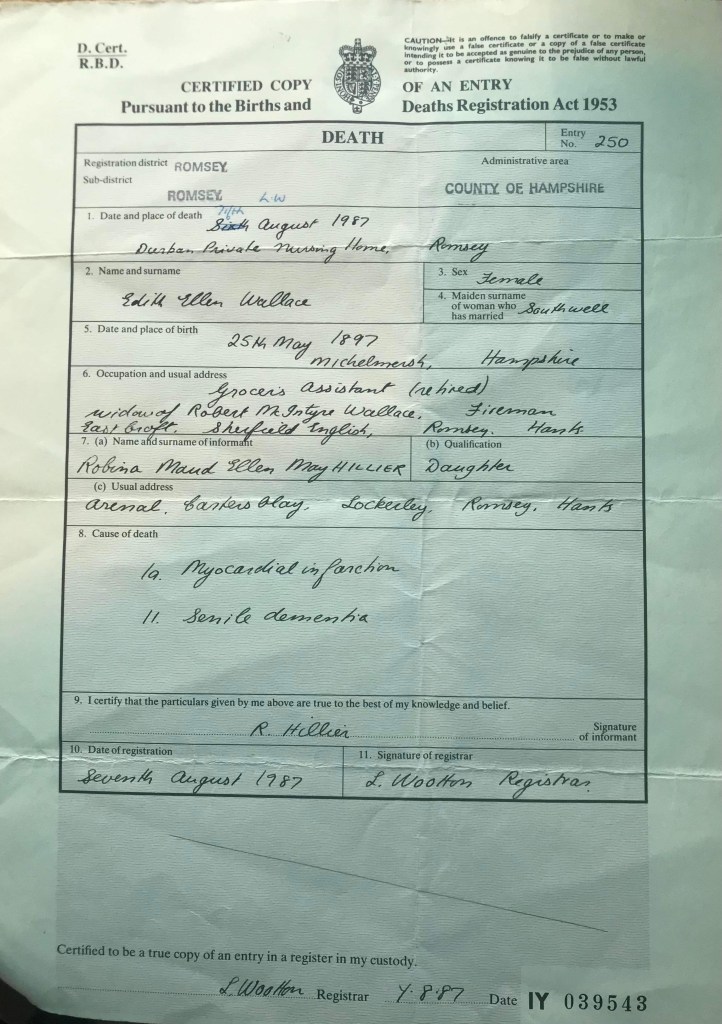

In the quiet corners of history, amid the sepia-toned photographs, delicate handwritten letters, and carefully preserved records, lie stories waiting to be told. This is the tale of Edith Ellen Southwell, a woman whose life spanned nine decades, from the final years of the Victorian era to the dawn of the modern world. Born in 1897, she lived through two world wars, societal transformations, and the ever-changing landscapes of family, love, and duty.

Unlike the famous names etched into history books, Edith’s story is not one of grandeur or renown. Instead, it is a story of quiet strength, perseverance, and the everyday moments that make up a life well-lived. Through documentation, census records, birth, marriage and death certificates, and other remnants of her past, we will piece together the world she inhabited, the people she loved, and the trials and triumphs she faced.

Who was Edith Ellen Southwell beyond the ink on these pages? What dreams did she hold close to her heart? What challenges shaped her into the woman she became? By following the footprints she left behind in the form of documentation, we will attempt to bridge the gap between past and present, bringing her story to life once more.

This is more than a historical account; it is an act of remembrance. Through this blog, Edith’s name and legacy will not fade into obscurity but will live on, her story woven into the fabric of time. Join me as we journey through the life of Edith Ellen Southwell, one document at a time.

So without further ado I give you,

The Life Of

Edith Ellen Southwell

1897–1987

Through Documentation.

Welcome back to the year 1897, Wellow, Hampshire, England. The air is crisp with the scent of the English countryside, where rolling fields stretch under a sky often softened by a gentle mist. Life moves at a pace dictated by the land and the seasons, and the village of Wellow, nestled in the heart of Hampshire, carries the quiet hum of a bygone era. The year is 1897, and Britain is at the height of its imperial power, celebrating the Diamond Jubilee of Queen Victoria, who has now reigned for an astonishing sixty years. Her presence looms large over the nation, a steadfast symbol of continuity in an age of immense change.

The Prime Minister, Lord Salisbury, leads the Conservative government, presiding over a Parliament that represents a deeply stratified society. Though reform has crept into politics, giving more men the right to vote, Britain remains a place where privilege is closely guarded by the upper classes. The aristocracy and wealthy landowners still dominate, while the working class and the poor endure long hours, meager wages, and the constant threat of illness or unemployment.

A stroll through the village or nearby towns in 1897 reveals stark differences between the classes. The wealthy glide through the streets in elegant dresses of high-necked lace and layered skirts, their waists cinched tightly by corsets, while men wear tailored frock coats, waistcoats, and bowler hats. For the working-class women of Wellow, practicality prevails, long woolen skirts, simple blouses, and shawls wrapped tightly against the chill. Men, whether they toil in the fields or labor in towns, wear sturdy trousers, shirts, and flat caps. Footwear, or the lack of it, often marks one's standing; while the well-off wear polished leather boots, many among the poor go barefoot, even in colder months.

The streets are alive with the rhythmic clatter of horseshoes on cobblestones. The horse and cart remain the backbone of transportation, though in larger towns and cities, the wealthier class is beginning to take an interest in the new motor cars, cumbersome and still unreliable. Railways connect the nation, making travel more accessible than ever before, and even the humble bicycle is gaining popularity among the middle class.

Coal is the lifeblood of the era, fueling the trains that carve through the countryside and feeding the fires that heat homes and power industry. Electricity is slowly making its way into urban centers, but in rural Hampshire, gas lighting remains a luxury, and most homes still rely on oil lamps or candles to chase away the evening darkness.

As night falls over Wellow, the streets are bathed in a dim, flickering glow from gas lamps, casting long shadows. In homes, fireplaces provide both warmth and light, their crackling fires the heart of the household. The smell of burning coal lingers in the air, mingling with the earthy scent of damp soil and the distant aroma of baking bread. Life is dictated by the rise and fall of the sun, with early mornings and early nights, particularly in winter.

Sanitation remains a significant concern, especially for the poor. Many rural homes still rely on outdoor privies, and clean water is not always guaranteed. In the cities, slums overflow with waste, and diseases like typhoid and tuberculosis spread quickly in overcrowded conditions. The wealthy, however, enjoy the benefits of newly developed plumbing, with hot running water and sanitary facilities becoming increasingly common in grander homes.

Food is simple but hearty. In a village like Wellow, most families rely on homegrown vegetables, fresh milk, eggs, and locally butchered meat. Bread, butter, and cheese are staples, and the weekly market provides access to seasonal fruit and salted fish. For the rich, dining is an elaborate affair, with multiple courses, fine wines, and delicacies imported from across the British Empire. Tea is already a national institution, and sugar, though expensive, is a sought-after luxury.

Life in 1897 is not without its pleasures. Church fairs, country dances, and the occasional traveling show bring excitement to village life. The phonograph is making its way into wealthier homes, allowing people to hear music from afar, while newspapers spread the latest gossip, both local and national. Theatres in nearby towns showcase the grand performances of the day, and for those who can afford it, the pleasure of a day trip to the seaside is a cherished escape.

This year, the grand event on everyone’s lips is the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee. From the grand streets of London to the smallest hamlets, celebrations abound. Bunting decorates the homes of the patriotic, and even in a village like Wellow, there is talk of feasts and festivities to honor the monarch who has watched over Britain for six decades.

To be born into wealth in 1897 is to live a life of leisure, fine dining, and grand homes staffed by servants who see to your every need. Education is the domain of the privileged, with the best schools reserved for the children of the aristocracy. For the working class, life is a daily struggle to put food on the table. Many men work long hours in agriculture or industry, while women take in laundry, sew, or work as domestic servants. The poor fare worst of all, living in crowded conditions with little hope of social mobility. Charitable organizations provide some relief, but the rigid class structure remains firmly in place.

The 1891 census, the most recent at this time, revealed the steady growth of Britain’s population, reflecting the rise of industry and urbanization. The next census, in 1901, will document the shifts taking place at the turn of the century. Meanwhile, across the world, the British Empire remains vast and powerful, but tensions are beginning to simmer in its far-flung territories. At home, the suffrage movement is gaining traction, though women are still denied the right to vote.

As 1897 draws to a close, Britain stands at the crossroads of tradition and change. The world is moving forward, and soon, a new century will dawn, bringing with it the promise of progress and the uncertainty of the unknown. But for now, in Wellow, life carries on much as it always has, rooted in the rhythms of the land, the warmth of the hearth, and the ever-turning wheel of history.

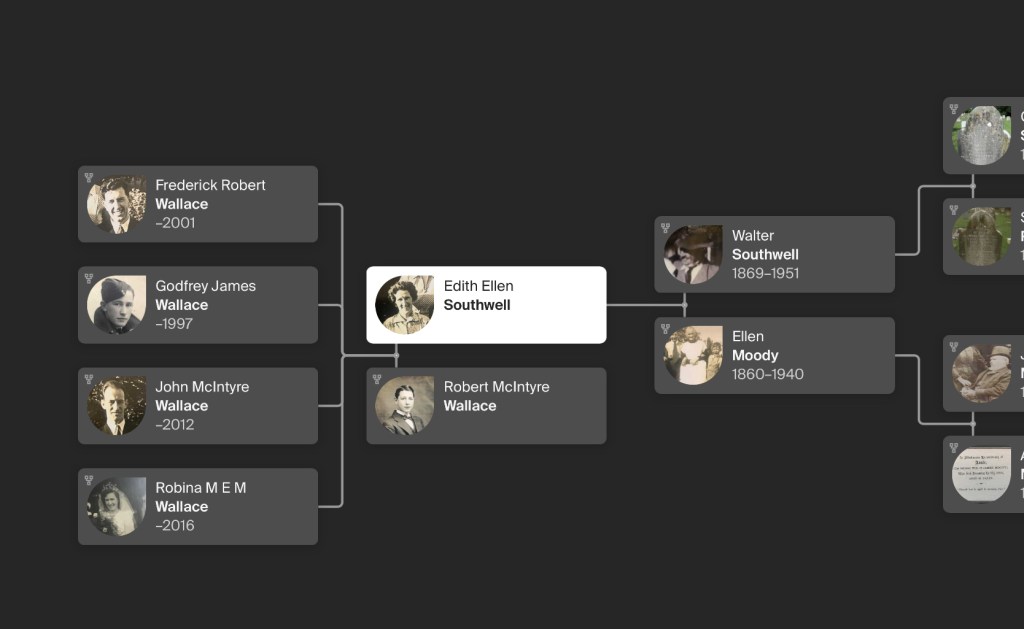

In the quiet village of East Wellow, surrounded by rolling fields and the steady rhythm of rural life, Walter Southwell and his wife Ellen built a home and a family. Walter, a hardworking farmer, spent his days tending the land, while Ellen cared for their growing brood, Alice Annie, born in 1889, Emily Kate in 1892, and little George, just two years old. Their cottage was filled with the sounds of childhood, the crackling warmth of the hearth, and the daily routines of a farming family in Hampshire.

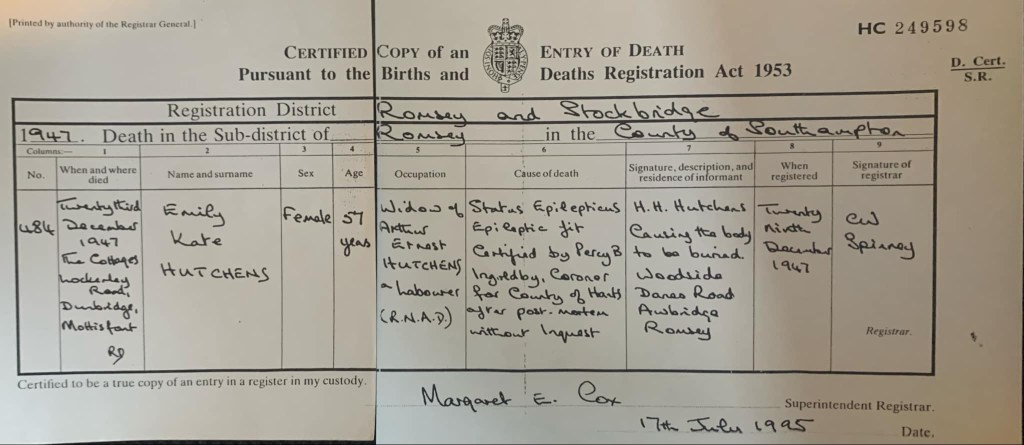

As spring turned to summer in 1897, Ellen’s pregnancy neared its end. The days were long and warm, the scent of earth and hay drifting through open windows. On Tuesday, the 25th of May, after hours of labor in the familiar surroundings of their home, Ellen brought a new life into the world. A daughter. Her first cries breaking the quiet of the day. They named her Edith Ellen Southwell, a name that carried the weight of family and tradition.

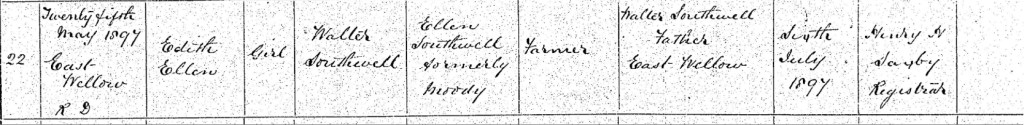

Life on the farm allowed little time for pause. There were mouths to feed, animals to tend, and the ceaseless work of the land to manage. Nearly six weeks after Edith’s birth, on Tuesday, the 6th of July, Walter made the four-mile journey to Romsey Town to officially register his daughter. It was a familiar route, one he had likely taken many times before, passing through winding country roads under the summer sky.

At the Romsey registry office, Henry H. Saxby, the registrar in attendance, carefully recorded the details. Edith Ellen Southwell, a girl, born on the 25th of May 1897 in East Wellow. Her father, Walter Southwell, a farmer. Her mother, Ellen Southwell, formerly Moody. Each word inscribed in ink, a simple but significant act, securing Edith’s place in the world.

With the birth now officially recorded, Walter returned home to his wife and children, back to the familiar sights and sounds of their little corner of Hampshire. Edith, oblivious to the journey her father had made that day, lay safely in her mother’s arms, a new life just beginning in a world that was ever-changing yet, in many ways, remained the same.

