When Elizabeth Wren stepped into the church on that cool, spring morning in 1850, the air was thick with the quiet promise of forever. Her heart fluttered with a mixture of anticipation and uncertainty as she stood before her groom, the man who would become her world. His eyes, warm and full of quiet devotion, met hers, and in that moment, it seemed as though all the years before her had led to this single, fateful union.

The vows exchanged that day, words of love and fidelity, would shape the path she walked for the next fifty years. Would her marriage, so full of youthful hope, remain as steadfast as it appeared that morning? Or would time, as it does to all things, slowly erode the foundation they had so carefully built?

Her life as a wife and mother was not to be one without trials. The world around her was shifting, sometimes violently, in ways both familiar and unrecognizable. It was a time when society’s expectations of women were being questioned, as voices calling for change began to grow louder, and the very fabric of family, work, and purpose was being rewoven. And Elizabeth, like so many of her time, was caught between the old world she had known and the new one rapidly emerging on the horizon.

Were the days of her early marriage filled with the soft joys of shared moments, cooking for her husband, tending to the home, and nurturing the love that blossomed in the space between them. In those first years, her heart swelled with the arrival of her children, each one a living testament to her love for her husband. She dreamed of seeing them grow, of sending them out into a world where they might thrive and flourish, free from the struggles she had endured in her own childhood. I’m sure all she wished for their happiness, their health, their future.

As the years pressed on, would Elizabeth’s world became one of quiet reflection? Would she begin to question not just the choices she had made, but the life she had been handed? The industrial revolution was reshaping the landscape, bringing new ideas, new challenges, and new hopes to the people she had once known. The cities grew, and the lives of the people she loved seemed increasingly distant from the land she had come to love. Elizabeth’s once-simple life, filled with domestic comforts and quiet joys, was now overshadowed by the questions of a world she could hardly understand, much less control. But in her heart, she would have carried with her a wisdom that came from having lived through these changes, having borne witness to a time of transformation that few could comprehend fully.

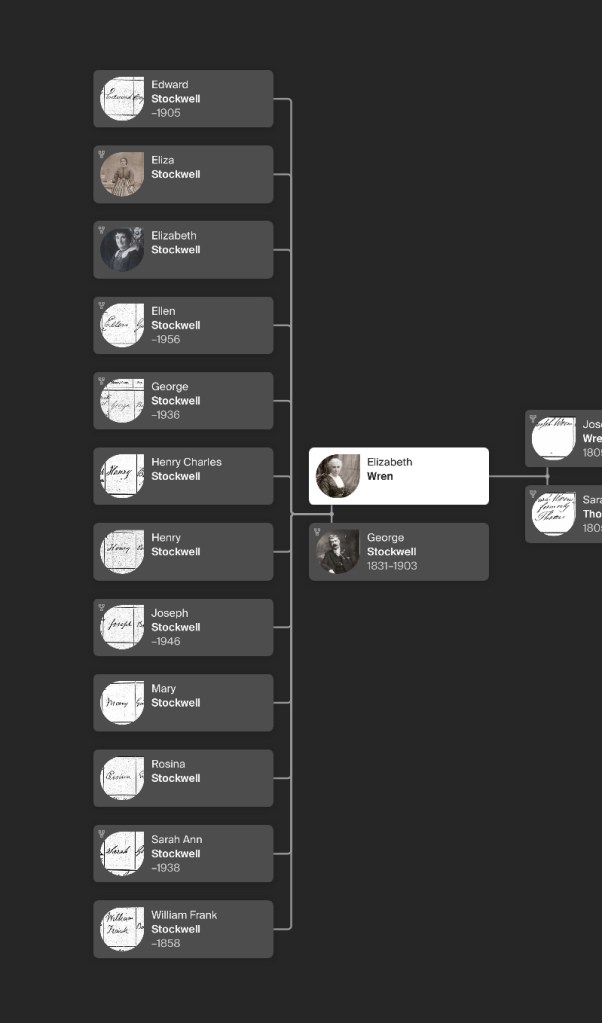

By the time Elizabeth reached the twilight years of her life, the world around her was nearly unrecognizable. The comforts of her youth, the familiar rhythms of her home, had long since faded into memory. Her children, though they thrived and flourished in their own ways, were now scattered far and wide, each carving their own path in the ever-changing world. She had done her best, given everything she had, loved as fiercely as she could, and raised her children with the hope that they might find happiness in a world that had been anything but kind to her and her family.

In the final years of her life, Elizabeth Wren stood at the edge of an era. She had seen love and loss, triumph and tragedy, and had lived through the kind of hardships that would shape the future for generations to come. Her heart, though worn and scarred by time, remained ever steadfast, no longer bound by the naive hopes of youth but tempered by the quiet wisdom that can only come with age. I’m sure as she looked back on the years that had passed, on the dreams she had once held, the love she had given, the children she had nurtured, and the family she had built, there was no bitterness in her heart, only a deep sense of peace.

For Elizabeth, the story of her life was not one of simple happiness, but of perseverance, of resilience, of a woman who had weathered the storms of life with quiet grace and courage. As the years grew fewer and fewer, did she know that, in the end, it would be love, both the love she had given and the love she had received, that would carry her through to the very end. And so, as she stood on the threshold of her final days, did she face them not with fear, but with the quiet strength of a woman who had lived fully, loved deeply, and found, in the end, her peace.

Welcome back to the year 1849, Portswood, South Stoneham, Hampshire, England. The air is thick with the scent of coal smoke drifting from chimneys, mingling with the dampness of the nearby River Itchen. The roads are busy with carts and pedestrians navigating the uneven paths, and the sound of hammering from distant shipyards echoes across the landscape. Portswood, once a quiet rural area, is experiencing the effects of Southampton’s rapid expansion as trade and industry thrive.

Queen Victoria sits on the throne, her reign shaping Britain’s identity in the mid-19th century. She is a symbol of stability in an era of change, and her husband, Prince Albert, is deeply involved in promoting science, industry, and public works. In Parliament, Lord John Russell serves as Prime Minister, leading a Whig government that grapples with economic challenges, social reform, and the lingering impact of the Irish famine. The Houses of Parliament, recently rebuilt after the devastating fire of 1834, stand as a testament to Britain’s power, though inside, fierce debates rage about public health, urban poverty, and industrial expansion.

Fashion in 1849 reflects the rigid class distinctions of the time. Wealthy women wear voluminous dresses with crinolines, high necklines, and delicate lace details, their hair swept into intricate updos adorned with combs and ribbons. Gentlemen of means dress in frock coats, waistcoats, and top hats, their starched collars framing serious faces. Meanwhile, the working class wear practical and worn garments—women in simple dresses and shawls, men in rough wool coats and sturdy boots, their clothes often showing the dirt and strain of hard labor.

Transportation in Portswood and Southampton is changing as the railway extends its reach, connecting the region to London and beyond. The London and South Western Railway has already made travel faster and more efficient, allowing goods and people to move more freely than ever before. Horse-drawn carriages and carts still dominate the roads, kicking up mud and dust as they jostle over uneven surfaces. For those who cannot afford the railway, travel remains slow and arduous, with long walks or cramped coach journeys the only options.

Energy in 1849 is still largely dependent on coal and manual labor. Factories and homes rely on coal fires for warmth, while gas lighting, though spreading in cities, is still uncommon in rural and suburban areas like Portswood. Most homes rely on candles or oil lamps, casting flickering light into the evening darkness. The air in cities is thick with industrial smoke, and blackened buildings stand as a testament to the growing dominance of coal-fueled industry.

Heating and lighting remain rudimentary. Coal fires provide warmth in wealthier homes, while the poor often make do with little fuel, shivering through the harsh winter months. Gas lighting is a luxury reserved for the wealthy and for public spaces in major cities, while most homes continue to use candles and oil lamps. In the narrow streets of Southampton, the glow of gas lamps begins to illuminate the way, but in rural areas, darkness still falls quickly after sunset.

Sanitation is a growing concern, as Britain’s cities and towns struggle with the consequences of rapid urbanization. Cholera is a constant fear, and in 1849, another deadly outbreak devastates London and other parts of the country. The miasma theory, the belief that bad air causes disease, leads to efforts to clean up cities, but sewage still flows freely through many streets, and drinking water is often contaminated. In poorer areas, multiple families are crammed into damp, overcrowded dwellings, while wealthier households enjoy cleaner, more spacious accommodations.

Food varies greatly between the classes. The rich dine on meats, fresh vegetables, and exotic fruits imported from the empire, while the poor survive on bread, potatoes, and whatever scraps they can afford. In Southampton, markets bustle with traders selling fish, poultry, and seasonal produce, but prices are high, and many struggle to afford even basic meals. Public houses serve ale and simple fare, offering a rare comfort for laborers at the end of a long day.

Entertainment provides an escape from the hardships of daily life. Theatres in Southampton host plays and musical performances, while the working class find their amusement in taverns, street performers, and the occasional fair. Newspapers carry the latest gossip about the royal family, political scandals, and sensational crimes. Penny dreadfuls, cheap serial novels filled with thrilling tales, are a popular distraction for those who can read, offering stories of highwaymen, ghosts, and daring adventures.

The environment in 1849 is changing. Industrialization brings both prosperity and pollution. Southampton’s docks are busier than ever, but the air is thick with soot, and the once-clear rivers and streams are becoming tainted with waste. In rural areas, traditional farming continues, but the encroachment of industry is inevitable. Portswood, once a quiet village, is beginning to feel the pressures of expansion, as new housing and businesses spread outward from the city.

Gossip fills the streets and drawing rooms. People whisper about the latest royal pregnancies, the marriages of the upper class, and the ever-present scandals of politicians and businessmen. Murmurs of revolution still linger from the European uprisings of 1848, though in Britain, fears of political upheaval are easing. Instead, people debate the future, will the railway bring prosperity or displace traditional ways of life? Will the growing influence of the middle class change the rigid social order?

The difference between the rich, the working class, and the poor is stark. The aristocracy and upper middle class live in grand houses with servants attending to their every need, their children educated in the classics and destined for prestigious careers. The working class toil long hours in factories, docks, or domestic service, scraping together a modest existence with little hope of upward mobility. The poor, especially in urban slums, live in squalor, facing disease, hunger, and backbreaking labor just to survive.

Historical events shape the world beyond Portswood. The Great Famine continues to ravage Ireland, driving waves of desperate immigrants to British cities in search of work. In London, the cholera epidemic claims thousands of lives, leading to calls for better sanitation and public health measures. Across the Atlantic, tensions over slavery and expansion stir conflict in the United States, while in Europe, the aftershocks of the 1848 revolutions continue to unsettle governments.

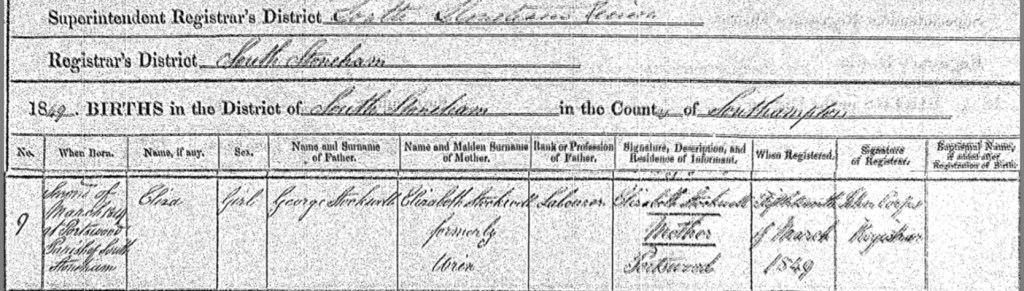

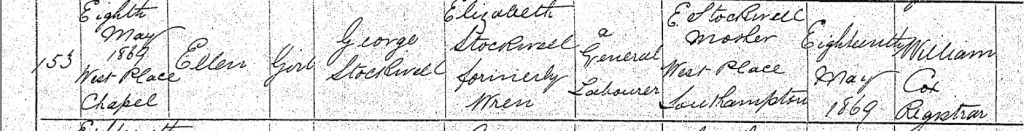

On a gentle spring day, as the world stirred with new life, Elizabeth Stockwell welcomed her firstborn into the world, a daughter, whom she and George lovingly named Eliza. The morning of Friday, the 2nd of March, 1849, marked the beginning of a new chapter, not just for Elizabeth as a mother, but for the little family she and George were beginning to build in Portswood, South Stoneham, Hampshire.

The tiny cries of newborn Eliza filled their humble home, a sound both fragile and powerful, a reminder of the delicate balance of life, of all the heartache Elizabeth had known, and of all the love she had yet to give. As she held her daughter for the first time, Elizabeth must have felt the weight of the moment, knowing that the journey of motherhood would bring both immense joy and inevitable sorrow, as she had witnessed in her own mother’s life.

Thirteen days later, on Thursday, the 15th day of March, Elizabeth made her way to the registrar’s office to officially record her daughter’s birth. The registrar, whose name is difficult to decipher in the historical record, documented that Eliza was the daughter of George Stockwell, a labourer, and Elizabeth Stockwell, formerly Wren, of Portswood. With this simple act, Eliza’s existence was etched into history, a name on a page, a life just beginning.

For Elizabeth and George, their daughter’s birth was a symbol of hope, of love carried forward through generations. In a world where nothing was guaranteed, Eliza was theirs, her tiny fingers grasping onto her mother’s, her future unwritten, yet full of endless possibility.

Portswood, located in the historic parish of South Stoneham in Hampshire, has a rich and evolving history that reflects the broader changes in the region over centuries. Situated just to the north of Southampton, Portswood originally consisted of rural farmland and scattered settlements, with little more than small villages and isolated farms. Its location, near the River Itchen and with access to key roads, made it a strategic area for development as Southampton expanded.

The area was originally part of the South Stoneham parish, which was known for its agricultural landscape and rural nature. The name "Portswood" itself likely refers to the presence of woodlands or forested areas used for timber and other resources. The "Port" part of the name may refer to its proximity to the city of Southampton, which was an important port town even in medieval times. Early records of Portswood are somewhat sparse, but it is believed to have been a quiet, agricultural area for much of the medieval period. By the 18th century, the area began to see the first signs of urban development, particularly due to the growth of Southampton as a thriving port. The expansion of the town brought a greater demand for housing, services, and infrastructure, and Portswood, located on the outskirts of the town, became an attractive area for residential development. As trade and industry flourished in Southampton, it was no longer just a rural area but was becoming increasingly integrated into the city’s expansion.

