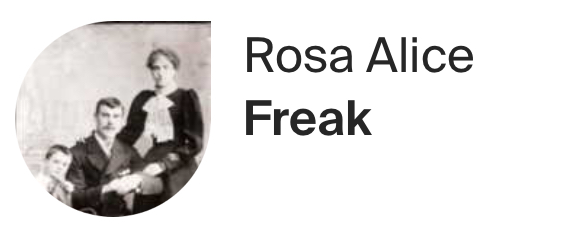

In the quiet corners of family lore, where whispered tales mingle with sepia-toned photographs, there exists a story woven through the fabric of time, the life of Rosa Alice Freak, my maternal 2nd great-grandmother. As I embark once again on this journey through her early years, I find myself drawn back not just by the passage of time, but by the evolution of my own narrative voice.

Rosa's story first unfolded under the weekly cadence of the "52 Ancestors in 52 Weeks" challenge, where each prompt gently peeled back layers of a life shaped by sorrow and resilience. Yet, amid hardships etched in faded ink, there blossomed a love that transcended eras, echoing through generations to form the foundation of my own cherished family.

In revisiting Rosa's narrative, I am reminded anew of the profound importance of family and the timeless quest to trace our heritage. While archival records offer mere fragments of her journey, they serve as sacred threads binding us to our roots, a testament to the enduring power of memory and the stories that define us.

Join me as we traverse the early chapters of Rosa Alice Freak's life, a journey marked not only by the struggles she faced but by the enduring love and legacy she bestowed upon us all.

So without further ado I give you,

The Life Of Rosa Alice Freak

1877–1965,

The Early Years (Revisited).

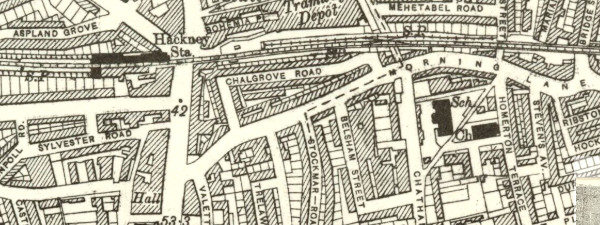

Welcome back to the year 1877, Hackney, Middlesex, England. The air is thick with the scent of coal smoke, winding through the narrow streets and settling over the rows of terraced houses, where families of the working class live shoulder to shoulder. It is a time of contrasts, of grand Victorian opulence and deep, grinding poverty, of industrial progress and harsh living conditions.

Queen Victoria sits on the throne, a formidable figure who has reigned for forty years, embodying the very essence of the British Empire at its height. The Prime Minister is Benjamin Disraeli, a statesman known for his charm and wit, whose government promotes imperial expansion and social reform. Parliament is alive with debates over Britain’s global influence, the rights of workers, and the ever-present struggles between the ruling classes and the growing voice of the people.

Life in Hackney reflects these broader national tensions. The wealthy live in comfortable homes, adorned with heavy drapes, ornate furniture, and gas lamps casting a warm glow over evening gatherings. Their concerns lie in social status, maintaining proper etiquette, and attending lavish balls, where ladies in tightly corseted gowns sweep across the floors in layers of silk and lace. Gentlemen, clad in tailcoats and top hats, discuss politics, business, and empire over cigars and brandy.

For the working class, life is a far harsher reality. Men labor long hours in factories, on docks, or in workshops, earning barely enough to sustain their families. Women, if not employed as domestic servants, take in laundry, sew garments, or scrub floors in grand houses where they are invisible to those they serve. Their dresses are simpler, made of wool or cotton, often repaired and mended to last another season. Children play barefoot in the streets, some fortunate enough to attend school, while others are sent to work in factories or as errand boys, helping to support their families from the moment they can walk and talk.

For the poor, the conditions are even more dire. Overcrowded slums, filled with the stench of sewage and uncollected waste, breed disease. Typhoid, tuberculosis, and cholera are never far away, as sanitation is primitive at best. Water is often contaminated, and while public health reform is a topic of discussion among politicians, change is slow to reach those who need it most.

The streets are alive with the rattle of horse-drawn omnibuses and hansom cabs, their wheels clattering over cobblestone roads. The railway stations bustle with activity as steam trains, the arteries of Victorian Britain, carry people and goods across the country. For those who can afford it, the Great Eastern Railway connects Hackney to the city and beyond, making travel more accessible than ever before.

At home, warmth comes from coal fires, their smoke curling up from chimneys, filling the sky with a permanent haze. Gas lamps flicker in the wealthier households, while the poor rely on candles or oil lamps to chase away the darkness. The smell of coal dust lingers on clothes, on walls, in the very fabric of daily life.

Food, too, is a reflection of class. The rich dine on roasted meats, fresh fruits, and fine wines, their tables heavy with delicacies from across the empire, spices from India, sugar from the Caribbean. The working class make do with bread, cheese, and boiled potatoes, stretching what little they have to feed hungry mouths. For the poor, meals are sparse, often consisting of nothing more than a weak broth or gruel, with a piece of stale bread if they are lucky.

Entertainment offers a rare escape from the drudgery of daily life. Music halls are filled with laughter and song, offering comic acts, melodramas, and sing-alongs. Theatres stage grand productions of Shakespeare and the latest sensational dramas, attended by the fashionable elite. The circus and traveling fairs bring excitement to the streets, with acrobats, fire-eaters, and exotic animals drawing crowds of wide-eyed children and weary laborers looking for a moment of joy.

The gossip of the time is a mix of scandal and intrigue. Queen Victoria still mourns her beloved Prince Albert, though whispers abound about her close relationship with her servant, John Brown. The newspapers are filled with stories of the empire’s conquests, political rivalries, and the latest crimes that shock and horrify London’s citizens. In the alleyways and pubs, workers grumble about their harsh conditions, while in the drawing rooms of the wealthy, talk turns to marriage prospects, fortunes made and lost, and the ever-growing influence of the industrial age.

The divide between the classes is stark, a world of privilege and suffering existing side by side. The wealthy live in comfort, their lives untouched by the grime of the city, while the poor struggle to survive, their hardships unseen by those who pass them on the street. Yet, even in the darkest corners of Hackney, there is resilience. Families hold together, communities look after one another, and amidst the struggle, there are moments of love, joy, and hope for a better future.

This is the world into which Rosa Alice Freak was born, a world of hardship and perseverance, of sorrow and love. A world that shaped the woman she would become, and the legacy she would leave behind.

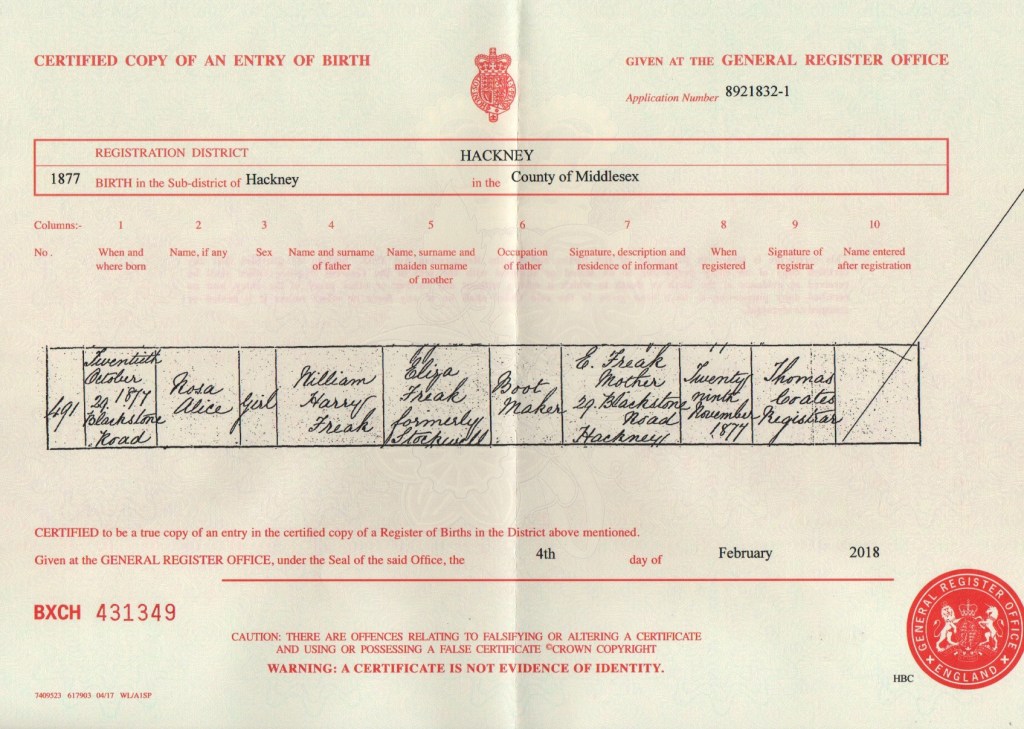

Rosa Alice Freak’s life began on a crisp autumn Saturday, the 20th of October, 1877. She was born into the warmth of her family’s home at Number 29, Blackstone Road, Hackney, Middlesex, England, where the laughter and footsteps of her older siblings filled the air. She was the sixth child of William Harry Freak and Eliza Freak (née Stockwell), a couple who had already known both the joy of new life and the heartbreak of loss. Her siblings, Elizabeth Annie, Ellen Eliza, Charles William, and George Edward, would have welcomed her with curiosity and affection, though the absence of little Philip and Phoebe, who had both passed in infancy, lingered as a silent ache in the family’s history.

Amidst the daily rhythms of their working-class home, Rosa’s arrival would have been a moment of both celebration and deep gratitude. Her mother, Eliza, made the important journey to register her birth on Thursday, the 29th of November, 1877, ensuring that Rosa’s place in the world was officially recorded. The registrar, Thomas Coates, carefully penned the details into the ledger, her father, William, a boot maker, her mother, Eliza Freak formerly Stockwell, of Number 29, Blackstone Road, Hackney. With that act, Rosa’s story was set in ink, forever anchoring her to the family, the street, and the time in which she was born.

The name Rosa has deep roots across various cultures. It derives from Latin, meaning "rose," symbolizing beauty and love. In Christian tradition, it honors Saint Rosa of Lima, known for her piety and care for the sick. Rosa gained popularity across Europe in the Middle Ages and later spread globally. It embodies elegance and grace, resonating in literature, art, and music.

On the other hand, Alice originates from Germanic elements meaning "noble" and "light." It gained prominence in England during the Middle Ages, notably through the works of Geoffrey Chaucer and Lewis Carroll's "Alice's Adventures in Wonderland." Alice reflects innocence, curiosity, and intelligence. Its enduring appeal persists through various cultures, embodying resilience and sophistication in modern times.

The surname Freak is an unusual and rare name, with origins that are not widely documented but are believed to be of Anglo-Saxon or Old English descent. Variants of the name, such as Freke or Freake, appear in historical records, particularly in the western and southern parts of England. It is thought to derive from the Old English word frec, meaning bold, daring, or greedy, possibly referring to someone known for their bravery or assertiveness. Some sources suggest that it may also have connections to a nickname, describing a person of distinctive character. The name appears in records as early as the medieval period, though it remained relatively uncommon.

Coats of arms associated with the Freke or Freak surname suggest that those bearing the name may have held land or titles in centuries past. The Freke family of Dorset, for example, was a notable lineage with a recorded coat of arms featuring a shield of azure (blue) with two bars or (gold), and in chief three mullets of six points or (gold stars). The design represents nobility, strength, and honor, and such coats of arms were often granted to families of distinction. While there may not be a widely recognized coat of arms for every branch of the Freak family, variations of the name have been linked to heraldic traditions over time.