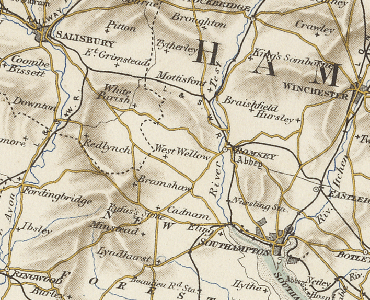

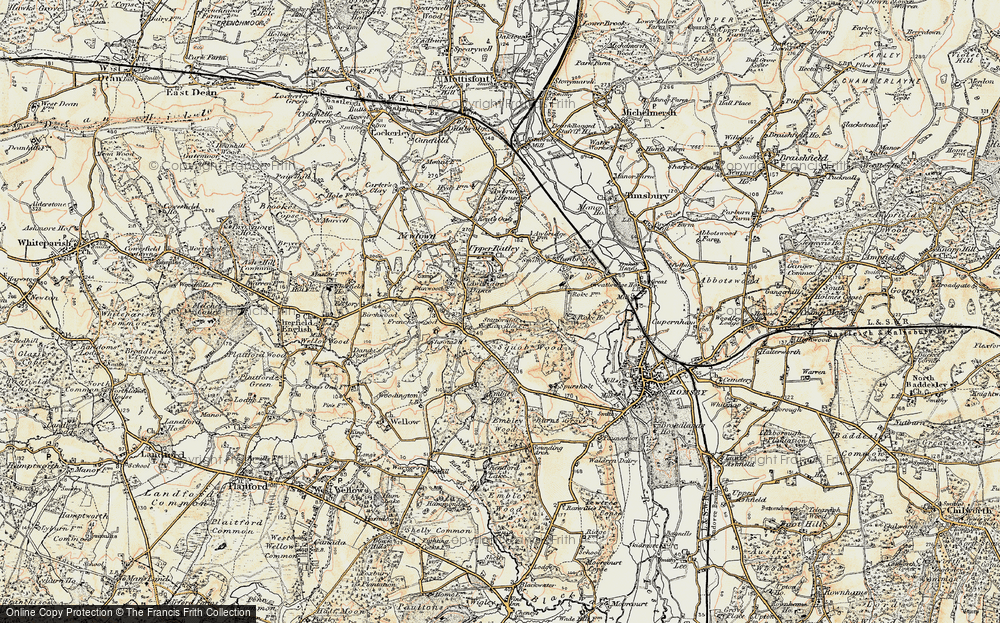

Wellow, Hampshire, is a village rich in history, nestled in the gentle countryside of southern England. Divided into East and West Wellow, the parish has long been shaped by the ebb and flow of rural life, where generations of families have worked the land, tended to livestock, and lived by the changing seasons. The village sits just a few miles west of Romsey, surrounded by rolling fields, ancient woodlands, and winding lanes that have carried the footsteps of farmers, traders, and travelers for centuries.

East Wellow, the quieter half of the parish, has always been deeply rooted in agriculture. In the late 19th century, it was a community of farmers and laborers, where small cottages and farmsteads dotted the landscape. The land itself was fertile, providing ample opportunity for farming, which had been the backbone of the village economy for centuries. Families like the Southwells worked tirelessly to maintain their livelihoods, rising with the sun to care for crops and animals, their days dictated by the rhythms of nature.

Wellow’s history stretches back to the medieval period and beyond. The village is mentioned in the Domesday Book of 1086, where it was recorded as “Welga,” a small but established settlement under the ownership of prominent Norman lords. Over the centuries, the land passed through the hands of various noble families, but life for the common villagers remained largely unchanged, centered on agriculture, local trade, and the enduring presence of the church.

One of Wellow’s most famous historical connections is with Florence Nightingale, the pioneering nurse who revolutionized modern healthcare. Although she was born in Florence, Italy, her family home was Embley Park, a grand estate near East Wellow. The Nightingales were well-respected figures in the community, known for their philanthropy and influence. Florence herself is buried in St. Margaret’s Churchyard in East Wellow, a quiet resting place that draws visitors from far and wide to pay their respects to the woman who dedicated her life to the care of others.

St. Margaret’s Church, standing in East Wellow since Norman times, is the heart of the village’s spiritual life. Built in the 12th century, its sturdy flint and stone walls have witnessed countless baptisms, marriages, and funerals. The churchyard, shaded by ancient yew trees, is a testament to the generations who have lived and died in this small but significant corner of England.

By the late 19th century, Wellow was a community of close-knit families, many of whom had lived there for generations. Life was simple but hardworking, with most people employed in farming, milling, or local trades. The village lanes were unpaved and muddy in winter, but in summer, they were bordered by hedgerows bursting with wildflowers. The nearest market town was Romsey, where villagers traveled to buy and sell goods, register births and marriages, and gather for fairs and social events.

Despite the quiet charm of Wellow, the late Victorian era brought changes, as improvements in transport and industry began to filter into rural life. The expansion of the railways made travel easier, and though Wellow itself remained relatively untouched by industrialization, the outside world was creeping closer. Steam-powered machinery was becoming more common on farms, and the divide between traditional ways and modern advancements was slowly growing.

Through all of this, East Wellow remained a village of hard work and resilience, where families like the Southwells carried on their daily lives, tending the land, raising children, and leaving behind their own small but important marks on history.

The warm June air drifted through the village of Wellow as Walter and Ellen Southwell made their way to St. Margaret’s Church, cradling their newborn daughter, Edith Ellen. It was Sunday, the 20th day of June 1897, and the bells of the ancient Norman church rang out, calling the faithful to worship. Dressed in their best, the Southwell family stepped into the cool, stone-walled sanctuary where generations before them had stood, marking life’s most sacred moments.

St. Margaret’s Church, with its weathered flint walls and arched windows, had stood in East Wellow for centuries, a steadfast presence in the lives of the village’s families. Inside, the flickering candlelight cast soft shadows across the wooden pews, the scent of aged hymnals and fresh flowers mingling in the air.

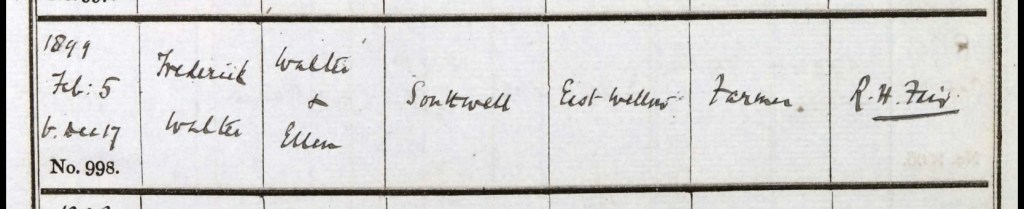

As the congregation gathered, R. H. Fair, the officiating minister, welcomed the Southwells to the font. Ellen held Edith close, her tiny body possibly wrapped in the folds of a delicate christening gown, the fabric worn smooth from years of family tradition. Walter stood beside her, his presence solid and steady, their older children watching with quiet curiosity.

The ceremony would have simple yet profound. With a steady hand, R. H. Fair took the infant and poured the cool water of baptism over her forehead, reciting the sacred words that welcomed Edith Ellen into the church. In that moment, she was not just their daughter, she was now part of something greater, bound to the faith and traditions that had guided her family for generations.

As the final prayer was spoken, Walter and Ellen knew that their daughter’s name was now recorded in the parish register, ink on parchment sealing this moment in time. Outside, as they stepped back into the warm June sunlight, the life of Edith Ellen Southwell had truly begun, her place in the world officially blessed and acknowledged.

St. Margaret’s Church in Wellow, Hampshire, is a place of deep historical and spiritual significance, standing quietly among the rolling fields and ancient woodlands of the Hampshire countryside. With its weathered stone walls and modest yet enduring presence, the church has been a cornerstone of the village for centuries, witnessing the lives of generations who have passed through its arched doorway to mark their most sacred moments, baptisms, marriages, and farewells.

The history of St. Margaret’s stretches back to the 12th century, when it was first built in the Norman style, a time when churches were not only places of worship but also the heart of village life. Its flint and stone construction, simple yet sturdy, reflects the medieval craftsmanship of rural England. Though small in scale, the church has always stood as a testament to faith and tradition, its bell calling the villagers of Wellow to prayer through the centuries.

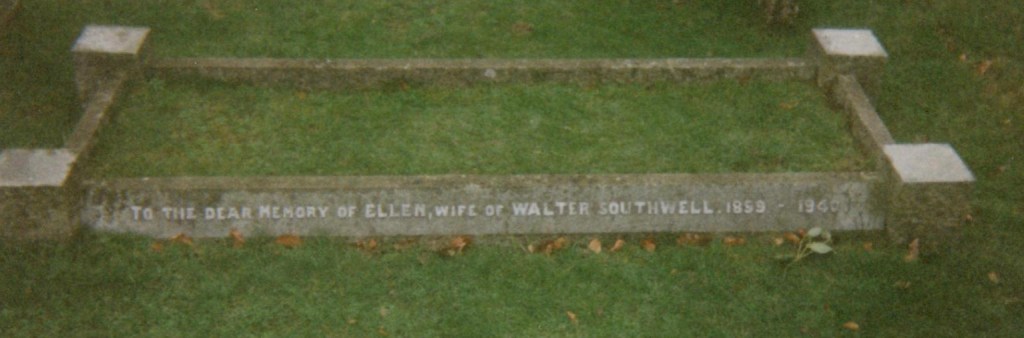

The churchyard surrounding St. Margaret’s is filled with weathered headstones, some standing upright, others leaning with the weight of time, each marking the resting place of those who once lived in this quiet corner of Hampshire. One of the most famous graves belongs to Florence Nightingale, the pioneering nurse whose reforms revolutionized healthcare. Though she was born in Florence, Italy, her family home was Embley Park, near Wellow, and it was here, among the familiar fields and countryside, that she chose to be laid to rest in 1910. Her grave is simple, reflecting her humility, and it draws visitors from across the world who come to pay their respects.

Throughout the centuries, St. Margaret’s has remained a place of solace and continuity. The wooden pews have borne witness to whispered prayers and joyful hymns, the stone font has welcomed countless infants into the church through baptism, and the pulpit has echoed with the voices of clergymen delivering their sermons. The church has seen times of great change, through the Reformation, the English Civil War, and the upheavals of the modern age, but it has always remained steadfast, its doors open to those seeking comfort, faith, or a quiet moment of reflection.

By the late 19th century, when Walter and Ellen Southwell brought their children to be baptised, the church was much as it had always been, modest yet central to the life of the village. The congregation was made up of farmers, laborers, and local families who gathered each Sunday, dressed in their best, to take part in the service. The seasons of the church year, from Christmas to Easter, shaped the rhythms of life in Wellow, just as the passing of the seasons shaped the work on the land.

Today, St. Margaret’s Church remains a cherished landmark in Wellow, a link between past and present. It continues to serve as a place of worship and remembrance, its ancient walls holding the stories of those who have walked its stone floors for more than 800 years. The village may have changed, but within the quiet churchyard, among the yew trees and timeworn gravestones, history lingers, and the legacy of St. Margaret’s endures.

As the chill of winter settled over the Hampshire countryside, the Southwell family prepared to welcome another child into their home. The fields of East Wellow lay quiet beneath the pale December sky, the frost crisp on the hedgerows, as Ellen Southwell laboured in their home at Shootash.

On Saturday, the 17th day of December 1898, cries of new life filled the farmhouse as she gave birth to a healthy baby boy. Wrapped in the warmth of his mother’s arms, the child was named Frederick Walter Southwell, a name that carried both family honor and tradition. In the days that followed, Ellen recovered in the comfort of home, surrounded by the gentle chaos of her growing family. Little Edith, just over a year old, watched with wide eyes as her tiny brother nestled in his mother’s embrace, while Alice, Emily, and George eagerly playing and possibly taking turns peering at the newest addition.

Life on the farm pressed forward as always. Walter had work to tend to, the demands of the land never ceasing, even in the depths of winter. The birth of a son was a moment of quiet pride, a future helping hand, someone to carry on the family’s name and the legacy of hard work that had shaped their lives. But first, there was the matter of official recognition.

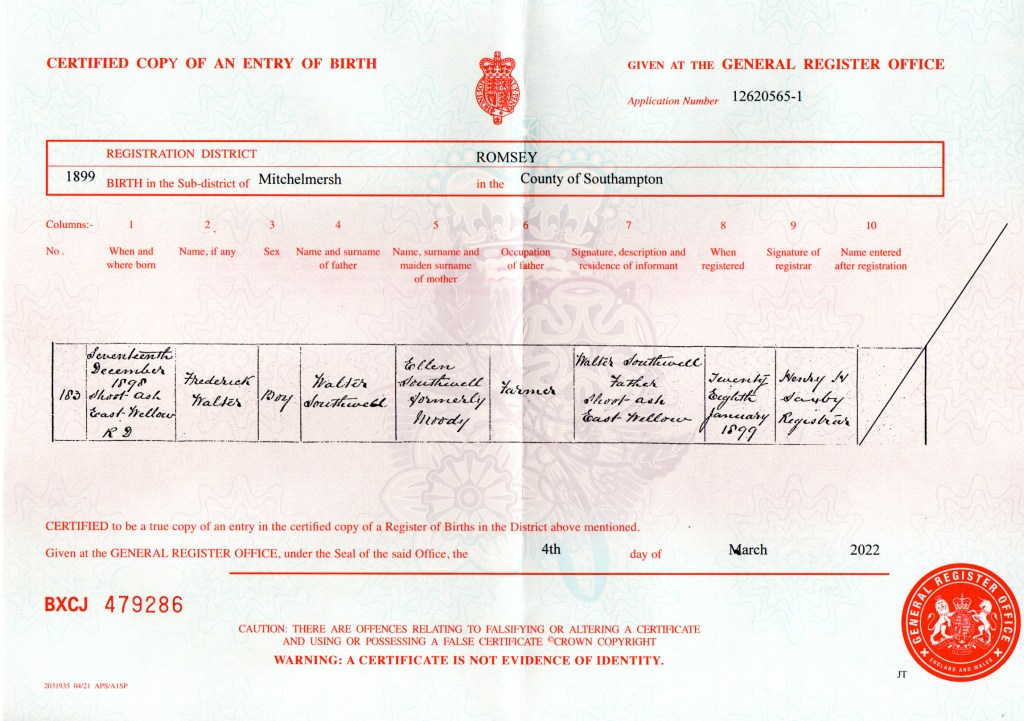

Six weeks later, on Saturday, the 28th of January 1899, Walter set off on the familiar journey to Romsey Market Town, wrapped in his thick coat against the crisp winter air. The four-mile trek took him along country lanes, past the bare trees that lined the countryside, his thoughts likely on the responsibilities of raising another child. At the Romsey registry office, he once again stood before Henry H. Saxby, the registrar who had recorded Edith’s birth only a year and a half earlier.

With careful strokes of the pen, Saxby entered the details into the official record. Frederick Walter Southwell, a boy, born on the 17th of December 1898 at Shootash, East Wellow, Hampshire. Son of Walter Southwell, a farmer, and Ellen Southwell, formerly Moody, both residing at Shootash, East Wellow. The ink dried, sealing another chapter of the Southwell family’s story.

As Walter made his way home, Ellen waited with their children, the warmth of the hearth welcoming him back from his journey. Frederick, blissfully unaware of the significance of the day, slept peacefully in the crook of his mother’s arm, another cherished soul within the walls of their family home.

Shootash, near Romsey in Hampshire, is a small hamlet with a deep-rooted history in rural England. Nestled between the villages of Wellow and Romsey, it has long been a quiet and unassuming place, shaped by the rhythm of agricultural life and the passage of time. The land here is fertile and has been farmed for centuries, with families working the fields, raising livestock, and living off the rich Hampshire soil.

The name Shootash, sometimes written as Shoot Ash, hints at its past, possibly derived from old English words relating to wooded areas or hunting grounds. Hampshire itself has long been a county of vast forests, open fields, and winding country lanes, and Shootash would have been no exception. The nearby New Forest, once a royal hunting ground established by William the Conqueror, influenced the surrounding areas, and the people of Shootash would have been accustomed to living alongside both farmland and stretches of woodland.

