In the quiet corners of family attics and the faded pages of dusty albums, lies the essence of a life once lived. The Life of Emily Kate Southwell, 1892–1947, is not just a chronicle of dates and events, but a testament to the enduring power of family history. It is in these fragments of the past that we find the threads of our own existence woven delicately into the tapestry of time.

Exploring the life of Emily Kate Southwell is like embarking on a journey through a forgotten garden, where each flower tells a story and every leaf whispers a secret. Through meticulous documentation, we uncover not just the milestones she crossed, but the laughter shared, the tears shed, and the dreams nurtured in the embrace of loved ones.

Family history is more than names on a pedigree chart; it is a treasure trove of memories that transcends generations. It is the joy of piecing together the fragrance of their lives, a fragrance that lingers long after they have departed this earthly realm. It is in the sepia-toned photographs where smiles freeze in time, and in the letters where emotions leap off the page, that we discover the richness of our heritage.

Join me as we unravel the story of Emily Kate Southwell, a journey that celebrates the beauty of familial bonds and the enduring legacy of a life well-lived. Together, let us honor her memory and cherish the legacy she left behind, for in preserving her story, we preserve a part of ourselves.

So with out further ado, I give you,

The Life Of Emily Kate Southwell,

1892–1947,

Through Documention.

Welcome back to the year 1892, East Wellow, Hampshire, England. The air is crisp, carrying the scent of damp earth and coal smoke, as horse-drawn carts rattle along the winding village roads. This is a time when Queen Victoria sits upon the throne, her reign now deep into its fifth decade, casting a matriarchal presence over the empire. In London, Lord Salisbury leads the Conservative government as Prime Minister, overseeing a nation caught between the old world and the rapid advancements of the new. Parliament remains dominated by the aristocracy and the wealthy elite, though murmurs of social change stir among the working class.

The divide between rich and poor is stark. The upper classes, draped in fine silks, brocades, and tailored suits, glide through grand ballrooms, their evenings illuminated by glittering chandeliers fed by gaslight. Women’s fashion is defined by corseted waists, high necklines, and bustled skirts, while men sport frock coats, waistcoats, and bowler hats. Meanwhile, the working class and poor make do with simpler, more practical garments, rough wool, linen, and hand-me-downs that have seen better days. The wealthy reside in sprawling estates with well-manicured gardens, while the poor cram into overcrowded tenements, struggling to make ends meet.

The streets of London, and even the quieter lanes of Hampshire, are alive with the clatter of horse-drawn omnibuses and the occasional puff of smoke from a steam-powered vehicle, a novelty still rare outside the city. The railway is the backbone of long-distance travel, allowing for a level of mobility unthinkable to previous generations. It is now possible to travel from Hampshire to London in mere hours, rather than days by carriage. Bicycles, still a luxury, are growing in popularity among the adventurous and well-to-do.

Inside homes, warmth comes from open fireplaces, coal and wood fueling the flickering flames that offer relief from the winter chill. The wealthy enjoy gas lighting, while many rural homes and working-class dwellings rely on oil lamps and candles, their dim glow casting long shadows across well-worn wooden tables. In the wealthiest houses, electric lighting is beginning to appear, though it remains unreliable and expensive.

Sanitation is a tale of contrast. In the grand homes of the elite, indoor plumbing and flushing toilets are becoming standard, yet the working-class neighborhoods and countryside cottages still rely on chamber pots and outdoor privies. Streets in urban areas reek of uncollected waste, and disease spreads easily in cramped, poorly ventilated living quarters. Typhoid and cholera remain ever-present dangers, especially among the poor, where access to clean water is limited.

At the dinner tables of the well-off, meals are lavish affairs featuring roast meats, rich sauces, fresh vegetables, and delicacies imported from across the empire, tea from India, sugar from the West Indies, and exotic fruits from far-off lands. In contrast, the working class subsists on bread, potatoes, and whatever cheap cuts of meat can be afforded, often stretched with thick broths and stews. The poorest struggle to feed themselves at all, relying on charity, soup kitchens, and the meager rations provided in the workhouses.

Entertainment in 1892 varies greatly by class. The aristocracy revel in elaborate dinner parties, theatre performances, and evenings of classical music in candlelit drawing rooms. The working class, when they have time to spare, find joy in music halls, public houses, and street performances. Literature is flourishing, with Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes captivating readers, while newspapers are filled with political debates, scandalous court cases, and the latest royal gossip. Across the country, people whisper about the upcoming wedding of Prince George, Duke of York, to Princess Mary of Teck, a future king and queen whose engagement has set society alight.

Beyond the glamour and hardship, history is unfolding. The year sees the passing of Thomas Cook, the pioneer of modern travel, a reminder of how swiftly the world is changing. The Labour Electoral Association is gaining traction, laying the groundwork for the Labour Party, as socialist ideals begin to challenge the rigid class system. In science, Sir James Dewar introduces the vacuum flask, and engineers push the boundaries of possibility with new industrial machinery. In the countryside, life remains tethered to the seasons, with farmers tending to fields much as they have for centuries, even as the encroaching railways bring whispers of modernization.

The year 1892 is one of both tradition and transformation, a world where candlelight meets electricity, horse-drawn carriages share space with steam locomotives, and the voices of the working class begin to rise against the weight of aristocratic rule. It is in this world that Emily Kate Southwell is born, her life destined to unfold amid the great contrasts and quiet revolutions of Victorian England.

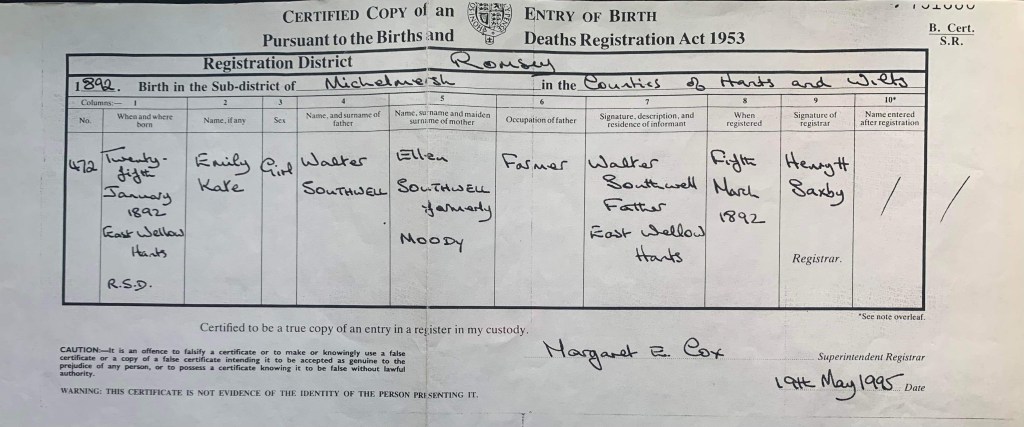

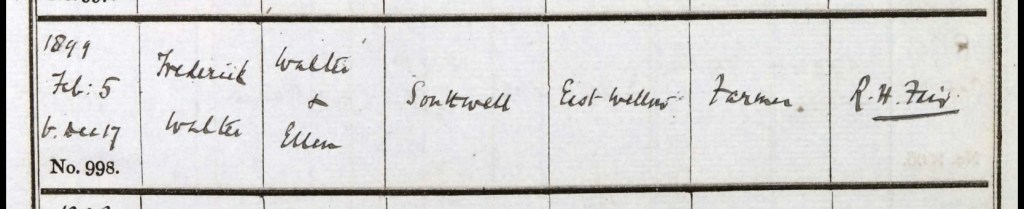

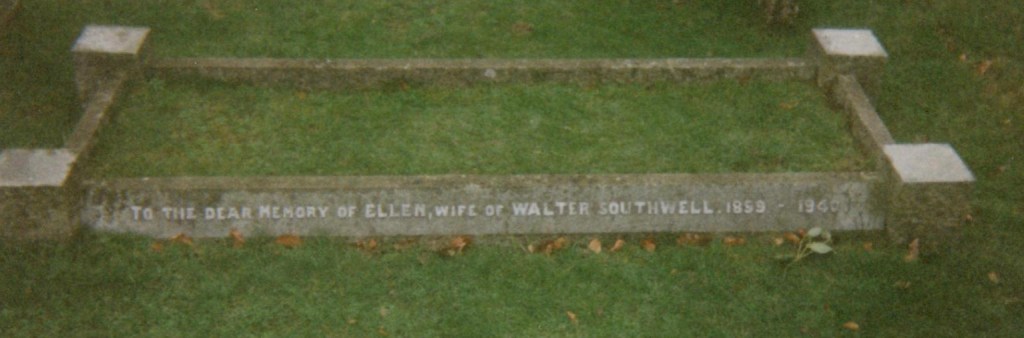

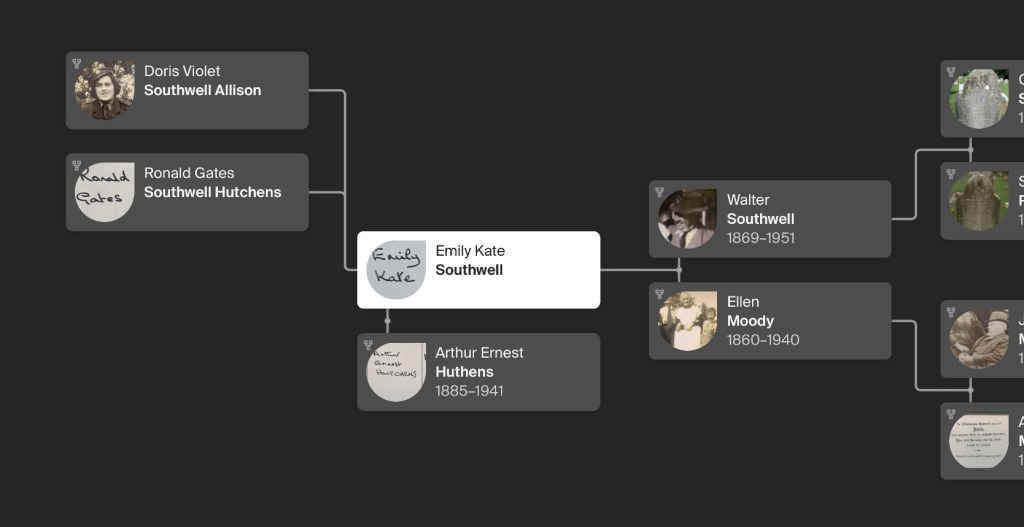

Walter Southwell, a hardworking farmer, and his wife Ellen, formerly Moody, were already raising their firstborn, Alice Annie, when Emily came into the world on a winter’s day, Monday, the 25th day of January in 1892. It was a time when birth was a profoundly domestic affair, attended to by mothers, midwives, and sometimes even neighbors, rather than doctors. The walls of their home had likely already echoed with Alice’s toddler laughter, and now, with Emily’s arrival, the Southwell family grew by another small, precious life.

Five weeks after her birth, Walter made the journey to Romsey, Hampshire, to formally register Emily’s entrance into the world. One can imagine him, perhaps in his best coat and hat, stepping onto the muddy road as he made his way toward the town, leaving behind the quiet homestead for the bustle of Romsey’s streets. At the registrar’s office, Henry Saxby recorded the details, his pen scratching across the heavy parchment as Emily’s name was inscribed into official record, a name that would carry forward through generations.

The surname Southwell carries a long and distinguished history, deeply rooted in England. It originates from the Old English words *sūð* (meaning "south") and *wella* (meaning "spring" or "stream"), indicating that the name likely referred to someone who lived near a southern water source. This type of surname, known as a toponymic name, was commonly given to individuals based on geographical locations.

The name Southwell is most famously associated with the market town of Southwell in Nottinghamshire, a place of historical significance due to Southwell Minster, an important ecclesiastical site dating back to Saxon times. The surname first appears in records as early as the 12th century, and over time, it became tied to notable families, particularly those of noble or gentry status. Some branches of the Southwell family gained prominence through service to the crown, landownership, and religious affairs.

One of the most recognized bearers of the name was Robert Southwell (1561–1595), an English Jesuit priest and poet who was canonized as a Catholic martyr. His writings, particularly his devotional poetry, remain an important part of English literary history. Other members of the Southwell family held positions in the military and government, weaving their legacy into the fabric of England’s past.

The Southwell family crest is rich in symbolism, often featuring heraldic elements that represent strength, loyalty, and noble heritage. A common depiction includes a shield adorned with a distinctive design—frequently with argent (silver) and sable (black) elements, symbolizing sincerity and constancy. Crests associated with the Southwell name have included imagery such as a lion or a bird, signifying courage and vigilance, while decorative flourishes like helmets and mantling indicate knightly or noble standing. Though individual families bearing the name may have had slight variations in their coat of arms, the overarching theme remains one of dignity and resilience.

The surname, while less common today, still carries a sense of history and tradition. Families with the name Southwell can often trace their ancestry back to rural England, where their forebears were farmers, landowners, or stewards of the land, much like Walter Southwell of East Wellow, Hampshire. The name itself is a lasting echo of a time when identity was closely tied to the land one lived on, and to bear the name Southwell is to carry a legacy that stretches back through centuries of English history.

The name Emily, has a long and elegant history, rich with literary and royal associations. It originates from the Latin name Aemilia, which is derived from Aemilius, an ancient Roman family name meaning “rival” or “industrious.” The name gained prominence in England during the 18th and 19th centuries, particularly among the upper and middle classes, where it was favored for its refined and graceful sound.

