In the tapestry of Edwin Paul Willats' life, woven intricately with threads of hope, resilience, and the unyielding bond of love, one thread shines with a brilliance that outshines all others: Nellie Highe/High. Their union was not just a marriage of hearts but a symphony of two souls finding harmony in each other's presence.

From the moment Edwin first laid eyes on Nellie, fate seemed to whisper promises of shared dreams and steadfast companionship. Their love blossomed amidst the backdrop of a world undergoing profound change, yet amidst the tumult, their commitment remained an anchor, a haven of tranquility and unwavering support.

In the days that followed their vows, Edwin and Nellie embarked on a journey filled with laughter and tears, triumphs and trials. Together, they navigated the uncertainties of life with a grace born of deep affection and mutual respect. Through the simple joys of everyday life and the poignant moments of shared sorrow, their love grew stronger, forging bonds that transcended the passage of time.

As I delve deeper into Edwin's life post-marriage, I am sure the love Nellie had for him helped shape his values and aspirations. Her gentle encouragement would have spurred him on through challenges, her wisdom guiding him through uncertainties, and her love enveloping him in a warmth that knew no bounds.

In this second installment of Edwin Paul Willats' journey, I invite you to journey alongside me as we uncover the chapters that illuminate their enduring love story. Through anecdotes and reflections, we will witness how their love painted the canvas of their shared existence, a masterpiece of devotion, resilience, and a legacy that resonates across generations.

Join me as we celebrate the life of Edwin Paul Willats and the woman who breathed life into his dreams. Together, let us honor their journey, a testament to the timeless power of love and the beauty of a life intertwined with another's soul until death did part them, and beyond.

So without further ado, I give you,

The Life Of, Edwin Paul Willats,

1871-1920,

Part 2:

Embracing Eternity Together.

Welcome back to the year 1901, London, England. The United Kingdom finds itself in a period of transition and continuity as a new century dawns. Queen Victoria, who had reigned for over six decades, has passed away at the age of 81, marking the end of the Victorian era. Her son, Albert Edward, ascends the throne as King Edward VII, bringing a shift in style and demeanor to the monarchy.

At the helm of government is Prime Minister Lord Salisbury, a stalwart of conservative politics, known for his adept management of foreign affairs and imperial policies. His tenure reflects the dominance of the Conservative Party in shaping domestic legislation and international relations, particularly maintaining Britain's imperial interests amidst global rivalries.

Parliament, predominantly composed of aristocrats and landed gentry, remains a bastion of privilege and power. The House of Lords, representing the hereditary nobility, often acts as a check on the more populist impulses emerging from the House of Commons. Political discourse is vibrant yet constrained within the confines of traditional hierarchies and class distinctions.

Socially, the United Kingdom remains stratified along rigid lines of class and wealth. The upper class, comprising titled nobility, wealthy industrialists, and influential landowners, holds sway over politics, culture, and commerce. Lavish balls, country estate weekends, and exclusive clubs in London's West End define their social calendar, fostering a sense of elitism and exclusivity.

Meanwhile, the working class and the poor endure harsh conditions in urban slums and industrial towns, where overcrowded housing, poor sanitation, and meager wages characterize daily life. The rise of socialist movements, such as the Fabian Society and the Labour Party, reflects growing discontent and calls for reform to address inequality, labor rights, and social welfare.

Energy and transportation undergo significant developments. Coal remains the primary source of energy, powering factories, steamships, and railways that connect the nation's industrial heartlands with its ports and cities. The expanding railway network facilitates the movement of goods and people, transforming travel and trade across the country.

Culturally, London thrives as a hub of artistic innovation and intellectual debate. The Bloomsbury Group, centered around Virginia Woolf and her contemporaries, challenges Victorian conventions with avant-garde literature and modernist ideas. The theater scene flourishes with productions at West End theaters, while music halls entertain the masses with variety shows and comedic performances.

Fashion reflects Edwardian elegance, characterized by tailored suits and dresses that emphasize grace and sophistication. Women's fashion sees a departure from the restrictive corsets of the Victorian era, embracing looser silhouettes and higher hemlines that hint at changing attitudes towards gender roles and freedom of movement.

In the realm of gossip and society pages, the rich and famous captivate public fascination with their scandals and affairs. High society indulges in extravagant parties and scandalous liaisons, while newspapers eagerly report on the latest intrigues of aristocratic families and socialites.

Education remains a privilege rather than a right for many, with public schools and universities predominantly accessible to the upper class. The Elementary Education Act of 1899 seeks to improve schooling for working-class children, yet disparities persist in access to quality education and opportunities for social mobility.

As the Edwardian era unfolds, the United Kingdom stands at a crossroads of tradition and progress, grappling with the complexities of a rapidly changing world. From the corridors of power in Westminster to the bustling streets of London, the year 1901 encapsulates a nation poised on the brink of transformation, navigating the challenges and promises of a new century with optimism and apprehension alike.

1901 was also the year of the census, a critical snapshot capturing the demographic landscape of the United Kingdom at the dawn of the 20th century. Conducted on the night of March 31st, the census offered a detailed look at the lives of millions, revealing not just numbers but stories of migration, occupation, family structures, and the social dynamics that defined an era in transition.

The 1901 Census recorded a population of approximately 38 million people in England and Wales, with significant populations also in Scotland and Ireland. This vast enumeration effort involved thousands of enumerators who traversed cities, towns, and rural areas, collecting data door-to-door. Each household was asked to provide information about every person present, including their name, age, sex, occupation, marital status, birthplace, and relationship to the head of the household.

One of the striking aspects of the 1901 Census was its reflection of the ongoing urbanization and industrialization of Britain. Major cities like London, Manchester, Birmingham, and Glasgow saw substantial population growth, driven by the migration of people from rural areas in search of employment and better living conditions. The census data highlighted the dense and often overcrowded living conditions in these urban centers, with many families crammed into small, poorly ventilated housing.

The occupational data from the census revealed the changing nature of work in the early 20th century. The industrial revolution had brought about a shift from agrarian economies to manufacturing and services. Factories, mills, and mines employed large numbers of people, including women and children, who worked long hours in challenging conditions. The census provided a detailed account of the various trades and professions, showcasing the diversity of labor that powered the British economy.

Family structures recorded in the 1901 Census illustrated the societal norms and expectations of the time. Households typically consisted of a nuclear family, often with several children, but it was also common to find extended families living together, including grandparents, aunts, uncles, and cousins. The census highlighted the roles within families, where men were usually listed as the head of the household and primary breadwinners, while women were often recorded as homemakers, although many also worked outside the home.

The 1901 Census also shed light on the rich tapestry of British society, marked by significant social stratification. The data reflected the stark contrasts between the wealthy elite and the working poor. The upper classes lived in spacious homes with numerous servants, while the working classes endured cramped and unsanitary living conditions. This socioeconomic divide was a catalyst for the growing movement toward social reform, as the disparities became increasingly difficult to ignore.

Migration patterns were another key element documented in the 1901 Census. It captured the influx of people from Ireland and other parts of the British Empire, drawn by the promise of employment and a better life. These migrant communities added to the cultural and ethnic diversity of the UK, particularly in major urban centers. The census data provided a basis for understanding the demographic shifts and the challenges of integration and adaptation faced by these new arrivals.

Education and literacy were also areas of focus in the census, reflecting the efforts to improve access to schooling for all children. The data showed an increasing number of children attending school, a result of legislative efforts like the Elementary Education Act of 1899. However, it also revealed regional disparities and the continued struggle to provide quality education across the country.

The 1901 census shows us that Edwin and Nellie were residing at Number 50 Brownswood Road, Finsbury Park, Stoke Newington, London, England, on Sunday the 31st of March 1901.

Edwin was working as an architect assistant.

The Ecclesiastical parish was St John Brownswood Park.

Amy H Vernor, Alfred E Ward and Emma Ward were also residing at number 50.

Brownswood Road, located in the Stoke Newington area of London, is a street steeped in history and reflective of the broader changes that have shaped this vibrant district. Stoke Newington itself is part of the London Borough of Hackney, known for its rich cultural diversity, eclectic architecture, and a strong sense of community. Brownswood Road contributes to this dynamic with its mix of residential and local business premises, as well as its accessibility to various amenities and transportation links.

Historically, Brownswood Road and the surrounding area developed during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, a time when London was expanding rapidly due to industrialization and population growth. The road features typical Victorian and Edwardian housing, characterized by their ornate brickwork, large sash windows, and decorative features. These homes were built to accommodate the growing middle class, offering spacious interiors and distinctive architectural details that are still admired today.

The community around Brownswood Road is known for its diversity and inclusivity. This area has traditionally been a melting pot of different cultures and backgrounds, contributing to a vibrant and dynamic local atmosphere. Residents are known for their strong community spirit, often engaging in local events, markets, and community initiatives that foster a sense of belonging and mutual support.

