Welcome back to the captivating journey of James William Willats, an enigmatic figure whose life’s tale continues to unfold with both intrigue and inspiration. In our first installment, we embarked on a thrilling expedition through his early years. Now, we delve into the next chapter of his extraordinary life, the story of James William Willats as a married man.

As we retrace the footsteps of my fourth great granduncle, we will find ourselves traversing the paths of love, commitment, and growth. The entry into marriage marks a significant milestone in any person’s life, and for James, it proved to be no different. His heart now intertwined with another’s, his journey takes on new dimensions, and his character encounters fresh tests.

From the rich historical archives, we are invited to witness James’s transformation as he evolves into a devoted husband, partner, and provider. Drawing from dusty documents, the answers to his life’s stories lie in the annals of history which bore witness to his journey.

While we celebrate the joys and triumphs, we shall not shy away from acknowledging the challenges and sacrifices that accompanied this new phase of life. As with any union, there were moments of elation and moments of adversity, but it is within these human intricacies that we find the true essence of our ancestor’s character.

On the bustling streets of London, James and his wife Elizabeth embarked on their own adventure. Their love story, woven amid the backdrop of historical events, has captured the hearts of generations that followed.

As we immerse ourselves in the life of James William Willats as a married man, and discover the legacy of love and commitment. James leaves behind a timeless reminder of the power of human connection and the strength found in the bonds of marriage.

So, let us venture forth, hand-in-hand with James and his beloved, to a time of trials and triumphs, love and laughter. And as we honor the memory of James William Willats, let’s celebrate that this intriguing man is still being remembered all these years later.

The Life of James William Willats,

Embracing Life as a Married Man.

Welcome back to London in 1865, a city of vibrant contrasts, where history seems to pulse through the streets and the air is thick with the energy of change. London was at the crossroads of tradition and modernity, a sprawling metropolis where the hum of progress mingled with the weight of centuries-old customs. This was a city where stories of triumph and hardship intertwined, where the rich and poor existed side by side, though often worlds apart in experience.

At the helm of the British Empire was Queen Victoria, a monarch whose image was everywhere, from portraits to statues. She was the embodiment of the Victorian ideal, moral, steadfast, and deeply committed to the duty that came with her crown. Her reign, long and steady, cast a shadow over the entire Empire, a constant in an ever-changing world. By 1865, Queen Victoria had been on the throne for nearly 30 years, and though the world was rapidly evolving, she remained a symbol of stability. Despite personal tragedy in her life, including the passing of her beloved husband, Prince Albert, her reign was one of expansion, both geographically and culturally, as the British Empire continued to grow.

In the world of politics, the prime minister was Lord Palmerston, an older statesman who held sway over much of the country’s foreign and domestic policies. He was known for his fierce defense of Britain’s interests and a keen ability to navigate the complex political terrain of the time. But by 1865, even Palmerston’s influence was beginning to fade, and debates over reform were gaining momentum. It was a time of change, where the old guard was giving way to new ideas, and whispers of social reform and suffrage for the working class were stirring.

The streets of London were alive with the pulse of a nation on the brink of transformation. In the West End, the wealthy promenaded in the latest Parisian fashions, women in wide crinolines that swayed like clouds, their dresses a cascade of silk and lace. The men, ever the image of refinement, wore well-tailored suits with top hats perched just so. Their lives were a world of private carriages, glittering theatres, and sumptuous balls. The scent of roses filled the air at garden parties, and the hum of conversation in drawing rooms seemed as constant as the ticking of the grandfather clocks.

But for the majority, life was far different. The working class, the backbone of the city, could be found in the industrial heart of London—the East End, where the streets were lined with row houses and factories puffing thick clouds of smoke into the air. The rich may have lived in elegance, but the working class lived in the grit of progress. Horse-drawn buses clattered down the cobbled streets, and the noise of factory machines filled the air, alongside the shouts of market vendors. There was a sense of unrelenting toil for these men and women, with hours spent in dim factories or as servants in the homes of the rich, their lives shaped by labor, not luxury.

The divide between the rich and poor could not have been starker. The wealthy could afford to enjoy the city’s finest pleasures, opera, ballet, theatre, while the working class had their own forms of entertainment. Music halls and penny gaffs offered them vaudeville acts, comedic performances, and lively dances. The city’s theatres were the soul of high society, but for the working class, a trip to the music hall was an escape, a chance to laugh, to dream of a life they could never quite grasp. And as for the poor? They lived in squalor, their tenements crammed with families, the air thick with the stench of disease and poverty. Many families could barely afford to feed themselves, let alone entertain the idea of leisure.

The city itself was a place of constant motion. The train lines were expanding, stretching across the country, though most of London’s commuters still relied on the slow, rumbling horse-drawn omnibuses. For the rich, the private carriage was the mark of status, a personal oasis in the bustling streets. But even they were not immune to the rapidly changing world around them. The trains, new and daring, were beginning to transform travel, a hint of the future to come, though the underground railway was still in its infancy.

Yet for all its progress, the city was a place where the past seemed ever-present. London in 1865 was a city of coal smoke and soot, where the skies often seemed to be filled with a permanent grey haze. The Thames, once the lifeblood of the city, had become a foul river, its waters polluted by the waste of thousands of people, and its smell so rancid it was known to knock the wind from your lungs. The streets were often muddy, crowded, and poorly lit, with gas lamps flickering weakly in the dark. Even though gaslight was the latest in lighting technology, it was still a distant dream for many of the poorer districts, where darkness often swallowed up the night.

The rich lived in stately homes with gas lamps and fireplaces blazing in every room, while the poor huddled together in cold, damp, and poorly constructed buildings, relying on the occasional coal fire for warmth. The smell of burning coal filled the air, a constant reminder of the harshness of the environment. In the West End, gaslight bathed the streets in a soft glow, a symbol of comfort and affluence. But in the East End, where the working class lived, there was little light, and the night was often a time of fear, a time when crime and disease seemed to creep through the shadows.

Nutrition was also tied to class. The wealthy dined on rich meats, delicate pastries, and exotic imports from the Empire, with fresh vegetables and fruit available year-round. But for the poor, their diet was more limited, often consisting of cheap cuts of meat, potatoes, and bread. Many working-class families had to make do with what they could grow in small urban gardens or buy in the local markets. Fresh produce was a luxury, and the poorer you were, the harder it was to find anything nourishing beyond the basics.

Sanitation, too, was a matter of class. While the wealthy had private water supplies and servants to tend to their needs, the poor lived in areas where sewage ran through the streets, and the smell of refuse filled the air. Public health was beginning to be a topic of conversation, but the reality for many was that sanitation and clean drinking water were luxuries they could not afford. Disease was rampant, particularly in the East End, where cholera outbreaks were not uncommon, and the squalor of tenement living led to the spread of tuberculosis and other diseases.

Amidst all this, the city buzzed with gossip and intrigue. The lives of the rich were a constant source of fascination, who was marrying whom, which families were rising and which were falling. Scandals in high society were whispered about in drawing rooms, and the social columns in the papers eagerly awaited the next dramatic turn of events. Meanwhile, the lives of the working-class were filled with resilience and community, as people supported one another in the face of hardship. Yet, for all the gossip about the wealthy, the true stories of London’s underclass were often untold, their struggles unseen by the privileged few.

London in 1865 was a city of contrasts, of sharp lines drawn between the rich and poor, between tradition and progress, between the grand ambitions of empire and the quiet struggles of everyday life. It was a place of contradiction, where hope and despair lived side by side, and where the echoes of history and the whispers of the future could be heard in every street, every conversation, and every soul. It was a time of change, but also of deep-rooted inequality, a city on the edge of transformation, yet still deeply tied to the past.

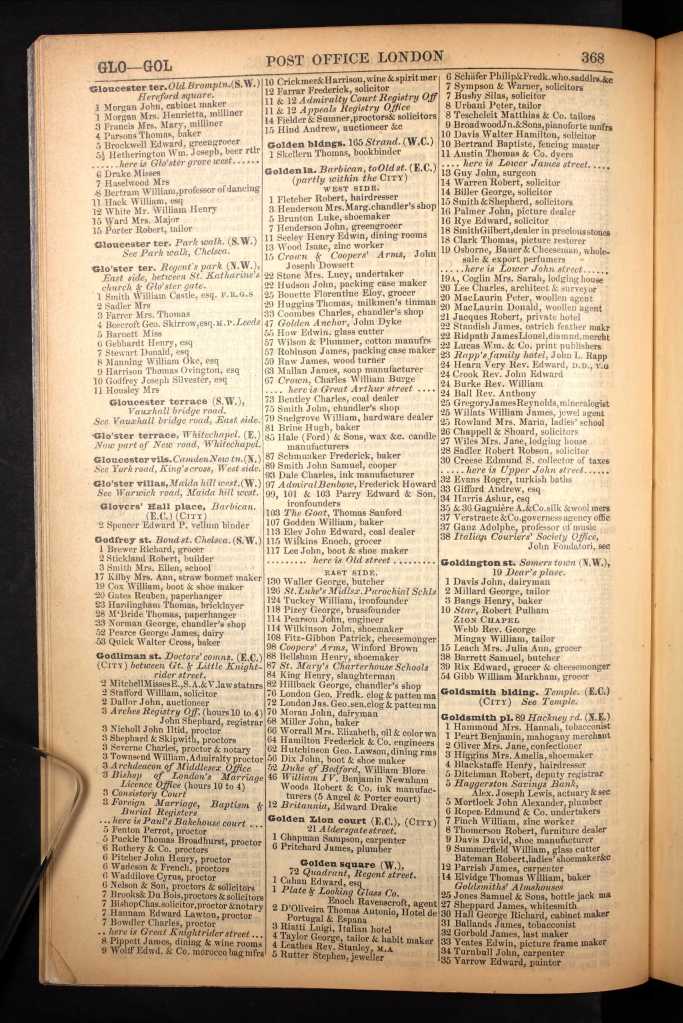

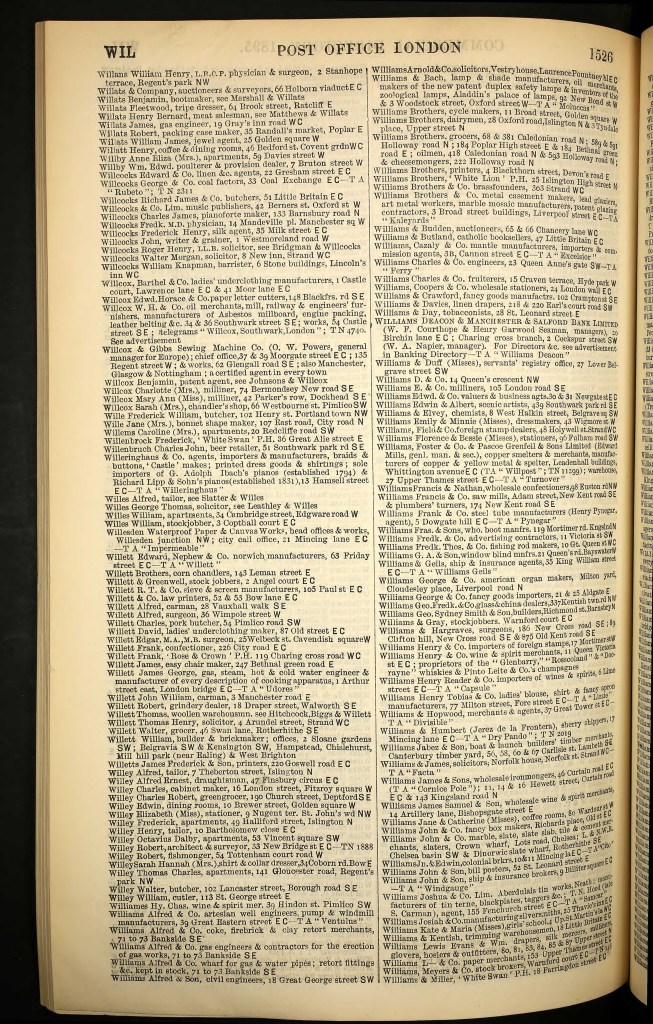

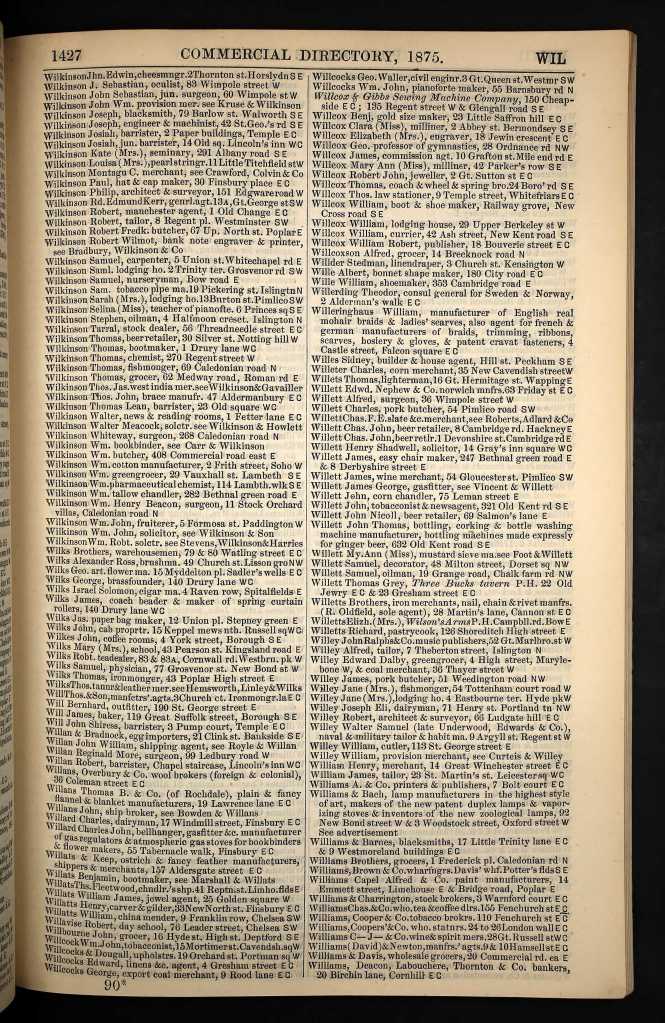

The first glimpse I had into James’s life after his marriage came unexpectedly, hidden in the pages of the 1865 Trade Directory. It was as if a door had opened just a crack, offering me a view into the world he was navigating at the time. There, amidst the rows of names and professions, was James, listed not by his full name, but simply as a "Jewel Agent." It was a title that seemed both elegant and elusive, the kind of profession that could whisper of riches, of precious stones, of high society. But it wasn’t the glamour that caught my attention; it was the address that followed.

Number 25, Golden Square, Soho, London. There, in the heart of one of London’s most bustling and vibrant districts, James was working from a location that sounded as intriguing as his profession. Soho, with its crowded, lively streets, filled with the hum of commerce, was a place where the boundaries between the fashionable and the ordinary were often blurred. It was a district known for its mix of entertainment, music halls, and shops, yet it also had a quieter side, home to businesses that catered to the tastes of the wealthy and the sophisticated.

Golden Square itself, a little square tucked away amidst the chaos of Soho, seemed to be a place where the busy pulse of the city met the more refined world of trade. I could almost picture James there, working tirelessly, surrounded by the gleam of precious stones and the whispers of potential deals. Though the directory entry was brief, it gave me the sense that this was a time of quiet ambition for him. He was starting to carve out his space in a city that was full of opportunity but also fierce competition.

The name "Jewel Agent" suggested someone who acted as an intermediary between the world of precious gems and the wealthy buyers who sought them. It wasn’t quite the same as being a jeweler, but perhaps it was the perfect role for someone like James, someone who had the skills and knowledge but didn’t yet have the means to own the glittering treasures he worked with. Soho, in 1865, was still a neighborhood of contrasts, where the bright lights of entertainment coexisted with more discreet, professional businesses. The presence of a Jewel Agent there felt like a symbol of the time, a blend of elegance and grit, of luxury and labor, a reflection of the larger world James was a part of.

As I read the directory entry again, I imagined what his days might have looked like. Maybe he was meeting clients in one of Soho's many cozy rooms, where deals were made over tea and the quiet hum of London life spilled in from the streets. Or perhaps he was overseeing transactions, arranging for exquisite gemstones to be delivered to wealthy customers who craved a touch of glamour in their lives. Whatever his role, it was clear that James was part of a world that balanced carefully between the everyday hustle of Soho and the glittering allure of fine jewels, all while making his mark on a city that was transforming before his very eyes.

So what would have been involved in working as a Jeweler Agent in 1870? Here’s a few examples. Crafting and Repairing Jewelry: Jewelers in the 1870s would spend a significant amount of time handcrafting fine jewelry pieces. They would work with precious metals such as gold and silver, and precious gemstones like diamonds, rubies, sapphires, and emeralds. Additionally, they would repair damaged or broken jewelry brought in by customers.

Designing Custom Pieces: A skilled Jeweler might have been asked to design custom jewelry pieces for wealthy clients or special occasions. This involved understanding the customer’s preferences, sketching designs, and creating unique jewelry items tailored to the individual’s taste.

Gemstone Selection: Jewelers needed expertise in evaluating and selecting high-quality gemstones. They would need to have an eye for identifying genuine stones and assessing their color, clarity, and cut.

Appraisal and Valuation: Clients might have sought the expertise of a Jeweler agent to appraise and value their jewelry for insurance purposes or estate planning.

Sales and Customer Service: Jewelers would be required to interact with customers, showcasing their inventory, and persuading potential buyers to make purchases. Providing excellent customer service was crucial for building trust and repeat business.

Metalworking and Casting: Jewelers of that era often had to engage in metalworking and casting processes to create jewelry settings and structures.

Engraving and Embellishment: Hand-engraving was a common technique used to add intricate designs or personalization to jewelry pieces.

Keeping up with Trends: Staying up-to-date with the latest jewelry trends and fashion preferences was essential for offering desirable and contemporary designs.

Working with Precious Metals: Jewelers were required to melt, shape, and solder precious metals to create various components of jewelry items.

Managing Inventory: Jewellers needed to keep track of their inventory, including gemstones, precious metals, and finished jewellery items.

It’s important to note that in 1870, the jewellery industry lacked modern tools and technologies. Most jewelry making was done by hand, and crafting a single intricate piece could take considerable time and effort. Jewelers were highly skilled artisans and often apprenticed under experienced craftsmen to acquire their expertise.

The jewelry market was influenced by cultural and societal factors, and the clientele often consisted of the wealthy elite. While some jewelry stores were independent businesses, others may have been associated with larger retailers or manufacturers.

Overall, being a Jeweler agent in 1870 was a specialized and respected profession, requiring a blend of artistic creativity, technical skill, and business acumen.

Richard Henry Willats, my 4th great-granduncle, had a long and winding road to the moment that changed everything for him. After years of what I can only imagine were quiet moments of longing, Richard finally married the love of his life, his soulmate, Eliza Willats, née Cameron, my 4th great-grandmother, on Thursday, May 4th, 1865. It was a moment of joy, but also one shrouded in curious details, as their union took place at St. Margaret’s Church in Westminster, London, a place of history, elegance, and reverence, fitting for such a significant occasion.

At the time of the marriage, Richard was still a bachelor, stepping into a future he must have eagerly anticipated. But the oddity of the situation lies in Eliza’s status. She was listed as a widow, which made me pause and wonder. Her first husband, George John Willats, none other than Richard’s own brother, and my 4th Great Grandfather, hadn’t passed away yet. In fact, George John would only die later that same year. It’s one of those small, perplexing details that left me with a sense of mystery, as if something more lay beneath the surface, perhaps unspoken or unnoticed in the public records.

Their witnesses, however, added another layer of intrigue to the story. Of course, Richard’s brother George John Willats, Eliza’s late husband, was there, not yet gone from this world but surely present in the minds of both Richard and Eliza on this fateful day. And then there was Eliza’s sister, Mary Cameron, who must have played an important role in her sister’s life, standing by her side to mark this new chapter. It’s easy to imagine how the presence of these two, George, who had been both family and husband, and Mary, a sister bound by blood and love, added weight to the ceremony, making it feel both joyful and bittersweet.

