Welcome back to our exploration of Percy Sidney Willats' extraordinary life, as pieced together through the documents, and records. In Part 1, we delved into the early years of Percy’s life, uncovering the foundational experiences and relationships that shaped his character and ambitions. Now, in Part 2, we move deeper into the narrative, focusing on the pivotal years of his middle life, a time marked by both personal transformation and the broader societal shifts that defined the early 20th century.

Hopefullythrough my research and documentation, we’ll see how Percy navigated a world in flux. Along the way, we’ll consider how his life story echoes the challenges, aspirations, and complexities of his time.

Let’s step once more into the life of Percy Sidney Willats, where history and personal legacy intertwine.

The Life Of,

Percy Sidney Willats,

1875-1945,

Through Documentation, Part 2.

Welcome back to the year 1909.

Life in England in 1909 was a tapestry of contrasts, shaped by rapid industrial progress, entrenched social hierarchies, and the Edwardian spirit of elegance and optimism. This was a time when the country stood at the crossroads of tradition and modernity, with a monarchy that symbolized continuity, a society grappling with reform, and technological advancements transforming daily life.

The monarchy in 1909 was headed by King Edward VII, who had been on the throne since 1901. His reign, often referred to as the Edwardian era, was characterized by a more relaxed and cosmopolitan tone than the Victorian period before it. The king himself was a figure of charisma and indulgence, a patron of the arts and an advocate of diplomacy. His influence extended to social norms, with the upper classes emulating his opulent lifestyle, while the middle and working classes admired him as a symbol of national pride.

Parliament in 1909 was dominated by significant political and economic debates. The Liberal Party, led by Prime Minister Herbert Henry Asquith, was in power, pursuing an ambitious program of social reform aimed at addressing the deep inequalities of the time. A central issue was the “People’s Budget,” introduced by Chancellor of the Exchequer David Lloyd George. This landmark budget proposed increased taxes on land and wealth to fund social programs such as old-age pensions and national defense. It sparked fierce opposition from the Conservative-dominated House of Lords, leading to a constitutional crisis that highlighted the growing tension between the aristocracy and emerging democratic ideals.

Clothing in 1909 reflected the Edwardian fascination with elegance and detail. For women, fashion was characterized by flowing, floor-length dresses with high necklines, cinched waists, and elaborate hats adorned with feathers and ribbons. The silhouette was often achieved through corsetry, creating an “S-curve” shape that was both restrictive and glamorous. Men’s fashion included tailored suits, waistcoats, and bowler or top hats for formal occasions. The working class wore more practical and less elaborate garments, often made of wool or cotton and designed for durability rather than style.

Transportation was rapidly evolving, with the automobile becoming increasingly accessible to the wealthy, though horses and carriages remained common in cities and rural areas. The London Underground was expanding, providing a faster means of commuting for urban dwellers. Bicycles were also a popular and affordable mode of transportation. Railways connected towns and cities across the country, while steamships dominated international travel, facilitating commerce and leisure journeys for the affluent.

Social standing in 1909 was rigidly stratified, with the upper classes enjoying immense privilege and the working classes enduring significant hardships. The rich lived in large townhouses or country estates, employing numerous servants to maintain their comfortable lifestyles. They attended grand balls, lavish dinners, and cultural events. Meanwhile, the poor often lived in overcrowded and unsanitary conditions in urban slums. The stark inequalities prompted growing calls for social reform, and movements advocating for workers’ rights and women’s suffrage gained momentum.

Sanitation was a pressing issue, especially in industrial cities. Although efforts to improve public health had led to better sewer systems and clean water supplies, overcrowding in poor areas still led to outbreaks of disease. Advances in medicine, including the widespread use of antiseptics, began to improve health outcomes, but access to care was uneven.

Heating and lighting in homes varied depending on wealth. The rich enjoyed coal-fired central heating and gas or electric lighting, which was becoming more widespread in urban areas. The poor, by contrast, relied on coal or wood fires for heat and oil lamps or candles for light, which were less efficient and more hazardous.

Communication in 1909 was dominated by the postal service, which was highly efficient and widely used for both personal and business correspondence. Telephones were becoming more common but were still a luxury for most households. Newspapers were a primary source of information and gossip, with several daily and weekly publications catering to different social classes. Gossip and news often spread through informal networks, including pubs, markets, and workplaces.

Historical events of 1909 underscored the tensions and transformations of the period. The suffragette movement intensified, with activists such as Emmeline Pankhurst and her followers engaging in protests and acts of civil disobedience to demand women’s right to vote. The People's Budget debate highlighted the clash between traditional aristocratic power and modern democratic ideals. Meanwhile, the foundations of modern aviation were being laid, with Louis Blériot making the first flight across the English Channel in July, capturing the public imagination and heralding a new age of exploration.

More importantly to us, Percy and his new wife Sophia, were newly weds and starting out on their journey together as a couple. It would have been an exciting time for them as they settled into their new life together, learning more about each other as well as learning how to navigate life as a married couple. However it wasn’t long before two become three, and their lives would change again.

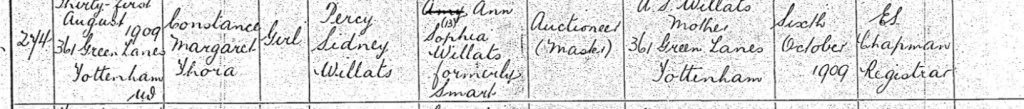

Percy Sidney Willats and Sophia Ann Willats nee Smart, firstborn daughter, Constance Margaret Thora Willats was born on Tuesday the 31st of August 1909, just over a month after they wed. Constance was born at Number 361, Green Lanes, Tottenham, Edmonton, Middlesex England.

Sophia Ann registered Constance's birth on the 6th of October 1909.

Sophia gave her husband Percy’s occupation as a master auctioneer and their abode as Number 361, Green Lanes, Tottenham.

Sophia gave her name as Ann Sophia.

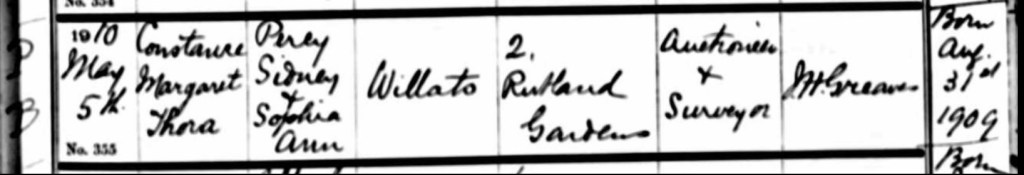

Percy and Sophia privately baptised Constance Margaret Thora Willats, on Thursday the 5th of May 1910, at St. Paul, Harringay, Middlesex, England. Her father Percy, occupation was given as a auctioneer and surveyor, and their abode to Rutland Gardens.

The Church of St Paul the Apostle, Wightman Road, Harringay, London, N4, serves the parish of Harringay in north London. In ecclesiastical terms the parish is part of the Edmonton Episcopal Area of the Diocese of London. In political terms the parish is in the London Borough of Haringey.

In 1984 the nineteenth-century church building was destroyed by fire, and the present iconic building was opened in 1993, designed by London architects Peter Inskip and Peter Jenkins.

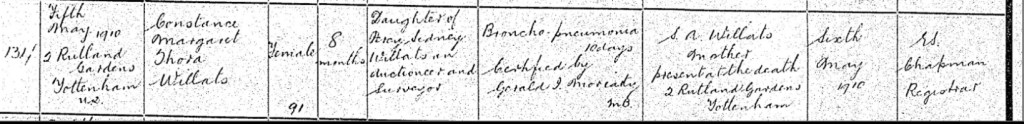

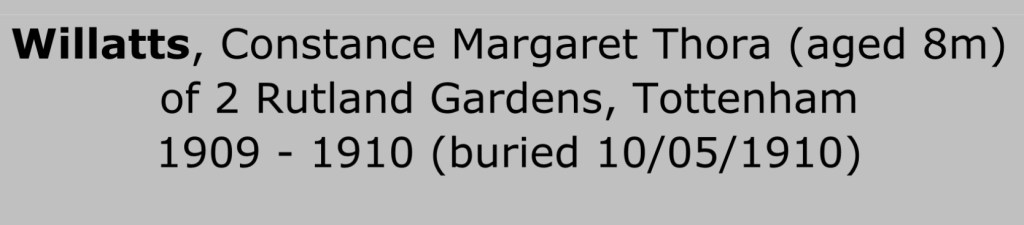

Tragically, Percy and Sophia’s joy was heartbreakingly brief. Their beloved daughter, 8-month-old Constance Margaret Thora Willats, passed away on Thursday, the 5th of May, 1910, at the family home at Number 2, Rutland Gardens, Tottenham, Edmonton, Middlesex, England. Little Constance succumbed to bronchitis pneumonia after a brave struggle lasting ten days.

Sophia Ann Willats, Constance’s devoted mother, was present during her final moments and bore the heavy burden of registering her daughter’s death the following day, on the 6th of May, 1910. Despite her grief, she dutifully recorded her husband, Percy Sidney Willats, as Constance’s father, listing his profession as an auctioneer and surveyor. Their family home, Number 2, Rutland Gardens, Tottenham, where they had shared fleeting moments of joy with their cherished daughter, stood witness to their unimaginable loss.

This tender yet sorrowful chapter in their lives speaks of the fragility of life and the profound strength of love, even in the face of overwhelming heartbreak.

Rutland Gardens is a residential street located in the Harringay area of North London, within the London Borough of Haringey. The street is approximately 396 meters in length and is situated in the N4 postal district.

The history of Rutland Gardens dates back to the late 19th century. The area was originally part of a larger estate owned by the Shakespear family. In the early 1770s, a large plot on the west side was leased for the construction of a mansion later known as Stratheden House. By the early 1790s, the existing house was rebuilt or improved by George Shakespear, a master carpenter and builder.

In the 1860s, the estate was sold to Mitchell Henry, an Anglo-Irish businessman and politician. Henry carried out significant improvements to Stratheden House and began developing the Kent House estate. In 1870, Kent House was demolished, and plans were made to build a road (Rutland Gardens) and houses on the site. The development included the construction of mansions and a mews, with Rutland Gardens Mews being created as part of this process.

Today, Rutland Gardens is a residential street characterized by its Victorian architecture. The area has undergone various changes over the years, with some original buildings replaced or converted. The street is well-connected to public transportation, providing residents with access to various amenities and services in the surrounding areas.

