On the 113th anniversary of the sinking of the Titanic, we remember not just a ship lost to the depths of the North Atlantic, but the thousands of lives taken with her, each one carrying hopes, struggles, and stories that still echo through time. Among those lost was a young fireman from Southampton named Samuel Solomon Williams, a man whose name may not appear in bold in history books, yet whose story speaks volumes of quiet strength, heartbreak, and sacrifice.

It was within the quiet corners of Southampton, Hampshire, England, that Samuel's life unfolded, poignant, and at times, shrouded in mystery. Born in 1884, he embarked on a journey marked by both promise and sorrow, a journey now forever etched in the annals of time. As we delve into “The Life of Samuel Solomon Williams, 1884–1912, Through Documentation,”we are drawn into a narrative that transcends dates and places, revealing a soul whose existence resonates with both triumph and tragedy.

Beyond the veil of history lies a tale that has sparked speculation and stirred whispers, perhaps even shame for those left behind. Yet amid those shadows, Samuel’s life emerges as a quiet testament to resilience, to love, and to the enduring power of memory. Join us as we gently unravel the enigma of Samuel Solomon Williams, a son, a dreamer, a man, whose story continues to stir hearts and minds, reminding us of the fragility and strength woven into the fabric of every human life.

So without further ado I give you the tragic life story of Samuel Solomon Williams.

The Life Of

Samuel Solomon Williams

1884–1912

Welcome back to the year 1884, Southampton, Hampshire, England. The town, already a bustling port, is alive with the sounds of industry, the cries of dock workers, and the steady movement of ships coming and going along the coast. Britain is still under the rule of Queen Victoria, who has now been on the throne for nearly fifty years. The country is led by Prime Minister William Ewart Gladstone, representing the Liberal Party, and Parliament is in the midst of great political discussions, including the expansion of voting rights and the future of the British Empire.

Southampton, a significant hub for maritime trade, is growing rapidly. The docks are expanding, and the town is benefiting from the increasing reliance on steam-powered ships, which have begun to overtake sailing vessels. The railway network is well established, allowing goods and passengers to move with greater ease than ever before. Steam trains run daily, connecting Southampton to London and other parts of the country. Horse-drawn carriages remain the primary mode of transport within the town, clattering over cobbled streets, and bicycles, though not yet widespread, are beginning to appear among the wealthier classes.

Lighting and energy in 1884 are in a period of transition. Gas lighting is common in the streets and in wealthier homes, but many working-class households still rely on oil lamps or candles. Electricity, though experimented with, is not yet a standard feature in homes or businesses, and coal remains the dominant source of energy for industry and heating. Houses of the well-to-do have fireplaces in nearly every room, keeping the chill at bay, while the poor rely on small stoves or whatever warmth they can get in overcrowded dwellings.

Sanitation is still a significant issue. While improvements have been made in the wake of the cholera outbreaks of previous decades, many working-class areas still suffer from inadequate drainage and waste disposal. Indoor plumbing is a luxury afforded only to the upper and middle classes, with the poor often relying on communal privies and shared water pumps. Disease remains a constant threat, and infant mortality rates are high, especially in densely populated urban areas.

Fashion in 1884 reflects the rigid social structures of the time. Women of means wear elaborate, tightly corseted dresses with high collars and bustled skirts, often made of heavy fabrics like velvet and silk. Gloves and bonnets are essential accessories, and mourning attire remains a strong tradition, influenced by the long period of Queen Victoria’s own mourning for Prince Albert. Working-class women wear simpler, more practical garments, often made from wool or cotton, with aprons covering their dresses as they labor in factories, kitchens, or as domestic servants. Men of the upper classes wear tailored suits with waistcoats, top hats, and cravats, while laborers wear more utilitarian clothing, such as wool trousers, rough jackets, and caps.

Food varies greatly depending on social class. The wealthy enjoy an abundance of fresh meats, fish, cheeses, fruits, and elaborate puddings, served in multi-course meals prepared by household staff. Tea is an essential part of daily life, particularly for the middle and upper classes, accompanied by cakes and biscuits in the afternoons. The working class, on the other hand, often subsist on bread, porridge, potatoes, and whatever cheap cuts of meat or fish they can afford. Markets and street vendors sell pies, oysters, and hot eels to laborers looking for a quick and affordable meal.

Entertainment in 1884 ranges from grand affairs to more humble pastimes. The upper classes frequent the theatre, attend operas, and enjoy lavish balls in stately homes. The middle classes have growing access to music halls, public lectures, and novels, thanks to the increasing literacy rate and the spread of affordable books and newspapers. The working class finds its enjoyment in public houses, street performances, and occasional visits to fairs and circuses. The influence of the music hall is on the rise, offering lively performances that blend comedy, song, and dance for an eager audience.

The atmosphere of Southampton in 1884 is one of industry and expansion. The town is growing, with new housing developments appearing to accommodate the influx of workers drawn to the docks and railways. The air is thick with coal smoke from factories and steam engines, and the streets are crowded with people going about their daily lives. The class divide remains stark. The wealthy live in well-appointed homes with servants to tend to their needs, while the working class struggles to make ends meet in crowded tenements. The poorest, unable to afford even these accommodations, find themselves in workhouses or surviving on the streets.

Politically, Britain is in the midst of important changes. The Third Reform Act, which will extend voting rights to more men, particularly in rural areas, is under discussion. There is a growing awareness of the plight of the working class, with debates on social reform and labor rights beginning to gain traction. Meanwhile, the British Empire continues to expand, bringing both wealth and controversy, as colonial rule is increasingly questioned by some political voices.

Gossip and news of the day fill the newspapers and drawing rooms. Scandals involving the aristocracy captivate the public, while international events, such as tensions in Egypt and the Sudan, make their way into discussions among the politically inclined. Scientific advancements are also a topic of fascination, with new discoveries and inventions promising to shape the future.

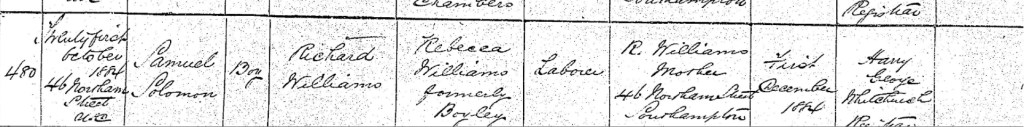

On an autumn day, Tuesday the 31st day of October 1884, in the bustling town of Southampton, Hampshire, England, a new life began. At Number 46, Northam Street, the Williams family welcomed their newest member, Samuel Solomon Williams. His mother, Rebecca Williams, née Boyley, had endured the pains of childbirth within the walls of their modest home, cradled by the love of her husband, Richard John Williams, a hardworking labourer. Their house, already full of laughter and the chaos of growing children, became home to yet another son, a boy whose life would unfold with both promise and sorrow.

Samuel was the fifth child in a family shaped by love and resilience. His parents had built their lives together, having married on Sunday the 2nd of February 1873 at Saint Mary’s Church in Southampton. Their union had already brought them a bustling household, Richard John Williams (1873–1931), Charles William Williams (1875–1947), Rebecca Elizabeth Williams (1877–1952), Emma Jane Williams (1879–1947), Albert Henry Williams (1880–1961), and Edward Williams (1883–1936). Each sibling had their own place within the family, and now Samuel, fragile and new, was nestled among them, another thread in the ever-growing fabric of the Williams lineage.

Rebecca, as any devoted mother, made the journey into Southampton to register his birth on Wednesday the 1st day of October 1884. In a quiet office, surrounded by stacks of ledgers documenting the lives of countless others, she stood before Registrar Harry Charles Whitchurch. He carefully inscribed in the official records: Samuel Solomon Williams, a son, born to Richard Williams, a labourer, and Rebecca Williams, formerly Boyley, of Number 46, Northam Street, Southampton, in the upper district of the town. A name now forever imprinted in history, though no one could yet foresee the turns his life would take.

Samuel’s arrival was much like any other, an infant born into a working-class family, surrounded by the familiar sights and sounds of Southampton. But as the years would unfold, his story would take a path neither he nor his family could have predicted. His life, though brief, would leave behind questions, speculation, and whispers that still linger long after his passing.

The surname Williams is of patronymic origin, meaning it is derived from the given name of an ancestor. It comes from the name William, which itself has Germanic roots, stemming from the Old High German "Willehelm," a combination of "wil" (meaning "will" or "desire") and "helm" (meaning "helmet" or "protection"). This name was introduced to England by the Normans after the conquest of 1066 and became one of the most popular given names, leading to the development of Williams as a hereditary surname.

The Williams surname is particularly common in Wales, where it became widely used in the 16th century due to the Welsh tradition of patronymic naming. Before hereditary surnames became fixed, Welsh naming conventions would use "ap" (meaning "son of") before the father’s name, so a person named William’s son might be called "ap William." Over time, this evolved into the surname Williams. The name is also prevalent in England, particularly in the west and southwest, as well as in parts of Ireland and Scotland.

The family crest associated with the Williams surname varies depending on different lineages and regions. However, a common representation features a shield divided into quarters or adorned with heraldic symbols such as a lion, a chevron, or fleur-de-lis, reflecting noble associations and military service. Some versions of the Williams coat of arms include a red lion rampant on a silver background, symbolizing strength and bravery, while others incorporate elements such as black chevrons on gold, signifying protection and steadfastness. The family motto often associated with the Williams name is "Crescit sub pondere virtus," which translates to "Virtue grows under oppression," reflecting resilience and strength.

As the surname spread through migration and expansion, Williams became one of the most common surnames in English-speaking countries, particularly in the United States, Canada, and Australia. Many notable individuals have carried the name, including historical figures, politicians, authors, and athletes. Today, Williams remains one of the most widespread surnames, particularly in Wales and the United States, continuing its legacy as a name of strength and heritage.

The name Samuel has ancient origins and a rich history that spans centuries and cultures. It is of Hebrew origin, derived from the name **Shmuel**, which means "God has heard" or "name of God." The name is deeply rooted in biblical tradition, most notably associated with the prophet Samuel in the Old Testament. According to biblical accounts, Samuel was a significant figure who served as the last of Israel's judges, a prophet, and the one who anointed both Saul and David as kings of Israel. His story is one of divine calling, faith, and leadership, making the name Samuel carry connotations of wisdom, devotion, and guidance.

The name Samuel became widespread throughout Christian and Jewish communities, particularly in medieval Europe, where biblical names were commonly given to children. It gained particular prominence in England following the Norman Conquest of 1066, when biblical names became more popular in Britain. By the 17th and 18th centuries, Samuel was a well-established given name across English-speaking countries, often associated with religious or scholarly families. Many Puritans favored the name due to its biblical significance, and it was commonly found among early settlers in America.

Throughout history, numerous notable figures have borne the name Samuel. Among them are **Samuel Johnson**, the great English writer and lexicographer of the 18th century; **Samuel Pepys**, the famous diarist whose detailed accounts of 17th-century London provide invaluable historical insights; and **Samuel Morse**, the inventor of the Morse code. In politics, **Samuel Adams** was a key figure in the American Revolution, and in literature, **Samuel Beckett** made his mark as a Nobel Prize-winning playwright.

The name has maintained its popularity over the centuries and remains widely used in many cultures today. It is a classic and timeless name, suitable for both formal and familiar settings, often shortened to affectionate forms such as Sam or Sammy. The enduring appeal of Samuel lies in its deep historical and religious roots, as well as its association with wisdom and leadership.

In terms of heraldry, names like Samuel often do not have a single, fixed coat of arms, as coats of arms were traditionally granted to families rather than given names. However, various families with the surname Samuel have had their own crests, often featuring religious symbols, books (representing knowledge), or lions (signifying strength and bravery). The heraldic tradition linked to the name Samuel reflects the noble and scholarly associations the name has carried throughout history.

Today, Samuel remains a widely used and respected name across different cultures and languages. Whether in its traditional form or its shortened variations, it continues to be a name associated with intelligence, faith, and historical significance.

The name Solomon is one of great antiquity, deeply rooted in biblical and historical tradition. It originates from the Hebrew name **Shlomo (שְׁלֹמֹה)**, which is derived from the Hebrew word **shalom**, meaning "peace." This gives the name a strong connotation of wisdom, prosperity, and harmony. Its most famous bearer is **King Solomon**, the legendary ruler of ancient Israel, son of King David, and one of the most revered figures in the Bible. He is renowned for his wisdom, his role in building the First Temple in Jerusalem, and his authorship of several biblical texts, including Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, and the Song of Solomon.

In Jewish, Christian, and Islamic traditions, Solomon is seen as a ruler of great intellect and fairness, often depicted as the epitome of wisdom. The biblical stories of Solomon, such as the tale of the two women claiming to be the mother of the same child—where he proposed cutting the baby in half to determine the real mother—have cemented his status as a figure of legendary discernment and justice.