Emily became widely recognized through literature, most notably with Emily Brontë, the author of Wuthering Heights, whose work and persona embodied the depth and passion often associated with the name. It was also a name linked to Victorian ideals of femininity, gentle yet resilient, strong-willed yet tender-hearted. By the time of Emily Kate Southwell’s birth in 1892, the name had become popular among English families who valued tradition and literary culture.

Though the name Emily does not have a single family crest associated with it, the meaning of industrious and striving suggests heraldic symbols such as the bee, representing hard work and perseverance, or the laurel wreath, symbolising victory and achievement. Those who bore the name Emily were often seen as intelligent and capable, embodying a quiet strength and determination.

The name Kate, a timeless and beloved name, has origins in the Greek name Aikaterine, thought to mean “pure.” It is a diminutive of Katherine, a name carried by saints, queens, and literary heroines alike. One of its most famous associations is Saint Catherine of Alexandria, a revered figure of wisdom and virtue.

In England, Kate was often used as an affectionate form of Katherine and became a standalone name in its own right, beloved for its simplicity and charm. During the 19th century, it was common for Victorian families to choose names with classical and biblical significance, making Kate a fitting and elegant choice. It exudes a sense of warmth, yet there is an underlying strength to it, much like its literary counterpart in Shakespeare’s *The Taming of the Shrew*, where the character Katherina (Kate) is portrayed as both fiery and independent.

Like Emily, Kate does not have a direct heraldic crest, but names associated with purity and nobility often feature symbols such as lilies, which represent innocence and virtue, or stars, which symbolize guidance and protection. The name Kate carries with it a history of strong, intelligent, and determined women, making it a fitting choice for a girl born into a hardworking farming family in the Victorian era.

Together, Emily Kate is a name full of meaning, a combination of industriousness and purity, resilience and grace. It reflects both strength and refinement, making it a name well-suited to a life of quiet determination and enduring legacy.

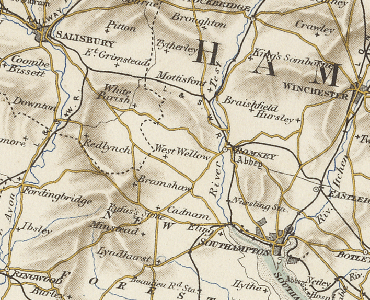

Wellow, Hampshire, is a place of quiet charm and deep-rooted history, nestled in the rolling countryside of southern England. Divided into East Wellow and West Wellow, this rural parish lies near the market town of Romsey, with its winding lanes, fields, and ancient woodlands forming a landscape that has changed little over the centuries. It is a place where the past lingers in the air, carried on the breeze through oak and ash trees, where the old ways of life, farming, village gatherings, and church bells tolling, still echo through time.

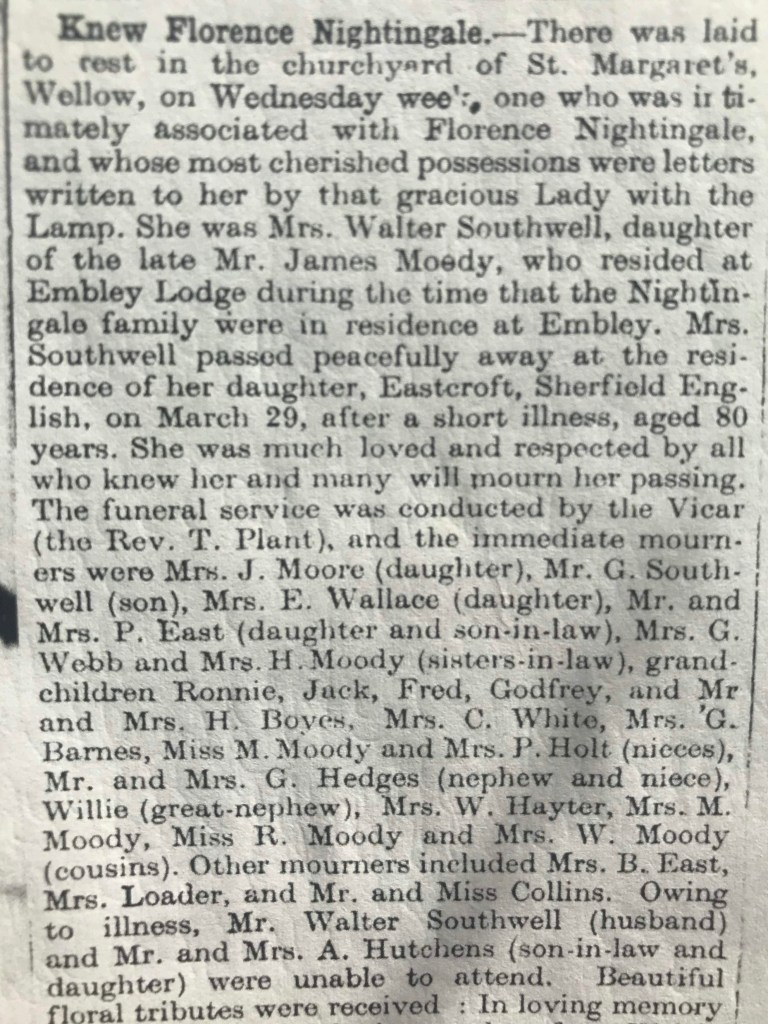

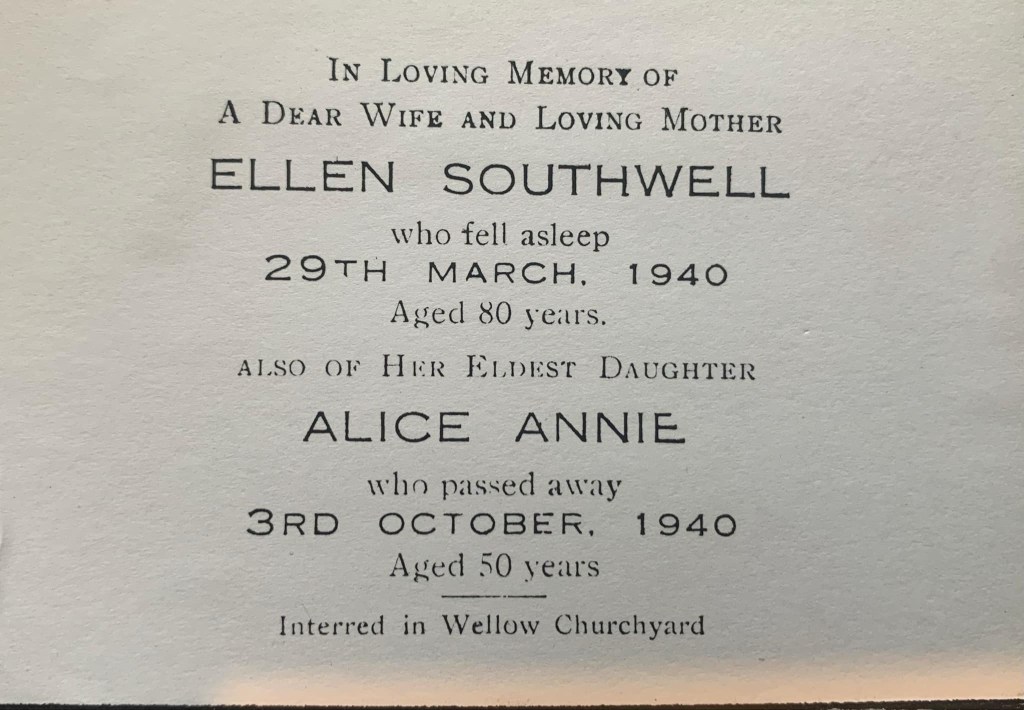

East Wellow, the smaller of the two settlements, holds a special significance in English history, most notably as the resting place of Florence Nightingale, the famed nurse and social reformer. Her grave lies in the churchyard of St. Margaret’s Church, a modest but beautiful parish church with a history stretching back to medieval times. The church itself, built of local stone, is a testament to the village’s long-standing Christian heritage, serving as a spiritual anchor for generations of families, including those like the Southwells, who worked the land and built their lives in the region.

The history of Wellow extends deep into England’s past. Before the Norman Conquest of 1066, the area was likely settled by the Saxons, who carved out small farming communities along the banks of the local streams and rivers. The Domesday Book of 1086, a great survey commissioned by William the Conqueror, records the land of Wellow under the holdings of a Norman lord, reflecting the shift in power and landownership following the conquest. Over the centuries, Wellow remained an agricultural settlement, with its economy centered around farming, livestock, and the dense woodlands that provided timber and fuel.

During the medieval period, the lands of Wellow were tied to local lords and monastic estates, with villagers working as tenants, laborers, or skilled tradesmen. The open fields and common pastures, still visible in the gentle undulations of the landscape, hint at a time when agriculture followed the traditional strip-farming system, with families cultivating narrow plots of land to sustain themselves.

By the 19th century, when Emily Kate Southwell was born, East Wellow was a small but thriving rural community, its inhabitants largely farmers, agricultural workers, and tradespeople. Life followed the rhythm of the seasons, planting in spring, tending to crops and livestock in summer, harvesting in autumn, and enduring the cold, dark months of winter by the warmth of the hearth. Though the industrial revolution had brought great changes to the cities, places like East Wellow remained deeply connected to the land, where horses still pulled plows, and village life revolved around the local church, school, and market towns like Romsey.

Travel between Wellow and nearby towns was possible by foot, horse, or the occasional cart, with Romsey serving as a vital hub for trade, supplies, and social interaction. The arrival of the railway in Hampshire had begun to transform rural life, allowing for quicker movement of goods and people, but in places like East Wellow, the old ways endured.

The people of East Wellow lived simple but hardworking lives. Homes were built from local materials, often small cottages with thatched roofs, wooden beams, and stone or brick chimneys where fires burned to keep out the damp. Water was drawn from wells or local streams, and sanitation remained rudimentary, with outdoor privies and hand-pumped water sources being common.

The landscape of Wellow was and remains beautiful, with open fields, wooded groves, and winding country paths. The nearby New Forest, a historic royal hunting ground, stretches to the southwest, offering an expanse of ancient woodland, heathland, and pastures where wild ponies still roam freely, much as they have for centuries.

Throughout its history, Wellow has maintained its strong sense of identity, shaped by the land, the people, and the traditions that endure. For families like the Southwells, it was a place of both toil and comfort, where each generation left its mark upon the soil, the village, and the ever-turning wheel of rural English life.

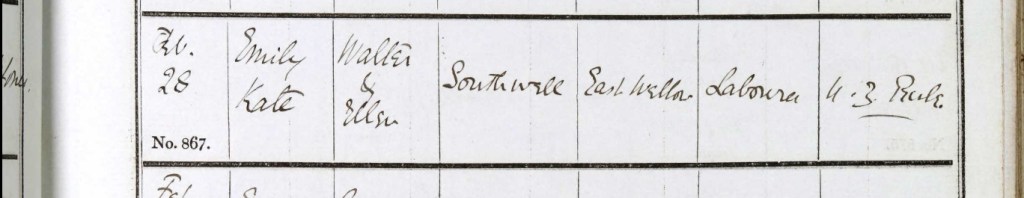

On Sunday, the 28th day of February, 1892, in the quiet village of East Wellow, Walter and Ellen Southwell carried their infant daughter, Emily Kate, to Saint Margaret’s Church to be baptized. The morning air would have been crisp, the fields still touched with winter’s lingering frost, as family and neighbors gathered beneath the weathered stone walls of the ancient church.

Saint Margaret’s Church, standing for centuries as a place of worship and community, was the heart of East Wellow. Its modest yet dignified architecture, built of local stone, bore witness to countless generations who had come before, farmers, laborers, and villagers who had lived and died within the embrace of this rural parish. The Southwells were among them, a hardworking family whose roots were firmly planted in the Hampshire soil.

Inside the church, beneath the wooden beams and flickering candlelight, the vicar, J.E. Winters, performed the sacred rite. He recorded in the parish baptismal registry that Emily Kate Southwell, daughter of Walter and Ellen, resided in East Wellow. Walter’s occupation was noted simply as “Labourer,” a reflection of the daily toil he endured to provide for his family. It was an honest and humble existence, one of hard work in the fields, tending the land, and ensuring there was enough food on the table.

Baptism in the 19th century was more than a religious ceremony; it was a moment of belonging, a rite of passage that connected a child not only to God but to the wider community. In a time when infant mortality was still a stark reality, baptisms were often carried out within weeks of birth, offering both spiritual protection and a formal place in the records of the parish. The Southwells would have stood before the congregation, solemn yet proud, as their daughter was welcomed into the Church of England.

For Emily, this moment marked the beginning of her journey, a life that would unfold within the rhythms of country living, shaped by the land, the seasons, and the quiet, steadfast faith of the village. The sound of the church bells, the same ones that rang out for baptisms, weddings, and funerals, would echo through her childhood, weaving a connection between past and present, between the family that raised her and the village that would always be her home.

Saint Margaret’s Church, standing in the heart of East Wellow, Hampshire, is a place of deep historical and spiritual significance, its weathered stone walls bearing witness to centuries of faith, tradition, and village life. Surrounded by ancient yew trees and a peaceful churchyard, it is a church that has watched over generations of families, offering comfort in times of joy and sorrow.

