Every family has its stories, and among them, there are those who leave their mark not through grand gestures, but through the quiet strength of their lives. For our family, Frederick Howard Willats is one such figure. Born in 1877 in the vibrant heart of Highbury, Islington, Middlesex, England, Frederick’s life reflects the spirit of his time, a bridge connecting us to the world as it once was.

As I delved into the details of his early years, I felt as though I were uncovering a hidden treasure. His story isn’t just a piece of history; it’s a part of our family’s legacy, a thread that weaves through time to connect us to him. Through these carefully preserved records, Frederick’s resilience, courage, and quiet dignity come to life, reminding us how deeply our roots shape who we are today.

So, let me share with you what I’ve discovered, a glimpse into the early years of Frederick Howard Willats, 1877–1947, through the documents and stories that bring his memory alive. This is more than history—it’s family.

The Life of

Frederick Howard Willats,

1877-1947,

The Early Years Through Documentation.

Welcome to Highbury, Islington, Middlesex, England, in the year 1877. Picture the cobblestone streets and terraced houses, alive with the hum of Victorian life. It’s a neighborhood of contrasts, where the energy of industrial progress dances alongside the struggles of working-class families.

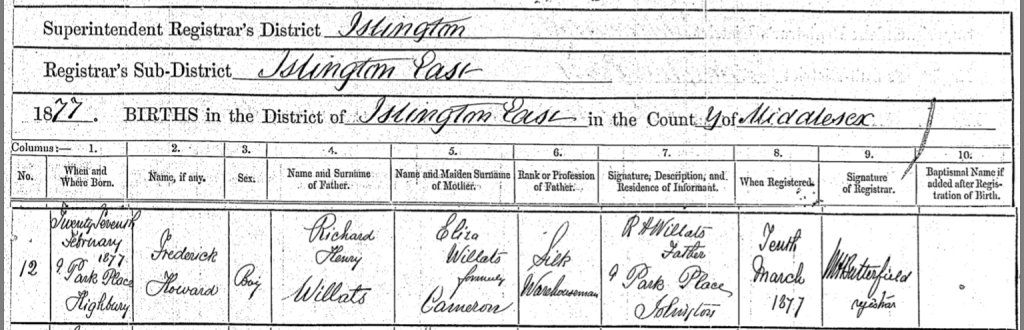

This is where Frederick Howard Willats, a pivotal figure in our family’s story, began his journey. On a Tuesday, February 27th, 1877, Frederick entered the world at Number 9, Park Place, Highbury. His parents, my 3rd Great Granduncle Richard Henry Willats and 4th Great Grandmother Eliza Willats (née Cameron), welcomed him into a home full of promise and challenges.

Frederick’s father, Richard, worked as a silk warehouseman, a job that carried its own set of demands in a rapidly changing economy. Just over a week later, on March 10th, 1877, Richard registered his son’s birth, marking the beginning of Frederick’s story in the official records. The family’s residence, nestled in the heart of Highbury, was part of a community where neighbour's knew each other by name and supported one another through life’s ups and downs.

Childbirth in 1877 was far from the clinical, hospital-centered experience we know today. It was deeply personal, unfolding at home, often in the presence of a midwife and close female relatives. For Eliza, giving birth to Frederick would have been both a moment of joy and one fraught with risks. Medical practices of the time were rudimentary, and complications were all too common. Yet, families leaned on the wisdom of the women around them, knowledge handed down through generations, to navigate this transformative experience.

Despite the challenges, the arrival of a child like Frederick was a cause for celebration. The home would have been filled with a mix of relief and excitement, a new chapter beginning in the life of the Willats family.

Highbury itself was a microcosm of Victorian England. Its streets buzzed with activity: merchants calling out their wares, factory bells marking the hours, and horse-drawn carriages weaving through crowds. For some, life here meant opulence, stately homes and tailored suits spoke of privilege. But for others, life was a daily struggle against poverty, overcrowding, and substandard housing.

Yet, even in the face of hardship, community thrived. Neighbors came together, offering each other support and companionship. It was a place where gossip flowed as freely as the gas lamps flickered in the evening streets, and where milestones, whether royal events or a neighbour’s new baby, were marked with shared excitement.

Against this vibrant, sometimes harsh backdrop, Frederick Howard Willats began his life. Born into an era of change and resilience, his story, like so many others in our family, is one of quiet endurance and strength. Each detail, from his birth in Park Place to the silk trade his father worked in, connects us to a past that shaped not only him but the generations that followed.

Frederick’s birth wasn’t just a historical fact; it was a moment that started a journey, one that echoes through our family history. It’s a story of life, love, and the resilience that defines us, even now.

In the late 1800s, Park Place in Highbury, Islington would have been part of a rapidly developing suburban area on the outskirts of London. Islington itself was undergoing significant urbanization during this period, transitioning from rural farmland to a more densely populated residential area.

Park Place, likely characterized by elegant terraced houses and grand Victorian architecture, would have been home to middle and upper-middle-class families seeking refuge from the crowded and industrialized city center. These residences would have boasted spacious interiors, adorned with ornate furnishings and fixtures, reflecting the wealth and status of their occupants.

The streets would have been bustling with activity, with horse-drawn carriages traversing the cobblestone roads and pedestrians going about their daily routines. Local shops, markets, and taverns would have catered to the needs and desires of the residents, creating a sense of community within the neighborhood.

In the late 1800s, Islington was also known for its cultural diversity, with immigrants from various parts of the British Isles and beyond settling in the area. This would have added vibrancy to Park Place, enriching its social fabric with different languages, customs, and traditions.

Despite the rapid urbanization of the late Victorian era, elements of greenery and open spaces would likely still have been present in Park Place, providing residents with a welcome respite from the hustle and bustle of city life. Nearby parks and gardens would have offered opportunities for leisurely strolls and outdoor recreation, enhancing the quality of life for those fortunate enough to call Park Place home.

Overall, Park Place in Highbury, Islington during the late 1800s would have been a flourishing suburban enclave, combining the comforts of urban living with the tranquility of a more pastoral setting, all against the backdrop of London's expanding metropolis.

In the spring of 1880, Frederick’s older brother, Henry Richard Willats, embarked on a significant chapter in his life. At 24 years old, Henry, a bachelor and publican, married 23-year-old Amelia Etheredge on Tuesday, March 30th, at All Saints Church in West Ham, Essex, England.

The couple’s union brought together two families and two lives rooted in different parts of London. Henry listed his residence as West Ham, while Amelia’s was given as Saint Paul’s, Shadwell. Their fathers were central figures in their lives and were proudly mentioned during the ceremony: Richard Henry Willats, Henry’s father, was a Licensed Victualler, and John Etheredge, Amelia’s father, worked as an Engineer.

The ceremony was witnessed by two of Amelia’s relatives, Charles Henry Etheredge and Alice Catherine Etheredge, who stood by the couple as they exchanged their vows. In that moment, the All Saints Church bore witness to a new beginning, one that added another layer to the story of the Willats and Etheredge families.

All Saints Church, located in West Ham, Essex, is a historic parish church with a rich heritage that dates back many centuries. The earliest recorded mention of a church on this site is in the 12th century, suggesting that a Christian community has existed here for nearly a thousand years. The church itself, as it stands today, is primarily the result of 13th-century construction, although it has undergone various modifications and restorations over the centuries.

The architecture of All Saints Church is a testament to the stylistic transitions and historical influences over the centuries. The church's nave, chancel, and south aisle are from the 13th century, showcasing the Early English Gothic style prevalent at the time. Notably, the south aisle was later extended, reflecting the growing congregation and the need for more space. The tower, a significant feature of the church, was added in the 14th century. Its robust and imposing structure was not only a place of worship but also served as a local landmark and a point of refuge in times of trouble.

During the medieval period, All Saints Church played a central role in the community's spiritual and social life. The churchyard served as a burial ground for local residents, and several notable figures from history have their final resting place here. Among these are members of the Lethieullier family, who were influential in the area during the 18th century.

The Reformation and subsequent religious changes in England had a profound impact on All Saints Church, as they did on many churches across the country. The church adapted to the new Protestant liturgy, and many of its medieval Catholic fittings and decorations were removed or altered. Despite these changes, the church maintained its position as a focal point of community life.

In the 19th century, the church underwent significant restoration, part of a broader Victorian movement to preserve and restore historic ecclesiastical buildings. This restoration aimed to return the church to its former glory while accommodating the needs of contemporary worshippers. The Victorian restorers were careful to respect the church's medieval heritage, although they did introduce some new elements in line with the tastes and liturgical practices of the time.

All Saints Church has continued to serve the spiritual needs of the West Ham community into the 21st century. It has witnessed the profound changes in the area, from its rural beginnings through industrialization to its current urban character. The church remains an important historical and cultural landmark, offering a sense of continuity amidst the rapid changes of the modern world.

Today, All Saints Church is not only a place of worship but also a venue for community events and activities. Its rich history is preserved in its architecture, its memorials, and the continuity of worship that has been maintained for centuries. The church's enduring presence is a testament to its significance in the life of West Ham, reflecting the broader history of the region and the nation.

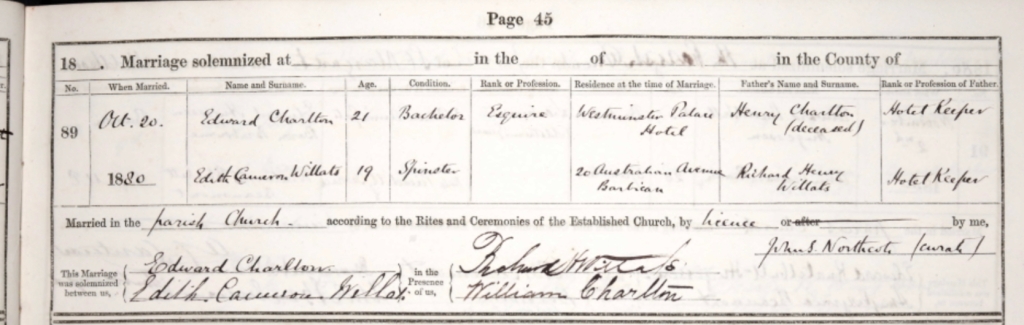

Frederick’s older sister, Edith Cameron Willats, celebrated her own milestone on Wednesday, October 20th, 1880. At just 19 years old, Edith married Edward Charlton, a 21-year-old bachelor and Esquire, in the beautiful St Margaret Church, George Hanover Square, Westminster, London.