During the medieval period, the hamlet was likely a scattering of small farmsteads and cottages, each with its own patch of land. Romsey, just a few miles away, was a bustling market town, and the people of Shootash would have relied on it for trade, church services, and supplies. The imposing Romsey Abbey, a Norman-era structure, stood as a spiritual and cultural landmark for the surrounding villages, including Shootash.

By the 18th and 19th centuries, Shootash had become a well-established rural community, with farming at its heart. The Industrial Revolution brought change to much of England, but places like Shootash remained largely untouched by factories and urbanization. Instead, life here continued much as it had for generations, families worked the land, tending to crops and livestock, and making the occasional journey into Romsey or further afield for goods and services.

By the late 19th century, when Walter and Ellen Southwell made their home in Shootash, the area was home to a mix of farmers, laborers, and tradespeople. The Southwells, like many families in the area, depended on the land for their livelihood. The landscape would have been dotted with thatched cottages, sturdy brick farmhouses, and fields lined with hedgerows. Horses were still the primary means of transport, and the nearest railway station in Romsey provided a connection to the wider world for those who needed it.

The seasons dictated life in Shootash. Spring and summer were times of planting and harvesting, while autumn brought the gathering of crops and preparation for the colder months. Winters were often harsh, with roads turning to deep mud and frost covering the fields, but the community was resilient. Families helped one another, and the local church played an important role in both spiritual and social life.

Shootash remained a quiet, agricultural hamlet well into the 20th century, retaining its rural charm even as modernity slowly crept in. Today, it still carries echoes of its past, with its country lanes, historic buildings, and a landscape that has been shaped by centuries of farming and tradition. Though small and often overshadowed by larger towns and villages, Shootash holds a place in Hampshire’s history as a steadfast, unchanging corner of England, where families like the Southwells lived, worked, and left their mark.

Shootash, 1897-1909

The winter air was crisp as Walter and Ellen Southwell made their way to St. Margaret’s Church on Sunday, the 5th day of February 1899, carrying their infant son, Frederick Walter, to be baptised. The narrow lanes of East Wellow, edged with bare trees and frost-covered hedgerows, were filled with the sound of horse-drawn carts and the chatter of villagers making their way to the service.

Inside the ancient walls of St. Margaret’s, the glow of candlelight flickered against the stone, casting long shadows across the pews. The scent of burning wax and damp wood filled the air, mingling with the familiar warmth of gathered families. The church, standing since Norman times, had witnessed generations of baptisms, marriages, and farewells, and now it would welcome another soul into its fold.

Walter and Ellen stood solemnly at the font, their children gathered nearby, Edith, still too young to understand the significance of the moment. The minister, R. H. Fair, his voice calm and measured, spoke the sacred words, blessing the child in the name of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit. The cool water of baptism was poured over Frederick’s forehead, a symbolic cleansing, a moment of welcome into both faith and community.

As the final prayers were spoken, the name Frederick Walter Southwell was entered into the church register, ink pressed onto parchment, marking this moment in time. Another milestone in the Southwell family's life, another thread woven into the history of East Wellow.

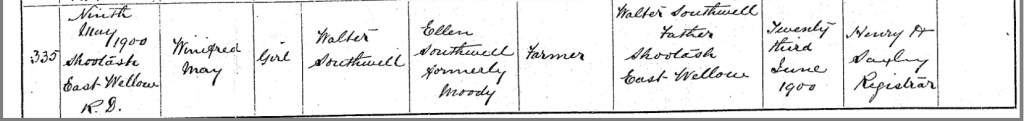

As spring blossomed across the Hampshire countryside, the Southwell family once again welcomed new life into their home. On Wednesday, the 9th day of May 1900, amid the familiar surroundings of Shootash, East Wellow, Ellen Southwell gave birth to a baby girl. The warmth of early May settled over the farm, the hedgerows bursting into fresh green, as little Winifred May Southwell took her first breaths in the world.

With each birth, the Southwell household grew livelier. Alice, Emily, George, Edith, and Frederick were already part of the close-knit family, and now another sister was added to their number. Ellen, experienced in motherhood, cradled her newborn daughter, tending to her while managing the daily rhythms of a busy farm household. The days were filled with the sounds of children’s laughter, the clatter of work in the yard, and the gentle lull of the countryside beyond their door.

Walter, proud yet ever-practical, knew his duty as head of the household. In keeping with the law, he made the journey to Romsey Market Town on Saturday, the 23rd day of June 1900, to officially register his daughter’s birth. It was a route he had taken before, through the winding country lanes, past the fields and farmsteads that made up their world. Arriving in Romsey, he stepped into the registry office, where Henry H. Saxby, the familiar registrar, recorded the details in his steady hand.

Winifred May Southwell, a girl, born on the 9th of May 1900 at Shootash, East Wellow, Hampshire, England. Daughter of Walter Southwell, a farmer, and Ellen Southwell, formerly Moody, both of Shootash, East Wellow. Another name added to the official records, another branch growing on the Southwell family tree.

As Walter made his way home, the summer air surely hung warm and still, the scent of earth and hay drifting through the lanes. By evening, he would be back at the farmhouse, where Ellen would be rocking Winifred gently in her arms, the soft hum of a lullaby settling her to sleep. Their family, rooted in the soil of East Wellow, had grown once more, another life beginning its journey within the heart of home.

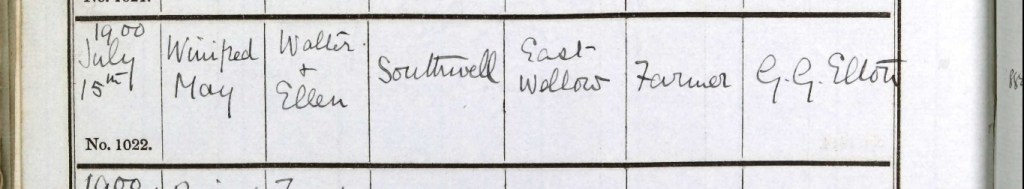

On a summer’s day, Sunday, the 15th day of July 1900, the Southwell family once again made their way to St. Margaret’s Church in Wellow, carrying their youngest daughter, Winifred May, to be baptised. The summer sun shone through the canopy of trees lining the narrow country lanes, casting dappled light on the well-trodden path. Dressed in their finest, Walter and Ellen walked with quiet pride, their children following alongside them, their voices hushed with a sense of occasion.

Inside the ancient stone church, the air was cool despite the warmth of the season. The scent of aged wood and candle wax lingered, and the soft murmur of the congregation filled the space as families gathered for the Sunday service. The Southwells stood at the baptismal font, the same one where Edith and Frederick had been christened in years past. The minister, G. G. Elliott, welcomed them, his voice steady and familiar as he began the sacred rite.

As Walter and Ellen stood solemnly, their baby girl was gently cradled in their arms, her tiny fingers curled against the lace of her christening gown. The minister dipped his hand into the cool water, tracing the sign of the cross upon Winifred’s forehead, blessing her in the name of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit. The weight of tradition, of faith, of generations before them who had stood in that very spot, was keenly felt.

In the official church register, G. G. Elliott recorded the details: Winifred May Southwell, daughter of Walter Southwell, a farmer, and Ellen Southwell of East Wellow. Another name written into the history of St. Margaret’s, another soul welcomed into the fold of the village church.

As the final prayers were spoken, the Southwells returned to their pew, their baby girl now a part of something greater, linked by faith to the community that surrounded them.

A baptism at St. Margaret’s Church in Wellow at the turn of the 20th century would have been a deeply meaningful event, steeped in tradition and faith, marking a child’s formal entry into the Christian community. The ceremony itself, though simple in structure, carried great significance for both the family and the wider village.

The Southwells, like many local families, would have prepared carefully for the occasion. The baby would have been dressed in a long, flowing christening gown, likely made of fine cotton or linen, sometimes passed down through generations. The family, too, would have worn their best clothes, Walter in a formal suit, Ellen in a well-kept dress, and the older children in neatly pressed outfits.

As they made their way to St. Margaret’s Church, the ancient stone building stood as it had for centuries, its Norman features softened by time, its wooden door weathered by generations of hands. Inside, the air was cool and still, filled with the scent of wax candles and polished pews. Sunlight streamed through the stained glass, casting dappled colors onto the stone floor, a quiet reminder of the sacredness of the moment.

The baptism would take place near the start or end of the main Sunday service, with the congregation gathered as witnesses. As the family approached the baptismal font, the minister would stand waiting, dressed in traditional vestments, his voice warm and steady as he welcomed them. The font itself, a centuries-old stone basin, would hold water drawn fresh for the occasion, cool to the touch, symbolizing purity and rebirth.

With the parents and godparents standing close, the minister would ask them to reaffirm their own faith and pledge to guide the child in Christian teachings. Then, cupping his hand, he would gently pour the water over the baby’s forehead three times, speaking the sacred words:

"I baptize thee in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Ghost."

The baby, startled by the sensation, might let out a soft cry or simply blink in curiosity. The minister would then make the sign of the cross on the child’s forehead, a mark of belonging, before offering a blessing for her future.

A quiet moment of prayer would follow, the gentle murmur of voices filling the church as the congregation joined in asking for God’s guidance and protection over the newly baptized child. A hymn might be sung, perhaps a familiar melody like, All Things Bright and Beautiful, lifting the spirits of those gathered.

After the ceremony, the minister would inscribe the child’s name into the church register, alongside those of parents and godparents. The ink, pressed onto parchment, ensured that this day would be remembered, recorded in the history of St. Margaret’s for generations to come.

As the family stepped back outside, the summer air would feel warm and bright, the church bells echoing softly in the distance. Friends and neighbors would gather to offer quiet congratulations, and the Southwells would return home to celebrate the day in their own way, perhaps with a modest family meal, the baby resting peacefully, blissfully unaware of the sacred milestone that had just passed.

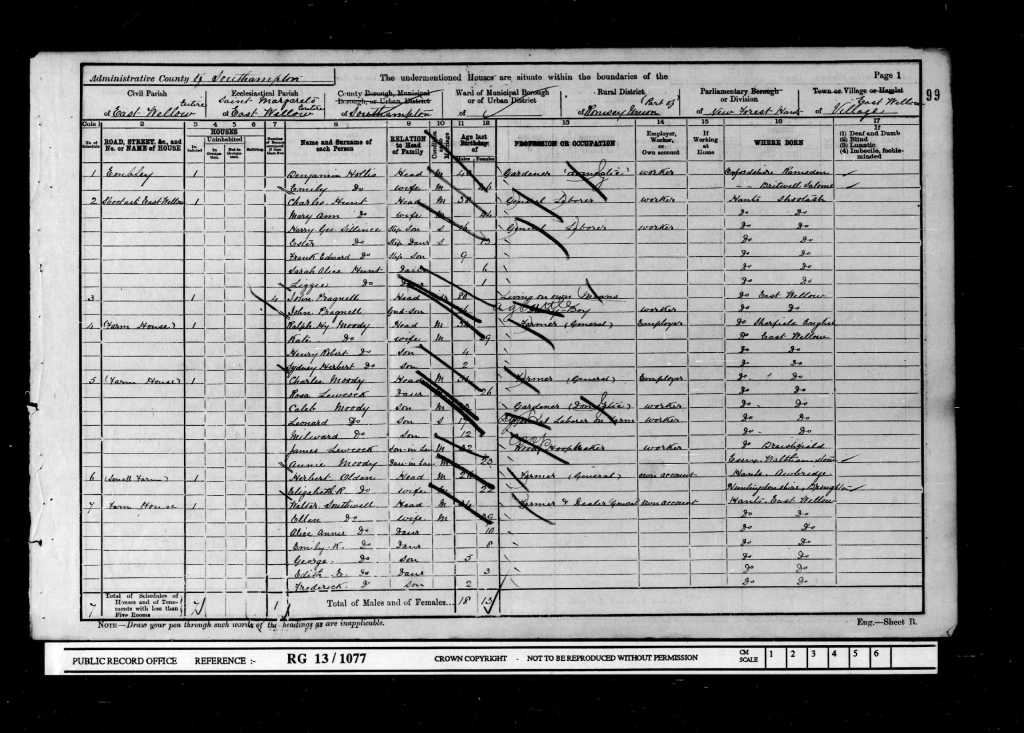

On Sunday, the 31st day of March, 1901, six-year-old Edith Ellen was nestled in the heart of her family, living with her devoted parents, Walter and Ellen, and her five siblings, Alice Annie, Emily Kate, George, Frederick, and little Winifred, at their beloved home, the Farm House in East Wellow, Romsey, Hampshire. The 1901 census captured more than just names and ages; it painted a picture of a household built on love, hard work, and a deep-rooted connection to the land they called home.

Walter, a self-employed farmer and general dealer, worked tirelessly to provide for his growing family, his hands calloused from years of toil, yet always steady and strong. He was the backbone of their world, a man who understood the land as intimately as he did his own children’s laughter. Ellen, the heart of their home, was a mother in the truest sense, nurturing, devoted, and ever-present, tending not just to the practical needs of her children but to their hearts and spirits as well.

What made their home even more special was the unbreakable bond they shared, strengthened by the simple joys of rural life. Every one of Walter and Ellen’s children was born and raised in the same picturesque village of East Wellow, Hampshire, a place where their family’s roots ran deep, where each familiar lane and field held echoes of their ancestors. The farm was more than just a home; it was a legacy, a testament to the love and labor of generations.

For Edith, childhood must have been filled with the simple wonders of country life, running barefoot through the fields, the scent of fresh hay in the air, the rhythmic sounds of her father’s work, and the warmth of her mother’s voice calling her in from play. Though life in 1901 came with its hardships, the Southwell family had something far greater than wealth or privilege, they had each other, and that made all the difference.

In 1911, life in England was at a crossroads, transitioning from the opulent Edwardian era to a time of change that would soon be defined by the tumult of war. For Edith Ellen and her family, it was a year that reflected both the comforts and challenges of life at the time.

On Sunday, April 2nd, the 1911 census was completed, providing a detailed snapshot of life in England. Edith, at 14 years old, was living with her parents, Walter and Ellen, along with her siblings, Emily, 19, George, 15, Frederick, 12, and Winifred, 11. The family had moved from East Wellow to Tote Hill in Lockerley, a small village nestled near the market town of Romsey, Hampshire, an area renowned for its countryside charm.

Lockerley, at the time, was a picturesque village with rolling hills, open fields, and rural tranquility. The pace of life there was much slower than in the busy industrial cities. The village was close-knit, with a strong sense of community, yet it was also marked by the contrasts between rural beauty and the burgeoning industrialization just a short distance away. Life for Edith and her family in Lockerley would have been influenced by this mix of quiet village life and the growing social changes of the early 20th century.

Edith’s father, Walter, was self-employed, working as a dealer of homely and garden produce, an occupation that would have involved selling fruits, vegetables, and other goods grown on the family’s land, or sourced from nearby farms. It was hard work, and though not glamorous, it allowed the family to sustain themselves. His job as a dealer meant that he often interacted with people from all walks of life, possibly traveling between local markets or selling directly to his neighbors. It was not the wealthy lifestyle of the aristocracy, but it was a stable and dependable means of living in the country.

At the time, Edith’s mother, Ellen, would have been focused on managing their household. With six children to care for, including the youngest, Winifred, it was a busy household. Ellen was also responsible for filling out the census return in 1911, a task she took seriously. On the form, she noted that she and Walter had been married for 21 years and had six children, each of them still living. This fact in itself was significant, as many families at the time had lost children to illness, accidents, or the harsh realities of early 20th-century life.