The church dates back to at least the 13th century, though it is likely that a place of worship existed here even earlier, serving the rural communities that worked the land. Built from local stone, its simple yet dignified structure reflects the medieval craftsmanship of the time. The tower, sturdy and square, rises modestly above the Hampshire countryside, a landmark for villagers and travelers alike. The wooden beams inside, darkened with age, tell their own silent stories of the countless prayers whispered beneath them.

Saint Margaret’s is most famously known as the final resting place of Florence Nightingale, the legendary nurse and social reformer whose work in the Crimean War transformed modern healthcare. She chose to be buried in the quiet churchyard of East Wellow rather than in Westminster Abbey, preferring the simplicity and humility of her family’s connection to the village. Her grave, marked by a modest cross, draws visitors from around the world who come to pay their respects to the woman who revolutionized nursing.

Beyond its association with Florence Nightingale, Saint Margaret’s has long been the spiritual home of the local farming and laboring families of East Wellow. For centuries, its font has welcomed newborns into the faith, its pews have held parishioners during Sunday services, and its bells have tolled for the departed. The Southwell family, like many others, would have gathered here regularly, their footsteps echoing on the worn stone floor as they joined in hymns and prayers.

The church registers, carefully maintained over the centuries, hold the names of those who lived, loved, and passed on in East Wellow, their stories preserved in ink and parchment. For the Southwells, it was here that Emily Kate was baptized in 1892, following the same sacred tradition as her ancestors before her. The vicar, J.E. Winters, would have stood at the font, his voice steady as he performed the ancient rite, welcoming another soul into the life of the church.

Time moves slowly in a place like Saint Margaret’s. The seasons shift, the ivy grows along its walls, and the headstones in the churchyard continue to weather under the changing skies. Yet, through it all, the church remains, a quiet guardian of history, faith, and the enduring spirit of the village it serves.

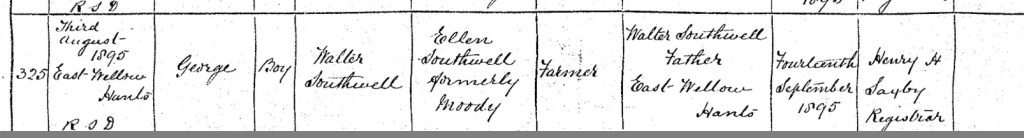

On a warm summer’s day, Saturday, the 3rd day of August, 1895, in the quiet village of East Wellow, Hampshire, Ellen Southwell gave birth to a son. The Southwell home, already filled with the sounds of young Alice Annie and Emily Kate, now welcomed another child, George Southwell. The arrival of a new baby was always a moment of both joy and responsibility in a rural farming family, where every member played a role in the household’s survival and prosperity.

Walter Southwell, now recorded as a farmer rather than a laborer, had worked hard to provide for his growing family. Life in East Wellow revolved around the land, the changing seasons dictating the daily rhythms of planting, harvesting, and tending to livestock. By the time George was born, Walter may have secured more stability in his work, a sign that his standing within the local farming community had improved.

A month after George’s birth, on Wednesday, the 4th day of September, Walter made the familiar journey to Romsey to officially register his son’s arrival. The registrar, Henry H. Saxby, recorded the details carefully, George Southwell, a boy, born to Walter and Ellen in East Wellow. These moments of official record-keeping, though routine, were significant milestones in a child’s life. They placed the new generation firmly within the history of the parish, ensuring that George’s name would be carried forward in both family memory and formal documentation.

For the Southwell household, George’s birth meant another pair of hands that would one day help with the demands of farm life. As he grew, he would learn to navigate the fields, care for animals, and take part in the daily labor that sustained his family. His sisters, Emily and Alice, would have known him first as a small baby in the cradle, but in time, he would become their companion in childhood, running through the meadows and playing in the shadow of Saint Margaret’s Church, just as generations of village children had done before.

George’s arrival marked another chapter in the Southwell family’s story, one written not in grand events, but in the quiet, steady continuity of rural life, a life rooted in family, faith, and the land they called home.

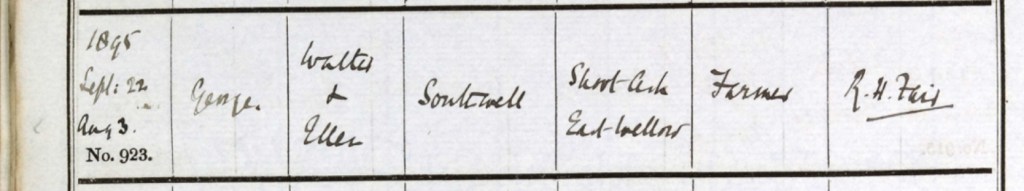

On Sunday, the 22nd day of September, 1895, Walter and Ellen Southwell carried their infant son, George, to Saint Margaret’s Church in Wellow to be baptized. The church bells rang out across the quiet Hampshire countryside as family and neighbors gathered to witness this sacred rite, marking George’s formal entry into the church and community. It was a familiar and comforting tradition, one that had been carried out for generations within the ancient walls of Saint Margaret’s, where the font had welcomed countless children before him.

The vicar, R. H. Fair, stood at the stone font as he gently poured the baptismal waters over the child’s forehead, speaking the solemn words of blessing and commitment. In the parish register, he recorded that George’s father, Walter, was a farmer, and that the family now resided at Shot Ash, Wellow. The shift in location from East Wellow to Shot Ash reflected a new chapter for the Southwells, possibly a move to a different farm or cottage, but still within the close-knit bounds of their rural parish.

Baptism in 19th-century England was far more than a ceremonial moment. It was a rite of belonging, welcoming the child not just into the Christian faith, but also into the village itself. In small communities like Wellow, church records held great significance, documenting each birth, marriage, and passing, preserving the lives of ordinary people for generations to come.

For Walter and Ellen, this day would have been one of both faith and hope. As they stood before the congregation with their infant son in their arms, they reaffirmed their place within the parish of Saint Margaret’s, continuing the traditions of their forebears. The Southwell name, inscribed once more in the church’s registry, was woven deeper into the fabric of Wellow’s history.

Outside the church, the late September air carried the first hints of autumn. The golden fields and hedgerows turning with the season bore witness to the cycle of life, birth, growth, and renewal. For young George, his baptism was the quiet beginning of a journey that would unfold within this familiar landscape, among family, faith, and the ever-present rhythm of country life.

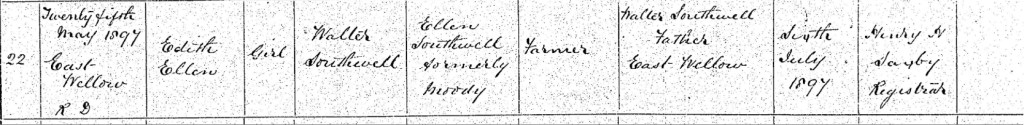

As the warm days of late spring settled over the Hampshire countryside, a new life entered the world in the quiet village of East Wellow. On Tuesday, the 25th day of May, 1897, Ellen Southwell, already a devoted mother to three young children, gave birth to a daughter in the family home. The cries of the newborn filled the modest farmhouse, marking the arrival of Edith Ellen Southwell, another child to grow up beneath the vast skies and rolling fields of rural Hampshire.

For Walter and Ellen, this birth was another blessing, another small soul to nurture and guide through the rhythms of country life. The family’s days were filled with the endless work of farming, tending crops, caring for livestock, and keeping the household running, but in the midst of labor, there was joy in new beginnings. Edith’s older siblings, Alice Annie, Emily Kate, and George, would soon come to know her as their little sister, a new companion in childhood adventures and daily chores.

A few weeks later, on Tuesday, the 6th day of July, 1897, Walter Southwell made the familiar journey to Romsey to officially register Edith’s birth. Nearly four miles from East Wellow, Romsey was the nearest market town, its bustling streets and historic abbey offering a contrast to the quiet farmlands surrounding it. At the registrar’s office, Henry H. Saxby recorded the details in the official registry, Edith Ellen Southwell, born on the 25th of May, daughter of Walter and Ellen Southwell of East Wellow. Walter, now firmly established as a farmer, signed his name, ensuring that Edith’s place in history was preserved in ink and record.

Life for the Southwell family continued much as it always had, shaped by the cycles of nature and the close ties of a small village community. Edith would grow up surrounded by the familiar sights and sounds of East Wellow, the ringing bells of Saint Margaret’s Church, the rustling of wheat in the summer breeze, the distant calls of cattle in the pastures. Hers would be a childhood spent among the hedgerows and meadows, learning the ways of country life alongside her siblings, each season bringing its own lessons and joys.

With her birth recorded and her name now part of the family’s growing story, Edith Ellen Southwell became another thread woven into the rich tapestry of the Hampshire countryside, a daughter of the land, of tradition, and of the enduring Southwell legacy.

On Sunday, the 20th day of June, 1897, beneath the warm light of the early summer sun, Walter and Ellen Southwell carried their newborn daughter, Edith Ellen, to Saint Margaret’s Church in East Wellow to be baptized. The church, with its weathered stone walls and ancient yew trees standing watch over the graveyard, had already welcomed the Southwell children before her, and now it was Edith’s turn to be brought before the font to receive the sacred blessing.

The vicar, R. H. Fair, stood in his robes at the baptismal font, his voice steady as he performed the time-honored rite. The baptismal waters touched Edith’s forehead, a symbol of her entrance into the Christian faith, her name spoken aloud and recorded in the parish register alongside generations of villagers before her. In that book, Vicar Fair noted Walter’s occupation was a farmer, and their residence was in East Wellow, affirming the family’s deep-rooted connection to the land and parish.

For Walter and Ellen, this was a day of faith and tradition, of gratitude for the safe arrival of their daughter and the hope that she would grow strong under God’s protection. Their three older children, Alice Annie, Emily Kate, and George, may have stood nearby, watching as their baby sister was formally welcomed into the church that had long been the heart of their community.

Baptisms in small country parishes were more than religious milestones, they were also moments of gathering, where neighbors, friends, and extended family came together to celebrate. Perhaps afterward, the Southwells joined others outside in the churchyard, where the scent of summer flowers filled the air, and quiet conversations were shared beneath the shade of old trees.

For Edith, though she would not remember this day, it marked the beginning of a life deeply intertwined with East Wellow, the village of her birth, the land that would shape her, and the church that would remain a constant presence throughout the years to come.

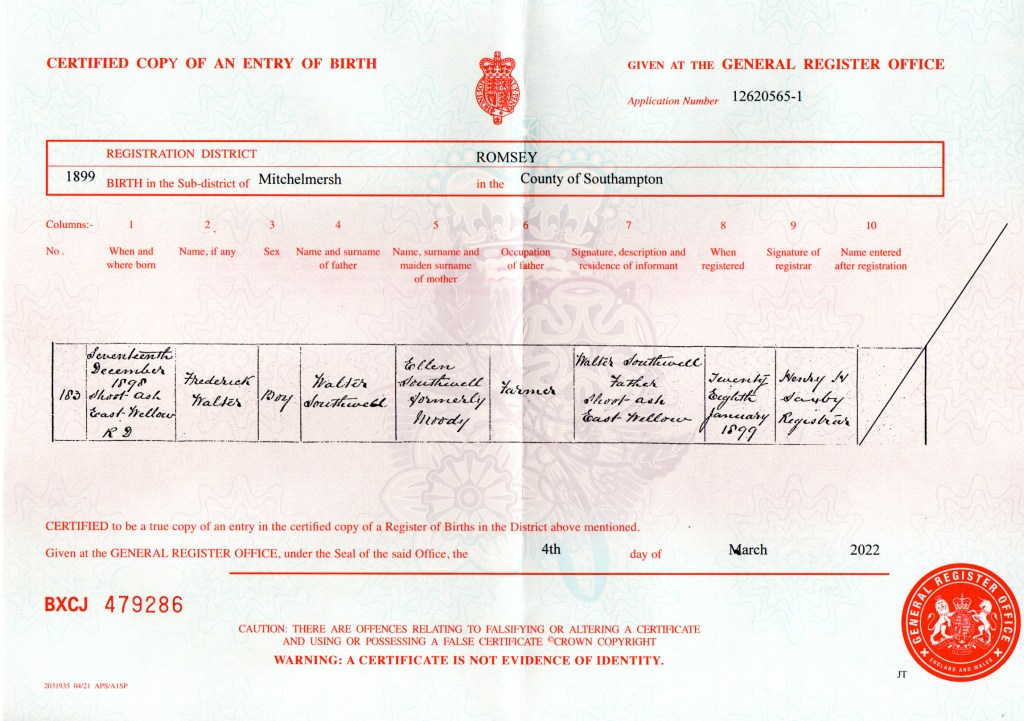

On a winter’s day, Saturday, the 17th day of December, 1898, in the quiet hamlet of Shootash, East Wellow, Ellen Southwell gave birth to her fifth child, a son named Frederick Walter Southwell. The December air would have carried the scent of damp earth and woodsmoke, as fires burned steadily in hearths to keep the winter chill at bay. Within the Southwell home, nestled among the rolling Hampshire countryside, the family welcomed another child into their growing household.

Frederick’s birth came at the close of the 19th century, a time of both tradition and change. Rural life in Hampshire remained deeply rooted in farming, and Walter Southwell, now well-established as a farmer, worked tirelessly to provide for his family. The days were long and often unforgiving, dictated by the land and the seasons, but there was stability in it, a life governed by routine, faith, and community. Frederick would be raised in this world, growing up alongside his older siblings, Alice Annie, Emily Kate, George, and Edith Ellen, each of whom would help shape his earliest years.

