Welcome to The Life of Margarita Carroll, a blog dedicated to unraveling the story of an extraordinary woman whose journey spanned two continents, and whose legacy continues to inspire her descendants. Margarita, also known as Margaret, was born in 1824 in Ireland to Daniel Carroll and an as-yet unidentified mother. Her story, like so many Irish immigrants of the 19th century, is a testament to resilience, courage, and the deep connections forged through family and community.

Researching Margarita’s life has been as challenging as it has been rewarding. The journey has been fraught with the unique difficulties faced by those delving into Irish genealogy. A devastating fire at the Public Record Office in 1922 obliterated countless records, erasing vital links in the chains of countless family histories. Census returns, church registers, and other invaluable documents were reduced to ash, leaving gaps that have frustrated generations of researchers.

But for those of us who persist, piecing together the fragments that remain becomes a labor of love. Through surviving parish records, emigration logs, and oral family traditions passed down like cherished heirlooms, Margarita’s story has slowly emerged, a patchwork quilt stitched together with determination and care.

This blog is not just a chronicle of Margarita’s life but a celebration of the families she helped build and the challenges she overcame. It is a tribute to all those who, like her, carried their heritage across oceans and through hardships, shaping the generations to come.

Join me as we step back into the 19th century, exploring the life of Margarita Carroll through the lens of history, faith, and family. Together, we will uncover the story of a woman whose legacy is still being felt today, more than a century after her passing. So without further ado, I give you,

The Life Of Margarita Carroll,

1824-1909,

Through Documentation.

Welcome back with me to Ireland in the year 1824, a world both distant and familiar, a land of deep contradictions, where beauty and hardship intertwined to shape lives like that of my ancestor, Margarita Carroll.

Born that year to Daniel Carroll and an as-yet-unidentified mother, Margarita entered a world under the rule of King George IV and the governance of Robert Jenkinson, the 2nd Earl of Liverpool. The Irish countryside was alive with whispers of change, but also weighed down by the heavy hand of British law and the shadow of poverty. The newly established Ordnance Survey of Ireland was beginning to map the country with precision, but for most Irish families, life was anything but orderly.

In 1824, Ireland was a land of stark divides. The wealthy elite lived in Georgian mansions, with coal-fueled fireplaces and decorative clothing made of fine silks and wools. Meanwhile, the majority, farmers, laborers, and the impoverished, relied on turf (peat) to heat one-room cottages that often lacked even basic sanitation. Plumbing, as we know it, didn’t exist. A bucket served as a toilet for the poorest, and water had to be fetched from wells or streams, a backbreaking task that fell disproportionately on women and children.

Food, for many, was a daily struggle. Potatoes formed the staple diet for the working class, often supplemented by milk when available. The richer households enjoyed more varied fare, including meats, imported fruits, and fine wines. In Margarita’s world, though, hunger was a constant companion, especially during lean seasons.

Education was another marker of privilege. Formal schooling was a luxury for the wealthy, with children taught at home or in private schools by governesses or tutors. For the poor, hedge schools, illegal, makeshift classrooms held in barns or even open fields, provided a rare chance at literacy, often taught in secret to avoid British oversight. It’s unclear what, if any, formal education Margarita received, but her resilience suggests a schooling of necessity and hard work.

The streets of Irish towns bustled with gossip and the latest news, much of it exchanged in pubs or markets. Thomas Crofton Croker’s Researches in the South of Ireland was published that year, capturing stories and folklore that still held sway over the imaginations of a people struggling to hold on to their culture. At the same time, the British Vagrancy Act criminalized begging, adding a cruel edge to the plight of the poor who had no choice but to rely on charity.

Fashion and entertainment offered little comfort to those like Margarita’s family. While the wealthy attended balls and wore empire-line dresses adorned with lace, the poor made do with homespun wool and simple linen, clothing that prioritized function over form. Entertainment for the working class might include traditional music, storytelling, or gatherings at local fairs, where the spirit of the community momentarily lifted the weight of hardship.

Historically, 1824 was a year of progress elsewhere—the National Gallery in London was founded, and scientific minds were beginning to describe creatures as strange as dinosaurs. But for Margarita’s Ireland, survival was often the only priority. The effects of the Penal Laws, though somewhat relaxed, still lingered, and Catholic families like the Carrolls faced discrimination that limited their opportunities and freedoms.

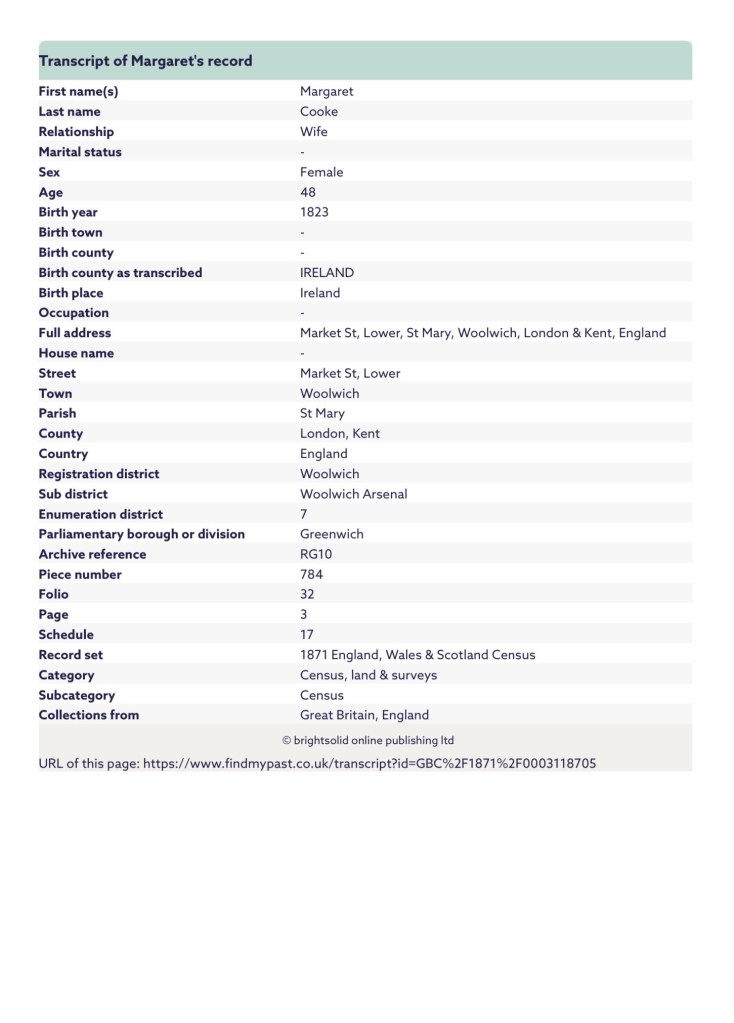

And so begins the story of my 4th great grandaunt, Margarita Carroll, a woman whose life spanned decades of profound change and whose strength echoes through generations. Margarita was born around the year 1824 in Ireland, a detail I’ve pieced together through a mosaic of census records, family lore, and the faint echoes of history. Her exact birth year shifts slightly depending on the source: the 1861 census points to 1824, while others, from 1871 to 1891, suggest 1823 or even as early as 1819. The absence of the 1841, 1851, and 1901 censuses leaves gaps in her story, gaps that whisper of all the lives lived between the pages of history.

What I do know is that Margarita was born into a world vastly different from ours, into an Ireland both heartbreakingly beautiful and deeply scarred. She was the daughter of Daniel Carroll, but her mother remains a mystery, her name lost to time and the limitations of records.

The Ireland Margarita entered in 1824 was a land of profound contrasts. It was a time when wealth and privilege were the lot of a few, while poverty bound the lives of so many, likely including her family. The Carrolls, like most Irish families of the time, may have lived in a small cottage warmed by turf fires, where life was as much about survival as it was about community. Food was simple and often scarce, a diet of potatoes, milk, and whatever else could be grown or traded.

I think about Margarita as a young girl, perhaps fetching water from a well, her hands chilled by the icy bucket handle, or helping with chores around the home. Did she have time for play? Did she sing the songs passed down through generations or listen wide-eyed to stories of heroes and fairies told by the hearth? Was she lucky enough to attend a hedge school, learning letters and numbers under the watchful eye of a teacher who risked their safety to educate?

By the time she reached adulthood, the echoes of these early days must have stayed with her, shaping the woman she became. The censuses, though sparse in detail, reveal Margarita’s resilience and endurance. They tell of a life of movement, of adapting to new circumstances while holding fast to her Irish identity. Like so many of her time, she lived through an Ireland ravaged by famine, repression, and emigration. If she left Ireland, it was likely with a mixture of hope and heartache, carrying memories of green fields and a culture rich in song, faith, and tradition.

Each piece of her story that I uncover feels like a gift. Margarita’s life may have been ordinary by the standards of history, but to me, it is extraordinary. She lived through times that shaped the world, through years that tested the spirit and called for unimaginable perseverance. In her, I see the strength of a woman who lived not for grand gestures but for the quiet heroism of enduring, of raising her family, and of contributing to the legacy that brought me here, searching for her.

Tracing Margarita’s life has been a labor of love. The challenges of Irish genealogy, the loss of countless records in the 1922 fire, the gaps in censuses, and the limits of what was recorded for people of modest means, are daunting. But with every piece of her story I uncover, I feel closer to her. It’s as though the distance between us shrinks, as if her story is waiting to be remembered, waiting to remind me of the strength that runs in our family’s blood.

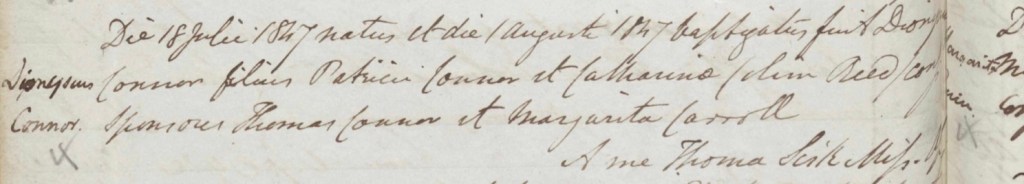

The earliest official record I have found for Margarita, also known as Margaret, is one that gives a small but significant glimpse into her life. On Sunday, August 1, 1847, she stood as a godparent alongside her brother-in-law, Thomas, at the baptism of her nephew, Dennis Connor. The ceremony took place at St. Mary’s Roman Catholic Church in Chelsea, Middlesex, England, a moment of faith and family connection preserved through time.

Interestingly, Dennis was baptized under the name Dionysius Connor, the Latinized version of his name, reflecting the traditions of the Church at the time. This record not only confirms Margarita’s presence in England by 1847 but also highlights the close ties she shared with her family and the role she played in their lives. It’s a small but meaningful detail that begins to weave together the story of her journey and the bonds that sustained her.

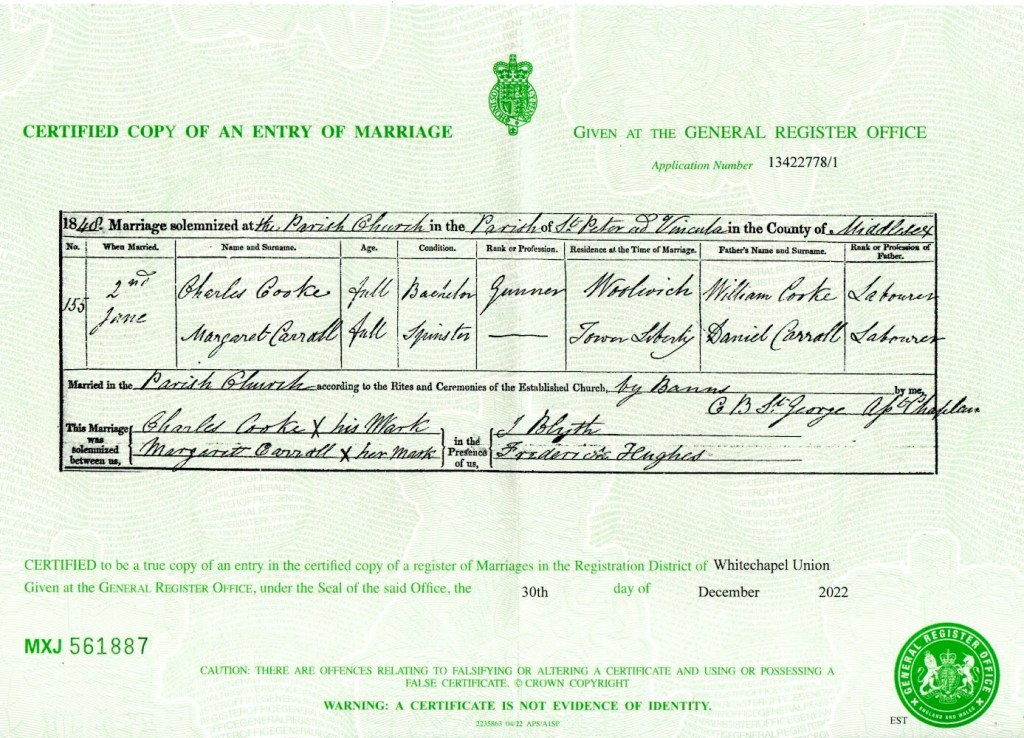

On June 2, 1848, Margarita Carroll, recorded as Margaret, took a significant step in her life when she married Charles Cooke (also recorded as Cook), a gunner in the British Army. The ceremony took place at The Chapel of St Peter ad Vincula in Whitechapel, Middlesex, England—a place steeped in history and solemnity, tucked within the ancient walls of the Tower of London.

Margarita and Charles were both listed as being of full age, signaling that they had reached the legal age to marry without additional consent. At the time of their marriage, Margarita was residing in Town Liberty, while Charles was stationed in Woolwich, reflecting his military life.

Their fathers were named on the marriage record: Daniel Carroll, a laborer, and William Cooke, also a laborer. This simple detail anchors Margarita’s roots firmly in her family’s working-class heritage, a legacy shaped by hard work and resilience.

The couple, like many of their era, “made their mark” on the marriage certificate, indicating that neither could write their names—a poignant reminder of the challenges faced by those of humble origins in a time when education was often a privilege, not a guarantee.

Their witnesses, J. Blyth and Frederick Hughes, offer a tantalizing glimpse into the community surrounding Margarita and Charles, though their connection to the couple remains a mystery.

This moment, captured in the pages of history, is more than a marriage record—it is a testament to Margarita’s journey, marking a new chapter in her life as she stepped into her role as wife and partner. It reflects the blending of lives, traditions, and the hope for a shared future, all framed against the backdrop of mid-19th century England.

As the world ushered in the year 1851, a time of grand achievements and significant events, Margarita and Charles Cook experienced their own momentous occasion: the birth of their daughter, Ellen Jane Cook. Amid the sweeping currents of history, the arrival of a new life marked a deeply personal chapter for the couple.

The year began with Queen Victoria firmly established on the throne, embodying an era of progress and expansion. Lord John Russell led the government, and the grand spectacle of the Great Exhibition at the Crystal Palace in Hyde Park showcased the ingenuity and industry of nations under the Queen’s patronage. Elsewhere, new beginnings were unfolding: Jacob's brand, known today for its iconic biscuits, was founded, and in Ireland, the Poor Relief Act established dispensaries to aid the impoverished.

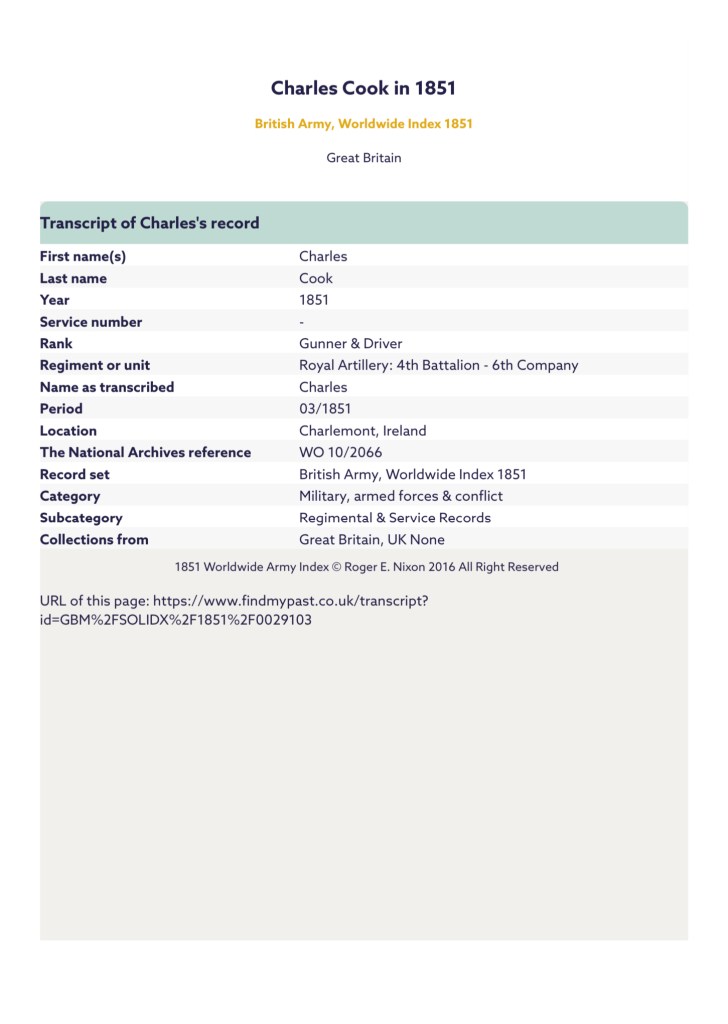

For Margarita and Charles, 1851 brought their own monumental change. Their daughter, Ellen Jane Cook, was born around this time in Charlemont, Armagh, Northern Ireland, where Charles was stationed with the 4th Battalion of the Royal Artillery. The battalion was based at Charlemont Fort, a military stronghold steeped in history, standing along the River Blackwater in County Armagh.

