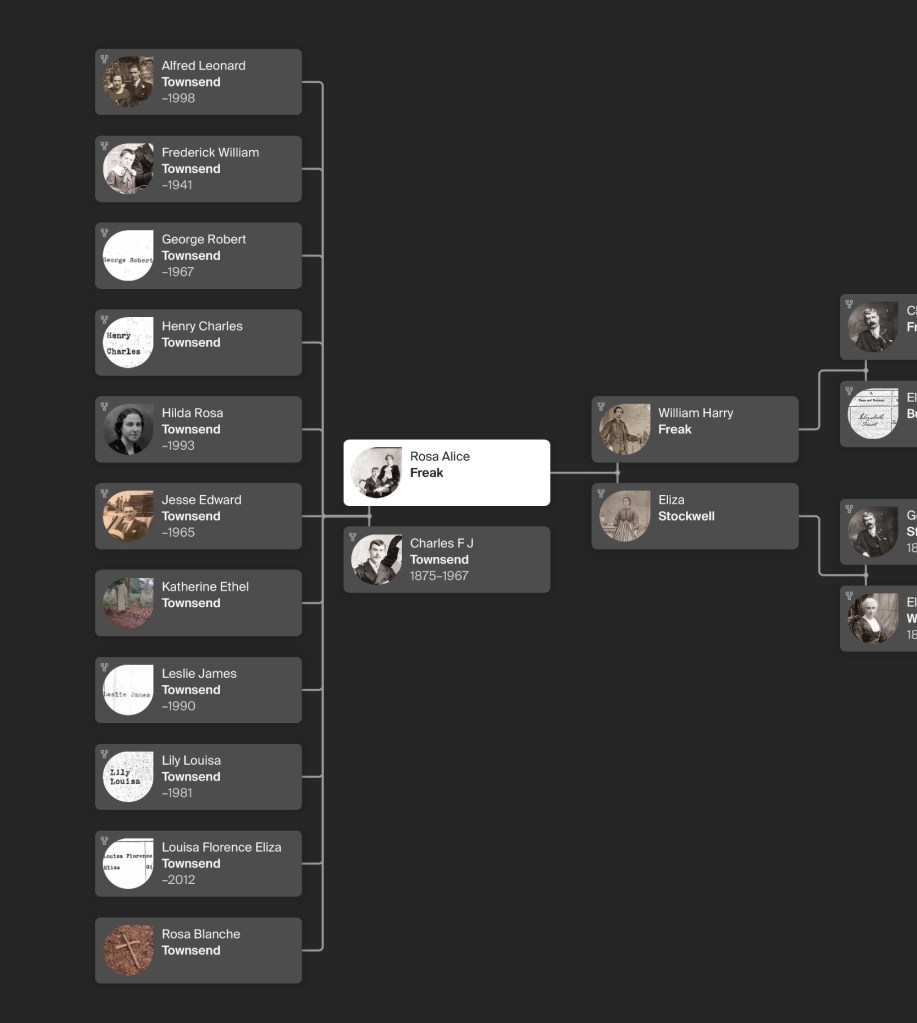

As I sit down once again to revisit the life of my maternal 2nd great-grandmother, Rosa Alice Freak, I find myself approaching her story with a deeper understanding and a changed perspective. It has been years since I first documented her life while taking part in the “52 Ancestors in 52 Weeks” challenge, and in that time, my writing has grown, my research has expanded, and my connection to Rosa has only strengthened. Her story is not just one of sorrow and hardship, though there was plenty of both, her life was also filled with love, resilience, and the family she built despite the tragedies that shaped her.

Rosa’s early years were marked by devastating loss. Born in 1877, she was raised in a working-class family in the heart of London, the daughter of William Harry Freak, a bootmaker, and Eliza Stockwell. Her childhood was spent in a home filled with love, yet overshadowed by grief. One after another, Rosa lost her baby brothers and sisters, Philip, Alfred, Ethel, and Edith, each loss leaving a wound that never fully healed. Then, when she was just fourteen, she suffered the greatest heartbreak of her young life: the death of her father, William. Watching her mother, Eliza, carry the unbearable weight of so many burials, Rosa learned that survival meant pressing on, even in the face of unimaginable sorrow.

But Rosa’s story is not just one of loss. Through it all, she found the strength to carry on, and at seventeen, she stepped into a new chapter. She stood at the altar of St Mary’s Church in Southampton, where she married Charles Frederick Joseph Townsend, whom went by the name, Frederick Charles Townsend, a young butcher who would become her partner in life’s joys and struggles. With him, she found the unwavering love that had eluded her for so long, and together, they began to build a family of their own.

Tracing one’s heritage is more than just gathering names and dates, it is about preserving the stories, honoring the lives of those who came before us, and keeping their memories alive for future generations. Old records, faded photographs, and handwritten documents may seem like mere fragments of history, but they hold the essence of our ancestors. They remind us that they lived, that they loved, that they struggled and persevered. Rosa’s story, like so many others, is one that deserves to be told, not just for what she endured, but for the legacy she left behind.

And so, as I revisit her life, I do so with a renewed commitment to telling her story as completely and as honestly as I can. Rosa’s journey was far from over when she said her vows that day in 1895, her greatest joys and her deepest heartbreaks still lay ahead. But through it all, she remained a woman of strength, a woman who knew the value of love, and a woman whose story is worth remembering.

So without further ado, I give you, part 2 of dear Rosa’s story,

The Life Of Rosa Alice Freak

1877–1965,

Until Death Do Us Part (Revisited).

Welcome back to the year 1895, Southampton, Hampshire, England. The streets are bustling with the sights and sounds of a society at the crossroads of the Victorian era, where tradition and progress intermingle in the shadow of Queen Victoria, who is still on the throne, having ruled for over half a century. The monarch, with her long reign, symbolizes the stability and conservatism of the time, though the world around her is rapidly changing.

In Parliament, the Prime Minister is Sir William Harcourt, who leads the Liberal government. The political landscape is one of growing concerns over social reform, including debates on the poor laws and the rights of women. While many political issues are still centered around the empire and colonialism, there is a quiet undercurrent of change as society begins to question the rigid structures that have long defined it.

Social standing remains strictly divided, with the upper classes still holding most of the wealth and power. The rich continue to live in relative luxury, with expansive homes, servants, and a lifestyle of leisure that allows them to indulge in the cultural offerings of the time. They are well-dressed in the finest fabrics, with women donning elaborate gowns, corsets, and large hats, while men wear tailored suits with high collars and starched shirts. Fashion is an essential marker of identity, with the latest trends quickly spreading from London to provincial towns like Southampton.

The working class, in contrast, faces a much harsher reality. Many work long hours in factories, in docks, or in small trades, and live in crowded, often unsanitary conditions. While the wealth of the nation is growing, the benefits are not equally shared. The gap between the rich and poor is glaring, and class divisions are entrenched, with the working class often struggling to make ends meet. The poor, especially those living in the slums, endure squalid living conditions, and for many, there is little hope of upward mobility.

Transportation in 1895 is still largely reliant on horse-drawn carriages, although the early stirrings of industrial innovation are being felt. In Southampton, there is the excitement of electric trams that offer a quicker way to travel around the city, and the railway system is becoming more extensive, connecting major cities with increasing ease. Cars are just beginning to appear, but they are still a novelty and too expensive for most.

Energy during this time is mostly from coal, with steam-powered engines driving industry, transport, and even electricity. However, electric lighting is slowly gaining ground in the wealthier parts of town, though gas lamps still light the streets at night. At home, the rich enjoy gas lighting, which brings a modern touch to their parlors and drawing rooms, while poorer homes rely on candles or the dim light from a single oil lamp.

Heating is also divided by class. The wealthy can afford coal fires that keep their large homes warm, while the poor make do with small stoves or fireplaces that offer little warmth and are often filled with smoke. Ventilation in homes is poor, leading to the spread of diseases in the cramped living conditions of the working classes.

Sanitation in 1895 is a growing concern, especially in the densely populated areas. Wealthier districts have access to modern sewer systems and regular waste collection, but in poorer areas, open sewers and filthy streets remain commonplace, contributing to the spread of cholera and other diseases. The idea of public health and hygiene is still in its infancy, and while some progress is being made, it is mostly the upper classes who benefit from these improvements.

Food in 1895 is diverse for those who can afford it. The rich enjoy the luxury of fresh fruit, vegetables, and imported goods, including exotic items like tropical fruits and spices. The working class relies on basic staples like bread, potatoes, and stew, often supplemented by cheap meat or fish. For the poor, food can be scarce, and malnutrition is a real problem.

Entertainment in 1895 is varied, depending on one's social class. The upper classes indulge in theatre, opera, and private events, while the working class may attend music halls, fairs, and public parks for some respite. Cinema is just emerging, with the first motion pictures being shown to eager audiences. Theaters are filled with both comedies and dramas, offering a much-needed escape from the daily grind. Newspapers also flourish, and gossip about the royal family, social scandals, and political developments fills the pages.

The atmosphere in Southampton, and indeed much of the world, is one of optimism mixed with a deep sense of Victorian morality. People are still hopeful for progress, though they are unaware of the social upheavals that the next century will bring. The air is thick with the smell of coal smoke, especially in industrial areas, and the streets are alive with the sounds of trams, horses, and the chatter of people as they go about their daily lives.

In terms of historical events, the year 1895 sees the beginning of significant changes. Alfred Dreyfus, a French officer, is wrongfully convicted of treason in a scandal that will become one of the most famous miscarriages of justice in history. In Britain, the suffragette movement is gathering strength, as women begin to push more forcefully for the right to vote. The arts are flourishing as well, with the publication of "The Yellow Book," a symbol of the decadent movement that challenges conventional morality.

The rich, working class, and poor continue to live in separate worlds, each shaped by its own struggles and joys. The poor and working class face hard times, with few opportunities for education or advancement, while the rich enjoy the privileges of wealth and leisure. The gulf between the two is vast, and many in the working class live in constant fear of illness or destitution, with little safety net to catch them when they fall.

In the grand sweep of history, 1895 is a year of transition, a time when the old ways of the Victorian era are still firmly in place, yet the winds of change are already beginning to blow. It is a year of uncertainty and opportunity, of hope and despair, where the future is at once exciting and unknown.

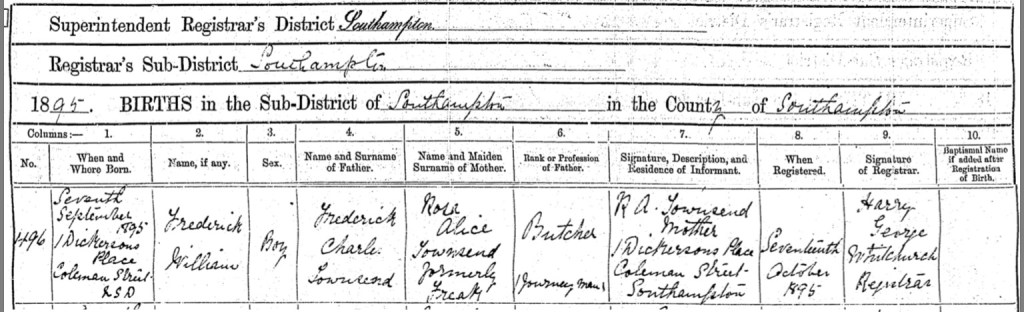

With the birth of her first child, Rosa Alice Townsend (née Freak) stepped into a new and profound chapter of her life, motherhood. On Saturday, the 7th day of September 1895, she cradled her newborn son, Frederick William Townsend, in her arms at their home at Number 1, Dickerson's Place, Coleman Street, Southampton. After a lifetime of loss, she now held hope in the form of her tiny, precious boy. Ten days later, with love and pride, she walked to the registrar’s office to officially record his birth, a moment that must have felt both surreal and deeply significant.

For Rosa, the arrival of Frederick William was more than just the birth of a child, it was the beginning of her own family, a chance to build something lasting and beautiful after so much heartbreak. He was the first of many children she would bring into the world, each one a testament to her resilience and strength. Life had not been easy for Rosa, and it would continue to test her, but for now, she was a mother holding her son, filled with the quiet promise of new beginnings.

I'm unable to locate specific historical information about Dickerson's Place on Coleman Street in Southampton, Hampshire, however Coleman Street is situated in the St Mary's district of Southampton, Hampshire, England. This area has a rich history, reflecting the broader development of Southampton over the centuries.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, the St Mary's district, where Coleman Street is located, underwent significant urban development. This period saw the construction of various residential and commercial buildings, contributing to the area's growth. Notably, the west side of St Mary Street, adjacent to Coleman Street, was home to Pope's Buildings, a 19th-century block situated between numbers 47 and 48. This block was directly opposite the modern location of Coleman Street.

Religious institutions also played a pivotal role in the community's development. An early Baptist meeting house, established in 1764, was located on the east side of St Mary Street, midway between Coleman Street and Cumberland Street. This chapel served as a significant place of worship for the local Baptist community during that era.

The area surrounding Coleman Street has been home to various notable residents. For instance, in 1912, a 17-year-old crew member of the RMS Titanic resided at number 9 St Mary's Place, a street running from Chapel Road behind St Mary's Church and the St Mary's Workhouse to Coleman Street. This connection highlights the area's ties to Southampton's maritime heritage.

In contemporary times, Coleman Street falls within the SO14 1GS postcode and is part of the Bargate ward in the Southampton Itchen parliamentary constituency. The area is predominantly urban, with a mix of housing types, including a higher-than-average level of social housing, accounting for approximately 67% of household spaces. The community is characterized by a significant number of single-person households, reflecting common trends in inner-city areas.