At the time, Richard and Eliza were living at 10 North Street, a modest address that, in my mind, evokes the feel of a busy, bustling London street where life moved swiftly and the world outside their door was filled with possibility. Richard worked as a Commercial Traveller, which meant he was always on the move, probably crisscrossing the city, perhaps the entire country, representing companies, selling goods, and meeting clients. His life was one of constant travel, and I can only imagine the strain it must have placed on him, never staying in one place for too long, always looking toward the next journey.

Eliza, too, came from a background of hard work and skilled labor. Her father, Allen Cameron, worked as a tailor, a trade that required both precision and artistry, fitting for someone like Eliza, who would later marry into the Willats family. Richard’s father, George John Willats, was a wood carver, a craft that would have demanded both strength and delicate skill, chiseling away at wood to create intricate designs that could last for generations. In many ways, the trades of these two families reflected their personalities: steady, dedicated, and deeply connected to the artistry of their work.

The marriage between Richard and Eliza, while a moment of love and hope, was also a reflection of the complexities of life during that time, an intricate web of relationships, familial bonds, and personal histories that would shape their journey together. What began on that warm May day in 1865 would unfold into a life marked by love, loss, and the shared stories that continue to echo through the generations.

As I have said in previous life stories, I have no idea as to how Richard and Eliza were able to marry, as it was strictly forbidden to marry a brothers wife even a deceased brother.

Family story’s state that, a sympathetic member of the clergy came to their rescue and had the first marriage annulled.

I guess we will never know for sure but it seems that maybe something fishy was going on as George John married Sarah Elizabeth Southall Jukes, in Victoria, Australia, in 1856 (11years before Richard and Eliza wed. George and Sarah, went on to have 4 Children. George John, stayed in Australia until his death, visiting England frequently.

In 1865, marriage laws in England were both a reflection of deep-rooted traditions and a mirror to a society that valued control and order over individual desires. The law did not simply govern the formalities of a wedding or the process of becoming a husband and wife, it was a structure that placed immense weight on family, bloodlines, and social order. In this tightly regulated world, marriage was seen as a contract, not just between two people, but between families, social classes, and communities. It was the bedrock of social standing, family reputation, and even economic stability.

One of the most critical aspects of these laws was the importance of blood relations and the rules about who could and could not marry. Marriages were, by law, forbidden between close relatives, siblings, parents and children, and, crucially, between a person and their sibling’s spouse. The law held strong prohibitions against these unions, partly because they were seen as morally reprehensible and biologically risky, and partly because society viewed the integrity of family bonds as sacrosanct.

The prohibition against marrying one’s brother’s wife or sister’s husband was as serious as the taboo against incest. It wasn’t merely a social no-no; it was legally binding, and breaking it could have severe consequences. For example, if someone married their brother’s widow, or vice versa, the marriage would be considered invalid, and the couple could be forced to separate. The legal reasoning behind this was complex, but much of it came down to the idea of preserving family integrity. A man marrying his deceased brother’s wife could threaten the family’s ability to maintain clear lines of inheritance and property, potentially creating legal conflicts. Similarly, marrying a sibling’s spouse was seen as a betrayal of the family, an act that could upset the balance of power and loyalty within it.

In the eyes of the law, the bond between siblings was not just one of blood, but one of allegiance to the family unit. The notion that a person could marry into the family in such a direct way was thought to undermine the very structure of society and the moral fiber it stood upon. To marry your brother’s wife, in particular, was seen as a disruption of the sacredness of the family unit. The law also recognized that such a union could create complications with inheritance. In an era when property and wealth were inherited through the male line, any ambiguity in family relationships, such as a brother marrying his sibling’s widow, could create disputes that would have been messy and difficult to resolve.

The legal concept of "consanguinity" (the closeness of blood relationship) governed most of the marriage restrictions. While it was illegal to marry a direct blood relative like a parent or sibling, the law also extended to prohibiting marriage with in-laws. Marrying a brother's widow or a sister’s husband was regarded as a violation of that sacred family bond. This was because the marriage between siblings, by law, and for the purposes of inheritance, was considered too closely related, no matter how indirect. It was considered the same as marrying a direct family member in the eyes of the law, not just a legal transgression, but a social and moral one as well.

The impact of such laws went far beyond simply preventing marriages between siblings and their in-laws. These laws shaped the very foundation of family relationships in Victorian England. Families were not just linked by love, but by an intricate web of social expectations, financial dependencies, and legal bindings. A woman could not simply marry anyone she loved; she had to marry someone who was deemed "suitable" by society’s standards, someone who could offer her security, social standing, and compatibility within the framework of family law. For men, the same expectations applied, though they had more legal freedoms in choosing their spouses. Still, the laws surrounding marriage dictated that a man, especially one of higher social standing, must often consider the wealth, lineage, and reputation of a woman before choosing her as a wife.

In practical terms, these laws and restrictions could create significant personal and familial tension. Imagine a widow who, after the death of her husband, found herself in a difficult position, unsure of her future. The legal barriers preventing her from remarrying within the family could leave her isolated, especially if she was still young and had no means of supporting herself. On the flip side, imagine the dilemma of a man who had lost his brother but wanted to marry his widow. The law dictated that such a union was impossible, even if it made perfect sense for them emotionally. In that sense, the law created barriers between what was socially accepted and what individuals desired, often resulting in heartache.

Yet, despite the restrictions, there were still people who found ways to circumvent the law or bend it. In some cases, a man could marry his brother’s widow with a special license if the local authorities agreed or if there were compelling reasons for the marriage. However, such cases were rare and often took years to be legally approved. For most people, the laws surrounding in-law marriages were non-negotiable, a set of rules that defined their personal and social lives.

Looking at marriage laws in 1865, it’s clear how heavily they shaped lives and relationships. The inability to marry a brother’s wife or a sister’s husband was not just a legal restriction; it was a moral boundary that governed relationships within families. The rules that regulated marriage were meant to preserve social order, and the weight of these restrictions bore down on individuals, often forcing them into difficult choices. For many, marriage was not just about love; it was about securing one’s place in society, ensuring family legacy, and fulfilling duty. The law stood as a barrier to anything that might disrupt that order, even if love or affection was at stake.

For someone living in 1865, marriage was more than just an emotional connection. It was a contract, a bond that tethered families together with an invisible yet undeniable force. Laws like those prohibiting marriage between a sibling and their spouse were a reminder that the family was not just a group of people; it was a delicate system that required careful regulation. And in the end, despite the seeming rigidity of the laws, they were shaped by something deeply human: the desire to protect, preserve, and sustain family bonds, however complicated they might be.

St. Margaret’s, known as ‘the Church on Parliament Square’, is a 12th-century church next to Westminster Abbey. It’s also sometimes called ‘the parish church of the House of Commons’.

The Church of St Margaret, Westminster Abbey, is in the grounds of Westminster Abbey on Parliament Square, London, England. It is dedicated to Margaret of Antioch, and forms part of a single World Heritage Site with the Palace of Westminster and Westminster Abbey.

The church was founded in the twelfth century by Benedictine monks, so that local people who lived in the area around the Abbey could worship separately at their own simpler parish church, and historically it was within the hundred of Ossulstonein the county of Middlesex. In 1914, in a preface to Memorials of St. Margaret’s Church, Westminster, a former Rector of St Margaret’s, Hensley Henson, reported a mediaeval tradition that the church was as old as Westminster Abbey, owing its origins to the same royal saint, and that “The two churches, conventual and parochial, have stood side by side for more than eight centuries – not, of course, the existing fabrics, but older churches of which the existing fabrics are successors on the same site.

In 1863, during preliminary explorations preparing for this restoration, Scott found several doors overlaid with what was believed to be human skin. After doctors had examined this skin, Victorian historians theorized that the skin might have been that of William the Sacrist, who organized a gang that, in 1303, robbed the King of the equivalent of, in modern currency, $100 million. It was a complex scheme, involving several gang members disguised as monks planting bushes on the palace. After the stealthy burglary 6 months later, the loot was concealed in these bushes. The historians believed that William the Sacrist was flayed alive as punishment and his skin was used to make these royal doors, perhaps situated initially at nearby Westminster Palace. Subsequent study revealed the skins were bovine in origin, not human.

You can read more about, St Margaret’s here.

The year 1865 brought with it a shadow of sorrow that would forever mark the Willats family. The sad news of James’s brother, George John Willats, reached them from the far-flung shores of Victoria, Australia, casting a pall over what had otherwise been a year filled with new beginnings. George John’s death came after the 19th of June, when he had returned to Australia following his brief time in England as a witness at Richard and Eliza’s wedding.

While the exact nature of their relationship is unclear, I can’t help but feel a deep sense of warmth when I think about it. There’s something about the way Richard stepped into the role of a father for George John’s son that speaks to a connection that ran deeper than mere familial obligation. After all, Richard had been there for the boy, raising him when his own father couldn’t, and later, George John stood by as a witness at Richard’s wedding to Eliza, the very woman who had once been his wife and mother to his child. Perhaps, in this act, there was a quiet symbol of reconciliation, or at the very least, a reminder of the closeness that the family shared, despite the twists and turns that life had taken.

Of course, it’s impossible to know for certain the full extent of their bond, but there’s a sense of continuity that lingers when thinking about this moment. Eliza and George John’s son seemed to have been taken in by the Willats family in a way that suggests the ties between them were more than just those of a distant, formal family. Richard’s role in his nephew’s life, nurturing him through the difficult days after George John’s departure, paints a picture of a family that was bound by a certain tenderness. In fact, when I think about how George John stood as a witness to his first wife’s remarriage, I can’t help but wonder if this was not just an act of duty, but of genuine goodwill, love and respect.

Though George John’s passing came from far away in Australia, the ripples of his death were felt across the miles, weaving a sense of melancholy into the fabric of the family’s history. Yet, despite the sorrow, there’s a comforting thought that lingers: that in the end, despite the distances, the possible strained relationships, and the heartache, there was a profound sense of connection that held them all together.

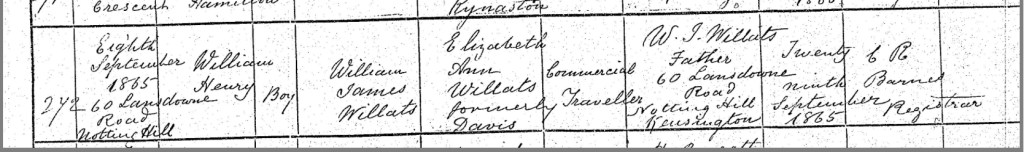

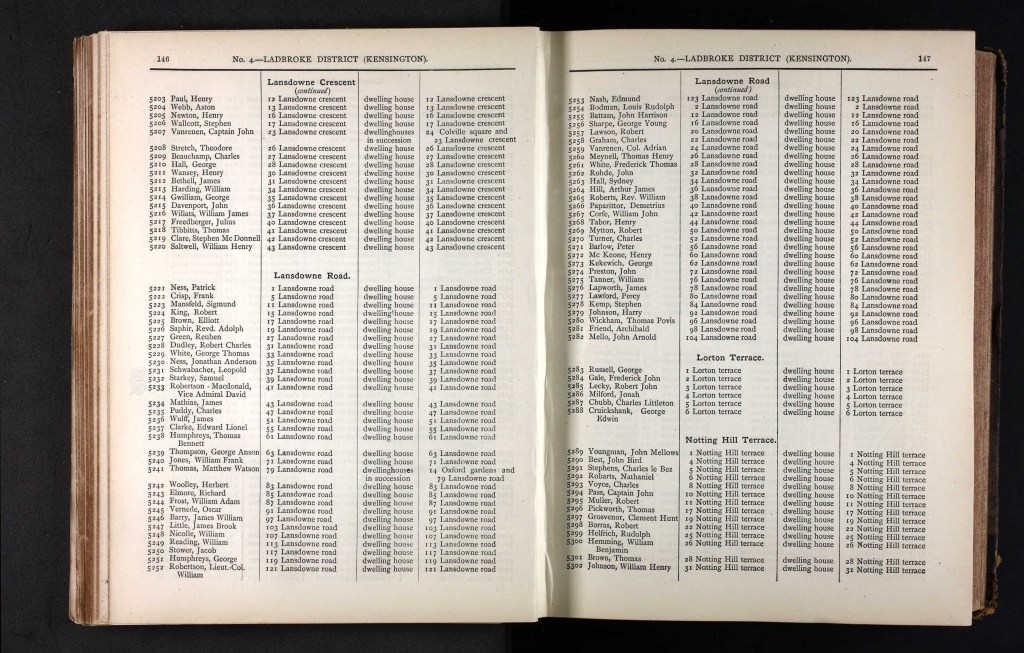

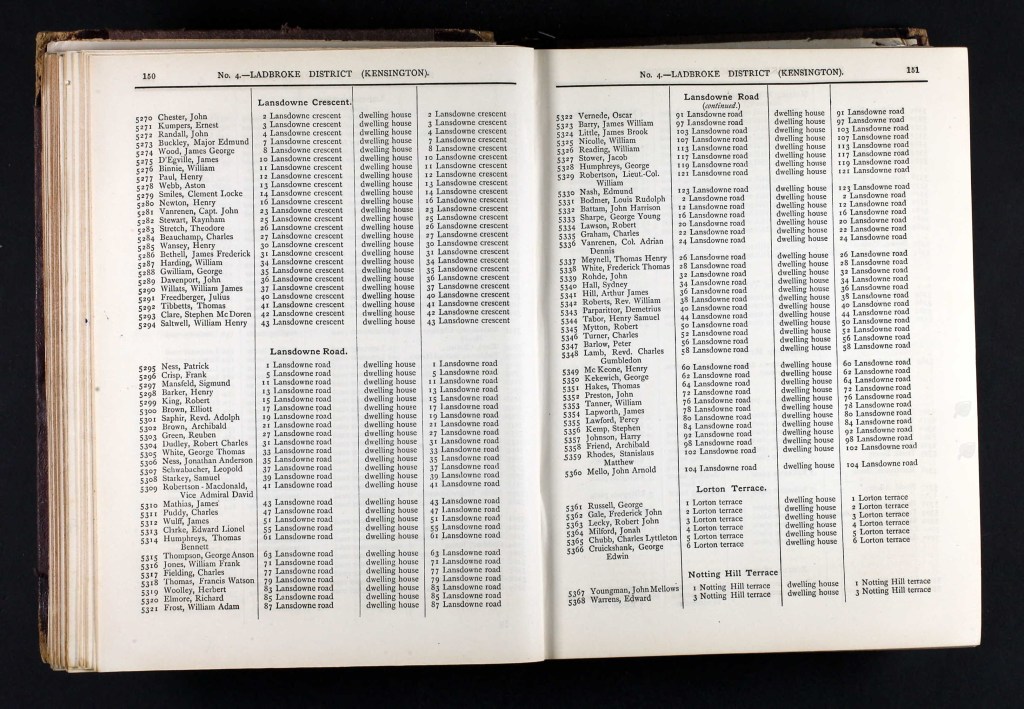

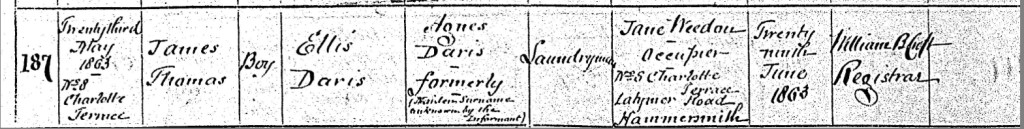

On a September day in 1865, James William and Elizabeth Ann Willats (née Davis) welcomed their son, William Henry Willats, into the world. Born on the 8th of September at Number 60, Lansdowne Road, in the heart of Notting Hill, Kensington, William’s arrival surely brought a glow of joy to the Willats household. The genteel address, with its quiet charm and promise of stability, became the backdrop for this new chapter in their family story. A few weeks later, on the 29th of September, James, ever the diligent patriarch, made his way to register his son’s birth. The official records bear his unmistakable mark of individuality: while his given name was James William, he had a habit of flipping the order, introducing himself as William James. With characteristic precision, he listed his profession as a Commercial Traveller, a role that likely took him far and wide, bringing the world into the orbit of their home on Lansdowne Road. This simple act of registration, ink on paper, became a touchstone of their lives, capturing not just the facts but the essence of a family carving out its place in the bustling tapestry of Victorian London.

Lansdowne Road in Kennington, London, is a street that weaves together the rich tapestry of the area's history and the personal stories of its residents. The name "Kennington" itself is steeped in history, believed to derive from Old English, possibly meaning "farm or estate associated with Coena." This etymology hints at the area's agricultural roots before it evolved into the vibrant urban landscape we know today.

The development of Lansdowne Road mirrors the broader urbanization of Kennington. In the mid-18th century, the construction of Westminster Bridge and its approach roads increased traffic through the area, highlighting the inadequacies of existing routes. This led to the creation of new roads, including Kennington Road, known initially as the New Road or Walcot Place, which connected Westminster Bridge Road with Kennington Common.

As the 19th century progressed, Kennington transformed from rural estates to a suburban enclave. The land, once owned by the Earls of Arundel and later the Dukes of Norfolk, began to see residential development. In 1559, Thomas, Duke of Norfolk, sold a portion of the land, paving the way for future urbanization.

The architectural landscape of Kennington, including streets like Lansdowne Road, was further shaped in the 20th century by town planners and architects such as Stanley Ashtead. Ashtead's vision and designs significantly influenced the post-Victorian character of the area, contributing to the unique blend of historical and modern elements that define Kennington today.

Today, Lansdowne Road stands as a testament to Kennington's rich history, reflecting the area's journey from pastoral lands to a bustling urban neighborhood. The street's architecture and its very name serve as reminders of the layers of history and personal stories that have shaped this distinctive part of London.

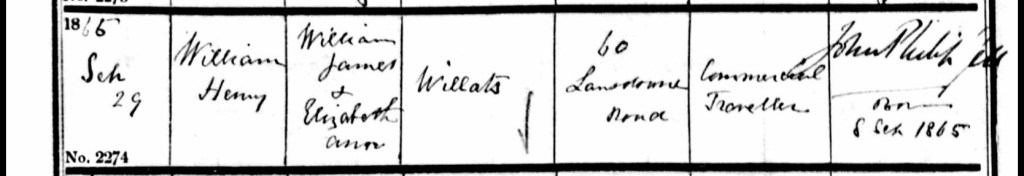

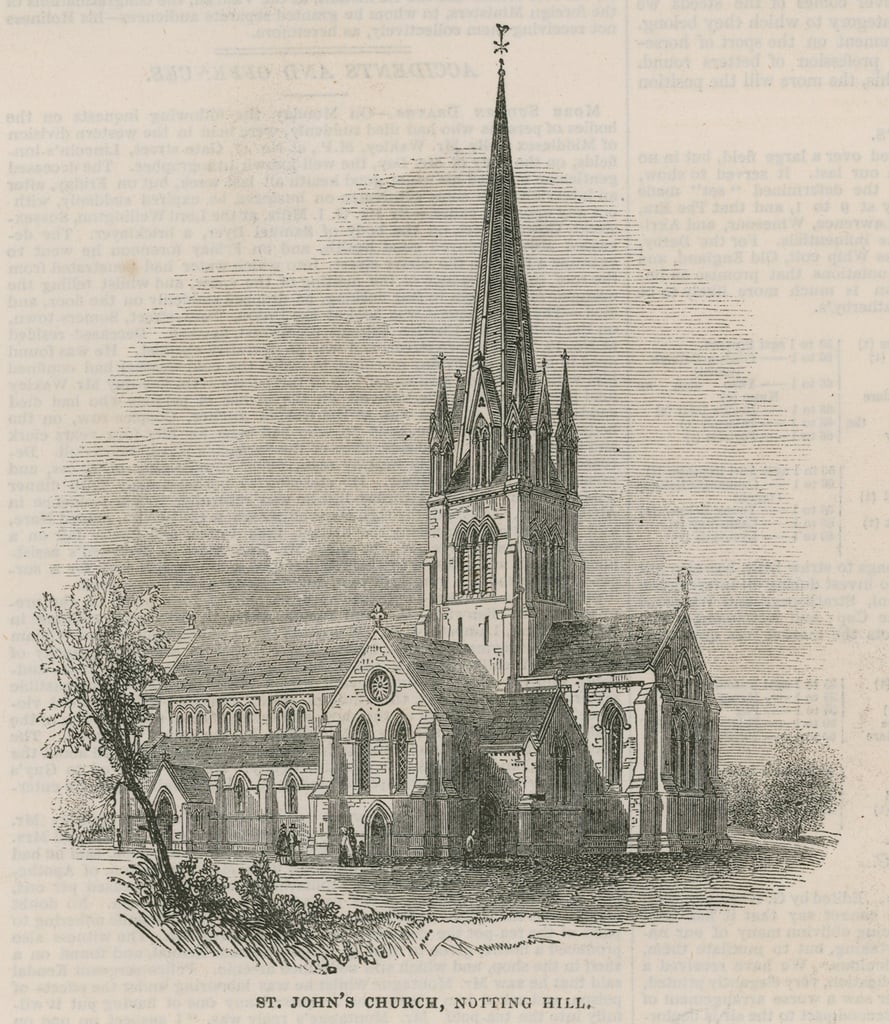

On a bright autumn Friday, the 29th of September, 1865, James William and Elizabeth Ann Willats brought their infant son, William Henry, to the font of Saint John the Evangelist in Notting Hill. The church, with its soaring arches and hallowed air, was the perfect backdrop for a moment as significant as this, a proud declaration of faith and family.