The couple came from families with similar backgrounds, both fathers, Richard Henry Willats and Henry Charlton, were Hotel Keepers, an occupation that perhaps brought their families into contact and eventually led to Edith and Edward’s union.

Edith listed her address as 20 Australian Avenue, Barbican, Silk Street, St Giles, Westminster, while Edward’s residence was given as the Westminster Palace Hotel, a location that surely reflected his family's role in the hospitality industry.

Their wedding was witnessed by Richard Willats and William Charlton, likely close family members who stood by their sides as they exchanged vows. St Margaret Church, with its grand history and stunning architecture, provided a fitting backdrop for this union of two young hearts.

This moment in 1880 marked the beginning of a new chapter in Edith’s life and added yet another meaningful thread to the tapestry of the Willats family history. It’s a testament to the connections and partnerships that shaped the lives of our ancestors and continue to echo through our family story today.

St. Margaret’s Church, located in George Hanover Square, Westminster, London, is an iconic parish church with a distinguished history that dates back to the early 18th century. The church was built between 1711 and 1714, designed by the renowned architect John James, who worked under the guidance of Sir Christopher Wren. It stands as a prime example of the English Baroque style, characterized by its grand and elegant architecture.

The construction of St. Margaret’s was commissioned to serve the rapidly growing population of the newly developed Mayfair area. The church was consecrated in 1718 and quickly became a fashionable place of worship for the aristocracy and wealthy residents of the area. Its location in George Hanover Square, a prominent and affluent part of London, further enhanced its status.

The interior of St. Margaret’s Church is notable for its fine Georgian woodwork, including an impressive reredos and pulpit. The church also boasts a magnificent organ, originally built by Richard Bridge in 1740 and subsequently modified and restored over the centuries. The overall design and decor reflect the elegance and refinement of the period, making it a significant architectural and historical landmark.

By the 19th century, St. Margaret’s Church had firmly established itself as a popular venue for high society weddings. Marrying at St. Margaret’s in 1880, however, involved several steps and requirements. The process would have been relatively straightforward for most residents of the parish, especially given the church’s established role in the community.

To marry at St. Margaret’s in 1880, a couple needed to follow the legal requirements of the time. This included obtaining a marriage license or having banns (public announcements of the intended marriage) read out on three consecutive Sundays in the parish where both parties lived. If either party resided outside the parish, banns had to be read in their respective local parishes as well. Once the banns were read or a license obtained, the couple could proceed with arranging their wedding ceremony at the church.

The prominence of St. Margaret’s as a desirable wedding location meant that it was a popular choice, and securing a wedding date might require planning well in advance. Nonetheless, for those with the means and connections, marrying at St. Margaret’s was relatively accessible. The church’s central location in London, combined with its association with high society and the quality of its clergy, made it a sought-after venue for nuptials.

Weddings at St. Margaret’s in the late 19th century were often grand affairs, attended by large numbers of guests and covered in the society pages of newspapers. The church’s elegant interior provided a beautiful setting for the ceremony, and its location in the heart of London’s fashionable district added to the allure.

St. Margaret’s Church has continued to serve the spiritual needs of its parishioners and the broader community through the centuries. Today, it remains an active place of worship and a cherished historical site. Its legacy as a favored location for weddings endures, reflecting its longstanding reputation as one of London’s most prestigious parish churches.

On Sunday, April 3rd, 1881, the census was taken, capturing a snapshot of Frederick Howard Willats' family life during that time. The family resided at Number 61, Ambler Road, Islington, Middlesex, England, a home filled with both the busyness and warmth of a large household.

Frederick, listed as "Howard" in the records, lived with his parents, Richard and Eliza Willats, and his siblings: Francis (known as Frank), Arthur, Eliza, Walter, Lillian, Edwin Paul, May, and Percy Sidney. The house must have been lively, filled with the sounds of a bustling family managing daily life.

Richard, Frederick’s father, was recorded as a Publican who was "out of business" at the time, hinting at a possible challenge the family was navigating. Frank, the eldest sibling, was working as a General Agent, while Arthur had a position as a Clerk for solicitors, and Walter was a Clerk at the Stock Exchange. The younger siblings, including Frederick, Eliza, Lillian, Edwin, May, and Sidney, were all listed as scholars, attending school and building the foundations of their futures.

Adding to the dynamics of the household was a guest, Henry Anstey, who was staying with the family. Interestingly, he was noted as an Enumerator (though with no specific occupation listed), perhaps contributing to the census-taking process.

The census provides a unique glimpse into the life of the Willats family during this period, showing not only their individual roles but also the strong sense of family and shared experiences that bound them together. For Frederick, or Howard as he was recorded, these were formative years spent surrounded by siblings and the daily rhythms of a family navigating both challenges and opportunities in Victorian England.

61 Ambler Road, located in the London Borough of Islington, is a typical residential address in a part of North London known for its Victorian and Edwardian architecture. Ambler Road itself is situated in the Finsbury Park area, an area that developed significantly during the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The history of 61 Ambler Road likely begins in the late 19th century when much of this part of Islington was developed. During this period, London was experiencing rapid expansion and urbanization, driven by the growth of the railway network and the increasing population. Victorian terraces and semi-detached houses were built to accommodate the burgeoning middle class and working population moving to the city for employment opportunities.

Ambler Road and its surrounding streets would have been part of this development boom, characterized by rows of brick houses with bay windows, decorative stonework, and small front gardens. The architecture typically reflects the Victorian style, with some Edwardian influences evident in later modifications and neighboring constructions.

Throughout its history, 61 Ambler Road has likely been home to a variety of residents. Initially, the inhabitants would have been middle-class families, possibly including professionals such as clerks, teachers, or small business owners, reflecting the socio-economic makeup of the area at the time. Census records from the late 19th and early 20th centuries would provide specific details about the individuals and families living there, offering insights into their occupations, family structures, and origins.

In the mid-20th century, like much of London, the area saw significant demographic changes. The aftermath of World War II and subsequent social changes brought a more diverse population to Islington. The housing policies and urban renewal projects of the post-war period might have also impacted the residents and the structure of housing on Ambler Road. During this time, houses that were once single-family homes might have been subdivided into flats or boarding houses to accommodate the housing needs of a growing and changing population.

By the late 20th and early 21st centuries, Islington, including the Finsbury Park area, began to experience gentrification. The proximity to central London and improved transport links made it an attractive location for young professionals and families. This period likely saw a shift back towards owner-occupiers and an increase in property values. Renovations and restorations became common as new residents invested in updating the Victorian properties while retaining their historical charm.

Today, 61 Ambler Road, like many houses in the area, would be part of a vibrant and diverse community. The residents are likely to include a mix of long-term locals and newer arrivals, contributing to the rich social tapestry of Islington. The area benefits from its close proximity to Finsbury Park, a major green space offering recreational facilities and events, as well as the array of shops, cafes, and restaurants that cater to the diverse tastes of its inhabitants.

On Wednesday, July 6th, 1881, Frederick’s brother, Francis Montague Allen Willats, known to the family as Frank, entered a new chapter of his life. At 23 years old, Frank married 25-year-old Margaret Jane McLennon at St John’s Church in Hornsey, Middlesex.

Frank, a bachelor and agent at the time, and Margaret, a spinster, brought together two families with their union. Their fathers proudly stood in the records: Richard Henry Willats, noted as an Agent, and John McLennon, a skilled Chronometer Maker.

The couple came from nearby neighborhoods, with Frank residing at 145 Blackstock Road and Margaret at 84 Finsbury Park Road. Their wedding was witnessed by Margaret’s family members, John McLennon and Jessie McLennon, adding a touch of familial support to the occasion.

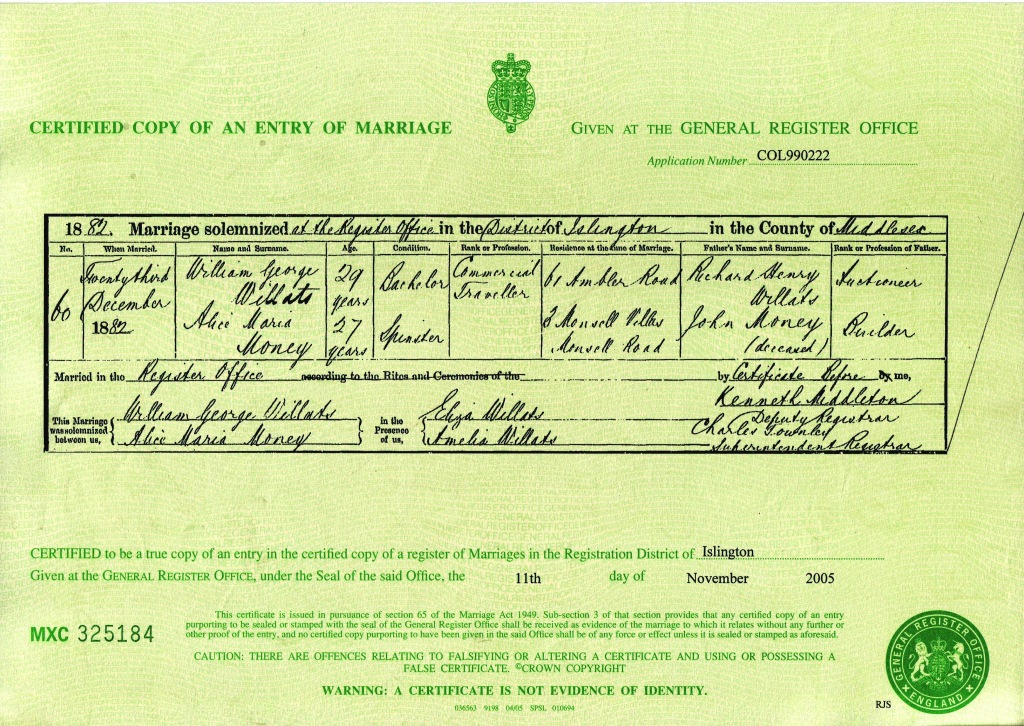

On Saturday, December 23rd, 1882, Frederick’s half-brother, William George Willats, took a significant step in his life, marrying Alice Maria Money at The Register Office in Islington, Middlesex. At 29 years old, William was a bachelor and Commercial Traveller, and Alice, aged 27, was a spinster.

William and Alice’s union bridged two families and was a poignant moment in the Willats family history. William’s father was recorded as Richard Henry Willats, an Auctioneer, though William was actually the son of Eliza Willats (née Cameron) and George John Willats, Frederick’s paternal uncle. Alice’s father, John Money, a Builder, was noted as deceased at the time of their marriage.