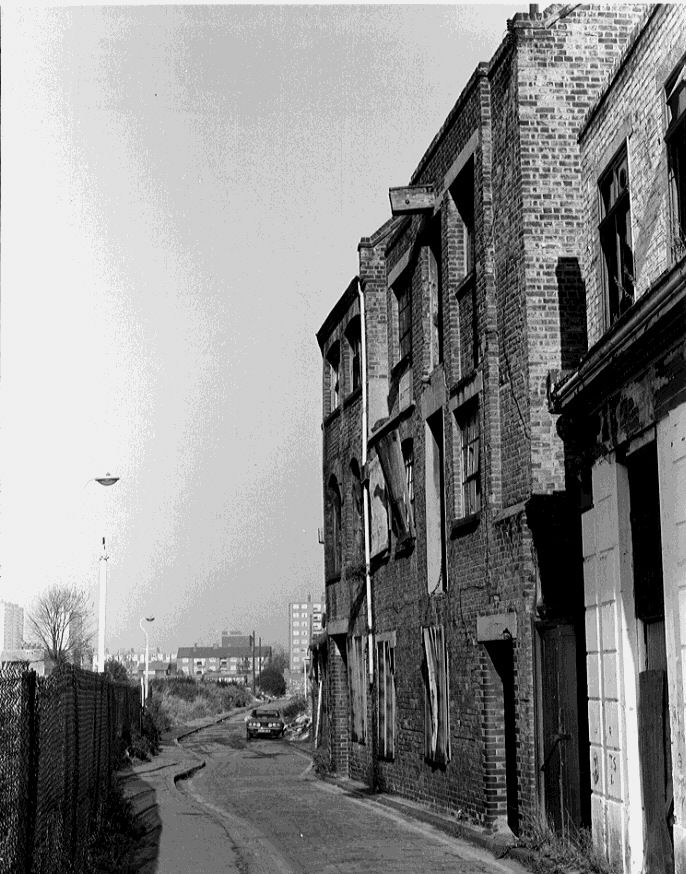

Blackstone Road was a street in the southern part of Hackney, London, near London Fields. In the 1960s, significant redevelopment led to the demolition of Victorian-era streets, including Blackstone Road, to make way for the Blackstone Estate. This estate features modern housing blocks such as Aldington Court, an eight-storey building containing 30 dwellings.

Rosa’s beloved sister, Mary Jane Freak, lifes journey began on a bright Tuesday, the 27th day of April in 1880. She entered this world at Number 2, Hiram Place in Bevois Hill, South Stoneham, Southampton, Hampshire, England, a place that would witness the early joys and challenges of life.

Their devoted mother, Eliza Freak, embraced the responsibility of registering Mary Jane's birth on the 7th of June, 1880. The registrar, Edward Messum, meticulously noted the details that would forever link Mary Jane to her family, a precious girl born on that lovely April day, the cherished daughter of William Harry Freak, a skilled bootmaker, and Eliza Freak, who proudly carried the name Stockwell.

Hiram Place, located on Bevois Hill in the South Stoneham area of Southampton, Hampshire, England, is a site with historical significance that reflects the rich tapestry of the region's past. The area of Bevois Hill derives its name from the legendary figure Sir Bevois, who, according to local lore, founded the town of Southampton. This legend has imbued the locale with a sense of historical depth and cultural identity.

In the 18th century, the Bevois Mount estate was established by Charles Mordaunt, the 3rd Earl of Peterborough, around 1723. He combined existing lands, including Padwell Farm, to create this estate. The estate featured a prominent artificial mound, known as Bevois Mount, which was integrated into the landscaped gardens of Bevois Mount House. This mound was a notable feature, offering picturesque views of the surrounding area. The estate became a cultural hub, frequented by notable figures such as the poet Alexander Pope, who contributed to the design of its gardens. Over time, the estate underwent various changes in ownership and purpose, reflecting the evolving landscape of Southampton.

The development of Hiram Place is intertwined with the broader urbanization of the Bevois Valley area. As Southampton expanded, particularly during the 19th and early 20th centuries, the once rural landscapes of estates like Bevois Mount were transformed into residential and commercial zones. This period saw the subdivision of large estates and the creation of new streets and housing developments to accommodate the growing population. While specific records detailing the establishment of Hiram Place are limited, it is plausible that it emerged during this era of urban expansion, serving as housing for workers and their families drawn to Southampton's burgeoning industries and port activities.

The Bevois Valley area, encompassing Bevois Hill and its environs, has long been recognized for its diverse community and vibrant cultural scene. The transformation from grand estates to urban neighborhoods brought together people from various backgrounds, contributing to the rich social fabric of the area. Today, Hiram Place stands as a testament to this dynamic history, reflecting the layers of development and community that have shaped the region over centuries.

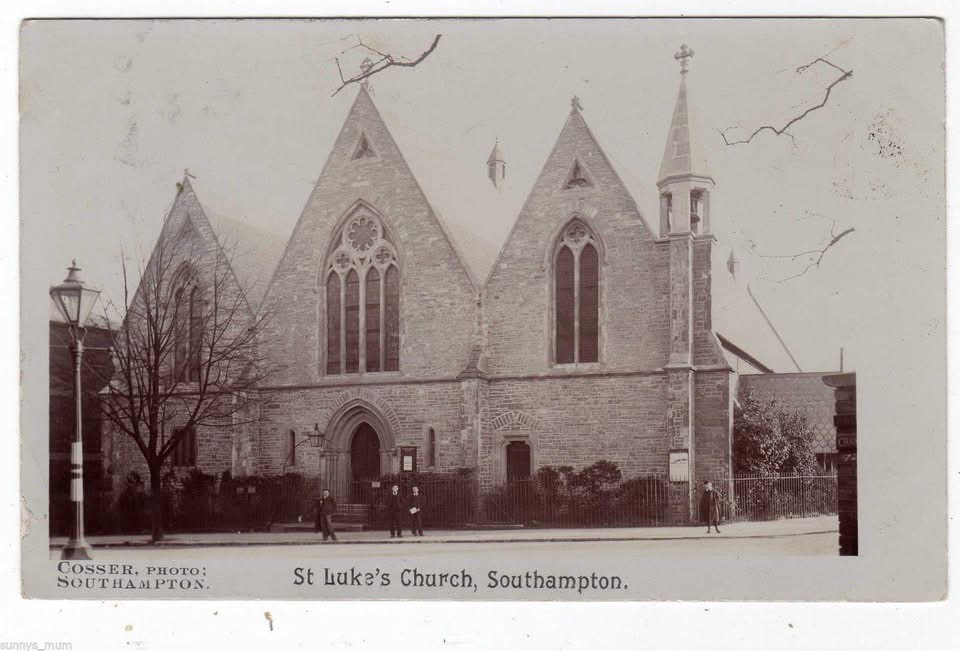

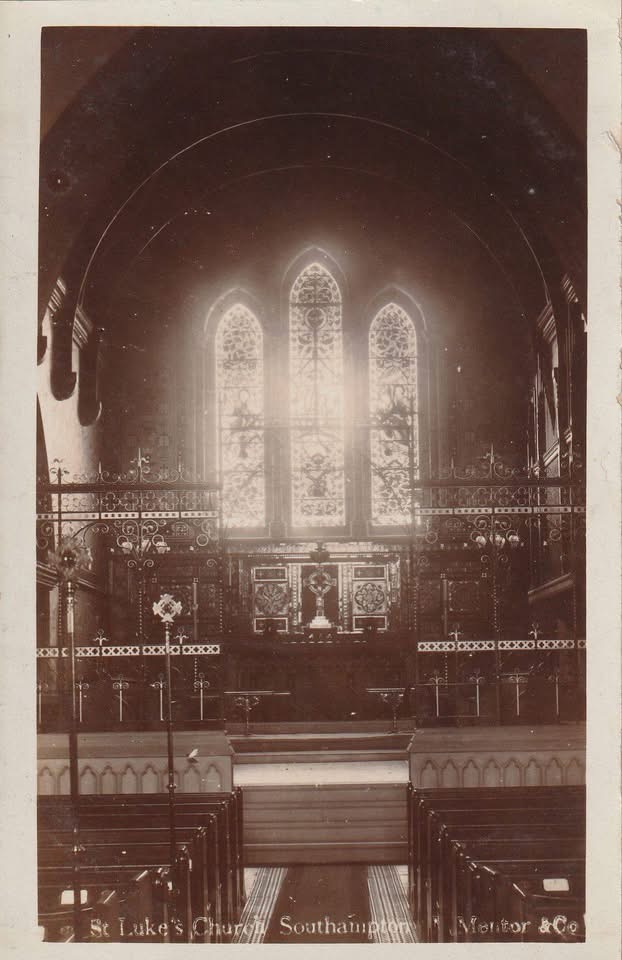

Rosa’s parents, William and Eliza, carried their youngest daughter, Mary Jane Blanche Freak, into the sacred walls of St Luke’s Church in Bevois Valley, Southampton, Hampshire, on Tuesday, the 17th of August, 1880. It must have been a day of solemnity and hope, as they stood before the font, surrounded by family and faith, dedicating their little girl to the path ahead. The echoes of hymns, the murmured prayers of the congregation, and the soft flicker of candlelight would have marked the occasion as a cherished moment in their family’s story.

For William and Eliza, this baptism was more than just a religious rite, it was an act of love and tradition, a way to give their daughter a sense of belonging, not just to their family but to something greater. The waters of baptism, the whispered blessings, and the firm grip of the priest’s hand as he inscribed her name in the parish register ensured that Mary Jane Blanche Freak’s place in the world was forever recorded, a tiny but significant entry in the annals of time.

St. Luke's Church, located in the Bevois Valley area of Southampton, was constructed between 1852 and 1853 in a neo-Gothic architectural style. The design was the work of architect John Elliott of Chichester. The church is situated at the junction of Onslow Road and Cranbury Avenue in the Newton district.

The initial structure included a nave and aisles, with the chancel added later in 1875 by J.P. St. Aubyn. The building is constructed from Purbeck stone, with window dressings and other details in Bath stone. During World War II, the church suffered bomb damage, leading to restoration work in 1958.

In 1983, the church was sold and converted into the Singh Sabha Gurdwara, serving as a place of worship for the Sikh community. The building is recognized as a Grade II listed structure, highlighting its architectural and historical significance.