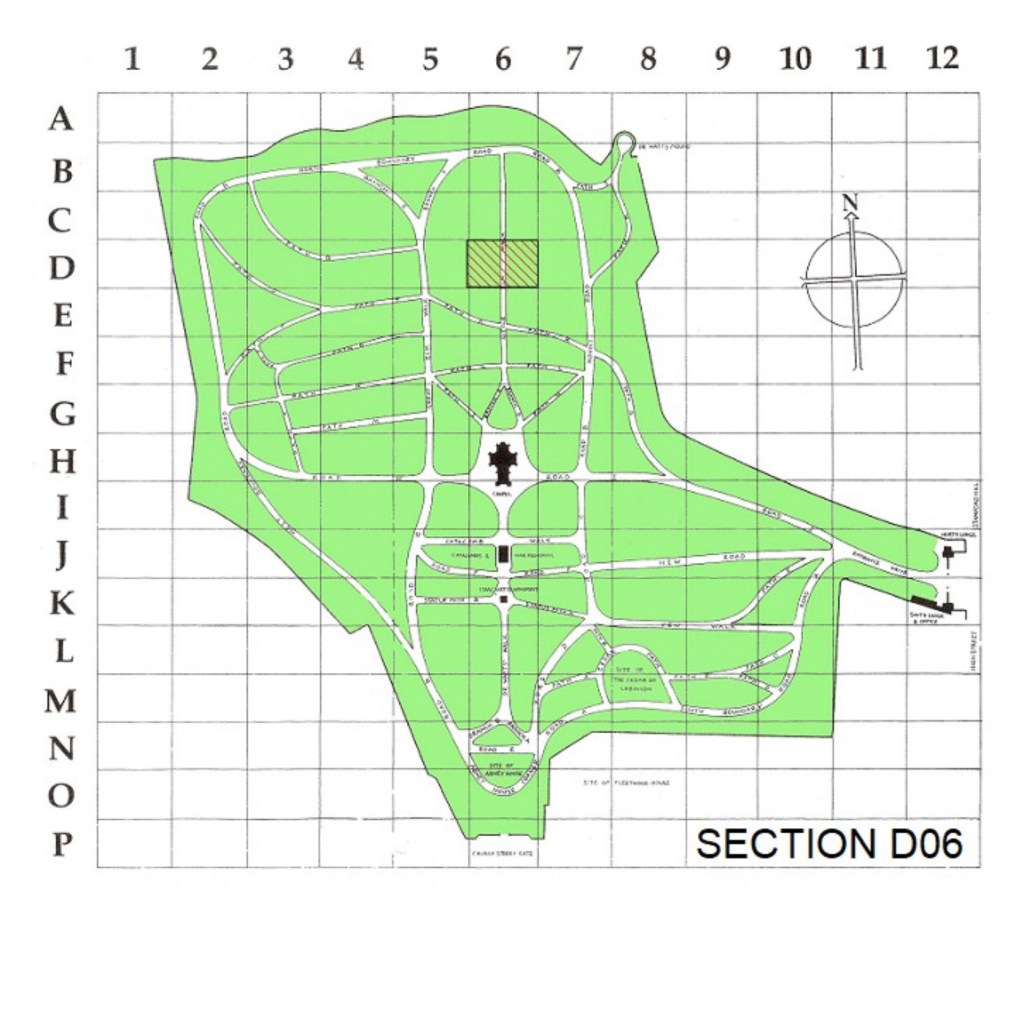

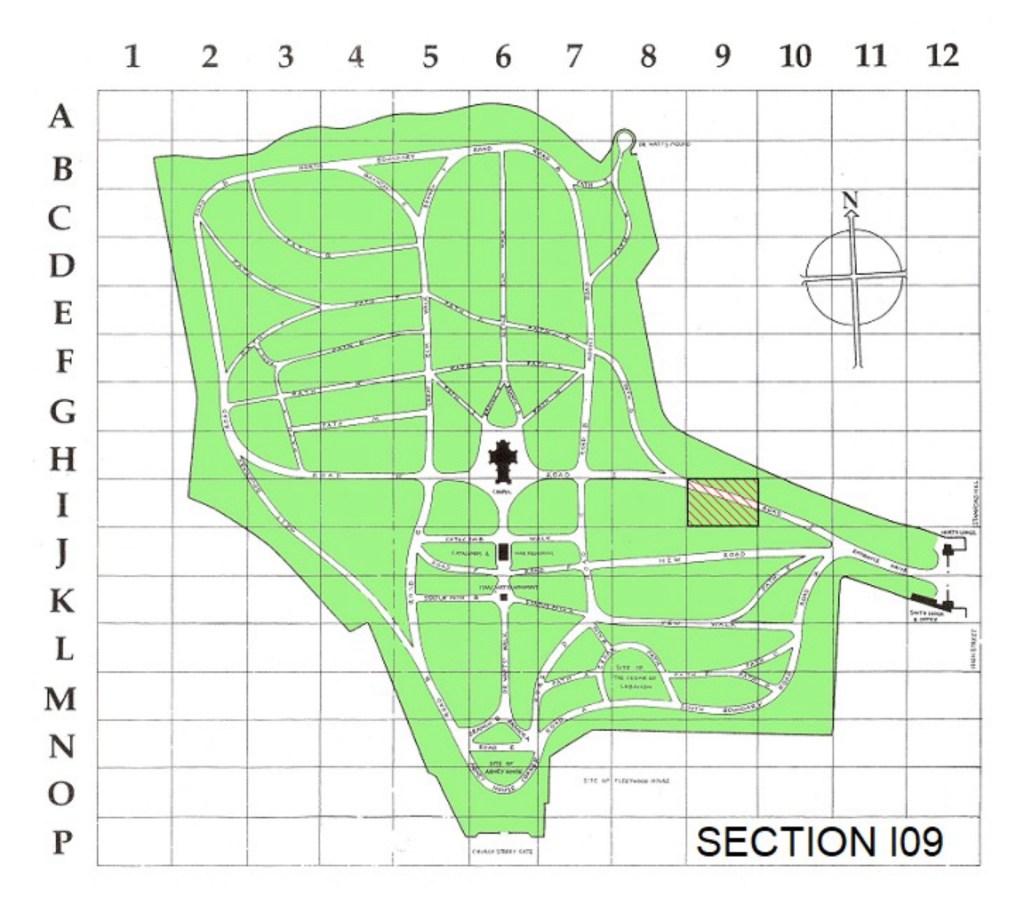

With deep sorrow, little Constance Margaret Thora Willats was laid to rest on Tuesday, the 10th of May, 1910, at Abney Park Cemetery, Stoke Newington, Middlesex, England. She was placed in Grave 092432, Section D06, where she now rests alongside her loved ones—Baby Willats, Daisy Jean Maria Willats, Edwin Paul Willats, Sophia Ann Willats, and Edward Charlton.

This final resting place, shared with family members, serves as a quiet reminder of the profound love and grief that her parents, Percy and Sophia, carried in their hearts. It is a place where their precious daughter, though gone too soon, is forever remembered.

After enduring the unimaginable heartbreak of losing their precious daughter, Percy and Sophia found hope once more with the news that they were expecting again. Their joy was renewed with the birth of their son, Sidney Richard Willats, on Wednesday, the 22nd of February, 1911, at their home, Number 2, Rutland Gardens, Tottenham, Edmonton, Middlesex, England.

Sophia Ann, in the midst of her deep emotions, registered Sidney’s birth on Tuesday, the 4th of April, 1911. In doing so, she lovingly listed Percy’s occupation as an auctioneer and estate agent’s clerk, and their home address as Number 2, Rutland Gardens, Tottenham. Sophia also gave her own name as Ann Sophia, a subtle reminder of the strength and resilience she had shown as she navigated both profound loss and new beginnings.

Sidney’s birth brought a glimmer of light back into their lives, a beautiful reminder that amidst grief, there can still be room for hope and love.

Following Sidney's birth, Percy, Sophia, and their young son, Sidney Richard, along with their nephew, Herbert John Champion, were living together at Number 2 Rutland Gardens, Harringay, Tottenham, Middlesex, England, on Sunday, the 2nd of April, 1911, when the 1911 census was completed.

Percy was working as an estate agent, while Herbert was employed as a clerk in a motor car works.

The family made their home in a modest four-room dwelling at Number 2 Rutland Gardens, a place where they found solace and comfort in one another's company, despite the challenges they had faced. The home, though small, was filled with love, and it was here that they began to rebuild their lives together.

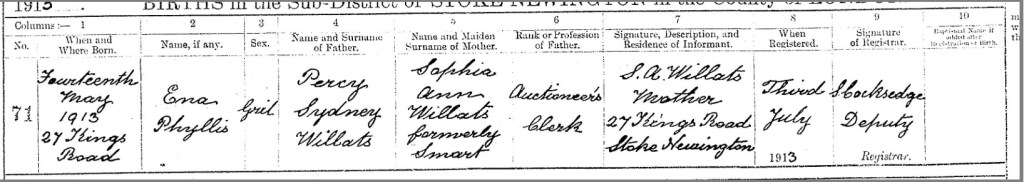

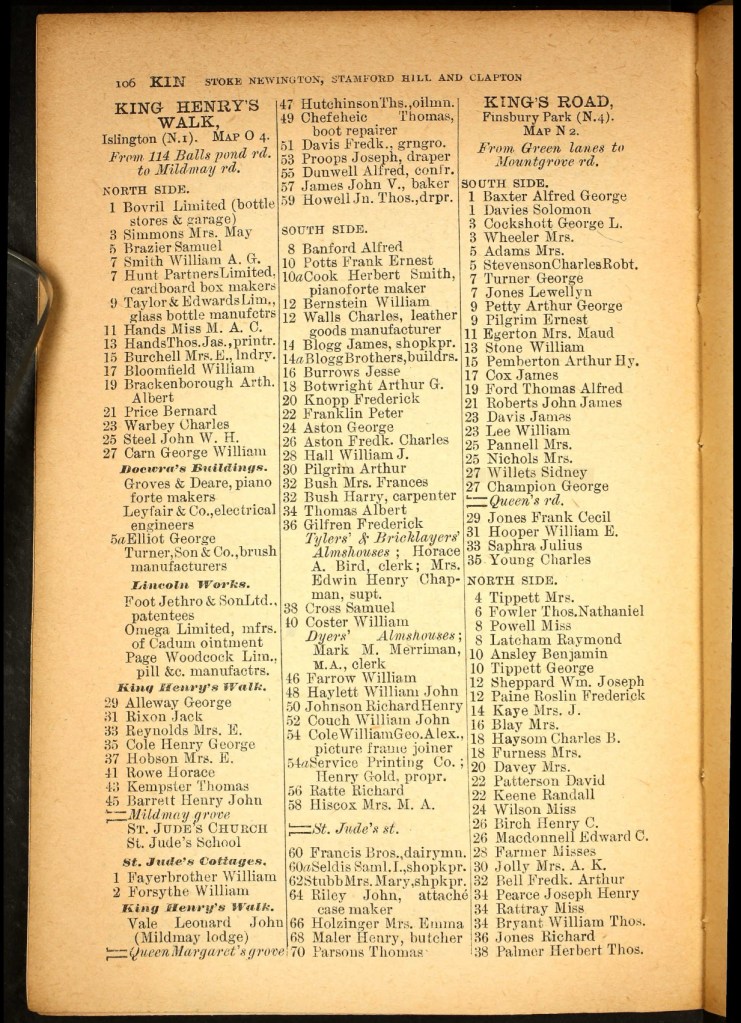

Jumping forward to 1913, Percy and Sophia, daughter Ena Phyllis Willats was born on Wednesday the 14th of May 1913, at the family’s home, Number 27, Kings Road, Stoke Newington, Middlesex, England. Ena mum Sophia, registered her birth on Thursday the 3rd of July 1913. Sophia gave her husband Percy’s occupation as an auctioneer clark, and their abode as Number 27, Kings Road, Stoke Newington.

Kings Road is a street located in the Stoke Newington area of North London, within the London Borough of Hackney. Stoke Newington, historically a small village, became part of London in the 19th century. The area experienced significant development during the Victorian era, with many large houses built for the expanding population. Kings Road, like many streets in Stoke Newington, reflects this period of growth and development.

In the 18th century, Stoke Newington became a fashionable area with well-built houses, some of which can still be seen today. The village was known for its picturesque surroundings and attracted affluent residents. The 19th century saw further expansion, with the construction of new roads and housing to accommodate the growing population. Kings Road was part of this development, contributing to the area's transformation into a suburban neighborhood.

Today, Kings Road is a residential street that retains much of its historical character. The area has undergone gentrification in recent years, with new businesses and amenities enhancing its appeal. Stoke Newington, including Kings Road, is known for its multicultural community and vibrant local culture. The street is lined with a mix of period properties and modern developments, reflecting the area's rich history and ongoing evolution.

In 1913, London was a bustling metropolis with a rapidly growing economy, and the auction industry was an important part of the commercial landscape. Auctioneers and clerks played crucial roles in the buying and selling of goods at auction houses, which were increasingly popular venues for transactions ranging from fine art and antiques to livestock and property. Working as an auctioneer’s clerk during this period involved a mix of administrative duties, customer service, and supporting the auctioneer during sales. The job required specific skills, including attention to detail, an understanding of the auction process, and often a degree of familiarity with specialized goods.

An auctioneer’s clerk in 1913 would have had a range of responsibilities to ensure the smooth running of the auction process. One of the primary duties was to assist the auctioneer by keeping detailed records of the lots being sold, including the sale prices, names of the buyers, and other pertinent details. They would also handle the paperwork associated with each lot, ensuring that buyers received the correct invoices and receipts, and that sellers were paid in a timely manner.

Clerks had to work quickly and efficiently, often under pressure, since auctions were fast-paced events. They would need to accurately write down the bids as they came in, sometimes with the assistance of a scribe or shorthand to keep up with the pace. In some cases, clerks would also assist in organizing the catalogues for the auction, ensuring that all items were listed correctly and described appropriately.

Auction houses in London during the early 20th century were busy and often filled with anticipation. The auctioneer would take center stage, commanding the room with an authoritative voice as they guided the sale. The atmosphere could be tense or lively, depending on the type of auction. Fine art auctions or auctions of estates often attracted wealthy buyers and socialites, and there was a certain level of exclusivity about these events. The auction house would be meticulously arranged, with items often on display to entice potential buyers. At the same time, livestock auctions or other more utilitarian sales might be rowdier and more utilitarian, with a focus on efficiency over ceremony.

The auctioneer’s clerk, while not necessarily in the spotlight, would be in constant motion, liaising with buyers, sellers, and other staff. The buzz of conversations, the rapid bidding, and the occasional clink of coins or the sound of a gavel striking would form the backdrop for the clerk’s daily work.

To work as an auctioneer’s clerk in 1913, individuals needed to be highly organized, reliable, and quick-thinking. Knowledge of the goods being sold would have been a valuable asset, especially if the clerk worked in a specialized field like fine art or antiques. A clerk needed to have strong numerical and writing skills to keep up with the auction process, record all bids accurately, and handle any disputes or discrepancies that might arise.

Additionally, clerks would often be responsible for managing post-sale arrangements, including payment collection, arranging for the delivery of sold goods, and ensuring that buyers and sellers were satisfied with the terms of the auction. It was also common for auctioneer clerks to have a solid understanding of legal and financial procedures surrounding auctions, including contracts and taxes.

In terms of working conditions, clerks worked long hours, often including evenings or weekends, as auctions were typically held during these times. The role demanded considerable attention to detail and the ability to work in a high-pressure environment. Clerks often worked closely with other members of the auction house staff, including the auctioneer, the cataloguers, and sometimes the porters or security staff.