The 19th century saw further changes as railways and roads connected Portswood to Southampton and other neighboring areas. The construction of the railway station in the mid-19th century was particularly important, as it allowed easier access to the city and the surrounding areas, making it a prime location for people to settle. During this time, Portswood transitioned from a quiet rural area to a more suburban environment, with new housing developments springing up to accommodate the growing population.

One of the defining features of Portswood during the Victorian and Edwardian eras was its role as a working-class suburb. The rapid industrialization of Southampton and its docks led to a population boom, with many workers moving to the area for housing. As the middle class expanded, so did the need for schools, shops, and places of worship. Portswood responded to these needs, with local schools, churches, and other community institutions becoming increasingly central to its identity. Throughout the 20th century, Portswood continued to develop. It became a key residential area for both local workers and university students, especially with the expansion of the University of Southampton in the post-war years. This demographic shift brought a more diverse population to the area and led to the development of student accommodation, cafes, and cultural spots that made it an exciting place for young people. Its proximity to the university and transport links to the city center made Portswood a popular location for students, as well as professionals working in and around Southampton.

Over the years, Portswood has retained much of its traditional suburban character but has also seen considerable redevelopment, particularly in the late 20th and early 21st centuries. New housing estates, shops, and commercial developments have replaced some of the older buildings, and the area continues to grow as part of Southampton’s expanding urban fabric. However, parts of Portswood have maintained their historical charm, with period homes and local businesses still standing as a testament to its past.

Today, Portswood is a vibrant and diverse area, home to students, families, and professionals. The area’s rich history, from its agricultural roots to its role in Southampton’s urban growth, is still visible in its streets and architecture. While much of the rural landscape has been replaced by modern developments, remnants of Portswood’s history remain an important part of the area’s identity, ensuring that it continues to reflect both the past and present of Southampton.

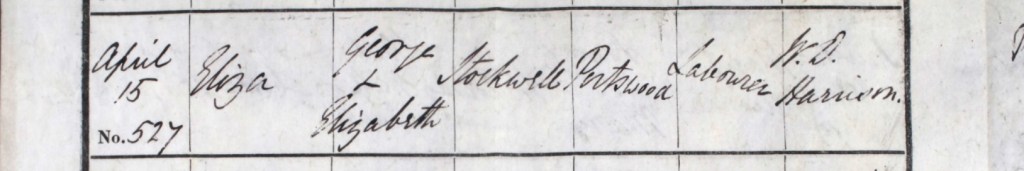

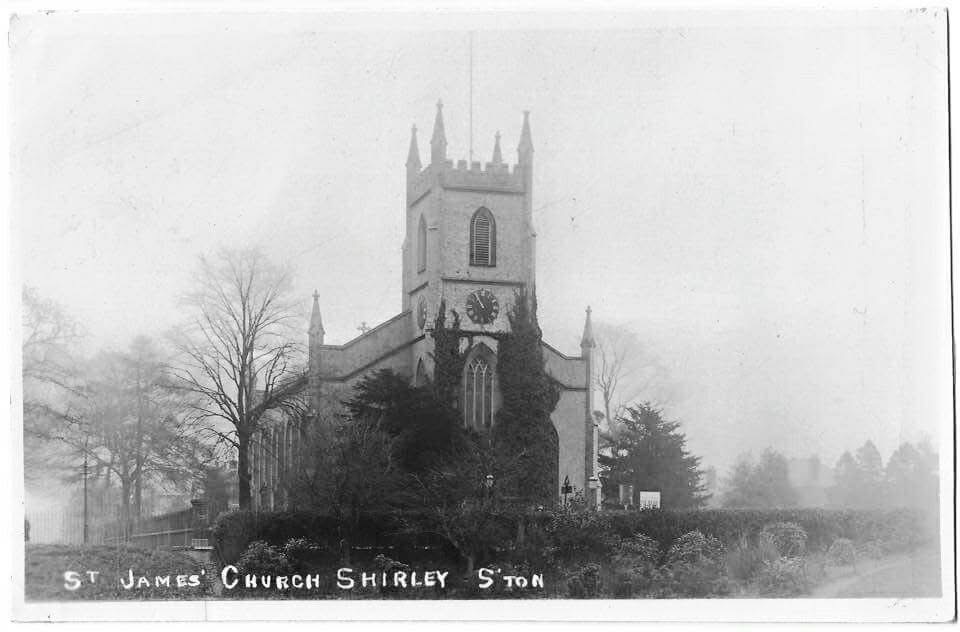

On Sunday, the 15th day of April 1849, Elizabeth and George Stockwell carried their infant daughter Eliza to the doors of St Mary’s Church in South Stoneham, Hampshire. The morning light filtered through the stained-glass windows, casting soft colors onto the stone floors as the family stood before the baptismal font, ready to present their child to God.

For Elizabeth, this moment must have been deeply significant, a sacred tradition passed down through generations, marking the beginning of her daughter's spiritual journey. As Rev. W.D. Harrison gently poured the blessed water over Eliza’s tiny head, she was officially welcomed into the church, her name recorded in the baptism register alongside those of her parents. The entry confirmed that George was a labourer and that the family resided in Portswood, a modest detail in the register, but a testament to their place in the world.

Elizabeth had witnessed this ritual many times before, watching her younger siblings receive their own baptisms, some of whom had left this world far too soon. Perhaps she whispered a silent prayer that her little Eliza would grow strong, that she would be spared the sorrow of an early grave, that the waters of baptism would wash over her like a promise of a future filled with love, health, and happiness.

As they stepped out of the church, the crisp spring air wrapped around them, and Elizabeth held her daughter close, cherishing the weight of her in her arms. In that moment, nothing else mattered, Eliza was theirs, a child of faith, a child of hope, a child deeply loved.

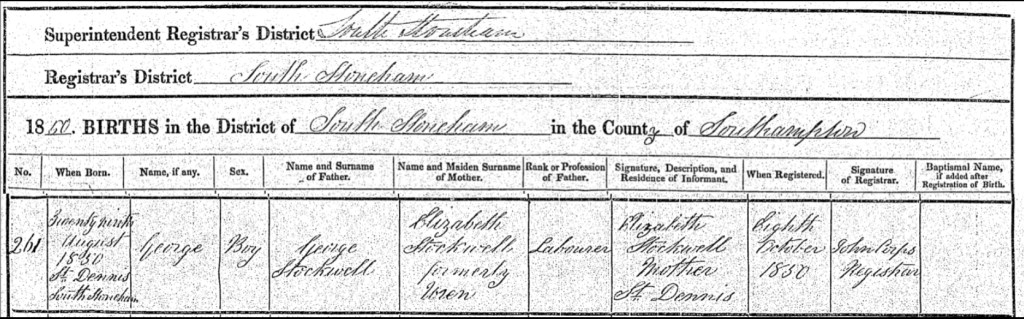

On Thursday, the 29th day of August 1850, Elizabeth Stockwell once again experienced the miracle of motherhood as she brought her second child into the world, a son, whom she and George named after his father. Born in St. Denis, South Stoneham, Hampshire, baby George entered a world that was both beautiful and uncertain, a world where love and hardship walked hand in hand.

In the quiet moments after his birth, as she cradled him in her arms, Elizabeth must have felt a familiar rush of emotion, the overwhelming love of a mother, the quiet fears that came with bringing a child into a world that could be both kind and cruel. She had known loss too many times before, had watched her own mother bury child after child, and she must have whispered a silent prayer that her little boy would be strong, that he would have a future filled with opportunity and joy.

On Tuesday, the 8th day of October, Elizabeth made the journey to the South Stoneham register office to officially record her son’s birth. Perhaps she carried him in her arms, wrapped tightly against the autumn chill, or maybe she left him at home in the loving care of his father or a neighbor. When she stood before the registrar, John Corps, he carefully recorded the details: George Stockwell, son of George Stockwell, a labourer, and Elizabeth Stockwell, formerly Wren, residing in St. Denis. With a few strokes of the pen, baby George’s place in the world was made official.

As Elizabeth left the office that day, the document tucked safely away, she may have glanced down at her son and smiled, knowing that this was just the beginning of his story. A story yet to be written, filled with the laughter of childhood, the trials of adulthood, and the unbreakable bond of family.

St Denis, located within the historic parish of South Stoneham, Hampshire, carries with it a name that hints at deep historical roots. Though now largely forgotten as a distinct settlement, the name itself suggests religious and medieval significance. "St Denis" is likely a reference to Saint Denis, the 3rd-century patron saint of France, whose veneration spread to England, particularly following the Norman Conquest. The presence of a place named after him suggests that at some point, there may have been a chapel, manor, or religious foundation dedicated to the saint in the area. South Stoneham, historically a widespread parish, encompassed several smaller settlements, including Swaythling, Portswood, and Bitterne. The parish was shaped by agriculture, woodlands, and the River Itchen, which provided an essential resource for milling, fishing, and transportation. The mention of St Denis as a specific location within this landscape implies that it may have once been a notable estate, a religious site, or even a small hamlet.

Medieval records of South Stoneham suggest that the area was dominated by large landholdings and church-owned lands. The manor of South Stoneham was historically linked to Winchester Cathedral, and religious influence in the region was strong. If St Denis had been the site of a chapel or an estate tied to the church, it would have played a role in the local economy and daily life, though it may never have been more than a small outlying settlement. By the 18th and 19th centuries, South Stoneham and its surrounding areas were still largely rural, though the growing importance of Southampton as a port and commercial hub was beginning to change the landscape. The introduction of turnpike roads and later the railway led to increasing urbanization. It is likely that any distinct settlement of St Denis was absorbed into this transformation, fading from local maps as larger villages and suburbs expanded.

The 20th century saw the continued spread of Southampton’s suburban areas, with much of South Stoneham becoming residential and commercial land. Many old place names disappeared from common use, replaced by modern developments and shifting boundaries. Today, St Denis does not appear as a distinct locality on contemporary maps, but historical records and references suggest that it was once an identifiable part of the wider South Stoneham landscape.

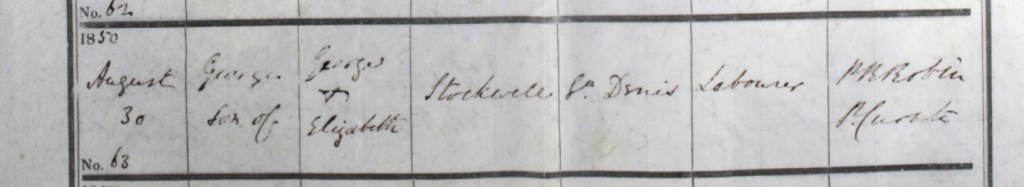

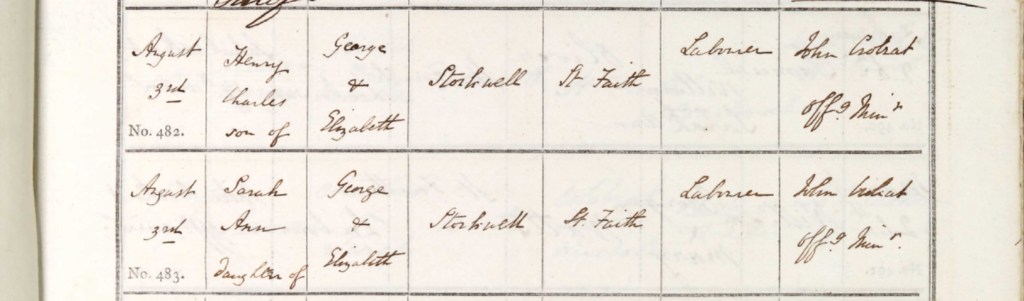

On Friday, the 30th day of August 1850, just one day after his birth, baby George Stockwell was carried into the sacred halls of St. Mary’s Church in South Stoneham to be baptised. The faint cries of the newborn echoed softly through the stone walls as his parents, Elizabeth and George, stood before the minister, ready to present their son to God.

For Elizabeth, this moment must have been a mixture of relief and reverence. Baptism was not just a ceremony, it was a rite of passage, a spiritual protection, and an act of faith. She had seen too much loss in her lifetime, had held and loved siblings who had not survived beyond infancy. In a world where life was fragile, especially for the children of labouring families, baptism felt like a safeguard, a plea to the heavens to watch over her precious boy.

The minister, whose name is now faded with time, solemnly recorded the details in the church register. Another George Stockwell now stood among the parish records, father and son forever linked by name. The simple words on the page confirmed his existence, his family, his place in the world: son of George, a labourer, and Elizabeth Stockwell, of St. Denis.

As the ceremony ended, Elizabeth may have pressed a gentle kiss to her son's forehead, whispering a silent promise to protect him, to love him, to give him the best life she could. With faith in her heart and hope for the future, she carried baby George out of the church and into the waiting world, ready to begin the next chapter of their journey together.