It was more than a month later, on Saturday, the 28th day of January, 1899, that Walter made his way to Romsey to officially register his son’s birth. The journey, nearly four miles from Shootash, was one he had taken before, a necessary formality that ensured Frederick’s name was recorded in the official registry. At the registrar’s office, Henry H. Saxby carefully inscribed the details, Frederick Walter Southwell, a boy, born on the 17th of December, 1898, in Shootash, East Wellow. Walter, a farmer, and his wife Ellen, formerly Moody, were listed as his parents, cementing Frederick’s place within the records of Hampshire’s rural history.

Frederick’s early years would be spent among the fields and hedgerows of East Wellow, where he would come to know the rhythms of country life, the golden fields of summer, the scent of cut hay, the quiet hum of bees in the orchards. He would grow up beneath the watchful eye of Saint Margaret’s Church, where generations of his family had been baptized, married, and laid to rest. His childhood would be one of simple joys and hard lessons, surrounded by the love of his family and the ever-present embrace of the Hampshire countryside.

On Sunday, the 5th day of February, 1899, with the lingering chill of winter still in the air, Walter and Ellen Southwell carried their infant son, Frederick Walter, to Saint Margaret’s Church in East Wellow to be baptized. The ancient church, its stone walls standing firm against the passing of time, had already been the site of many important moments in the Southwell family’s life. Now, beneath its arched beams and flickering candlelight, another chapter was about to be written.

The minister, R. H. Fair, stood at the baptismal font, a familiar presence to the Southwell family, having baptized their other children before. With solemnity and grace, he performed the sacred rite, gently anointing Frederick Walter with the baptismal waters, welcoming him into the church and the faith that had long been a cornerstone of village life. His steady hand recorded the event in the parish registry, noting Walter’s occupation as a farmer and the family’s residence in East Wellow.

Baptisms in small country parishes were not just religious ceremonies; they were also community gatherings, moments when neighbors and family came together to celebrate new life. Perhaps after the service, Walter and Ellen lingered in the churchyard, exchanging kind words with fellow parishioners, while little Frederick was passed from one loving set of hands to another. His older siblings, Alice Annie, Emily Kate, George, and Edith Ellen, may have stood nearby, watching with curiosity as their baby brother was formally welcomed into the same church that had been a part of their own lives since birth.

For Frederick, this day would fade into memory, but its significance would remain. He was now part of a tradition stretching back through generations, bound not only by blood but by faith and the land that had sustained his family for so long. Saint Margaret’s, with its ancient yews and weathered headstones, stood as a silent witness to it all, holding within its walls the names and stories of those who had come before him and, in time, those who would come after.

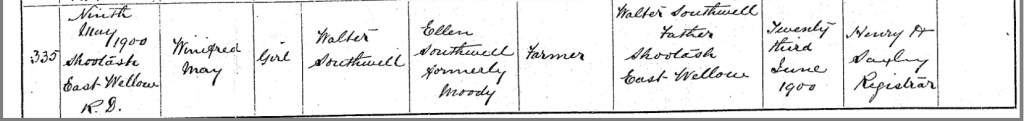

As spring turned to summer in the year 1900, the Southwell family of Shootash, East Wellow, welcomed another child into their home. On Wednesday, the 9th day of May, Ellen Southwell gave birth to a daughter, whom she and Walter named Winifred May Southwell. The arrival of a new baby was always a time of both joy and adjustment, especially in a growing farming family where each child would one day take their place in the rhythms of rural life.

The Southwell home, nestled among Hampshire’s rolling fields and quiet lanes, would have been filled with the familiar sounds of daily farm work, the lowing of cattle, the rustle of wind through the hedgerows, the clatter of tools against wood and stone. Winifred was born into this world of simple, steady labor, where her older siblings, Alice Annie, Emily Kate, George, Edith Ellen, and Frederick Walter, had already begun to learn the ways of country life. For now, though, she was a tiny new presence in the family, swaddled against the lingering cool of early May, cradled in her mother’s arms.

It was on Saturday, the 23rd day of June, 1900, that Walter Southwell made his way once more to the bustling market town of Romsey to formally register his daughter’s birth. At the registrar’s office, Henry H. Saxby recorded the details: Winifred May Southwell, a girl, born on the 9th of May in Shootash, East Wellow, to Walter Southwell, a farmer, and his wife, Ellen, formerly Moody. Walter’s signature, a familiar one in the registry by now, confirmed that another Southwell child had been added to the family records, another thread woven into the history of their Hampshire home.

Winifred would grow up in the same countryside that had shaped her siblings, running through meadows in summer, walking to Saint Margaret’s Church on Sundays, and learning the value of hard work alongside her family. Her name, chosen with care, carried the promise of a future among the fields and woodlands of East Wellow, a life rooted in tradition, community, and the enduring legacy of the Southwell name.

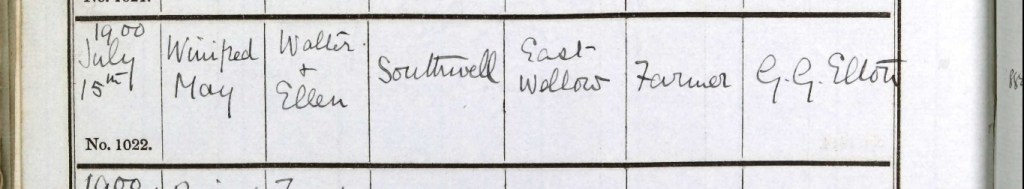

On Sunday, the 15th day of July, 1900, beneath the warm embrace of the summer sun, Walter and Ellen Southwell brought their infant daughter, Winifred May, to Saint Margaret’s Church in Wellow to be baptized. The church, with its sturdy stone walls and ancient yew trees, had already been the site of so many family milestones, and on this day, another was about to be added to its long history.

The minister, G. G. Elliot, stood at the baptismal font, ready to perform the sacred rite that had welcomed generations of villagers into the Christian faith. As he poured the baptismal waters over Winifred’s tiny forehead, he spoke the traditional words of blessing, marking her formal entry into both the Church and the close-knit community of East Wellow. In the parish register, he carefully recorded the details: Walter Southwell, a farmer, and his family residing in East Wellow.

For Walter and Ellen, this moment was one of quiet gratitude, a time to reflect on the gift of their youngest daughter and to reaffirm their family’s deep connection to the church that had stood for centuries at the heart of their village. Perhaps Winifred’s older siblings, Alice Annie, Emily Kate, George, Edith Ellen, and Frederick Walter, watched from the pews, their eyes fixed on the solemn proceedings, each of them once having been cradled at that very font.

After the ceremony, the family may have lingered in the churchyard, exchanging kind words with neighbors and friends beneath the shade of the old yew trees. The warm July air carried the scent of summer flowers, and the sounds of birdsong and distant farm work reminded them all of the ever-turning wheel of life in the Hampshire countryside.

For little Winifred May, this day would not be one she would remember, but it was one that would shape her. Baptized within the same stone walls as her siblings before her, she had been given her place within the community, her name now forever inscribed in the records of Saint Margaret’s Church, a daughter of East Wellow, of faith, and of the enduring Southwell family.

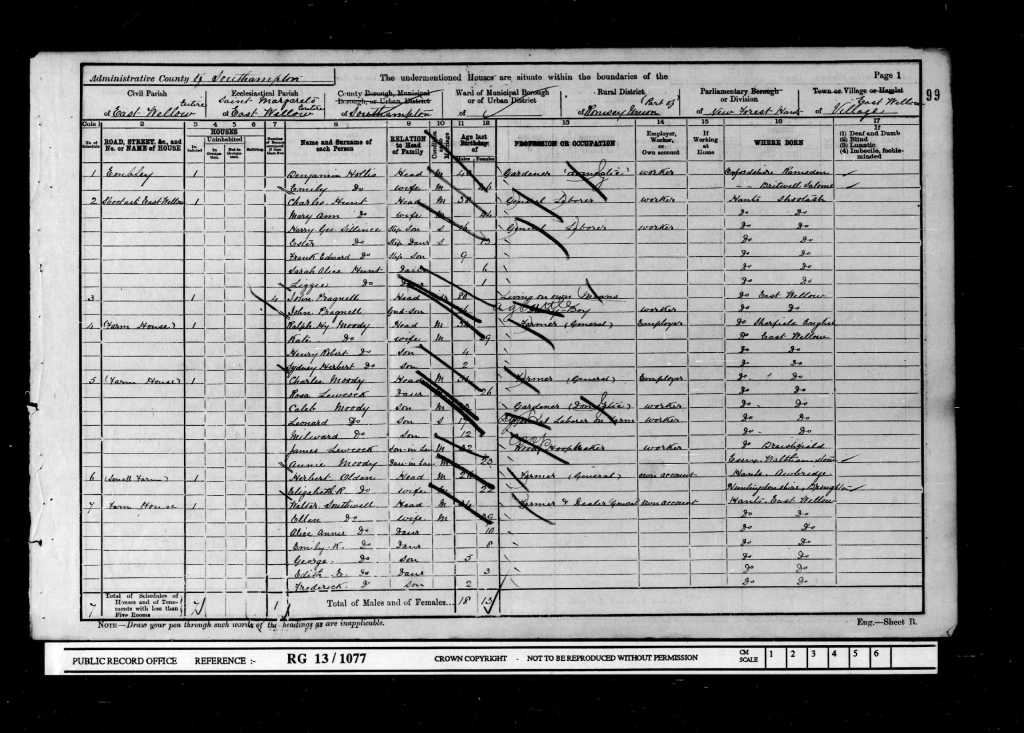

Within the walls of their family home, Walter and Ellen Southwell were raising six children, Alice Annie, Emily Kate, George, Edith Ellen, Frederick, and baby Winifred May. Their lives were deeply tied to the land, as reflected in Walter’s occupation. The census recorded him as a self-employed farmer and general dealer, a testament to the hard work and resilience required to manage both a farm and a business. It was no small task, but Walter had built a livelihood that sustained his growing family, ensuring that his children would know both the joys and demands of country life.

The farmhouse in East Wellow would have been filled with the comforting sounds of a busy home: the crackling of the hearth, the quiet murmur of evening conversation, and the rustle of papers as the census form was completed. Each name and detail inscribed on the document captured a moment in time, Emily Kate, along with her siblings, all listed as "born in East Wellow, Hampshire," firmly anchoring them to their rural roots.

Beyond the Southwell home, the world was changing. Queen Victoria had passed away just months earlier, in January 1901, and a new era had begun under King Edward VII. But in places like East Wellow, life continued much as it always had, dictated by the cycles of the seasons rather than the shifting tides of politics and industry.

For Emily Kate and her siblings, childhood in the farmhouse meant a life shaped by nature, family, and community. Days spent roaming the fields, helping with chores, attending Saint Margaret’s Church on Sundays, and learning the rhythms of farm life would have defined their upbringing. The census, though merely a snapshot in time, confirmed their place in this world, a family bound together by love, hard work, and the rich soil of East Wellow.

By the time the 1911 census was completed on Sunday, the 2nd of April, Emily Kate Southwell was a young woman of nineteen, still living at home with her family, though life had changed significantly since their days at the farmhouse in East Wellow. The Southwells had moved to a more modest four-room home at Tote Hill, Lockerley, Romsey, Hampshire, a shift that reflected not only a change in location but also in lifestyle. Walter, now forty-two, had transitioned from farming to working as a dealer of homely and garden produce, while fifteen-year-old George was already stepping into the world of work as a grocer’s assistant.

It was Emily’s mother, Ellen, at forty-one years old, who took great care in filling out the census return, a task that, for the first time in history, was to be completed by householders themselves rather than by an enumerator. With a steady hand, she wrote down the details of their family, noting with evident pride that she and Walter had been married for twenty-one years and that all six of their children were still living. It was a quiet but significant statement, a testament to the health and endurance of their family in a time when childhood mortality was heartbreakingly common.

While Emily and her younger siblings, fourteen-year-old Edith, twelve-year-old Frederick, and eleven-year-old Winifred, remained at home, her eldest sister, Alice Annie, was spending census night in Romsey. She was visiting the home of Mr. George Moore on Bell Street, the very household where her future husband and his family lived. Though it was merely one night in the records, it was a glimpse into the next stage of her life, the beginning of her transition from daughter to wife, from Southwell to Moore.

There is something deeply intimate about the 1911 census, not just because it captures a moment in time but because it does so in the handwriting of those who lived it. Ellen’s script, clear, precise, and carefully written, is more than just ink on paper. It is a reflection of her character, of the care she put into her family’s records, a tangible piece of her presence that endures more than a century later.

In an era where letters were still the primary form of communication, handwriting was deeply personal. A letter arriving at the door, recognized by the familiar slant of a loved one’s writing, carried a warmth that emails and text messages could never quite replicate. Today, as handwriting becomes less common, replaced by keyboards and screens, we lose something of that personal touch, that quiet art of communication that once connected people across time and distance.

But here, in the 1911 census, Ellen’s hand speaks across the years, telling us not just who the Southwells were, but reminding us of the beauty in a handwritten word, the love that goes into carefully filling out a family’s story, and the significance of preserving the past for those yet to come.