The family’s home in Lockerley was modest, a four-room dwelling, typical of many rural homes at the time. Though not large by modern standards, it was a place where the family could be together, eat their meals, and share in the daily rhythms of life. Heating would have come from a coal fire, the primary source of warmth in most homes at the time, while lighting would have been provided by gas lamps or perhaps the early use of electricity, though this was not yet widespread in rural areas.

For Edith and her siblings, life in 1911 meant balancing work and play. George, at 15, was already working as a grocer’s assistant, likely helping in a local shop or delivering goods to nearby homes, possibly working for his father. This was common at the time, as children in working-class families often took jobs to help support their parents. Life wasn’t easy for them, but the work was steady, and they played an important role in the family’s survival.

As for Edith, she would have been entering the early years of adolescence, at an age when girls often started to take on more responsibility within the home. The 1911 census also marked a moment where change was coming for women, the suffragette movement was beginning to make waves across the country. Though Edith was too young to be involved directly in such activism, her life would have been impacted by the conversations around women’s rights and the growing desire for equality.

Meanwhile, Alice Annie, Edith’s sister, was not at home in Lockerley that day. She was visiting Mr. George Moore’s home at Number 22, Bell Street, Romsey, where she was spending time with her future husband’s family. Her absence was noted in the census return, as it often was when family members were away on visits or living elsewhere. This separation likely wasn’t unusual, as young women of the time often worked or married outside their immediate family circle as they reached adulthood.

The year 1911 also saw important historical events that would impact the country in the years to come. The Titanic, the “unsinkable” ship, was launched that year, and its eventual tragic sinking would shock the world in 1912. The tensions between Ireland and Britain were also coming to a head, with the Irish Home Rule issue at the forefront of political debate. These matters were already being discussed in homes across England, and although Edith and her family were far removed from the political machinations of Westminster, such issues would shape their future world in unexpected ways.

Social divisions were still very much a part of life. The rich lived in grand estates and enjoyed the luxuries of the Edwardian era, with servants to tend to their every need, while the working-class families like Edith's lived modestly, often working long hours to make ends meet. The disparity between the rich and poor was a stark one, while the wealthy enjoyed fine foods, fashionable clothes, and cultural privileges, the working class could only dream of such comforts. The contrast between these classes was not only in wealth but in opportunities, and the gap between them was starting to widen as political movements like socialism and women’s suffrage gained strength.

But in Lockerley, Edith’s world was one of family, hard work, and quiet community. Though the sanitation systems in rural areas like theirs were often rudimentary by today’s standards, the close-knit village meant that people looked out for one another. The food in their household would have been simple, but nourishing, stews, bread, potatoes, and the fruits and vegetables that Walter could sell or grow. Their entertainment would have been humble too, with socializing in the local pub, attending church, and possibly enjoying a walk through the countryside.

As a community, they would have been far removed from the smog and pollution of industrial cities like London. Life in the countryside was quieter, cleaner, and more connected to nature. The environment around them, with its farmlands and rural scenery, likely provided Edith and her family with a sense of peace and escape from the tensions that were starting to brew in the wider world.

The 1911 census stands as a poignant reminder of these moments, capturing a fleeting moment in time. While Edith’s world in Lockerley was marked by love, family, and simple comforts, the changes happening in the wider world, political, social, and industrial, would soon touch her life in profound ways. The census, handwritten by her mother Ellen, offers us a glimpse into a family on the brink of the modern world, showing how the everyday lives of ordinary people were just as significant as the grand events unfolding around them.

The 1911 census is especially fascinating because it was the first one to be completed by hand. It’s a unique glimpse into the past, and although some handwriting is difficult to read, it’s truly special to see the personal touch of our ancestors. Ellen’s handwriting stands out, however, as particularly impressive and beautiful, a lovely reminder of the care and thought she put into her family’s records.

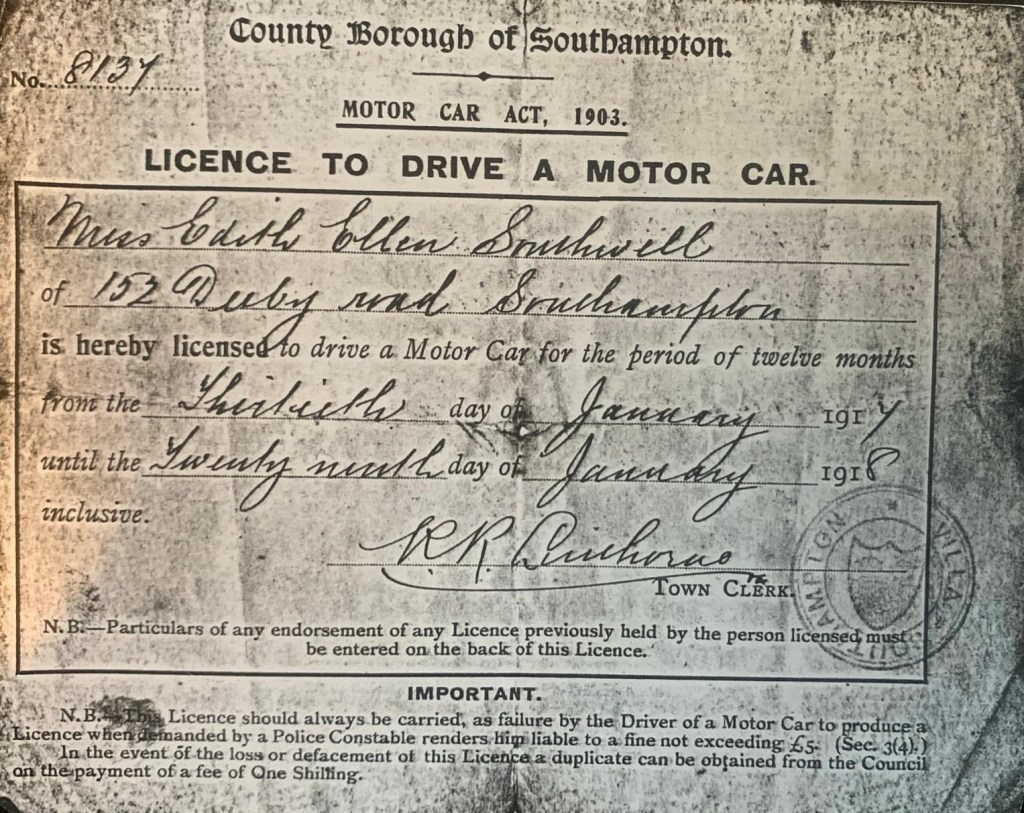

On Saturday the 13th day of January 1917, Edith Ellen Southwell took a bold and remarkable step for a woman of her time, she was issued a motor car license, granting her the legal right to drive for a full year. At a time when automobiles were still a relatively new sight on the roads and female drivers were uncommon, Edith was forging a path of independence and modernity. Her official license, issued by the County Borough of Southampton under the Motor Car Act of 1903, was a formal recognition of her ability to handle a motor vehicle. The document bore the signature of the Town Clerk and stated:

“Miss Edith Ellen Southwell, of 152 Duby Road, Southampton, is hereby licensed to drive a Motor Car for the period of twelve months from the Thirteenth day of January 1917 until the Twenty-ninth day of January 1918 inclusive.”

It also contained important legal warnings, reminding Edith that she must always carry her license while driving, as failure to produce it upon a police officer’s request could result in a fine of up to £5. Additionally, if the license were lost or damaged, a duplicate could be obtained for a fee of one shilling.

Holding this license was more than just a piece of paper, it was a symbol of progress. Edith was not only defying the traditional roles of women at the time, but she was also stepping into an era of change, where the ability to drive represented freedom, opportunity, and self-sufficiency. Edith’s license tells us that she was a woman determined to embrace the modern world on her own terms and I love that about her.

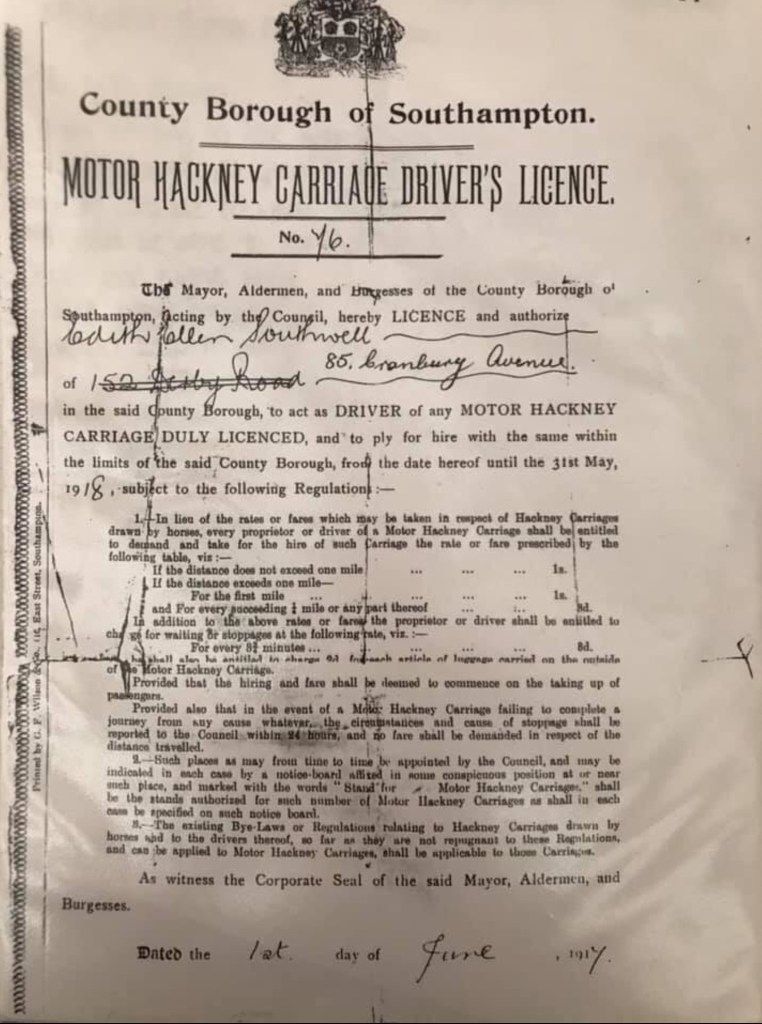

Edith made history on Friday, the 1st day of June, 1917, when she became the first woman in Southampton to be issued a Motor Hackney Carriage Driver’s License. This was an extraordinary achievement at a time when driving, let alone being a licensed taxi driver, was still largely considered a man’s profession.

Her official license, numbered 76, was issued by the County Borough of Southampton. It was formally recorded that "The Mayor, Aldermen, and Burgesses of the County Borough of Southampton, acting by the council, hereby LICENSE and authorise Edith Ellen Southwell of 152 Derby Road, (which was crossed out and replaced with 85 Cranbury Avenue), in the said County Borough, to act as DRIVER of any MOTOR HACKNEY CARRIAGE DULY LICENSED, and to ply for hire with the same within the limits of the said County Borough, from the date hereof until the 31st May, 1918, subject to the following Regulations."

Unfortunately, the small print listing the many regulations has faded over time, making it difficult to decipher. However, what remains clear is the significance of this moment, Edith had broken barriers, paving the way for future generations of women in the workforce. Her license wasn’t just a piece of paper, it was a symbol of progress, independence, and determination in a rapidly changing world.

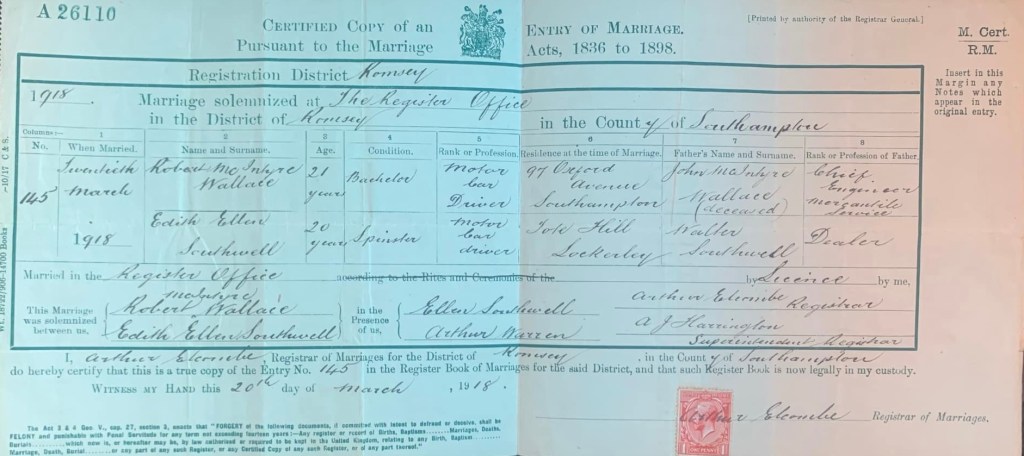

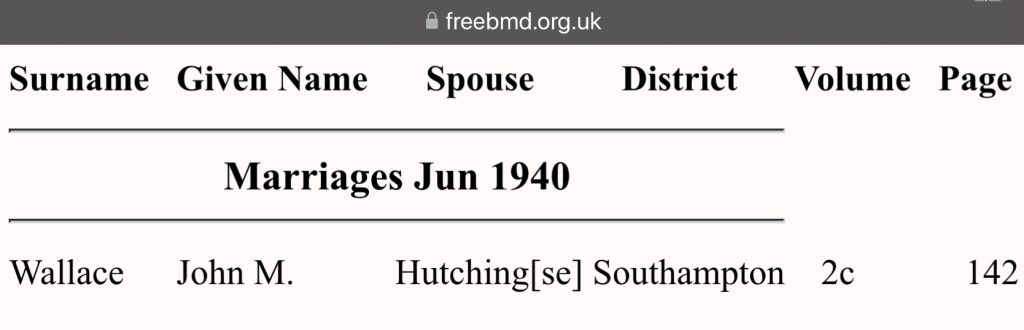

On a spring day, Wednesday, the 20th day of March, 1918, Edith Ellen Southwell, just 20 years old, stood on the threshold of a new chapter in her life. As a young woman from Tote Hill, Lockerley, she had spent her days surrounded by the familiar comforts of family, yet on this day, she stepped forward into something new and unknown, marriage. She was about to become Edith Ellen Wallace, pledging her heart to the man she loved, 21-year-old Robert McIntyre Wallace.

Robert, a bachelor from Number 97, Oxford Avenue, Southampton, was a man of quiet determination, with a steady presence that had captured Edith’s heart. Their love had blossomed in the midst of changing times, and now, standing together at The Register Office in Romsey, Hampshire, they were ready to embark on the journey of life as husband and wife.

The ceremony would have been simple, without the grandeur of a church wedding, yet no less meaningful. Arthur Elcombe, the registrar, and A. J. Harrington, the superintendent, officiated and carefully recorded the details of their union in the official Marriage Register. Robert’s father, the late John McIntyre Wallace, had been a chief engineer in the mercantile service, a life spent ensuring a legacy of strength and resilience. Edith’s father, Walter Southwell, was recorded as a dealer, a man whose work had long provided for his family. These details, written in ink, were more than just formalities, they were reminders of the families who had shaped the two people standing before them, ready to create a new family of their own.

