Family history is more than a collection of names and dates, it is the foundation of who we are, the story of those who came before us, and the legacy we pass on to future generations.

To understand our own identities, we must look to the lives of our ancestors, for their struggles, triumphs, and experiences continue to shape us in ways we may not even realize.

This is especially true when considering the family of one’s spouse, whose lineage is carried forward in our children. The DNA of those who lived generations before still runs through their veins, connecting the past to the present in an unbroken chain of heritage. In exploring their stories, we not only honor their memory but also provide our children with a deeper understanding of where they come from.

In that spirit, The Life of Robert McIntyre Wallace 1898–1925 Through Documentation, seeks to illuminate the journey of one such ancestor, a man whose life, though brief, left an indelible mark. Through carefully preserved records, and historical accounts, we uncover the world in which he lived, the challenges he faced, and the legacy he left behind.

By delving into the life of Robert McIntyre Wallace, we do more than preserve history, we reconnect with a past that still echoes in our present. His story is not just his own, it belongs to his descendants, to his family, and to the generations yet to come.

So without further ado, I give you,

The Life Of

Robert McIntyre Wallace

1898–1925

Through Documentation.

Welcome back to the year 1898, Southampton, Hampshire, England.

The world around you hums with the sounds of industry and progress, yet life remains shaped by tradition and class. Queen Victoria has sat upon the throne for over sixty years, a steadfast symbol of the British Empire’s strength. Her influence is everywhere, from the rigid moral codes of society to the unyielding belief in progress and empire. The Prime Minister, Robert Gascoyne-Cecil, 3rd Marquess of Salisbury, leads the government, his Conservative Party maintaining a firm grip on power. Parliament debates matters of imperial expansion, social reform, and the ever-widening gap between the wealthy elite and the struggling poor.

Southampton is alive with activity. As a major port town, it is a gateway to the world, its docks bustling with steamships carrying goods and passengers to and from the far reaches of the Empire. The air is thick with the scent of coal smoke and salt, mingling with the aroma of fresh fish from the market and the less pleasant stench from open sewers in the poorer quarters. The sanitation system remains inconsistent, better in affluent areas, but for the working poor, it is a daily battle against filth and disease.

Fashion is a statement of class and propriety. The wealthy parade in finely tailored suits and elaborate gowns adorned with lace, ribbons, and high collars. For men, starched collars and waistcoats remain essential, while women wear tightly laced corsets beneath layers of fabric, despite changing trends that hint at slightly more practical designs. The working class dresses simply, men in sturdy trousers and caps, women in plain dresses, often patched and worn from years of use. For the very poor, clothing is whatever can be afforded or mended, often handed down and threadbare.

Transportation is a mixture of old and new. The streets are filled with horse-drawn carriages, omnibuses, and carts, their wooden wheels rattling over cobblestone roads. But change is coming, electric trams are beginning to appear in some cities, and the first automobiles, though still a rare sight, hint at the revolution to come. Railways connect Southampton to London and beyond, ensuring goods and people can move with speed unimaginable just decades earlier.

Energy, heating, and lighting vary greatly depending on one's wealth. Gas lighting is common in wealthier homes and on the streets, casting a dim, flickering glow after dark. The very rich may have the latest marvel, electric lighting, but most homes still rely on oil lamps and candles. Heating is provided by coal fires, their warmth a necessity against England’s damp chill. In the grand townhouses of the wealthy, fireplaces are large and ornately decorated, always tended by servants. In working-class homes, a single fireplace often serves as the only source of warmth for an entire family, while the poorest huddle under blankets, hoping to ward off the cold.

Food reflects one’s status in life. The upper classes dine on fine meats, game, and exotic fruits imported from the empire, their tables adorned with silverware and crystal. Afternoon tea is an elegant affair, with delicate sandwiches and rich pastries. The working class subsists on bread, cheese, and cheap cuts of meat, often stews stretched to feed a large family. The poorest rely on what little they can afford, stale bread, scraps, and sometimes nothing at all. The rise of workhouse kitchens provides a last, grim option for those who have nowhere else to turn.

Entertainment provides an escape from the hardships of life. The music halls of Southampton are lively and boisterous, filled with the sounds of popular songs, bawdy humor, and theatrical performances. The wealthier classes enjoy opera, theatre, and social gatherings in exclusive clubs. The novel is a beloved pastime, with the works of H.G. Wells, Arthur Conan Doyle, and Thomas Hardy captivating readers. For the poor, street performers and public houses offer fleeting moments of joy, though many drown their sorrows in ale and gin.

The atmosphere is one of contrast. For the rich, England is a land of prosperity, expansion, and innovation. For the poor, life remains a daily struggle against hunger, disease, and the rigid structures that keep them in their place. The class divide is sharp and unrelenting. The aristocracy and upper middle class live in luxury, their wealth built upon industry and empire. The working class toils in factories, shipyards, and domestic service, their lives marked by long hours and little reward. The poor, crammed into overcrowded slums, fight for survival against conditions that breed illness and despair.

Gossip flows as freely as the Thames. The newspapers are filled with talk of scandal, royal intrigues, political maneuvers, and society’s latest indiscretions. In drawing rooms, ladies whisper about the latest fashions from Paris and who has married well (or scandalously). In the pubs, men debate the Boer War, the latest crime reports, and whether change will ever come for those at the bottom.

Historical events shape the year. Britain’s imperial reach remains vast, though murmurs of unrest in the colonies grow louder. The conflict in Sudan ends with the Battle of Omdurman, a brutal display of British military might. The Fashoda Incident, a tense standoff between Britain and France in Africa, threatens war but ultimately ends in diplomatic resolution. At home, social reformers push for better working conditions and rights for women, though true change remains distant.

This is 1898, a year of contrasts, progress and hardship, wealth and poverty, tradition and change. Southampton, like the rest of England, stands on the edge of a new century, uncertain of what the future will bring.

My husband’s Great Grandfather, Robert Wallace, came into the world on a cold winter’s morning, Thursday the 20th day of January 1898, at Number 22, Exmoor Road, Southampton, Hampshire, England. His first breaths were drawn in a time of industry and change, in a bustling port town where steamships lined the docks, their whistles piercing the air, and the streets were alive with the rhythms of daily life.

It was his father, John, who made the journey to officially record his son’s birth, walking through the streets of Southampton to do his duty as a proud father. On Wednesday the 9th day of February 1898, he stood before Harry George Whitchurch, the registrar, and spoke the details that would forever document the arrival of his son. He declared that Robert was born to him, John McIntyre Wallace, a Marine Engineer, and to his wife, Elizabeth Maud Wallace, formerly Clark. Both resided at Number 22, Exmoor Road, their home now filled with the cries of their newborn son, a child whose life was only just beginning.