The name Solomon spread throughout Europe during the medieval period, particularly among Jewish communities, where it was a highly respected name given its biblical prominence. It was also used in Christian societies, especially among scholars and religious figures. During the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, it was sometimes adopted by individuals who admired the wisdom and learned reputation of its biblical namesake.

In English-speaking countries, Solomon became more common after the Protestant Reformation, a period when biblical names gained popularity. By the 18th and 19th centuries, it was well-established, though often more frequent in Jewish communities. Over time, it also became a surname, carried by many families of Jewish or Christian descent.

Historically, many prominent individuals have borne the name Solomon. One of the most famous is **Solomon Northup**, the African-American man whose memoir *Twelve Years a Slave* (1853) provided a powerful firsthand account of slavery in the United States. Other notable Solomons include scholars, artists, and political figures who have carried on the name’s legacy of intellect and leadership.

Heraldry associated with the name Solomon varies by family rather than by the name itself. Many coats of arms linked to the name contain symbols of wisdom, such as books, owls, or scales of justice, reflecting the qualities of judgment and knowledge associated with the biblical Solomon. Some variations also feature elements that signify strength and leadership, such as lions or crowns, in reference to his royal status.

Today, Solomon remains a respected and meaningful name, often chosen for its strong historical and religious significance. It is still commonly used in Jewish, Christian, and Muslim communities, and it carries with it a legacy of peace, wisdom, and prosperity. Whether in its full form or in diminutives such as Sol or Solly, it continues to be a name that conveys both intellectual depth and spiritual significance.

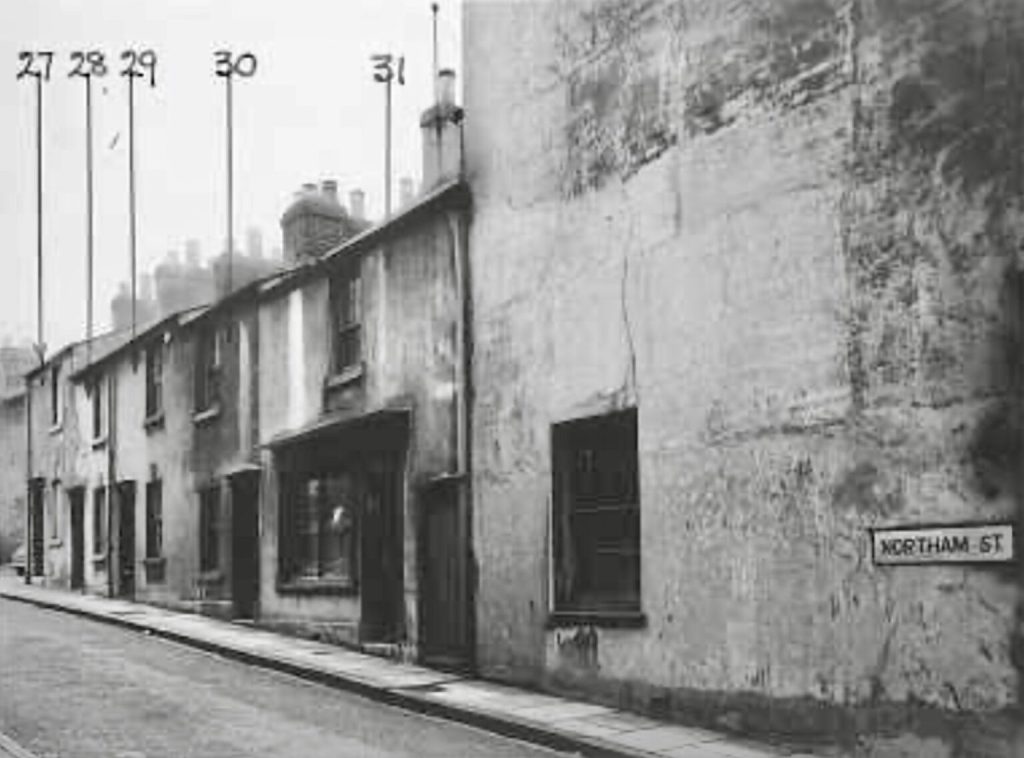

Northam Street, located in the Northam district of Southampton, Hampshire, has a history deeply intertwined with the city's industrial and maritime development. The Northam area has been a significant part of Southampton since at least the 13th century, with records of the Chapel of St. Mary de Graces dating back to 1225. Over the centuries, Northam evolved into a hub for shipbuilding and industry, particularly during the 19th century. The establishment of the Northam Iron Works in 1839 marked a pivotal moment, as the area became known for constructing iron steamers and tugs, contributing substantially to Southampton's maritime prominence.

In the early 20th century, Northam Street was a residential area characterized by terraced housing that accommodated workers from the nearby industries. Photographs from the 1920s depict residents and children in Northam Street, illustrating a close-knit community amidst the industrial backdrop.

However, as industrial activities declined and urban development progressed, Northam Street, along with other parts of Northam, underwent significant changes. The mid-20th century saw slum clearance initiatives aimed at improving living conditions, leading to the demolition of many original structures. These efforts were part of broader urban renewal projects that reshaped the landscape of Southampton.

Today, Northam Street reflects a blend of its historical roots and modern developments. While much of the original architecture has been replaced or repurposed, the area's rich history remains evident in its proximity to landmarks like the Northam Bridge and the remnants of industrial sites that once defined the community. The transformation of Northam Street mirrors the broader evolution of Southampton from an industrial powerhouse to a modern urban center.

As the winter chill lingered in the air, Richard and Rebecca Williams carried their infant son, Samuel Solomon Williams, to Saint Matthew’s Church in Southampton. It was Sunday, the 4th day of January, 1885, a joyous occasion as they stood before the font, presenting their child to be baptised. The flickering candlelight and the soft murmur of prayers filled the sacred space as the priest anointed Samuel, marking the beginning of his spiritual journey.

For Richard and Rebecca, this was more than just a tradition, it was a moment of devotion, a declaration of their hopes for their son’s future. As the holy water touched his skin, Samuel’s name was spoken aloud, echoing through the church, another soul welcomed into the faith, another name entered into the church’s register. In that moment, surrounded by family and faith, his place in the world felt secure.

Little did they know that Samuel’s path would be far from ordinary. Though his life had only just begun, the years ahead would be shaped by both light and shadow, love and loss. And as history would show, his story would not be easily forgotten.

St. Matthew's Church, located at the intersection known as Six Dials in Southampton, Hampshire, has a rich history that reflects the city's evolving community and architectural heritage. Constructed between 1869 and 1870, the church was designed by architects Hinves and Bedborough in a distinctive neo-Norman style, a design choice that architectural historian Nikolaus Pevsner described as "queer neo-Norman." The establishment of St. Matthew's was part of a broader effort to accommodate the spiritual needs of Southampton's growing population during the mid-19th century. The parish was officially formed in 1866, and the church was built shortly thereafter, providing seating for approximately 730 congregants. In 1874, the church underwent enlargement to better serve its community.

As the decades passed, the role of St. Matthew's Church within the community began to change. With declining attendance in the late 20th century, the church ceased its original function and, by the late 1970s, was repurposed as The West Indian Club, serving as a cultural and social hub for Southampton's Afro-Caribbean community.

In 2006, Southampton Lighthouse International Church acquired and renovated the adjacent St. Matthew's Hall, marking the beginning of a new chapter for the site. By 2017, they expanded their vision to include the former St. Matthew's Church building itself, aiming to restore it as a place of Christian worship and community gathering. The restoration project was ambitious, with estimated costs ranging between £500,000 and £800,000, reflecting the church's commitment to revitalizing this historic structure.

Throughout its history, St. Matthew's Church has stood as a testament to Southampton's dynamic cultural and social landscape, adapting to the needs of its diverse community while retaining its architectural significance.

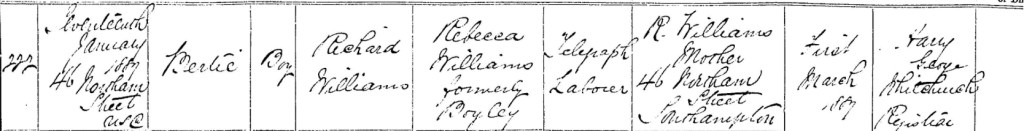

As Samuel Solomon Williams grew from infancy, his world was about to change once more. On Monday, the 17th day of January 1887, the Williams family welcomed another child into their home at Number 46, Northam Street, Southampton. A newborn baby boy, Bertie Williams, made his arrival into an already bustling household, joining his older siblings in the warmth and chaos of family life.

Rebecca, now a mother of eight, once again took it upon herself to fulfill the necessary duties that came with bringing a new life into the world. Braving the winter chill, she made her way into Southampton on Tuesday, the 1st day of March 1887, to officially register her son’s birth. In the familiar setting of the registrar’s office, she once more stood before Harry Charles Whitchurch, who carefully inscribed Bertie’s name into the official birth register. The record stated that Bertie, a boy, was the son of Richard Williams, a labourer, and Rebecca Williams, formerly Boyley, of Number 46, Northam Street, in the upper district of Southampton.

Samuel, now two years old, was no longer the youngest in the family. His world, once centered around the arms of his mother and the familiar faces of his older siblings, now expanded to include baby Bertie. The Williams home, already filled with the laughter and footsteps of growing children, grew even livelier. In the years to come, Samuel and Bertie would navigate childhood together, two brothers bound by family, faith, and the unseen forces of fate that would one day shape their destinies.

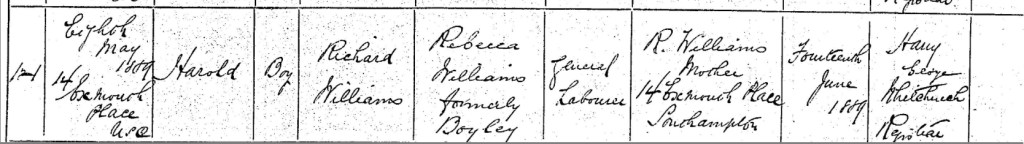

As the Williams family continued to grow, life carried on in the working-class streets of Southampton. By 1889, they had moved from their home on Northam Street to a new residence at Number 8, Exmouth Place. It was there, on Wednesday, the 8th day of May, that Rebecca Williams once again endured the familiar pain of childbirth, bringing her youngest son, Harold Williams, into the world.

With each new child, Rebecca’s role as a mother deepened. She had spent the last sixteen years raising her growing family, tending to the needs of her children while supporting her husband, Richard, who worked tirelessly as a general labourer. Their days were filled with routine, hard work, laughter, and the occasional hardships that came with raising a large family in Victorian England.

On Friday, the 14th day of June, 1889, Rebecca set out once more to register the birth of her son. She made her way into Southampton, a journey she had taken before, stepping into the registrar’s office to provide the details of her newborn. As before, Harry Charles Whitchurch carefully recorded the information in the birth register: Harold Williams, a boy, son of Richard Williams, a general labourer, and Rebecca Williams, formerly Boyley, of Number 8, Exmouth Place. Another name added to the family record, another child welcomed into the world.

Samuel, now four years old, had seen many changes in his short life. He had watched his family expand, had likely peered curiously over the crib of his new baby brother, unaware of the way time would shape their futures. For now, they were simply children, growing up together in the heart of Southampton, bound by the love of their parents and the unbreakable ties of family.

Exmouth Place, situated in Southampton, Hampshire, has a history that reflects the city's evolution over the centuries. Located near New Road, this area has undergone significant transformations, mirroring broader urban developments within Southampton.

Historically, Exmouth Place was part of a vibrant neighborhood characterized by residential and commercial establishments. One notable landmark was the original Bay Tree Inn, positioned on the corner of New Road and Exmouth Street. This establishment served as a social hub for the local community, offering a gathering place for residents and visitors alike.

The area surrounding Exmouth Place experienced considerable changes during and after World War II. Southampton, being a significant port city, was subjected to extensive bombing raids, leading to substantial damage to properties. Photographs and records from the era document the war-damaged properties, providing insight into the challenges faced by the community during this tumultuous period.

In the post-war years, efforts to address the housing shortage led to the introduction of prefabricated homes, commonly known as "prefabs," in various parts of Southampton. While specific records of prefabs on Exmouth Place are not detailed, the broader area saw the implementation of these structures to provide quick and efficient housing solutions for those affected by the war's destruction.