Both Edith and Robert had entered a profession ahead of its time, motor car drivers. It was an occupation that spoke of modernity and progress, a reflection of a world that was rapidly changing as the First World War drew to a close. For Edith, in particular, it was a sign of independence, of a woman stepping into roles once reserved for men, of a future where she could hold her own beside her husband in a shifting society.

Standing beside Edith as a witness to this momentous occasion was her mother, Ellen Southwell, a woman who had nurtured and guided her from birth, now watching her take this bold step into marriage. Also present was Arthur Warren, whose name in the registry hints at a connection, a family friend, perhaps, or someone important to Robert and Edith, there to bear witness to their vows.

Their wedding was a promise, a beginning, and a symbol of love and hope during uncertain times. Though the world around them was changing in ways they could not yet imagine, Edith and Robert stepped forward together, hand in hand, ready to face whatever lay ahead.

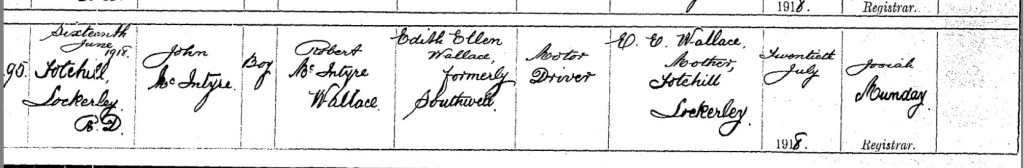

On a summers Sunday, the 16th day ofJune, 1918, in the heart of Totehill, Lockerley, Edith Ellen Wallace, welcomed her firstborn son into the world. It was a moment filled with both excitement and tender love, as this new chapter of her life as a mother began. Little John McIntyre Wallace, named after his father’s late father, was born to Edith and her husband, Robert McIntyre Wallace, in their home in the peaceful countryside of Hampshire, a place filled with the warmth of family and the beauty of nature.

Edith’s journey as a mother started in the same home where she and Robert had settled, the house in Totehill, a rural village that had been their haven since their marriage just months before. Though the world was still embroiled in the aftermath of war, life for Edith and Robert took on a new rhythm with the arrival of their son. The excitement of their new little one must have filled their home, and Edith would have been full of tender love as she looked into the eyes of her son.

On Saturday, the 20th day of July, 1918, just over a month after John’s birth, Edith made the trip to Romsey, to register her son's birth. She traveled from the small, quiet village of Lockerley to the market town of Romsey, where the official records of new life were kept. The register for John’s birth was recorded by Josiah Bunday, the local registrar, who filled in the details of this new arrival.

In the official record, it was noted that Robert McIntyre Wallace, Edith’s husband, was a motor driver, a profession that was becoming more common as the automobile industry grew, and both Edith and Robert had embraced this modern change in their lives. Edith, now known as Edith Ellen Wallace, formally Southwell before her marriage, had her name recorded with pride as the mother of this beautiful boy, who would carry their legacy forward.

This moment, as Edith stood in the register office with her son’s birth certificate in hand, was a reminder of the hopes and dreams they had for little John. It marked not just the birth of a son, but the continuation of the Southwell-Wallace family story, one that would be filled with love, memories, and the quiet triumphs of life in a world that was slowly beginning to rebuild after the hardships of war.

For Edith, the journey from bride to mother was swift, but filled with deep love and meaning. The name John McIntyre Wallace, would forever connect her son to his paternal heritage and to the love and respect that Edith and Robert shared for one another and for the families that came before them. The birth of John was a moment of pure joy, a reminder of the new beginnings that family brings, even amidst the challenges of life.

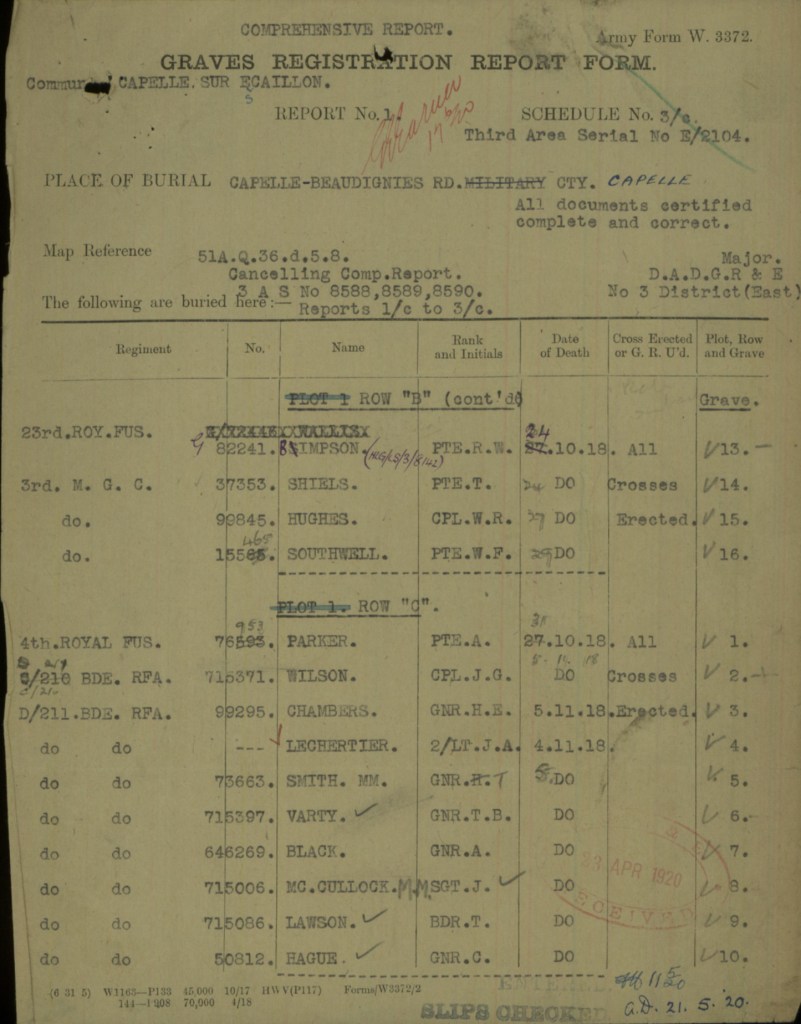

The year 1918, filled with so much personal joy for Edith Ellen Wallace and her family, was also marked by deep sorrow and loss. Frederick Walter Southwell, Edith’s beloved brother, known to many as Private Walter F. Southwell, was serving in the Machine Gun Corps (Infantry), 3rd Battalion, during the tumultuous days of the First World War.

Frederick, like so many young men of his generation, had answered the call to serve his country. He had enlisted with the hope of returning home safely, like many others, and contributing to the war effort that had so deeply altered the course of the world. But the harsh realities of battle were never far from their minds. Tragically, Private Walter F. Southwell, gave his life in the service of his country during the final months of the war.

On Tuesday, October 29th, 1918, Frederick’s life was cut short during battle. The loss of this young man, just 19 years old, was felt deeply by his family, particularly by his sister, Edith. Though Edith had recently become a mother herself, the joy of her son’s arrival would forever be tinged by the painful knowledge that her brother, her childhood companion, would never return.

Frederick’s sacrifice in the brutal conflict of the First World War was a tragic reminder of the cost of freedom and the immense toll the war took on families like Edith’s. While Edith's new life as a mother was full of promise, the shadow of war loomed large over her family, forever marking the Southwell family’s history with grief and heartache.

The news of Frederick’s death would have struck Edith hard, losing a brother who had been a part of her life since childhood, a young man whose life was full of potential but taken too soon. His death, along with the countless others, would leave an indelible mark on the family and the entire community, as they struggled to come to terms with the many lives lost in this devastating conflict.

Frederick Walter Southwell’s name, like so many others, became a part of the enduring memory of the fallen in the First World War, and his sacrifice would never be forgotten. For Edith, his death would forever remain a painful chapter in her own personal history, a reminder of the heavy price of war and the depth of loss it brought to so many families.

After the tragic death of Edith’s brother, Private Walter F. Southwell, on Tuesday, the 29th day of October, 1918, he was laid to rest at the Capelle-Beaudignies Road Cemetery, in France, a place of solemn reflection for those who gave their lives in the First World War. Walter’s final resting place was in Plot B. 16, where he was commemorated alongside countless other soldiers who made the ultimate sacrifice for their country.

The Capelle-Beaudignies Road Cemetery, stands as a testament to the bravery and courage of those who fought and died on the front lines, and Walter’s burial there is a poignant reminder of the price of peace and freedom. His grave, like those of his comrades, would be a place where Edith and her family, though far away, could find solace, knowing that he was not forgotten, and that his sacrifice would be honored for generations to come.

Though Edith's heart ached with the loss of her brother, she could take some comfort in the fact that Walter was buried with dignity and respect, surrounded by others who had given their lives in the same struggle. His name and his story would live on, etched in the memories of those who loved him and in the sacred grounds of the cemetery where he now rested. Walter F. Southwell's memory would remain an enduring part of his family's legacy, and his sacrifice would never be overlooked.

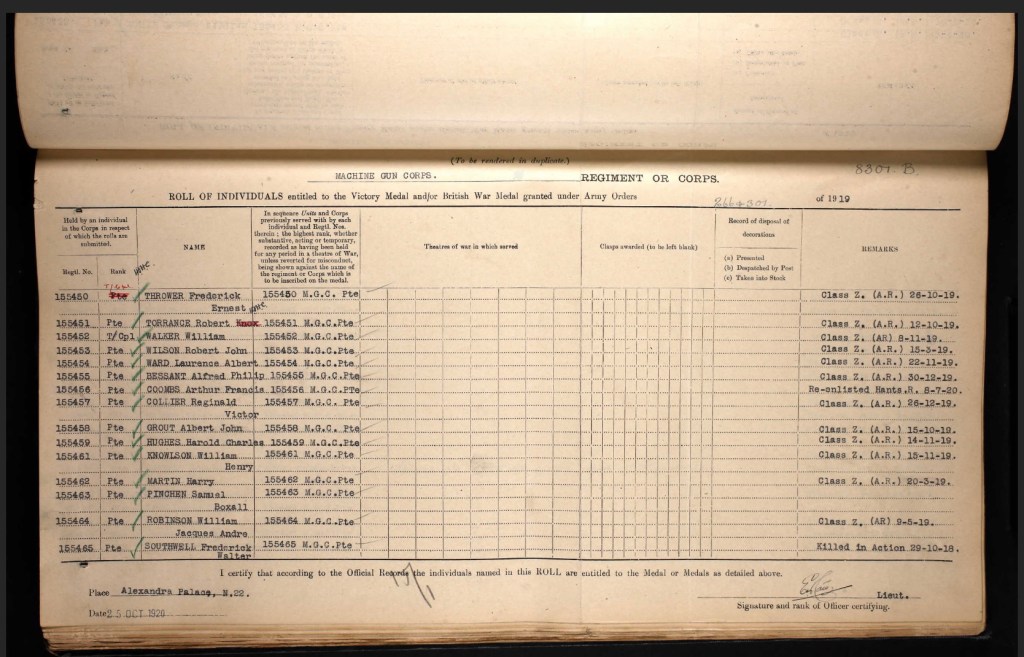

On Monday the 25th day of October, 1920, a deeply emotional moment came for the Southwell family, as they were posthumously awarded the Victory Medal for Frederick Walter Southwell, their beloved son and brother. This medal, given in recognition of his sacrifice during the First World War, symbolised the immense cost of the conflict and the bravery Frederick displayed as part of the Machine Gun Corps (Infantry), 3rd Battalion.

While Edith and the family must have been deeply proud of Frederick’s service and the honor this medal represented, it was also a bitter reminder of the loss they had suffered. The Victory Medal, though a symbol of recognition, could never replace the young life taken far too soon. It was a tribute to his courage, his role in the war effort, and his contribution to the eventual victory.

The medal itself, awarded years after the war had ended, may have served as both a source of pride and heartache for the Southwell family. For Edith, it was another way of honoring her brother’s memory, even as she navigated the joys and challenges of her new life with Robert and their son. The medal, like Walter’s grave at Capelle-Beaudignies Road Cemetery in France, became a reminder that his sacrifice would never be forgotten, but also a poignant symbol of the grief that war had left in its wake for families like hers.

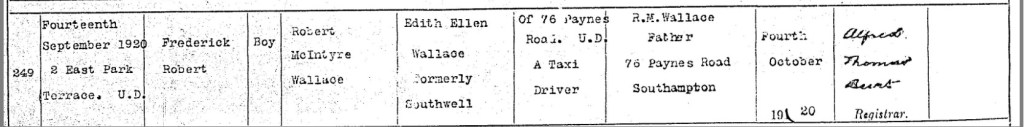

On Tuesday, the 14th day of September, 1920, in the bustling port city of Southampton, Edith Ellen Wallace welcomed her second son into the world. Frederick Robert Wallace, named in honor of both his late uncle Frederick Walter Southwell and his father, Robert McIntyre Wallace, was born at Number 2, East Park Terrace, a place that would forever hold the memory of his first breaths.

For Edith, holding her newborn son in her arms must have been a moment of deep love and reflection. The name Frederick carried a weight of family history, one of loss and remembrance, but also of strength and resilience. Her heart must have swelled with bittersweet emotion as she whispered his name, remembering the brother she had lost not even two years earlier, yet embracing the joy of this new life that now lay in her arms.

On Monday, the 4th day of October, 1920, Robert made the journey to register the birth of their second son at the Southampton Registry Office. There, Alfred Thomas Bunt, the registrar, officially recorded Frederick Robert Wallace as the son of Robert McIntyre Wallace, now working as a taxi driver, and Edith Ellen Wallace (formerly Southwell) of Number 76, Paynes Road, Southampton.

Life in Southampton was vastly different from the quiet countryside of Lockerley, where Edith had spent most of her early years. The city was alive with the constant movement of ships, trade, and people, and it was here that Edith and Robert were building their home, their family, and their future. With two young boys now under their care, their world was one of new beginnings, shaped by both the past they carried with them and the dreams they held for the future.

Though the shadow of war still lingered, and the memory of her brother’s sacrifice was never far from Edith’s heart, the birth of Frederick Robert Wallace was a reminder that life continued, that love, family, and hope could flourish even after the darkest of times.

