Welcome to a captivating journey through time, where the veil of history lifts to reveal the rich tapestry of a life once lived. Together, let us delve into the fascinating story of James William Willats, my 4th Great Granduncle, a man whose life, though distant in years, remains ever vivid through the threads of family history. As we retrace his footsteps, from the wonder of his childhood to the poignant chapter of his marriage, we glimpse not only the world he knew but also the enduring legacy he left behind.

James William Willats was born in the heart of Westminster, London, England, a place where history and tradition thrived alongside the hum of daily life. It was an era when gas lamps cast a golden glow on cobblestone streets, and the echoes of horse-drawn carriages punctuated the air. Into this world of simple pleasures and endless possibilities, James arrived, cradled by a family bound by love, resilience, and a shared sense of purpose. Within this close-knit community, he was nurtured by values of hard work, compassion, and a deep connection to those around him.

In the stories of James’s childhood, one can almost hear the laughter shared with siblings, see the mischief in his young eyes, and feel the warmth of a household where bonds were cherished above all else. His early days, though lived in a time vastly different from ours, resonate with a timeless truth: that family is the bedrock upon which lives are built. The Willats family’s unwavering support undoubtedly shaped James into the man he would become, instilling in him the courage to face life’s challenges and the generosity to embrace its joys.

Family history is more than names and dates on a page—it is the beating heart of our identity, the bridge that connects us to those who came before. As I trace the life of James William Willats, I find myself not merely recounting the events of his time but also standing shoulder to shoulder with him, drawing strength from his journey and finding echoes of his spirit in my own. His story reminds me that the lives of our ancestors are not confined to the past, they ripple through generations, influencing who we are and who we aspire to be.

James’s life was filled with milestones, but none as transformative as the moment he exchanged vows in marriage. This union was not merely the joining of two individuals but the creation of a new chapter in the family’s narrative, a chapter that would carry forward the traditions, hopes, and dreams of generations past. In a time when marriage was a partnership built on shared aspirations and mutual respect, James’s commitment would have been both a celebration and a solemn promise.

As I share his story, I am struck by how much our family owes to the perseverance and love of those who walked before us. Their choices, sacrifices, and triumphs have shaped our present and given us a foundation upon which to build our future. James’s life, with its joys and challenges, serves as a poignant reminder of the enduring importance of family, a bond that transcends time and space.

I invite you to journey back with me to the world of James William Willats. Through his life, may we discover not only the richness of his story but also a renewed appreciation for the ties that bind us all. His footsteps may have faded, but his legacy endures, woven into the fabric of who we are. Let his story inspire us to cherish our own family histories and to carry forward the love and resilience that connect us across the ages.

So, without further ado, I give you,

The Life Of James William Willats

1841 - 1922,

From Upbringing To Marriage,

Through Documentation.

Welcome back to the year 1841, London, England. The city teems with the clamor of a rapidly transforming society, a blend of grandeur and grit at the heart of the Victorian era. Queen Victoria, young and resolute, reigns as monarch, having ascended the throne just four years prior in 1837. The government, meanwhile, sees significant change in this very year. The Conservative Sir Robert Peel assumes office as Prime Minister after the Whig Lord Melbourne, marking a shift in the political winds. Parliament is defined by debates over economic reform and burgeoning industrialization.

Life in 1841 reflects the contrasting fortunes of Britain's social classes. The aristocracy continues to revel in inherited wealth, while the middle class enjoys growing prosperity fueled by commerce and industry. For the working class and the poor, however, life is a daily struggle, defined by long hours in factories, meager wages, and precarious living conditions. The Poor Law Amendment Act of 1834 remains a source of contention, as it has pushed many into the feared workhouses.

Fashion in 1841 captures the elegance of the early Victorian style. Women wear dresses with wide skirts supported by petticoats, tight bodices, and long sleeves, often accessorized with bonnets and gloves. Men favor tailored frock coats, waistcoats, and cravats, with top hats completing the ensemble. Despite their elegance, clothing styles often underscore the divide between the classes, as the poor make do with hand-me-downs and patched garments.

Transportation is a tale of progress. The railway boom is in full swing, with steam trains becoming the most efficient way to travel long distances. London's streets remain dominated by horse-drawn omnibuses and carriages, but they are also choked with dirt and noise. Steamships revolutionize river and sea travel, connecting Britain more effectively to its empire.

Energy, atmosphere, and heating in 1841 are primitive by modern standards but groundbreaking for the time. Coal is the lifeblood of industry and domestic heating, filling the city air with soot and smog. Gas lighting, introduced in the early 19th century, illuminates streets, homes, and theaters, though oil lamps and candles are still common in poorer households.

Sanitation is rudimentary and a growing concern. The infamous Thames River serves as both a water source and a dumping ground for waste, contributing to disease outbreaks such as cholera. Efforts to address these issues are minimal, though calls for reform are rising. Food for the wealthy is elaborate, featuring multi-course meals and delicacies like roast meats and puddings. The working class and poor subsist on bread, potatoes, and cheap cuts of meat, with hunger a persistent threat.

Entertainment in 1841 is varied, from grand theater productions in Covent Garden to music halls, public lectures, and penny dreadfuls, cheap, sensationalist literature. Parks like Hyde Park offer respite from the crowded streets, and fairs bring moments of joy to all classes. Gossip thrives in the salons of the upper classes and the crowded pubs of the working poor, where tales of scandal, politics, and royal intrigue swirl.

The environment, unfortunately, suffers under the weight of industrial progress. Smoke stacks belch soot, rivers are polluted, and green spaces are increasingly encroached upon by urban expansion. The stark contrast between the manicured gardens of the wealthy and the grime of the slums epitomizes this imbalance.