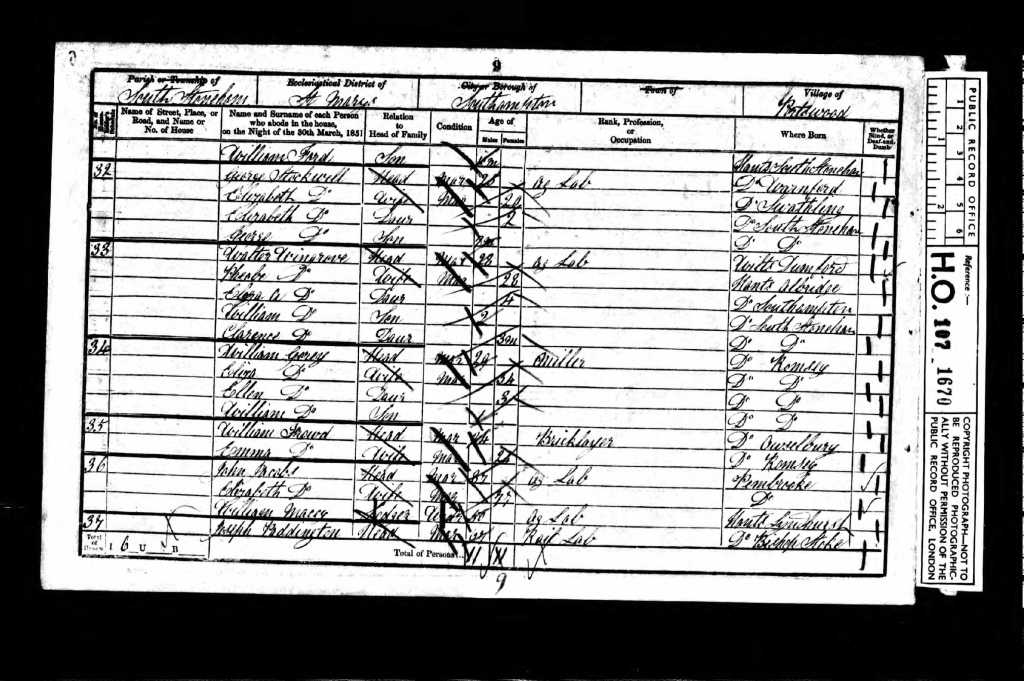

On the eve of the 1851 census, as the last light of Sunday, the 30th day of March, faded into dusk, Elizabeth Stockwell sat within the modest home she shared with her husband George in Portswood, South Stoneham. The air was still, save for the distant sounds of the village settling into night, perhaps the crackling of a hearth, the muffled conversations of neighbors, or the occasional cry of a child. Within her own walls, Elizabeth had all she held dear, her husband, her children, and the quiet rhythm of family life.

Beside her stood George, a hardworking agricultural labourer, his hands calloused from long days spent in the fields. He bore the weight of providing for his family, rising each morning with the sun to toil on the land, returning home weary but steadfast. Elizabeth, too, worked tirelessly, caring for their two young children, Elizabeth and George, ensuring their little home remained warm and full of love.

Their daughter, Eliza, barely two years old, may have been nestled in her mother’s lap, her tiny fingers curling around the fabric of Elizabeth’s dress, while baby George, just seven months old, slept soundly nearby. These were the quiet moments, the ones that often went unrecorded, yet they were the very essence of life, love found in the simplest of things, in the soft glow of a candle, in the whispered hush of a lullaby.

That night, as the census taker’s ledger awaited their names, Elizabeth may have paused for a moment to reflect on all that had brought her to this place. She had known hardship and sorrow, but she had also built a family of her own. As she lay down to rest, her children safe within arm’s reach, she could only hope that the future would be kind, that the life she and George were building would be one of strength, security, and love.

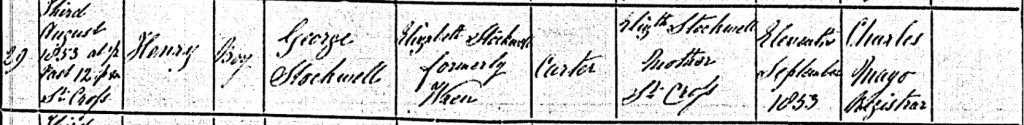

The summer of 1853 brought both joy and great change to Elizabeth’s life as she welcomed two new souls into the world, twins, a boy and a girl. In the quiet, early hours of the 3rd day of August, within their home in Saint Cross, Winchester, Elizabeth labored through the night. At 12:30 in the morning, her son Henry took his first breath, his cries breaking the silence of the darkened room. Just fifteen minutes later, at 12:45, his sister Sarah followed, their fates forever intertwined as they entered the world together.

The arrival of twins must have been met with both excitement and trepidation. Two tiny mouths to feed, two fragile bodies to nurture, it would be no small task. But Elizabeth, now a mother of four, knew well the weight of responsibility. She had felt the sting of loss before, had laid siblings and children alike to rest in the cold earth of Saint Nicholas Churchyard. Perhaps, as she held her newborns, she whispered silent prayers, willing them to be strong, to survive, to thrive.

Weeks later, on Sunday the 11th day of September, Elizabeth made the journey to the registrar’s office, carrying the weight of her growing family with her. Charles Mays, the registrar, carefully inked their names into the birth registry: Henry, a boy, and Sarah, a girl, children of George Stockwell, now recorded as a caster, and Elizabeth Stockwell, formerly Wren, of St. Cross.

Life in Winchester would be different from Portswood, but Elizabeth, ever resilient, would adapt. With four little ones depending on her, she had no choice but to press forward, finding strength in the love that surrounded her.

St Cross, Winchester, Hampshire, England, is a place steeped in history, faith, and tradition. Nestled in the peaceful water meadows of the River Itchen, just south of Winchester, the Hospital of St Cross is one of the oldest and most beautiful almshouses in England. The name "hospital" does not refer to a medical institution but rather to its original purpose as a place of hospitality and charity, offering shelter and sustenance to the poor, elderly, and travelers. Founded in the twelfth century, it has stood for nearly nine hundred years, preserving its medieval architecture and continuing its centuries-old mission of providing aid to those in need.

The origins of St Cross can be traced back to the reign of King Stephen, when Henry of Blois, the powerful Bishop of Winchester and grandson of William the Conqueror, established the institution around 1136. Henry of Blois was not only a church leader but also a statesman, a patron of the arts, and a man of great influence. Inspired by his travels to France and the hospices run by religious orders there, he founded St Cross to provide shelter, food, and care for the poor and needy. The hospital was endowed with lands and income to sustain its charitable work, and it became one of the wealthiest religious foundations of its kind in medieval England.

The buildings of St Cross are remarkable in their preservation and grandeur. The church, built in the Norman and early Gothic styles, is almost cathedral-like in its proportions. Its high vaulted ceilings, massive columns, and beautiful stained-glass windows create an atmosphere of reverence and timelessness. The almshouses, cloisters, and medieval gatehouse complete the scene, making it one of the finest surviving examples of monastic architecture. The entire complex exudes a sense of history, as if time has barely touched its stones.

Throughout the centuries, St Cross remained a place of charity and Christian service. It survived the turbulence of the Reformation, when many religious institutions were dissolved under Henry VIII. Although some of its lands were confiscated, the hospital itself was spared, and it continued to provide alms and shelter. In later centuries, it adapted to changing social conditions while remaining true to its original mission.

One of the most famous traditions of St Cross is the "Wayfarer’s Dole," which has been given to travelers for centuries. Any visitor who knocks on the door of the porter’s lodge can still receive a small beaker of beer and a morsel of bread, a custom said to date back to the hospital’s founding. This tradition reflects the medieval practice of hospitality, where religious houses and hospices offered food and drink to those in need.

Over time, the hospital became home to two distinct groups of brethren. The first, known as the Brothers of St Cross, followed the original foundation and wore black robes with a silver cross. Later, in the fifteenth century, Cardinal Beaufort, another Bishop of Winchester, established a second order within St Cross called the Order of Noble Poverty. These brethren wore red robes with a silver cross, leading to the nickname "the Black and Red Brothers" for the residents of the almshouse.

Despite its medieval origins, St Cross remains an active institution. The hospital continues to provide accommodation for elderly men, known as the brethren, who live within its historic buildings. The tranquil surroundings, including the beautiful gardens and the gentle flow of the River Itchen nearby, create a serene setting that has attracted visitors, writers, and artists for generations.

St Cross has often been described as a place frozen in time, where the echoes of history still linger. The connection to Winchester, with its great cathedral and royal past, adds to its significance, making it a site that bridges the medieval and the modern. It stands as a testament to the enduring power of charity and faith, a rare example of an institution that has remained true to its founding principles for nearly a millennium.

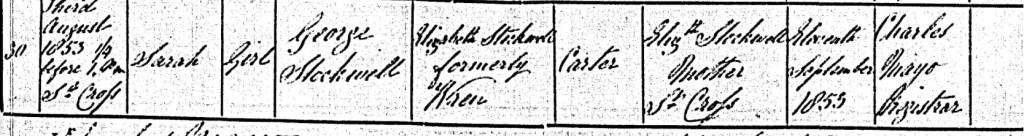

On a summer’s day, Wednesday, the 3rd day of August, 1853, Elizabeth and George Stockwell made their way to St. Cross with St. Faith Church in Winchester, the sacred place where their two precious twins, Henry Charles and Sarah Ann, would be baptised. The timing of the ceremony was both poignant and urgent. The twins, so new to the world, had arrived just hours earlier, at 12:30 and 12:45 in the morning, their tiny bodies still fragile, their futures uncertain.

Baptism was a moment of spiritual significance in those days, a ritual believed to offer protection, a safeguard for children so vulnerable in their early days of life. Yet Elizabeth, no stranger to hardship, must have been exhausted, her body still recovering from the rigors of childbirth. The physical toll of giving birth to twins, coupled with the emotional weight of fear and worry for their well-being, surely made this day even more overwhelming. The birth of Henry and Sarah had come with such a mix of joy and anxiety. In a world where infant mortality was far too common, Elizabeth and George would have been deeply aware of the precious fragility of life.

The minister, John Crokat, performed the ceremony and recorded the event in the church’s baptism register. Henry Charles and Sarah Ann Stockwell were marked as the son and daughter of George Stockwell, a labourer, and Elizabeth Stockwell, of St. Faith. They were baptised on the very same day they were born, a quickness that speaks volumes about the concerns that must have weighed heavily on Elizabeth’s heart.

It is likely that Elizabeth, despite her exhaustion, saw this act as a necessary step, a form of hope, of asking for divine protection over her beloved children. Perhaps, in those moments as her twins were brought forward, she whispered prayers of gratitude and protection, hoping beyond hope that they would survive to grow and thrive. The worries of a mother, raw and real, cannot be overstated, but neither can the strength it took to carry on.

St Cross with St Faith Church, located in Winchester, Hampshire, is a place of rich history and deep religious significance. Situated within the picturesque surroundings of St Cross, the church is part of the larger complex that includes the medieval Hospital of St Cross, one of England’s oldest almshouses. The church itself, though often overshadowed by the grandeur of the hospital, holds its own place in Winchester’s ecclesiastical history, blending the spiritual legacy of the town with centuries of faith and tradition.

The history of St Cross Church dates back to the founding of the Hospital of St Cross itself in the 12th century. The church was originally part of the religious and charitable foundation established by Henry of Blois, the Bishop of Winchester, in 1136. The bishop’s vision was to create a hospital that would provide shelter, food, and medical care to the poor, elderly, and travelers. The church served as the spiritual center for the residents of the hospital, and over the centuries, it has remained a significant part of the complex’s life, providing a place of worship and reflection for the community and visitors alike.

Architecturally, St Cross Church is a striking example of early Norman and Gothic design, with elements of both styles visible in its structure. The church was built with stone, its long, simple nave leading to a high altar at the far end. The Norman influences are evident in the thick, rounded arches and the solid construction, which was designed to withstand the test of time. Over the centuries, the church has undergone some changes and additions, but its fundamental structure remains largely unchanged since the medieval period.

The church was initially dedicated to St Faith, a Christian martyr whose feast day is celebrated on October 6th. St Faith’s dedication reflects the hospital’s role as a place of care and charity, as the saint was known for her unwavering faith in the face of persecution. The church was later referred to as "St Cross with St Faith" due to the strong connection between the hospital and the church's role as a spiritual hub for the hospital's residents.

The role of the church within the hospital complex has always been central to the lives of the brethren, the elderly men who lived at St Cross. The church was not only a place of regular worship but also a site for daily prayers and the spiritual care of the hospital’s residents. The clergy who administered the church were responsible for leading services and ensuring the continued religious education of the brethren. The church also played a key role in the spiritual wellbeing of the many travelers who sought refuge at St Cross, providing them with the opportunity to rest, pray, and seek solace before continuing on their journey.

Over the years, St Cross with St Faith Church has experienced several changes, especially during periods of religious and social upheaval. The English Reformation in the 16th century led to the dissolution of many religious foundations, but St Cross and its church were spared from dissolution due to their relatively small size and lack of significant wealth. During the Victorian period, there were efforts to restore and preserve the church, as the surrounding area gained more recognition for its historical and architectural value.

The church's surroundings, particularly the cloisters and gardens of the hospital, provide a serene and peaceful environment that enhances the experience of visiting. The river Itchen, which runs near the site, adds a natural beauty that complements the quiet dignity of the church and hospital buildings. Over the centuries, the church has remained a place of pilgrimage for those interested in its history, its spiritual significance, and its architectural beauty.

St Cross with St Faith Church is also known for its enduring role in the community. The church continues to host regular services, offering a spiritual home to both the residents of St Cross and members of the wider community. Visitors to the church are often struck by its sense of tranquility and timelessness, as if stepping into a space where centuries of faith and tradition have created an atmosphere of quiet reverence.

The church has not only been a religious space but also a focal point for various ceremonies and important events. The hospital’s annual celebrations, as well as special feast days dedicated to St Faith, continue to be observed with services and gatherings that reflect the long-standing traditions of the hospital and the church. The continued function of the church as both a place of worship and a symbol of the community’s commitment to charity underscores the enduring legacy of St Cross.

In addition to its religious functions, the church is an important part of the architectural and historical landscape of Winchester. The Hospital of St Cross and its church are an integral part of the city’s rich heritage, providing insight into the medieval period, the history of charitable institutions, and the religious life of England. For historians, pilgrims, and those interested in the architectural beauty of medieval churches, St Cross with St Faith Church offers a unique glimpse into the past, standing as a lasting testament to the faith and generosity that shaped the community of St Cross.

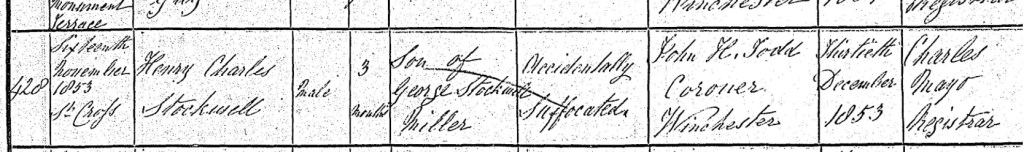

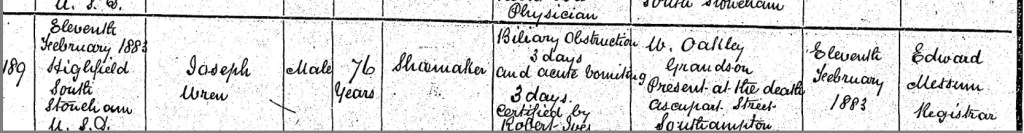

Tragedy struck with devastating force when, on Wednesday the 16th day of November, 1853, Elizabeth and George’s precious son, Henry Charles, just three months old, accidentally suffocated to death at their home in St Cross, Winchester. The loss of such a tiny life, so full of promise, left a gaping hole in the hearts of his grieving parents. To lose a child so young, in the most tragic and unexpected of ways, must have shattered the quiet joy that had only recently blossomed in their lives.