While specific historical records detailing the origins and developments of Coleman Street itself are limited, its location within the historically rich St Mary's district suggests that it has been part of Southampton's urban landscape for over a century. The street's proximity to significant historical sites and its inclusion in various records indicate its longstanding presence in the city's history.

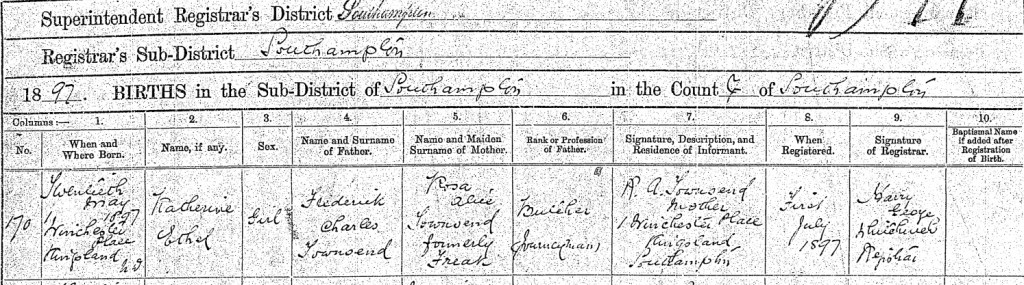

With the birth of her daughter, Katherine Ethel Townsend, on the 20th day of May 1897, Rosa Alice journey through motherhood deepened. At their home at Number 1, Winchester Place, Kingsland, Southampton, she once again experienced the indescribable joy of bringing a new life into the world. Nearly six weeks later, on the 1st day of July, she made her way to the registrar’s office to officially record Katherine’s birth, a moment that carried the same weight of love and responsibility as it had with her firstborn. Katherine’s arrival was another milestone in Rosa’s life, one that reminded her of the fragility and beauty of family. After enduring so much loss in her early years, each child she brought into the world was a gift, a symbol of hope, and a piece of her heart made tangible. With her husband, Frederick Charles Townsend, by her side, Rosa was building a family filled with love, a family that, despite the hardships of life, would endure.

Winchester Place, situated in the Kingsland area of Southampton, Hampshire, has a history that reflects the broader development of the city over the centuries. Kingsland, also known as St. Mary's, has been a significant part of Southampton's urban landscape since medieval times.

In the medieval period, the area now known as Kingsland was characterized by weekly markets and an annual fair, indicating its importance as a commercial hub. This tradition experienced a revival in the 1880s with the establishment of Kingsland Market on St. Mary Street, which became a popular shopping destination for locals.

The late 19th century saw further development in Kingsland, including the construction of notable buildings such as the Kingsland Baptist Church in 1884. This church served the local community until its demolition in 1978.

Winchester Place itself is part of this rich tapestry, contributing to the area's residential and commercial landscape, though specific historical records detailing the origins and developments of Winchester Place are limited unfortunately.

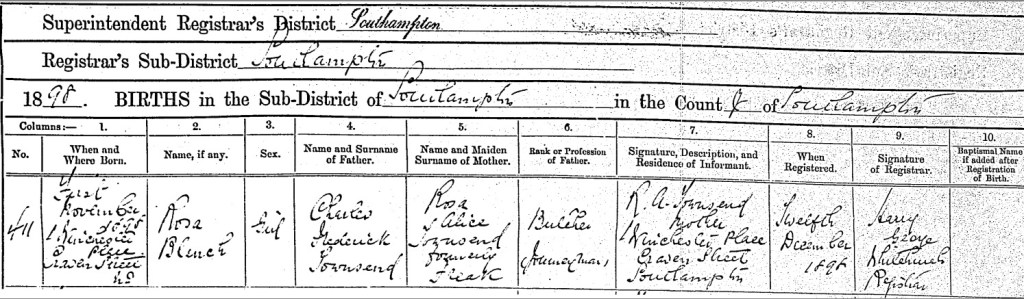

On the 1st day of November 1898, Rosa Alice Townsend welcomed her third child, a beautiful baby girl, she named Rosa Blanche Townsend. Born at their home at Number 1, Winchester Place, Craven Street, Southampton, Rosa Blanche was another precious addition to a family that was growing despite the hardships her mother had faced in life.

When Rosa Alice made the journey to the registrar’s office on Monday the 12th day of December, she once again carried with her the quiet pride of a mother, recording in ink what she already knew in her heart, her daughter was here, she was loved, and she was part of something bigger than herself.

Each birth was a new chapter, a promise that life carried on. After losing so many siblings in her youth, Rosa Alice understood, perhaps better than most, just how precious each moment with her children truly was. As she raised her young family with Frederick Charles Townsend, she was creating a future where love would be their foundation, a legacy that would live on through the generations to come.

Craven Street, located in the Kingsland area of Southampton, Hampshire, has a history that dates back to at least the early 19th century. By 1825, it extended from Cossack Street to St. Mary's Street, serving as a residential area for the local community.

In the 19th century, Craven Street was home to various residents, including Joseph Leach, a shoemaker, who lived there with his parents as recorded in the 1841 census.

Adjacent to Craven Street was Winchester Place, a court dating back to around 1820. Situated on the south side of Craven Street, slightly west of its midpoint, Winchester Place contributed to the dense residential fabric of the area.

By the late 1930s, Craven Street and its surrounding areas underwent significant changes. As part of a slum clearance initiative, the buildings along Craven Street were demolished to improve living conditions and modernize the urban landscape. This redevelopment led to the displacement of long-standing communities and the erasure of historical streetscapes.

In the 1960s, further urban development transformed the area where Craven Street once stood. The construction of modern housing and infrastructure replaced the old street layouts, altering the character of Kingsland. Today, little remains of the original Craven Street, but its legacy persists in historical records and the collective memory of Southampton's residents.

The evening of Tuesday the 7th day of November, 1899, changed Rosa Alice Townsend’s life forever. What began as an ordinary night turned into a nightmare that no mother should ever have to endure.

The Southampton Borough Fire Brigade arrived swiftly at Number 1, Winchester Place, Craven Street, finding the back room engulfed in flames. But Rosa was already inside, driven by a mother’s instinct stronger than fear, stronger than pain. She had braved the fire to save her children, Katherine Ethel and baby Rosa Blanche.

The fire had started when an oil lamp was accidentally upset and shattered. The flickering flame met the drying clothes hanging on an airer, igniting them in an instant. What had been a simple household routine turned into a deadly blaze within moments.

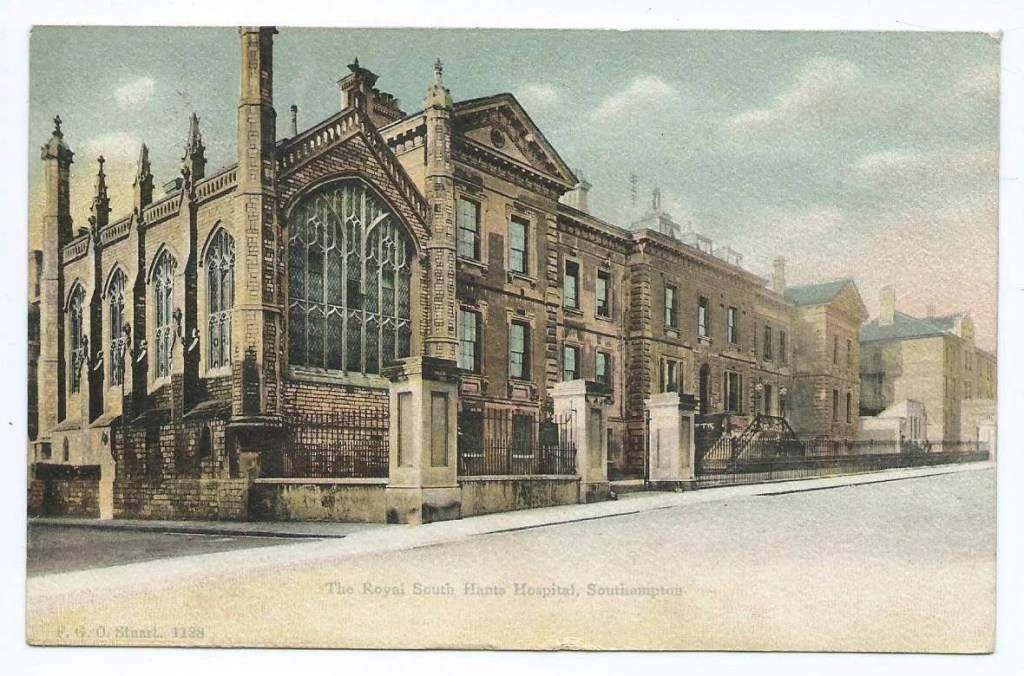

By the time the flames were extinguished, Rosa, Katherine, and little Rosa had suffered severe burns. Their injuries were grave, and they were rushed to the Royal South Hants Hospital Infirmary, their bodies bearing the terrible scars of that night.

My heart aches for them, for the unimaginable fear, the searing pain, and the helplessness they must have felt. Rosa had already known loss too intimately, burying her siblings, her father, and her baby brother and sisters. Now, fate had dealt another cruel blow.

How does one endure so much suffering and still find the strength to carry on? How does a mother, broken and burned, fight for her children when she, too, is barely holding on? This moment in Rosa’s life is one of unimaginable heartbreak, but also of profound love, a testament to the boundless courage of a mother willing to walk through fire for her children.

The walls of the Royal South Hants Infirmary must have echoed with the silent agony of a mother’s love as Rosa lay there, fighting for her own life, completely unaware that her precious Katherine had already slipped away. The fire had stolen so much from her, part of her home, her sense of safety, and now, her child. How cruel fate was to Rosa, to allow her heart to keep beating while keeping her in the dark about the most devastating loss of all.

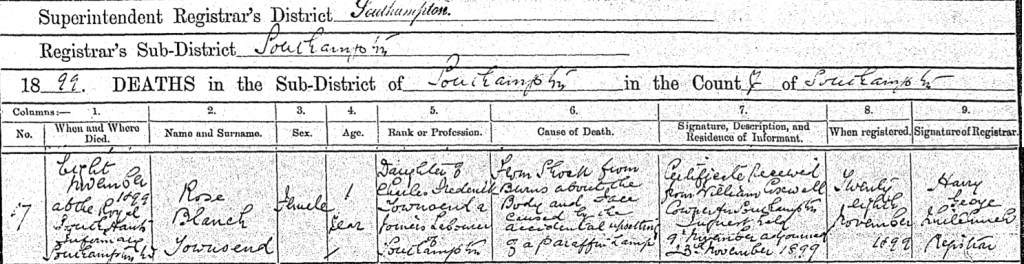

Little Katherine Ethel Townsend, just two years old, passed away on the evening of Tuesday, the 7th day of November, 1899, only hours after being admitted to the hospital. Her tiny body, too fragile to withstand the trauma, succumbed to the cruel burns that had ravaged her delicate skin. She had been cradled in her mother’s arms only moments before the flames consumed them, and now, she was gone.

On Tuesday, the 28th day of November, 1899, Registrar Harry George Whitchurch recorded Katherine’s death in the official register, a cold formality that could never capture the weight of the grief that surrounded it. He noted that she had died from shock caused by burns to her face and body, inflicted by the accidental upsetting of a paraffin lamp. A simple accident, yet one that had changed the course of Rosa’s life forever. William Coxwell, the coroner for Southampton, oversaw an inquest into Katherine’s death, first held on the 9th day of November and then adjourned until the 23rd day of November, as if examining the details could ever bring comfort to the shattered hearts left behind.

But perhaps the cruelest twist of all was that Rosa, too gravely ill from her own injuries, was kept in the dark. She lay in a hospital bed, unaware that her baby girl had already been taken from her. While she clung to life, hope may have flickered within her that her little Katherine was just a few rooms away, recovering, healing, surviving. No one could bring themselves to shatter what little strength she had left. The weight of that truth, of waking up to find her arms empty, her world forever changed, would come soon enough.

As if fate had not been cruel enough, another devastating blow struck Rosa and Frederick in the darkest hours of the night. In the early morning of Wednesday, the 8th day of November, 1899, their youngest daughter, one year old Rosa Blanche Townsend, took her final breath at The Royal South Hants Infirmary. Just hours after her sister Katherine’s passing, another innocent life was stolen by the flames that had ravaged their home. The weight of such loss is almost unbearable to comprehend, two daughters, lost within a single night. On Tuesday, the 28th day of November, 1899, the sorrowful task fell once again to Registrar Harry George Whitchurch to record yet another heartbreaking entry in the death register. He wrote that little Rosa Blanche, the daughter of Charles Frederick Townsend, a joiner’s labourer from Southampton, had died from shock due to burns on her body and face, caused by the accidental upsetting of a paraffin lamp. The coroner, William Coxwell, presided over an inquest into her death, held alongside her sister’s on the 9th day of November, before being adjourned to the 23rd day of November. A formality, an investigation, but no paperwork, no inquiry, no official record could undo what had been done. And still, Rosa remained in the hospital, too gravely ill to know the horrific truth. While she fought for her own life, no one dared to tell her that both of her daughters were gone. For all the sorrow Rosa had endured, the loss of her siblings, and her father, nothing could have ever prepared her for this. The weight of grief was beyond anything a mother should ever have to bear. The arms that had so often held her daughters close now lay empty, her world forever changed by a single, tragic night.