The ceremony was witnessed by two important family members, Eliza Willats and Amelia Willats, both standing as a testament to the support and love surrounding the couple on their special day.

William and Alice’s story is a reminder of the layered connections within our family tree, with William being both a half-brother to Frederick and a link between two branches of the Willats lineage. Their marriage, held just two days before Christmas, surely brought a sense of joy and celebration to the family as they closed out the year with this happy occasion. You can read all about his life here and here.

In 1886, across the Atlantic in Buffalo, Erie, New York, Frederick’s brother Arthur Charles Willats married Josephine Mary Conley. Though I have yet to uncover documentation of their marriage, relying instead on census records and the births of their children, it remains a significant chapter in our family’s story.

For the Willats family, the distance between England and America must have felt insurmountable. They would have had to come to terms with the bittersweet reality of celebrating Arthur’s marriage from afar, unable to be at his side as he began this new chapter of his life. Letters may have carried their best wishes and advice, but it surely wasn’t the same as being present to share in the joy of the day.

As for Frederick, it’s unclear whether he ever met Arthur by this point in their lives. Perhaps he had heard stories of his older brother’s journey to America, imagining what his life might be like in a faraway land. Or perhaps Arthur’s life in Buffalo remained something of a mystery to Frederick, their paths not yet crossing in a meaningful way.

This moment in 1886 reminds us of the challenges of maintaining family bonds across great distances, particularly in an era when communication and travel were far more difficult. Yet, even without physical presence, the strength of the Willats family connection undoubtedly endured, carried through letters, memories, and the shared hope for each other’s happiness.

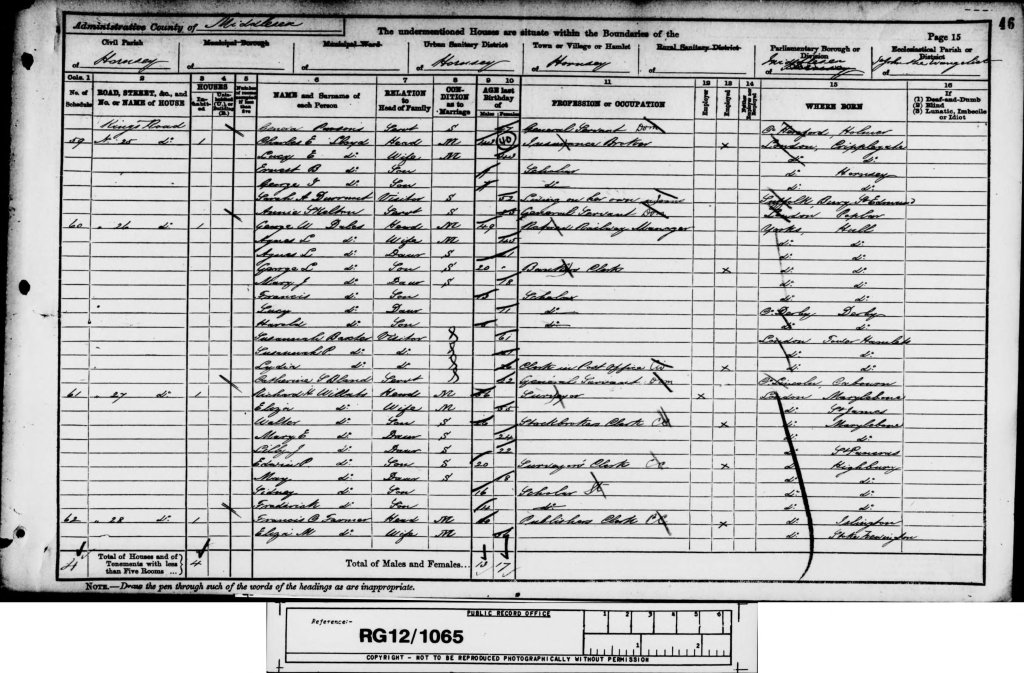

On a quiet Sunday evening, April 5th, 1891, the Willats family gathered under the roof of their home at 27 Kings Road, Hornsey, in Islington, Middlesex. As the 1891 census was taken, it captured a moment in their shared lives, a snapshot of a family deeply connected, each member contributing to the rhythm of their household.

Richard Willats, Frederick’s father, was at the helm as the head of the family, working tirelessly as a self-employed surveyor. His efforts were mirrored by his sons: Walter, who had carved a path for himself as a stockbroker’s clerk, and Edwin, who followed a similar direction, working as a surveyor’s clerk. Together, their hard work ensured the family’s continued stability and progress.

Frederick’s siblings May, Percy, Lily, and Edwin were also part of the household, their lives intertwined under the roof that served as more than just a home, it was the heart of their family. Here, they laughed, argued, celebrated, and supported one another, their shared experiences shaping the foundation of their lives.

27 Kings Road wasn’t merely an address; it was a sanctuary in the bustling district of Hornsey, a place where love, effort, and togetherness wove the threads of the Willats family story.

27 Kings Road in Hornsey, located within the London Borough of Islington, is a residential address with a history that reflects the broader development patterns of the area. Hornsey is one of London's oldest suburbs, with a history that stretches back to medieval times. By the 19th century, Hornsey had transitioned from a rural village to a more suburban area, driven by the expansion of the railway network and the increasing population of London.

The specific history of 27 Kings Road would be tied to the urban development that took place in Hornsey during the Victorian era. Much of the housing in this area, including Kings Road, was constructed in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. This period saw the construction of many terraced houses, which were designed to accommodate the growing middle class who were moving to the suburbs in search of better living conditions than those found in the crowded inner city.

The houses on Kings Road, including number 27, would likely have been built during this building boom, featuring the architectural characteristics typical of the time. These would include brick facades, sash windows, and perhaps decorative elements such as bay windows or iron railings. The development of these homes was part of a larger trend of suburbanization that offered more spacious and healthier living environments compared to the densely populated urban areas.

Throughout the 20th century, the residents of 27 Kings Road would have experienced the social and economic changes that affected Hornsey and the wider London area. In the early part of the century, the area would have been home to a mix of professionals, skilled workers, and their families. The impact of both World Wars would have brought changes to the community, with the local population contributing to the war efforts and coping with the aftermath of wartime destruction and rationing.

The mid-20th century saw significant changes in Hornsey, as with much of London, including post-war rebuilding and modernization. During this time, there was also an increase in cultural and ethnic diversity as new waves of immigrants settled in London, contributing to the rich social fabric of the area. Properties like 27 Kings Road might have seen changes in ownership and possibly alterations to their structure to adapt to modern living standards, such as the addition of indoor plumbing, central heating, and electricity.

By the latter half of the 20th century and into the 21st century, Hornsey began to experience gentrification. Rising property values and an influx of young professionals looking for convenient commuting options into central London brought renewed interest and investment in the area. Houses like 27 Kings Road were likely refurbished to restore or enhance their Victorian charm while incorporating modern amenities.

Today, 27 Kings Road stands as part of a vibrant and diverse community in Hornsey. The area benefits from its proximity to green spaces such as Alexandra Park and Finsbury Park, excellent transport links including nearby rail and Underground stations, and a variety of local shops, cafes, and restaurants. The history of the house reflects the broader narrative of suburban development in London, from Victorian expansion through 20th-century challenges to 21st-century rejuvenation.

To gain a deeper understanding of the specific history of 27 Kings Road, local archives, historical records, and property documents held by the Islington Local History Centre or the London Metropolitan Archives could provide detailed information about its construction, ownership, and the lives of its residents over the years.

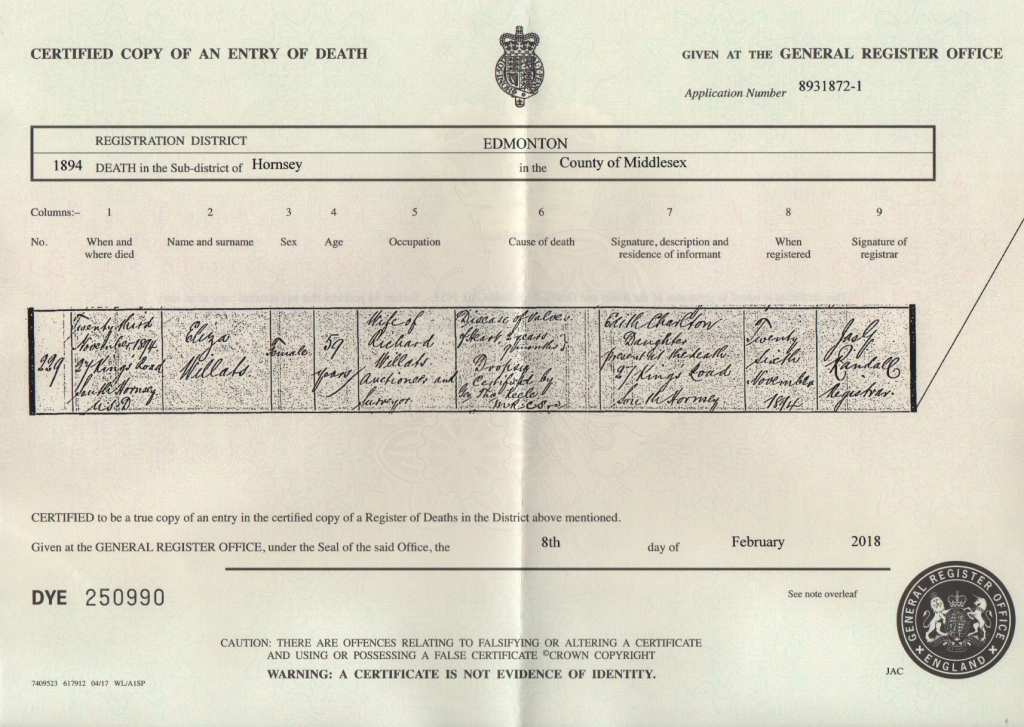

Frederick’s world was forever changed on a somber Friday, the 23rd of November, 1894. His beloved mother, Eliza Willats, née Cameron, passed away in the warmth of their family home at 27 Kings Road, South Hornsey, Edmonton, Middlesex. She was just 59 years old, a woman whose life had been a beacon of love and devotion to her family.

Eliza’s passing was the result of a long and challenging battle with a heart condition, compounded by dropsy. For two years and nine months, she bore her illness with quiet strength, surrounded by the care and love of her family. In her final moments, her daughter Edith Charlton stood by her side, offering comfort and unwavering presence as her mother slipped away.

On the 26th of November, Edith, carrying the heavy weight of grief, fulfilled the solemn duty of registering her mother’s death. Eliza’s loss left a profound emptiness in the hearts of her loved ones, and the family home at 27 Kings Road, once filled with her gentle warmth and nurturing spirit, would never feel the same again.