As for pay, auctioneer clerks in 1913 would likely have been paid a modest wage, which varied depending on the auction house and the clerk’s experience. While exact pay rates are difficult to pinpoint, clerks in this era were typically earning between £1 and £3 a week for regular office work, though those employed at more prestigious auction houses or involved in high-value sales might have received higher compensation. Auctioneers, by contrast, could earn a higher income, often taking a percentage of the sale price of goods sold, but their clerks were not likely to see the same level of financial reward.

The auction business in London in 1913 was part of a broader trend of growing consumerism and an expanding middle class. Auctions were a key method for buying and selling valuable goods, and their popularity increased with the rise of industrialization, which allowed for the mass production of goods while simultaneously making rarer items more desirable. Auction houses like Sotheby’s and Christie's were already well-established, and the auction industry was known for attracting wealth and social distinction.

The early 20th century was also a period of great social change in Britain, with rising movements for workers' rights and the push for better conditions and pay for employees in various sectors. Although auctioneer clerks likely worked in more traditional, hierarchical settings with a strong focus on efficiency and precision, the broader social and economic context would have been shaping attitudes toward labor and compensation.

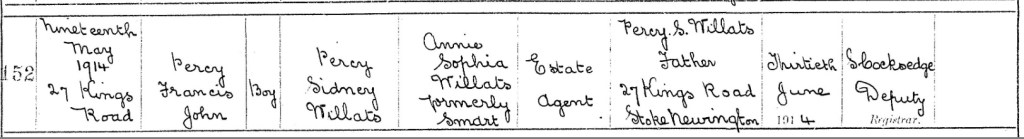

The following year, Percy and Sophia, were once again expecting, their son, Percy Francis John Willats, was born on Tuesday the 19th of May 1914, at the family home, Number 27, Kings Road, Stoke Newington, Middlesex, England.

Percy, registered Percy’s birth on Saturday the 13th of June 1914.

He gave is occupation as an Estate Agent, and their abode as Number 27, Kings Road, Stoke Newington.

Percy gave his wife’s name as Annie Sophia.

Two years later, Percy’s Sister, 43-year-old, widow, Lilly Jenny Neilson nee Willats, married 41-year-old, bachelor, George Campbell Ferris, on Saturday the 23rd of October 1915, at The Register Office, Islington, London, England. Lilly gave her abode as, 35, Yesbury Road and George gave his as 87 Winchester Street and his occupation as a commercial clark.

Their parents were named as, George Coell Ferris a commercial traveller (deceased) and Richard Henry Willats, an Auctioneer.

Their witnesses were, Claude Eayes and J E Bailie.

Lilly’s name was given as Lillian Jenny.

The following year Percy Sidney and Sophia's, son Walter Frederick Willats was born on Saturday the 16th of September 1916, at Number 27 Kings Road, Stoke Newington, Hackney, Middlesex, England.

Sophia registered Walters birth on the 16th of November 1916.

She gave her husband Percy’s occupation as an insurance clerk, and their abode as 27 Kings Road, Stoke Newington.

Jumping forward to the year 1920.

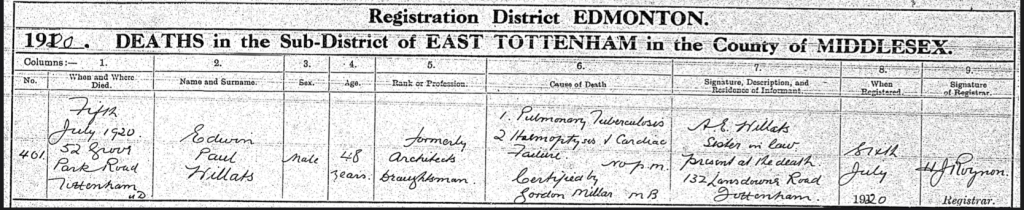

Percy’s brother, 48-year-old, Architects Draftsman, Edwin Paul Willats, sadly passed away, on Monday the 5th of July 1920, at Number 52, Grove Park Road, Tottenham, Edmonton, Middlesex, England.

Edwin died from Pulmonary Tuberculosis and Hemoptysis cardiac failure. No post-mortem was taken.

Edwin's sister-in-law, Amelia Ellen Willats nee High, of 132, Landsdowne Road, Tottenham. was present and registered Edwin's death on Tuesday the 6th of July 1920, in Edmonton.

Pulmonary tuberculosis (TB) and hemoptysis due to cardiac failure are two significant health concerns that, though distinct, can sometimes be related in the context of a patient’s overall health. These conditions each have their own complex histories and pathophysiologies, but they also occasionally intersect when one exacerbates the other.

Pulmonary tuberculosis is a contagious bacterial infection primarily affecting the lungs, though it can spread to other parts of the body. It is caused by *Mycobacterium tuberculosis*, a slow-growing bacterium that can persist in the body for years, often in a latent form. The history of tuberculosis dates back centuries, with references to a disease resembling TB found in ancient Egyptian mummies, and it was known in the 19th century as "consumption" due to the weight loss and wasting it caused in those affected. The understanding of tuberculosis began to improve in the late 19th century, particularly after the identification of *Mycobacterium tuberculosis* by Robert Koch in 1882. His discovery led to a revolution in the diagnosis and treatment of the disease. Despite this breakthrough, TB remained a global health threat, especially in the 20th century, due to overcrowding, poor living conditions, and the advent of antibiotic-resistant strains.

The main symptoms of pulmonary tuberculosis include a persistent cough, chest pain, night sweats, fever, weight loss, and fatigue. In some cases, people with advanced pulmonary TB may experience hemoptysis, which is the coughing up of blood. This occurs because the infection damages lung tissue, causing blood vessels in the lungs to rupture. Hemoptysis is a serious complication and is often a sign that the disease has progressed significantly, possibly leading to the need for more aggressive treatments like surgery or a prolonged course of antibiotics. The treatment of TB typically involves a combination of antibiotics, such as isoniazid, rifampin, and pyrazinamide, over several months, and the advent of drug-resistant strains has created new challenges for TB management.

Hemoptysis is also a key symptom that can arise in various conditions beyond tuberculosis, and its relationship with cardiac failure is an important one. Cardiac failure, particularly left-sided heart failure, can lead to a backup of blood in the pulmonary circulation, resulting in increased pressure in the blood vessels of the lungs. This increased pressure can cause the fragile vessels in the lungs to burst, leading to blood in the airways, which is then coughed up as hemoptysis. In cases of congestive heart failure, the heart’s inability to pump blood effectively causes fluid to accumulate in the lungs, leading to pulmonary edema, a condition that can also result in hemoptysis.

The historical understanding of heart failure dates back to the early days of medicine, but it wasn’t until the 19th century that the mechanistic understanding of cardiac failure began to evolve. The term "heart failure" was first used in the medical literature in the early 1800s, but the pathophysiology was largely unknown until the 20th century. In the 20th century, especially after the advent of modern diagnostic technologies such as echocardiography and chest X-rays, it became clearer how heart failure could lead to fluid buildup in the lungs, and ultimately to symptoms like shortness of breath and hemoptysis.

While TB and heart failure are separate conditions, the coexistence of both in a single patient can significantly complicate diagnosis and treatment. In regions with high TB prevalence, chronic cardiac failure may be exacerbated by TB-related damage to the lungs or vice versa. For example, a patient with active TB who also has left-sided heart failure may face an increased risk of hemoptysis as a complication of both conditions. The overlap of these two diseases makes management more challenging, as treatment for heart failure may exacerbate the progression of tuberculosis, while anti-TB treatments can have cardiovascular side effects.

In terms of treatment, managing a patient with both pulmonary tuberculosis and cardiac failure requires a careful, multidisciplinary approach. Treatment for TB typically involves a prolonged course of antibiotics, and for heart failure, medications like diuretics, beta-blockers, and ACE inhibitors are often used to reduce fluid buildup and help the heart pump more effectively. The simultaneous management of both conditions requires close monitoring, as certain drugs used for TB treatment can interact with heart failure medications, and the effects of one disease can influence the other. Hemoptysis in this context often signals a worsening of either the pulmonary tuberculosis or the heart failure and may necessitate emergency intervention, such as the use of vasodilators, respiratory support, or, in severe cases, surgical interventions.

The history of both diseases reflects the progress made in understanding their underlying mechanisms and treatment strategies, though both remain global health issues. Tuberculosis continues to be a major concern in many parts of the world, particularly in low-income countries where it remains the leading cause of death from a single infectious agent. Cardiac failure, on the other hand, is increasingly common in high-income countries, where lifestyle factors like diet and exercise, as well as an aging population, contribute to its prevalence. The intersection of these two diseases represents a significant challenge in modern medicine, requiring integrated care to optimize patient outcomes.

The Willats family and friends laid Edwin Paul Willats, to rest at, Abney Park Cemetery, Stoke Newington, Hackney, London, England, in Section, D06, Index 7S03, on Saturday the 10th of July, 1920.

He was buried with Baby Willats, Daisy Jean Maria Willats, Constance Margaret Thora Willats, Sophia Ann Willats and Edward Charlton.

More heartbreak followed, when Percy's brother, 63-year-old, Insurance Manager, Francis Montague Allan Willats, sadly passed away on Sunday the 19th of September 1920, at Wymondley Heathgate, Hendon, Middlesex, England.

He died from Chronic interstitial hepatitis (several years), No post-mortem was taken.

Francis’s son, Allen Montague Willats was present and registered his death on Tuesday the 22nd of September, 1920, in Hendon.

Chronic interstitial hepatitis is a form of liver disease characterized by the inflammation and scarring of the liver's connective tissue, or interstitium. The condition usually develops over time and can lead to significant liver dysfunction if left untreated. It differs from other forms of hepatitis, like viral hepatitis, in that it is primarily defined by the long-standing inflammation of the liver's interstitial space, which is the area surrounding the liver’s functional cells, or hepatocytes.

The term "hepatitis" refers to liver inflammation, while "interstitial" refers to the tissues surrounding the liver's central structures. In chronic interstitial hepatitis, the inflammation extends into the liver's connective tissue, causing fibrosis (scarring) and potentially progressing to cirrhosis. The disease may be asymptomatic in its early stages but can eventually lead to jaundice, fatigue, abdominal pain, and signs of liver failure as it progresses.

The causes of chronic interstitial hepatitis can be quite diverse. It may result from autoimmune disorders, chronic viral infections (such as hepatitis B or C), drug-induced liver injury, or excessive alcohol consumption. In some cases, the exact cause remains unknown, a condition known as idiopathic chronic interstitial hepatitis. It can also be associated with conditions like non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), where fat accumulation in liver cells leads to inflammation and scarring.

Histologically, chronic interstitial hepatitis is characterized by a gradual infiltration of inflammatory cells (such as lymphocytes and plasma cells) into the liver’s connective tissue. This inflammatory response leads to fibrosis, which, over time, can disrupt the normal architecture of the liver, impairing its ability to function properly. The extent of fibrosis can be assessed through liver biopsy, where pathologists evaluate the liver tissue under a microscope.

The history of chronic interstitial hepatitis is intertwined with the broader understanding of liver diseases. Hepatitis as a condition has been recognized for centuries, but it was only in the 20th century that advances in medicine began to classify and understand the different types and causes of hepatitis in more detail. In the early 1900s, liver diseases were often misclassified due to limited diagnostic tools. It wasn’t until the 1950s and 1960s, with the development of more advanced techniques like liver biopsy and improved histological staining methods, that physicians could more accurately diagnose chronic interstitial hepatitis. In the 1970s, as the understanding of autoimmune diseases grew, chronic interstitial hepatitis became more closely linked to autoimmune hepatitis, where the immune system mistakenly attacks the liver.

Over the years, treatment strategies for chronic interstitial hepatitis have evolved. In the early stages of the disease, it can sometimes be managed with corticosteroids or immunosuppressive drugs, especially in cases where autoimmune hepatitis is involved. Lifestyle changes, including the cessation of alcohol consumption and careful management of viral hepatitis, are also crucial for slowing the progression of the disease. In more advanced stages, treatment may focus on managing complications like liver failure, and in severe cases, a liver transplant may be necessary.

Chronic interstitial hepatitis remains a significant challenge in hepatology, as it can often present subtly and progress to more severe stages without early detection. The development of new diagnostic tools and treatments continues to improve outcomes for those affected by this condition, but ongoing research is necessary to better understand its underlying mechanisms and optimal management strategies.

Percy and family laid Francis Montague Willats, to rest, on Tuesday the 21st September 1920, at Highgate Cemetery, Camden, London, England, grave reference /40479. He was buried with 7 others, Frances Jessie Willats, buried 16th September 1976. Allan Montague Willats, buried 2nd March 1968. Dorothy Beaumont Willats, buried 9th April 1965. Margaret Eliza Craddock, buried 1st January 1961. David Allan Willats, buried 5th February 1948. Margaret Jane Willats, 25th October 1937 and Horace Lennan Willats, buried 19th December 1916.

Highgate Cemetery, located in Camden, London, England, is one of the most famous and atmospheric burial grounds in the United Kingdom. Established in 1839 as part of a solution to London's overcrowded graveyards, it is steeped in history and Victorian Gothic charm. The cemetery covers approximately 37 acres and is divided into two sections: the East Cemetery and the West Cemetery, each with its unique features and attractions.