The 1841 census, a notable historical event, is the first in Britain to collect detailed information about individuals, including their names, ages, occupations, and residences. It paints a picture of a burgeoning population, with London already the world's largest city, teeming with over two million souls.

The rich, or upper class, lives in opulent townhouses or country estates, enjoying leisure and influence. The working class occupies cramped tenements, balancing modest incomes against rising living costs, while the poor often inhabit squalid slums or rely on the dreaded workhouses. This stark stratification defines much of London’s social landscape.

Historically, 1841 is a year of change and tension. The British Empire continues to expand its reach, and the Opium Wars with China underscore its aggressive economic policies. Domestically, the year heralds the dawn of the Victorian age’s defining characteristics: industrial innovation, social reform, and cultural transformation. Amid the smoke and turmoil, London is a city alive with ambition and contradiction, setting the stage for the decades to come.

For us, the year 1841 holds special significance, it’s the year James William Willats was born. He was the sixth child of George John Willats and Charlotte Woollet Willats (née Carter).

James came into the world on a Saturday evening, July 17, 1841, at their family home: 3 Meard Street, Saint Anne, Westminster, Middlesex, England.

His mother, Charlotte, registered his birth on August 24, 1841, at Strand. On the registration, Charlotte listed George’s occupation as a "Craver" and confirmed their address as 3 Meard Street.

Somewhere in my notes, I’ve jotted down that James was born at 6 p.m., though I can’t for the life of me recall where I got that detail from. It feels like such a small thing, but it’s one of those pieces of the story that makes his arrival feel all the more real to me.

Meard Street is more than just a street in Soho, London—it’s the heart of the Willats family home and holds a deeply personal significance. This historic street, running roughly east-northeast to west-southwest, links Wardour Street to the west and Dean Street to the east. Its unique layout, with a slight bend in the middle dividing it into a pedestrianized western half and a narrow, single-lane eastern half, gives it a charm that’s hard to replicate.

Named after John Meard, the younger, a highly skilled carpenter and later an esquire. Meard Street was developed in the 1720s and 1730s. The houses he designed and built still stand today, making this one of London’s rare surviving Georgian streets, steeped in nearly three centuries of history.

These homes, including Number 3, where the Willats family lived, are a quintessential example of Georgian architecture. This celebrated style, spanning from 1713 to 1830, is often regarded as the pinnacle of English design. John Meard, known as one of the most talented carpenters of his era, played a pivotal role in its creation. Carpentry was a vital trade in those times, with wood being the foundation of most construction. In 1735, Meard became Master of the Worshipful Company of Carpenters and even collaborated with Sir Christopher Wren on St. Paul’s Cathedral and other iconic churches.

The terrace of houses at Numbers 1, 3, 5, and 7 Meard Street stands as a testament to his craft. These four-story homes, complete with basements, retain their original Georgian features: a dog-legged staircase, three evenly spaced front windows, wide piers between each house, brown stock bricks, stone sills, and double-hung sash windows. Number 3, specifically, became the Willats family’s cherished home, a place of love and life, rooted in history.

Meard Street has always been vibrant and full of character. Throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, it was home to a variety of fascinating people, from musicians, composers, and writers to architects, enamel engravers, painters, artists, and even a chess player. By the 20th century, the street had retained its prestige, becoming home to both the well-to-do and those connected to Soho’s notorious nightlife, both legitimate and illicit.

Beyond the historic houses, Meard Street boasts a unique and playful landmark: the “7 Noses of Soho,” one of which can be found here. It’s a quirky touch that adds to the street’s distinctive charm.

For the Willats family, however, Meard Street is much more than just a historic location. It’s the very heart of their story, a place where history, artistry, and family life have been woven together in the most meaningful way.