The Royal South Hants Hospital, also known as the Royal South Hants Infirmary, was an important institution in Southampton, Hampshire, England. Its history stretches back to the early 19th century, starting as a voluntary hospital intended to provide medical care to the poor and underserved people of the area. The hospital had its origins in 1827, when it was founded by a group of philanthropists who aimed to provide free healthcare to those who could not afford it. It was initially housed in a former mansion on High Street before moving to a purpose-built facility in St Mary’s, Southampton, in 1838.

The hospital quickly became a central part of the healthcare system in the region, providing a variety of medical services including surgery, maternity care, and treatment for infectious diseases. Throughout the 19th century, the Royal South Hants Hospital expanded its facilities, with new wings and departments added to meet the growing demand for healthcare. It was known for being one of the largest hospitals in the area, serving not only the local community but also the wider Hampshire region.

The Royal South Hants Hospital was particularly important during times of war. During the First World War, the hospital was overwhelmed with wounded soldiers and civilians, and its role in treating casualties was crucial to the war effort. The hospital continued to provide medical care during the Second World War as well, when it once again treated numerous soldiers and civilians injured in air raids and other wartime activities. Its reputation as a hospital that could handle difficult and serious medical cases grew throughout these periods.

In the 20th century, the hospital was modernized to meet the needs of contemporary medical practice. The introduction of new medical technologies, the expansion of surgical techniques, and the continued increase in patient numbers all contributed to the evolution of the hospital. By the mid-20th century, it was clear that a larger, more modern facility was needed to better serve the population of Southampton. This led to the decision in the 1960s to build a new hospital, and in 1977.

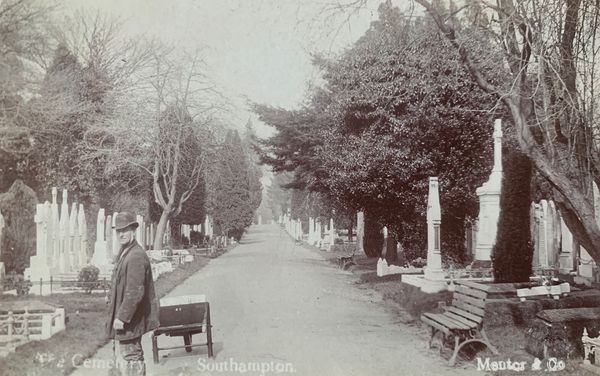

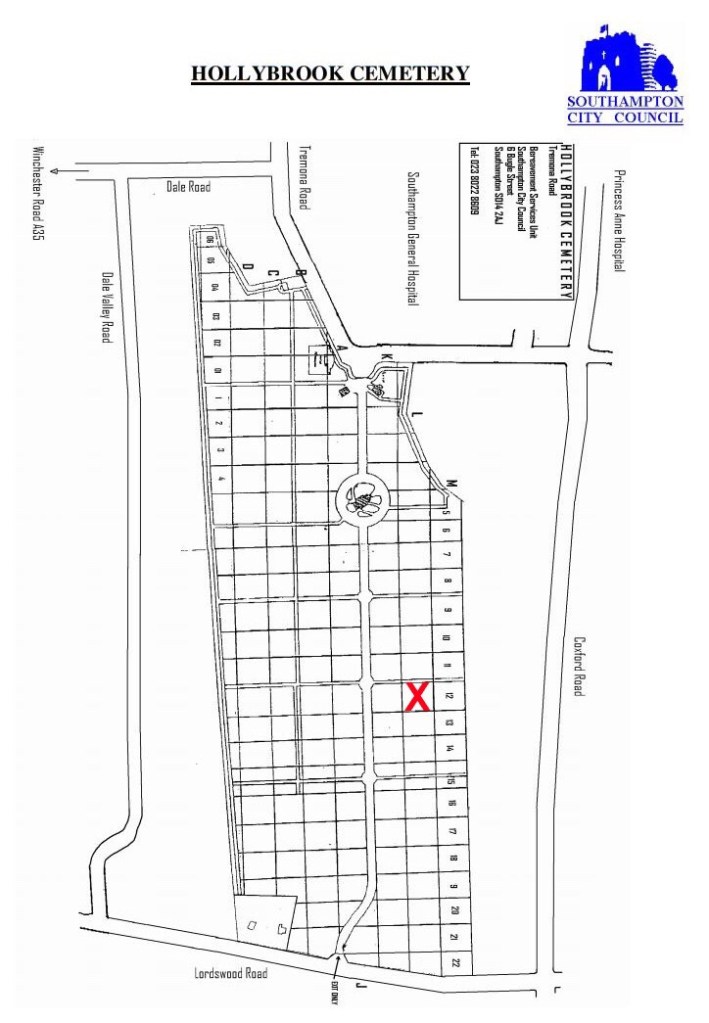

On a cold and sorrowful Saturday, the 11th day of November, 1899, Rosa and Frederick walked the unimaginable path no parent should ever have to take. With hearts shattered beyond repair, they laid their beloved daughters, Katherine Ethel and Rosa Blanche, to rest in Southampton Old Cemetery, their tiny bodies placed together in Row O, Block 143, Grave Number 212. The earth that cradled them became their final resting place, yet there was no headstone to mark their names, no inscription to tell the world of the love that had been lost.

The silence of their unmarked grave weighed heavily on my heart, two precious lives, so loved, yet with no stone to tell their story. But love does not fade with time, and kindness endures across generations. My dear friend Bruce, with the compassion and understanding that only true friendship brings, found their resting place for me. With reverence, he placed a cross upon their grave, a symbol of remembrance, a promise that they will never be forgotten. Though the years have passed, and the world has moved on, their memory remains, etched not in stone, but in the hearts of those who will always carry their names.

Southampton Old Cemetery, located on Hill Lane in Southampton, Hampshire, England, is a historic burial ground established in the mid-19th century. The cemetery's inception began on November 9, 1841, when the Southampton Town Council resolved to create a new burial ground on part of Southampton Common. An Act of Parliament in 1843 facilitated the acquisition of 15 acres from the common for this purpose. The initial design was proposed by John Claudius Loudon, a renowned landscaper and cemetery designer. However, his layout was not adopted; instead, a design by local nurseryman and councillor William Rogers was accepted. The cemetery officially opened on May 7, 1846, with the Bishop of Winchester consecrating a portion of the grounds. The first burial took place the following day, interring John Peake, a five-day-old infant. Initially encompassing 10 acres, the cemetery expanded by an additional 5 acres in 1863 and another 12 acres in 1884, bringing its total area to 27 acres. Over time, it has become the final resting place for over 116,800 individuals. The cemetery was designed to accommodate various religious denominations. A section was consecrated for the Church of England, while separate areas were designated for nonconformists, agnostics, and the Hebrew community. In 1856, the Roman Catholic community was also allocated a specific section within the grounds. Throughout its history, Southampton Old Cemetery has been the burial site for numerous notable individuals. Among them is Charles Rawden Maclean, also known as "John Ross," a friend of King Shaka and an opponent of slavery. He was buried in a pauper's grave in 1880, and in 2009, a headstone was erected to honor his memory. The cemetery also contains memorials related to significant historical events. Notably, there are 60 headstones associated with the RMS Titanic, reflecting Southampton's deep connection to the maritime tragedy. While no Titanic victims are buried here, these memorials serve as poignant reminders of the lives lost. Additionally, the cemetery includes a war graves plot with the graves of 21 Belgian servicemen, among other war memorials. Architecturally, the cemetery features several Grade II listed structures. These include the Church of England Mortuary Chapel, the Nonconformist Mortuary Chapel, the former Jewish Mortuary Chapel (now part of a house), and the Pearce Memorial, a sculpture by Richard Cockle Lucas. The cemetery's layout and landscaping reflect Victorian-era design principles, emphasizing a serene and contemplative environment. Today, Southampton Old Cemetery is not only a place of remembrance but also a site of ecological and historical interest. The Friends of Southampton Old Cemetery, a voluntary group, collaborates with the local council to manage the site's ecology, conduct guided tours, and assist in the maintenance of graves. Their efforts ensure that the cemetery remains a well-preserved testament to Southampton's rich heritage.

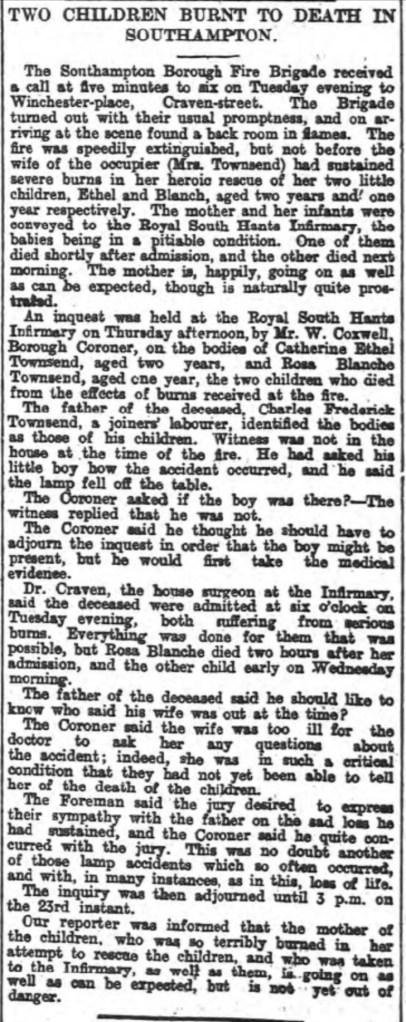

On the very day Rosa and Frederick Charles laid their beloved Katherine Ethel and Rosa Blanche to rest, their names appeared in the pages of The Hampshire Advertiser. The words printed on that cold Saturday, November 11, 1899, immortalized the horror of what had unfolded in their home. They spoke of Rosa’s heroism, her desperate attempt to save her daughters from the flames. They described the heartbreaking loss of two innocent children and the unbearable sorrow of a father who was not there when tragedy struck.

The inquest brought forth painful questions. Had the lamp simply fallen? The small details, the moments leading up to the fire, were lost in the chaos of that night. And Rosa, the only one who could truly recount what happened, was too ill to even know she was mourning.

Even in the face of official proceedings, amidst the cold language of reports and investigations, there was a flicker of humanity. The jury extended their sympathy to the grieving father. The coroner acknowledged yet another senseless accident, another family left shattered by the dangers of the oil lamps that lit so many homes. But no official words could lessen the pain, no condolences could fill the empty space where laughter and tiny footsteps once echoed.

Rosa had already known the cruel touch of loss. She had buried too many loved ones, endured more suffering than one soul should ever have to bear. But nothing, nothing, could have prepared her for this. The loss of Katherine Ethel and Rosa Blanche was not just another sorrow, it was a wound that would never truly heal. The article reads as follows,

TWO CHILDREN BURNT TO DEATH IN SOUTHAMPTON.

The Southampton Borough Fire Brigade received a call at five minutes to six on Tuesday evening to Winchester-place, Craven-street. The Brigade turned out with their usual promptness, and on arriving at the scene found a back room in flames. The fire was speedily extinguished, but not before the wife of the occupier (Mrs. Townsend) had sustained severe burns in her heroic rescue of her two little children, Ethel and Blanch, aged two years and one year respectively. The mother and her infants were conveyed to the Royal South Hants Infirmary, the babies being in a pitiable condition. One of them died shortly after admission, and the other died next morning. The mother is, happily, going on as well as can be expected, though is naturally quite prostrated.

An inquest was held at the Royal South Hants Infirmary on Thursday afternoonby Mr. W. Corwell, Borough Coroner, on the bodies, of Catherine Ethel Townsend, aged two years, and Rosa Blanche Townsend, aged one year, the two children who died from the effects of burns received at the fire.

The father of the deceased, Charles Frederick

Townsend, a joiners laboured, identited the bodies as those of his children.

Witness was not in the house at the time of the fire. He had asked his little boy how the accident occurred, and he said the lamp fell off the table.

The Coroner asked if the boy was there?-The witness replied that he was not.

The Coroner said he thought he should have to adjourn the inquest in order that the boy might be present, but he would first take the medical evidence.

Dr. Craven, the house surgeon at the Infirmary, said the deceased were admitted at six o'clock on Tuesday evening, both suffering from serious burns. Everything was done for them that was possible, but Rosa Blanche died two hours after her admission, and the other child early on Wednesday morning.

The father of the deceased said he should like to know who said his wife was out at the time?

The Coroner said the wife was too ill for the doctor to ask her any questions about the accident; indeed, she was in such a critical condition that they had not yet been able to tell her of the death of the children.

The Foreman said the jury desired to express their sympathy with the father on the sad loss he had sustained, and the Coroner said he quite concurred with the jury. This was no doubt another of those lamp accidents which so often occurred, and with, in many instances, as in this, loss of life.

The inquiry was then adjourned untl 3 p.m. on the 23rd instant.

Our reporter was informed that the mother of the children, who was so terribly burned in her attempt to rescue the children, and who was taken to the Infirmary, as well as them, is going on as well as can be expected, but is not yet out of danger.

It breaks my heart to think of Rosa, Frederick and their 5 year old son, Frederick William, still living within the same walls that had witnessed their greatest sorrow. By the time the 1901 census was completed on that cold March night, Sunday the 31st day of March 1901, their home at Number 1, Winchester Place, Craven Street, Kingsland, Southampton, Hampshire, remained unchanged, but the air within it must have been thick with grief. How could it not? Every shadow in that back room must have carried whispers of the past. Every creak of the floorboards must have echoed with the memory of their daughters’ laughter, now silenced forever.