As the waters of baptism were poured, William Henry Willats was welcomed into the fold, his name ringing out with promise and hope. James, a Commercial Traveller by trade, stood alongside Elizabeth, both surely glowing with the quiet pride of young parents setting the foundations of their son’s life. Their home was listed as 60 Lansdowne Road, a genteel address that whispered of stability and a touch of aspiration.

That day, within the stone walls of Saint John the Evangelist, the Willats family etched their names into both the spiritual and earthly records of Notting Hill, a poignant step in their shared journey.

St John’s, Notting Hill is a Victorian Anglican church built in 1845 in Lansdowne Crescent, Notting Hill, London, designed by the architects John Hargrave Stevens (1805/6–1857) and George Alexander (1810–1885), and built in the Victorian Gothic style. Dedicated to St John the Evangelist, the church was originally built as the centrepiece of the Ladbroke Estate, a mid nineteenth century housing development designed to attract upper- and upper middle-class residents to what was then a largely rural neighbourhood in the western suburbs of London.

In 1821 James Weller Ladbroke (died 1847) and his architect Thomas Allason (1790–1852) began to plan an estate on land which now spans the southern end of Ladbroke Grove. From 1837 to 1841 a significant part of this land was used as the Hippodrome race-course. The hill that is now surmounted by St John’s was used by spectators as a natural grandstand to view the races. The Hippodrome was not however a financial success, and by 1843 it had closed, the circular racecourse soon to be replaced by crescents of stuccoed houses. St John’s Church, now a Grade II listed building, forms the high point and centrepiece of the Ladbroke estate, and is dedicated to St John the Evangelist. It was built to accommodate a congregation of 1,500, and was designed in the Early English style, the spire being notably similar in design to that of St Mary’s Church in Witney, Oxfordshire. The architecture of St John’s contrasts with the classical style of neighbouring St Peter’s, built a decade later. Money was raised by private subscription, in particular by means of two substantial loans of £2,000, one from Viscount Canning and one from entrepreneur Charles Blake, who also helped to finance St Peter’s. Work on St John’s was begun on 8 January 1844, when the foundation stone was laid by the Ven John Sinclair, Vicar of Kensington from 1842 to 1875, and Archdeacon of Middlesex. During Sinclair’s long incumbency (1842–1875), 19 parish churches were built in Kensington, of which St John’s was the first. It was consecrated by Dr Charles James Blomfield, Bishop of London, on 29 January 1845. Due to its rural location, the church was initially known as “St John in the Hayfields”.

It is with a heavy heart that we recount the passing of Julia Elizabeth Condon (née Willats), the beloved sister of James. At just 41 years of age, Julia, a widow of commercial traveller David Condon, took her final breath on Sunday, March 11, 1866. She passed away at her home on Sheffield Terrace in Kensington Town, Kensington, Middlesex, England, after a brave battle with phthisis, a relentless illness of the lungs.

By her side in her final moments was Elizabeth Gilbert of Holland Street, Kensington, a testament to the love and care Julia inspired in those close to her. Elizabeth took on the somber duty of registering Julia’s death just two days later, on Tuesday, March 13, 1866, in Kensington. Julia’s untimely departure left a profound void in the hearts of her family and friends, who mourned the loss of a gentle soul taken far too soon.

On a solemn Friday, the 16th of March, 1866, Julia Elizabeth Condon was gently laid to rest in Brompton Cemetery, Westminster, London. She was interred in an 8-foot common grave, marked O263.ox26.0—a final resting place amidst the serene grounds of this historic cemetery.

Her recorded residence at the time was 1 Sherfield Terrace, Kensington, a home that likely bore witness to her joys, struggles, and the quiet courage she carried throughout her life. Though her grave may be humble, the love and memories she left behind are anything but. Julia’s spirit lives on in the hearts of those who knew and cherished her, a lasting testament to a life cut short but deeply felt.

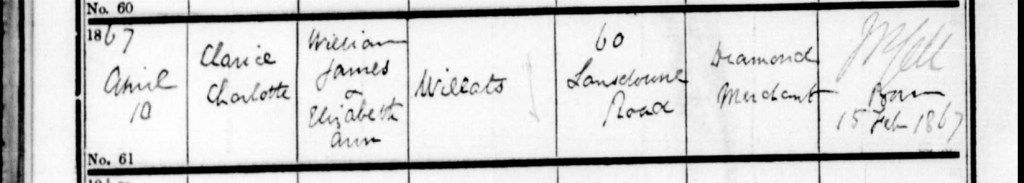

On a winter Friday, February 15th, 1867, beneath the bustling skies of Kensington, London, a new chapter began for James William and Elizabeth Ann Willats (née Davis). Their daughter, Clariss Charlotte Willats, arrived into the world at the family home, Number 60, Lansdowne Road. The stately street, known for its elegance, became the setting for the debut of a little girl destined to carry the charm of her name into the future.

A month later, on March 19th, James, ever the meticulous gentleman, registered his daughter’s birth with the precision befitting his trade. A jeweler by profession, James had an eye for detail, a talent that no doubt extended beyond his workbench to the way he filled out that all-important certificate. The family’s abode remained the same, Number 60 Lansdowne Road, a residence that whispered of refinement and security.

True to his individual flair, James didn’t follow convention when it came to his name. Though christened James William, he presented himself with his names intriguingly swapped: William first, James second. A small but telling quirk, it hinted at a man who walked his own path, setting the tone for the family he would raise. And so, with Clariss’s birth officially noted and her future unfurling ahead, the Willats family continued their life in Kensington, steeped in the traditions and quiet grace of the era.

Working as a jeweller in Soho, London, in 1867 would have been a fascinating yet challenging experience, steeped in the burgeoning atmosphere of the Victorian era. Soho was a vibrant area, known for its diverse population and bustling streets filled with artisans, craftsmen, and businesses catering to the expanding middle class. The industrial revolution had transformed the landscape of manufacturing, and the jewellery trade was no exception.

A jeweller in Soho would likely have started the day early, as the rhythm of work was dictated by daylight and the demands of customers. The workshop would have been a compact space, often shared with other craftsmen or tradesmen. It would have been filled with the sounds of tools clinking, the smell of metal and polishing compounds, and the sight of various materials, gold, silver, and precious stones, spread across workbenches. The jeweller would have spent much of their day engaged in a variety of tasks, which included designing, crafting, and repairing jewellery.

Daily tasks would vary depending on the jeweller's specific role and expertise. A jeweller might begin by sketching designs for new pieces, taking into account the latest fashions and customer preferences. This required not only artistic skill but also an understanding of the market and trends, as the demand for certain styles could fluctuate rapidly. Once a design was approved, the jeweller would move on to sourcing materials, which involved working with suppliers to obtain the required metals and gemstones, often negotiating prices to maintain profitability.

The actual crafting process was meticulous and labor-intensive. Jewellers used a range of hand tools, such as files, saws, and hammers, to shape and assemble pieces. Techniques like soldering, stone setting, and engraving required a high level of precision and skill, as even the smallest mistake could ruin a piece. This meant that jewellers had to possess not only technical ability but also patience and attention to detail. Many jewellers would have trained as apprentices, spending years honing their craft under the guidance of more experienced artisans.

Working conditions in the workshop could be challenging. Lighting was often inadequate, especially on cloudy days or in the winter months, which made intricate work more difficult. The air could be filled with dust and fumes from various materials, which posed health risks over time. The jeweller would need to be mindful of safety, especially when handling sharp tools and hot soldering equipment.

Despite these challenges, the job could also be rewarding. Successful jewellers had the opportunity to create exquisite pieces that could be displayed in shop windows, attracting the attention of potential buyers. Custom orders from wealthy clients could also bring significant financial rewards. Jewellers often formed close relationships with their customers, as personalised pieces were highly valued, and word-of-mouth recommendations were essential for business growth.

By the end of the day, a jeweller in Soho would likely have felt a deep sense of satisfaction in having contributed to the vibrant tapestry of London’s jewellery scene, playing a part in the lives of clients who cherished the pieces crafted by skilled hands. The blend of artistry, craftsmanship, and entrepreneurship defined the life of a jeweller in this bustling neighbourhood during the Victorian era, encapsulating the spirit of an age marked by innovation and change.

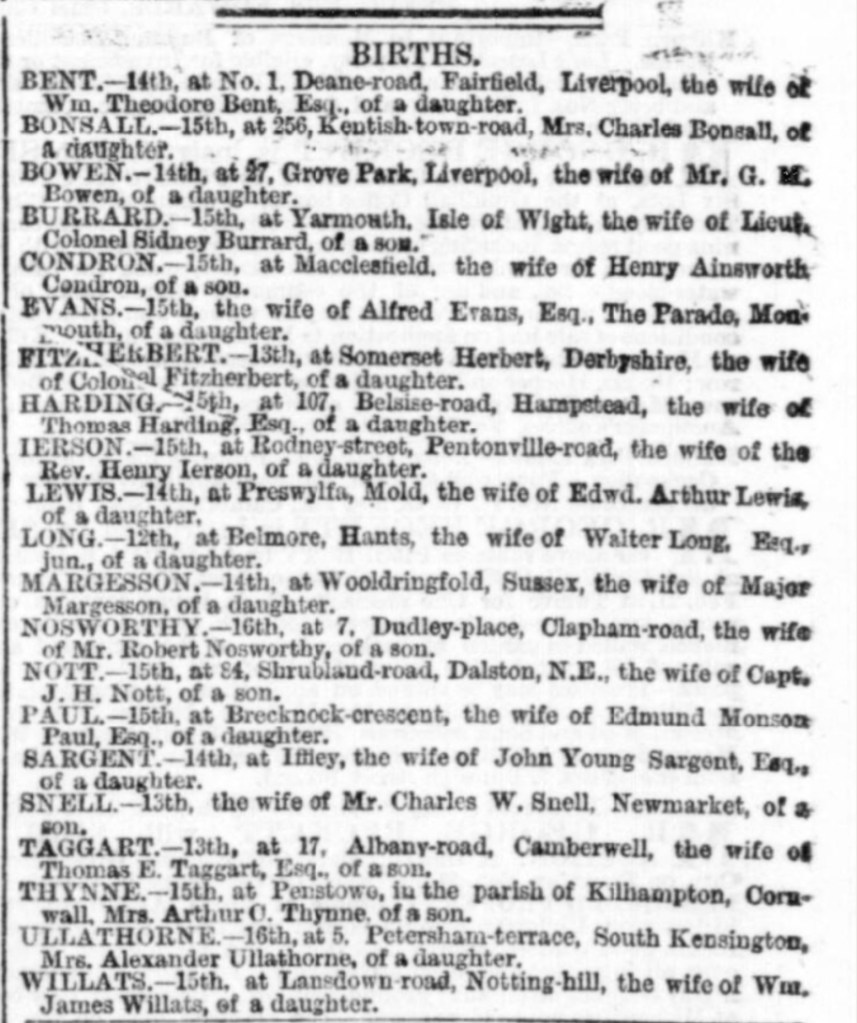

On a chilly Monday, February 18th, 1867, James William Willats, ever the proud and doting father, took a moment to share his family’s joy with the world. Nestled amidst the columns of the esteemed London Evening Standard, a simple yet heartwarming announcement appeared, bearing news of a precious arrival: **WILLATS.—15th, at Lansdown Road, Notting Hill, the wife of Wm. James Willats, of a daughter.** With these few elegant words, James made it known that his wife, Elizabeth Ann, had given birth to their daughter, Clarice, just days earlier on February 15th. The announcement, understated yet brimming with pride, carried the charm of the era, a delightful whisper of family news shared across the city. And in true James fashion, he made sure his chosen moniker, "Wm. James Willats," added a distinctive flair to the occasion, an enduring reminder of his penchant for swapping his names. From their home at Lansdowne Road, Notting Hill, the Willats family’s joy was now inked for posterity, a small yet enduring detail in the grand story of their lives.

On a serene Wednesday, April 10th, 1867, beneath the soaring arches of Saint John the Evangelist in Notting Hill, a little girl named Clarice Charlotte Willats was baptized. Her proud parents, James William and Elizabeth Ann, stood at her side as she was welcomed into the fold, the promise of her future unfolding in that sacred space. The church, a steady pillar of their community, became the setting for a moment that would remain etched in the fabric of their family’s story forever.

James, who had made a name for himself as a Diamond Merchant, was a man whose life sparkled with ambition and precision. The trade he pursued, rare and radiant, seemed a fitting reflection of his character. He and Elizabeth, ever the poised couple, called 60 Lansdowne Road home, a place where aspirations were nurtured and family ties grew strong.

That day, as the waters of baptism touched Clarice’s forehead, the Willats family’s story continued to be written in ink and devotion, at the intersection of faith, ambition, and the promise of a bright future.

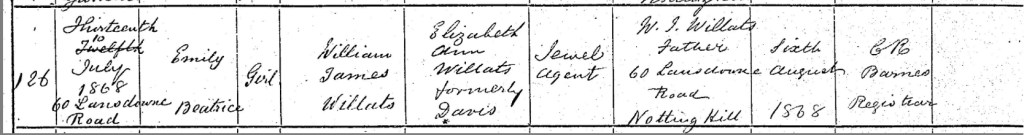

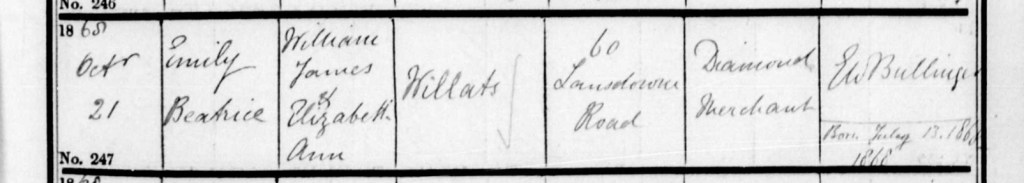

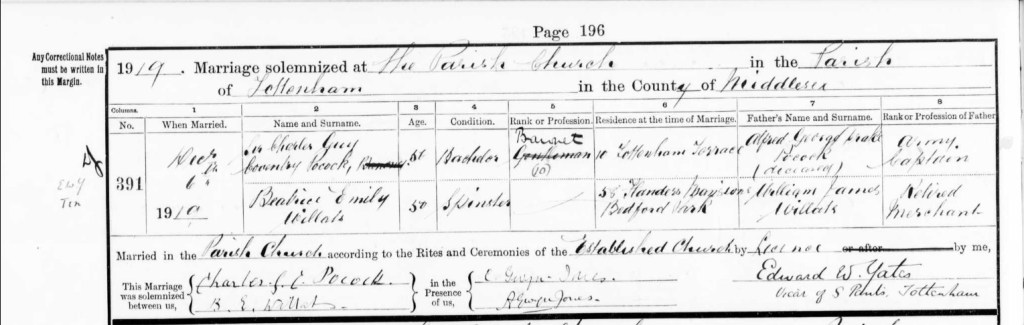

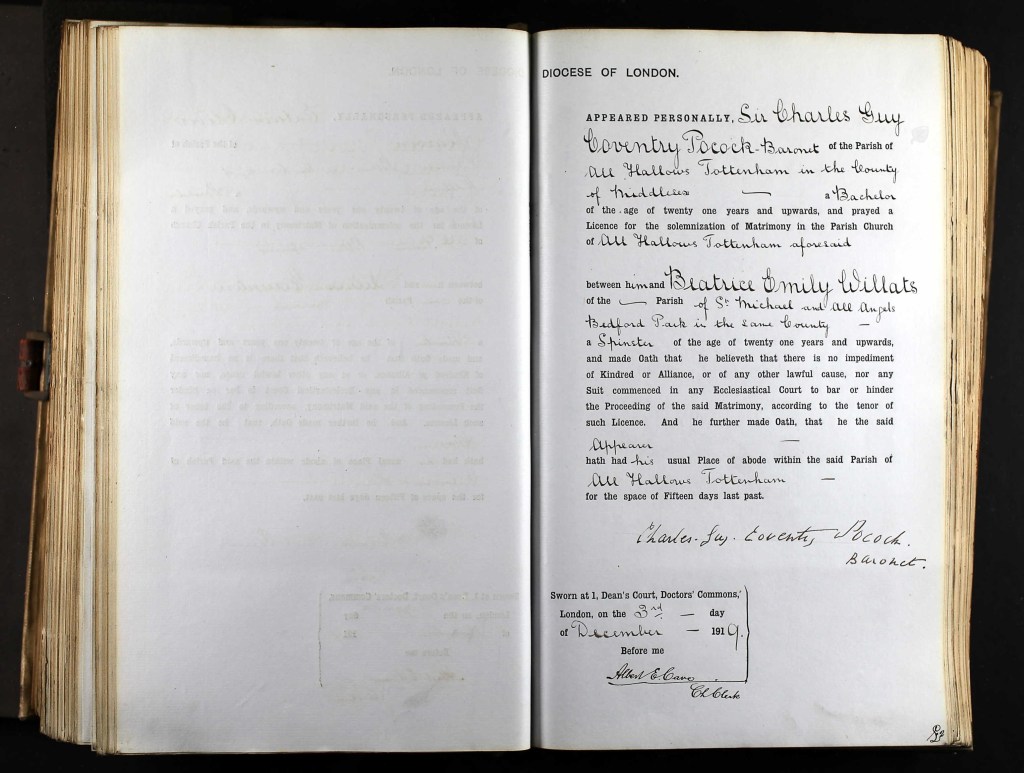

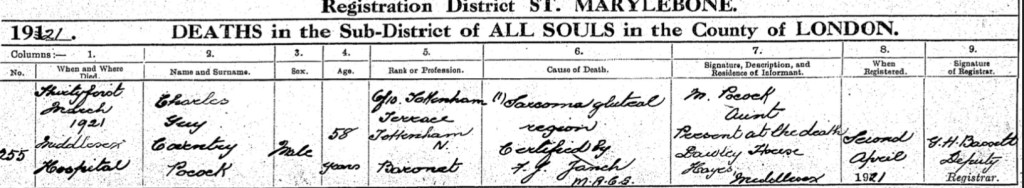

On Monday, the 13th of July, 1868, a soft cry echoed through the rooms of Number 60, Landsdowne Road, Kensington, London. It was the birth of James William and Elizabeth Ann Willats’ second daughter, Emily Beatrice Willats. The family’s home, located in the heart of Notting Hill, was about to be filled with even more joy, as the little one joined her siblings in this already lively household.

James, ever diligent, registered Emily’s birth on the 6th of August, 1868. His occupation was listed as a Jewel Agent, a title that hinted at his role in the world of precious stones and business dealings, a life of both finesse and trade. Their abode, the same residence where Emily was born, stood proudly at Number 60, Landsdowne Road. To those who would see the name written, it may have looked unassuming, but for James and Elizabeth, it was a place where memories were made and lives intertwined.