The cemetery was designed as part of the "Magnificent Seven," a group of private cemeteries established around London to address public health concerns and provide a dignified resting place for the dead. Highgate quickly became a fashionable burial site for Victorian society, known for its picturesque landscaping, grand mausoleums, and elaborate monuments. Its design reflects the Romantic ideals of the time, blending natural beauty with architectural splendor.

The West Cemetery is known for its iconic Gothic architecture, winding pathways, and dense greenery. Notable features include the Egyptian Avenue, a passage flanked by obelisks and tombs in the style of ancient Egypt, and the Circle of Lebanon, a ring of crypts surrounding a centuries-old cedar tree. The East Cemetery, which was opened later, is more modern in layout but still contains numerous historic graves.

Highgate Cemetery is the final resting place of many notable figures from various walks of life. One of its most famous residents is Karl Marx, the German philosopher, economist, and revolutionary socialist. His grave, located in the East Cemetery, features a bust of Marx and the inscription "Workers of all lands, unite!" Another prominent figure buried in the East Cemetery is George Eliot, the pen name of Mary Ann Evans, a celebrated Victorian novelist and social critic.

Other notable figures include Michael Faraday, the pioneering scientist whose work on electromagnetism and electrochemistry laid the foundations for modern physics; Lucian Freud, a leading 20th-century painter; and Christina Rossetti, a poet associated with the Pre-Raphaelite movement. In the West Cemetery, one can find the graves of Alexander Litvinenko, a former Russian agent whose death by poisoning made international headlines, and Douglas Adams, the author of *The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy*, whose gravestone humorously invites visitors to "know where their towel is."

Highgate Cemetery has also captured the imagination of writers, filmmakers, and artists due to its eerie beauty and historical significance. It has been featured in literature and cinema, often as a symbol of mystery or the macabre. Its overgrown paths and ivy-clad monuments contribute to its reputation as a place of haunting yet poetic allure.

Today, Highgate Cemetery is a Grade I listed site, recognized for its architectural and historical importance. It remains a working cemetery, although spaces for new burials are limited. The Friends of Highgate Cemetery Trust, a charitable organization, manages the site and offers guided tours to visitors. These tours highlight the cemetery's history, notable interments, and conservation efforts, ensuring that its legacy endures for future generations.

Highgate Cemetery stands as a testament to Victorian attitudes toward death and remembrance, while also serving as a poignant reminder of the passage of time and the stories that endure beyond the grave.

Jumping forward to the year 1921, England. It was a time of transition and adjustment, as the nation grappled with the aftershocks of World War I, societal change, and economic challenges. The scars of the Great War were still deeply felt, and the country was striving to rebuild while adapting to new realities. This was a year of contrasts, hope and hardship, tradition and innovation.

The monarchy was a steadying force in the early 1920s. King George V reigned, embodying stability amidst a rapidly changing world. His role as a constitutional monarch saw him largely removed from direct political power, but his presence provided continuity and a sense of national unity. Parliament, led by Prime Minister David Lloyd George of the Liberal Party, faced the daunting task of steering the country through post-war recovery. The coalition government had to address economic issues, unemployment, and industrial unrest, as the economy struggled to transition from wartime to peacetime production.

Economically, England was grappling with the consequences of war debts and the decline of traditional industries like coal, steel, and textiles. The working class faced high unemployment rates, exacerbating the gap between rich and poor. In contrast, the wealthier classes maintained their comfortable lifestyles, often living in large homes staffed by servants, though this too was beginning to change as old aristocratic fortunes dwindled.

Energy in 1921 was largely coal-driven, with coal mining serving as a backbone of the economy. However, the industry was fraught with labor disputes. The Miners’ Strike of 1921 was a significant event, marked by miners protesting wage reductions and worsening conditions. While electricity was slowly expanding, it was not yet ubiquitous, and gas lighting remained common in homes and streets.

Transportation was evolving during this period. Railways remained the dominant means of long-distance travel, connecting cities and towns across the country. The growth of the motor car was notable, though still limited to the wealthier classes. Buses and trams provided affordable urban transit, while bicycles were a popular mode of transportation for the working class. Aviation was in its infancy, largely seen as a novelty.

The social atmosphere of 1921 reflected both lingering Victorian values and the beginnings of modernity. The war had disrupted traditional gender roles, and while many women returned to domestic roles, others pushed for greater independence and opportunities. The suffragette movement had achieved success with the Representation of the People Act 1918, but the quest for equality continued.

Fashion reflected the shifting societal norms. Women’s clothing became less restrictive, with shorter hemlines and looser fits symbolizing newfound freedoms. The flapper style was emerging, though it would peak later in the decade. For men, tailored suits remained the standard, but the post-war years saw more casual styles gaining acceptance.

Traditional foods in England in 1921 were hearty and simple, reflecting both the lingering effects of wartime rationing and the agricultural practices of the time. Meals often included meat, potatoes, bread, and seasonal vegetables, with puddings and pies as staples. Tea remained a national institution, enjoyed across all classes.

Entertainment was an essential escape from the struggles of daily life. The cinema was burgeoning in popularity, with silent films drawing audiences to picture houses. Live theatre, music halls, and radio broadcasts also entertained the masses. For the upper classes, balls, country pursuits, and exclusive clubs were popular pastimes.

Sanitation and public health had improved significantly since the Victorian era, but challenges remained. Urban areas faced overcrowding and inadequate housing, contributing to poor living conditions for many. The rich, in contrast, enjoyed modern plumbing and spacious homes, highlighting the stark disparity between classes.

The difference between the rich and poor was glaring in 1921. The wealthy lived in grand homes with access to education, healthcare, and leisure, while the working class and poor often lived in cramped, unsanitary conditions, relying on factory or manual labor to make ends meet. However, movements advocating for workers’ rights and social reforms were gaining traction, signaling the potential for change.

1921 was also the year of the census, a significant event that offered a detailed snapshot of life in post-war England. Conducted on June 19, it was the first census in the United Kingdom since 1911, delayed by a year due to the disruptions of World War I and the subsequent Spanish flu pandemic. This census was unique in several ways, reflecting the profound changes that had occurred in society during the intervening decade.

The 1921 Census aimed to capture detailed demographic and social information about the population. It recorded names, ages, marital status, and employment details for every individual. Importantly, it asked questions about education, religion, and occupation, providing insights into the nation's evolving economic and social landscape. For the first time, the census included information about employment status—whether a person was an employer, employee, or self-employed—acknowledging the changing nature of work and industry.

The aftermath of World War I was evident in the data. The war had resulted in significant population shifts, with a noticeable imbalance in the number of men and women due to the loss of life among soldiers. This had long-lasting effects on marriage rates, family structures, and societal roles. Many women who had entered the workforce during the war remained employed, contributing to a gradual shift in traditional gender roles, though this was not without controversy or resistance.

Housing conditions were another focus of the 1921 Census. England faced a housing shortage exacerbated by the war, and the census highlighted overcrowding in urban areas. This data would later inform government policies aimed at improving living conditions, including the construction of new homes under the "homes fit for heroes" initiative.

The census also revealed regional disparities in employment and living conditions. Industrial areas in the north and midlands were still recovering from the economic impacts of the war, while agricultural regions faced their own set of challenges. The census data provided a foundation for understanding these disparities and planning future interventions.

For genealogists and historians, the 1921 Census is a treasure trove of information, offering a window into the lives of ordinary people during a transformative period. It captures a nation in flux, grappling with the legacies of war and the uncertainties of a modernizing world. However, it also underscores enduring inequalities and challenges, such as class divides and economic hardship, that would continue to shape England's trajectory in the years to come.

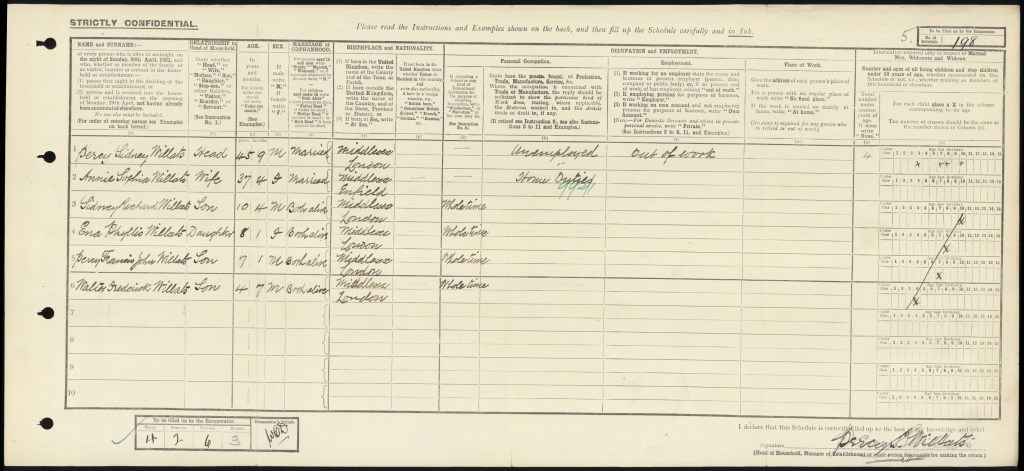

On Sunday, the 19th of June, 1921, the census paints a vivid picture of the Willats family and their life at Number 27, King's Road, Stoke Newington, London. Percy Sidney and his wife Sophia were at the heart of the household, along with their four children: Sidney Richard, Ena Phyllis, Percy Francis John, and Walter Frederick. Percy, at the time, was unemployed, undoubtedly a source of concern for the family, while Sophia managed the home with care and diligence.

The children, Sidney, Ena, Percy, and Walter, were all full-time students, their days likely filled with lessons, play, and the occasional chore. Together, the family of six lived in three rooms at Number 27. It's easy to imagine the cramped but lively space, filled with the chatter of siblings and the quiet resolve of parents working to provide for their future.

The years that followed brought Percy and her family profound sorrow, marking a period of deep and lasting heartbreak. The first of these tragedies unfolded on Monday, the 27th of November 1922, when Percy’s beloved brother, Henry Richard Willats, passed away at the age of 67. Once a proud Director of Limited Companies, Henry’s life came to an end at 23 Barnmead Road, Beckenham, in Bromley, Kent.

Henry’s passing was not sudden but the culmination of years of health struggles. He had endured chronic nephritis for a decade and, in his final six months, faced the ravages of cardiac failure. Despite the inevitability of his condition, the loss was no less devastating.

Their brother, Walter James Willats, demonstrated love and solidarity by being by Henry’s side in those final moments. Walter, of 132 Lansdowne Road, not only attended his passing but also took on the somber duty of registering Henry’s death on the very same day, ensuring his brother’s life was acknowledged and recorded with care.

This loss, heavy with grief, was the first of several trials for Percy and her family, marking the beginning of a challenging chapter filled with sorrow and resilience.

The Willats family laid, Henry Richard Willats to rest, on Friday the 1st of December 1922, at Abney Park Cemetery, 215 Stoke Newington High Street, Stoke Newington, London, England, N16 0LH. His was buried in a family grave and was buried with Baby Thornton, Florence Jose Western nee Willats, Harry Ashley Willats, William Western Thornton, and Amelia Willats.