One of the key attractions near Brownswood Road is Clissold Park, a beloved green space that serves as a communal backyard for many local residents. The park features beautifully landscaped gardens, a cafe, a small animal enclosure, and facilities for various sports and recreational activities. It is a popular spot for families, joggers, and anyone looking to enjoy some outdoor relaxation away from the hustle and bustle of city life.

In terms of local amenities, Brownswood Road benefits from its proximity to Stoke Newington Church Street, which is known for its array of independent shops, cafes, restaurants, and pubs. This bustling street is a focal point for the community, offering everything from artisanal coffee to unique boutiques, reflecting the area's bohemian and entrepreneurial spirit. The presence of these local businesses adds to the charm and convenience of living on or near Brownswood Road.

Education is a strong point for the area, with several well-regarded schools nearby. This makes Brownswood Road an attractive location for families seeking quality education for their children. The emphasis on education is part of a broader commitment to community development and support, ensuring that young residents have access to opportunities for growth and learning.

Transportation links are excellent, with Brownswood Road benefiting from multiple public transport options. The nearby Manor House and Finsbury Park stations provide access to the London Underground's Piccadilly and Victoria lines, as well as National Rail services. Numerous bus routes also serve the area, making it easy to travel to other parts of London for work or leisure.

Culturally, Stoke Newington, including Brownswood Road, has a rich heritage. The area has long been associated with progressive thinking and artistic expression. This legacy continues today, with local galleries, theaters, and music venues contributing to a vibrant cultural scene. Residents and visitors alike can enjoy a range of cultural activities, from live performances to art exhibitions.

In recent years, Brownswood Road and the surrounding area have experienced some degree of gentrification. This process has brought improvements in local amenities and infrastructure but has also raised concerns about affordability and the potential loss of the area's unique character. The community continues to navigate these changes, striving to balance development with the preservation of its distinctive identity.

It wasn’t long before Edwins beloved wife Nellie was in the family way.

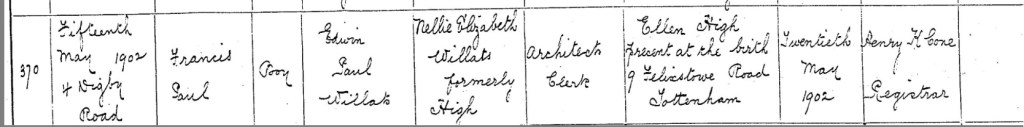

Edwin Paul and Nellie’s, son Francis Paul Willats, was born on Thursday the 15th of May, 1902, at Number 4, Digby Road, Hackney, London, England. Francis’s. Grandmother Ellen High nee Bushell, of Numcber 9, Felixstone Road, Tottenham, was present and registered his birth on Tuesday the 20th of May 1909. She gave Francis’s father, Edwin Paul Willats occupation as a Architects clark

Digby Road, located in the London Borough of Hackney, has a rich history that reflects the broader changes in the area over the years. Situated in East London, Hackney has long been a melting pot of cultures and communities, and Digby Road is no exception.

In the 19th century, Hackney began to develop rapidly due to the expansion of the railway network, which made it more accessible to the growing population of London. The area that includes Digby Road was primarily residential, populated by working-class families who were employed in various industries across London.

The architecture of Digby Road, like much of Hackney, is characterized by Victorian terraced houses. These houses were built to accommodate the influx of people moving to the area for work and were typical of the housing developments of that era. Over time, some of these buildings have been replaced or renovated, but the road still retains much of its historical charm.

Hackney, including Digby Road, experienced significant social and economic changes throughout the 20th century. During the post-war period, there was a push for urban renewal, leading to the construction of new housing estates and the modernization of existing structures. This period saw a mix of architectural styles as modernist influences began to take hold, leading to a diverse streetscape.

The cultural fabric of Digby Road and the surrounding area has also evolved significantly. Hackney has been home to waves of immigrants from various parts of the world, including the Caribbean, Africa, and more recently, Eastern Europe. This diversity is reflected in the local businesses, cultural institutions, and community activities that can be found on and around Digby Road.

In recent decades, Hackney has undergone gentrification, with rising property prices and an influx of new residents attracted by the area's vibrant cultural scene and proximity to central London. This process has brought about further changes to Digby Road, with new developments and a shift in the demographic profile of the residents.

Today, Digby Road is a microcosm of Hackney's broader historical and cultural narrative. It showcases a blend of historical architecture and modern developments, embodying the dynamic and ever-changing nature of East London. The road, while rooted in its historical context, continues to evolve, reflecting the ongoing story of Hackney itself.

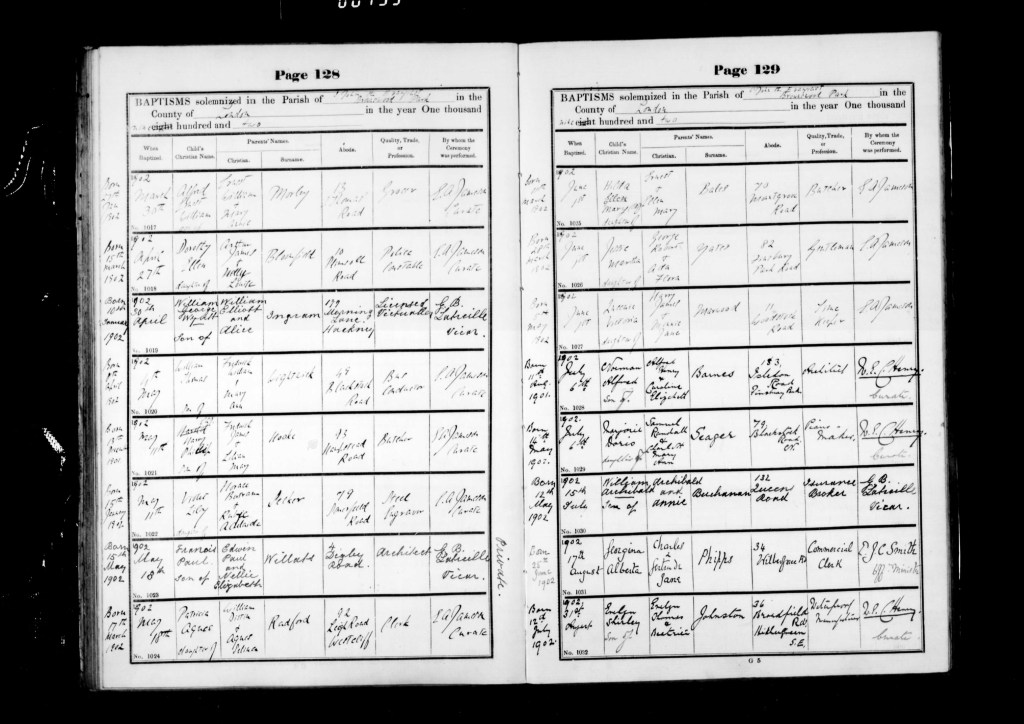

Edwin and Nellie’s son, Francis Paul Willats was baptized on Sunday the 18th May 1902 at St John the Evangelist, Queen's Drive, Brownswood Park Finsbury Park, N4 2LW, United Kingdom.

Edwin Paul Willats occupation as a Architect and their abode as Number 4, Digby Road.

St John the Evangelist, located in Finsbury Park, Hackney, holds a significant place in the historical and cultural fabric of the area. Its history is intertwined with the urban development of North London, particularly through the 19th and 20th centuries.

The church was built in response to the rapid population growth in the Finsbury Park area during the Victorian era. This period saw an explosion of residential developments as London expanded, leading to a pressing need for new parish churches to cater to the spiritual needs of the burgeoning communities. St John the Evangelist was one such church, designed to serve the growing population of Finsbury Park and the surrounding neighborhoods.

The architectural style of St John the Evangelist is quintessentially Victorian Gothic, a style that was immensely popular during the time of its construction. The church’s design features many of the hallmarks of this architectural style, including pointed arches, intricate stone carvings, and tall, narrow windows filled with stained glass. These elements not only made the church an architectural landmark but also a beacon of spiritual solace for the local community.

Throughout its history, St John the Evangelist has been more than just a place of worship. It has served as a community center, a place of refuge, and a focal point for local events and activities. The church has witnessed numerous societal changes, from the industrial revolution and the subsequent urbanization of London to the socio-economic shifts of the 20th and 21st centuries.

During both World Wars, St John the Evangelist played a crucial role in the community. It provided a place for people to come together, find solace, and support one another through the challenging times. The church also hosted various community services, helping those affected by the wars, whether through loss or displacement.

In the latter half of the 20th century, St John the Evangelist continued to evolve, reflecting the changing dynamics of the Finsbury Park area. The post-war period brought significant social and cultural changes, including increased diversity and shifts in population. The church adapted to these changes by becoming more inclusive and broadening its outreach efforts to better serve the needs of a more varied congregation.

In recent years, St John the Evangelist has embraced modernity while retaining its historical essence. The church has incorporated contemporary practices and technologies to remain relevant and accessible to its congregation. This includes the use of digital media for communication and outreach, as well as modern amenities within the church to enhance the experience of visitors and worshippers.