In a tradition common for some during that time, James used his middle name, William, as his first name, with James being his middle. There’s a certain quiet authority in the way he carried himself, as though each name he used spoke to different aspects of his character, his work as a Jewel Agent, his standing in society, and his personal identity.

As for Emily, while she was named Emily at birth, she would come to embrace her middle name, Beatrice, for much of her life. The name “Beatrice” itself, elegant and timeless, would have suited her perfectly, graceful, serene, and full of potential. Perhaps it was the sweetness of that name that seemed to carry her through her years, or perhaps it was the quiet strength that lay beneath it. Either way, “Beatrice” was the name that stuck, a soft yet dignified moniker that would follow her through all her days.

In the heart of that bustling city, surrounded by the everyday rhythms of life, Emily’s early years were likely filled with the laughter of siblings, the steady presence of parents, and the warmth of the family home. And as she grew into the woman she would become, I imagine Emily Beatrice carrying that name with the same elegance and quiet beauty it promised when she first entered the world, at Number 60, Landsdowne Road.

On an autumn day, Wednesday the 21st of October, 1868, Emily Beatrice Willats was brought before the solemnity of St John’s Church, Notting Hill, for her baptism. Her parents, James William and Elizabeth Ann, held their little girl close as she was welcomed into the fold of the Christian faith. The grand stone walls of the church, filled with the quiet reverence of history, must have echoed with the soft promises made over the newborn child. The ritual was a gentle reminder that, despite the everyday hustle of life, some moments held deep, sacred meaning, a promise of protection, hope, and community.

James, who stood by as both father and provider, gave his occupation as a Diamond Merchant, a testament to the life he had carved out for himself in the world of precious stones. His work was one of finesse and refinement, where elegance met business, and it spoke volumes about the life he wanted for his children. Their home, nestled at 60 Lansdowne Road, Kensington, was a reflection of this quiet prosperity, stable, comfortable, and in the heart of a vibrant, bustling neighborhood. It was a home where James, despite the demands of his work, could always return to a family that grounded him. Once again, in the official records, James used his middle name, William, as his first name, presenting himself as William James. It’s an intriguing glimpse into the modesty of the time, where names often carried not only family traditions but personal choices, hinting at deeper layers of identity.

As Emily Beatrice was christened, one can imagine the soft glow of the candlelight, the quiet whispers of the congregation, and the tender love of her parents. Emily, with her delicate name and fresh innocence, was ready to take her place in a world filled with both promise and complexity.

In that church, on that October day, the Willats family’s legacy was further etched into the annals of history. The gentle chime of the church bell that day must have been heard far beyond the walls of St John’s, carrying with it the weight of family, faith, and the enduring bond that would see Emily Beatrice through all the seasons of her life.

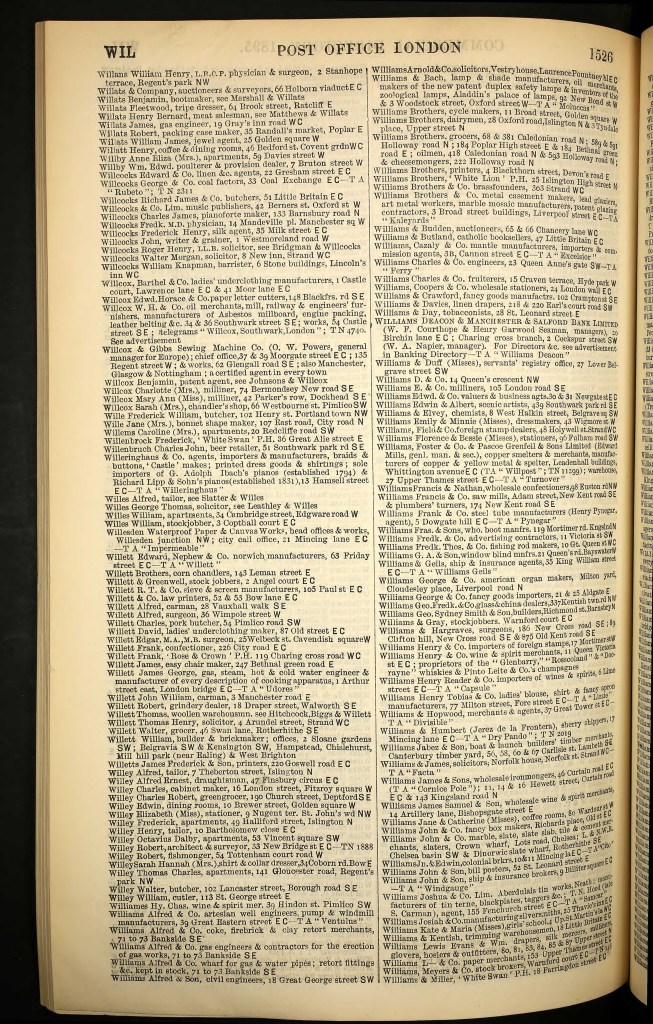

In the 1870 Trade Directory, James is listed as a Jewellery Agent, conducting his business from the bustling heart of London at 25 Golden Square, Soho. This address places him amidst the lively streets of a city known for its elegance and commerce, where he likely forged connections and built his reputation in the glittering world of fine jewellery.

In 1870, Golden Square was a prominent square located in the heart of the West End of London, England. It is situated in the district of Soho, which has a long history of being associated with entertainment, music, and the arts. Golden Square itself was known for its elegance and was considered one of the more fashionable areas of London during the Victorian era.

The square was surrounded by beautiful Georgian townhouses, many of which were inhabited by wealthy families, merchants, and professionals. These residences were built with a distinctive architectural style, featuring grand facades, ornate balconies, and well-manicured gardens. The area was highly sought after due to its central location and proximity to various theaters, music halls, and social clubs, making it a vibrant and bustling part of the city.

During this period, London was undergoing significant industrialization and urbanization, leading to a stark contrast between the wealth and luxury of Golden Square and the poverty-stricken areas nearby. The working-class neighborhoods, which included overcrowded tenements and slums, were in stark contrast to the opulence and grandeur of Golden Square.

In addition to its residential character, Golden Square also served as a commercial hub, with various businesses, shops, and offices lining its streets. As a testament to its significance, the square attracted notable figures of the time, including artists, writers, and socialites who would often frequent its elegant cafes and social venues.

Though Golden Square has evolved significantly since 1870, some of its historical architecture and charm remain. Many of the original Georgian buildings have been preserved and restored, adding to the area’s appeal and maintaining a connection to its rich past.

Today, Golden Square continues to be an attractive location in London, with a mix of residential and commercial properties, bustling with activity, and still reflecting some of its historical charm amid the modern cityscape.

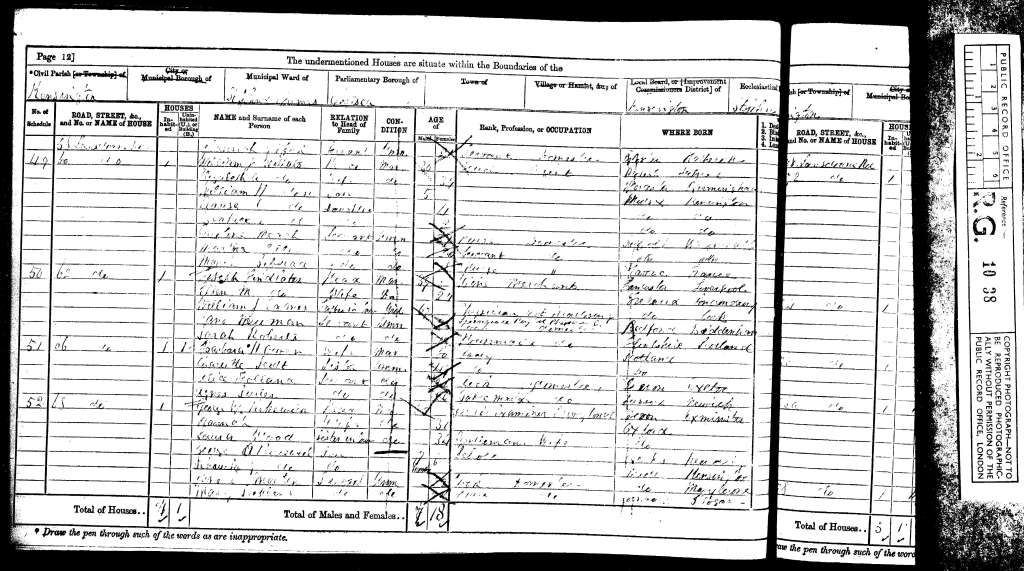

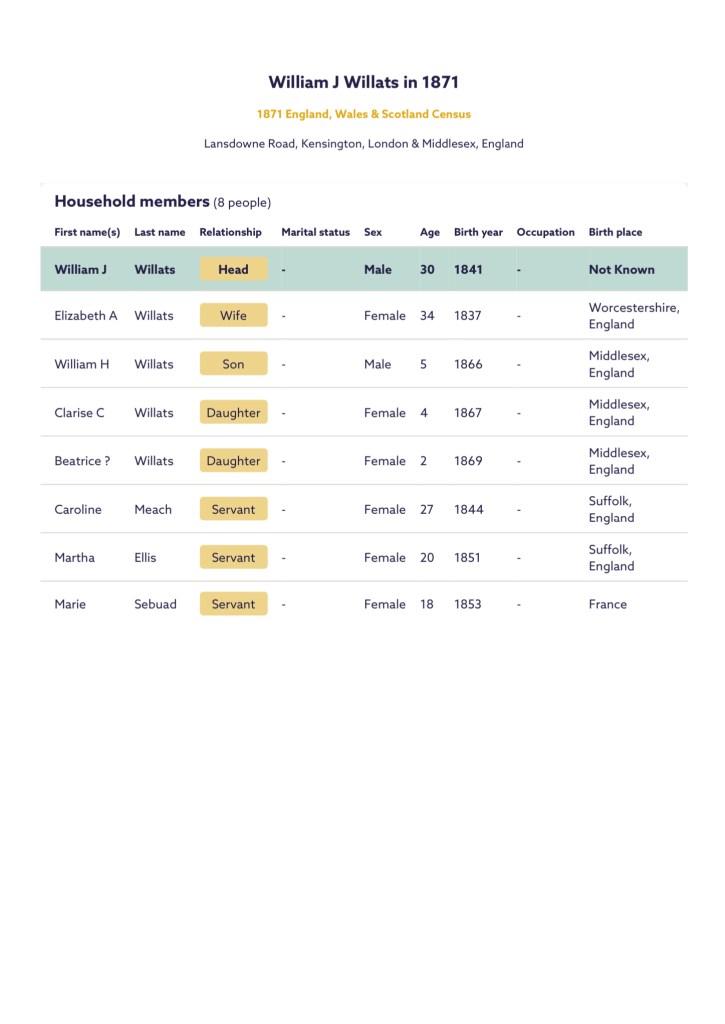

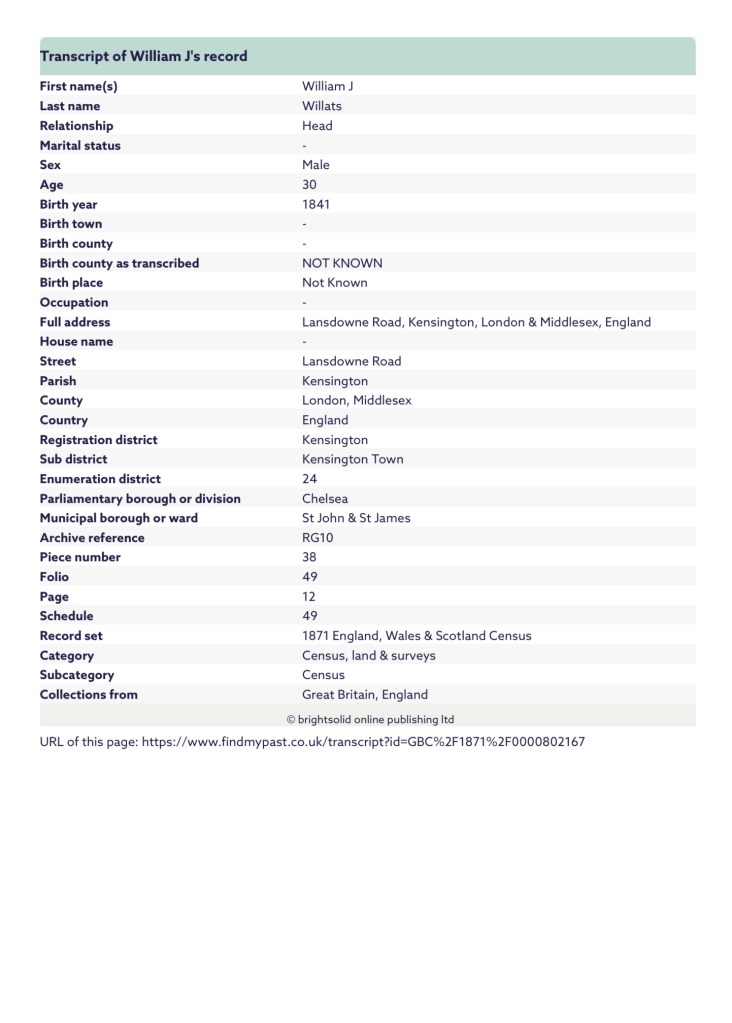

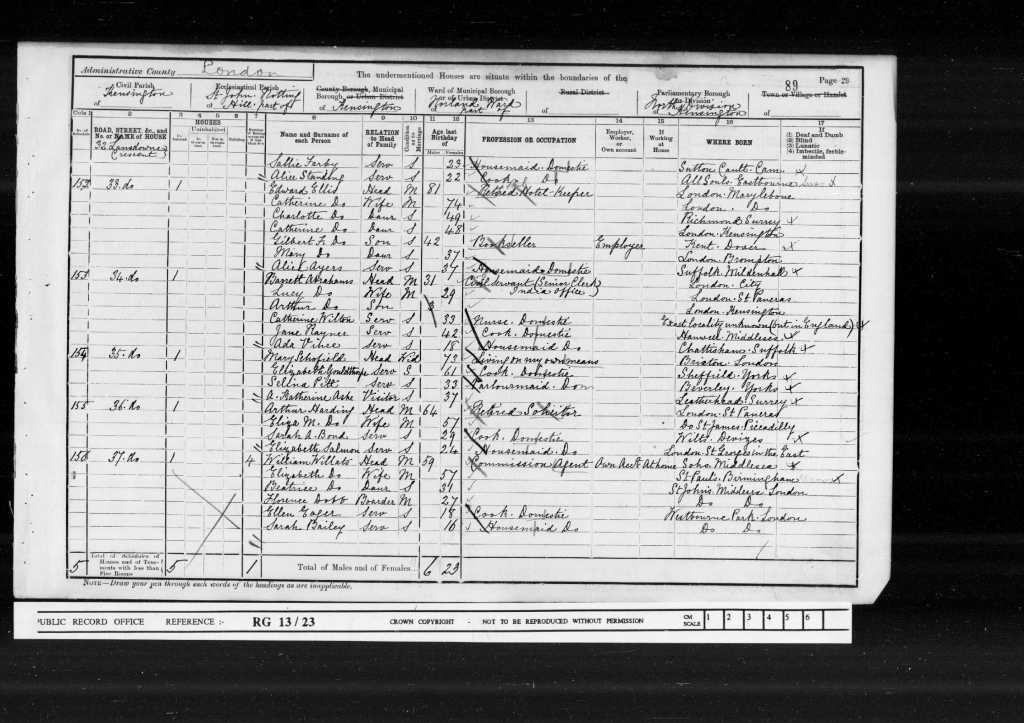

On Sunday, April 2, 1871, James was living with his beloved wife, Elizabeth, and their children, William H., Clariss C., and Emily Beatrice, at a comfortable home on Lansdowne Road in Kensington, London. Their household was bustling, not just with family but also with the presence of three dedicated servants: 28-year-old Caroline Meach, 20-year-old Martha Ellis, and 18-year-old Marie Sebuad. Each of them likely played a role in supporting the family’s day-to-day life.

James was listed as working as a Jewel Agent, a profession that reflected his connection to the world of fine craftsmanship and beauty. Interestingly, during this time, he once again adopted the name William, a detail that adds an intriguing layer to his story and leaves us pondering the reasons behind this choice. Their home must have been filled with both the lively energy of children and the quiet industriousness of a family building their future together.

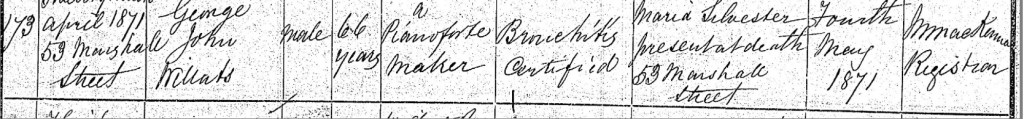

With great sadness, we reflect on the passing of George John Willats, the cherished father of James. George departed this life on Saturday, April 29, 1871, at the age of 66, at his home at 53 Marshall Street, Golden Square, Westminster, London. He succumbed to bronchitis, a struggle that marked his final days.

By his side in his last moments was Maria Silvester, also of 53 Marshall Street, who tenderly ensured his death was registered on Thursday, May 4, 1871. When speaking of George, Maria lovingly noted his lifelong craft as a Pianoforte maker, a profession that no doubt brought music and joy to many.

George’s passing leaves a profound void in the hearts of those who knew and loved him. His legacy lives on in the echoes of his life’s work and in the memories of his family and friends, who mourn the loss of a kind and dedicated man.

On Wednesday, May 3, 1871, George John Willats was tenderly laid to rest in Pancras Cemetery, Camden, London. His grave, E10/39, became a shared resting place with 12 other dear souls, a testament to the interconnectedness of lives, even in eternal peace.

Though his final resting place is humble, the love and memories he left behind resonate deeply in the hearts of his family and those who knew him. George’s journey on this earth may have come to an end, but his legacy and spirit endure, cherished by those who carry his story forward.

Pancras Cemetery, located in Camden, London, holds a rich and fascinating history, deeply entwined with the evolution of burial practices in 19th-century England. Established in 1854, it was one of the earliest municipal cemeteries in London, created during a period when urban churchyards had become dangerously overcrowded. This overcrowding, combined with concerns about public health and sanitation, prompted the introduction of larger burial grounds on the outskirts of the city.

The cemetery was originally established to serve the parish of St. Pancras and quickly became a significant resting place for many Londoners, reflecting the diverse and growing population of the area. The cemetery’s layout was designed with both functionality and aesthetics in mind, offering a peaceful and dignified space for mourning and reflection. Its picturesque design, characterized by winding paths, mature trees, and thoughtfully arranged graves, follows the Victorian tradition of creating cemeteries as tranquil, park-like environments.

Pancras Cemetery is notable not only for its role in accommodating London’s deceased but also for its historical and architectural features. The cemetery chapel, built in the Gothic Revival style, served as a centerpiece and a space for funerary services. Over the years, the cemetery became the final resting place for people from all walks of life, from everyday citizens to individuals of notable social, cultural, and historical significance.

Like many Victorian cemeteries, Pancras Cemetery reflects the changing attitudes toward death and commemoration during the 19th century. Elaborate headstones, mausoleums, and epitaphs reveal the era’s focus on memorialization and the desire to honor the deceased. However, as the decades passed, some parts of the cemetery fell into neglect, reflecting the broader societal shifts in attitudes toward older burial grounds.

Today, Pancras Cemetery is part of a larger conservation area and is valued not only as a burial ground but also as a space of historical and cultural importance. It provides insight into the lives and deaths of Londoners over the centuries and serves as a poignant reminder of the city’s past. Visitors to the cemetery often find it a place of quiet contemplation, where history and memory converge amidst the natural beauty of the grounds.