Ellen’s birth is recorded as occurring around March 1851, aligning with her listed birth year in the 1861 census. While great exhibitions and railway arches captured the imagination of the public that year, Margarita and Charles were likely consumed by the more immediate and intimate task of welcoming and caring for their firstborn.

In the shadow of Charlemont Fort, with its sturdy walls and storied past, Ellen’s cries would have joined the hum of military life. Margarita, far from her birthplace in Ireland, faced the challenges of motherhood with the strength and determination that had carried her this far. Charles, a gunner in the Royal Artillery, balanced his duties as a soldier with his responsibilities as a new father.

The year 1851, full of grandeur and history for the world at large, became an indelible part of Margarita and Charles’s personal story. In Ellen, they had not only a daughter but the promise of the next generation, a thread of hope and continuity woven into their lives amidst a world that seemed to be constantly shifting.

On Sunday, March 30, 1851, the United Kingdom Census was taken, a groundbreaking effort in record-keeping that provided, for the first time, detailed information about the lives of those it documented. It recorded ages, dates of birth, occupations, and marital status, offering a vivid snapshot of a rapidly changing society. At this time, the population of the United Kingdom had reached 21 million, with 6.3 million people living in cities of 20,000 or more across England and Wales. These growing urban centers accounted for 35% of the English population.

Uniquely, the 1851 Census also measured attendance at religious services, providing insight into the spiritual lives of the population. But the census also revealed a darker reality: in Ireland, the devastating impact of the Great Famine was laid bare. The population had fallen to 6,575,000, a staggering drop of 1,600,000 in just a decade. This census was also the first to note the use of the Irish language, a bittersweet recognition of a culture struggling to endure amid unimaginable loss. Tragically, much of the Irish 1851 Census has since been lost, leaving countless stories like Margarita’s in fragments.

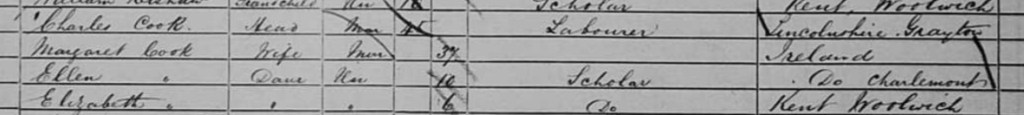

However, from surviving records, we know that Margarita, her husband Charles, and their infant daughter Ellen were at a military base in Charlemont, County Armagh, Ireland, during this pivotal year. Charles was serving as a gunner in the 4th Battalion of the Royal Artillery, stationed at Charlemont Fort. This historic garrison stood as a stronghold along the River Blackwater, a symbol of military presence in a land still grappling with the aftershocks of famine and emigration.

As a military family, Margarita, Charles, and Ellen would have lived amidst the structured, regimented life of the fort. For Margarita, life on a base far from the bustling cities and growing industrial centers of England might have been isolating, yet it was also likely a place of community, shared experiences, and the quiet rhythms of military life.

While the world around them was recorded in unprecedented detail, Margarita and her family’s presence at Charlemont Fort remains a rare and precious piece of their story. It reminds us of their resilience and adaptability, living through a time when history itself seemed to be shifting, both for their family and the world at large.

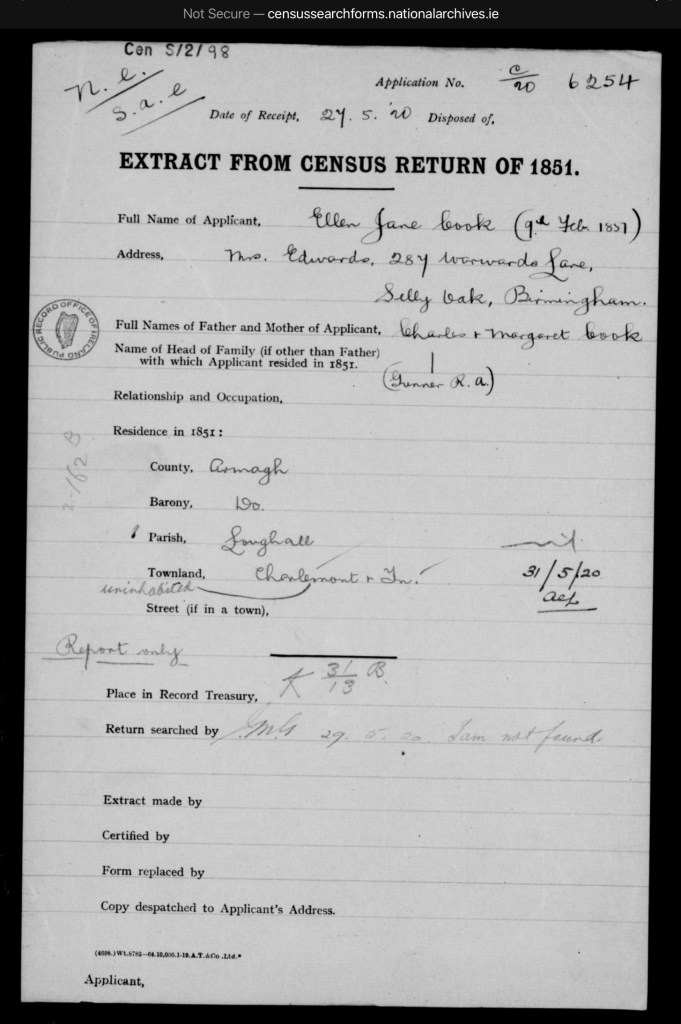

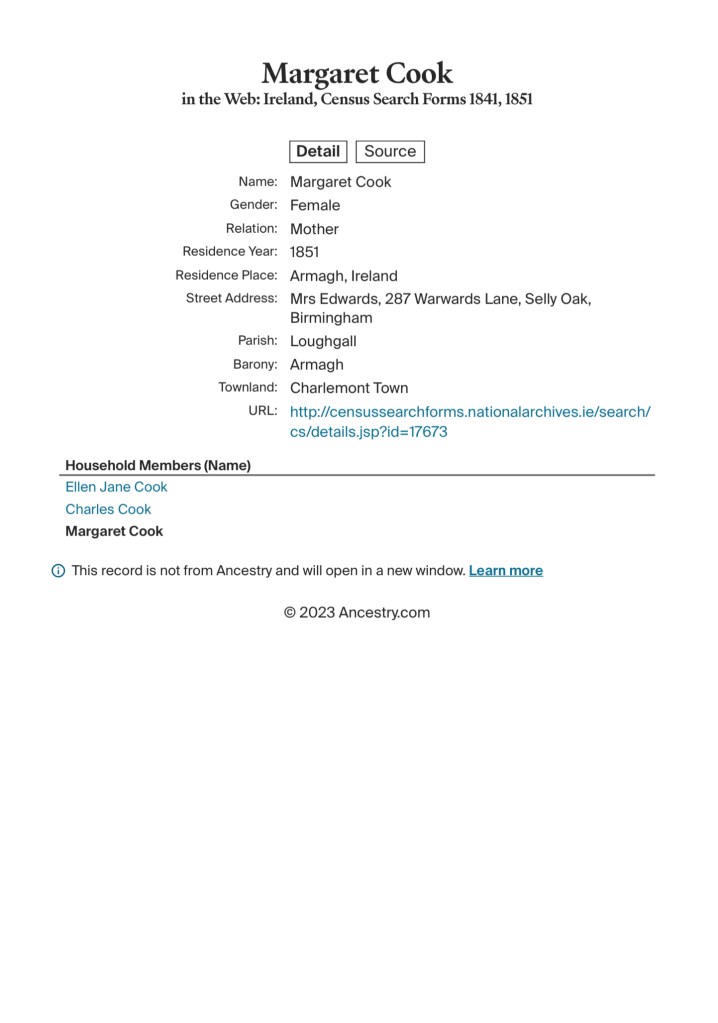

After much searching, I finally uncovered an incredible find: Margarita, Charles, and their daughter Ellen Jane Cook appear in an extract from the 1851 Ireland Census. This rare document offers a fleeting but precious glimpse into their lives on March 30, 1851.

The record places the family in Charlemont Town, Loughgall, County Armagh, Northern Ireland. Interestingly, they were residing in the household of Mrs. Edwards, of 287 Warwards Lane, Selly Oak, Birmingham. While the circumstances connecting them to Mrs. Edwards remain unclear, her name on the record hints at an extended network of connections or perhaps a family or military-related arrangement.

On this census extract, Margarita was listed as Margaret, a name she seemed to use interchangeably. It is a poignant reminder of how even the smallest variations in names can complicate the process of tracing a family’s history.

This discovery not only anchors the family in Charlemont during this historic moment but also provides a tangible link to their day-to-day lives—a life shared as a military family in a town marked by its military fort and its proximity to the larger stories of mid-19th century Ireland. Each document like this brings Margarita’s story to life in new and unexpected ways, filling in gaps and shining a light on the quiet details of her world.

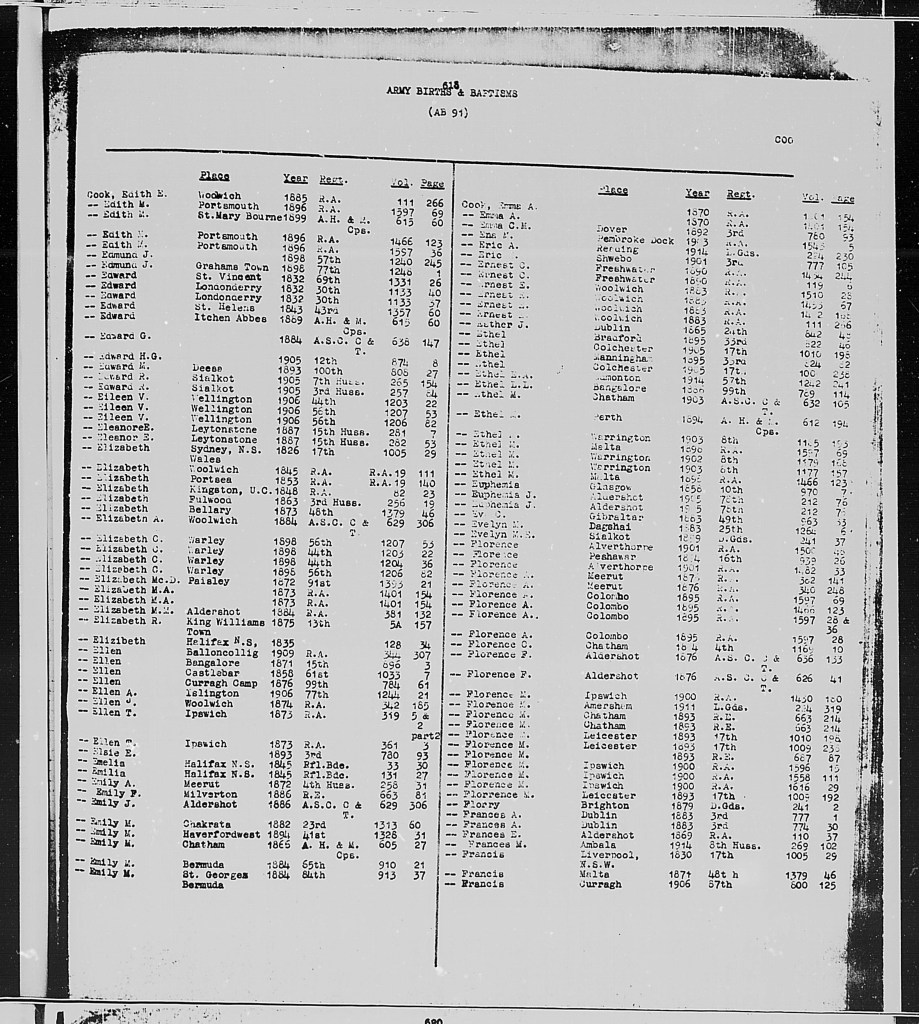

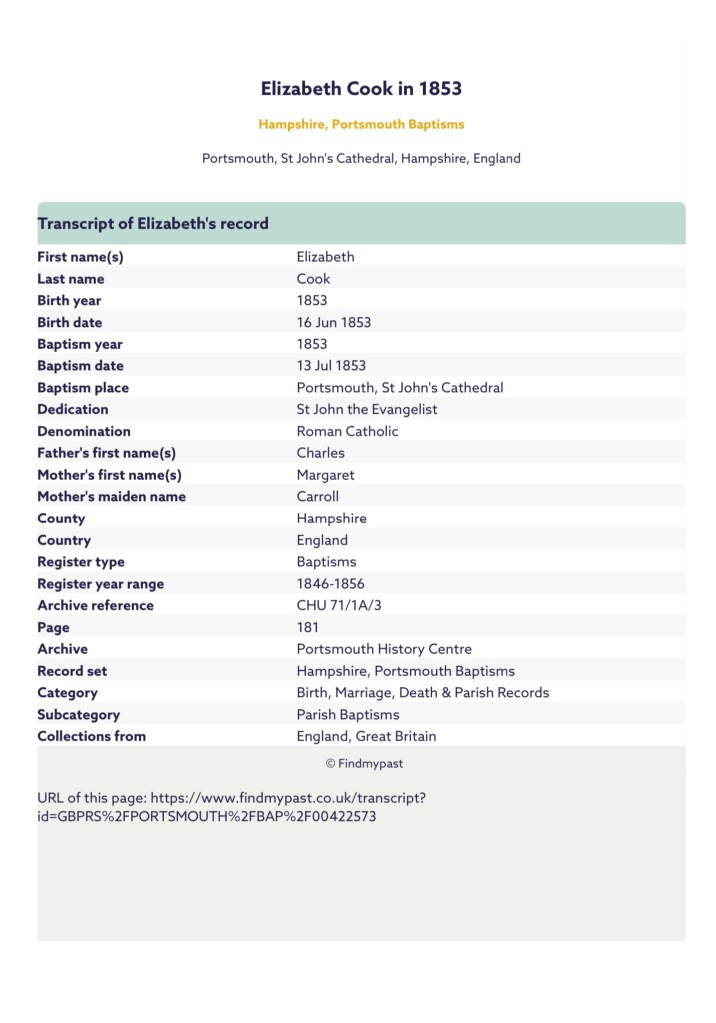

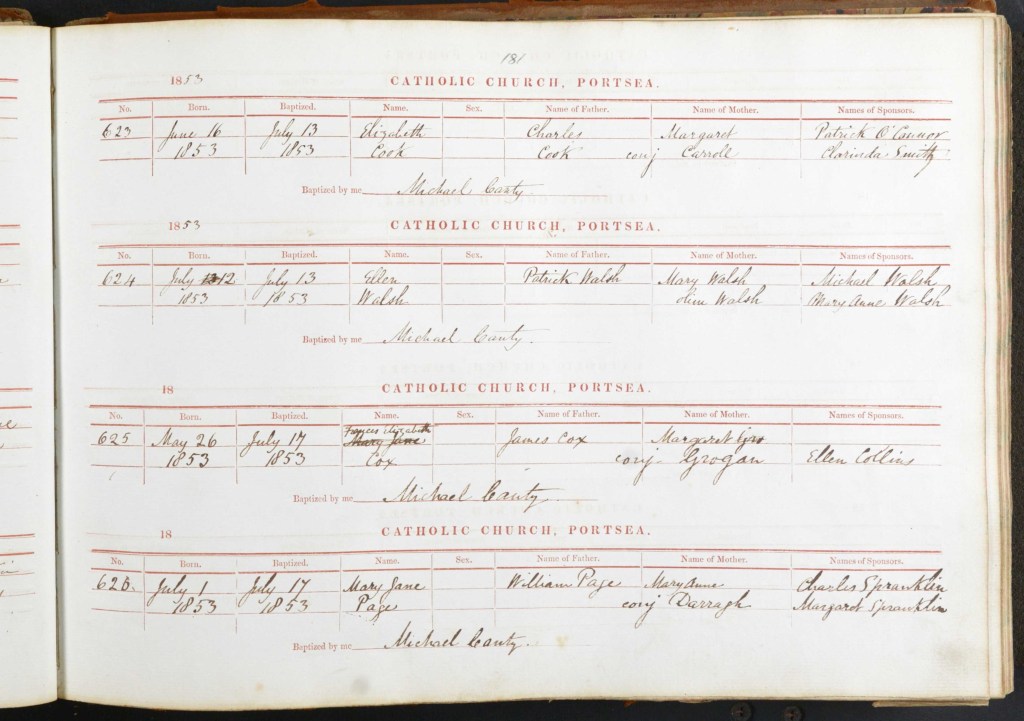

At some point after the 1851 Census, the 4th Battalion of the Royal Artillery appears to have been redeployed, marking another chapter in Margarita and Charles’s journey as a military family. During this time, we believe Margarita and Charles welcomed another daughter, Elizabeth, born on June 16, 1853, in Portsea, Hampshire, England—a location closely tied to military activity and the Royal Navy.