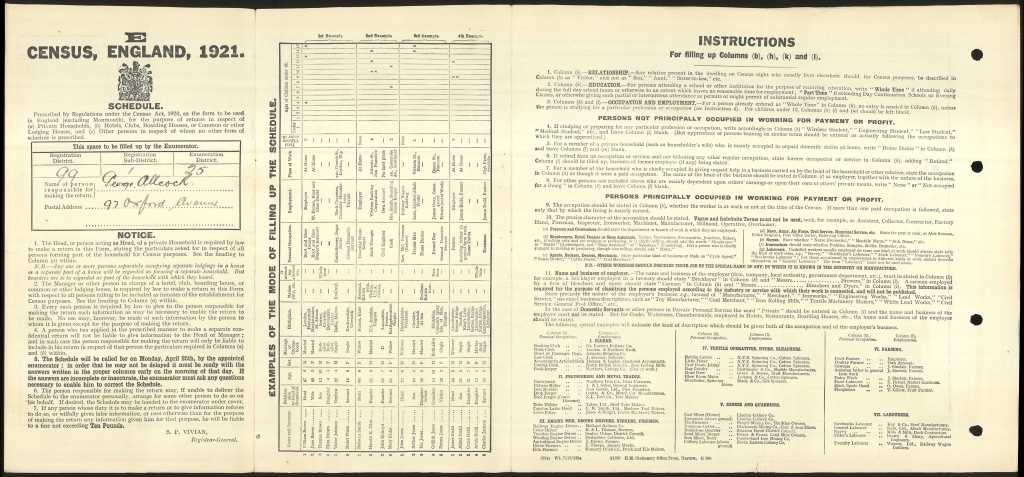

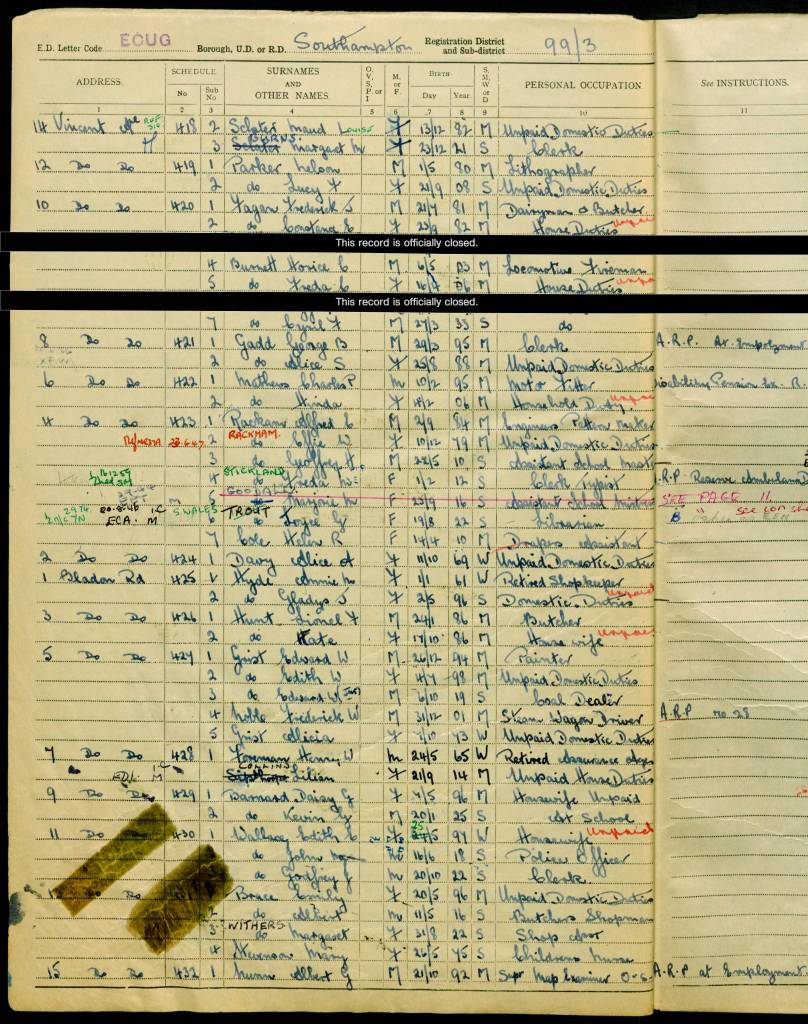

On Sunday, the 19th day of June, 1921, (The day. Of the 1921 census.) Edith Ellen, now 23 years old, had settled into a new chapter of her life in Southampton, a city full of movement and opportunity. She and her young family were living at Number 97 Oxford Avenue, a bustling household that blended generations under one roof.

Edith was now part of her husband’s family home, residing as the daughter-in-law of George W. Allcock, a 42-year-old ship’s steward who worked for the Cunard Steamship Company Ltd in Liverpool. His work took him aboard the S.S. Berengaria, one of the grand transatlantic liners of the time, a ship that carried the hopes and dreams of countless passengers between England and America. His frequent absences at sea left his wife, Maud E. Allcock, aged 48 years and 3 months, to maintain the home and look after the family, dedicating herself fully to her role in the household.

Edith’s 22-year-old husband, Robert Wallace, was establishing himself as a motor coach driver, working for F. May Six Dials Solon in Southampton. With the growing popularity of motor transport, his role was part of an expanding industry, helping people travel between cities and towns with greater ease than ever before.

Life was undoubtedly full for Edith, balancing her role as a young mother to her two sons, John McIntyre Wallace, aged 3 years, and baby Frederick Robert Wallace, just 9 months old. Both boys were listed in the census under their grandfather’s household, with John recorded as the grandson of the head of the household, a sign of the close-knit nature of the family structure in this time.

But the Allcock-Wallace household did not consist of just family. They also shared their home with two boarders, Emily O'Brien, a 55-year-old married woman, and her husband, John O'Brien, a 59-year-old civil servant originally from Ireland. John worked for the Crown at the Ordnance Office in Southampton, likely involved in government supply chains, a crucial role in the post-war years. Emily, listed under "House Duties," likely contributed to the upkeep of the household alongside Maud.

Though life was not always easy in a multi-generational home, Edith was surrounded by family, her husband, children, in-laws, and even boarders who had become part of their daily lives. Southampton, with its ever-moving ships, its promise of new opportunities, and its blend of working-class resilience, was now the place she called home. As she cared for her growing children and supported Robert in his career, Edith was building a future in a world still finding its footing in the wake of the Great War.

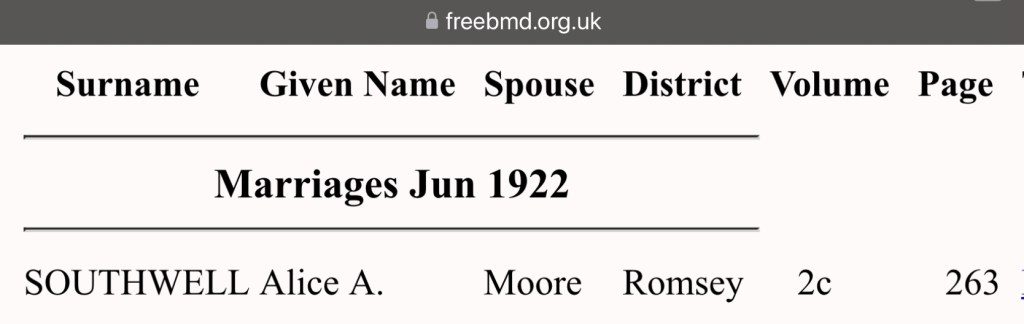

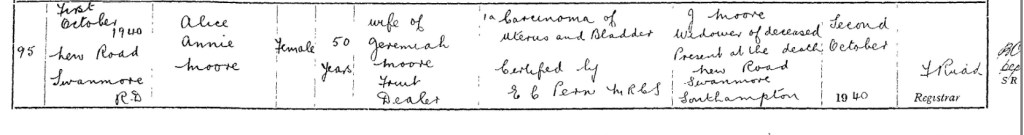

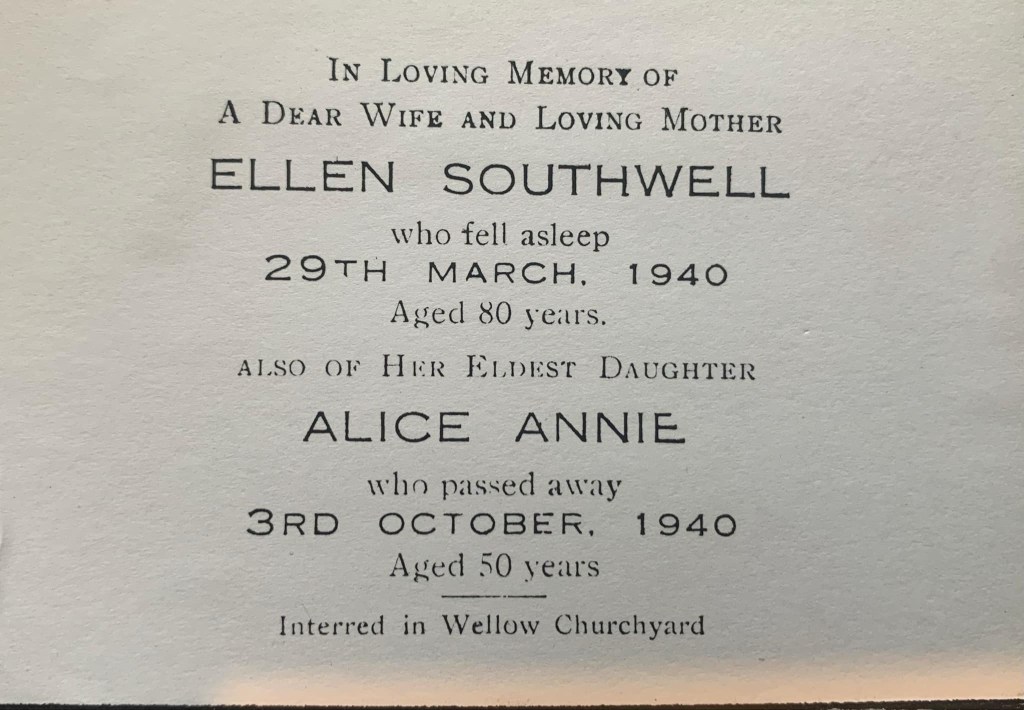

On Tuesday, the 2nd day of May 1922, Edith’s eldest sister, Alice Annie Southwell, stood before family and friends in Romsey, Hampshire, to marry Jeremiah Moore. It was a day filled with joy and quiet anticipation, the culmination of months of preparation and years of companionship that led them to this moment.

Romsey, with its historic charm and strong community ties, provided a fitting backdrop for their union. The church oe registry office, surely was adorned with spring flowers, welcomed the couple as they exchanged vows, pledging their love and devotion before witnesses who had known them since childhood. The ceremony, conducted with solemn grace, was was most likely followed by a modest yet heartfelt celebration, where laughter and well wishes filled the air.

As Alice stepped into this new chapter of her life, she carried with her the strength and values instilled by her family in East Wellow. The Southwells, rooted in the traditions of farming and rural life, had watched her grow into a woman of warmth and resilience, ready to build a home of her own with Jeremiah.

For those interested in official documentation, their marriage certificate can be obtained using the following GRO Reference information:

GRO Reference - Marriages, Jun 1922, Southwell, Alice A, Moore, Jeremiah, Romsey, Volume 2c, Page 263.

Their story, like so many others, was woven into the fabric of Hampshire’s history, a tale of love, family, and the enduring bonds that tie generations together.

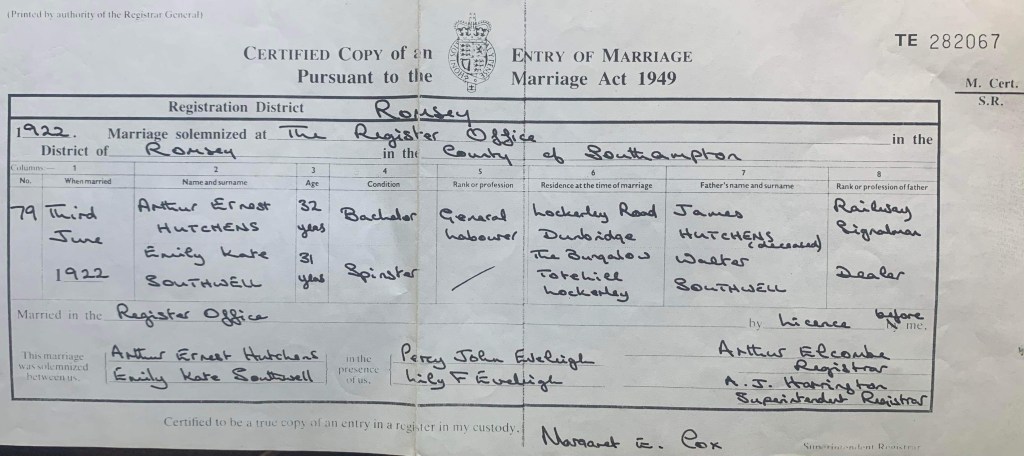

On Saturday, the 3rd day of June, 1922, Edith’s sister, Emily Kate Southwell, stood in the Romsey Register Office, ready to take the next step in her life. At 31 years old, she had built a life for herself at The Bungalows, Totehill, Lockerley, but on this day, she would leave behind her maiden name and become Mrs. Hutchens.

Arthur Ernest Hutchens, a 32-year-old bachelor from Lockerley Road, Dunbridge, stood beside her. A general labourer by trade, he had worked hard to establish himself, and now he was ready to build a future with Emily. Though their wedding was not held in a grand church, the ceremony was no less meaningful. The Register Office, with its official yet intimate setting, bore witness to the solemn exchange of vows, binding them together in law and love.

Arthur Elcombe, the registrar, and A. J. Harrington, the Superintendent Registrar, presided over the ceremony, ensuring that every word spoken and every signature written was properly recorded. As part of the official documentation, they noted that Emily was the daughter of Walter Southwell, listed as a dealer, and Arthur was the son of the late James Hutchens, who had worked as a railway signalman.

Standing as witnesses to this union were Percy John Eveleigh, Lily F. Eveleigh, and Margaret E. Cox, family or friends who had been chosen to share in this deeply personal moment. Their signatures in the register were more than just ink on paper, they were a testament to the love and support that surrounded the couple as they embarked on their journey together.

Though Emily had spent her years as a spinster before this day, she now walked hand in hand with Arthur, stepping into a shared future. The quiet village life of Hampshire, with its rolling fields and familiar faces, would continue around them, but for Emily and Arthur, everything had changed. They were no longer just two individuals, they were husband and wife, bound together by love, promise, and the turning of time.

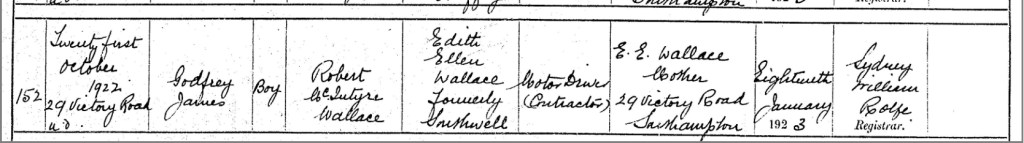

On Saturday, the 21st day of October, 1922, Edith and Robert welcomed their third son, Godfrey James Wallace, into the world. Born at their home, Number 29, Victory Street, Southampton, his arrival marked another joyful chapter in their growing family. The walls of their home, which had already seen the laughter and footsteps of their older children, now embraced the soft cries of a newborn, a symbol of new beginnings and the unbreakable bond of family.

In the chill of mid-January, on Thursday the 18th of 1923, Edith made her way to the Southampton Register Office to formally record the birth of her son. The duty of registration was an important one, an official acknowledgment of the life they had brought into the world. The registrar, Sydney William Rolfe, carefully entered the details into the Birth Registry, ensuring that Godfrey’s name would be preserved in the records of time.

The entry noted that Godfrey James Wallace was the son of Robert McIntyre Wallace, a Motor Driver (contractor), and Edith Ellen Wallace, formerly Southwell, both residing at Number 29, Victory Street. With each stroke of the pen, the details of his birth were secured in the archives, a document that would follow him through life, connecting him always to the place and the people from which he came.

As Edith stepped away from the registrar’s desk, the weight of her responsibilities and joys as a mother must have filled her heart. Godfrey, still so small and unaware of the world beyond their home, had now been officially named and recognised. His journey was just beginning, surrounded by the warmth of his family and the steady presence of his parents, who had already carved a life for themselves in the bustling port city of Southampton.