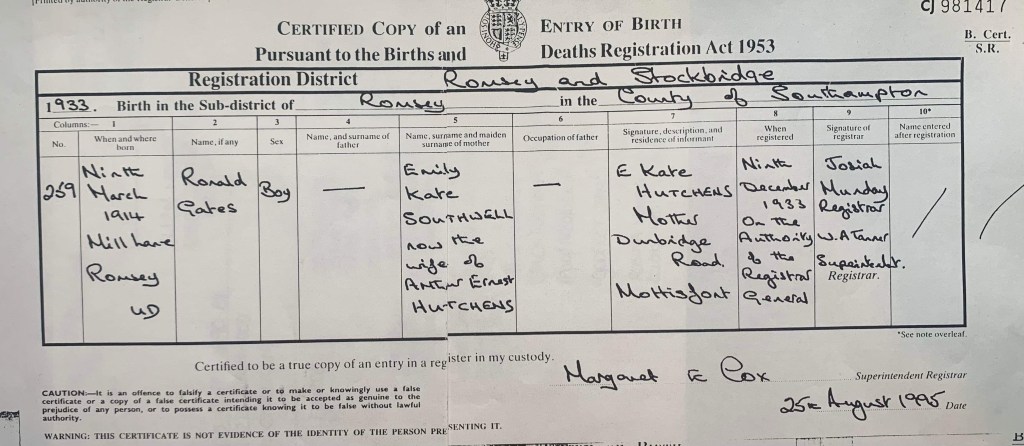

Emily’s son, Ronald Gates Southwell, known affectionately as Ronnie, was born on Monday, the 9th day of March, 1914, at Mill Lane, Romsey, Hampshire. His mother, Emily Kate Southwell, welcomed him into the world under circumstances that remain somewhat shrouded in mystery, as no father’s name was recorded at the time of his birth.

For reasons known only to Emily, Ronnie’s birth went unregistered for nearly two decades. Perhaps it was due to the challenges she faced as an unmarried mother in Edwardian England, a time when societal expectations weighed heavily on women in her position. It may have been an attempt to protect her son from stigma or simply a reflection of difficult personal circumstances. Whatever the reason, it was not until Saturday, the 9th day of December, 1933, that Emily, by then the wife of Arthur Ernest Hutchens, formally registered her son’s birth.

On the authority of the Registrar General, the event was finally recorded in the birth registry with two officials in attendance, registrar Josiah Munday and superintendent registrar W.A. Tanner. The entry stated that Ronald Gates had been born to E. Kate Hutchens, formerly Southwell, on the 9th day of March, 1914, at Mill Lane, Romsey. By that time, Emily’s address was listed as Dunbridge Road, Mottisfont, where she lived with Arthur, her husband.

The delay in registration raises many questions about the complexities of Emily’s life during those years. Was Ronnie raised by his mother alone, or was he cared for by extended family? Did Emily wait to register his birth until she had the security of marriage? Whatever the case, the late registration cemented his place in official records, ensuring that his birth though long unrecorded was finally acknowledged.

Ronnie’s early years must have been shaped by the quiet resilience of his mother, who navigated life’s challenges with strength and determination. Though the details of his upbringing remain elusive, one thing is certain he was deeply loved. His name, chosen with care, would carry forward as part of the Southwell story, a testament to the endurance of family bonds.

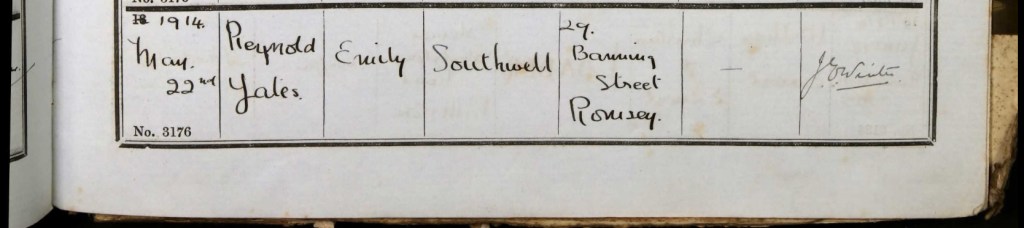

On Friday, the 22nd day of May, 1914, Emily Kate Southwell brought her infant son, Ronald Gates Southwell, to be baptized in a church in Romsey, Hampshire. The name of the church is unfortunately unrecorded, but the ceremony was performed by J. E. Winter, who dutifully entered the details into the baptism register.

At the time of his baptism, Emily and little Ronnie were residing at Number 29, Banning Street, Romsey, a modest address that suggests she was navigating the early months of motherhood in quiet determination. However, a small yet notable discrepancy appears in the baptismal record: Ronnie’s name was mistakenly entered as “Ronald Yates” instead of “Ronald Gates.” Whether this was a simple clerical error or a misunderstanding during the ceremony remains unknown, but it stands as an intriguing footnote in his early life.

Emily’s choice to baptise her son speaks to the importance of faith and tradition in her life. In an era when baptism was not just a religious rite but also a significant social custom, it was a moment of formal recognition for Ronnie, a sign that, despite the absence of a father’s name on his birth record, he was embraced into the community of the church.

This act of devotion may have been a source of comfort for Emily, a young mother making her way in the world with her child. The ceremony, likely attended by close family or friends, marked the beginning of Ronnie’s spiritual life and placed him within the longstanding traditions of the Southwell family.

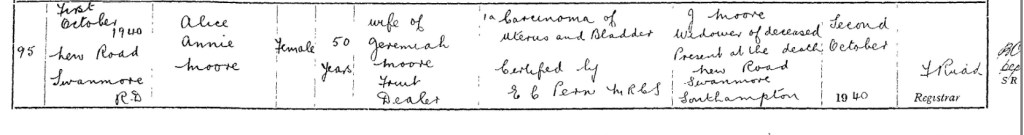

On Sunday, the 6th of February, 1916, in the midst of the First World War, Emily Kate Southwell gave birth to a baby girl at Number 161, Northam Road, Southampton, Hampshire. She named her Doris Violet Southwell, a delicate yet strong name for a child born during uncertain times.

Unlike many births where the mother herself or a close family member registered the event, it was M.A.C.E. Saunders, a resident of 161 Northam Road, who took on the responsibility of registering Doris’s birth on Tuesday, the 14th of March, 1916. The registrar, Alfred Thomas Bunt, officially recorded the birth, listing Emily Kate Southwell as the mother, her occupation noted as a hotel waitress. Yet, just as with her first child, no father's name was provided, leaving questions that remain unanswered in the official records.

What the birth certificate does not reveal is the story of the household where Doris was born. Mrs. Saunders, the woman who registered the birth, was a shopkeeper, likely well-known in the local community. Another Mrs. Saunders also resided at the same address, and she was a midwife, suggesting that Doris was brought into the world under the skilled hands of someone trained in childbirth. Given the era, it is likely that Emily sought the care of this midwife rather than giving birth in a hospital, as home births were still the norm, especially for working-class women.

The circumstances surrounding Doris's birth paint a picture of Emily’s resilience. As a single mother of now two children, working as a hotel waitress, she faced the trials of life with quiet determination. The choice to give birth at 161 Northam Road may have been one of necessity rather than preference, a place where she could receive care and shelter at a time when she needed it most.

Though the official records are sparse in detail, they hint at a network of women supporting each other, Emily, the shopkeeper, the midwife, coming together in a time when community meant survival. It was within this environment that baby Doris took her first breath, beginning her own journey in a world that was rapidly changing around her.

In the early spring of 1916, amidst the turmoil of war and personal hardship, Emily Kate Southwell sat down to write a letter that no mother would ever wish to pen. Desperate and alone, she reached out to a Mrs. Allison, pleading for the possibility of a new home for her infant daughter, Doris Violet. The letter is raw and unpolished, filled with urgency, sorrow, and the quiet devastation of a woman abandoned by her own family.

Emily’s words reveal a woman at the end of her strength. She speaks of a Salvation Army lady who had first given her hope, only to have that hope snatched away when circumstances prevented her from taking the baby. The weight of her isolation is stark “My people have deserted me altogether now.”She had no safety net, no family support, and yet, she still clung to the instinctive desire to secure the best possible future for her daughter.

She promises what little she can, offering to help pay for Mrs. Allison’s fare if she can come to Southampton to take the child. Her request is urgent, pleading “do very your best to take baby” a mother’s final effort to ensure that her child does not suffer the same hardships that she herself has endured.

The closing lines of the letter are haunting in their simplicity. There is no elaboration, no explanation, just a name, an address, and the fragile hope that somewhere, someone will answer.

M.E. Southwell

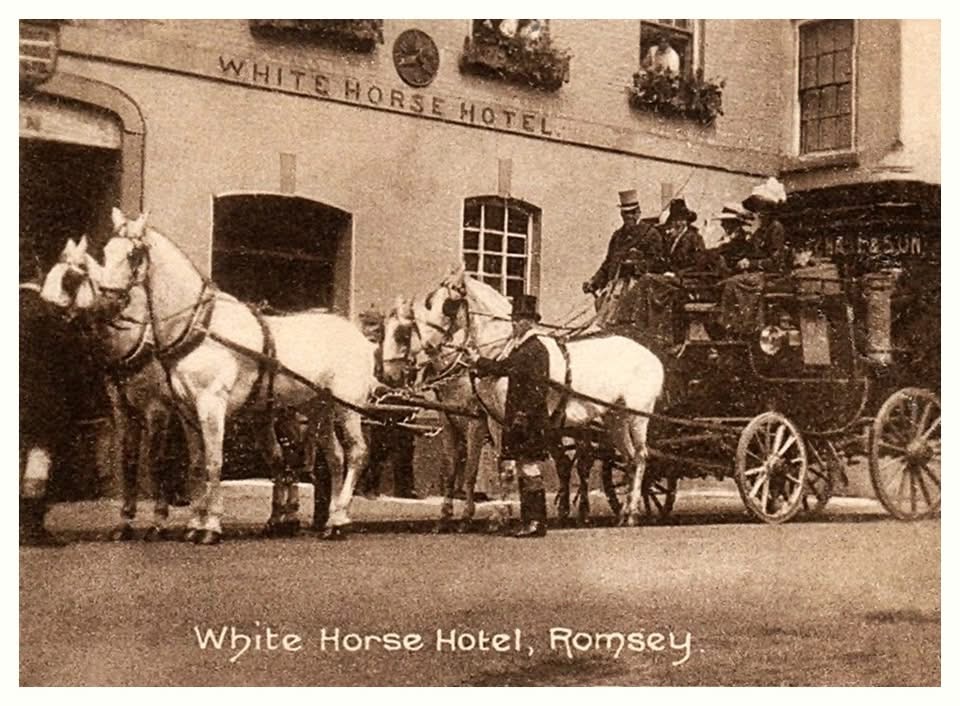

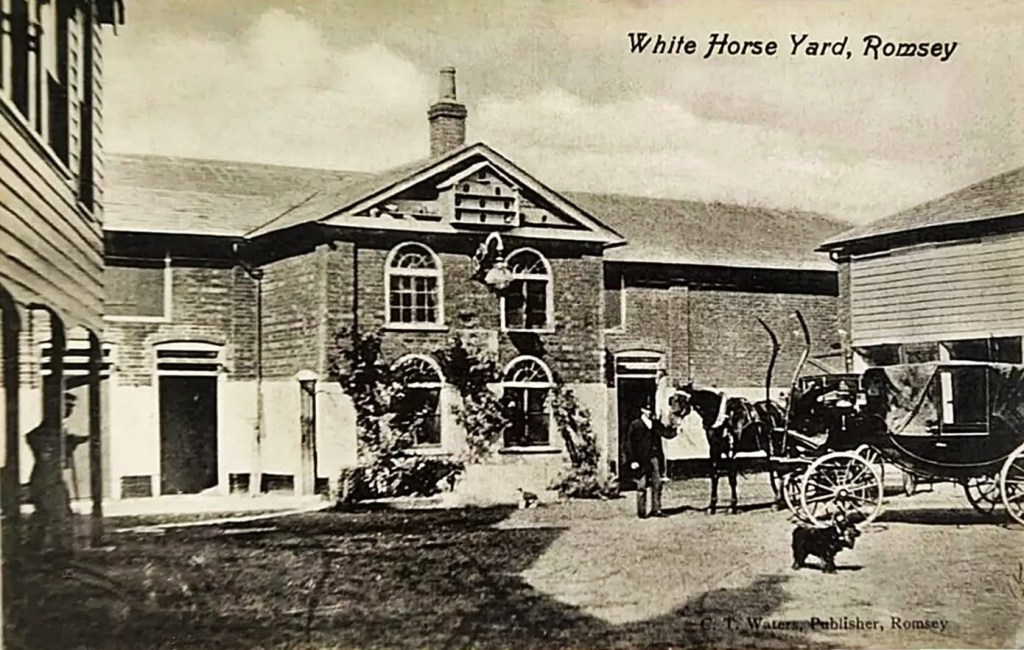

White Horse Hotel

Romsey

The White Horse Hotel was both her place of employment and temporary residence, a stark contrast to the warmth of a family home she could not provide. One can only imagine the emotions that must have filled that space as she waited for a reply.

Emily’s letter is more than just ink on paper. It is a testament to the quiet struggles of countless women in history who, faced with impossible choices, acted with love, even when it meant letting go.

The heartbreaking letter reads as follows,

To Mrs. Allison,

I am writing to ask you it you coud take my baby.

I should be so glad it you could. The salvation Army Lady told me to write to you. She thought she would be able to come down to her home but she told me last night they would'nt let her, if you could take baby could you come as far as Southampton I would help to pay your fair up, let me know as soon as you can because of lettingthe women know, The lady that told me about you is awfully upset because she could take the baby down with her, do very your best to take baby My people have diserted me altogther now. Do let me know as soon as you can p.s.