And yet, no baptismal name was recorded. Whether this was an oversight, a deliberate choice, or simply a matter to be addressed at a later date, remains a mystery lost to time. What is certain, though, is that Robert’s birth was not just another entry in the registrar’s book, it was the start of a life, a story that would shape generations to come. His blood runs through my children’s veins, a testament to the unbroken thread of ancestry, binding past to present, and ensuring that his name, his existence, is not forgotten.

The surname Wallace carries a rich tapestry of history and meaning. Its origins are deeply rooted in the Scottish-English Borderlands, particularly in the regions of Ayrshire and Renfrewshire. The name is believed to derive from the Old French term "waleis," meaning "foreigner" or "Welshman," a reference to the Strathclyde Britons who were considered outsiders by the Anglo-Norman settlers.

The Wallace family is perhaps most famously associated with Sir William Wallace, the 13th-century Scottish knight who became a central figure in Scotland's fight for independence. His legacy has immortalized the name, embedding it deeply into Scottish national identity.

The Wallace clan crest is emblematic of the family's storied past. It features a dexter arm in armor, brandishing a sword, emerging from a crest coronet adorned with strawberry leaves. This imagery symbolizes strength, readiness, and a warrior spirit. The accompanying motto, "Pro libertate," translates to "For liberty," reflecting the clan's enduring commitment to freedom.

The Wallace surname has traversed centuries, carrying with it tales of valor, resilience, and a steadfast dedication to liberty. Today, it remains a proud emblem for descendants and bearers of the name.

Exmoor Road in Southampton, Hampshire, England, is a residential street situated within the SO14 postal district. The area is characterized by its proximity to the Royal South Hampshire Hospital, a significant landmark established in the mid-19th century. The hospital's chapel once stood at the eastern end of the complex, near the junction of Fanshawe Street and Exmoor Road, indicating the street's longstanding association with the hospital's history.

Historically, the surrounding neighborhood, known as Nicholstown, comprises residential streets interspersed with small shops and services. The Royal South Hampshire Hospital serves as the central feature of this area, highlighting the community's blend of residential and healthcare facilities.

In terms of property transactions, Exmoor Road has seen various sales over the years. For instance, 1 Exmoor Road, a terraced freehold property, was sold on 15 December 2015 for £192,500. Similarly, 17 Exmoor Road, another terraced freehold property, changed hands on 25 April 2022 for £236,500.

The street is part of the Bevois ward within the Southampton Test constituency. The area is predominantly urban, with a mix of housing types and a diverse community. The presence of the Royal South Hampshire Hospital nearby underscores the area's role in providing essential healthcare services to the residents of Southampton.

While specific historical events directly tied to Exmoor Road are limited, its location within Southampton places it amidst a rich tapestry of the city's maritime and industrial heritage. The street's evolution reflects broader urban development patterns, influenced by Southampton's growth as a significant port city.

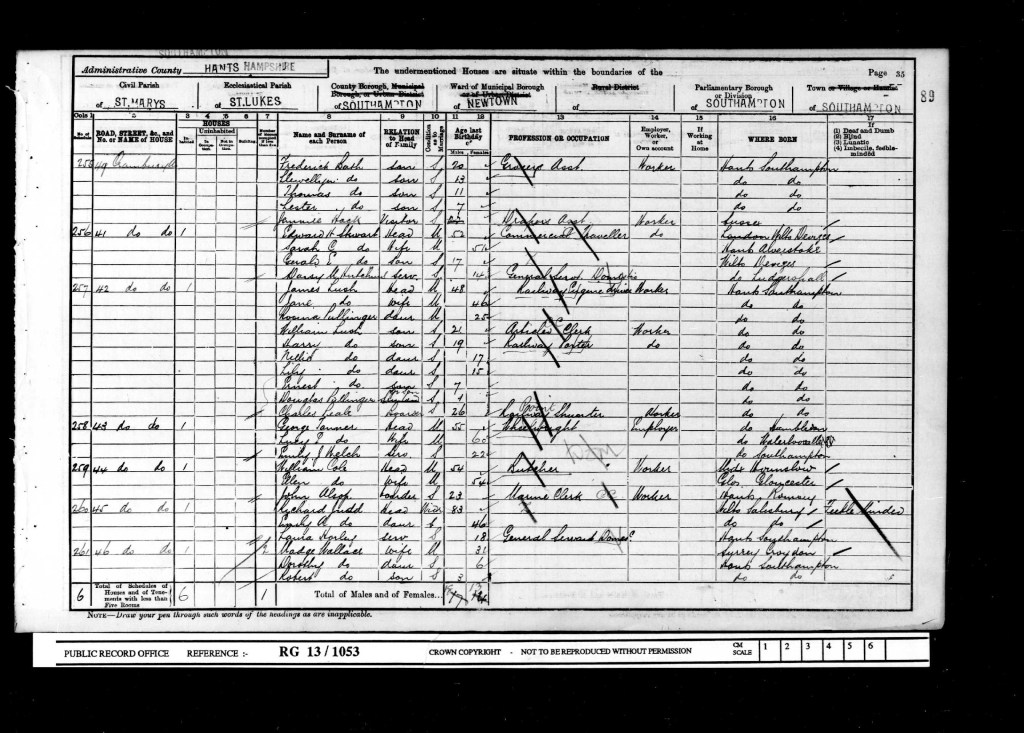

On Sunday, the 31st day of March 1901, as dusk settled over Southampton and the town’s streets quieted in the glow of gas lamps, a young Robert Wallace was tucked away in a home at Number 46, Cranbury Avenue, St Mary’s, Southampton, Hampshire, England. It was the eve of the 1901 census, a moment in time carefully recorded by clerks and enumerators, preserving the details of thousands of lives across England.

In the house with him were his mother, Maude, though, for reasons unknown, she was recorded as Madge, and his sister, Dorothy Helen. Though the census listed no occupations for the family, their presence on Cranbury Avenue suggests a certain level of comfort. The area, part of St Mary’s, was home to a mix of residents, some living in modest terraces, others in larger Victorian homes that lined the well-established streets.

Yet, there was a notable absence. Robert’s father, John McIntyre Wallace, was not listed in the household. His name was missing from the census return, yet Maude was still recorded as a married woman, not a widow. This small but significant detail raises questions, was John simply away that night, perhaps traveling for work as a marine engineer, his occupation likely keeping him at sea or in another port town? Or was there something more to his absence, a deeper story left untold by the census form?

For Robert, just three years old, the world within those walls would have been small and familiar. His mother and sister were the constants in his life, guiding him through the earliest years of childhood. The house, though now a historical address, once held their laughter, their routines, their struggles, and their quiet, unspoken hopes for the future.

As the census enumerator moved from door to door, recording the details of families across Southampton, the Wallace household was just another entry in a vast record of England at the turn of the century. And yet, over a hundred years later, those simple details, a name slightly altered, a missing father, a mother standing in the quiet uncertainty of her husband’s absence, still spark curiosity and whisper fragments of a story waiting to be pieced together.