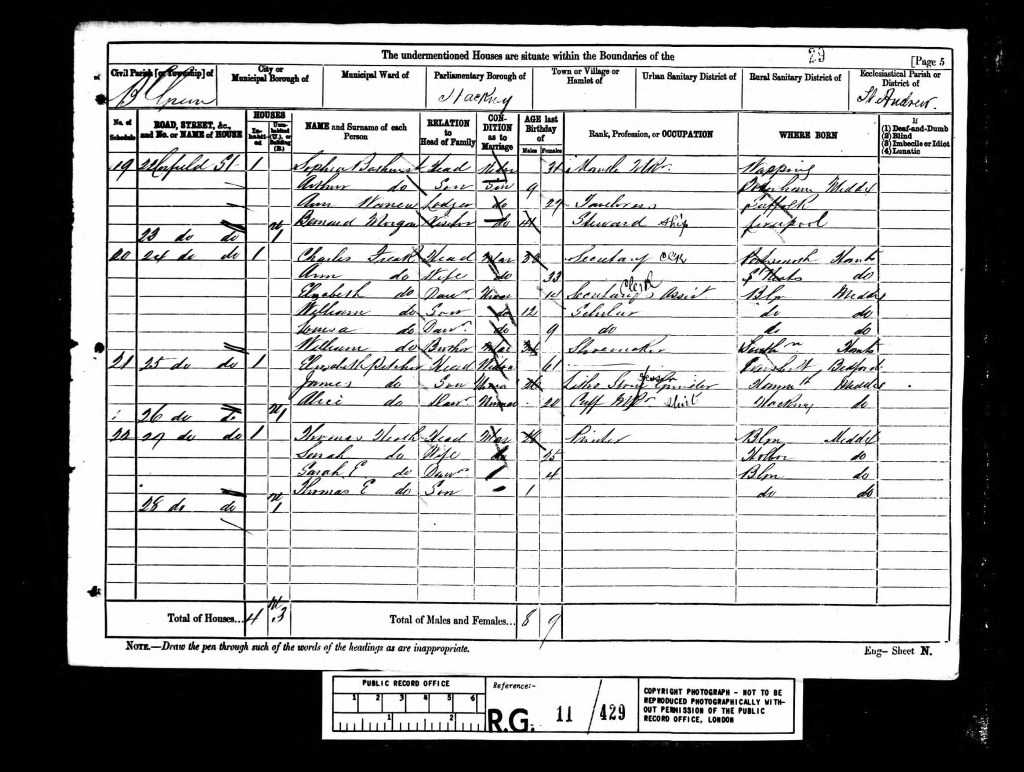

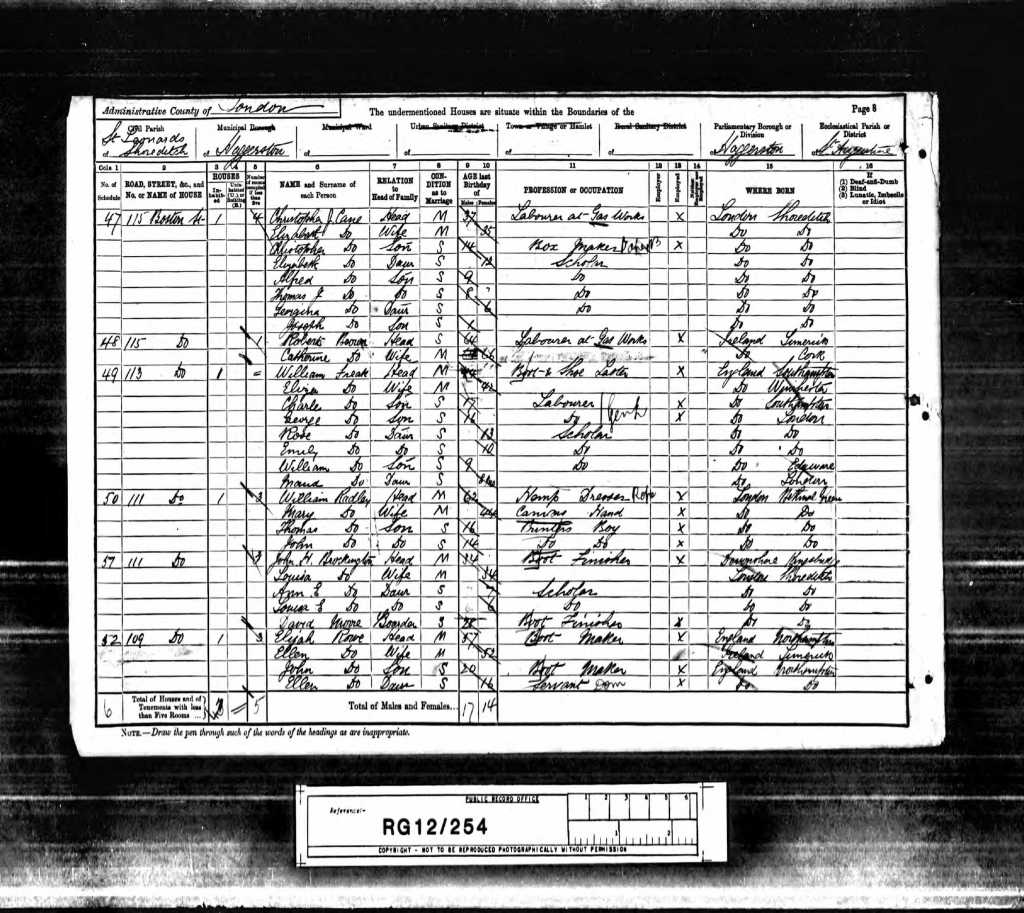

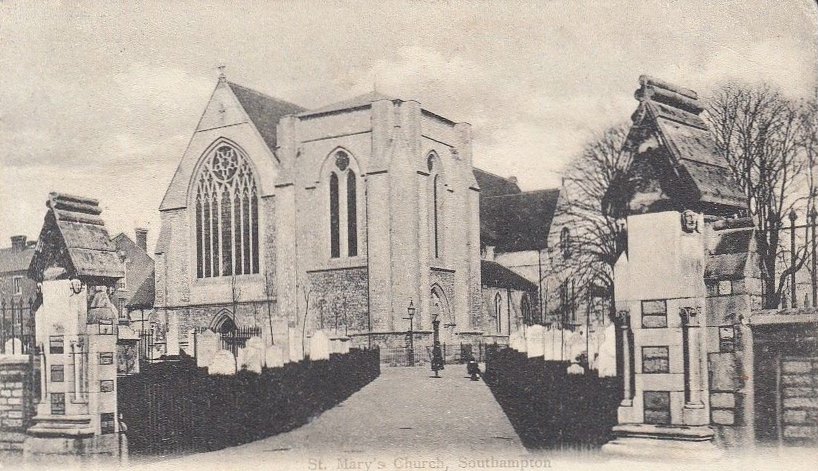

On the eve of the 1881 census, Sunday, the 3rd day of April, 3 year old, Rosa, recorded as "Rose" on the census return, was far from her usual surroundings, spending the night with her mother, Eliza, 33, and siblings Elizabeth 13, Charles, 7, George, 6, and baby Mary at the home of James Leadbetter, his wife Emma, and their son Walter. Their residence at Number 2, Edward Street, St Mary’s, Southampton, Hampshire, may have been a place of temporary refuge, a family visit, or simply a stop along the unpredictable path of life. The census lists Eliza as married, with her occupation noted as a "Boot Maker’s Wife," a subtle yet telling indication of the challenges faced by women whose husbands' work often dictated the family’s movements and stability. Elizabeth, Charles and George were all scholars, likely attending a local school, while James Leadbetter, the head of the household, worked as a General Dock Labourer, a profession deeply tied to the lifeblood of a port city like Southampton.

Meanwhile, over 80 miles away in Bethnal Green, Rosa’s father, William, was recorded at Number 24, Corfield Street, residing with his older brother, Charles Augustus Freak. At 33, Charles was employed as a secretary clerk, while his wife Ann, also 33, managed their bustling household, which included their children Elizabeth, 14, working as a secretary clerk assistant, William, 12, and Louisa, 9, both of whom were still scholars. William, away from his wife and younger children, gave his occupation as a shoemaker, a skilled trade that had long sustained the Freak family.

What led to this temporary separation? Was it work that had kept William in London , or had life’s circumstances forced them to live apart for a time? The census offers only a snapshot, a moment frozen in ink, leaving more questions than answers. Yet, it paints a vivid picture of a family navigating the realities of late 19th-century England, where work, opportunity, and the need for support from extended family often dictated where a person laid their head at night.

Edward Street, situated in the St Mary's district of Southampton, Hampshire, England, has a history intertwined with the city's development and the evolution of the St Mary's area. The St Mary's district traces its origins back to the Saxon period, with the founding of St Mary's Church in the 8th century serving as a focal point for the community. Over the centuries, the area surrounding the church expanded, leading to the establishment of various streets, including Edward Street. The district's growth was influenced by its proximity to the River Itchen, which facilitated trade and transportation, contributing to the urbanisation of the area. In the 19th century, the expansion of Southampton as a port city led to increased residential and commercial development in St Mary's. Edward Street emerged during this period, characterized by Victorian-era architecture and a mix of residential housing and local businesses. The street, like many others in the vicinity, was home to working-class families, many of whom were employed in the docks and related industries. The community was diverse, with a range of religious and cultural backgrounds represented among its residents. The area saw significant changes during the mid-20th century, particularly due to the impact of World War II. Southampton suffered extensive bombing during the Blitz, leading to the destruction of many buildings in the St Mary's district. Post-war reconstruction efforts in the 1950s and 1960s brought about modern housing developments and alterations to the original street layouts. While specific records about Edward Street's individual history are limited, its development reflects the broader trends experienced by the St Mary's area and Southampton as a whole.

Corfield Street is a notable thoroughfare located in Bethnal Green, East London, with a rich history that reflects the area's urban development and social transformations.

In the mid-19th century, the Improved Industrial Dwellings Company embarked on a significant project to address the pressing need for quality housing among the working class. Between 1868 and 1880, they constructed tenement blocks along Corfield Street, replacing the existing 18th-century slums. These new dwellings were part of a broader initiative to provide improved living conditions in rapidly urbanizing areas.

The architectural landscape of Corfield Street was further transformed with the development of the Waterlow Estate. This estate encompassed several streets, including Corfield, Ainsley, and Finnis, and was developed in the late 19th century to offer better housing options to the working population. The estate's design aimed to alleviate overcrowding and improve living standards, featuring blocks that provided homes for numerous families.

Throughout the 20th century, Corfield Street and its surroundings continued to evolve. The area underwent various phases of redevelopment and gentrification, reflecting broader socio-economic changes in East London. Today, Corfield Street stands as a testament to the area's complex history, showcasing a blend of historical and modern influences that narrate the story of Bethnal Green's development over the years.

Some stories in family history unfold easily, their details neatly recorded in official documents, while others remain stubbornly elusive, leaving behind only traces and unanswered questions. Rosa’s sister, Emily Freak is one such mystery, the daughter of William and Eliza, born around 1881 in London, yet missing from the birth indexes that should confirm her place in the family’s timeline.

Despite the absence of a birth record, Emily's existence is undeniable. The 1891 census lists her as a ten-year-old girl, born in London, and part of the Freak household. And then, of course, there are the photographs, powerful visual proof of her life. One captures her standing beside her sister Rosa Alice Freak, my maternal 2nd great-grandmother, at the wedding of their eldest sister, Elizabeth Annie Freak, to Joseph Manning on Sunday, the 9th day of June, 1889. The other, taken when Emily was just five years old, offers an even more intimate glimpse into her childhood.

Yet in 1881, when the census was taken, Emily is nowhere to be found. She was not with her father, William, at the Bethnal Green home of his brother, Charles Augustus Freak. Nor was she among the family members visiting James Leadbetter and his wife Emma in Southampton. Where was she on that April night? Was she staying with another relative, overlooked by the enumerator, or even mistakenly recorded under a different name? Could she have been unwell, sent away for care, or simply miscounted?

Though the paper trail refuses to give up its secrets, Emily's presence within the family is clear. She lived, she was loved, and through both the census and the photographs that have been carefully preserved, her memory endures.

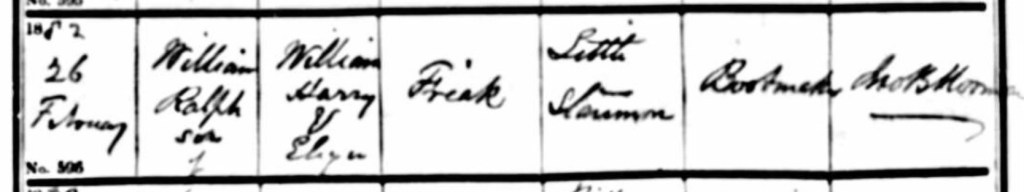

On a warm summer Sunday, the 24th day of July, 1889, Rosa’s younger brother, William Ralph Freak, entered the world in Little Stanmore, Hendon, Middlesex, England. His birth would have been a moment of both joy and relief for his mother, Eliza, who had already known the heartbreak of losing children in infancy. With her husband William working tirelessly as a bootmaker, it was Eliza who took on the important duty of registering their son’s birth.

On the 29th day of August, 1889, she made her way to the registrar’s office, where William Lukym, the official in attendance, carefully recorded the details into the birth register. Line by line, the family’s history was etched into record, William Ralph Freak, a son, born to William Harry Freak, a bootmaker, and Eliza Freak, formerly Stockwell, of Little Stanmore. It was a small but significant act, ensuring that William’s arrival was recognized not just within the family, but within the world beyond their doorstep.

Little Stanmore, also historically known as Whitchurch, is an ancient parish situated in the historic county of Middlesex, England. Today, it forms part of the residential area known as Canons Park within the London Borough of Harrow. The name 'Stanmore' is believed to derive from the phrase "stone mere," meaning a pond made of stone, while 'Whitchurch' translates to 'white church,' likely referencing a stone-built church in the area.

The parish of Little Stanmore was established to distinguish it from the neighboring Great Stanmore (now simply Stanmore). Historically, Little Stanmore encompassed the western part of the town of Edgware. In 1836, it joined the Hendon Poor Law Union for the administration of poor relief and later became part of the Hendon Rural Sanitary District in 1875. With the formation of Hendon Rural District in 1894, Little Stanmore was included within its jurisdiction. The civil parish was eventually abolished in 1934, and its area was absorbed into the Harrow Urban District, which later evolved into the London Borough of Harrow in 1965.

A notable landmark in Little Stanmore is St. Lawrence's Church, which underwent significant reconstruction in the early 18th century under the patronage of James Brydges, the 1st Duke of Chandos. The church was redesigned in the Baroque style by architect John James, with possible contributions by James Gibbs. The interior boasts early 18th-century paintings by artists such as Louis Laguerre and houses an organ that was once played by the renowned composer George Frideric Handel. In the churchyard, there is a tombstone for William Powell, reputed to be "The Harmonious Blacksmith" who inspired one of Handel's famous keyboard compositions.

Throughout the 20th century, Little Stanmore transitioned from a rural parish to a suburban area, especially with the development of the Canons Park estate. This transformation was marked by residential expansion and the integration of the area into the greater London metropolis. Today, Little Stanmore, or Whitchurch, retains its historical charm while serving as a vibrant residential community within the London Borough of Harrow.

On Sunday, the 26th day of February, 1882, Rosa’s parents, William and Eliza, carried their infant son, William Ralph Freak, into the sacred space of Saint Lawrence Church in Little Stanmore, Middlesex, England. It was a significant day for the family, one filled with reverence and quiet joy as they gathered to baptize their baby boy, marking his place within both their faith and their community.

Though time has blurred the name of the minister who performed the baptism, the entry in the parish register remains, preserving the details that tied this moment to the Freak family's history. William, like his father before him, was recorded as a bootmaker, a trade that had provided for the family for generations. Their home, too, was noted: Little Stanmore, a quiet corner of Middlesex where they had built their life together, where love and hardship intertwined in equal measure.