I remain yours Sincerley E.S.

My Address is

M E. Southwell

White Horse Hotel

Romsey

The White Horse Hotel, located in the Market Place of Romsey, Hampshire, stands as a testament to England's rich history, with origins tracing back to the late medieval period. Constructed between 1450 and 1530, it is a rare surviving example of a purpose-built inn from that era. Its original layout and exposed timber structures reflect the architectural styles prevalent during the Tudor period.

Throughout its existence, The White Horse has played a pivotal role in Romsey's community. Initially, it may have served as a guesthouse for the nearby abbey, providing lodging for pilgrims and travelers. Over the centuries, it evolved into a bustling coaching inn, offering rest and refreshment to those journeying through the region. Its significance is further highlighted by its Grade II listing, recognizing its historical and architectural importance.

By 1916, during the First World War, The White Horse Hotel had established itself as a central hub in Romsey. The war brought about significant social and economic changes, and establishments like The White Horse adapted to meet the needs of both locals and travelers. In that year, Richard Bowen registered a new 20 horsepower Ford Model T Landaulet as a taxi based at the hotel, indicating the inn's commitment to modernizing its services and catering to the evolving transportation needs of its patrons.

Working at The White Horse Hotel in 1916 would have been both demanding and dynamic. Employees were expected to cater to a diverse clientele, including local residents, travelers, and possibly military personnel, given the ongoing war. Staff roles ranged from kitchen duties, where the heat and pace could be intense, to front-of-house positions requiring impeccable service and decorum. The hotel's long-standing reputation meant that maintaining high standards was paramount. Employees likely worked in shifts, with morning duties commencing around 7 a.m. and evening shifts concluding by 10 p.m. The environment would have been bustling, with staff polishing kitchenware, setting tables, and ensuring that guests received prompt and courteous service.

The physical setting of the hotel in 1916 retained much of its historic charm. The Tudor Lounge, adorned with original frescoes and period wallpaper, would have been a focal point for guests seeking a traditional English ambiance. The oak-paneled walls and historic furnishings, including coaching clocks and antique chests, added to the establishment's character. For staff, working amidst such rich history would have been both a privilege and a responsibility, as they preserved the legacy of a centuries-old institution while adapting to the contemporary needs of their guests.

In the early months of 1916, as winter gave way to spring, Emily Kate Southwell penned a second letter to Mrs. Allison. This time, her words carried a different tone, one of relief, resolution, and a finality that must have been both heartbreaking and reassuring all at once.

"Dear Mrs. Allison,

I am very pleased to hear from you, glad you can take baby."

These opening lines reveal the overwhelming gratitude Emily felt upon receiving Mrs. Allison’s reply. The uncertainty that had weighed so heavily on her in the first letter was now met with a glimmer of hope, her daughter would have a home. A future. A chance at stability that Emily herself could not provide.

"I will keep the baby to you come up. I will write and tell the women you are going to have baby. I am so glad."

Despite the simplicity of her words, the emotion behind them is profound. Emily was holding on, waiting for Mrs. Allison to arrive, ensuring everything was arranged. There is no hesitation, no second-guessing, only an acceptance of what must be done.

The postscript, however, carries an undeniable weight,

“P.S. Write again before you come up. I shan't want it back again you needn't worry about that."

These words, written with such certainty, must have been an attempt to reassure Mrs. Allison. Perhaps Emily had sensed an underlying concern, a fear that she might change her mind, that she might return one day to reclaim her daughter. But Emily wanted to put that worry to rest. She had made her decision, painful as it was.

The closing line is brief but sincere,

"I remain Yours sincerely,

E. Southwell."

It is a quiet ending to a letter that represents one of the most significant moments in Emily’s life. In these few lines, she was not just arranging for her daughter’s future, she was making the ultimate sacrifice, one that only a mother could truly understand.

One can only imagine the mix of emotions she must have felt as she sealed the envelope, sending off the final confirmation that Doris Violet would soon be leaving her arms forever.

The letter reads as follows,

Dear Mrs. Allison,

I am very pleased to hear from you, Glad you can take baby. I will keep the baby to you come up. I will write and tell the women you are going to have baby. I am so glad. P.S. write again before you come up. I shan't want it back again you needn't worry about that.

I remain yours sincerely,

E. Southwell.

The third letter from Emily Kate Southwell to Mrs. Allison, reveals the immense emotional and physical strain she was under during the spring of 1916. It speaks of her desperation, exhaustion, and deep concern for her baby’s future. Unlike her earlier letters, which were filled with gratitude and hope, this one carries a tone of urgency and vulnerability. Emily’s words make it clear that she was struggling, not only with the reality of giving up her child but also with her own declining health.

She pleads once again for confirmation that Mrs. Allison will take baby Doris, emphasizing how much it would mean to her. The phrase “I should be so glad if you would” echoes her earlier letters, but here, it is laced with weariness. Her words, “I am not fit for work,” suggest that she was physically and emotionally exhausted, likely due to the demands of single motherhood, financial strain, and the stigma attached to having an illegitimate child during that time.

Perhaps the most poignant part of this letter is when she acknowledges her need for rest. The doctor’s advice to “have a rest” implies that Emily was suffering from more than just exhaustion, she may have been malnourished, overwhelmed, or even suffering from postpartum complications. This letter is a glimpse into the life of a woman who had very few options, yet she was determined to secure the best possible future for her child.

Her final plea for Mrs. Allison to “come up as soon as you can” and her offer to “help to pay your fare” show how desperate she had become. Money was likely scarce, yet she was willing to sacrifice what little she had to ensure that her baby had a secure future. The repeated requests for a response suggest that she had been anxiously awaiting news, likely checking for letters daily in the hopes that Mrs. Allison would finally confirm her plans.

This letter is a heartbreaking testament to a mother’s love, resilience, and sacrifice. It highlights the social challenges faced by women in Emily’s position and the difficult choices they had to make. Through these letters, we gain a deeply personal insight into Emily’s struggle, one that was shared by countless women of her era.

The emotional letter reads as follows,

Dear Mrs. Allison,

I am writing to ask you again if you intend having baby. I should be so glad if you would for I am not fit for work and I wanted to get baby into a good home. I have been expecting a letter from you. Will you let me know as soon as you can then when I get baby settled the doctor says I am to have a rest. I am rundown. I remain yours, sincerely E. Southwell.

Do come up as soon as you can, will help to pay your fair.

Emily Kate’s letter, written on June 9, 1917, from the White Horse Hotel, in Market Place, Romsey, is yet another deeply emotional plea from a mother struggling with impossible circumstances. Unlike her previous letters regarding Doris, this one expresses a quiet resignation. She was offering her son, Ronald, for adoption to the same woman who had taken in her daughter, approximately nine months before, perhaps believing that he, too, would have a better life than she could provide.

The simplicity of her words, "I am quite willing to give baby to you," speaks volumes. There is no hesitation, no pleading, just a calm and sorrowful acceptance of her situation. Emily had likely endured another year of hardship, and in that time, she must have come to terms with the reality that she could not keep Ronald with her. The fact that she was reaching out to Mrs. Allison again suggests that she believed Doris had found a safe and loving home, and she wanted the same for her son.

Her request to “hear soon from you sometimes” reveals a quiet longing to remain connected to her child in some way, even from a distance. It suggests that she did not want to fully sever the bond with her baby, even if she knew she could not raise him herself. This small request shows a mother’s enduring love, even in the face of heartbreak.

For reasons unknown, this adoption did not take place, and Ronnie remained with Emily. Whether Mrs. Allison was unable or unwilling to take in another child, or whether some external factor prevented it, we may never know. But this letter is yet another heartbreaking testament to Emily’s struggle, a woman caught between societal expectations, financial hardship, and the overwhelming love she had for her children.

Emily Kate’s heart-rendering letter reads as follows,

White Horse Hotel

June 9th 1917

Dear Mrs. Allison,

Baby was born the 9th March and l am quite willing to give baby to you because I am quite satisfied it is cared for, but I should like to hear soon from you sometimes, hoping you are all well.

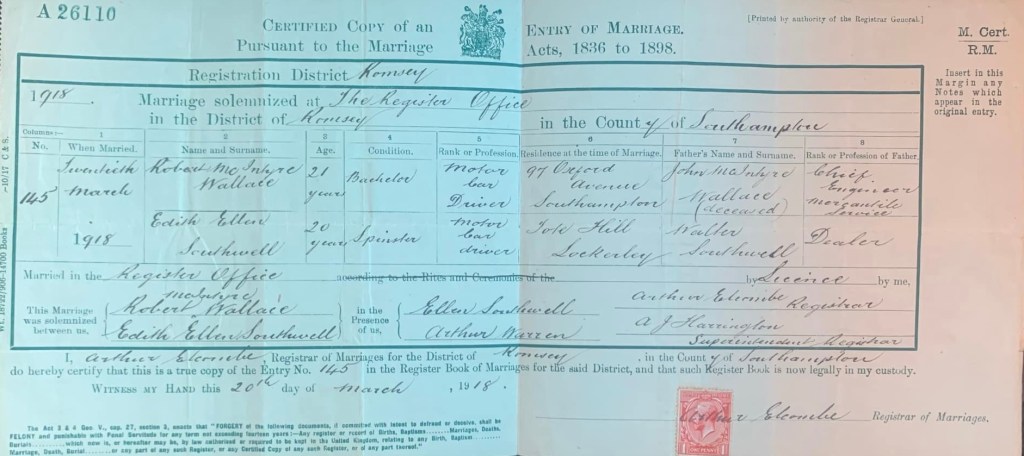

Emily’s sister, Edith Ellen Southwell’s marriage to Robert McIntyre Wallace on the 20th day of March, 1918, at the Register Office in Romsey, Hampshire, marks an important milestone in her life. At 20 years old, she was stepping into a new chapter, not just as a wife but as an equal partner to Robert, both of them working as motor car drivers, an occupation that would have been quite modern and somewhat unusual for a young woman at the time. Their shared profession suggests a sense of adventure and independence, qualities that may have drawn them together.

Robert’s background was quite different from Edith’s. His father, the late John McIntyre Wallace, had been a chief engineer in the mercantile service, a position of significant responsibility within the maritime industry. This detail hints at a family with strong connections to the sea, which was fitting given Southampton’s status as a major port city. Meanwhile, Edith’s father, Walter Southwell, was recorded as a dealer, reflecting his entrepreneurial spirit in trading goods and produce.

The wedding itself was a civil ceremony, rather than a traditional church service, which could indicate a variety of reasons, perhaps a preference for simplicity, wartime restrictions, or even practical considerations given their working-class backgrounds. The witnesses, Edith’s mother, Ellen Southwell, and Arthur Warren, suggest that there was still strong family support for Edith’s union, at least from her mother’s side.

As for Emily Kate’s presence at the wedding, it remains uncertain. Given the family’s reaction to her two illegitimate children, it is possible she was not included in the celebrations. However, the bond between sisters often transcends societal judgment, and it is comforting to imagine that Edith, Alice, or Winifred may have kept in touch with Emily, even if in secrecy. Families are complex, and love does not always adhere to the expectations of the time. Whether openly or behind closed doors, it is likely that Emily was never far from their thoughts.

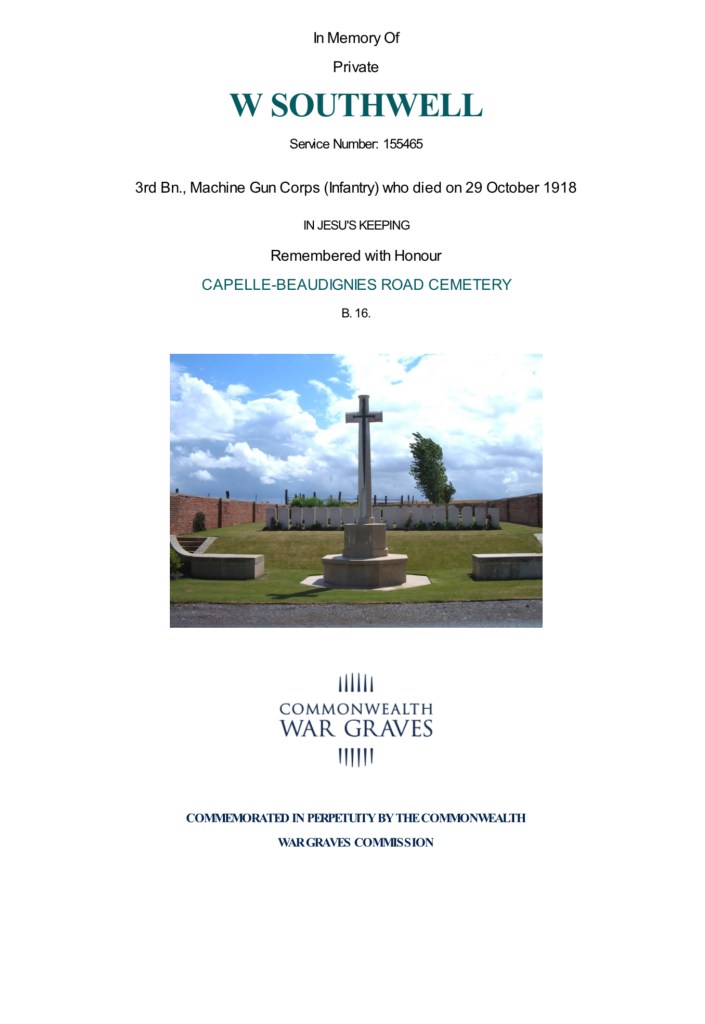

The loss of Emily’s brother Frederick Walter Southwell, known as Private Walter F. Southwell of the Machine Gun Corps, would have been a deeply painful moment for the Southwell family, and the heartache it caused must have reverberated through the lives of those who loved him, especially his siblings. Frederick’s death on Tuesday the 29th day of October, 1918, just days before the armistice, marked a tragic end to a life that was still young, he was only 19 years old when he was killed in battle during the final months of the First World War.