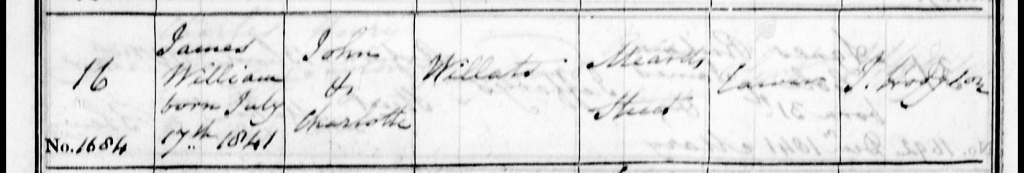

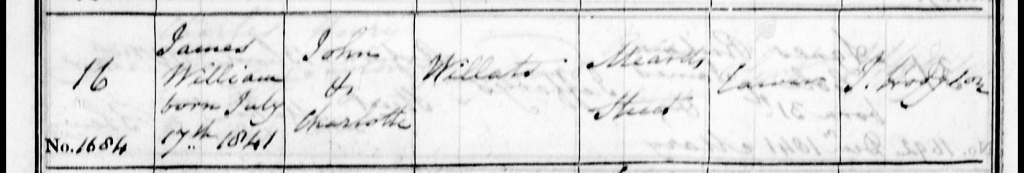

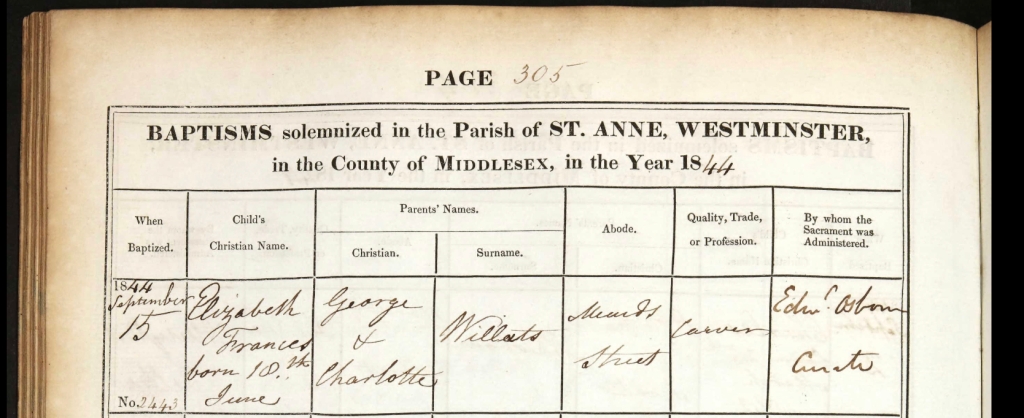

On a crisp winter Sunday, January 16, 1842, George and Charlotte Willats brought their infant son, James William Willats, to be baptized at the beautiful St. Anne’s Church in Westminster, London. It must have been a significant day for the young family, a moment to officially welcome their baby boy into the world and their faith.

Interestingly, when the details were recorded, George gave his name as "John," a small quirk that adds a touch of mystery or perhaps practicality to the family’s story. His occupation was listed as a Craver, reflecting his skill in carving and craftsmanship, and their address as Meard Street, the cherished heart of their home.

The thought of them standing in that historic church, with its timeless architecture and spiritual warmth, celebrating James’s baptism, paints a vivid picture of their lives in that moment, a blend of tradition, family pride, and perhaps even a touch of nervous excitement as they stepped into the next chapter of their story.

St. Anne’s Church stands as a historic beacon in the heart of Soho, London, serving the Church of England parish of St. Anne. Consecrated on March 21, 1686, by Bishop Henry Compton, the church became the centerpiece of the newly created civil and ecclesiastical parish of St. Anne. This parish was formed from part of the larger parish of St. Martin in the Fields to accommodate Soho’s growing population during the late 17th century.

Nestled within the vibrant and ever-changing neighborhood of Soho, St. Anne’s Church has long been a place of worship, reflection, and community. The church operates under the Deanery of Westminster (St. Margaret) within the Diocese of London. Over its centuries of existence, it has borne witness to the ebb and flow of London’s history, from the bustling Georgian and Victorian eras to the challenges of the 20th century.

The churchyard, which once fully surrounded the church, holds its own fascinating history. During its early years, the churchyard served as a burial ground, with countless stories of Soho’s residents interwoven with its soil. Over time, as urban development reshaped the area, much of the churchyard transitioned into St. Anne’s Gardens, a serene public park that remains a haven of green space amidst Soho’s energetic streets. Visitors can access the gardens from the Shaftesbury Avenue end of Wardour Street, while the church itself is reached through a gate at the Dean Street end.

St. Anne’s has played a pivotal role in the spiritual life of Soho. In the era of compulsory church attendance, the parish expanded, establishing new churches dedicated to Saints Thomas and Peter to serve the growing population. However, by the mid-20th century, changing social patterns and urban consolidation led to these parishes reconsolidating back to St. Anne’s in 1945, reaffirming its status as the spiritual anchor of the community.

The church itself is a beautiful example of post-Restoration architecture. Though it suffered damage during World War II, including the loss of its roof and much of its interior, the surviving west tower stands as a powerful symbol of resilience. This historic tower is a reminder of the church’s original grandeur and remains a cherished landmark in the area.

Today, St. Anne’s Church and its gardens continue to offer a place of quiet reflection and community connection. Its historic churchyard, transformed into a public park, provides a peaceful retreat in one of London’s most dynamic neighborhoods.

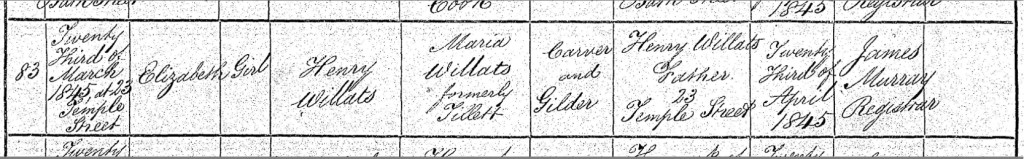

Elizabeth Frances Willats, James’s sister, was born on Tuesday, June 18, 1844, in Middlesex, England. Her birth, however, was a bit of a puzzle to track down. I spent quite some time poring over the records, trying to find the right match, but nothing seemed to fit perfectly.

After much searching, I came across one potential birth index entry that seemed close, but there was a twist. The mother’s maiden name was listed as Tillett, not Carter, which gave me pause. Their mother, Charlotte Woollet Carter, had always been the name I knew. My theory was that perhaps Charlotte had given her maiden name, Woollet, but it was mistakenly transcribed as Tillett. But there was another complication: the year was off by one, making me hesitant to jump to conclusions.

Despite my doubts, I decided to order the digital image of the certificate, hoping it might hold the answers I was looking for. Unfortunately, when it arrived, I could see it wasn’t the right Elizabeth after all. Still, I’ve included the image of that certificate below, just in case it helps anyone else in their own family research journey.

Sometimes these little mysteries are part of the process, and I’m sure there are more surprises ahead as I continue to piece together our family’s story.

On Sunday, September 15, 1844, George and Charlotte Willats brought their baby girl, Elizabeth Frances Willats, to be baptized at the parish church of St. Anne in Soho, Westminster, London. It must have been a joyous occasion for the family as they celebrated this important milestone in Elizabeth’s early life.