St John the Evangelist’s rich history is a testament to its resilience and adaptability. It has not only stood as a spiritual haven but also as a cornerstone of the community, evolving with the times while preserving its historical and cultural heritage. The church remains a vital part of Finsbury Park, embodying the spirit of the area and its people through the ages.

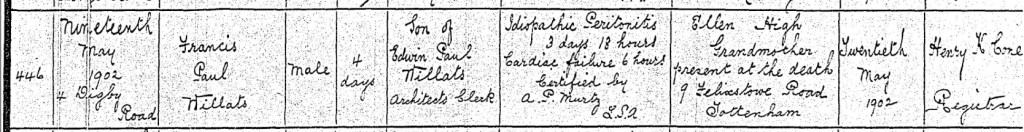

The following day, Architects Clark, Edwin Paul and Nellie Elizabeth Willats son, 4-day-old, Francis Paul Willats sadly died on Monday the 19th of May 1902, at Number 4, Didby Road, Hackney, London, England.

Francis died from, Idiopathic Peritonitis (3 days 18 hours) and Cardial Failure (6hours).

Francis’s Grandmother Ellen High nee Bushell, of Numcber 9, Felixstone Road, Tottenham, was present and registered his death on Tuesday the 20th of May 1902.

Idiopathic peritonitis and cardiac failure are two serious medical conditions that, when occurring together, suggest a complex and critical health situation.

Idiopathic peritonitis refers to inflammation of the peritoneum, the thin layer of tissue lining the inside of the abdomen and covering the abdominal organs, with no identifiable cause. "Idiopathic" means that despite thorough investigations, no specific cause for the inflammation can be found. Peritonitis itself can be triggered by a variety of factors including infections (bacterial or fungal), abdominal injury, or underlying medical conditions such as liver disease or pancreatitis. However, in idiopathic cases, these common causes are not present, which can complicate diagnosis and treatment.

The symptoms of peritonitis typically include severe abdominal pain, tenderness, and bloating, along with fever, nausea, and vomiting. These symptoms arise because the inflamed peritoneum becomes irritated and swollen, which can also lead to fluid accumulation in the abdomen, a condition known as ascites. Peritonitis is a medical emergency requiring prompt treatment, usually involving antibiotics to combat potential infection and, in some cases, surgery to remove any infected tissue or correct underlying issues contributing to the inflammation.

Cardiac failure, also known as heart failure, occurs when the heart is unable to pump blood effectively to meet the body’s needs. This condition can develop over time due to various underlying issues such as coronary artery disease, high blood pressure, or previous heart attacks, which damage the heart muscle. When the heart’s pumping ability is compromised, blood flow to vital organs is reduced, leading to symptoms like shortness of breath, fatigue, swelling in the legs and ankles (edema), and fluid retention.

When cardiac failure occurs, the body attempts to compensate for the reduced blood flow by retaining more fluid and increasing blood volume, which further stresses the heart. This creates a vicious cycle where the heart’s ability to pump effectively continues to decline, worsening the symptoms and potentially leading to acute episodes of heart failure that require emergency medical intervention.

The coexistence of idiopathic peritonitis and cardiac failure indicates a particularly dire situation. One possible link between the two conditions could be the systemic effects of heart failure, which can lead to congestion and fluid buildup in the abdomen (ascites). This fluid accumulation can create a conducive environment for the development of peritonitis, even in the absence of a clear infectious or inflammatory cause. Moreover, the inflammation from peritonitis can further strain the cardiovascular system, exacerbating the symptoms of heart failure.

Diagnosing and treating these concurrent conditions is highly complex. Idiopathic peritonitis requires thorough investigation to rule out identifiable causes and manage symptoms effectively, often through a combination of antibiotics and supportive care. Meanwhile, managing cardiac failure involves addressing the underlying heart condition, optimizing fluid balance through medications such as diuretics, and employing lifestyle changes to reduce the strain on the heart.

The prognosis for someone with both idiopathic peritonitis and cardiac failure depends on various factors, including the severity of each condition, the individual’s overall health, and how quickly and effectively treatment is administered. In the early 20th century, when medical interventions were far less advanced than today, such a combination of conditions would likely have posed a significant risk of mortality. Modern medical advancements offer better diagnostic tools and treatments, improving the chances of managing such complex cases more effectively.

In 1902, the grieving process for a man after losing his son would have been profoundly shaped by the social, cultural, and medical context of the time. The death of a child, especially a son, was a tragic event that brought intense sorrow and emotional turmoil, though the expression and handling of this grief often adhered to the period's norms and expectations.

A man in 1902, upon losing his son, would first confront the immediate shock and disbelief of the loss. The death of a child often elicited profound grief, yet societal expectations of masculinity during the Victorian and Edwardian eras dictated that men should remain stoic and composed, suppressing overt displays of emotion. Public mourning rituals, such as funerals and memorial services, provided a structured way to honor the deceased, yet men were generally expected to maintain a calm and controlled demeanor.

The funeral would be a critical part of the grieving process. It served as a formal occasion to pay respects and say farewell, often attended by extended family, friends, and the community. In this period, funerals were solemn and elaborate affairs, with specific customs and attire, such as wearing black mourning clothes. These rituals provided a framework for expressing grief within socially acceptable boundaries. The father might take an active role in organizing and participating in the funeral, finding a degree of solace in these responsibilities.

Privately, the grieving man might find it challenging to reconcile his profound sense of loss with the expectation to remain strong and unemotional. The cultural emphasis on male stoicism meant that many men experienced their grief internally, often in isolation. The home, traditionally a woman's domain, was where mourning was more openly expressed. Consequently, a grieving father might withdraw, spending time alone or immersing himself in work or other activities to distract from his sorrow.

Support systems available to a grieving man were limited by today's standards. While family members, particularly his wife, might offer some comfort, men were less likely to openly share their emotional pain with friends or seek support groups. Religion often played a significant role in the grieving process. The church provided spiritual guidance and consolation, and religious faith might offer a framework for understanding and accepting the loss. Attending services, prayer, and reflection were common practices for coping with grief.

The grieving process was also influenced by contemporary medical understandings of mental health, which were rudimentary compared to modern standards. Psychological support, such as counseling or therapy, was virtually nonexistent. Instead, men were encouraged to bear their grief with dignity and move forward, often without the opportunity to fully process their emotions.

The loss of a son could also have significant social and economic implications, particularly if the son was an only child or the eldest, expected to inherit and continue the family lineage. This added another layer of grief, as the father would not only mourn the loss of his child but also the future he had envisioned for him. This could lead to feelings of failure or a deepened sense of loss. ☹️