We’ve located Elizabeth’s record in the military birth index, which strongly suggests she is their child. However, until her birth certificate is in hand, I cannot confirm this with absolute certainty. As any family historian will know, obtaining military birth, marriage, and death documentation is an entirely different process from ordering standard civil certificates. It requires navigating additional layers of bureaucracy, often involving long waits and considerable persistence.

Despite the challenges, this discovery feels like an important piece of the puzzle. All signs point to Elizabeth being Margarita and Charles’s daughter, and I hope to soon have her birth certificate to add to our growing archive of family history. Until then, I hold onto the belief that this little girl born in Portsea was part of their story, a testament to the mobility and resilience that defined military family life in the mid-19th century.

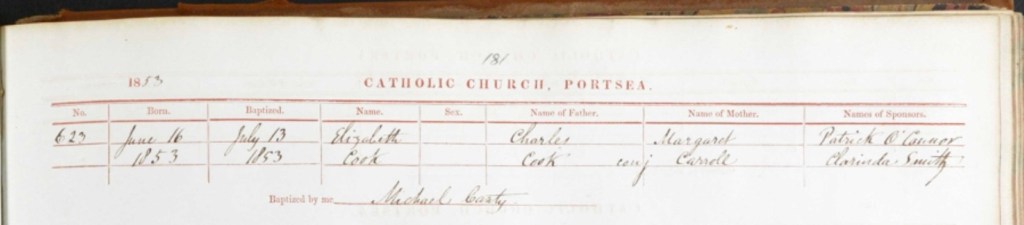

On July 13, 1853, Margarita and Charles took their daughter Elizabeth to be baptized at St. John’s Roman Catholic Cathedral on Bishop Crispian Way in Portsmouth, Hampshire, England. This sacred ceremony, held in the grand setting of the cathedral, was a profound moment of faith and family, marking Elizabeth’s introduction into the Church.

Elizabeth’s godparents were her uncle, Patrick O’Connor, her sister Honora’s husband, and Clarinda Smith. Their presence at the baptism underscores the close-knit bonds of family and friendship that surrounded Margarita and Charles, even amidst the challenges of military life.

This event provides another precious thread in the fabric of Margarita’s story, illuminating not only her devotion to her faith but also the enduring connections that defined her family’s life. Each detail, from the cathedral where Elizabeth was baptized to the chosen godparents, adds richness to the narrative of a family whose lives were deeply rooted in both tradition and adaptability.

The Cathedral Church of St John the Evangelist, commonly known as St John’s Cathedral, is a Roman Catholic cathedral located in Portsmouth, Hampshire, England. It serves as the seat of the Diocese of Portsmouth, and its history is deeply intertwined with the broader Catholic revival in England following the end of the Penal Laws in the early 19th century.

Prior to the 19th century, Roman Catholics in England faced significant restrictions on their worship and freedom due to the Penal Laws, which were established after the English Reformation. However, the Catholic Emancipation Act of 1829 lifted some of these restrictions, allowing Catholics to practice their faith openly and to build places of worship. This change allowed the Catholic community in Portsmouth, which had been growing due to immigration and the influx of Irish Catholics, to consider the construction of a new cathedral.

In 1882, the foundation stone for St John’s Cathedral was laid. The cathedral was designed by architect John Colson in the Gothic Revival style, which sought to revive the grandeur of medieval architecture. The construction was a significant undertaking for the Catholic community in Portsmouth, and the cathedral was built using local stone. Its design features characteristic Gothic elements, including pointed arches, ribbed vaults, and flying buttresses. The spire of the cathedral rises high above the city, making it a prominent feature of the Portsmouth skyline.

St John’s Cathedral was consecrated in 1882 and formally dedicated to St John the Evangelist, one of the twelve apostles of Jesus Christ and the author of the Gospel of John. The cathedral was built not only as a place of worship but as a symbol of the flourishing Catholic community in Portsmouth. Inside, the cathedral is equally remarkable, with its high vaulted ceilings, beautifully decorated chancel, and intricate stained-glass windows. These windows depict scenes from the Bible, with several windows dedicated to the lives of saints. The craftsmanship and artistry within the cathedral are a testament to the church’s commitment to creating a space that would inspire reverence and devotion.

The role of St John’s Cathedral extended far beyond its role as a place of worship. Over the years, it became a focal point for the Catholic community in Portsmouth, hosting significant religious ceremonies such as ordinations, confirmations, and annual masses. As the seat of the Diocese of Portsmouth, the cathedral served as the spiritual center for the faithful in the region, and it became a central location for Catholic life in the city. It also stood as a symbol of the Catholic Church’s resurgence in Britain, following the long history of suppression faced by Catholics in the country.

In the 20th century, the cathedral continued to play a key role in the life of the city and the church. It became a hub of activity, not only for regular Mass services but also for various community events and charitable programs. Its continued importance in the life of the city can be seen in the active role it plays today. St John’s Cathedral remains a place of regular worship and an active site of pilgrimage for Catholics. It also serves as the location for various community services and outreach programs that cater to both the spiritual and practical needs of the local population.

The cathedral has, over time, become not just a place of religious significance but also a landmark of architectural beauty in Portsmouth. Its Gothic Revival design continues to attract visitors, who come not only to worship but to admire the cathedral’s stunning architecture. The cathedral has become an enduring symbol of faith, resilience, and the long history of the Catholic Church in Portsmouth and the UK.

St John’s Cathedral stands as a living testament to the enduring faith of the Catholic community in Portsmouth, offering a glimpse into the spiritual and architectural history of the region. The cathedral, with its intricate design, rich history, and active role in the community, remains an essential landmark in the city and continues to inspire those who visit or worship there.

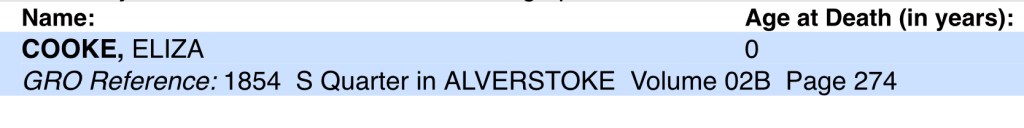

Sadly, it appears that Elizabeth may have passed away before 1855, either in Woolwich or Alverstoke, locations that were significant for Margarita and Charles at the time. There are three possible death records in Woolwich and one in Alverstoke, though, of course, the exact place of her death remains uncertain.

While these possibilities are significant, it’s important to be cautious until we can confirm that Elizabeth is 100% the daughter of Margarita and Charles. Until I have the necessary documentation, whether it be a birth or death certificate, it would be premature to pursue these leads further, especially considering the costs and effort involved in obtaining multiple certificates.

At this stage, I’ll continue to search for more information, piecing together the fragments of Elizabeth’s story as best as I can. It’s an ongoing process, and I’ll be sure to update you as soon as I uncover more details that may bring clarity to this chapter of our family’s history.

COOK, ELIZABETH 1

GRO Reference: 1854 M Quarter in GREENWICH Volume 01D Page 378

COOK, ELIZABETH 1

GRO Reference: 1854 S Quarter in GREENWICH Volume 01D Page 947

COOK, ELIZA 0

GRO Reference: 1854 S Quarter in GREENWICH Volume 01D Page 972

And one for Alverstock.

COOKE, ELIZA 0

GRO Reference: 1854 S Quarter in ALVERSTOKE Volume 02B Page 274

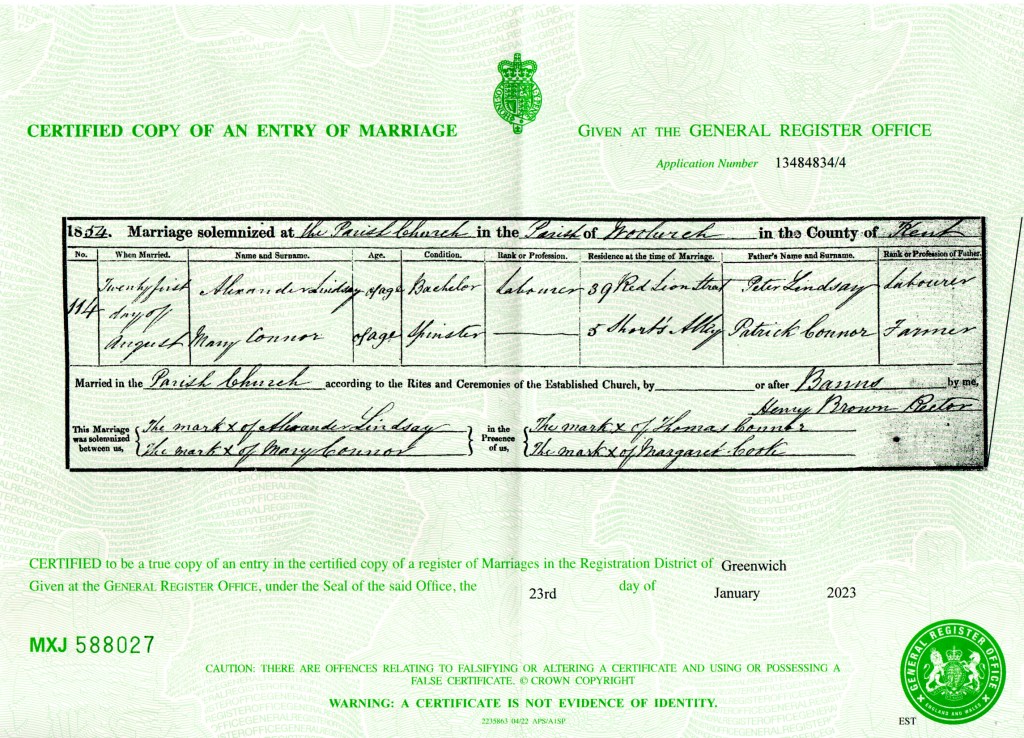

Margarita played an important role in her family’s life, and one of the notable occasions she was part of was the wedding of her sister-in-law, Mary Connor. Mary, a spinster of full age, married bachelor Alexander Lindsay, a full-aged laborer, on Monday, August 21, 1854, at The Parish Church of Woolwich, Woolwich, Kent, England. Both Mary and Alexander made their marks on the marriage certificate, as was common at the time for those who could not write.

The couple provided the names of their fathers as Peter Lindsay, a laborer, and Patrick Connor, a farmer. At the time of their marriage, Mary was residing at 5 Shorts Alley, while Alexander lived at 39 Red Lion Street. The witnesses to the marriage included Margarita (listed as Margaret), who stood by her sister-in-law’s side, and Mary’s brother, Thomas Connor. This occasion further highlights Margarita’s presence at pivotal moments in her family’s life, solidifying her role in the network of relationships that shaped her personal and familial history.

The documentation of this wedding provides another precious thread in the broader story of Margarita’s family, illustrating the interconnectedness of their lives in England during the mid-19th century. The story of Mary Connor’s life, one that I encourage you to explore, offers additional context and helps bring to life the world Margarita inhabited.

You can read all about, Mary Connors life here.

The following year, on January 18, 1855, Margarita gave birth to her daughter Elizabeth Cook in Woolwich, Kent, England. This would have been a significant moment in Margarita’s life as she expanded her family, continuing the journey with her husband, Charles. However, despite the personal importance of this birth, it’s unfortunate that Elizabeth does not appear in the birth index on the General Register Office (GRO) or FreeBMD databases.

This absence could be due to several reasons, such as missing records or variations in how the name was registered. Sometimes, records were incomplete or not recorded properly, especially for children born to military families or in more remote locations. It may also be possible that the birth was not officially registered, a common issue during that time, particularly in certain regions or circumstances.

While the absence of Elizabeth’s name in these records presents a challenge in confirming the details of her birth, it doesn’t diminish the significance of her existence in the family history. I’ll continue to explore other avenues to uncover more information about her birth and confirm her place in Margarita and Charles’s family story.

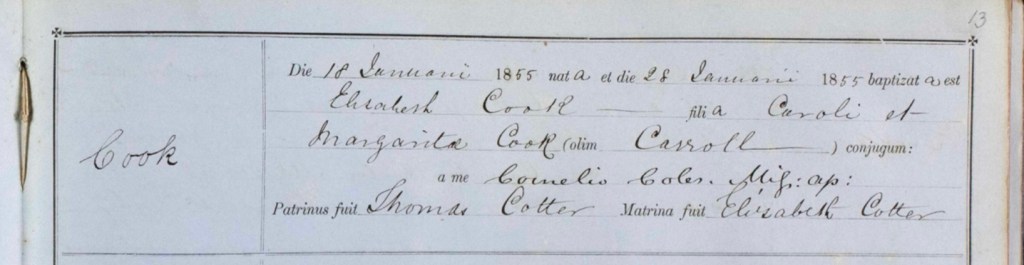

On January 28, 1855, just days after her birth, Margarita and Charles had their daughter Elizabeth baptized at St. Peter the Apostle Roman Catholic Church in Woolwich, Kent, England. This baptism was an important event in the life of the family, marking Elizabeth’s formal entry into the Catholic faith. The church, with its long history and place at the heart of the Woolwich community, provided a sacred space for the ceremony.

Elizabeth’s godparents were Thomas and Elizabeth Cotter, a reflection of the strong ties within the Catholic community and among Margarita and Charles's circle of family and friends. Choosing godparents was a significant decision for any Catholic family, as it not only ensured the child’s spiritual support but also established bonds between the family and the chosen individuals. The Cotters were trusted figures in the family’s life, further emphasizing the importance of community and faith in Margarita and Charles’s world.

This baptism marks another pivotal moment in the story of Margarita’s life, illustrating her commitment to her faith and her growing family. Each event, from the birth to the baptism, adds more depth to the narrative of her life and the lives of those she loved.

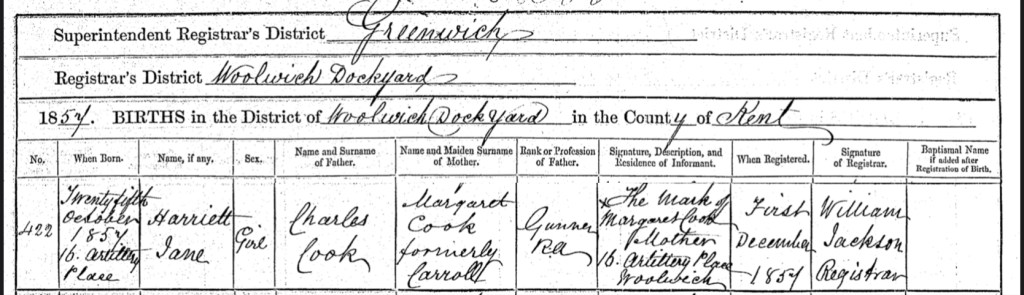

On Sunday, October 25, 1857, Margarita gave birth to their daughter, Henrietta Jane Cook, at number 16, Artillery Place, Woolwich, Kent, England. This was another significant addition to Margarita and Charles’s growing family. Just over a month later, on Tuesday, December 1, 1857, Margarita registered Henrietta’s birth in Greenwich.

At the time of registration, Margarita listed their abode as number 16, Artillery Place in Woolwich, a location that likely held great importance to the family. Charles, serving in the Royal Artillery, was listed as a Gunner in his military occupation (RA). This further solidified their ties to the military, as their life in Woolwich would have been closely intertwined with the Royal Artillery, particularly given the proximity of Artillery Place to the artillery barracks.

Henrietta’s birth record reflects not just her entry into the world, but also the family’s life in Woolwich, a time and place shaped by Charles’s military service and Margarita’s role as a devoted mother. It is moments like these that offer glimpses into their daily lives, their home, and the broader historical context in which they were living.

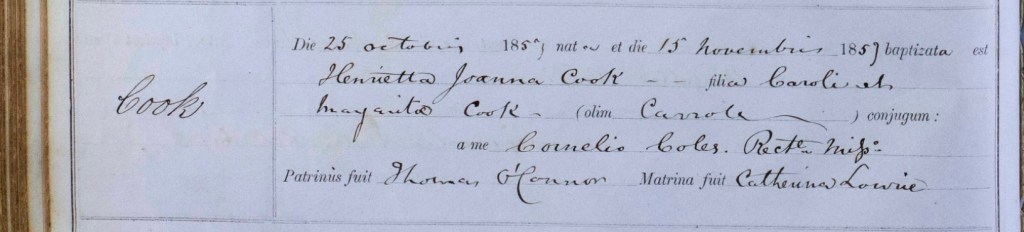

On November 15, 1857, just a few weeks after her birth, Margarita and Charles had their daughter, Henrietta Jane Cook, baptized at St. Peter’s Roman Catholic Church in Woolwich, Kent, England. This baptism was an important rite of passage for Henrietta, marking her formal introduction into the Catholic faith. The ceremony took place at a time when the family had already settled into life in Woolwich, with the church serving as the center of spiritual life for many in the area.