Cranbury Avenue, located in the St Mary's district of Southampton, has a history that stretches back to the mid-19th century. The street first appeared on the Town Map of 1845-46, depicted with a few houses, though it remained unnamed at that time. Its eventual naming was inspired by Cranbury Park, a stately home and country estate situated in the parish of Hursley, near Winchester. Cranbury Park is notable for having been the residence of Sir Isaac Newton and later the Chamberlayne family, whose descendants continue to occupy the estate into the 21st century.

The St Mary's area, where Cranbury Avenue is situated, holds significant historical importance for Southampton. Originally, it encompassed much of the Saxon town of Hamwic, a bustling settlement that thrived in the early medieval period. Following the 11th century, the area transitioned back to farmland and remained so until the 18th century. In the post-World War II era, council estates were developed in the vicinity, including the Golden Grove estate built in the 1960s.

A notable landmark near Cranbury Avenue is St Luke's Church, erected between 1852 and 1853. Designed by architect John Elliott of Chichester, the church was built in a straightforward neo-Gothic style and is situated on the south side of the street. The establishment of St Luke's Church coincided with the formation of its parish in 1853, which was carved out from the larger parish of St Mary's to serve the burgeoning Newtown area of Southampton.

Over the years, Cranbury Avenue has evolved, reflecting the broader changes within Southampton. Today, it is a residential street characterized by a mix of housing types, including flats and terraced houses. The area is known for its diverse community and proximity to various amenities, such as schools, healthcare facilities, and places of worship. The street's historical roots and its connection to significant local landmarks contribute to its unique character within the city.

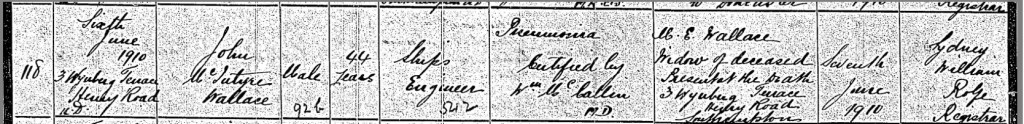

On Monday, the 6th day of June, 1910, a profound sorrow settled over the home at Number 3, Wynberg Terrace, Henry Road, Shirley, Southampton. Within those walls, 44-year-old John McIntyre Wallace, a dedicated ships engineer, took his final breath, succumbing to pneumonia. The illness, relentless and unforgiving, had drained the life from a man who had likely spent his years working tirelessly in the world of maritime engineering, a profession demanding both skill and endurance.

At his bedside was his devoted wife, Maude Elizabeth Wallace, who bore witness to his passing. The weight of grief she must have felt in that moment is almost unimaginable, their shared years, their home, their children, all now overshadowed by an aching absence. The following day, on Tuesday, the 7th day of June 1910, despite her heartache, Maude found the strength to fulfill the necessary yet devastating duty of registering her husband's death. With quiet resolve, she made her way to the registrar’s office in Southampton, where Sydney William Rolfe, the registrar in attendance, carefully recorded the details into the official death registry.

Dr. W. McCallin had certified pneumonia as the cause of death, a cruel and common affliction of the time, particularly among those exposed to harsh working conditions or extended periods at sea. For a ships engineer like John, whose livelihood depended on the unforgiving rhythm of the maritime world, illness could strike without warning, and medical interventions were often too little, too late.

In those moments, as Maude signed her name in the registrar’s book, she was not only documenting a legal fact but closing a chapter in her life that had once been filled with the warmth of companionship. Now a widow, she faced an uncertain future, left to raise their children, Dorothy and young Robert, without the guiding presence of the man who had stood beside her. Their home, once a place of security and family life, now carried the echoes of loss.

Though John McIntyre Wallace’s name was now set in ink within the registry, his true legacy lived on in the family he left behind, in the son who bore his name, and in the love and devotion of the woman who had held his hand until the very end.

Wynberg Terrace, situated on Henry Road in the Shirley area of Southampton, Hampshire, England, is a residential street with a rich history that reflects the broader development of the region. The name "Wynberg" is believed to be derived from the town of Wynberg in South Africa, a nod to the historical connections between the British Empire and its colonies.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Southampton experienced significant urban expansion, with areas like Shirley undergoing transformation from rural farmland to densely populated residential neighborhoods. This period saw the construction of numerous terraced houses, including those on Henry Road, to accommodate the growing population. Wynberg Terrace, with its distinctive architecture, became a notable part of this development, providing homes for many working-class families.

The architecture of Wynberg Terrace is characteristic of the era, featuring rows of terraced houses with shared walls, modest frontages, and simple yet functional designs. These homes were built to meet the housing demands of the time, offering affordable living spaces for the working population. Over the years, the area has seen various modifications and renovations, but the original character of the terrace remains evident.

On a somber Thursday, the 9th day of June 1910, John McIntyre Wallace was laid to rest in Southampton Old Cemetery, his final resting place marked in Block 182, Number 18, Internment Number 82802. It was a day of mourning for those who loved him, a day when the weight of loss settled heavily on the shoulders of his widow, Maude Elizabeth, and his young son, Robert.

Southampton Old Cemetery, a place of history and remembrance, became the sacred ground where John’s life came to its quiet end. Established in 1846, the cemetery held within it the stories of generations, and now, John’s name was among them. As the earth closed over him, it was not just the passing of a husband and father but the end of a chapter in the Wallace family’s history.

For Maude, grief must have been overwhelming. Left a widow, she had to carry on, to navigate a world without her husband, to raise her children alone. For Robert, just 12 years old at the time, losing his father would have been a defining moment, a loss that no child should have to endure.

Though life carried on, and years turned into decades, John’s grave would not remain his alone. Time would bring his son, Robert, back to him, and later, his beloved wife, Maude. The same ground that first received John in 1910 would eventually hold them all, a family reunited in rest. Their names, their lives, and their love would endure not just in the records of history but in the earth of Southampton Old Cemetery, where their story continues to be remembered.