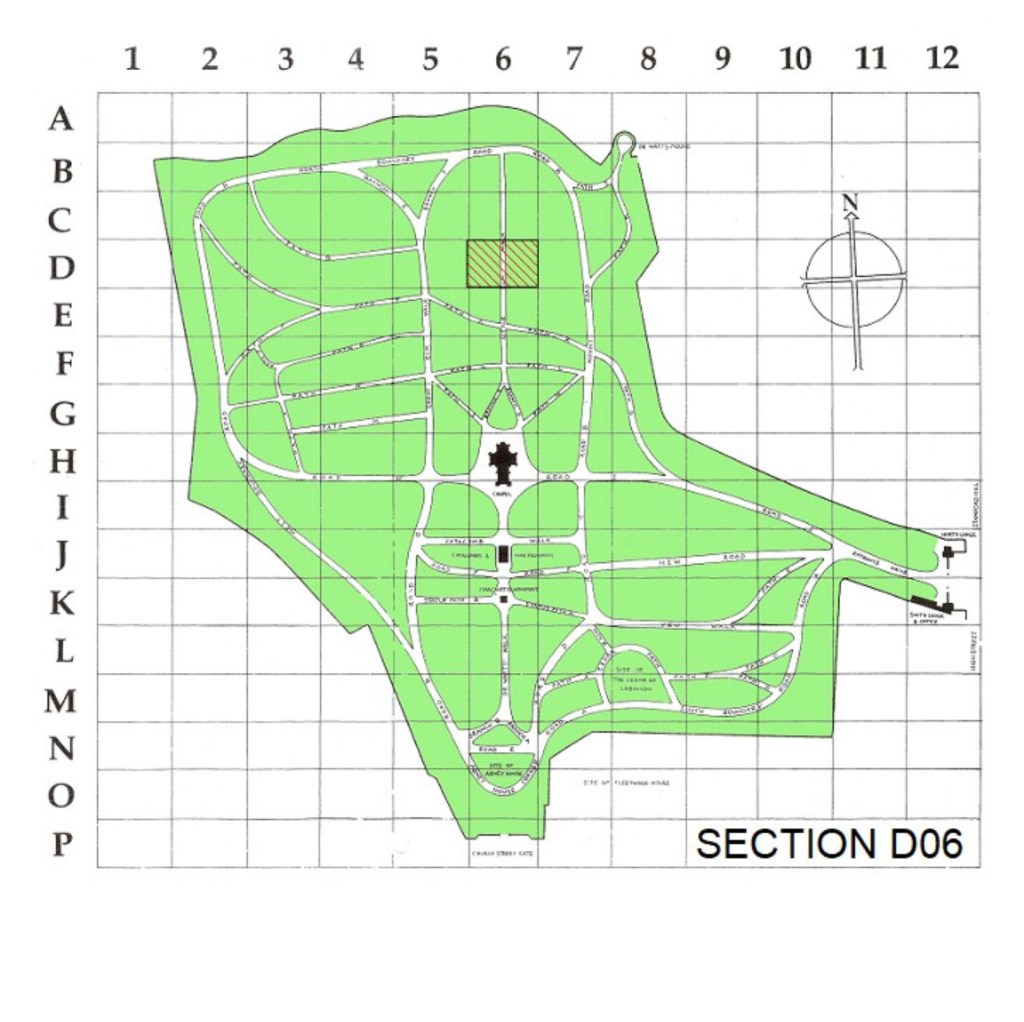

Edwin and Nellie’s laid, Francis Paul Willats to rest on Wednesday the 21st of May 1902, at Abney Park Cemetery, Stoke Newington, Hackney, London, England, in Plot Section. D06, Index 5S02, with his Grandparents, Richard and Eliza Willats and his uncles William George (Biggun) and later Percy Sidney Willats.

In 1902, the funeral and burial of a baby would have been marked by a combination of deep personal sorrow and societal attitudes towards infant mortality, which was unfortunately more common during that time due to limited medical advancements. The family's experience would be profoundly emotional, though the rituals and customs surrounding the event would reflect the period's specific practices and beliefs.

When a baby died at such a young age, the initial response would often be a mix of grief and resignation. Infant mortality was higher in the early 20th century, and while each loss was deeply felt, families were somewhat more accustomed to the possibility of such tragedies. The immediate steps following the death would involve preparing the baby for burial, a task usually undertaken by the parents or female relatives.

The baby would typically be washed and dressed in simple, often handmade burial garments. These clothes were usually white, symbolizing innocence and purity. If the family belonged to a Christian denomination, the child might also be christened posthumously if this had not occurred before death. This was a common practice in Catholic and some Protestant traditions, as it ensured the baby's soul would be received into heaven according to their beliefs.

Given the young age of the deceased, the funeral itself would generally be a more private affair compared to those for older children or adults. It might take place in the family home or a small chapel, attended primarily by close family members and a few friends. The ceremony would be brief and somber, reflecting both the tender age of the child and the profound grief of the parents.

A clergyman would usually conduct the service, offering prayers and words of comfort to the grieving family. The service might include readings from scripture, hymns, and a short homily focusing on themes of innocence, purity, and the hope of reuniting in the afterlife. In the case of a Catholic family, the funeral might also involve a requiem mass, albeit a simpler version than for an adult.

The burial would follow the funeral service, with the baby being interred in a small coffin. The coffin was often plain and unadorned, reflecting the simplicity and purity of the child's life. The burial plot might be in a family cemetery or a designated section for infants within a larger cemetery. In some cases, particularly in rural areas, the baby might be buried on family property.

At the graveside, the clergyman would perform the committal service, offering final prayers and committing the baby's body to the earth. This part of the ceremony would be poignant and emotional, providing a moment for the family to say their final goodbyes. Family members might place flowers or personal mementos in the grave as symbols of their love and remembrance.

Following the burial, the family would enter a period of mourning. The duration and expression of mourning varied depending on cultural and regional practices, but it often included wearing black or subdued clothing, refraining from social activities, and finding solace in religious practices. The loss of a baby, though devastating, might not involve the extended public mourning expected for an older child or adult, reflecting both the brevity of the child's life and societal attitudes towards infant death.

Throughout this process, the emotional support of family and friends would be crucial. Women, in particular, played a central role in comforting the grieving mother, offering both practical assistance and emotional solace. Community support networks, although informal, provided an essential source of comfort and help during such a difficult time.

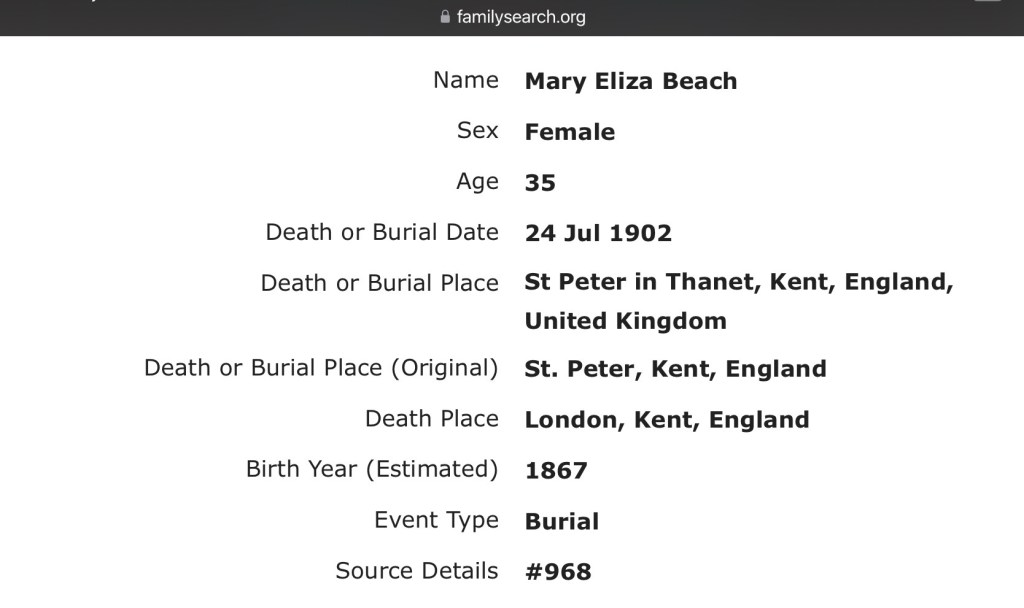

Heartbreakingly more death followed when Edwin’s sister, Eliza Mary Beach nee Willats died on Monday the 21st of July 1902, at Beach Court, Upper Deals, Eastry, Kent, England, at the awfully young age of 35 years.

Eliza died from Pneumonia and exhaustion. Edith Cameron Charlton nee Willats, Richards's daughter and Eliza's sister, was present and registered her death on the same day, Monday the 21st of July 1902. Edith stated that Eliza was the wife of Benjamin Beach, giving his profession an, independent means. Eliza’s death was registered under the name Mary Eliza Beach.

Edwin and family laid Eliza Mary Beach nee Willats, to rest on Thursday the 24th of July, 1902, at St Peter in Thanet, Kent, England.

St Peter's is an area of Broadstairs, a town on the Isle of Thanet in Kent. Historically a village, it was outgrown by the long-dominant settlement of the two, Broadstairs, after 1841. Originally the borough or manor of the church of St. Peter-in-Thanet, it was said to be the largest parish east of London, at least until Broadstairs became a separate parish on 27 September 1850. The two settlements were formally merged administratively in 1895. The village and its church, named after Saint Peter, was the second daughter church of Minster established in 1070, although the first written record of its present name dates to 1124. In 1254 the village was named "scī Petr'", which gradually changed to "scī Petri" by 1270, Sti Petri in Insula de Thaneto by 1422, and finally settling by 1610 on its current form of St Peter's. The church has the right to fly the white ensign, dating from when the church tower was used as a signalling station in the Napoleonic Wars. The village sign won first prize in a nationwide competition in 1920. Edward Heath, leader of the Conservative Party from 1965 to 1975, serving as prime minister from 1970 to 1974, was born in the village in 1916. On 27 April 1952, a United States Air Force Republic F-84 Thunderjet from RAF Manston crashed in the main street with loss of life.

Thankfully joy was once again on the horizon when, Edwin’s sister, 28-year-old, spinster, May Claretta Willats married 20-year-old, architectural florist, and bachelor, George Frederick Champion, on Saturday the 4th of April 1903, at St. John’s Church, Highbury Vale, Islington, London, England.

May gave her residence as, 21 Montague Road and George as, 194 Green Lands.

They gave their father’s names and occupations, as George Frederick Champion, an architectural florist and Richard Henry Willats an Estate Agent.

Their witnesses were, George Frederick Champion and May’s niece, Amina Eliza Catherine Charlton.

And Edwin’s brother 26-year-old bachelor, surveyor, Frederick Howard Willats, married 24-year-old spinster Maud May Beach, on Saturday the 19th of September 1903, at St. John’s Church, Highbury Vale, Islington, London, England.

Frederick gave his abode as, 27 Kings Road and Maud graves hers as, 16 Orchard Road, St. Margarets on Thames.

They gave their fathers names and occupations, as Richard Henry Willats, estate agent, and Walter Beach (deceased), a Gentleman.

Their witnesses were her brother, Persey Sidney Willats and his niece, Amina Eliza Catherine Charlton.