Eliza’s legacy of kindness, strength, and love remains a cherished memory, held tenderly by her children and all who knew her.

Heart valve disease and dropsy, also known as edema, are significant medical conditions that affect the cardiovascular system.

Heart valve disease involves malfunctioning of one or more valves in the heart. The heart has four valves (mitral, tricuspid, aortic, and pulmonary) that ensure blood flows in the correct direction. When these valves do not open or close properly, blood flow can be obstructed or leak backwards (regurgitate), leading to various symptoms and complications.

Valve diseases can be categorized as stenosis (where the valve opening is narrowed, restricting blood flow) or regurgitation (where the valve does not close tightly, allowing blood to leak back). Causes of valve disease include congenital heart defects, infections (such as endocarditis), rheumatic fever, and age-related degeneration. Symptoms may include chest pain, fatigue, shortness of breath, palpitations, and swelling in the ankles, feet, or abdomen.

Diagnosis typically involves physical exams, imaging tests (like echocardiography), and sometimes cardiac catheterization. Treatment depends on the severity of the condition and may include medications to manage symptoms, antibiotics for infections, and in severe cases, surgical repair or replacement of the affected valve.

Dropsy, or edema, refers to the abnormal accumulation of fluid in tissues throughout the body, leading to swelling. This condition is often a symptom rather than a disease itself and can occur due to various reasons, including heart failure, kidney disease, liver disease, venous insufficiency, and certain medications.

In heart failure, for example, the heart's inability to pump blood effectively can cause fluid to build up in the lungs (pulmonary edema) or in peripheral tissues (peripheral edema). Symptoms of edema include swelling of the legs, ankles, or abdomen, sudden weight gain, and sometimes shortness of breath.

Treatment of edema involves addressing the underlying cause. This may include lifestyle changes (such as reducing salt intake and elevating legs), medications (like diuretics to reduce fluid retention), and management of the underlying condition (such as treating heart failure or kidney disease).

Both heart valve disease and dropsy are serious conditions that require medical attention and management to prevent complications and improve quality of life for affected individuals.

Losing his mother at such a tender and impressionable age must have left a deep and lasting mark on Frederick Howard Willats, touching the core of his young heart in ways both profound and heart-wrenching. Though he was surrounded by a large and loving family who surely enveloped him in care, kindness, and tenderness, the absence of his mother’s nurturing presence would have been an ache that no amount of love could fully ease.

Her loss would have cast a quiet shadow over his formative years, a void where her gentle guidance and unconditional love should have been. In that emptiness, Frederick likely found a wellspring of resilience, shaped by the bittersweet understanding of life’s fragility and the irreplaceable value of those we hold dear.

This early heartbreak may have become a silent yet steadfast influence, shaping his relationships with those around him and deepening his capacity for empathy. It likely colored his aspirations and infused his life with a sensitivity to the fleeting nature of joy and the importance of treasuring every moment. In ways both seen and unseen, this profound loss helped mold the man he would become, embedding in him a strength born from sorrow and a heart touched by compassion.

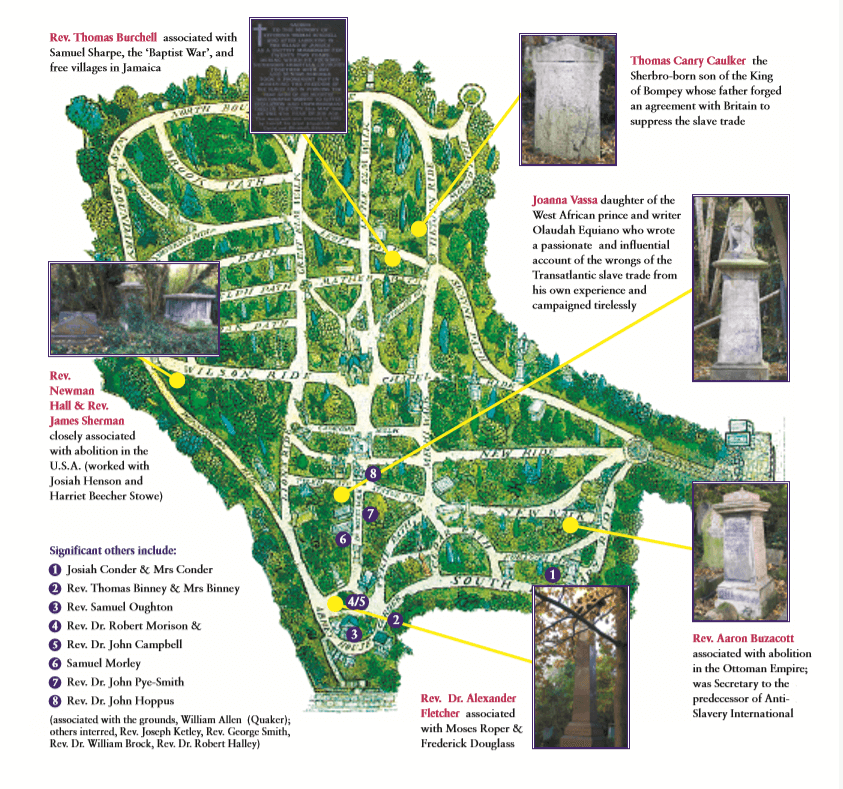

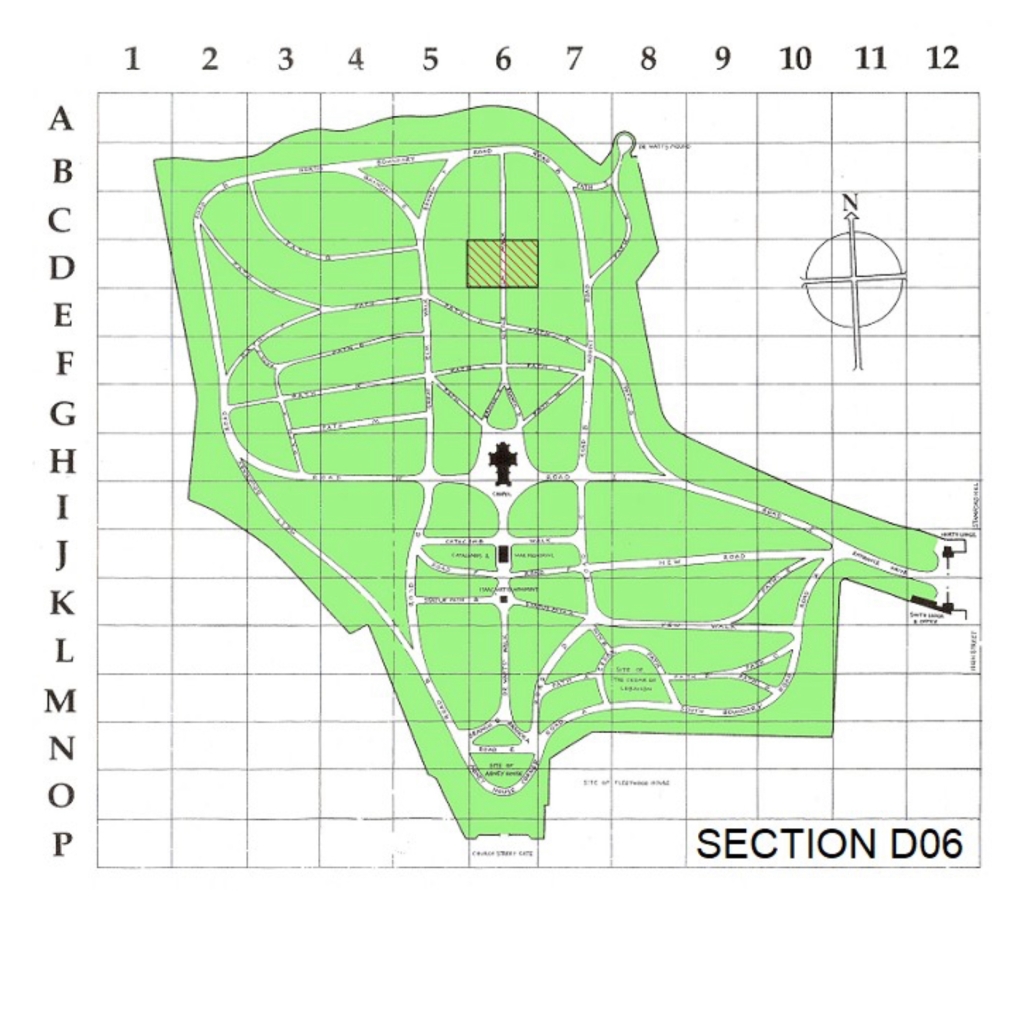

With heavy hearts and profound grief, the Willats family laid their beloved Eliza to rest on a cold Thursday, the 29th of November, 1894. She was buried in the tranquil grounds of Abney Park Cemetery, a serene haven at 215 Stoke Newington High Street, Stoke Newington, London. Her final resting place, marked in D06, Grave 092431, bore witness to the love and devotion of the family she left behind.

Eliza’s home at the time of her passing, Number 27 Kings Road, Brownswood Park, had been a place of warmth and family, now dimmed by her absence. In his grief, Richard Henry, her devoted husband, ensured that her burial was not only a moment of farewell but a gesture of enduring care. He purchased two graves in the verdant grounds of Abney Park, a former garden estate transformed into a peaceful cemetery.

Each grave, costing three guineas, was a solemn investment in the family’s future, a resting place for six souls per plot, a tender acknowledgment of life’s finite journey. The cemetery, with its lush greenery and quiet dignity, stood as a testament to the love that surrounded Eliza in life and followed her into eternity.

For those who mourned her, this sacred place became a refuge, a space to remember and honor a life filled with kindness and devotion. Eliza’s memory would live on, cherished in their hearts and in the stillness of Abney Park, where love and loss found a quiet home together.