How does one even begin to heal in a place so deeply stained with tragedy? Did Rosa still see the outlines of tiny hands reaching for her? Did she wake in the night, heart racing, hearing cries that were no longer there? The courage it must have taken to remain within those walls is something I can hardly fathom. Maybe there was no other choice. Maybe finances, circumstance, or even the weight of their grief itself kept them from leaving.

Frederick, now working as a joiner’s labourer, must have done his best to provide for his family, though I imagine the pay was modest. It was a skill that required patience and precision, one that has since faded with modernity, but back then, it was a means to survive. Even still, times must have been hard, because they had taken in a lodger, George Giles. Was he a friend? A stranger seeking shelter? Or simply a necessary burden to make ends meet?

Life had not been kind to Rosa and Frederick, and yet, they endured. They carried their pain within them, forced to continue on, even as the walls around them remained a silent, unbearable reminder of all they had lost.

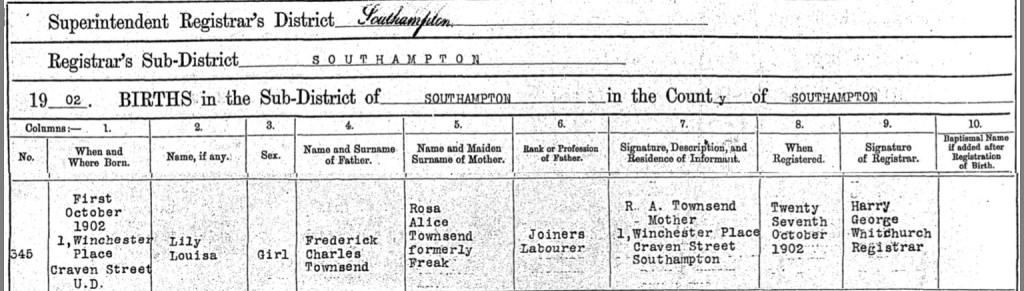

After so much heartache and unbearable loss, Rosa and Frederick finally had a reason to smile again. On a crisp autumn morning, Wednesday, the 1st day of October 1902, Rosa brought new life into the world, their third daughter, Lily Louisa Townsend. Born within the very walls that had seen so much sorrow, Lily’s arrival must have felt like a glimmer of hope piercing through the darkness that had loomed over their family for far too long.

I can only imagine the emotions Rosa must have felt as she cradled her newborn daughter. Did she weep with joy? With relief? With the bittersweet ache of knowing there were two little arms missing from this embrace? Grief and love often walk hand in hand, and for Rosa, this moment was likely filled with both.

On Monday, the 27th day of October, Rosa made the journey into Southampton to register Lily’s birth, a quiet but significant act of resilience. The familiar name of the registrar, Harry George Whitchurch, must have been a stark reminder of past heartbreak, yet this time, she was there for a happier reason. In the register, Lily was recorded as the daughter of Frederick Charles Townsend, a Joiner’s Labourer, and Rosa Alice Townsend, formerly Freak, of Number 1, Winchester Place, Craven Street.

Though their home still held memories of loss, Lily’s tiny cries filled it with something new, hope, renewal, and a future that Rosa and Frederick had once feared might never come.

On a cold winter Sunday, the 28th day of January 1906, Rosa gave birth to her son, Jesse Edward Townsend, my maternal great-grandfather. This time, the walls that welcomed a new life were different. The family had moved to Number 197, Radcliffe Road, Southampton, leaving behind the sorrow, soaked home on Winchester Place. Though grief never truly fades, perhaps this new beginning, in a new home, allowed Rosa and Frederick to breathe a little easier, to feel a little lighter, and to believe that joy could once again find them.

On Tuesday, the 6th day of March 1906, Rosa made her way into town to register Jesse’s birth. The registrar, Alfred Thomas Bust, recorded the details, inscribing into history the arrival of Jesse Edward Townsend, the son of Frederick Charles Townsend, a Joiner’s Labourer, and Rosa Alice Townsend, formerly Freak. As always, Frederick’s name was recorded as he preferred it, Frederick Charles, rather than his birth name, Charles Frederick Joseph Townsend.

Jesse’s birth was not just the arrival of another child, it was the continuation of Rosa and Frederick’s story, proof that even after unimaginable loss, life pushes forward. With each tiny breath, Jesse carried with him the strength of his mother, the endurance of his father, and the love of the siblings he would never meet. He was a new hope, a new beginning, and the living heartbeat of a family that had already endured so much.

Radcliffe Road, located in the Northam area of Southampton, Hampshire, has a history that reflects the city's evolving urban landscape. Originally known as York Road, it was renamed in 1884 in honor of E. B. Radcliffe, the solicitor for the Chamberlayne Estate.

In the early 2000s, the area encompassing Radcliffe Road underwent significant redevelopment. The former North Allotment Gardens, situated along Radcliffe Road, were investigated for soil contamination as part of a remediation strategy in 2005, indicating plans for new residential developments.

A notable landmark on Radcliffe Road is the Vedic Society Hindu Temple. Established in 1971 by a group of dedicated Hindus aiming to preserve Sanatana Dharma, the temple began with humble gatherings in homes and later in a Northam church hall. On August 11, 1984, the Vedic Society Hindu Temple was inaugurated, becoming the only purpose-built Hindu temple in the South of England. The temple is located at 79-195 Radcliffe Road and serves as a cultural and spiritual center for the Hindu community in Southampton.

Over the years, Radcliffe Road has experienced fluctuations in property values. As of recent data, the average house price on Radcliffe Road is approximately £233,393, reflecting a slight decrease from previous years. The dominant property type in the area is modern flats built after 1980, indicating ongoing development and modernization.

Today, Radcliffe Road continues to be a significant part of Southampton's Northam district, blending historical roots with contemporary developments.

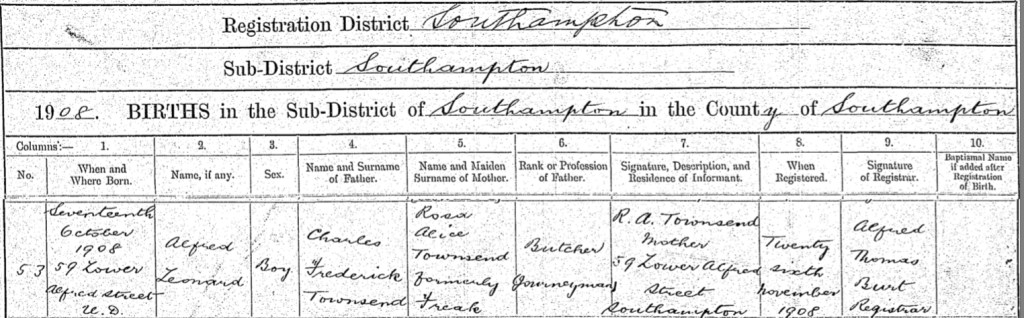

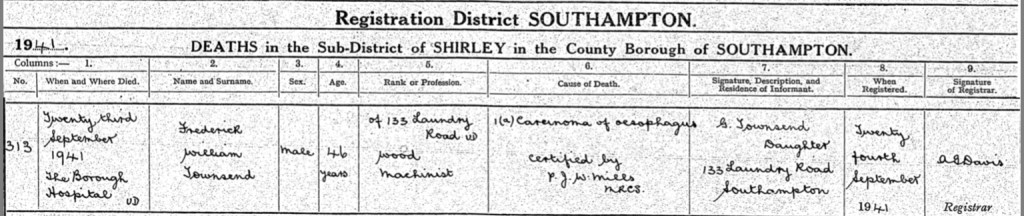

On Saturday, the 17th day of October 1908, Rosa welcomed her sixth child, Alfred Leonard Townsend, into the world. Their home had changed once again, this time, to 59 Lower Alfred Street in Southampton. A new home, a new child, another chapter in Rosa’s extraordinary life.

On Thursday, the 26th day of November 1908, Rosa made the familiar journey to the Southampton register office, cradling the weight of both past sorrow and present joy in her heart. There, Alfred Thomas Bust recorded the birth of her son, Alfred Leonard Townsend, the child of Charles Frederick Townsend, a Butcher Journeyman, and Rosa Alice Townsend, formerly Freak.

With every child she brought into the world, Rosa carried the ghosts of those she had lost, but she also carried hope. Alfred’s birth was another reminder that love endures, that life persists, and that even after the darkest of days, there is still light.

Lower Alfred Street, located in Southampton, Hampshire, has a history intertwined with the city's development, particularly in the 19th and 20th centuries. The street is situated near the Royal South Hants Hospital, a notable landmark in the area.

During World War II, Southampton endured significant bombing raids, and Alfred Street was among the affected areas. In the early hours of one such raid, bombs fell near the Royal South Hants Hospital, resulting in the destruction of ten houses on Alfred Street. The hospital itself sustained damage, with windows shattered due to the blasts.

Post-war redevelopment led to changes in the architectural landscape of Alfred Street and its vicinity. Some historical buildings were demolished to make way for modern structures, reflecting the city's efforts to rebuild and modernize after the war's devastation.

Today, Alfred Street is part of the SO14 postal district. The area has seen various property transactions over the years, indicative of its evolving residential character.

For those interested in visual history, photographs of Alfred Street, including images of war-damaged properties from the 1940s, are preserved in local archives. These photographs provide a glimpse into the street's past and the resilience of its community during challenging times.

Lower Alfred Street's history reflects Southampton's broader narrative of growth, adversity, and regeneration, embodying the city's enduring spirit.

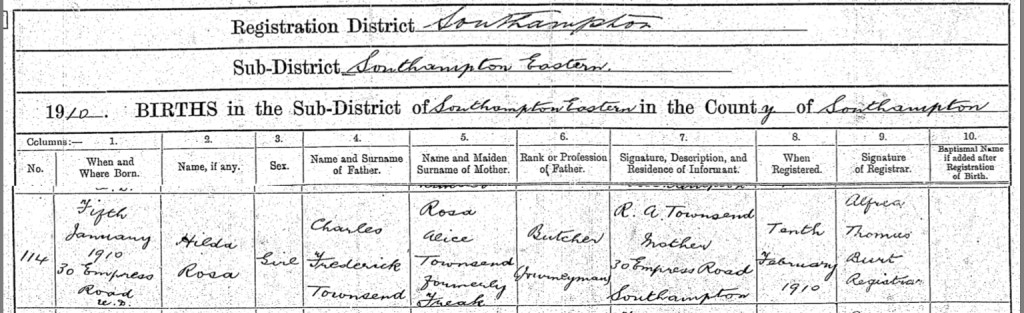

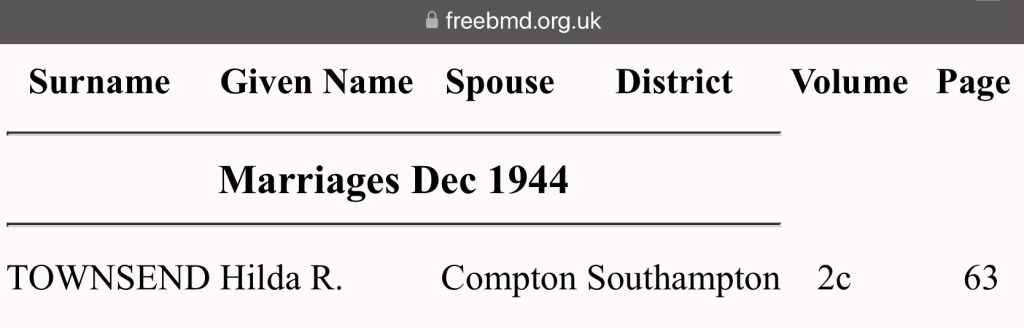

On a winter’s day, Wednesday, the 5th day of January 1910, Rosa gave birth to her seventh child, a beautiful daughter whom she and Frederick named Hilda Rosa Townsend. Their home had changed once again, now settled at Number 30, Empress Road, Southampton. With each move, Rosa carried with her the weight of all she had endured, but also the love that continued to grow within her family.

On the 10th day of February 1910, Rosa once more made the journey to the Southampton register office, just as she had done for each of her children before. There, Alfred Thomas Bust recorded the birth of Hilda Rosa Townsend, daughter of Charles Frederick Townsend, a Butcher Journeyman, and Rosa Alice Townsend, formerly Freak.

Though life had been cruel to Rosa in so many ways, here was another moment of joy, a daughter, carrying both her mother’s and late sister’s name, a symbol of resilience, love, and remembrance.

Empress Road, situated in Southampton, Hampshire, has undergone significant transformations since its inception around 1900. Initially a residential street lined with terraced houses overlooking the railway line and the river, it reflected the architectural style of that era.

Over time, the residential character of Empress Road diminished as industrial development took precedence. The original houses were demolished to make way for factories and warehouses, marking a shift in the area's function and landscape.

One notable establishment was the Associated Biscuits depot, which opened in the latter half of the 1930s. This Art Deco-style building, however, had a short lifespan, as it was destroyed during the bombing raids of the early 1940s.

In recent years, Empress Road has continued to serve as an industrial hub, housing various businesses and warehouses. The area has also been the subject of archaeological interest; investigations at the Acorn Business Centre, located at 1-16 Empress Road, revealed significant prehistoric deposits, including Mesolithic peat layers, providing insights into the ancient environmental conditions of the Itchen valley.

Today, Empress Road stands as a testament to Southampton's adaptive landscape, transitioning from residential beginnings to a center for industrial and commercial activity.