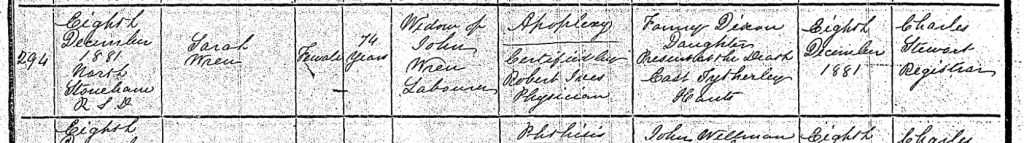

The events surrounding Henry Charles’ death remain shrouded in silence. The only official record of that fateful day comes from the Winchester coroner, John H. Todd, who formally registered Henry’s death on Tuesday the 13th day of December, 1853. The registrar, Charles Mays, documented in the death registry that Henry Charles Stockwell, a mere three-month-old infant, had tragically suffocated at St Cross on the 16th of November. Despite the records, the sorrow that Elizabeth and George must have felt is immeasurable. There were no detailed accounts in the newspapers of the time that could shed light on the specifics of the event.

It is heart-wrenching to imagine the agony Elizabeth must have endured, cradling her child in her arms only to lose him in such a fleeting moment. The grief of losing a child, especially in such an unexpected and unexplainable manner, would have been unbearable. The shock of the loss would have undoubtedly left her emotionally broken, and George, too, must have felt an immense weight of despair. They had already known the sting of loss before, but to lose their youngest child, just as they had begun to dream of his future, must have been a sorrow beyond words.

In the quiet of their home, Henry’s absence would have been felt in every corner, in every moment that passed without the sound of his cries, the warmth of his tiny hands. Elizabeth and George would have had to find the strength to carry on, though their hearts were broken, as they slowly navigated the deep, dark ache of losing their beloved son.

Elizabeth and George's hearts were shattered as they said their final goodbyes to their beloved son, Henry Charles, on Sunday, the 20th of November, 1853. The pain of losing him was a wound that would never fully heal. With heavy hearts, they laid their precious baby boy to rest at St. Cross with St. Faith Church in Winchester, Hampshire. The church, a place that had once welcomed Henry Charles for his baptism just months earlier, now became the site of his sorrowful burial.

The minister, John Crokat, performed the burial service with quiet reverence, acknowledging the profound grief of the young parents as they stood by the tiny grave. In the burial register, he recorded the sorrowful truth that Henry Charles Stockwell, from St. Faith, was buried on that cold November day, just four months old. Though his life was fleeting, Henry Charles’ memory would live on in the hearts of Elizabeth and George, forever marked by the tragic loss they had suffered.

As the earth was gently placed over their son’s grave, Elizabeth and George must have been consumed by a deep, unspoken sorrow. The sound of the minister’s voice, the weight of the ceremony, all would have seemed a blur as their hearts broke into a thousand pieces. No parent should ever have to face such a loss, but in the face of their unimaginable grief, Elizabeth and George would have clung to the love they had for Henry Charles, even as they were forced to say goodbye far too soon.

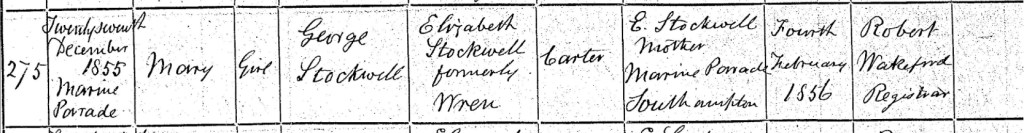

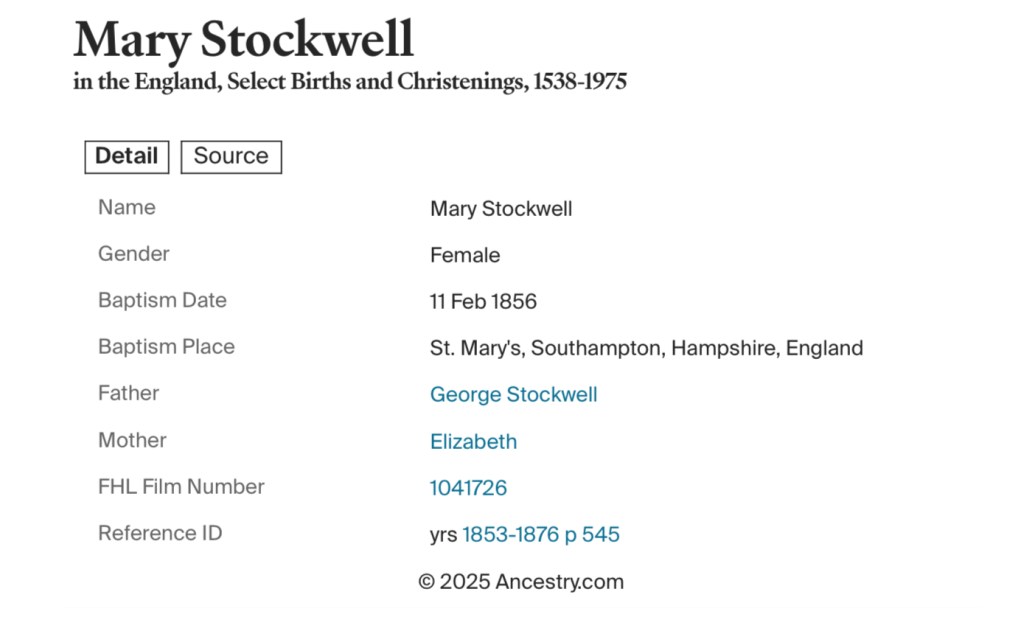

Elizabeth and George’s hearts, though still heavy with the loss of their son Henry Charles, found a glimmer of hope with the arrival of their daughter, Mary Stockwell, on Thursday, the 27th day of December, 1855. Mary’s birth brought a much-needed light into their lives, as the couple welcomed their precious daughter at Marine Parade, Southampton, Hampshire, England.

In the early days of the new year, Elizabeth made her way to the Southampton registry office to officially register her daughter’s birth. On Monday, the 4th day of February, 1856, Elizabeth’s name was recorded alongside that of her daughter, Mary, in the birth register. The registrar, Robert Wakeford, documented the important details: Mary, a little girl, was the daughter of George Stockwell, a Carter, and Elizabeth Stockwell, formerly Wren, who resided at Marine Parade, Southampton.

Although their hearts still carried the pain of past losses, the birth of Mary was a beacon of love and hope in their lives. Elizabeth and George must have found solace in the gentle presence of their daughter, holding her close, knowing that she would bring joy into their home once more. Mary, though born into a world marked by tragedy, would undoubtedly become the centre of her parents' affection and devotion, helping to heal the wounds that time could never fully erase.

On a winter’s morning, just weeks after welcoming their daughter into the world, Elizabeth and George carried little Mary in their arms and made their way to St. Mary’s Church, Southampton. It was Monday, the 11th of February, 1856, a day that marked Mary’s introduction into the Christian faith.

The stone walls of the church stood tall and solemn as the family stepped inside, the air filled with the faint scent of candle wax and damp wood. The echoes of their footsteps on the stone floor must have mingled with hushed whispers of other parishioners gathered to witness the sacred ceremony. As they approached the font, Elizabeth and George looked down at their infant daughter, swaddled in soft cloth, her tiny features peaceful and unknowing of the world around her.

The minister gently poured the blessed water over Mary’s forehead, marking the beginning of her spiritual journey. The sound of prayers and blessings filled the air as the baptism was recorded in the register a testament to Mary’s place within the church and her family’s enduring faith.

For Elizabeth and George, this moment was not just a religious duty but an act of hope. After all the heartbreak they had endured, they held onto the belief that Mary’s future would be bright, that she would grow strong and live a life filled with love. As they stepped out of the church that day, the winter sun breaking through the clouds, they must have whispered a quiet prayer, that this child would remain safe in their arms, untouched by the tragedies that had shadowed their past.

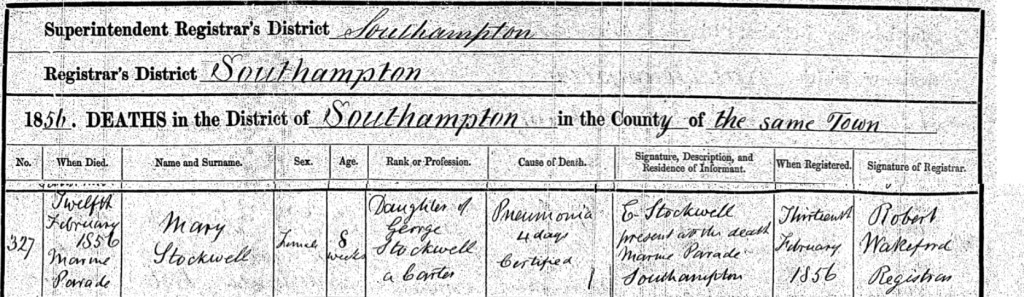

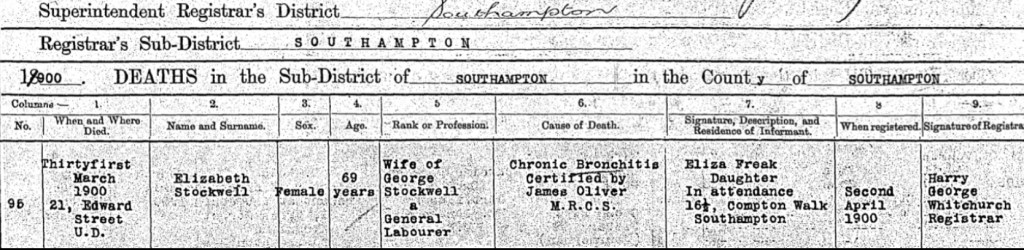

Just one day after Mary’s baptism, as her mother Elizabeth still held onto the warmth of that sacred moment, the cruel hand of fate stole their daughter away. On Tuesday, the 12th day of February 1856, just eight weeks after she had entered the world, Mary Stockwell took her final breaths in the home where she had been so dearly loved. The small house on Marine Parade, Southampton, which had once been filled with the soft sounds of a newborn stirring, now fell silent with grief.

Elizabeth was there, holding her tiny daughter, watching helplessly as life slipped away. How many times had she pressed a kiss to Mary’s forehead, hoping the warmth of a mother’s love could chase away the fever that gripped her fragile body? How many prayers had she whispered into the cold night air, pleading for a miracle that never came? Pneumonia had taken hold, and despite all her desperate efforts, there was nothing more she could do.

The following day, with a breaking heart, Elizabeth made the painful journey to register Mary’s death. The same hands that had cradled her child, had soothed her cries, now trembled as she signed her name before the registrar, Robert Wakeford. Only a day earlier, he had recorded Mary’s baptism, an entry of hope and new beginnings. Now, he solemnly wrote her name once more, this time marking the end of a life barely begun.

Mary Stockwell, daughter of George and Elizabeth, had succumbed to pneumonia after just four days of illness. Her death was certified, yet no piece of paper could capture the depth of sorrow that settled over her grieving parents. The weight of their loss was immeasurable, a wound that no time or prayer could ever truly heal.

Pneumonia, historically known as "the captain of the men of death" due to its severe impact, has been recognized since ancient times. The first descriptions date back to around 460 BC by Hippocrates, who identified it as a disease that causes inflammation of the lungs. Over the centuries, various epidemics and outbreaks have highlighted its deadly potential, including during the 1918 influenza pandemic.

In terms of treatment, antibiotics have revolutionized pneumonia management, particularly since the discovery of penicillin by Alexander Fleming in 1928. Today, antibiotics remain a cornerstone in treating bacterial pneumonia, while viral pneumonia may require antiviral medications if available. Supportive care, such as oxygen therapy and fluid management, is crucial in severe cases to help patients recover.

Prevention includes vaccination against common bacterial and viral pathogens that cause pneumonia, such as Streptococcus pneumoniae and influenza viruses. Additionally, maintaining good hygiene practices, avoiding smoking, and addressing underlying health conditions like HIV or chronic lung disease can reduce the risk of developing pneumonia.

Overall, while advances in medicine have significantly improved outcomes, pneumonia continues to pose a serious global health challenge, particularly among vulnerable populations such as the elderly and those with weakened immune systems.

