Welcome to The Life of Samuel Green, 1842-1911, a celebration of the life of my husband’s 2nd great-grandfather. Samuel Green’s story is not just a window into the past, it’s a connection to our shared human experience, an opportunity to honor his legacy, and a reminder of the enduring value of exploring our family roots.

Understanding where we come from gives us a deeper sense of identity and belonging. Every discovery in family history, from an ancient document to an unexpected anecdote, carries the thrill of connection. It’s a joy that combines the personal with the universal, weaving individual stories like Samuel Green’s into the larger tapestry of history.

The Green surname itself tells a fascinating story, with roots in old Saxon and Norse traditions. Derived from the Old English word “grene,” the name originally described someone living near a village green or grassy area. It could also denote youthfulness or inexperience and has links to the “Green Man,” a figure in May Day celebrations. These diverse origins give the Green name a rich and multifaceted heritage.

The earliest recorded instance of the Green surname in our family history dates back to 1420, making it a name steeped in history. Today, the name is widespread: in the United Kingdom, it is the 19th most popular surname, borne by an estimated 120,596 people. In Australia, it ranks 39th, with 45,340 Greens, and in New Zealand, 59th with 5,037. Canada lists Green as its 75th most common surname, with Newfoundland alone ranking it 34th. The United States places Green at 35th, with 455,121 people, while South Africa ranks it 470th with 15,171.

Throughout history, the Greens have been a hard-working and resourceful family. The 1901 Census reveals that many Greens worked as laborers, and by 1939, “General Labourer” was the most common occupation for Green men in the United Kingdom. Meanwhile, 63% of Green women were recorded as engaging in “Unpaid Domestic Duties.” In the United States, labor was also a defining characteristic of Greens, though some took less conventional paths; historical records note over 6,300 Greens with criminal histories.

The Greens have also played significant roles in major historical events. During World War I, 7,188 men and women bearing the Green name served with courage and distinction. Their stories are a testament to the strength and resilience that runs deep in the family.

The Green name is further elevated by individuals who have achieved fame in various fields. These include Sir Hugh Green, a renowned British journalist and Director-General of the BBC; Graham Green, a celebrated novelist and playwright; and Al Green, the legendary soul singer whose music has inspired generations.

The Green family crest adds another layer of richness to this heritage. Typically featuring elements like a green shield, a symbol of hope and joy, the crest often includes motifs such as a stag, representing peace and harmony, or a trefoil, signifying perpetuity and resilience. These symbols beautifully capture the spirit of the Greens, steadfast, enduring, and deeply connected to their roots.

Samuel Green’s story is one piece of this intricate puzzle, and through this blog, we’ll explore his life in detail. From the challenges he faced to the legacy he left behind, his journey is a reminder of the enduring power of family history to inspire, connect, and enrich our lives.

Let’s embark together on this journey into the past, discovering the life of Samuel Green and the remarkable heritage of the Green family.

So without further ado, I give you,

The Life Of Samuel Green, 1842-1911

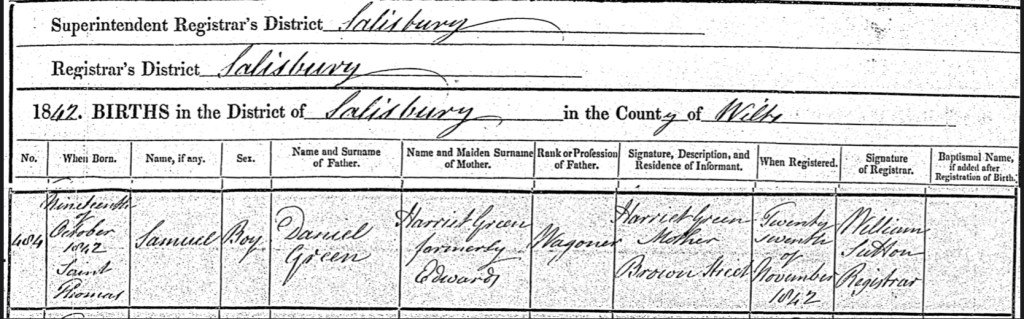

Samuel Green was born on Wednesday the 19th day of October, 1842, in the parish of St. Thomas, Salisbury, Wiltshire, to Daniel Green, a wagoner, and Harriet Green (née Edwards). At the time of his birth, the family lived on Brown Street, a bustling street in the heart of Salisbury. His mother, Harriet, officially registered his birth on Sunday the 27th day of November, 1842, marking the arrival of a child who would carry forward the name of a brother they had tragically lost earlier that year.

Samuel was named after his elder brother, also Samuel Green, who had passed away just a few months before his birth. The first Samuel Green, born in 1841, died on Monday the 11th day of July, 1842, at the tender age of 14 months. His cause of death was listed as teething, a reminder of the fragility of childhood in an era when even common ailments could become life-threatening. Hannah Hawkins, a neighbour from Brown Street, was present at his passing and registered his death on Wednesday the 13th day of July, 1842.

This act of naming their newborn son after his lost brother speaks volumes about the depth of the family’s grief and their desire to honor the memory of the child they had loved and lost. For Daniel and Harriet, it was a way to carry forward the spirit of their first Samuel, while holding onto hope for the future.

Samuel’s arrival brought both joy and poignancy to the Green household, a testament to the strength and resilience of his family in the face of loss. His story begins in the shadow of his brother’s, yet it is uniquely his own, a thread in the fabric of the Green family’s enduring history.

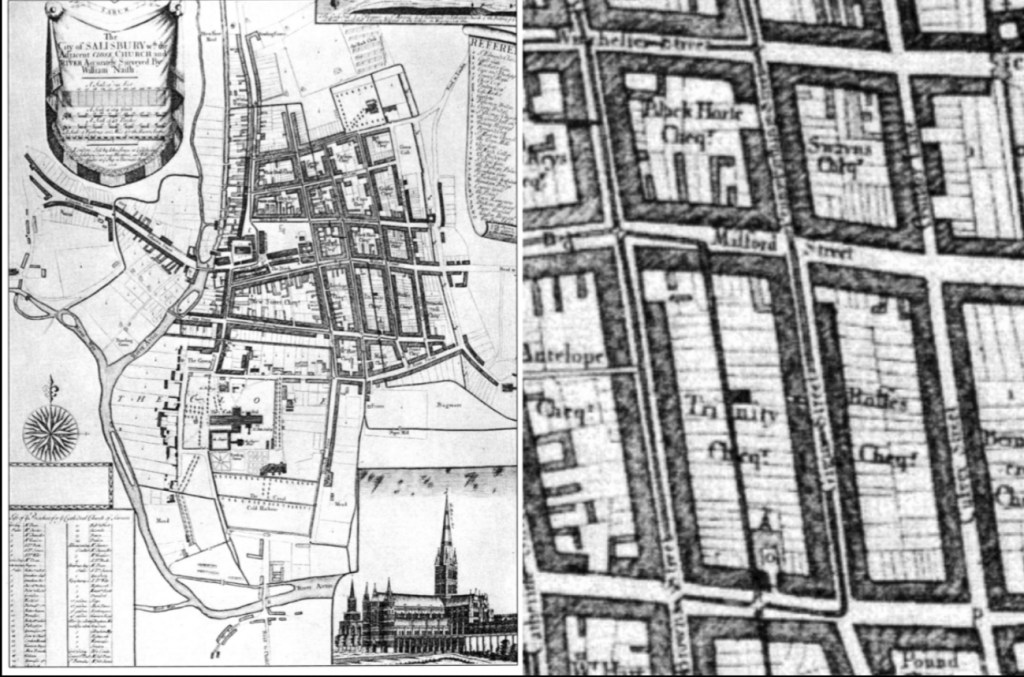

Brown Street, situated in the parish of St. Martin's in Salisbury, Wiltshire, England, is a thoroughfare with historical significance dating back to the medieval period. The street's name was recorded as early as circa 1270–80, indicating its longstanding presence in the city's layout.

In the medieval era, Brown Street formed part of the boundary of St. Martin's parish, which was the oldest parish in Salisbury, existing before the foundation of New Salisbury. The parish was bounded on the north by Milford Street, on the west by Brown Street, and on the south by the River Avon.

The street has been home to several notable buildings over the centuries. For instance, No. 81 Brown Street is a Grade II listed building, recognized for its architectural and historical importance.

Additionally, Brown Street was associated with the Salisbury cutlery industry, which was active from the late medieval period until the early 20th century. The earliest reference to a cutler working in Salisbury dates to circa 1270–80, when "Sebode the Cutiller" held a tenement in Brown Street. This suggests that the street was a hub for artisans and tradespeople, contributing to the city's economic activity.

Over time, Brown Street has evolved, with various residential and commercial properties reflecting the architectural styles of different periods. Its proximity to other historic streets and landmarks in Salisbury underscores its role in the city's urban development. Today, Brown Street remains an integral part of Salisbury's cityscape, embodying layers of history that span several centuries.

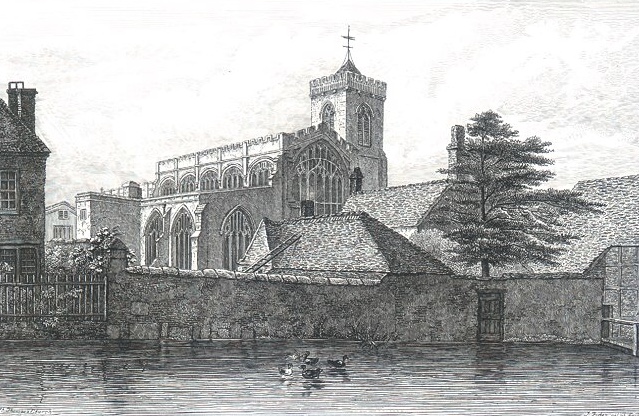

On Tuesday, the 1st day of November, 1842, Daniel and Harriet Green brought their infant son, Samuel, to be baptized at the Church of St. Thomas in Sarum, Salisbury, Wiltshire. It was a moment of both faith and hope for the family, marking Samuel’s formal welcome into their community and faith. The ancient walls of St. Thomas Church, steeped in centuries of history, bore witness to this intimate and deeply meaningful ceremony.

Interestingly, the family name was recorded as “Greene” on Samuel’s baptism record, a slight variation from the commonly used "Green." This small detail is a reflection of the times and the varying ways names were recorded and passed down through generations.

At the time, the Green (or Greene) family was still living on Brown Street, a place that had become the center of their lives. Daniel continued his work as a wagoner, a trade that demanded strength and perseverance but provided for his growing family. Harriet, no doubt, had her hands full at home, especially in the wake of the profound loss they had experienced earlier that year with the passing of their son, also named Samuel.

This act of baptism, coming so soon after their grief, was more than a ritual, it was a symbol of the couple’s resilience and their commitment to moving forward while honoring the memory of their lost child. For Daniel and Harriet, this day would have been filled with both solemnity and quiet joy, a moment of promise and new beginnings for their son, Samuel, within the embrace of their family and faith.

St Thomas's Church, located in the heart of Salisbury, Wiltshire, is a historic Anglican parish church with origins dating back to the early 13th century. It was initially established around 1219 by Bishop Richard Poore as a modest wooden chapel to serve as a place of worship for the laborers constructing the new Salisbury Cathedral. This early structure was soon replaced by a stone building, and by 1238, it was dedicated to St. Thomas of Canterbury, also known as Thomas Becket.

The church's significance grew alongside the development of New Salisbury, and by 1246, it had become an independent parish. In the early 15th century, a tower with a porch was added on the south side of the church. Plans for a stone spire were abandoned when the tower began to lean, leading to its completion with a pyramid roof and battlements later in the century. The tower houses eight bells, with the oldest cast by Abraham Rudhall in 1716 and others by Robert Wells of Aldbourne in 1771.

A significant event in the church's history occurred in 1447 when the chancel collapsed, prompting extensive rebuilding and enlargement. The new chancel was both longer and higher, reflecting the prosperity of Salisbury's merchant class, who contributed to the reconstruction efforts. Notably, William Swayne, a thrice-serving mayor of Salisbury, funded the construction of a chantry chapel in the south aisle, now known as the Lady Chapel.

One of the church's most remarkable features is the large "Doom" painting above the chancel arch. Dating from the late 15th or early 16th century, this mural depicts the Last Judgment and is considered one of the most complete and well-preserved examples of its kind in England.

Today, St Thomas's Church stands as a testament to Salisbury's rich medieval heritage. Its architectural evolution mirrors the city's development, and its historical significance is recognized by its Grade I listing. The church continues to serve as a place of worship and community gathering, embodying a living link to the past in the vibrant heart of Salisbury.

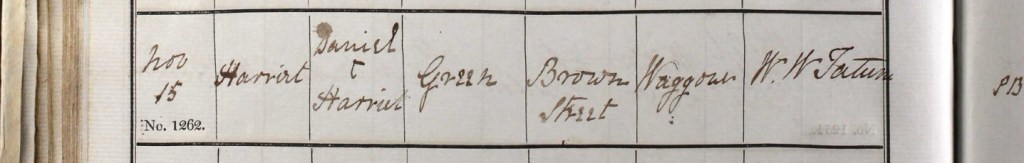

Harriet Green, the 2nd great-aunt to my husband and the sister to Samuel Green, was born into the heart of the family on Wednesday the 8th day of October, 1845, at Brown Street, St Martin’s, Salisbury, Wiltshire, England. Her arrival must have brought immense joy to her parents, Daniel and Harriet Green, who were building their lives in that bustling part of Salisbury.

It was Harriet’s own mother, with the loving hands of a devoted parent, who officially registered her birth in Salisbury a month later, on Wednesday the 12th day of November, 1845. William Sutton, the registrar, carefully documented the details, preserving this precious piece of our family history. He recorded that Harriet was the beloved daughter of Daniel and Harriet Green, living at Brown Street, St Martin’s. Daniel, her father, worked hard as a wagoner, providing for his growing family.