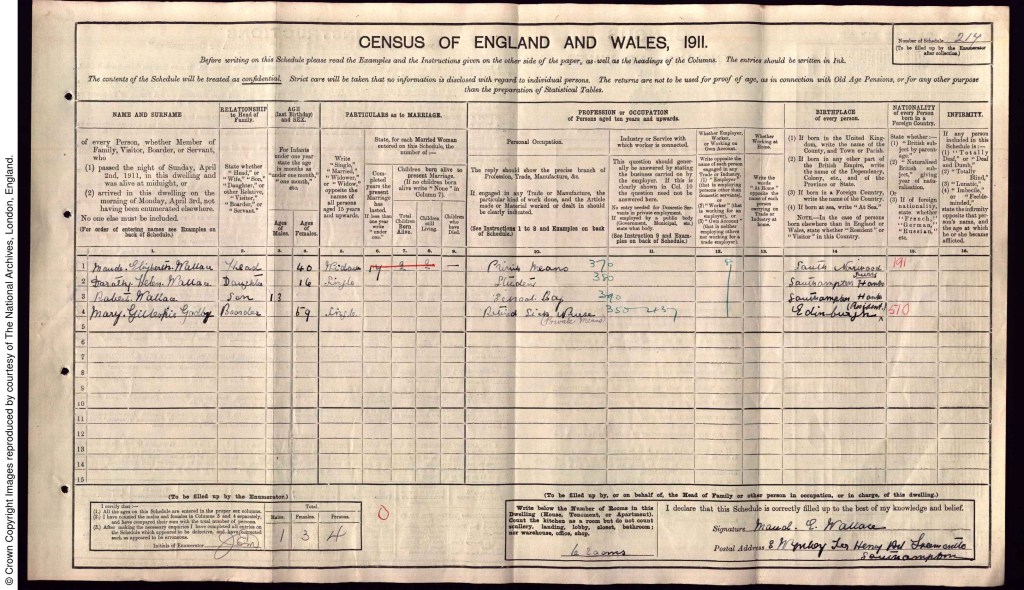

On the eve of the 1911 census, which was completed on Sunday, the 2nd of April 1911, Robert Wallace, his mother Maude Elizabeth, his sister Dorothy Helen, and their companion Mary Gillespie Godby were settling into their six-room home at Number 3, Wynberg Terrace, Henry Road, Shirley, Freemantle, Southampton. The house was a quiet place, marked by the absence of Robert's father, John, who had passed away the previous year. Maude, now a widow, was doing her best to keep the family afloat, living off private means, just as Mary Gillespie Godby, a retired sick nurse, did as well.

Mary, at 59, had outlived her career but not the independence she had earned. Her presence in the household added another layer of complexity to their family dynamic, and her story was quietly intertwined with theirs as she contributed both to the household's financial stability and its emotional strength. While Mary’s days of nursing were behind her, the knowledge she had gathered over the years may have offered comfort and a sense of security to the family.

Robert, only 13 at the time, was still a schoolboy, likely navigating the world with an innocent curiosity, still learning and growing. His sister Dorothy, older than Robert, was listed as a student, a young woman at the threshold of her own education and future.

Despite the challenges they had faced with the passing of John, their home at Wynberg Terrace carried a sense of continuity. It was a space where they, with their different paths, some shaped by loss and others by opportunities, came together, forging a new life. The walls of Number 3 would have held their stories, from the quiet moments of study and reflection to the shared laughter of a family who, even in the face of grief, were determined to move forward.

In the closing months of 1916, as the world remained gripped by the turmoil of the First World War, Maude Elizabeth Wallace took a step towards a new chapter in her life. After six years of widowhood, she found companionship once more in George W. Allcock, and their marriage was solemnized in the December quarter of that year, within the district of Southampton, Hampshire.

For Maude, this union may have been one of both comfort and necessity. Since the passing of her first husband, John McIntyre Wallace, in 1910, she had navigated the difficult path of raising her children alone. Though her son Robert was now a young man, forging his own path and starting a family, and her daughter Dorothy was growing into womanhood, the weight of loss and the uncertainties of wartime life must have lingered.

George W. Allcock entered Maude’s life at a time when stability was precious. Whether theirs was a love match or one built on shared understanding, he became the man she would walk beside in the years to come. His presence may have brought Maude a renewed sense of security, easing the burdens she had carried alone for so long.

As they exchanged vows in Southampton, their union was quietly recorded, a simple yet significant entry in the district’s marriage register. But beyond the official record, this moment marked a shift in Maude’s life, a turning point where grief gave way to the possibility of companionship once more. Though the years ahead remained uncertain, as war raged on and the world changed rapidly, Maude had taken this step forward, choosing hope, choosing a future, and choosing to share the rest of her journey with George.

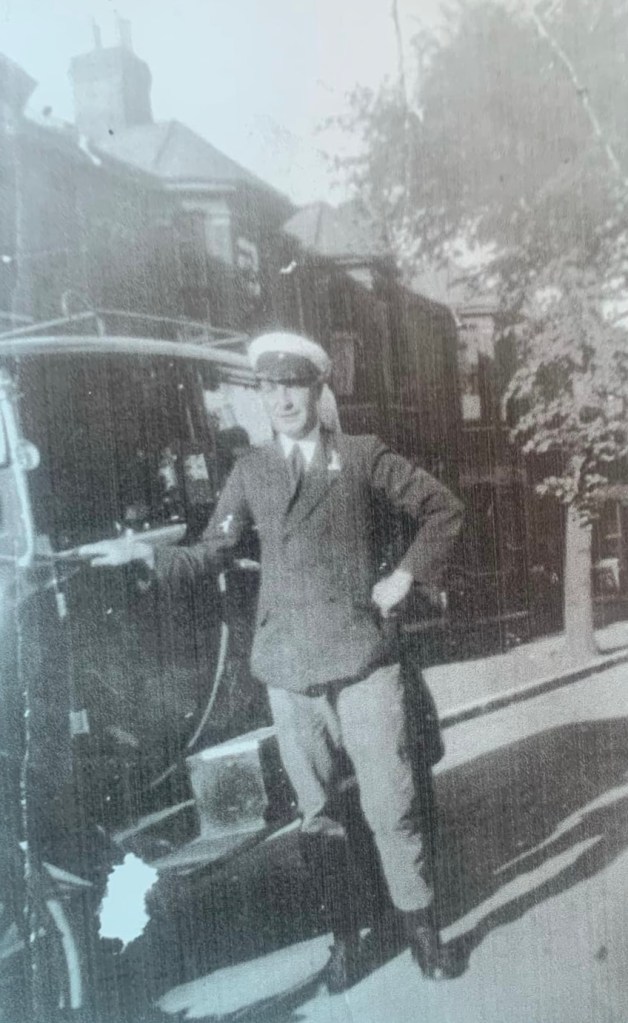

In the summer of 1917, at just 19 years old, Robert Wallace found himself at the center of a serious accident that would make its way into the pages of the Hampshire Advertiser. It was a time when motor vehicles were still relatively new to the streets, and driving was not without its dangers.

The incident took place on Monday the 6th day of August 1917, at the junction of Redbridge and Wimpson Roads in Millbrook. Robert, a young man already trusted with the responsibility of driving, was at the wheel when a split-second decision changed the course of that day. In an attempt to avoid another car, he swerved, but fate was unkind, the vehicle crashed violently into a fence. Seated in the rear were Mr. and Mrs. Reeves, passengers who had no time to brace for impact. The force of the collision threw them from the vehicle, leaving them with severe injuries.

In the aftermath, there must have been chaos, bystanders rushing to help, the wreckage of the damaged car, and the distress of those involved. The injured couple was quickly taken to the Royal South Hants and Southampton Hospital, where they were detained for treatment.