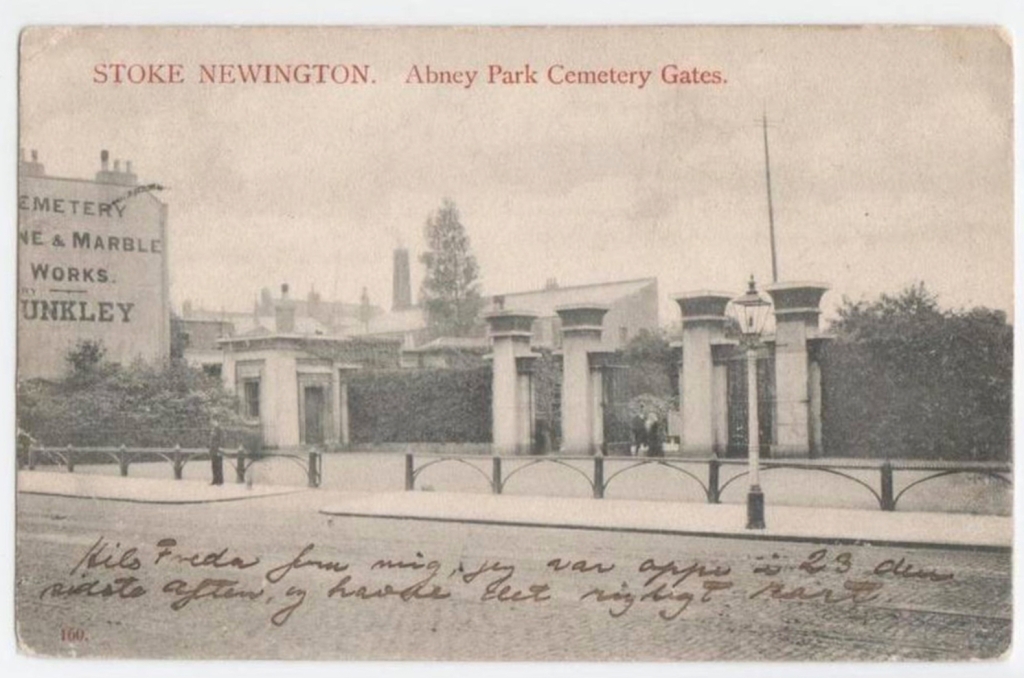

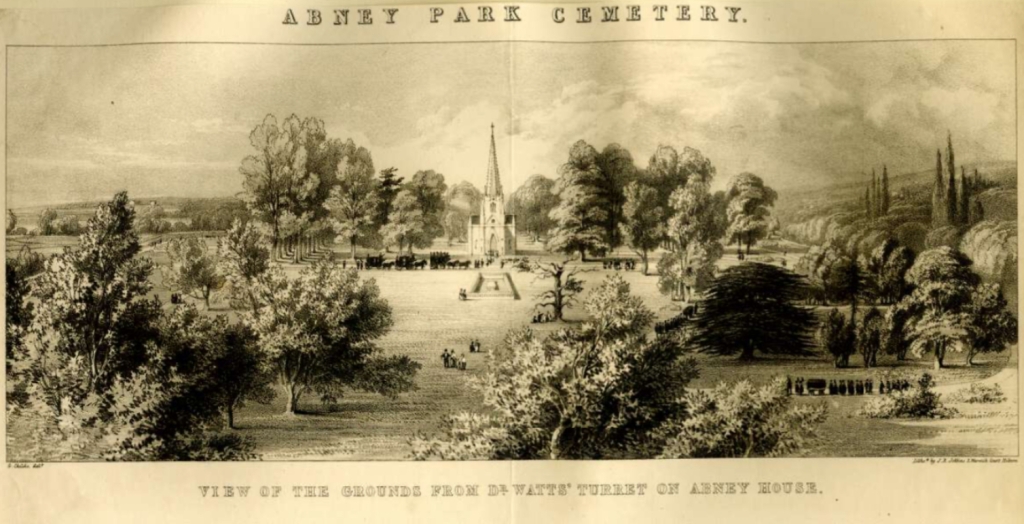

Abney Park Cemetery, located in Stoke Newington, London, is not just a burial ground but a place steeped in history, culture, and natural beauty. Established in 1840 as a non-denominational cemetery, it was one of the "Magnificent Seven" garden cemeteries built in the Victorian era to alleviate overcrowding in London's existing churchyards. The cemetery was named after Sir Thomas Abney, who owned the land in the 18th century.

Designed as a garden cemetery, Abney Park was intended as a tranquil space where people could visit their departed loved ones and enjoy the serenity of nature. The layout features winding paths, ornate mausoleums, and overgrown greenery, giving it a picturesque and somewhat gothic atmosphere.

Over the years, Abney Park Cemetery has become not only a final resting place but also a sanctuary for wildlife, with many bird species and other animals calling it home. The cemetery's diverse flora includes rare and exotic trees, adding to its allure as a peaceful urban oasis.

Beyond its natural beauty, Abney Park holds significant historical and cultural importance. Many notable figures are buried here, including novelists, activists, scientists, and musicians. Among them are William and Catherine Booth, founders of the Salvation Army, and the radical political philosopher and writer, Mary Wollstonecraft.

However, Abney Park's history is not without its challenges. In the latter half of the 20th century, the cemetery fell into disrepair due to neglect and lack of funding. Nature reclaimed much of the grounds, with ivy-covered monuments and crumbling tombs adding to its eerie charm. Efforts have been made in recent years to restore and maintain the cemetery, with volunteers and local organizations working to preserve its heritage and biodiversity.

Today, Abney Park Cemetery stands as a unique blend of history, nature, and community. It serves as a place of remembrance, a haven for wildlife, and a cultural landmark in the heart of London. Visitors can explore its winding paths, pay their respects to the departed, and appreciate the beauty of this historic green space.

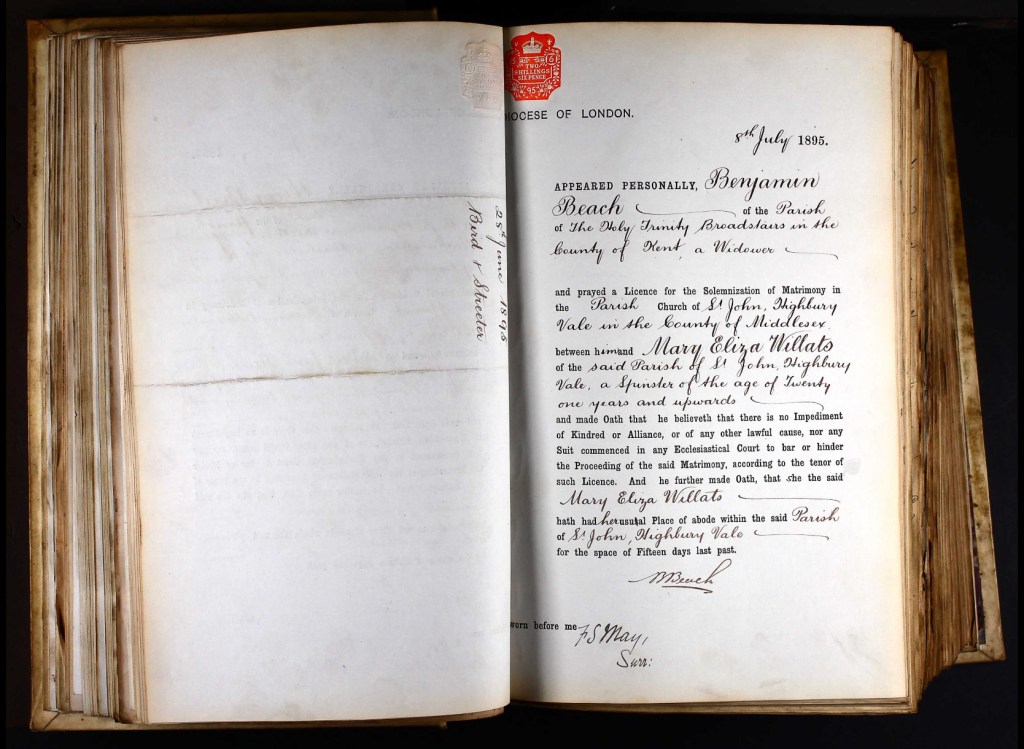

After the passing of Frederick and his siblings’ beloved mother, Eliza, the Willats family found a glimmer of joy amidst their grief. On Monday, July 8th, 1895, at St John Church in Highbury Vale, Kent, England, a new chapter unfolded with the marriage bonds and allegations of Frederick’s sister, Eliza Mary, known to the family as Mary Eliza.

The record reads like a testament to the hope and continuity of life:

DIOCESE OF LONDON

8th July 1895.

APPEARED PERSONALLY, Benjamin Beach of the Parish of The Holy Trinity Broadstars in bounty of Kent a Widower and prayed a Licence for the Solemnization of Matrimony in Parish church of St John Highbury Vale, in the county of Middlesex between Mary Eliza Willats, of the said Parish of St John Highbury Vale, a spinster of the age of Twenty one years and upwards and made Oath that he believeth that there is no Impediment of Kindred or Alliance, or of any other lawful cause, nor any Suit commenced in any Ecclesiastical Court to bar or hinder the Proceeding of the said Matrimony, according to the tenor of such Licence. And he further made Oath, that she the said Mary Eliza Willats hath had her usual Place of abode within the said Parish of St John, Highbury Vale for the space of Fifteen days last past. Sworn before me F. S. May, Surr:

For the Willats family, this moment must have brought a much-needed smile, a celebration of love and renewal after a period of loss. Mary Eliza, stepping into her future with Benjamin Beach, brought light back into the family’s narrative. It also highlights the formality and solemnity of such an occasion in Victorian England, where bonds of marriage were not just a personal union but also a cherished community event.

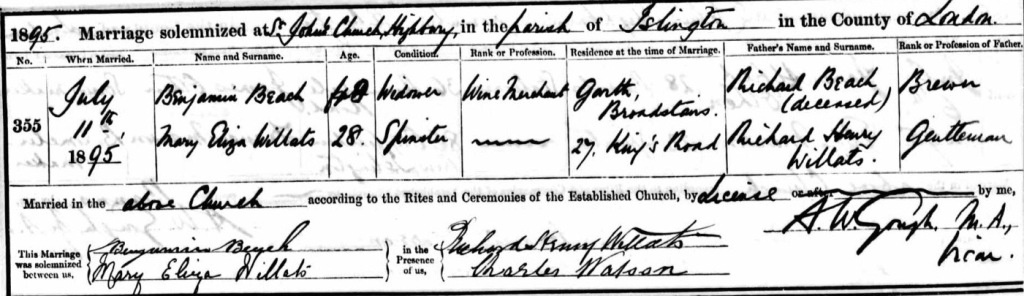

Frederick’s sister, 28-year-old Eliza Mary Willats, known as Mary Eliza, stepped into a new chapter of her life on Thursday, the 11th of July, 1895. On that day, she married 48-year-old widower and wine merchant Benjamin Beach in a heartfelt ceremony at St John’s Church in Highbury, Islington, Middlesex, England.

