In the quiet corners of history, amidst the yellowed pages of parish records and the labyrinthine trails of ancestral research, lies the remarkable tale of my paternal 3rd Great Grandfather, Stephen Withers. Born in 1831 and departing this world in 1916, his life spans an era of profound change and endurance.

Navigating through the annals of time, I've come to cherish both the challenges and the triumphs of unearthing Stephen's story. The quest isn't merely about names and dates but about piecing together a narrative from fragments scattered across dusty archives and digital subscriptions that seem to grow costlier with each revelation sought.

Yet, amidst the frustrations and rising expenses, there exists a profound joy, a whisper of elation when a single piece of information emerges from the haze of history. It's in those moments that the paper trail of Stephen's life becomes more than records, it transforms into a testament of resilience, a testament of a life lived amidst the tumultuous currents of his time.

Join me as we delve into "The Life of Stephen Withers: 1831–1916, The Early Years," a journey not only through his personal milestones but through the intricacies of genealogical pursuit, where each discovery is a beacon illuminating the shadows of the past.

The Life of

Stephen Withers

1831–1916

The Early Years

Welcome back to the year 1831, Romsey, Hampshire, England. The town and its surroundings were steeped in rural tradition, while across the country great waves of change were beginning to rise. The monarch on the throne was King William IV, who had ascended the previous year after the death of his brother, George IV. William IV was considered a more approachable and down-to-earth king than his predecessor, and his reign, though relatively short, was marked by significant political and social reforms. The Prime Minister at the beginning of 1831 was Charles Grey, the 2nd Earl Grey, a Whig politician deeply committed to the cause of parliamentary reform, which would culminate in the Great Reform Act of 1832. Parliament at this time was dominated by the wealthy landowning classes, and there was mounting pressure from the growing middle and working classes for a fairer and more representative system.

Romsey itself would have been a fairly small market town with its roots in agriculture and its magnificent abbey at its heart, surrounded by farmland, rivers, and modest industries such as milling and brewing. Society was sharply divided. The rich, often landowners and merchants, lived in fine houses with servants to manage their daily lives. They enjoyed a relatively comfortable existence, with elaborate fashions reflecting their status. Men wore tailcoats, high-collared shirts, and cravats, while women donned high-waisted gowns made of muslin or silk, with bonnets and gloves considered essential for respectability.

The working class, including agricultural laborers, mill workers, and domestic servants, had a much harder existence. They earned meagre wages, often living in small cottages or cramped rooms, with little security if they fell ill or lost work. Their clothing was simple, practical, and durable, usually made of wool or coarse linen. The poor were worse off still, often forced to rely on parish relief or the workhouse. Hunger, disease, and physical exhaustion were daily realities for many. Despite these hardships, there were moments of community and celebration, particularly during market days, fairs, and religious festivals.

Transportation in 1831 was dominated by horse power, whether on horseback, by carriage, or by wagon. In towns like Romsey, the roads were often muddy and difficult, though turnpike trusts had improved some major routes by charging tolls for maintenance. Canals were still an important means of transporting goods, though the railway revolution was just beginning to stir with the opening of early railways elsewhere in the country.

Energy was sourced mainly from wood, coal, and human or animal labor. Most homes and workshops relied on fireplaces or stoves for heating and cooking, and lighting was provided by candles, oil lamps, or early forms of gas lighting in the wealthier areas. There was a heavy, smoky atmosphere in towns, particularly larger ones, where coal smoke darkened the skies and grime settled on buildings and clothes.

Sanitation was primitive by modern standards. There were few proper sewers, and waste was often disposed of in open drains or cesspits. Clean drinking water could not be guaranteed, and diseases like cholera, typhoid, and smallpox were constant threats. In rural areas like Romsey, the risk was somewhat lower than in the filthy, crowded cities, but outbreaks still occurred and could decimate local populations.

Food for the well-off was varied and plentiful, featuring meat, fish, cheeses, fruits, and vegetables, though the preservation of food was a challenge without refrigeration. The working class diet was much simpler, relying heavily on bread, porridge, cheese, and seasonal vegetables, with meat being a rare luxury. Beer was consumed in large quantities, as water quality was unreliable.