Every time I think about Harriet, I feel a connection to those days in Salisbury, where the roots of my hubby’s family story truly began to take shape.

On Sunday, the 15th day of November, 1846, Samuel’s parents, Daniel and Harriet Green, brought their daughter, Harriet, to be baptised at St. Martin with St. Mary Magdalene Mission Church in Salisbury, Wiltshire. The ceremony, conducted within the modest and welcoming walls of the church, marked an important moment in the family’s life as they dedicated their child to their faith and community.

At the time of Harriet’s baptism, the Green family was still residing on Brown Street, a familiar and bustling part of Salisbury that had been their home for several years. Daniel’s occupation was recorded as a wagoner, a reliable and steadfast trade that played a crucial role in supporting his growing family.

This day would have been significant for Daniel and Harriet, offering a moment of reflection on their enduring faith and the blessings of family life. Little Harriott’s baptism was not only a religious milestone but also a celebration of hope and continuity for a family deeply rooted in their community and bound together by love and resilience.

St. Martin's Church, located in Salisbury, Wiltshire, is a historic parish church with origins predating the establishment of the city's cathedral. The chancel of the church was constructed around 1230, followed by the addition of a tower and spire in the 14th century. The nave and aisles underwent reconstruction during the 15th century. In the mid-19th century, specifically from 1849 to 1850, the church underwent restoration under the direction of architects Thomas Henry Wyatt and David Brandon. This restoration aimed to preserve the church's historical architecture while accommodating the needs of the contemporary congregation.

In 1880, to address the spiritual needs of Salisbury's expanding population, the mission church of St. Mary Magdalene was established on Gigant Street. This mission church, which provided 250 free sittings, offered both weekday and Sunday services and was served by a curate from St. Martin's. However, in 1940, St. Mary Magdalene's was closed and subsequently repurposed as a Deaf Centre.

Throughout its history, St. Martin's has been associated with the Anglo-Catholic tradition within the Church of England. By 1887, the church had firmly embraced this tradition, with the rector at the time introducing eucharistic vestments and catholic ceremonial practices. This alignment with Anglo-Catholicism reflects the church's commitment to the principles of the Oxford Movement, which sought to reaffirm the catholic heritage of the Anglican Church.

Today, St. Martin's Church continues to serve its parishioners, upholding its rich historical and spiritual legacy. The church's architecture, encompassing elements from the 13th to the 15th centuries, stands as a testament to its enduring presence in Salisbury. Its Grade I listed status underscores its significance as a site of historical and cultural importance.

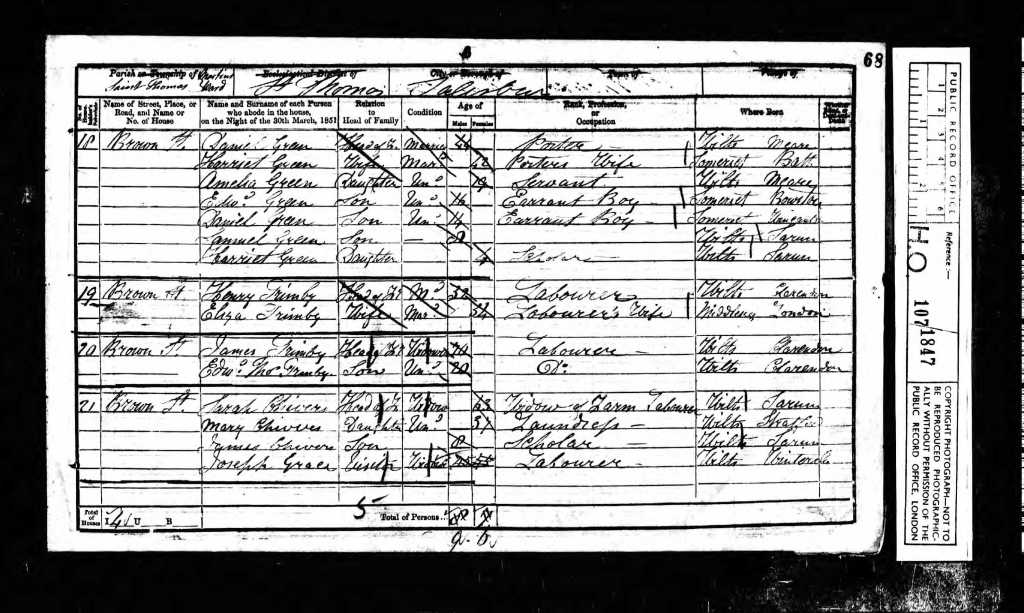

On Sunday, March 30, 1851, the very day the 1851 census was completed, Samuel Green, along with his parents, Daniel and Harriet, and his siblings—Edward, Harriet, Daniel, and Amelia—were living at their home on Brown Street in St. Thomas, Salisbury. This census provides a snapshot of the Green family during a pivotal time in their lives, offering a glimpse into their daily existence and roles within the household.

At this point, Daniel, Samuel’s father, had transitioned from his previous work as a wagoner and was now employed as a porter, a job that would have involved manual labor and a steady presence in the community. Harriet, Samuel’s mother, was listed as a “Porter’s Wife,” a role that reflected her support of her husband’s work while managing the home and caring for the children.

Samuel’s siblings also played important roles within the household. His sister, Amelia, worked as a servant, as well as likely contributing to the household chores and helping with the care of the family. Meanwhile, his brothers, Edward and Daniel, were employed as errand boys, assisting in various tasks and running errands for others in the neighbourhood.

This census not only captures the hard-working nature of the Green family but also highlights the challenges they faced in maintaining their household. Despite the hardships, the family’s dedication to one another and their resilience were evident as they navigated their roles within the community. Their home on Brown Street was a place of both responsibility and support, where each member contributed to the family's livelihood and the nurturing of their close-knit bond.

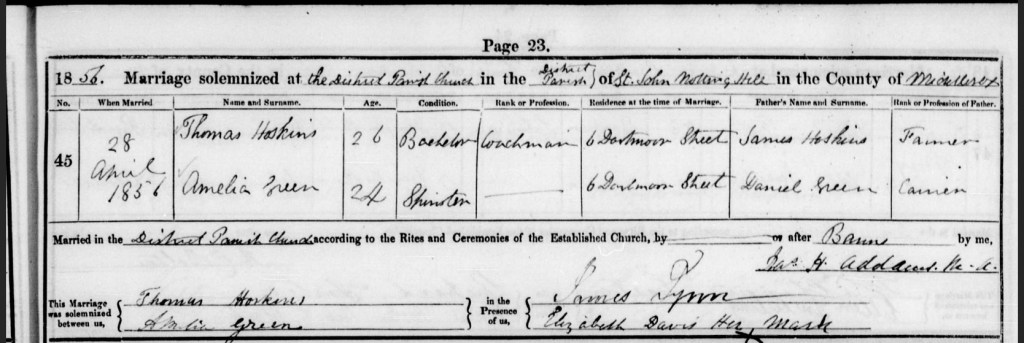

Samuel's sister, Amelia Green, a 24-year-old spinster, married Thomas Hoskins, a 26-year-old bachelor and coachman, on April 28th, 1851, at St. John’s Church in Notting Hill, Middlesex, England. At the time of their marriage, both Amelia and Thomas listed their residence as Number 6, Dartmoor Street.

In the marriage register, they recorded their fathers’ names and occupations: Amelia’s father, Daniel Green, was a carman, while Thomas’s father, James Hoskins, was a farmer. Standing beside them as witnesses were James Lynn and Elizabeth Davis, the latter of whom left her mark with an "X" in place of a signature. Their wedding, solemnized in the historic church, marked the beginning of their journey together as husband and wife.

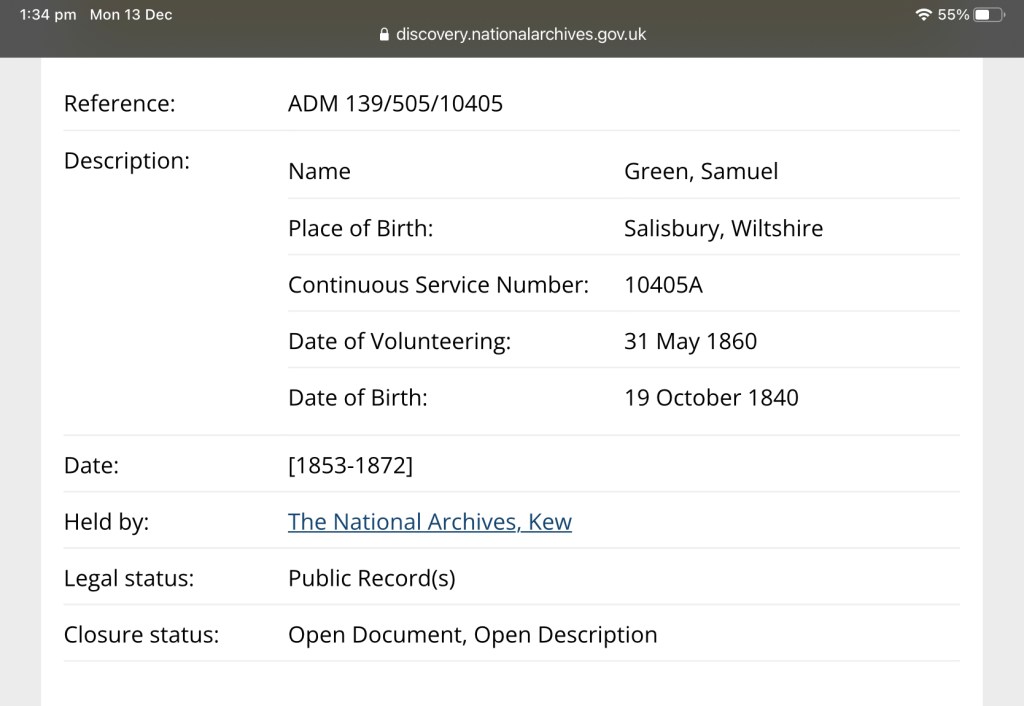

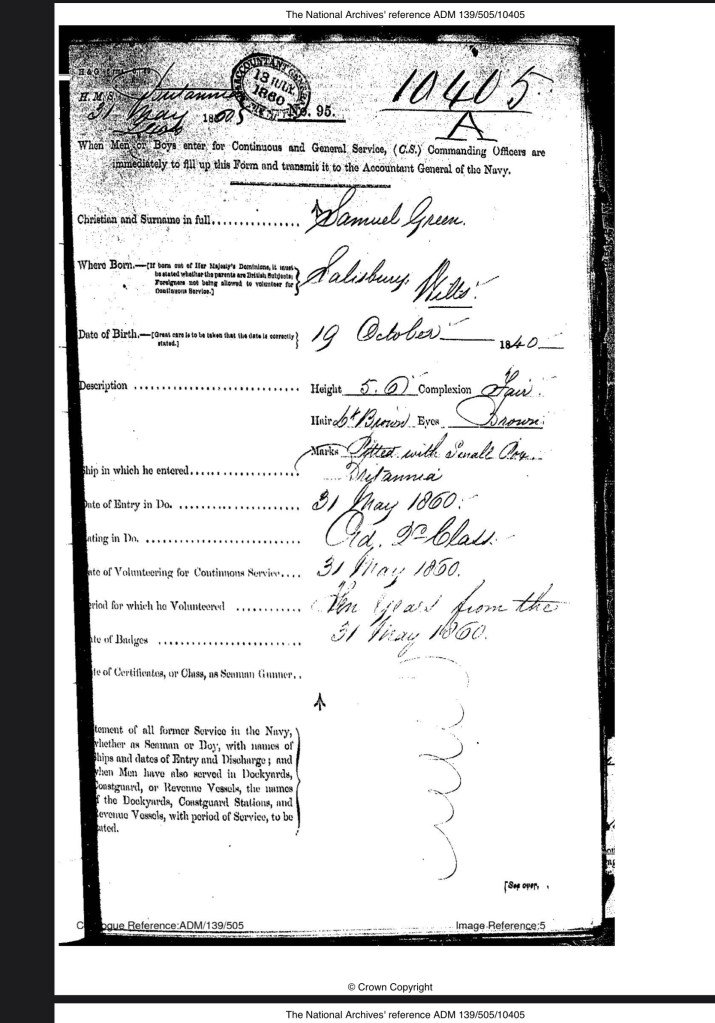

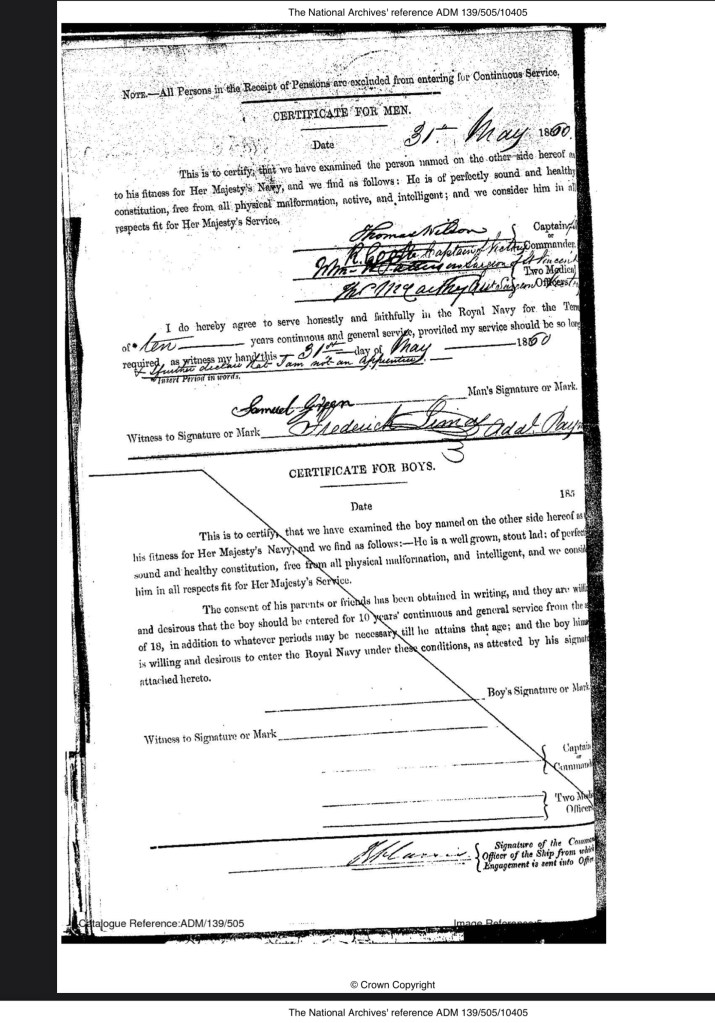

On Thursday the 31st day of May 31, 1860, Samuel Green made a significant decision to enlist in the Royal Navy, signing up for 10 years of service. At the time, he was stationed on the HMS *Britannia*, an 8-gun training ship docked at Portsmouth. His captain during this period was Richard Harris. In a bid to appear older than his true age, Samuel gave a false year of birth, claiming he was born in 1840 rather than the actual year of 1842.