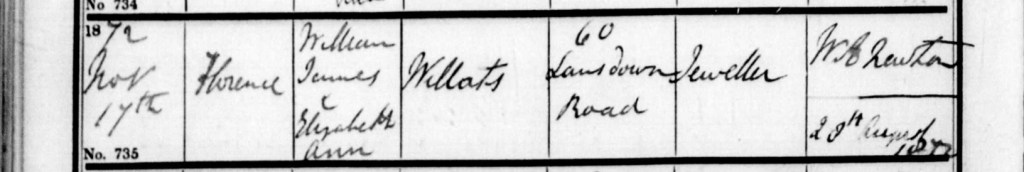

The following year brought joy and new life to the Willats family. On August 28, 1872, James William and Elizabeth Ann Willats (née Davis) welcomed their daughter, Florence Willats, into the world. She was born at their family home, 60 Lansdowne Road, Kensington, London, a place that must have been filled with excitement and love as they embraced this precious addition to their family.

On September 26, 1872, James took on the proud and tender responsibility of registering Florence’s birth. In doing so, he listed his profession as a Jewel Agent and reaffirmed their address as 60 Lansdowne Road, Notting Hill. Ever enigmatic, James once again chose to present himself under the name William James Willats, using his middle name as his first.

This moment marked a special chapter in the family’s story, a time of hope, growth, and the quiet happiness that a newborn brings into a home. Florence’s arrival surely deepened the bonds of love within their household, as her parents celebrated the gift of her life.

On a Sunday morning, November 17, 1872, James William and Elizabeth Ann Willats brought their infant daughter, Florence, to be baptized at St. John’s Church in Notting Hill, Kensington. The sacred ceremony marked a moment of deep commitment and joy, as they welcomed Florence into their faith and community with love and hope for her future.

At this significant occasion, James was listed as a Jeweller, a profession that reflected his connection to craftsmanship and beauty. The family’s home at 60 Lansdowne Road in Kensington was noted once more, grounding them in a neighborhood that had become a central part of their lives. Ever the enigmatic figure, James again chose to present himself as William James.

This day at St. John’s Church must have been filled with emotion for James and Elizabeth, a moment of gratitude for their daughter’s safe arrival and the opportunity to bless her life in the company of their faith and tradition.

In the 1875 Trade Directory, James is listed as working as a Jeweller Agent, carrying out his trade from 25 Golden Square in the vibrant heart of Soho, London. This address, nestled within the bustling streets of a thriving city, reflects a life devoted to the intricate and elegant world of fine jewelry.

One can imagine James moving through the lively square, engaging with clients and craftsmen, his days filled with the sparkle of gemstones and the hum of commerce. His work at Golden Square speaks to his dedication and skill, as well as the connections he built in a city renowned for its artistry and trade.

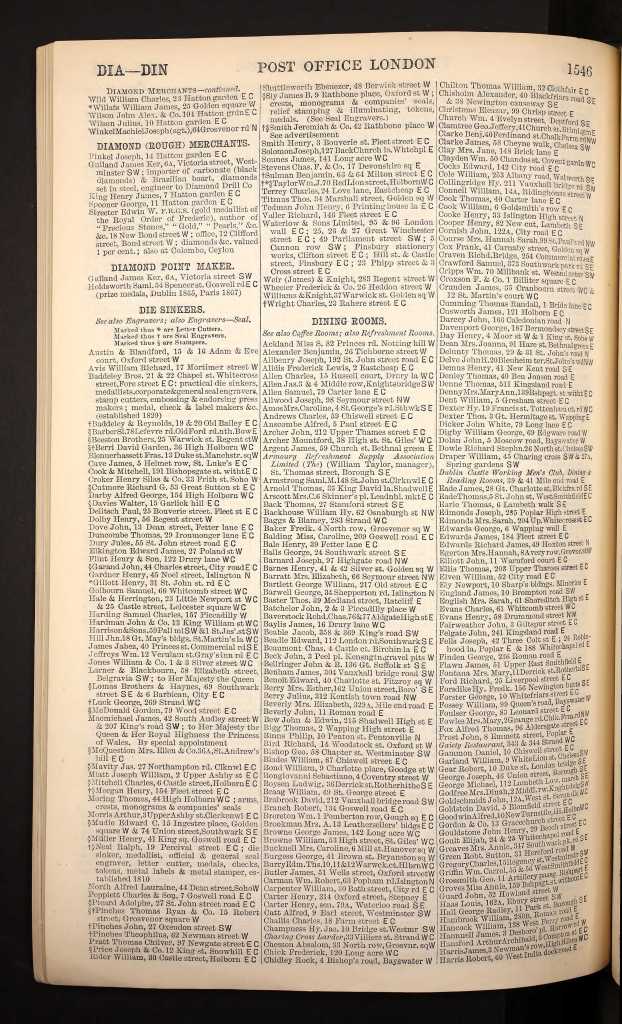

In the 1880 Trade Directory, James’ name appears among the esteemed Diamond Merchants, proudly listed at 25 Golden Square in Soho, London. This recognition marks a new chapter in his career, reflecting his growing reputation and expertise in the glittering world of diamonds.

At Golden Square, amidst the energy and creativity of Soho, James was likely surrounded by the finest gemstones, handling them with care and precision. His work as a diamond merchant would have been a testament to his skill, ambition, and the trust he had earned within the industry. The address at Golden Square, now forever linked with his name, speaks of a life dedicated to the pursuit of beauty and craftsmanship, a life woven into the very fabric of London’s vibrant trade scene.

Being a diamond merchant in the Victorian era was an endeavor that required a unique blend of business acumen, cultural understanding, and social finesse. This profession involved several key aspects that contributed to a successful and esteemed position in society. Here are a few of the key elements involved in being a diamond merchant during this time.

Sourcing Diamonds: Diamond merchants in the Victorian era had to travel extensively to source the finest diamonds from various parts of the world. Regions like India, South Africa, and Brazil were significant sources of diamonds during this time. Establishing relationships with local diamond miners and traders was crucial to access the best and most sought-after gems.

Expertise in Gemology: A diamond merchant needed a deep understanding of gemology, including knowledge about diamond grading, the 4 Cs (cut, color, clarity, and carat weight), and gem identification. This expertise allowed them to accurately evaluate the quality and value of diamonds and ensure they offered only the most exquisite pieces to their clientele.

Art of Negotiation: The diamond trade was competitive, and skilled negotiation was essential to secure the best deals when buying diamonds from miners or traders. It required shrewd business skills to strike profitable agreements while maintaining respectful relationships with suppliers.

Collaboration with Artisans: Once the diamonds were acquired, the merchant collaborated with skilled jewelers and designers to create exquisite jewelry pieces. This involved sharing ideas, sketches, and specifications to ensure the final product met the expectations of both the merchant and the client.

Design and Trends: Keeping abreast of the latest trends in jewelry design was vital. The Victorian era saw a wide range of jewelry styles, from romantic and delicate pieces inspired by nature to bold and intricate designs showcasing status and wealth. Understanding the preferences of their clientele and predicting upcoming trends helped merchants stay ahead in the market.

Networking and Social Etiquette: Victorian society was structured with a strict social hierarchy, and being part of the upper class was crucial for a successful diamond merchant. Networking at exclusive events, attending social gatherings, and being part of elite clubs allowed merchants to meet potential clients and showcase their latest acquisitions.

Brand and Reputation: Building a reputable brand was paramount to gain the trust and loyalty of clients. A diamond merchant had to be known for dealing in genuine and high-quality diamonds, impeccable craftsmanship, and outstanding customer service. Word of mouth played a significant role in promoting their business.

Salesmanship: Convincing potential buyers of the beauty and value of diamonds required excellent salesmanship. Merchants often used storytelling, highlighting the diamond’s origin, history, and rarity, to create an emotional connection with their clients.

Adapting to Changing Times: The Victorian era saw significant cultural and societal changes. As a diamond merchant, adapting to these changes and catering to the evolving tastes of their clients was vital for sustained success. Ethical Considerations: Ethical practices in the diamond trade have always been important. During the Victorian era, merchants were expected to ensure that the diamonds they traded were obtained legally and without exploitation or harm to local communities and the environment.

In conclusion, being a diamond merchant in the Victorian era was a multifaceted profession that demanded not only a keen eye for exquisite gems but also a deep understanding of the social nuances and business dynamics of the time. The allure of diamonds, combined with the art of negotiation and refined social skills, made this profession a symbol of elegance and sophistication in the opulent Victorian society.