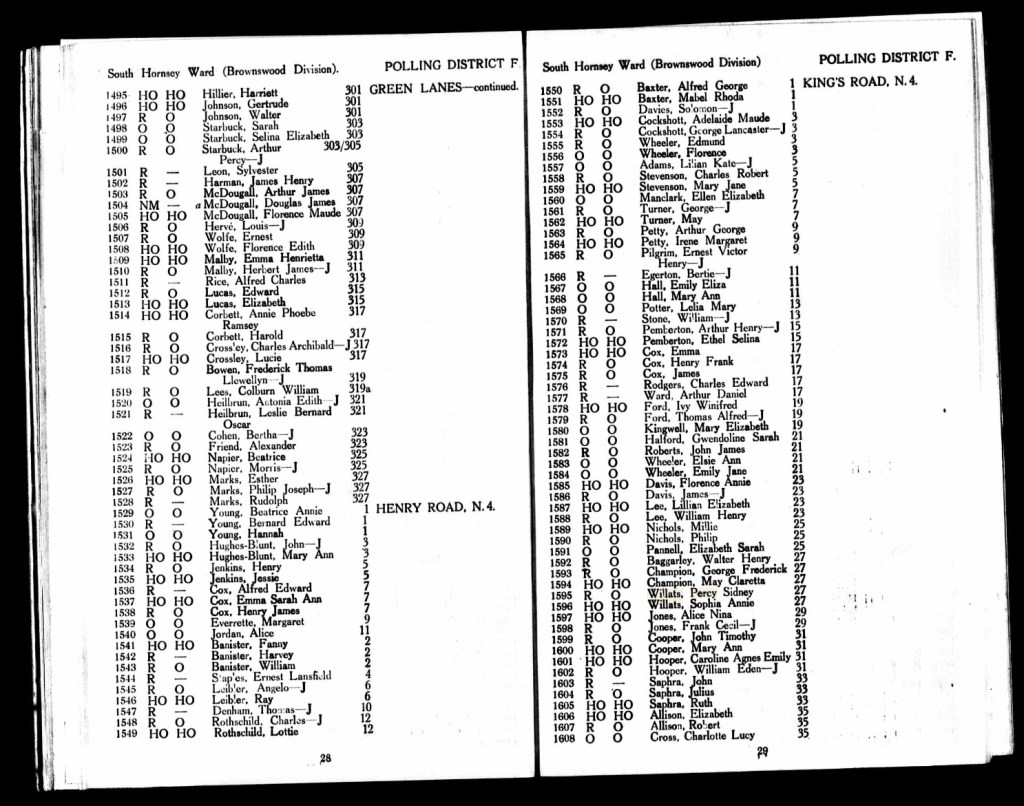

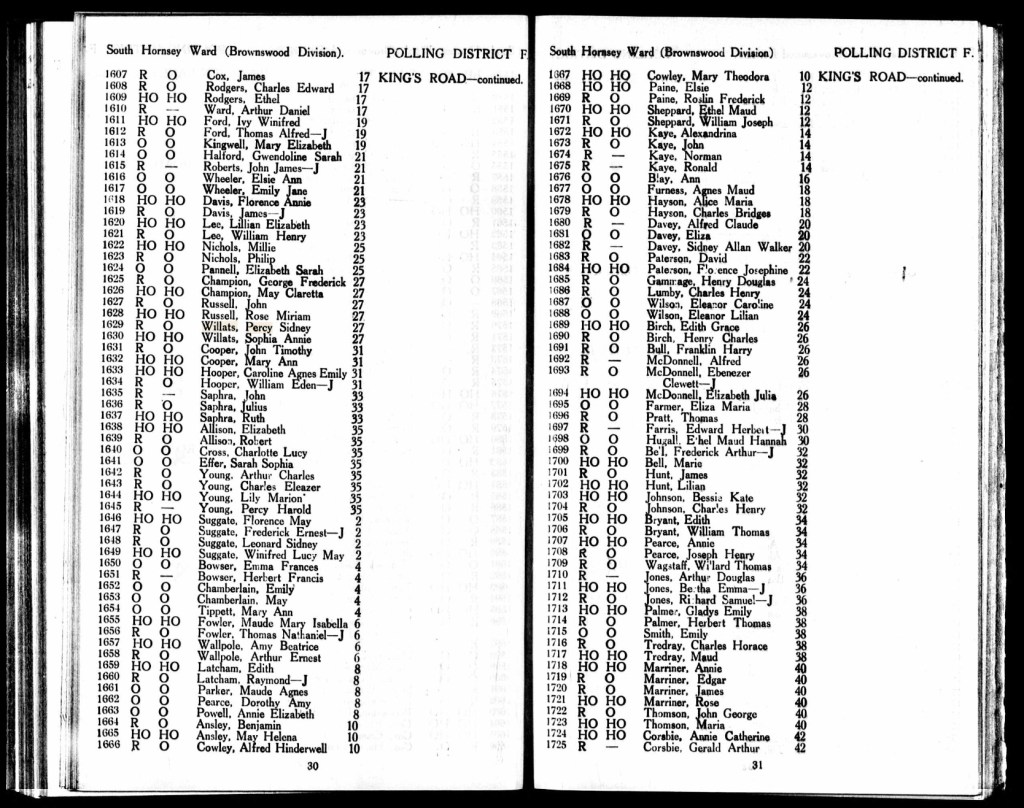

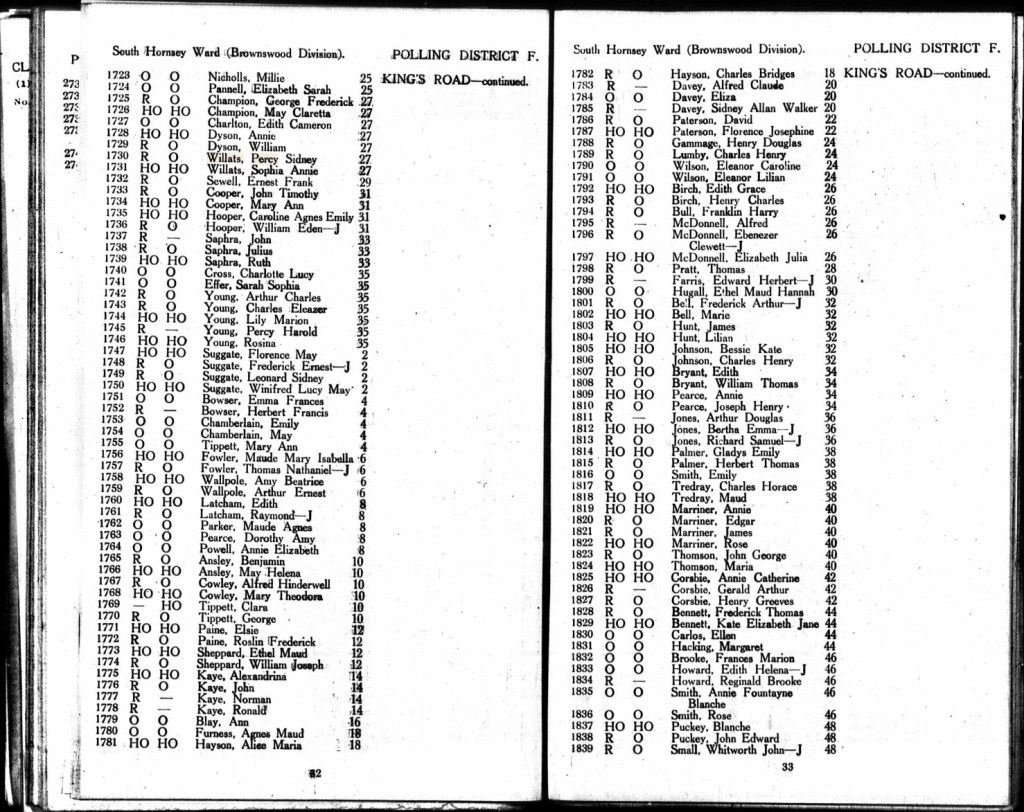

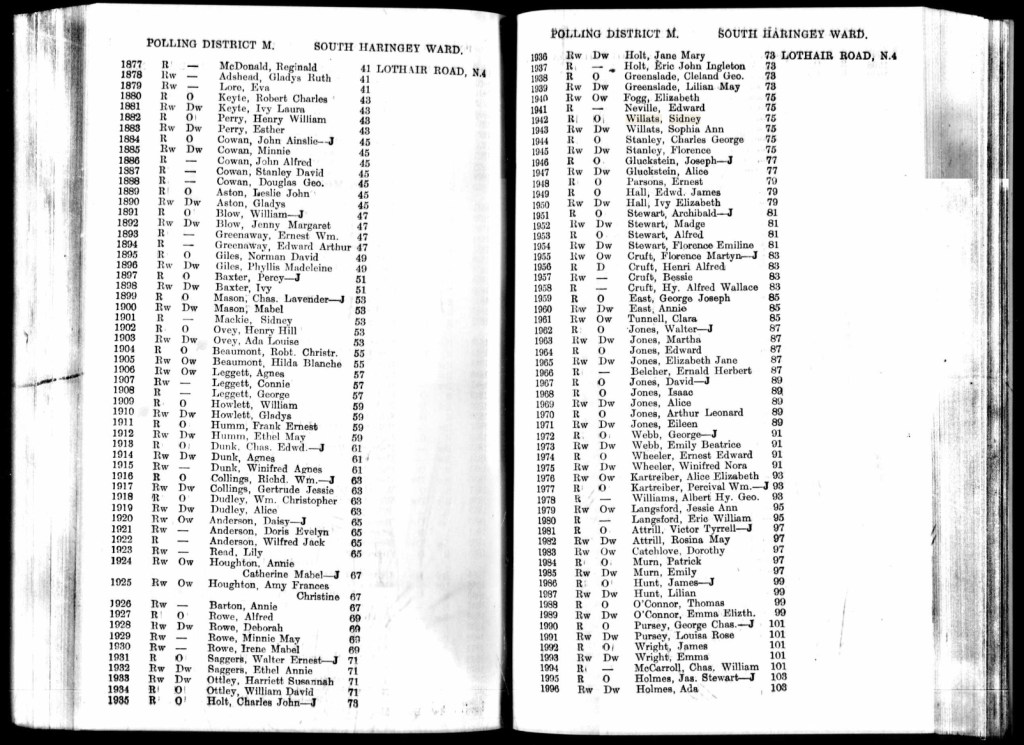

The 1922 London Electoral Registers shows Percy, and Sophia, his sister May Champion and brother In-Law George Frederick Champion, were residing at Number 27, Kings Road, Hornsley, Islington, Middlesex, England, in 1922. Walter Henry Baggarley was also residing there.

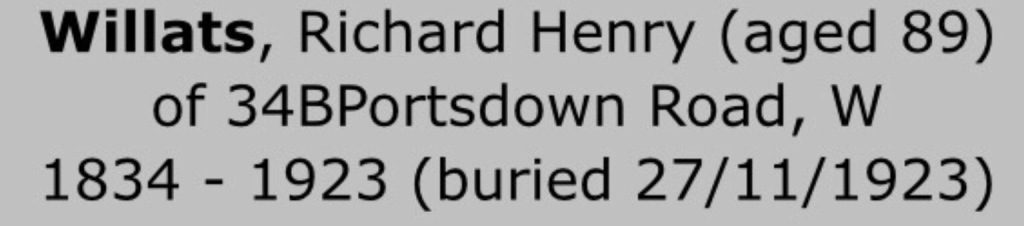

Heartbreak struck Percy once more with the loss of his father, Richard Henry Willats, who passed away at the age of 89 on Thursday, the 22nd of November 1923. Richard’s final days were spent at 34B Portsdown Road, Paddington, London, where he succumbed to bronchitis and the frailties of advanced age, a poignant reminder of life’s inevitabilities.

Percy, ever a devoted son, was present during this solemn time, bearing witness to the end of a long and full life. On Saturday, the 24th of November, Percy undertook the painful duty of registering his father’s death, ensuring that Richard’s legacy was respectfully recorded. In doing so, he honored his father’s lifetime of work as a retired auctioneer and surveyor, roles that spoke to Richard’s dedication and contribution to his community.

Percy, listing his own address as 27 Kings Road, Finsbury Park, carried the weight of this loss, no doubt reflecting on the memories of his father and the bond they shared. This moment marked another profound chapter of grief for Percy and his family, as they faced the loss of a beloved patriarch whose presence had been a cornerstone of their lives.

Senility, also referred to as senile dementia or simply dementia, is a condition characterized by a progressive decline in cognitive function beyond what is considered a normal part of aging. It is not a specific disease but rather a broad term used to describe a range of symptoms associated with cognitive impairment severe enough to interfere with daily activities and independenc

The most common cause of senility is Alzheimer's disease, a neurodegenerative disorder that leads to the accumulation of plaques (beta-amyloid protein) and tangles (tau protein) in the brain, disrupting communication between neurons and causing their eventual death. Other causes of senility include vascular dementia (caused by reduced blood flow to the brain due to stroke or small vessel disease), Lewy body dementia (involving abnormal protein deposits in the brain), frontotemporal dementia (involving degeneration of the frontal and temporal lobes of the brain), and mixed dementia (a combination of Alzheimer's disease and vascular dementia).

Symptoms of senility typically begin gradually and worsen over time. They may include memory loss (especially recent memories), confusion, difficulty with language and communication, poor judgment, changes in mood or behavior, and problems with reasoning and decision-making. As the condition progresses, individuals may require assistance with daily tasks such as dressing, bathing, and eating.

Diagnosis of senility involves a thorough medical history, physical examination, cognitive assessments (such as the Mini-Mental State Examination), blood tests, brain imaging (such as MRI or CT scan), and sometimes neuropsychological testing. It is important to distinguish senility from reversible causes of cognitive impairment, such as medication side effects, vitamin deficiencies, thyroid problems, or infections.

Management of senility focuses on improving quality of life, managing symptoms, and providing support to both the individual affected and their caregivers. While there is currently no cure for most types of senility, medications may be prescribed to temporarily improve cognitive function or manage behavioral symptoms. Non-pharmacological approaches, such as cognitive stimulation therapy, occupational therapy, and caregiver support programs, are also integral to management.

Ultimately, senility poses significant challenges to individuals, families, and society as a whole due to its progressive nature and the need for long-term care. Research into treatments and potential preventive measures continues to advance, aiming to mitigate the impact of this devastating condition on affected individuals and their loved ones.

Portsdown Road, located in Paddington, London, is a residential street that embodies the historical and architectural charm typical of this part of the city. Paddington itself is a district known for its rich history, central location, and significant landmarks, including Paddington Station, which has been a crucial transport hub since its opening in 1854.

Portsdown Road is situated in a part of Paddington that showcases the area's Victorian heritage. The street is lined with elegant terraced houses that date back to the late 19th and early 20th centuries. These homes often feature the distinctive architectural details of the period, such as stucco façades, ornate cornices, and large sash windows. Many of the properties have been carefully preserved and updated, blending historical character with modern amenities.