Samuel underwent training on the *Britannia*, where he would have been put through the rigors of naval life, learning the skills required to serve at sea. He was described physically as standing 5’6” tall, with a fair complexion, light brown hair, and brown eyes. Notably, Samuel bore the scars of smallpox on his body, a common ailment of the time that left permanent marks on many who survived it.

As for whether Samuel completed his 10 years of service in the Royal Navy, that remains uncertain. I have yet to uncover whether he fulfilled the full term of his enlistment, but the fact that he joined at such a young age speaks to his sense of adventure and desire to serve his country. His time in the Navy would have undoubtedly shaped him in profound ways, and any further details about his naval career will surely add another layer to the story of Samuel Green’s life.

HMS *Britannia* was a significant vessel in the history of the British Royal Navy, particularly during the mid-19th century. Originally launched in 1820, the ship was a 120-gun first-rate ship of the line, a formidable warship built for combat. However, by the time Samuel Green served aboard it in 1860, the *Britannia* had been repurposed as a training ship for young naval recruits, a role it would come to be most associated with.

As an 8-gun training ship, the *Britannia* was stationed at Portsmouth, one of the Royal Navy’s principal naval ports, where it played a vital part in the training of new sailors. The ship was used to prepare recruits for life at sea by offering practical instruction in naval discipline, sailing, and the various skills required to serve aboard a warship. This transformation from a line-of-battle ship to a training vessel reflected the changing needs of the Navy as it sought to maintain a professional, well-trained fleet in a rapidly evolving world.

The *Britannia* served in this capacity for several decades, training generations of sailors in everything from seamanship to the Royal Navy's regulations and routines. It was often moored in the waters around Portsmouth, providing a stable base where sailors could learn the basics of naval life without the demands of active combat service. As a training ship, it became a rite of passage for many young men who went on to serve in various naval roles across the British Empire.

HMS *Britannia*’s most notable legacy, however, is its role in the training of officers, particularly at the Royal Naval College. From 1864, the *Britannia* was permanently stationed at the college, where it became the official training ship for future officers of the Royal Navy. This association with officer training continued until 1905, when the ship was replaced by a new training establishment. Over the years, many distinguished naval officers passed through the ranks of those trained on the *Britannia*, making it a central institution for developing the next generation of Royal Navy leaders.

The ship's service as a training vessel ended when it was decommissioned in the early 20th century. While no longer a part of the active fleet, HMS *Britannia*’s legacy as a vital institution in the training of sailors and officers continued to influence naval education for many years. The traditions established on the *Britannia* would eventually be carried on in new training ships and schools, further cementing its place in the history of the Royal Navy.

While Samuel Green would have served aboard the *Britannia* during its later years as an 8-gun training vessel, it still stood as a symbol of the Royal Navy’s commitment to preparing young men for the complexities and demands of life at sea. Samuel’s time on the ship would have exposed him to the rigor and discipline that shaped countless sailors throughout history.

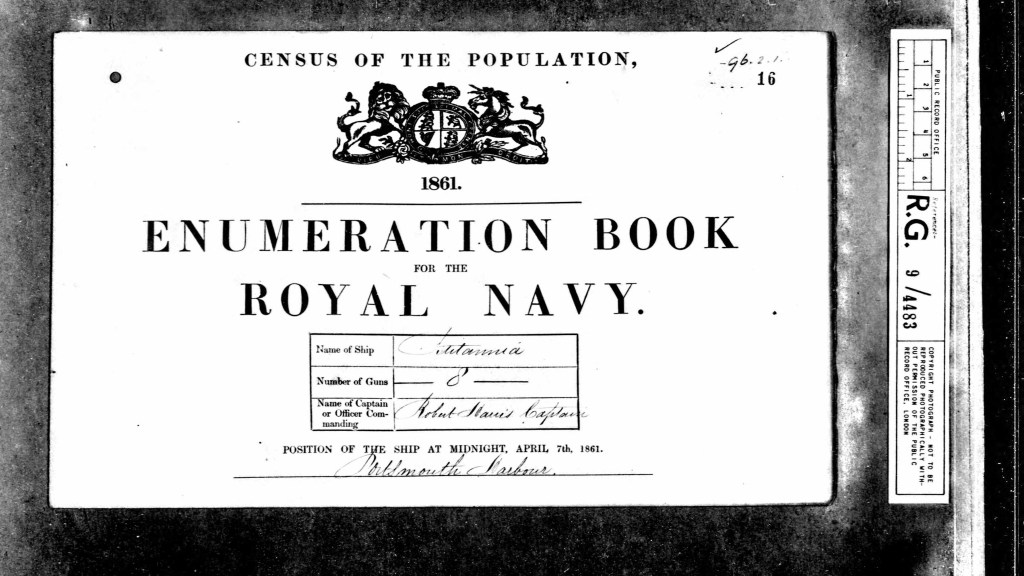

On Sunday, April 7, 1861, the census recorded Samuel aboard the HMS Britannia, an eight-gun Royal Navy training ship anchored in Portsmouth Harbour. At the time, Samuel held the rank of Ordinary Seaman 2nd Class, serving under Captain Robert Harris. This census snapshot captures Samuel at a pivotal stage in his naval career, immersed in the disciplined and demanding life of a Royal Navy seaman.

In the mid-19th century Royal Navy, the rank of Ordinary Seaman signified a sailor with between one and two years of experience at sea. Samuel would have demonstrated enough seamanship and understanding of naval duties to earn this designation from his captain. It was a significant step up from a "landsman," the term used for those with less than a year's experience who were still learning the basics of life at sea. However, Samuel had yet to reach the rank of Able Seaman, a title reserved for sailors with more than two years of experience who were considered fully proficient in their duties and responsibilities.

HMS Britannia herself was a distinguished vessel. As a training ship, she played a crucial role in preparing young men like Samuel for the rigors of naval service, equipping them with the skills and discipline necessary to serve in one of the most powerful navies in the world at that time. Life aboard such a ship would have been a mix of structured training, physical labor, and the camaraderie of a shared mission among the crew.

This moment in Samuel’s life, as documented by the 1861 census, reflects not only his personal journey but also the traditions and hierarchies of the Royal Navy during an era when Britain ruled the seas. His position aboard the HMS Britannia represents his commitment to mastering his duties and advancing within the ranks of naval service.

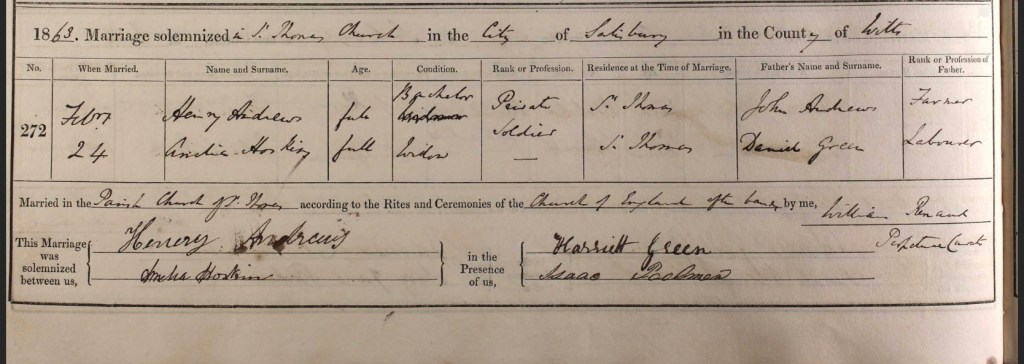

On February 24th, 1863, Amelia Green, a widower, married Henry Andrews, a private soldier and bachelor, at the Church of St. Thomas in Salisbury, Wiltshire, England. In the marriage register, both Amelia and Henry listed their residence as St. Thomas.

When recording their fathers’ names and occupations, Amelia stated that her father, Daniel Green, was a labourer, while Henry recorded his father, James Andrews, as a farmer. Their marriage was witnessed by Harriet Green, who may have been Amelia and Samuel’s mother or possibly their sister, and Isaac Packman. With loved ones by their side, Amelia and Henry began a new chapter of their lives together in the historic Church of St. Thomas.

St. John’s Church in Notting Hill, Middlesex, England, is a striking example of early English Gothic architecture. Built to serve the growing population of the area, the church was completed in 1845 and designed by the architectural team of John Hargrave Stevens and George Alexander. The foundation stone was laid on January 8, 1844, by John Sinclair, who was the Vicar of Kensington and Archdeacon of Middlesex. Less than a year later, on January 29, 1845, the church was consecrated by the Bishop of London, Dr. Charles Blomfield.

The church stands at the summit of Notting Hill, a location that was once part of the central viewing area for the Hippodrome racecourse. Its design is distinguished by its elegant spire, which bears a strong resemblance to that of St. Mary’s Church in Witney, Oxfordshire. Over the years, St. John’s has been a focal point of the community, witnessing the transformation of Notting Hill from a semi-rural area to one of London’s most vibrant and diverse neighborhoods.

In recognition of its architectural and historical significance, St. John’s Church was designated as a Grade II listed building in April 1969. This status ensures its preservation for future generations, safeguarding its Gothic features and historical importance. Today, it continues to serve as a place of worship and community gathering, maintaining its legacy as a cornerstone of Notting Hill’s rich history.

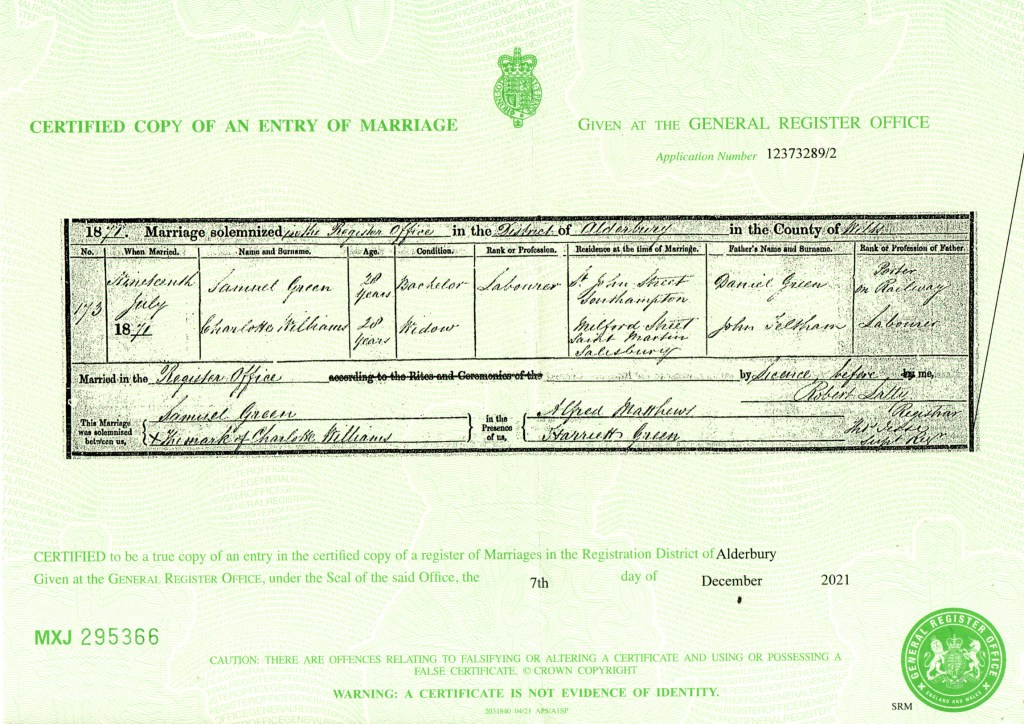

On Thursday, the 13th day of July, 1871, Samuel Green, a 28-year-old labourer, and Charlotte Williams, née Feltham, also 28 years old, were united in marriage at the Register Office in the District of Alderbury, Wiltshire, England. Their union brought together two lives shaped by their unique journeys, Samuel, a bachelor, and Charlotte, a widow.

At the time of their marriage, Samuel was living on St. John Street in Southampton, while Charlotte resided on Milford Street in St. Martin, Salisbury. Despite their physical distance, their paths crossed and intertwined, leading them to this significant day.

The ceremony was witnessed by Alfred Matthews and Harriet Green, whose presence added a layer of warmth and support to the occasion. Charlotte, demonstrating resilience and strength, signed the marriage registry with her mark, an X,, a poignant reminder of the challenges faced by many women of her time who lacked formal education but not determination.

This marriage marked the beginning of a new chapter in Samuel and Charlotte’s lives, uniting their stories and creating a foundation for the family legacy they would go on to build. Their wedding day stands as a testament to their commitment and the promise of a shared future.