For Robert, this moment would not have been easily forgotten. Though the newspaper article makes no mention of blame, the weight of the event must have sat heavily on his shoulders. The responsibility of being behind the wheel, the horror of seeing his passengers flung from the car, and the uncertainty of their recovery, these were burdens he had to carry.

The Hampshire Advertiser, reported the accident on Saturday, the 11th of August, 1917, a stark reminder of how unpredictable life could be. Whether Robert faced any further consequences from the incident remains unknown, but what is certain is that this moment, captured in ink on the printed page, became a part of his story, a story of a young man navigating not just the roads of Southampton, but the challenges of adulthood in a rapidly changing world.

The Hampshire Advertiser newspaper article reads as follows,

MILEBROOK.

A serious motor collision occurred on Monday at the Junction of the Redbridge and Wimpson Roads, Millbrook, when a motor car driven by Robert Wallace, of Oxford-avenue, Southampton, in endevouring to avoid another car, crashed into a fence, and Mr. and Mrs. Reeves, who were seated in the rear, were violently flung out, both sustaining severe injuries.

They were conveyed to the Royal South Hants and Southampton Hospital and detained.

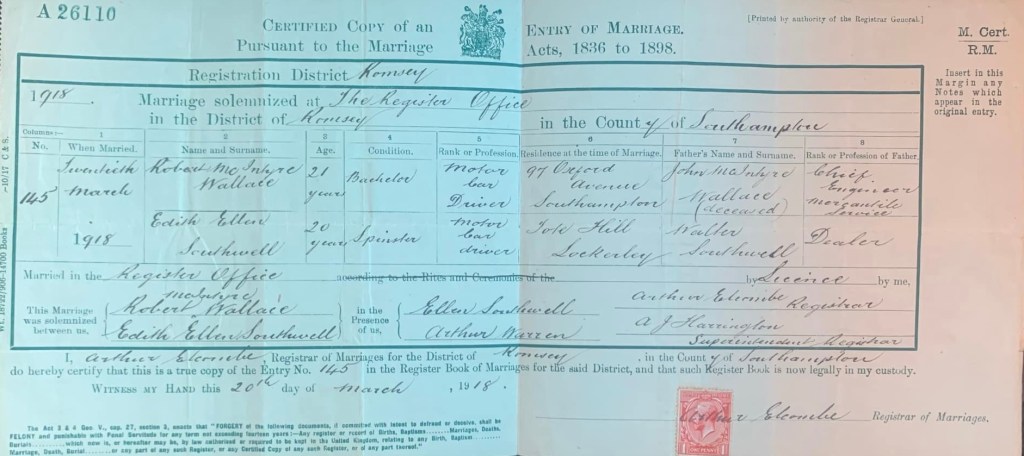

Robert, just 21 years old, a bachelor residing at Number 97, Oxford Avenue, Southampton, had already experienced much in his young life. The loss of his father, John McIntyre Wallace, a chief engineer in the mercantile service, had undoubtedly shaped him, yet here he was, stepping forward into a new future. Edith, a 20-year-old spinster from Tote Hill, Lockerley, was beginning this journey alongside him, bringing with her the strength and resilience of her own upbringing as the daughter of Walter Southwell, a dealer by trade.

Their marriage was solemnized by Arthur Elcombe, the registrar, and A. J. Harrington, the superintendent, who carefully recorded every detail in the Marriage Register. Among the facts and formalities was a notable detail, both Robert and Edith were working as motor car drivers at the time of their marriage. In an era when automobiles were still a luxury and driving was far from a common profession, particularly for a young woman, this spoke volumes about their independence and modern outlook on life. They were part of a generation embracing change, not only in their personal lives but in society as a whole.

The ceremony was witnessed by Ellen Southwell and Arthur Warren, two individuals who stood beside them as they pledged their vows. I believe Ellen was a relative, Edith’s mother, there to offer support, while Arthur Warren may have been a friend or colleague. Whoever they were, they played a small but significant role in sealing this union, bearing witness to a love that had brought these two young souls together.

As they walked away from the register office, newly married, their hands and futures intertwined, the world outside continued to change. War still raged, the future was uncertain, but in that moment, Robert and Edith had created something unshakable, a promise to face whatever came next, together.

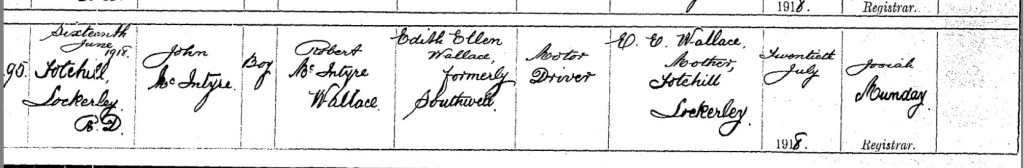

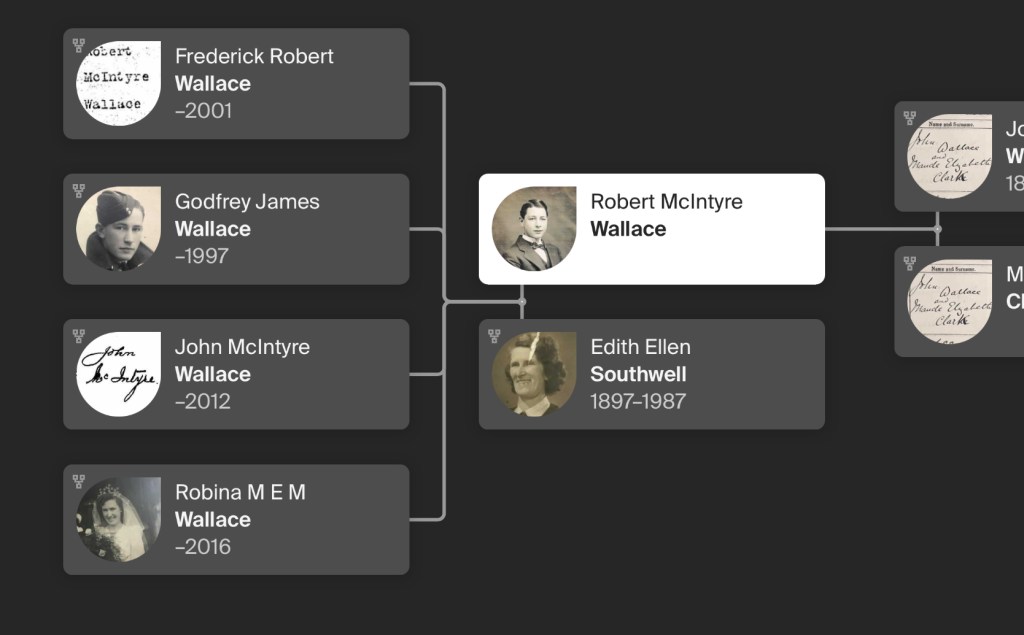

On a summer’s day, Sunday the 16th day of June 1918, the cry of a newborn filled the air at Totehill, Lockerley, Hampshire. In that moment, Robert and Edith Wallace welcomed their firstborn son, John McIntyre Wallace, into the world. Born amidst the final year of the Great War, his arrival was not just a beacon of new life but a symbol of hope and continuity in a time of great uncertainty.