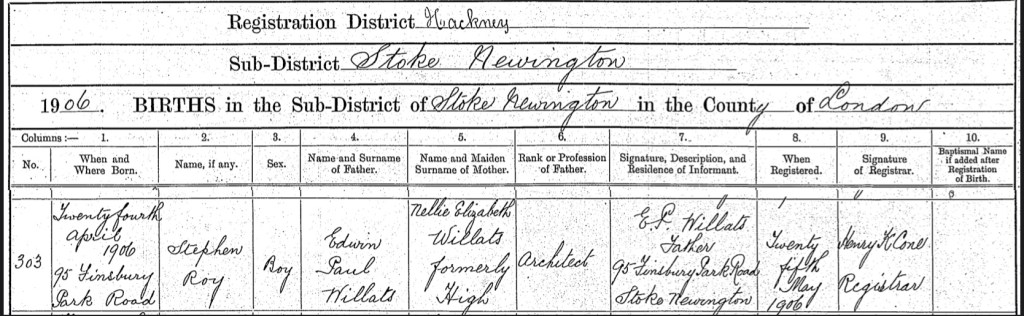

Edwin Paul and Nellie Elizabeth Willats nee High’s son, Stephen Roy Willats, was born on Tuesday the 24th of April, 1906 at Number 95, Finsbury Park Road, Stock Newington, Hackney, London, England. Edwin Paul registered Stephen's birth on Friday the 25th of May 1906, in Hackney, London, England. He gave his occupation as an Architect and their abode as Number 95, Finsbury Park Road, Stock Newington.

Finsbury Park Road in Stoke Newington is a street with a rich historical background, reflecting the broader development and transformations of the area over time. Located in North London, Stoke Newington is known for its vibrant community, historical landmarks, and diverse cultural heritage. Finsbury Park Road itself is part of this tapestry, embodying the changes and continuities that have shaped the region.

The history of Finsbury Park Road is closely tied to the development of Finsbury Park, a major public park in the area. The park was opened in 1869, designed by Frederick Manable and Alexander McKenzie, as a response to the need for green spaces in the rapidly urbanizing city of London. Its creation was part of a broader Victorian movement to provide recreational areas for the working class and improve public health.

The establishment of Finsbury Park spurred significant residential development in the surrounding areas, including the creation of streets like Finsbury Park Road. During the late 19th century, the area saw a boom in housing construction, with rows of Victorian terraced houses being built to accommodate the growing population. These homes were typically designed to house the burgeoning middle and working classes, who were attracted to the area by the park and the expanding railway network, which provided easy access to central London.

Finsbury Park Road, like much of Stoke Newington, would have been characterized by a mix of residential and small commercial properties, catering to the needs of local residents. The architecture of the street would reflect the Victorian style prevalent at the time, with brick terraces, sash windows, and decorative ironwork.

Throughout the 20th century, Finsbury Park Road and the surrounding areas experienced various social and economic changes. The aftermath of the two World Wars brought significant shifts, with many areas of London, including Stoke Newington, undergoing periods of decline and regeneration. The mid-20th century saw parts of the area struggling with issues such as overcrowding and inadequate housing conditions.

In the latter half of the 20th century, Stoke Newington, including Finsbury Park Road, began to experience a revival. This period saw an influx of diverse communities, including immigrants from the Caribbean, South Asia, and Africa, which enriched the cultural fabric of the area. The demographic changes brought new life to the neighborhood, with a variety of cultural influences reflected in local businesses, cuisine, and community activities.

Today, Finsbury Park Road is part of a vibrant and eclectic community. The area is known for its diversity, with a mix of long-term residents and newer arrivals contributing to a dynamic neighborhood atmosphere. The Victorian terraced houses have often been refurbished, maintaining their historical charm while incorporating modern amenities.

The road benefits from its proximity to Finsbury Park, which remains a central feature of the area. The park offers a wide range of recreational facilities, including sports fields, a boating lake, playgrounds, and an athletics stadium, making it a popular destination for residents and visitors alike.

The local economy around Finsbury Park Road includes a mix of independent shops, cafes, restaurants, and markets, reflecting the area’s multicultural heritage. This blend of old and new, local and international, gives the neighborhood its unique character.

Transportation links have always been a significant aspect of the area’s appeal. Finsbury Park Station, a major transport hub, provides access to the London Underground, National Rail services, and numerous bus routes, ensuring that residents of Finsbury Park Road are well-connected to the rest of London.

Across the pond, Edwin’s brother, 43-year-old, widower and salesman, Arthur Charles Willats, married 30-year-old, spinster and actress, Ruth Gadsby, on Wednesday the 17th of June 1908, at Niagara Falls, Welland, Niagara, Ontario, Canada.

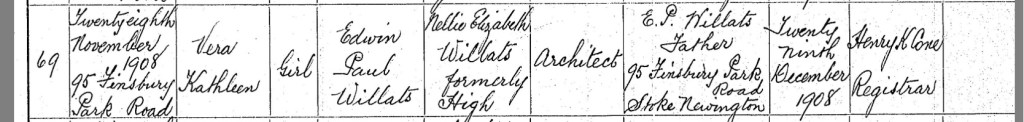

Back in England, Edwin Paul and Nellie Elizabeth daughter, Vera Kathleen Willats, was born on Saturday the 28th of November 1908, at Number 95, Finsbury Park Road, Stock Newington, Hackney, London, England.

Edwin Paul registered Vera’s birth on Tuesday the 29th December 1908, in Hackney, London, England.

He gave his occupation as an Architect and their abode as Number 95, Finsbury Park Road, Stock Newington.

And Edwin’s brother, 33-year-old, bachelor, Percy Sidney Willats, married 25-year-old, spinster, Sophie Ann Smart on Saturday the 24th of July 1909 at The Register Office, Edmonton, Middlesex, England.

Edwin Paul Willats was a witness as well as J H Champion.

Percy gave his occupation as an auctioneer.

They gave their abode as Number 11 The Quadrant, Winchmore Hill, Edmonton.

They gave their fathers names and occupations as, Richard Henry Willats, an auctioneer and John Smart, a Market Gardener.

Jumping forward to the year 1911 in England, one finds a nation at the height of its imperial power, yet also on the cusp of significant social and political changes. This year stands out for its rich tapestry of events, marking both progress and tension within the country.

The year began with a sense of continuity under the reign of King George V, who had ascended the throne the previous year following the death of his father, King Edward VII. 1911 was a significant year for the British monarchy, as it saw the Coronation of King George V on June 22. The ceremony, held at Westminster Abbey, was a grand event attended by dignitaries from around the world, showcasing the opulence and international stature of the British Empire. This occasion was marked by nationwide celebrations, including street parties and public festivities, reflecting a moment of national unity and pride.

However, beneath the surface of this regal display, England was experiencing considerable social unrest. The early 20th century was a period of heightened political activism and labor disputes. The year 1911 saw an increase in industrial strikes, with one of the most significant being the National Railway Strike in August. Railway workers, demanding better wages and working conditions, halted train services across the country. The strike caused significant disruption and highlighted the growing power and organization of trade unions. The government's response involved deploying troops to maintain order, underscoring the tensions between labor and the state.

Social change was also evident in the realm of women's rights. The suffragette movement, campaigning for women's suffrage, was gaining momentum. In 1911, the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU), led by Emmeline Pankhurst, continued its militant campaign for the right to vote. This year saw significant protests and acts of civil disobedience by suffragettes, who aimed to draw attention to their cause and pressure the government into granting voting rights to women.

Economic developments were also notable in 1911. The country was in the midst of a technological transformation, with advances in industry and infrastructure. This period saw the expansion of electric power and the growth of the automobile industry, which began to change the landscape of urban and rural life. The burgeoning film industry also reflected technological and cultural shifts, with cinema becoming an increasingly popular form of entertainment.

Internationally, England maintained its dominant position within the British Empire, which spanned the globe. The empire's vast reach was both a source of pride and a complex burden, involving political and military commitments around the world. 1911 was marked by the Agadir Crisis, a confrontation between France and Germany over influence in Morocco. England played a key role in the negotiations, supporting France and demonstrating its commitment to maintaining the balance of power in Europe. This incident foreshadowed the tensions that would eventually lead to the outbreak of World War I just a few years later.

The arts and culture scene in 1911 was vibrant, reflecting both the Edwardian penchant for elegance and the early stirrings of modernism. Literature, theatre, and music flourished, with writers such as H.G. Wells and Virginia Woolf beginning to gain prominence. The year's cultural highlights included significant theatrical productions and concerts, which catered to diverse audiences.

In the realm of science and exploration, 1911 was a landmark year. Notably, it was the year of the Terra Nova Expedition led by Robert Falcon Scott, which set off for Antarctica with the aim of reaching the South Pole. Although the expedition would end in tragedy, with Scott and his team perishing on their return journey in 1912, it captured the spirit of adventure and scientific inquiry that characterized the age.

