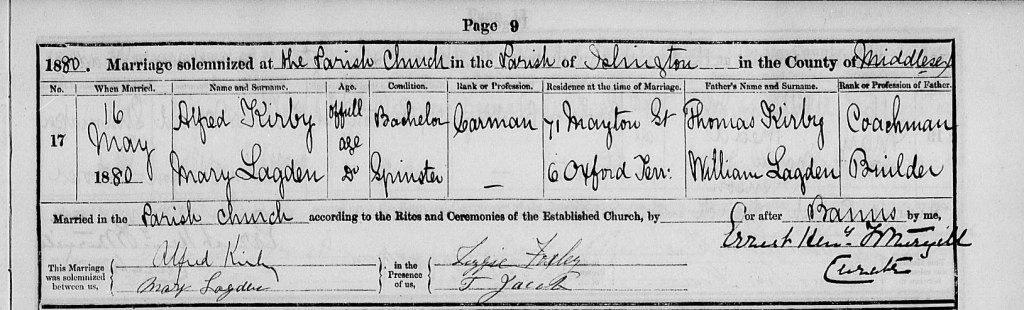

Susan and Alfreds, marriage banns, were called by Rev D Wilson, Vicar, on Sunday the 11th, of April 1880 and on Sunday the 18th and 25th April 1880, by E. H. Forthergile, at St Mary’s Church, Islington, Middlesex, England.

Susan Mary, and Alfred Kirby, took their vows, on Sunday the 16th of May, 1880, at St Mary’s, The Parish Church of Islington, Middlesex, England.

Susan used her middle name Mary and was of full age, as was Alfred.

Alfred was working as a Carman.

His father Thomas Kirby, was a Coachman and Susan’s father, William Henry Lagden, was a Builder.

Alfred’s residents was, 71 Mayton Street, Holloway, Islington, Middlesex, England.

Susan was residing at, Number 6 Oxford Terrace, Islington.

Their witnesses were, T Jacob and Lizzie Foyley.

So what would their wedding have possibly looked like?

The wedding day wasthe most important event in a Victorian girl’s life. It is the day her mother has prepared her for from the moment she was born. The Victorian girl knew no other ambition. She would marry, and she would marry well.

The wedding itself and the events leading up to the ceremony are steeped in ancient traditions still evident in Victorian customs. One of the first to influence a young girl is choosing the month and day of her wedding. June has always been the most popular month, for it is named after Juno, Roman goddess of marriage. She would bring prosperity and happiness to all who wed in her month. Practicality played a part in this logic also. If married in June, the bride was likely to birth her first child in Spring, allowing her enough time to recover before the fall harvest.

June also signified the end of Lent and the arrival of warmer weather. That meant it was time to remove winter clothing and partake in one’s annual bath. April, November and December were favored also, so as not to conflict with peak farm work months. October was an auspicious month, signifying a bountiful harvest. May, however, was considered unlucky. “Marry in May and rue the day,” an old proverb goes. But “Marry in September’s shine, your living will be rich and fine.”

Brides were just as superstitious about days of the week. A popular rhyme goes:

Marry on Monday for health,

Tuesday for wealth,

Wednesday the best day of all,

Thursday for crosses,

Friday for losses, and

Saturday for no luck at all.

The Sabbath day was out of the question.

Once the bride chose her wedding day, a prerogative conferred upon her by the groom, she could begin planning her trousseau, the most important item of which was her wedding dress.

Brides have not always worn white for the marriage ceremony. In the 16th and 17th centuries for example, girls in their teens married in pale green, a sign of fertility. A mature girl in her twenties wore a brown dress, and older women even wore black. From early Saxon times to the 18th century, only poorer brides came to their wedding dressed in white–a public statement that she brought nothing with her to the marriage. Other brides wore their Sunday best.

The colour of the gown was thought to influence one’s future life.

White–chosen right

Blue–love will be true

Yellow–ashamed of her fellow

Red–wish herself dead

Black–wish herself back

Grey–travel far away

Pink–of you he’ll always think

Green-ashamed to be seen

Ever since Queen Victoria wed in 1840, however, white has remained the traditional color for wedding gowns and bouquets. A woman then used her dress for Court Presentation after marriage, usually with a different bodice. The bride would likely wear a simple, practical dress, typically made of affordable materials such as cotton or calico. The groom would wear a suit, although it might not be as elaborate or expensive as those worn by the upper classes.

The wedding ceremony would typically take place in a local church or chapel. It would be conducted by a clergyman or minister, following the religious traditions of the couple. Non-religious ceremonies might have been held as well, depending on the couple’s beliefs. However a working-class wedding in Islington, London, in 1881 would have been a modest affair, reflecting the social and economic circumstances of the time.

Working-class weddings were often held in local community halls, pubs, or even in the homes of the bride or groom’s families. These venues were usually small and could accommodate a limited number of guests.

The guest list would typically consist of close family members, friends, and neighbors. Working-class weddings were usually smaller in scale compared to those of the upper classes. Guests in mourning entered the church quietly and hid amongst the crowd, so as not to cast negative aspersions on the couple.

Before the 1880s, a couple was required by law to have a morning ceremony. By the late 1880s, permissible hours were extended until 3:00 p.m.

Church bells pealed forth as the couple entered the church, not only to make the populace aware of the ceremony taking place, but also to scare away any evil forces lurking nearby.

One usher was usually in charge of matters at church, while the others went to the bride’s house for their favors.

The bride pinned favors of white ribbon, flowers, lace and silver leaves on the ushers’ shoulders.