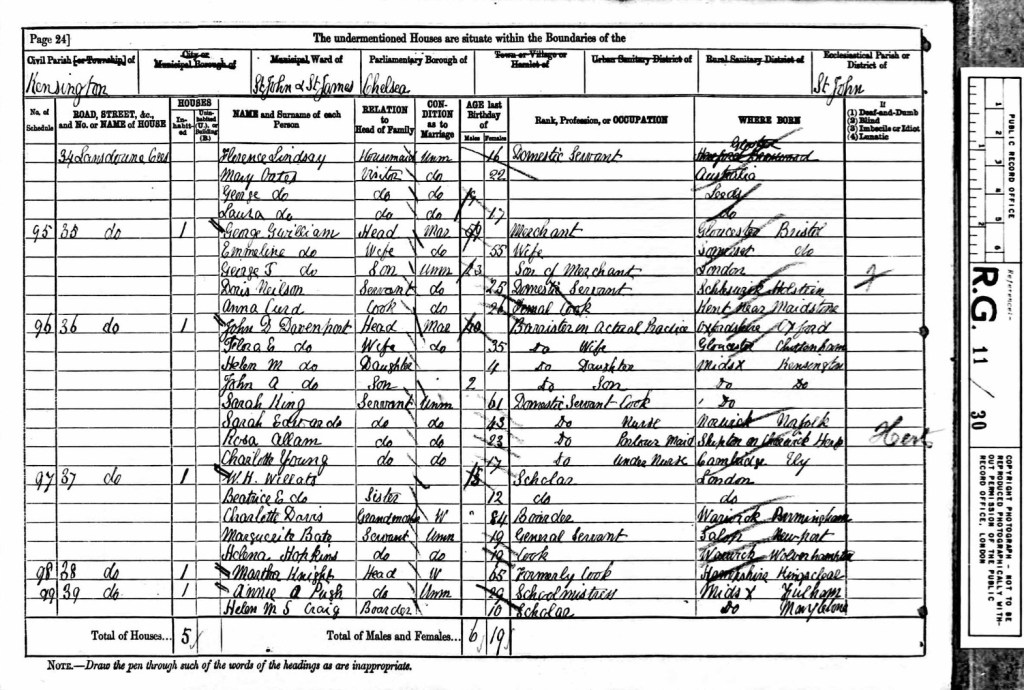

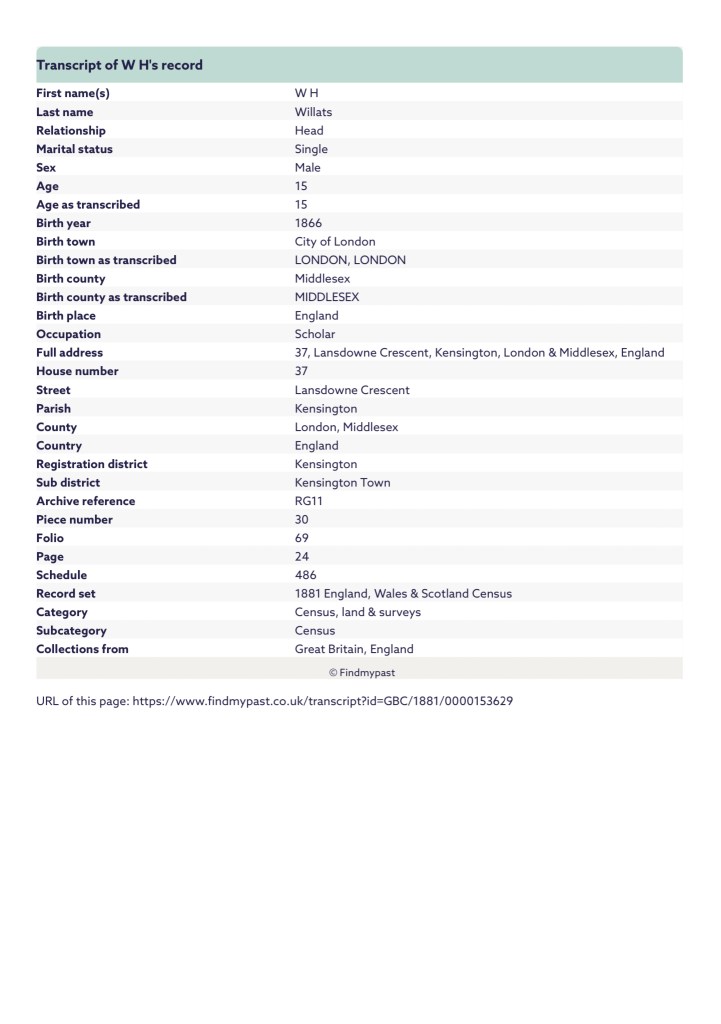

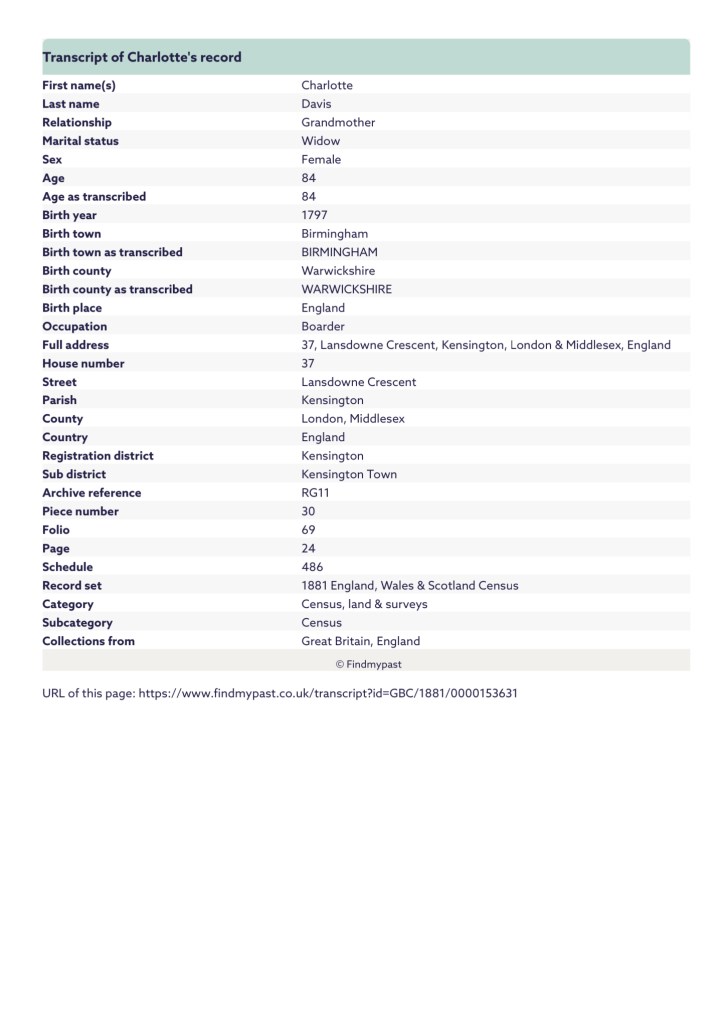

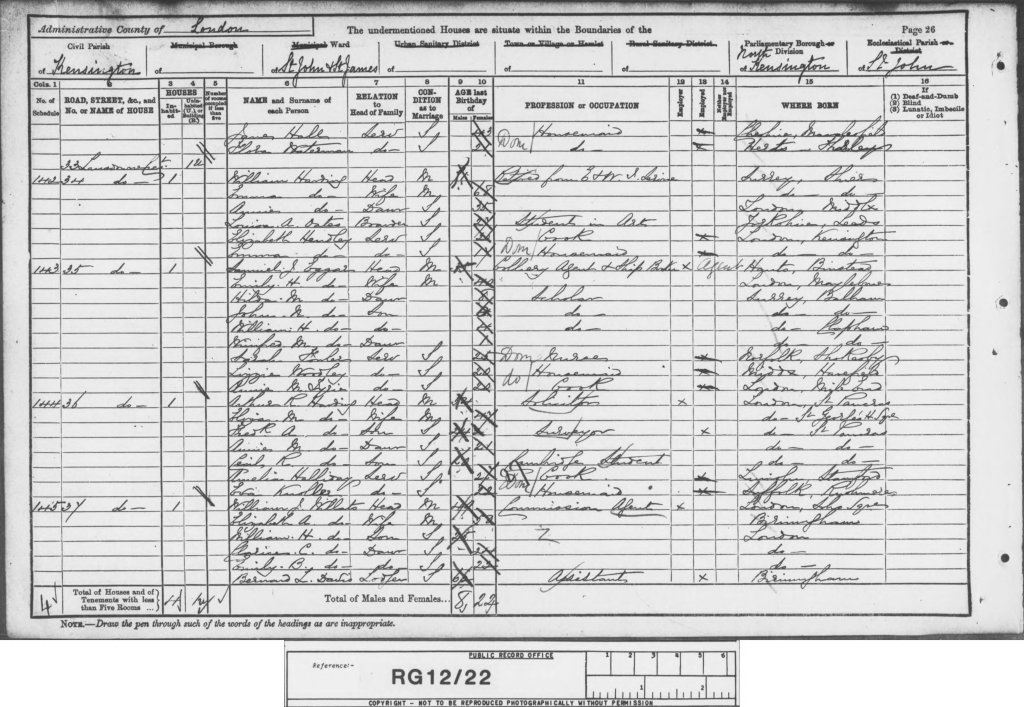

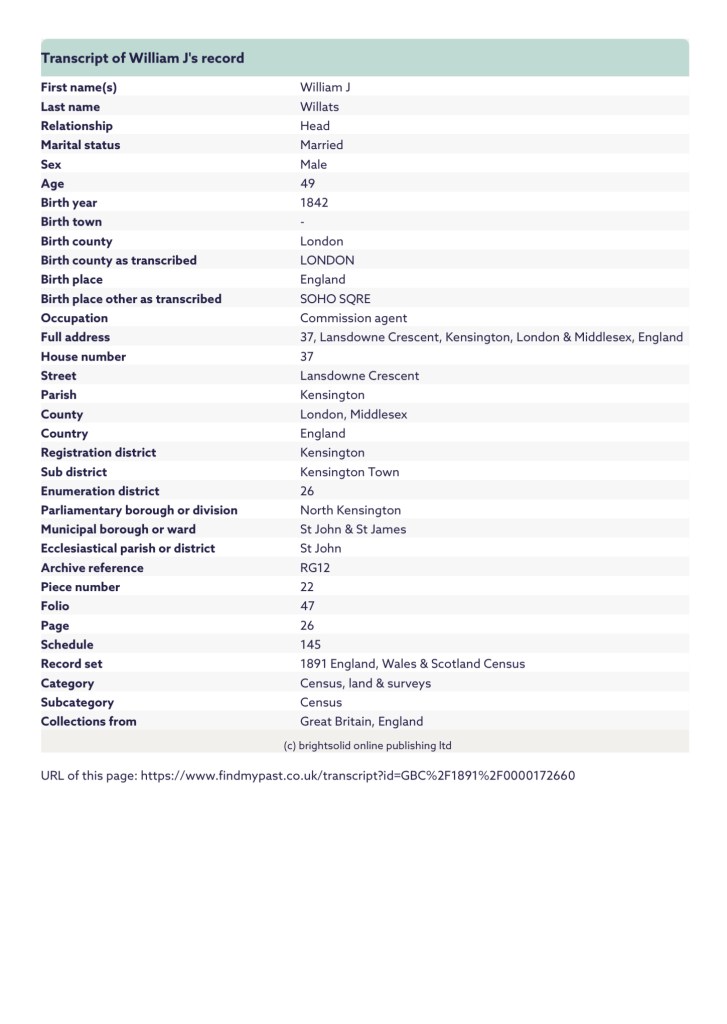

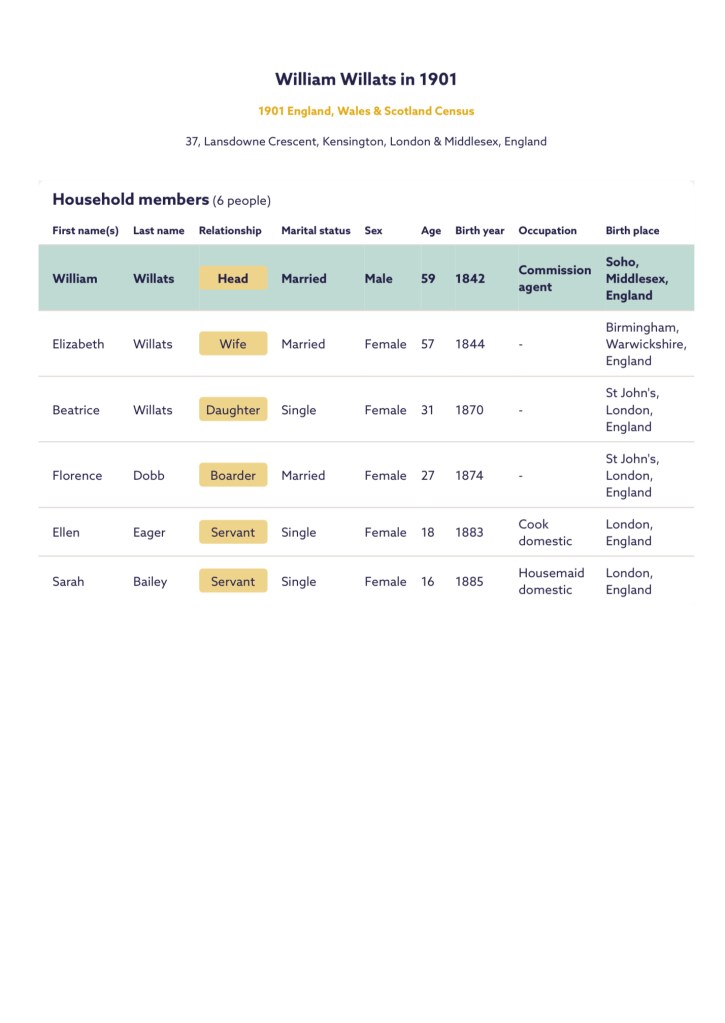

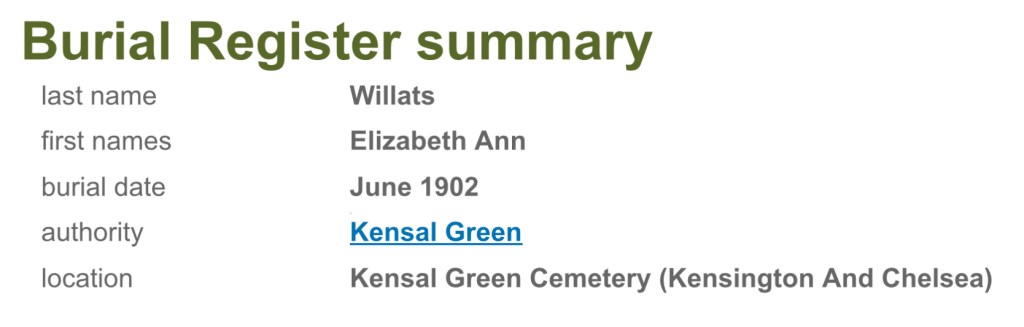

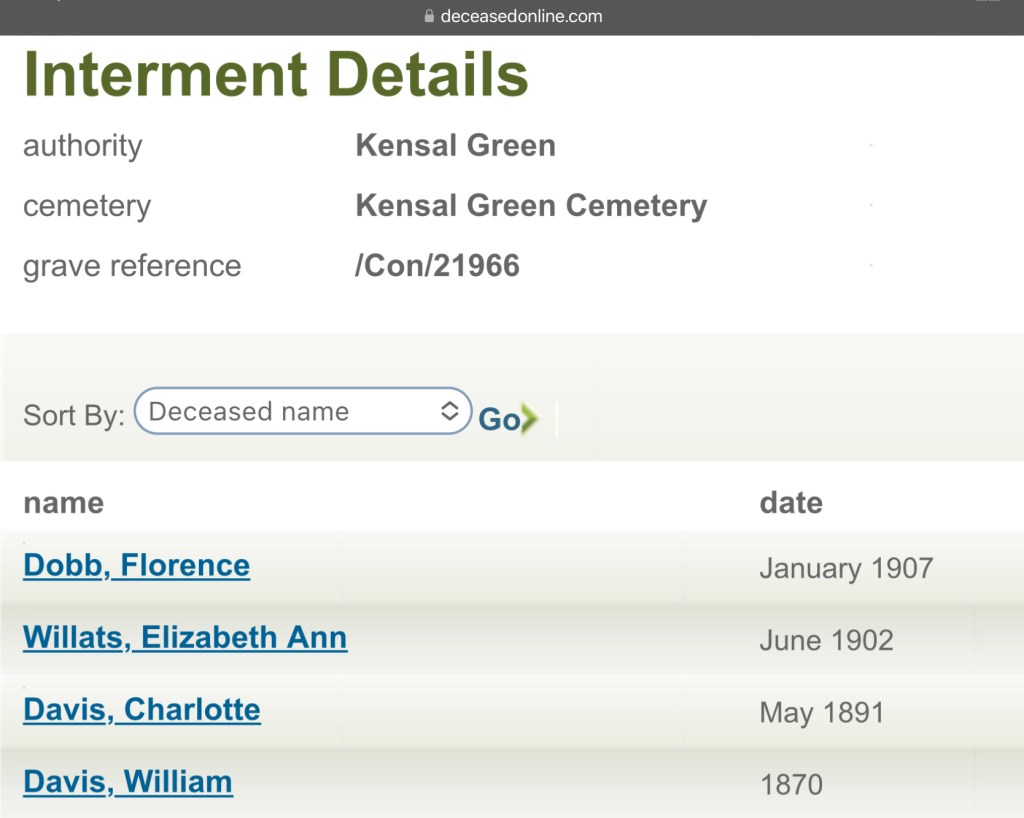

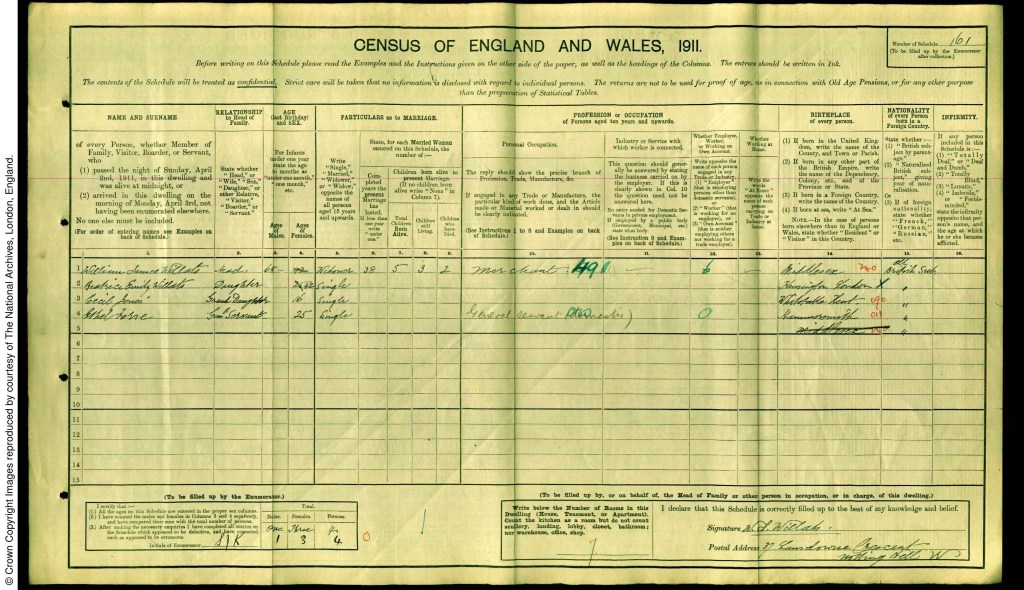

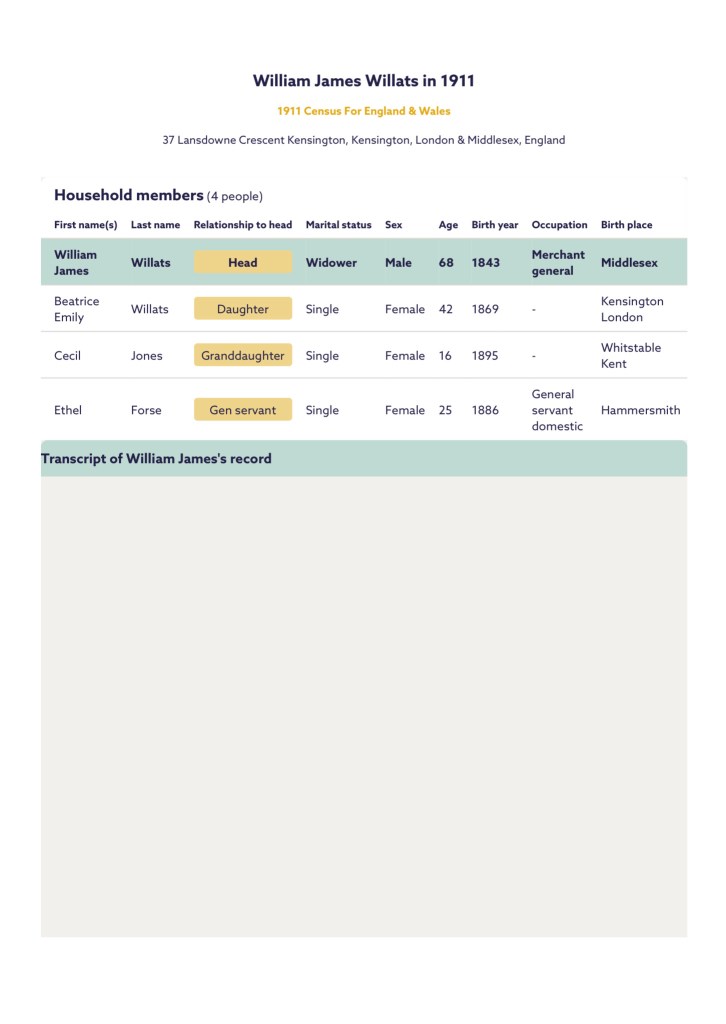

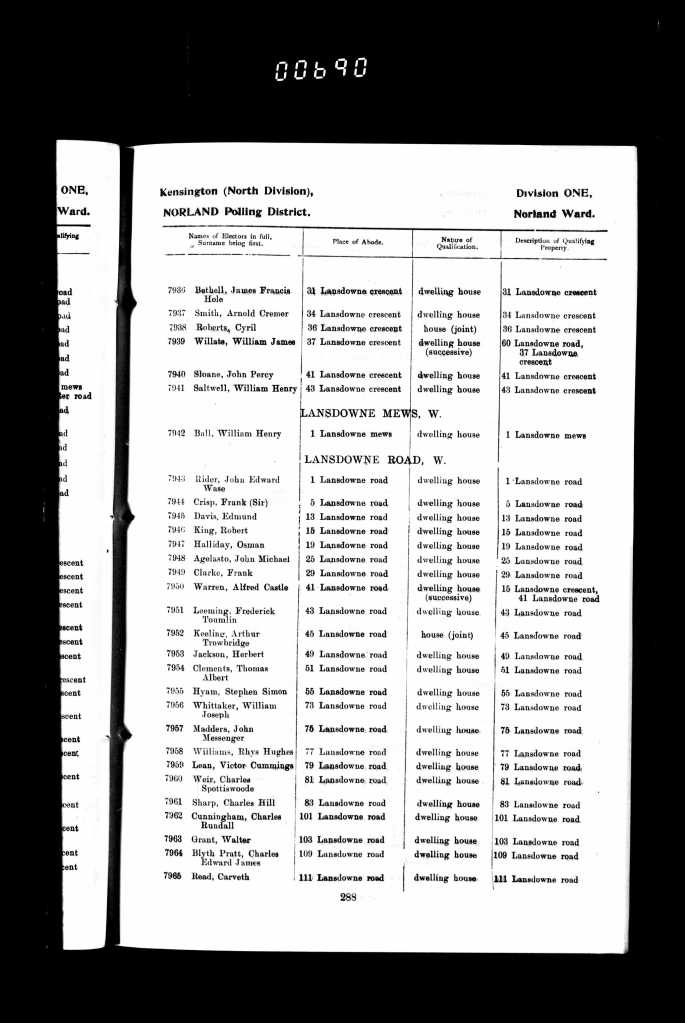

In the 1881 Census, James and Elizabeth seem to have vanished from the records, leaving us to wonder where they might have been at the time. However, their two children, William and Emily Beatrice, were living at the family home, 37 Lansdowne Crescent, in the charming area of Notting Hill, Kensington. They were under the loving care of their grandmother, Charlotte Davis (née Smith), James’ mother-in-law.

Charlotte, listed as a boarder in the household, provided a sense of continuity and family presence. William and Emily were both attending school, their bright futures unfolding in the embrace of their grandmother’s nurturing care. The household also had two young servants, 19-year-old Marguerite Bate, a general servant, and 19-year-old Helena Hopkins, a cook, helping maintain the home.

The absence of James and Elizabeth during this period raises questions. Were they abroad, perhaps on business or traveling for reasons unknown? Or were they simply visiting family or friends? Whatever the case, it’s clear that William and Emily were surrounded by the warmth of family, even in their parents’ absence.

Lansdowne Crescent, situated in Notting Hill within the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea, London, is a notable example of mid-19th-century residential development. Constructed between 1860 and 1862 by the Wyatt family, the crescent is named after Henry Petty-Fitzmaurice, the 3rd Marquess of Lansdowne, who held prominent political positions including Chancellor of the Exchequer and Home Secretary.

The crescent is characterized by its distinctive architecture, comprising stuccoed terraced houses with bow fronts and classical detailing. The two segments of the terrace, encompassing numbers 19–28 and 29–38, are recognized for their architectural significance and have been designated as Grade II listed buildings.

A prominent landmark within Lansdowne Crescent is St John's Notting Hill, a Victorian Gothic church completed in 1845. Designed by architects John Hargrave Stevens and George Alexander, the church was intended to serve as the focal point of the Ladbroke Estate, a 19th-century housing development aimed at attracting affluent residents to what was then a suburban area of London.

Regarding number 37 Lansdowne Crescent, specific historical details are limited. However, it is part of the terrace constructed during the 1860s and shares the architectural features that contribute to the crescent's overall heritage value. The listing of numbers 29–38 as Grade II buildings underscores the importance of this segment in the architectural tapestry of the area.

Lansdowne Crescent has been home to notable residents over the years. For instance, the renowned rock guitarist Jimi Hendrix spent his final hours at the Samarkand Hotel, located at 22 Lansdowne Crescent, where he passed away on September 18, 1970.

The crescent's development is intertwined with the history of the Ladbroke Estate, which originally encompassed open fields and even a racecourse known as the Kensington Hippodrome in the 1830s. Following the closure of the racecourse, the area was developed into the residential neighborhood seen today, with Lansdowne Crescent forming a significant part of this transformation.

Today, Lansdowne Crescent remains a sought-after residential area, appreciated for its historical architecture and proximity to the vibrant cultural scene of Notting Hill. The preservation of its architectural heritage ensures that it continues to be a significant landmark within London's urban landscape.