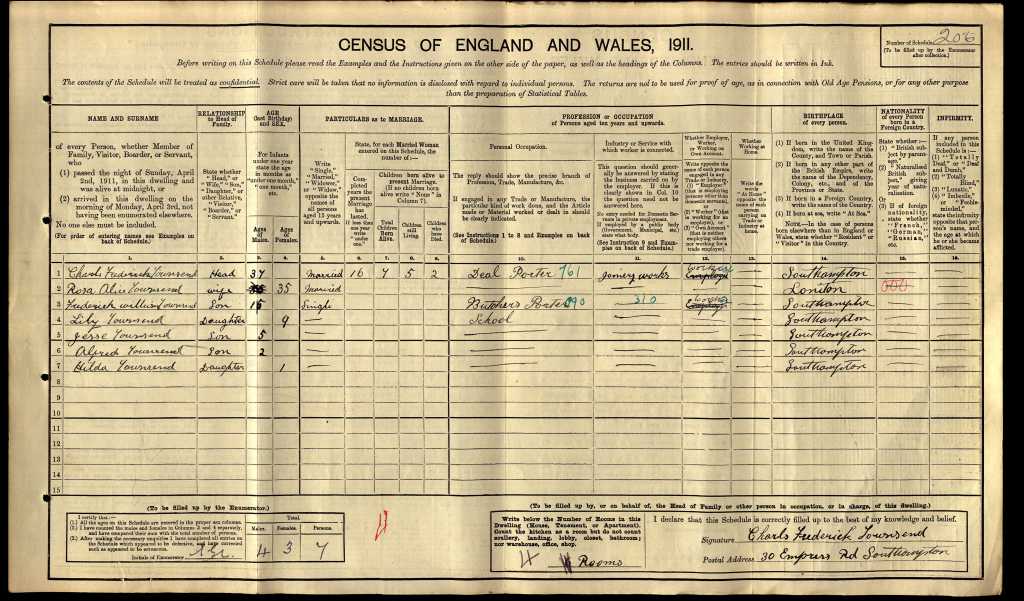

On the night of Sunday, the 2nd day of April, 1911, as darkness settled over Southampton, Rosa Alice Townsend sat within the walls of their home at Number 30, Empress Road, Southampton. It was a four-room dwelling, not grand by any means, but it was a place where love and resilience held her family together. It was here, in this home, that she had nursed her babies, soothed their cries, and tucked them into bed with a mother’s gentle touch. It was also here that she carried the weight of unspeakable grief, an ache that never truly faded.

At 35 years old, Rosa had been a wife for 16 years. She and her husband, Charles Frederick Townsend, had built a life together, one that had been marked not only by hardships but also by moments of quiet joy. Charles aka Frederick, now 37, was working as a Deal Porter at a Joinery Works, his strong hands no stranger to hard labor. Their eldest child, 15 year old Frederick William, was already contributing to the household as a Butcher’s Porter, stepping into the world of work just as his father once had. Nine year old Lily was at school, a young girl growing up in the shadow of both love and loss. Five year old Jesse, two year old Alfred, and baby Hilda, only one year old, were still too little to understand the struggles their parents had endured, too young to remember the sisters they would never meet.

As Rosa watched her children, she knew that every single one of them was a gift, a reason to keep going despite the hardships life had thrown her way. She had given birth to seven children, but only five still lived. The absence of Katherine and Rosa Blanche was a silent wound, one she carried with her every single day. There was no need to speak of it for the pain to be felt. It was there in the quiet moments, in the way she must have lingered just a little longer when tucking her children in at night, in the way she held them just a bit tighter when they called for her.

What made the 1911 Census so profoundly different from those before it was that, for the first time, it was written by the very people it documented. It was Charles Frederick’s hand that carefully wrote their details, listing the names of his wife and children, the home they lived in, the work they did to survive. And beneath it all, a heartbreaking reality recorded in ink, seven children born, but only five still alive. With each stroke of the pen, he was forced to acknowledge the loss that had shaped their family.

That census return, now a simple document in the eyes of history, was far more than just a record of a household. It was a testament to survival, a reflection of a mother’s strength, a father’s perseverance, and a family that, despite all they had endured, carried on.

Just a few months after Rosa and Charles Frederick completed the 1911 Census, life in their home at 30 Empress Road changed once again. On Friday, the 21st day of July, 1911, Rosa brought another child into the world, a baby boy, their eighth child. They named him Henry Charles Townsend.

The walls of their modest four-room home had seen so much over the years, love, sorrow, and resilience. Now, they welcomed the cries of a newborn once more, a sound that must have brought both immense joy and a bittersweet ache to Rosa’s heart. She had buried two babies, and yet here she was, cradling another precious life, a new little soul to love, to protect, to cherish.

As she had done many times before, Rosa made the journey to the registry office in Southampton, this time to officially record Henry’s birth. On Monday, the 28th day of August, 1911, she stood before Annie Stewart, the deputy registrar, and provided the details of her son’s arrival. Once again, her husband was listed as Frederick Charles Townsend, a Joiner’s Labourer. Though his birth name was Charles Frederick Joseph, he continued to live by the name that felt most like his own.

With Henry’s birth, their home became even fuller, and so did Rosa’s heart. She had known unbearable pain, but she had also known the profound beauty of motherhood. Henry was another chance to watch a child grow, to witness the first smile, the first steps, the first words. Another reason to keep moving forward, no matter how heavy the past still weighed upon her.

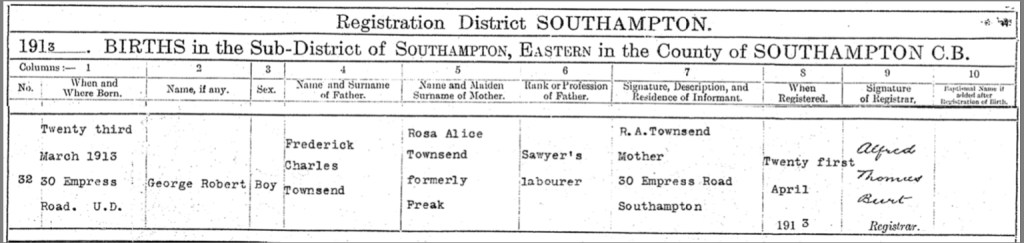

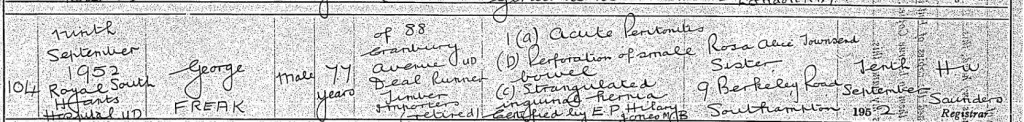

As the chill of winter gave way to the first warmth of spring, Rosa once again found herself cradling a newborn in her arms. On Sunday, the 23rd day of March, 1913, she gave birth to her ninth child, a baby boy named George Robert Townsend. He was born at home, in the same four walls that had witnessed so much of Rosa’s life, the laughter of children, the cries of newborns, and the echoes of unimaginable sorrow.

Despite the exhaustion of childbirth and the never-ending demands of motherhood, Rosa made the familiar journey into Southampton, as she had done so many times before, to officially record her son’s birth. On that day, Annie Stewart, the deputy registrar, entered George Robert Townsend’s name into the birth registry. He was the son of Frederick Charles Townsend, now listed as a Sawyer’s Labourer, and Rosa Alice Townsend, formerly Freak, both of 30 Empress Road. As always, Rosa’s husband was recorded under the name he had chosen for himself, Frederick Charles, rather than the name given to him at birth, Charles Frederick Joseph.

With George’s arrival, Rosa’s household grew even fuller, and so did her heart. Each new life she brought into the world was a testament to her resilience, to her determination to keep going despite the many hardships she had endured. George, like each of her children before him, was a piece of her, a light in her world, a reason to keep moving forward.

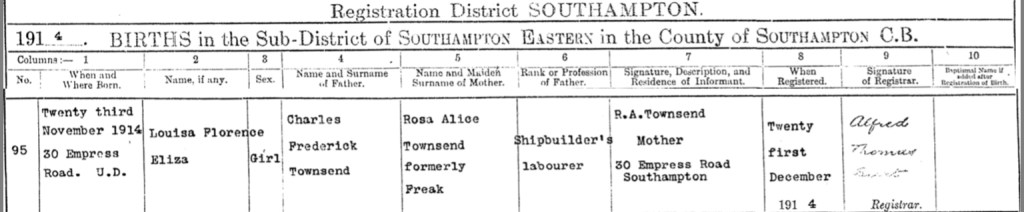

As the golden leaves of autumn gave way to the chill of winter, Rosa once again found herself bringing new life into the world. On Monday, the 23rd day of November, 1914, she gave birth to her tenth child, a precious daughter whom they named Louisa Florence Eliza Townsend. Born at home in the ever-familiar walls of 30 Empress Road, Southampton, Louisa’s arrival marked another chapter in Rosa’s life, a life filled with both joy and heartbreak, but always defined by love and resilience.

With Christmas fast approaching, Rosa made her way into Southampton once more, retracing the same path she had walked so many times before, to register her daughter’s birth. On Monday, the 21st day of December, 1914, Alfred Thomas Bust, the registrar, recorded in the official birth register that Louisa Florence Eliza Townsend, a girl, had been born on 23rd November at 30 Empress Road. As always, Rosa’s husband was listed as Charles Frederick Townsend, a Sawyer's Labourer, though she knew him best as Frederick, a name he had chosen for himself rather than the one given to him at birth.

Little Louisa's birth was a glimmer of light in the shadow of a world at war. The year 1914 had brought with it the outbreak of the Great War, a conflict that would change the course of history and touch the lives of so many. Yet, within the Townsend household, amidst the worry and uncertainty of the world beyond their doorstep, there was still the warmth of a newborn baby, the quiet miracle of life continuing on.

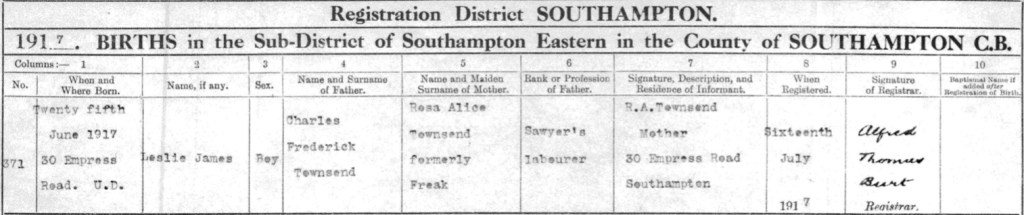

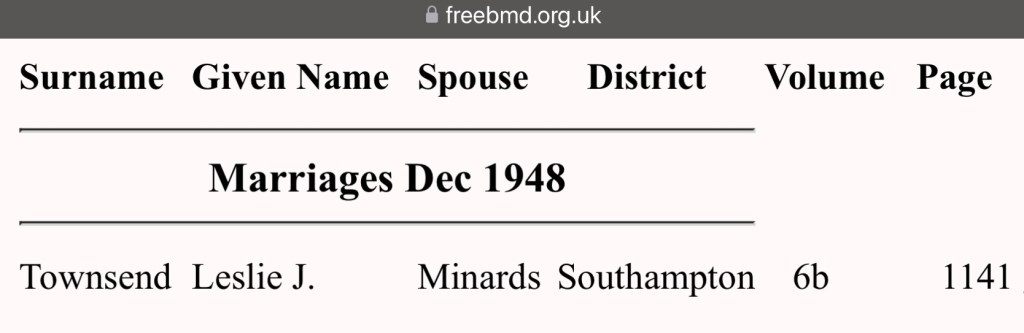

As the warmth of summer embraced Southampton in 1917, Rosa once again found herself cradling new life in her arms. On Monday, the 25th day of June, she gave birth to her eleventh child, a baby boy named Leslie James Townsend. Their home at 30 Empress Road had now witnessed the arrival of yet another little soul, a sixth son for Rosa and Charles, whom she still lovingly knew as Frederick.

Despite having walked this path so many times before, Rosa once again made the now familiar journey into the heart of Southampton to register her son’s birth. On Monday, the 16th day of July, 1917, Alfred Thomas Bust, the registrar, recorded in the official birth register that Leslie James Townsend, a boy, had been born on 25th of June at 30 Empress Road. His father was listed, as Charles Frederick Townsend, a Sawyer's Labourer, and his mother as Rosa Alice Townsend, formerly Freak.

With each child she bore, Rosa’s heart must have swelled with both love and apprehension. The world was now at war, and though the echoes of distant battles may not have reached their doorstep, the weight of uncertainty loomed over every home, every family, every mother who held her child close and wondered what kind of future lay ahead. But in that moment, as she held little Leslie against her chest, he was safe, he was loved, and he was hers.