Henrietta was baptized under the name Henrietta Joanna Cook, a slight variation in name from the one she was registered with. Her godparents were Thomas O’Connor, likely a close relative, and Catherine Lourie, individuals whom Margarita and Charles entrusted with the spiritual guidance and care of their daughter. The choice of godparents was always a meaningful one, establishing lifelong connections and bonds within the family and community.

This baptism, occurring shortly after Henrietta’s birth, highlights the importance of faith in the family’s life and reflects the strong sense of community within the Catholic church in Woolwich.

St. Peter’s Roman Catholic Church in Woolwich, Kent, holds a significant place in the history of the Catholic community in the area. The church has long been a focal point for worship, community life, and the practice of Catholic faith in Woolwich, a district located on the southern bank of the River Thames in southeast London.

The history of St. Peter’s Church dates back to the early 19th century, a time when the Catholic community in England was experiencing a revival following the passage of the Catholic Emancipation Act of 1829. This act lifted many of the restrictions that had been placed on Catholics, allowing them to worship openly and to establish churches. Before this, Catholics in England had endured centuries of suppression, especially after the English Reformation. With the lifting of restrictions, the need for Catholic churches in urban areas like Woolwich grew rapidly.

The original St. Peter’s Church was built in the early 19th century to meet the needs of the growing Catholic population in Woolwich, many of whom were Irish immigrants, soldiers, and workers involved in the military presence at the Royal Arsenal, located nearby. As a vital center of faith for the community, the church not only provided a place for Mass and sacraments but also became a key institution for the social and cultural life of local Catholics. The church was constructed in a style that suited the liturgical needs of the time, incorporating elements that would support a vibrant and growing congregation.

Over time, St. Peter's became an integral part of the daily life of Woolwich. The church was involved in education and charity work, and it became a symbol of resilience for the local Catholic population. It was not only a place of worship but also a center for spiritual guidance, helping to foster a strong sense of community, particularly for Catholic families who lived in the area.

Throughout the years, St. Peter’s has undergone several changes, including rebuilding and renovations, reflecting the evolving needs of the parish and its congregation. In particular, the church underwent significant restoration work in the 20th century to maintain its structure and adapt to modern times. However, its rich history has been carefully preserved, and the church continues to serve as a place of worship and community for the people of Woolwich.

Today, St. Peter’s Roman Catholic Church remains an active and important landmark in the area. It still plays a central role in the religious and community life of Woolwich, offering Mass and other sacraments, as well as supporting local charitable efforts. The church is not only a place of historical significance but also a living institution that continues to shape the lives of many people in the community. Its long history, beginning in the early 19th century, reflects the perseverance and faith of the Catholic community in Woolwich, making it a cornerstone of both local history and religious life in the area.

St. Peter’s Roman Catholic Church

in Woolwich, Kent,

around the 1850s.

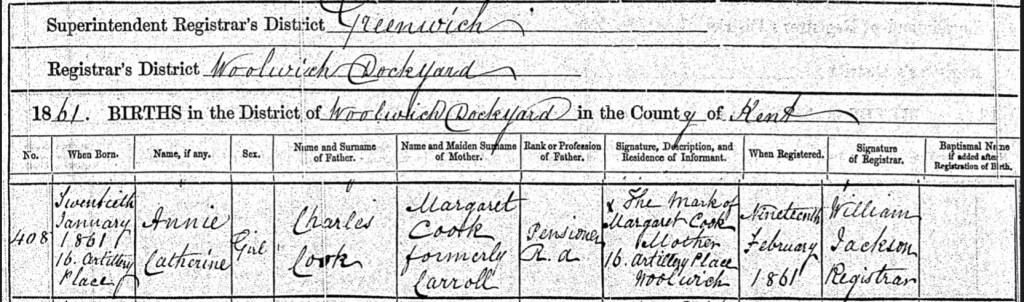

On Sunday, the 20th day of January, 1861, Margarita and Charles joyously welcomed their precious daughter, Annie Catherine Cook, into the world. Their home, nestled at 16 Artillery Place in the heart of Woolwich Dockyard, Woolwich, Kent, England, became the setting for a new chapter in their lives.

In the early weeks of February 1861, Margarita, with a sense of proud responsibility, registered the birth of their daughter. She carefully noted their residence at 16 Artillery Place, a place that had been their family’s foundation. When detailing Charles’ occupation, Margarita described him as a Pensioner in the Royal Artillery, a testament to his years of service.

As Margarita signed the birth registration, she left her mark with a simple, yet poignant gesture. Once again, her name was recorded as “Margaret,” a familiar variation of the name she carried through her life. It was a moment filled with both the weight of tradition and the warmth of family, a bond that would last through the ages.

On Sunday, February 7th, 1861, a sacred occasion unfolded as Margarita and Charles, with hearts full of love and devotion, had their daughter, Anne Catherine Cook, baptized at St. Peter the Apostle Roman Catholic Church in Woolwich, Kent, England. It was a moment of deep significance, marking the beginning of Annie’s spiritual journey.

In the presence of family and faith, her godparents, John Henry, Ellen Cook, and Catherine Rafferty, stood by her side, pledging their love and guidance. In a beautiful tradition, Annie was baptized as “Annae,” a variation of her given name, a reflection of the reverence surrounding the ceremony.

The warm and cherished memories of that day would forever live in the hearts of all who gathered, as little Annae was welcomed into the fold of faith, embraced by the love of her family and the community.

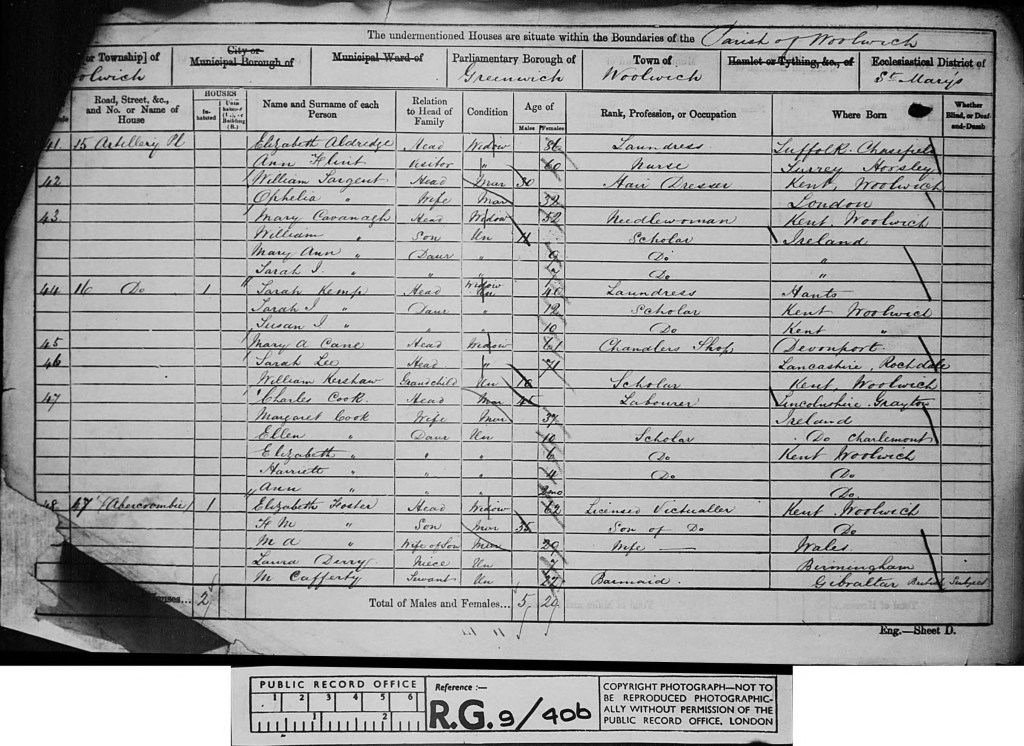

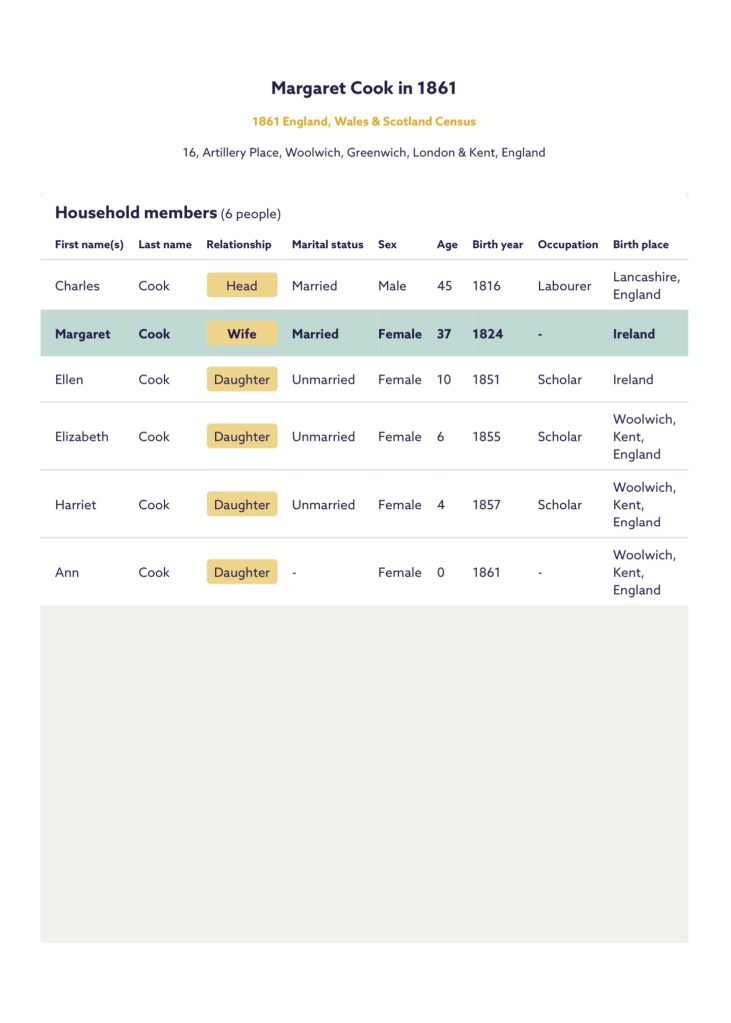

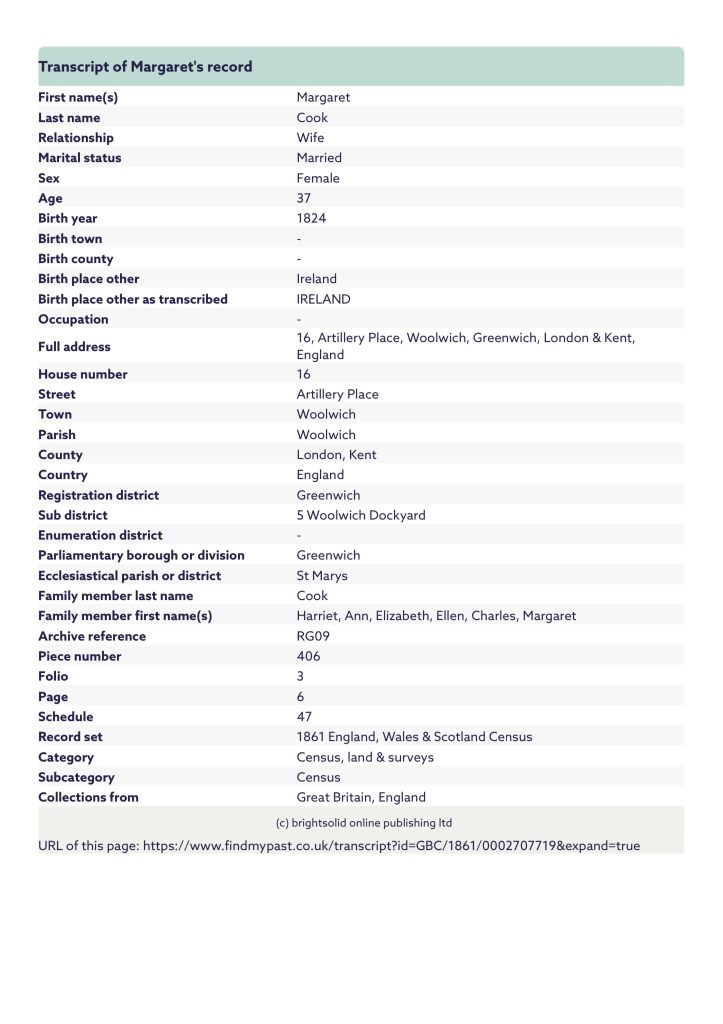

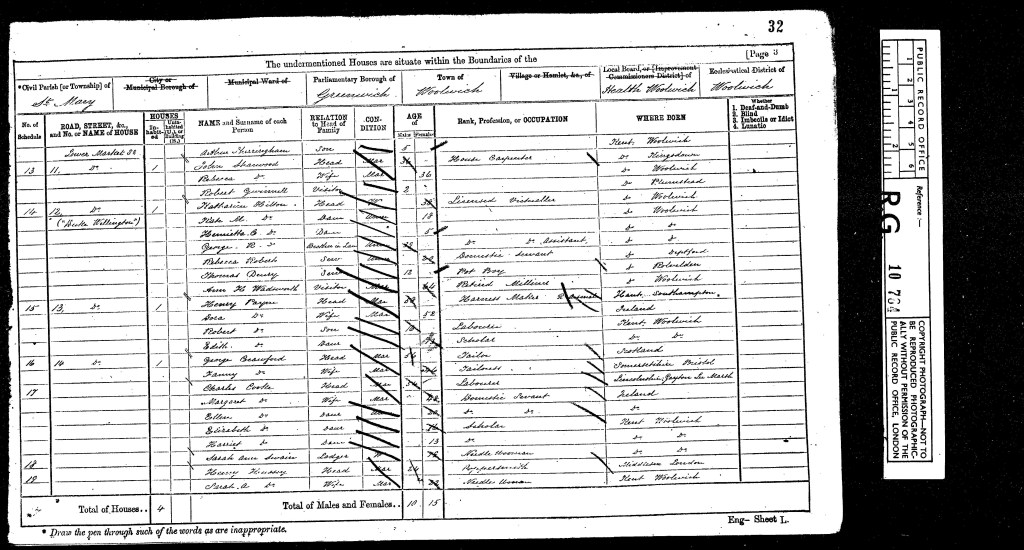

On Sunday, April 7th, 1861, the national census was conducted, capturing a snapshot of life for Margarita (also known as Margaret), Charles, and their children. The family was living at 16 Artillery Place, nestled between Woolwich and the border of Greenwich, London and Kent, England. It was a place that held both history and home for the family.

Charles, having transitioned from his military service, was working as a laborer, providing for his family through hard, honest work. Margarita, ever devoted to her children, had their daughters, Ellen, Elizabeth, and Harriet, busy as scholars, expanding their minds and growing in education.

In that moment, on that Sunday in 1861, this simple census entry painted a picture of a hardworking family, living in the heart of Woolwich, balancing life’s demands with a deep sense of care and commitment to one another.

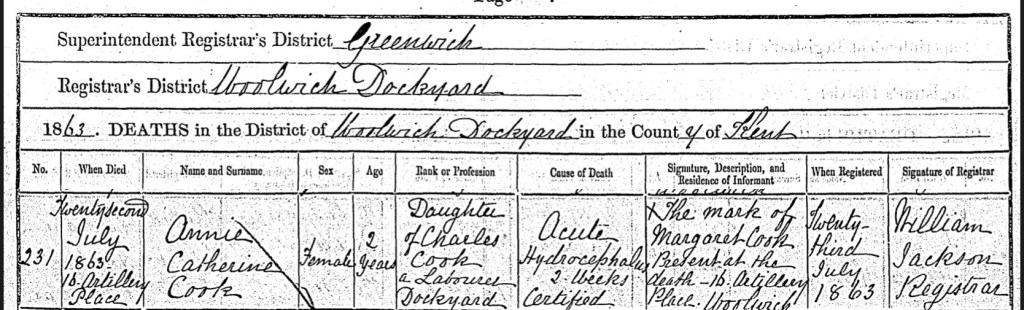

With heavy hearts, we remember the tragic passing of little Annie Catherine Cook, the beloved daughter of Margarita and Charles. On Wednesday, July 22nd, 1863, Annie, just two years old, passed away at their home at Number 16, Artillery Place, Woolwich Dockyard, Woolwich, Greenwich, London & Kent, England.

Annie's cause of death was Acute Hydrocephalus, a painful condition involving the buildup of fluid on the brain. It was a heartbreaking loss for Margarita and Charles, a sorrow that would leave a permanent mark on their family.

Margarita, ever the devoted mother, was present at her daughter’s side during her final moments. The following day, on July 23rd, 1863, Margarita registered Annie’s death, her heartache evident as she recorded the details. In her registration, she gave their residence as 16 Artillery Place, Woolwich, and listed Charles' occupation as a Dock Labourer, a reflection of the family’s life at the time. Margarita left her mark on the document, a silent but poignant reminder of the love and grief she carried for her dear daughter, Annie.