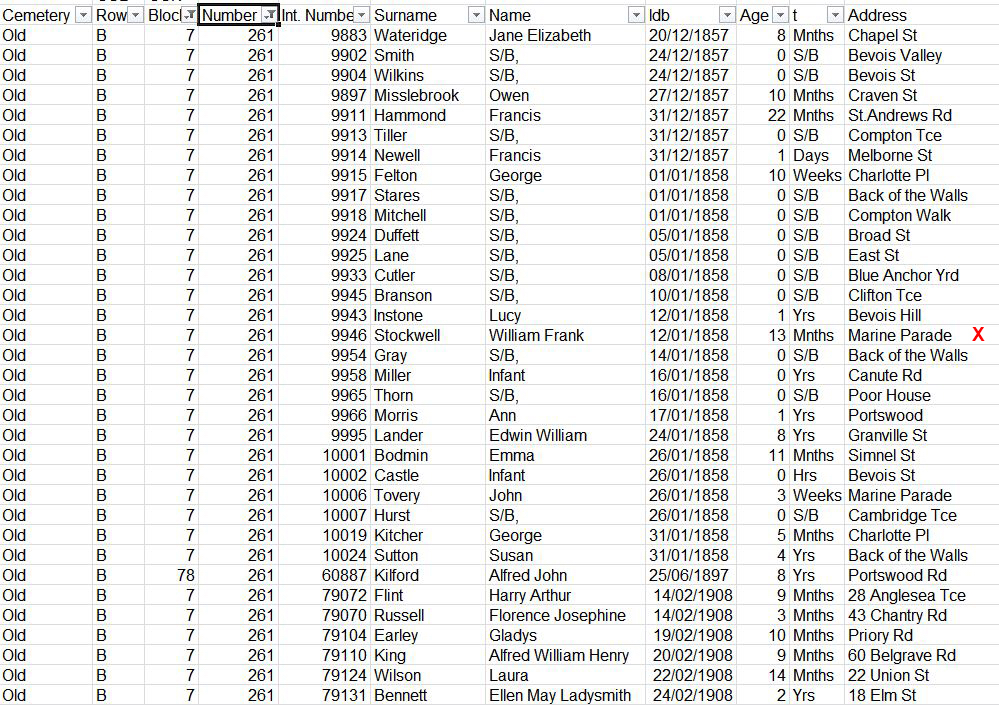

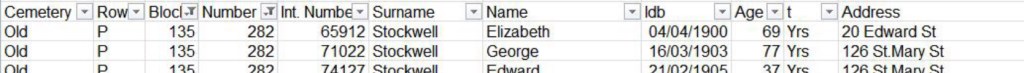

On a cold and sorrowful Sunday, the 17th day of February 1856, Elizabeth and George Stockwell made the heartbreaking journey to Southampton Old Cemetery, where they laid their beloved daughter, Mary, to rest. The weight of their grief was immeasurable as they walked the quiet paths of the cemetery, their footsteps heavy with sorrow.

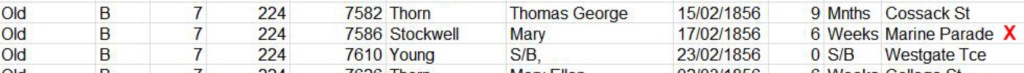

Mary, just eight weeks old, was buried in Row B, Block 7, Grave Number 224. She was the 7,586th soul to be interred in that sacred ground, yet to her grieving parents, she was not just another number, she was their daughter, their precious child, taken from them far too soon.

As the small coffin was lowered into the earth, Elizabeth and George would have clung to each other, their hands entwined in silent grief. The bitter February wind carried whispers of sorrow through the cemetery, rustling the bare branches above as if nature itself mourned alongside them.

There were no grand headstones or elaborate memorials for the daughter of a humble carter and his wife. Just a simple grave, marked only by love and loss, a resting place for a child who had barely begun her journey in life.

As the final prayers were spoken, I am sure Elizabeth longed to hold Mary once more, to press her to her chest, to feel the rise and fall of her breath. But all she could do now was whisper a final goodbye, leaving a piece of her heart there in the cold earth, where her baby girl would sleep forever.

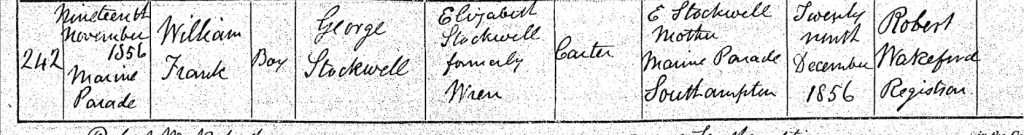

Elizabeth and George welcomed a new light into their lives when their son, William Frank Stockwell, was born on Wednesday, the 19th day of November 1856, at their home on Marine Parade, Southampton. After so much loss, his arrival must have been both a comfort and a reminder of the fragility of life.

More than a month later, on Monday, the 29th day of December 1856, Elizabeth made her way to the registry office in Southampton, her infant son nestled safely in her arms. She had made this journey before, too many times in grief, but this time, with hope. As she stood before the registrar, Robert Wakeford, she provided the details of her son’s birth, each word a quiet promise of the life she prayed he would have.

William Frank Stockwell, a boy. The son of George Stockwell, a carter, and Elizabeth Stockwell, formerly Wren. Born in their home by the sea, where the wind carried the scent of salt and possibility.

With her mark upon the document, Elizabeth sealed the first official record of her son’s life. A simple piece of paper, yet one filled with all the love and dreams she had for him.

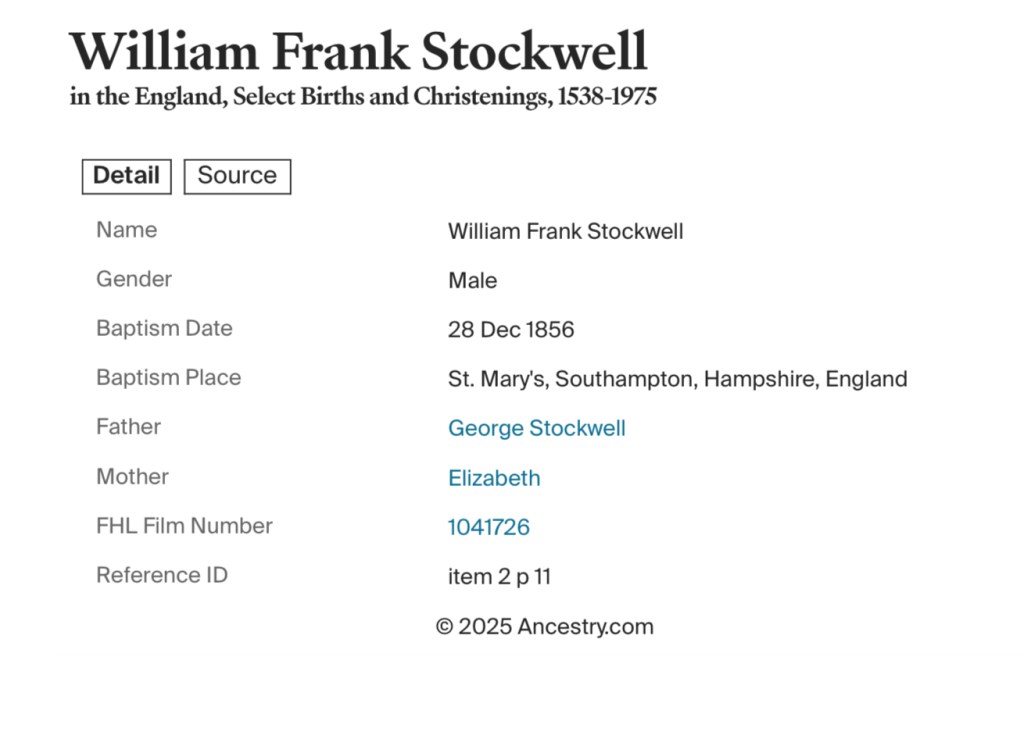

On a crisp winter morning, Sunday the 28th day of December 1856, Elizabeth and George carried their infant son, William Frank Stockwell, to St. Mary’s Church in Southampton. The church, standing solemn and steadfast, had witnessed their joys and sorrows alike, and now, beneath its towering arches, they sought a blessing for their newborn son.

As the minister spoke the sacred words, water was gently poured over William’s tiny head, a symbol of protection and faith. In that moment, surrounded by the echoes of prayers and the flickering candlelight, Elizabeth must have held her breath, silently pleading that this child, this precious son, would be granted a long and healthy life.

William Frank Stockwell, a boy born of love, now carried the weight of his family’s hopes as he was welcomed into the faith, his name recorded in the baptism register of St. Mary’s Church.

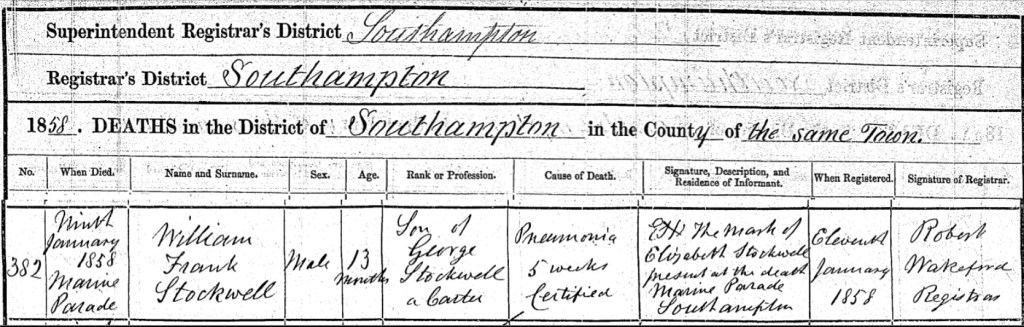

The weight of loss bore down upon Elizabeth once more as she cradled the lifeless body of her precious son, William Frank. William had sadly passed away at their home, on Saturday the 9th day of January 1858. Just thirteen months old, his short life had been filled with the warmth of his mother’s arms, the gentle lullabies she whispered in the quiet hours, and the unspoken dreams she had for his future. But now, as the harsh January winds howled outside their home on Marine Parade, Southampton, all those dreams had been stolen away by the cruel grip of pneumonia.

Elizabeth had known this heartbreak before, but it never lessened. Watching yet another child slip away, feeling his tiny fingers go cold in hers, it was a pain that words could never truly capture. And yet, even in the depths of her sorrow, she found the strength to do what no mother should ever have to: she made that long, tear-filled walk to the registry office once more.

On Monday, the 11th of January 1858, with her heart shattered, Elizabeth stood before the registrar, Robert Wakeford, and uttered the words that made the nightmare real. William Frank Stockwell, her beautiful boy, had lost his battle with pneumonia after five agonizing weeks. As the ink dried on the register, sealing her grief into official record, Elizabeth, her hands trembling, her vision blurred by tears, placed her mark, an X. A silent testament to a mother’s unrelenting sorrow.

On a bitter January morning, the grieving footsteps of Elizabeth and George Stockwell echoed through Southampton Old Cemetery as they made the unbearable journey to lay their infant son, William Frank, to rest. The weight of loss pressed upon them with each step, the cold air biting against their tear-streaked faces.

On Tuesday, the 12th day of January 1858, they stood at the edge of an open grave, Row B, Block 7, Number 261, where their beloved William Frank would be buried. But he would not rest alone. In the cruel reality of infant mortality, this grave had already received the tiny bodies of others, 33 innocent souls taken too soon. The youngest among them had never even drawn breath, stillborn and nameless, while the oldest had barely reached 22 months.

There was no small coffin set apart, no tenderly carved headstone for William Frank. Instead, he was lowered into the shared earth alongside the others, a stark and sorrowful testament to the fragility of life. There were no grand words spoken, only the quiet sobs of his mother, the unspoken grief of his father, and the heavy silence of a world that kept turning despite their devastation.

As the grave was filled, Elizabeth and George knew they would have to walk away, leaving their baby behind in the cold ground. But how could a mother turn her back on her child? How could a father step away, knowing his son’s laughter would never again fill their home?

And yet, they did. Because they had no choice. Because life, despite its cruelty, demanded they carry on. But I’m sure as Elizabeth left that cemetery, her heart shattered beyond repair, she carried with her the unbearable weight of yet another child lost, another piece of her soul buried beneath the earth.

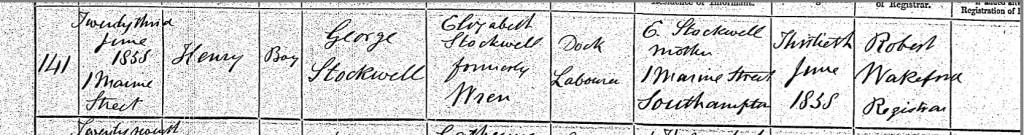

Elizabeth’s arms, so often left empty by grief, were once again filled with new life when she gave birth to her son, Henry Stockwell, on Wednesday, the 23rd day of June 1858. The walls of their home at Number 1, Marine Street, Southampton, had witnessed both the joys of birth and the unbearable sorrow of loss, and now, with Henry’s arrival, hope flickered once more in the hearts of his weary parents.

A week later, on Wednesday, the 30th day of June, Elizabeth set out on a familiar yet always bittersweet journey to the Southampton registry office. As she stepped through its doors, she carried not just the weight of her newborn son in her arms, but the memories of the children she had lost before him. The registrar, Robert Wakeford, recorded in the birth register that Henry Stockwell, a boy, was the son of George Stockwell, a Dock Labourer, and Elizabeth Stockwell, formerly Wren, of Number 1, Marine Street.

Though Elizabeth signed the document, she knew that ink and paper could never capture the depth of a mother’s love or the silent prayers she whispered for her son’s future. With each child she had birthed, she had learned to cherish every fleeting moment, never knowing how long they would be granted to her. As she held Henry close, she must have wondered, would he be the one to stay? Would he grow strong and fill their home with laughter? Or would fate, as it had so many times before, come to steal him away too soon?

For now, there was no answer, only the steady rise and fall of Henry’s tiny chest against hers, a rhythm of life that she held onto with all her heart.

Marine Street in Southampton, Hampshire, is a locale with a rich history that reflects the city's maritime heritage and urban development. Situated in the Chapel area of Southampton, Marine Street once connected Marine Parade to Melbourne Street, forming part of a vibrant community near the waterfront.

The Chapel area, where Marine Street was located, has long been associated with Southampton's maritime activities. In the 19th century, this district was a bustling hub, characterized by a network of streets that housed workers and their families involved in the city's thriving port and shipbuilding industries. The proximity to the docks made it a convenient residence for those whose livelihoods were tied to the sea.

Marine Street itself was emblematic of the working-class neighborhoods that flourished during this period. The street was lined with modest terraced houses, accommodating the growing population drawn to Southampton by employment opportunities. The community was tight-knit, with residents relying on local amenities such as pubs, shops, and schools that catered to their daily needs.

However, the mid-20th century brought significant changes to Marine Street and its surroundings. Urban redevelopment initiatives aimed at modernizing the city led to the demolition of many old structures in the Chapel area. Marine Street was among those affected, with demolitions occurring around 1961. This transformation was part of a broader effort to revitalize Southampton, which had suffered damage during World War II and was adapting to contemporary urban planning trends.

The absence of a baptism record for Henry raises haunting questions. Had Elizabeth and George, after so much heartache, begun to lose faith in the God they had once turned to in their times of joy and sorrow? With each tiny coffin they had laid in the cold earth, with every whispered prayer that had gone unanswered, did they begin to wonder if there was anyone listening at all?