Mary, described as a spinster, gave her address as the family home at 27 Kings Road, while Benjamin’s residence was not recorded in full. They honored their fathers during the ceremony, naming them as Richard Beach, a brewer (deceased), and Richard Henry Willats, a gentleman.

The couple exchanged their vows surrounded by loved ones. Among the witnesses were Mary’s father, Richard Henry Willats, and a family acquaintance, Charles Watson. The marriage register reflects Mary’s use of her middle name, listing her as Mary Eliza Willats.

This union, bridging two lives shaped by different journeys, marked a moment of joy and hope for the Willats family amidst the ebb and flow of life’s changes.

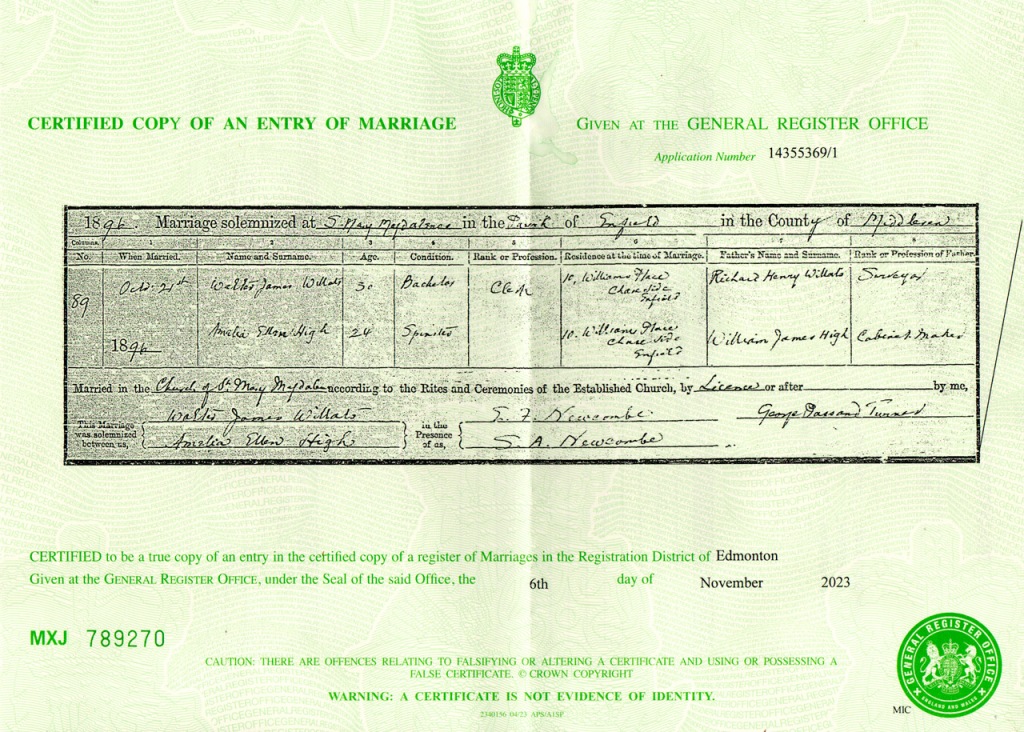

On Tuesday, October 20th, 1896, Frederick’s brother, Walter James Willats, at 21 years old, married Amelia High, also 21, in a moment of joy that marked a new chapter in their lives. The couple’s marriage bond was officially licensed at St Mary Magdalene, Enfield, Middlesex, England. Their marriage licence document, preserved for posterity, reads as follows:

DIOESE OF LONDON.

20th October 1896

APPEARED PERSONALLY, Walter James Willats of the parish of St Mary Magdalene Enfield in the County of Middlesex a Bachelor aged Twenty one years and upwards and prayed a Licence for the Solemnization of Matrimony in the parish church of St Mary Magdalene Enfield aforesaid between him and Amelia Ellen High of the same parish a sphincter of the age of Twenty-one years and upwards and made Oath that he believeth that there is no Impediment of Kindred or Alliance, or of any other lawful cause, nor any Suit commenced in any Ecclesiastical Court to bar or hinder the Proceeding of the said Matrimony, according to the tenor ofsuch Licence. And he further made Oath, that he the said Appearer hath had his usual Place of abode within the said of St Mary Magdalene Enfield for the space of Fifteen days last past. Walter James Willats Sworn before me F S May Swn:

This moment, occurring just over a year after the Willats family had celebrated Mary Eliza’s marriage, was another bright chapter in the family’s journey. Walter, the younger brother of Frederick, took his step forward, joined by Amelia in a union that carried with it the promise of new beginnings.

On Wednesday, October 21st, 1896, Frederick’s brother, Walter James Willats, 30 years old and a bachelor, married 24-year-old Amelia Ellen High, a spinster, at St Mary Magdalene Church in Enfield, Middlesex. This was a momentous occasion for the Willats family, as Walter, a clerk by profession, embarked on a new chapter with Amelia by his side.

At the time of their marriage, they were living together at Number 10, William Place, Chase Side, Enfield, a place that must have felt like home as they began their lives together. In the marriage record, Walter and Amelia provided the names and occupations of their fathers: Richard Henry Willats, a Surveyor, and William James High, a Cabinet Maker. These details were more than formalities; they spoke to the lives and trades that had shaped their families up to this point.

Their wedding was witnessed by E. F. Newcombe and S. A. Newcombe, whose presence at the ceremony marked the support of friends or perhaps extended family. This union, celebrated in the heart of Enfield, was another proud moment for the Willats family, one that reminded them of how life moves forward even after hardship, and that love and commitment always have the power to bring joy to the heart of a family.

As with each new chapter in the Willats family, it’s clear that this wedding marked not only a personal milestone for Walter and Amelia but also a continuation of family bonds, tradition, and the promise of a shared future.

Heartbreakingly, the family’s newfound joy was all too fleeting, giving way to yet another wave of sorrow. On Sunday, the 14th of February, 1897, a day steeped in loss, Frederick’s half-brother, William George Willats (my 3rd Great-Grandfather), passed away at the age of 43. William, an estate bailiff and a steadfast figure in the family, breathed his last at his home, 44 Gillespie Road, Islington, Middlesex.

The cause of his passing, a cardiac hemorrhage leading to coronary syncope, was sudden and devastating. For a family still mending from past grief, his loss came as a profound blow, leaving behind an emptiness felt deeply by all who loved him.

Their sister, Charlotte Ellen Crosbie, bearing the weight of her own grief, was present at William’s side in his final moments. In an act of quiet strength and devotion, she took on the solemn duty of registering his death on the 16th of February, ensuring his passing was recorded with care and dignity.

William’s untimely death was a cruel reminder of life’s fragility, casting a shadow over the hearts of those he left behind. For Frederick and his family, the pain of this loss became another thread in the fabric of their shared resilience, a bittersweet testament to the love and connection that bound them together through life’s trials.

Cardial hemorrhage, also known as cardiac hemorrhage, refers to bleeding that occurs within or around the heart. This condition can be caused by various factors, including trauma, underlying cardiovascular diseases, or complications of medical procedures.

One common cause of cardial hemorrhage is a myocardial infarction, or heart attack, where the blood supply to a part of the heart muscle is interrupted, leading to tissue damage and potential bleeding. Another cause could be an injury to the heart during surgery or a cardiac catheterization procedure.

Symptoms of cardial hemorrhage can vary depending on the location and severity of the bleeding but may include chest pain, difficulty breathing, rapid heartbeat, fainting, or signs of shock such as low blood pressure and pale skin. Diagnosis typically involves imaging tests such as echocardiography or CT scans to locate and assess the extent of the bleeding.

Treatment of cardial hemorrhage depends on the underlying cause and severity of the condition. Immediate medical intervention may be necessary to stabilize the patient, control bleeding, and address any underlying cardiovascular issues. This could involve medications to promote blood clotting, surgery to repair damaged blood vessels or tissues, or other interventional procedures.

Corona syncope, also known as vasovagal syncope or neurally mediated syncope, refers to a temporary loss of consciousness caused by a sudden drop in blood pressure, which reduces blood flow to the brain. This condition can be triggered by various factors, including emotional stress, pain, dehydration, prolonged standing, or sudden changes in body position.

During a corona syncope episode, individuals may experience symptoms such as dizziness, lightheadedness, nausea, sweating, and a pale complexion before losing consciousness briefly. Typically, consciousness returns quickly once the individual lies down and blood flow to the brain improves.

Diagnosis of corona syncope involves a thorough medical history, physical examination, and sometimes additional tests such as tilt-table testing or heart rhythm monitoring to rule out other potential causes of fainting episodes.

Treatment for corona syncope focuses on identifying and avoiding triggers that provoke episodes. Lifestyle modifications such as staying well-hydrated, avoiding prolonged standing, and practicing stress management techniques can be helpful. In some cases, medications or maneuvers like leg crossing and muscle tensing (to increase blood pressure) may be prescribed to prevent syncope episodes.

Both cardial hemorrhage and corona syncope are serious conditions that require medical evaluation and management to determine the underlying cause and provide appropriate treatment to prevent complications and improve patient outcomes.

With heavy hearts and profound sorrow, the Willats family gathered on Thursday, the 18th of February, 1897, to lay William George Willats to rest. In the quiet embrace of Abney Park Cemetery at 215 Stoke Newington High Street, Stoke Newington, London, William was interred in grave D06 092431, alongside his beloved mother, Eliza Willats, née Cameron.

This final resting place became a poignant symbol of the family’s enduring bonds, a place where love transcended loss. Over time, his father, Richard, his brother, Percy Sidney, and his nephew, Francis Paul Willats, would join them there, creating a shared sanctuary of peace and memory.

For the grieving family, this sacred plot was more than a burial site, it was a haven of connection, a tangible reminder that even in death, their ties remained unbroken. As they said their goodbyes to William, they found solace in knowing he was reunited with his mother, resting in the serene beauty of Abney Park, where their spirits would forever be entwined.

Leaping forward to 1899, Frederick’s sister, 29-year-old Lilly Jenny Willats, took a joyous step into married life. On a bright Saturday, the 15th of July, 1899, she exchanged vows with 31-year-old bachelor William Alexander Neilson at St. John’s Church in Highbury, Islington, Middlesex, England.

Lilly, described as a spinster on the record, married William, whose occupation was listed as “commercial”, likely a commercial traveler. Both proudly named their fathers during the ceremony: Richard Henry Willats, noted as an auctioneer, and William Neilson, also listed as “commercial.”

At the time of their marriage, Lilly was living at the family home, 27 Kings Road, Brownhill Park, while William resided at Madeira Avenue in Worthing, Sussex. Their union was witnessed by Lilly’s brother-in-law, Benjamin Beach, and her niece, Amina Charlton, who both stood by to celebrate this new chapter in her life.