For Edith, cradling her son in the warmth of their home, it must have been a moment of profound joy and quiet reflection. Just three months earlier, she had stood beside Robert as they exchanged vows, beginning their journey as husband and wife. Now, with their infant son in her arms, their little family was complete in a way she could never have imagined so soon.

A month later, on Saturday the 20th day of July, 1918, Edith made her way to Romsey to officially register John's birth. It was a task undertaken by countless mothers before her, yet for her, it was deeply personal, her firstborn, her son, now officially recognised in the records of time. At the register’s desk, Josiah Bunday carefully inscribed the details: John McIntyre Wallace, son of Robert McIntyre Wallace, a Motor Driver, and Edith Ellen Wallace, formerly Southwell. Their residence, Totehill, Lockerley, a place that had now become the birthplace of a new generation.

John’s name carried a legacy within it, a tribute to the grandfather he would never meet, John McIntyre Wallace. In bestowing this name upon their son, Robert and Edith honored the past while embracing the future, ensuring that the name and memory of the man who had come before him would live on through his grandson.

As Edith left the register’s office that day, the weight of responsibility and love must have settled deep within her. The world was still a place of turmoil, but within the walls of their home in Totehill, there was love, resilience, and the promise of a future shaped by the family they were building together.

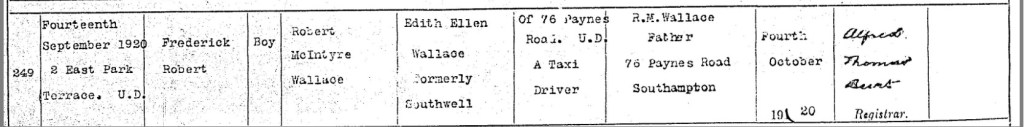

On Tuesday, the 14th day of September, 1920, at Number 2, East Park Terrace, Southampton, the Wallace family grew once more as Robert and Edith welcomed their second son, Frederick Robert Wallace, into the world. Two years had passed since the birth of their firstborn, John, and now, in the heart of Southampton, another chapter of their family story had begun.

Frederick’s arrival marked a new stage in their journey, one that now saw them settled in Southampton, away from the quieter rural setting of Totehill, Lockerley, where John had been born. Life in the city was different, busier, filled with movement and change. Robert, now working as a taxi driver, had embraced the fast-paced nature of urban life, navigating the streets of Southampton to provide for his growing family. Edith, ever devoted, now had two little boys to care for, their laughter and cries filling the rooms of their home at Number 76, Paynes Road.

On Monday, the 4th day of October, 1920, Robert took on the solemn yet proud duty of registering his son’s birth in Southampton. Walking into the registrar’s office, he stood before Alfred Thomas Bunt, who recorded the details with precision: Frederick Robert Wallace, son of Robert McIntyre Wallace, a taxi driver, and Edith Ellen Wallace, formerly Southwell. The family’s residence was officially listed as Number 76, Paynes Road, Southampton, a home that now carried the memories of a growing family, the echoes of tiny footsteps and the warmth of a mother’s care.

Frederick’s name bore significance, a strong and steady name, mirroring the resilience of the Wallace family. Though he had only just entered the world, he was already part of a legacy, one shaped by the love of his parents, the protective presence of his older brother, and the industrious spirit of the city they now called home. As Robert left the registrar’s office that day, he did so as a father of two, a man building a life not just for himself, but for the sons who would one day carry the Wallace name forward into the future.

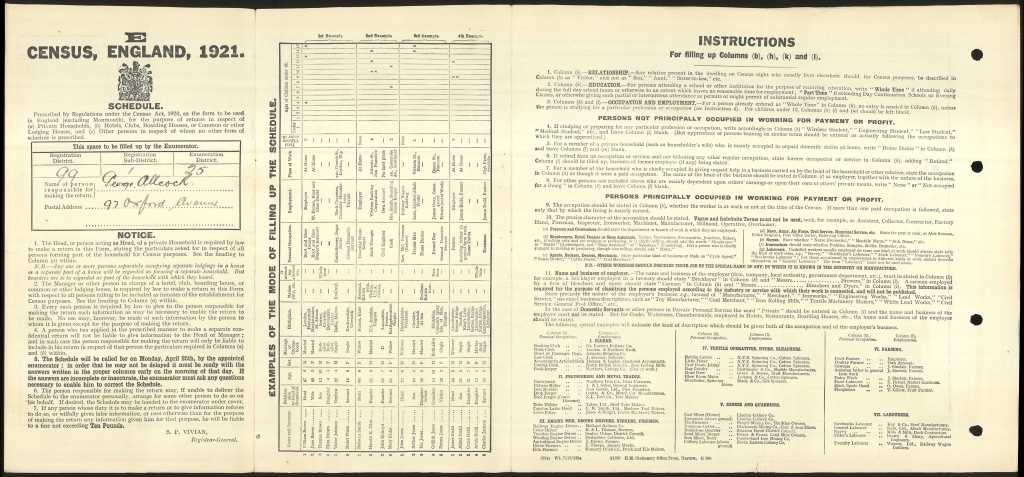

On the evening of Sunday, the 19th day of June 1921, as the nation prepared for the latest census, Robert Wallace, now 22 years old, was settled with his family at Number 97, Oxford Avenue, Southampton. Life had changed since his own childhood, and now he was a husband, a father, and a man working hard to provide for those he loved. His job as a motor coach driver for F. May Six Dials Solon in Southampton kept him busy, navigating the city streets at a time when motor transport was becoming increasingly vital.

By his side was his wife, Edith Ellen Wallace, a devoted mother who dedicated her days to "House Duties," caring for their home and their two young sons. Three-year-old John McIntyre Wallace, named for his grandfather, was full of energy, while nine-month-old Frederick Robert Wallace was still in the tender years of infancy. Their home was bustling, filled with the sounds of childhood, the responsibilities of parenthood, and the daily rhythm of a growing family.

The household at Number 97 extended beyond Robert, Edith, and their children. At the head of the household was Robert’s stepfather, George W. Allcock, a man of the sea who worked as a ship’s steward for Cunard S.S. Co. Ltd in Liverpool. He was assigned to the prestigious S.S. Berengaria, a grand ocean liner that once sailed as a German vessel before being claimed by the British after the war. At 42 years old, George’s life was still shaped by the waves, his work taking him away from home, leaving Maude Elizabeth Allcock, Robert’s mother, to tend to the house in his absence. At 48, Maude had already lived through so much, widowhood, remarriage, and the ever-changing landscape of family life. Yet she remained the steady force at the heart of the home.