Elizabeth had not only buried five of her own children but had also lived through the deaths of her younger siblings, tiny souls snatched away by illness and circumstance. She had walked the same paths to the churchyard over and over, carrying the weight of grief that no mother should bear. She had watched as her babies were lowered into the ground, helpless against the cruelty of a world that seemed determined to break her.

Perhaps, by the time Henry was born, she could no longer find it in herself to stand before an altar and offer him up to a God who had taken so much from her. Perhaps she still believed, but her faith was now wrapped in bitterness and doubt. Or perhaps, in the quiet of her home, she whispered her own private prayers over her newborn son, not trusting the church but still pleading with the heavens to let him stay.

Whatever the truth may be, Henry’s missing baptism speaks to a woman who had endured more than most. Whether it was an act of defiance, despair, or simple exhaustion, it leaves us wondering, how much loss can one heart take before it stops believing in miracles altogether?

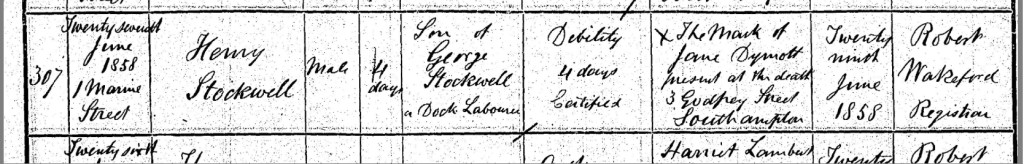

Four days. Just four fleeting days was all the time Elizabeth had with her newborn son, Henry. After carrying him within her for months, feeling his tiny kicks, dreaming of the life he might lead, she barely had a chance to hold him before he slipped away.

On that Sunday, the 27th day of June, 1858, in the small, cramped home on Marine Street, death came quietly once more, stealing yet another child from Elizabeth’s aching arms. But this time, it was not she who registered his passing. Instead, on Tuesday the 29th day of June, their neighbour, Jane Dymott, took on the burden, a silent testament to Elizabeth’s unbearable grief. How could she bear to walk into that registry office again, to utter the same heartbreaking words, to sign her name with that sorrowful mark, an ‘X’ that had become the signature of her suffering?

The cause of death, debility, a vague and cruel term, meant little in the face of the reality. He had simply been too small, too fragile, too weak for this world. There was no fight, no lingering illness, just a life barely begun and then suddenly gone.

How must she have felt, standing in the empty silence of her home, the weight of yet another death pressing down upon her? Did she rage at the heavens? Did she sink into despair? Or had she, after so many losses, become numb to the pain, her tears long since drained away?

Henry never had the chance to grow, to laugh, to cry out for his mother’s touch. And Elizabeth, a mother in mourning once again, was left with nothing but memories of the briefest of moments, a heartbeat in time, gone too soon.

Debility, a term historically used to describe general weakness or a decline in physical or mental strength, has been recognized in medical literature for centuries. It was often associated with aging, chronic illnesses, and post-infection recovery. In earlier times, debility was a common diagnosis for unexplained fatigue and frailty, frequently mentioned in 19th-century medical texts and often linked to conditions such as tuberculosis or malnutrition.

The treatment of debility has evolved significantly. In the past, remedies included herbal tonics, rest cures, and dietary improvements. The Victorian era saw the rise of so-called "nerve tonics" and patent medicines, many of which contained stimulants like caffeine or even opiates. Today, treatment depends on the underlying cause. If debility stems from a chronic illness, managing the primary condition is key. Nutritional support, physical therapy, and lifestyle modifications such as regular exercise and a balanced diet can help improve strength and overall well-being.

Prevention of debility involves maintaining a healthy lifestyle, managing stress, ensuring adequate sleep, and addressing any medical conditions that could lead to physical decline. In older adults, preventing falls, staying active, and engaging in social activities are also crucial in reducing the effects of debility.

While the term is less commonly used in modern medical practice, the concept remains relevant, particularly in geriatrics and rehabilitation medicine, where improving quality of life and functional capacity is a priority.

Under the somber summer sky, Elizabeth and George walked the now-familiar path to Southampton Old Cemetery, their hearts burdened with yet another unbearable loss. On Thursday, the 1st day of July 1858, they laid their precious son, Henry, to rest in an open grave, Row C, Plot 13, Number 270, a place now marked only by sorrow and the weight of countless tiny lives lost too soon.

Henry was the 10,445th soul to be interred there, yet to Elizabeth, he was not just a number in the cemetery’s growing register. He was her baby, her love, her hope, now cradled not in her arms, but in the cold embrace of the earth.

Did she whisper a final lullaby as they lowered him down? Did she press one last kiss to his lifeless brow before saying goodbye? Or did she simply stand in silence, staring at the fresh earth, unable to find words for the grief that threatened to swallow her whole?

It was an unmarked grave, an open resting place shared with others, gone too soon, strangers in life, now bound together in death. There was no headstone to bear Henry’s name, no lasting marker to say that he had ever existed at all. Only his mother’s breaking heart would forever remember the son she had held for just four days.

As the soil was placed over him, sealing another chapter of sorrow, one might wonder, was this the moment Elizabeth stopped believing? How could any merciful God take so many innocent lives, leave a mother with empty arms time and time again? How many more children would she be forced to bury before fate allowed her to keep one?

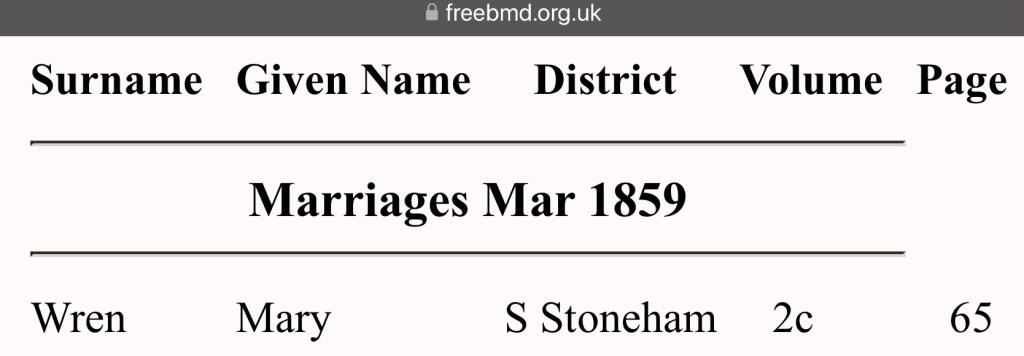

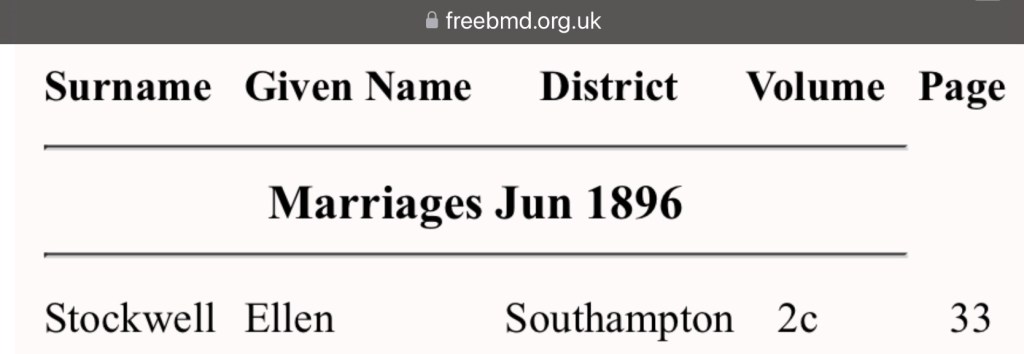

It was on Sunday, the 16th day of January 1859, that Elizabeth’s sister, Mary Wren, married William Oakley in Chilworth, Hampshire, England. A new chapter began for Mary, as she stepped into married life, building a future with her husband.

While the details of their wedding day remain just out of reach, the official record stands as proof of their union. Due to the rising costs of family research, obtaining every marriage certificate has become a challenge, but for those who wish to uncover more, a copy can be obtained through the General Register Office using the following reference:

GRO Reference – Marriages Mar 1859, Wren, Mary, Oakley, William, S. Stoneham, Volume 2c, Page 65.

As Elizabeth continued to navigate the hardships and joys of her own life, she may have found comfort in knowing that her sister Mary had embarked on her own journey, one filled with the same hopes and uncertainties that marriage and family life had brought to her.

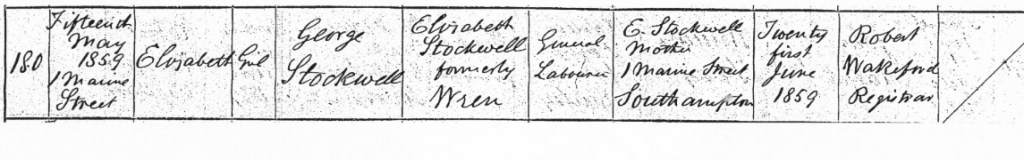

After so much loss, a new life entered the world, Elizabeth Stockwell, born on Sunday, the 15th day of May 1859, at the family’s home on Marine Street in Southampton. Perhaps, for a fleeting moment, her mother Elizabeth felt the stirrings of hope, the warmth of possibility that this child would be different, that this daughter would stay.

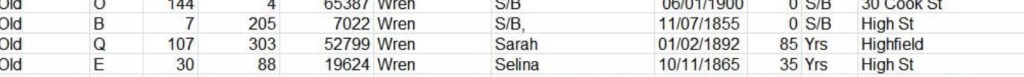

On Tuesday, the 21st day of June 1859, Elizabeth once again made the familiar journey to the Southampton register office to record the birth of her namesake. Robert Wakeford, the registrar, carefully noted in the birth register that baby Elizabeth was the daughter of George Stockwell, a general labourer, and Elizabeth Stockwell, formerly Wren, of Number 1, Marine Street.

Did Elizabeth smile as she spoke her daughter’s name aloud, as she gave the necessary details? Or did she hesitate, the weight of the past pressing against her, knowing that many of her children's names had been written in both the birth and death registers within heartbreakingly short spans of time?

This new Elizabeth was a symbol of resilience, a testament to her mother’s strength and unwavering love. Would fate be kinder this time? Would this child grow strong, filling their home with laughter instead of sorrow? Or would the cruel hands of fate, which had stolen so many before her, come knocking once again?

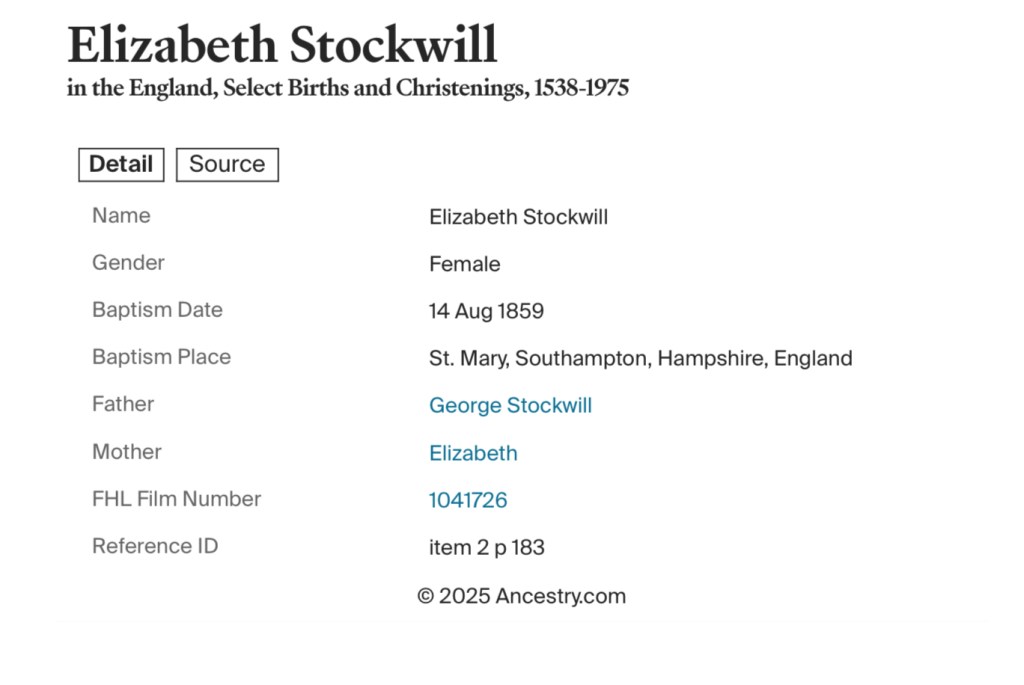

On Sunday, the 14th day of August 1859, Elizabeth and George carried their infant daughter to St Mary’s Church in Southampton, where she was baptised before God. As the minister performed the sacred rite, the cool stone walls of the church bore silent witness to yet another moment of devotion in Elizabeth’s life, a life that had seen more heartbreak than most could endure.

Was this baptism an act of faith, a desperate plea for divine protection over her newborn child? Or was it simply tradition, a ritual carried out because it had always been done? After losing so many before, did Elizabeth still dare to believe that this child would be different, that she would be given the chance to grow, to live, to love?

With the echoes of the minister’s words still lingering in the air, Elizabeth and George left the church, their daughter safely in their arms. They had done all they could. Now, all they could do was wait, wait and hope that this Elizabeth would survive where so many had not.