Entertainment varied according to class. The wealthy might attend dances, concerts, or theatrical performances, while the working classes made their own amusements at pubs, fairs, and religious gatherings. Singing, storytelling, and sports such as boxing and cricket were popular. Gossip and news spread through word of mouth, newspapers (for those who could afford them or could read), and lively discussion in marketplaces and taverns.

The environment in rural Hampshire was still largely green and agricultural, but there were signs of change. Enclosure acts had altered the landscape by fencing off land that was once common, which had social as well as environmental consequences. Mechanization in agriculture and industry was slowly taking hold, reducing the need for manual labor and pushing many towards urban centers in search of work.

1831 was a year of tension and expectation. The working classes were becoming increasingly politicized, inspired by events such as the Swing Riots of the previous year, when agricultural laborers protested against low wages and the introduction of labor-saving machines. Reform was in the air, and people of all classes sensed that the old ways were under threat. Meanwhile, ordinary life continued in Romsey, with its rhythms of market days, harvests, births, marriages, and deaths, all played out against the grander backdrop of a nation on the brink of profound transformation.

Stephen Withers came into the world on a soft June day in 1831, cradled by the ancient town of Romsey, Hampshire. His parents, John and Mary, already had their hands full with three lively children, Emma, born around 1817, George Henry in 1822, and Clement in 1829. Now Stephen, their fourth child, would add his voice to the music of their growing family.