In early Victorian England, the bridesmaids also made favors and pinned them on the sleeves and shoulders of the guests as they left the ceremony. Later in the era, even the servants and horses wore flowers. The servants’ favors were handmade by the bride and included a special memento if she’d known them from childhood.

The wedding ring was usually a plain gold band with the initials of the couple and the date of their wedding engraved inside. There were few double ring ceremonies in the Victorian era.

It was considered good luck for the ring to drop during the ceremony, thus all evil spirits were shaken out. 💍

Decorations would be minimal due to limited resources. Flowers, if used, would likely be local and inexpensive varieties. Ribbons and garlands might be hung in the venue to add a festive touch.

After the ceremony, the bride and groom walked out without looking left or right. It was considered bad taste to acknowledge friends and acquaintances. The bride’s parents were the first to leave the church, and the best man the last after he paid the clergyman for his services. From a custom dating back to Roman times when nuts were thrown after the departing couple, the practice continued, but in the form of rice, grain or birdseed, a symbol of fertility. A wedding carriage awaiting the bride and groom and was most likely drawn by four white horses.

The food served at a working-class wedding would be simple and affordable. A typical menu might include dishes like roasted meats (such as beef or chicken), potatoes, vegetables, and bread.

For dessert, there could be cakes or puddings.

Drinks would likely include beer and perhaps some spirits.

Guests were served standing, although the bridal party was served seated. There was no entertainment at the wedding, unless it was a lavish evening affair, at which time there was dancing. It was understood that the guests needed no entertainment, as they the honor came in attending the wedding itself.

In early Victorian times, there were usually three wedding cakes, one elaborate cake, and two smaller ones for the bride and groom. The cake was cut and boxed and given to guests as they left.

Traditionally the wedding cake was a dark, rich fruitcake with ornate white frostings of scrolls, orange blossoms, etc. The bride and groom’s cakes were not as elaborate. Hers was white cake, his dark. It was cut into as many pieces as there were attendants and often favors were baked inside for luck. Each charm had its own meaning.

The ring for marriage within a year;

The penny for wealth, my dear;

The thimble for an old maid or bachelor born;

The button for sweethearts all forlorn.

This tradition died away with the century, as the bridesmaids did not wish to soil their gloves looking for the favor. The cake the bride cut was not eaten, rather it was packed away for the 25th wedding anniversary!

Working-class couples would not typically receive expensive or extravagant gifts. Instead, guests might contribute money to help the newlyweds start their life together. Practical items for setting up a household, such as kitchen utensils or linens, could also be given.

If the wedding took place later in the day and the couple had a ceremony and meal, the rest of the evening would be spent socializing, dancing, and celebrating. The atmosphere would be joyful and inclusive, with guests enjoying the company of family and friends.

If the couple were lucky enough to have a honeymoon, the bridal couple usually left for their honeymoon after the wedding breakfast. The honeymoon originated with early man when marriages were by capture, not by choice.

The man carried his bride off to a secret place where her parents or relatives couldn’t find her. While the moon went through all its phases-about 30 days-they hid from searchers and drank a brew made from mead and honey. Thus, the word, honeymoon. The honeymoon is now considered a time to relax.

In the early 19th century, it was customary for the bride to take a female companion along on the honeymoon.

The bride wore a traveling dress, which may have been her wedding dress, especially if the wedding had been an intimate affair with few family and friends, or they were traveling by train or steamer immediately after the reception. Colors for the dress were becoming and practical–brown or black for mid-Victorian. But whatever she chose, the bride was advised not to wear something conspicuously new out of respect to the sensitivity of her husband who might not want people to know he was just married. If the bride was married in her traveling dress, she often wore a bonnet with it instead of a veil.

If changing into the traveling costumes, the bride and groom did so immediately after the cake was cut. Bridesmaids went with the bride to help her, at which time she gave them each a flower from her bouquet. By the time the couple was ready to depart, only family and intimate friends were present. As the couple drove off in a carriage pulled by white horses, the remaining party-goers threw satin slippers and rice after the couple. If a slipper landed in the carriage, it was considered good luck forever. If it was a left slipper, all the better.

The best man preceded the couple to the train or steamer to look after their luggage. No one asked where the bride and groom were going. It was bad taste. Only the best man knew, and he was sworn to secrecy.

Finally, upon their return from their travels, one final custom required that the groom carry the bride over the threshold to their new house. This would ensure that the bride did not stumble, which would bring bad luck.

As you can see, Victorian traditions were steeped in superstitions and age-old customs, some of which we still follow toady, though not necessarily in fear of evil spirits.

Just like modern day weddings and receptions, each and every one, would have been different based on individual circumstances, cultural backgrounds, and personal preferences.

Isn’t that a wonderful thing.

Susan’s childhood years were over, she’s fallen in love and wed her soulmate. So what happened next? Will there be troubled waters ahead or will they live their happy ever after?

Please pop back next week to read all about Susan’s life as a married women.

Until then, stay safe, stay true, stay you.

Too-da-loo.

🦋🦋🦋

I have brought and paid for all certificates,

Please do not download or use them without my permission.

All you have to do is ask.

Thank you.

What an awesome piece of history you wrote about Gorgie! I so enjoyed reading this week, and can’t wait to find out what happens to Susan next.

It was very thought provoking, and educational.

Thank you,

So well written!! after such hard work put into research .

Well done Gorgie, fantastic piece of work.. x x

LikeLike

How fascinating I did not realise that weddings were so steeped in tradition. Brilliant research.

LikeLike