In the church records, Elizabeth’s birth date was listed as June 18th, a detail that helps anchor her place in the family’s timeline. George’s occupation was given as “Carver,” reflecting his skill in the craft, and the family’s home was listed as Meard Street, their cherished address in the heart of Soho.

The Willats family faced an unbearable sorrow when James’s beloved eight-year-old sister, Sophia Mary Ann Willats, passed away on Tuesday, March 4, 1846, at The Middlesex Hospital in All Souls, St. Marylebone, Middlesex. Sophia’s death was the result of a heartbreaking sequence of events: after a fall in the street, she developed an abscess in her shoulder, which tragically led to pericarditis just 18 days later.

In those painful moments, the family must have been filled with grief and helplessness as they watched their precious child suffer. The medical professional, J. Walleye, Corona, of Number 35 Bedford Square, was with Sophia during her final days and registered her death at St. Marylebone on Monday, March 13, 1848. The death was recorded under the name “Mary Ann Willats,” a slight discrepancy, but one that perhaps reflected the confusion and distress of such a devastating time.

Sophia’s loss would have been felt deeply by her family, especially by James, who would have lost his sister far too soon. It is a reminder of the fragility of life, and the deep love that binds a family even in the hardest of times. Their pain, while impossible to fully understand from our distance, is something we can hold in our hearts as we reflect on their story.

On Sunday, March 8, 1846, James, his parents George and Charlotte, and the rest of the family, laid their precious Sophia to rest at St. James Church in Westminster, London. The pain of losing such a young soul would have weighed heavily on their hearts as they made their way to the church, seeking some form of solace amid their grief.

Sophia’s name was recorded as “Mary Ann Willatts” in the church’s burial register, a gentle reminder of her full name, though perhaps a reflection of the sorrowful circumstances that marked those final days. The family’s address was listed as Meard’s Street, St. Anne’s, their home and the place where memories of Sophia would forever remain etched in their hearts.

In that moment, the Willats family would have come together, united in their love for Sophia, as they said their final goodbyes. While the pain of loss can never truly be healed, their bond as a family and the love they shared would have been a lasting comfort during such an unimaginably difficult time.

St. James’s Church, Piccadilly, also known as St. James’s Church, Westminster, or St. James-in-the-Fields, is an Anglican church located in the heart of London, on Piccadilly. Designed by the famous architect Sir Christopher Wren, the church was built between 1676 and 1684, making it a significant example of Wren’s architectural genius during the post-Restoration period.

The church is constructed from red brick, with striking Portland stone dressings, giving it a distinctive and enduring appearance. Inside, the church is known for its stunning galleries, which surround the nave on three sides and are supported by square pillars. The nave itself boasts a beautiful barrel-vaulted ceiling, which is held up by elegant Corinthian columns.

One of the most remarkable features of the interior is the carved marble font and the limewood reredos, both created by the celebrated carver Grinling Gibbons. Gibbons was famous for his intricate and detailed wood and stone carvings, and his works in St. James’s Church stand as exceptional examples of his craft.

In 1902, a notable addition was made to the church: an outdoor pulpit was installed on the north wall. Designed by Temple Moore and carved by Laurence Arthur Turner, this pulpit has its own historical significance. Though it was damaged during the bombing raids of 1940, it was later restored along with the rest of the church’s structure during post-war repairs.

St. James’s Church has remained a central place of worship and reflection in London, with a rich history that has included major events and gatherings throughout the centuries. The church’s architectural beauty and its connections to important historical figures make it a cherished landmark in the city.

Just over a year after the heartbreak of losing Sophia, the Willats family had a much-needed reason to smile once again. On Saturday, June 19, 1847, James’s sister, Jenny Eliza Willats, was born in Middlesex, England. Her arrival must have brought some light into the family’s life, a reminder of the joy that can still bloom even after great loss.

Unfortunately, I’ve been unable to find a birth index entry for Jenny, or at least one that matches her exact details. However, we are fortunate that her baptism record gives us her birth date, along with their address, which strongly suggests that Jenny was born at their home on Meard Street, Soho, Westminster, likely the same place where the family had weathered the trials of previous months.