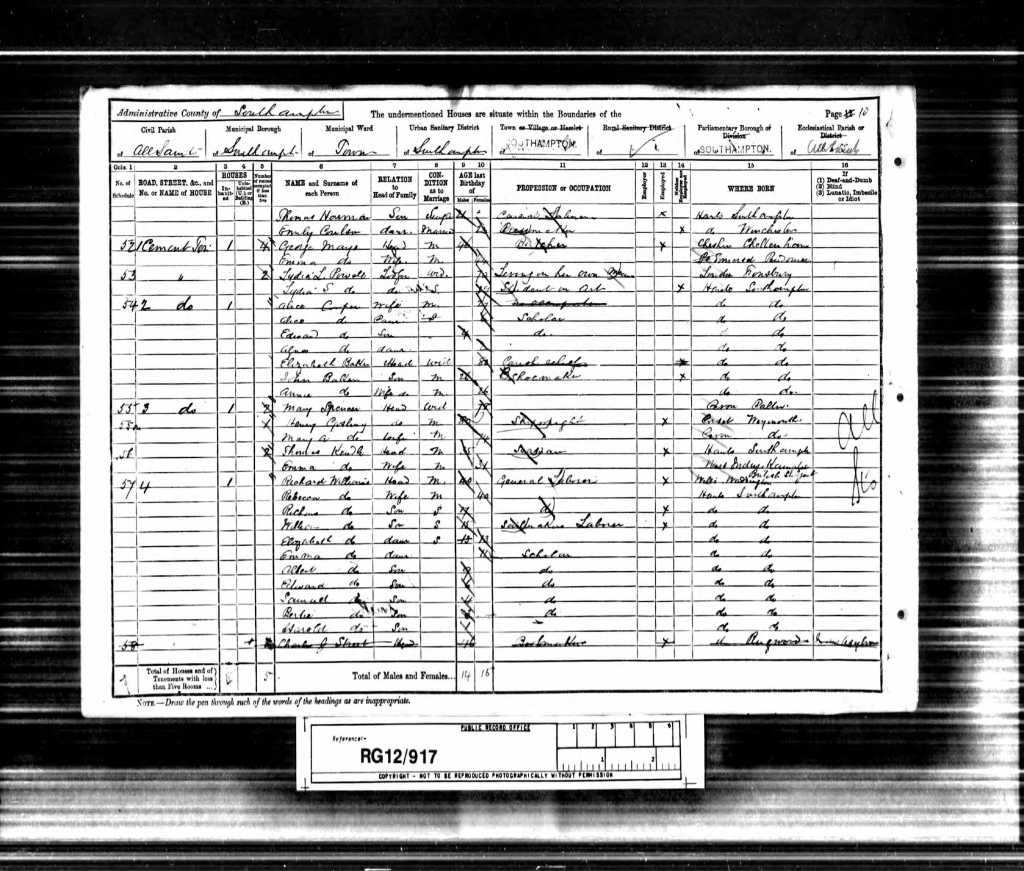

By the eve of the 1891 Census, on Sunday, the 5th day of April, Samuel and his family had once again moved, settling into their new home at Number 4, Cement Terrace, in the All Saints district of Southampton. Their ever-growing household now bustled with the presence of Samuel’s parents, Richard and Rebecca, along with his siblings, Richard, Edward, Elizabeth, William, Albert, Harold, Emma, and Bertie. Nine children under one roof, each with their own place in the family, each carving out a childhood within the walls of their modest home.

Life in Cement Terrace would have been filled with the sounds of everyday family life, the chatter of children, the clatter of dishes, the shuffle of boots as Richard Williams returned from a long day’s work. His occupation, recorded in the census, was that of a General Labourer. It was a broad term, one that spoke to the nature of working-class life in Victorian England. It meant long hours, physically demanding tasks, and an unyielding determination to provide for his wife and children.

For Samuel, now six years old, home was wherever his family was. His days would have been spent navigating the lively, often chaotic world of his siblings, playing in the narrow streets, and learning the ways of the world in the working-class neighborhoods of Southampton. He was still a boy, unaware of the hardships adulthood would one day bring. But for now, he had the security of home, the love of his parents, and the companionship of his brothers and sisters as they all grew together in a city that was constantly changing around them.

Cement Terrace, located in the All Saints area of Southampton, Hampshire, England, was a residential row that existed during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Situated within the parish of All Saints, this terrace was part of a neighborhood characterized by modest housing, accommodating the town's growing population during a period of industrial expansion.

The area was served by All Saints' Church, a significant landmark on the corner of the High Street and East Street. Originally known as All Hallows, the medieval church was rebuilt between 1792 and 1795 and renamed All Saints. This neoclassical building featured an impressive arched ceiling spanning the entire sanctuary without supporting pillars. Notably, the church was attended by author Jane Austen during her residence in Southampton and was the baptismal site of painter Sir John Everett Millais. Unfortunately, All Saints' Church was heavily damaged during the Southampton Blitz in World War II and was subsequently demolished.

Census records from the 1880s provide glimpses into the lives of Cement Terrace residents. For instance, the 1881 census lists Leonard Baptista Alfred Smith, a three-year-old scholar, residing with his grandfather George Baciochi at 2 Cement Terrace. These records reflect the family oriented nature of the community, where multiple generations often lived under one roof.

Today, Cement Terrace no longer exists, having been lost to redevelopment and the passage of time. The All Saints area has undergone significant changes, with modern structures replacing many of the historical buildings. Nonetheless, the legacy of places like Cement Terrace endures in historical records and the collective memory of Southampton's rich and evolving history.

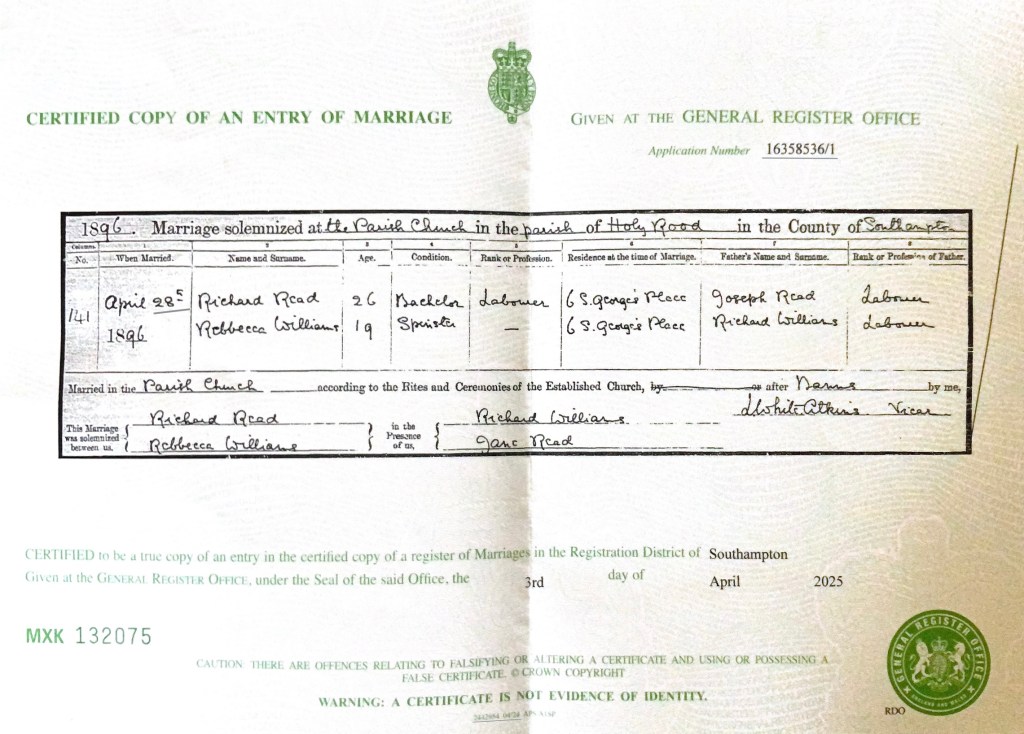

On Tuesday, the 28th of April, 1896, within the quiet walls of Holy Rood Church in Southampton, Samuel's sister, 19-year-old Rebecca Elizabeth Williams stood beside 26-year-old Richard Read, as they pledged their vows before family and faith. Both resided at Number 6, St George’s Place, Rebecca, a spinster, and Richard, a bachelor and labourer. The ceremony was conducted by L. White Atkins, who carefully recorded their union in the marriage register. Rebecca was the daughter of Richard Williams, a hardworking labourer, and her new husband, Richard Read, was the son of Joseph Read, also a labourer by trade. Standing beside them as witnesses to their vows were Rebecca’s father or possibly her brother, also named Richard Williams, and Richard’s mother, Jane Read, née Hutchins, a small gathering to mark the beginning of what they hoped would be a shared life, grounded in love and quiet perseverance.

Holyrood Church, located on Southampton's High Street, has a storied history dating back to its original construction in the 12th century. Initially situated further into the High Street, the church was dismantled and relocated to its present site in 1320. Over the centuries, it became known as the "Church of the Sailors," serving as a place of worship for seafarers and playing a significant role in the maritime community.

The church underwent significant restoration between 1849 and 1850, enhancing its structure while preserving its historical essence. However, during World War II, on the night of November 30, 1940, Holyrood Church suffered devastating damage from German bombing raids, leaving it largely in ruins.

In 1957, the remains of the church were dedicated as a memorial to the men of the Merchant Navy who lost their lives at sea. The site now features several commemorative elements, including a memorial fountain originally erected in 1912–13 for those who perished in the sinking of the RMS Titanic. Additionally, there are audioposts installed in 2007 that provide historical recordings, offering visitors insights into the church's past and its significance to the local community.

As of February 2025, the church underwent repairs to address structural concerns, ensuring the preservation of this historic monument. Today, Holyrood Church stands as a poignant reminder of Southampton's rich history and resilience, serving both as a memorial and a site for annual events such as the Merchant Navy Day memorial service.

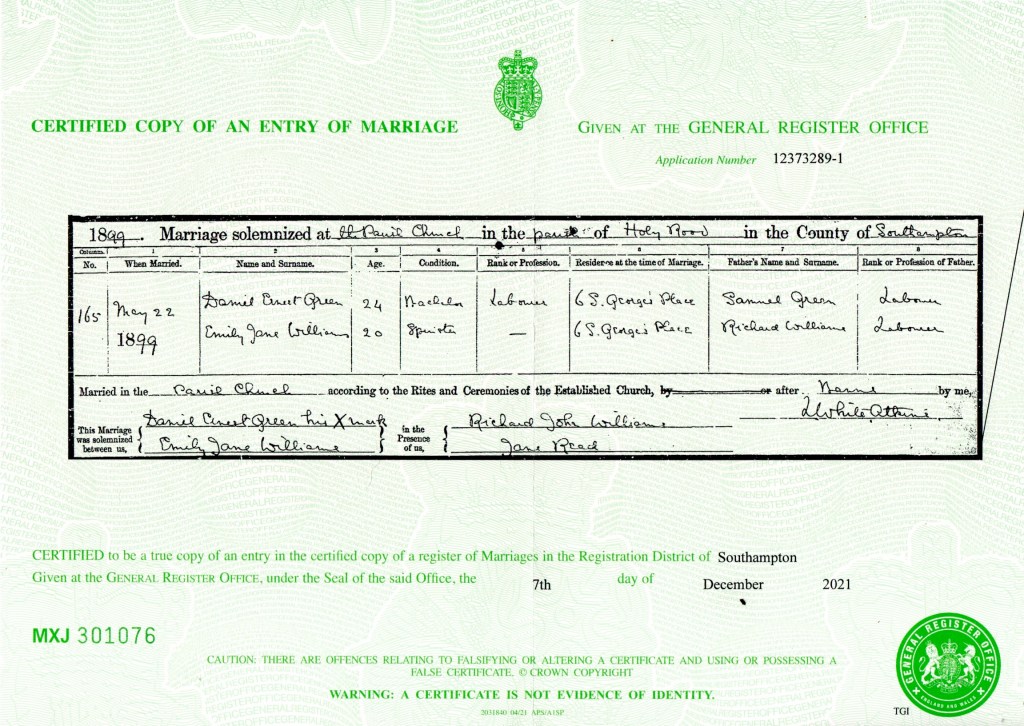

On a spring day, Monday the 22nd day of May, 1899, Samuel’s sister, 20-year-old Emma Jane Williams, took a significant step into her own future. At The Parish Church of Holy Rood in Southampton, she married Daniel Ernest Green, a 24-year-old laborer, marking the beginning of a new chapter in both their lives. The ceremony, held amidst the quiet beauty of the church, was filled with the support and love of family, as Emma and Daniel pledged their lives to one another.

At the time of their marriage, the young couple made their home at Number 65, George’s Place, a modest dwelling where they likely began to dream of their shared future. The details of their marriage reveal a deeper connection to their roots. Daniel, in his registration, recorded his father’s name as Samuel Green, also a laborer, while Emma’s father, Richard Williams, was listed in the same way, a reflection of the hardworking lives both families led.