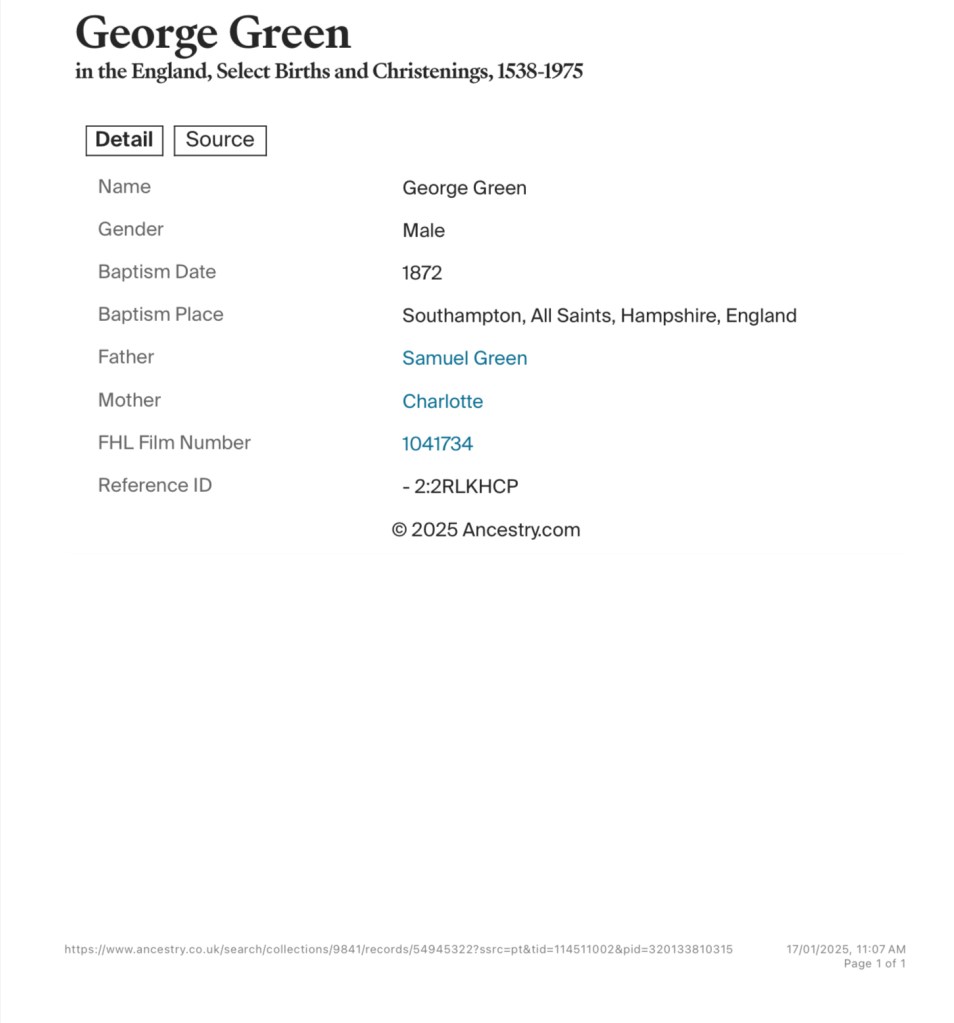

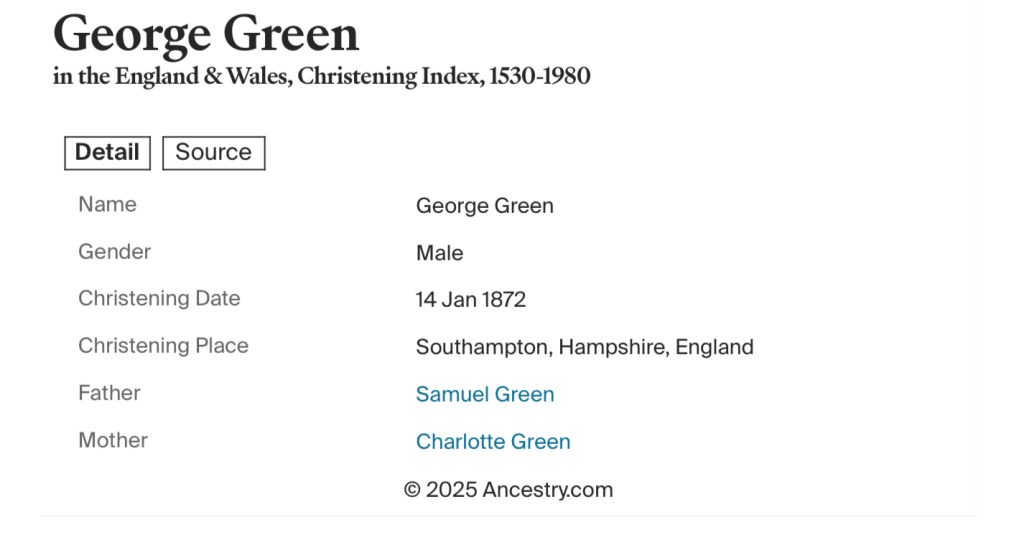

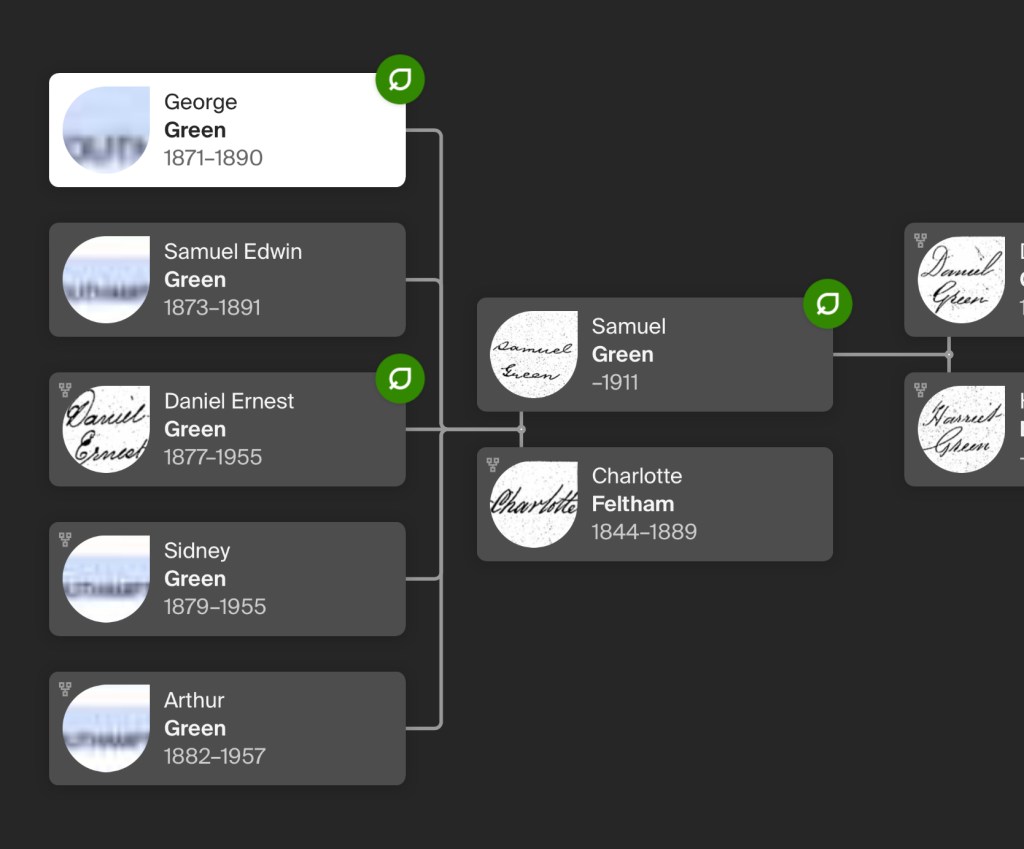

George Green, the beloved son of Samuel and Charlotte Green, came into the world in the depths of winter, Sunday the 26th day of November, 1871, at Number 4, Cross Street, Bell Street, Southampton, Hampshire, England. His birth marked a joyous moment for his family, adding another branch to their growing legacy in this bustling port city.

On a winters day, Wednesday the 27th day of December, 1871, George’s mother, Charlotte, made her way to register his birth, ensuring his arrival was officially recorded. William Cox, the registrar, carefully documented the details, noting that George Green was the son of Samuel Green, a laborer, and Charlotte Green, formerly Williams. This mention of Charlotte's previous married name not only established her identity but also linked George to the broader family history.

When Charlotte signed the registry, she did so with her mark, an X, a simple but heartfelt symbol of her dedication to preserving her son’s place in the records of their time. George’s birth, much like that of his siblings, reflects the resilience and quiet strength of a working-class family in 19th-century Southampton. Through their labours and love, the Greens contributed to the fabric of life in this vibrant and historic city.

Samuel and Charlotte brought their son, George Green, to be baptized on Sunday the 14th day of January, 1872, at All Saints Church in Southampton, Hampshire, England. This ceremony marked an important moment in their family's life, as they stood before the congregation to present their child for baptism, following the traditions of their faith. All Saints Church, a significant place of worship in Southampton, would have witnessed many such occasions, with families gathering to celebrate and commit their children to a life within the church. For Samuel and Charlotte, this day would have been a meaningful and solemn event, ensuring that their son was welcomed into the Christian community.

All Saints Church in Southampton, Hampshire, England, is a historic church with deep roots in the city's religious and architectural history. The church has long served as a place of worship for the people of Southampton and is a key part of the local heritage. Its origins date back to the medieval period, with the church believed to have been established as early as the 12th century.

The present building, however, reflects a combination of styles and periods, particularly from the 19th century. The church was largely rebuilt in the 19th century, especially following the expansion and urban development in Southampton during that era. The restoration, which began in the mid-1800s, was led by prominent architects, who sought to preserve the church's medieval features while incorporating new elements to meet the growing needs of the local population. All Saints Church became an important landmark in the city, standing as a symbol of the faith and resilience of the community.

Architecturally, All Saints Church showcases beautiful elements of Victorian Gothic style, with its soaring spires, pointed arches, and intricate stained-glass windows. The church's interior is just as remarkable, with wooden pews, a grand altar, and memorials that reflect the city's long history. Over the years, the church has undergone several modifications and restorations to preserve its structure, and it remains an active place of worship today.

The church has been a witness to many historical events, including the devastation of Southampton during the Second World War, when many buildings in the city were bombed. Despite the damage to parts of the area, All Saints Church remained a focal point of community life, providing a sense of continuity and stability in difficult times.

Today, All Saints Church stands as a significant architectural and cultural landmark in Southampton. Its long history, beautiful design, and continued role in the community make it a cherished part of the city's heritage.

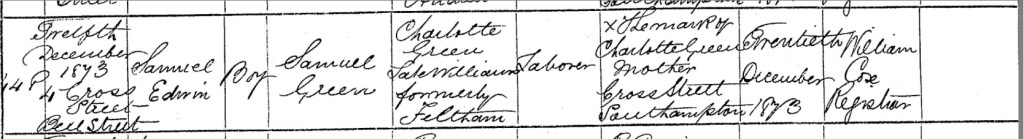

Samuel Edwin Green, the cherished son of Samuel and Charlotte Green, was born on Friday the 5th day of December, 1873, at Number 4, Cross Street, Bell Street, in the heart of Southampton, Hampshire, England. His arrival would have been a moment of joy for his parents, marking another chapter in their growing family’s story.

It was his mother, Charlotte, who took the journey to register his birth just twelve days later, on Wednesday the 17th day of December, 1873. William Cox, the registrar, recorded the details with care, ensuring that this moment in history would not be forgotten. He noted that Samuel Edwin was the son of Samuel Green and Charlotte Green, who had been Charlotte Williams before their marriage and was born Charlotte Feltham. Samuel, his father, was recorded as a laborer, working hard to support his family.

When Charlotte signed the registry, she did so with a simple X, her mark, a humble but significant testament to her role in preserving the story of her son’s early days. Samuel Edwin’s birth not only enriched the Green family but also tied together generations through the enduring strength of their legacy.

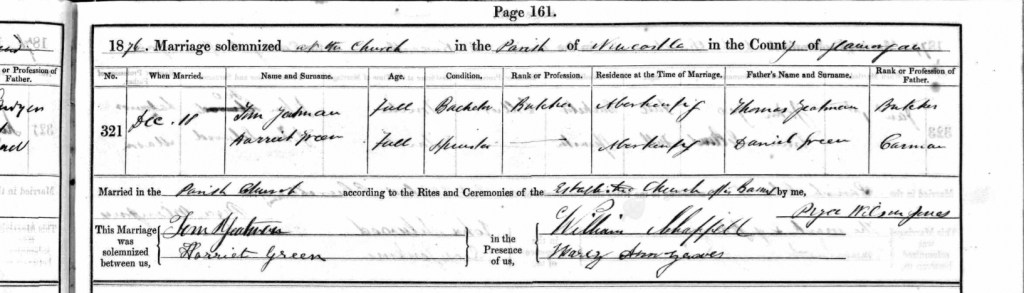

Samuel’s sister, Harriet Green, a spinster, married Tom Yeatman, a bachelor and labourer, on Monday, December 18th, 1876, at St. Illtyd’s, the Parish Church of Newcastle in Newcastle, Glamorganshire, Wales. At the time of their marriage, both Harriet and Tom were of full age and living in Aberkenfig, Wales.

When they recorded their fathers’ names in the marriage register, Harriet listed Daniel Green, a carman, while Tom listed Thomas Yeatman, a butcher. Their wedding was witnessed by William Chappell and Mary Ann Yeaves (or possibly Geaves), who stood beside them on their special day. The ceremony itself was conducted by Pryce Wilson Jones, marking the beginning of their life together as husband and wife.

