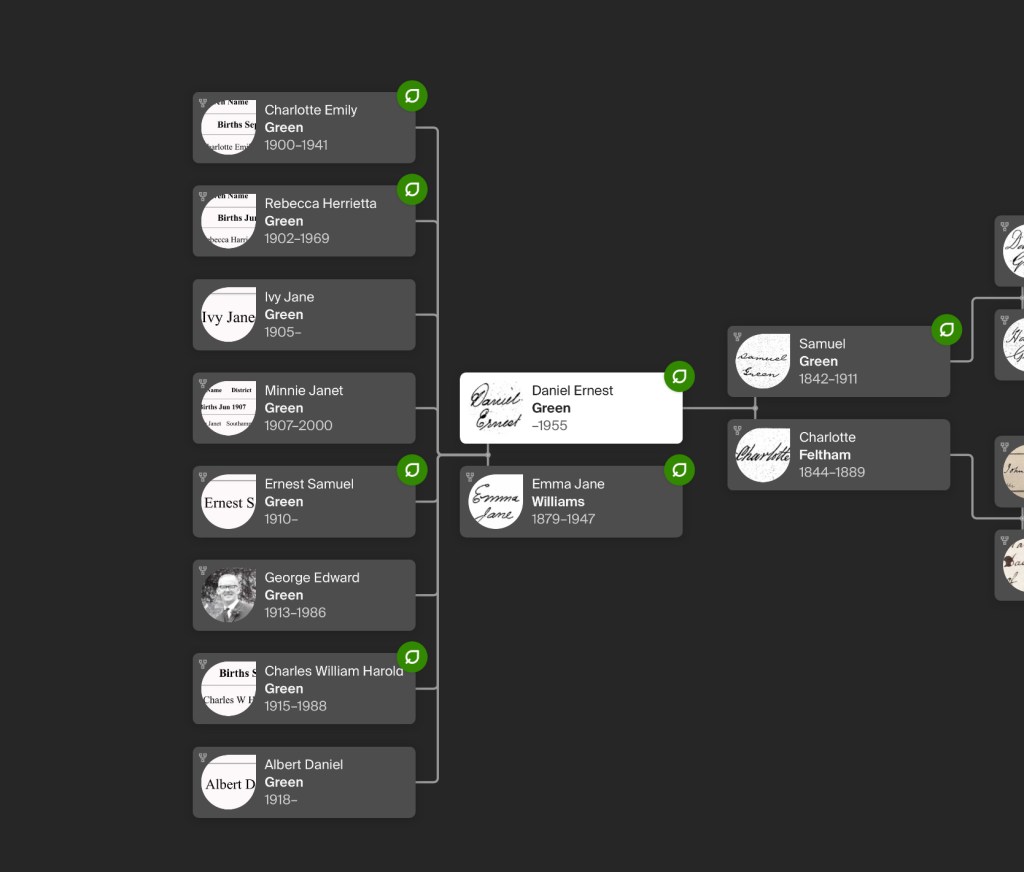

Uncovering the life story of my husband’s great-grandfather, Daniel Ernest Green (1877–1955), has been a journey that brought history to life in the most personal and profound way. It is more than just tracing names and dates on a family tree, it’s about piecing together the fragments of a life once lived, breathing life into the memories of those who came before us. Through meticulous research and the discovery of historical documentation, we’ve been able to follow Daniel’s footsteps, weaving a narrative that connects the past to the present and enriches our understanding of who we are today.

The importance of researching one’s ancestry cannot be overstated. It allows us to uncover stories that might otherwise fade into obscurity, preserving the legacy of our ancestors and their place in the broader tapestry of history. Records are the threads that stitch these stories together. In the United Kingdom, they date back centuries, offering a wealth of information for those willing to explore. From civil registration records, which began in 1837 and include births, marriages, and deaths, to census records dating back to 1841, these documents offer a snapshot of family life at various points in time. Parish records, some of which date back to the 16th century, contain baptisms, marriages, and burials, revealing the rhythm of life in communities long gone.

Beyond these, there are wills, probate records, military service documents, immigration and emigration records, and even trade directories, each offering unique insights into the lives of our forebears. For Daniel, it was these very records, birth certificates, marriage registries, census entries, and even historical accounts of Southampton’s past, that allowed us to reconstruct his life, from his humble beginnings in Hampshire to the man he became.

Researching Daniel’s life has been more than a historical exercise; it has been an emotional journey. It has deepened our connection to our family’s roots, brought us closer to our shared history, and reminded us of the resilience and humanity of those who walked this earth before us. By delving into these records, we honor their memory and ensure that their stories are not forgotten but celebrated as part of the enduring story of our family.

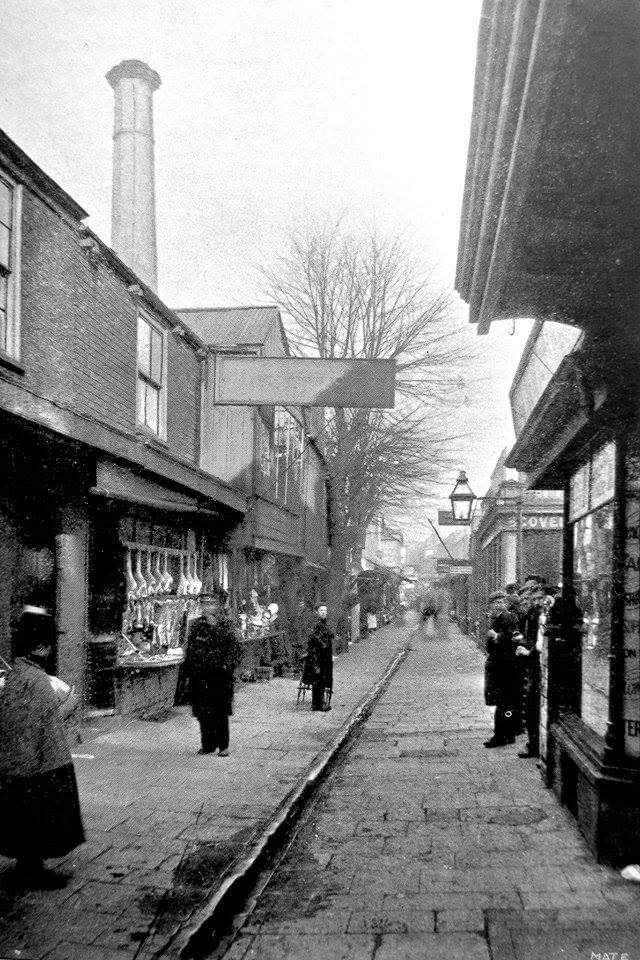

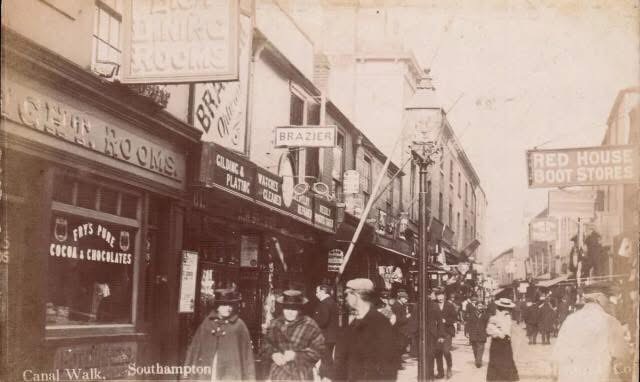

Welcome back to the year 1877, Southampton, Hampshire, England. Life in this bustling port town was a blend of industrial progress, maritime activity, and the challenges of Victorian society. Queen Victoria, in the 40th year of her reign, was the monarch, embodying the strength and stability of the British Empire, which at that time was the most powerful in the world. The Prime Minister, Benjamin Disraeli, led the government under a Conservative majority, while Parliament grappled with the challenges of a rapidly industrializing nation, including public health, housing, and the widening gap between social classes.

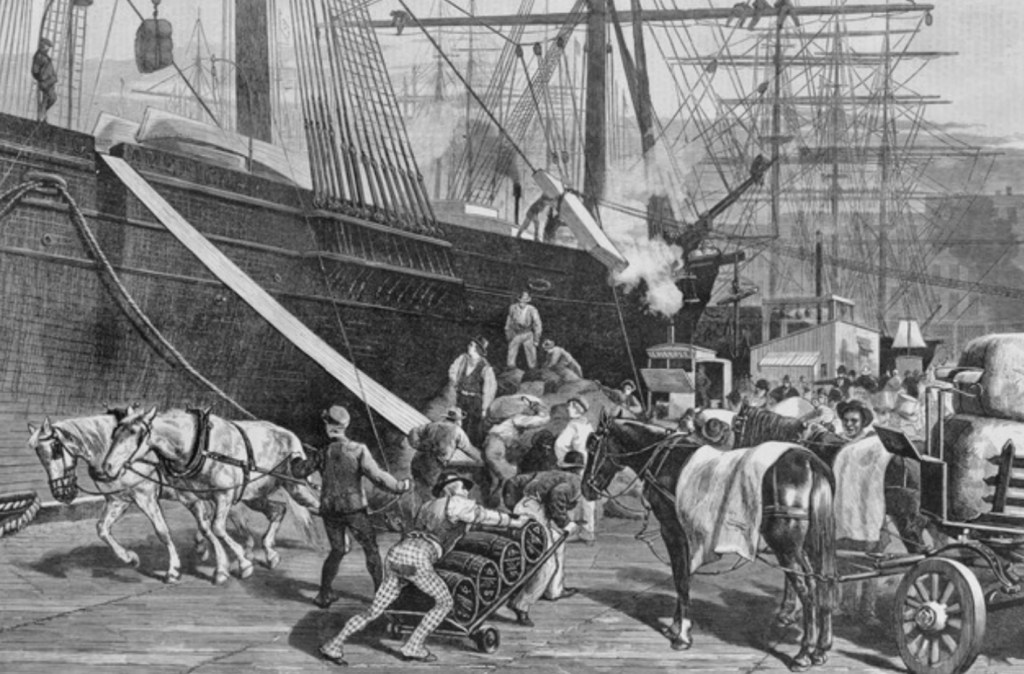

Southampton in 1877 was a town teeming with life. Its docks were a hub of global trade, with ships arriving and departing, carrying goods, people, and stories from across the empire. The town’s population was growing, driven by employment opportunities in shipping, engineering, and the service industries that supported its maritime economy. However, this industrial growth was not without its challenges, as the working and poorer classes often bore the brunt of the era’s hardships.

The social hierarchy in 1877 was rigid. The upper class, including aristocrats and wealthy industrialists, lived in grand homes, enjoying opulent lifestyles and the latest fashions: bustled dresses and tailored suits that reflected their status. The middle class, comprising merchants, professionals, and skilled tradespeople, sought respectability and comfort, while the working class and the poor faced a harsher reality. Many worked long hours in factories, docks, or domestic service for meager wages, often living in cramped and unsanitary housing.

Victorian fashion mirrored the strict social norms of the time. For women, tightly corseted dresses with high necklines and voluminous skirts were the norm, while men donned waistcoats, cravats, and frock coats. For the working classes, practicality prevailed, with simpler, more durable clothing suited to the demands of labor.

Transportation in Southampton was transforming. The railway connected the town to London and beyond, fostering trade and travel, while horse-drawn trams and carriages navigated its bustling streets. Steamships dominated the docks, and Southampton’s reputation as the “Gateway to the Empire” continued to grow.

Energy and heating were still primitive by modern standards. Coal was king, powering steam engines and heating homes, though it filled the air with soot and smoke. Gas lighting illuminated streets and wealthier homes, while poorer households relied on candles or oil lamps. Central heating was nonexistent; fireplaces provided warmth in homes, but only for those who could afford coal.

Sanitation was improving but remained a challenge, especially in crowded working-class areas. Efforts to provide clean water and sewage systems were underway, but many still relied on wells and outdoor privies. Outbreaks of diseases like cholera and typhoid were not uncommon, particularly in densely populated neighborhoods.

Food in 1877 varied widely depending on social class. The wealthy enjoyed elaborate meals with exotic ingredients imported through Southampton’s docks, while the poor subsisted on bread, potatoes, and whatever seasonal produce was affordable. For many, hunger was a daily concern.

Entertainment reflected both the rigidity and the vitality of Victorian society. Theaters, music halls, and public houses were popular, offering escapism and community. In Southampton, the docks themselves were a source of fascination, with crowds gathering to watch ships and sailors. For those who could afford it, books and periodicals were enjoying a golden age, as literacy rates improved.

The environment of Southampton in 1877 was shaped by its maritime identity. The air was thick with the smells of coal smoke and saltwater, and the sounds of ship horns and labor filled the air. The town’s green spaces were limited, and industrialization often came at the expense of the natural environment.

For those living and working in Southampton, life depended heavily on social class. The wealthy enjoyed comfort and stability, while the working class faced long hours of grueling labor. Dockworkers loaded and unloaded cargo, often in hazardous conditions. Women and children contributed to household income through domestic service or work in factories, where regulations were minimal.

Historical events in 1877 included continued colonial expansion and the rise of industrial Britain. The Southampton docks played a crucial role in the empire’s trade networks, bringing the town into close contact with the broader world. Locally, the town’s growth reflected both the promise and the perils of the Victorian age.

Life in Southampton in 1877 was both vibrant and challenging, shaped by the push and pull of industrial progress, maritime trade, and Victorian values. It was a time of innovation and struggle, where every ship that left the docks carried not only goods but also the hopes and dreams of a town poised between the old and the new.

More importantly to us, Daniel Ernest Green, my husband’s great-grandmother, came into the world on Saturday, the 3rd day of March, 1877, at Number 2, Cross Street, Southampton, Hampshire, England. He was born to Charlotte Green nee Feltham,, and Samuel Green, a labourer. Their lives must have been filled with the hum of daily struggles and simple joys in the bustling heart of Southampton.

A neighbour, Mary Woodley of Cross Court, Southampton, played an important role in this milestone, as she was present for Daniel’s birth and later took responsibility for registering it on Saturday the 14th day of April, 1877. The details of the birth were recorded by William Cox, the Registrar, ensuring Daniel’s arrival was officially acknowledged. However, one detail was notably absent from the birth certificate, the maiden name of his mother, Charlotte Green, leaving a small mystery in the story of their family history.