The ceremony was witnessed by two important figures: Richard John Williams, possibly either Emma’s father or brother, and Jane Read, Rebecca Elizabeth’s sister-in-law, who, alongside the couple, symbolised the unbreakable bond of family and friendship. These witnesses, present in their simplest yet most meaningful way, stood alongside the couple as they exchanged vows.

In a tender, poignant detail, Daniel signed the marriage register with an "X" a mark that, while simple in form, carried the weight of a promise and the solemnity of the vows he had just taken. This mark of his, as he committed himself to Emma, became a part of their story, a quiet symbol of the life they were building together, rooted in love, labor, and the enduring strength of family.

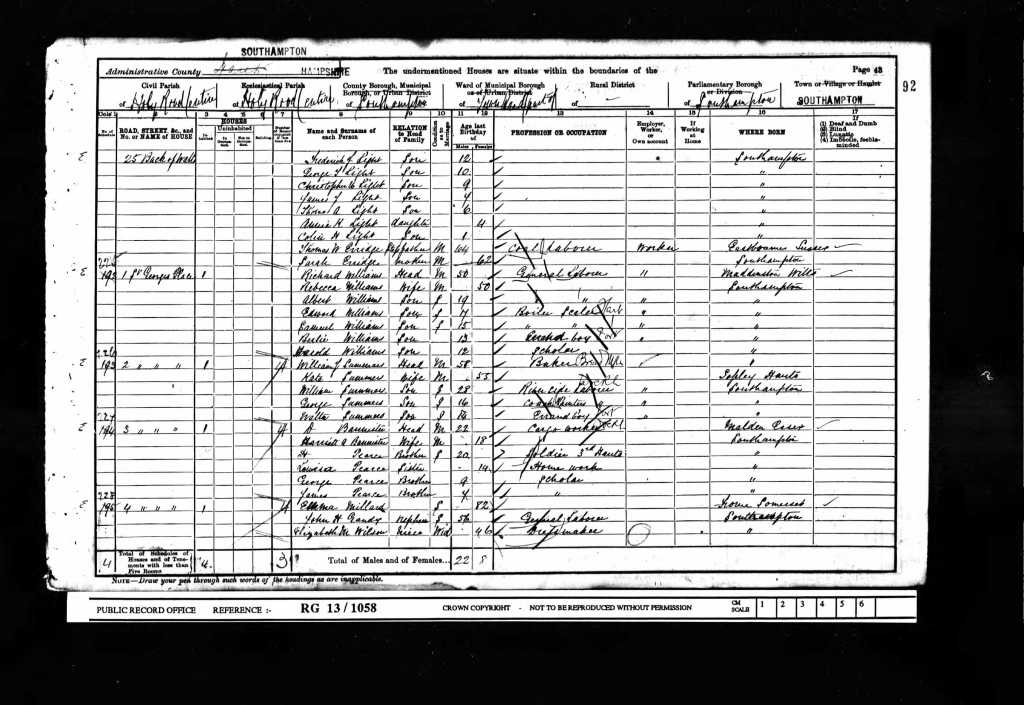

On the eve of the 1901 Census, Sunday, the 31st day of March, Samuel Solomon Williams and his family were living at Number 1, St George’s Place in Southampton, Hampshire. Their home, like so many in the area, would have been modest, yet filled with the bustle and energy of a family of five children, each at different stages of their lives. Samuel was now 16 years old, and his world was becoming more defined as he started to take on the responsibilities of adulthood.

At the time, Samuel’s father, Richard Williams, was still working as a general labourer, just as he had for much of his life. His tireless work was the backbone of the family’s survival. Samuel and his brother Edward, now both young men, were recorded as "boiler sealers" a role that speaks to the industrial nature of the time, likely working with the boilers that powered ships or factories, a physically demanding job that required skill and diligence.

Bertie, Samuel’s younger brother, was listed as an "errands boy," likely running messages and assisting in various small tasks around the neighborhood or for local businesses. Harold, still a child, was recorded as a "scholar," attending school, where he would have begun to learn and prepare for the life that lay ahead of him. The diversity in their occupations paints a picture of a family both shaped by hard work and individual roles, each member contributing to the rhythm of their daily lives.

In this household, there was little room for luxury or idleness. Every member of the family was involved in some way in the survival of their home. Yet even in the midst of such relentless effort, there was a bond of shared experience that tied them together, a sense of solidarity forged through the shared struggles of working-class life in Southampton. It was a life built on resilience and perseverance, as each day they navigated the challenges of living in a city that was constantly evolving.

In 1901, a boiler sealer was a worker tasked with ensuring the proper maintenance and sealing of boilers, which were essential components of steam-powered engines, whether in factories, ships, or locomotives. The job of a boiler sealer involved several key responsibilities, particularly related to the tightness and safety of steam boilers, which operated under high pressure and posed significant hazards if not properly maintained.

The primary task of a boiler sealer was to apply and maintain the seals on the joints and seams of the boiler. Boilers were typically constructed from large metal plates, which were welded or riveted together. The seals ensured that there were no leaks in the boiler, which could lead to dangerous steam escapes or a catastrophic failure. The boiler sealer would use various materials, such as lead-based compounds or asbestos, to seal the joints and prevent steam or water from escaping.

In terms of skills, the boiler sealer would need to be familiar with the construction of steam engines and boilers. The role required physical strength and stamina as it involved heavy, manual labor, often in hot, cramped, and hazardous environments. Sealing the joints on a large boiler might require working in confined spaces or at great heights, especially in shipyards or on board ships. Safety was critical, as improperly sealed boilers could explode, and working around such high-pressure systems was inherently dangerous.

Besides sealing, the job would have also involved checking for rust, wear, and signs of damage on the boiler. The boiler sealer would assist in making minor repairs and ensuring the overall integrity of the boiler. In industrial settings, it was a physically demanding role, with workers often using tools such as hammers, chisels, and specialized sealing compounds.

The job would have been part of the broader trade of boilermaking, a highly skilled area in the shipbuilding and railway industries. Boiler sealers would likely have worked closely with other tradesmen, such as boilermakers and engineers, and would have received on-the-job training. Given the importance of boiler safety in steam-powered industries, this role was crucial for ensuring that boilers functioned properly and safely.

Overall, the job of a boiler sealer in 1901 was labor-intensive, requiring specialized knowledge of steam boilers and the materials used to maintain them, while working in hazardous environments where both skill and precision were key to safety and functionality.

St. George's Place was a 19th-century court located off Back-of-the-Walls in Southampton's Holy Rood area. Dating back to at least 1791, as evidenced by Milne's map, the terrace consisted of buildings likely constructed in the early 19th century. These structures were eventually demolished in the 1930s, making way for new developments in the area.

The Holy Rood parish encompassed a small area of just over 39 acres, covering both sides of the lower High Street and extending to the town quay. The original Holy Rood Church, established around 1160, was situated in the middle of English Street (now High Street). In 1320, the church was relocated to its present site on the eastern side of the road. The church played a central role in the community, serving as a place of worship for crusaders, soldiers, and notable figures such as Philip II of Spain.

Over the centuries, the Holy Rood area underwent significant changes. The original church structure was damaged during the Southampton Blitz in November 1940. The ruins were later preserved and dedicated as a memorial to Merchant Navy seafarers. St. George's Place, as part of this evolving neighborhood, reflects the dynamic history and development of Southampton's Holy Rood district.

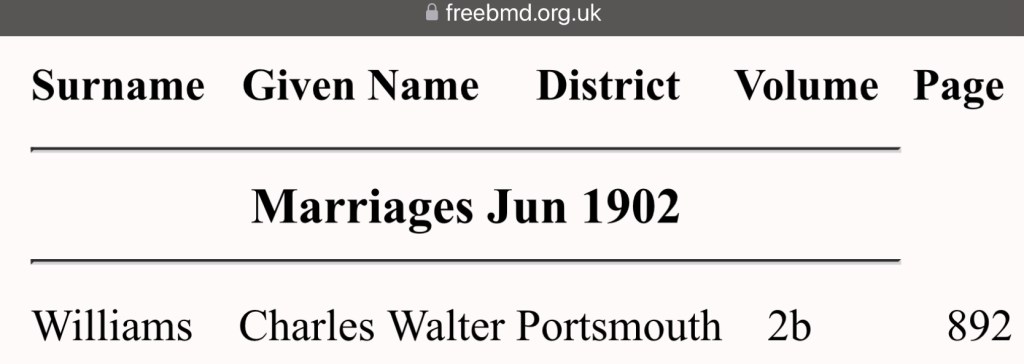

By the spring of 1902, life was continuing to shift and evolve for the Williams family. On Wednesday, the 7th of May, Samuel’s older brother, 27-year-old Charles William Williams, stood at the altar, ready to begin a new chapter of his life. In the district of Portsmouth, Hampshire, he married Ada Hope Cassell, the woman with whom he would build a future. It was a moment of celebration, a step toward stability and companionship, something so many sought in an ever-changing world.

Yet, in an unexpected twist, Charles’ name was recorded as *Charles Walter* in the official marriage indexes. Whether this was a simple clerical error, a preferred name he had chosen for himself, or a miscommunication, it remains a small mystery in the family’s history. Despite this discrepancy, his identity and his place within the Williams family remained unchanged.

For those wishing to obtain further details of their marriage, you can purchase a copy of their marriage certificate with the following information:

“GRO Reference – Marriages, Jun 1902, Williams, Charles Walter, Cassel, Ada Hope, Portsmouth, Volume 2b, Page 892”

With his marriage, Charles followed in the footsteps of his older siblings, leaving behind the household where he had grown up to forge his own path. For Samuel, watching yet another sibling begin a new life may have been a bittersweet moment. His family was growing and changing, but with each departure, the home he had always known became a little quieter. Soon, his own journey would take him beyond the family home, setting him on a path that neither he nor anyone around him could have foreseen.

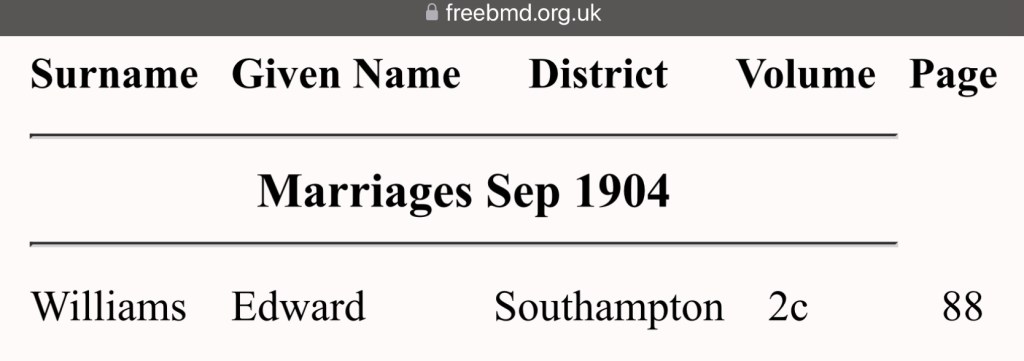

By the late summer of 1904, another chapter in the Williams family's story was unfolding. Samuel’s 21-year-old brother, Edward Williams, stood before family and friends as he married Sarah Ann Pearce in the district of Southampton. Though the exact details of their wedding day remain unknown, one can imagine the anticipation and joy that must have surrounded the couple as they embarked on this new journey together.

Marriage, in working-class families like the Williamses, was not just about love, it was about partnership, about creating a stable home in a world that often demanded resilience. Edward, like his siblings before him, was stepping into a future where responsibility and hard work would define his days, but he would no longer face it alone.

For those who wish to obtain further details of their marriage, the official record is as follows:

“GRO Reference – Marriages Sep 1904, Williams, Edward, Pearce, Sarah Ann, Southampton, Volume 2c, Page 88”

With each passing year, the Williams family was growing and changing. Edward’s marriage marked yet another shift, another sibling leaving the home they had once all shared. Samuel, now in his twenties, was witnessing these transitions firsthand. His brothers and sisters were finding their own paths, shaping their own futures. And soon, his own story would take a turn, one that would lead him toward both promise and tragedy, forever marking the legacy he would leave behind.