In the weeks leading up to their wedding, Harriet and Tom’s marriage banns were called on three separate occasions, Sunday the 3rd, 11th, and 17th, days of December, 1876, at St. Illtyd’s Church in Newcastle, Glamorganshire, Wales. The banns confirmed that both Harriet and Tom were residents of the Parish of Newcastle, preparing to enter into marriage. Harriet was listed as a spinster, while Tom was recorded as a bachelor, showing that neither had been married before. As was customary, their union was publicly announced in the church, giving the community an opportunity to raise any lawful objections before their wedding day arrived.

The parish church of Newcastle in Glamorganshire, Wales, is a historic place of worship with deep roots in the region’s past. Dedicated to St. Illtyd, the church stands within the ancient borough of Newcastle, which is now part of Bridgend. Its origins trace back to the medieval period, with architectural elements reflecting centuries of additions and restorations.

The church is believed to have been established in connection with Newcastle Castle, a Norman stronghold built in the 12th century by the Lords of Glamorgan. The castle, constructed under the rule of Robert Fitzhamon or one of his successors, was strategically positioned to control the crossing of the River Ogmore and to protect the Norman territories from Welsh resistance. Given its proximity to the castle, the church likely served both the garrison and the surrounding community.

Architecturally, St. Illtyd’s Church retains a mixture of medieval and later Gothic elements. Its sturdy stone construction, pointed arch windows, and impressive tower are characteristic of churches built during the Norman and later medieval periods. The interior houses historical features such as ancient tombstones, wooden pews, and a chancel that reflects various phases of construction and restoration over the centuries.

Throughout its history, the church has been a focal point for religious and social life in the region. It has witnessed the Reformation, the English Civil War, and the industrial expansion of South Wales. Despite these changes, it has remained an enduring place of worship, adapting to the needs of its parishioners while preserving its historical significance.

Today, St. Illtyd’s Church continues to serve as an important landmark in Bridgend. It attracts visitors not only for religious services but also for its historical and architectural value. The churchyard, with its weathered gravestones, tells the story of generations who lived and worked in the area, adding to the church’s role as a guardian of local heritage.

Samuel and Charlotte’s son, Daniel Ernest Green’s was born on Saturday the 3rd day of March, 1877, at Number 2, Cross Street, Southampton. Daniel’s birth offers a rich glimpse into the fabric of Victorian working-class life in one of England's major port cities. The family’s home in Cross Street placed them within the lively environment of Southampton, where industry, maritime trade, and urban growth shaped daily existence.

Samuel Green, Daniel’s father, was recorded as a laborer, reflecting the physically demanding and often unstable work typical for many men of his class. His role, connected to Southampton’s thriving docks or local industries, would have been crucial in supporting his growing family. Life for families like the Greens would have been characterised by long working hours, limited financial security, and a deep reliance on community.

Charlotte Green, Daniel’s mother, likely shouldered the enormous responsibility of managing the household, raising their children, and maintaining a stable home in a bustling and sometimes harsh urban environment. However, her maiden name was absent from the birth record, a curious omission that introduces an element of mystery into the family narrative. This missing detail highlights a gap often found in historical records, which can pose challenges for genealogical research but also spark deeper exploration into family histories.

Mary Woodley, a neighbor from Cross Court, played a significant role in Daniel’s early story. Her presence at his birth and her subsequent responsibility for registering it on Saturday the 14th day of April, 1877, illustrate the close-knit networks of support among neighbours in working-class communities. Such acts of care and connection were essential, as families navigated the challenges of urban life.

William Cox, the registrar, ensured the official acknowledgment of Daniel’s arrival, reflecting the importance of civil registration, which had become mandatory in England and Wales in 1837. This practice not only documented the demographics of the growing population but also provided a foundation for later historical and genealogical inquiries.

The Greens’ lives were undoubtedly filled with the rhythms of labor, family, and the shared experiences of their community. Daniel’s birth marked a new chapter in their story, one that unfolded amid the broader social and economic currents of Victorian England. For your husband, this piece of family history connects to a lineage rooted in resilience, industriousness, and the enduring human spirit that shaped life in Southampton during the 19th century.

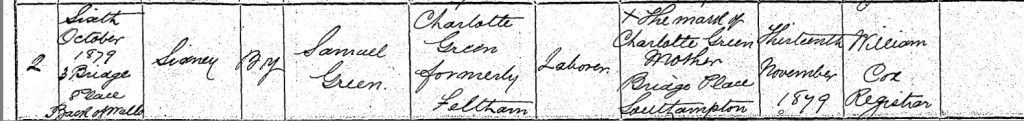

On Monday, the 6th day of October, 1879, Samuel and Charlotte Green celebrated the arrival of their son, Sidney, into their home at Number 3, Bridge Place, Back of Walls, Southampton, Hampshire, England. This joyous occasion marked the birth of another cherished member of the Green family, a younger brother to their sons. Samuel, a diligent laborer, and Charlotte, formerly Feltham, must have been filled with pride and love as they welcomed their newborn son into their lives.

A little over a month later, on Thursday, November 13, 1879, Charlotte took the important step of registering Sidney’s birth. Making her way to the registry office, she provided their address as Bridge Place, Southampton. Despite the challenges of her time, Charlotte ensured her son’s birth was officially recorded, signing the registry with her mark, a humble yet profound X, symbolizing her determination to safeguard Sidney’s place in the family’s history.

Mr. William Cox, the registrar, recorded the details with care, adding Sidney’s name to the official records of Southampton. It’s a touching image to think of Charlotte, a devoted mother, taking this step to secure Sidney’s legacy and honor her role as a loving parent. Her actions reflected the deep commitment she and Samuel shared to building a strong and enduring family amidst the bustling life of Southampton in the late 19th century.

Bridge Place, located "Back of Walls" in Southampton, Hampshire, England, was a residential area situated near the historic Southampton town walls. These medieval walls, constructed primarily between the 13th and 14th centuries, were built to protect the town from potential invaders and played a significant role in Southampton's defense.

The term "Back of Walls" refers to the area immediately adjacent to the interior side of these fortifications. Over time, as the town expanded, residential and commercial structures were erected in this vicinity, integrating the ancient walls into the urban landscape. By the late 19th century, when Sidney Green was born at Number 3, Bridge Place, this area had become a densely populated part of Southampton, characterized by closely built housing and narrow streets.

The proximity to the town walls meant that residents of Bridge Place lived amidst historical structures that had stood for centuries. However, as Southampton modernized, many of these older areas underwent significant changes. Urban development, especially in the 20th century, led to the demolition of some historic sites to make way for new infrastructure. For instance, in the 1930s, parts of the medieval wall and adjoining buildings were demolished to create a bypass for trams.

Today, while much of the original "Back of Walls" area has transformed due to urban development and the aftermath of World War II bombings, efforts have been made to preserve sections of the town walls. These preserved segments serve as a testament to Southampton's rich history and offer insight into the town's medieval past.

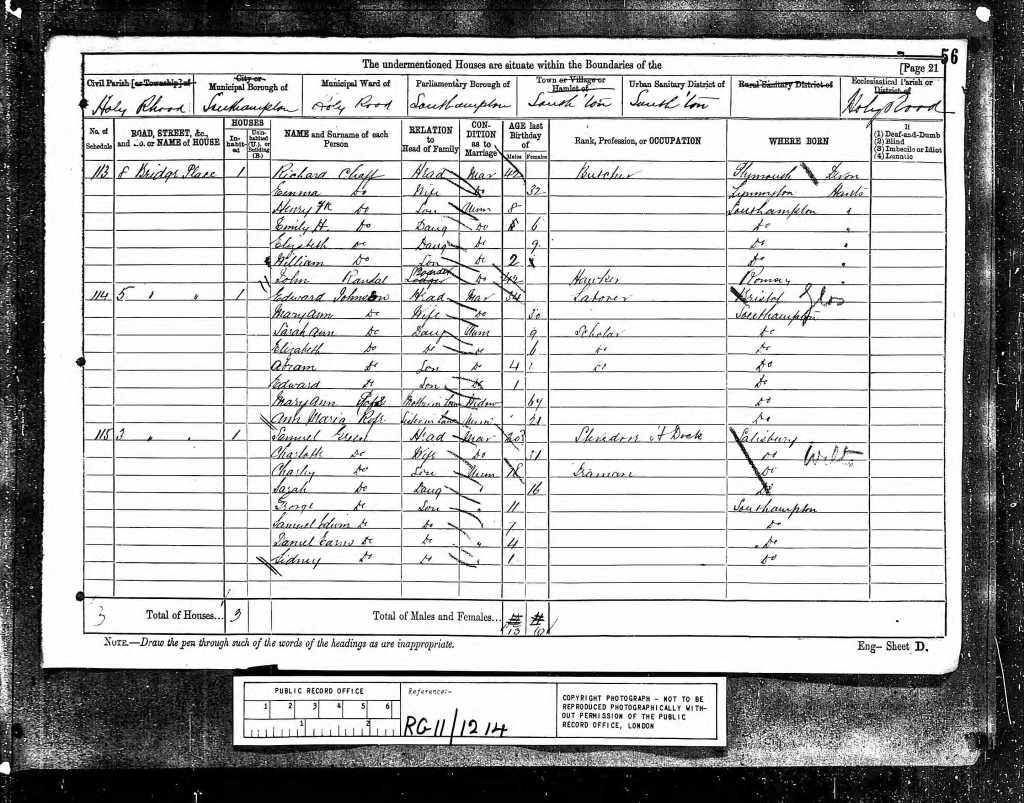

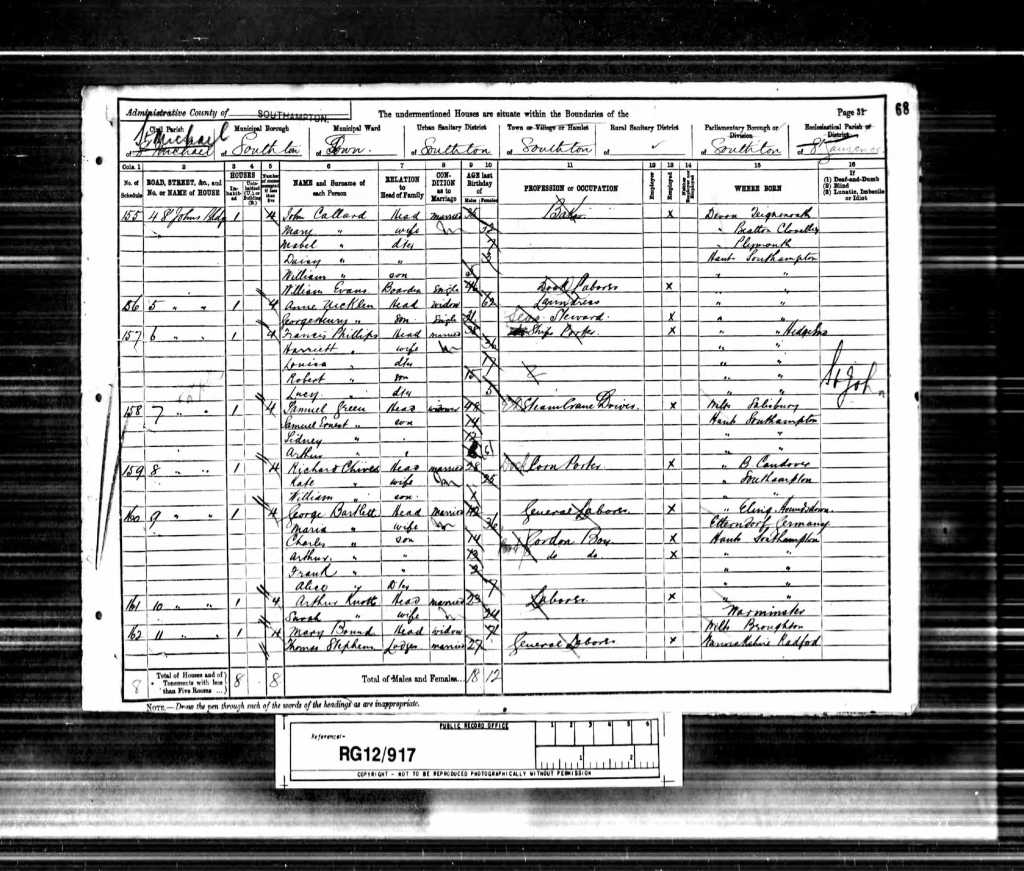

On the evening of Sunday, the 3rd day of April, 1881, Samuel Green and his family resided at Number 3, Bridge Place in Southampton, Hampshire, England. This was a significant period in England's industrial and maritime history, and the family's location and occupations reflect their integration into this dynamic time.

Samuel Green, the head of the household, worked as a stevedore at the docks. A stevedore’s role involved loading and unloading ships, a physically demanding job crucial to the bustling port of Southampton. By the late 19th century, Southampton was a hub of maritime activity, handling cargoes and passengers, including immigrants, luxury goods, and coal shipments. Samuel’s work would have connected him directly to this global network, making him a key figure in the port's operations.

Living with Samuel was his wife, Charlotte, who likely managed the household and cared for their children. The census records list their children as Charles, Sarah, Daniel, Sidney, George, and Samuel Edwin Green. The wide age range among the children indicates a busy family life, with older siblings possibly assisting in household responsibilities or working to contribute to the family income.

Bridge Place, their residence, was located in Southampton, a city undergoing significant urban and industrial development during the late Victorian period. Housing in areas like Bridge Place was typically modest, reflecting the working-class status of families like the Greens. Proximity to the docks was practical for workers such as Samuel, allowing easy access to employment.

The census snapshot of this family on April 3, 1881, reveals much about the era’s social and economic conditions. The Green family's life demonstrates the centrality of port cities like Southampton in Victorian England and highlights the essential roles played by working-class individuals in the broader industrial and maritime framework of the time.