Amid the backdrop of a bustling Victorian Southampton, Daniel Ernest Green’s arrival marked the beginning of a life intertwined with the rhythms of a growing port town. The year 1877 was a time of great change and industrial growth, and Southampton’s docks were a hub of activity, connecting England to the farthest corners of the empire. For Daniel’s parents, Samuel and Charlotte, life was likely shaped by the opportunities and hardships of a working-class existence. Samuel’s role as a labourer placed him among the countless men whose toil fuelled the town’s economy, while Charlotte’s responsibilities at home reflected the unacknowledged but essential labor of women during this era.

The small but significant role of Mary Woodley in registering Daniel’s birth highlights the close-knit community that often existed in working-class neighborhoods. Neighbors like Mary would have been vital in supporting families through the milestones of life, from births to marriages to losses.

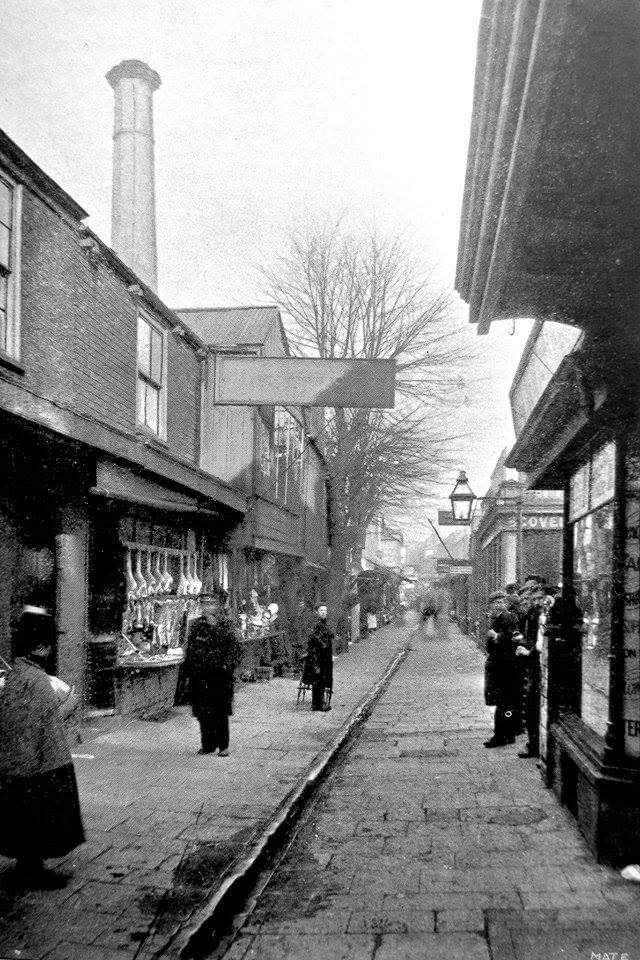

Daniel’s childhood unfolded in a town shaped by contrasts. On one hand, Southampton was a place of industry and progress, with its docks bustling with steamships and rail connections linking it to the wider world. On the other hand, it was a town where the challenges of Victorian life, poor sanitation, cramped housing, and the struggle to make ends meet, were part of everyday existence for families like the Greens. In their modest home on Cross Street, the sounds of passing carts and dockworkers would have been ever-present, mingling with the laughter and cries of children in the tightly packed streets.

Through the documents left behind, birth certificates, census records, and marriage registries, a fuller picture of Daniel’s life begins to emerge. These records are not just pieces of paper, they are windows into a world long past, preserving the story of a family navigating the challenges and opportunities of 19th-century Southampton. husband’s family.

In Victorian Southampton, there were three streets named Cross Street. One of these ran from North Front to Johnson Street in the Kingsland area, dating back to at least 1846.

The Kingsland district, where this Cross Street was located, was a working-class neighborhood. Residents typically lived in modest terraced houses, often sharing facilities and living in close quarters. The area was characterised by narrow streets and a dense population, reflecting the rapid urbanization of Southampton during the 19th century.

Unfortunately, detailed historical records specific to Number 2 Cross Street are scarce. Given the commonality of the street name and the lack of comprehensive documentation, it's challenging to provide a precise history of this particular address. Additionally, photographic evidence from that era is limited, and no known photographs of Number, 2 Cross Street have surfaced.

It's worth noting that many parts of Southampton, including areas like Kingsland, underwent significant changes during the 20th century. The city suffered extensive damage during World War II bombings, leading to the destruction of numerous historic buildings and subsequent redevelopment. As a result, many 19th-century structures no longer exist, and the urban landscape has transformed considerably since Daniel Ernest Green's time.

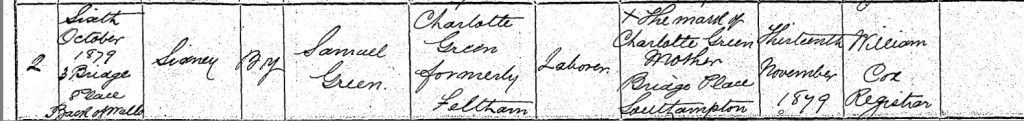

On Monday, the 6th day of October, 1879, Samuel and Charlotte Green welcomed their son, Daniels brother, Sidney, into the world at their home at Number 3, Bridge Place, Back of Walls, in Southampton, Hampshire, England. Samuel, a hardworking labourer, and Charlotte, née Feltham, were surely overjoyed to hold their little boy in their arms. A little over a month later, on Thursday, the 13th day of November, 1879, Charlotte made her way to register Sidney’s birth. At the registry office, she gave their address as Bridge Place, Southampton, and signed the official record with her mark, a simple X. Mr. William Cox, the registrar, recorded the details. It’s touching to think of that moment, Charlotte, ensuring her son’s arrival was formally recognised, a testament to her care and love for her growing family.

Bridge Place, located "Back of Walls" in Southampton, Hampshire, England, was a residential area situated near the historic Southampton town walls. These medieval walls, constructed primarily between the 13th and 14th centuries, were built to protect the town from potential invaders and played a significant role in Southampton's defense.

The term "Back of Walls" refers to the area immediately adjacent to the interior side of these fortifications. Over time, as the town expanded, residential and commercial structures were erected in this vicinity, integrating the ancient walls into the urban landscape. By the late 19th century, when Sidney Green was born at Number 3, Bridge Place, this area had become a densely populated part of Southampton, characterized by closely built housing and narrow streets.

The proximity to the town walls meant that residents of Bridge Place lived amidst historical structures that had stood for centuries. However, as Southampton modernized, many of these older areas underwent significant changes. Urban development, especially in the 20th century, led to the demolition of some historic sites to make way for new infrastructure. For instance, in the 1930s, parts of the medieval wall and adjoining buildings were demolished to create a bypass for trams.

Today, while much of the original "Back of Walls" area has transformed due to urban development and the aftermath of World War II bombings, efforts have been made to preserve sections of the town walls. These preserved segments serve as a testament to Southampton's rich history and offer insight into the town's medieval past.

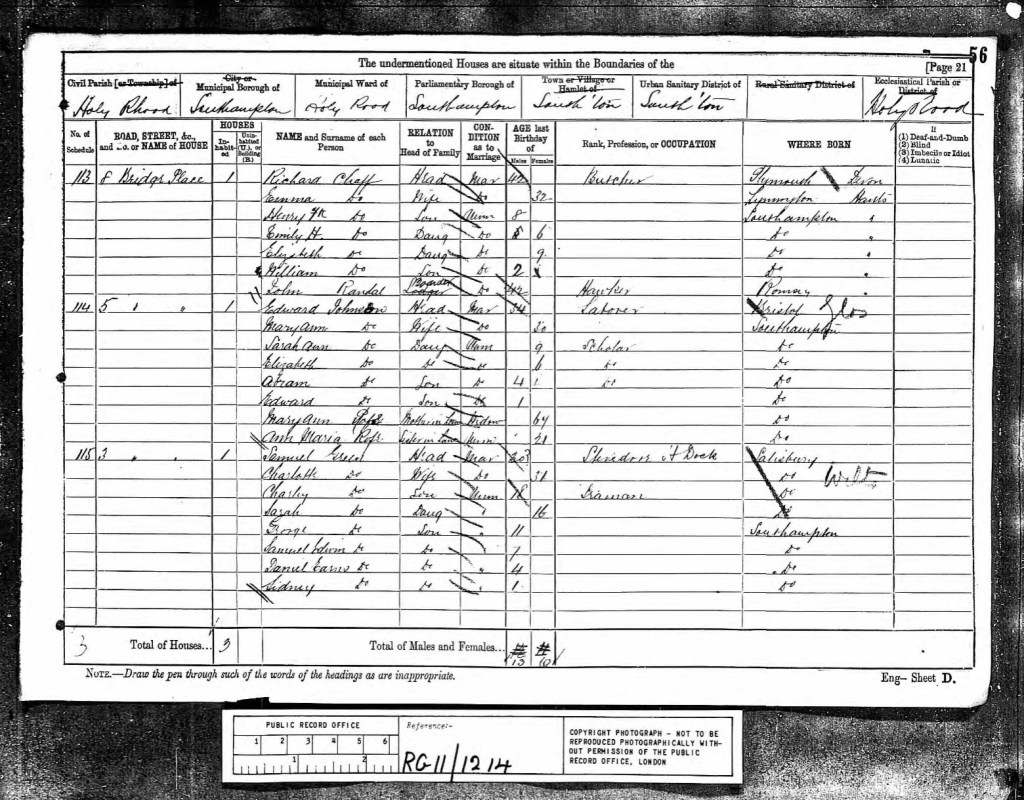

On Sunday, the 3rd day of April, 1881, Daniel Ernest Green was living with his family at Number 3, Bridge Place, Southampton, Hampshire, England. By then, he was just four years old and surrounded by the bustle of his parents, Samuel and Charlotte, and his siblings: Charles, Sarah, Sidney, George, and Samuel Edwin Green. Their home was likely filled with the sounds of sibling chatter and the routines of a hardworking family.

Daniel’s father, Samuel, supported the family as a stevedore, working long and physically demanding hours at the docks. His labor played a vital role in the thriving port city of Southampton, where the docks connected their lives to the wider world. For young Daniel, this time would have been a formative chapter, surrounded by family and the maritime culture of Southampton.

As mentioned above, Daniel’s father, Samuel Green, worked as a stevedore at the bustling docks of Southampton, a port city that was one of the busiest in the country. As a stevedore, Samuel’s role would have been physically demanding and crucial to the smooth operation of the docks. The primary responsibility of a stevedore was to load and unload cargo from ships, often using large cranes, winches, and other heavy manual labor tools. Samuel would have worked long hours, sometimes in challenging weather conditions, moving goods like coal, timber, and textiles that passed through the port.

The work was strenuous and risky, as stevedores had to handle heavy loads while working alongside large, moving ships and the powerful machinery of the docks. The docks themselves were chaotic and noisy, filled with the sounds of steamships, cargo being hoisted, and the calls of sailors and dockworkers. The risk of injury was high, as accidents involving falling cargo or mishandling of equipment could lead to serious harm or even death. Samuel’s job required strength, skill, and endurance, and while it was one of the most important roles in keeping the port functioning, it was not a job that commanded high wages or prestige.

The life of a stevedore in Southampton’s 1881 docks was one of hard physical labor, and while it provided Samuel with a steady job, it also meant long, exhausting days. Families like the Greens, living in working-class neighbourhoods like Bridge Place, often relied on the labor of men like Samuel to sustain their households. The pay was likely modest, and the working conditions tough, yet this was the reality for many in Southampton, where the dockyards were the lifeblood of the town’s economy.

For Samuel, this role would have been the cornerstone of his ability to provide for his family, while also reflecting the broader experience of industrial labor in Victorian England. It was a life of physicality and hard work, but also one filled with pride in contributing to the nation’s commercial and maritime success. However, the toll it took on him, both physically and emotionally, would have been part of the broader struggle faced by the working class in an ever-industrialising society.

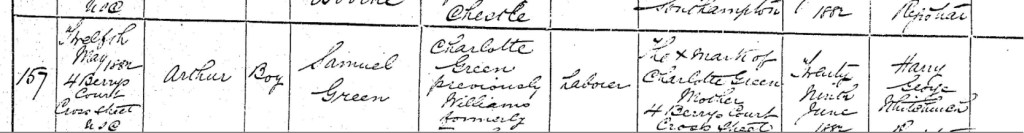

On a spring day, Friday the 12th day of May, 1882, Samuel and Charlotte Green’s son, Arthur, was born at their home, Number 4, Berry’s Court, Cox Street, in Southampton, Hampshire, England. Their family grew with joy as they welcomed this new life into their modest home. A few weeks later, on Thursday the 29th day of June, 1882, Charlotte made the journey to officially register Arthur’s birth in Southampton.

When she stood before the registrar, Mr. Harry George Whitchurch, Charlotte recorded her husband, Samuel Green, as Arthur’s father, noting his occupation as a labourer. She gave her full name as Charlotte Green, formerly Williams, formerly Feltham, and listed their address as Number 4, Berry’s Court, Cox Street. With a steady hand and determination, she marked the registry with an X, her signature and symbol of love and responsibility for her son. It’s heartwarming to imagine Charlotte ensuring that Arthur’s place in their family story was preserved with care and pride.

Berry's Court, located off Cox Street in Southampton, was a residential area that emerged during the 19th century. During this period, Southampton experienced significant urban growth, leading to the development of densely populated neighborhoods comprising courts and narrow streets.

Courts like Berry's Court typically consisted of small, closely built houses arranged around a central courtyard. These areas were often inhabited by working-class families employed in the city's industries and docks. Living conditions in such courts were frequently cramped, with limited access to sanitation and basic amenities, reflecting the broader social and economic challenges of the era.

Cox Street, situated in the Chapel area of Southampton, was part of this urban landscape. The Chapel area, named after the medieval St. Mary's Church (often referred to as "Chapel"), was known for its dense housing and proximity to industrial sites. Over time, as the city modernized and addressed public health concerns, many of these courts, including Berry's Court, were demolished or redeveloped to improve living conditions and accommodate urban planning initiatives.

Today, the landscape of Cox Street and its surroundings has transformed significantly. Modern developments have replaced the old courts, and efforts have been made to preserve the history of these areas through local archives and historical societies. While Berry's Court no longer exists, its history offers insight into Southampton's urban development and the living conditions of its past residents.