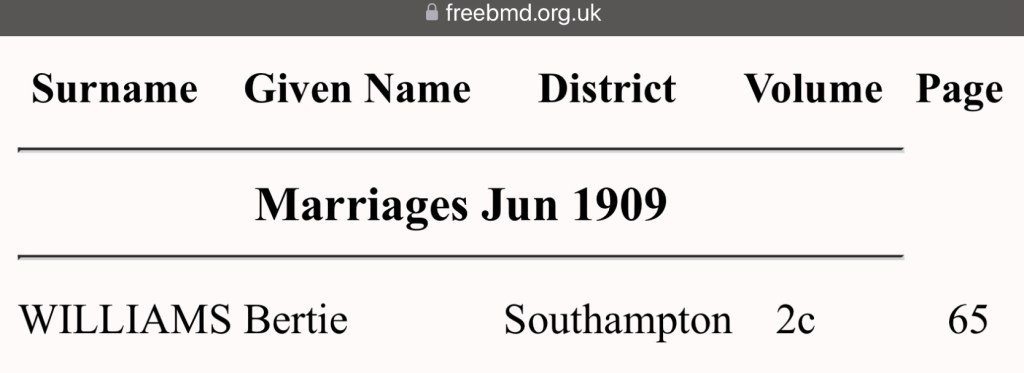

By the spring of 1909, another milestone had been reached within the Williams family. Samuel’s 22-year-old brother, Bertie Williams, married May Beatrice Barton in the district of Southampton. Though the precise details of their wedding day are unknown, it is easy to picture the occasion, a young couple, filled with hope and anticipation, standing before family and friends as they vowed to build a life together.

Marriage was not just a romantic union but a practical step toward the future. For families like the Williamses, it meant stability, a home of one’s own, and the promise of new beginnings. Bertie, like his older siblings before him, was moving forward, forging his own path alongside the woman he had chosen to share his life with.

For those wishing to obtain further details of their marriage, the official record is as follows:

“GRO Reference – Marriages Jun 1909, Williams, Bertie, Barton, May Beatrice, Southampton, Volume 2c, Page 65”

With each wedding, the Williams household grew quieter. One by one, Samuel’s siblings were stepping into their own futures, leaving behind the shared home and childhood memories they had built together. Life was moving forward, ever-changing, as the family spread out across Southampton, carrying their shared past with them. For Samuel, the path ahead remained uncertain, but what was certain was that his own story was still unfolding, with moments yet to come that would shape not only his life but the way he would be remembered.

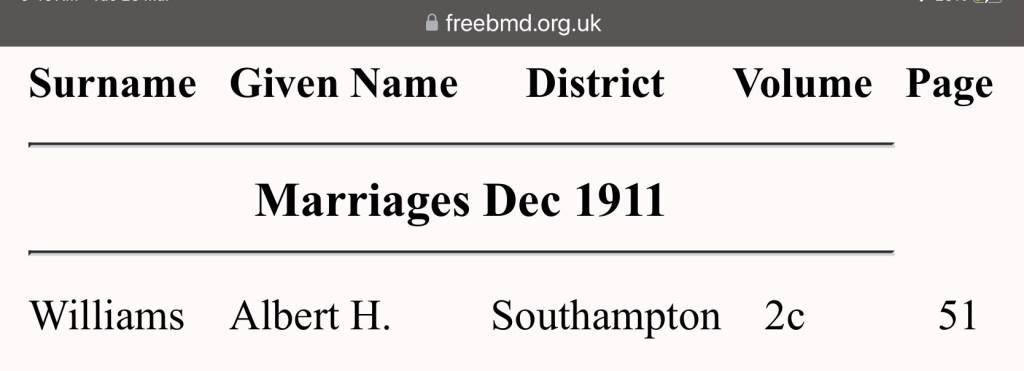

By the autumn of 1911, the Williams family witnessed yet another moment of change as Samuel’s 31-year-old brother, Albert Henry Williams, married Jane Florence Victoria Barton in Southampton, Hampshire. At this stage in his life, Albert had likely spent years working hard, shaping a life of his own, and now, with Jane by his side, he was taking the next step toward a future built on companionship and stability.

Marriage, particularly in the working-class communities of Southampton, was more than just a personal milestone, it was a partnership, a foundation upon which two people could build a home and a family. Albert, now in his early thirties, may have been one of the last of his siblings to wed, but his journey was unfolding in its own time, in its own way.

For those wishing to obtain further details of their marriage, the official record is as follows:

“GRO Reference – Marriages, Dec 1911, Williams, Albert H, Barton, Jane F V, Southampton, Volume 2c, Page 51”

With each sibling who married and left the family home, the Williams household changed. What was once a house filled with the sounds of children had gradually quieted as each one ventured into their own lives. For Samuel, now well into his twenties, the world around him was shifting. His brothers and sisters were settling into their futures, but his own path would take a very different turn, one that would lead to tragedy, speculation, and unanswered questions that still linger to this day.

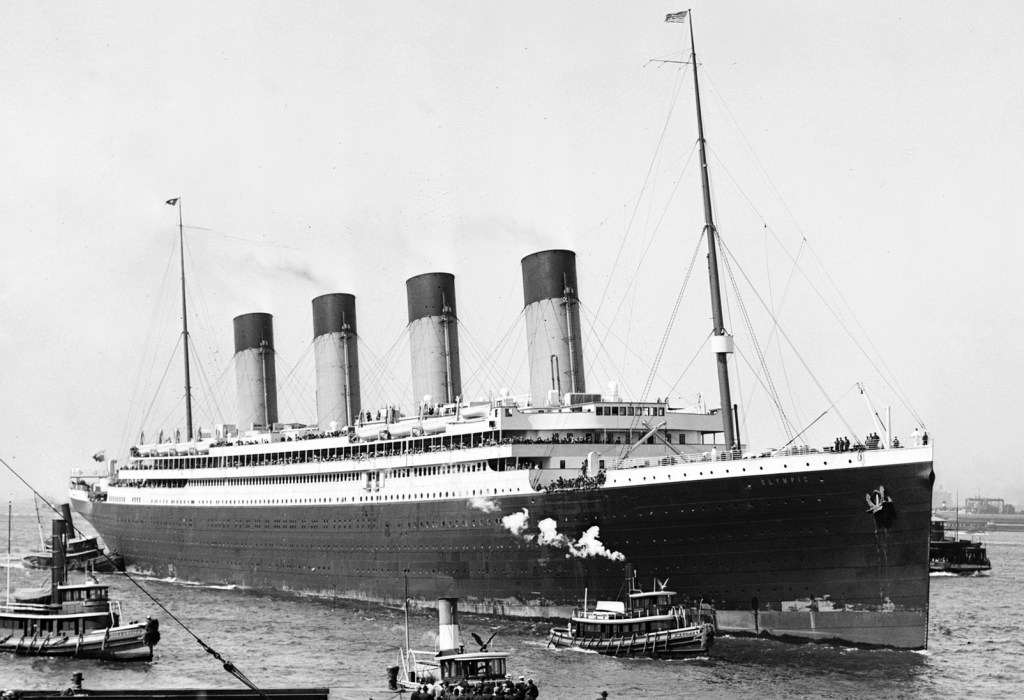

Sometime around 1911, Samuel made a fateful decision, one that took him away from the familiar streets of Southampton and onto the decks of the “RMS Olympic”, one of the grandest ocean liners of its time. While records of his service aboard the ship remain elusive, multiple sources confirm that he was indeed a crew member, embarking on what should have been a promising chapter in his life at sea. However, something happened during his time aboard, something that would change the course of his future forever.

There was an altercation, an event that, for reasons now lost to time, resulted in Samuel being banned from sailing. The exact details of this incident remain frustratingly unclear. Was it a moment of reckless impulse, a dispute that escalated beyond his control, or something more complicated? No official record has surfaced to explain what truly happened, only that whatever transpired was serious enough to cost him his position.

This was a turning point in Samuel’s life. His time aboard the “Olympic” should have been an opportunity, a step toward stability and purpose, but instead, it ended in disgrace. It was a moment that pushed him toward an uncertain path, one that, in the end, would lead him to make the worst decision of his short life.

The RMS Olympic was a British ocean liner and the lead ship of the White Star Line's trio of Olympic-class vessels, which included the infamous Titanic and Britannic. Constructed by Harland and Wolff in Belfast, Olympic was launched on October 20, 1910, and embarked on her maiden voyage on June 14, 1911. Designed to provide luxurious transatlantic passenger service, she was renowned for her grandeur and size, measuring approximately 882 feet in length and boasting a gross tonnage of around 45,000 tons.

Olympic's early career was marked by both achievement and adversity. Shortly after entering service, she was involved in a collision with the British warship HMS Hawke in September 1911, resulting in significant damage to both vessels. Despite this setback, Olympic was repaired and returned to service, quickly earning a reputation for her opulent accommodations and reliability on the North Atlantic route.

With the onset of World War I in 1914, Olympic's role transformed from a passenger liner to a troopship. Repainted in a dazzle camouflage pattern to obscure her size and speed, she was affectionately nicknamed "Old Reliable" by those who served aboard her. Olympic transported thousands of troops to various theaters of war and was notable for her resilience, including an incident in 1918 when she reportedly rammed and sank a German U-boat, U-103, while en route to France.

After the war, Olympic underwent extensive refurbishment to modernize her facilities and returned to civilian service in 1920. She resumed transatlantic crossings, offering passengers a blend of comfort and speed. Throughout the 1920s, Olympic remained a popular choice for travelers, symbolizing the elegance and technological advancement of the era's ocean liners.

However, the Great Depression of the 1930s led to a decline in demand for transatlantic travel. Combined with the emergence of newer, more advanced ships, Olympic's prominence began to wane. In 1934, she was involved in another collision, this time with the Nantucket lightship, resulting in the deaths of several lightship crew members. This incident, along with the economic challenges of the time, contributed to the decision to retire the vessel.

In 1935, after a distinguished career spanning over two decades, the RMS Olympic was withdrawn from service and subsequently dismantled. Many of her fittings and fixtures were auctioned off, with some finding homes in hotels and private residences, preserving the legacy of one of the early 20th century's most iconic ocean liners.

Samuel had always been a man of the sea. Southampton, the city he called home, was a place where ships and sailors shaped the very fabric of life. But after the altercation aboard the RMS Olympic, his future in maritime work had been cast into uncertainty. Banned from sailing or working aboard ships, Samuel found himself in a desperate position. The life he had known, the sense of purpose he had found in his work, had been ripped away from him. And so, faced with limited choices, he made a fateful decision.

Drawing from his brother Edward’s name and experience, Samuel took a bold risk. He signed up under a false identity to serve as a fireman aboard the RMS Titanic, the magnificent new liner that the world had declared "unsinkable." Whether it was a last attempt to reclaim his place at sea, an act of defiance, or sheer desperation, we can only speculate. But what is certain is that on Saturday the 6th day of April, 1912, Samuel bid farewell to his family and stepped aboard the Titanic, ready to take on his duties as a fireman in the ship’s massive boiler rooms.

Did he feel a sense of redemption as he walked up the gangway? Did he believe this voyage would be a fresh start, a chance to put the past behind him? Or was there a heaviness in his heart, an unshakable sense that fate had already decided his path? Whatever he felt in those final days, Samuel’s decision to board the Titanic would be the one that sealed his fate.

Being a fireman aboard Titanic was a relentless, backbreaking existence, spent in a world of heat, dust, and deafening noise, with little rest and no luxury. It was a life of labor, hardship, and sacrifice, a life that, in the end, cost many of them everything.

A fireman aboard the RMS Titanic, like Samuel Solomon Williams, endured one of the most grueling and hazardous jobs on the ship. Working deep in the belly of the great liner, firemen, also known as stokers were responsible for shoveling tons of coal into the massive furnaces that powered Titanic’s 29 colossal boilers. The job required immense physical strength, endurance, and resilience, as they labored in near-unbearable conditions.

The atmosphere below deck was oppressive, filled with the choking dust of coal and the relentless heat radiating from the roaring furnaces. The temperature in the boiler rooms could soar well over 100 degrees Fahrenheit (38°C), causing firemen to sweat profusely. Many worked stripped to the waist, their skin blackened by soot, their bodies glistening with sweat. The noise was deafening, the constant hissing of steam, the roar of burning coal, and the metallic clatter of shovels against iron grates filled the air, making conversation nearly impossible. The dim glow from the fireboxes cast flickering shadows across the cavernous boiler rooms, creating an eerie, infernal atmosphere that was as exhausting mentally as it was physically.

The working conditions were brutal. Firemen worked in four-hour shifts, often referred to as "watches," with only brief rest periods before they had to return to the inferno of the boiler rooms. Titanic burned around 600 tons of coal per day meaning that an army of stokers and trimmers were needed to keep the fires alive. Firemen shoveled coal continuously, their bodies aching from the repetitive and exhausting motion. Their faces and hands were coated in grime, and the thick air made breathing difficult, often causing persistent lung and throat irritation. Many suffered from heat exhaustion and dehydration, gulping down water whenever possible, though it was never enough to fully replenish what they lost through sweat. There was always the ever-present danger of injury, coal could collapse suddenly, scalding steam could escape from the pipes, and missteps on the greasy floors could lead to falls.