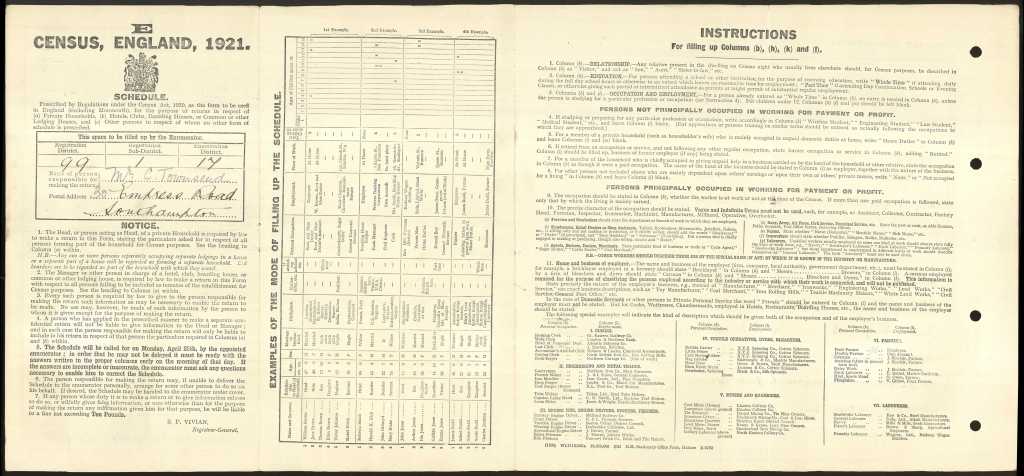

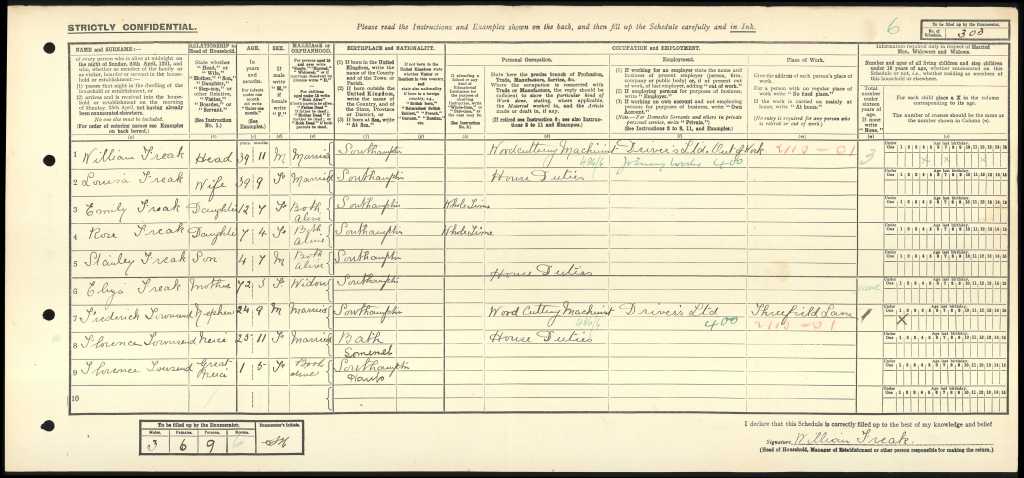

On Sunday, the 19th day of June, 1921, at their home Number 30 Empress Road, Southampton, Rosa and Frederick once again found themselves completing the census, another record of their ever-growing family's journey through life. It was Frederick’s hand that filled in the form, carefully documenting the details of their household. Rosa, his beloved wife, was now 44 years and 8 months old, while he himself was 45 years and 4 months. Their children still at home spanned a wide range of ages, from young adults to little ones still learning their way in the world.

Their eldest daughter, Lily Louisa, was now 19 years and 9 months old and had entered the working world, earning a living as a Poulterer for Moats, a company on London Road in Southampton. Jesse Edward, at 15 years and 5 months, was also already contributing to the household, working as an Errand Boy for Browns Butchers in Portswood. Meanwhile, their younger children, Alfred, aged 12, Hilda Rosa, 11 years and 5 months, Henry Charles, aged 10, George Robert, 8 years and 3 months, Florence Louisa, 6 years and 7 months, and little Leslie James, just 4 years old, were still immersed in the innocence of childhood, with all but Leslie attending school full-time.

Frederick himself was employed as a Timberman for Harlang Swaolff Ship Repairs at Southampton Docks, a physically demanding job that must have required great strength and endurance. Life had not been easy for Rosa and Frederick, but despite all the heartbreak they had endured, their home remained filled with love, laughter, and the relentless spirit of a family determined to keep moving forward.

Their eldest son, Frederick William Townsend, was not living at home when the 1921 census was taken. Instead, he was residing with his uncle, William Freak, at Number 102, Northumberland Road, Southampton. William, now 39 years and 11 months old, lived there with his wife, Louisa Freak, who was 39 years and 9 months, and their three children, Emily Freak, aged 12 years and 7 months, Rose Freak, aged 7 years and 4 months, and Stanley Freak, aged 4 years and 7 months. Also in the household was Frederick William’s grandmother, Eliza Freak (formerly Stockwell), now 72 years and 3 months old.

Alongside them was another familiar name, Florence Townsend, a woman of 25 years and 11 months, and her young daughter, also named Florence Townsend, just 1 year and 5 months old. The connection between Florence and Frederick William remains a small mystery in the census records, but their presence in the same household suggests a close familial bond.

Frederick William, now a young man making his own way in the world, was working as a Woodcutting Machinist for Drivers Ltd in Threefield Lane, Southampton. While he may have been living away from home, he was still surrounded by family, a support system that no doubt helped him navigate the challenges of early adulthood.

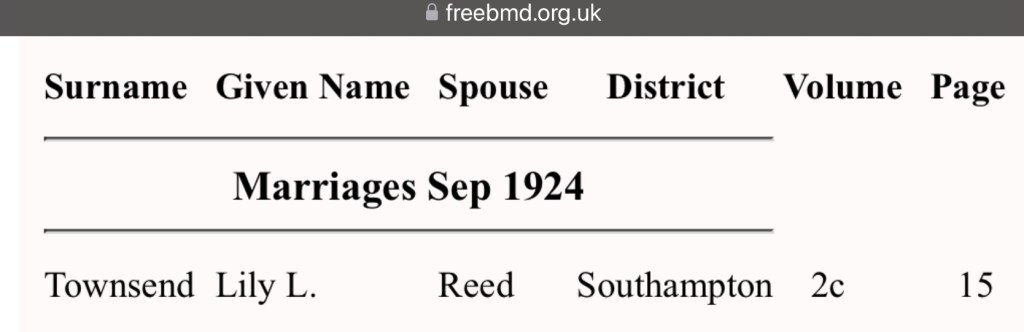

Rosa and Frederick’s daughter, Lily Louisa Townsend, found love and companionship when she married James Reed in the September quarter of 1924 in the district of Southampton, Hampshire, England. It must have been a bittersweet moment for Rosa, watching her daughter begin a new chapter in her life, knowing how much joy and sorrow their family had endured over the years.

Unfortunately, due to the sheer number of birth, death, and marriage certificates I have obtained while piecing together Rosa’s story, I have had to make the difficult decision to forgo purchasing the marriage certificates. I deeply regret not being able to provide every detail of Lily and James’s union, but for those who wish to uncover more about their special day, you can order the certificate using the following GRO reference:

“GRO Ref - Marriages, September 1924, Reed, James, Townsend, Lily L, Southampton, Volume 2c, Page 15.”

Though the specifics of their wedding remain unknown, I like to imagine that after all the heartache and hardships, this day brought Rosa a moment of happiness, a chance to see her daughter step into a hopeful future.

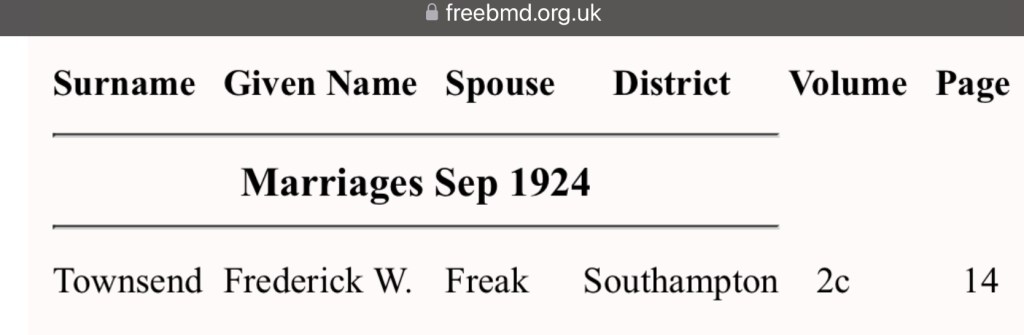

Rosa and Frederick’s son, Frederick William Townsend, married Alice Rosa Jane Freak in the September quarter of 1924 in the Southampton district of Hampshire, England. This union held a deeper family connection, as Alice was the daughter of Charles William Freak, Rosa’s own brother, making her not only Frederick’s bride but also his cousin.

It is fascinating to see how families intertwined during this time, with close-knit communities and shared histories binding them together. Though I do not have the full details of their wedding, those who wish to order their marriage certificate can do so using the following GRO reference:

“GRO Ref - Marriages, September 1924, Townsend, Frederick W, Freak, Alice R A, Southampton, Volume 2c, Page 14.”

One can only wonder how Rosa felt, knowing that her son was marrying her brother’s daughter. Perhaps it brought her comfort to see her family remaining close, or maybe it was simply another reminder of how deeply their lives were interwoven through both love and loss.

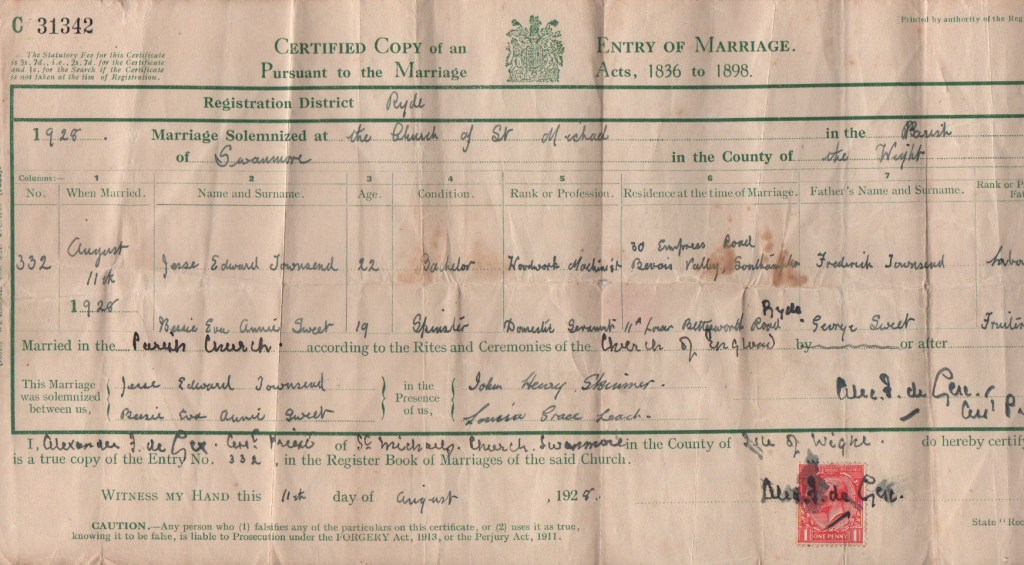

On a crisp autumn day, Friday the 19th day of October 1928, Rosa’s and Frederick’s son, Jesse Edward Townsend stood at the altar of St. Michael’s Church in Swanmore, Isle of Wight, ready to begin a new chapter of his life. At 22 years old, he was a hardworking woodwork machinist, still living at his family home, Number 30, Empress Road, Southampton. Across from him stood his bride, 19-year-old Bessie Eva Annie Sweet, a domestic servant from Number 11, Lower Bettesworth Road, Ryde, Isle of Wight. She was the daughter of George Frederick Sweet, a fruiterer, and Elizabeth Grace Gibbs Porter (My 2nd Great-Grandparents).

The church was likely filled with the quiet murmurs of family and friends, gathered to witness the union of two young souls. Though the minister’s name is difficult to decipher from the records, he solemnized their vows, recording the details in the marriage register.

Jesse’s father, Frederick Townsend, was listed simply as a labourer, a title that hardly captured the resilience and hard work he had put into providing for his large family. Bessie’s father, George Sweet, a fruiterer by trade, had likely provided for his own family with equal dedication.

Among those standing in support of the couple were John Henry Skinner, possibly a relation of Bessie’s sister-in-law, Eliza Mary Skinner, and Bessie’s own sister, Louisa Grace Leach (née Sweet), who bore witness to the beginning of this new journey.

One can only imagine Rosa’s emotions on that day, pride, nostalgia, perhaps a bittersweet sense of time slipping by. Her little boy, whom she had carried through so much hardship, was now a man with a family of his own to build.