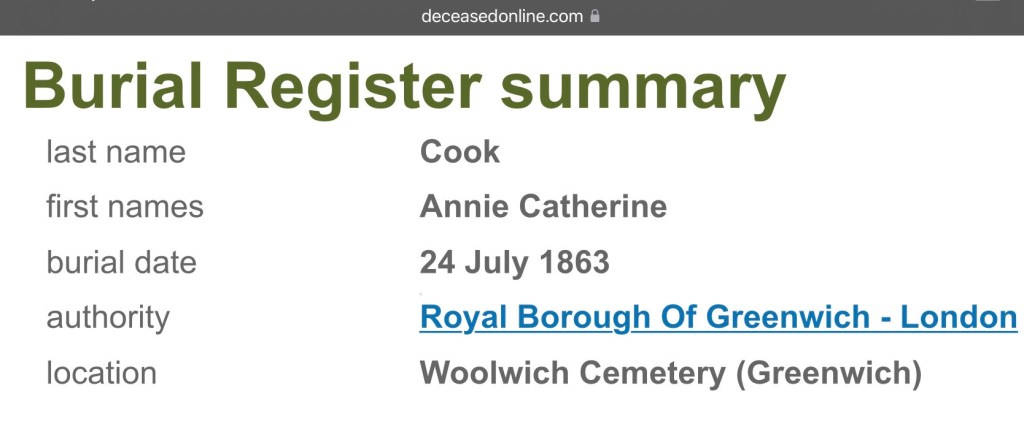

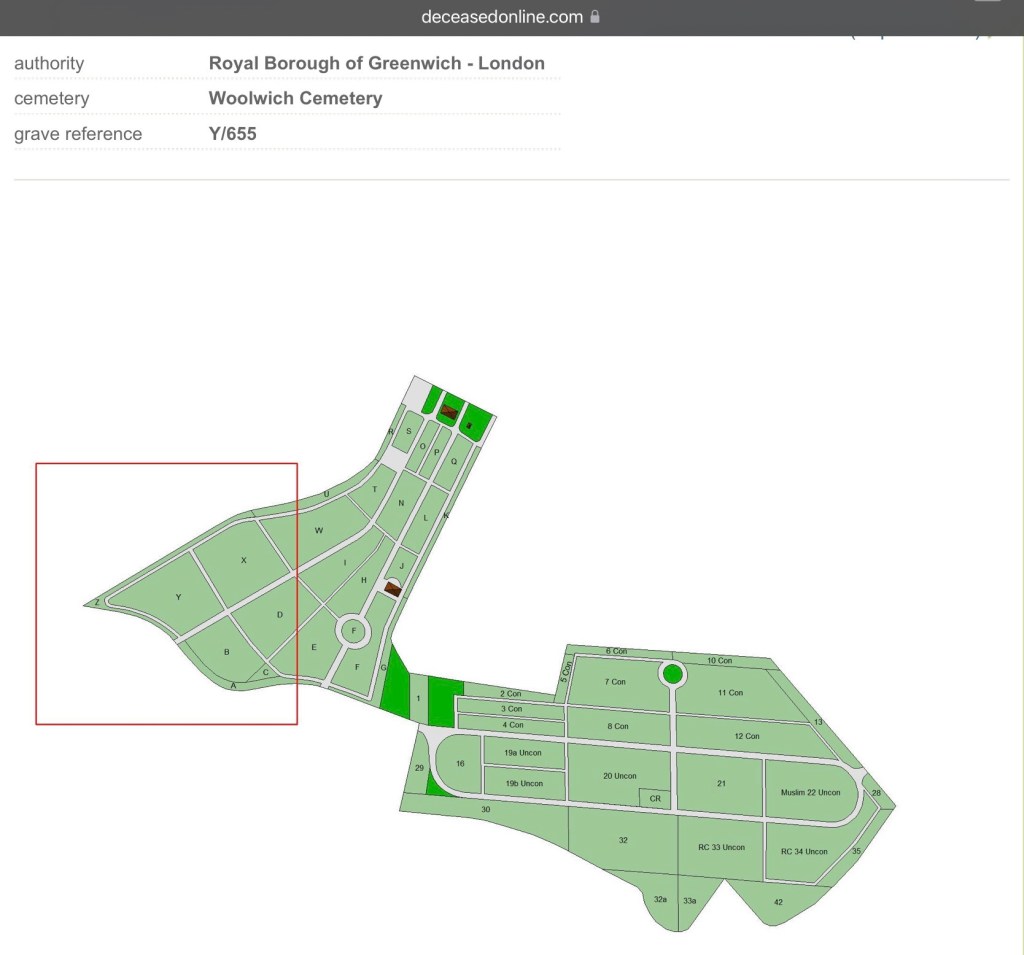

On the 24th of July, 1863, Margarita and Charles, in their profound sorrow, laid their precious daughter, Annie Catherine Cook, to rest at Woolwich Cemetery, Woolwich, Greenwich, London, England. Annie, just two years old, was interred in Grave Y/655, a resting place that would forever hold the memory of their beloved child.

Annie’s final resting spot was shared with two others, Allen, Louisa, and Collett, Harry, whose graves lay alongside hers, perhaps offering a quiet companionship in eternity. Though their hearts were heavy with grief, Margarita and Charles found solace in the ritual of laying their daughter to rest, forever marking the spot where Annie’s spirit would remain, embraced by the earth in the place she called home.

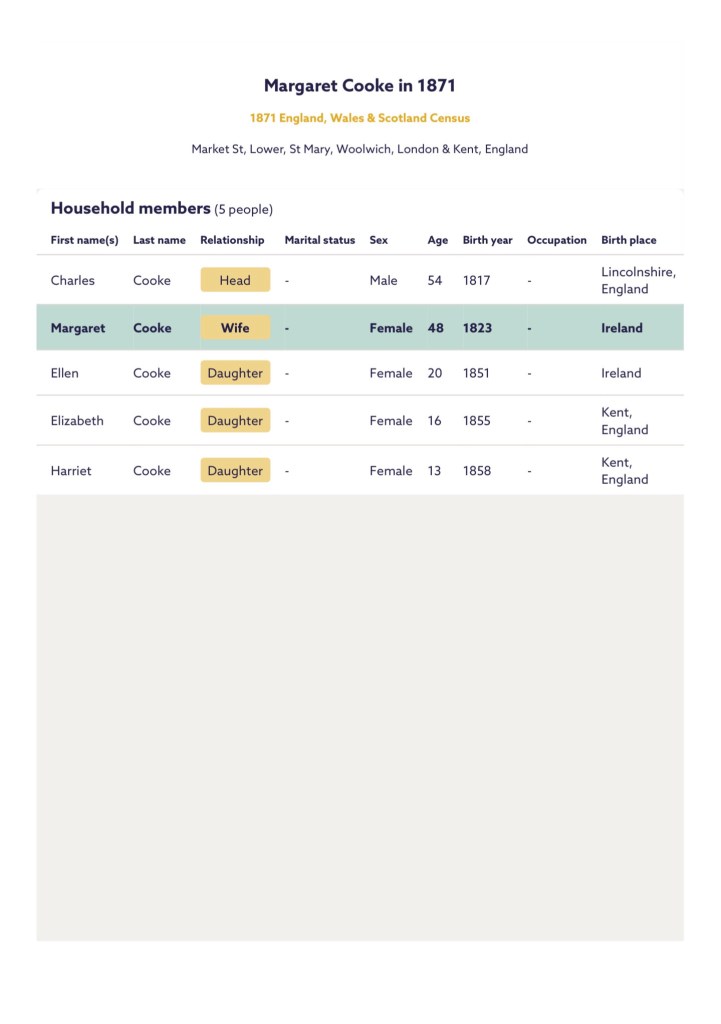

On Sunday, April 2nd, 1871, Margarita, Charles, and their children—Ellen, Elizabeth, and Harriet Cooke—were residing at Market Street, Lower, St. Mary, Woolwich, in the heart of London and Kent, England. It was a new chapter for the family, as they continued to navigate life’s challenges with resilience and love. Margarita and Ellen were both employed as domestic servants, likely working in nearby households, while Charles labored as a laborer, supporting his family with hard, manual work. Meanwhile, Elizabeth and Harriet were attending school, their young minds continuing to grow and learn.

The household was also home to a lodger, a lady named Sarah Ann (last name uncertain), who worked as a needlewoman, using her sewing skills to make a living. Sarah Ann’s presence added to the busy atmosphere of their home, a quiet reminder of the shared experiences and connections that defined the lives of those living in the community.

Together, this family continued to forge their path, marked by the strength and determination that defined their lives in Woolwich.

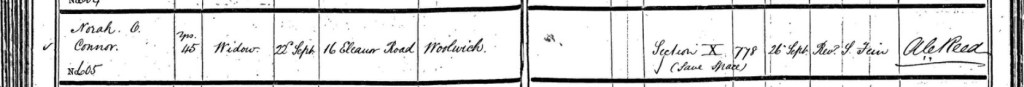

On Sunday, September 22nd, 1872, Margarita’s sister, Honora, sadly passed away at her home at 16 Eleanor Road, Woolwich, Kent, England. Honora succumbed to the ravages of Typhoid Fever, a devastating illness that claimed her life far too soon.

Margarita, ever the devoted sister, was at Honora’s side in her final moments, offering comfort and support through the pain. In the days that followed, Margarita registered Honora’s death on September 29th, 1872, a task that would forever remind her of the sorrow she had endured. When she recorded the details, Margarita gave their home address as Artillery Place, Woolwich, her own residence where she had made a life with her family.

Honora’s passing marked a heartbreaking chapter in Margarita’s life, a loss that would be carried in her heart for years to come.

On Thursday, September 26th, 1872, Margarita and her family, in their sorrow, laid Honora to rest at Woolwich Cemetery, Woolwich, Kent, England. Honora, beloved sister to Margarita, was interred in Grave X/778, where she would find eternal peace.

Honora’s final resting place was shared with two others: her late husband, Thomas O’Connor, and Parrick Bradley. The presence of these individuals in the same grave marked a quiet connection across generations, a reminder of the bonds that had defined their lives and the love that endured beyond death.

Margarita, along with the rest of the family, said their final goodbyes, their hearts heavy with grief as they placed Honora to rest, forever remembering her in the place where she would lie in peace alongside those she had loved.

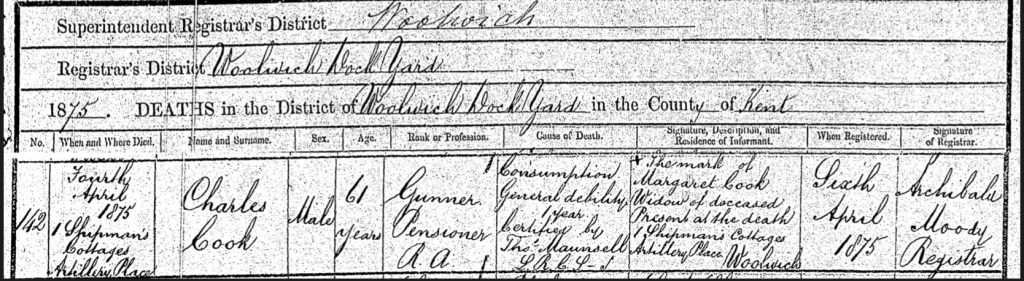

With deep sorrow, we recount the passing of Charles Cook, Margarita's devoted husband, on April 4th, 1875. At 61 years old, Charles, a former Royal Artillery Gunner who had earned a pension for his years of service, passed away at 1 Shipman’s Cottages, Artillery Place, Woolwich Dockyard, Woolwich, Kent, England. His death was attributed to consumption and general debilitation, conditions that had taken their toll on him over time.

Margarita, who had been by his side through his final days, was present when Charles passed. On April 6th, 1875, she registered his death in Woolwich, marking the event with her own sign of grief, as she left her mark on the official document. It was a moment of immense loss for Margarita, who had shared so much of her life with Charles.

Charles' death marked the end of an era for the family, as they said goodbye to a husband and father, whose legacy of service and love had shaped their lives. The weight of this loss was felt deeply, as Margarita carried on, forever remembering the man she had loved and shared so many years with.

On April 10th, 1875, Charles Cook was laid to rest in Woolwich Cemetery, Plumstead, Woolwich, Kent, England. His final resting place, marked by a shared grave, was Grave Z/73. Charles was interred alongside three others: Mary Williams, who was buried on May 21st, 1883; Harriet Williams, who passed on November 13th, 1880; and Emma Ingham, whose burial took place on August 27th, 1867.

Though each of these individuals had their own story, their lives converged in this quiet corner of Woolwich Cemetery, where they would rest together, side by side. For Margarita and her family, Charles’ burial marked the end of an era, as they bid farewell to the man who had been a pillar of strength in their lives. In the graveyard, amid the peaceful surroundings, Charles now rested among others who had also journeyed through life and its many challenges, their stories intertwined in the stillness of the cemetery.

In 1881, the world was a fascinating mixture of progress and hardship. Queen Victoria, steadfast on the throne, presided over an empire at its peak, while William Ewart Gladstone, leading the Liberal government of the 22nd Parliament, attempted to navigate the complex political and social issues of the time. The chill of that year was memorable, particularly in Ireland, where the cold bit deeper than ever before, plunging to a bone-numbing −19.1°C at Markree, County Sligo.

The atmosphere of the time was both vibrant and turbulent. Across England, steam-powered trains chugged along well-established tracks, weaving the nation together in ways unimaginable a century earlier. Horse-drawn carriages clattered over cobblestone streets in towns and cities, while in rural areas, the creak of wooden carts pulled by plodding horses echoed the slower pace of village life. In Woolwich, the Royal Arsenal remained a hub of activity, its smokestacks visible from miles away, a symbol of industrial might and the labor of countless workers.

Heating in homes was rudimentary for most. Open hearths were the primary source of warmth, with coal the preferred fuel for those who could afford it. For the working class, a small fireplace struggled to heat a single room, while the poor made do with little more than layers of clothing and shared body heat. Plumbing, if it existed at all, was basic and crude, with chamber pots and outhouses still commonplace. The disparity between the rich and poor was starkly visible; grand homes of the wealthy boasted indoor plumbing, gas lighting, and ornate furnishings, while tenements in urban slums were overcrowded, damp, and dangerous.

Fashion mirrored societal divisions. The upper classes adorned themselves in tailored suits, silk gowns, and elaborate hats, setting trends that trickled down to the middle classes in cheaper imitations. For the working poor, practicality ruled—sturdy boots, rough fabrics, and aprons for the women were the norm, their clothing patched and worn from years of hard use. Entertainment varied by class as well: the wealthy enjoyed operas, balls, and private salons, while the working class sought respite in public houses, music halls, and, increasingly, the cheap thrills of early penny dreadfuls and serialized novels.

Education was slowly improving, especially after the Elementary Education Act of 1870, but for many working-class children, schooling remained a luxury secondary to earning a living. Wealthier families sent their children to well-funded schools, often with the expectation of university education, while poorer children were more likely to labor in factories or service jobs from an early age.

Food reflected the divide between rich and poor as well. The upper classes dined on lavish meals featuring roast meats, fine wines, and imported delicacies, while the poor subsisted on bread, potatoes, and occasionally scraps of meat or fish. For many families, hunger was a constant companion, and soup kitchens and charity organizations were lifelines.

In the gossip of the day, tales of royal family scandals or the escapades of the aristocracy would circulate in whispered tones or printed in scandal sheets. Closer to home, neighbors and communities thrived on tales of births, marriages, and the occasional scandal, a form of social glue that kept communities connected despite the hardships.

Major events shaped the backdrop of these personal lives. Gladstone’s second Land Act promised reforms in Ireland, introducing the three “f”s, fair rents, fixity of tenure, and freedom of sale, though its success was limited by resistance and the ongoing land agitation. The Irish National Land League was declared unlawful, heightening tensions as Ireland’s fight for autonomy persisted. Bombings, such as the one at Salford’s military barracks, brought the Fenian dynamite campaign closer to the public consciousness, a stark reminder of political unrest.

In quieter moments, new beginnings were also being forged. The London Evening News was first published, offering news and stories to a growing literate public. Charitable work flourished as Edward Rudolf founded the Church of England Central Society for Providing Homes for Waifs and Strays, an early step toward better care for vulnerable children. Meanwhile, Carmelite nuns established Kilmacud Monastery, continuing the spiritual and charitable work that formed a counterpoint to the era’s industrial and political upheavals.

In the midst of these vast historical movements, the daily lives of people like Margarita Carroll unfolded, shaped by the same forces of change, resilience, and hope that defined the world of 1881.