The history of Portsdown Road is closely linked to the broader development of Paddington. In the 19th century, Paddington experienced significant growth due to its strategic location and the expansion of the railway. The opening of Paddington Station by the Great Western Railway spurred the development of residential areas to accommodate the growing population of London. This period saw the construction of many of the elegant terraces and crescents that define the architectural landscape of the district today.

Paddington itself has a rich and varied history. Originally a medieval parish, it became a key suburban area in the 19th century, known for its grand residential buildings and its proximity to the West End. The district also has a notable literary connection, being famously associated with the fictional character Paddington Bear, created by Michael Bond. The bear, named after Paddington Station, has become an enduring symbol of the area.

In modern times, Portsdown Road benefits from its location in one of London's most dynamic and well-connected districts. Paddington has undergone significant regeneration in recent years, particularly around the Paddington Basin and the Grand Union Canal, transforming it into a vibrant area with a mix of residential, commercial, and recreational spaces. The canal, which dates back to the early 19th century, adds a picturesque element to the district and offers a range of leisure activities, including boating and waterside dining.

Transport links from Portsdown Road are excellent, with Paddington Station providing access to multiple Underground lines, National Rail services, and the Heathrow Express, making it a gateway to both the rest of London and international travel. The recent addition of the Elizabeth Line (Crossrail) has further enhanced connectivity, reducing travel times across the city.

The area around Portsdown Road is also rich in amenities and cultural attractions. Hyde Park, one of London’s largest and most famous parks, is within walking distance, offering vast green spaces, recreational facilities, and cultural events. Nearby, the vibrant districts of Notting Hill and Bayswater provide an array of shops, restaurants, and entertainment options.

On Tuesday, the 27th of November 1923, the remaining Willats family came together in a solemn and heartfelt gathering to lay their beloved father, Richard Henry Willats, to rest. His final resting place was at Abney Park Cemetery, a peaceful sanctuary in Stoke Newington, London, where love and remembrance intertwined with the quiet of the grounds.

Richard was reunited in eternal rest with those who had gone before him, his cherished wife, Eliza Willats (née Cameron), their sons, Francis Paul Willats and Percy Sidney Willats, and his stepson and nephew, William George Willats, whose connection and memory bridged generations. In grave number 092431 in Plot D06, Richard now lies alongside the family he had built and nurtured, bound together not just by lineage but by enduring love and shared history.

For the family who remained, this day was a poignant reminder of the ties that hold us even in the face of loss. As they said their goodbyes, they honored a man whose life had shaped their own and whose legacy would continue to echo through the generations. This resting place became a sacred point of connection, a symbol of both sorrow and the unbroken thread of family.

The London Electoral Registers shows Percy, and Sophia, his sister May Champion and brother In-Law George Frederick Champion, were residing at Number 27, Kings Road, Hornsley, Islington, Middlesex, England, in 1923. John and Rose Russell were also residing at Number 27, Kings Road.

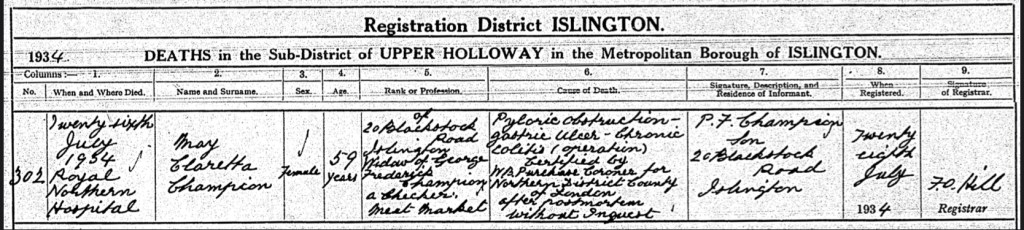

Heartbreak struck the Willats family once again less than six months later when Percy’s dear sister, Charlotte Ellen Crosbie, passed away. Charlotte, 64 years old and a widow of medical student Pierce William Crosbie, left this world on Saturday, the 5th of April 1924, in the familiar comfort of her home at 34 Portsdown Road, Paddington, London.

Charlotte’s passing came after a struggle with cardiac disease (mitral) and hemiplegia, conditions that had likely caused her great suffering in her final years. Her loss must have weighed heavily on her family, who had already endured so much grief.

In an act of love and duty, their sister Edith Cameron Charlton (née Willats), of 27 Kings Road, Finsbury Park, was by Charlotte’s side and took on the sorrowful responsibility of registering her sister’s death on Monday, the 7th of April 1924, in Paddington. Edith’s presence during Charlotte’s final days is a testament to the deep bonds of sibling love and support that endured through all the trials the family faced.

Charlotte’s death marked yet another painful chapter for Percy and his family, as they continued to navigate a period of unrelenting loss. Her absence would have left an irreplaceable void, though her memory and the love she shared with her family remained a source of quiet strength.

Charlottes life was absolutely fascinating. You can read about it, here, and here.

Mitral valve disease refers to conditions affecting the mitral valve, one of the four valves in the heart responsible for ensuring blood flows in the correct direction. The mitral valve is located between the left atrium and left ventricle and helps regulate blood flow from the lungs to the rest of the body. Mitral valve disease can manifest in two main forms: mitral valve stenosis and mitral valve regurgitation.

Mitral valve stenosis occurs when the valve becomes narrowed and restricts blood flow from the left atrium to the left ventricle. This narrowing is often due to scarring and thickening of the valve leaflets, commonly caused by rheumatic fever, an inflammatory condition resulting from untreated streptococcal infections. Historically, rheumatic fever was a leading cause of mitral valve stenosis, particularly in children and young adults in developing countries. However, in developed countries, rheumatic fever has become less common due to improved healthcare and antibiotic treatments. Mitral valve stenosis can also result from congenital heart defects or calcium deposits on the valve.

Mitral valve regurgitation, on the other hand, occurs when the valve does not close properly, allowing blood to leak backward from the left ventricle into the left atrium during contraction. This leakage can lead to symptoms such as fatigue, shortness of breath, and eventually heart failure if left untreated. Causes of mitral valve regurgitation include degenerative changes in the valve (often associated with aging), congenital defects, infections, or damage from a heart attack.

Diagnosis of mitral valve disease involves a combination of clinical evaluation, imaging tests such as echocardiography (ultrasound of the heart), and sometimes cardiac catheterization to assess the severity and impact on heart function. Treatment depends on the severity of the condition and may include medications to manage symptoms (such as diuretics or blood thinners), surgical repair or replacement of the valve, or less invasive procedures like percutaneous mitral valve repair.

Hemiplegia, on the other hand, refers to paralysis affecting one side of the body, typically caused by damage to the motor areas of the brain or spinal cord. It is most commonly associated with strokes (cerebrovascular accidents) that result from a blockage or rupture of blood vessels supplying the brain. Historically, hemiplegia was often attributed to strokes caused by conditions like hypertension, atherosclerosis, or cardiac emboli (clots from the heart).

The history of hemiplegia treatment has evolved significantly over time, reflecting advancements in understanding the underlying causes and development of rehabilitation techniques. In ancient times, hemiplegia was often considered incurable or associated with supernatural causes. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, the introduction of medical imaging techniques like CT scans and MRI revolutionized the diagnosis of strokes and other neurological conditions causing hemiplegia.

Modern treatment of hemiplegia includes acute interventions such as thrombolytic therapy to dissolve blood clots and surgical procedures like carotid endarterectomy to remove plaque from narrowed arteries. Rehabilitation plays a crucial role in recovery, focusing on physical therapy, occupational therapy, and speech therapy to help individuals regain function and independence.

Charlotte was laid to rest at Abney Park Cemetery, 215 Stoke Newington High Street, Stoke Newington, London, England, N16 0LH, on Wednesday the 9th of April 1918, in grave 127434 possibly renumbered 17434, (Grave Reference - Sec. I09, Index 7S08.) with Baby Crosbie, her niece Amina Eliza Kathleen Reichert nee Charlton, her cousin Mabel Cameron Woollet Willats, and Eliza Smith (Charlotte's companion).

The 1924 London Electoral Registers shows Percy, and Sophia, his sisters Edith and May Champion and brother In-Law George Frederick Champion, were residing at Number 27, Kings Road, Hornsley, Islington, Middlesex, England, in 1924. William and Annie Dyson were Also residing at Number 27, Kings Road, Hornsley, Islington.

From the 1925 London City Directory, we know Percy and his brother In-law George Champion, were residing at Number 27, Kings Road, Finsbury Park, Stoke Newington, Middlesex, England, in 1925

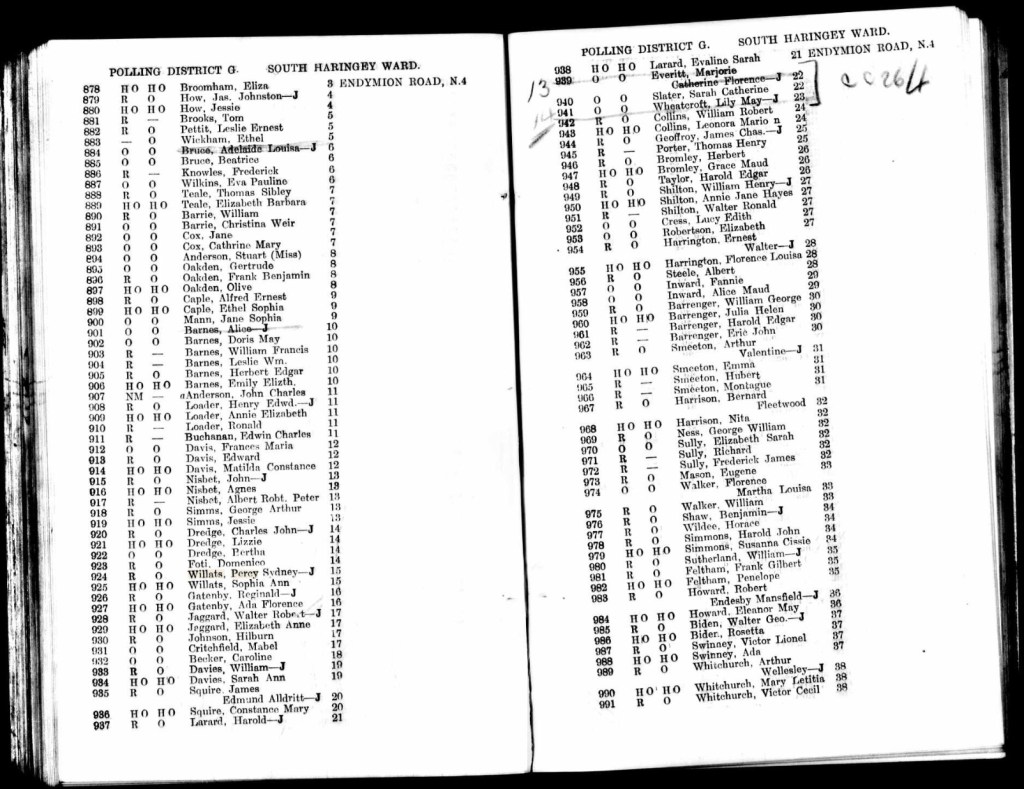

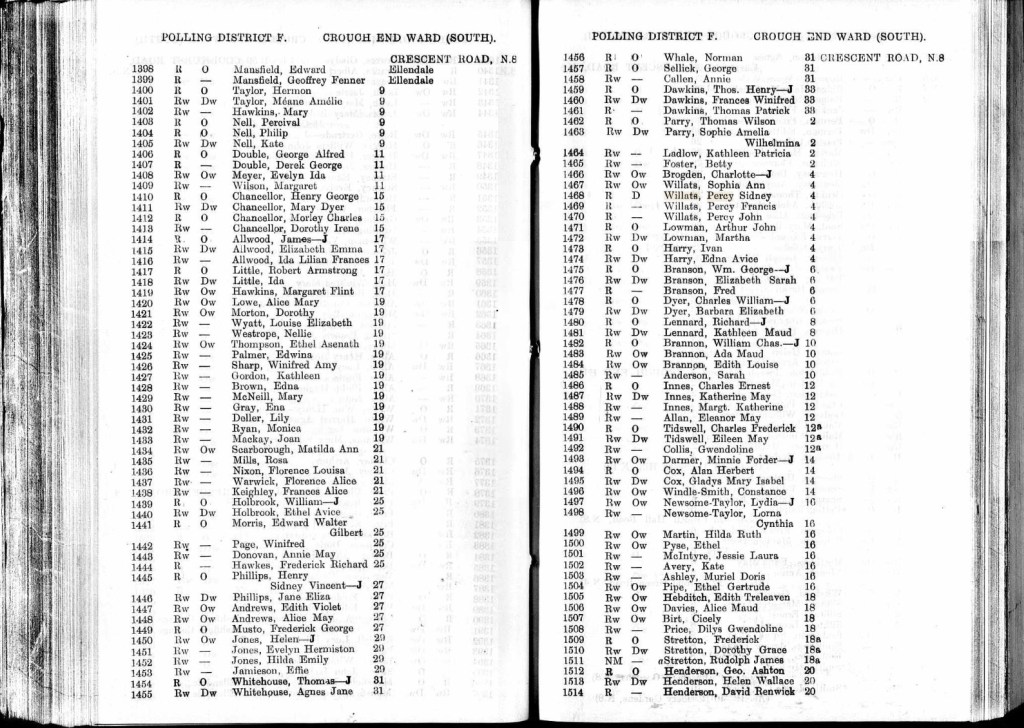

The London Electoral Registers shows Percy, and Sophia, were residing at Number 15, Endymion Road, Harringay, Hornsey, Middlesex, England, in 1926.