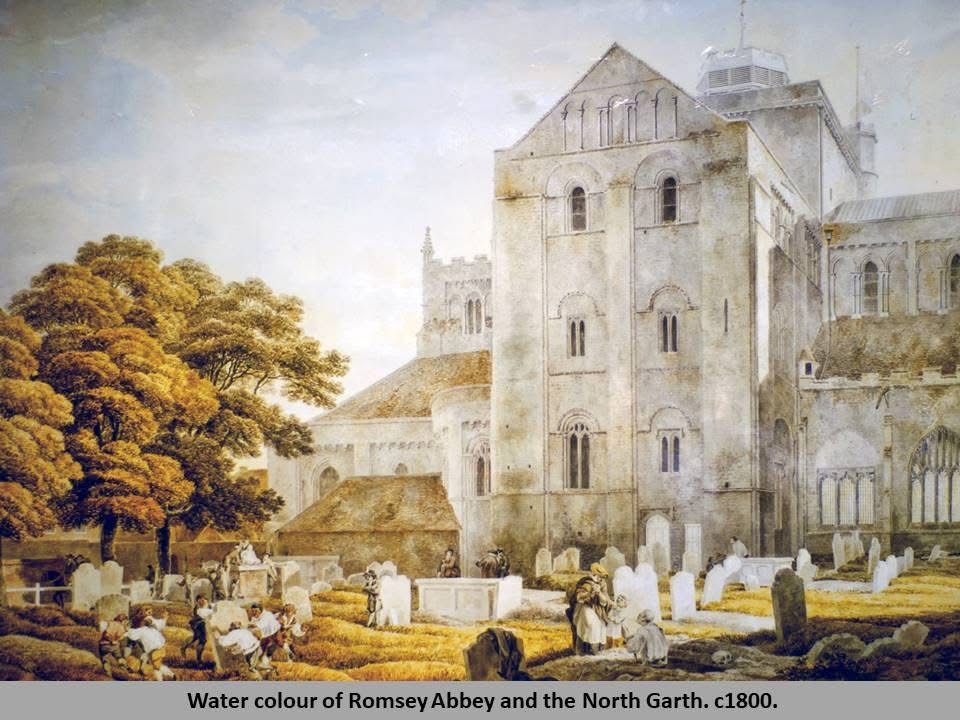

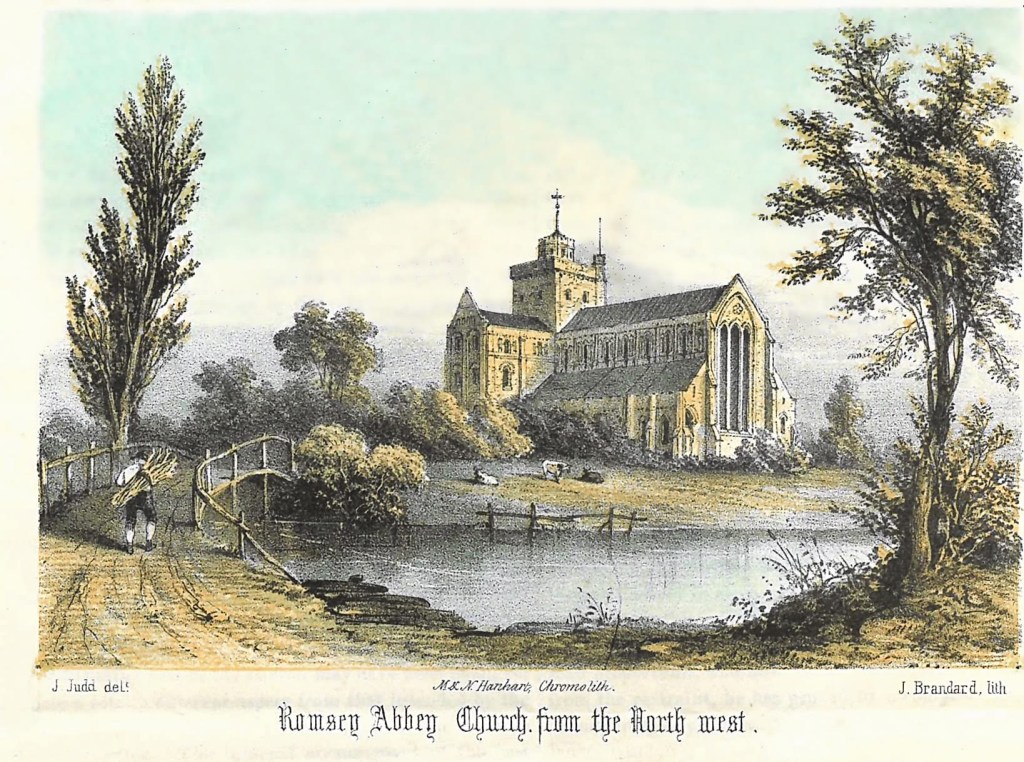

Romsey, even then, was a town steeped in history, its life wrapped around the wide, slow ribbon of the River Test. The river ran clear and constant, feeding the fields and the hearts of those who lived along its banks. Above the clustered rooftops rose the great Romsey Abbey, stone upon stone, a quiet guardian over centuries of births, marriages, and passings.

It is easy to picture Stephen’s early days, small footsteps on worn cobbled streets, the scent of hops from the brewers’ yards drifting in the morning air, the sound of market traders shouting their wares. The town was no stranger to hard work. For generations, Romsey had built its fortunes on wool, then later on brewing, tanning, and milling. Its people lived by the rhythm of the seasons, by the turning of the river’s current, by the slow chiming of the Abbey bells.

When I first set out to find Stephen, the trail was faint, like a thread worn thin by the pull of years. A scrap of baptismal record here, a whisper of a family name there. It is a tender thing, to piece together a life from the fragments left behind. Sometimes it is a single line in a parish register that stirs the soul, a fragile echo of a day when a tiny boy was carried into the Abbey to be blessed into a world as full of struggle as it was of hope.

The Romsey that Stephen knew was beginning to change. In his lifetime, the railways would come, stitching the town more tightly into the fabric of the wider world. But in those first early years, life in Romsey was still ruled by the slow, deliberate pace of nature and tradition. The market square bustled beneath its timber-framed buildings, and the River Test ran through it all, unchanged, as it had for centuries.

And there, in that small but steady world, Stephen grew. A boy in a town of ancient stones and flowing waters, in a family rooted in the hard earth of Hampshire. Every precious detail I uncover about him is like finding a spark, a living thread connecting past to present. His story is a quiet one, but it matters deeply, and it begins here, by the river’s edge, under the wide Hampshire sky.

On a Tuesday, the 14th day of June, 1831, within the ancient stone walls of Romsey Abbey, John and Mary Withers brought their infant son to be baptised. The boy, whom they named Stephen, was placed into the hands of Curate John Ford, who dutifully recorded the moment in the parish register: "Stephen Withers, son of John and Mary of Romsey, baptised on the 14th day of June." No occupation was listed for John that day, only the simple, profound act of naming and blessing a new life.

Stephen’s name carried with it the weight of centuries. From the Greek Stephanos, meaning "crown" or "garland," it was a name steeped in ancient honor and Christian reverence. It spoke of victories hard-won, of quiet dignity, of faith carried through trials. Saint Stephen, the first Christian martyr, had borne it with courage, and from the earliest days of the church, the name spread like a living thread through the tapestry of Europe. In England, Stephen came with the Normans and rooted itself firmly in the soil, passed from king to commoner alike, its syllables ringing out in times of war and peace, in churchyards and marketplaces.