For William and Eliza, this was more than a simple church ceremony. It was a reaffirmation of family, of faith, and of the deep responsibility they felt for their children’s future. In a world that was rapidly changing, where industrial progress reshaped daily life and uncertainty was always near, these small but profound rituals anchored them. They would not have known, as they stood by the baptismal font that day, just how their story would unfold, or how the records they left behind would one day be traced by their descendants, seeking to understand the lives they once lived. But in that moment, surrounded by the familiar hush of the church, they did know this: they had brought another child into the world, and they would do everything in their power to love and protect him.

St. Lawrence's Church, also known as Whitchurch, is a historic parish church located in Little Stanmore, Middlesex, England. The church is renowned for its rich history and architectural significance, particularly its transformation in the early 18th century.

The original medieval structure of St. Lawrence's dates back to around 1360, with the stone tower from that period still standing today. In 1715, James Brydges, who later became the 1st Duke of Chandos, acquired the Cannons estate in Little Stanmore and undertook a significant reconstruction of the church. This project was part of his broader vision to enhance his estate, and he commissioned architect John James to design the new church building in the Continental Baroque style. The reconstruction was completed in 1716, resulting in a church interior that is both ornate and unique within England.

The interior decoration of St. Lawrence's is particularly noteworthy. The walls and ceilings are adorned with paintings by Louis Laguerre, a prominent decorative painter of the time. These artworks contribute to the church's Continental Baroque aesthetic, setting it apart from typical English church designs. Additionally, the church features exquisite woodwork, including oak Corinthian columns and other carvings by the master carver Grinling Gibbons.

A significant addition to the church is the Chandos Mausoleum, constructed in 1735 at the behest of the 1st Duke of Chandos. Designed by architect James Gibbs, the mausoleum is attached to the east end of the church and serves as the final resting place for the Duke and his first two wives. The centerpiece of the mausoleum is a Baroque monument crafted by Grinling Gibbons, surrounded by elaborate wall paintings by artist Gaetano Brunetti.

St. Lawrence's Church also holds a special connection to the composer George Frideric Handel. During his tenure as composer-in-residence for the Duke of Chandos around 1717-1718, Handel composed several works, including the Chandos Anthems, which were likely first performed in this church. The church houses an organ dating back to 1716, believed to have been played by Handel himself. This instrument has undergone restoration to preserve its historical integrity and continues to be used for recitals and services.

On Monday, the 13th day of August, 1883, Rosa’s mother, Eliza, brought another precious life into the world. In the modest surroundings of Number 28D, Peabody’s Buildings, Golden Lane, Holborn, Middlesex, she gave birth to her son, Philip Henry Freak. It was a name chosen with care, perhaps in remembrance of his older brother Philip, who had passed away in infancy, a quiet tribute to a child lost but never forgotten.

Two months later, on Wednesday the 10th day of October, 1883, Eliza made the journey to Holborn to officially register Philip’s birth. She would have walked those city streets, carrying the weight of both love and responsibility, knowing the importance of ensuring her son’s place in the records of time. At the registrar’s office, the deputy registrar, John B. Hibbert, carefully recorded the details in the birth register: Philip Henry Freak, a boy, born on the 13th of August 1883, at 28D Peabody’s Buildings, Golden Lane. His father, William Harry Freak, was listed as a boot maker, the same trade that had sustained the family for generations, while his mother, Eliza, was named with pride, her role in the family’s story forever etched alongside her son’s.

Peabody’s Buildings, with their promise of better living conditions for working-class families, stood as a testament to the changing times. Life here would not have been easy, but it offered shelter, community, and hope. In the midst of London’s ever-growing sprawl, another chapter of the Freak family’s history was being written, one of love, resilience, and the unwavering commitment of parents who wanted the best for their children.

Peabody's Buildings, located on Golden Lane in Holborn, Middlesex, were part of a broader housing project initiated by the American philanthropist George Peabody in the 19th century. Peabody, who had made his fortune in finance, was deeply concerned with the living conditions of the poor in London. In 1862, he established the Peabody Trust, an organization dedicated to providing decent and affordable housing for working-class families. The aim was to alleviate the dire conditions that many people in London were experiencing, particularly in the slums that were overcrowded, unsanitary, and unsafe.

Golden Lane was one of the areas that benefited from Peabody’s efforts. The buildings on Golden Lane were designed to provide quality housing for the working poor. They were constructed with careful attention to light, ventilation, and sanitary conditions, which were a far cry from the overcrowded, poorly ventilated rooms many people had been living in. These new homes were intended to provide a better standard of living and were seen as an important development in the realm of social housing.

By the 1880s, when your ancestors were likely living in Peabody’s Buildings, the project had become an established part of London's efforts to improve housing for the poor. The buildings on Golden Lane would have been among those intended to house working-class families in reasonable conditions. These estates were scattered throughout London, and the Peabody Trust continued to expand its reach over the years, helping to address the housing crisis in one of the most densely populated cities in the world.

The buildings themselves were typically constructed in a solid, utilitarian style, designed to withstand the wear and tear of everyday life while providing a sense of stability and dignity for the tenants. Peabody's work in Holborn was part of a larger movement in London during the Victorian era, when there was a growing awareness of the need to improve living conditions for the poorest members of society. The Peabody Trust not only built homes but also played an important role in changing attitudes toward social housing.

The legacy of Peabody's efforts can still be seen in London today. The Peabody Trust is one of the largest housing associations in the UK, still providing homes for thousands of people across the city. The buildings on Golden Lane were just one part of a much larger vision that sought to create sustainable, affordable housing in a rapidly industrializing city. Through these buildings, Peabody’s influence is still felt in the urban landscape of London.

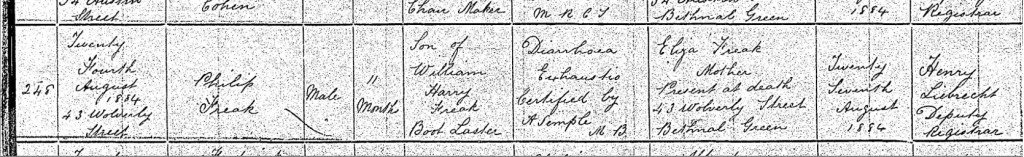

Little Philip Henry Freak’s time in this world was heartbreakingly brief. On Sunday, the 24th day of August, 1884, just 11 months old, he took his last breaths at 43 Wolverley Street, Bethnal Green, Middlesex. His mother, Eliza, was by his side, bearing witness to the unbearable, the loss of another child, a sorrow she had known before but could never truly prepare for.

Three days later, on Wednesday the 27th day of August, 1884, she gathered the strength to make the solemn journey to the registrar’s office, cradling not her baby, but the heavy burden of his absence. There, Henry Liebrecht, the registrar, carefully recorded Philip’s death in the Bethnal Green death register. His small life was summed up in stark official words: Philip Freak, son of William Harry Freak, a Boot Laster, dead at 11 months old from Diarrhoea and Exhaustion, as certified by A. Semple, medical director.

Diarrhoea, a common yet often fatal illness among infants in overcrowded and impoverished areas, was a cruel thief, stealing away so many young lives before medical knowledge or sanitary conditions could offer much protection. It’s hard to imagine the anguish Eliza must have felt, knowing there was little she could do but hold her baby close and hope for a recovery that never came.

Philip was gone, another bright spark lost too soon, another name added to the ever-growing list of children claimed by hardship. But he was loved. And though the records only tell us the facts of his passing, his place in the hearts of his family, the grief that followed, the love that lingered, cannot be measured in ink.

Wolverley Street is a notable thoroughfare located in the Bethnal Green area of East London. In the early 19th century, the surrounding region underwent significant urban development. Streets such as Anne Street, Agnes Street, and Frances Street were constructed with stock brick, terraced houses, reflecting the architectural style of the period.

By 1920, Wolverley Street became home to the Bethnal Green Men's Institute, established by the London County Council. The institute offered a variety of classes, including art, photography, carpentry, and metalwork, catering to the educational needs of the local working-class community. It also hosted cultural activities such as a choir, orchestra, and dramatic society. By 1925, the institute had over 900 members, and by 1939, membership had grown to 3,500.

The influence of the Bethnal Green Men's Institute extended beyond education and culture. It served as the foundation for the East London Group, a collective of artists active during the 1920s and 1930s. Originating from an art club at the institute, the group gained recognition for their realist paintings depicting the everyday life and landscapes of East London.

These developments highlight the pivotal role of Wolverley Street and the Bethnal Green Men's Institute in fostering community engagement, education, and cultural expression in early 20th-century East London.

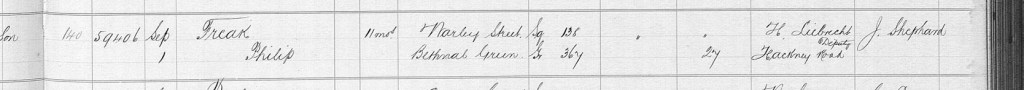

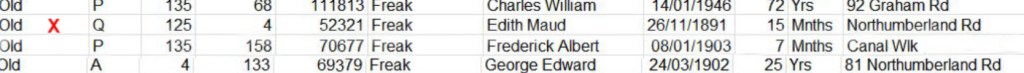

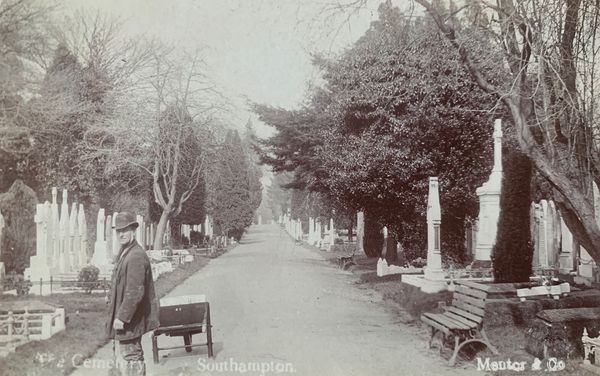

On Monday, the 1st day of September, 1884, Rosa’s baby brother, Philip Henry Freak, was laid to rest in an open grave at Manor Park Cemetery in Newham, London. He had been gone for just over a week, and in that short time, his mother, Eliza, had to summon the strength to register his passing and now, to say her final goodbye.

There was no private plot, no carved headstone bearing his name, just a shared resting place, one of many in a city where grief was a constant companion to families like the Freaks. Philip was buried alongside strangers, children and adults alike, each with their own story, their own loved ones left behind to mourn. Robt Pearce and Emma Hook were laid to rest with him that very same day. Beatrice E. Wilson and Arthur Chas Bonney joined them on the 5th of September. MacKenzie (a child), and Stanley Smith on the 4th. Edward Thos Bradbury and Elizabeth Newman had already been placed there on the 31st of August, and before them, Elizabeth Beattie on the 30th, William Crudge Salter, and Caroline Hosty on the 29th.

Manor Park Cemetery, like so many others in Victorian London, bore silent witness to the relentless cycle of life and loss. For families of the working class, individual graves were often an unattainable luxury, and open graves became the final resting place for so many souls whose time had been far too short. Yet, though Philip was buried among strangers, he was not alone. He was carried there with love, with whispered prayers, and with the unspoken ache of a mother’s grief.

Eliza and William had known this pain before, and now, they knew it again. But Philip had lived. He had been held, cherished, and adored. And though no stone may bear his name, his place in the family’s story, his place in their hearts, would never be forgotten.

In 1884, an infant funeral and burial would have been a somber, yet simple affair, shaped by the harsh realities of life in Victorian England. For a family like Rosa's, who had already endured so much heartache, the loss of their 11-month-old son Philip was no different in its pain, yet it was marked by practicalities shaped by the times.

The funeral itself would have been modest, as infant burials often were. There would have been little ceremony or fanfare. Instead, it would have been a quiet, intimate event, perhaps attended only by close family, with little distinction between the burial of a child and that of an adult, other than the smaller, more fragile casket that would carry Philip's tiny form.

In such moments, the family would have been guided by the local clergy or perhaps a lay person, if the family could not afford a full service. The ritual would have been quick, with no elaborate rituals, no flowers or mourners standing in a procession. In the working-class districts of London, where the Freak family lived, death was an ever-present part of life, especially for the very young. The sorrow would have been deep, but the rites were often simple and devoid of the comforts that might be associated with funerals for adults.

The casket, most likely a simple pine box, would have been carried by hand or transported in a cart, depending on the family’s means. A small child like Philip might not have had a marked grave, his resting place, like so many others, might have been in an open communal grave, where the remains of many others were laid side by side. The process of laying an infant to rest would have been swift, the grave often not even marked by a proper headstone, as families, especially those of modest means, could rarely afford such markers. The grave would be unceremonious, the earth piled over him quickly, as other mourners were likely waiting to be buried there as well.

The burial at Manor Park Cemetery would have been no different. The open grave, where Philip was laid to rest alongside other recently deceased children, would have been filled quickly. No individual markers for each person, just a shared resting place where many were buried together, sometimes without names even being recorded, except in the most official of registers. The only lasting memory of a child like Philip would have been in the family’s heart, for, in an era of great mortality, particularly for children, the dead were quickly laid to rest, and the living were left to carry on.