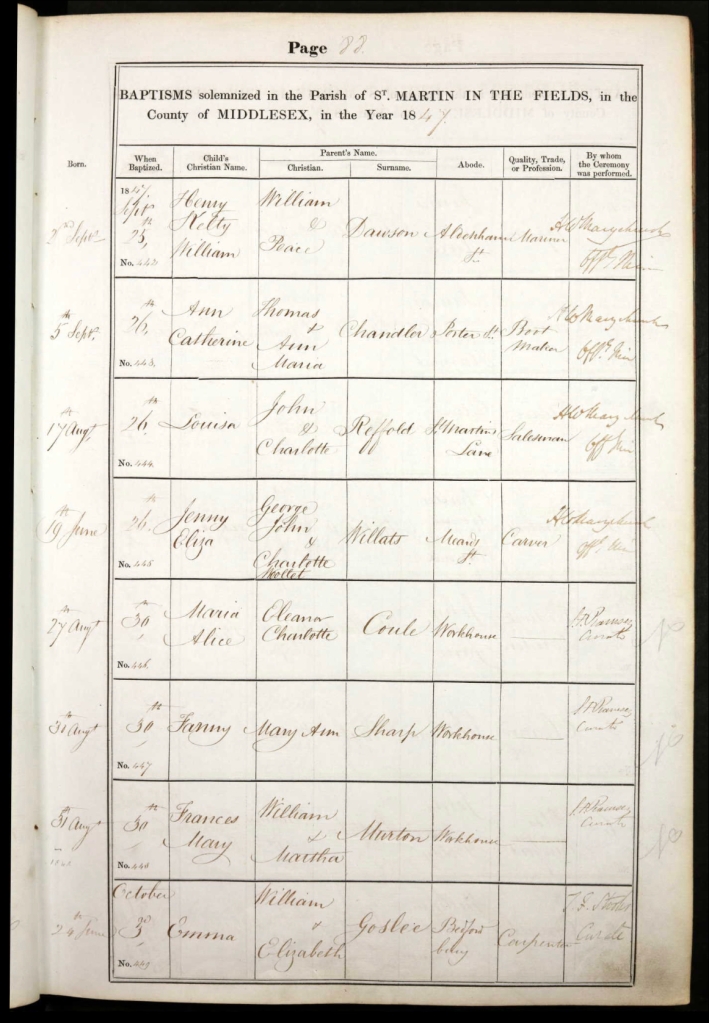

James, along with his parents George and Charlotte, brought Jenny to be baptized on Sunday, September 26, 1847, at St. Martin-in-the-Fields, Westminster. It must have been a beautiful day for the family as they gathered in that iconic church to mark Jenny’s entry into the community. In the baptismal records, George’s occupation is listed as "Craver," and their home is again noted as Meard Street, a place that had become synonymous with their family’s story.

Jenny’s arrival was a hopeful new chapter for the Willats family, bringing them a bit of peace after their earlier grief.

Jumping forward to the year 1851. The year was one of great change and historical moments. Queen Victoria reigned over Britain, and the country witnessed significant political shifts with Lord John Russell serving as Prime Minister. Foreign Secretary Henry John Temple, 3rd Viscount Palmerston, held the post until December, when Granville Leveson-Gower, 2nd Earl Granville, took over. This was also the 15th Parliament.

It was a year of innovation as well, sculptor Frederick Scott Archer publicly unveiled the wet plate collodion photographic process, forever changing the art of photography. Meanwhile, the Royal School of Mines was established, providing a new avenue for education in science and industry.

In the world of global events, exiled Hungarian regent-president Lajos Kossuth arrived in Southampton, later spending eight years in England after touring the UK and the United States. On the streets, changes were being made for the working class with the Labouring Classes Lodging Houses Act, though it would see limited use. Even the world of leisure was affected, with the introduction of the card game "Happy Families" by Jaques of London.

But it wasn’t all progress, tragedy struck when an explosion at the Victoria Pit colliery in Nitshill claimed the lives of 61 men and boys.

In other news, Bell's whisky was blended for the first time, and Donaldson's Hospital opened in Edinburgh, dedicated to the education of deaf children.