To name a child Stephen was, in some quiet way, to wish for him a life of steadfastness, of meaning, perhaps even of greatness. Whether John and Mary knew all this history as they gazed down at their newborn, or simply chose the name because it felt strong and right, we cannot say. But still, it clings to him now, nearly two centuries later, a part of his story as surely as the stone walls of Romsey Abbey.

The Withers name, too, whispers of old places and older ways. Its origins lie in the land itself: perhaps from the Old English wīðer, meaning "opposite," marking those who lived across the river; or from the Norse vidr, meaning "wood," a sign of life spent near the thick wilds of forest and thicket. For centuries, Withers families tilled the earth, worked the mills, and prayed under the soaring roofs of parish churches scattered across southern England. Men named Withers appear in medieval records, in tax rolls and manorial documents, their lives recorded in ink as thin as breath.

There was never one single great Withers house. Instead, the name belonged to the people who built England not with grand titles but with steadfast labor, with plough and pen, with prayer and perseverance. A poet, George Wither, once stirred the hearts of a divided nation with his verses, but mostly the name lived quietly, carried by farmers, brewers, millers, and tanners who worked the fields and towns of Hampshire, Surrey, and Wiltshire. In heraldic rolls, some branches of the family claimed coats of arms adorned with lions' heads and falcons, symbols of courage and swiftness, but many more bore no arms at all, save for the dignity of honest work and enduring legacy.

Stephen, son of John and Mary, entered the world bearing all of this, the echoes of abbeys and ancient battles, of riverbanks and woodland paths. He was cradled in a town whose heart beat with the slow turning of the River Test, in the shadow of a great abbey whose stones had witnessed a thousand other lives before his.

In tracing his beginnings, finding the delicate ink of his baptism recorded so long ago, it feels as though for a moment, the veil of time lifts, and there he is. Not just a name, but a boy, a son, a life newly begun on a bright June morning in Romsey.

Romsey Abbey, located in Romsey, Hampshire, England, is a historically rich religious site with origins dating back to the 10th century. The abbey was founded in 907 AD by King Edward the Elder as a Benedictine nunnery. Its early history is intertwined with the royal family, including significant donations and royal patronage.

During the 19th century, Romsey Abbey saw a series of notable clergy members. One prominent figure was the Reverend John Keble, who served as a curate there in the early 1800s before gaining fame as a leader of the Oxford Movement, which aimed to reform the Church of England.

The abbey's clergy during this period also included several vicars and curates who contributed to its religious life and community service. Records from the era detail their roles in pastoral care, sermons, and community outreach efforts.

Regarding the nuns, Romsey Abbey was historically a Benedictine nunnery until the Dissolution of the Monasteries under King Henry VIII in the 16th century. The abbey's association with nuns is central to its early history but less pronounced in the 19th century due to the dissolution.

Rumors of hauntings at Romsey Abbey have persisted over the years, with reports of ghostly apparitions and eerie sounds echoing through its ancient halls. These stories often center around the abbey's long history and the various individuals who lived and died within its walls.

One peculiar feature of Romsey Abbey is the display of human hair within its premises. This collection of hair, often intertwined with historical artifacts, is a unique and somewhat macabre aspect of the abbey's heritage, reflecting practices of remembrance and commemoration from past centuries.

Overall, Romsey Abbey stands as a testament to centuries of religious devotion, community service, and historical intrigue. Its legacy continues to attract visitors interested in exploring its architectural beauty, rich history, and enduring mysteries.

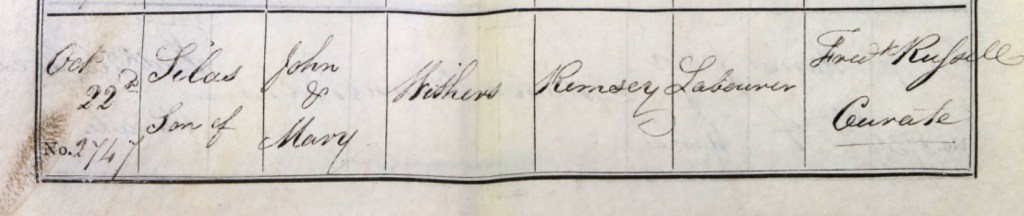

Not long after Stephen’s christening, the bells of Romsey Abbey once again rang out in welcome. Around the year 1832, John and Mary Withers were blessed with another son, their fifth child, whom they named Silas. Born before the autumn leaves had finished falling, Silas Withers came into the world in Romsey, the town his family had long called home.