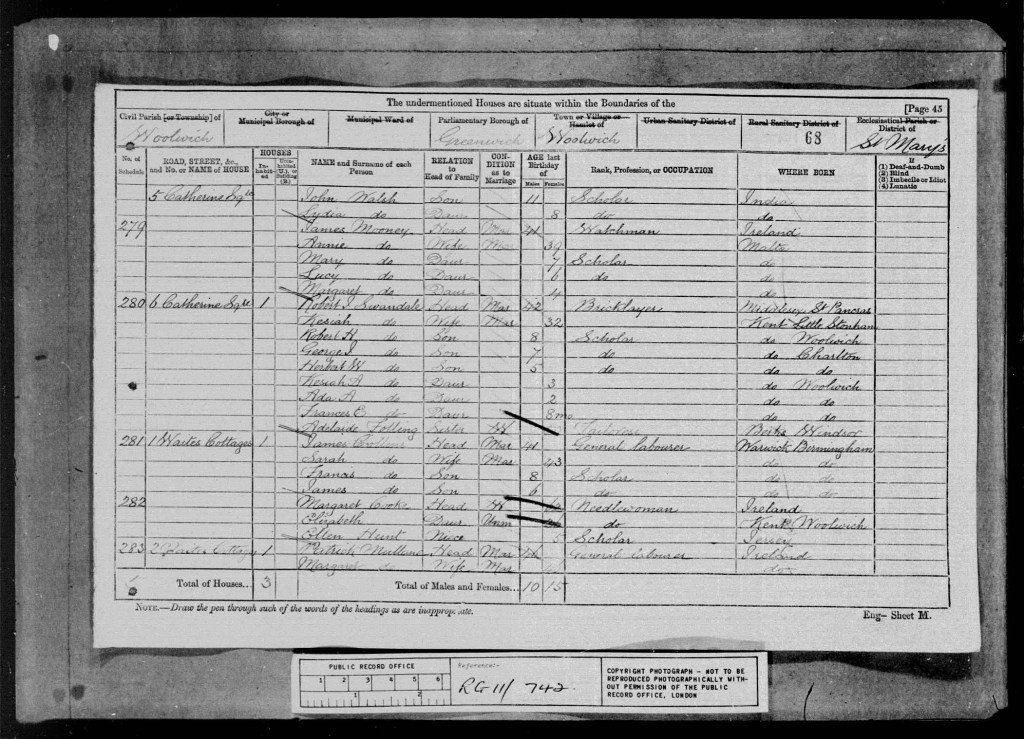

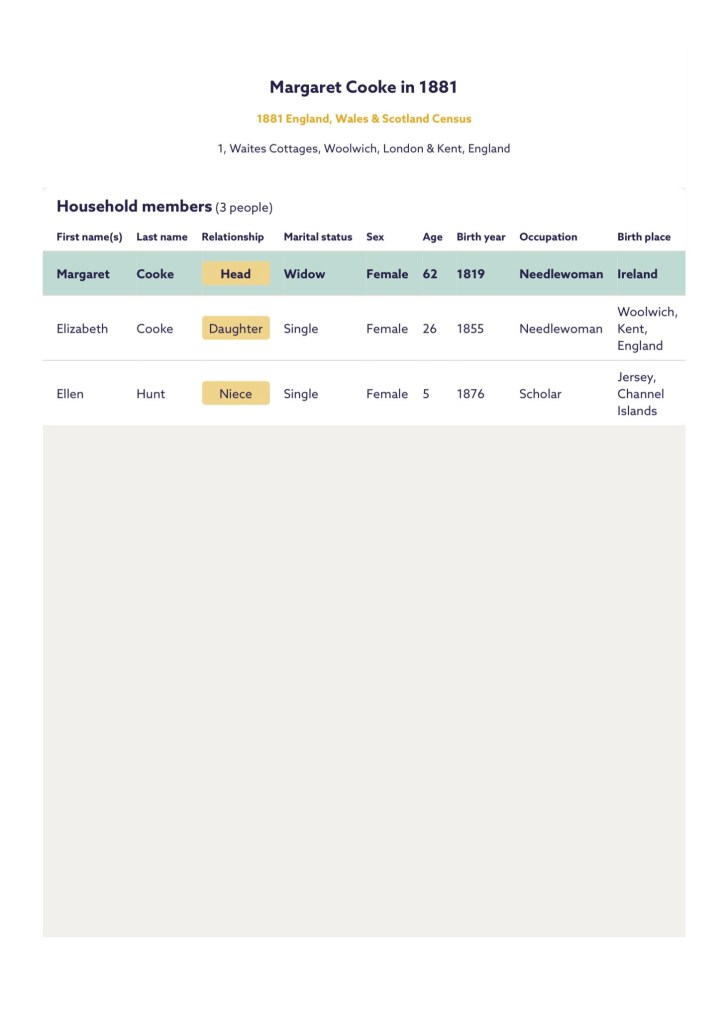

On the evening of Sunday, the 3rd day of April, 1881, the United Kingdom Census captured a snapshot of life across the country, and among those recorded was Margarita Carroll. By this time, Margarita was living at 1 Waites Cottages in Woolwich, Kent, a modest home nestled amidst the industrial and military bustle of the town. Woolwich, with its close ties to the Royal Arsenal, was alive with activity, but life within the cottage was far more humble and quiet.

Margarita, now middle-aged, was working as a needlewoman alongside her daughter Elizabeth. Needlework was a common trade for women of modest means, involving long hours bent over fabrics, creating or mending garments for a pittance. It required precision and patience, and though it was steady work, it was by no means lucrative. The income it provided was often barely enough to sustain a household, let alone offer luxuries or savings.

Living with Margarita and Elizabeth was her niece, Ellen Hunt, a young scholar attending school. Ellen’s presence may have brought a breath of youthful energy to the household, and her schooling was a glimmer of hope for a better future. Education for girls, though improving, was still far from universal, and it was a privilege for a working-class family to ensure a child received some schooling. Ellen’s time in the classroom likely focused on basic literacy, arithmetic, and perhaps a touch of geography or scripture.

Life in 1881 for Margarita and her small household was not easy. Woolwich, though vibrant, was a place of stark contrasts. The docks and factories provided work but also polluted the air and waters. The disparity between the wealth of the officers and industrialists and the working poor was ever-present. Streets would have been busy with carts and carriages, and the sounds of industry and the chatter of market stalls filled the air. Yet, in homes like Margarita’s, the focus was on daily survival, making enough to put food on the table, keeping the house warm with coal fires, and finding moments of joy amidst the struggles.

The census entry, brief as it is, opens a window into Margarita’s life at this moment in history. It tells a story of resilience and the bonds of family, of women supporting one another in a world that often offered them few opportunities. Margarita’s work as a needlewoman and her care for both her daughter and niece speak to her strength and determination, traits that no doubt carried her through the many challenges she had faced.

Waites Cottages in Woolwich, Kent, were modest dwellings that housed working-class families during the 19th century. These cottages were situated in a bustling area known for its industrial and military significance, particularly due to the presence of the Royal Arsenal, a major munitions factory. The cottages themselves were likely constructed to accommodate the influx of workers drawn to Woolwich by employment opportunities in the Arsenal and related industries.

Life in Waites Cottages would have been characterized by simplicity and hard work. The residents, such as Margarita Carroll and her family, often engaged in trades to make a living. The interiors of these cottages were modest, with basic furnishings and limited space, reflecting the economic constraints of their inhabitants. Heating was typically provided by coal fireplaces, and plumbing facilities were rudimentary, with many households relying on communal water sources and outdoor privies.

The surrounding area of Woolwich was a hive of activity, with the constant movement of goods and people associated with the Royal Arsenal. The streets would have been filled with the sounds of horse-drawn carts, factory whistles, and the chatter of workers. Despite the industrial environment, a sense of community likely flourished among the residents of Waites Cottages, as neighbors relied on each other for support amidst the challenges of working-class life.

Unfortunately, specific historical records or photographs of Waites Cottages are scarce, making it difficult to provide detailed visual descriptions or images of the cottages themselves. However, the general conditions and lifestyle of similar working-class housing in 19th-century Woolwich can offer insights into the daily experiences of their residents.

As we step into the year 1891, the world was alive with change, yet deeply marked by enduring struggles and monumental events. Margarita Carroll, now in her later years, lived through an era defined by contrasts, progress and poverty, innovation and loss, connection and separation.

The death of Charles Stewart Parnell shook Ireland and its diaspora. Known as the “Uncrowned King of Ireland,” Parnell had been a figure of hope for many Irish people, embodying their aspirations for land reform and self-governance. His funeral, attended by up to 200,000 mourners, was not just a farewell to a leader but a symbolic gathering of national grief and unity. For Margarita, born in Ireland but long settled in England, such news may have stirred memories of her homeland and the unresolved struggles of the Irish people. It was a poignant reminder of her roots amidst her life in England.

In 1891, political and social change continued to shape the world. The Balfour Land Act sought to address poverty in Ireland’s rural areas, offering funds for land purchase and establishing the Congested Districts Board to aid struggling communities. Meanwhile, the industrial cities of England hummed with activity, their skies darkened by coal smoke and their streets teeming with workers. Woolwich, where Margarita resided, was a hub of military and industrial enterprise, its docks and factories alive with the sounds of labor.

The working poor, like Margarita and her family, lived in modest homes where coal fires provided heat and water was often a shared commodity. Plumbing, if present, was basic, and daily life demanded resilience and resourcefulness. Fashion for the working class was simple and practical, a stark contrast to the elaborate attire of the wealthy, who paraded in corseted gowns and tailored suits, often oblivious to the struggles of those who made their finery possible.

Entertainment for working families was modest, centering around community gatherings, evenings in public houses, or occasional visits from traveling performers. Children, if fortunate, attended school, as mandatory education laws were beginning to transform opportunities for the younger generation. Ellen Hunt, Margarita’s niece, was likely one of the children benefiting from these changes, her schooling a beacon of hope for a better future.

Food for working families was plain and often scarce. Markets buzzed with activity as women haggled for fresh produce and children darted through the crowds. Bread, potatoes, and the occasional treat of fish or meat formed the staples of their diets. Gossip flowed freely in these spaces, where neighbors shared news and stories of scandal or triumph, from the grand affairs of the monarchy to the daily dramas of local life.

Elsewhere, innovation was reshaping the world. Steamships and railways made travel faster, connecting cities and nations, though not without risk, as evidenced by the tragic sinking of the SS *Utopia* in Gibraltar’s harbor, which claimed over 500 lives. Such advancements brought both opportunity and peril, emblematic of an age pushing boundaries.

In literature and culture, the seeds of modernity were taking root. A young James Joyce, only nine years old, wrote a poem mourning Parnell, his words hinting at the literary brilliance to come. Such creative endeavors reflected a world beginning to value the arts and education alongside industry and politics.

For Margarita, life in 1891 was likely a mix of quiet endurance and adaptation to a rapidly changing world. Her experiences mirrored the era—a blend of hardship and hope, tradition and transformation. Though her story may seem ordinary against the backdrop of great events, it is in the lives of women like her that the true fabric of history is woven.