Adding to the lively dynamic of the house were two boarders, Emily and John O'Brien. Emily, a 55-year-old married woman, assisted with the household duties, her presence likely easing some of the burdens on Maude and Edith. Her husband, John O'Brien, a 59-year-old Irishman, worked as a civil servant for the Crown at the Ordnance Office in Southampton. His role was part of the intricate machinery that kept the country running in the post-war years, a time of rebuilding and economic change.

With eight individuals under one roof, Number 97 was a home of many stories, many backgrounds, and many lives converging. There was the laughter of children, the hard work of fathers providing for their families, the quiet dedication of mothers managing the home, and the companionship of those who found themselves sharing in this household, bound together by circumstance. In the grand tapestry of time, it was just one night, one moment captured in the records of history, but for those who lived it, it was life unfolding in all its richness, with love, work, and duty shaping each passing day.

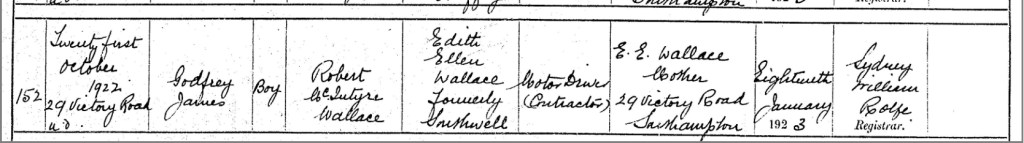

The following year brought another moment of joy to the Wallace family, as Robert and Edith welcomed their third son, Godfrey James Wallace, into the world. Born at home on Saturday, the 21st of October 1922, at Number 29, Victory Street, Southampton, his arrival marked the continuation of a growing family, a household filled with the love and chaos that only children can bring.

Robert and Edith, already devoted parents to their two young boys, John and Frederick, now had another little life to nurture. The tiny house in Victory Street would have been filled with the sounds of infant cries and the giggles of his older brothers, a bustling home where every moment was shaped by the rhythm of family life. Edith, ever the pillar of warmth and care, embraced her role as a mother once more, tending to her newborn while also ensuring that John and Frederick felt the love and attention they needed. Meanwhile, Robert worked tirelessly as a motor driver under contract, navigating the streets of Southampton to provide for his wife and sons.

It wasn’t until Thursday, the 18th of January 1923, that Edith made her way to the registrar’s office to officially record her son’s birth. Perhaps the demands of a newborn and two other little ones had delayed the task, or maybe the cold winter months made the journey more difficult. But on that January day, she stood before the registrar, Sydney William Rolfe, who carefully documented the details in the birth registry. Godfrey James Wallace, a baby boy, son of Robert McIntyre Wallace, a motor driver (contractor), and Edith Ellen Wallace, formerly Southwell, of Number 29, Victory Street, Southampton.

With the ink dried in the official record, Godfrey’s place in the world was now recognized. His name, chosen with care, would become part of the Wallace legacy, a name carried forward through time, woven into the rich tapestry of family history. His arrival was not just another entry in a registry book, it was the beginning of a life, a story waiting to unfold, shaped by the love and devotion of the family who welcomed him into their arms.

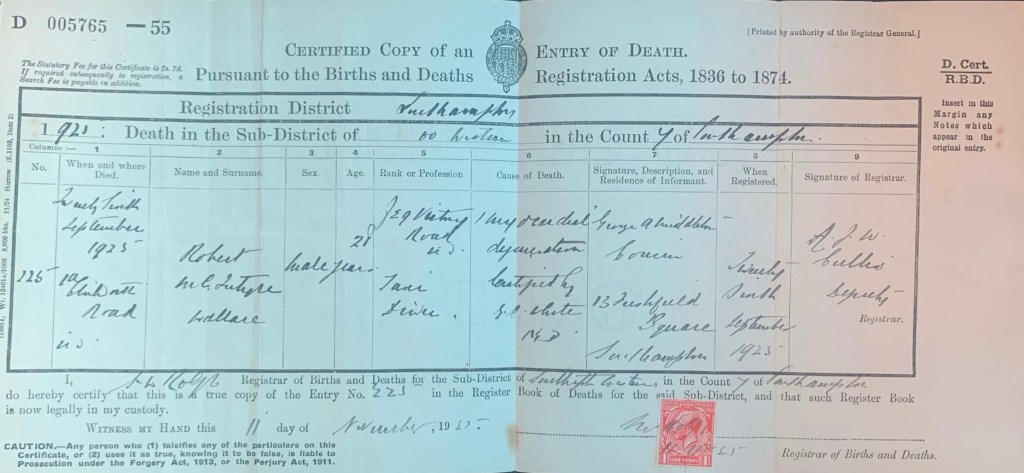

At just 28 years old, with so much of his life still ahead of him, Robert McIntyre Wallace passed away on Saturday the 26th day of September 1925. A devoted husband, a loving father, and a hardworking taxi driver, his life was cut tragically short by myocardial degeneration. The news of his passing must have been utterly devastating for those who loved him, but none more so than his beloved wife, Edith Ellen.

Pregnant with their unborn daughter, Edith was left to navigate the unbearable grief of losing her husband while preparing to bring new life into the world. The cruel contrast between death and birth must have felt impossible to bear, knowing that their little girl would never know her father’s embrace, that Robert would never see her face or hold her in his arms. It was a sorrow beyond words, a heartbreak that no young wife and mother should have to endure.

Robert took his last breaths at 1a Chilworth Road, Southampton, a place that had been the address of the Southampton Union Workhouse, now Southampton General Hospital. His cousin, George A. Middleton of Freshfield Square, bore the heavy responsibility of registering his death that very same day. Perhaps George had been by his side in his final moments or had stepped in to support Edith in her time of need. However it happened, it was a day marked by profound loss.

The registrar, A. J. W. Collins, recorded the details in the death registry, a solemn acknowledgment of a life ended too soon. But even in the formality of official records, Robert was more than just a name on a certificate. He was a man who had worked hard to provide for his family, a man who had been behind the wheel of a taxi, driving through the streets of Southampton, unaware of how little time he had left. He was a husband who had stood beside Edith on their wedding day, a father who had cradled his sons, John, Frederick, and Godfrey, never knowing he would not see them grow into men.

The details of his death certificate are unclear, and perhaps there will always be a lingering uncertainty about the precise circumstances. But what remains unquestionable is the depth of loss felt by those who loved him. His name, his story, and his legacy live on, not just in the records of history but in the blood of his descendants, in the memories passed down through generations, and in the hearts of those who refuse to let him be forgotten.

In the early 1900s, 1a Chilworth Road in Southampton, Hampshire, was the address of the Southampton Union Workhouse, an institution established under the Poor Law system to provide shelter and employment for the impoverished. The workhouse system had been a significant part of British social welfare since the 17th century, evolving over time to address the needs of the destitute.