The census of 1911, conducted in April, provided a snapshot of England's population and social conditions. It revealed a nation with a population of around 42 million, experiencing urbanization and demographic shifts. The census data showed the growing size of cities and the changing nature of work, with an increasing number of people employed in industry and services rather than agriculture.

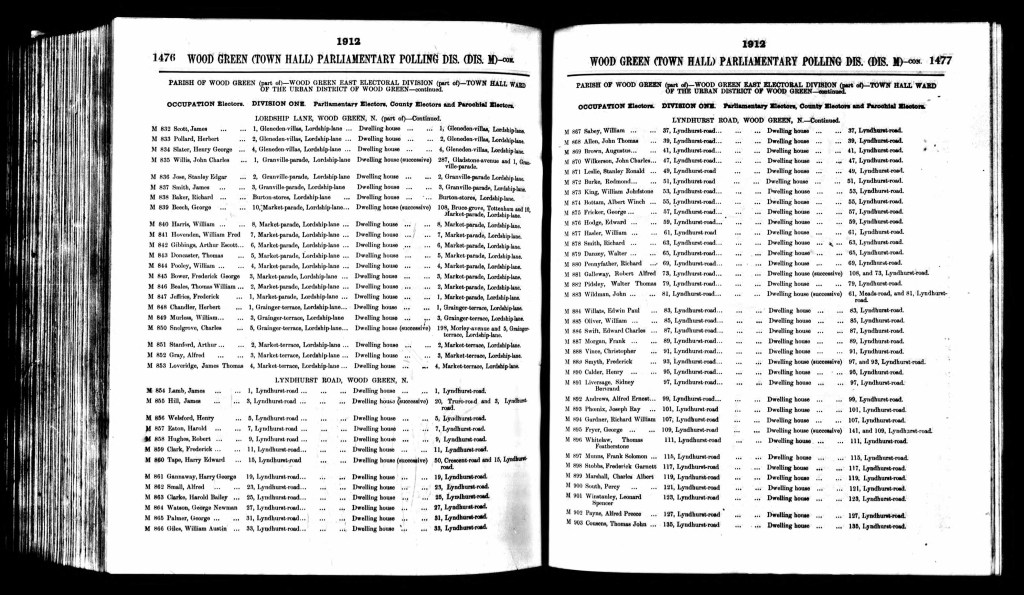

The census shows us that on Sunday the 2nd of April Edwin and Nellie and their Children Stephen and Vera, were residing at 83 Stanley Villas, Lyndhurst Road, Bowes Park, Wood Green, Middlesex, England, a four room dwelling.

Edwin was working as a Architects Clerk.

It also shows the Edwin and Nellie had been married for 10 years, they had, had 3 children but only 2 had survived.

Lyndhurst Road, situated in the Bowes Park area of Wood Green in Middlesex, carries with it a history reflective of the broader developments of North London. Bowes Park, part of the larger district of Wood Green, is located in the London Borough of Haringey, an area known for its diverse community and rich history.

The history of Lyndhurst Road is deeply tied to the expansion of London during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Bowes Park, originally a rural area with scattered farms and estates, began to transform rapidly with the advent of the railway. The opening of the Great Northern Railway in the mid-19th century was a significant catalyst for development. The railway brought increased accessibility to central London, making Bowes Park an attractive location for residential development.

During the late Victorian era, around the 1880s and 1890s, Bowes Park saw a surge in housing construction. Streets like Lyndhurst Road were developed with the construction of terraced houses designed to accommodate the growing middle and working-class population. These houses typically featured the architectural characteristics of the period, such as bay windows, ornate brickwork, and modest gardens. The development aimed to provide affordable yet respectable housing for families seeking to move away from the crowded conditions of central London.

The early 20th century continued to witness the growth of Bowes Park as more houses were built to meet the demands of the increasing population. The area became known for its sense of community, with local shops, schools, and churches serving the residents of streets like Lyndhurst Road. The neighborhood developed a strong local identity, partly due to its geographical separation from central London and the cohesive community that emerged.

In the post-war period, Lyndhurst Road and the surrounding areas saw further changes. The 1950s and 1960s brought new waves of immigration, particularly from the Caribbean, South Asia, and later from Eastern Europe. This influx of diverse communities added new cultural dimensions to Bowes Park, enriching its social fabric. The area became known for its multicultural atmosphere, with a variety of cultural influences reflected in local businesses, cuisine, and community events.

The latter part of the 20th century and the early 21st century have seen Bowes Park, including Lyndhurst Road, undergo a process of gentrification. As London’s property market has expanded, areas like Bowes Park have become increasingly attractive to young professionals and families seeking relatively affordable housing within commutable distance to the city center. This has led to the refurbishment of many older properties and the introduction of modern amenities, while still retaining the historical character of the neighborhood.

Today, Lyndhurst Road is a microcosm of the broader Bowes Park area. It showcases a mix of architectural styles, reflecting both its Victorian origins and later developments. The street is part of a vibrant community, characterized by a blend of long-term residents and newcomers who contribute to the dynamic social landscape. Local amenities, including parks, schools, and shopping areas, enhance the quality of life for residents.

The transportation links remain a significant advantage for Lyndhurst Road. The proximity to Bowes Park railway station and Wood Green Underground station ensures that residents have easy access to central London and other parts of the city. This connectivity continues to make the area a desirable place to live.

The 1912 London, England, Electoral Registers, shows Edwin was residing at Number 83, Lyndhurst Road, Wood Green, Haringey, Tottenham, England, in the year 1912.

A man named William Oliver, was also residing at Number 83, Lyndhurst Road.

Edwin’s sister, 43-year-old, widow, Lilly Jenny Neilson nee Willats, married 41-year-old, bachelor, George Campbell Ferris, on Saturday the 23rd of October 1915, at The Register Office, Islington, London, England. Lilly gave her abode as, 35, Yesbury Road and George gave his as 87 Winchester Street and his occupation as a commercial clark. Their parents were named as, George Coell Ferris a commercial traveller (deceased) and Richard Henry Willats, an Auctioneer. Their witnesses were, Claude Eayes and J E Bailie.

Lilly remarried after the death of her first husband who left her destitute.

Jumping forward to the year 1920 in London, England, one finds a city profoundly shaped by the tumultuous events of the preceding five years. The period from 1915 to 1920 encompassed the latter part of World War I and the immediate post-war years, which brought significant social, political, and economic changes to the city.

In 1915, London was deeply embroiled in World War I. The conflict, which had begun in 1914, was by then entrenched, with the British Empire fully mobilized for the war effort. London, as the capital, played a crucial role in this mobilization. The city was a hub for military administration, logistics, and propaganda. The London streets were filled with recruitment posters, and many public buildings were repurposed for the war effort. Women entered the workforce in unprecedented numbers, taking on roles traditionally held by men who were now soldiers on the front lines. This shift began to change societal norms and laid the groundwork for future gender equality movements.

The war also brought the reality of modern warfare to London’s doorstep. The city experienced air raids by German Zeppelin airships, beginning in 1915. These raids caused both physical damage and psychological strain. Blackouts were introduced, and Londoners became accustomed to the sound of air raid sirens and the need to seek shelter. The raids highlighted the vulnerability of civilians in modern warfare and marked the first time that London had faced aerial bombardment.

By 1916, the strain of the war was palpable. The Battle of the Somme, one of the largest and bloodiest battles of the war, had a direct impact on Londoners, as many of the soldiers who fought and died there were from the city. The war's heavy toll on human life and resources led to increasing war-weariness among the population. Food shortages and rationing became more severe, leading to long queues and a thriving black market.

The Russian Revolution of 1917 had significant repercussions in London. The fall of the Tsarist regime and the rise of the Bolsheviks inspired both fear and hope among different segments of British society. The British government was concerned about the potential for socialist uprisings at home, while left-wing activists were encouraged by the revolutionary success.

The end of World War I in November 1918 brought a sense of relief and celebration, but it also ushered in new challenges. London faced the difficult task of transitioning from a wartime to a peacetime economy. Soldiers returning home needed to be reintegrated into civilian life, and there was a widespread expectation of social and political change. The war had accelerated technological and social shifts, and now these needed to be managed in peacetime.

The immediate post-war period was marked by economic difficulties. The cost of the war had been immense, leading to national debt and inflation. Unemployment rose as wartime industries contracted and soldiers returned to a labor market that could not immediately absorb them. There was widespread social unrest, including strikes by workers demanding better pay and conditions, inspired in part by the sacrifices made during the war.

The Spanish flu pandemic of 1918-1919 added to the city’s woes. The influenza pandemic swept through London, as it did through much of the world, causing a high number of deaths and overwhelming the healthcare system. Public health measures such as quarantines and the wearing of masks were introduced, but the pandemic added to the general sense of hardship and uncertainty.

Politically, the post-war period saw significant changes. The Representation of the People Act 1918 was a landmark reform that expanded the electorate by granting the vote to all men over the age of 21 and women over the age of 30 who met minimum property qualifications. This was a major step towards universal suffrage and reflected the contributions women had made during the war. The 1918 general election, known as the "Coupon Election," was the first to be held under this new system, and it resulted in a landslide victory for the coalition government of David Lloyd George.