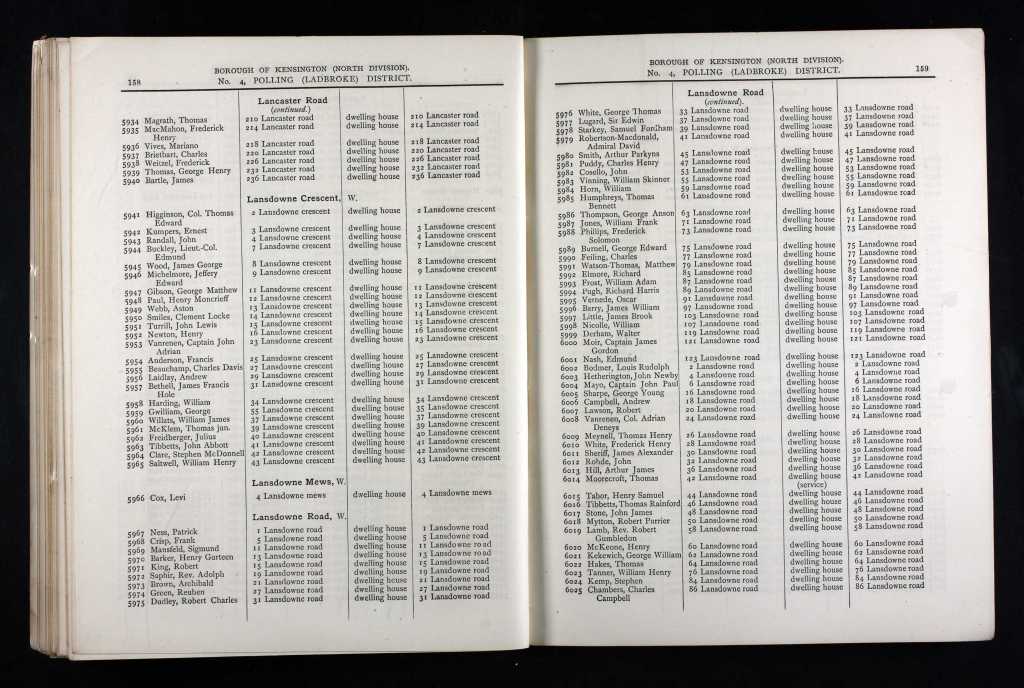

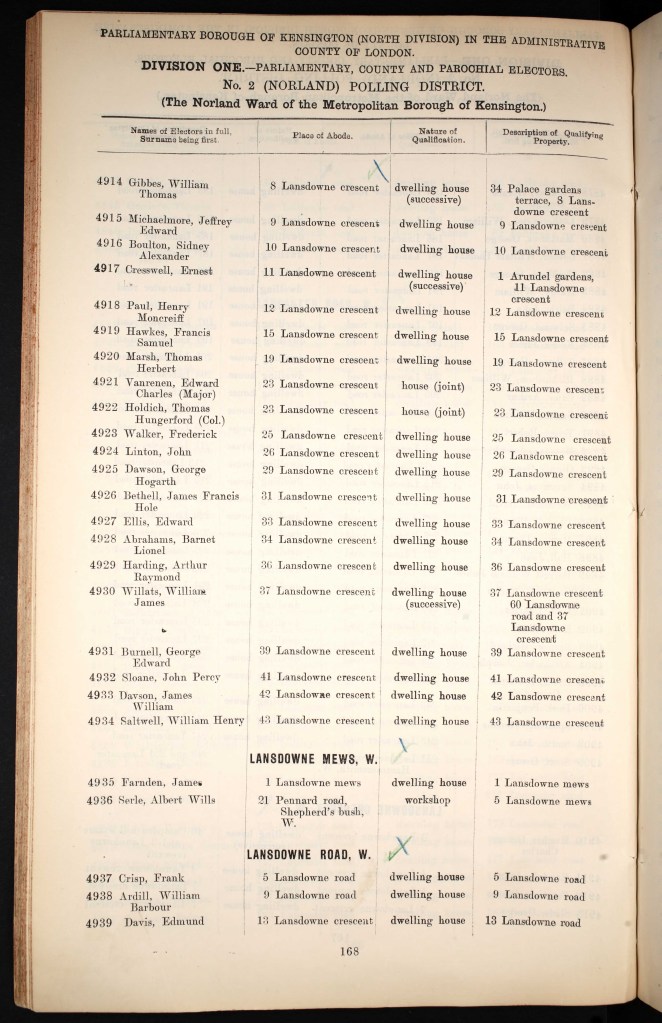

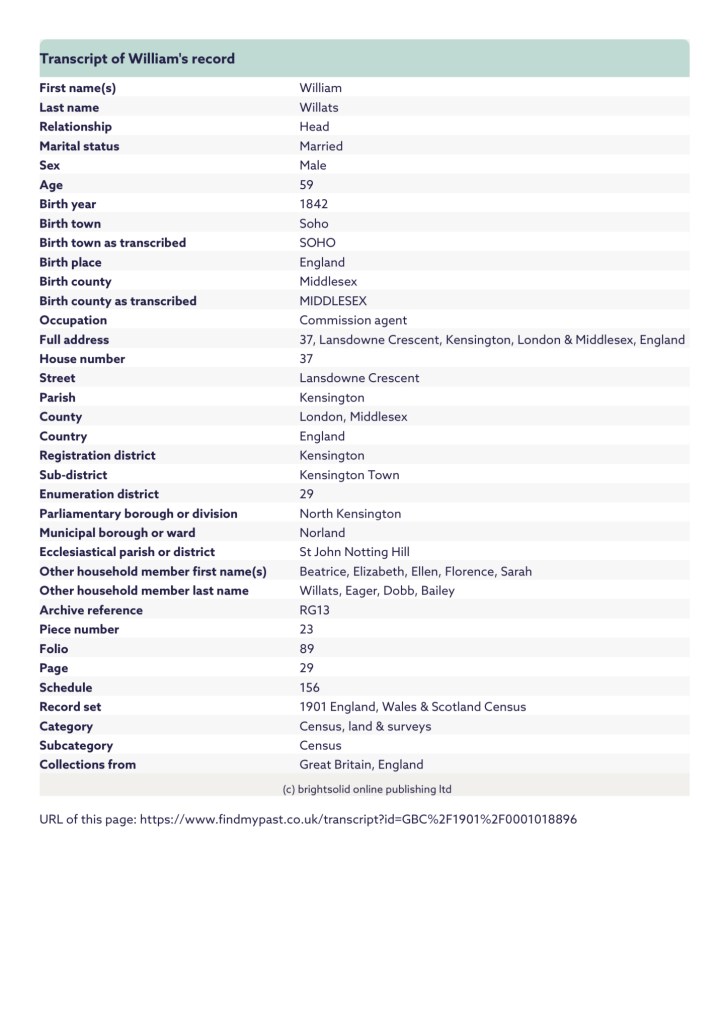

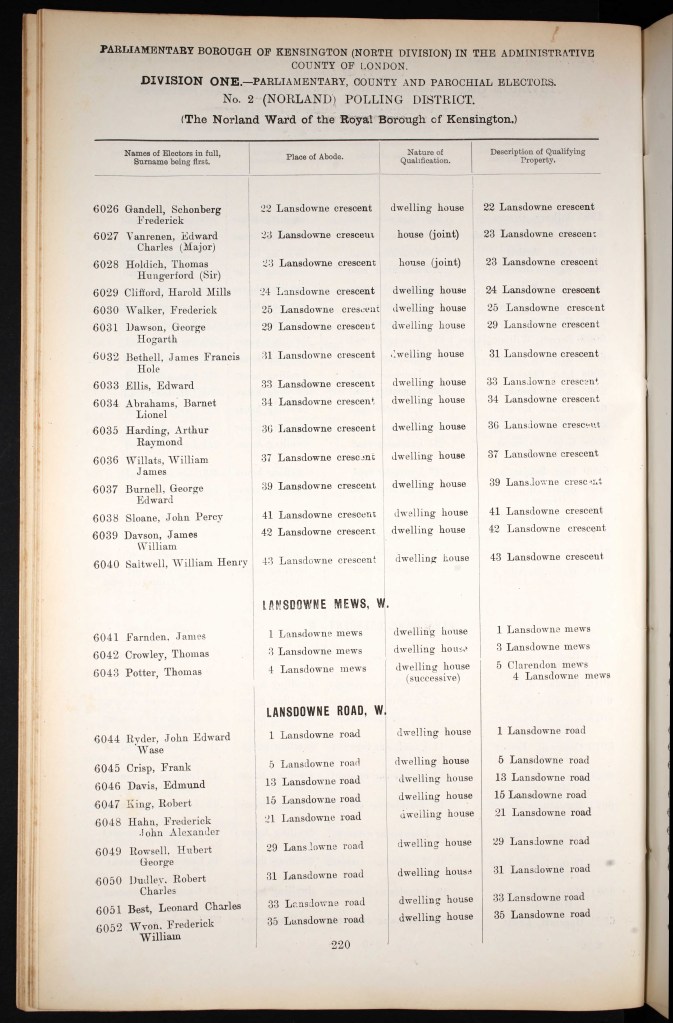

In the 1883 Electoral Registers for London, England, James is listed as residing at 37 Lansdowne Crescent, in the picturesque neighborhood of Notting Hill, Kensington. True to his enigmatic nature, he was once again using the name William, a name that seems to have held a special significance for him.

This record places James at the heart of the family home, a place that had witnessed both quiet domestic moments and lively family life. One can imagine him walking the charming streets of Notting Hill, deeply rooted in the rhythm of the neighborhood he called home. His presence in the Electoral Registers serves as a small but meaningful glimpse into his life during that time, a life filled with subtle mystery and enduring connection to those he loved.

In the 1884 Electoral Registers for London, James is once again listed as residing at 37 Lansdowne Crescent, the family home in the charming heart of Notting Hill, Kensington. As before, he is recorded under the name William, a detail that adds a touch of intrigue to his story. His continued presence at Lansdowne Crescent paints a picture of stability and connection, a man deeply rooted in his family’s life. It’s easy to imagine James, or William as he preferred, moving through the familiar surroundings of this vibrant neighborhood, his life interwoven with the home and community he held dear.

In 1888, James’s name appeared once more in the Electoral Register, tied to the family’s cherished home at 37 Lansdowne Crescent in Kensington, London. This enduring connection to Lansdowne Crescent speaks to a life anchored in the rhythms and relationships of this vibrant neighborhood. One can imagine James, a steady presence within these walls, shaping the home with his character and care. Whether he was tending to his business, spending time with his family, or simply enjoying the lively spirit of Kensington, this record reminds us of his place in the story of Lansdowne Crescent, a home filled with love, life, and the subtle mysteries that made him who he was.

Jumping forward to the year 1890, London was a city caught between the past and the future, buzzing with progress while grappling with the challenges of rapid urban growth. Queen Victoria was the reigning monarch, her rule firmly cemented as the longest in British history. The prime minister at the time was Lord Salisbury, a conservative statesman steering the country through an era of industrial innovation and imperial ambition. The halls of Parliament in Westminster echoed with debates about reform, modernity, and the role of Britain on the world stage.

Transportation in London was transforming. Horse-drawn omnibuses and hansom cabs still dominated the streets, their rhythmic clatter mingling with the hum of steam-powered trains arriving and departing from stations like Paddington and King’s Cross. The city’s Underground, already a marvel of its time, had expanded, offering Londoners a glimpse of what a modern, interconnected city could look like. Yet, despite these advances, the streets were often congested and chaotic, filled with a mix of pedestrians, vendors, and carriages.

Sanitation remained a pressing issue. Although great strides had been made since the infamous "Great Stink" of 1858, overcrowding and poverty in the poorer districts meant that not everyone benefited from the city’s advancements. Efforts to improve living conditions were underway, with clean water systems and sewerage networks being expanded, but life in the slums of East London was harsh and unforgiving.

Heating and lighting in homes were undergoing a transformation. Gas lighting illuminated streets and houses, casting a soft, flickering glow, while wealthier homes began experimenting with the wonders of electricity. Heating remained dependent on coal fires, their warm glow a comfort during long, damp winters, even as they contributed to the ever-present smog that hung over the city.

The atmosphere in London was a mixture of excitement and tension. The city was alive with innovation, but the rapid pace of change left some feeling nostalgic for simpler times. Social inequality was starkly visible, with lavish parties in Mayfair contrasting sharply with the struggles of families in Whitechapel. Gossip filled the air, with tales of Jack the Ripper, whose reign of terror had only recently ended, still whispered in fear and fascination.

Fashion in 1890 was a spectacle of elegance and formality. For women, corsets, bustles, and layered skirts were all the rage, creating dramatic silhouettes that reflected Victorian ideals of femininity. Men’s fashion leaned toward tailored suits with waistcoats and pocket watches, exuding a sense of respectability and decorum. The streets of London were a living fashion parade, as the upper classes showcased their wealth through elaborate attire.

Entertainment offered an escape from the daily grind. Music halls were wildly popular, offering a blend of comedy, song, and spectacle to audiences across the city. Theatres in the West End staged performances that drew crowds eager to be dazzled by the drama and artistry of the age. For those who could afford it, evenings at the opera or ballet were events to be savored, while public parks and fairs provided simple pleasures for the masses.

Education was becoming more accessible, thanks to the 1870 Elementary Education Act, which had laid the groundwork for compulsory schooling. By 1890, more children were learning to read and write, though opportunities for advanced education remained limited to the privileged few. Libraries and reading rooms were growing in popularity, providing a space for intellectual curiosity and self-improvement.

Food in 1890 reflected London’s status as a global city. Markets brimmed with goods from the far corners of the British Empire—spices from India, tea from Ceylon, and exotic fruits like pineapples and bananas. For the working classes, meals were simple but hearty, often consisting of bread, cheese, and stews, while the upper classes enjoyed lavish dinners served in courses, complete with elaborate desserts and fine wines.

Historically, 1890 was a year of both consolidation and transformation. The Industrial Revolution had reshaped not just London but the entire world, and Britain’s empire was at its zenith, its influence touching nearly every continent. Yet beneath the grandeur lay the seeds of change. Social reformers were calling attention to inequality, women were beginning to demand more rights, and technological advancements hinted at an even more dynamic future.

To step into London in 1890 was to experience a city at a crossroads, one foot firmly planted in the traditions of the past, the other reaching toward the promises of the modern age. It was a place of contrasts, where innovation and inequality coexisted, but above all, it was a city alive with the energy of possibility.

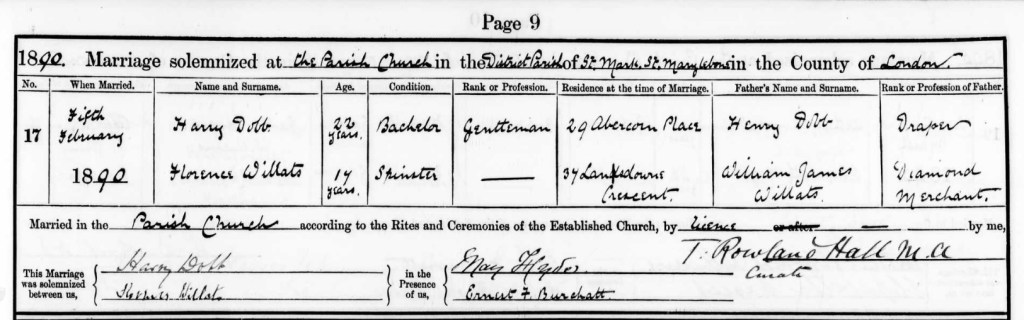

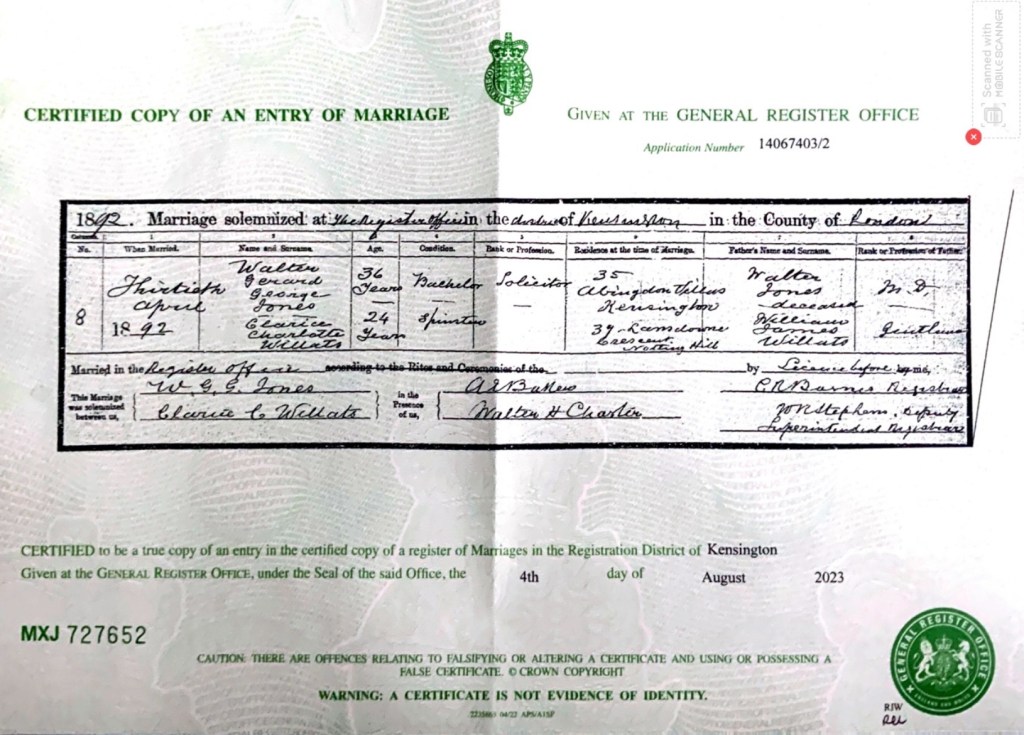

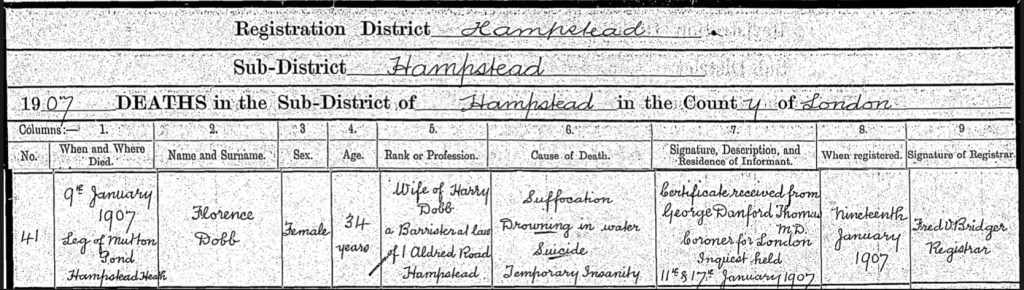

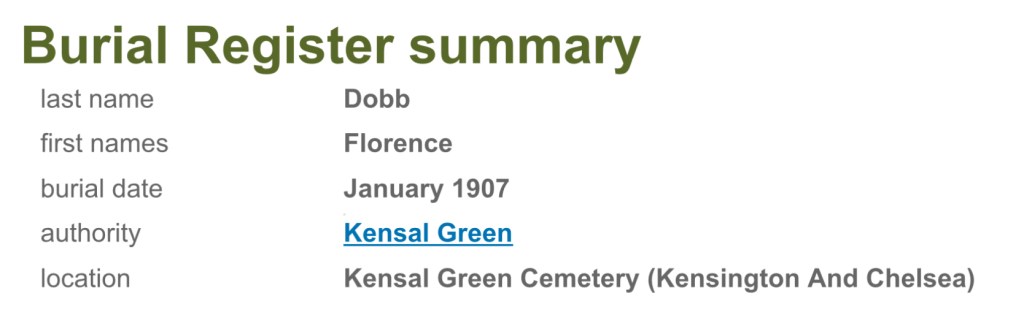

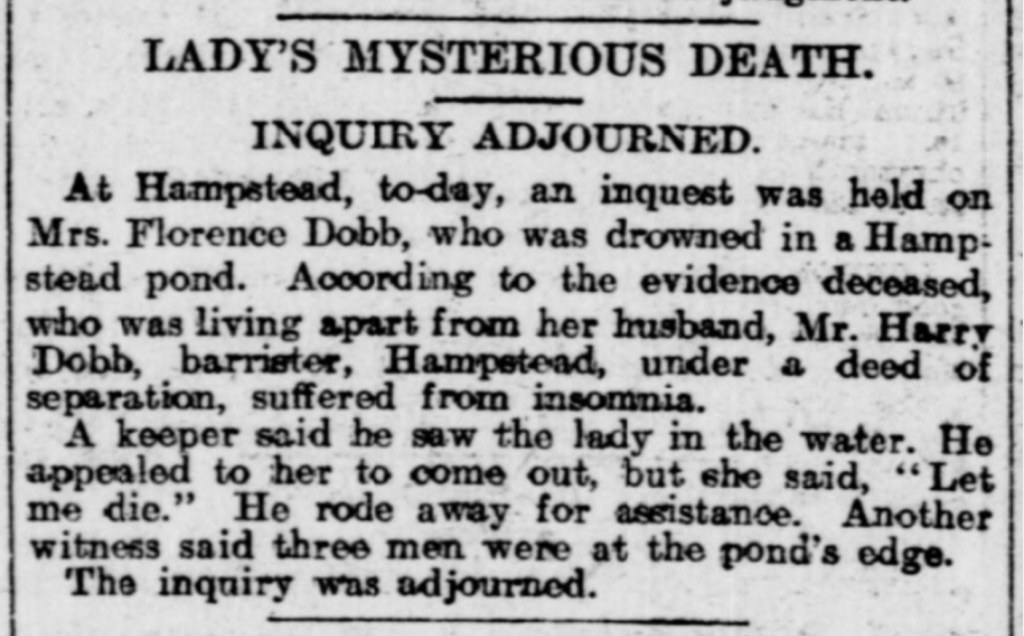

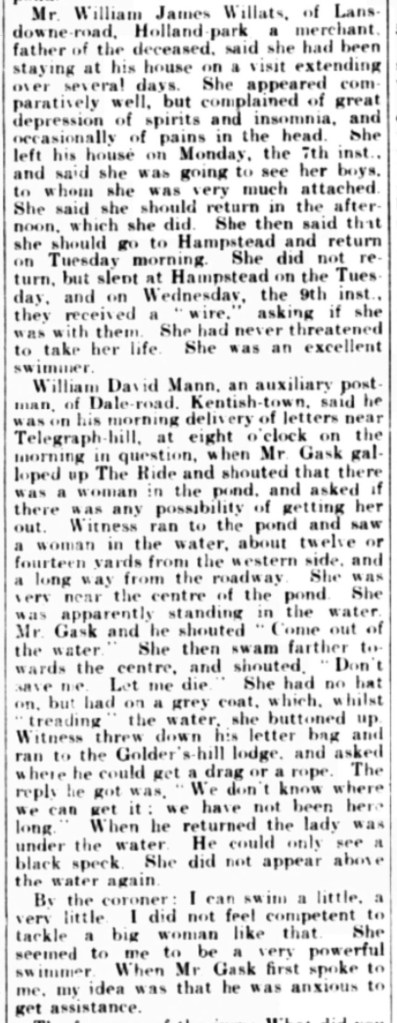

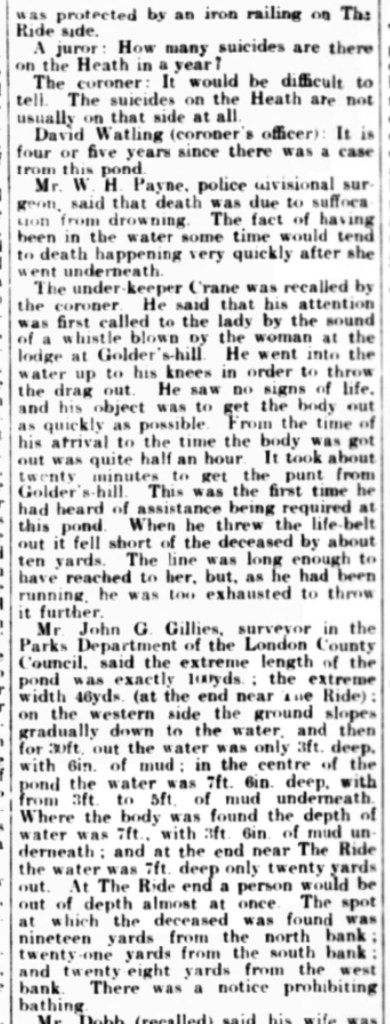

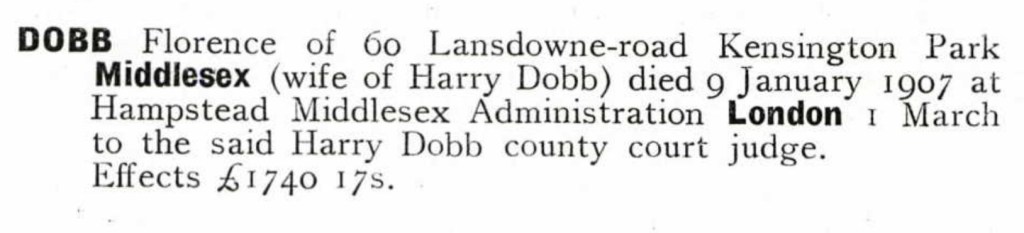

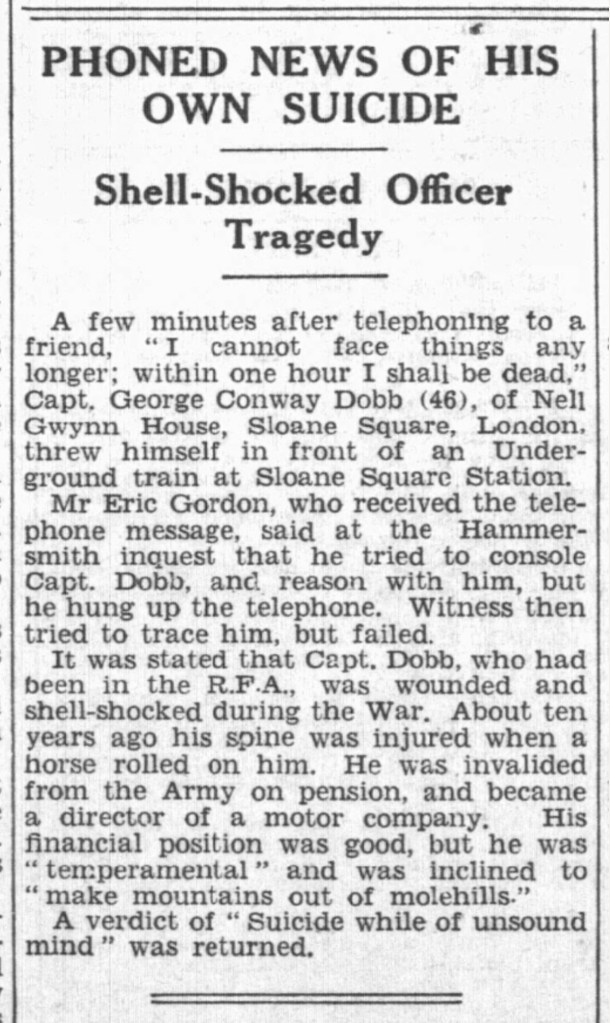

The year 1890 began as a celebration of love and new beginnings for the Willats family. On a crisp Wednesday, February 5th, James’s daughter, Florence Willats, just 19 years old and filled with the promise of her future, exchanged vows with 22-year-old Harry Dobbs, a bachelor with charm and ambition, at the elegant St. Mark’s Church on Old Marylebone Road in London.