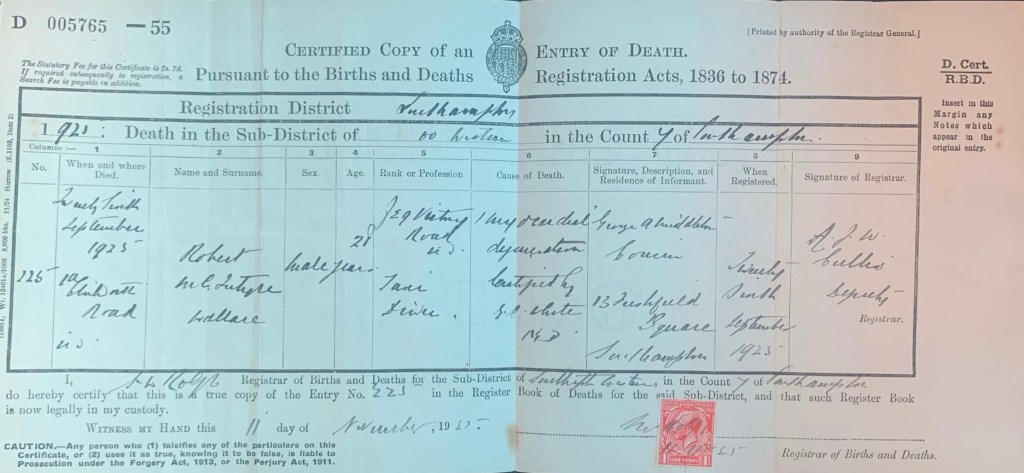

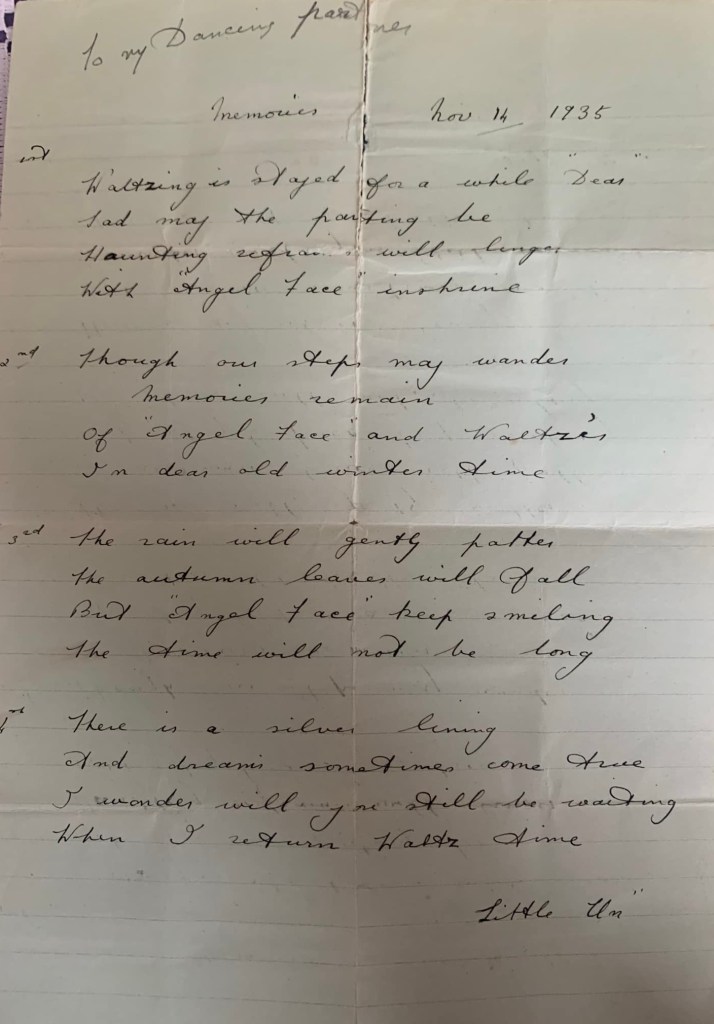

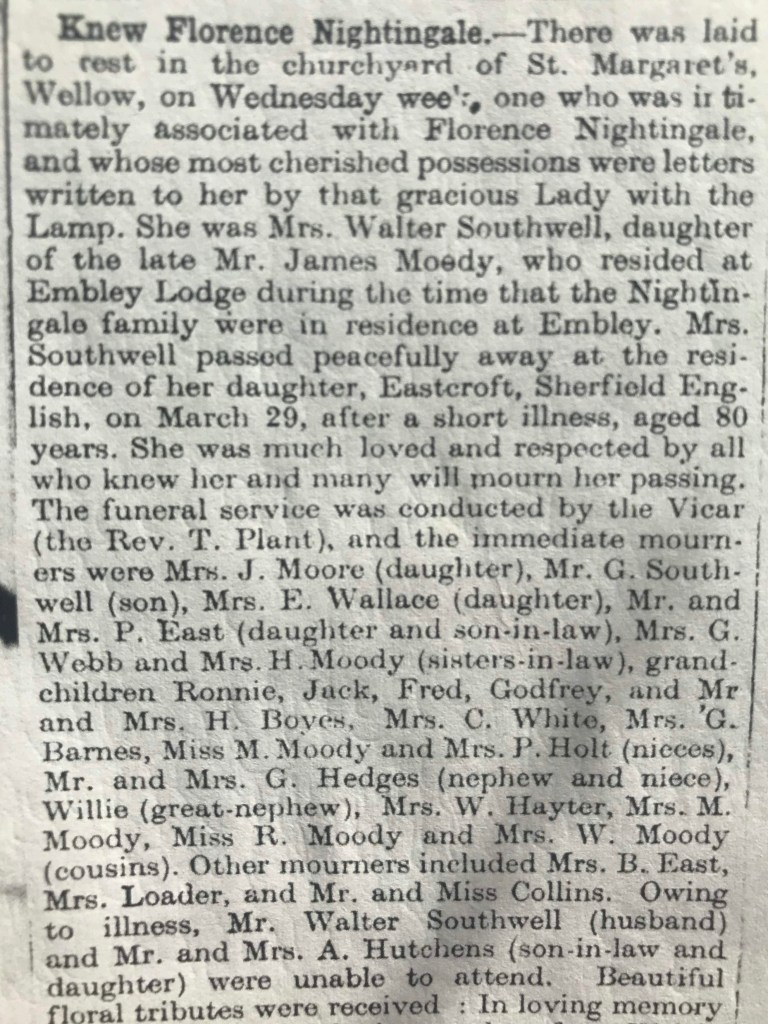

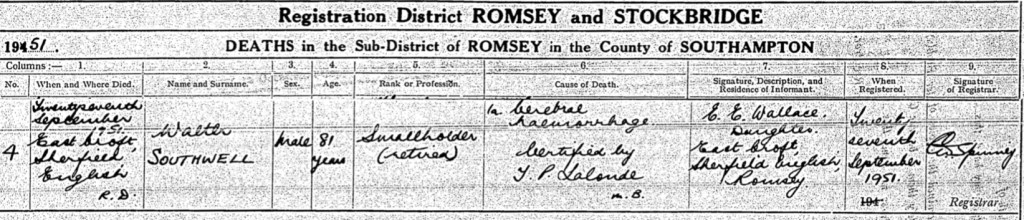

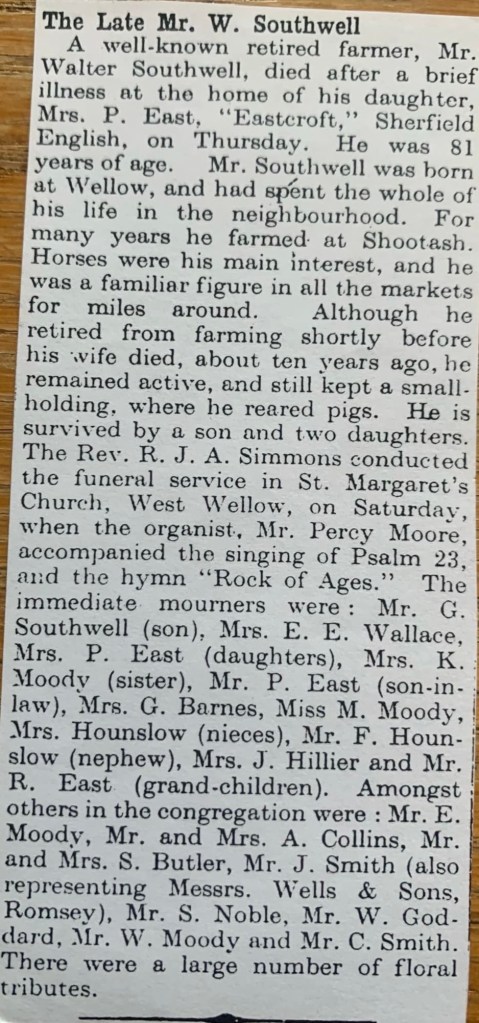

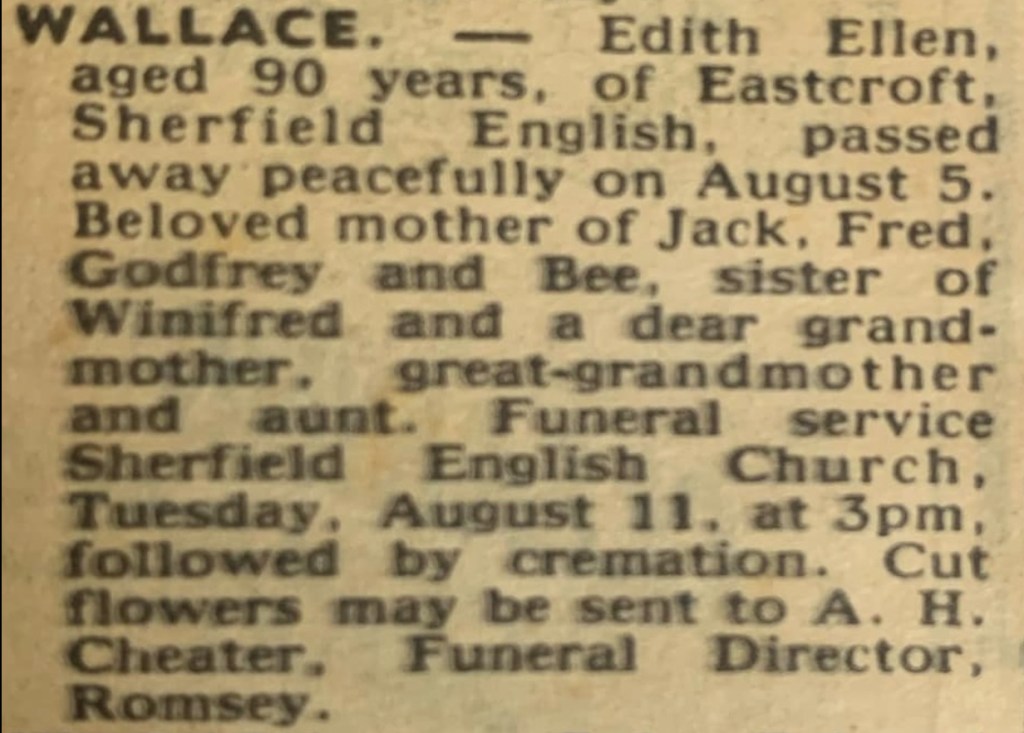

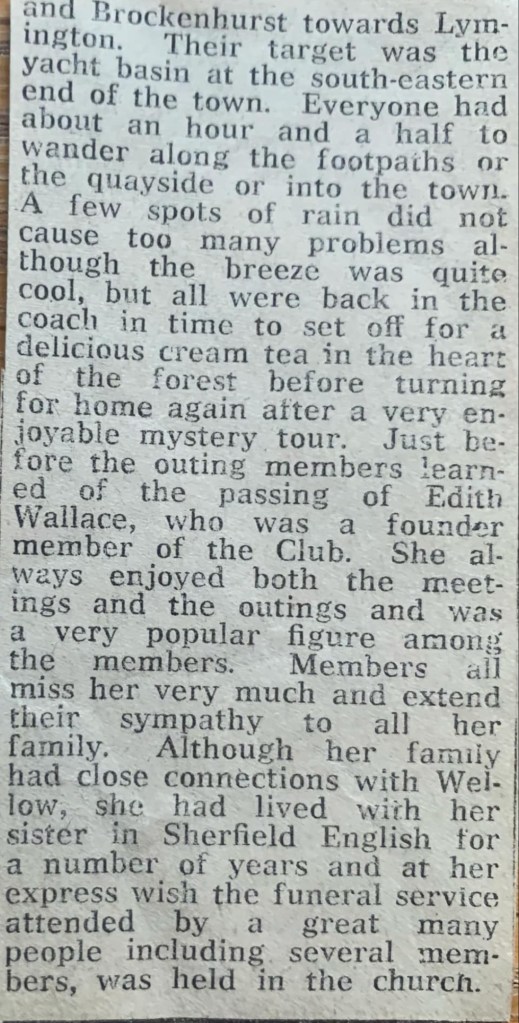

Saturday the 26th day of September 1925 was a day that would forever leave a void in Edith’s heart. Her beloved husband, Robert McIntyre Wallace, the man she had built a life with, her soul mate, and the love of her life, was taken from her far too soon. At just 28 years old, with so many dreams and years ahead of him, Robert passed away at 1a Chilworth Road, Southampton, the address of the Southampton Infirmary, is now where Southampton General Hospital stands today.

His passing was caused by myocardial degeneration, a cruel and silent thief that took him away from the family he had worked so hard to provide for. Dr. E. C. White, the medical director, certified his death, and Robert’s cousin, George A. Middleton of Freshfield Square, stepped forward to register it that very same day. The registrar, A. J. W. Collins, recorded the details in the official death registry, forever marking the day Edith’s world shattered.

Losing a loved one is always heartbreaking, but when a young life is cut short so suddenly, the pain is almost unbearable. Robert wasn’t just a husband, he was Edith’s partner in every sense of the word, the father of her children, and the man she had expected to grow old with. But the cruelty of fate didn’t stop there. As if losing Robert wasn’t tragic enough, Edith was heavily pregnant with their daughter at the time of his death. The weight of grief and the uncertainty of what lay ahead must have been overwhelming, yet she had no choice but to carry on, for herself, for their children, and for the little one who would never have the chance to know her father.

The details recorded on Robert’s death certificate are not the clearest, making it difficult to decipher everything written. But through careful research and the dedication of family, particularly with the help of my sister-in-law Sarah, we have done our best to document the correct information, ensuring that Robert’s story is remembered with the accuracy and respect he deserves. His life, though short, was filled with love, and his memory would remain a guiding light in Edith’s heart as she faced the years ahead without him.

In the early 1900s, 1a Chilworth Road in Southampton, Hampshire, was the address of the Southampton Union Workhouse, an institution established under the Poor Law system to provide shelter and employment for the impoverished. The workhouse system had been a significant part of British social welfare since the 17th century, evolving over time to address the needs of the destitute.

Southampton's first workhouse originated from a bequest in 1629 by John Major, who left £200 to establish a house of twelve rooms for the poor. Over the centuries, the workhouse system expanded and adapted, with the Southampton Union Workhouse eventually being situated at 1a Chilworth Road. This location later became associated with the Southampton Infirmary, which provided medical care to the city's residents.

By the early 20th century, the workhouse at 1a Chilworth Road had evolved to include medical facilities, serving as both a refuge for the poor and a place where the sick could receive care. The address became synonymous with the infirmary, reflecting its dual role in providing both social support and healthcare services to the community.