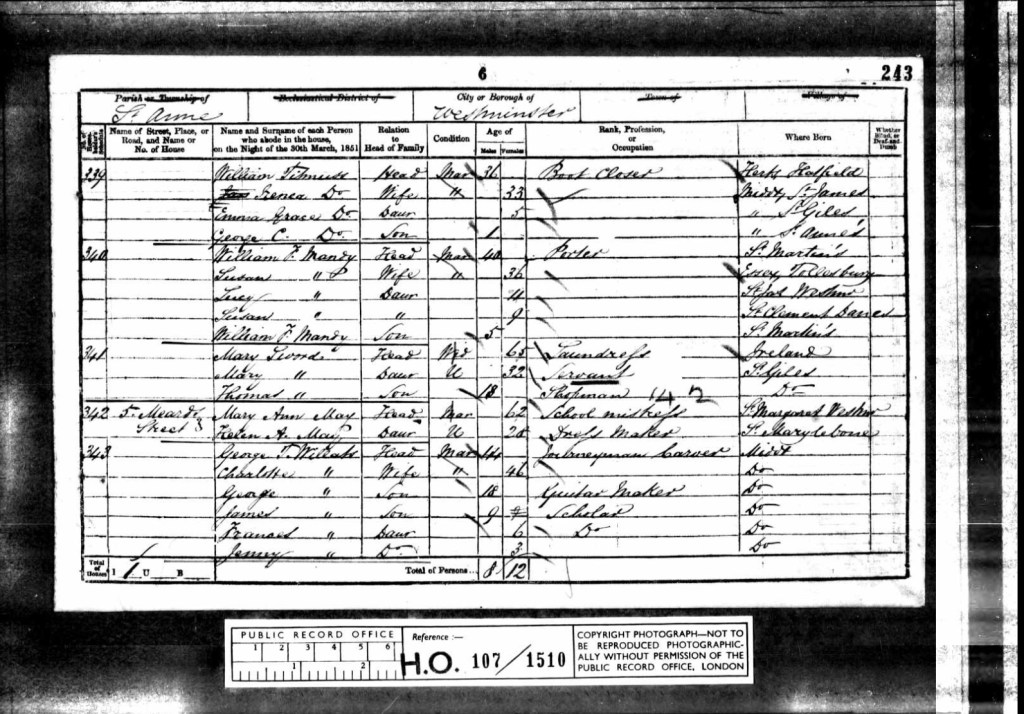

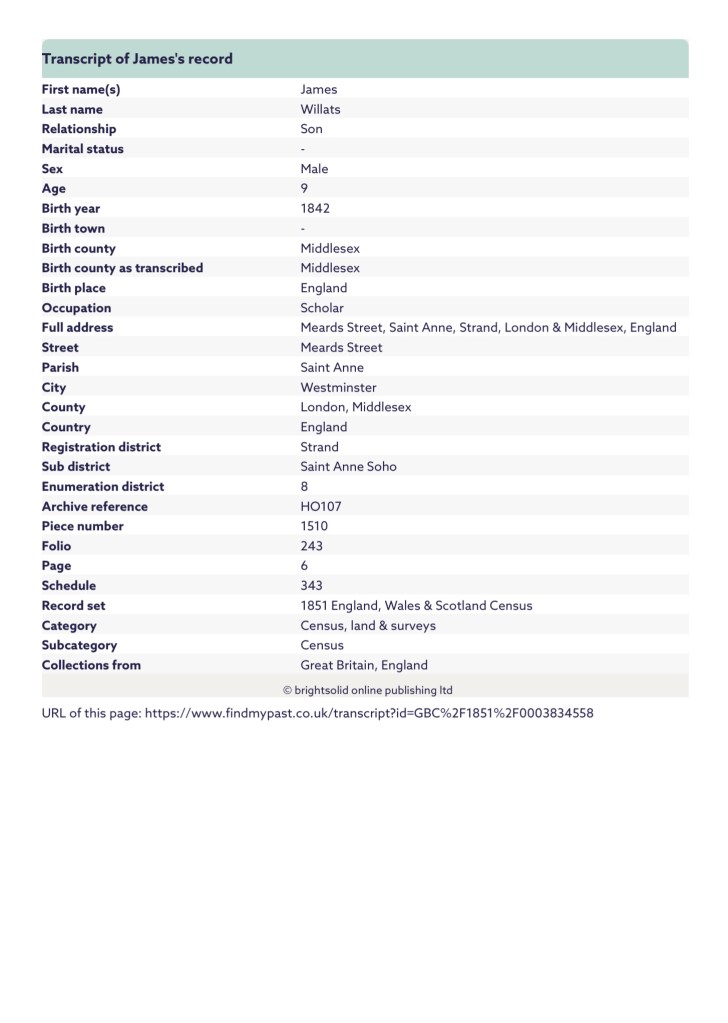

Amid these major events, on Sunday, March 30, 1851, the census was taken, and it revealed that James, along with his parents Charlotte and George John, and his siblings George, Frances, and Jenny, were living at Meard Street, Saint Anne, Strand, London, Middlesex. George John, James's father, was working as a journeyman carver, continuing the family tradition of craftsmanship.

The Willats family was part of this changing world, making their way through the ups and downs of daily life while contributing to the story of London in the mid-19th century.

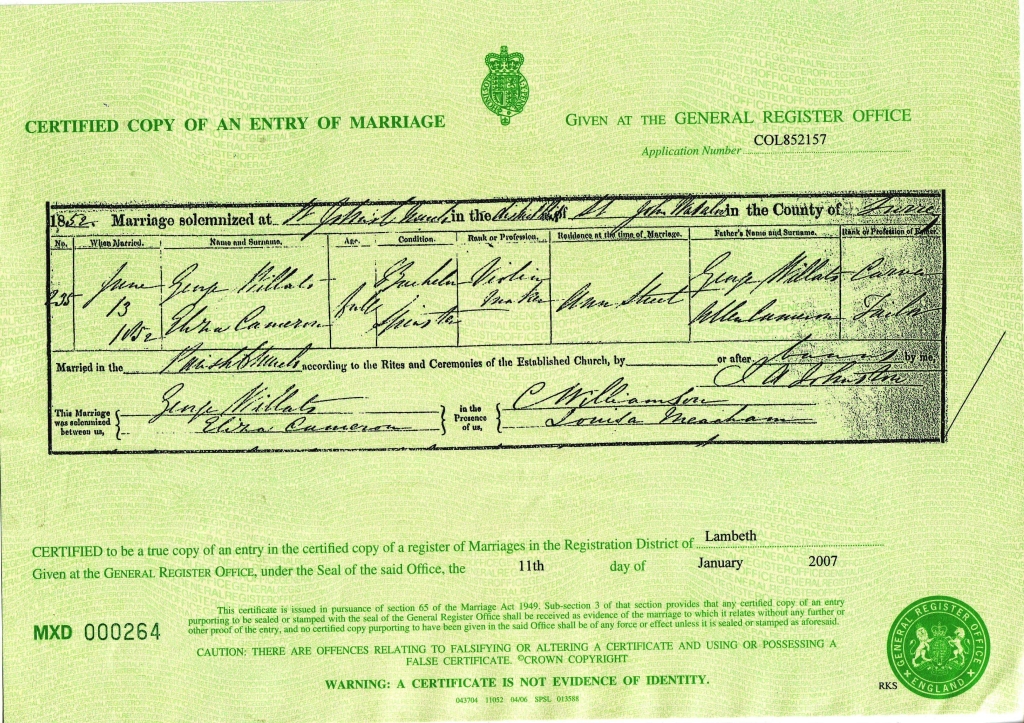

On the 13th of June, 1852, James’s brother, George John Willats—my 4th great-grandfather—married a woman named Eliza Cameron at St. John’s Church in Waterloo, Lambeth, Surrey. St. John’s, an Anglican Greek Revival church built between 1822 and 1824, was designed by Francis Octavius Bedford. This beautiful church, dedicated to St. John the Evangelist, forms a united benefice with St. Andrew’s, Short Street, and stands as a symbol of history in South London.

Both George and Eliza were of full age, unmarried, and living at Ann Street at the time of their marriage. George was working as a violin maker—a skilled craft that reflected his artistic nature—and Eliza’s father was employed as a tailor. George’s father, George Willats, continued his trade as a carver, a craft passed down through generations.