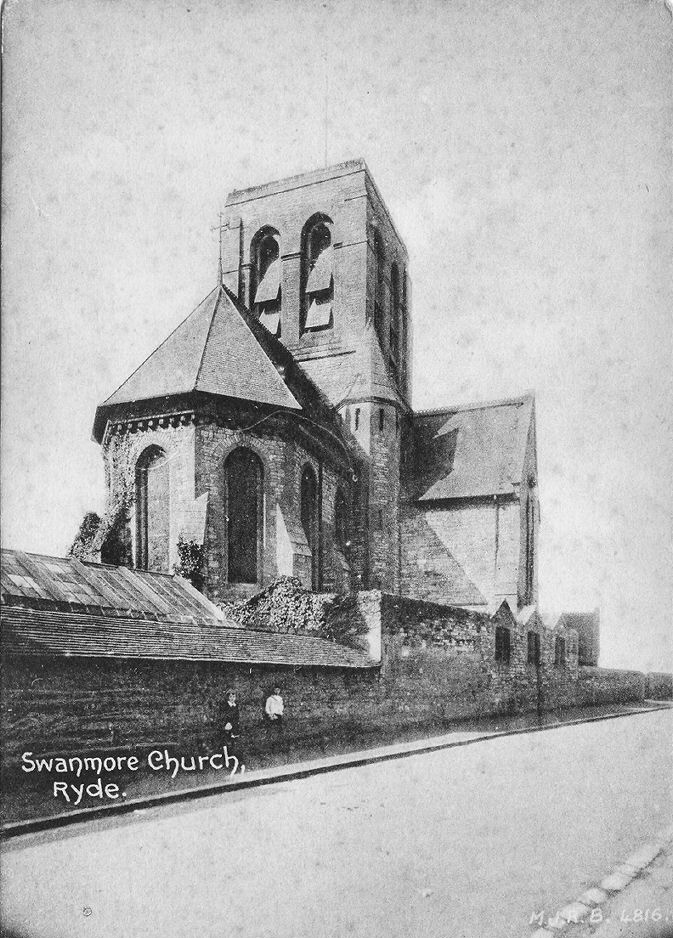

St. Michael and All Angels Church is located in the Swanmore area of Ryde on the Isle of Wight. Constructed between 1857 and 1862, it was designed by architect R.J. Jones in the French Gothic style. The church was consecrated by the Bishop of Winchester in 1863.

The church features a cruciform layout with a central square tower rising nearly 90 feet high, housing three bells on the second level. This tower offers panoramic views across the Solent.

Before the construction of the permanent structure, the local congregation used an iron church, which was later relocated to Wroxall to serve as both a church and a school.

Despite its historical significance, St. Michael and All Angels Church was closed in December 2018, following a campaign to keep it open.

Adjacent to the church stands the vicarage, a Grade II listed building recognized by Historic England for its architectural and historical importance.

The church's history reflects the development of the Swanmore community and its enduring architectural heritage.

In the late summer of 1930, Rosa and Frederick’s son, Henry Charles Townsend, took a significant step into married life. He wed Sylvia D. M. Derham in the Southampton district of Hampshire, England. Though details of their wedding day remain undocumented, one can imagine the scene, a gathering of family and friends, a mixture of joy and nostalgia as another of Rosa’s children set off to build a life of his own.

By this time, Rosa had witnessed many of her children marry and start families, and though money had often been tight, love and resilience had always been in abundance. If you wish to obtain an official record of Henry and Sylvia’s marriage, you can do so using the following GRO reference:

“Marriages, September 1930,Townsend, Henry C, Derham, Sylvia D. M, Southampton, Volume 2c, Page 185.”

It’s another chapter in Rosa’s ever-growing family story, a testament to the strength and perseverance that carried them through so many hardships.

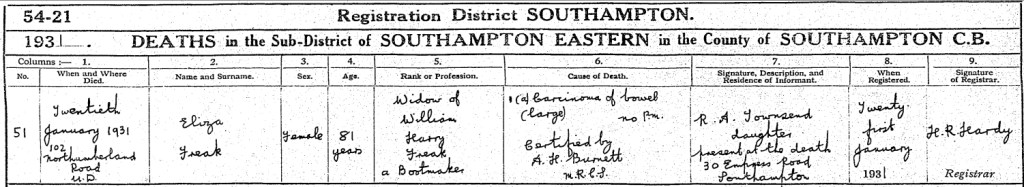

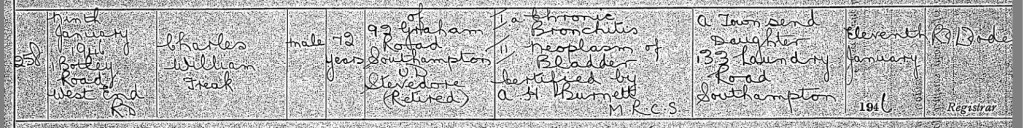

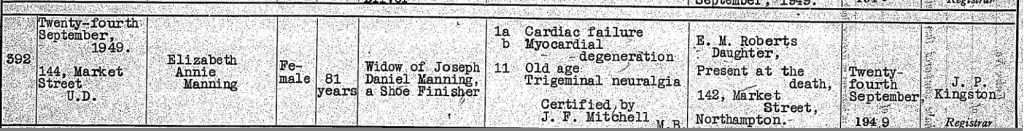

Rosa’s beloved mother, Eliza Freak née Stockwell, took her final breath on a cold winter’s day, Tuesday, the 20th of January 1931, at the home she had known for so many years, Number 102, Northumberland Road, Southampton. She was 81 years old, and despite the sorrow of losing her, there was some solace in knowing that she was not alone in her final moments. Her devoted daughter, Rosa Alice, was by her side, offering the comfort only a daughter could give as she slipped away.

The very next day, with a heavy heart, Rosa made the journey to register her mother’s passing. On Wednesday, the 21st of January 1931, she stood before the registrar, H. R. Hardy, and provided the details of her mother’s life, one last time. It was recorded in the official death register that Eliza Freak was the widow of William Harry Freak, a Bootmaker, and that she had succumbed to Carcinoma of the bowel (Large). Dr. A. H. Burnett, M.R.C.S., had certified her passing, and no postmortem was deemed necessary.

Eliza had lived through times of immense hardship, witnessing the changing world around her, the births of her grandchildren, and the losses that came with the passage of time. She had been a mother, a wife, and a guiding presence in Rosa’s life. Now, Rosa had to say goodbye, carrying forward her mother’s memory, her strength, and her unwavering love.

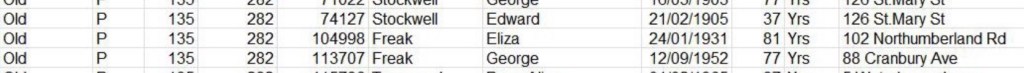

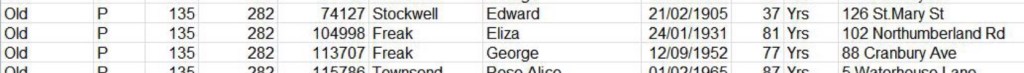

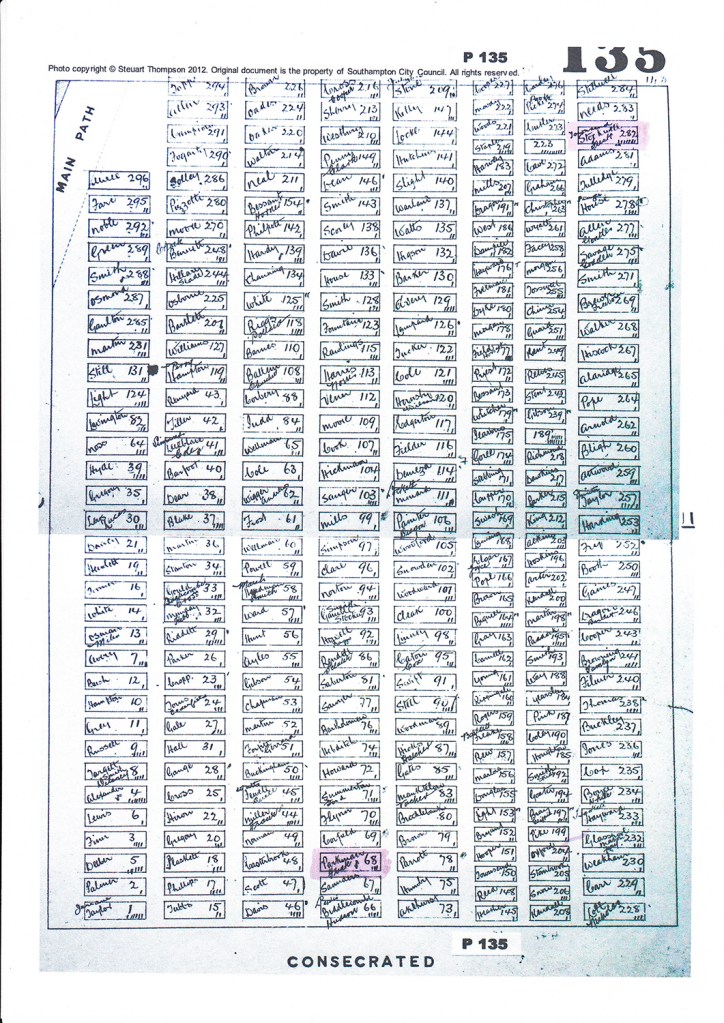

On a cold winter’s day, Saturday the 24th day of January 1931, Rosa, her siblings, family, friends, and acquaintances gathered in the quiet grounds of Southampton Old Cemetery, Hill Lane, Southampton, Hampshire, England, to say their final goodbyes to Rosa’s beloved mother, Eliza Freak née Stockwell. The air was heavy with grief as they stood together, mourning the loss of a woman who had been a mother, a grandmother, a sister, and a friend.

Eliza was laid to rest in Row P, Block 135, Number 282, her burial recorded as interment number 104998. Though sorrow filled the hearts of those who stood around her grave, there was also comfort in knowing that she was not alone in her resting place. She was reunited in eternal slumber with her parents, Elizabeth Stockwell née Wren (1831–1900) and George Stockwell (1831–1903), as well as her brother, Edward Stockwell (1867–1905).

Despite the love that surrounded her in life, and the generations that came after her, there is no headstone to mark their grave, a silent, unspoken sadness in itself. But even without a physical marker, their memory lives on in the hearts of those who remember them, their stories woven into the fabric of their descendants’ lives.

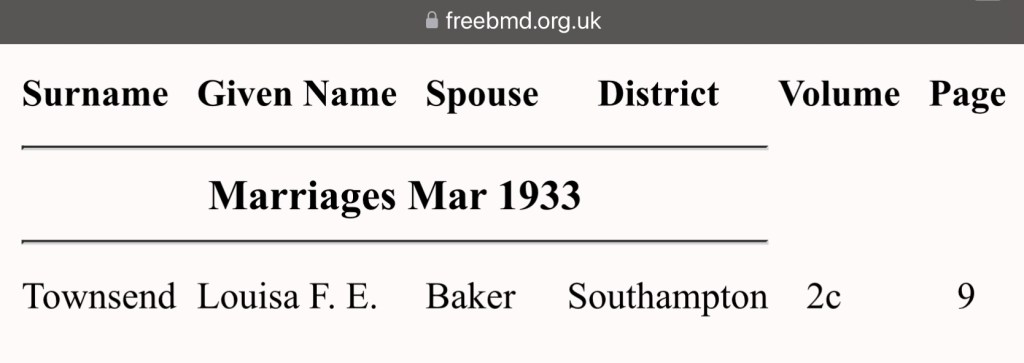

On a crisp spring Sunday, the 26th day of March 1933, Rosa and Frederick’s daughter, Louisa Florence Eliza Townsend, stood before family and friends as she married George Baker in the district of Southampton, Hampshire, England. At just 18 years old, Louisa was stepping into a new chapter of her life, carrying with her the love and resilience that had been passed down through generations.

With the ever-growing costs of tracing family history, and the sheer number of certificates already acquired to bring Rosa’s story to life, I have had to make the difficult decision not to purchase the marriage certificates of all her children. It is with deep regret that I cannot provide the finer details of Louisa and George’s special day, but for those who wish to obtain a copy of their marriage certificate, the following GRO reference can be used:

“GRO Ref - Marriages Mar 1933, Townsend, Louisa F. E, Baker, George, Southampton, Volume 2c, Page 9.”

Though the details of the ceremony remain unknown, what is certain is that Louisa, like her mother before her, was beginning a journey of love, family, and the trials and triumphs that come with building a life together.

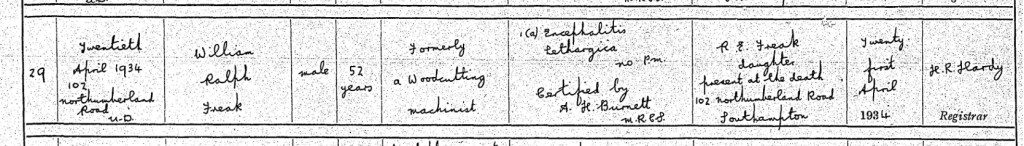

On a sorrowful Friday, the 20th day of April 1934, Rosa’s beloved brother, William Ralph Freak, passed away at the age of 52 in the home he had built for his family at Number 102, Northumberland Road, Southampton. A skilled woodcutting machinist, William had spent his life working with his hands, shaping and crafting, much like their father before him. But no amount of strength or skill could protect him from the cruel fate that awaited.

His devoted daughter, Rose Elizabeth Freak, was by his side as he took his last breath, bearing witness to the loss that would leave a hole in their family. With a heavy heart, she took on the painful duty of registering her father’s death the following day, on Tuesday, the 21st day of April 1934.

The registrar, H. R. Hardy, carefully recorded William’s details in the death register, noting the cause of death as Encephalitis Lethargica, a devastating and poorly understood neurological illness that had swept across the world between 1916 and 1930. Known as "sleeping sickness," the disease had robbed so many of their vitality, leaving them trapped in a state of paralysis and exhaustion. Though the epidemic had faded, its lingering effects continued to claim lives, including William’s. His death was certified by A. H. Burnett, M.R.C.S., but no postmortem was performed.

For Rosa, this was yet another painful loss in a life already marked by tragedy. First, her daughters, then her mother, and now her brother, each departure another scar upon her heart. But she carried on, as she always had, finding solace in the family she had built, the love she had nurtured, and the memories of those she had lost.