Sleeping arrangements were crude and far from comfortable. Firemen were housed in cramped quarters deep within the ship, near the boiler rooms. These small, windowless compartments were shared among several men, with narrow metal bunks stacked on top of one another. The air was thick with the lingering scent of coal dust, sweat, and dampness. There was little chance to properly clean up after a shift, so the bedding and walls quickly became grimy. Sleep was difficult, not only because of the oppressive heat but also due to the ship’s vibrations and the noise from the machinery running through the night. Many firemen, completely drained from their shifts, simply collapsed onto their bunks, still covered in soot, with only a thin blanket for comfort.

Despite the harsh conditions, there was a sense of camaraderie among the firemen. They worked side by side, enduring the same hardships, relying on each other in an environment that demanded physical and mental toughness. Many were seasoned sailors and workers who had spent their lives in engine rooms and boiler houses, accustomed to the grueling nature of their profession. There was little time for socializing outside of work, but they often gathered in their quarters for a smoke, a drink, or a brief conversation before their next shift.

When Titanic struck the iceberg on April 14, 1912, the firemen were among the first to understand the true gravity of the situation. As water began flooding the lower compartments, some continued to stoke the boilers to keep the ship’s lights running and the pumps operating for as long as possible, delaying Titanic’s sinking. Others desperately tried to escape the lower decks, navigating through rapidly rising water and sealed-off bulkheads that trapped many below.

Few firemen survived the disaster. The firemen who did manage to escape found little hope once on deck, most were considered part of the "lower class" crew and were not prioritized for lifeboats. The ocean, dark and merciless, claimed many of these brave men who had worked in Titanic’s depths, unseen and uncelebrated, keeping the ship alive until the very last moments.

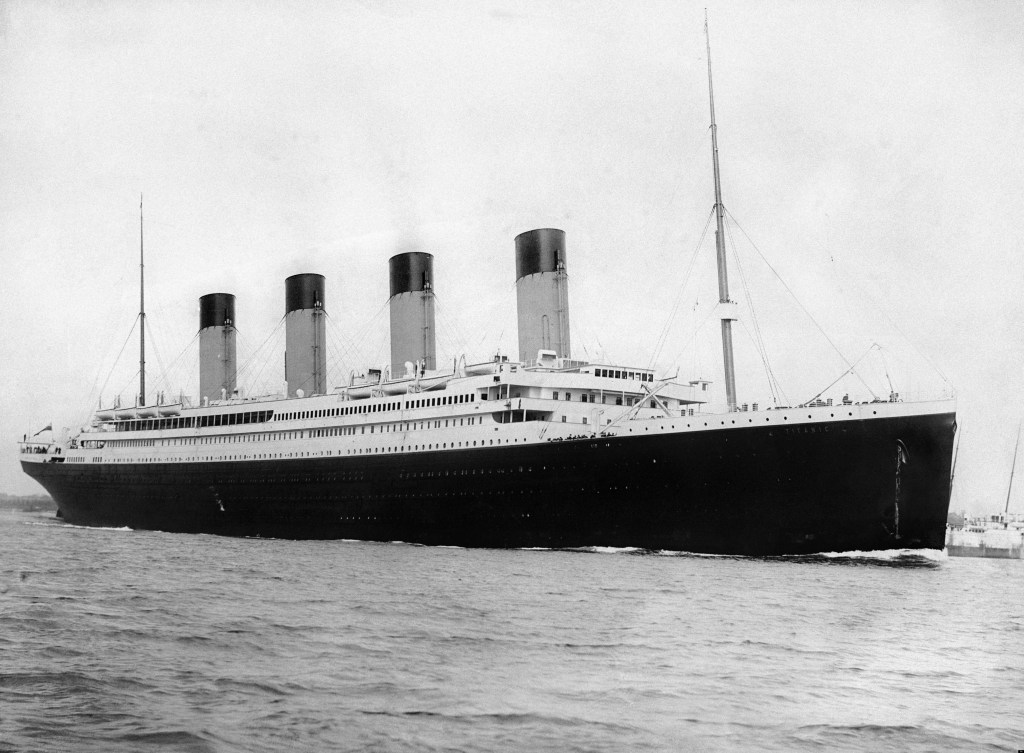

The RMS Titanic was one of the most remarkable ships ever built, a true marvel of early twentieth-century engineering and luxury. Designed to be the largest and most magnificent ocean liner of its time, it was constructed by the Belfast-based shipbuilding company Harland & Wolff for the White Star Line. Titanic was part of a trio of massive sister ships, alongside the Olympic and Britannic, and was meant to set a new standard in transatlantic travel.

The ship's construction began in 1909, taking nearly three years to complete. Thousands of workers toiled on its massive frame, crafting a vessel that stretched 882 feet and 9 inches in length, making it the longest ship in the world at that time. It stood over 175 feet from the keel to the top of the funnels, with a beam of 92 feet and a total weight of 46,328 gross tons. With its triple-screw propulsion system powered by two enormous reciprocating steam engines and a low-pressure Parsons turbine, the Titanic could reach speeds of up to 23 knots. The ship’s four towering funnels, only three of which were functional, became an iconic symbol of power and grandeur, while the fourth was added for aesthetic balance and ventilation.

Titanic was built with an advanced safety system, incorporating a double-bottom hull and sixteen watertight compartments, each with doors that could be sealed electronically from the bridge. This design was intended to make the ship nearly unsinkable, as it was believed she could remain afloat with up to four compartments flooded. The name Titanic itself was chosen to evoke a sense of immense strength and durability, capturing the imagination of the public.

The ship's interiors were the pinnacle of Edwardian elegance and luxury. First-class passengers were treated to accommodations that rivaled the finest hotels on land, with lavishly decorated staterooms, opulent dining rooms, and grand social halls. The ship boasted a sweeping grand staircase topped with an ornate glass dome, lined with polished oak paneling, gilded trim, and exquisite chandeliers. There was a Parisian-style café, a lavish first-class smoking room, and an elaborate dining saloon that could seat hundreds. First-class travelers also had access to a swimming pool, a Turkish bath, a gymnasium, and a squash court, amenities that were rare even in the wealthiest homes at the time.

Second-class accommodations, while not as extravagant, still offered an exceptional level of comfort compared to other liners of the era. These passengers enjoyed comfortable cabins, their own dining areas, and an elegant library for leisure. Third-class, often referred to as steerage, was designed with practicality in mind but still provided better living conditions than most other ships of the time. While simple, the third-class areas were clean and comfortable, with communal dining halls and dormitory-style cabins. Many of those in steerage were immigrants seeking a new life in America, drawn by the promise of the world's most luxurious and modern ship.

The Titanic also represented the height of technology for its time. It was equipped with a state-of-the-art Marconi wireless telegraph system, which allowed passengers and crew to send messages across the Atlantic. This was a significant innovation, making it one of the most connected ships at sea. The ship’s lighting and heating systems were also cutting-edge, powered by its massive coal-burning boilers that fed steam to the engines. Over 600 tons of coal were burned each day to keep the ship moving, with stokers working tirelessly below deck to keep the furnaces running.

Every detail of Titanic’s design and construction was meant to convey sophistication, modernity, and security. When she left Southampton on April 10, 1912, for her maiden voyage to New York, she was hailed as the pinnacle of ocean travel, carrying some of the wealthiest and most influential people in the world alongside ordinary passengers seeking a fresh start. The ship embodied human ambition, blending unparalleled luxury with the promise of safety, yet ultimately became one of the most famous and tragic vessels in history.

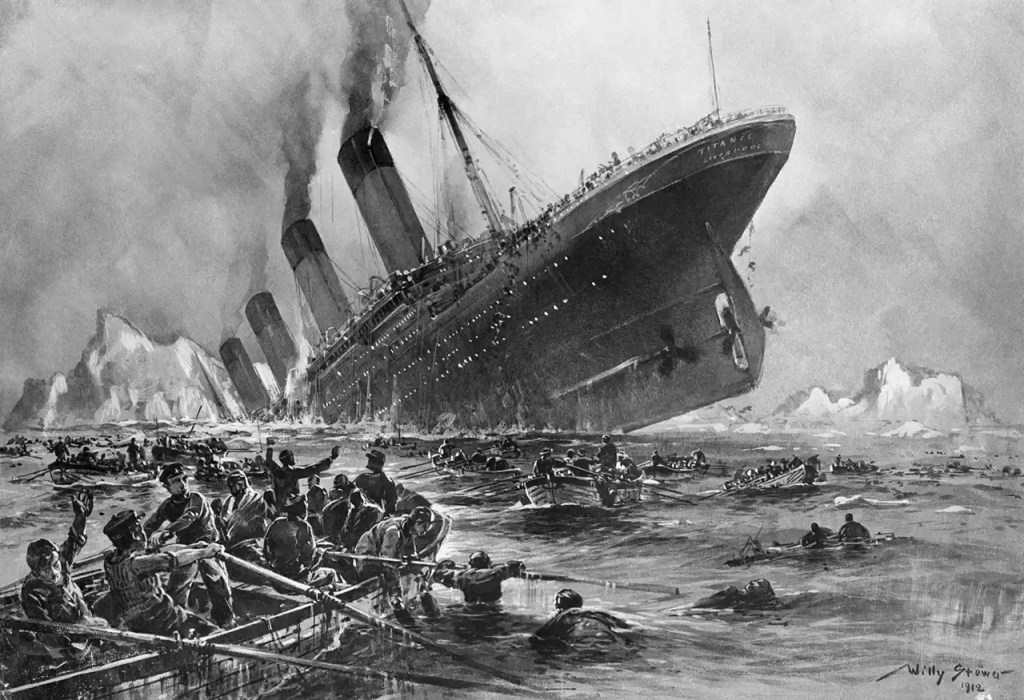

The North Atlantic stretched endlessly into the darkness, a vast, merciless void beneath an eerily clear sky. The Titanic, a triumph of human engineering and luxury, sliced through the still water at nearly full speed, the great ship appearing invincible under the glow of her deck lights. The passengers above enjoyed a peaceful night, the first-class elite wrapped in fur coats as they strolled the promenade, while third-class families huddled together below, dreaming of new beginnings in America.

Far beneath the grandeur, in the depths of the ship’s hull, Samuel Solomon Williams labored in the boiler rooms, a place where no starlight reached. The air was thick with heat and coal dust, the only illumination coming from the roaring furnaces that fed Titanic’s mighty engines. Samuel’s body ached from hours of relentless shoveling, sweat dripping from his brow as he fueled the ship’s relentless pace. His shift was nearly over. Soon, he would retreat to the cramped firemen’s dormitory on D-Deck, where he might steal a few hours of rest before returning at 8am for his next 4 hour shift the blistering heat once more.

Then, at 11:40 p.m., 20 minutes before Samuel’s second shift of the day (20:00 to midnight) finished, the unthinkable happened.

A sudden cry from the crow’s nest shattered the quiet above "Iceberg, right ahead!" The ship's officers rushed to react, ordering the wheel hard to starboard, the engines reversed, but Titanic was too vast, too powerful, to turn in time. The iceberg loomed out of the darkness, a ghostly white mountain of ice, and tore a jagged wound down her starboard side. Steel groaned and buckled as the iceberg scraped along her hull, rupturing the first six watertight compartments. The damage was not explosive, but it was fatal. The unsinkable ship was sinking.

Samuel would not have felt the initial impact, not like the passengers in their cabins, some of whom were startled awake by a faint shudder. But moments later, deep in the ship’s belly, the firemen heard the sharp, gut-wrenching sound of steel being torn apart. Then, before they had time to react, the ocean came surging in. A wall of black water burst into Boiler Room 6, steam pipes hissed violently, and men scrambled in panic. Those near the breach were swallowed instantly. Others clawed their way toward the watertight doors, hoping to escape before they slammed shut. The roar of the Atlantic filled the space, drowning out the shouts and cries of those left behind.

Above, passengers peered out of their cabins, confused by the sudden stop. The ship felt solid beneath their feet. Stewards reassured them, telling them there was no need for concern. But in the bridge, Captain Edward Smith’s face was grim. The Titanic had less than three hours. The wireless operators tapped out desperate distress signals, sending the newly-adopted SOS into the night, hoping for a miracle. The Carpathia answered, but she was over four hours away. Titanic did not have that long.

As the ship took on water, the bow began to sink lower. Officers hurried to wake the passengers, urging them to dress warmly and head to the boat deck. In first-class, the wealthy took their time, reluctant to believe that such a magnificent vessel could truly be in danger. In third-class, chaos unfolded. Many passengers, trapped behind locked gates meant to prevent them from wandering into first and second-class areas, pounded on doors, pleading to be let through.