Interestingly, Lilly was formally recorded as “Lillian” on the marriage certificate, a touch of formality for a day filled with love and promise. This union marked a moment of hope and new beginnings for the Willats family, a bright spot in their ongoing story.

On Saturday, July 7th, 1900, another chapter of the Willats family story unfolded as Frederick’s brother, Edwin Paul Willats, 28 years old and an auctioneer, married 19-year-old Nellie Elizabeth High at All Hallows Church in Tottenham, Edmonton, Middlesex. It was a joyous occasion, as Edwin embarked on his journey into married life with Nellie by his side.

The couple’s union was witnessed by two important figures in their lives: Edwin’s brother, Walter James Willats, and Nellie’s sister, Amelia Ellen Willats (née High), who was married to Walter. The support of these loved ones made the day even more meaningful, marking not just the joining of two individuals, but also the merging of two families.

In the marriage record, Edwin and Nellie provided the names and occupations of their fathers: Richard Henry Willats, a Surveyor, and James High (also known as William James), a Cabinet Maker. These names served as a reminder of the work and lives of the generations that had come before them, shaping the paths they walked as they stood before the altar on that significant day.

As Edwin and Nellie exchanged vows, it was a moment that reflected the continuity of family, tradition, and love. Their marriage was not only a personal milestone but also another step in the ever-evolving story of the Willats family, one of resilience, connection, and the enduring strength of shared history.

Jumping forward to the year 1901.

Living in London in 1901 would have been an experience rich with contrasts and complexities. At the turn of the 20th century, London was a bustling metropolis, the heart of the British Empire, yet it was a city marked by stark social divisions.

The atmosphere would have been a blend of excitement and apprehension. London was undergoing rapid industrialization and urbanization, which brought both opportunities and challenges. The city pulsed with energy, as people from all walks of life sought to make their mark in this rapidly changing world.

Fashion was a significant aspect of daily life, especially for the upper classes. Women wore long skirts and high-necked blouses, often accessorized with hats and gloves, while men donned suits and top hats. The wealthy displayed their status through luxurious fabrics and intricate designs, while the poor made do with simpler attire.

Gossip was a pervasive force in London society, circulating through the salons of the elite and the crowded streets of the working-class neighborhoods. Scandals involving politicians, celebrities, and royalty captured the public's imagination and fueled endless speculation, including, the most notorious scandals to captivate the public's attention was the "Trial of the Century" involving the prominent socialite and Member of Parliament, Sir Roger Casement. Casement, known for his distinguished career as a diplomat and humanitarian, found himself embroiled in a scandalous affair that would tarnish his reputation forever.

The scandal erupted when private letters penned by Casement were leaked to the press. These letters revealed intimate details of Casement's homosexual encounters during his travels in Africa and South America. At a time when homosexuality was not only socially taboo but also illegal, the revelation of Casement's private affairs sent shockwaves through London's high society and political circles.

As the scandal unfolded, Casement faced intense public scrutiny and condemnation. His once-impeccable reputation was shattered, and he found himself ostracized by former friends and colleagues. The scandal also had far-reaching implications for Casement's political career, as it called into question his fitness to serve as a Member of Parliament and cast doubt on his ability to continue his diplomatic work.

In 1911, Casement's downfall reached its climax when he was arrested and charged with treason for his involvement in Irish nationalist activities. Despite his efforts to defend himself in court, including highlighting his past service to the British Empire, the scandal of his private life loomed large over the proceedings. Casement was ultimately convicted and sentenced to death by hanging.

The scandal surrounding Sir Roger Casement remains a poignant reminder of the societal attitudes towards homosexuality in the early 20th century, as well as the devastating consequences that could result from the exposure of one's private life in a highly judgmental and unforgiving society.

Transportation in London was undergoing a revolution with the rise of electric trams and the underground railway system. Horse-drawn carriages still plied the streets alongside early motorcars, creating a chaotic mix of traffic.

Sanitary conditions in London were a major concern, particularly in the crowded slums where disease and squalor were rampant. The city struggled to provide adequate sanitation and clean water to its burgeoning population, leading to outbreaks of cholera and other infectious diseases.

Heating and lighting in the early 1900s relied heavily on coal, which filled the air with thick clouds of smoke and soot. Gas lamps illuminated the streets at night, casting an eerie glow over the cityscape.

The aroma of London in 1901 would have been a curious blend of industrial fumes, horse manure, and the smoky tang of coal fires. Despite efforts to improve air quality, pollution was a persistent problem in the city.

The monarchy held a position of immense influence in London society, with Queen Victoria reigning over the empire for much of the 19th century. However, her death in 1901 marked the end of an era, and the city was in mourning as her son, Edward VII, ascended to the throne.

Parliament was the seat of power in the United Kingdom, where debates raged over issues of imperialism, suffrage, and social reform. The early 1900s saw the emergence of the Labour Party as a political force, advocating for the rights of the working class.

The Prime Minister in 1901 was Robert Gascoyne-Cecil, the Marquess of Salisbury, a conservative statesman who served three terms in office during the late Victorian era.

London was a city of extremes when it came to wealth and poverty. The affluent elite lived in opulent mansions in fashionable neighborhoods like Mayfair and Kensington, while the less fortunate crowded into cramped tenements in the East End.

Healthcare in London was a patchwork of public hospitals, charitable clinics, and private doctors' practices. Access to medical care varied widely depending on one's social status and financial means.

Work was central to life in London, with millions of people employed in factories, shops, offices, and domestic service. The working day was long and arduous for many, especially those laboring in the city's burgeoning industries.

Important historical events in London in 1901 included the passing of the Aliens Act restricting immigration, and the continuation of the Boer War in South Africa and the death of Queen Victoria.

Queen Victoria, one of the longest-reigning monarchs in British history, passed away on January 22, 1901, at the age of 81. Her death marked the end of the Victorian era.

Victoria's declining health had been evident in the years leading up to her death. She had experienced several bouts of illness, including rheumatism and declining eyesight, and had been increasingly reliant on a wheelchair. However, her death still came as a shock to the nation, as she had been a prominent figure for over six decades.

Upon her passing, a period of mourning swept across the British Empire. Flags were flown at half-mast, and many businesses closed as a sign of respect. People gathered outside Buckingham Palace to pay their respects and express their grief.

Victoria's funeral, held on February 2, 1901, was a grand and solemn affair. It took place at St. George's Chapel in Windsor Castle, where she was interred beside her beloved husband, Prince Albert, who had died in 1861. The funeral procession was a somber spectacle, with military bands playing funeral dirges and dignitaries from around the world in attendance.

The funeral procession made its way through the streets of London, lined with crowds of mourners paying their last respects to their queen. The procession included members of the royal family, heads of state, and representatives from across the British Empire.

Following the funeral, Victoria was laid to rest in the Royal Mausoleum at Frogmore, on the grounds of Windsor Castle. Her death marked the end of an era and ushered in a period of transition for Britain and its empire. Despite her passing, Queen Victoria's legacy continued to shape the course of history, leaving an indelible mark on the Victorian era and beyond.

These events shaped the political, social, and cultural landscape of the city at the dawn of a new century.

More important to genealogists and family history enthusiasts, 1901 was the year of the census.

On the eve of the census, Sunday 31st March 1901, Frederick found himself at the threshold of Number 91, High Street, Croydon, Surrey. Beneath the golden glow of gaslight spilling into the cobbled street, he entered the home of Widow Emma Beach, a publican whose life was possibly as vibrant as the inn she tended. The air inside carried the warmth of bustling companionship, the aroma of polished wood and lingering laughter hinting at stories shared within these walls.

The other occupants were Emmas daughter Maude M Beach, her Sister Mary Ann Baker, her aunt Eliza Fry

The rhythms of their days were supported by two loyal servants: John Brickman, the head barman whose steady hand would have kept the establishment running smoothly, and Henry Eteson, the under barman.

But there was something more profound at play this evening, a convergence of fates hidden beneath the ordinary moments of beer and conversation. Frederick could not have known it then, but his visit to Number 91 marked the beginning of a journey that would alter the course of his life. In the warmth of that household, amidst the shared stories and familial bonds, Frederick’s future was being shaped in ways he couldn’t yet comprehend.

The lives within Number 91 carried a certain magic, their interconnectedness weaving a tapestry of hope and destiny. The widow, her family, and even the two steadfast barmen held threads that would tie Frederick to a path he might never have imagined. What might have seemed a routine stay became a pivotal moment, a mysterious turning point in a life poised for change.

High Street in Croydon, Surrey, England, has a rich history that reflects the town's development over the centuries. Originally a market town, Croydon expanded significantly during the 19th century with the advent of the railway, transforming High Street into a bustling commercial hub. The street became lined with a variety of shops, public houses, and civic buildings, serving as a focal point for the local community.

One notable establishment on High Street was Allders department store, founded in 1862 by Joshua Allder. Although not located at number 91, Allders became a significant landmark in Croydon, contributing to the town's commercial prominence.

Regarding number 91 High Street, it's important to note that there are multiple High Streets in the Greater London area, each with their own numbering. For instance, 91 High Street in St Mary Cray, Bromley, is a Grade II listed building, possibly dating back to the 16th century. This timber-framed structure has undergone various alterations over the years and has been recognized for its architectural significance.

However, specific information about 91 High Street in Croydon, including its history and any notable families associated with it, is not readily available. This lack of detailed records could be due to various factors, such as changes in property numbering, redevelopment over time, or the absence of significant historical events linked to that particular address.