For those interested in exploring this history further, local resources such as the Southampton City Archives and the Southampton Heritage Federation provide valuable information and historical records.

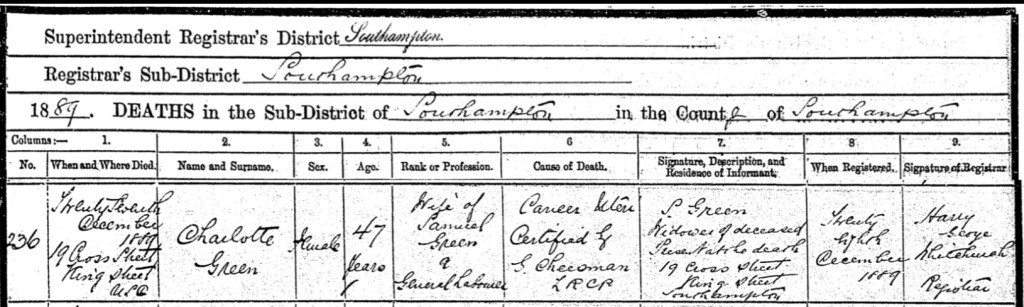

Daniel's mother, Charlotte Green (née Feltham), tragically passed away on Friday the 27th day of December, 1889, at the age of 47. She died at her home at Number 19 Cross Street, King Street, Southampton, in what must have been a deeply sorrowful moment for the Green family. Charlotte’s death was attributed to cancer, a diagnosis that, in the late 19th century, would have been difficult to treat or even fully understand. It is likely that Charlotte’s illness had been a long and painful battle, leaving her family to care for her in the final stages of her life.

Samuel, her husband, was at her side when she died, a poignant detail that reflects the closeness of their relationship. The following day, on Saturday the 28th day of December, 1889, Samuel registered her death, as was customary at the time. This act of registering her death was not only a legal necessity but a final acknowledgment of her passing, a moment that must have marked the end of a significant chapter in the Green family’s life.

At the time of her death, Charlotte was still relatively young, which would have made her passing all the more tragic. She left behind her children, including Daniel, who was still in his early teens. The loss of a mother in a working-class family would have had a profound impact, especially during a period when social and economic support for bereaved families was limited. Samuel, already working long hours as a laborer, would have had to shoulder the responsibility of raising his children without the help of his wife, which would have added additional strain to an already difficult life.

The death of Charlotte Green in 1889 marks a pivotal moment in Daniel’s life. Her passing left a void in the family, one that would have shaped his experiences and his journey into adulthood. The pain of losing his mother at such a young age, compounded by the challenges of growing up in the harsh environment of Victorian Southampton, likely influenced Daniel’s character and his perspective on life.

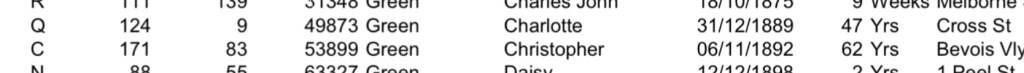

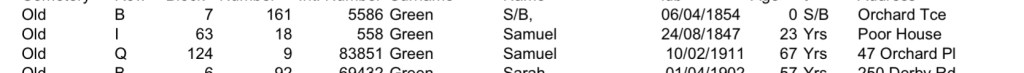

Charlotte Green (née Feltham), Daniel's mother, was laid to rest on Tuesday the 31st day of December, 1889, in the quiet, solemn grounds of Southampton Old Cemetery on Hill Lane. Her final resting place was in Row Q, Block 124, with the interment marked as Number 49873. This was the place where her family could visit and remember her, despite the harsh realities of life in Victorian Southampton. The cemetery itself, an enduring part of the city’s history, became the backdrop for many families like the Greens, who experienced both joy and sorrow within its gates.

Samuel, Daniel’s father, who had been by Charlotte’s side through her illness and death, would later join her in this peaceful resting place. In the years that followed, Samuel would find himself grieving the loss of his beloved wife, a partner with whom he had shared both the challenges and the small victories of life. His decision to be laid to rest beside Charlotte was a poignant final act, reflecting a deep and lasting love that transcended the struggles they had faced together.

For Daniel, the loss of his mother must have been a profound turning point. To visit her grave would have meant confronting the early death of a loved one and coming to terms with the hardship of losing a mother at such a young age. The act of burial in a communal cemetery, alongside other families who had experienced similar losses, would have been a shared experience in a world where death was an ever-present part of life, particularly in the working-class communities of Victorian England.

The graves of Charlotte and Samuel Green in Southampton Old Cemetery now serve as a silent testimony to their lives, a reminder of their struggles, their love, and the resilience of a family enduring hardship. Their resting place, marked in the records of the cemetery, holds the memory of the mother who gave birth to Daniel and the father who worked tirelessly to care for his family. It is a symbol of the enduring ties that bind generations, even as time moves forward.

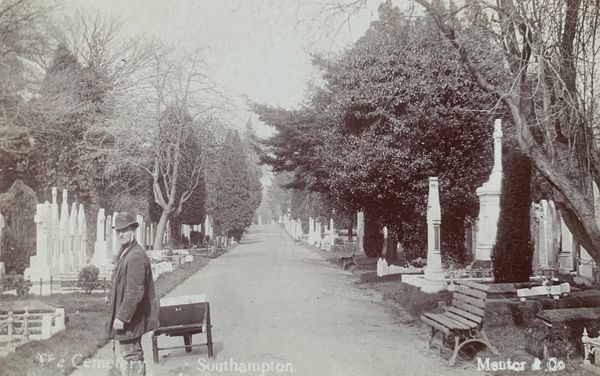

Southampton Old Cemetery, located on Hill Lane in Southampton, Hampshire, England, is a historically rich and atmospheric site. Established in 1841, it spans approximately 27 acres and holds great significance as one of England’s earliest municipal cemeteries, reflecting the Victorian era's approach to burial practices and memorialization.

The cemetery was designed as part of the broader urban planning efforts in response to growing public health concerns during the 19th century. At the time, traditional churchyards were becoming overcrowded, leading to unsanitary conditions and the risk of disease outbreaks. Southampton Old Cemetery was one of the solutions to these challenges, providing a new, carefully planned space for burials. It was developed in conjunction with other garden cemeteries of the era, which aimed to offer peaceful, landscaped grounds for mourning and reflection.

The cemetery was designed by the noted landscape gardener and cemetery designer John Claudius Loudon. Loudon's innovative approach emphasized the integration of natural beauty with functionality. The site includes winding pathways, mature trees, and carefully planned vistas, embodying the Victorian ideal of creating a serene, park-like atmosphere. The planting of various trees, shrubs, and flowers enhances its tranquil character, making it a haven for both history enthusiasts and nature lovers.

Southampton Old Cemetery is the final resting place for over 116,000 individuals, representing a wide cross-section of society. Among the graves, there are numerous fascinating stories and connections to significant historical events. The cemetery contains Commonwealth War Graves from both World Wars, with the resting places of soldiers, sailors, and airmen commemorated in beautifully maintained plots. Additionally, there are memorials related to the tragic sinking of the RMS Titanic in 1912, as Southampton was deeply connected to the ship's crew and passengers. The Titanic graves include poignant tributes to those who perished, adding a layer of maritime history to the cemetery's narrative.

The cemetery also reflects the multicultural and diverse history of Southampton, with graves of individuals from various religious and cultural backgrounds. The rich variety of memorials, from simple markers to elaborate mausoleums, showcases Victorian attitudes toward death, remembrance, and social status.

Over the years, Southampton Old Cemetery has evolved into not just a place of burial but also a historical and ecological treasure. It is a designated Site of Importance for Nature Conservation (SINC) due to its rich biodiversity. The cemetery provides a habitat for numerous bird species, butterflies, and other wildlife, making it a green oasis in the heart of the city.

Today, Southampton Old Cemetery is valued not only for its historical and ecological significance but also for its role as a peaceful retreat for visitors. Guided tours and community efforts help preserve its legacy, sharing its stories with future generations while ensuring its ongoing care. Walking through its grounds offers a unique glimpse into Southampton's past, reflecting the lives of those who helped shape the city and its connection to wider historical events.

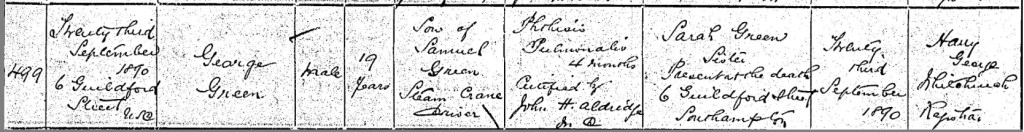

On a somber day, Tuesday the 23rd day of September, 1890, Samuel and the Late Charlotte Green’s 19-year-old son, George, passed away at their home, Number 6, Guildford Street, Southampton, Hampshire, England. George, the brother of Daniel, succumbed to Phthisis Pulmonalis, a condition he had battled for four months. His death was certified by Dr. John H. Aldridge, marking the end of a life far too short.

Daniel and George’s sister, Sarah Green, was by his side during his final moments, offering love and support. Later that same day, with a heavy heart, Sarah went to the registry office to officially record her brother’s passing. She gave the family’s address as Number 6, Guildford Street. The registrar, Mr. Harry George Whitchurch, who had previously registered their brother Arthur’s birth, once again recorded the family’s sorrowful milestone.

It’s heartbreaking to imagine the grief that filled their home that day, but Sarah’s courage in ensuring her brother’s death was properly documented reflects the strength and love that bound their family together during such a painful time.

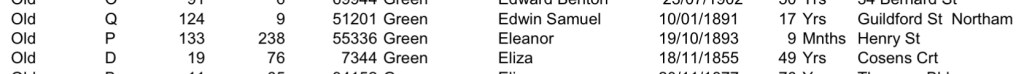

With hearts heavy with sorrow, Daniel and his family came together on Saturday the 27th of September, 1890, to bid a tender farewell to George Green. They laid him to rest in the peaceful grounds of Southampton Old Cemetery on Hill Lane, where he found his eternal place in Row Q, Block 124, Number 9. This sacred resting spot held profound significance, as it was where their beloved mother, Charlotte, had been laid to rest just months earlier, on the 31st of December, 1889. George’s interment, marked as Number 50813, united him in eternal slumber with their dear mum, offering a poignant comfort in their shared resting place.

On a winter day, Monday the 5th day of January, 1891, Samuel and the late Charlotte Green’s 17-year-old son, Samuel Edwin Green, passed away at their family home, Number 6, Guildford Street, Southampton, Hampshire, England. Known as Edwin Samuel in the official records, he was Daniel’s brother and another life tragically claimed by Phthisis, a devastating illness that had already struck the family.

Their father, Samuel Green, a steam crane driver, was present at his son’s side during his final moments. Just two days later, on Wednesday the 7th day of January, 1891, Samuel went to the registry office to officially record his son’s death under the name Edwin Samuel. He provided their address as Number 6, Guildford Street, Southampton, to the registrar, Mr. Harry George Whitchurch, who had been part of so many pivotal moments in the Green family’s life.

The loss of Edwin Samuel must have weighed heavily on the family, yet Samuel’s dedication to ensuring his son’s passing was properly recorded reflects his enduring love and responsibility, even in the face of such profound sorrow.

With profound sadness, Daniel and his family laid Edwin Samuel to rest on Saturday the 10th of January, 1891, in the serene grounds of Southampton Old Cemetery on Hill Lane. Edwin’s final resting place, in Row Q, Block 124, Number 9, held deep familial significance. This was the same sacred spot where their cherished mother, Charlotte, had been lovingly laid to rest on the 31st of December, 1889, and where their dear brother, George Green, was tenderly interred on the 27th of August, 1890. Edwin’s interment, marked as Number 51201, brought a bittersweet solace, as he joined his mother and brother in eternal peace, forever united in love and memory.

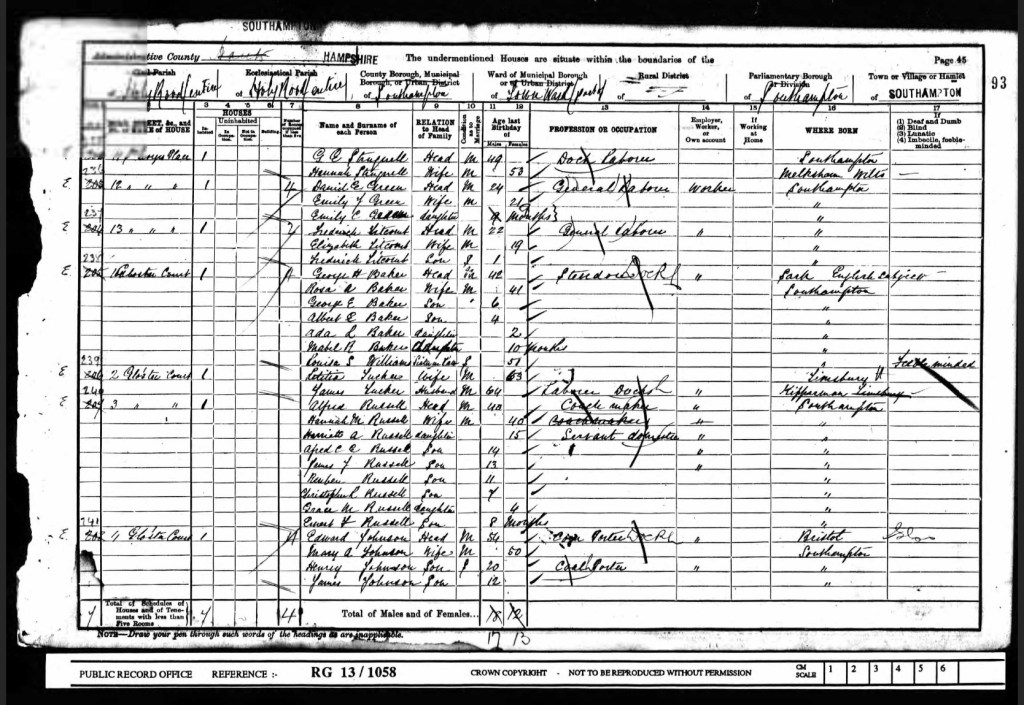

On Sunday, the 5th day of April, 1891, Daniel Ernest Green, now 14 years old, was living at Number 7 St. John’s Buildings, Town Quay, Southampton, Hampshire, England. Life had changed significantly for the Green family. His father, Samuel, was now a widower, raising Daniel and his two brothers, Arthur and Sidney, on his own.