In subsequent years, the area underwent significant changes, with the original workhouse and infirmary eventually being replaced by modern healthcare facilities. The road itself was renamed Tremona Road, and the site is now home to Southampton General Hospital, a major medical center serving the region.

The history of 1a Chilworth Road exemplifies the broader evolution of social welfare and healthcare in England, transitioning from the workhouse system of the 17th century to the comprehensive medical services provided by institutions like Southampton General Hospital today.

Family and friends gathered beneath the solemn grey skies of Southampton Old Cemetery, Hill Lane, on Wednesday, the 30th of September 1925, to say their final goodbyes to Robert McIntyre Wallace. The weight of their grief hung heavy in the cool autumn air as they made their way to Block 182, Number 18, the final resting place he would now share with his father, John McIntyre Wallace. In time, his mother Maude would also be laid to rest beside them. His burial was officially recorded as the 101103rd interment, just another number in the vast records of the cemetery, but for those who loved him, it was a moment that changed everything. His funeral was simple yet dignified, a reflection of the man he was, humble, hardworking, and loved beyond measure. A polished coffin with brass fittings, lined with robe and ruffle, was a small yet deeply meaningful tribute to a life that had ended far too soon. The cost of the funeral was £14.18, a sum that carried far more weight than mere money, it was the price of heartbreak, the cost of laying a beloved husband, father, and son to rest.

And yet, among those who stood by his graveside, mourning the man they had lost, one person was heartbreakingly absent, his beloved Edith.

We may never truly know why she wasn’t there.

Was it that her body, heavy with the life of the daughter she carried, simply couldn’t bear the strain? Or was it something even deeper, an unbearable truth that she could not bring herself to face? To stand there, to hear the final words spoken over the man who had been her everything, to watch as the earth swallowed the last physical part of him, perhaps it was a pain too cruel, too raw, too impossible to endure.

My heart aches for her, for the agony she must have felt, trapped between grief and survival. In losing Robert, she lost her best friend, her protector, her partner in everything. And yet, she had no time to collapse under the weight of her sorrow. She was left to carry on, to wake each morning and put one foot in front of the other, even as the love of her life lay beneath the earth. She was left to raise their three young sons, John, Frederick, and Godfrey, alone, to be their strength when her own heart was shattered. And soon, she would bring their unborn daughter into a world that no longer held the man who should have been there to meet her.

But even in death, Robert was never truly gone. A part of him lived on in each of their children, in John’s determination, in Frederick’s kindness, in Godfrey’s laughter. And in the baby girl who would never know his touch but would carry his name, Robina Maud Ellen May Wallace.

Through them, he remained. In their eyes, in their voices, in every breath they took, Robert was there. He lived on in the stories they would tell, in the love they would hold for him, in the quiet moments when Edith would close her eyes and swear she could still hear his voice.

Love like theirs does not fade. It does not end at the graveside. It lingers in the echoes of the past, in the warmth of a memory, in the lives of those left behind. And though Edith’s world had been shattered, though she faced a future without the man who had been her everything, one truth remained, Robert would always be with her.

Just two weeks after Edith lost the love of her life, she brought their daughter into the world. On Saturday, the 10th day of October 1925, in the quiet of their home at Number 29, Victory Road, Southampton, Edith gave birth to Robina Maude Ellen Wallace, my husband’s wonderful Nan. A precious new life, carrying the names of both her parents, forever tethered to the father she would never have the chance to meet.

I can only imagine the overwhelming wave of emotions Edith must have felt in that moment. The unbearable grief of losing Robert still so raw, the emptiness beside her where he should have been, and yet, in her arms, a tiny, perfect reminder that love does not end with death. Robina was a piece of Robert left behind, a whisper of him in her soft newborn cries, a trace of his spirit in the delicate curve of her face.

On the 11th day of November 1925, Edith made the lonely journey to register her daughter’s birth in Southampton. The registrar, Sydney William Rolfe, recorded in the birth registry that Robina Maud Ellen May Wallace, a baby girl, was the daughter of Robert McIntyre Wallace, a motor driver, deceased , and Edith Ellen Wallace, formerly Southwell, of Number 29, Victory Road, Southampton.

Seeing the word "Deceased", must have been another cruel cut to her already shattered heart. He should have been there, standing beside her, beaming with pride, his hand resting gently around their newborn daughter’s hand. Instead, she faced this alone, carrying the weight of both grief and new life in equal measure.

Robina grew up never knowing her father’s embrace, never hearing his voice or feeling the warmth of his love firsthand. But she was surrounded by his presence in other ways, through the stories that were told, the memories that were cherished, and the love that never faded. His legacy lived on in her and in her brothers, woven into the very fabric of their lives.

Now, generations later, Robert and Robina’s legacy continues, their blood running through the veins of those who carry their name, their stories, and the love that began with Robert and Edith so many years ago.

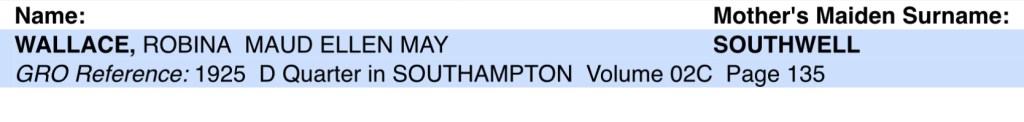

Although our family treasures the original copy of Robina’s birth certificate, it doesn’t feel right to share it. Her passing is still fresh, and she is so deeply missed. But for those wishing to honor her place in our family tree, a copy can be ordered with the following GRO reference information:

GRO Reference: Wallace, Robina Maud Ellen May, Southwell, 1925, December Quarter in Southampton, Volume 02C, Page 135.

This isn’t just a record in an archive; it’s a testament to a love that refused to be extinguished, a love that carried on, even in the face of heartbreaking loss.

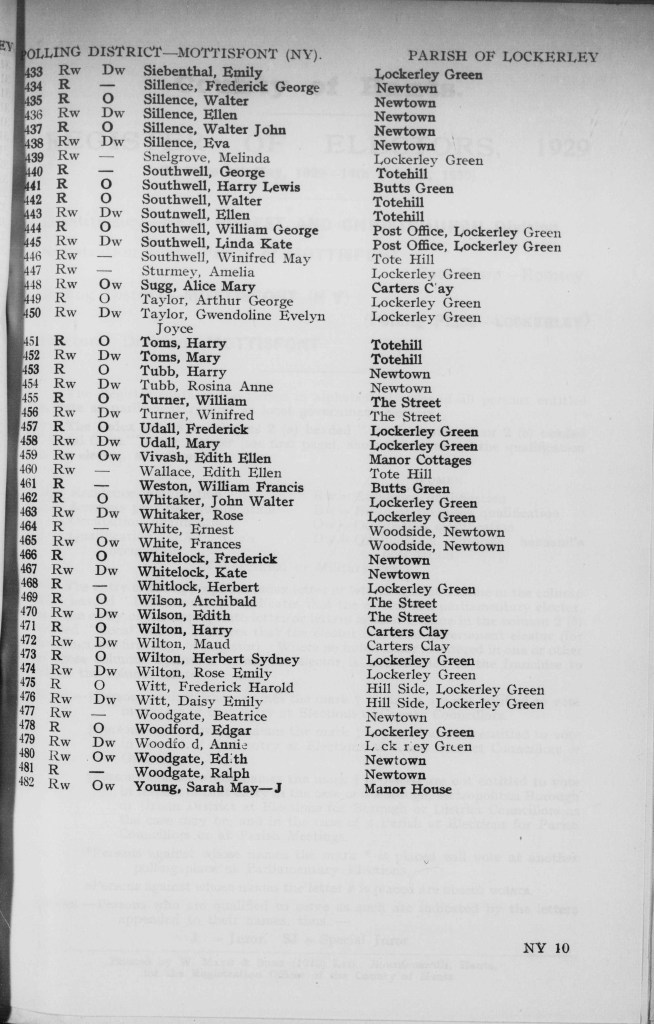

In 1929, the England & Wales Electoral Register recorded Edith residing at Totehill, Lockerley, Romsey, Hampshire, England. It had been four years since she had lost Robert, the love of her life, and in those years, she had endured unimaginable grief while also summoning every ounce of strength to keep going for the sake of her children.

Totehill had been a place of familiarity, a quiet countryside setting where she had once been a young woman full of hope, and now, it was where she worked tirelessly to provide for her family. Though her world had been shattered by loss, Edith carried on, finding ways to navigate life as both mother and father to her little ones. The challenges she faced were no small burden, yet she pressed forward with determination, resilience, and above all, love.

The entry in the Electoral Register is just a brief notation, a name on a list among thousands of others, but behind that simple record is a story of endurance, of a woman who refused to let tragedy define her. Edith’s presence in Totehill in 1929 is a testament to her unwavering strength, her ability to hold her family together even when the weight of loss threatened to consume her.

The 1931, the England & Wales Electoral Register recorded Edith living at Heather Cottage, Sherfield English, Romsey, Hampshire, England. It had been six years since she had lost Robert, and in that time, she had continued to rebuild her life while raising their children alone.

The move to Heather Cottage marked another chapter in her journey, one that must have been filled with both challenges and quiet moments of resilience. Sherfield English, a small rural village, offered a sense of peace, a slower pace of life amidst the rolling Hampshire countryside. Perhaps this change was a necessity, a fresh start, or simply the next step in ensuring her children had a stable home.

Though she had endured so much heartache, Edith remained strong, her determination unwavering. Every decision she made was driven by her love for her children, her need to provide them with the best life possible despite the immense loss they had suffered. Life at Heather Cottage may have been modest, but within its walls was a mother who refused to give up, who carried on despite everything, and who made sure her children knew they were deeply loved.

On Monday, the 1st day of August, 1932, Edith’s beloved sister, Winifred May Southwell, exchanged vows with Percy Alexander East in the Romsey district of Hampshire, England. It was not just the joining of two hearts, but the foundation of a home that would become the very heart of the family for generations to come.

Winifred and Percy’s marriage was built on love, devotion, and an unwavering sense of duty to those they held dear. Together, they became the hub of the family, their home a place of warmth, laughter, and comfort. Percy, a man of quiet strength and boundless generosity, welcomed not only Winifred into his life but also her family, opening both his home and his heart to them. Out of love for his one true love, he embraced Edith and the Southwell family as his own, providing them with support, kindness, and a place where they always belonged.

For those wishing to preserve this special moment in the family’s history, an official copy of their marriage certificate can be obtained using the following GRO Reference information: Marriages, September 1932, Southwell, Winifred M, East, Percy A, Romsey, Volume 2c, Page 289.

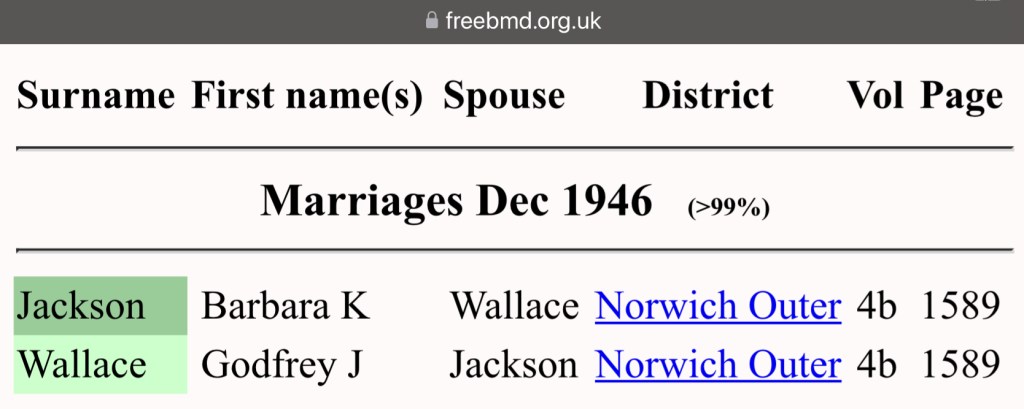

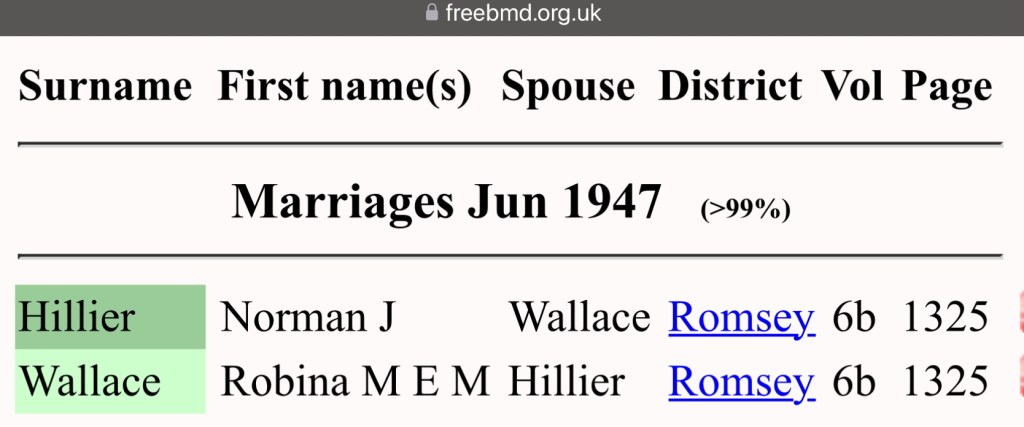

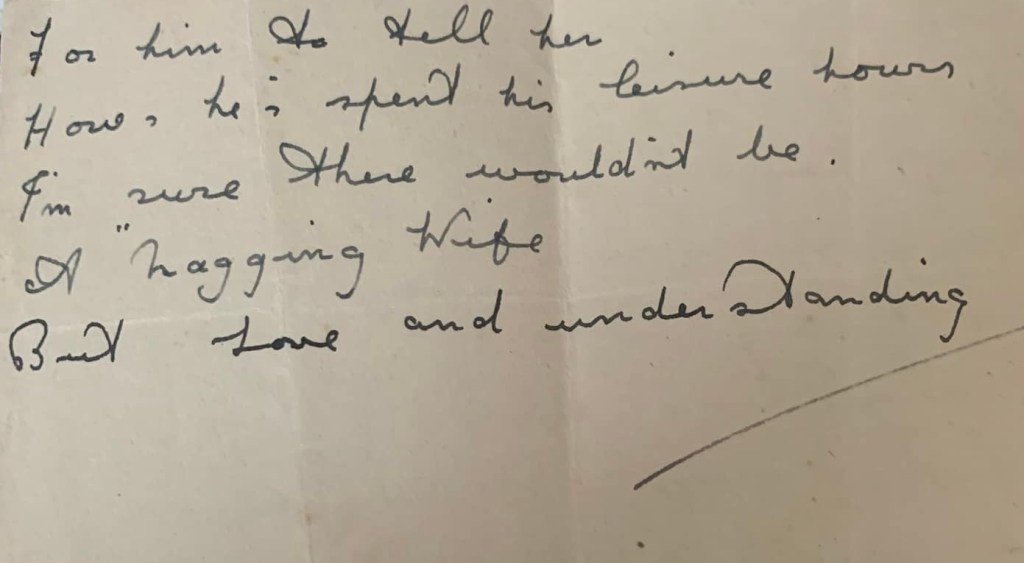

on their wedding day,