In 1919, the Treaty of Versailles formally ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers, with significant repercussions for London. The treaty imposed harsh penalties on Germany, which led to a brief sense of justice and victory but also set the stage for future geopolitical tensions.

The year 1920 saw London beginning to stabilize after the immediate post-war turbulence. The economy started to recover, and there was a cultural shift as people sought to put the horrors of the war behind them. This period marked the beginning of the Roaring Twenties, characterized by economic prosperity and a vibrant cultural scene. Jazz music, dance halls, and new fashions symbolized a break from the past and a desire to embrace modernity.

Socially, the war had accelerated changes that continued into the 1920s. The role of women in society had been permanently altered by their wartime contributions. While many women were expected to return to traditional roles after the war, the taste of independence and economic participation had lasting effects. Women's rights movements continued to gain momentum, leading to further reforms in the following decades.

Sadly the year 1920 is when Edwin’s life draws to an end.

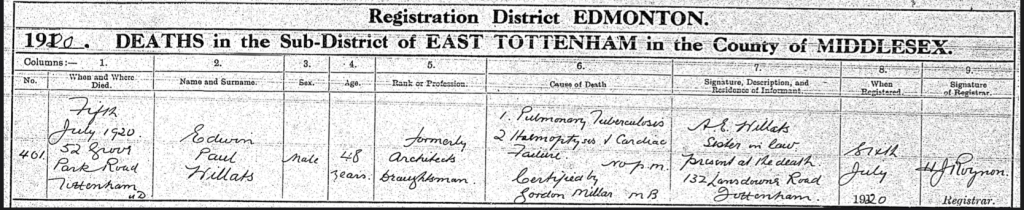

48 year old, an Architects Draftsman, Edwin Paul Willats, sadly passed away, on Monday the 5th of July 1920, at Number 52 Grove Park Road, Tottenham, Edmonton, Middlesex, England. Edwin died from Pulmonary Tuberculosis and Hemoptysis cardiac failure. Certificated by Gordon Miller mb. No post-mortem was taken. Edwins sister in-law, A E Willats of 132 Landsdowne Road, Tottenham, was present and registered Edwins death on Tuesday the 6th of July 1920, in Edmonton.

Grove Park Road, situated in Tottenham, North London, carries a rich history intertwined with the development of the area. Initially, Tottenham was a rural parish that underwent rapid urbanization during the 19th century due to its proximity to London and the growth of industry. Grove Park Road emerged as part of this urban expansion, primarily populated with Victorian and Edwardian terraced houses, reflecting the architectural styles of the time.

The residential makeup of Grove Park Road includes a mix of these historic terraced houses, characterized by their distinctive red-brick facades and bay windows. Many of these homes were originally built to accommodate the working-class population drawn to the area's industrial opportunities. Over the decades, some properties have been renovated or converted, catering to modern living standards while retaining the charm of their historical architecture.

Beyond residential dwellings, Grove Park Road is flanked by local amenities such as small shops, cafes, and community facilities, contributing to its vibrant neighborhood atmosphere. The area has also witnessed ongoing gentrification, with a growing interest from young professionals and families attracted to its convenient location and community spirit.

Transport links are robust, with nearby bus routes connecting Grove Park Road to central London and surrounding areas, enhancing its accessibility and appeal. Today, the street continues to evolve, blending its historical roots with contemporary urban living, making it a sought-after address in Tottenham's diverse and evolving landscape.

Pulmonary tuberculosis and hemoptysis, particularly in the context of cardiac failure, are serious medical conditions that require understanding both individually and in their potential interplay.

Pulmonary tuberculosis (TB) is a bacterial infection caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. It primarily affects the lungs but can also spread to other parts of the body. TB spreads through the air when an infected person coughs, sneezes, or talks, releasing droplets containing the bacteria into the air. Once inhaled, the bacteria can infect the lungs, where they multiply and cause inflammation. Symptoms of pulmonary TB include persistent cough, which may produce sputum or blood (hemoptysis), chest pain, weakness, weight loss, fever, and night sweats.

TB can vary in severity, with some cases remaining latent (asymptomatic and non-infectious) and others becoming active and potentially life-threatening. Active TB requires treatment with a combination of antibiotics over a prolonged period to eradicate the bacteria and prevent transmission. If left untreated or poorly managed, TB can cause extensive damage to the lungs and other organs, leading to complications such as respiratory failure.

Hemoptysis is the medical term for coughing up blood from the respiratory tract. It can be a symptom of various underlying conditions, including pulmonary tuberculosis. In TB, hemoptysis typically occurs when the bacteria cause erosion of blood vessels within the lungs' airways or when there is severe inflammation and tissue damage. The amount of blood coughed up can vary from streaks in sputum to large volumes, depending on the severity of the underlying condition.

When hemoptysis occurs in the context of cardiac failure, the situation becomes particularly critical. Cardiac failure, or heart failure, refers to a condition where the heart is unable to pump blood effectively to meet the body's needs. It can result from various underlying heart conditions, including coronary artery disease, hypertension, or previous heart attacks, which weaken the heart muscle over time.

In cardiac failure, the heart's inability to pump blood efficiently leads to fluid accumulation in the lungs (pulmonary congestion or edema). This fluid buildup increases pressure within the blood vessels of the lungs, making them prone to rupture and causing hemoptysis. The presence of blood in the lungs can worsen respiratory function and oxygen exchange, exacerbating symptoms of both heart failure and underlying pulmonary conditions like tuberculosis.

The combination of pulmonary tuberculosis and hemoptysis in the setting of cardiac failure represents a complex and potentially life-threatening scenario. TB already compromises respiratory function, and hemoptysis indicates significant damage to lung tissues and blood vessels. When cardiac failure is also present, the heart's diminished ability to cope with increased pulmonary pressure further complicates the situation, potentially leading to acute respiratory distress and circulatory compromise.

Management of such cases requires a multidisciplinary approach involving pulmonologists, cardiologists, infectious disease specialists, and critical care teams. Treatment aims to address both the underlying tuberculosis infection and the exacerbating factors related to cardiac failure. This may include antibiotics specific to TB, medications to manage heart failure symptoms (such as diuretics to reduce fluid overload), and supportive care to stabilize respiratory and circulatory function.

Prognosis can vary depending on the severity of the conditions, the timeliness of intervention, and the overall health of the patient. In the modern medical context, early detection, appropriate treatment, and comprehensive management strategies have improved outcomes for patients with complex medical conditions such as pulmonary tuberculosis complicated by hemoptysis and cardiac failure.

The Willats family and friends laid Edwin Paul to rest at Abney Park Cemetery, Stoke Newington, Hackney, London, England in Section, D06, Index 7S03, on Saturday the 10th July 1890.

He was buried with Baby Willats, Daisy Jean Maria Willats, Constance Margaret Thora Willats, Sophia Ann Willats and Edward Charlton.