Endymion Road is a significant thoroughfare in the Harringay district of Hornsey, North London, with a rich history that reflects the area's transformation from open fields to a bustling suburban community.

In the mid-19th century, the land now occupied by Endymion Road was largely open fields and parkland, part of the grounds of the former Harringay House. The area was traversed by Green Lanes, an ancient route connecting various parts of London. The construction of Finsbury Park in 1869, designed by Alexander McKenzie, marked a significant change in the landscape, as the park covered the old Hornsey Wood, a popular recreation ground since the 18th century. Endymion Road was laid out across the north side of the park around 1875, facilitating access to the newly developed areas.

The development of the Harringay district accelerated in the late 19th century. In 1881, the British Land Company purchased a substantial portion of the Harringay Park Estate and began subdividing it into plots for residential development. Endymion Road was among the first to be laid out, reflecting the area's rapid transformation into a residential suburb.

The name "Endymion" is believed to be inspired by the title of a novel by Benjamin Disraeli, the 19th-century British Prime Minister and writer. This literary connection is part of a broader pattern in the naming of streets in the Harringay area, where many roads are named after literary figures and works.

Over the years, Endymion Road has evolved alongside the Harringay district, reflecting the broader changes in London's urban development. Today, it stands as a testament to the area's rich history, from its origins as part of the grounds of Harringay House to its current status as a vibrant residential street in North London.

The weight of loss was becoming almost unbearable for Percy and his family, yet their lives were once again shattered by grief when their beloved 14-year-old daughter, Ena Phyllis Willats, passed away on Monday, the 27th of February, 1928. Ena’s death, caused by Malignant Endocarditis and Sub-acute Rheumatism, left a profound emptiness in the hearts of those who loved her. In her final moments, she was surrounded by the compassionate care of those at North Middlesex Hospital in Edmonton, London, who did all they could to ease her suffering. Tragically, no postmortem was performed, leaving the true complexity of her illness a mystery.

Ena's devoted mother, Sophia Ann Willats (née High), registered her daughter’s death on Tuesday, the 28th of February, 1928. In her sorrow, Sophia remembered Ena with love, noting her role as a Retail Stationery Shop Assistant and her residence at 144 Stroud Green Road in Hornsey. She also shared that Ena was the cherished daughter of Sidney Percy Willats, an Auctioneer’s Clerk, a reminder of the deep family ties that had shaped Ena's life.

The hospital where Ena passed, North Middlesex Hospital, holds its own rich history within the community. Established in 1910 as the infirmary for Langhedge Field Workhouse, it later became Edmonton Military Hospital during the First World War before returning to civilian care in 1920. Over the years, the hospital grew and adapted, enduring the trials of war, transformation, and resilience, much like the lives of those, like Ena, who passed through its doors.

Though her time in this world was tragically brief, I am sure, Ena’s life was a bright and loving presence. Her memory, filled with the promise of youth and the warmth of her family’s love, lives on in the hearts of all who knew her, a lasting testament to the light she brought into their lives.

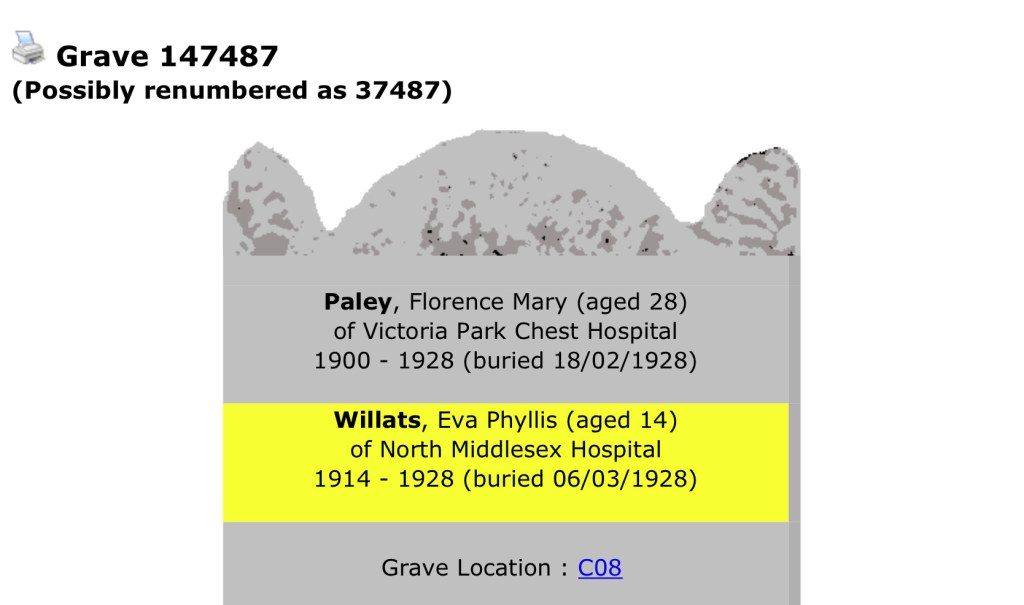

With deep sorrow and loving remembrance, Percy and Sophia laid their cherished daughter, Eva Phyllis Willats, to rest on Tuesday, the 6th of March, 1928, at Abney Park Cemetery in Stoke Newington, Hackney, Middlesex, England. Eva, though her time with them was far too short, will always be remembered with a heart full of love and tenderness. Her resting place, in Grave 147487 (possibly renumbered as 37487), stands as a quiet testament to the bond of love that continues to endure, even in the face of heartache.

In a moment of shared sorrow, Florence Mary Paley, aged 28, of Victoria Park Chest Hospital, was also laid to rest in the same grave on Saturday, the 18th of February, 1928. Florence, too, I’m sure was deeply loved, and her memory is now intertwined with Eva’s, forever marking the space they share in the peaceful embrace of Abney Park Cemetery. Both souls, though departed from this world, continue to be remembered with immense love, their spirits bound together in a place of eternal peace.

The relentless grip of sorrow had not yet loosened its hold on the Willats family, and a few years later, Percy faced the loss of his brother, Walter James Willats. Walter, a 64-year-old stockbroker, passed away on Friday, the 29th of March 1929, at his residence at 163 Camden Road, St Pancras, London.

Walter’s life was cut short by myocarditis, bronchitis, and cardiac failure, illnesses that no doubt caused him considerable suffering. His passing marked another devastating blow for a family already familiar with profound loss.

In his final moments and thereafter, Walter was not alone. His nephew, P. Champion, also residing at 163 Camden Road, was present and took on the solemn task of registering Walter’s death on Tuesday, the 2nd of April 1929, in St Pancras. This act of love and care ensured that Walter’s life and legacy were respectfully recorded, a gesture that spoke to the enduring bonds of family even in times of grief.

Though Walter’s final resting place remains unknown for now, his memory endures, woven into the fabric of a family that had weathered so much together. For Percy and the Willats family, Walter’s loss was yet another poignant reminder of the fragility of life and the resilience of the heart in the face of unrelenting sorrow.

Myocarditis and cardiac failure are both significant cardiovascular conditions that can have profound impacts on heart function and overall health.

Myocarditis is an inflammatory condition affecting the myocardium, the muscular tissue of the heart. It can result from various causes, including viral infections (such as Coxsackievirus, adenovirus, or SARS-CoV-2), bacterial or fungal infections, autoimmune diseases, certain medications, or toxins. The inflammation in myocarditis can weaken the heart muscle, impairing its ability to pump blood effectively. This can lead to symptoms such as chest pain, shortness of breath, fatigue, and palpitations. In severe cases, myocarditis can cause heart failure, arrhythmias (abnormal heart rhythms), or sudden cardiac death.

The history of myocarditis dates back centuries but has significantly evolved with advances in medical understanding and diagnostic techniques. Historically, myocarditis was often difficult to diagnose and understand due to limited medical knowledge and diagnostic tools. Early descriptions of myocarditis focused on its association with infectious diseases and the recognition of cardiac inflammation as a potential cause of heart dysfunction.

In the 20th century, the discovery and development of diagnostic tools such as electrocardiography (ECG), echocardiography (ultrasound of the heart), and cardiac MRI revolutionized the diagnosis and management of myocarditis. These technologies enabled healthcare providers to visualize heart function and identify signs of inflammation or damage to the myocardium more accurately.

Treatment of myocarditis depends on the underlying cause and severity of symptoms. Mild cases may resolve on their own or with supportive care, while severe cases may require medications to reduce inflammation (such as corticosteroids or immunosuppressants), manage symptoms, and support heart function. In some cases, advanced heart failure treatments such as mechanical circulatory support devices or heart transplantation may be necessary.

Cardiac failure, commonly known as heart failure, refers to a chronic condition where the heart is unable to pump blood effectively to meet the body's needs. This can occur due to various underlying conditions that weaken or damage the heart muscle, including coronary artery disease (leading to myocardial infarction or heart attacks), hypertension, cardiomyopathy (diseases of the heart muscle), valve disorders, or myocarditis. Over time, heart failure can lead to symptoms such as shortness of breath, fatigue, swelling (edema), and difficulty with exercise.

Historically, heart failure was often viewed as a terminal condition with limited treatment options. However, advancements in medical therapies, diagnostic techniques, and surgical interventions have transformed the management of heart failure over the past century. The development of medications such as ACE inhibitors, beta-blockers, diuretics, and aldosterone antagonists has significantly improved outcomes by reducing symptoms, slowing disease progression, and prolonging survival.

Surgical interventions such as coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), valve repair or replacement, and implantation of devices like pacemakers or implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICDs) have also played crucial roles in managing heart failure. More recently, innovative therapies such as cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) and transcatheter valve interventions have further expanded treatment options for specific types of heart failure.

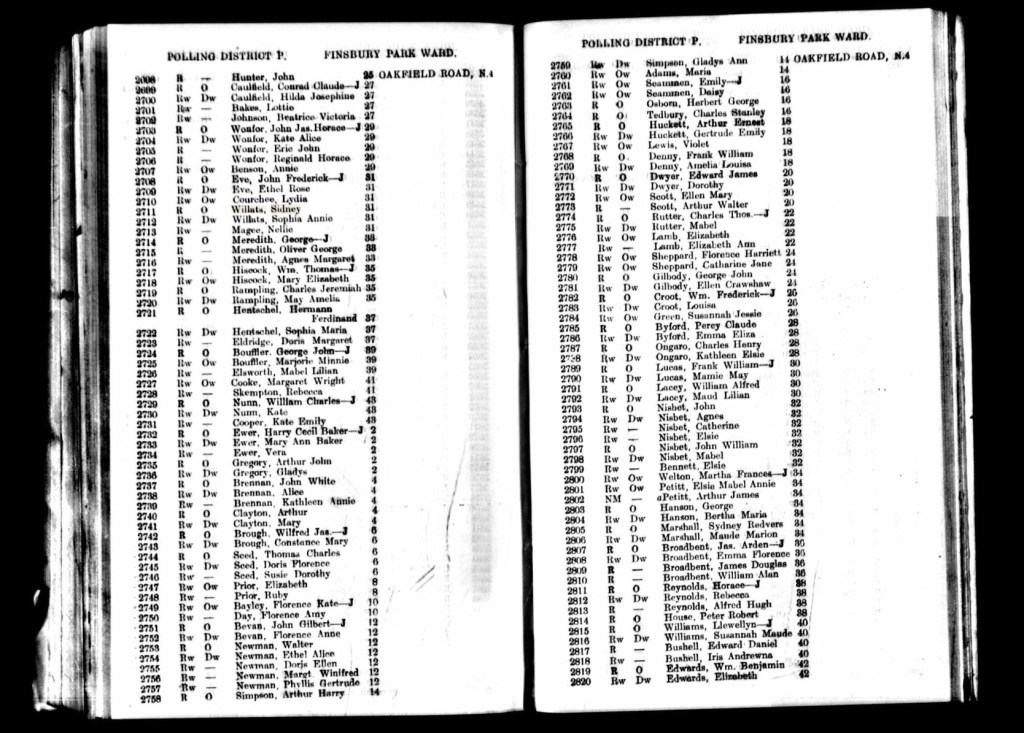

The 1931 London, England, Electoral Register shows Sidney and Sophia, were residing at Number 31 Oakfield Road, Hornsey, Middlesex, England, in 1931. John Frederick-J and Ethel Rose Eve, Lydia Courchee and Nellie McGee were also residing there.

Oakfield Road is a residential street located in the Hornsey area of North London, within the borough of Haringey. Historically, Hornsey was part of Middlesex, a historic county that was later absorbed into Greater London during the 20th century. The area itself has a rich history, evolving from rural farmland to a more densely populated urban setting.