Down below, the firemen continued to work, shoveling coal to keep the ship’s power running, even as water rose around their feet. They knew they were doomed, but if they could keep the lights burning just a little longer, more passengers might find their way to safety. Samuel was there, somewhere in the bowels of the ship, perhaps in Boiler Room 6, the first to be breached, or further down, in the infernal heat of Boiler Room 5. Did he run? Did he claw his way through the rising water, searching for a ladder, a corridor, any path to salvation? Or did he remain, alongside the men who chose duty over fear, shoveling coal into the roaring fires to keep the lights burning, to buy the passengers above just a few more precious moments?

Perhaps he was trapped, the gangways sealed to slow the flooding, locking him and the others in a steel tomb as water clawed at their heels. Perhaps he fought, struggling through the labyrinth of machinery and gangways, only to find every path cut off, every door a dead end. Perhaps he held on to the very last, the water up to his chest, then his chin, gasping for one final breath before the ocean claimed him.

Above deck, the lifeboats were being lowered. The air was filled with the wail of distress rockets, the chilling sound of metal grinding under pressure, and the cries of desperate passengers. "Women and children first!" the officers shouted, forcing back panicked men who tried to board. Husbands were torn from their wives, fathers from their children. Some refused to leave, unwilling to believe Titanic would actually go down. Others knelt in prayer, staring in disbelief at the tilting deck.

As the bow plunged deeper, terror spread. The once grand ship, a floating palace of light and music, had become a scene of horror. Passengers scrambled for any lifeboat still within reach. Some jumped into the sea, hoping to swim to safety, but the water was lethal, 28 degrees Fahrenheit, cold enough to kill within minutes.

At 2:17 a.m., the Titanic’s lights flickered one last time before vanishing, plunging the ocean into darkness. Then, a terrible groaning sound echoed through the night as the ship’s structure gave way. Titanic split in two. The stern, momentarily steadied, lifted high into the sky, standing almost vertical, silhouetted against the stars. For a brief moment, it seemed frozen in time. Then, with one last, agonizing plunge, it disappeared beneath the waves.

For a few moments, the sea was alive with screams. Hundreds of voices, pleading for help, crying for loved ones. Then, one by one, they faded, until only silence remained.

Samuel Solomon Williams was among them. Whether he was trapped in the flooding depths of the ship or thrown into the freezing blackness above, he never made it home. His body was never recovered. His name, like so many others, was added to the list of those lost, a life cut short in the most harrowing disaster of its time.

The Carpathia arrived at dawn, pulling the 705 survivors from their lifeboats. They sat shivering in the morning light, wrapped in blankets, their eyes hollow. Many had lost everything, their families, their dreams, their future. As the sun rose over the Atlantic, the vast ocean stretched out before them, empty and unbroken, as if the Titanic had never been.

But the world would never forget. The Titanic’s story, the lives lost, the bravery and sacrifice of those who fought until the end, would be remembered for generations. And among them, in the depths of history, remains Samuel Solomon Williams, a fireman, a son, a man who gave his last breath aboard the most famous ship in the world.

It is impossible to truly comprehend the depth of the pain and anguish that Samuel’s family must have felt in the wake of the Titanic disaster. For Rebecca and Richard, Samuel’s parents, the waiting must have been unbearable. With no word, no confirmation of his fate, they were left in an agonizing limbo, caught between hope and fear. To lose a son in such a horrific, sudden way, one that shattered the world’s illusions about the Titanic, must have been a grief beyond measure.

Samuel had left for that fateful voyage with such hope, perhaps even naivety, as many did. To think that their beloved son was caught in the very depths of that tragedy, trapped with the other firemen in the boiler rooms, doing what they had been ordered to do, to keep the ship's engines running for as long as possible, only deepens the heartache. Those men, working tirelessly below deck in the stifling heat, must have known their fate long before it was realised by those above.

The pain of knowing they were the first to feel the ship’s devastating impact, yet were the last to escape its wreckage, is heart-wrenching. So many lives were lost in that freezing, murky water, but the lives left behind, those waiting for answers, those who would never see their loved ones again, were left to live with the scars of that night forever. Samuel's family was not just robbed of him, they were denied the closure, the certainty of knowing his final moments, a cruel fate that so many others shared.

It’s hard to even imagine the kind of sorrow Samuel’s parents must have felt, sitting in that terrifying silence, waiting for news that would never come. Each day must have stretched into a painful eternity, their hopes of his return slowly fading as the days passed with no word from the Titanic. In the end, they were left with the crushing reality of loss, a son lost to the sea and to history, with only fleeting memories of his life to hold onto.

The lives lost on that ship, from the passengers to the crew, are tragic in their own right, but it is the families left behind, the mothers, fathers, children, and spouses, whose grief echoes through time. Samuel’s family, like so many others, had their world shattered that night. And though Samuel’s name may be etched in history, the personal loss, the gaping hole left in their hearts, would never truly fade.

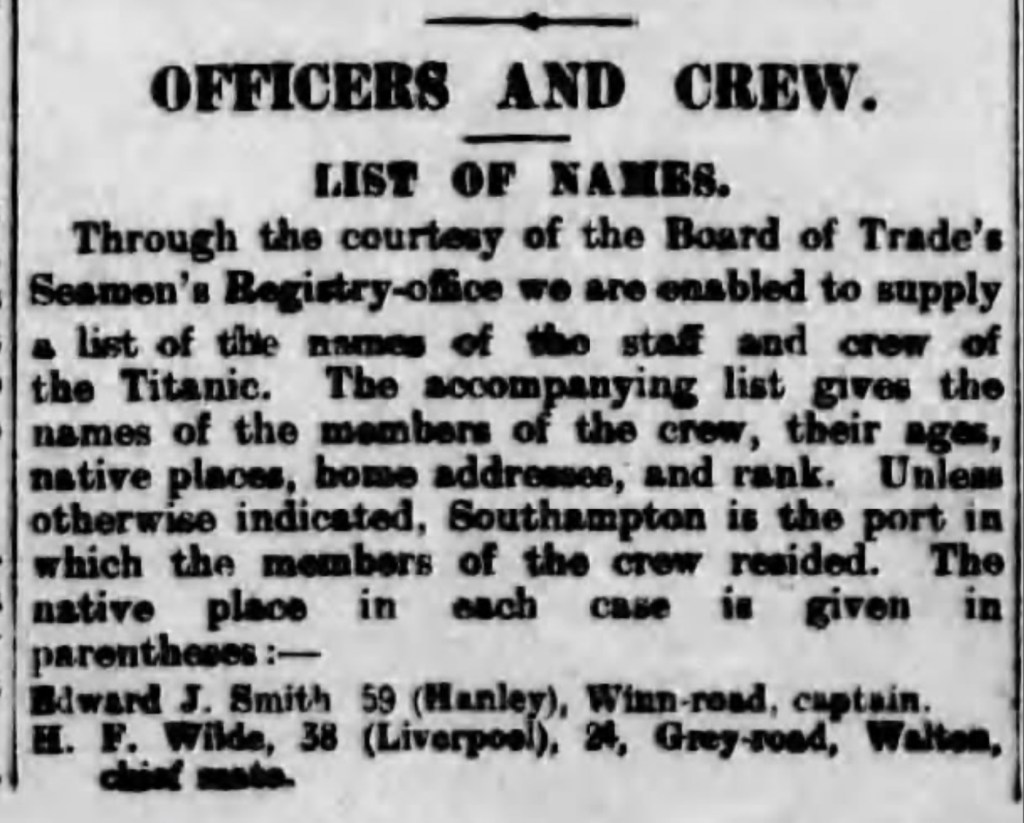

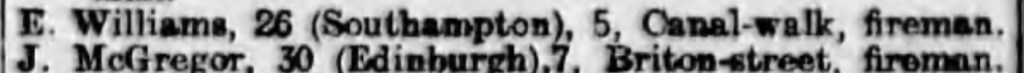

Just days after the Titanic sank beneath the icy waters of the Atlantic, the world scrambled to piece together the details of who had been aboard. Families waited in agony, desperate for news, scanning every printed word for confirmation of survival or loss. Among the many names listed in the Western Morning News on Wednesday, the 17th day of April, 1912, was that of Samuel Solomon Williams, though not under his real name.

The article, courtesy of the Board of Trade’s Seamen’s Registry Office, attempted to provide a full record of the ship’s officers and crew. In it, Samuel was listed as "E. Williams, 26, Fireman, from 5, Canal Walk, Southampton." due to him signing on in his brother Edward’s name. But the reality was clear, Samuel had boarded the Titanic under an assumed name, possibly as his last chance to return to sea after his ban from the Olympic.

This brief mention in a newspaper, buried among hundreds of other names, would be one of the last records of Samuel’s existence. His real identity lost in print, just as his life was lost at sea.

The beginning of the article reads as follows

OFFICERS AND CREW.

LIST OF NAMES.

Through the courtesy of the Board of Trade's Seamen’s Registry-office we are enabled to supply a list of the names of the staff and crew

of the Titanic.

The accompanying list gives the

names of the members of the crew, their ages, native places, home addresses, and rank. Unlens otherwise indicated, Southampton is the port in which the members of the crew resided. The native place in each case in given in parentheses:—

E. Williams, 26, (Southampton) 5, Canel Walk, Fireman.

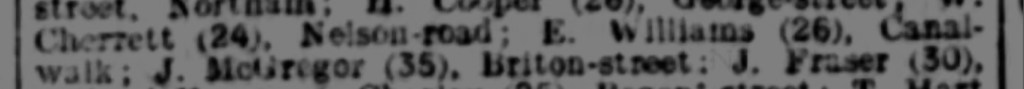

A list of crew members was also printed in the Sunday Dispatch newspaper on Sunday, the 21st day of April, 1912. Once again, Samuel was listed under the name E. Williams, (26), Canal Walk, the identity he had taken in order to secure his place aboard the Titanic. Though recorded under another name, his fate was his own.

After the unimaginable loss of their beloved son Samuel, Rebecca and Richard Williams, like many others who had lost family members aboard the Titanic, faced a future overshadowed by grief. No amount of money, no compensation, could bring back the child they had raised, loved, and cherished. Yet, in the wake of the disaster, a measure of financial assistance was extended to those who had been left behind.

As class G dependents, Samuel’s parents were eligible to receive financial assistance from the Titanic Relief Fund, which was established to support the families of the victims. This fund, though intended to provide some relief to those who had lost loved ones, was no substitute for the loss they had suffered. It could not replace their son. It could not ease the sharp ache in their hearts. It could not undo the finality of that cold, lonely night in April 1912.

The harsh reality was that the family would never have the closure of bringing Samuel home. His body, like many others, was never recovered. The sea had claimed him, and with it, any chance of a proper burial, any hope of laying him to rest in the place where his parents could visit him and mourn in peace. For Rebecca and Richard, the pain of not having a gravesite to visit, a final place to honor their son, was a sorrow that would stay with them for the rest of their lives.

No matter the financial relief they received, it could never fill the void left by Samuel’s loss. It was a cruel reminder that the greatest tragedy of all could not be fixed with money. The Williams family, like so many others, would have to carry the weight of that night in their hearts forever. They had lost more than a son, they had lost the opportunity to say goodbye.

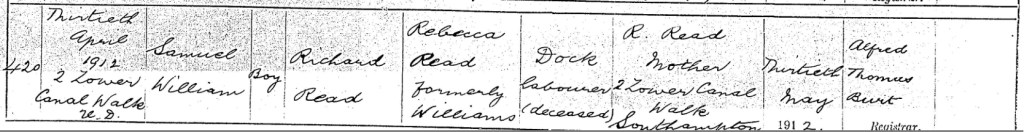

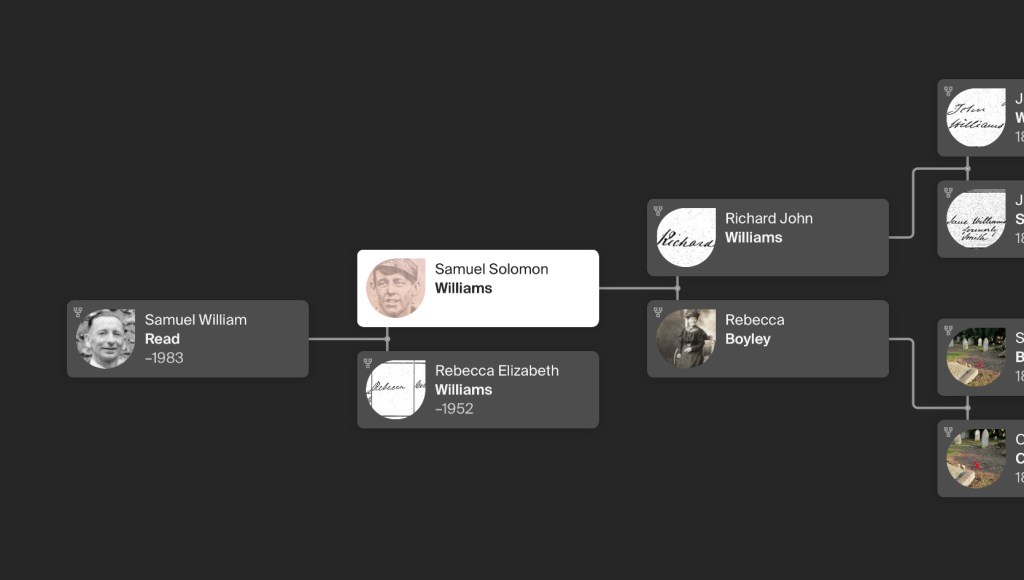

The story of Samuel Solomon Williams’ family does not end with his tragic death aboard the Titanic. In a series of shocking and complex events, Samuel’s widowed older sister, Rebecca Read, found herself facing an unimaginable situation.