On Monday, the 22nd day of October 1832, John and Mary carried their infant son through the Abbey’s heavy doors, just as they had carried Stephen before him. This time, it was Curate Frederick Russell who presided over the baptism. With solemn care, he wrote Silas’s name into the parish register: "Silas Withers, son of John Withers, a labourer, and Mary Withers, of Romsey, baptised on the 22nd of October."

For the first time, a fragment more of their life peeks through, the register quietly noting John’s occupation: labourer. A simple word, and yet it speaks volumes. A man of the earth, a worker bound to the rhythm of the seasons, to the demands of field and harvest, to the ancient struggle of earning bread by the strength of one’s own two hands.

Frederick Russell himself was new to Romsey then, just beginning his brief ministry at the Abbey Church. His time among the people of Romsey would be short, by 1834, he would leave to serve in Halifax, where his voice would thunder from the pulpit on matters of faith and reform. But for now, in that golden autumn, he was there to usher Silas into the Christian fold, adding his name to the centuries-old register that held the memory of so many who had gone before.

Silas’s baptism, like Stephen’s before it, binds the family closer to the town’s living history, to the Abbey’s ancient stones, to the River Test flowing ceaselessly beyond, to a community shaped by faith, work, and the unbroken march of generations.

In tracing these small, precious records, mere lines of ink in an aging book, it feels as though one can almost hear the murmur of prayer, the quiet footsteps on the worn stone floors, the hopeful murmur of a mother and father as they bring their child to the font. Silas Withers, a name newly spoken into life, carried forward on the tide of time, a younger brother to Stephen and a new branch on the growing tree of the Withers family.

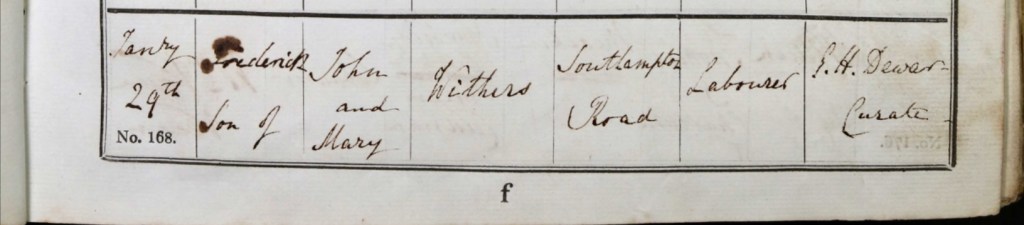

By the winter of 1837, the Withers family once again found themselves gathered within the great stone heart of Romsey Abbey. Another son had come into their lives, Frederick Withers, born amidst the slow, cold days when the fields lay bare and the mists clung low to the River Test.

On Sunday, the 29th day of January, John and Mary Withers carried little Frederick into the Abbey’s ancient nave, their footsteps echoing against the worn stone floors. There, under the gaze of saints carved in old wood and lit by the fragile light of the season, they offered their son for baptism. Stipendiary Curate Edward Henry Dewar presided that day, a young clergyman of remarkable journey and promise, who recorded solemnly that Frederick, son of John Withers, labourer, and Mary Withers of Southampton Road, was baptised into the life of the Church.