The witnesses to their marriage were C. Williamson and Louisa Beacham, whose names now hold a special place in the family history. This union between George and Eliza marked the beginning of a new chapter in the Willats family, one filled with promise and love.

St. John’s Church, Waterloo, is a striking Anglican Greek Revival church located in South London. Built between 1822 and 1824, it was designed by the talented Francis Octavius Bedford. The church is dedicated to St. John the Evangelist, and along with St. Andrew's, Short Street, it forms a united benefice.

Nestled in the heart of Waterloo, the church stands opposite the London IMAX, close to Waterloo Station and the Waterloo campus of King's College London. The location places it in one of the most vibrant and historic areas of London.

The church’s origins date back to 1818, a time when the country was entering a period of peace after the Napoleonic Wars, and the population was expanding rapidly. To accommodate the growing population, Parliament allocated up to a million pounds for the building of additional churches, particularly in populous parishes. The Commissioners for Building New Churches allocated £64,000 in 1822 specifically for Lambeth, and it was decided that a new church would be built near the Waterloo Bridge approach. A piece of land on the east side of the road was purchased from the Archbishop of Canterbury and his lessees, Gilbert East and a man named Anderson.

Bedford, a respected Greek scholar and antiquarian, was commissioned to design the new church. He had already designed three other churches for the Commissioners, including St. George’s in Camberwell, St. Luke’s in West Norwood, and Holy Trinity in Newington. All of these churches reflected Bedford’s deep admiration for Greek architectural styles. However, the Greek Revival style, which was gaining popularity during Bedford’s time, was starting to be replaced by Gothic architecture. Bedford’s churches, including St. John’s, were often criticized by contemporaries, but St. John’s gained more critical appreciation, especially due to its fine spire. The spire used classical details to create a more traditional English parish church shape, which helped it stand out and gain a more favorable reception.

Unfortunately, there’s a significant gap in James’s life story that we haven’t yet been able to fill. After his early years, there’s little to no information about him until the year 1861. One particular record we’d hoped to find him in is the 1861 census, which was taken on Sunday, April 7th, 1861. However, despite our efforts, there’s currently no sign of James in that census, leaving us with more questions than answers during this time in his life.

This missing piece of the puzzle continues to be a source of curiosity and frustration, but it’s also a reminder of how certain moments in family history can remain elusive, no matter how much we wish for clarity. Hopefully, as time goes on, more records will surface to help us bridge this gap.

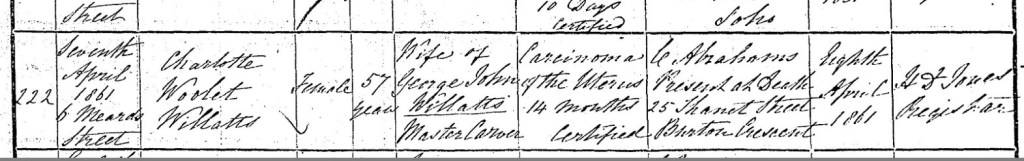

With heavy hearts, we remember the passing of James’s mother, Charlotte Woollet Willats, née Carter. Charlotte, the devoted wife of George John Willats, a master carver, and the loving mother of eight children, passed away on the 7th of April, 1861, at the age of 58.

Her death came after a long and difficult battle with cancer of the uterus, which she had endured for 14 months. Charlotte’s passing at their home, number 6 Meard Street, Soho, Westminster, left a profound void in the Willats family. Her strength and nurturing love were the foundation of her home, and her loss was deeply felt by all who knew her.

G. Abraham was present at her passing and, with great care, registered her death the following day, April 8th, 1861. Though the pain of losing her was unimaginable, Charlotte’s legacy as a mother, wife, and pillar of the family lives on in the hearts of those she loved.

James’s mum, Charlotte Woollet Willats, née Carter, was finally laid to rest on Friday, the 12th of April, 1861, at St Pancras Cemetery, Camden, London. She was buried in grave Z10/72, alongside 17 others, a somber but meaningful resting place.

Among those interred with her were Henry Edward Deacon, Mary Randall, Mary Ann Rachel Toure, John Smallwood, and Emily Fossett, who had been buried on the 12th of February, 1880. John Mayhew, Ann Smith, and John Union Parsler also share this resting place, with their burials occurring in early 1880. Sarah Ewens and Emma Arnold were laid to rest on the 15th of April, 1861, and Isaac Skelton and Rachel Jones on the 14th of April. Mary Holloway was buried on the 13th of April, and Emily Greene, Edward Bush, and Henry Tudor were all laid to rest on the 11th of April.

Though Charlotte's life was sadly cut short, her memory continues to live on, resting among those she shares this sacred space with. Her family, friends, and descendants will forever cherish the legacy she left behind.

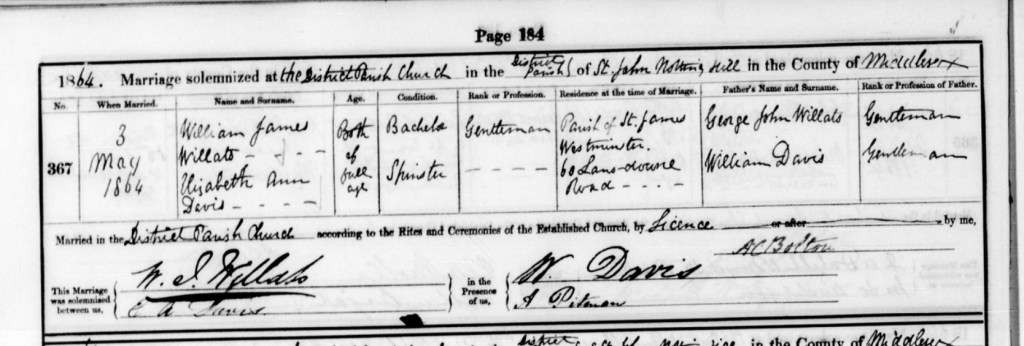

A few years later, Bachelor, James aka William James Willats, a Gentleman, married Spinster, Elizabeth Ann Davis on Tuesday the 3rd May 1864, at St. John's, Notting-Hill, Middlesex, England.