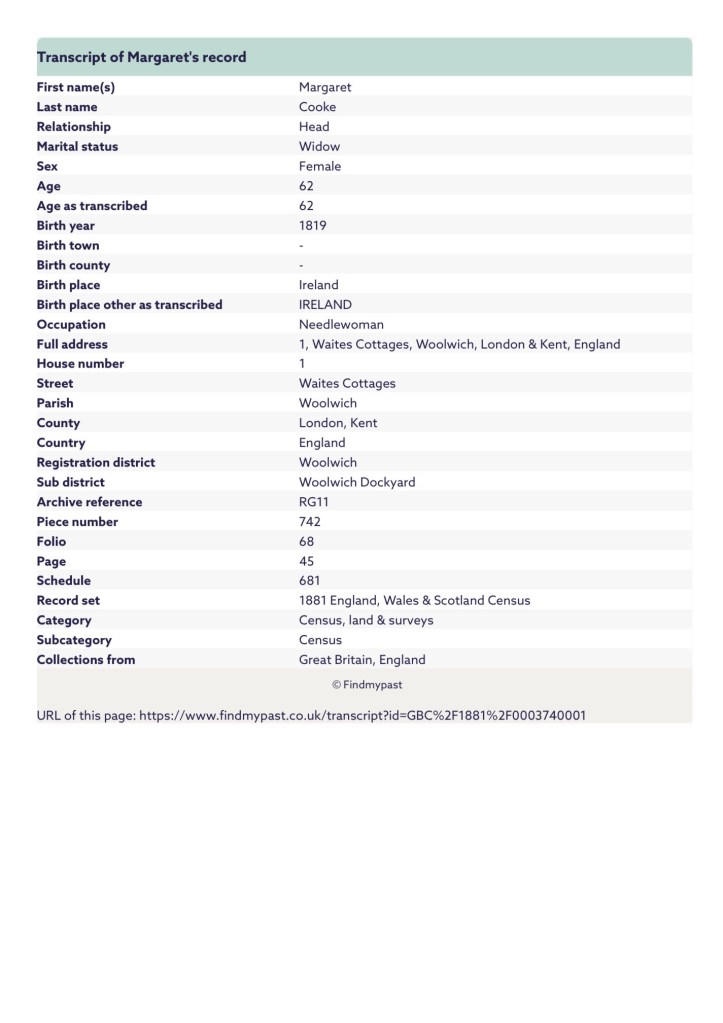

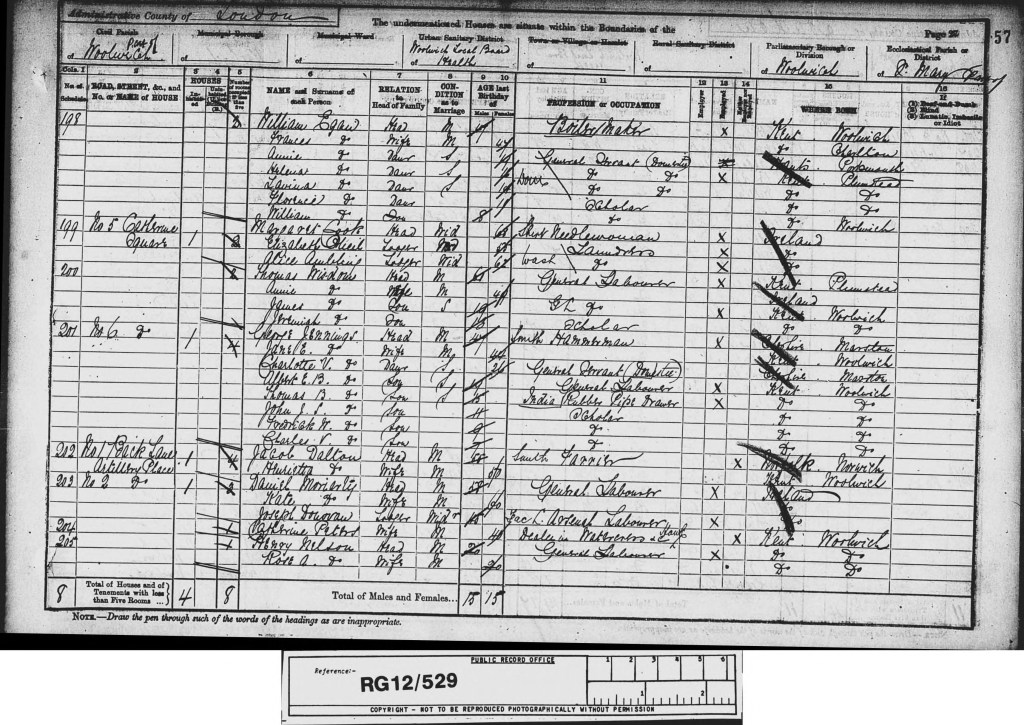

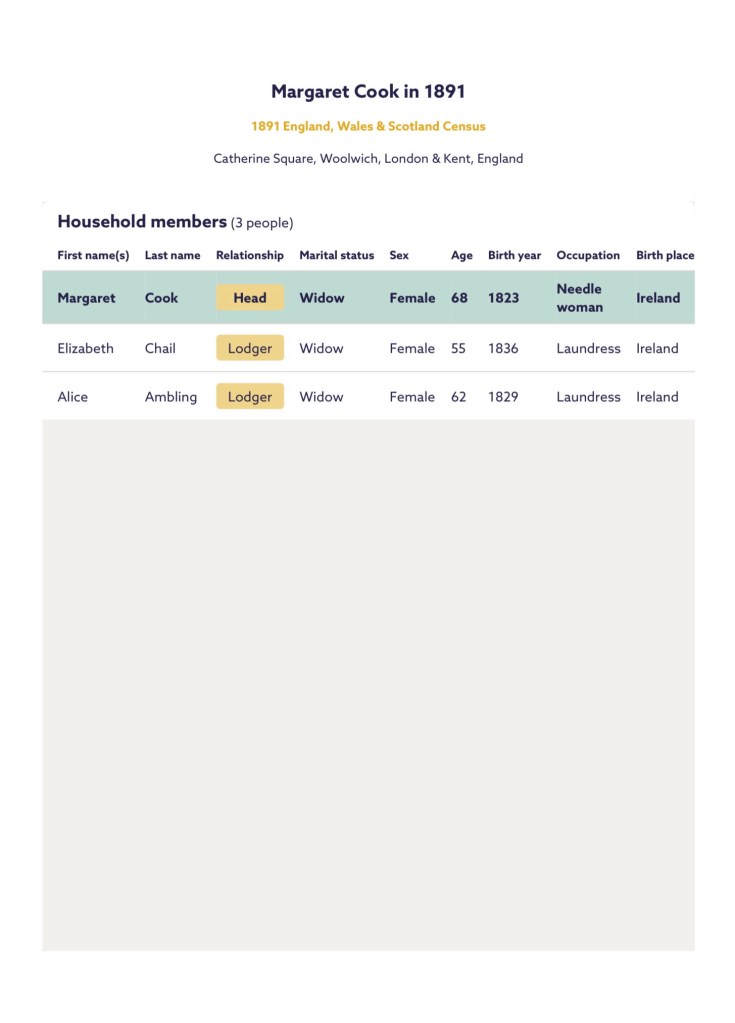

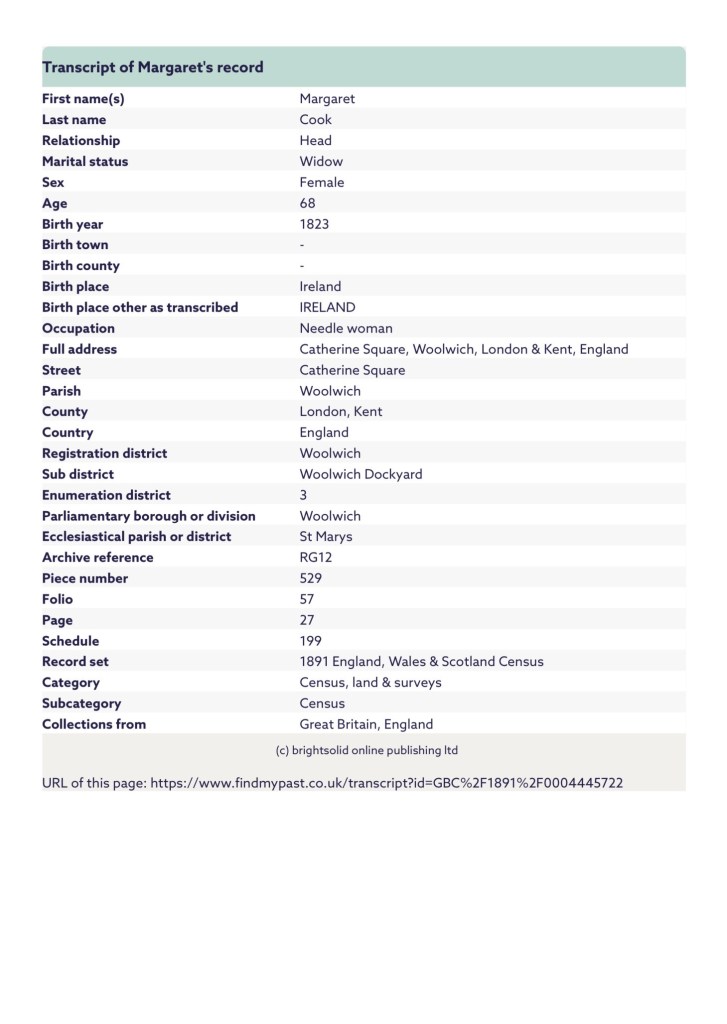

The 1891 Census of the United Kingdom, taken on the eve of Sunday, the 5th of April, paints a poignant picture of Margarita Carroll's life as it unfolded in Catherine Square, Woolwich, London, and Kent. By this time, Margarita was living with two other women, Elizabeth Chail and Alice Ambling, both widows like herself. All three women were Irish-born, their shared heritage likely a source of mutual understanding and companionship in their modest lodgings.

Life in Catherine Square would have been a reflection of the struggles and camaraderie shared among working-class women in late 19th-century England. Margarita, working as a needlewoman, stitched not only garments but also the threads of her survival. Her companions, Elizabeth and Alice, found their livelihoods as laundresses, laboring over steaming tubs and heavy irons to earn their keep. Together, the three women formed a small but resilient community, leaning on one another in a world that was often unforgiving to widows and the working poor.

Woolwich, with its mix of military industry and bustling docks, was a vibrant, gritty place where the clash of opportunity and hardship was palpable. The air was thick with coal smoke, the streets alive with the clatter of carts and the chatter of neighbors. Margarita’s days would have been filled with the hum of sewing needles and the rhythms of daily toil, punctuated by conversations with Elizabeth and Alice as they folded and pressed linens, sharing stories of their pasts and hopes for the future.

Their shared Irish roots may have offered a sense of solace amidst the challenges of life in England. They might have reminisced about their homeland, recalling its lush green fields and the hardships that had driven so many to leave.

The census, though a mere snapshot in time, offers a deeply human glimpse into Margarita’s world. It reveals her strength and determination, her ability to carve out a life in the face of adversity. In the company of Elizabeth and Alice, she was part of a story shared by countless women of her era, a story of survival, solidarity, and the unyielding spirit of those who laboured quietly behind the scenes of history.

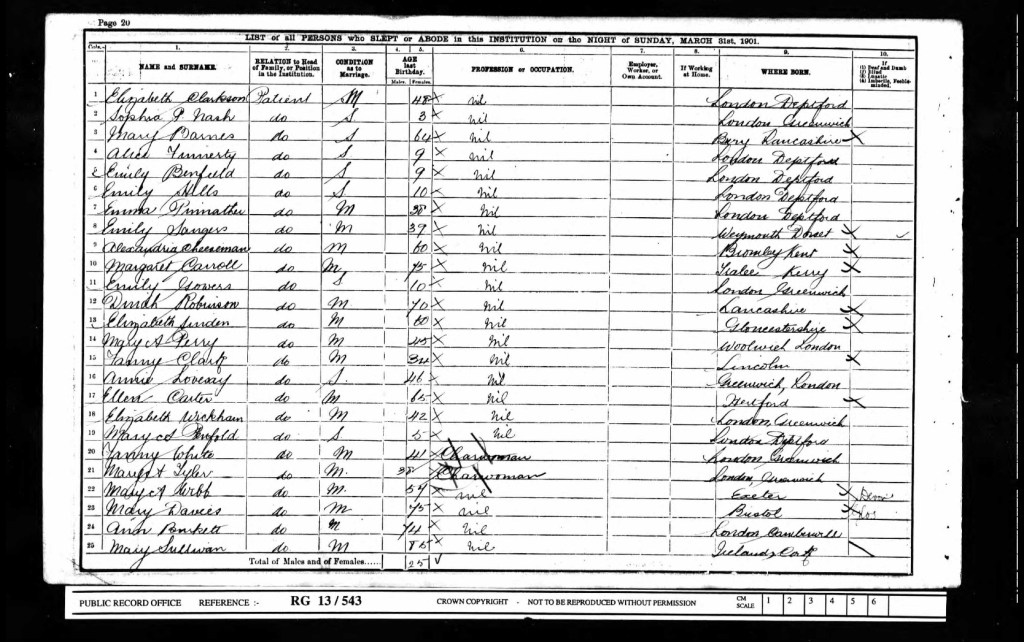

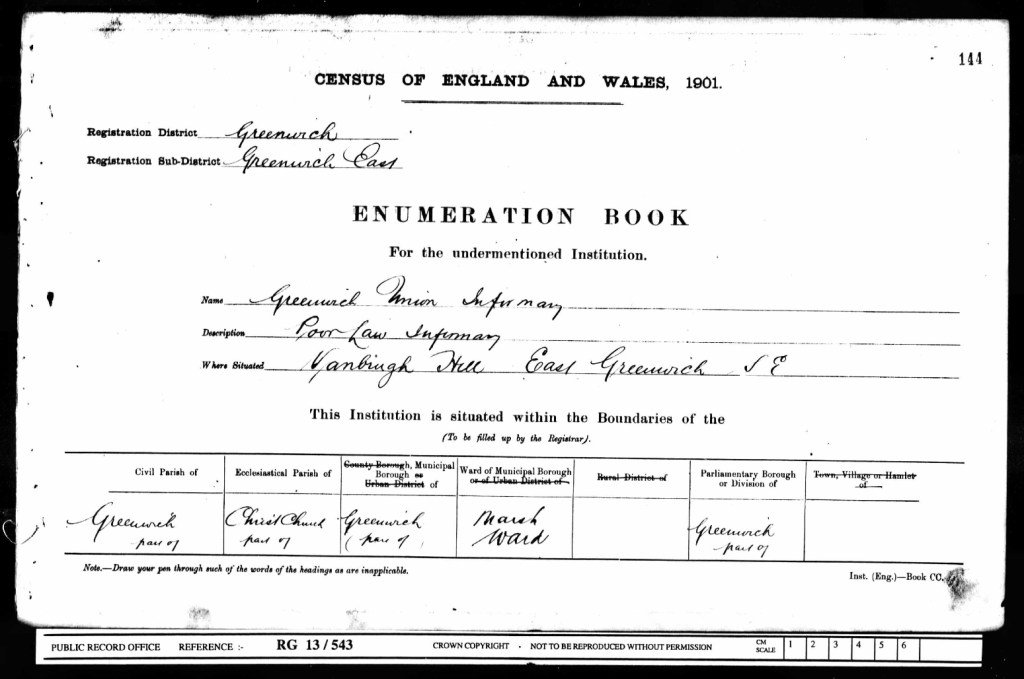

By 1901, Margarita Carroll's life had taken a somber turn, as the census of that year places her within the walls of the Greenwich Union Workhouse on Vanbrugh Hill, Greenwich, Kent. At 75 years old, she was listed as married but without an occupation, a poignant reflection of the hardships faced by the elderly and vulnerable in this era. The census also notes her birthplace as Tralee, County Kerry, Ireland, a reminder of the journey that had brought her from her Irish roots to the industrial heart of England.

Life in a workhouse was harsh and unforgiving, a last resort for those who had no other means of support. By the turn of the century, the workhouses, established under the Poor Law, were intended as a safety net for the destitute, but they often carried a heavy stigma. For someone like Margarita, who had likely known both joys and sorrows in her long life, ending up in such a place would have been a humbling experience.

The Greenwich Union Workhouse, like many others, was a bleak and regimented institution. Dormitories were often overcrowded, meals were basic, and the days were governed by strict rules and routines. Heating and plumbing were rudimentary at best, and the cold, damp conditions of a London workhouse could be particularly hard on the elderly. Residents, even those too frail to work, were expected to adhere to the institution's rigid schedules.

The atmosphere of the workhouse would have been one of quiet resignation punctuated by moments of camaraderie among the residents. There would have been gossip and shared stories, small acts of kindness, and a fragile sense of community among those who found themselves in similar circumstances. Margarita, with her Irish heritage and long life filled with experiences, might have shared tales of her journey from Tralee to Woolwich, of raising her children, and of the many changes she had witnessed over the decades.

By 1901, the world outside the workhouse was changing rapidly. Queen Victoria had passed away just months earlier, marking the end of an era, and her son, Edward VII, was now on the throne. The dawn of the 20th century was bringing new technologies and societal shifts, yet for many of the poor, life remained a daily struggle. Social divisions were still stark, with the wealthy enjoying opulent lifestyles while the working class and destitute toiled to survive.

In this context, Margarita's presence in the workhouse underscores the precariousness of life for so many of her generation. Without a social safety net like the ones we know today, the elderly who could no longer work and had no family to support them were often left with few options. For Margarita, the workhouse was a place of shelter, but it also marked a challenging chapter in a life that had seen both triumphs and trials.

Her listing in the census as "married" suggests a lingering connection to her identity and her past. Though separated from her family and community, she carried with her the memories of a life lived with resilience and determination. The note of her birthplace, Tralee, Kerry, Ireland, serves as a poignant anchor to her roots, a reminder of the place where her story began, even as she faced the realities of her twilight years far from home.

On April 2nd, 1870, the Revd Francis Cameron laid the foundation stone for the Woolwich Union workhouse, an institution that would become a central part of many people's lives. The stone was inscribed with the words, "The poor ye have always with you," a solemn reminder of the workhouse’s role in society. Situated on Tewson Road, between Skittles Alley (now Riverdale Road) and Cage Lane (now Lakedale Road), just south of Plumstead High Street, the building was designed by the architectural firm Church and Rickwood.

In 1901, my 4th great-aunt Margarita would have experienced life in this workhouse, a challenging environment marked by routine, hard labor, and the relentless pressure to conform. As a female inmate, Margarita’s life would have been shaped by the strict rules and divisions that governed the institution. She would have lived in the women’s section of the workhouse, separated from the men, in a space designed not for comfort, but for control and discipline.

Margarita’s daily existence would have been a series of monotonous tasks. Upon arrival, she would have passed through the porter's lodge and been assigned to the receiving or probationary wards. There, she would have undergone an initial period of assessment, which might have been stressful and degrading. After this period, she would have been assigned to one of the main wards, where she would sleep in a narrow bed, often alongside other women in similar circumstances. Privacy was scarce, and the communal living conditions meant that personal space and moments of solitude were virtually nonexistent.

Her days would have been filled with work, and the laundry would have been a primary site of labor for women like Margarita. The laundry contained thirty-two tubs, where inmates scrubbed clothes for the entire institution. Margarita would have worked long hours at this task, bending over the tubs, rubbing clothes in harsh soaps, the smell of wet fabric and chemicals in the air. The work was exhausting, and the conditions were often grim, but it was one of the few places where women could learn a skill that might provide a modicum of independence, should they ever leave the workhouse.

Meals were taken in the large 400-seat dining hall, where silence and strict order prevailed. Margarita would have sat with the other female inmates, eating the simple, utilitarian meals provided by the institution. These meals were designed to sustain, not to nourish the soul. Above the dining hall, the chapel offered a space for religious observance, where inmates like Margarita were expected to attend services. The chapel, with its high ceiling and its ecclesiastical armchair carved by a 66-year-old male inmate, was a reminder of the workhouse’s religious mandate. Though the space might have offered comfort, it also served to remind Margarita of her place within the strict social hierarchy of the institution.

Behind the main building, on the women’s side, Margarita would have worked in the laundry or perhaps assisted in the kitchen or bakehouse. The kitchen prepared the food for the inmates, while the bakehouse made bread, including six-ounce loaves for Margarita and her fellow inmates, and four-pound loaves for the outdoor poor of the union. Even here, in the kitchen or bakery, Margarita’s work would have been strictly supervised, with little room for creativity or personal expression. Everything was about function, survival, and conformity.

The infirmary, located in the southern part of the site, was a separate area that could have been both a source of fear and care. If Margarita had fallen ill, she would have been admitted to one of the many wards, where she would be treated with the same impersonal efficiency that marked the workhouse as a whole. The infirmary contained 166 beds, divided into various wards for the sick, elderly, and vulnerable, with special spaces for children and vagrants. Though medical care was available, it was likely basic, and the infirmary was a place that many tried to avoid unless absolutely necessary.

Margarita’s life in 1901 would have been a mixture of hard labor, religious observance, and moments of introspection. Though she may have had no direct contact with the men in the workhouse, there would have been an unspoken sense of separation from the outside world. The sense of isolation would have been palpable, with the workhouse serving as both a refuge and a prison, offering survival at the cost of personal freedom. Inmates had no choice but to live by the rules of the institution, and those who tried to resist were often punished or removed from the system altogether.

Yet, even in these harsh conditions, small acts of rebellion or solidarity could occur. Margarita, like many women, may have found comfort in the camaraderie of fellow inmates, or in the moments of quiet within the chapel, where she could reflect on her life and the circumstances that had brought her to the workhouse. The workhouse, though often seen as a place of last resort, also represented survival, a harsh and unforgiving environment where the only way forward was through sheer endurance.

The life of a female inmate like Margarita would have been defined by the relentless rhythm of the workhouse: the work, the meals, the chapel, and the heavy surveillance. It was a place where every action, no matter how small, was governed by the rules of the institution. Yet, in this stark world, Margarita’s resilience would have allowed her to persist, even if only in the quiet acts of survival that marked each passing day. The Woolwich Union workhouse was not just a place of labor, but one where people like Margarita could carve out a fragile, fleeting sense of identity, a sense of self amid the dehumanizing system that surrounded them.

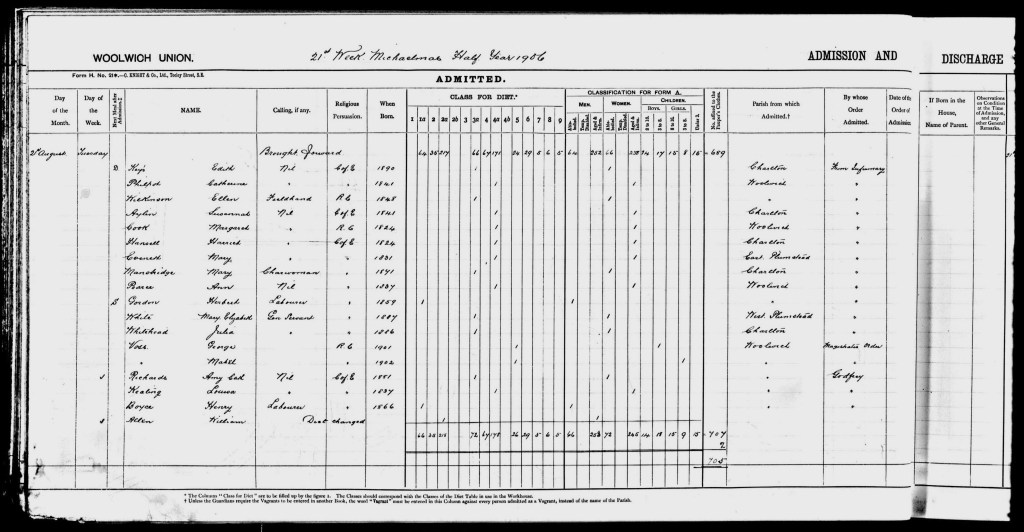

Margarita, at the age of 84, found herself once again seeking refuge at the Union Workhouse in Woolwich, Kent, on Tuesday, the 21st of August, 1906. Her admission document, now a silent testament to her life, notes that she was born in 1824.