In those days, funerals for infants were often an act of closure, a way of putting a child’s death behind them, even as the grief continued. For a mother like Eliza, the pain of the loss would have lived on, the memory of her beloved son forever etched in her mind. But life went on, as it always did, and with every passing, the family was reminded of the fragile, fleeting nature of life itself.

Manor Park Cemetery and Crematorium, situated in the London Borough of Newham, was established in 1874 and has been serving the local community since its inception. The original structures, including chapels, a lodge, and the main entrance, were constructed in 1877. These buildings suffered significant damage during World War II, particularly on July 23, 1944, when enemy action led to the destruction of the chapel, leaving only its tower standing. In 1955, the cemetery expanded its services by opening a crematorium at the center of its grounds. This facility includes a columbarium, pavilion, woodland glade, and a remembrance garden, providing various options for memorialization. The cemetery spans approximately 43 acres and has been the final resting place for nearly 387,000 individuals, making it one of the largest cemeteries in East London. Among those interred are notable figures such as Annie Chapman, a victim of Jack the Ripper, and Jack Cornwell, a posthumous Victoria Cross recipient. Additionally, some victims of the 1943 Bethnal Green air-raid shelter disaster are buried here. The cemetery's design and location have allowed it to become a haven for wildlife, featuring areas of woodland, rough grassland, and mature trees, which contribute to its serene environment. Throughout its history, Manor Park Cemetery has adapted to the evolving needs of the community, maintaining its commitment to providing dignified burial and cremation services. Its rich heritage and tranquil setting continue to offer solace to those who visit and honor the memories of their loved ones.

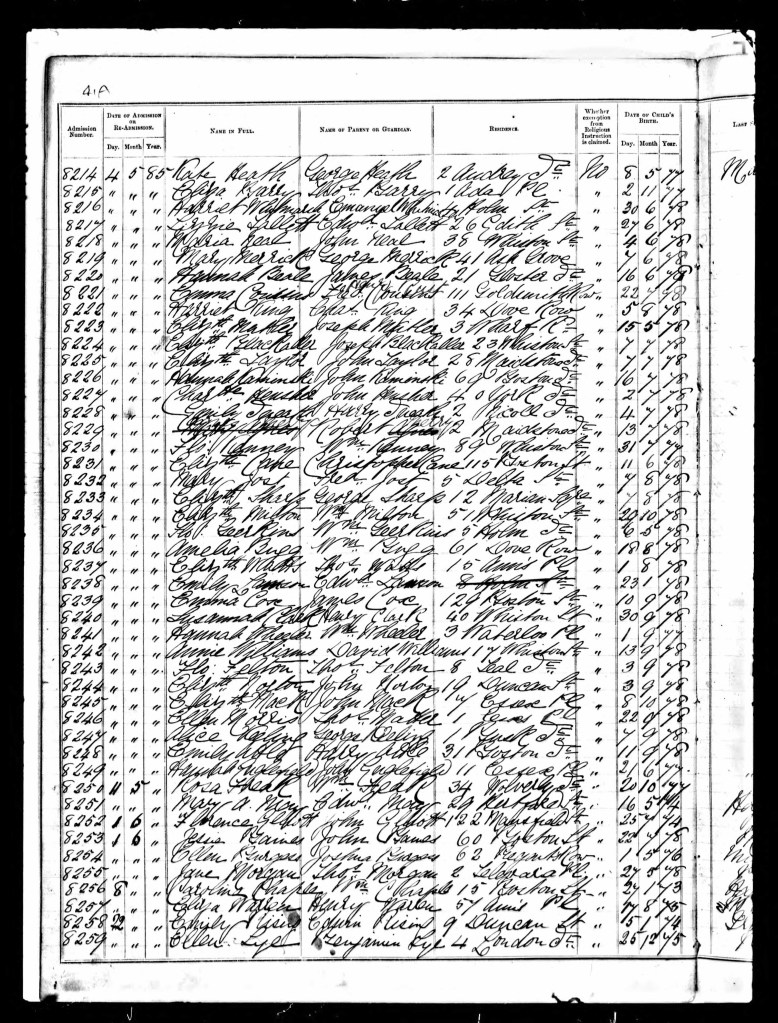

On Monday, the 11th day of May, 1885, Rosa Alice Freak’s name was officially recorded in the School Admissions and Discharges register for Maidstone Street School. It was a small yet significant moment in her young life, a step toward education, a glimpse of structure and learning in a world that had already shown her both love and hardship.

Her father, William, was listed as her guardian, a formal acknowledgment of his role in her upbringing. The family’s home address was recorded as Wolverley Street, Bethnal Green, Middlesex, a place they had called home through both joy and sorrow. It was here, just months before, that they had lost Rosa’s baby brother, Philip Henry. Life carried on, as it always did, and now Rosa was beginning a new chapter, one that would take her into the classrooms of Maidstone Street School.

For a working-class girl in Victorian London, education was not something to be taken for granted. Many children, particularly girls, never had the opportunity to attend school regularly, often pulled away by the demands of home life or the necessity of contributing to the family income. But Rosa was given this chance, a chance to learn, to grow, to be part of a school community. What she must have felt on that first day is impossible to know. Was she excited? Nervous? Did she clutch her slate and chalk with pride, or was she overwhelmed by the noise and the unfamiliarity of the classroom?

Bethnal Green was an area filled with children just like Rosa, many from large families, many facing the same struggles. Maidstone Street School would have been a place of both order and discipline, where children learned the basics of reading, writing, and arithmetic under the watchful eyes of strict teachers. Lessons were repetitive, designed to instill knowledge through rote memorization, and for many, the experience of school was as much about learning obedience as it was about education.

Still, for Rosa, this school record is more than just an entry in an old ledger, it is a reminder that she was there, that she had a childhood, that she took her place among the other children of Bethnal Green, ready to learn, ready to face whatever the future would bring.

Maidstone Street School, located in the Haggerston area of London, was established between 1873 and 1874. Designed by architects C.H. Mileham and Kennedy for the Hackney Division of the School Board for London, the school was part of a broader initiative to provide education to the growing population of East London during the late 19th century.

In 1894, the school underwent significant expansion under the direction of T.J. Bailey, the architect for the School Board for London. This expansion included the addition of a detached combined cookery centre and schoolkeeper's house, reflecting the period's emphasis on practical skills in education.

Over time, Maidstone Street itself ceased to exist, leading to the school's renaming as Sebright Primary School. Despite these changes, the original Victorian-era architecture has been preserved, and the building continues to serve the local community as an educational institution.

Unfortunately photographs of Maidstone Street School are scarce.

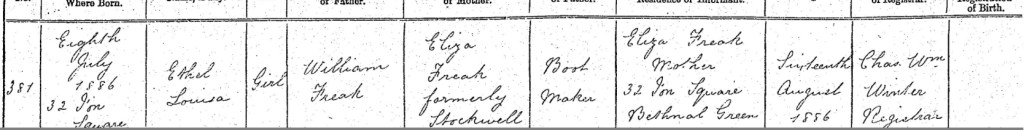

On Thursday, the 8th day of July, 1886, Rosa’s mother, Eliza, gave birth to another daughter, Ethel Louisa Freak, at the family’s home, Number 32, Ion Square, Bethnal Green, London. It was another summer baby for the Freak family, another child welcomed into a home that had already known both the joy of new life and the heartbreak of loss.

A little over a month later, on the 16th day of August, Eliza made the journey to the Bethnal Green Register Office, carrying the weight of yet another official duty as a mother. It was a familiar process by now, one she had undertaken many times before, but no less significant. There, the registrar, Chas William Winter, carefully recorded the details of Ethel’s birth in the register: her full name, her birthdate, and the details of her parents, William Harry Freak, a bootmaker, and Eliza Freak, formerly Stockwell, of 32 Ion Square.

For Rosa, now nearly nine years old, the arrival of another baby sister would have been a mix of excitement and familiarity. She had grown up in a household full of siblings, where the cries of a newborn were not an unusual sound. Did she rush to her mother’s side, eager to hold Ethel’s tiny hand? Did she help soothe her when she cried or watch curiously as Eliza rocked her gently to sleep?

Ion Square, like much of Bethnal Green, was home to many working-class families like the Freaks, where space was tight, and life was not always easy. But amidst the struggles, there was love, love that carried them through hardship, love that welcomed new life with open arms. Ethel’s birth was another thread woven into the tapestry of their family’s story, a story that would continue to unfold, one chapter at a time.

Ion Square is a small public park located in Bethnal Green, East London, within the historic county of Middlesex. The area has long been associated with working-class communities and the rapid urbanization that characterized much of East London during the 19th century.

Originally, this part of Bethnal Green was densely populated with housing built to accommodate the growing numbers of workers drawn to London's expanding industries. During the 19th century, East London saw significant poverty and overcrowding, leading to efforts to create open spaces for public health and recreation. Ion Square was developed as one such space, providing greenery and a respite from the surrounding tightly packed streets.

The park itself was once surrounded by traditional Victorian terraces, many of which have since been replaced by post-war housing developments. The transformation of Ion Square reflects the broader changes in Bethnal Green, from its industrial past to its current status as a more gentrified and diverse community. Today, it serves as a peaceful green space enjoyed by residents, retaining elements of its historic character while adapting to the needs of a modern urban environment.

Bethnal Green has a long and rich history, shaped by waves of migration, the impact of World War II bombings, and the social reforms of the 20th century. Ion Square, though a relatively small part of this story, is emblematic of the shifts in urban planning and the push to improve living conditions in East London.

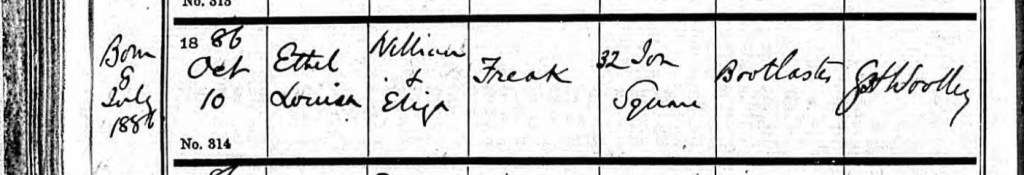

On Sunday, the 10th day of October, 1886, Rosa’s baby sister, Ethel Louisa Freak, was carried into St Peter’s Church in Bethnal Green to be baptized. It was a crisp autumn day, and as the bells of the church rang out over the tightly packed streets of East London, the Freak family gathered for this small but meaningful occasion.

The baptism was performed by S.H. Woolly, who carefully recorded the details in the parish register. Ethel’s father, William, was listed as a Boot Laster, a trade that had supported the family for years, and their home was noted as Number 32, Ion Square. For William and Eliza, this was not just a routine event, it was an affirmation of faith, a way of entrusting their child’s soul to God, as was common in Victorian England.

Rosa, now a young girl of nine, would likely have stood close by, watching as her little sister was held over the font, the cold water trickling onto her forehead as sacred words were spoken. Did she feel a sense of pride? A sense of protectiveness? Or was she simply curious, taking in the grandeur of the church, the solemnity of the service, the soft murmurs of prayers echoing in the stone walls?

In a world where infant mortality was heartbreakingly common, baptisms were more than just a spiritual rite; they were a moment of hope, a way of acknowledging a child’s place in the family and the wider community. Whatever struggles lay ahead for the Freaks, on this day, there was celebration, a moment of light amidst the everyday challenges of life in Bethnal Green.

St Peter's Church, located in Bethnal Green, London, is a 19th-century Anglican church with a rich history. Designed by architect Lewis Vulliamy, the church was completed in 1841 in a neo-Norman style. It was constructed as part of the Metropolis Churches Fund, an initiative aimed at providing places of worship in rapidly expanding urban areas during the 19th century.

The church's architecture is notable for its use of flint facework on brick cores, complemented by Bath stone and terracotta dressings. This design choice contributes to its distinctive appearance. In the early 20th century, vestries were added to the east end of the building, enhancing its functionality.

St Peter's Church has played a significant role in the local community since its establishment. By 1853, Bethnal Green had 12 churches, including St Peter's, which collectively served the spiritual needs of the area's residents. These churches were supported by 22 clergymen, 129 district visitors, and 244 Sunday school teachers, reflecting the importance of religious institutions in the social fabric of the time.

In recent years, St Peter's Church has continued to adapt to the needs of its congregation. In the summer of 2010, the church entered into a partnership with St Paul's Shadwell to revitalize its community presence. This collaboration led to significant growth in the congregation and the development of various community projects, underscoring the church's ongoing commitment to serving Bethnal Green.