Samuel had taken on the demanding role of a steam crane driver, a position that reflected the industrial growth of the bustling port city. His work would have been vital to the operations at Town Quay, handling the heavy cargo that passed through Southampton. The absence of Daniel’s mother, Charlotte, must have been deeply felt in their small household, but the family’s resilience and Samuel’s dedication held them together during this period of transition.

Jumping forward to the year 1899, England was in the late Victorian era, with Queen Victoria serving as the monarch. Her reign, which began in 1837, was nearing its end, and she remained a symbol of stability and the British Empire's dominance. The Prime Minister was Robert Gascoyne-Cecil, 3rd Marquess of Salisbury, a member of the Conservative Party who led the government during this time of imperial expansion. The United Kingdom was governed by the 25th Parliament, dominated by Conservative policies and focused on maintaining Britain’s global influence.

Society in 1899 was deeply stratified, with clear distinctions between social classes. The upper class, composed of aristocrats and wealthy landowners, held significant power and influence in politics, culture, and the economy. The middle class was expanding, driven by industrialization and the growth of professions like law, medicine, and commerce. The working class, which made up the majority of the population, faced grueling labor in factories, mines, and domestic service, often under poor conditions. Poverty was a stark reality for many, particularly in urban slums and rural areas, where people struggled with inadequate housing, low wages, and limited access to basic necessities.

Fashion in 1899 reflected Victorian ideals of propriety and elegance. Women’s clothing featured tightly corseted bodices, high necklines, and long skirts with elaborate trimmings. Puffed sleeves and hats adorned with feathers and ribbons were popular accessories. Men typically wore tailored suits, including frock coats or morning coats for formal occasions, with waistcoats and top hats. Children were dressed in miniature versions of adult attire, with boys wearing sailor suits or short trousers and girls donning pinafores over dresses.

Education was shaped by the Elementary Education Act of 1870, which made schooling compulsory for children aged 5 to 12. However, many working-class families needed their children to contribute to household income, so education often ended early. Schools emphasized basic literacy, arithmetic, and religious instruction, with a focus on discipline and conformity. Secondary education was primarily available to the middle and upper classes, leaving the working class with fewer opportunities for upward mobility.

Food in 1899 varied greatly between classes. The wealthy enjoyed lavish meals featuring a wide array of dishes, including roasts, game, and puddings, often accompanied by imported wines and delicacies. Middle-class families ate more modestly but still had access to fresh meat, vegetables, and tea. The working class relied on inexpensive staples like bread, potatoes, and tea, with occasional access to meat or fish. For the poorest in society, meals were sparse and often consisted of gruel or broth, leading to widespread malnutrition.

Transportation in England was dominated by the railway system, which connected towns and cities and revolutionized long-distance travel. Horse-drawn carriages remained the primary mode of urban transportation, though bicycles were becoming increasingly popular across all classes for personal mobility. The automobile was in its infancy, with a small number of wealthy individuals beginning to adopt motor cars as a status symbol.

Heating and lighting in 1899 were reliant on coal and gas. Coal-fired fireplaces and stoves were the main sources of warmth in homes, while gas lamps provided lighting in urban areas. Electricity was slowly being introduced, but it was still a luxury reserved for the wealthy and not yet widespread.

Entertainment in 1899 offered a mix of traditional and emerging forms. Theatres and music halls were major attractions, offering performances of plays, operas, and comedic acts. Literature was a popular pastime, with novels by authors such as Thomas Hardy, George Bernard Shaw, and Arthur Conan Doyle capturing public interest. Sports like cricket, football, and horse racing were widely enjoyed, and the emergence of the phonograph and early motion pictures hinted at the technological innovations to come.

Gossip in 1899 often revolved around the aristocracy and royal family, with society captivated by tales of scandal, romance, and intrigue. Public interest was also piqued by the heroes and events of the Boer War, which had begun in October that year. This conflict between the British Empire and the Boer Republics in South Africa dominated news and conversation.

Historically, 1899 was marked by significant events. In England, the Boer War reflected the challenges of maintaining a global empire and stirred both patriotism and controversy. In Ireland, the demand for Home Rule persisted, though it faced staunch resistance in Parliament. Wales saw the early stirrings of the Welsh Revival, a religious and cultural movement that would gain momentum in the coming years.

The differences between social classes were stark. The wealthy lived in grand homes with servants, enjoyed private education, and led lives of leisure and influence. The working class endured long hours of labor in factories or as domestic workers, often living in cramped and unsanitary housing. The poorest in society faced dire conditions in slums, workhouses, or rural poverty, struggling to meet basic needs. Despite these disparities, industrialization and reform movements were slowly beginning to improve living standards for some, setting the stage for further societal changes in the 20th century.

On a spring day, Monday the 22nd of May, 1899, at The Parish Church of Holy Rood in Southampton, Hampshire, England, 24-year-old Daniel Ernest Green married 20-year-old Emma Jane Williams. Daniel, a laborer, and Emma, described as a spinster, pledged their lives to one another surrounded by the support of their loved ones.

At the time of their marriage, the couple resided at 65 George’s Place, a humble home where they likely began dreaming of their future together. Daniel recorded his father’s name as Samuel Green, also a laborer, while Emma gave her father’s name as Richard Williams, who shared the same hardworking occupation.

The ceremony was witnessed by Richard John Williams and Jane Read, whose presence underscored the bond of family and friendship that surrounded the couple. In a poignant detail, Daniel signed the marriage register with an "X," a mark that, while simple, carried the weight of his vow and the promise of the life he was building with Emma.

Holyrood Church, often referred to as Holy Rood Church, is a historic landmark in Southampton, England, with a rich and storied past. Established in 1320, it was one of the five original churches serving the old walled town, a testament to Southampton's medieval significance as a bustling port and community hub. Its prominent location in the heart of the town made it an integral part of daily life, providing a place of worship and solace for centuries.

The church's architecture reflected the Gothic style of the period, with soaring arches and intricate stonework that spoke to the craftsmanship and devotion of its builders. For more than six centuries, Holyrood Church stood as a silent witness to the unfolding history of Southampton, weathering the tumult of time, including the English Civil War and the Industrial Revolution.

Tragically, during the Blitz in November 1940, Holyrood Church was almost entirely destroyed by enemy bombing. The devastation left the church as little more than a shell, a stark reminder of the war's toll on the city and its people. However, rather than being forgotten, Holyrood Church found a renewed purpose in its ruins. In 1957, the remaining structure was dedicated as a memorial to the sailors of the Merchant Navy, honoring their bravery and sacrifices, particularly during the two World Wars.

Today, Holyrood Church is a Grade II* listed building, recognized for its historical and cultural significance. Its open-air ruins stand as a poignant monument, preserved to connect visitors with both the maritime heritage of Southampton and the resilience of its community. It is not merely a relic of the past but a symbol of remembrance and endurance, cherished by residents and visitors alike.

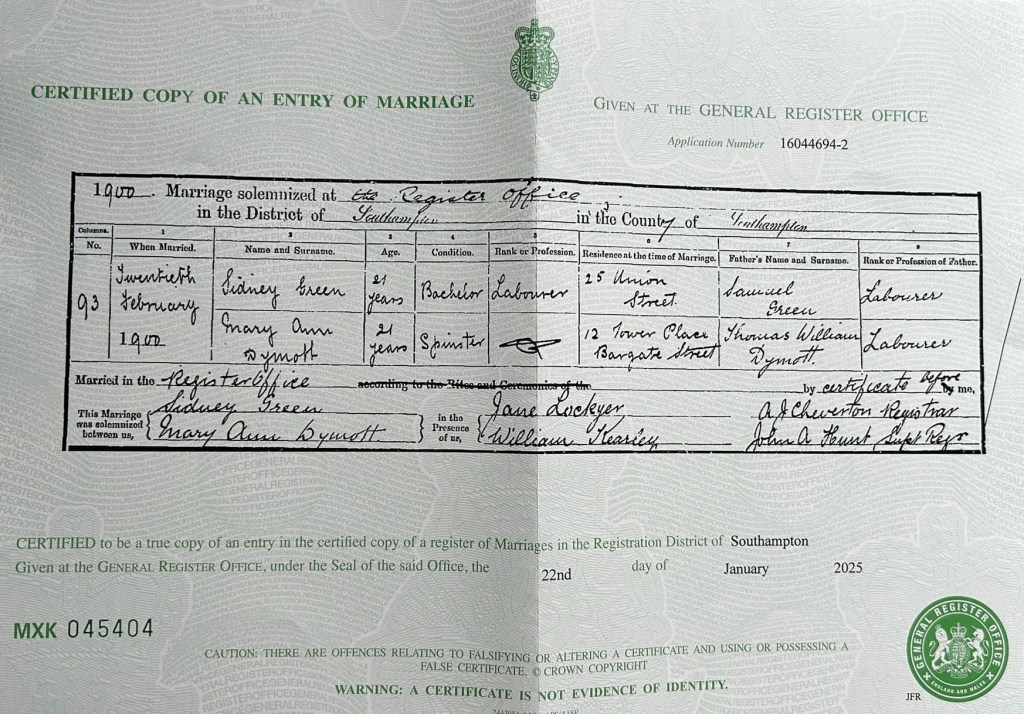

On a winter’s day, Tuesday the 20th Day of February, 1900, in the heart of Southampton, Daniel’s brother, Sidney Green and Mary Ann Dymott stood side by side at The Registry Office, ready to begin their journey together as husband and wife. Sidney, a hardworking 21-year-old labourer from Number 25, Union Street, and Mary Ann, also 21, from Number 12, Tower Place, Bargate Street, exchanged vows in the presence of their loved ones.

The ceremony was officiated by A.J. Cheverton, with John A. Hunt overseeing the proceedings, and witnessed by Jane Lockyer and William Keasley. As they signed their names in the marriage register, they carried with them the legacies of their fathers, Samuel Green and Thomas William Dymott, both labourers, men who had shaped their lives and prepared them for this moment.

It was more than just a legal union, it was the beginning of a shared life, filled with hopes, dreams, and the promise of a future built together.

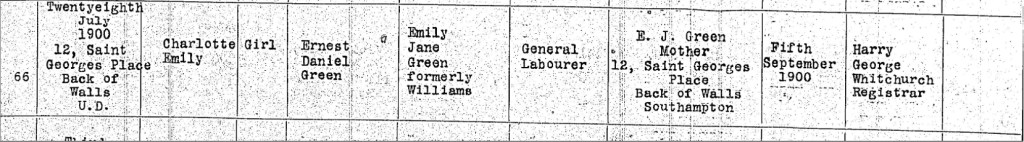

On a summer day, Saturday the 28th day of July, 1900, Daniel Ernest and Emma Jane Green welcomed their daughter, Charlotte Emily Green, into the world. She was born at their home, Number 12, Saint George’s Place, Back of Walls, Southampton, Hampshire, England.

Childbirth in 1900 was a vastly different experience from today. With most births taking place at home, as Charlotte’s did, women relied on the support of family members or a local midwife rather than a doctor. The setting would have been modest, likely the family’s bedroom, prepared as best as possible for cleanliness. Without modern pain relief or antiseptic techniques, the experience could be long and arduous, and both mother and child faced significant risks due to complications or infection. Yet, amidst these challenges, the arrival of a healthy baby was a moment of profound joy and relief for the family.

On Wednesday the 5th day of September, 1900, Emma, also known as Emily, Charlotte’s devoted mother, went to the registry office to officially record her daughter’s birth. She gave her name as Emily Jane Green, formerly Williams, and proudly listed her husband, Ernest Daniel Green, using his middle name rather than his first name Daniel, as Charlotte’s father, noting his occupation as a general labourer. Emma also confirmed their family address as Number 12, Saint George’s Place, Back of Walls.

The registrar, Mr. Harry George Whitchurch, who had been part of so many key moments for the Green family over the years, once again entered this joyous event into the official record. Despite the challenges of the time, Emma’s strength and care ensured her daughter’s safe arrival and rightful place in the family’s story, a moment of hope and love in their home.

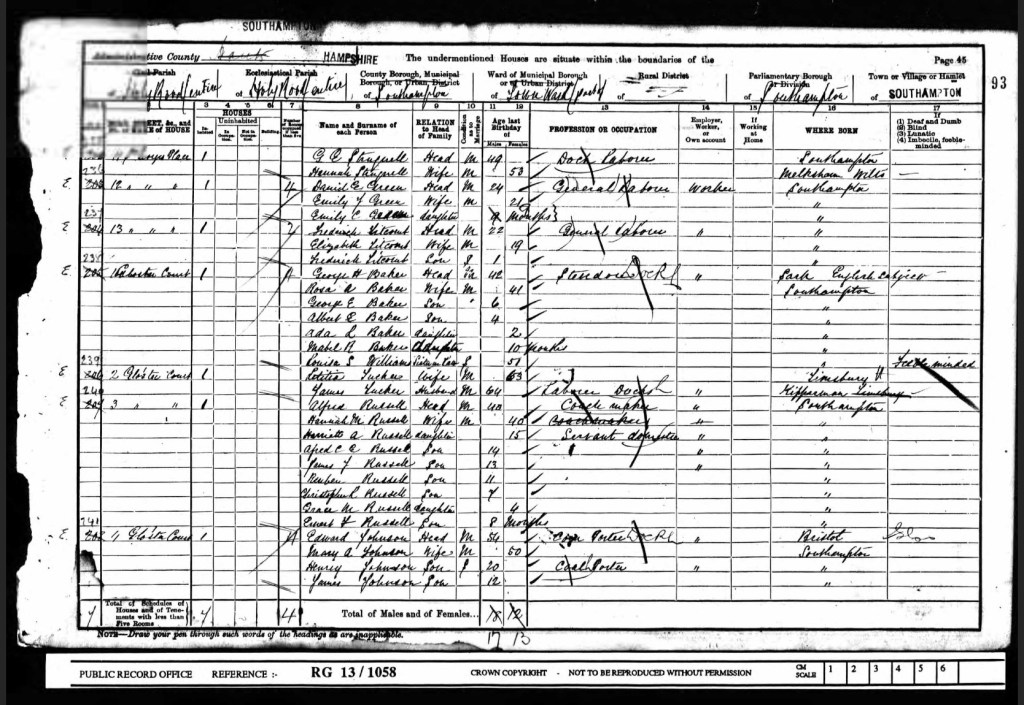

The 1901 census, completed on Sunday, March 31, 1901, provides a snapshot of the Green family’s life at the time. Daniel Ernest Green was recorded as living at St George’s Place, Southampton, Hampshire, England, with his wife, Emma (who was listed as Emily), and their young daughter, Charlotte Emily, similarly recorded under the name Emily. Daniel was documented as working as a General Labourer, reflecting the hard work and dedication that sustained the family. The census also notes that the family occupied four rooms in their home, likely a modest yet sufficient space for their needs at the time. This record offers a glimpse into the Greens’ day-to-day life, with Daniel providing for his family, Emma managing the household, and little Charlotte Emily growing up in a home filled with the love and resilience that defined this era.