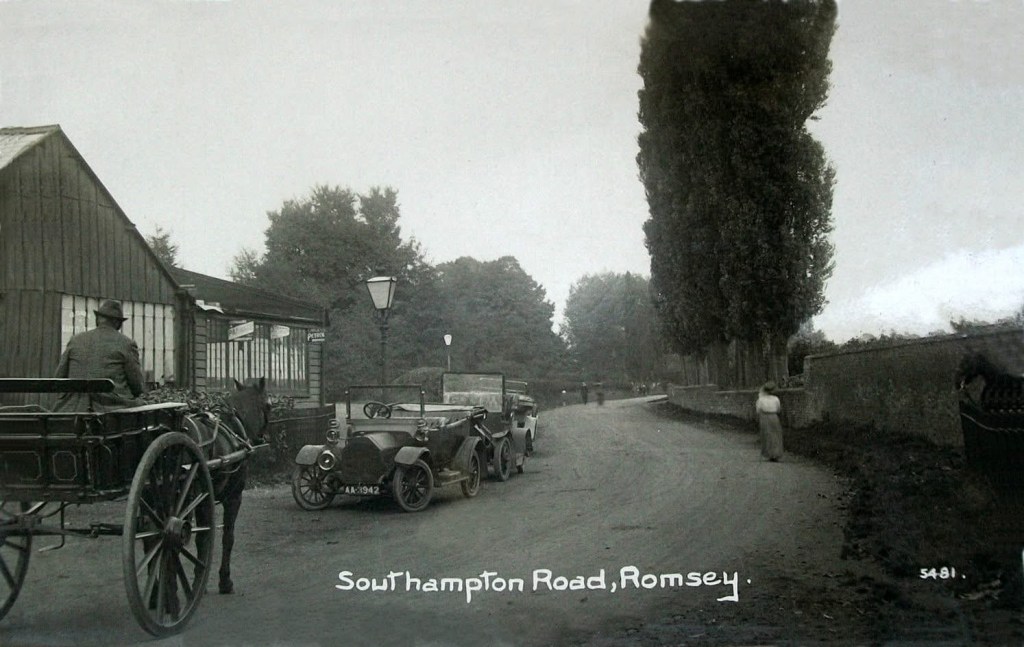

This baptismal entry offers another quiet glimpse into the Withers family's life. By now, it seems, they had settled along Southampton Road, a place of comings and goings, where wagons and foot traffic bound for the bustling port town would pass. John was still recorded simply as a labourer, a man whose days were likely spent in hard work, tending fields, repairing roads, or laboring wherever hands were needed most. Life was not easy, but it was rooted in the dignity of honest toil and the rhythms of the land.

The man who baptised Frederick was himself a bridge between worlds. Born across the Atlantic in Amherstburg, Canada, Edward Henry Dewar had known many landscapes and many tongues before he came to Romsey. Educated among the scholars of Frankfurt and Oxford, Dewar carried with him a mind sharpened by study and a heart turned toward service. He had been appointed to Romsey Abbey only two years before, stepping into a town that was itself straddling the old ways and the new, where markets still bustled beneath the Abbey’s shadow even as gaslight first began to flicker in the streets.

During his brief time in Romsey, Dewar oversaw small but meaningful changes: bringing light into the Abbey with the new gas lamps, standing beside countless families as they wed, and welcoming infants into the faith with a few careful strokes of his pen. Behind these duties lay a life marked by sorrow and hope; he had married and buried, loved and grieved, even as his own family grew and shifted.

Frederick’s baptism would have been one among many that winter, yet to us it shines like a rare jewel in the grey cloth of history. For in finding that one line in a parish register, it is as though we can still glimpse the day itself, the pale winter light slanting through the Abbey windows, the muffled sounds of the town beyond the heavy doors, the smell of cold stone and candle wax, and a young curate speaking ancient words over a child cradled close in his mother’s arms.

Though Edward Dewar would soon leave Romsey for larger cities and grander posts, Brighton, Hamburg, Ontario, his brief chapter there is bound forever with the quiet lives he touched, including that of little Frederick Withers. And so the story grows: another son to John and Mary, another thread woven into the tapestry of a family who lived, worked, loved, and endured under the changing skies of Hampshire.

Southampton Road in Romsey, Hampshire, England, is a prominent thoroughfare with a rich history dating back centuries. Romsey itself has ancient roots, evidenced by archaeological finds from the Roman and Saxon periods. The town's growth was spurred by its strategic location on the River Test, which facilitated trade and commerce. Southampton Road, as a main artery, played a pivotal role in the town's development, connecting Romsey to Southampton and other nearby settlements.

In the medieval era, Romsey Abbey emerged as a focal point, both religiously and economically, contributing to the town's prosperity. The road would have been crucial for pilgrims and traders visiting the abbey, further enhancing its significance. Over time, Romsey evolved into a market town, with Southampton Road serving as a key route for goods and people.