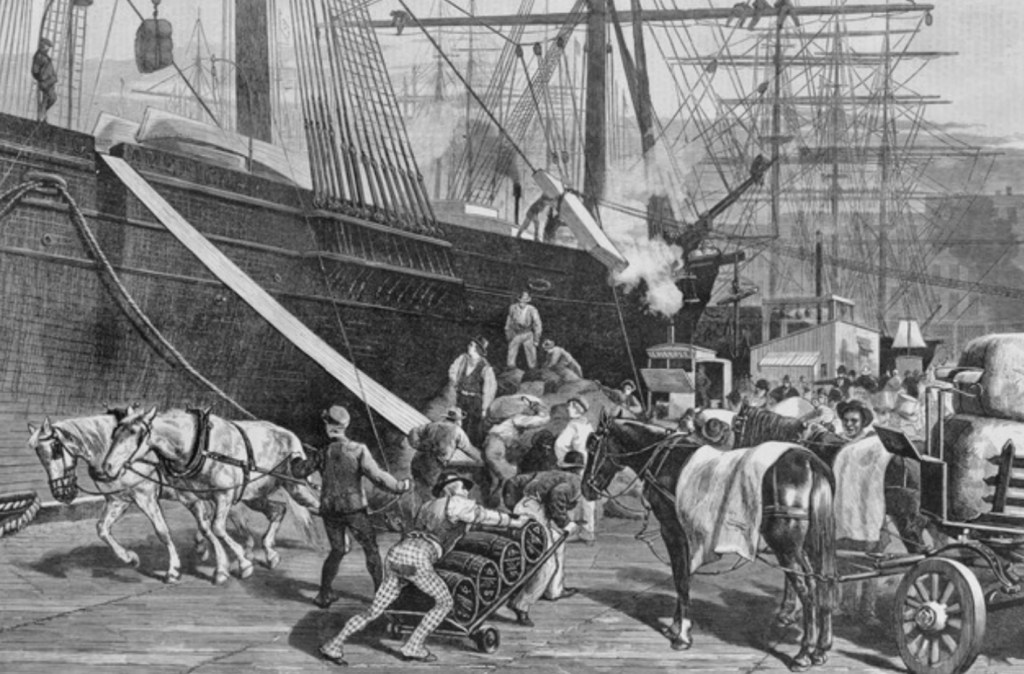

Samuel Green, worked as a stevedore at the bustling docks of Southampton, a port city that was one of the busiest in the country. As a stevedore, Samuel’s role would have been physically demanding and crucial to the smooth operation of the docks. The primary responsibility of a stevedore was to load and unload cargo from ships, often using large cranes, winches, and other heavy manual labor tools. Samuel would have worked long hours, sometimes in challenging weather conditions, moving goods like coal, timber, and textiles that passed through the port.

The work was strenuous and risky, as stevedores had to handle heavy loads while working alongside large, moving ships and the powerful machinery of the docks. The docks themselves were chaotic and noisy, filled with the sounds of steamships, cargo being hoisted, and the calls of sailors and dockworkers. The risk of injury was high, as accidents involving falling cargo or mishandling of equipment could lead to serious harm or even death. Samuel’s job required strength, skill, and endurance, and while it was one of the most important roles in keeping the port functioning, it was not a job that commanded high wages or prestige.

The life of a stevedore in Southampton’s 1881 docks was one of hard physical labor, and while it provided Samuel with a steady job, it also meant long, exhausting days. Families like the Greens, living in working-class neighbourhoods like Bridge Place, often relied on the labor of men like Samuel to sustain their households. The pay was likely modest, and the working conditions tough, yet this was the reality for many in Southampton, where the dockyards were the lifeblood of the town’s economy.

For Samuel, this role would have been the cornerstone of his ability to provide for his family, while also reflecting the broader experience of industrial labor in Victorian England. It was a life of physicality and hard work, but also one filled with pride in contributing to the nation’s commercial and maritime success. However, the toll it took on him, both physically and emotionally, would have been part of the broader struggle faced by the working class in an ever-industrialising society.

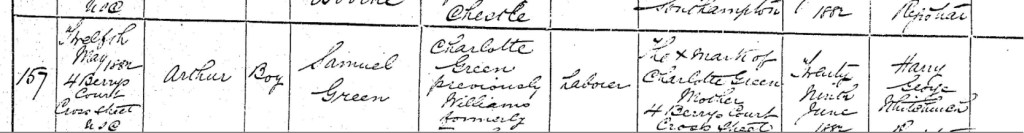

On a spring day, Friday the 12th day of May, 1882, Samuel and Charlotte Green’s son, Arthur, was born at their home, Number 4, Berry’s Court, Cox Street, in Southampton, Hampshire, England. Their family grew with joy as they welcomed this new life into their modest home. A few weeks later, on Thursday the 29th day of June, 1882, Charlotte made the journey to officially register Arthur’s birth in Southampton.

When she stood before the registrar, Mr. Harry George Whitchurch, Charlotte recorded her husband, Samuel Green, as Arthur’s father, noting his occupation as a labourer. She gave her full name as Charlotte Green, formerly Williams, formerly Feltham, and listed their address as Number 4, Berry’s Court, Cox Street. With a steady hand and determination, she marked the registry with an X, her signature and symbol of love and responsibility for her son. It’s heartwarming to imagine Charlotte ensuring that Arthur’s place in their family story was preserved with care and pride.

Berry's Court, located off Cox Street in Southampton, was a residential area that emerged during the 19th century. During this period, Southampton experienced significant urban growth, leading to the development of densely populated neighborhoods comprising courts and narrow streets.

Courts like Berry's Court typically consisted of small, closely built houses arranged around a central courtyard. These areas were often inhabited by working-class families employed in the city's industries and docks. Living conditions in such courts were frequently cramped, with limited access to sanitation and basic amenities, reflecting the broader social and economic challenges of the era.

Cox Street, situated in the Chapel area of Southampton, was part of this urban landscape. The Chapel area, named after the medieval St. Mary's Church (often referred to as "Chapel"), was known for its dense housing and proximity to industrial sites. Over time, as the city modernized and addressed public health concerns, many of these courts, including Berry's Court, were demolished or redeveloped to improve living conditions and accommodate urban planning initiatives.

Today, the landscape of Cox Street and its surroundings has transformed significantly. Modern developments have replaced the old courts, and efforts have been made to preserve the history of these areas through local archives and historical societies. While Berry's Court no longer exists, its history offers insight into Southampton's urban development and the living conditions of its past residents.

For those interested in exploring this history further, local resources such as the Southampton City Archives and the Southampton Heritage Federation provide valuable information and historical records.

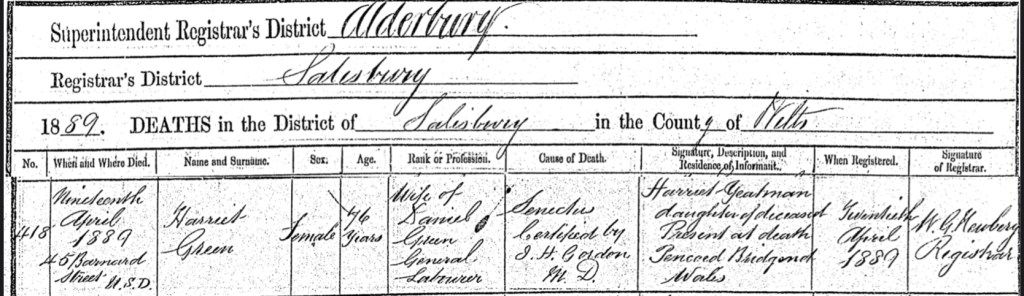

Samuel’s mother, Harriet Green (née Edwards), the wife of Daniel Green, a general labourer, passed away on Friday, the 19th day of April, 1889, at the age of 76. She died at Number 45 Barnard Street, Salisbury, Wiltshire, after a long life. The cause of her death was recorded as "Senectus," meaning she had been worn out by old age, a reflection of the natural decline that comes with the passage of time.

Her daughter, Harriet Yeatman (née Green), was at her side during her final moments, offering the comfort of family during a time of inevitable loss. Harriet registered her mother’s death the following day, Saturday, the 20th day of April, 1889. The responsibility of ensuring her mother’s death was officially recorded would have been an emotional one, especially as it signified the end of an era for their family.

For Samuel, losing his mother was a profound and painful experience. Though he may have been physically distant from Salisbury, the grief he felt would have been immense. Losing a mother is an irreplaceable loss, one that leaves a deep void in the heart, especially for someone who had been such a significant figure in his life. It would have been a heart-wrenching moment for Samuel, as the bond between a mother and son is often one of the most fundamental and enduring relationships.

The sorrow of both Samuel and his sister, Harriet Yeatman, would have been shared across their family. Samuel had already experienced much hardship in his life, and the loss of his mother would have added to the weight he carried. For Harriet, being the one to register her mother’s death, the grief would have been overwhelming, marked by the loss of a lifelong guiding figure. The pain of losing a mother, especially one so central to a family, would resonate deeply, shaping the lives of Samuel, Harriet, and their loved ones for years to come.

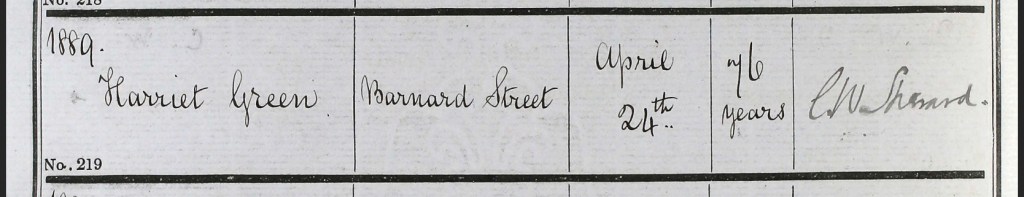

The Green and Edwards families came together in sorrow to lay Harriet Green (née Edwards) to rest on Wednesday, the 24th day of April, 1889, at St. Martin Churchyard, St. Martin’s Church, Salisbury, Wiltshire, England. Harriet’s abode had been recorded as Barnard Street, where she had spent her final years. The churchyard, with its centuries-old gravestones and serene surroundings, would have provided a peaceful and fitting resting place for Harriet, who had spent her life in service to her family and community.

The families, mourning the loss of a beloved matriarch, would have gathered to say their final goodbyes in the quiet of the churchyard, as the weight of grief settled in. For Samuel, the loss of his mother was undoubtedly a deep and painful experience, one that marked a significant moment in his life. Similarly, Harriet Yeatman, his sister, would have been filled with sorrow, as she not only lost her mother but also carried the emotional responsibility of ensuring her mother’s memory was honoured through this final act.

As Harriet Green was laid to rest, surrounded by the names of those who had gone before her, her legacy would live on in the memories of those who loved her. The grief of the Green and Edwards families, though deeply felt in the moment, was a testament to the lasting impact of Harriet's life. Her resting place in St. Martin's Churchyard, a short distance from her home on Barnard Street, would remain a place for her family to remember her for generations to come.

St. Martin’s Church, located in Salisbury, Wiltshire, has a long and rich history, forming an integral part of the city’s religious and social life. The churchyard surrounding it, along with the church itself, reflects the deep historical roots of the area and its development over centuries.

St. Martin’s Church is one of the oldest churches in Salisbury, with its origins likely dating back to the 12th century, though much of the current building was constructed in the 14th and 15th centuries. This was a time of significant development for Salisbury, and St. Martin’s, positioned near the heart of the medieval city, served as a key place of worship and community gathering. The church was originally part of a larger parish that also served parts of the surrounding countryside.

The church is built in the traditional Gothic architectural style, with its pointed arches, tall windows, and intricate stonework. It would have originally served a community of parishioners who lived in and around the area, including those who worked in the burgeoning city center of Salisbury. The church’s proximity to the marketplace and major roads highlights its role as a central institution in the local community, providing spiritual guidance and support to both urban and rural populations.

Over time, the church became closely associated with the surrounding churchyard. The churchyard itself holds many historic graves, some of which mark the final resting places of local citizens who played significant roles in the history of Salisbury. Like many medieval churchyards, it was used for burials over many centuries, and some of the tombstones and memorials found in the yard date back to the 17th and 18th centuries, reflecting the changing customs of burial and memorialization in Salisbury.

The church and its yard have been the focus of various historical studies, revealing important aspects of local life over the centuries. It is said that St. Martin’s Churchyard was used for the burial of not only ordinary citizens but also for some notable figures of the time. Many of the gravestones feature intricate carvings and inscriptions that provide insights into the local families, their social status, and their professions. The churchyard, with its peaceful and reflective atmosphere, still serves as a place for contemplation, where visitors can connect with the past.

The church has seen numerous changes and restorations throughout its history, particularly in the Victorian era when there was a renewed interest in restoring and preserving ancient churches. These restorations have helped ensure that St. Martin’s Church and its churchyard remain an important part of Salisbury’s heritage.

In terms of religious significance, St. Martin’s Church has always been a focal point for Christian worship. Over the centuries, it has held regular services, celebrations of festivals, and has played a central role in baptisms, weddings, and funerals for the local community. As the city of Salisbury expanded and evolved, St. Martin’s remained a vital part of its identity.

Today, St. Martin’s Church and its churchyard stand as quiet reminders of Salisbury’s medieval past. The church is still used for regular worship and community activities, continuing a tradition that has lasted for hundreds of years. It also serves as a historical site, attracting visitors interested in its architecture, history, and the stories encapsulated in the gravestones of its churchyard. The church’s enduring presence in Salisbury highlights the continuity of religious and cultural life in the city, marking it as an important historical landmark that connects the past with the present.