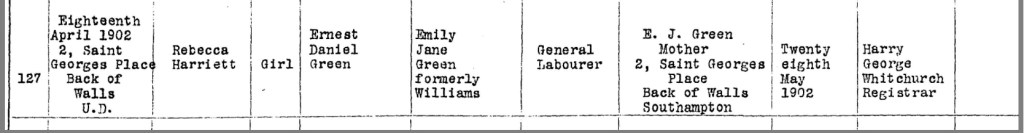

On a spring day, Friday the 18th of April, 1902, Daniel Ernest and Emma Jane Green welcomed their second daughter, Rebecca Harriett Green, into the world. She was born at their new home, Number 2, Saint George’s Place, Back of Walls, Southampton, Hampshire, England.

On Wednesday the 28th of May, 1902, Rebecca’s mother, Emma, who preferred to go by Emily, went to the registry office to officially record her daughter’s birth. She provided her name as Emily Jane Green, formerly Williams, and listed her husband as Ernest Daniel Green, a general labourer, using his middle name rather than his first. Emma also confirmed their family’s address as Number 2, Saint George’s Place.

The registrar, Mr. Harry George Whitchurch, who had been present for many key moments in the Green family’s history, once again documented this joyous occasion. Rebecca’s birth marked another chapter in the life of the Green family, filled with love and hope for the future in their growing home.

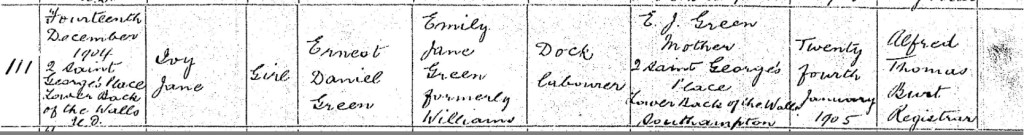

On a winters day, Wednesday the 14th day of December, 1904, Daniel Ernest and Emma Jane Green celebrated the arrival of their daughter, Ivy Jane Green, born at their home at Number 2, Saint George’s Place, Lower Back of Walls, Southampton, Hampshire, England.

On Tuesday the 24th day of January, 1905, Emma, who preferred to go by Emily, made her way to the registry office to officially record Ivy’s birth. She provided her name as Emily Jane Green, formerly Williams, and listed her husband as Ernest Daniel Green, a Dock Labourer. As she had done before, Emma used her husband’s middle name, Ernest, instead of his first name, Daniel, and recorded their family address as Number 2, Saint George’s Place, Lower Back of Walls.

This time, the registrar documenting this joyful event was Mr. Alfred Thomas Burt. Ivy Jane’s birth added another cherished member to the Green family, who continued to grow and thrive in their Southampton home.

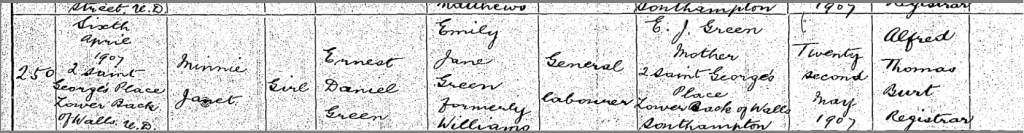

On Saturday the 6th day of April, 1907, Daniel Ernest and Emma Jane Green welcomed their daughter, Minnie Janet Green, into the world. She was born at their home, Number 2, Saint George’s Place, Lower Back of Walls, Southampton, Hampshire, England.

On the Wednesday 22nd day of May, 1907, Emma, who still preferred to go by Emily, visited the registry office to officially register Minnie’s birth. As she had done previously, she provided her name as Emily Jane Green, formerly Williams, and listed her husband as Ernest Daniel Green, a General Labourer. Emma continued the practice of using her husband’s middle name, Ernest, instead of his first name, Daniel, and confirmed their address as Number 2, Saint George’s Place, Lower Back of Walls.

The registrar, Mr. Alfred Thomas Burt, once again documented this happy addition to the Green family. Minnie Janet’s birth brought more joy and life into the bustling household at Saint George’s Place, continuing the legacy of love and resilience shared by the Greens.

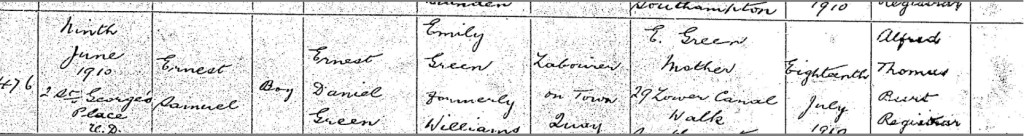

On a summers day, Thursday the 9th day of June, 1910, Daniel Ernest and Emma Jane Green welcomed their son, Ernest Samuel Green, into the world. He was born at their previous family home, Number 2, Saint George’s Place, Southampton, Hampshire, England.

On Monday the 18th day of July, 1910, Emma, whom still preferred to go by Emily, officially registered her son’s birth. As she had done before, she recorded her name as Emily Jane Green, formerly Williams, and listed her husband as Ernest Samuel Green, this time noting his occupation as a Labourer in the Town Quay. She also provided their new address as Number 29, Lower Canal Walk, Southampton, marking a change in residence for the family.

The registrar, Mr. Alfred Thomas Burt, once again entered this significant event into the official record. Ernest Samuel’s birth added to the growing Green family, bringing new hope and joy as they continued their journey together in Southampton.

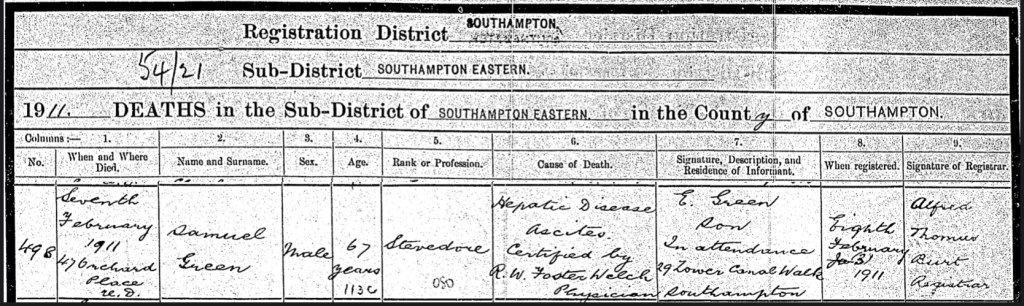

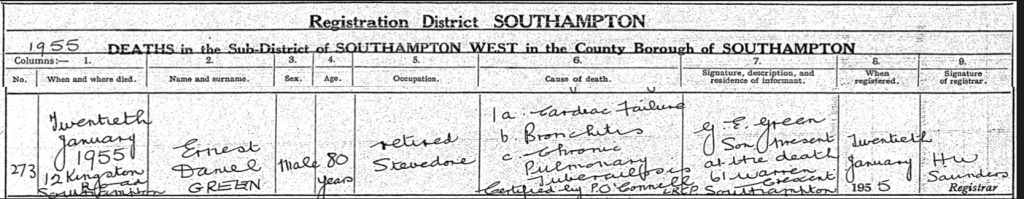

Heartbreakingly, Daniel’s father, Samuel Green, passed away on Tuesday the 7th day of February, 1911, at the age of 67. He died at Number 47, Orchard Place, Southampton, Hampshire, England, from Ascites, a painful buildup of fluid in the abdomen, and Hepatic Disease, often associated with liver damage caused by excessive alcohol consumption, obesity, or an undiagnosed hepatitis infection.

Samuel’s son, Daniel Ernest Green, was by his side during his final moments. The following day, Wednesday the 8th day of February, 1911, Daniel registered his father’s death. He gave his own address as Number 29, Lower Canal Walk, Southampton, and listed Samuel’s occupation as a Stevedore, a demanding job that involved loading and unloading ships in the bustling docks of Southampton.

Once again, the family’s loss was recorded by Mr. Alfred Thomas Burt, the registrar. Samuel’s passing marked a profound loss for the Green family, leaving behind a legacy of hard work and resilience. Daniel’s presence at his father’s side and his duty in registering the death reflect the love and respect he held for the man who had shaped his life.

On Friday the 10th day of February, 1911, Daniel, along with family and loved ones, gathered to bid a final farewell to his father, Samuel Green. The funeral took place at The Southampton Old Cemetery on Hill Lane, Southampton, a serene resting place steeped in history. Samuel was laid to rest in Row Q, Block 124, Grave Number 9, with Interment Number 83851.

In a touching tribute to their enduring bond, Samuel was buried alongside his beloved wife, Charlotte. Together again in eternal rest, their shared grave serves as a poignant reminder of their lives and legacy. Surrounded by the love and grief of those left behind, Samuel’s burial marked the end of a chapter for the Green family, yet his memory and influence would live on in their hearts and stories.

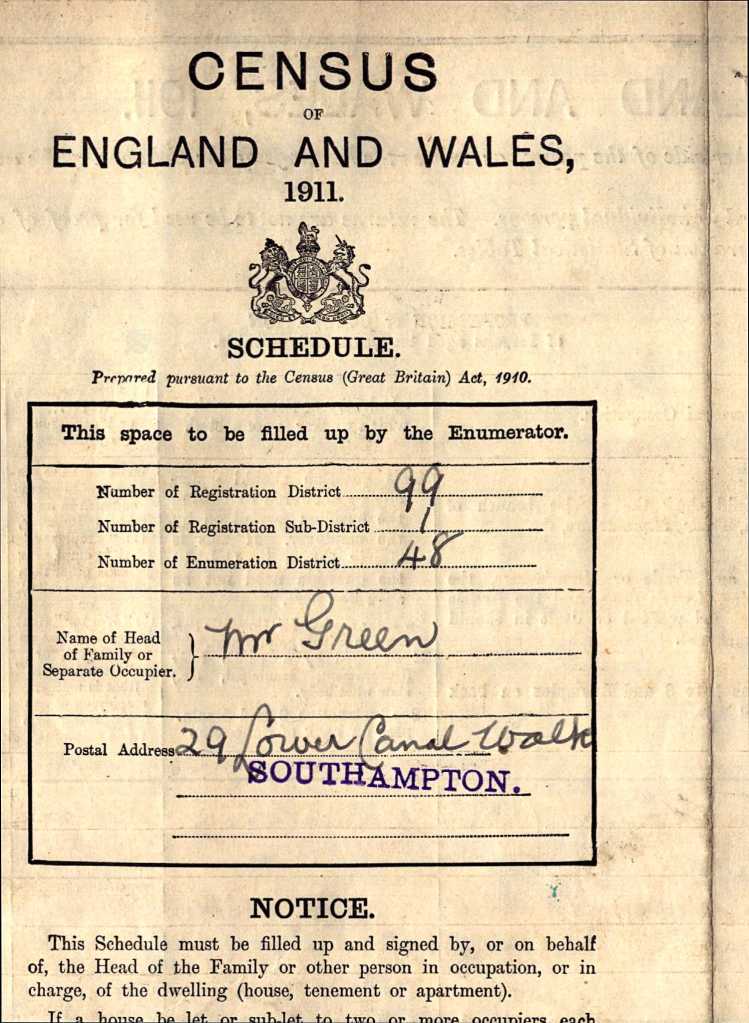

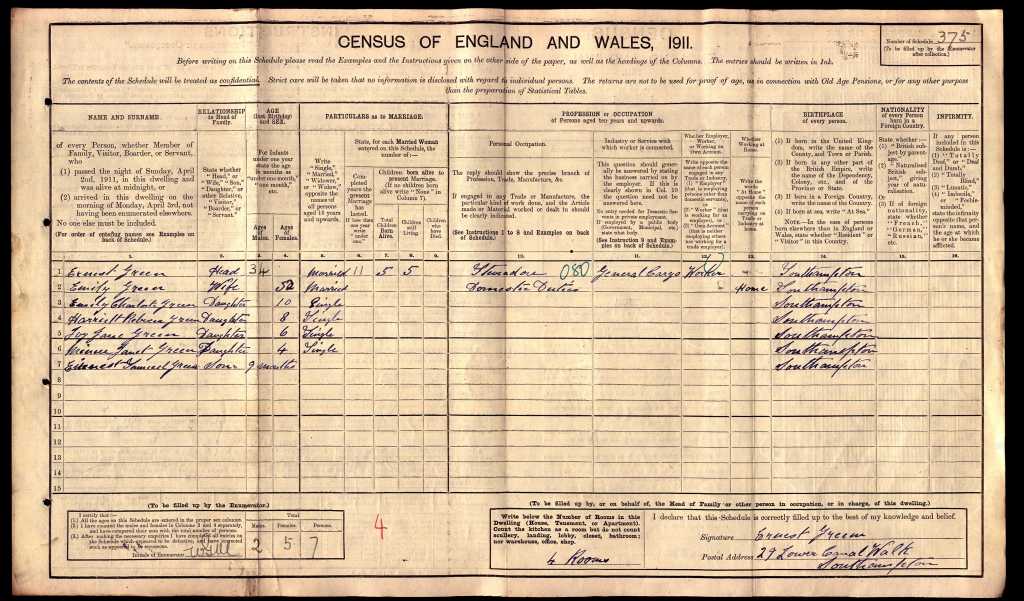

On Sunday the 2nd day of, April, 1911, Daniel Ernest Green and his family resided at Number 29, Lower Canal Walk, in the parish of St Mary, Southampton, Hampshire, England. The household included Daniel’s wife, Emma (who preferred to go by Emily), and their five children: Ernest Samuel, Emily Charlotte, Harriet Rebecca, Ivy Jane, and Minnie Janet Green.