For Emily Kate, who had already endured so much personal hardship, it’s hard to imagine the toll this news would have taken on her. The question of whether she grieved alongside her family or faced her sorrow alone is one that lingers in the heart. It’s possible that, given the family’s disapproval of her and her children, Emily may have been excluded from the mourning rituals that followed Frederick's death. The painful reality of family estrangement, especially due to societal pressures and moral judgments of the time, could have left her feeling even more isolated in her grief.

If she was not included in the collective mourning of her family, she would have faced the loss of her brother privately. That sense of loneliness, coupled with the weight of her family’s possible rejection, would have undoubtedly been a burden to bear. Still, as a mother who had already endured personal sacrifice, Emily may have found some way to grieve for her brother, whether in private reflection or through her own quiet acts of remembrance.

It’s heartbreaking to think that Frederick may have passed away believing the worst of his sister, considering the distance that had grown between Emily and her family. The complexities of family relationships, especially those strained by societal expectations, can often lead to misunderstandings and regrets that last a lifetime. But in these moments, it’s important to also consider that life is never simply black or white, and the love between siblings, even when clouded by societal judgment, may have lingered beneath the surface.

We can only hope that, somewhere in the quiet recesses of her heart, Emily held the love she had for Frederick, even if circumstances kept her from sharing that grief with her family. The deep emotional cost of war is felt not only by those who served but also by those who are left behind, each carrying their own sorrow, sometimes in silence.

The final resting place of Emily Kate’s brother, Frederick Walter Southwell, known as Private Walter F. Southwell, at the Capelle-Beaudignies Road Cemetery in France, offers a solemn and poignant reminder of the sacrifices made during the First World War. Frederick’s death, at just 19 years old, is a devastating loss not only for his immediate family but also for the larger community that would have known and cared for him. His burial in Plot B. 16 in a war cemetery in France, surrounded by the graves of so many others who gave their lives for their country, places his memory among the countless soldiers who, like him, faced the horrors of battle with courage.

Capelle-Beaudignies Road Cemetery is one of the many military cemeteries that serve as a place of reflection for those who seek to honor the fallen. It is a quiet, respectful site, where each gravestone is etched with the name of a soldier who perished during the war. Frederick’s resting place, far from home and family, must have been a powerful symbol of both sacrifice and sorrow for Emily and the Southwell family, particularly knowing that his young life was claimed so close to the end of the war.

Though Emily was likely not able to mourn alongside her family, as mentioned before, the deep loss of her brother would have shaped her life in ways we can only imagine. Frederick’s final resting place, in a cemetery that stands as a tribute to all soldiers who fought and died, is a quiet yet permanent reminder that his sacrifice, along with the sacrifices of countless others, was not forgotten.

In a way, the location of his grave in a foreign country further emphasises the tragedy of the Great War, a war that scattered families and left so many without closure. Yet, the presence of these cemeteries offers a sense of peace, as it ensures that the fallen are honored, remembered, and given the dignity they deserve, even if Emily, and others like her, were not able to grieve in the way they might have wished. Frederick’s grave is a testament to the ultimate cost of the war, and a place where his sacrifice can be quietly and respectfully acknowledged for generations to come.

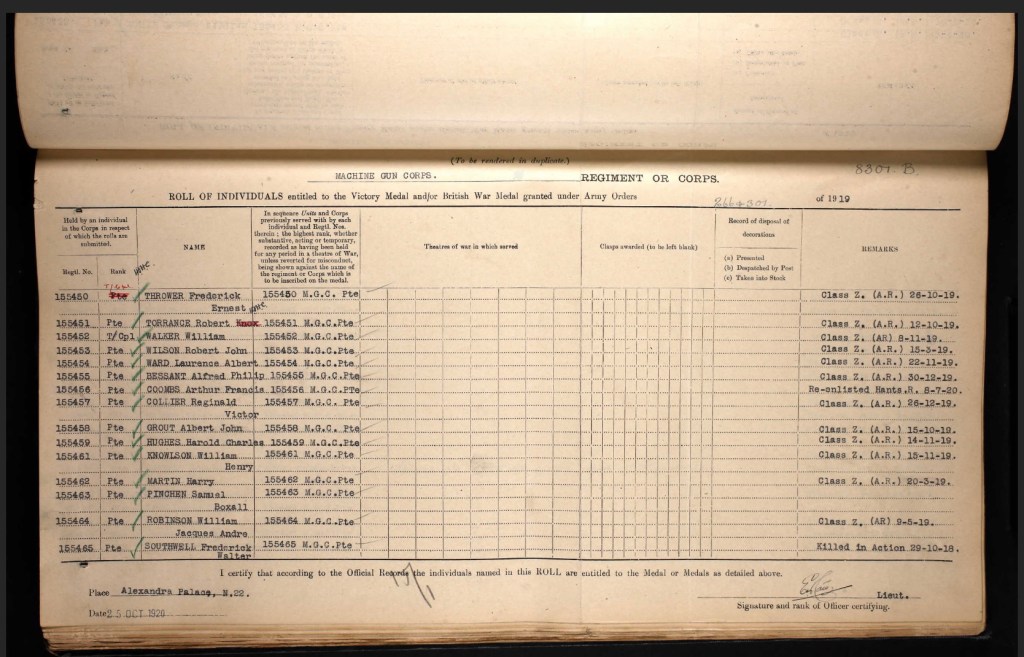

Frederick Walter Southwell, Emily's brother, was posthumously awarded the Victory Medal on Monday, the 25th of October, 1920, for his service and sacrifice during the First World War. The Victory Medal was awarded to all personnel who had served in the armed forces during the war, and it symbolized both the toll of the conflict and the recognition of those who had fought. It was a poignant acknowledgment of Frederick’s bravery, but it also must have been a bittersweet moment for the family. Frederick’s death had left a hole that could never truly be filled, and the medal, while a testament to his courage, would have only highlighted the profound loss they had suffered.

It is difficult to say for certain whether the Southwell family traveled to any formal ceremony to receive the medal or if they were even involved in any official commemoration. In many cases, medals like the Victory Medal were either sent by post or presented in a smaller, more intimate setting, especially in the aftermath of the war. Whether or not Emily or her family attended a public ceremony, the emotional weight of Frederick's award would have been deeply felt, though likely with a mixture of pride and sorrow. His medal would have been a symbol of the tremendous price he paid and the grief that lingered within the family, compounded by the unresolved feelings surrounding Emily’s own position within the family at the time.

It is also unclear if Emily was included in the ceremonies, or if she was distanced from such official recognitions due to her estrangement from the family. Given the tension within the Southwell family, especially due to Emily’s personal circumstances and her distance from her siblings, it’s possible that she may not have been involved, either in person or in spirit, with any formal proceedings surrounding the award of her brother’s medal.

But even if no ceremony took place with the entire family together, or if Emily wasn’t physically present, Frederick’s memory would have lived on in their hearts. The Victory Medal, whether seen in public or held privately, would remain an enduring symbol of the sacrifice he made. It was a solemn reminder that even as life went on for the family, some wounds, like the loss of Frederick, would never truly heal.

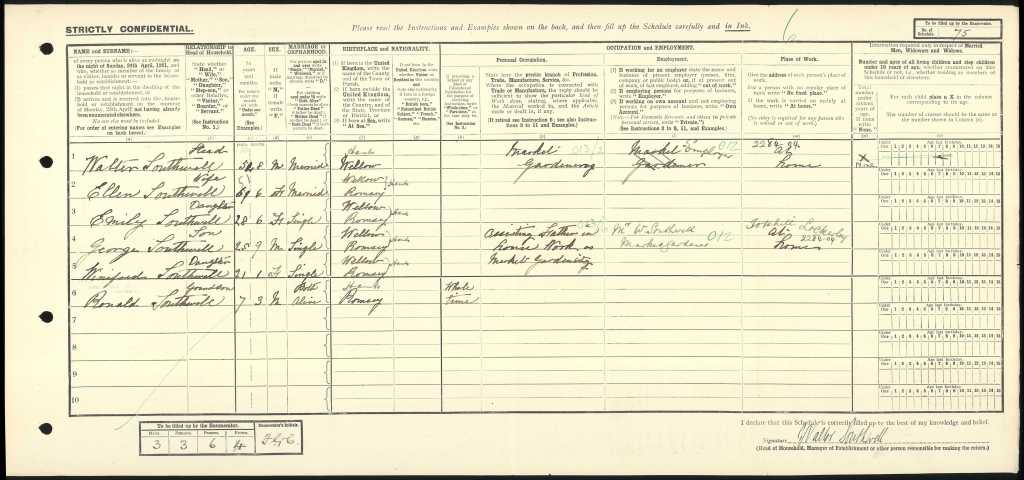

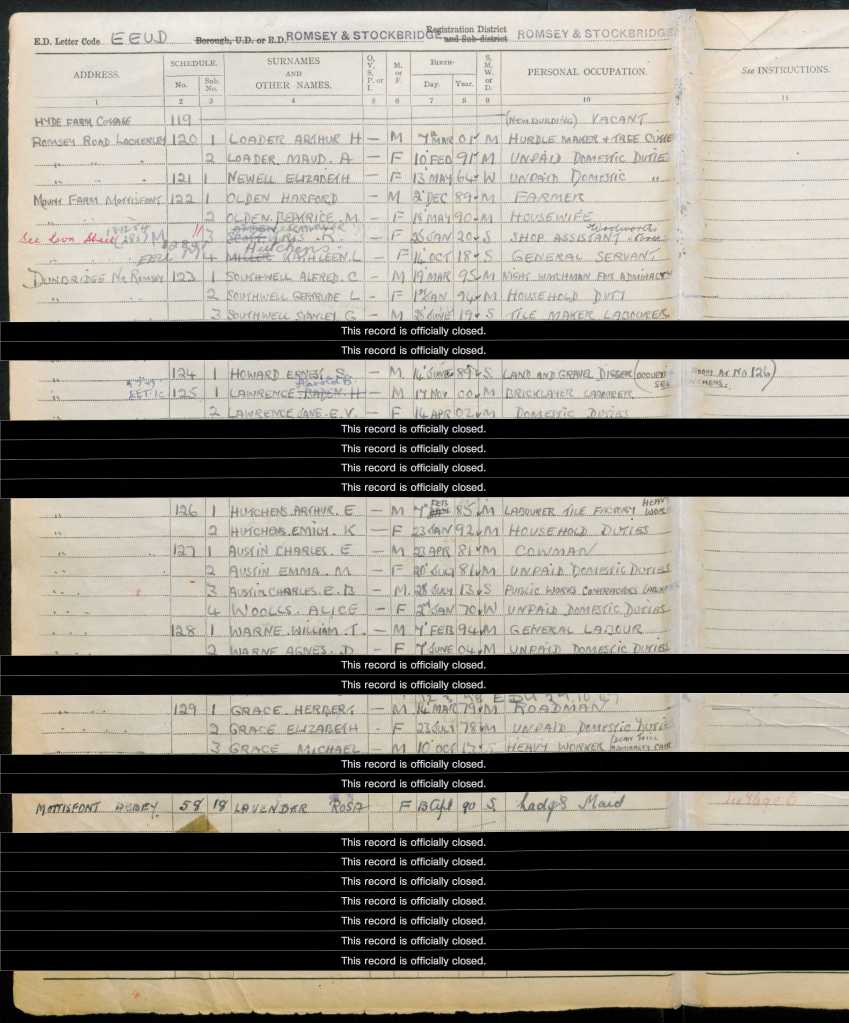

On Sunday, the 19th day of June, 1921, Emily Southwell, now a 28-year-old single woman, resided in the village of Lockerley, Hampshire, England, at the address of Totehill, Lockerley, Romsey. At this time, she was living with her parents, Walter and Ellen Southwell, along with her younger siblings and her son, Ronald. Walter, now 54, and Ellen, aged 51, were part of this family household, alongside Emily’s 21-year-old sister, Winifred, and her 25-year-old brother, George. Ronald, Emily’s 7-year-old son, also lived with the family, adding an extra layer to the household dynamics.

This moment in 1921 marks a significant point of closure in the long-standing separation between Emily and her family. For many years, Emily had faced a complex relationship with her parents and siblings, particularly due to the circumstances surrounding her two children and her own struggles. However, the 1921 census reveals that Emily had rejoined her family, living with them again after years of estrangement. The tension that once existed seemed to have softened, and the household consisted of six members, Emily now the eldest daughter, at home with her parents and siblings, and raising her son within that supportive (and likely complicated) environment.

Walter, who had been a farmer in earlier years, was now listed as a general dealer, which reflected the shifting circumstances of the family’s livelihood following the upheaval of the First World War. The family, now working together in a new dynamic, would have found their lives shaped by the post-war realities of economic hardship and societal change, which also influenced their daily lives and relationships.