However, the church has also faced challenges. In 2023, ceiling panels fell, causing asbestos contamination and resulting in the temporary closure of the building. While the ceiling has been restored, additional work remains, including cleaning the organ and addressing external repairs. Trees have also caused damage to the churchyard railings, indicating ongoing maintenance needs.

Despite these challenges, St Peter's Church remains a significant historical and architectural landmark in Bethnal Green, reflecting the enduring legacy of 19th-century church-building efforts in London's East End.

On Monday, the 9th day of May, 1887, Rosa Alice Freak’s name was once again recorded in the Admissions and Discharges register for Maidstone Street School. It was another step in her education, another small but significant entry in the records that help piece together her early years.

Her father, William, was again listed as her guardian, his name standing beside hers as a quiet reminder of his role in her life. Their home address was now recorded as Number 32, Ion Square, Bethnal Green, Middlesex, another move for the family, another chapter unfolding. Life in the crowded East End meant frequent changes in residence, as families sought better opportunities, cheaper rents, or simply tried to stay afloat amidst the daily struggles of working-class life.

By this time, Rosa was nearly ten years old, likely accustomed to the rhythms of school life. Did she walk the familiar streets to Maidstone Street School with a sense of routine, or did she still feel the anticipation of each new school term? Education was not guaranteed for girls of her social class, and for many families, the need for extra hands at home or additional income often outweighed the benefits of school. But Rosa’s continued presence in the school records suggests that her parents valued her education, that they wanted more for her than a life confined to household duties or factory work.

At Maidstone Street School, the lessons would have been strict and structured, reading, writing, arithmetic, and moral instruction. The wooden desks, the slate boards, the repetitive recitations, these were the tools that shaped her learning. Was she a keen student, eager to absorb knowledge? Or did she, like many children, find the discipline of the Victorian classroom a challenge?

No matter how she felt about her lessons, one thing is certain: Rosa’s name in that school register is proof that she was there, that she walked through those doors, sat among her classmates, and played in the schoolyard. It is a small but powerful reminder that her story, like so many others, was shaped not just by the hardships of her time, but by moments of learning, growth, and the quiet hope of something more.

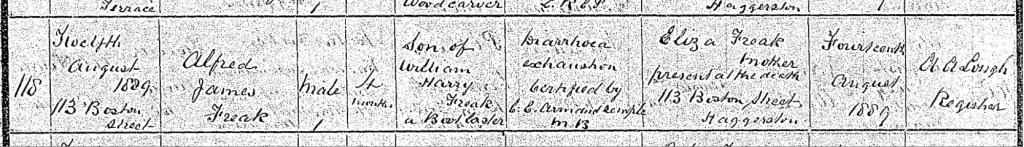

On Thursday, the 11th day of April, 1889, Rosa Alice Freak welcomed another sibling into the world, her baby brother, Alfred James Freak. Born at the family’s home at Number 113, Boston Street, Shoreditch, London, Alfred arrived into a world that was already bustling with the sounds of a growing family, where love and hardship walked hand in hand.

For Eliza, it was yet another chapter in her journey as a mother. With so many little ones to care for, each new birth must have brought both joy and worry, joy for the new life she cradled in her arms and worry for what the future might hold. Life in the crowded streets of Shoreditch was far from easy, and every child born into a working-class family faced struggles from the very start.

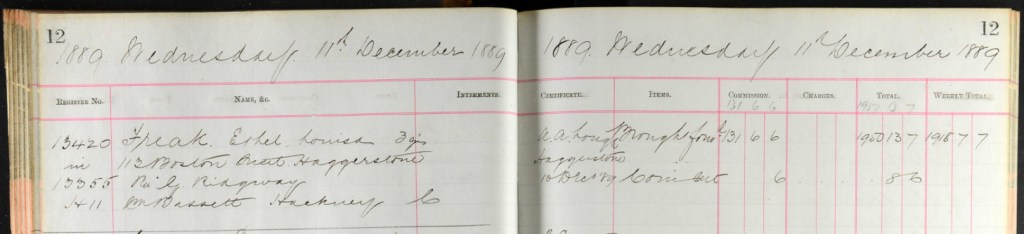

On Monday, the 20th day of May, Eliza made her way to the Shoreditch Register Office to officially record Alfred’s birth. Perhaps she carried him with her, wrapped tightly against the chill of a London spring, or perhaps she left him in the care of his older siblings, trusting them to watch over their tiny brother while she fulfilled this necessary duty. The registrar, A. A. Loughgall, recorded the details in the birth register, noting that Alfred James Freak had been born on the 11th of April to William Harry Freak, a Boot Laster, and Eliza Freak, formerly Stockwell, of 113 Boston Street, Haggerston.

For Rosa, now eleven years old, the arrival of another sibling was likely nothing new, she had already seen so many come and go, had held tiny hands and watched as her mother soothed newborn cries. Did she rush to meet Alfred, eager to claim the role of big sister once again? Or was she already accustomed to the constant change, another baby simply another part of life in a large Victorian family?

Whatever the case, Alfred’s birth added another thread to the tapestry of the Freak family’s story, another name in the long list of children who would share in the struggles and triumphs of working-class life in the heart of London.

Boston Street was a historical street located in the Shoreditch area of London, specifically at 309 Hackney Road, E2. In the early 20th century, particularly around 1921, the street was home to various businesses and residents. Notable establishments included Mrs. Emma Eliza Crabb, a beer retailer at number 39; Joseph William Lane, who operated a chandler's shop at number 71; the Suffolk Arms, a public house managed by Frances East at number 76; Mrs. Emma Powley, another chandler at number 94; and Robert Holsworth, a sack and bag maker with premises at numbers 103 and 105.

Over time, urban development and redevelopment projects led to significant changes in the Shoreditch area. Many streets, including Boston Street, underwent transformations, with some being renamed, altered, or disappearing entirely due to new construction and city planning initiatives. These changes reflect the dynamic nature of London's urban landscape, where historical streets often give way to modern developments, reshaping the character of neighborhoods like Shoreditch.

Today, Boston Street no longer exists in its original form, and its history is preserved through records and archives that document the evolution of Shoreditch's streets and communities.

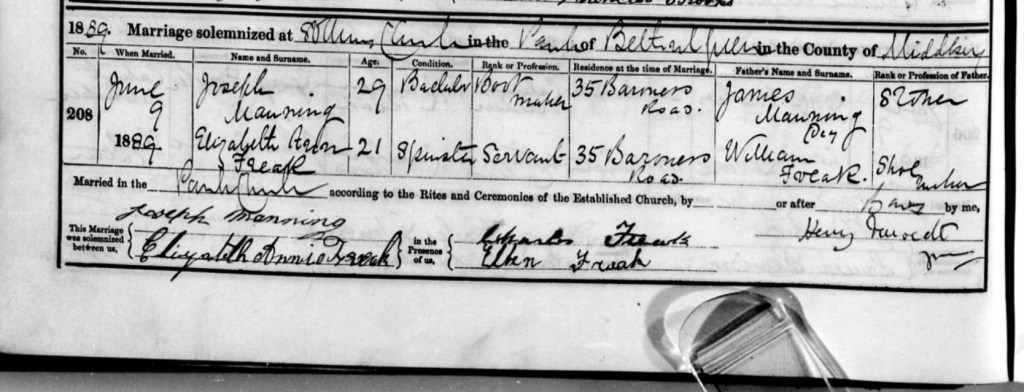

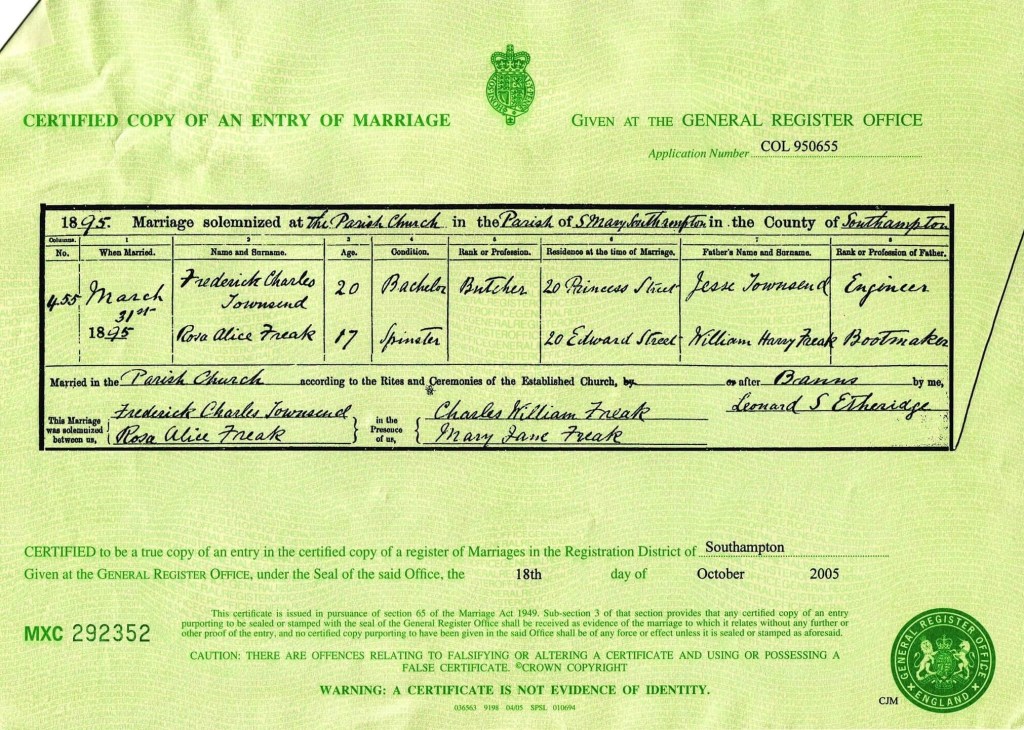

On Sunday, the 9th day of June, 1889, in the heart of Bethnal Green, Rosa’s eldest sister, Elizabeth Annie Freak, stood at the altar of St Thomas’s Church, ready to begin a new chapter of her life. At 21 years old, she was a young woman stepping into marriage, leaving behind her family home to build one of her own. Beside her stood Joseph Daniel Manning, a 29 year old bachelor, a man who, like her father and brothers, worked in the boot trade.

The church, with its solemn stone walls and the scent of candle wax and old wood, bore witness to a moment both ordinary and extraordinary. Marriage in Victorian England was as much about practicality as it was about love. Elizabeth, listed in the marriage register as a servant, had likely known a life of hard work, of long hours and little rest. But this day was hers, a day of promise and new beginnings.

The officiant, Henry, his surname blurred by time, led the couple through their vows, his voice echoing beneath the church’s high ceiling. As Elizabeth spoke the words that bound her to Joseph, she was not just becoming a wife; she was securing her future in a world where a woman’s options were few.

The register recorded that both Elizabeth and Joseph were living at Number 35, Burmers Road. Whether their courtship had blossomed under the same roof or if fate had drawn them together in the boot-making trade, their paths had now fully intertwined. Elizabeth’s father, William Freak, was noted as a shoemaker, a trade that had provided for the family for generations. Joseph’s father, James Manning, was a stoker, a man who likely toiled in the heat and grime of the industrial world. Their sons had each followed their own paths, but this marriage brought their families together.

Among the witnesses who signed their names that day were Charles Freak, Elizabeth’s brother, and Eliza Freak, their mother. Perhaps Charles, steady-handed, signed his name with quiet pride, while Eliza, no stranger to the joys and sorrows of family life, watched her daughter with a mixture of happiness and wistfulness. Had she thought back to her own wedding day, to the years of love and struggle that had followed?

And then, just like that, it was done. The signatures were inked, the vows spoken. Elizabeth Annie Freak became Elizabeth Manning. As she stepped out of St Thomas’s Church, the weight of her new name settling over her, she was no longer just a daughter or a sister, she was now a wife, with a life of her own to build.

That special day, Sunday the 9th day of June, 1889, was not only a celebration of love and new beginnings for Elizabeth Annie Freak and Joseph Daniel Manning but also a rare moment captured in time, one that holds significance beyond the wedding itself. It was on this day that the photograph of Rosa and her sister Emily was taken, a treasured image that offers a glimpse into their bond.

Standing together, dressed for the occasion, Rosa and Emily were part of a family gathering filled with laughter, anticipation, and the promise of the future. The wedding of their elder sister was an event that brought everyone together, and in that fleeting moment when the photograph was taken, a lasting memory was created.

For those who have searched for traces of Emily in official records, this image is all the more precious. Though her name is absent from birth indexes, she stands there beside Rosa, a tangible presence within the family. The photograph, much like the wedding itself, serves as a reminder of the ties that bound them, the love they shared, and the fleeting yet unforgettable moments that shaped their lives.