Daniel, recorded as Ernest in the census, worked as a Stevedore handling general cargo, a physically demanding job vital to the bustling port of Southampton. Emma, listed as Emily, managed the household and cared for the family, with “Domestic Duties” noted as her occupation.

The census reveals that Daniel and Emma had been married for 11 years and were fortunate to have all five of their children living. Their home had four rooms, which would have included bedrooms, a kitchen, and living space, a modest but functional dwelling for the growing family.

Interestingly, many of the Greens were recorded under their middle names, a common practice in the family. Daniel was listed as Ernest, Emma as Emily, Charlotte as Emily Charlotte, and Rebecca as Harriet Rebecca. Ivy, Minnie, and young Ernest were listed by their birth names. This detail adds a personal touch to their story, reflecting the preferences and quirks of the Green family as they built their lives together in Southampton.

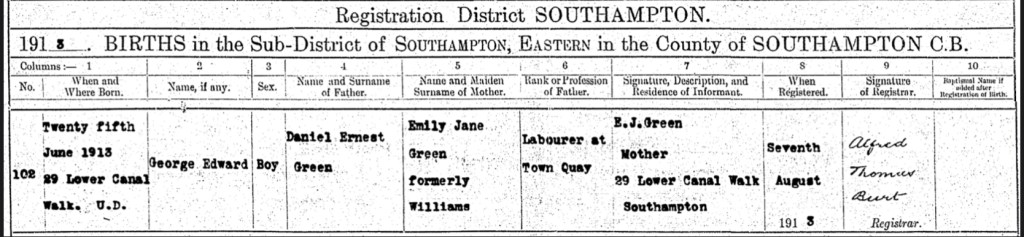

On a summer day, Wednesday the 25th day of June, 1913, Daniel Ernest and Emma Jane Green celebrated the birth of their son, George Edward Green. He was born at their family home at Number 29, Lower Canal Walk, Southampton, Hampshire, England, filling their household with new joy and hope.

On Thursday the 7th day of August, 1913, Emma, who continued to prefer the name Emily, officially registered George Edward’s birth. She recorded her name as Emily Jane Green, formerly Williams, and listed her husband, Daniel Ernest Green, as a Labourer working at the Town Quay. Their family address was recorded as Number 29, Lower Canal Walk, Southampton.

The registrar, Mr. Alfred Thomas Burt, who had documented many milestones for the Green family, recorded this occasion with care. The informant of the birth was listed as E. J. Green, Mother, affirming Emma’s involvement in ensuring her son’s place in the official records.

George Edward was not just a beloved addition to the Green family but would later become the paternal grandfather of your husband, creating a direct bridge between the family’s rich past and its present-day legacy. His birth marked a significant chapter in the lineage of the Greens, ensuring their story continues through the generations.

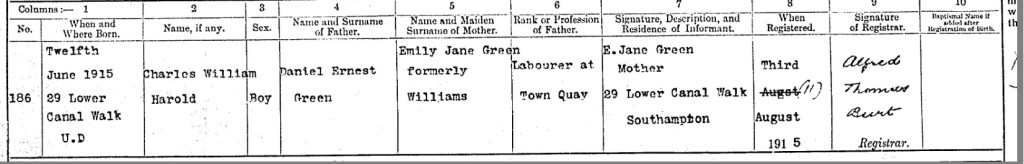

On Saturday the 12th day of June, 1915, Daniel Ernest and Emma Jane Green welcomed their son, Charles William Harold Green, into the world. He was born at the family home at Number 29, Lower Canal Walk, Southampton, Hampshire, England.

On Tuesday the 3rd day of August, 1915, Emma, who preferred to go by Emily, officially registered Charles’s birth. As with her other children, she recorded her name as Emily Jane Green, formerly Williams, and listed her husband as Daniel Ernest Green, a Labourer at the Town Quay. Their family address was again recorded as Number 29, Lower Canal Walk, Southampton.

Mr. Alfred Thomas Burt, who had documented so many milestones for the Green family, recorded Charles’s birth into the official records. Charles’s arrival added another treasured member to the Green household, a beacon of joy during a period marked by global conflict.

Charles William Harold Green’s birth became a significant part of the family’s ongoing legacy, his story interwoven with those of his siblings and the generations that followed.

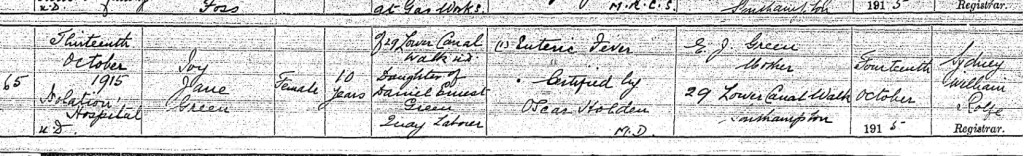

Heartbreakingly, Daniel and Emma’s beloved 10-year-old daughter, Ivy Jane Green, passed away on Wednesday the 13th day of October, 1915, at the Isolation Hospital in Southampton, Hampshire, England. Ivy tragically succumbed to Enteric Fever, as certified by Oscar Holden, the Medical Director. Her untimely death left a profound void in the Green family.

The following day, on Thursday the 14th day of October, 1915, Emma, who preferred to be known as Emily, faced the devastating task of registering Ivy’s death in Southampton. With a heavy heart, she provided the registrar, Mr. Sidney William Rolfe, with the necessary details. Emma stated that their family home was at Number 29, Lower Canal Walk, Southampton, and that Ivy was the cherished daughter of Daniel Ernest Green, a Quay Labourer.

Mr. Rolfe recorded the informant of Ivy’s death as E. J. Green, Mother, of 29, Lower Canal Walk, Southampton. Ivy’s passing was an immeasurable loss to her family, leaving behind treasured memories of her short but cherished life.

Enteric fever, commonly known today as typhoid fever, is a systemic bacterial infection primarily caused by *Salmonella enterica* serovar Typhi (S. Typhi) and occasionally by *Salmonella Paratyphi* (paratyphoid fever). It is a disease marked by prolonged fever, abdominal pain, weakness, and a range of gastrointestinal symptoms, often accompanied by characteristic rashes known as "rose spots."

The history of enteric fever is deeply intertwined with human civilization and the development of dense urban populations where sanitation and clean water were often insufficient. It is believed to have been present for thousands of years, with ancient accounts of prolonged febrile illnesses in populations possibly describing outbreaks of typhoid-like diseases. However, it was not clearly distinguished from other febrile illnesses until the advent of microbiology in the 19th century.

One of the most notable historical outbreaks occurred in ancient Greece during the Peloponnesian War (431–404 BCE). The Athenian Plague, as described by Thucydides, may have been an early instance of enteric fever, though other diseases like smallpox and measles are also considered possibilities. Symptoms described include fever, gastrointestinal distress, and delirium, consistent with severe typhoid.

The modern understanding of enteric fever began in the 19th century with advances in bacteriology. In 1856, British physician William Budd proposed that typhoid fever was a communicable disease spread through contaminated water and fecal matter, challenging the prevailing miasma theory of disease. His observations were foundational in linking public health measures to disease prevention.

In 1880, German pathologist Karl Joseph Eberth identified the causative organism, *Salmonella Typhi*, in the tissues of patients who had died of typhoid. This discovery, along with the later work of Georg Theodor August Gaffky, who successfully cultured the bacterium, confirmed the bacterial nature of the disease.

The disease gained infamy in the late 19th and early 20th centuries with outbreaks in industrializing nations. Poor urban sanitation, overcrowding, and inadequate sewage disposal contributed to widespread transmission. A well-known case during this period was "Typhoid Mary" (Mary Mallon), an asymptomatic carrier who worked as a cook in New York City and was linked to multiple outbreaks, illustrating the role of carriers in spreading the disease.

Vaccination efforts against typhoid began in the late 19th century. Almroth Wright developed the first typhoid vaccine in 1896, which was used effectively during World War I to protect soldiers in unsanitary trench conditions. Public health measures, such as improved water supply systems, sewage treatment, and food hygiene, further reduced the incidence of typhoid in developed nations.

Despite these advancements, enteric fever remains a significant public health concern in many low- and middle-income countries, particularly in South Asia, Sub-Saharan Africa, and parts of Southeast Asia. Poor sanitation, contaminated drinking water, and limited access to medical care perpetuate its prevalence. Multidrug-resistant strains of *Salmonella Typhi* have emerged in recent decades, posing new challenges to treatment. Vaccines, including oral and injectable formulations, are now widely available and recommended in endemic areas.

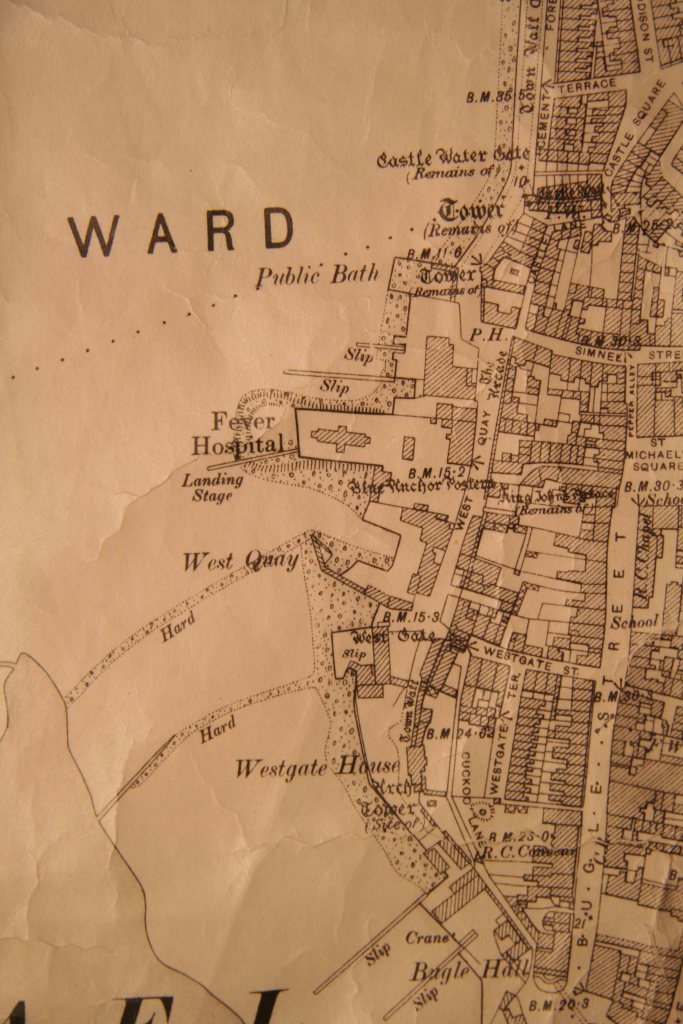

The Isolation Hospital in Southampton, Hampshire, was an important medical facility dedicated to the treatment of infectious diseases at a time when public health was a growing concern. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, isolation hospitals were established across Britain to control the spread of contagious illnesses such as smallpox, tuberculosis, scarlet fever, diphtheria, and later, influenza. Southampton, being a major port city with a high volume of international travel and trade, was particularly vulnerable to outbreaks of infectious diseases, making the need for an isolation hospital especially urgent.

By 1915, the Isolation Hospital in Southampton was playing a crucial role in managing public health amid the challenges of wartime. The First World War had brought an increased movement of people, including soldiers, sailors, and refugees, heightening the risk of disease outbreaks. Southampton was a key military embarkation point, with thousands of troops passing through on their way to and from the front lines. The hospital would have been on high alert, dealing not only with civilian cases of infectious diseases but also with military personnel who had contracted illnesses during their service.

Scarlet fever and diphtheria were among the most common reasons for admission in 1915. These diseases were highly contagious and potentially deadly, especially among children. The isolation hospital’s purpose was to remove infected individuals from the general population, preventing further spread. Patients were housed in separate wards or huts, often kept in strict quarantine for weeks at a time. The hospital staff, consisting of doctors, nurses, and orderlies, worked under challenging conditions, facing the risks of infection themselves while providing care with limited medical resources.

During this period, tuberculosis remained a persistent threat. Although specialized sanatoriums were the preferred treatment centers for TB, isolation hospitals sometimes admitted advanced cases when no other facilities were available. The treatment options in 1915 were still limited, relying primarily on rest, fresh air, and nutrition rather than effective antibiotics, which would not be developed until later in the 20th century.

Southampton’s Isolation Hospital would have also been preparing for potential outbreaks of typhoid fever, which was a concern in wartime due to the unsanitary conditions in military camps and among displaced populations. Soldiers returning from the trenches, where diseases spread rapidly, sometimes brought infections with them, requiring immediate quarantine and medical intervention. The role of the isolation hospital in controlling such outbreaks was vital to maintaining both civilian and military health.

One of the greatest challenges faced by the hospital in 1915 was the increasing strain on medical services due to the war. Many doctors and nurses had enlisted to serve on the front lines, leading to staff shortages. Those who remained at the hospital worked tirelessly to manage the growing number of cases, sometimes with inadequate supplies. There was also the ever-present fear of a more severe epidemic emerging, as had happened in previous decades with smallpox outbreaks.

Although the deadly influenza pandemic of 1918 was still a few years away, 1915 marked a time of heightened awareness of global health threats. The Southampton Isolation Hospital, like many others in Britain, was a frontline defense against diseases that could spread rapidly in a population already weakened by the hardships of war.

The hospital’s presence in Southampton was an essential part of the city's broader public health efforts. While its facilities were likely modest compared to modern medical centers, its impact was significant in preventing major outbreaks and ensuring that those affected received the care they needed while being kept separate from the healthy population.

By the mid-20th century, the need for dedicated isolation hospitals declined as vaccines, antibiotics, and improved sanitation reduced the prevalence of many infectious diseases. The hospital eventually closed or was repurposed as healthcare evolved. However, in 1915, it stood as a vital institution in Southampton’s fight against infectious diseases, working tirelessly to protect both its citizens and the military personnel passing through the city during one of the most challenging periods in history.