Margarita, a Roman Catholic, had no formal occupation listed. She came from Woolwich, a place that had been both home and, at times, a reminder of her struggles. The document also notes that she was admitted by the infirmary, a sign of the vulnerability she had reached at this late stage in her life. It paints a picture of a woman who, despite her age, was still finding her way through a world that offered little support for those like her.

Margarita’s return to the workhouse must have been filled with both resignation and necessity. The workhouse, though a place of care, was also a reminder of the hardships she had endured over the years. To be admitted to the infirmary at this stage in her life was no small thing, it meant that her health had likely deteriorated, and her once-steady life had come to a point where she could no longer rely on her strength or independence.

Yet, despite the challenges she faced, there was something deeply humbling about Margarita’s story. At 84, she had lived a long and, complex life. This document, though official and clinical in nature, represents the end of one chapter and the beginning of another, a chapter where care, compassion, and comfort, however limited, were the hopes that Margarita carried with her as she entered the workhouse once again. It’s a reminder that behind every record, every name, there is a story of endurance, and a life worth honouring with empathy and understanding.

Thankfully, after a brief stay, Margarita was discharged from the Woolwich Union Workhouse in Woolwich, Greenwich, Kent, on Tuesday, 11th September 1906. The fact that she was able to leave the workhouse, even at the age of 84, must have brought her some relief, though it’s hard to imagine the weight of the years she had already carried.

Her time there, spent under the care of the infirmary, had no doubt been difficult, but her discharge marked a hopeful turn. It’s important to remember that Margarita’s life was not defined by her time in the workhouse but by her resilience, strength, and capacity to continue moving forward, even when the path was uncertain. For her, returning to the workhouse likely wasn’t just a place of care, it was a place where the struggles of life had caught up with her, and where she was offered the only help available.

Her discharge in September 1906 was not just a release from the workhouse, but also a quiet victory, a sign that she had fought through yet another chapter of hardship. There’s something deeply human in that moment: Margarita, after enduring the frailty of age and health, still had the courage to face the world once more.

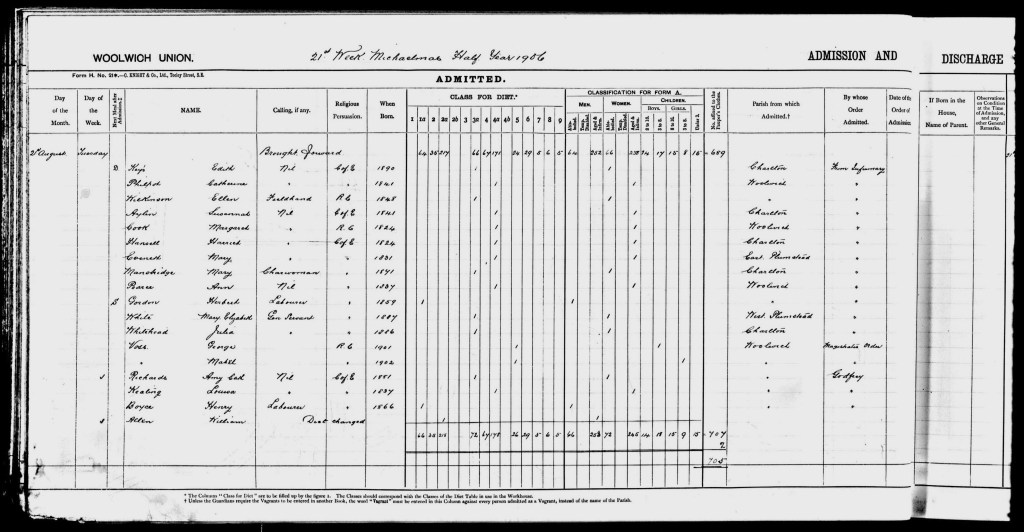

Sadly, this is where Margarita’s story comes to an end. On Thursday, the 26th of January, 1909, Margarita passed away at the Infirmary in Plumstead, London, England. She was 84 years old. Her death was attributed to the ravages of senile decay and bronchitis, conditions that had taken their toll on her body after many years of hardship.

Margarita’s passing marked the quiet conclusion of a long life filled with both struggle and survival. Despite the hardships she faced, the loss of independence, the cold confines of the workhouse, the illnesses of old age, she had endured more than most, carrying on as best as she could through the trials life had dealt her.

Her death was registered on the 2nd of February, 1909, by the superintendent of the infirmary, W. E. Boulton. In the records, Margarita’s name was listed as “Margaret,” a small but significant detail, perhaps a reflection of how even in the final moments, the world sometimes remembers us in a slightly different way than we remember ourselves. Her occupation was noted as “formerly a field hand in Woolwich,” an echo of her earlier life, one marked by physical labor and toil, but also by strength and perseverance.

Margarita’s life may have ended quietly, but it was a life that deserves to be remembered with compassion and respect. Behind the dates, the names, and the official documents, there was a woman who faced each day with resilience, who endured the harsh realities of her time, and who, despite all, left behind a legacy of quiet dignity.

The Infirmary in Plumstead, was the same Infirmary that had long served as the medical arm of the Woolwich Union workhouse, a place where many like Margarita found themselves in their final years, seeking care and shelter.

The Infirmary, originally part of the workhouse, was a stark, institutional building, its corridors echoing with the sound of footsteps and the whispers of those who had lived and worked there. By 1909, it would have been a place where the elderly, the sick, and those who had nowhere else to turn were housed. The rooms were sparse, the walls unadorned, offering little comfort. Patients like Margarita, particularly in her 80s, would have spent their days in bed, frail and fragile, while nurses and attendants moved from one to the next, performing their duties with the efficiency the institution demanded, though perhaps with little warmth.

The harsh, clinical environment of the Infirmary would have been difficult for someone like Margarita, who had likely experienced a lifetime of hard labor, personal struggle, and resilience. Senile decay and bronchitis, the causes of her death, were symptoms of a body worn down by time, illness, and the demands of her long life. At 84, Margarita would have been vulnerable and tired, likely spending her last days in the quiet, cold spaces of the Infirmary, under the watchful eye of the staff who administered to her needs.

It is difficult to imagine the isolation she must have felt.

In 1909, the Infirmary was not a place of personal care in the way we think of hospitals today. The focus was on the basics, food, shelter, and medical treatment for those who had little to no resources of their own. There would have been no modern comforts or the compassionate care we might expect in today’s healthcare settings. The patients were largely left to themselves, with some company from fellow inmates but little in the way of outside interaction or emotional support.

Margarita’s final moments were likely spent in a place that had been both a refuge and a reminder of the challenges of life. Her death from bronchitis and senile decay was the final chapter in a life that had been marked by hardship, survival, and, perhaps, the quiet resignation that comes when one has lived through so much. It’s poignant to think that the woman who had once been a field hand in Woolwich, working hard to make a living, would have spent her last days in the stark, cold wards of the Infirmary, with little more than the care of strangers around her.

Margarita’s passing would have been a quiet one, as so many were in that time. She passed away in a place that had been both a shelter and a reminder of society’s view of those in need. She was not alone in the Infirmary, for there were others like her, but the workhouse system was not built with emotional connection in mind, and many left it unnoticed.

The Infirmary where Margarita died would eventually become Saint Nicholas’ Hospital, a name that perhaps brought some hope or recognition to the institution, but the experiences of those like Margarita remained much the same until the hospital was further developed in the following decades. In World War Two, the hospital was severely damaged, like so many places, by bombings, and it was eventually closed in 1986 as part of an NHS rationalization plan. The site where Margarita spent her last days was redeveloped, but the memories of the institution linger, memories of lives like Margarita’s, whose quiet endurance through hardship deserves to be remembered and honored with the compassion and respect she perhaps did not receive in her final years.

Margarita’s story is one of resilience and endurance. She lived a long life, marked by struggles and strength, and though her final days were spent in a place of cold routine, her journey through life is a reminder of the human spirit’s capacity to survive, to continue on, even when the world offers little in return. Her passing, though quiet and humble, is still a story worth telling, one that should not be forgotten.

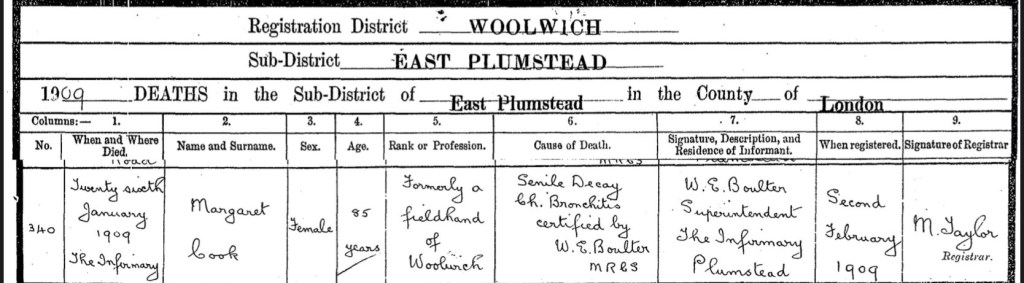

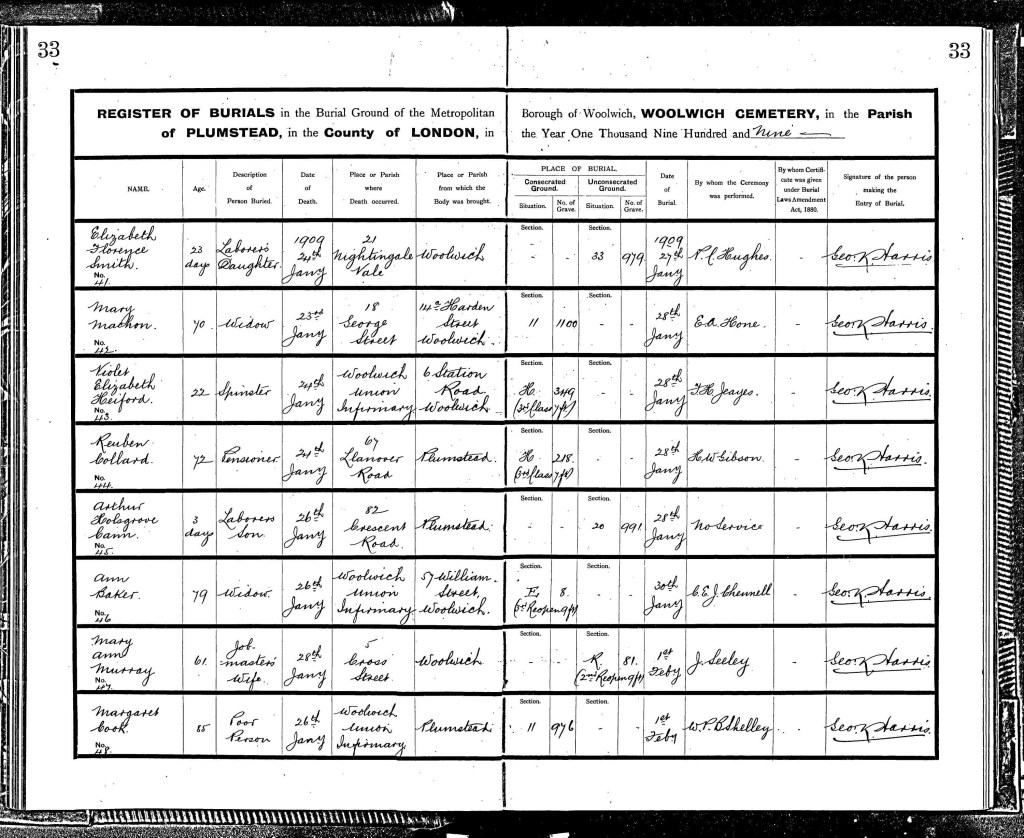

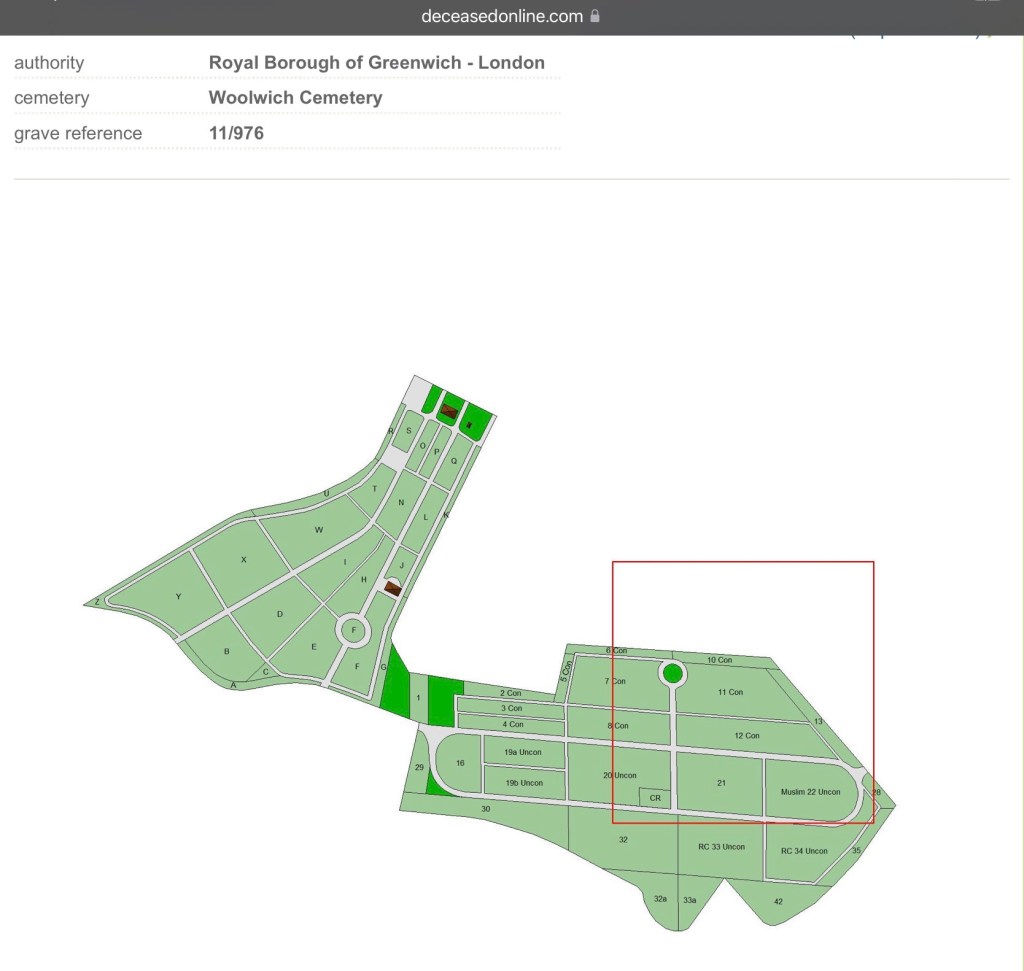

Margarita was laid to rest on Monday, the 1st of February, 1909, at Woolwich Cemetery in Greenwich, London, England. Her burial, as was often the case for those in the workhouse system, was a quiet, unremarkable affair, marked by the simplicity of the surroundings. Her final resting place was in grave reference 11/976, a grave that held not just Margarita but 13 other souls, buried together in an open grave. This shared burial reflected the realities of life in the workhouse, where the deceased, especially those who had lived through poverty and hardship, were often laid to rest in mass graves, a final resting place that offered no individual marker or personal recognition.

The fact that Margarita was buried alongside 13 others in an open grave speaks to the harshness of the circumstances in which she lived. It suggests a sense of anonymity, a life lived in quiet endurance without much attention or ceremony. The graves of those who passed within the workhouse system were often grouped together, their lives ending not with the dignity they deserved, but with the stark reality of institutional life.

While we can imagine that Margarita’s final moments were likely spent in relative solitude within the Infirmary, her burial in a shared grave would have been an even more profound moment of quiet anonymity. In a world that had little room for compassion or recognition for people like Margarita, her death and burial serve as a poignant reminder of the many lives that passed unnoticed, their struggles overshadowed by the indifference of the system that cared for them.

Yet, even in this simple, humble burial, there is a sense of the quiet resilience Margarita embodied. Though her name may have been one of many in the records, she was, without a doubt, a person who lived through hardship, who faced the challenges of her time with strength. And, though her life ended without ceremony, we remember her now with empathy and compassion, honoring her memory and the difficult journey she undertook until her very last days.

Woolwich Cemetery, located in the Royal Borough of Greenwich, London, comprises two adjacent burial grounds: the Old Cemetery and the New Cemetery. The Old Cemetery was established in 1856 by the Woolwich Burial Board on land that was formerly part of Plumstead Common. This 12-acre site was nearly full within 30 years, prompting the creation of the New Cemetery in 1885 on adjacent land to the east.

The Old Cemetery features an Early English style brick Anglican chapel, which remains a prominent structure on the site. The cemetery is characterized by its park-like appearance, with gravestones and memorials interspersed among mature trees such as cypresses, beeches, and Scots pines. Notably, the cemetery is the burial place of 120 victims of the Princess Alice disaster, a tragic event in 1878 when a pleasure steamer collided with another vessel on the River Thames, resulting in significant loss of life. A commemorative cross was erected in their memory.