Southampton's first workhouse originated from a bequest in 1629 by John Major, who left £200 to establish a house of twelve rooms for the poor. Over the centuries, the workhouse system expanded and adapted, with the Southampton Union Workhouse eventually being situated at 1a Chilworth Road. This location later became associated with the Southampton Infirmary, which provided medical care to the city's residents.

By the early 20th century, the workhouse at 1a Chilworth Road had evolved to include medical facilities, serving as both a refuge for the poor and a place where the sick could receive care. The address became synonymous with the infirmary, reflecting its dual role in providing both social support and healthcare services to the community.

In subsequent years, the area underwent significant changes, with the original workhouse and infirmary eventually being replaced by modern healthcare facilities. The road itself was renamed Tremona Road, and the site is now home to Southampton General Hospital, a major medical center serving the region.

The history of 1a Chilworth Road exemplifies the broader evolution of social welfare and healthcare in England, transitioning from the workhouse system of the 17th century to the comprehensive medical services provided by institutions like Southampton General Hospital today.

Family and friends gathered beneath the solemn grey skies of Southampton Old Cemetery, Hill Lane, on Wednesday, the 30th day of September 1925, to lay Robert McIntyre Wallace to rest. He was buried in Block 182, Number 18, alongside his father, John McIntyre Wallace, where, in time, his mother Maude would also be laid to rest. His burial was recorded as the 101103rd interment, at the cemetery.

Robert’s funeral was simple yet dignified, a reflection of the man he was. His polished coffin with brass fittings, lined with robe and ruffle, was a small but meaningful tribute to a life that had ended far too soon. The funeral cost £14.18, a sum that carried weight not only in financial terms but in the love and sorrow that accompanied it.

Yet, among those who gathered to say their final goodbyes, one person was heartbreakingly absent, his beloved Edith. We may never know for certain why she was unable to attend. Was it because she was heavily pregnant and physically unable to bear the strain of the day? Or was it that the grief of losing Robert, the love of her life, was simply too overwhelming to face? The pain of standing at his graveside, knowing she would never hear his voice again, must have been beyond anything words can express.

My heart shatters for Edith, for the unbearable weight she must have carried not being able to say a final goodbye to the man she had built her world around. The grief, the disbelief, the sheer devastation of losing Robert so suddenly must have been soul-crushing. Not only was she mourning the love of her life, but she was left to face the unthinkable, alone, heavily pregnant, with three young sons to care for, to feed, to clothe, to shelter, and somehow, to comfort when her own heart was in pieces.

Yet in the darkest depths of her sorrow, there was one undeniable truth that would carry her forward, Robert was not truly gone. A part of him lived on in each of their children, in John, in Frederick, in Godfrey, and in the unborn daughter Robina Maud Ellen May Wallace, who would never know his touch but would forever carry his name in her story. Through them, through their eyes, their laughter, their very existence, Robert would remain. His love would endure in every breath they took, in every memory they shared, and in every heartbeat of the family he left behind.

Just two weeks after Edith losing her beloved Robert, Edith gave birth to their daughter, Robina Maude Ellen Wallace, on Saturday, the 10th day of October 1925, at their home, Number 29, Victory Road, Southampton, Hampshire, England. A precious new life entered the world, carrying the names of both her parents, forever linking her to the father she would never have the chance to meet.

For Edith, it must have been an emotional storm, welcoming her daughter while still reeling from the unimaginable loss of her husband. Little Robina was a symbol of both sorrow and hope, a piece of Robert left behind, a reminder that love endures even in the face of such profound grief. She would grow up surrounded by the stories of her father, his memory woven into the fabric of her life, his love living on through her and her brothers.

And now, generations later, Robert’s and Robina’s legacy continues through our family, their blood running through the veins of those who carry the family name, their stories, and the love that began with Robert and Edith so many years ago.

While official records give us names, dates, and occupations, it is the memories passed down through generations that truly bring someone to life. And Robert’s story is no exception. Though no formal documentation has yet been found to confirm his time as a fireman, the treasured photograph of him in his fire service uniform stood as proof in the hearts of those who loved him. It was a cherished possession, framed and displayed with pride, a symbol of his bravery and dedication.

His daughter, Robina Maude Ellen Wallace, known to many as Bee, spoke of it often, remembering the image of her father in uniform with deep affection. But heartbreakingly, when Bee, her husband Norman John Hillier (John), and their children Robert and Janet Hillier moved from their home, Oakleigh in East Dean, Hampshire, to Carters Clay, Lockerley, near Romsey, the treasured photograph was lost.

Bee never saw it again.

The question of its whereabouts remains a mystery, a lingering hope within the family. Was it left behind in the loft of Oakleigh? Could it still be hidden somewhere, waiting to be found? Or was it unknowingly discarded, lost forever? The thought that it may still exist somewhere, tucked away in an attic, forgotten in an old frame, or in the hands of someone who does not know its significance, fuels the family’s determination to find it.

Bee never got the answers she longed for, and now, her family continues the search.

If you remember Bee and John from Carters Clay, or if you know anyone who lived at Oakleigh, East Dean, or in the surrounding areas, please spread the word. A simple conversation, a shared memory, or an old photo album could hold the key to reuniting this precious portrait with Robert’s grandchildren, great-grandchildren, and future generations yet to come.

It may be a long shot, but for a family whose history is woven together with love, perseverance, and an unbreakable bond, hope remains.

If you have any information, no matter how small, please reach out. Finding Robert’s missing photograph would mean the world to our family.

A life too short but never forgotten.

Rest in Peace,

Robert McIntyre Wallace

20th January 1898 – 26th September 1925

Gone too soon, but his love and legacy live on through his children, his grandchildren, and all who carry his story in their hearts.

As I reach the end of Robert McIntyre Wallace’s story, I find myself lingering in the spaces between the words, in the echoes of a life that was both beautiful and heartbreakingly brief. His journey, one of love, hard work, devotion, and tragedy, was not just a collection of dates and documents, but a testament to the man he was and the impact he left behind.

Robert was a son, a husband, a father, and a provider. He loved, and he was loved. He laughed, worked, and built a life full of promise. He should have had more years, years to watch his children grow, to hold his newborn daughter, to stand beside Edith as they grew old together. But fate had other plans, and at just 28 years old, his story was cut short.

Yet, Robert was never truly lost. His legacy lived on in the eyes of his children, in the strength of Edith as she carried on without him, in the generations that followed, each one carrying a piece of him forward. His name is not just etched into stone in Southampton Old Cemetery, but into the very fabric of his family’s history, where he remains, forever remembered and deeply cherished.

To Robert McIntyre Wallace, your story has been told, your name spoken with love, and your life honored. Though the years have passed, you are not forgotten. You live on in every heartbeat of the family you left behind.

Rest in peace, Robert. Your journey does not end here.

I have brought and paid for all certificates or been given copies of the originals from direct desendents,

Please do not download or use them without our permission.

All you have to do is ask.

Thank you.

🦋🦋🦋