Ivy Jane Green was laid to rest on Monday the 18th day of October, 1915, at the Southampton Old Cemetery, located on Hill Lane, Southampton, Hampshire, England. Her final resting place is in Row B, Block 165, Grave Number 116, recorded under Interment Number 91679.

Surrounded by the serene and historic grounds of the cemetery, Ivy’s burial marked a moment of profound sorrow for her family. It was here, amidst the quiet, that Daniel, Emma, and their loved ones said their final goodbyes to their precious daughter, cherishing the memories of her life and mourning the loss of a young soul taken far too soon.

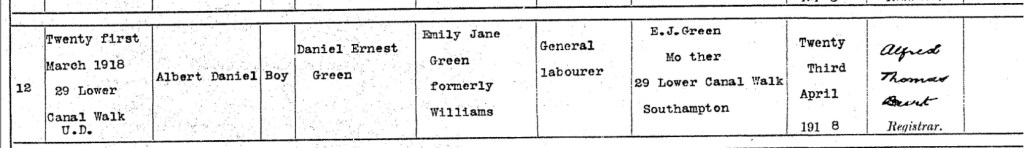

On an early spring day, Thursday the 21st day of March, 1918, Daniel Ernest and Emma Jane Green welcomed their son, Albert Daniel Green, into the world. He was born at their family home at Number 29, Lower Canal Walk, Southampton, Hampshire, England.

Albert’s arrival brought a glimmer of hope and renewal to the Green family, who just a few years earlier, in 1915, had suffered the devastating loss of their beloved daughter Ivy Jane. The memory of Ivy remained ever-present, and Albert’s birth was not only a source of immense joy but also a reminder of life’s resilience amidst sorrow.

On Saturday the 23rd day of April, 1918, Emma, known as Emily, officially registered Albert’s birth. She recorded her name as Emily Jane Green, formerly Williams, and listed her husband, Daniel Ernest Green, as a General Labourer. Their family address was again recorded as Number 29, Lower Canal Walk, Southampton.

The ever-familiar registrar, Mr. Alfred Thomas Burt, documented the event and noted the informant of Albert’s birth as E. J. Green, his mother, of 29 Lower Canal Walk. Albert’s arrival marked a bittersweet moment for the Greens, a symbol of the family’s enduring love and strength as they continued to build their legacy while holding Ivy’s memory close to their hearts.

On Sunday, the 19th day of June, 1921, Daniel Ernest Green, his wife Emily, and their children, Charlotte (using her middle name Emily), Rebecca (using her middle name Harrietta), Minnie, Ernest, George, Charles, and Albert, were residing at Number 29, Lower Canal Walk, Southampton, Hampshire, England. The family’s home was a six-room dwelling, providing space for their bustling household.

The 1921 census recorded Daniel Ernest Green as the head of the household. At 44 years and 3 months old, Daniel Ernest was noted as having been born in Southampton, Hampshire, England, around 1877. He was married to Emily Jane Green, who continued to be listed under her preferred name, Emily.

According to the census, Daniel Ernest worked as a labourer at the docks for Morland & Wolfe, a reflection of the vital role the docks played in Southampton’s economy and his enduring dedication to supporting his family.

The census also indicated that Daniel Ernest and Emily had five living children under the age of 16 in 1921. Their household, filled with youthful energy and daily challenges, showcased the resilience and strength of the Green family as they navigated the post-World War I era in Southampton.

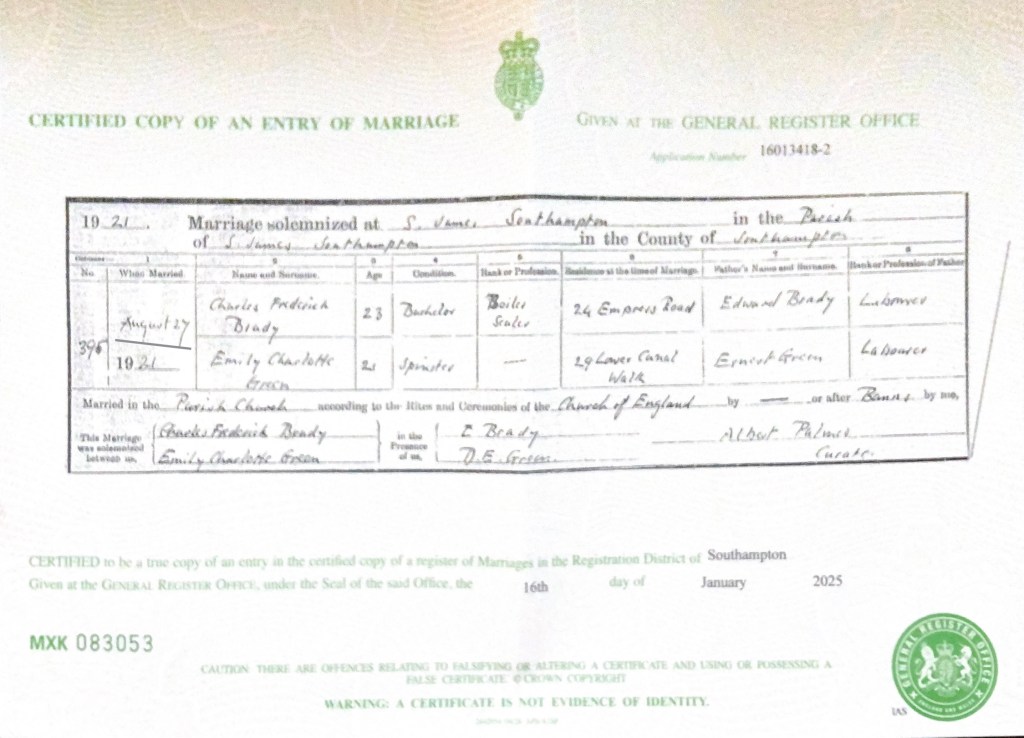

Daniel’s daughter, Emily Charlotte Green, aged 21 and residing at Number 29, Lower Canal Walk, joyfully joined in matrimony with Charles Frederick Brady, aged 23, of Number 34, Empress Road, on the memorable day of Saturday, the 27th day of August, 1921, at St. James in Southampton, Hampshire, England.

The bride, daughter of Ernest Green, a dedicated labourer, found her heart's companion in Charles, son of Edward Brady, also known for his hard work in labour. Their union was solemnized with L. Brady and Daniel Ernest Green (Emily’s father) as witnesses, marking the beginning of their shared journey in life together.

St. James' Church, located in the Shirley district of Southampton, Hampshire, England, has a rich history dating back to the 19th century. The original church in Shirley was recorded in the Domesday Book of 1085, but it was demolished in 1609 due to financial constraints. As the population grew, the need for a new place of worship became evident. Land was donated by Nathaniel Newman Jefferys, and with funding from the Church Building Society and private contributions, a new church was designed by local architect William Hinves. This new building was consecrated on August 20, 1836, by the Bishop of Winchester, despite unfavorable weather conditions. The church was described as a handsome structure in the later English style, featuring a square embattled tower. Initially accommodating 600 congregants, balconies were added in 1840 to increase the capacity to 1,080. Further enhancements included the addition of a church clock in 1875 and a new chancel in 1881. In 1994, the interior underwent significant renovations, with pews removed and the floor leveled and carpeted to create a more flexible worship space. Today, St. James' Church continues to serve the community, upholding its historical legacy while adapting to contemporary needs.

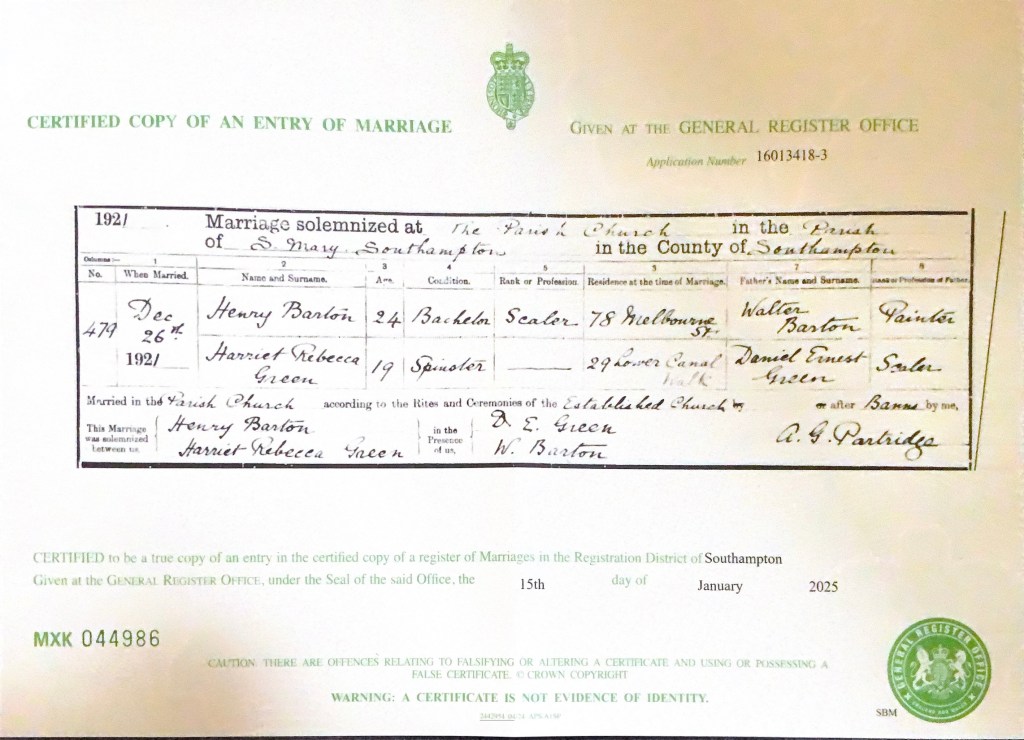

On Monday, the 26th day of December , 1921, Daniel’s daughter, Harriet Rebecca Green, a 19-year-old young woman from Number 29, Lower Canal Walk, exchanged vows with Henry Barton, a 24-year-old bachelor and skilled sealer from Number 78, Melbourne Street. Their wedding took place at the historic St. Mary’s Church in Southampton, Hampshire, England, marking the beginning of their life together as husband and wife.

As recorded by A.G. Partridge in their Entry of Marriage, Harriet was the cherished daughter of Daniel Ernest Green, a fellow sealer, while Henry was the beloved son of Walter Barton, a dedicated painter. To stand beside them on this momentous occasion, they chose none other than their own fathers, D. E. Green and W. Barton, to serve as witnesses, a heartfelt testament to the love and support of their families.

St. Mary's Church in Southampton, Hampshire, holds a significant place in the city's history, with its origins tracing back to around 634 AD. The initial establishment was a modest Saxon church in the ancient port town of Hamwic, founded during the mission of Saint Birinus to reintroduce Christianity to England. This early church governed a vast area, extending from the River Itchen to what is now Northam. Over time, the original structure fell into disrepair, leading to its reconstruction in the 12th century, reportedly under the directive of Queen Matilda, wife of Henry I. This second iteration was dedicated to 'Our Lady Blessed Virgin Mary' and became known as the 'great church,' underscoring its role as the mother church of Southampton, even though it was situated outside the city walls.

In 1549, much of the church was destroyed by government commissioners, possibly as a punitive action against the rector, William Capon, who resisted the confiscation of church lands. The chancel remained intact and continued to be used for services. By the early 18th century, the church was in a state of disrepair. Reconstruction efforts led to the building of a new nave in 1711 and a rebuilt chancel in 1723. As Southampton's population grew, especially with the opening of the docks in 1838, the church underwent further expansions and renovations to accommodate the increasing number of worshippers. Despite these efforts, the structure's quality declined, prompting campaigns for its replacement in the mid-19th century.

The current building, the sixth on this historic site, was constructed between 1954 and 1956, following the near-total destruction of its predecessor during the Southampton Blitz in World War II. Today, St. Mary's Church stands not only as a place of worship but also as a testament to the resilience and enduring faith of the Southampton community throughout the centuries.

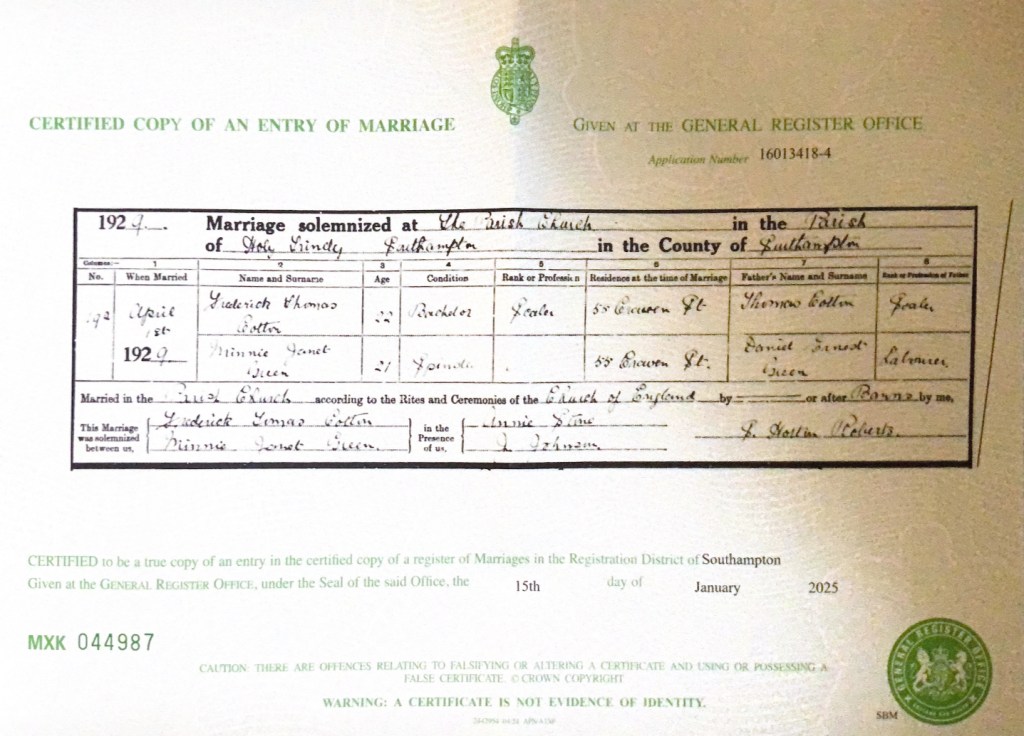

On Monday, the 1st day of April, 1929, Daniel’s daughter, Minnie Janet Green, a 21-year-old young woman, exchanged vows with Frederick Thomas Cotton, a 22-year-old bachelor, in a heartfelt ceremony at Holy Trinity Church in Southampton, Hampshire, England.