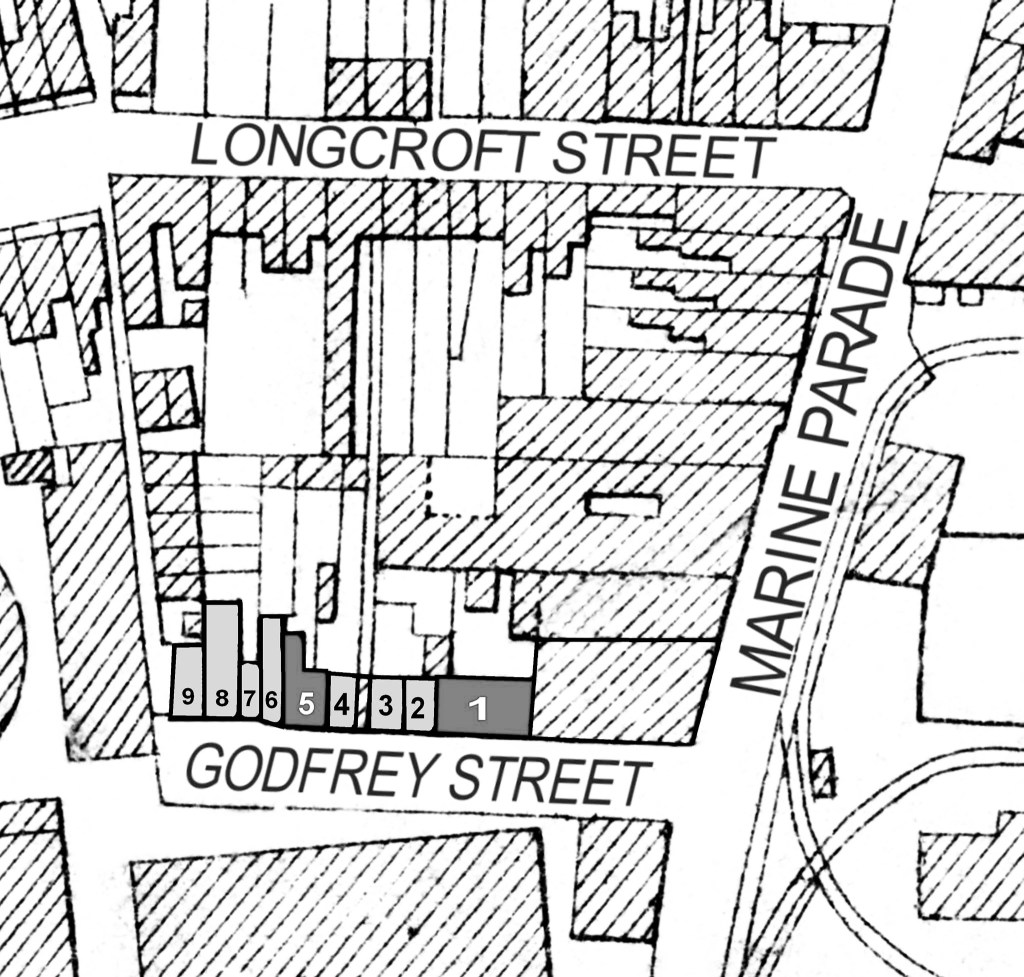

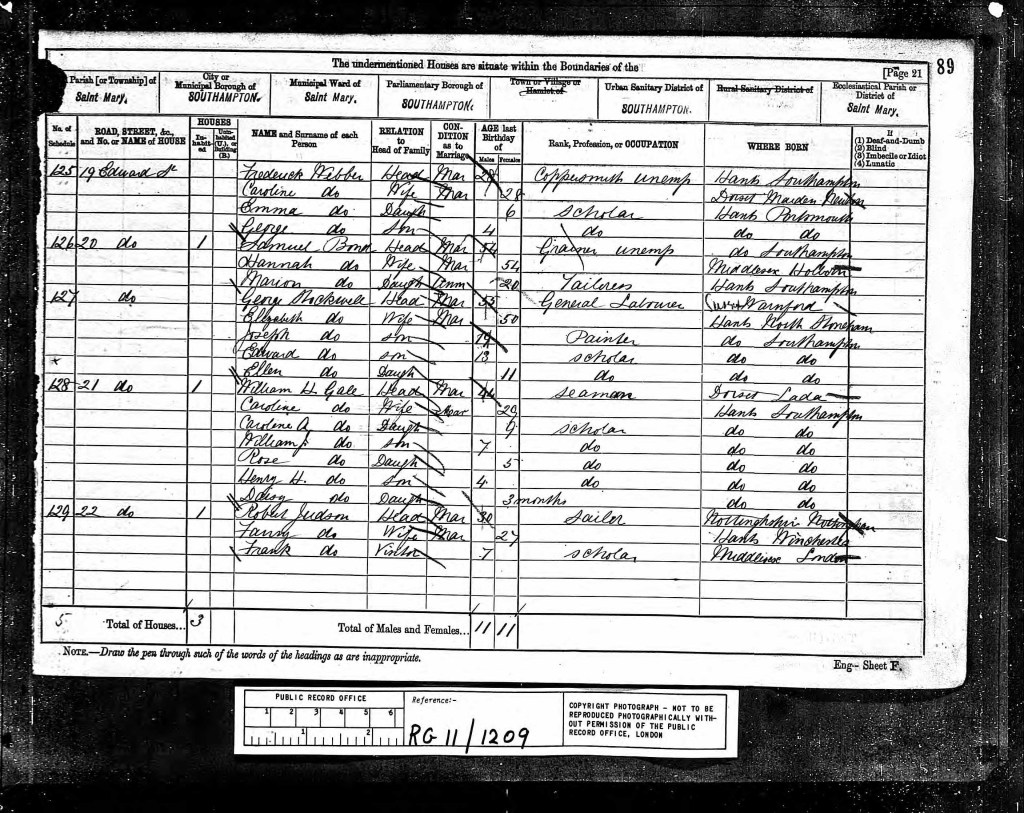

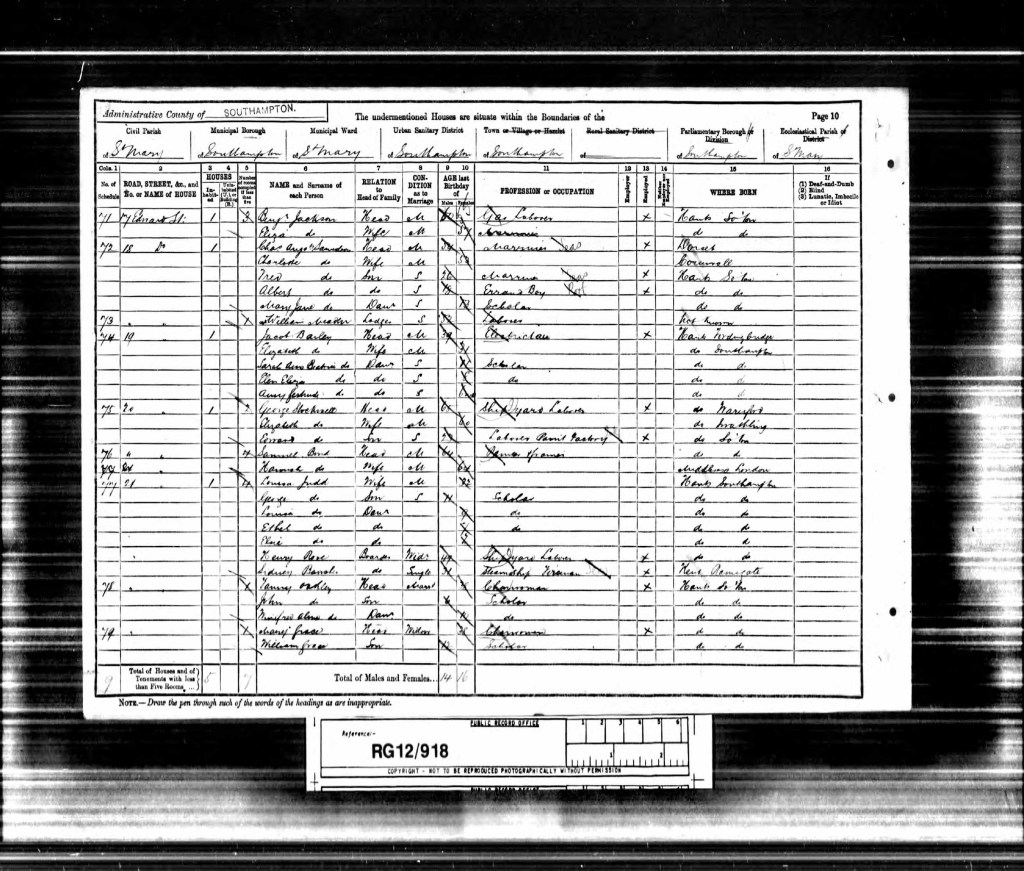

By the evening of Sunday, the 7th day of April 1861, Elizabeth and George Stockwell had settled into their home at Number 3, Godfrey Street, Southampton. With them were their surviving children, Eliza, George, Sarah Ann, and little Elizabeth. Life had not been kind to them, yet they carried on, bound by love and endurance.

Their modest dwelling was crowded, shared with two other families, the Songmans and the Kinnairds. Sixteen souls lived beneath that single roof, packed together in a home that could barely contain the weight of so many lives. The air must have been thick with the sounds of children, the scent of simple meals, and the murmured conversations of weary labourers after a long day’s work.

George, ever the provider, was listed as a labourer, while their son, George, had begun his education, a small glimmer of hope for a future beyond the struggles of the working poor. Despite the hardships they had endured, the heart-wrenching losses, the relentless uncertainty, Elizabeth and George continued forward. They had no choice but to press on, to keep their children safe, to build whatever life they could in a world that had already taken so much from them.

Godfrey Street, once a notable thoroughfare in Southampton, Hampshire, played a significant role in the city's 19th-century urban landscape. Situated in the eastern part of Southampton, the street extended from Marine Parade to Godfrey's Court, an area later occupied by the gasworks in Crabniton.

The street derived its name from a prominent landowner, Mr. Godfrey, whose estate around 1800 encompassed the region stretching from what is now Northam Road down to Marsh Lane. This expanse saw the development of a small village, marking the early growth of the area.

In its heyday, Godfrey Street was characterized by residential and commercial establishments, serving as a hub for the local community. Among its notable landmarks was the Godfrey Inn, a public house that operated until the early 20th century. This inn was part of the portfolio of A. Barlow & Co Ltd, a company that owned several pubs across Southampton and beyond.

The area surrounding Godfrey Street, including Godfrey's Court (also known as Godfrey's Cut or Passage), was known by the early 19th century as Crabniton. This district, located east of Golden Grove, later became the site of the gasworks, indicating the industrial evolution of the locality.

Over time, with urban development and industrial changes, Godfrey Street and its immediate environs underwent significant transformations. The establishment of the gasworks and other industrial facilities led to the restructuring of the area, leading to the disappearance of some of the original street layouts and landmarks.

Godfrey’s Town all but disappeared when the gas company expanded its works at the turn of the 20th century and took over most of the land between Longcroft Street and Princess Street, leaving just a few buildings fronting Marine Parade until they too were built on in the early 1900s.

Godfrey’s Town on the 1846 map shows 15 buildings along Godfrey Street including the Victory public house which was No 1. It was owned by Barlow’s Victoria Brewery and its early landlord was John Powell. The Biffin family were licensees from the 1860s until the late 1880s, after which its name had changed to the Godfrey Inn by the 1890s. Following its name change the pub closed around the turn of the century under the stewardship of Frederick Thomas, its final landlord before the site was taken over by the gas works expansion.

Godfrey Street had a second pub which was the Olive Branch at No 5 where Thomas Cole was landlord in 1871. The Cole family were evident behind the bar until the late 1880s and the pub, owned by the Winchester Brewery, ceased trading in February 1904 and, like its neighbour the Godfrey Inn, was swallowed up by the expansion of the gas works at that time. The map shows Godfrey’s Town in its latter days of 1897.

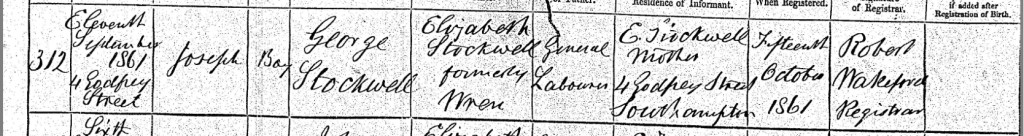

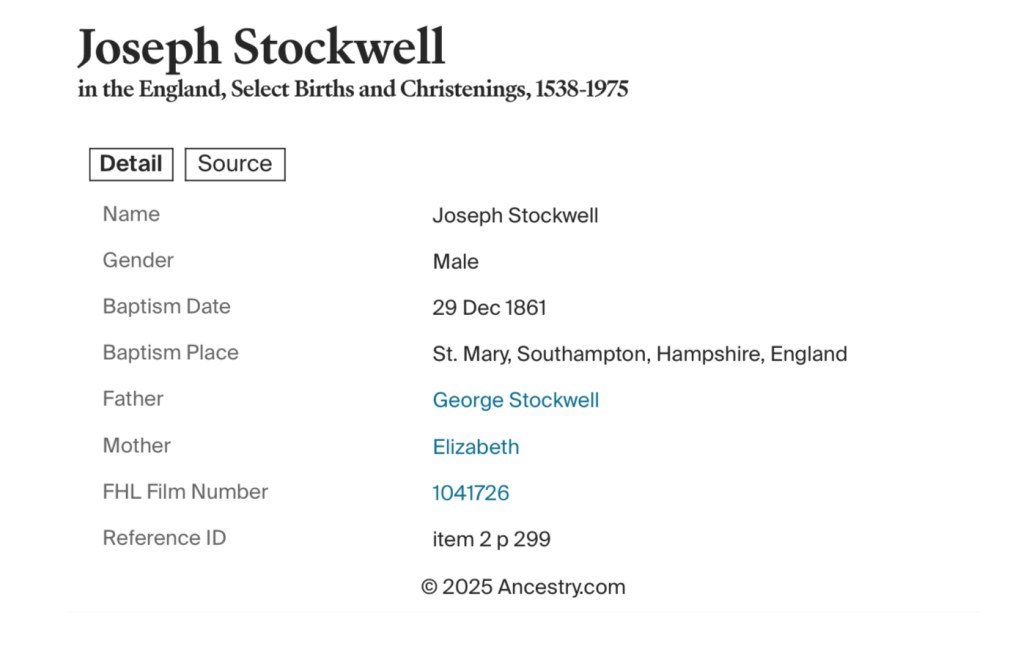

Amidst the struggles of daily life, a new glimmer of hope arrived for Elizabeth and George Stockwell. On Wednesday, the 11th day of September 1861, Elizabeth gave birth to a son, whom they named Joseph, at their home on Number 4, Godfrey Street, Southampton. Another child to love, another chance to rebuild after so much heartbreak.