During the Industrial Revolution, Romsey saw changes that reflected broader shifts in transportation and industry. The road adapted to accommodate increasing traffic and trade demands, aligning with developments across Hampshire and southern England. In the modern era, Southampton Road remains vital, lined with businesses, residences, and community facilities that sustain Romsey's vibrant life.

Today, Southampton Road embodies a blend of historical charm and contemporary amenities, reflecting Romsey's enduring role as a hub of culture, commerce, and community in Hampshire.

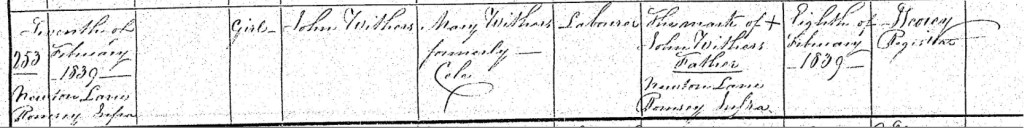

In the early days of February 1839, winter still held Romsey in its quiet, grey grasp when John and Mary Withers welcomed another child into their family. On Thursday the 7th day of February, within the familiar surroundings of Newton Lane, Mary gave birth to a daughter, a delicate new life entering a world shaped by hard work, river mists, and ancient stone.

The very next day, on Friday the 8th, John made his way to the registrar’s office. Perhaps the morning was cold and damp, the streets slick from rain or frost, as John, a labourer with weathered hands and a life measured by toil, stood before Registrar J. Scorey. There, the birth of his daughter was officially recorded. She was entered simply as "Withers, a girl," daughter of John Withers, labourer, and Mary Withers, formerly Cole, of Newton Lane, Romsey Infra. John made his mark on the document, a simple "X", a silent testament to the countless working men and women of that era who built their lives on strength rather than letters.

Yet, strangely, no name was given for the baby girl. No Virtue Anna written carefully into the register, no formal christening of her spirit with the name her parents must have whispered to her in the small hours at home. The absence of her name on that first, stark record invites a thousand tender questions. Had Mary and John not yet decided upon the right name? Was the child frail, perhaps clinging precariously to life, and her parents hesitant to hope too much too soon? The birth had been registered with unusual haste, barely a day after her arrival, a swiftness that speaks, maybe, of urgency or fear.

We can only speculate. The paper trail gives no clear answers, only a faint outline of love and uncertainty drawn in ink nearly two centuries ago. There is no record of a death that might suggest another lost child. No alternative birth in the indexes to suggest confusion. It seems most likely that this little girl, whose early days were perhaps shadowed by fragility, grew to bear the name Virtue Anna Withers, a name that would later echo through the life of her family.