For Emily, returning to live with her parents and siblings in 1921 could have represented a fresh start of sorts, or at least a sense of closure regarding the separation she had once felt so acutely. Her son, Ronald, was an integral part of the household, growing up within the same space as his extended family. This shift also allowed Emily to redefine her place within the family unit, despite the challenges and complexities she had experienced. The 1921 census indicates that, after many years, the Southwell family had come to a point of reconciliation, where Emily was once again a part of the family, and the long period of estrangement seemed to be finally closing.

The dynamics of the household were undoubtedly shaped by both the shared history and the support of living together again. While it is impossible to know all the emotions at play, the fact that Emily was living with her family again indicates a shift toward healing or at least a new chapter in her life and the Southwell family’s story.

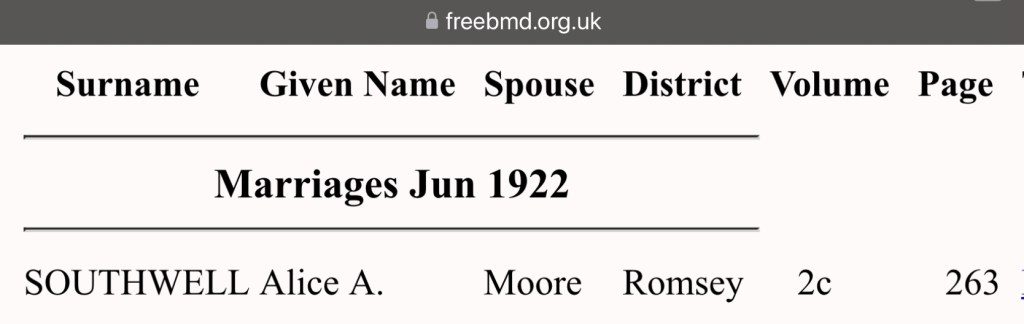

On Tuesday, the 2nd day of May, 1922, Emily Kate’s eldest sister, Alice Annie Southwell, stood before family and friends in either a church or the registry office in the district of Romsey, Hampshire, to marry Jeremiah Moore. Their union marked a new chapter for Alice Annie, a significant moment in her life after many years spent in the company of her family. This marriage was a joyful occasion, one that likely brought about a mix of emotions for Alice, her loved ones, and perhaps even her sister, Emily, who had been through her own tumultuous experiences.

For those interested in official documentation, Alice Annie’s marriage certificate can be obtained using the following GRO Reference information:

GRO Reference - Marriages, Jun 1922, Southwell, Alice A, Moore, Jeremiah, Romsey, Volume 2c, Page 263.

This record stands as a testament to Alice Annie’s new beginning, but also a quiet marker in the long-running saga of the Southwell family’s lives. As Alice embarked on her journey with Jeremiah, the wider family would have continued to navigate their own challenges, triumphs, and complexities, one of which, in Emily’s case, was still finding her way back into the fold after years of estrangement. It is possible that the marriage of Alice Annie was a fresh start for her as well, offering her the companionship and future she had longed for.

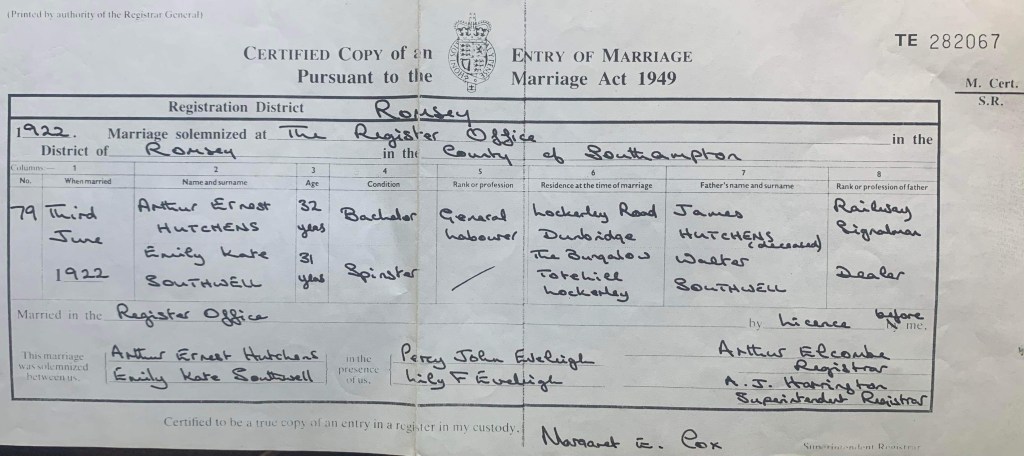

On Saturday, the 3rd day of June, 1922, 31-year-old Emily Kate Southwell, a spinster residing at The Bungalows, Totehill, Lockerley, Hampshire, England, married 32-year-old bachelor, Arthur Ernest Hutchens, a general labourer from Lockerley Road, Dunbridge, Hampshire, England. The ceremony took place at The Register Office in Romsey, Hampshire, where Emily and Arthur were united in marriage by Arthur Elcombe, the registrar, and A.J. Harrington, the Superintendent Registrar.

The marriage registry recorded that Emily was the daughter of Walter Southwell, a dealer, while Arthur was the son of the late James Hutchens, a railway signalman. The couple was joined by witnesses Percy John Eveleigh, Lily F. Eveleigh, and Margaret E. Cox, who all signed the register, marking the beginning of this new chapter in Emily and Arthur’s lives.

This union was a significant moment for Emily, offering a sense of stability and the possibility of a fresh start after years of personal struggles and separation from her family. It also brought her into the life of Arthur, a man who, though not directly connected to the Southwell family by blood, would become a crucial part of her future. Their marriage set the foundation for a new family dynamic, one which would carry them through the challenges and joys of the coming years.

On Monday, the 1st day of August, 1932, Emily’s sister, Winifred May Southwell, married Percy Alexander East in the Romsey district of Hampshire, England. Their marriage marked an important step in Winifred’s life, as she embarked on a new journey with Percy, who would become her lifelong partner.

For those wishing to obtain official documentation, their marriage certificate can be purchased using the following GRO Reference information:

GRO Reference - Marriages, September 1932, Southwell, Winifred M, East, Percy A, Romsey, Volume 2c, Page 289.

This union represented another milestone in the Southwell family’s story, adding another chapter to the narrative of Emily’s siblings and their own paths in life. It is likely that Winifred’s wedding was a day filled with joy, marking a fresh beginning for her as she built a future with Percy. Like her sister Alice, Winifred was finding her place in the world through marriage, and the family would have had their own reflections on the changing dynamics of their household.

on their wedding day,

On Friday, the 29th day of September, 1939, Emily Kate and Arthur Ernest Hutchens were living together at Dunbridge, Romsey, Hampshire, England. At this time, Emily’s occupation was listed as "Domestic Duties," a role that reflected her responsibilities within the household. Arthur, her husband, worked as a labourer in a tile factory, specifically in the heavy works section, which likely involved physically demanding tasks.

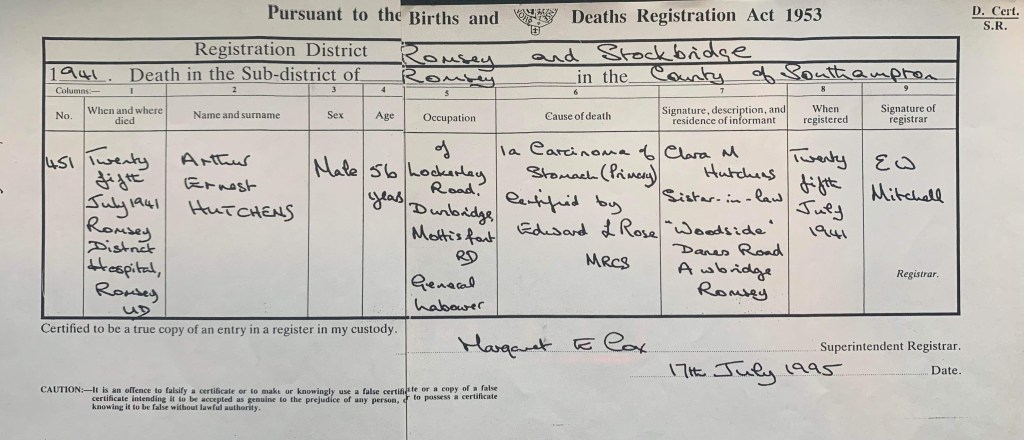

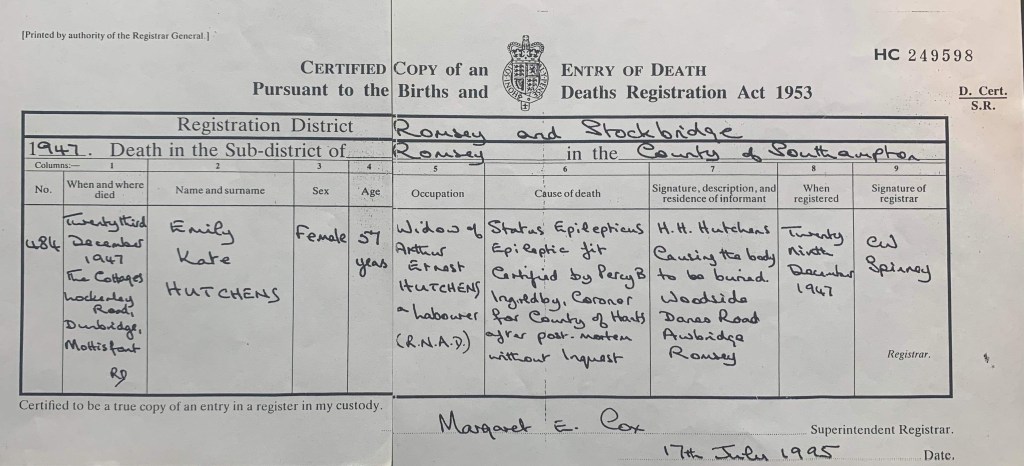

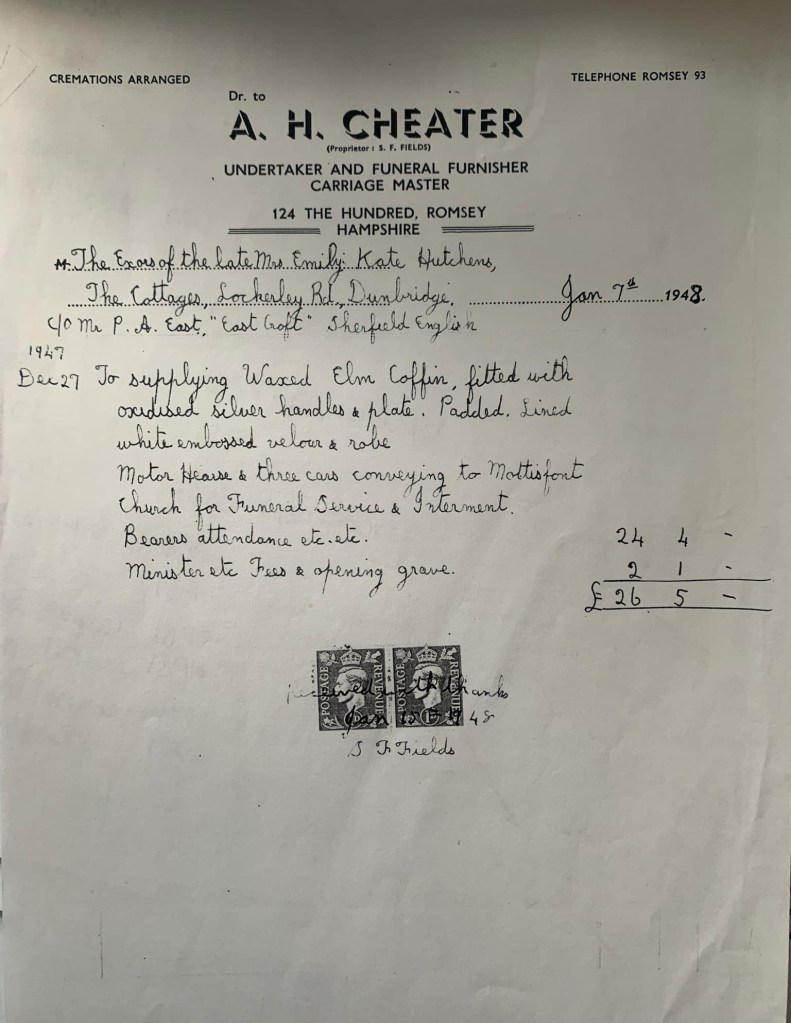

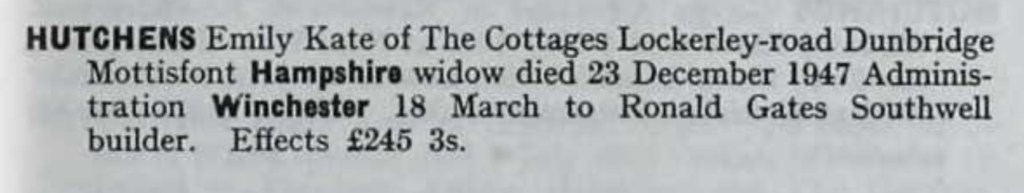

The 1939 Register also recorded their respective dates of birth, with Emily born on the 23rd of January, 1892, and Arthur on the 7th of February, 1885. This document offers a glimpse into their lives during a period of global unrest, just before the outbreak of World War II, and provides a sense of the daily routines they likely settled into after their marriage in 1922. It reflects their quiet life in Dunbridge, Hampshire, where they resided in a modest home, perhaps with an undercurrent of concern about the years ahead, as the world faced immense challenges.