A month later, on Tuesday, the 15th day of October, Elizabeth made the familiar journey into Southampton to register Joseph’s birth. With the weight of past losses still etched into her soul, she carried her newborn son’s details to the registrar, Robert Wakeford. He carefully inscribed into the register that Joseph, a boy, was the son of George Stockwell, a general labourer, and Elizabeth Stockwell, formerly Wren, of Godfrey Street.

With each child, Elizabeth must have hoped for a future free from sorrow, where she could watch them grow into adulthood. Yet, she knew all too well that life had never made such promises.

On Sunday, the 29th day of December 1861, Elizabeth and George brought their infant son, Joseph Stockwell, to St Mary’s Church, St Mary’s, Southampton, Hampshire, England, to be baptised. Surrounded by their family and community, they stood before the minister as Joseph was welcomed into the church.

The baptism was a moment of faith and tradition, marking the beginning of Joseph’s spiritual journey. Despite the many losses Elizabeth and George had endured, they continued to baptise their children, perhaps holding onto the hope that faith would provide comfort and protection for their growing family.

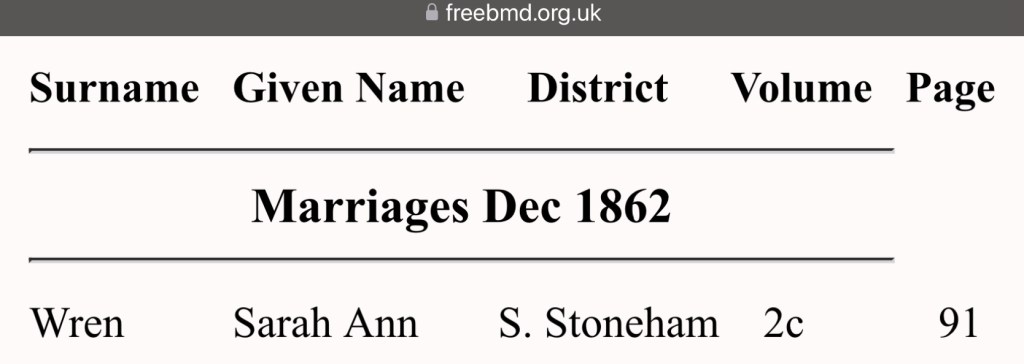

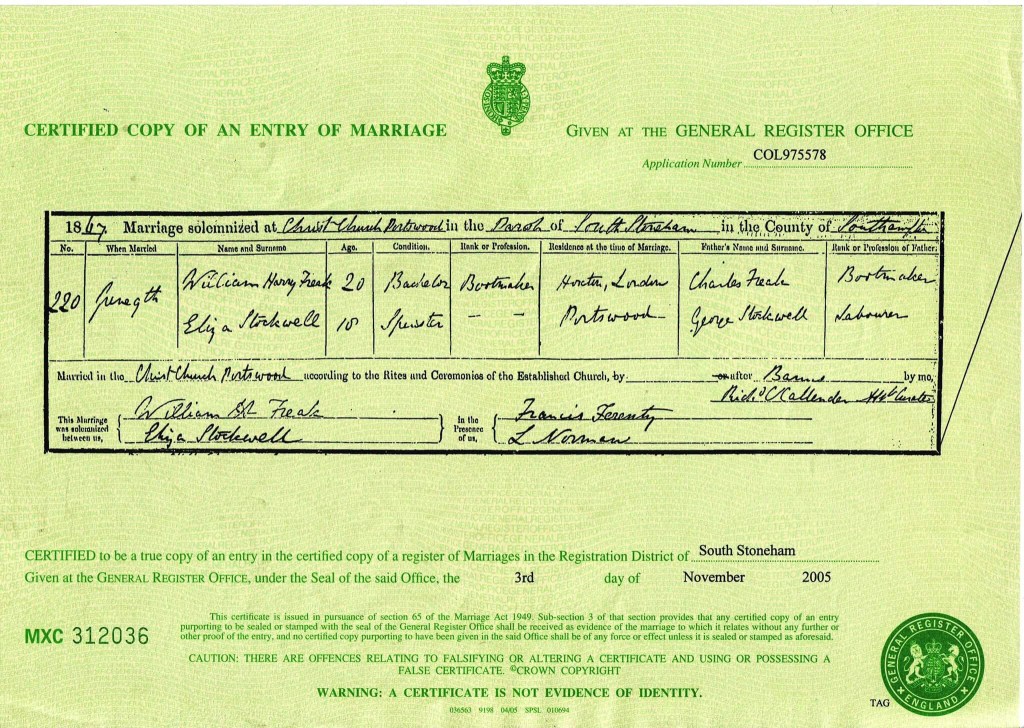

Elizabeth’s younger sister, Sarah Ann Wren, married Francis Ferentz (Farenty) in the district of South Stoneham, Hampshire, during the December quarter of 1862 at just 16 years old. Though the details of their wedding remain undocumented here, their union marked the beginning of a new chapter in Sarah Ann’s life.

For those interested in obtaining an official copy of their marriage certificate, the following GRO reference can be used:

GRO Ref - Marriages, Dec 1862, Wren, Sarah Ann, Farenty, Francis, S. Stoneham, Volume 2c, Page 91.

Sarah Ann’s marriage was another milestone in the Wren family's journey, as each sibling began forging their own path amid the hardships and joys of 19th-century life.

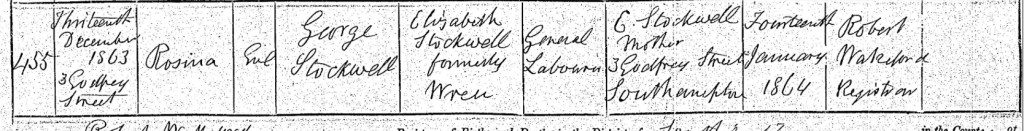

Elizabeth and George welcomed their daughter, Rosina Stockwell, into the world on Sunday, the 13th day of December 1863, at their family home, Number 3, Godfrey Street, Southampton, Hampshire, England.

A month later, on Thursday, the 14th day of January 1864, Elizabeth made the journey into Southampton to officially register Rosina’s birth. The registrar, Robert Wakeford, documented in the birth register that Rosina, a girl, was the daughter of George Stockwell, a general labourer, and Elizabeth Stockwell, formerly Wren, residing at Number 3, Godfrey Street, Southampton.

Rosina’s arrival brought new hope to the family, but with their history of loss, Elizabeth must have held her newborn daughter close, cherishing every precious moment.

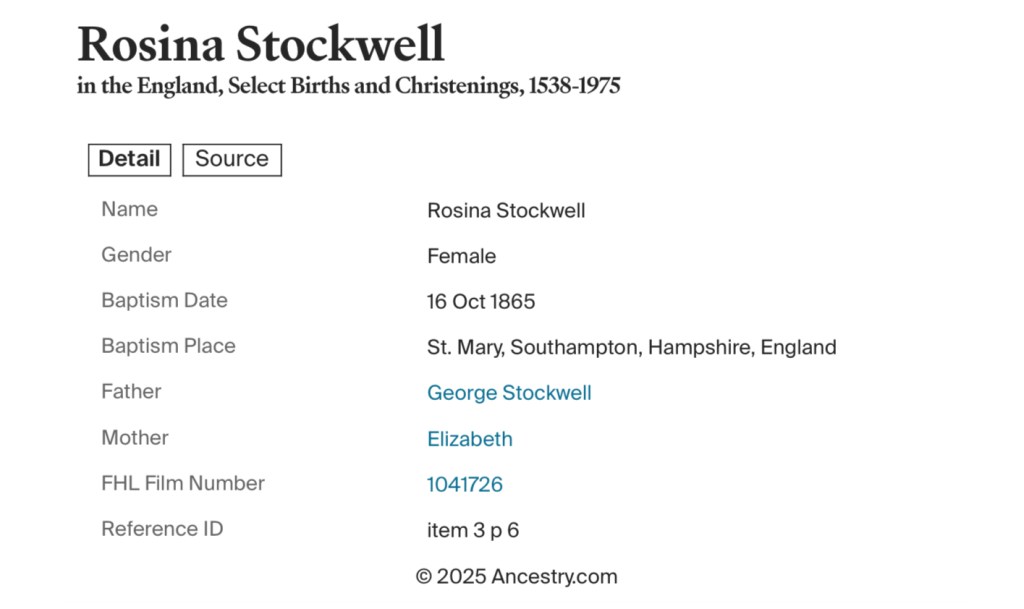

On Monday, the 16th day of October 1865, Elizabeth and George carried their beloved daughter, Rosina Stockwell, to Saint Mary’s Church in Southampton, Hampshire, England, to be baptised. The small church, filled with the echoes of whispered prayers and the flickering glow of candlelight, bore witness to yet another chapter in their lives.

As they stood before the minister, holding their precious child, they must have felt the weight of both joy and sorrow, the joy of welcoming Rosina into the faith, yet the lingering sorrow of all the children they had loved and lost before her. Elizabeth, who had endured so much heartache, might have whispered silent prayers for this daughter, hoping she would grow strong and healthy, spared from the cruel fate that had taken so many of her siblings.

The minister’s voice filled the sacred space as he carefully recorded Rosina’s details in the baptism register, a moment that would forever bind her to the church and community. George, a hardworking man, stood beside his wife, their hands perhaps clasped together, sharing an unspoken understanding of the trials they had faced.

Despite their hardships, this day was one of hope, of faith, and of an unwavering love for their children. As the ceremony concluded, Elizabeth may have held Rosina just a little tighter, pressing a gentle kiss to her tiny forehead, silently vowing to protect and cherish her for as long as life would allow.

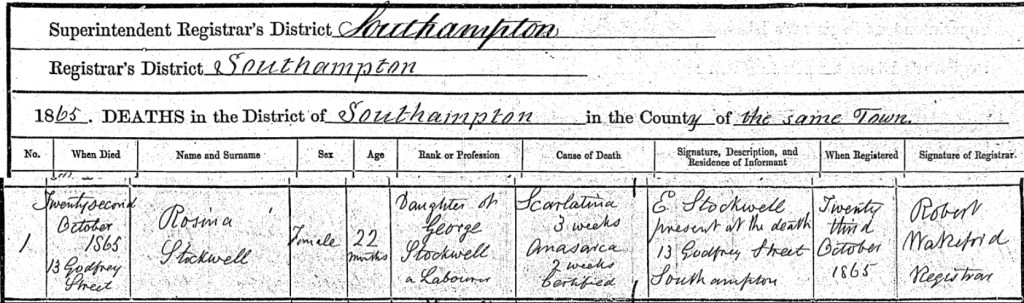

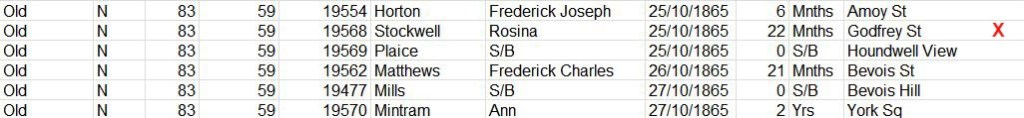

On Sunday, the 22nd day of October 1865, Elizabeth’s world was once again shattered as she held her 22-month-old daughter, Rosina Stockwell, in her arms, watching helplessly as life slipped away. Their home at Number 13, Godfrey Street, Southampton, had been filled with the echoes of a child’s laughter, the soft pitter-patter of tiny feet, and the warmth of a mother’s love. Now, it was silent, overtaken by the sorrow of yet another unbearable loss.

For three weeks, little Rosina had suffered from the cruel grip of scarlatina, her tiny body weakened further by anasaica in the final two weeks. Elizabeth had done everything she could, comforting her daughter through restless nights, cooling her fevered skin with trembling hands, whispering soft words of love and reassurance. But no amount of love or care could stop the inevitable. And so, on that fateful Sunday, Elizabeth was left to cradle her child’s still form, her tears falling onto Rosina’s soft curls as the weight of grief settled heavily on her heart once more.

Despite the agony that threatened to consume her, Elizabeth found the strength to do what she had done far too many times before, she made the sorrowful journey to the registrar’s office the very next day. With a heart laden with grief, she stood before Robert Wakeford, the familiar registrar who had recorded both the joyous arrivals and the devastating departures of her children. With a shaking hand, she gave Rosina’s details, her voice barely above a whisper as she confirmed the cause of death. The words scrawled into the register, Scarlatina, three weeks, Anasarca, two weeks, felt like a cruel finality to a life that had barely begun.

As Elizabeth left the registrar’s office, the cool autumn air wrapped around her, but it could do nothing to ease the deep ache inside her chest. She had buried too many of her children, and with every loss, a piece of her own soul seemed to fade. Now, she faced yet another painful farewell, another tiny grave to visit, and another cherished name etched into her heart forever.

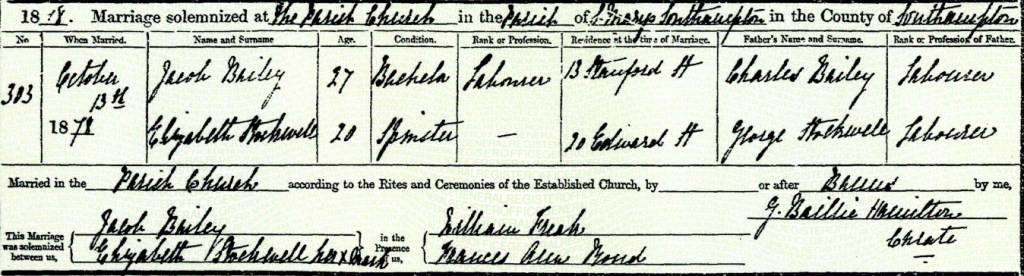

Scarlatina, more commonly known as scarlet fever, is an infectious disease caused by the bacterium *Streptococcus pyogenes*, which also causes strep throat. It primarily affects children and was once a significant cause of illness and death, particularly in the 19th and early 20th centuries, before the advent of antibiotics. The disease presents with a sore throat, fever, and a distinctive red rash that gives it its name. The rash, which typically starts on the chest and spreads across the body, feels like sandpaper and is often accompanied by a flushed appearance of the face with a pale ring around the mouth. The tongue may also become swollen and take on a "strawberry" appearance due to inflamed red papillae.