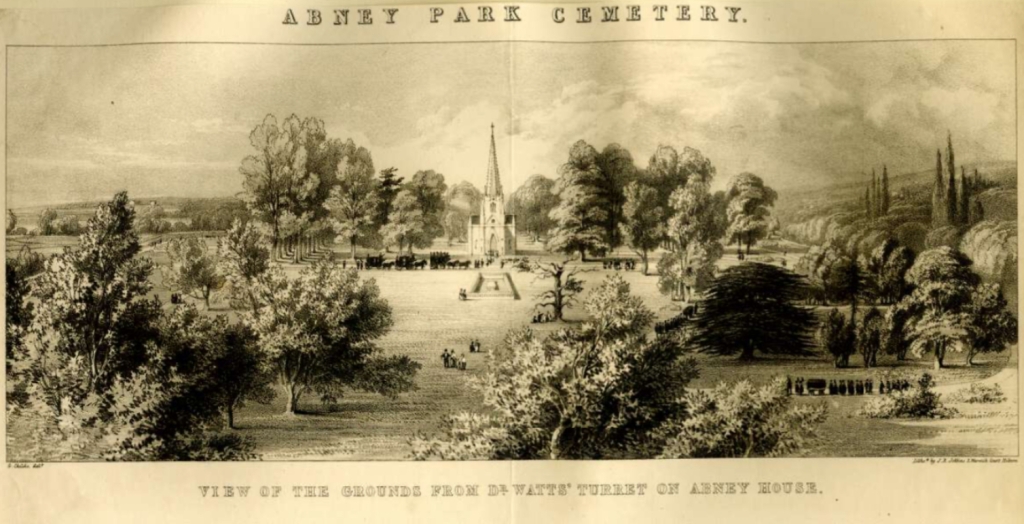

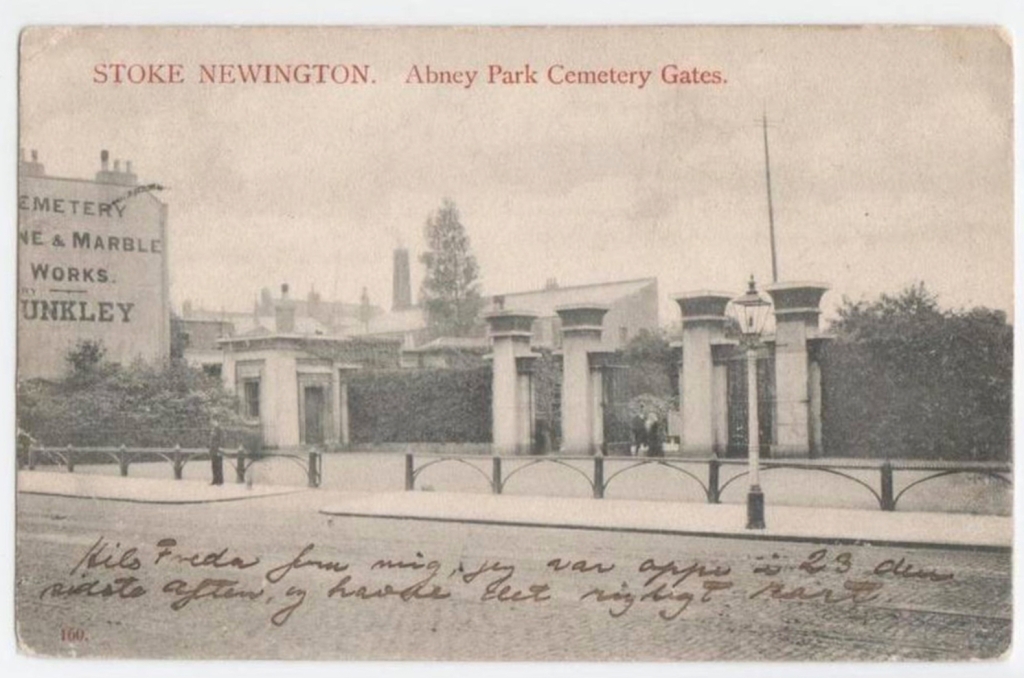

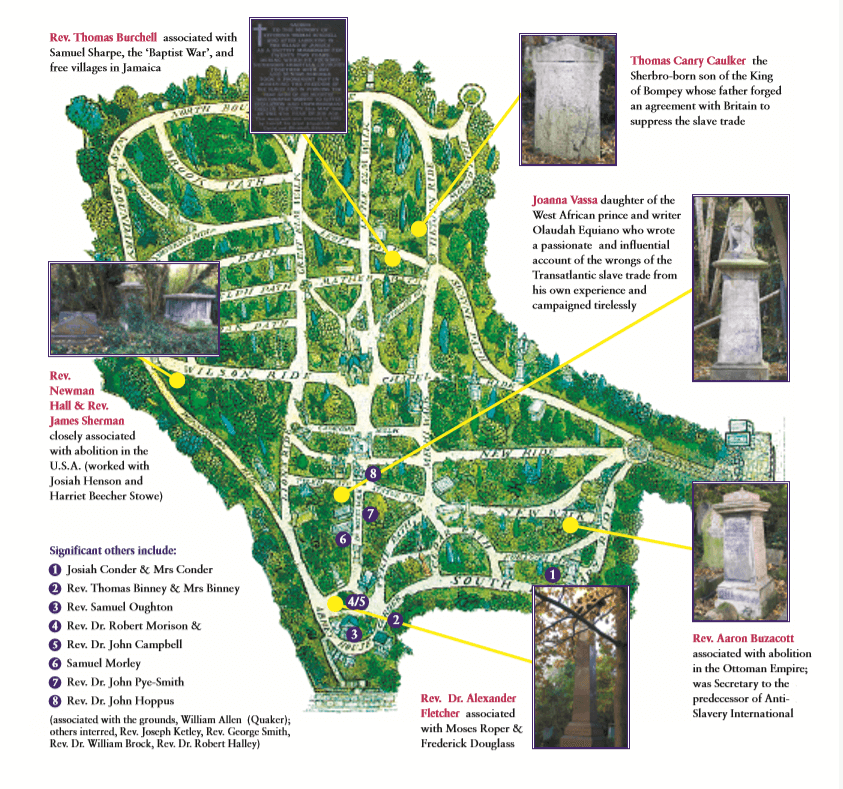

Abney Park Cemetery in Stoke Newington, London, is one of the city's "Magnificent Seven" cemeteries, established in the 19th century to address the severe overcrowding of burial grounds in central London. Its history is deeply entwined with the social, religious, and cultural developments of Victorian and Edwardian England.

The cemetery was founded in 1840 on the grounds of Abney House, a historic estate named after Sir Thomas Abney, a prominent 17th-century figure who served as Lord Mayor of London. The park itself had significant historical and botanical importance, originally landscaped by the pioneering nonconformist theologian and social reformer, Isaac Watts, who resided there. The cemetery was unique in its founding principles, being designed as a non-denominational burial ground that welcomed people of all faiths, a reflection of the liberal, nonconformist ethos prevalent among its founders.

Abney Park Cemetery was also notable for its role in the promotion of the garden cemetery movement, blending picturesque landscaping with burial spaces. It was designed to be not just a place of interment but also a public park and arboretum, intended for contemplation and leisure. The grounds featured an impressive array of trees and plants, reflecting its dual function as a place of botanical interest and repose.

Throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries, Abney Park Cemetery became the final resting place for many notable individuals, particularly those connected with nonconformist religious movements, social reform, and the arts. Prominent burials include William Booth, the founder of the Salvation Army, and his wife Catherine Booth, as well as numerous other influential figures in Victorian society.

By the time 1920 arrived, Abney Park Cemetery had already seen several decades of use and had evolved to meet the needs of a growing and changing population. The period after World War I was marked by significant social change and a heightened awareness of mortality, driven by the enormous loss of life during the war and the subsequent Spanish flu pandemic.

In terms of the cost of a burial at Abney Park Cemetery in 1920, expenses varied based on the type and location of the grave, as well as the services and materials chosen. A standard burial might include fees for the grave plot, digging and preparation, the funeral service, and the coffin. Specific cost details from that time period can be challenging to pinpoint due to variations in records and economic conditions. However, historical records suggest that the total cost for a modest burial could range from a few pounds to several pounds, which was a significant amount of money at the time, reflecting the broader economic hardships and inflationary pressures of the post-war period.

The economic context of 1920 was complex, with the aftermath of World War I leading to financial strain and adjustments in the cost of living. Funerals and burials were no exception to these broader economic trends. Families often had to balance their desire to honor their loved ones with the financial realities of the time, which could mean opting for simpler, more economical services.

As the 20th century progressed, Abney Park Cemetery faced numerous challenges, including financial difficulties and changes in burial practices. The rise of cremation and the development of new cemeteries reduced the demand for traditional burial plots. These factors, combined with the aging infrastructure and the cost of maintaining the extensive grounds, led to periods of neglect and decline.

Efforts to preserve and restore Abney Park Cemetery have been ongoing, recognizing its historical, cultural, and ecological significance. Today, the cemetery is managed as a nature reserve and historic park, providing a haven for wildlife and a green space for the local community. It remains an important heritage site, reflecting the rich history of Stoke Newington and the broader narratives of London's social and religious history.

As we conclude this journey through the life of Edwin Paul Willats, spanning the years from 1871 to 1920, one cannot help but marvel at the tapestry of experiences woven into his existence. Born into a world vastly different from the one he departed, Edwin witnessed the unfolding of history with each passing year. In his childhood, the echoes of Victorian England lingered, a time of industrial revolution and societal transformation. The streets where young Edwin played were filled with the clatter of horse-drawn carriages and the voices of a bustling city on the brink of modernity. Yet, as he matured, the landscape shifted dramatically. The turn of the century brought about rapid advancements, the advent of automobiles, the dawn of aviation, and the global upheaval of the Great War. Amidst these tides of change, Edwin faced personal trials that etched deep into his soul. The loss of his infant son, a grief that tested the very fibers of his being, spoke volumes of his resilience and the enduring strength found in his love for Nellie. Their bond, forged in the crucible of life's hardships, stood unwavering, a beacon of hope and solace through the storms of their time. As we bid farewell to this chapter of Edwin's story, we are reminded of the timeless truths that transcend generations, the courage to face adversity, the steadfastness of love, and the enduring spirit that navigates the currents of history. Edwin Paul Willats, a man of his era, now rests in the embrace of eternity, leaving behind a legacy woven not only in the fabric of his family's history but in the broader tapestry of a changing world. May his journey inspire us to cherish our own stories, knowing that each life, no matter how ordinary or extraordinary, leaves an indelible mark upon the canvas of time.

Rest Peacefully,

Edwin Paul Willats,

1871-1920

Until next time,

Toodle pip,

Yours Lainey.

🦋🦋🦋

I have brought and paid for all certificates,

Please do not download or use them without my permission.

All you have to do is ask.

Thank you.