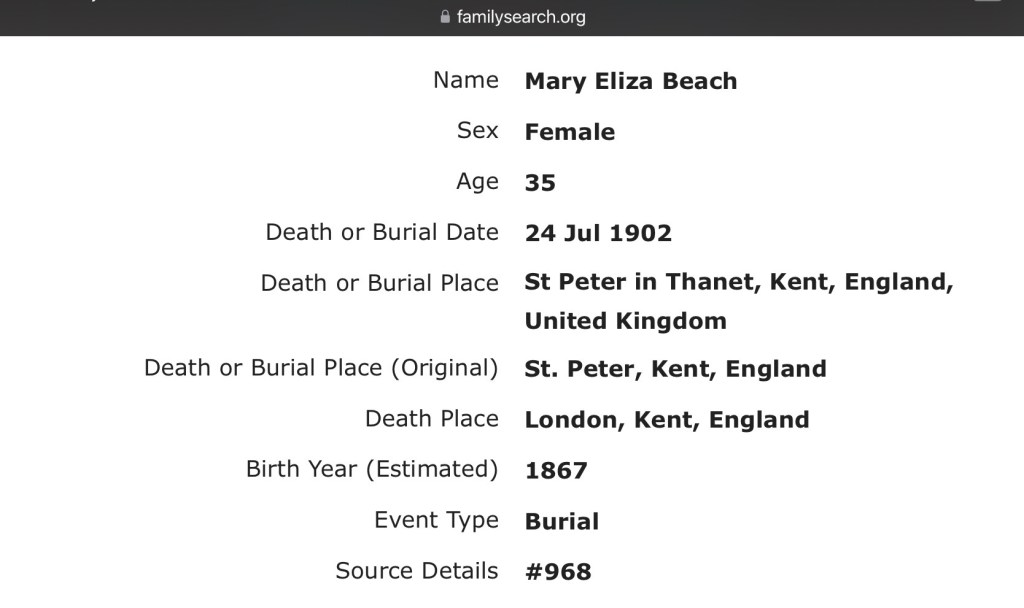

The following year brought deep sorrow to the Willats family, a sorrow that would cast a long shadow over their hearts. On a somber Monday, the 21st of July, 1902, Frederick’s beloved sister, Eliza Mary Beach (née Willats), passed away at Beach Court, Upper Deal, in Eastry, Kent. She was just 35 years old, a life cut tragically short, leaving behind a void that could never truly be filled.

Eliza’s final days were marked by a struggle with pneumonia and exhaustion, a cruel combination that stole her vitality and left her family reeling in helpless grief. At her side in those heartbreaking moments was her devoted sister, Edith Cameron Charlton (née Willats). Edith’s steadfast presence was both a comfort and a testament to the strength of the bond between siblings. It was Edith who, with remarkable courage and composure, registered Eliza’s death on the very day she passed, ensuring that her sister’s final chapter was recorded with love and dignity.

Eliza’s death certificate bore the name Mary Eliza Beach, acknowledging the life she built with her husband, Benjamin Beach, who was listed as a man of independent means. Yet the formality of the words could not capture the depth of his loss, nor the aching absence felt by those who loved her.

This tragedy was not merely the loss of a sister, a wife, or a daughter, it was the loss of a vibrant soul, a part of their shared story now silenced. For Frederick, Edith, Benjamin and all who cherished Eliza, her memory would linger, wrapped in both the pain of her passing and the tenderness of the moments they shared. Her life, though far too brief, left an indelible mark, a legacy of love and connection that no loss could diminish.

On Thursday, July 24th, 1902, Frederick’s sister, Eliza Mary Beach (née Willats), was laid to rest at Saint Peter’s Churchyard, Saint Peter’s Church, Thanet, Kent, England. This marked the end of a chapter in the Willats family history, as they mourned the loss of a beloved sister, daughter, and wife.

Eliza Mary’s passing was a sorrowful moment for the family, one that reflected the inevitable cycle of life. As the family gathered to bid her farewell, it must have been a time of deep reflection and sadness. For those who knew her, her memory lived on in the love she shared and the life she led, her name etched into the history of the Willats family.

The peaceful setting of Saint Peter’s Churchyard, with its centuries-old gravestones, was a fitting final resting place, a place where Eliza Mary, like so many before her, would be remembered by those who loved her. Her legacy, as part of the Willats family, would continue to be passed down through the generations, carried in the hearts of those who cherished her.

St Peter's Church, located in the village of St Peter's within Broadstairs, Kent, England, is a historic parish church with origins dating back to at least 1128. The current structure features a late Norman nave and an Early English chancel, reflecting architectural developments over the centuries. The 15th-century additions include a battlemented tower and a south porch, both exemplifying the Perpendicular style of that era.

The church's tower has played a significant role in local history. Once the highest point in Thanet, it served as a naval signaling station during the Napoleonic Wars and retains the privilege of flying the White Ensign, a naval flag. A notable feature of the tower is a large crack on its west side, which local tradition attributes to an earthquake, though specific details about this event are scarce.

The surrounding churchyard is notable for its size and historical significance. It is considered one of the largest "closed churchyards" in England, meaning it is no longer used for new burials. Maintained by a dedicated group of volunteers known as the "Friends of the Graveyard," the churchyard is the subject of guided tours that highlight its rich history and the stories of those interred there.

St Peter's Church remains an active parish within the Church of England, continuing its mission to serve the local community and preserve its historical legacy.

Thankfully, the year following Eliza Mary’s passing brought some much-needed joy to the Willats family. On Saturday, April 4th, 1903, Frederick’s sister, 28-year-old May Claretta Willats, found happiness in love as she married 20-year-old George Frederick Champion, an architectural florist, at St. John’s Church, Highbury Vale, Islington, London.

This wedding marked the beginning of a new chapter for May, a moment of celebration after a year of mourning. May gave her residence as 21 Montague Road, while George’s was listed as 194 Green Lands. As they stood together at the altar, they shared not only their vows but also the connection between their families. They noted their fathers’ names and occupations: George Frederick Champion, an architectural florist, and Richard Henry Willats, an Estate Agent, two men who had shaped their respective families and provided a foundation for the life they were beginning together.

Their witnesses included George Frederick Champion himself and May’s niece, Amina Eliza Catherine Charlton, adding a sense of family continuity and love to the occasion. The presence of loved ones, both young and old, must have made the day all the more special for May and George, as they began their new life together.

For the Willats family, this wedding was a bright moment of renewal, proof that after hardship, there could still be moments of happiness and love. It was a reminder that life moves forward, and with it, new bonds are formed, continuing the family’s story in meaningful and beautiful ways.

Frederick’s own love story likely began in 1901, when Frederick Howard Willats, a young bachelor and surveyor, stayed at Number 91, High Street, Croydon, Surrey, the home of Maud May Beach’s mother, the widowed Emma Beach, a publican. It was there, amidst the warmth of a family home, that Frederick and Maud might have first crossed paths, their connection blossoming in ways that neither could have foreseen.

Just two years later, their bond culminated in a joyous union.

On a golden Saturday, September 19, 1903, 26-year-old Frederick married his beloved, 24-year-old Maud, at the picturesque St. John’s Church in Highbury Vale, Islington, London. The church must have glowed with their happiness as they pledged their lives to one another.

Frederick listed his residence as 27 Kings Road, while Maud, radiant in her role as a bride, gave hers as 16 Orchard Road, St. Margarets-on-Thames. As they stood before the altar, they honored their fathers, Richard Henry Willats, an estate agent, and Walter Beach, a gentleman whose memory lived on despite his passing.

The ceremony was graced by the presence of loved ones, including Frederick’s brother, Persey Sidney Willats, and his niece, Amina Eliza Catherine Charlton, who stood as witnesses to the beginning of their shared life. It was a day steeped in love, family, and the promise of a beautiful future together.

The first church of Saint John, Highbury Vale was a temporary iron church erected by 1877. A permanent church was completed in 1881 and consecrated on 30 July 1881. A district was assigned to it out of the parish of Christ Church Islington. The church was declared redundant on 1 January 1979 and the parish was united with Christ Church, Highbury Grove, which became known as Christ Church with Saint John; Christ Church being the parish church of the united parish. Saint John, Highbury Vale, was in Park Place which is now called Conewood Street. The church changed its name to ST. JOHN, Highbury Park. I believe it is now a small, one form entry Church of England primary school. Unfortunately I am having trouble locating a photo of the church, in all its glory before it became a school.

In 1903, weddings in England were steeped in tradition and societal norms, reflecting the values and expectations of the time. Preparation for a wedding typically began months in advance, with families and sometimes even communities involved in the planning process.

For the bride, the wedding gown was a significant focus. It was usually made of luxurious fabrics like satin, silk, or lace, often adorned with intricate embroidery or beadwork. The style was typically conservative, with high necklines, long sleeves, and full skirts, reflecting the modesty and decorum of the era. Veils were also commonly worn, symbolizing purity and modesty.

Traditions surrounding weddings in 1903 were deeply rooted in superstition and symbolism. For instance, the bride often carried a bouquet of flowers, not only for their beauty but also for their supposed ability to ward off evil spirits. Additionally, wearing "something old, something new, something borrowed, something blue" was believed to bring good luck to the bride.

The wedding ceremony itself was a formal affair, usually held in a church and officiated by a clergy member. Vows were exchanged, rings were presented, and prayers were offered, all amidst the solemnity of the occasion. After the ceremony, the newlyweds would often be showered with rice or confetti as they made their exit, symbolizing fertility and prosperity.

Following the ceremony, the wedding breakfast was a customary part of the celebration. This was typically a lavish affair, featuring an elaborate meal served to the newlyweds and their guests. Traditional dishes such as roast beef, chicken, or lamb might be served, accompanied by vegetables, bread, and wine.

Celebrating the newlyweds was an integral part of the wedding festivities. Depending on the social standing of the families involved, celebrations could range from intimate gatherings to grand receptions with music, dancing, and entertainment. Toasts and speeches were common, expressing well-wishes for the couple's future happiness and prosperity.

As for the honeymoon, it was becoming increasingly popular for newlyweds to take a trip together after the wedding festivities. Destinations varied, but romantic locales such as the countryside or seaside resorts were common choices. The honeymoon provided the couple with a chance to relax and enjoy each other's company before beginning their married life together.

As we draw the curtains on this inaugural installment of our exploration into the life of Frederick Howard Willats, we find ourselves enveloped in a tapestry woven with the threads of his earliest years. From the moment of his birth in 1877 to the sacred union of marriage in 1903, we have traced Frederick's journey through the lens of meticulous documentation and historical insight.

In these formative years, Frederick emerged not merely as a figure in the annals of time, but as a beacon of our dna. Through the pages of birth certificates, marriage records, and census records, we have glimpsed the contours of his character, the trials that tested his mettle, the triumphs that kindled his resolve, and the quiet moments of reflection that shaped his path.

As we bid adieu to this chapter of Frederick's life, we do so with a sense of reverence for the legacy he has left behind. His story serves not only as a testament to the indomitable human spirit but also as a reminder of the profound significance of our shared journey through time.

Please pop back and join me as we continue to unravel the tapestry of Frederick Howard Willats' life, navigating the ebbs and flows of history with a steadfast commitment to uncovering the truths that lie beneath. Until then, let us carry forward the lessons gleaned from his early years, the echoes of resilience, the melodies of hope, and the enduring promise of a life lived with purpose and meaning.

Until next time,

Toodle Pip,

Yours,

Lainey.

🦋🦋🦋