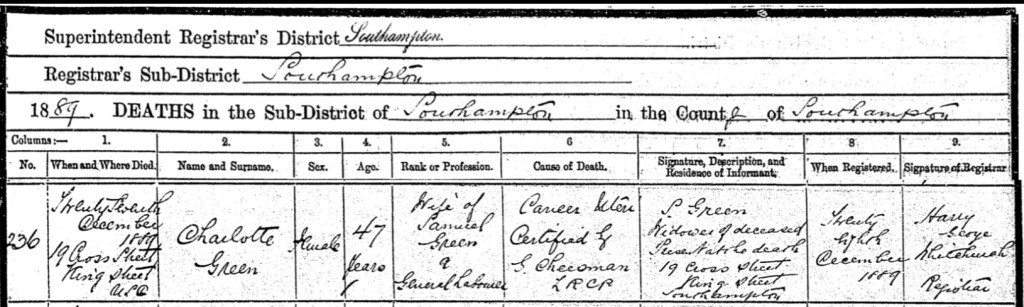

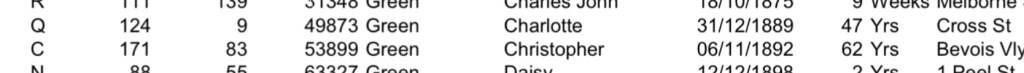

Even more heartbreak followed when, Charlotte Green, late Williams, formerly Feltham, the beloved wife of Samuel Green, a general laborer, tragically passed away on Friday the 27th day of December, 1889, at the age of 47. She died in the comfort of her home at Number 19 Cross Street, King Street, Southampton, Hampshire, England, surrounded by the life she had built with her family. The cause of her death was cancer, a cruel and devastating illness that had taken its toll on her body.

Her devoted husband, Samuel, was present at her side in her final moments, sharing in the sorrow of losing his partner and the mother of their children. Samuel, with a heavy heart, registered her death on Saturday the 28th day of December, 1889. The act of registering her passing would have been a deeply emotional one, marking the end of a chapter in their family’s life and the beginning of an era without Charlotte’s warmth and presence.

Charlotte's death left a significant void in Samuel’s life, and her passing surely had a profound impact on their children. She had been the cornerstone of their home, and her loss was felt deeply by all who knew her. Samuel would go on to carry the weight of her memory as he continued his life without her, a testament to her enduring place in their hearts.

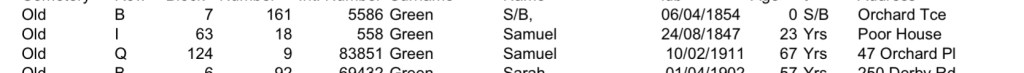

Charlotte Green (née Feltham), Samuel’s beloved wife and soulmate, was laid to rest on Tuesday, December 31, 1889, in the quiet, solemn grounds of Southampton Old Cemetery on Hill Lane. After a life marked by love, sacrifice, and devotion to her family, Charlotte’s passing left a deep void in the hearts of those who knew her. Her final resting place in Row Q, Block 124, is now a peaceful spot, where the interment is recorded as Number 49873.

This final resting place in Southampton Old Cemetery serves as a poignant reminder of Charlotte’s role as the heart of her family, a place where Samuel and their children could return to honor her memory. Though her physical presence was no longer with them, her spirit remained etched in the lives she touched and the love she had given throughout her years.

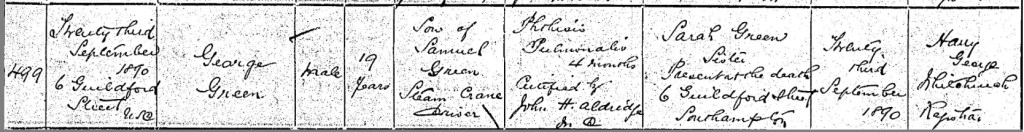

On a somber day, Tuesday, the 23rd day of September, 1890, Samuel and the late Charlotte Green’s 19-year-old son, George, passed away at their home, Number 6, Guildford Street, Southampton, Hampshire, England. George had been battling Phthisis Pulmonalis, a form of tuberculosis, for four months before succumbing to the illness. His death marked the end of a life far too short, filled with hope and potential unfulfilled. Dr. John H. Aldridge, who had cared for him during his illness, certified George's death.

In his final moments, George was surrounded by his sister, Sarah Green, who was at his side, offering love and support during his struggle. She would have witnessed the deep pain of watching her brother deteriorate, her grief compounded by the helplessness of his condition. Later that same day, with a heavy heart and a sense of finality, Sarah went to the registry office to officially record her brother’s passing. She gave the family’s address as Number 6, Guildford Street, marking yet another heartbreaking chapter in their lives. The registrar, Mr. Harry George Whitchurch, who had previously registered the birth of their brother Arthur, once again recorded the family’s sorrowful milestone, this time for the untimely death of their beloved George.

It’s heartbreaking to imagine the sorrow and grief that filled their home that day, as Samuel and his children, already having faced so much loss, had to endure yet another. George's death would have been a cruel blow to a family already weathered by hardship. Yet Sarah’s courage in ensuring her brother’s death was properly documented reflects not only her strength but also the deep love and resilience that held their family together during such a painful and trying time.

With hearts heavy with sorrow, Samuel and his family came together on Saturday the 27th of September, 1890, to bid a tender farewell to George Green. They laid him to rest in the peaceful grounds of Southampton Old Cemetery on Hill Lane, where he found his eternal place in Row Q, Block 124, Number 9. This sacred resting spot held profound significance, as it was where Samuels wife and their children's beloved mother, Charlotte, had been laid to rest just months earlier, on the 31st of December, 1889. George’s interment, marked as Number 50813, united him in eternal slumber with their dear mum, offering a poignant comfort in their shared resting place.

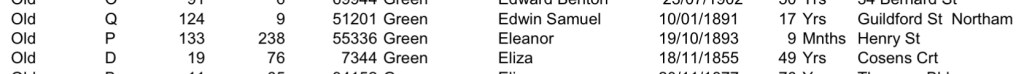

On a winter day, Monday, the 5th day of January, 1891, Samuel and the late Charlotte Green’s 17-year-old son, Samuel Edwin Green, passed away at their family home, Number 6, Guildford Street, Southampton, Hampshire, England. Known as Edwin Samuel in the official records, he was yet another life tragically claimed by Phthisis, a devastating illness that had already struck the Green family, leaving a deep and sorrowful mark on their lives.

Samuel Green, the devoted father and a steam crane driver, was at his son’s side during his final moments. The loss of Edwin, who was so young and full of potential, must have been an overwhelming blow to a family already weighed down by grief. The agony of watching a child succumb to such a cruel illness would have been heart-wrenching for Samuel, who had already endured so much pain.

Just two days later, on Wednesday, the 7th day of January, 1891, Samuel, with a heavy heart, went to the registry office to officially record his son’s death under the name Edwin Samuel. He provided their address as Number 6, Guildford Street, Southampton, to the registrar, Mr. Harry George Whitchurch, who had been part of so many pivotal moments in the Green family’s life, bearing witness to their joys and sorrows alike.

The loss of Edwin Samuel must have weighed heavily on the family, further deepening their collective grief. Yet, Samuel’s unwavering dedication to ensuring his son’s passing was properly recorded reflects not only his enduring love for Edwin but also his sense of responsibility as a father. Despite the profound sorrow he must have felt, Samuel carried out this final act of care for his son, a poignant testament to his love, even in the face of such immense loss.

As one reflects on Samuel’s heartache, the wonder arises as to how he was able to carry on after losing so much. First, his mother, Harriet, then his beloved wife, Charlotte, and now two of his sons, George and Edwin Samuel. The grief must have been utterly overwhelming, a burden no one should ever have to bear. The loss of so many loved ones in such a short span of time would have tested the very limits of his strength, and yet, he continued to live on, holding the pieces of his family together in the face of unimaginable sorrow.

One cannot help but wonder how Samuel found the courage to move forward each day, dealing with the unrelenting weight of loss. His ability to keep going after all this heartache speaks to an inner resilience, a determination to honor the memory of those he loved, even as he faced the daunting task of rebuilding his life without them. Though he surely carried the heavy burden of grief with him every day, Samuel’s enduring love for his family remained at the heart of his every action.

With profound sadness, Samuel and his family laid Edwin Samuel to rest on Saturday, the 10th day of January, 1891, in the serene grounds of Southampton Old Cemetery on Hill Lane. Edwin’s final resting place, in Row Q, Block 124, Number 9, held deep familial significance. This was the same sacred spot where Samuel’s loving wife and the cherished mother to their children, Charlotte, had been lovingly laid to rest on Tuesday the 31st day of December, 1889, and where their dear son, George Green, had been tenderly interred on Wednesday the 27th day of August, 1890.

Edwin’s interment, marked as Number 51201, brought a bittersweet solace to the family, as he joined his mother and brother in eternal peace, forever united in love and memory. The pain of losing Edwin, so young and full of promise, was compounded by the knowledge that he would now rest alongside those he had loved and lost. The quiet of the cemetery, once again filled with the grief of a family, now held the weight of a third loss in just over a year.

For Samuel, the loss of yet another child, following the deaths of George and Edwin, must have been a crushing blow. Yet, the burial in the same plot where Charlotte and George lay provided a sense of continuity, a reminder that though life had taken away so much, there was still love and connection to be found in the shared resting place of those he held most dear. It was a moment of painful solace, knowing that his family, in death, would remain united, their memories entwined forever in that sacred ground.

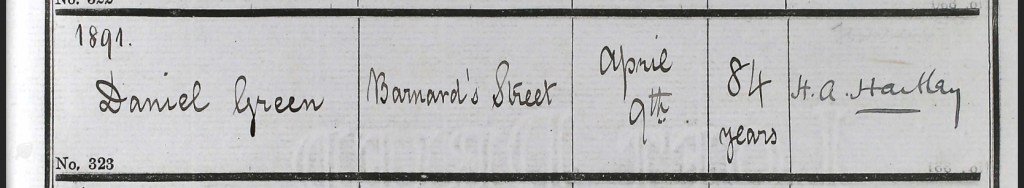

And yet, more death followed when Samuel’s father, Daniel Green, a Railway Labourer, heartbreakingly passed away on Saturday the 4th day of April 1891 at Barnard Street, St Martin, Salisbury, Wiltshire, when he was 86 years old. The cause of death was Senectus, Old Age. Amelia Andrews née Green, his daughter, was present and registered his death on Saturday the 4th day of April 1891.

Daniel’s death marked yet another sorrowful chapter for Samuel, who, having already lost so much of his family, now faced the loss of his father. The grief Samuel must have felt after losing his mother, wife, and two sons in quick succession was compounded by the passing of his father. The weight of the losses, one after another, must have been immeasurable, each death leaving an indelible mark on his heart. Yet, Samuel's strength and resilience in the face of such profound grief continued, despite the heavy toll it undoubtedly took on him.

Samuel’s father, Daniel, was laid to rest on Thursday the 9th day of April 1891 at St Martin’s Churchyard, St Martin’s Church, Church Street, Salisbury, Wiltshire, England. The burial registry shows that Daniel was 84 years old at the time of his death and that his residence was Barnard Street, Salisbury, Wiltshire, England.

Despite the confusion regarding his age, with official records listing him as 86 years old at the time of his passing, the registry entry reflects that Daniel was 84 at the time of his burial. This inconsistency in age may have been a clerical error, though the sorrow and finality of his passing were unmistakable. For Samuel, the loss of his father was another heart-wrenching blow, as he now had to bid farewell to the last remaining link to his childhood and early life. As with the rest of his family, Daniel’s resting place in the peaceful churchyard became a final testament to a life lived and a family now left to mourn.

On Sunday, the 5th day of April, 1891, the census found Samuel Green residing at Number 7, St. John’s Buildings, Southampton, Hampshire, England. Sharing his home were his three sons: Daniel, Arthur, and Sidney. By this time, Samuel was enduring the heavy burden of loss, having been widowed after the passing of his beloved wife, Charlotte, on December 27, 1889. She had succumbed to cancer, leaving Samuel to raise their children alone.

Now 49 years old, Samuel had found work as a Steam Crane Driver, a demanding and highly skilled occupation during the industrial age. Steam cranes, essential tools of the period, were powered by steam engines and represented a marvel of Victorian engineering. They could be fixed in one location or mobile, operating on rail tracks, caterpillar tracks, road wheels, or even mounted on barges for dockside use. These cranes typically featured a vertical boiler positioned at the rear, designed to counterbalance the weight of the jib and its load.

As a Steam Crane Driver, Samuel’s days would have been long and physically challenging, requiring both precision and strength to operate such machinery. Whether loading and unloading ships in Southampton’s bustling port or working at an industrial yard, his role was critical to the city’s commerce and growth.

This snapshot of Samuel’s life in 1891 speaks to his resilience and dedication as he navigated the hardships of widowhood while providing for his family. His work as a Steam Crane Driver not only sustained his household but also connected him to the broader currents of industrial progress in late 19th-century England.

St. John's Buildings was a 19th-century court located off the east side of French Street in Southampton, just south of St. John's burial ground. Set back from the road and facing south, this court was part of the dense network of residential and commercial structures that characterized Southampton during that era.

The proximity of St. John's Buildings to St. John's Church and its burial ground is notable. St. John's Church, situated on the east side of French Street slightly north of Broad Lane, was one of the original post-Conquest churches in the town.

Unfortunately, specific historical details about the residents or the exact nature of the activities within St. John's Buildings are scarce. The area around French Street was known for its mix of residential housing and small businesses, suggesting that St. John's Buildings may have housed working-class families or served as lodging for laborers associated with the nearby docks and industries that fueled Southampton's economy during the 19th century.

There appears to be a lack of readily available photographs or illustrations of St. John's Buildings. This absence is not uncommon for many such structures of that period, especially those that may have been considered utilitarian or unremarkable at the time. The lack of imagery makes it challenging to provide a visual representation of the buildings as they stood.

Over time, as Southampton underwent modernization and redevelopment, many of these older structures, including St. John's Buildings, were likely demolished or significantly altered, leading to their absence in the contemporary cityscape. The transformation of urban areas often results in the loss of such historical buildings, making it difficult to trace their existence beyond written records.