At the time of their marriage, the couple shared a residence at Number 55 Craven Street. As they stood before their loved ones, they recorded their fathers' names, Minnie as the daughter of Daniel Ernest Green, a hardworking labourer, and Frederick as the son of Thomas Cotton, a skilled sealer.

Surrounded by warmth and support, they were joined on their special day by their chosen witnesses, Annie Stone and J. Johnson. The ceremony was beautifully conducted by S. Hostin Roberts, marking the beginning of their journey as husband and wife.

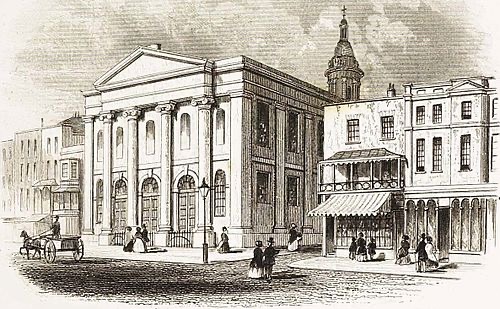

Holy Trinity Church in Southampton, Hampshire, has a rich history that reflects the city's evolving landscape and spiritual life. The church, sometimes referred to as Trinity Church, was built in 1827 on North Front as a chapel to the adjacent County Female Penitentiary.

In the Millbrook area of Southampton, another Holy Trinity Church was constructed between 1873 and 1880, designed by the architect Henry Woodyer. This church was built to serve the growing population in the Millbrook district.

Over the years, Holy Trinity Church in Millbrook has been a focal point for the community, witnessing significant events and changes. In August 2022, due to declining congregation numbers, the church was put up for sale, marking the end of an era for this historic building.

Today, the legacy of Holy Trinity Church in Southampton serves as a testament to the city's rich ecclesiastical history and the dynamic nature of its communities.

Daniels son, George Edward Green and Nellie Margaret Diaper pledged their love and commitment to each other on a spring day, Friday the 1st day of May, 1936. It was a simple yet significant ceremony at the Registry Office in Southampton, Hampshire, England, a moment that marked the beginning of their journey together as husband and wife.

George, just 23 years old at the time, had been working as a Stock Keeper of Chemist Sundries, a steady and respectable position. Nellie, at 19, was a domestic servant, no doubt hardworking and devoted. They came from different corners of Southampton, yet their love had brought them together. At the time of their marriage, George resided at Number 158, Shirley Road, while Nellie lived at Number 131, Beavis Valley Road, in Bevois Valley, a part of Southampton bustling with life.

As they stood before the registrar, they gave the names of the men who had shaped their lives, their fathers. George’s father, Ernest Daniel Green, was a stevedore, a man who toiled at the docks, ensuring the smooth movement of cargo in Southampton’s ever-busy port. Nellie’s father, Edwin Charles Diaper, was a labourer, another hardworking man whose efforts helped support his family.

The names of their witnesses, handwritten in the official record, are not entirely clear, but I have spent time carefully trying to decipher them. One appears to be Eliza Mary Blake, or perhaps Make. If it was indeed Blake, there is a strong possibility that she was Nellie’s maternal aunt, which would add a lovely familial touch to the occasion. Another witness, E. J. Green, likely stands for Emily Jane Green, George’s beloved mother, present to support her son on such an important day. Lastly, there is A. D. Green, which makes me wonder if it was Albert Daniel Green, George’s brother, standing proudly beside him as he embarked on this new chapter of his life.

How I wish I could step back in time to witness their joy, to see the smiles exchanged, the nervous excitement in their eyes, and the quiet promises whispered between them. Marriage is never just about the ceremony; it’s about the life built in the years that follow, the hardships faced together, and the unwavering love that stands the test of time. I can only hope that George and Nellie found happiness in their union, that their love carried them through life’s trials, and that the family surrounding them on that special day remained a source of strength and support.

What do you think? Do these names and connections make sense? I would love to hear your thoughts as we continue piecing together their story, bringing them back to life through the records they left behind.

On Sunday, the 12th day of June, 1938, Daniel’s son, Charles William Herold Green, a 23-year-old bachelor and rubber mixer of Number 12, Kingston Road, Off Park Road, Shirley, Southampton, pledged his love and devotion to Ethel Andrew Courtney, a 22-year-old kitchen maid of Number 54, Upper Canal Walk, Southampton. Their wedding took place at the beautiful All Saints Church in Southampton, Hampshire, England, marking the beginning of their life together as husband and wife.

As recorded in their Entry of Marriage, Charles was the son of Daniel Ernest Green, a dedicated stevedore, while Ethel was the beloved daughter of the late Robert Courtney, who had worked as a greaser (in the Royal Navy). To witness and support them on this significant day, they were accompanied by Charles’s brother, George Edward Green, and Joan Baston, who stood by their side as they exchanged vows and embarked on this new chapter of their lives.

All Saints' Church in Southampton, Hampshire, has a storied history that reflects the city's architectural and religious evolution. The original church on this site, known as All Hallows, was established during medieval times on land granted by King Henry II to the monks of St. Denys Priory. Over the centuries, this initial structure fell into disrepair. In the 1790s, a new church was constructed, and the name was changed to All Saints.

The new church, built between 1792 and 1795, was designed by architect John Reveley in a severely classical style, possibly modeled on the church of St. Martin-in-the-Fields in London.

This design choice marked a departure from traditional ecclesiastical architecture of the time, reflecting broader shifts in architectural tastes.

In the 20th century, the church underwent significant changes. A new mission room was opened on Winchester Road in 1891, dedicated to All Saints. This mission church served the community until 1946, when it was rededicated.

Throughout its history, All Saints' Church has been an integral part of Southampton's spiritual and community life, adapting to the changing needs of its congregation while maintaining its historical significance.

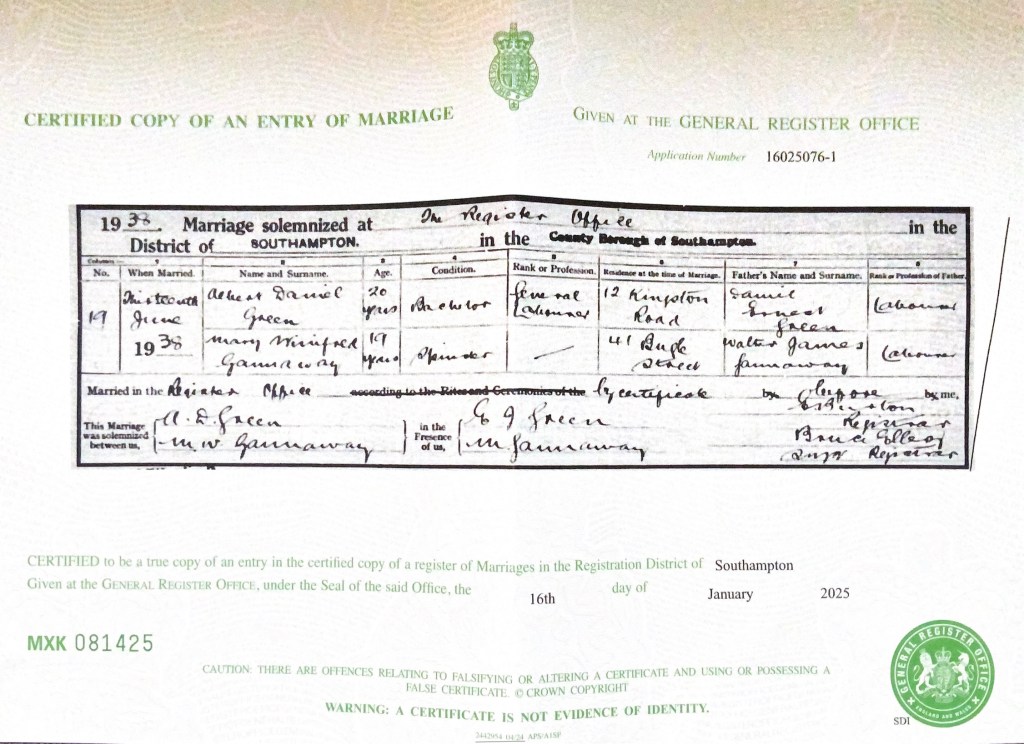

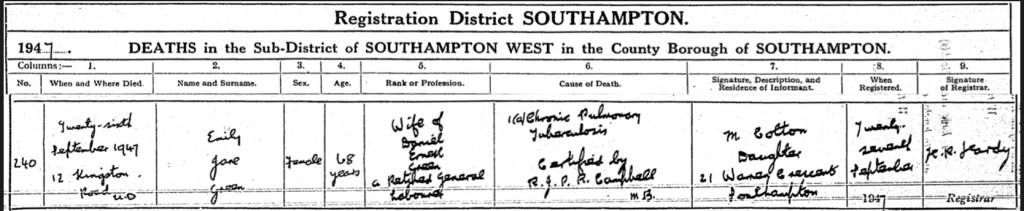

On Monday, the 13th day of June, 1938, Daniel’s son, Albert Daniel Green, a 20-year-old bachelor and hardworking general labourer of Number 12, Kingston Road, exchanged vows with Mary Winifred Gannoway, a 19-year-old spinster of Number 41, Bugle Street. Their union was solemnized at The Registry Office in Southampton, Hampshire, England, marking the beginning of their journey together as husband and wife.

In their Entry of Marriage, Albert proudly recorded his father as Daniel Ernest Green, a dedicated labourer, while Mary honored her father, Walter James Gannoway, who also worked as a labourer. Standing by their side on this special day were their chosen witnesses, E.J. Green and M. Gannoway, who shared in the joy of their heartfelt commitment to one another.

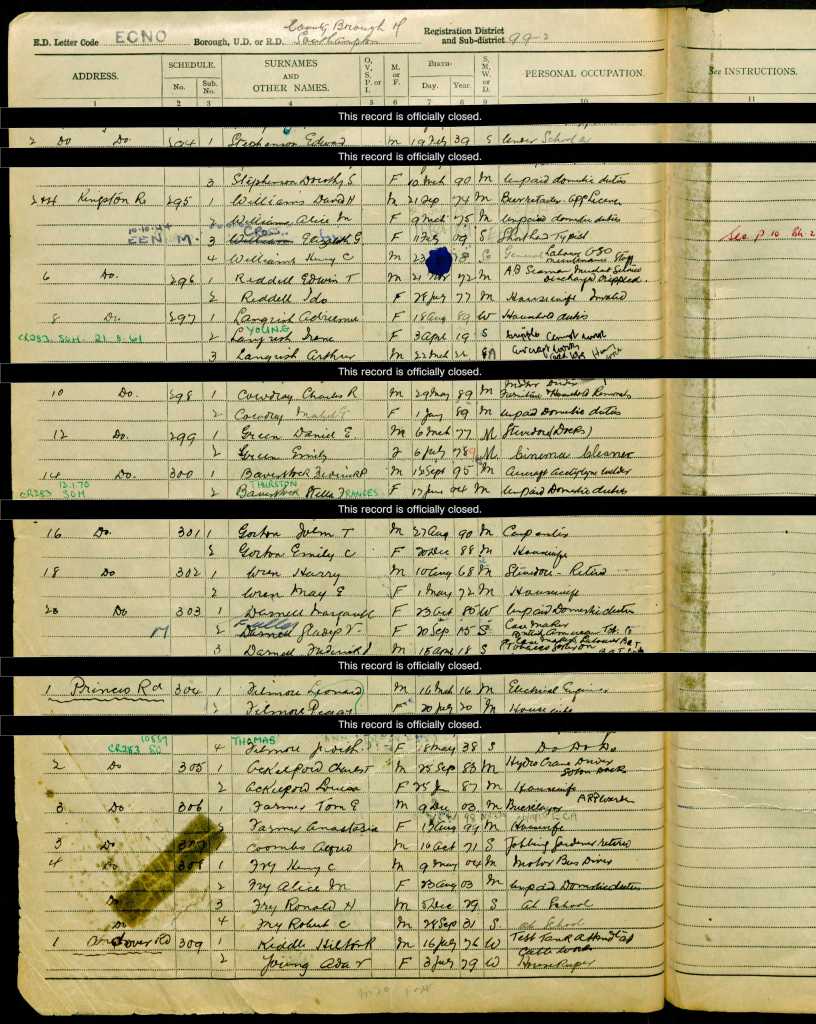

The pre-war 1939 register, taken on Friday, the 29th of September, 1939, finds Daniel Ernest Green and his wife, Emma (still known by her preferred name Emily), residing at Number 12, Kingston Road, Southampton, Hampshire, England.

In this moment of time, Daniel was working as a Stevedore at the Docks, while Emma worked diligently as a Cinema Cleaner.

The years leading up to this register entry were filled with tremendous challenges and personal loss for the Green family. Daniel and Emma, who had lived through the hardships of the First World War, carried with them the painful scars of a past shaped by grief, sacrifice, and survival. Their family had already endured the untimely deaths of loved ones, including the heartbreaking loss of their young daughter, Ivy Jane, to fever. In the midst of it all, they had also seen their children grow, marry, and build their own families.

Now, as the world stood on the brink of yet another devastating conflict, the Greens, like many others, were no strangers to the fear and uncertainty that loomed on the horizon.

Having already survived the horrors of the First World War, where so many lives were lost and so much was shattered, they feared the coming storm and what it might mean for their future. The war had taken its toll on them all, and they knew all too well the trauma, the heartache, and the cost of conflict.

As the darkness of war once again gathered over Europe, Daniel and Emma, despite the years and the toll it had taken on them, remained resilient. Their steadfast love for each other and their children had been a constant source of strength. Their story, like so many others, was one of survival, a testament to their enduring will to face adversity with courage and love in the face of unimaginable hardships.

The future was uncertain, but the Green family’s legacy was one of resilience, strength, and the hope that, despite the darkness of the times, they could emerge on the other side. They had already lived through one war, and they would face the coming trials with that same courage, knowing the value of family, and the unbreakable bond that connected them all.