St Thomas Church in Bethnal Green, London, was originally located on Baroness Road. Unfortunately, the church was demolished in 1958, and images of it are scarce. However, the church was later merged with St Peter's Church, and the combined parish is now known as St Peter with St Thomas. St Peter's Church, designed by architect Lewis Vulliamy, was built between 1840 and 1841 and is located at St Peter's Close, Bethnal Green. The church features a distinctive neo-Norman architectural style with a broad nave, west tower, and shallow chancel.

On a summer’s Monday, the 24th day of June, 1889, Rosa’s baby brother, Alfred James Freak, was carried into the sacred space of St Augustine’s Church in Haggerston to be baptized. It was a warm summer day, and as the family made their way through the bustling streets of Shoreditch, the weight of tradition and faith guided their steps.

The minister, Edward P., presided over the ceremony, carefully recording the details in the baptism register. William was noted as a Boot Laster, a trade that had been the backbone of the family’s livelihood, and their home was listed as Number 111, Boston Street. Though the baptism was a spiritual occasion, it was also a deeply practical one. In an era of high infant mortality, baptisms were not only a declaration of faith but an act of protection, a way of ensuring a child’s place in heaven should the worst happen.

For Eliza and William, this was a familiar ritual, one they had carried out for many of their children before. But no matter how many times they stood at the font, watching as a minister’s hand poured cool water over their child’s forehead, each baptism held its own significance. This was their way of presenting Alfred to the world, of affirming his place in their family and in the eyes of God.

Rosa, now on the cusp of adolescence, would have witnessed many such ceremonies over the years. Did she watch solemnly as her brother was welcomed into the faith, or did she steal glances at the grand stained-glass windows, letting her mind wander as the priest spoke? Perhaps she held her mother’s hand, sensing the mix of pride and quiet worry that always seemed to linger in moments like these.

No matter what the day held for each member of the family, Alfred’s baptism was more than just an entry in a parish register. It was a moment of unity, of devotion, and of hope, a quiet but significant milestone in the ever-growing story of the Freak family.

St. Augustine's Church in Haggerston, Middlesex, was established in the mid-19th century to serve the spiritual needs of a rapidly growing population in East London. As part of the Haggerston Church Scheme, which aimed to provide places of worship in this densely populated area, the church was constructed between 1866 and 1867. The renowned architect H. Woodyer designed the building, and the foundation stone was laid in late 1865. The consecration ceremony took place on April 12, 1867. The church was built on a somewhat constrained site, surrounded by other buildings, which presented challenges during its construction. Despite these limitations, St. Augustine's became a significant landmark in the community. In the late 1960s, the church was closed, reflecting broader changes in the area's demographic and social landscape. Following its closure, the building found new life as the 291 Gallery, repurposed for artistic and cultural events. This adaptive reuse preserved the historic architecture while providing a space for contemporary arts. Today, the former St. Augustine's Church stands as a testament to the area's rich history, embodying the architectural and cultural transformations that have shaped Haggerston over the past century and a half.

As Summer was slowly turning to autumn, on Monday, the 12th day of August, 1889, in the quiet of their home at Number 113, Boston Street, Haggerston, Shoreditch, Rosa’s baby brother, Alfred James Freak, slipped away from this world. He was just four months old. His mother, Eliza, was with him as he took his final breaths, cradling him in her arms, her heart breaking with each passing moment. She had known the frailty of infant life all too well, but nothing could prepare a mother for this kind of loss.

Two days later, on Wednesday, the 14th day of August, Eliza carried the weight of her grief to the Shoreditch Register Office. It was a journey no parent should ever have to make, but one she had made before. The registrar, A.A. Lough, carefully recorded the details in the death register: Alfred James Freak, just four months old, had passed away at home. His father, William Harry Freak, was listed as a Boot Laster, the trade that put food on their table but could not shield them from the cruel hand of fate.

The cause of death, diarrhoea and exhaustion, was all too common among infants in the crowded streets of London. Without modern sanitation or the medical advancements we now take for granted, sickness spread easily, and even the strongest mothers could do little more than watch, pray, and hope. The doctor who had certified Alfred’s passing, Charles Edward Armand Semple, was a man of medicine and science, the author of books on pathology and toxicology, but in the end, even his knowledge could not save the tiny boy.

Rosa, just eleven years old, had already seen more loss than many would in a lifetime. She had watched her mother weep before, had seen the quiet sadness in her father’s eyes. She had said goodbye to little Philip Henry five years before, and now, another baby brother was gone. Did she understand the finality of it, or did she still hold onto the innocent hope that one day, she might see them again?

Alfred’s short life left only a few official traces, a birth record, a baptism entry, and now, a sorrowful entry in the death register. But to those who loved him, he was more than just a name on paper. He was a son, a brother, a little soul who had been cradled and cherished, even if only for a few fleeting months.

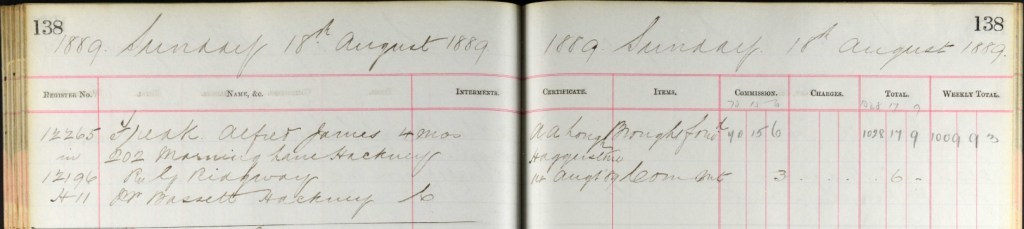

On Sunday, the 18th day of August, 1889, Rosa’s baby brother, Alfred James Freak, was laid to rest at Chingford Mount Cemetery in Waltham Forest, Greater London. The summer air must have hung heavy with sorrow as the family made the solemn journey to say their final goodbye. At just four months old, Alfred had known only the warmth of his mother’s arms, the lull of her voice, the gentle rhythm of his home in Boston Street. And now, he was gone.

His tiny body was lowered into Grave Number 12196, in Cemetery Section H 11, a resting place among countless others who had left this world too soon. His interment number, 12265, was a cold, administrative detail, just another in the endless records of London’s dead. But to his family, he was not a number. He was their son, their brother, a piece of their hearts that would never be whole again.

For Rosa, standing at the graveside, the weight of loss must have pressed down on her small shoulders. She had been here before, mourning another little brother, Philip Henry, just five years earlier. How many times could one family endure such heartbreak? Did she reach for her mother’s hand, sensing the silent grief that words could never express? Did she wonder why the world was so cruel to the tiniest, most innocent souls?

There were no elaborate coffins for infants of working-class families, no grand memorials. Infant funerals in 1889 were simple affairs, often dictated by what little money the family could spare. A small, modest coffin, a brief service, a moment of quiet before the earth was gently placed over him. Sometimes, families borrowed coffins for the wake, returning them after the burial to save money. Mourners dressed in their best, even if “best” was only a well-worn black shawl or a borrowed suit.

The burial of a child was an all-too-common tragedy in Victorian London. Disease, poor sanitation, and malnutrition claimed the lives of so many little ones, and grieving parents were expected to carry on, to keep working, to push forward even as their hearts ached. But no matter how often death visited a family, it never became easier.

As the final prayers were spoken over Alfred’s grave, Rosa’s mother, Eliza, must have clutched the memory of her baby boy tightly. The world would move on, but she would never forget the brief but precious months she had with him. And Rosa, still a child herself, was learning a painful truth about life, love and loss would forever walk hand in hand.

Chingford Mount Cemetery, located in the London Borough of Waltham Forest, was established in 1884 by the Abney Park Cemetery Company. This expansion aimed to address the overcrowding at their original site in Stoke Newington. The cemetery occupies land previously known as the Mount Caroline Estate, named after Caroline Mount, the wife of a former landowner.

The cemetery spans over 41 acres and was officially opened in May 1884 by Sir Robert Fowler, the Lord Mayor of London at the time. Designed as a non-conformist burial ground, it features a grand avenue lined with London plane trees leading to the ivy-covered ruins of the old Chingford church, creating a picturesque setting.

Throughout its history, Chingford Mount Cemetery has faced challenges, including neglect and vandalism. In 1975, plans to develop unused portions of the cemetery for housing were met with strong opposition from local residents, leading to the rejection of the proposal. Subsequently, the cemetery experienced periods of neglect, with its chapel and lodges suffering damage from vandalism, culminating in the destruction of the chapel by fire, resulting in the loss of nearly all its records.

The cemetery is the final resting place for several notable individuals, including members of the infamous Kray family. Both Ronnie and Reggie Kray, along with their brother Charlie, parents Violet and Charlie, and Reggie's first wife Frances, are interred in the family plot at Chingford Mount.

Chingford Mount Cemetery also holds historical significance for its war graves. It contains 139 Commonwealth burials from World War I and 182 from World War II. For those whose graves are not individually marked, a low screen wall memorial surrounds the main war graves plot, with a Cross of Sacrifice located at the end of Plot E8.