Encephalitis lethargica, also known as sleeping sickness, is a mysterious and devastating neurological disease that first appeared in the early 20th century, reaching epidemic proportions between 1916 and 1930. The disease affected millions of people worldwide, causing inflammation of the brain and leading to a range of severe and often long-lasting symptoms. Many of those who survived were left with permanent neurological complications, including Parkinsonian-like symptoms, catatonia, and other movement disorders. The cause of the disease remains unknown, though several theories have been proposed over the years.

The epidemic of encephalitis lethargica began during World War I and continued into the 1920s, coinciding with the outbreak of the Spanish flu pandemic. Patients affected by the disease experienced a wide range of symptoms, with the most characteristic being extreme lethargy and prolonged periods of sleep, sometimes lasting for days or weeks. Other symptoms included high fever, headache, double vision, tremors, and behavioral disturbances, with some patients developing psychotic episodes. The disease often progressed to severe neurological impairment, leaving many in a state of akinesia, where they could neither move nor respond to external stimuli.

The cause of encephalitis lethargica remains unknown, though early researchers suspected a viral or bacterial infection. Some scientists have proposed that it was linked to an immune response triggered by an unidentified pathogen, possibly related to the streptococcus bacterium. Others have speculated that the disease was associated with the 1918 influenza pandemic, but no definitive connection has ever been established. Despite extensive research, no specific pathogen has been conclusively identified as the cause.

During the height of the epidemic, treatment options were limited and largely focused on symptom management. Many patients were institutionalized due to the severe neurological and psychiatric effects of the disease. Some were treated with sedatives, stimulants, and other drugs in an attempt to alleviate symptoms, but these interventions had limited success. In the decades following the epidemic, neurologist Oliver Sacks famously experimented with L-DOPA, a medication used to treat Parkinson’s disease, on survivors of encephalitis lethargica who had developed severe movement disorders. His work, documented in the book "Awakenings," showed that some patients experienced temporary improvements in movement and consciousness, but the effects were not sustained in the long term.

The mortality rate of encephalitis lethargica during the epidemic was high, with an estimated one-third of those infected dying from the disease. Among those who survived, nearly half developed chronic neurological conditions, often leading to severe disability. Only a small percentage of patients fully recovered without long-term complications. The overall survival rate depended on the severity of the initial infection and the extent of neurological damage.

Despite extensive research, encephalitis lethargica remains a medical mystery. Although isolated cases have been reported in the decades since the epidemic, no large-scale outbreaks have occurred, and the disease is now considered rare. Scientists continue to study historical cases and modern instances of encephalitis to better understand the condition, but without a known cause, prevention and treatment remain challenging. The legacy of encephalitis lethargica persists in the field of neurology, influencing research into autoimmune diseases, viral encephalitis, and movement disorders.

Northumberland Road is a residential street located in the inner-city area of Southampton, Hampshire, England. Situated in the SO14 postcode district, it lies within close proximity to the city center, offering convenient access to local amenities and transportation links.

Historically, Northumberland Road has undergone significant changes, particularly in the mid-20th century. During World War II, Southampton endured extensive bombing, and Northumberland Road was no exception. A photograph from November 1940 captures the street during this tumultuous period, providing a glimpse into the wartime landscape.

In the post-war years, the area underwent reconstruction and development. Notably, the Northumberland Arms, a public house located at the corner of Northumberland and St. Albans Roads, has a history dating back to the early 1880s. Over the decades, it has undergone various ownership changes, reflecting the evolving social landscape of the area.

The housing stock along Northumberland Road predominantly consists of period properties built between 1800 and 1911. These dwellings contribute to the street's historical character and provide insight into the architectural styles prevalent during that era.

In more recent times, Northumberland Road has seen further development. A 1996 television report features footage of the Queensland Tavern Pub on Clovelly Road and Northumberland Road, offering a visual record of the area's appearance during that period.

Today, Northumberland Road remains a vital part of Southampton's urban fabric, reflecting the city's resilience and adaptability through the centuries. Its history, from wartime challenges to post-war reconstruction and modern-day developments, mirrors the broader narrative of Southampton's evolution.

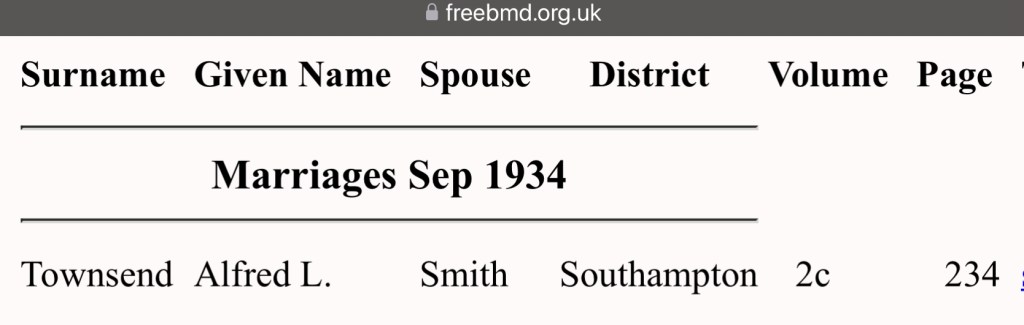

In the late summer of 1934, Rosa and Frederick’s son, Alfred Leonard Townsend, found love and a new beginning as he married Madeline Mary P. Smith in the Southampton district of Hampshire, England. At 25 years old, Alfred was stepping into a new chapter of his life, one filled with hope and promise.

Though the finer details of their wedding day remain unknown, the significance of the moment was undeniable. With the rising costs of tracing Rosa’s family history and the countless certificates already obtained to piece together her story, the marriage certificates of her children had to be left aside. It was a difficult sacrifice, but one made out of necessity.

For those who wish to hold a piece of Alfred and Madeline’s union in their hands, their marriage certificate can be ordered using the following GRO reference:

"Marriages, September 1934, Townsend, Alfred L., Smith, Madeline Mary P., Southampton, Volume 2c, Page 234."

Though Rosa had witnessed heartbreak and loss throughout her life, she had also seen her children grow, love, and build families of their own. And in those moments, weddings, births, and new beginnings, she found joy and the strength to carry on.

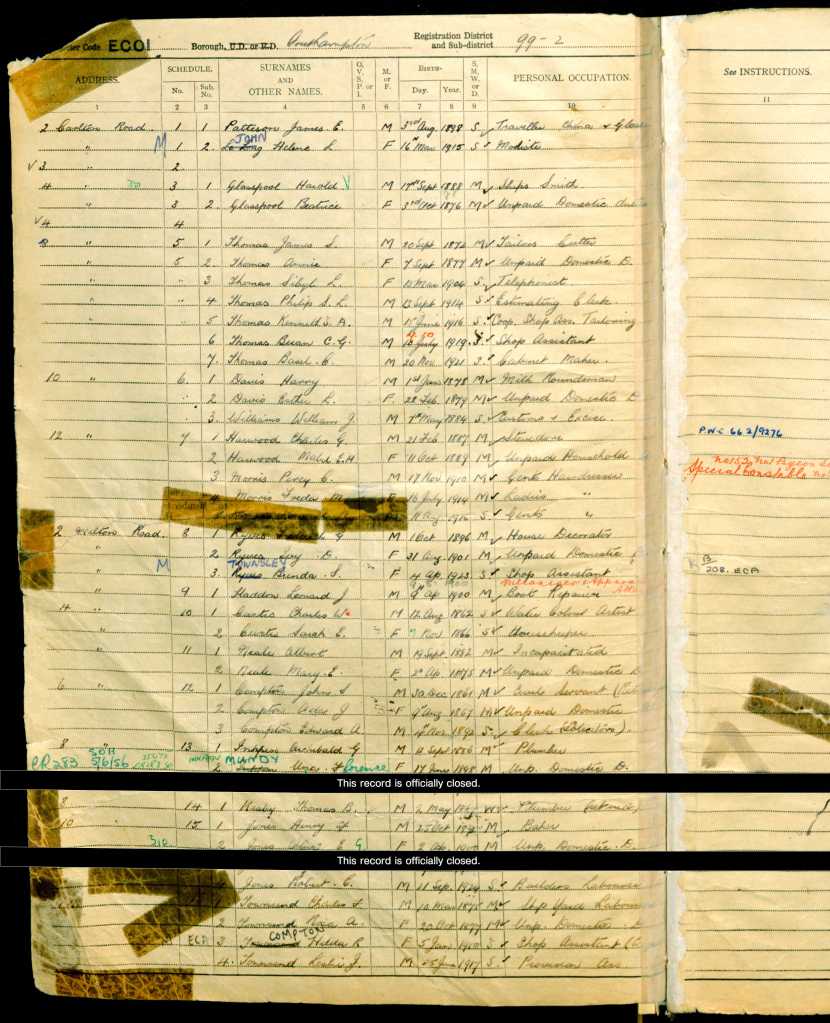

On Friday, the 29th day of September 1939, as the Second World War loomed over Britain, the National Registration was completed, documenting the lives of every citizen in the country. For Rosa and Charles Frederick, now in the later years of their lives, it marked yet another change a new home, a new chapter, and a world on the brink of war.

By this time, Rosa and Charles had moved from their long-time residence on Empress Road to Number 11, Wilton Road, Southampton, Hampshire, England. Their family had grown and spread out, with many of their children now married and building lives of their own. But under their roof remained their daughter Hilda and youngest son Leslie.

Rosa, at 61 years old, was recorded as an "unpaid domestic," a term that failed to capture the tireless devotion she had given to raising her large family. Charles Frederick, at 64, was still working, employed as a Shipyard Labourer. Their daughter Hilda, now 29, was making her way in the world as a Shop Assistant, while 22 year old Leslie worked as a Provision Assistant.

The registry carefully recorded their dates of birth, solidifying in history the details of their existence: Rosa was born on the 20th of October 1877, Charles Frederick on the 10th of March 1875, Hilda on the 5th of January 1910, and Leslie on the 25th of June 1917.

As war once again threatened their home and family, Rosa and Charles had already endured so much loss, hardship, and the challenges of raising eleven children through difficult times. Now, with the world changing around them, they faced the uncertainty of yet another global conflict, holding onto the resilience that had carried them through a lifetime of trials.

Wilton Road, located in the Shirley district of Southampton, Hampshire, has a rich history that reflects the area's transformation from agricultural land to a bustling suburban neighborhood. In the mid-1800s, the land surrounding what is now Wilton Road was primarily used for farming and smallholdings. As Southampton expanded, this area gradually developed into a residential suburb.

A notable feature near Wilton Road is St. James' Park, which was initially grazing land before becoming a nursery and later a gravel pit. In 1907, the local authority purchased the land, and by 1911, it had been landscaped into a public park. This park has since served as a central recreational area for the Shirley community.

The architectural landscape of Wilton Road predominantly consists of semi-detached houses, indicative of the area's residential character. Over the years, property values have fluctuated; for instance, detached properties have sold for an average of £500,000, while semi-detached properties have fetched around £465,000.

In 1938, Wilton Road was a well-established residential street, as evidenced by historical photographs from that period. The street has maintained its residential appeal over the decades, adapting to the evolving needs of its inhabitants.

An interesting historical artifact on Wilton Road is an 1894 Southampton Corporation Water Works (SCWW) hydrant cover, highlighting the area's longstanding infrastructure.

Today, Wilton Road continues to be a vibrant part of the Shirley community, offering residents access to local amenities, schools, and recreational facilities, all while retaining its historical charm.

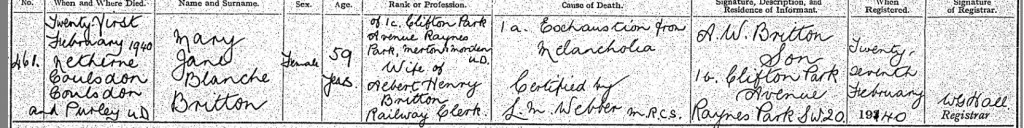

Rosa’s heart must have ached deeply when she received the news of her sister Mary Jane Blanche Britton’s passing. At 59 years old, Mary took her last breath on Wednesday, the 21st of February 1940, in the bleak surroundings of Netherne, Coulsdon, Surrey.

Mary had lived at 1c Clifton Park Avenue, Raynes Park, Merton, with her husband Albert Henry Britton, a Railway Clerk. It was her son, A. W. Britton, who carried the weight of registering her death on Tuesday, the 27th of February 1940. The registrar, W. G. Hall, recorded that Mary’s cause of death was Exhaustion from Melancholia, a devastating end that hinted at years of struggle with mental health. L. M. Webber, M.R.C.S, certified her passing.

Mary’s death was made all the more tragic by where she spent her final days. Netherne was Surrey’s fourth county asylum, built between 1907 and 1909 to relieve overcrowding at Brookwood Asylum. A place intended for care, yet often filled with isolation and suffering.

For Rosa, losing her sister in such a way must have been heartbreaking. They had grown up together, faced life’s hardships side by side, married, raised children, and carried the weight of their family’s legacy. Now, in a time of war and uncertainty, Rosa was left to mourn the loss of yet another loved one, feeling the steady thinning of the family she had once known so well.

Netherne, located between Coulsdon and Purley in Surrey, England, has a rich history that reflects significant developments in mental health care and residential communities.

Established on 18 October 1905, Netherne Hospital, initially known as The Surrey County Asylum at Netherne, was designed by architect George Thomas Hine to accommodate 960 patients. The hospital's design featured a compact arrow layout, with stepped ward blocks surrounding central facilities such as administrative offices, laundry, workshops, water tower, boilers, and a recreation hall. A freestanding chapel was situated at the front, and an isolation hospital along with a patients' cemetery were located to the north.