In the 19th century, Hornsey was predominantly rural, with small villages and farms scattered around. However, as London expanded during the Victorian era, the region underwent significant development. Hornsey became an attractive suburban area for middle-class families looking to move away from the congested city center. This was a period when many large houses and semi-detached properties were built in the area, often surrounded by green spaces, which would have characterized Oakfield Road at the time.

The late 19th and early 20th centuries saw Hornsey’s transformation into a more residential community, supported by the development of better transport links, including the expansion of the railway system. The opening of the Hornsey railway station in the 1850s provided a vital connection to central London, making the area more accessible and further encouraging suburban development.

Oakfield Road likely followed this pattern of growth, with houses being built primarily in the late 19th or early 20th centuries. During this time, the street would have been part of a wider expansion of residential areas that were largely middle-class and family-oriented. The area surrounding Oakfield Road, including the broader Hornsey district, was often characterized by tree-lined streets and quiet suburban living.

Through the 20th century, Hornsey and surrounding areas continued to develop, and Oakfield Road became a typical residential street, with a mix of terraced houses, semi-detached homes, and larger detached properties. The area’s proximity to both central London and green spaces such as Alexandra Park made it a desirable location for those seeking to balance urban life with access to nature.

Today, Oakfield Road retains much of its historic character, with many properties still showcasing the original architectural styles from the late Victorian and early Edwardian periods. The road's development over the years mirrors the overall changes in Hornsey, from rural farmland to a thriving suburban district. With modern amenities and good transport links, Oakfield Road remains a sought-after location, offering both a sense of historical charm and practical convenience.

The street itself, now primarily residential, is located within a community that is part of a larger regeneration effort in Haringey. This means Oakfield Road has seen both preservation of its historical character and some modern development. Its history reflects the broader trends in North London’s growth, from its rural origins to its current status as a desirable urban residential area within Greater London.

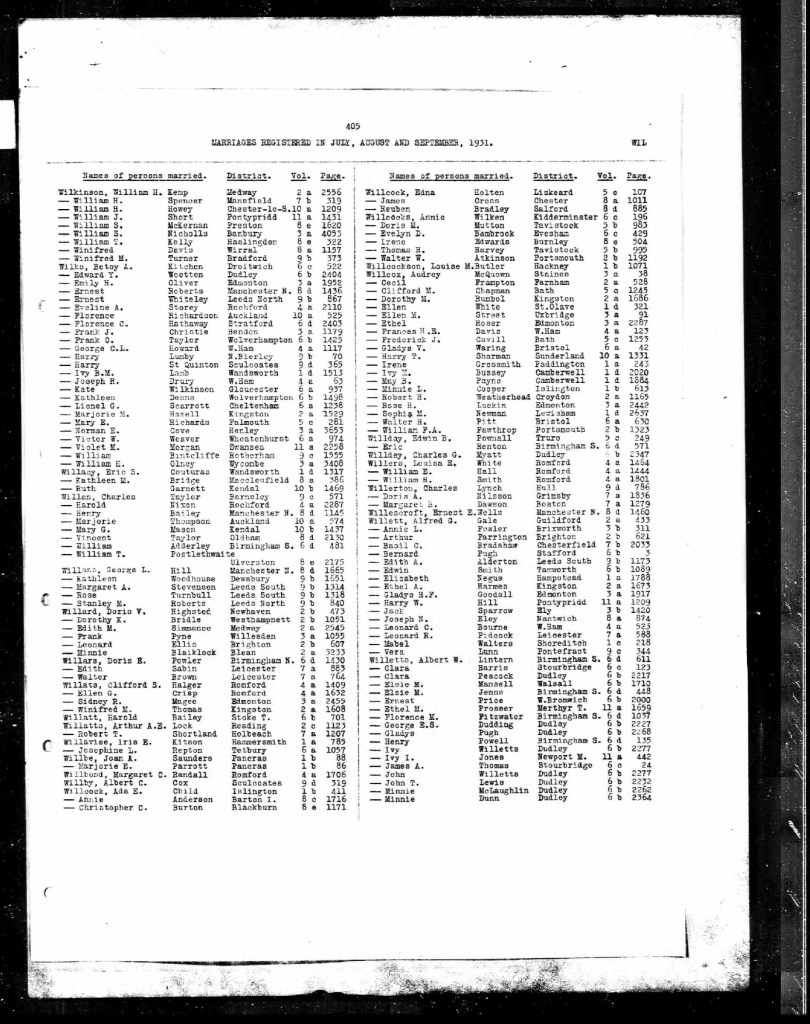

Percy and Sophia’s son, Sidney Richard Willats, married Ellen M Magee, in the July quarter of 1931 in the district of Edmonton, Essex, England.

From the 1932 Electoral Register, we know Percy and Sophia had moved properties and were now residing at, Number 45, Tollington Park, Islington, Middlesex, England, in 1932.

Tollington Park is a road located in the northern part of Islington, London, which was historically part of the county of Middlesex. The area surrounding Tollington Park has a long and rich history, evolving from rural farmland to an urbanized part of Greater London. Islington itself has been a significant area in the development of London, and Tollington Park’s history reflects this broader transformation.

In the medieval period, Islington was a small village located to the north of London, surrounded by open fields. It was primarily an agricultural area, with farmland and a few scattered houses. The name "Tollington" itself is believed to have derived from the Old English term "Tollington," meaning a settlement near a toll gate, suggesting that there may have been a toll on a major route nearby, possibly related to the trade that passed through the area.

By the 17th century, Islington began to grow as the area became more integrated into the expanding urban landscape of London. The construction of roads and infrastructure contributed to the area’s development, and Islington started to become a popular place for wealthy Londoners who wished to escape the crowded city center. This trend continued into the 18th and early 19th centuries, with grand houses and estates being built, particularly along roads like Upper Street. During this period, Tollington Park would have been part of the larger rural landscape but was gradually becoming more urbanized as demand for housing increased.

The major transformation of the area occurred during the Victorian era, particularly in the mid-19th century, when large-scale urban development took place across Islington. The construction of the railways in the 1850s and the improvement of transport links to central London made it easier for people to commute from suburban areas like Islington. This led to a building boom in areas such as Tollington Park. Victorian housing, typically terraced houses and semi-detached villas, were built along the street. These homes were designed for middle-class families seeking a suburban lifestyle while still being within reach of the amenities and employment opportunities in central London.

As the 20th century progressed, Islington underwent further changes, and Tollington Park evolved into a primarily residential area. During the post-war period, Islington, like much of London, faced challenges such as bomb damage during World War II and urban decay in some areas. However, Tollington Park retained much of its Victorian charm, with many of the original houses preserved. The area also saw significant social and cultural changes, with the rise of a more diverse population and changes in the housing market.

In recent decades, Islington has become one of the most desirable areas in London due to its proximity to central London, its vibrant cultural scene, and its mix of historic and modern architecture. Tollington Park, as part of this broader Islington neighborhood, has benefited from the gentrification of the area. Many of the Victorian homes along Tollington Park have been renovated or restored, and the street has seen an influx of young professionals, families, and creatives who are drawn to its blend of history, accessibility, and community atmosphere.

Today, Tollington Park remains a quiet, leafy street with a strong sense of its historical character. The surrounding area, including the nearby Finsbury Park, provides green space, while the road is well-connected to central London via public transport. The history of Tollington Park reflects the broader trends in the development of Islington: from its rural roots to its status as an urban area within Greater London, with a rich architectural heritage that continues to shape its identity.

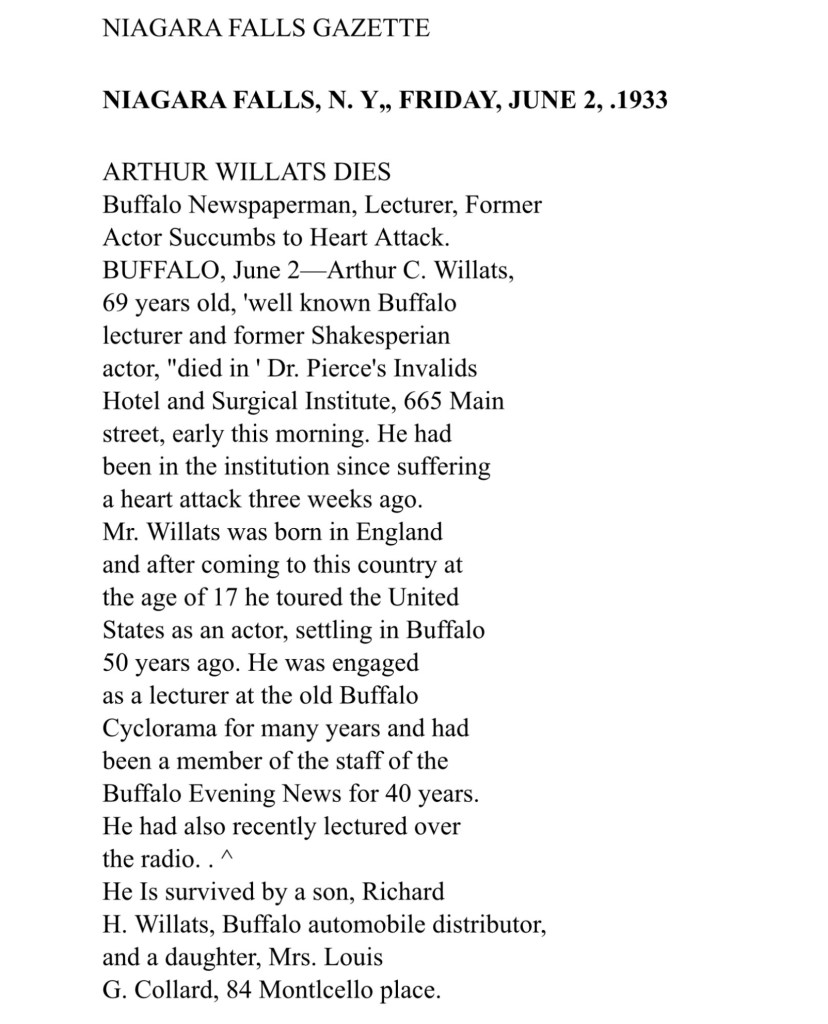

Heartbreakingly, Percy’s beloved brother, Arthur Charles Willats, passed away on Friday, the 2nd of June 1933, at the age of 69. Arthur, a distinguished Buffalo lecturer and former Shakespearean actor, died from a heart attack at Dr. Pierce’s Invalids Hotel and Surgical Institute, located at 665 Main Street in Buffalo, Erie, New York.

Arthur’s death was not only a deep loss for his family but also for the community that had known him for so many years. His passing was announced in the Niagara Falls Gazette on the same day, Friday, the 2nd of June 1933, with a heartfelt tribute to his life and contributions. The article read:

"ARTHUR WILLATS DIES – Buffalo Newspaperman, Lecturer, Former Actor Succumbs to Heart Attack."

The article continued, detailing his life: "BUFFALO, June 2 – Arthur C. Willats, 69 years old, well-known Buffalo lecturer and former Shakespearean actor, died in Dr. Pierce’s Invalids Hotel and Surgical Institute, 665 Main Street, early this morning. He had been in the institution since suffering a heart attack three weeks ago. Mr. Willats was born in England and, after coming to this country at the age of 17, he toured the United States as an actor, settling in Buffalo 50 years ago. He was engaged as a lecturer at the old Buffalo Cyclorama for many years and had been a member of the staff of the Buffalo Evening News for 40 years. He had also recently lectured over the radio. He is survived by a son, Richard H. Willats, Buffalo automobile distributor, and a daughter, Mrs. Louis G. Collard, 84 Monticello Place."

Arthur’s life was rich with experiences, from his early years in England to his successful career in the United States, where he made a lasting impact as both a performer and lecturer. His passing marked the end of an era for those who had known and admired him. For Percy and his family, the loss of Arthur was a deeply personal and poignant chapter of sorrow, but his memory, along with his significant contributions, would continue to live on in the hearts of those who loved him.

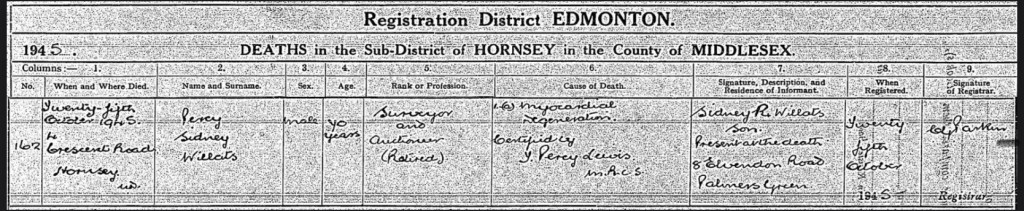

Dr. Pierce's Invalids Hotel and Surgical Institute was a prominent medical institution located at 665 Main Street in Buffalo, Erie, New York, USA. Founded by Dr. R.V. Pierce in the late 19th century, the institute gained widespread recognition for its innovative treatments and medical care. Dr. Pierce, a well-known figure in the medical community at the time, established the institute with a focus on providing specialized care for chronic ailments and surgical procedures.