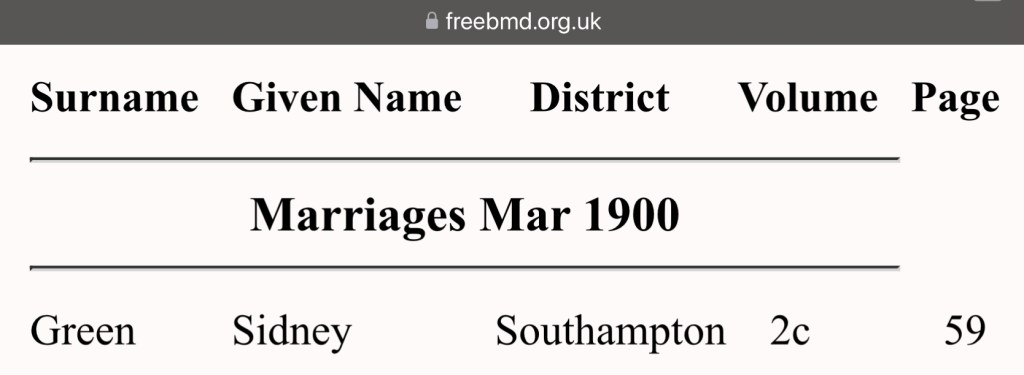

On a winter’s day, Tuesday the 20th Day of February, 1900, in the heart of Southampton, Samuel’s son, Sidney Green and Mary Ann Dymott stood side by side at The Registry Office, ready to begin their journey together as husband and wife. Sidney, a hardworking 21-year-old labourer from Number 25, Union Street, and Mary Ann, also 21, from Number 12, Tower Place, Bargate Street, exchanged vows in the presence of their loved ones.

The ceremony was officiated by A.J. Cheverton, with John A. Hunt overseeing the proceedings, and witnessed by Jane Lockyer and William Keasley. As they signed their names in the marriage register, they carried with them the legacies of their fathers, Samuel Green and Thomas William Dymott, both labourers, men who had shaped their lives and prepared them for this moment.

It was more than just a legal union, it was the beginning of a shared life, filled with hopes, dreams, and the promise of a future built together.

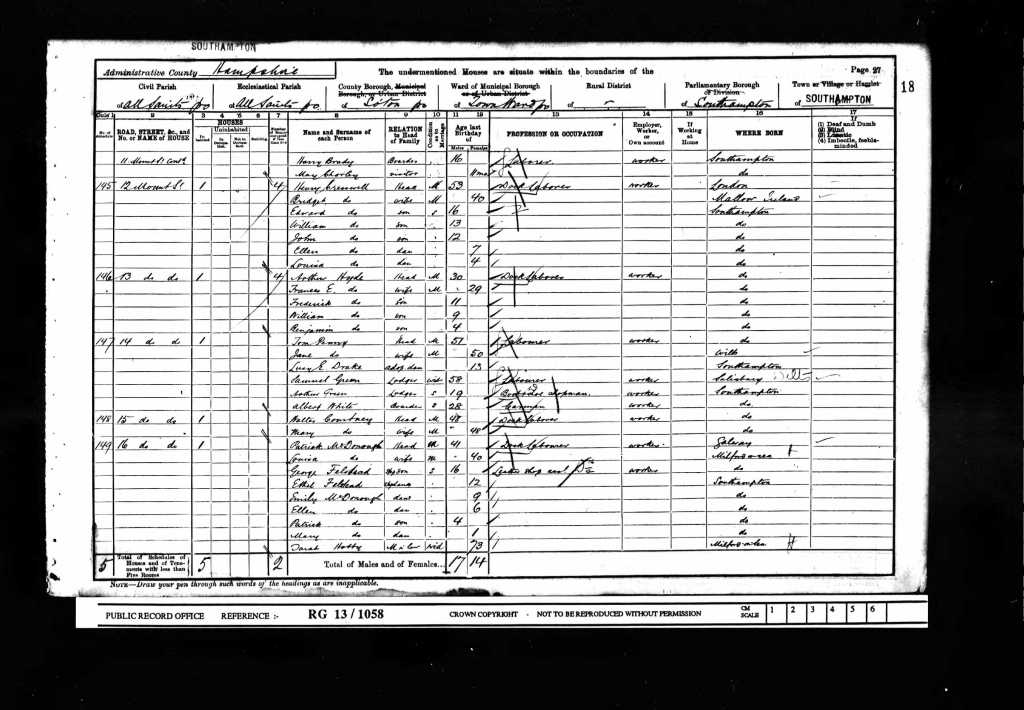

Jumping forward to the evening of Sunday, the 31st day of March, 1901, as the next census was taken, Samuel Green was lodging at Number 14, Mount Street, Southampton, Hampshire, England. He was staying in the home of Tom and Jane Penny, sharing their residence as a lodger. By his side was his son, Arthur Green, now a young man carving out his own path in the world.

Samuel, at this time, was working as a laborer, an occupation that required physical strength and determination. Despite the challenges life had presented, including the loss of his wife, Charlotte, over a decade earlier, Samuel continued to provide for himself and his family through hard work.

Arthur, following a different path, was employed as a shopman in a boot and shoe store. This role reflected the evolving nature of work in Edwardian England, where the growth of retail and service industries was creating new opportunities for employment. Together, Samuel and Arthur formed a small but resilient household, navigating life in Southampton during the early 20th century.

Their lodging with the Pennys likely provided a sense of community and mutual support, reflecting the close-knit living arrangements that were common among working-class families at the time. This moment in their lives, captured by the 1901 census, reveals their enduring strength and adaptability as they moved forward in an ever-changing world.

Mount Street, located in Southampton, Hampshire, England, has a historical significance tied to the city’s development as a maritime and industrial hub. Like many streets in Southampton, Mount Street reflects the evolution of the city from a medieval port to a thriving urban center during the 19th and 20th centuries.

The origins of Mount Street date back to the city’s expansion during the late Georgian and Victorian eras when Southampton experienced significant growth due to its strategic location on the south coast. The street was likely established to accommodate the growing population of workers and their families who moved to the area for employment opportunities in the port and associated industries. Southampton’s docks, which became a cornerstone of the local economy, drove the development of residential neighborhoods like Mount Street to house laborers, tradespeople, and their families.

By the mid-19th century, Mount Street would have been part of a bustling working-class district. The houses were typically modest terraced homes, built to provide affordable accommodations for those employed in the docks or in industries supporting maritime trade. These homes often lacked modern conveniences, but they served as the backbone of Southampton’s urban expansion during the industrial revolution.

The street’s residents were likely involved in a wide range of occupations connected to the port, including dock laborers, sailors, shipbuilders, and warehouse workers. The community was diverse, reflecting the influx of people from various regions seeking work in Southampton. This period also saw the rise of local businesses, shops, and public houses that catered to the daily needs of the Mount Street community.

During the early 20th century, Mount Street, like many parts of Southampton, underwent changes influenced by broader historical events. The First and Second World Wars left their mark on the city, with Southampton playing a critical role as a port for military logistics. The street and its surrounding area would have seen disruptions, including the displacement of residents and damage caused by wartime bombing, particularly during the Blitz of World War II when Southampton suffered significant air raids.

Post-war redevelopment brought changes to Mount Street and its neighboring areas. As part of broader urban renewal efforts in Southampton, older housing stock was replaced or renovated to meet modern standards. The street likely saw changes in its demographics, reflecting shifts in employment patterns and the city’s transition to a more service-oriented economy.

Today, Mount Street represents a blend of historical character and modern urban life. Some of the original architectural features from the 19th century may still be present, offering a glimpse into its past. The street is now part of a city that has embraced its heritage while adapting to contemporary needs. Residents and visitors can still sense the layers of history in the area, from its industrial beginnings to its role in Southampton’s ongoing story as a vibrant, diverse city.

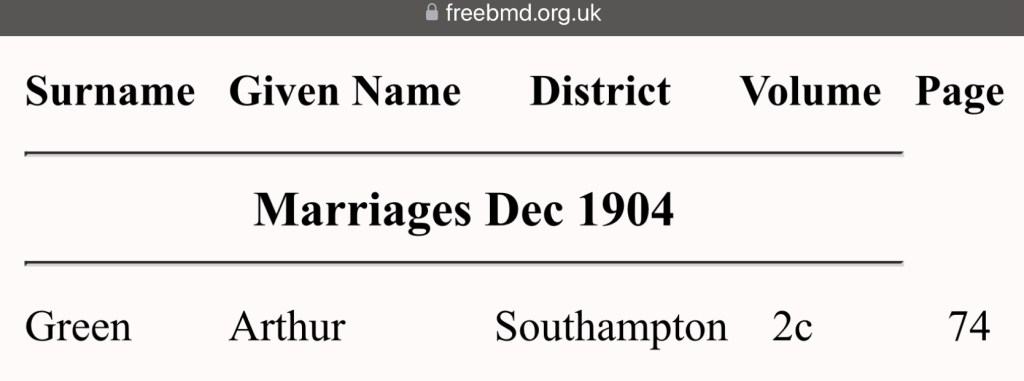

Arthur Green, the son of Samuel, married Jessie Hobby between October and December of 1904 in the Southampton district of Hampshire, England. If you’d like to obtain a copy of their marriage certificate, you can do so using the following details: Marriages, December 1904, Green, Arthur, Southampton, Volume 2c, Page 74.

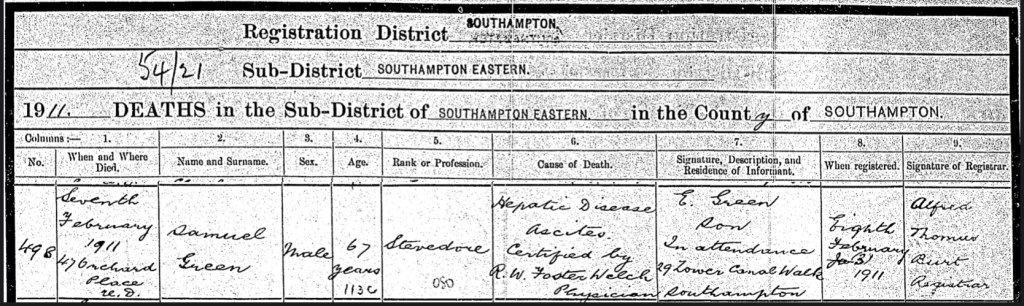

Samuel Green’s life story, filled with resilience and hard work, reached its end on Tuesday the 7th day of February, 1911, at the age of 67. He passed away at Number 47, Orchard Place, Southampton, Hampshire, England. His death was attributed to Ascites, a buildup of fluid in the abdomen, and Hepatic Disease, likely caused by liver damage due to excessive alcohol consumption, obesity, or an undiagnosed hepatitis infection. It was a tragic culmination of a life lived through the hardships and challenges of his time.

At his side during his final moments was his son, Daniel Ernest Green, known as E. Green on the death certificate. Daniel not only bore witness to his father’s passing but also took on the responsibility of registering Samuel’s death the very next day, Wednesday the 8th day of February, 1911. This act reflects the deep bond between father and son, as Daniel ensured Samuel’s passing was formally recorded and his legacy preserved.

Samuel’s occupation at the time of his death was listed as a Stevedore, a dockworker responsible for loading and unloading ships. It was physically demanding labor, symbolic of the industrious and determined life Samuel led to provide for his family. His role as a stevedore tied him to Southampton’s bustling port, a key hub of commerce and industry during his lifetime.

Samuel’s journey, from his early days as a young seaman aboard the HMS Britannia to his later years as a labourer and stevedore, speaks to his enduring strength and perseverance. Though his story ends with sorrow, his legacy lives on through his children and the family he worked so hard to support. Samuel’s life was a testament to the resilience of the working class in 19th- and early 20th-century England, a life of challenges met with unwavering determination.

Orchard Place in Southampton is a street with a rich history, reflecting the city's development over the centuries. Developed in the 18th century, Orchard Place extends from Orchard Lane, a significant thoroughfare that dates back to medieval times. Orchard Lane was originally known as Newtown Street and served as the main artery of the suburb of Newtown, situated to the east of the walled town.

In the early 19th century, houses along Orchard Place were constructed, contributing to the area's residential character. Notably, numbers 25 to 36 on the west side of Orchard Place were built by the White's Trust. These properties were later sold off in the 1920s and 1930s.

The street also hosted various businesses. For instance, premises at 23 and 24 Orchard Place served as the main offices for William A. Fussell, a builder, decorator, and plumber established in 1860.

Archaeological findings have shed light on the area's past. A 19th-century brick wall was discovered, believed to be associated with Orchard House, a large residence built in 1818. By 1868, this house had been replaced by terraced houses, indicating the area's evolution from grand homes to more densely packed housing.

Today, Orchard Place stands as a testament to Southampton's layered history, from its medieval roots to its 19th-century developments, reflecting the city's growth and transformation over time.

Samuel Green's story came to its final chapter on February 10, 1911, when his family and loved ones gathered to lay him to rest.

He was interred at the Southampton Old Cemetery on Hill Lane, Southampton, a place steeped in history and serenity.

Samuel’s grave is located in Row Q, Block 124, Number 9, marked by the Interment Number 83851.

In a poignant and fitting tribute to their bond, Samuel was buried alongside his beloved wife, Charlotte, who had passed away more than two decades earlier. Their shared resting place serves as a testament to the enduring connection between them, even in death.

The funeral would have been a somber occasion, filled with the presence of family and friends who had witnessed Samuel’s life of hard work, resilience, and love for his family.

The Southampton Old Cemetery, with its quiet paths and historic gravestones, provides a peaceful resting place for Samuel and Charlotte, a place where their memory lives on amidst the city they called home.

Their grave stands not only as a marker of their lives but as a reminder of the strength and dedication they embodied, leaving behind a legacy carried forward by their children and descendants.

As I sit here reflecting on the incredible journey that has been "The Life of Samuel Green, 1842-1911, Through Documentation," I am struck by the profound weight of his story and the legacy he left behind. Samuel Green was more than just a name in the records or a figure in the family tree—he was a man who lived, loved, struggled, and persevered through the triumphs and tragedies of life. His story, pieced together through fragments of documentation, reveals not just the life of one man, but the heartbeat of a family.