Their witnesses were, W. Davis and A. Pitman.

William gave is abode as, Parish of St. James, Westminster and Elizabeth gave hers as, 60 Landsdowne Road.

They gave their fathers names and occupations as, George John Willats, a Gentleman and William Davis, a Gentleman.

Though James’s beloved mother, Charlotte Woollet Willats, had passed away just a few years prior, her memory and influence surely lingered in his heart. Her love, care, and legacy would forever be a part of James’s journey, as he embarked on this new chapter in his life with Elizabeth by his side.

St. John’s Church in Notting Hill holds a rich history, serving as a Victorian Anglican church that was built in 1845 in Lansdowne Crescent, Notting Hill, London. Designed by the architects John Hargrave Stevens and George Alexander, it was constructed in the striking Victorian Gothic style that was so popular in the era. Dedicated to St. John the Evangelist, the church was originally intended as the heart of the Ladbroke Estate, a newly developing area in the mid-nineteenth century.

At that time, the Ladbroke Estate aimed to attract upper- and upper-middle-class residents to the once-rural neighbourhood in the western suburbs of London. As such, St. John's Church became an integral part of this evolving community, providing a sense of permanence and spiritual connection for those who settled in the area.

James William Willats, as described in his records, was listed as a "Gentleman" in Victorian London, a title that carried with it a world of privilege, expectations, and responsibilities. Life as a Victorian gentleman was far from simple; it was a complex balancing act of maintaining one’s social standing while adhering to a strict code of behavior and conduct.

For James, this meant belonging to the upper or middle class, a status that granted him certain privileges but also imposed many duties. Education was a cornerstone of his status. A well-educated gentleman was expected to be well-versed in classical subjects, literature, languages, history, and the arts, and education often took place at prestigious institutions like Oxford or Cambridge. His education would have marked him as refined and distinguished in a society that prized intellectual achievement.

Being a gentleman was about more than just knowledge; it was also about appearances. James would have dressed in tailored suits, waistcoats, top hats, and cravats, as fashion was an important reflection of his status. A well-dressed man in Victorian society communicated his place in the world and his ability to adhere to the social expectations of the time.

The social norms of the period were rigid, and etiquette was paramount. A gentleman like James was expected to be polite, respectful, and courteous at all times. He would open doors for women, avoid public displays of emotion, and uphold a sense of decorum in every interaction. Conversation was often formal, and certain topics were considered inappropriate for public discussion.

Leisure time for Victorian gentlemen was centered around activities that matched their social standing. James may have enjoyed sports such as cricket or horse racing, or participated in hunting expeditions. He would have frequented clubs, where intellectual discussion was a favored pastime, and enjoyed performances at theaters and opera houses. These cultural pursuits helped maintain his image as a well-rounded, socially engaged individual.

As a Victorian gentleman, James would also have been expected to marry, ideally securing an advantageous alliance that would maintain or enhance his social standing. Marriage was viewed as a sacred institution, and a gentleman was seen as the protector and provider for his family. His role as a husband and father would have been seen as one of great responsibility.

Many gentlemen of James's era pursued careers in law, government, the military, or the clergy. Others, like James, may have been involved in family businesses or owned estates. Some, drawn to intellectual pursuits, would have made names for themselves in science, literature, or the arts. But regardless of their specific path, Victorian gentlemen were often expected to engage in philanthropy, contributing to charitable causes and public service to benefit their communities.

However, life as a Victorian gentleman was not without its pressures. The expectations were high, and there was little room for deviation from the norms of society. The need to maintain a certain image, adhere to etiquette, and conform to rigid societal standards could be emotionally taxing. There was always the pressure of preserving one’s reputation and status, and this often meant sacrificing personal desires for the greater good of maintaining one’s place in the social hierarchy.

For James, being a "gentleman" meant navigating a complex world of privilege, responsibility, and personal sacrifice, all while playing his part in the larger social fabric of Victorian London.

From his humble beginnings to the moment he found a lifelong partner, James William grew up surrounded by the warmth of a close-knit community. As he transitioned into adulthood, a serendipitous turn of events, he crossed paths with the love of his life, Elizabeth Ann Davis. I picture their first meeting as nothing short of magical, and from the moment they laid eyes on each other, their hearts were forever entwined. Their love only grewing stronger with each passing day, acting as a beacon of strength in their lives.

As I reflect on the life of James William Willats, a man whose spirit continues to resonate through generations, I am reminded of the power of love and through the support of loved ones, we can surmount any challenges that life throws our way.

May James William Willats' story inspire you to embark on your own remarkable journey through time, embracing every moment and discovery along the way. Like him, you too are part of a larger narrative, a story woven through the threads of your past, present, and future. With each discovery, big or small, may you find new layers of meaning, purpose, and connection. Let the lessons of love, resilience, and legacy guide you, leaving an indelible mark on the story of your own life, as James' journey continues to leave its own enduring imprint on generations to come.

Until part 2 of James’s life story,

Toodle pip,

Yours,

Lainey.

🦋🦋🦋

wow! Lainey,so interesting,well done

LikeLike