On Tuesday, the 30th of April 1912, just weeks after the world had learned of the sinking of the Titanic, Rebecca gave birth to a baby boy, whom she named Samuel William Read. The birth took place at Number 2, Lower Canal Walk, Southampton, and on the birth certificate, the father was listed as "Richard Read (deceased)," her late husband. Richard Hutchin Read had died of pneumonia on the 1st of September 1911, a tragic loss that left Rebecca a widow long before she could have ever anticipated the pain that would follow.

However, the events that unfolded next were far from straightforward. In a twist of fate, Rebecca later went to court, presenting affidavits from surviving Titanic crew members who claimed that Samuel Solomon Williams had been aboard the ship at the time of the disaster. She argued that Samuel, not her late husband Richard, was the true father of her child and sought compensation for a dependent through the Mansion House Fund. The court accepted her claim, and the fund provided compensation, paying pensions to both Rebecca and the child.

This situation has sparked much speculation over the years. Some argue that, given the timing and circumstances, it is possible that Richard Read was indeed the father, and Rebecca, facing hardship, claimed compensation under false pretenses. However, this remains a matter of conjecture. On the other hand, if Rebecca's story was truthful, it would raise even more uncomfortable and tragic questions, as it would suggest an incestuous relationship between her and her brother Samuel, a possibility that, though not confirmed, remains an unsettling aspect of this tragic tale.

Rebecca’s posthumous son, Samuel William Read, grew up with his mother and siblings, continuing the family’s life in Southampton. Later, she found a new partner in James George Yeates, a ship’s painter. While it is unclear whether they ever officially married, they had three additional children together. Rebecca passed away in 1952, but Samuel William Read continued to live on, eventually marrying twice and living a long life before passing away in 1983.

The story of Samuel Solomon Williams and the aftermath of his tragic death are woven into a complex tapestry of loss, hardship, and difficult decisions. While Samuel’s death aboard the Titanic is an undeniable tragedy, the life that followed for his family was filled with questions that would never truly be answered, and burdens that would remain with them for generations.

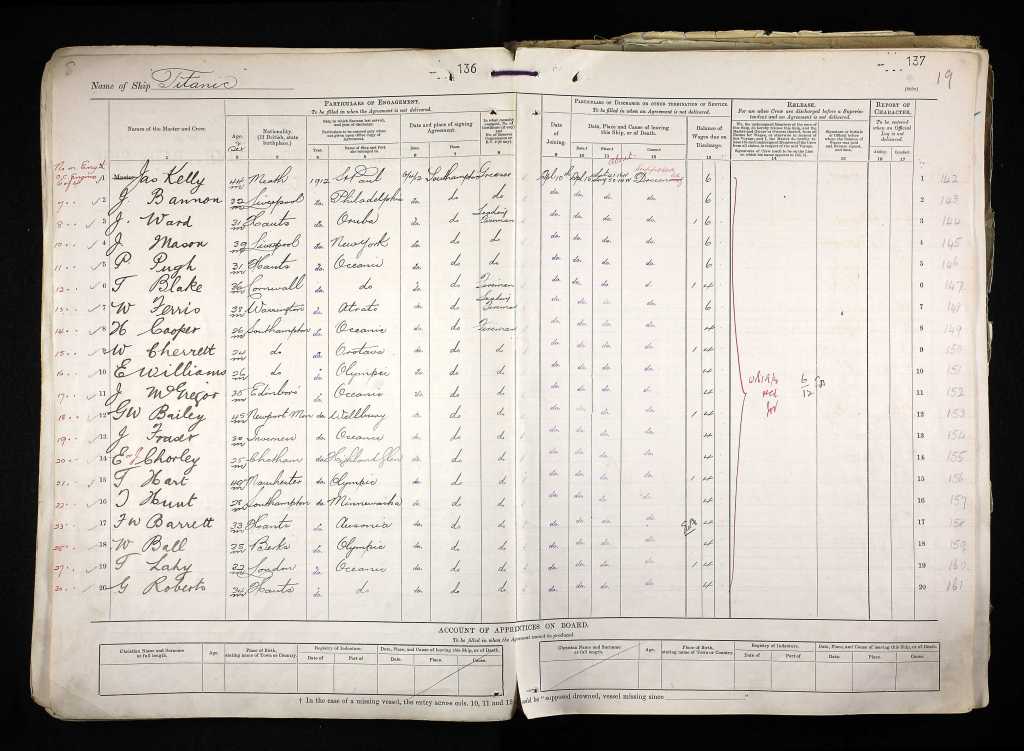

On Thursday, the 31st day of October, 1912, Samuel’s name was recorded in the UK RMS Titanic Crew Records, but not under his own name. Instead, it appeared as E. Williams (Edward), the name he had borrowed in a desperate attempt to secure a place aboard the great ship after being banned from sailing. This single, haunting record is one of the last official traces of Samuel’s existence, a stark and simple entry that holds within it the weight of an entire life lost to the sea.

The document states that E. Williams was 26 years old and from Southampton, that he had served aboard the RMS Olympic before being discharged in 1912. It confirms that on the 6th of April, just days before the Titanic’s maiden voyage, Samuel stood in Southampton and signed his name to the crew agreement, though the name he signed was not his own. He joined the ship as a fireman, one of the countless men whose hands fed the relentless fires that powered the floating palace across the Atlantic.

The final entry in the record is devastatingly brief, a cold notation of an unfathomable loss. It states that E. Williams left the ship, his place of departure marked as **41.16N, 50.14W** a set of coordinates in the vast, unforgiving Atlantic Ocean. The cause of his departure: Drowned, 15 April 1912. He was due wages upon discharge, a sum he would never collect.

The cold ink of bureaucracy cannot capture the truth of what happened to Samuel that night. The record does not tell of the terror he must have felt, trapped deep within the ship’s hull as the sea rushed in. It does not describe the desperate fight for survival, the heat of the boiler rooms suddenly giving way to freezing water, the deafening roar of the ship’s machinery failing as the Titanic took on its fatal wound. It does not speak of the courage it took for Samuel to keep working in the fire-stoked inferno below deck, knowing that his efforts were buying precious moments for those above.

It does not say whether he tried to escape, scrambling through darkened corridors filling rapidly with ice-cold seawater, or whether he went down with his post, swallowed by the depths before he had the chance to see the night sky one last time.

It only says he drowned.

That is what history recorded. But Samuel Solomon Williams was more than just a name on a ledger. He was a son, a brother, a man who had worked tirelessly for his place in the world. And though the ocean claimed him that fateful night, it could never erase him.

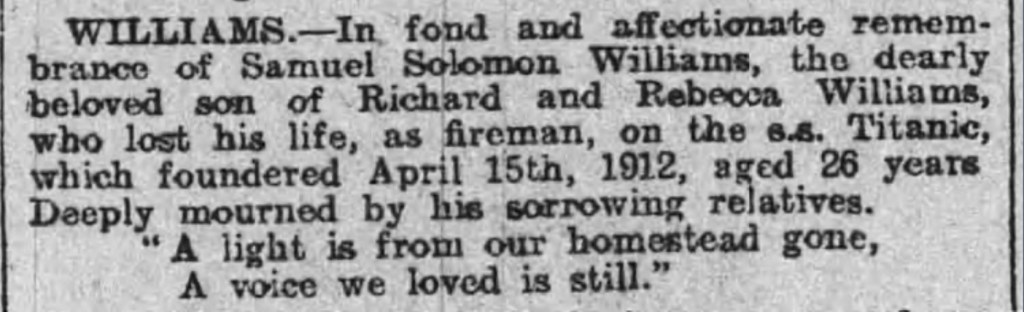

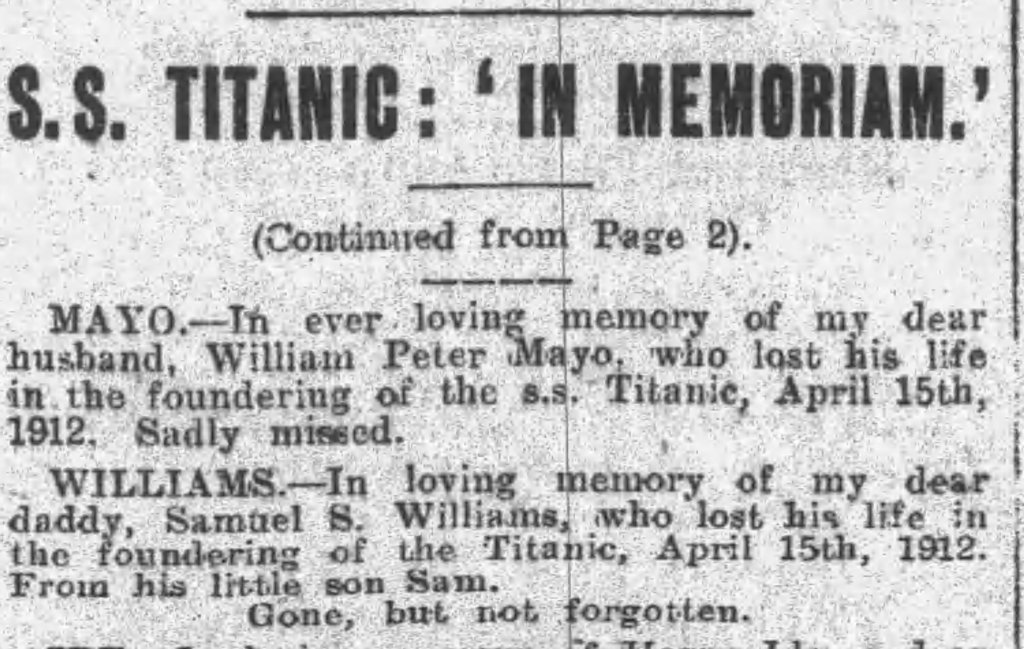

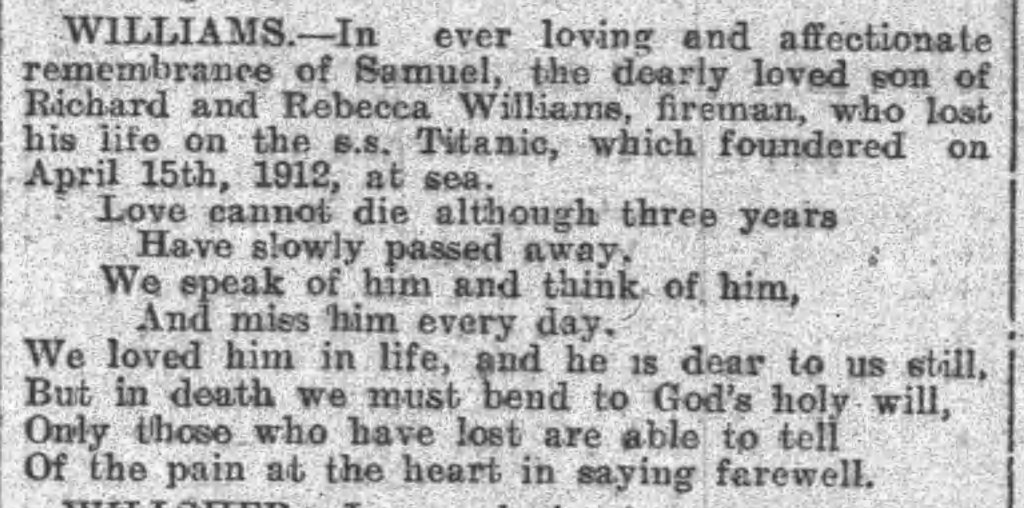

Two years after the Titanic disaster, the grief of Samuel family remained as raw as ever. On Wednesday, the 15th day of April, 1914, the second anniversary of the tragedy, the Southern Daily Echo, printed a small but deeply moving tribute to him, a quiet acknowledgment of the son, the brother, the loved one they had lost.