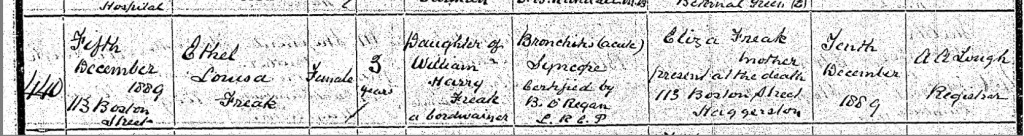

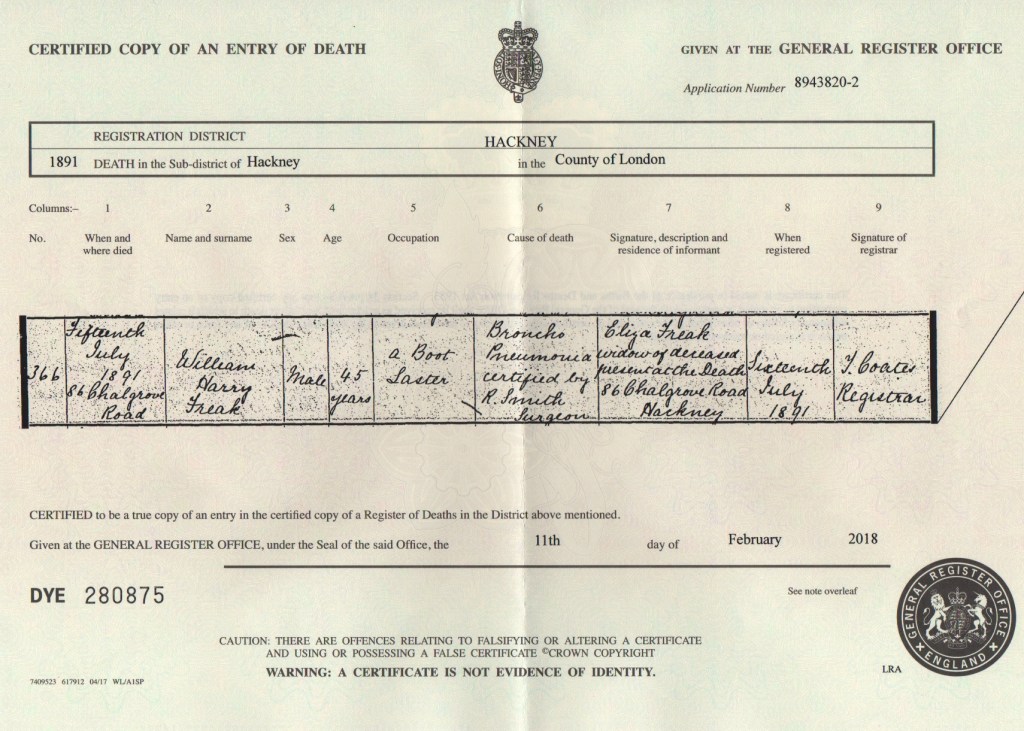

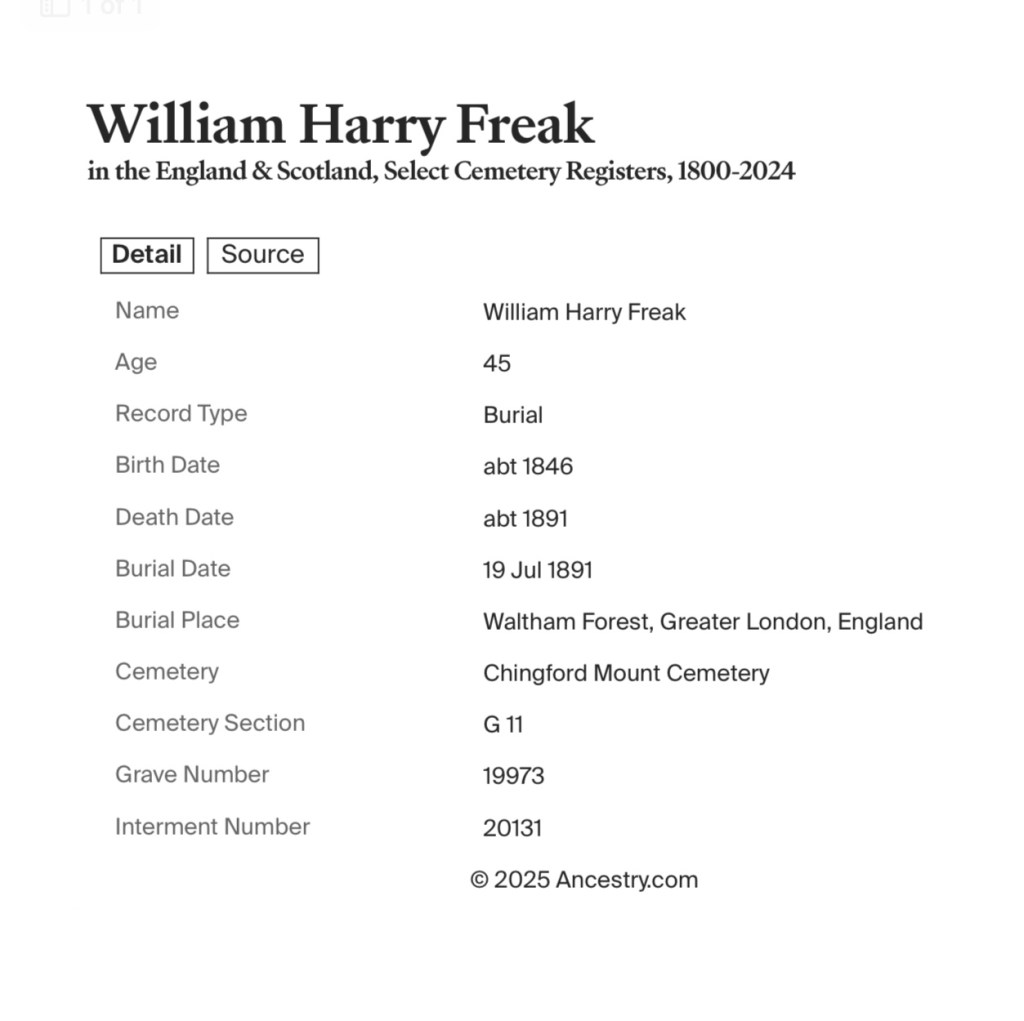

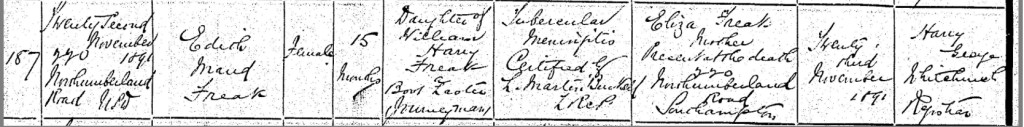

The cold grip of December 1889 must have felt even harsher for Rosa’s family as they endured yet another devastating loss. On Thursday, the 5th day of December, in the familiar surroundings of their home at 113 Boston Street, five year old Ethel Louisa Freak took her final breath. She had been battling acute bronchitis, her little body struggling against the relentless illness. In the end, it was syncope, a sudden loss of blood flow to the brain, that stole her away.

Eliza, her mother, had been there, as she had been for all her children. She had soothed Ethel through fevered nights, hoping, praying that this sickness would pass. But it didn’t. The house that had so recently heard the laughter of a five-year-old girl now echoed with a silence that would never quite be filled.

And then came the heartbreaking duty that no mother should have to face. On Tuesday, the 10th day of December, Eliza made the sorrowful journey to register Ethel’s death. The registrar, A. A. Lough, carefully recorded the details in the death register, his pen scratching out the painful truth that no paperwork could ever fully capture. Five-year-old Ethel Louisa Freak, daughter of William Harry Freak, a cordwainer, and Eliza Freak of 113 Boston Street, had died from bronchitis and syncope. The official cause of death was certified by Dr. B. O. Regan, but no doctor could mend the broken hearts left behind.

For Rosa, the loss of her little sister must have been another cruel lesson in the fragility of life. Just four months earlier, she had watched her family mourn the passing of baby Alfred, and now, so soon after, she faced yet another goodbye. Did she stroke Ethel’s golden hair one last time, whispering childhood secrets they would never share again? Did she cling to her mother, desperate for comfort, knowing in her young heart that this was a pain too deep for words?

In the cruel winter of 1889, death was a frequent visitor in the crowded streets of Haggerston. The damp, the cold, the ever-present smog of London, all of it weighed heavy on families like the Freaks. Children were particularly vulnerable. Even something as common as bronchitis could turn fatal when mixed with poor living conditions, inadequate medical care, and the relentless hardships of working-class life.

As the days moved forward, life would have had to continue. There were boots to be made, meals to be cooked, and other children to care for. But in the quiet moments, when no one else was looking, Rosa’s mother must have wept for the little girl she had carried, nursed, and loved beyond measure. And Rosa, growing up far too fast, would carry the memory of Ethel Louisa in her heart, another name in the long, painful list of those she had loved and lost.

On a bitterly cold Wednesday, the 11th day of December, 1889, the Freak family gathered once more at Chingford Mount Cemetery to say goodbye to their beloved Ethel Louisa. Just four months earlier, they had stood in this very place, mourning the loss of baby Alfred. Now, heartbreakingly, they were back, laying five year old Ethel to rest.

She was interred in grave number 13355, within section H11, the same section where her baby brother had been buried. Though their small bodies were not placed together, there was some small comfort in knowing that they now rested in the same quiet corner of the cemetery. Perhaps, in the minds of their grieving family, the two siblings would find each other in the beyond, playing as they once had in life.

The December air would have bitten at the mourners as they stood by the open grave. The sky, likely a bleak London grey, matched the heaviness in their hearts. A simple wooden coffin, perhaps adorned with a small bunch of flowers, whatever they could afford, was lowered into the earth. The words of the burial service, familiar yet always unbearable, spoke of hope and resurrection. But how difficult it must have been for Eliza and William to believe in hope when they had now buried two of their precious children in the space of months.

For Rosa, still a young girl herself, this must have been yet another painful, confusing moment in a childhood already marked by loss. She had played with Ethel, shared laughter and whispered secrets with her, and now, she had to say goodbye. How does a child make sense of death when it comes so often, stealing away the people they love?

As the service ended and the family slowly walked away from the grave, the weight of grief must have been unbearable. But life, as always, demanded to continue. There were still children to care for, work to be done, and a harsh winter to survive. And so, with heavy hearts, they left their little girl behind, nestled in the cold December earth, forever five years old.

In the warmth of their family home at Number 113, Boston Street, Haggerston, Shoreditch, London, Eliza Freak brought another child into the world. On Saturday, the 2nd day of August, 1890, she gave birth to a daughter, Edith Maud Freak.

After the sorrow of losing Ethel just months before, Edith’s arrival must have been a bittersweet moment for William and Eliza. The grief of burying two children in the past year still hung over them, but here was new life, a reminder that, despite their losses, their family continued to grow. A tiny, fragile hope in the form of their newborn daughter.

On Thursday, the 11th day of September, Eliza made her way to the registrar’s office to officially record Edith’s birth. A familiar task, one she had done many times before, but each time significant. A. A. Lough, the registrar, carefully wrote down the details in the birth register: Edith Maud Freak, daughter of William Harry Freak, a Boot Laster, and Eliza Freak, formerly Stockwell. Their address remained 113 Boston Street, the same home where Edith had taken her first breath, and where, not long ago, her siblings had taken their last.

For Rosa, now nearly thirteen, another baby sister must have brought both joy and trepidation. She had seen how fragile life could be, how easily it could slip away. But for now, there was a new baby to hold, to soothe, to sing to sleep. A new child to love, in a family that had already known so much heartbreak.

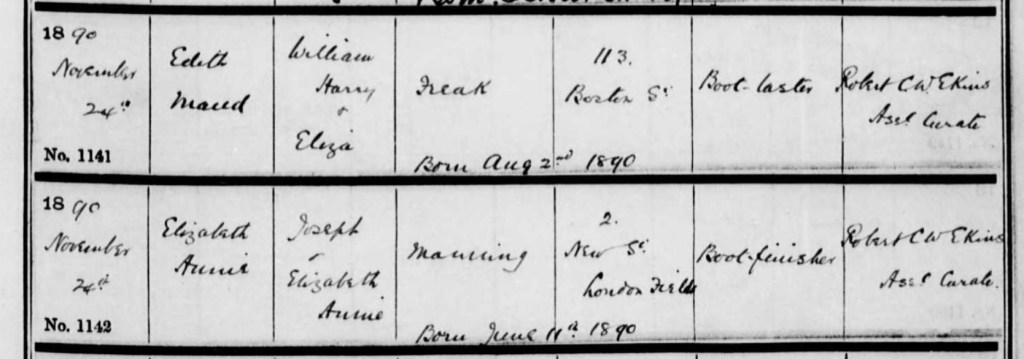

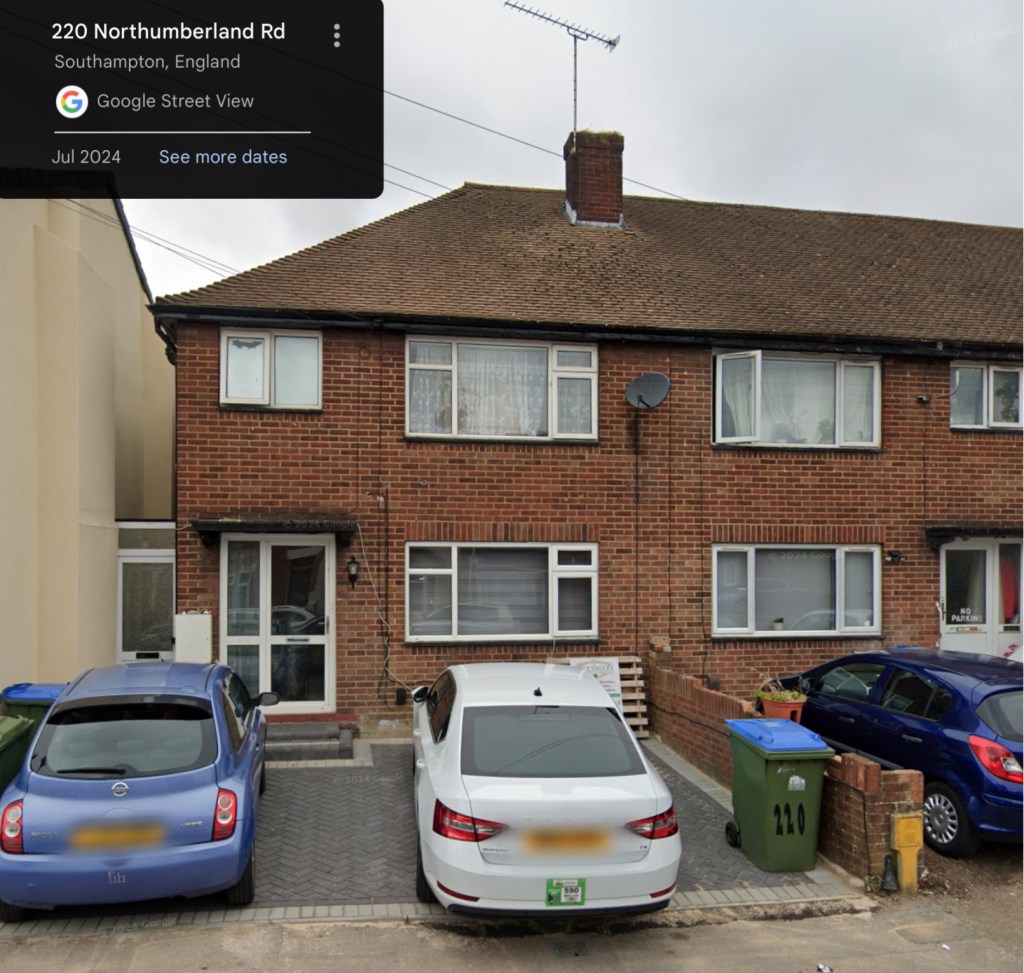

On a crisp Monday, the 24th day of November, 1890, Rosa’s parents, William and Eliza, carried their youngest daughter, Edith Maud Freak, to St Augustine’s Church in Haggerston for her baptism. The ceremony was a shared family occasion, as Rosa’s niece, Elizabeth Annie Manning, daughter of Joseph Manning and Rosa’s sister, Elizabeth Annie Manning (née Freak), was also baptised that day.