The ceremony was a moment of joy and significance, witnessed by friends May Hydes and Ernest F. Burchatt, whose presence surely added warmth and support on this special day. Florence, radiating youthful grace, gave her family home at 37 Lansdowne Crescent as her address, a place steeped in memories and love. Harry, her groom, listed his address as 29 Abercrombie Place and proudly described his occupation as "Gentleman," a title that spoke to his aspirations and standing.

When asked about their fathers, Florence and Harry honored the men who had shaped their lives. Harry’s father, Henry Dobb, was noted as a Draper, a respectable trade that spoke to hard work and business acumen. Florence’s father, recorded as William James Willats, was listed as a Diamond Merchant, his life spent in the glittering world of jewels. The formality of the occasion and these details offered a glimpse into the lives and legacies they carried with them into this new chapter.

As Florence and Harry stood before their loved ones and made their vows, the moment must have been filled with a sense of possibility, a blending of two lives, two families, and two futures, all beginning on that February day in the heart of London.

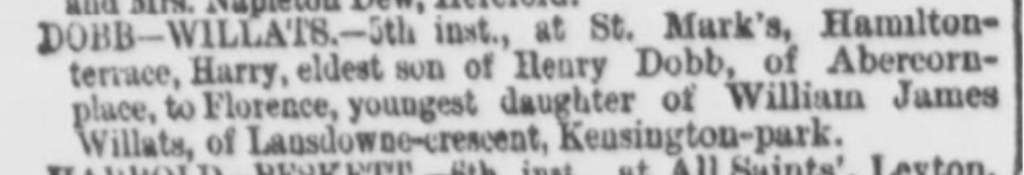

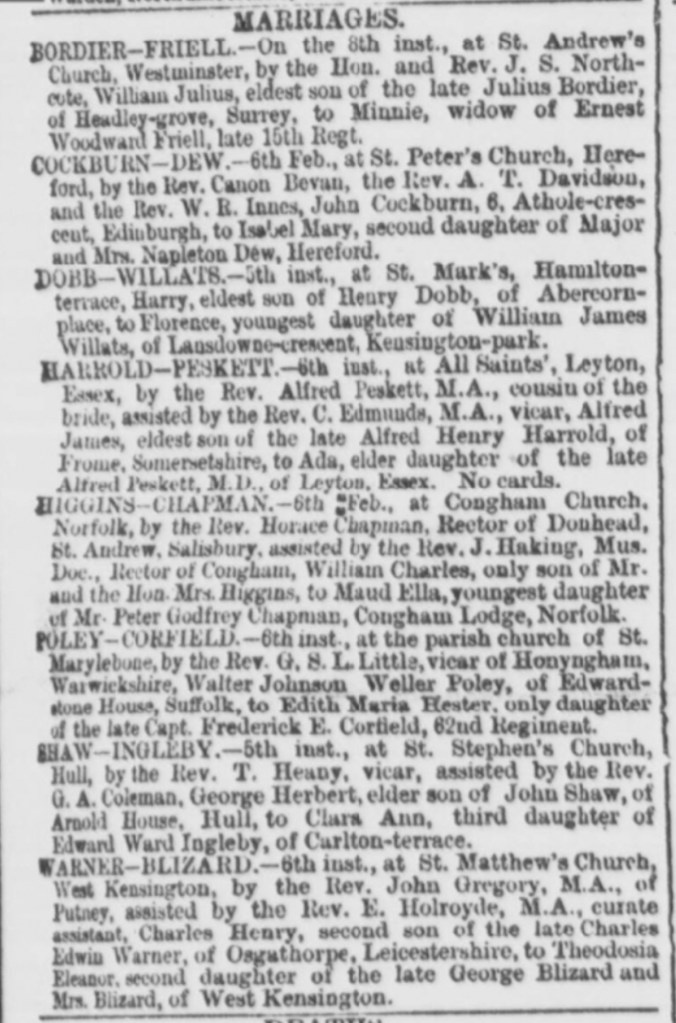

On the 10th of February, 1890, James’s name appeared in the Daily News (London), marking a cherished moment in his family’s life. The newspaper published an announcement of his daughter Florence's marriage, beautifully worded in the paper’s column:

"DOBB-WILLATS. – 5th inst, at St. Mark’s, Hamilton-terrace, Harry, eldest son of Henry Dobb, of Abercrombie-place, to Florence, youngest daughter of William James Willats, of Lansdowne-crescent, Kensington-park."

This brief yet heartfelt notice captured the essence of the joyous occasion that had unfolded just days earlier, as Florence, the youngest of James and Elizabeth’s children, had married Harry Dobbs at St. Mark’s Church. The newspaper’s mention of the families' addresses, James’s at Lansdowne Crescent, Kensington Park, served as a quiet reminder of the home and legacy Florence carried with her into this new chapter with Harry. It was a public acknowledgment of a milestone, a beautiful moment in the lives of the Willats family, now forever preserved in the pages of the London newspaper.

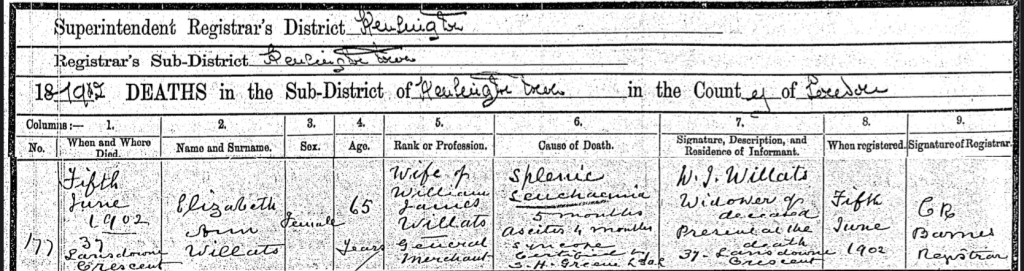

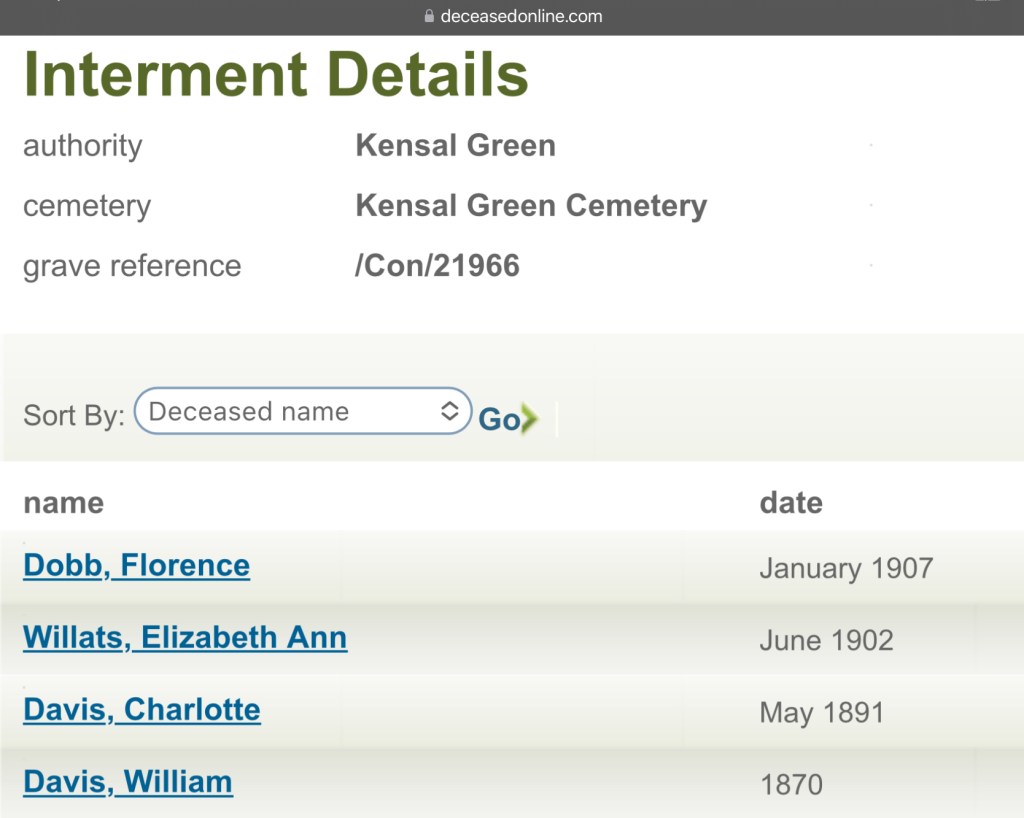

On the 5th of April, 1891, as the census was completed, James and his family were once again counted in the heart of their home at 37 Lansdowne Crescent, Kensington, London. The house, a place filled with the sounds of everyday life, was shared by James, his devoted wife Elizabeth, and their children, William Henry, Clariss C, and Emily B. The warmth of family life radiated through the census as it recorded their peaceful existence in this elegant part of London.

That year, the household was joined by a lodger, Bernard L. Davis, a 62-year-old assistant.

The family’s domestic staff included two young women, 28-year-old Elizabeth Moles and 24-year-old Emma E. Mendham, whose roles would have been vital in maintaining the bustling household.

James, ever adaptable, was now working as a communications agent, a shift from his previous roles in the world of jewels and diamonds. His work in this new field reflected a life of transition, embracing the changes of the time. As with the previous records, James was once again listed as William J. Willats, maintaining the use of his middle name.

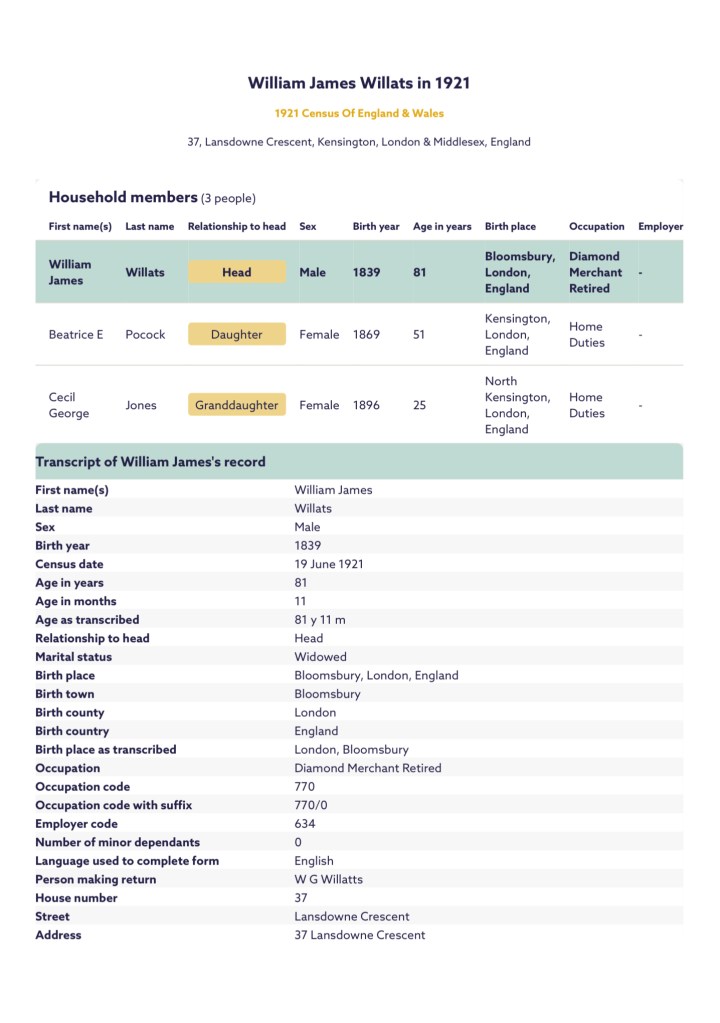

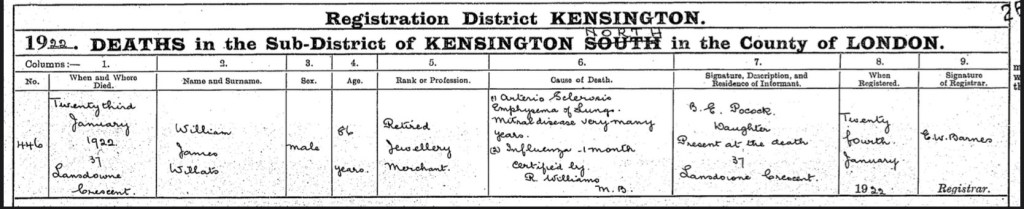

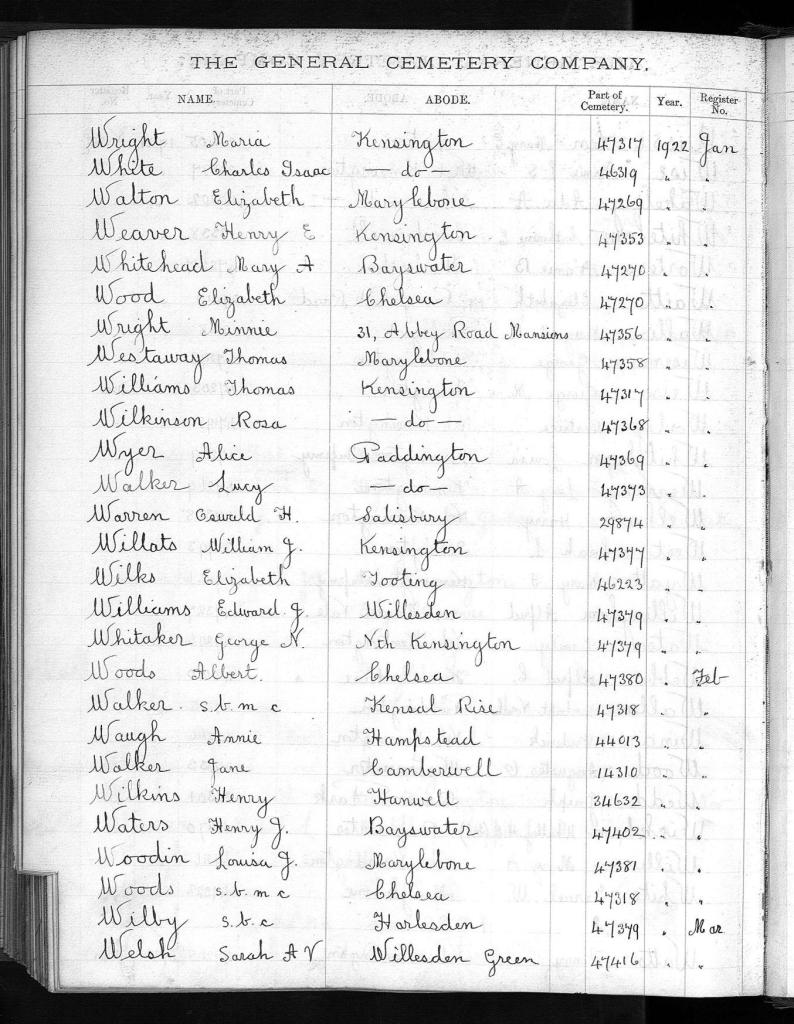

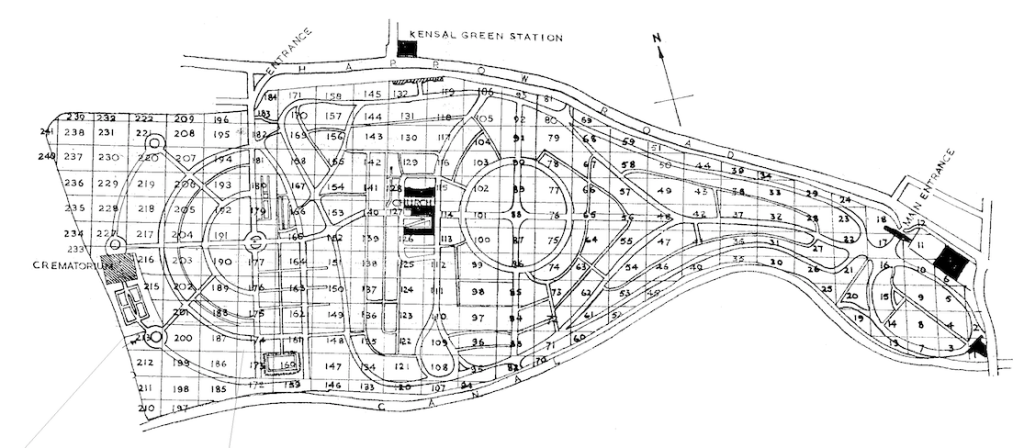

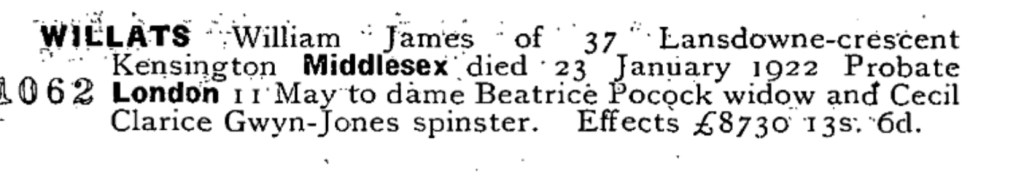

The census captures a moment in time where the Willats family continued to build their lives, now a blend of old and new, in a house filled with the hum of domesticity, companionship, and change.