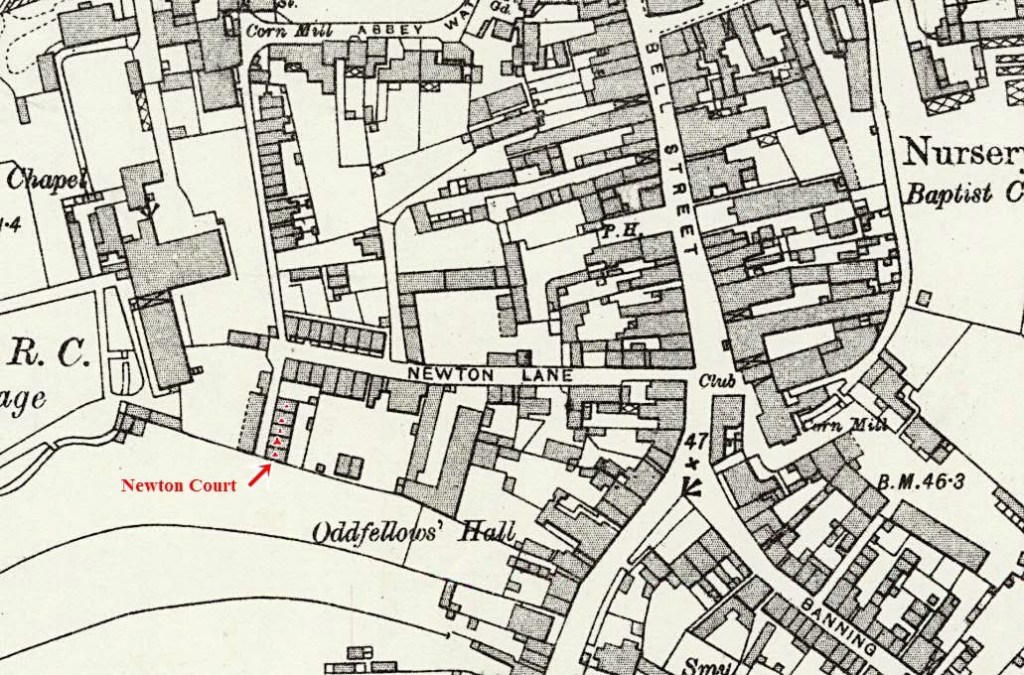

Newton Lane itself was a world unto its own in those days. One of Romsey's oldest streets, winding close to the silver thread of the River Test and the once-busy Romsey Barge Canal, Newton Lane had long been shaped by water and work. Bargemen and barge drivers lived along its length, carrying the town’s fortunes on their broad shoulders and narrow boats. The Withers family, too, was rooted in this life, their days intertwined with the slow rhythms of river trade and labour.

Newton Lane, would have been alive with the sounds of daily life, the crack of wagon wheels, the lowing of cattle bound for market, the murmur of the river never far away. And in one small, worn house along that lane, a baby girl named Virtue Anna would begin her life’s journey, cradled by parents who, despite hardship and uncertainty, chose for her a name filled with hope, strength, and grace.

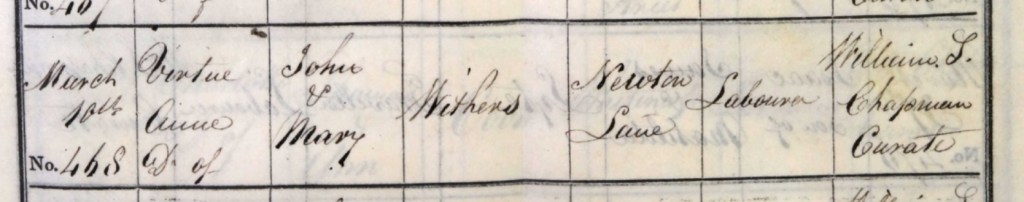

As the first hints of spring stirred the bare trees and softened the fields around Romsey, John and Mary Withers carried their young daughter to the great doors of Romsey Abbey. It was Sunday, the 10th day of March 1839, and the bells of the ancient church would have rung across the town, calling the faithful to worship, just as they had for centuries. Within those stone walls, beneath the heavy arches and quiet light, baby Virtue Anna Withers was baptised.

It was Curate William Sparrow Chapman who took her in his arms that day, the solemn beauty of the baptismal rites unfolding with words that had echoed through generations. In the register, he carefully recorded her details: Virtue Anna Withers, daughter of John Withers, a labourer, and Mary Withers of Newton Lane.

It is a simple entry, yet how much life it quietly contains. After the early fears at her birth, the swift registration, the missing name, here, in the shelter of the Abbey, Virtue Anna was formally welcomed into the community, her name spoken aloud in a holy place, woven into the story of her family and town.

William Sparrow Chapman himself was a man whose character was marked by both learning and kindness. Born on the 12th of July 1810, the son of George Chapman of Micheldever, William was nurtured in a tradition of service and faith. Ordained deacon in 1834 and priest a year later, he had already served four tender years as Curate at Enstone in Oxfordshire before arriving in Romsey. His time at Enstone had left an indelible mark, so much so that when he left, the parishioners, rich and poor alike, pressed into his hands a beautiful gift of silver: candlesticks, snuffers, a tray, and a tea set, tokens of affection that spoke louder than words.

By 1839, Chapman had made Romsey his charge. His voice would have been a familiar one in the Abbey’s great nave, his sermons weaving comfort and challenge into the lives of those who listened. His tenure was brief but deeply felt. Later, he would go on to become the Vicar of Kemble in Wiltshire, serving there with devotion until his death in 1861. Even now, within Romsey Abbey, a memorial plaque remembers the good he did, a quiet witness to a life lived faithfully.

On that day in March, Curate Chapman placed his hand upon Virtue Anna’s brow and blessed her, a tiny soul cradled by ancient stone, young parents, and an old town that bore the memory of countless such baptisms before hers. It was a beginning, a claiming, not just for Virtue Anna, but for all who came after, searching the faint trails left behind, piecing together the fragile, beautiful puzzle of a family’s life long ago.

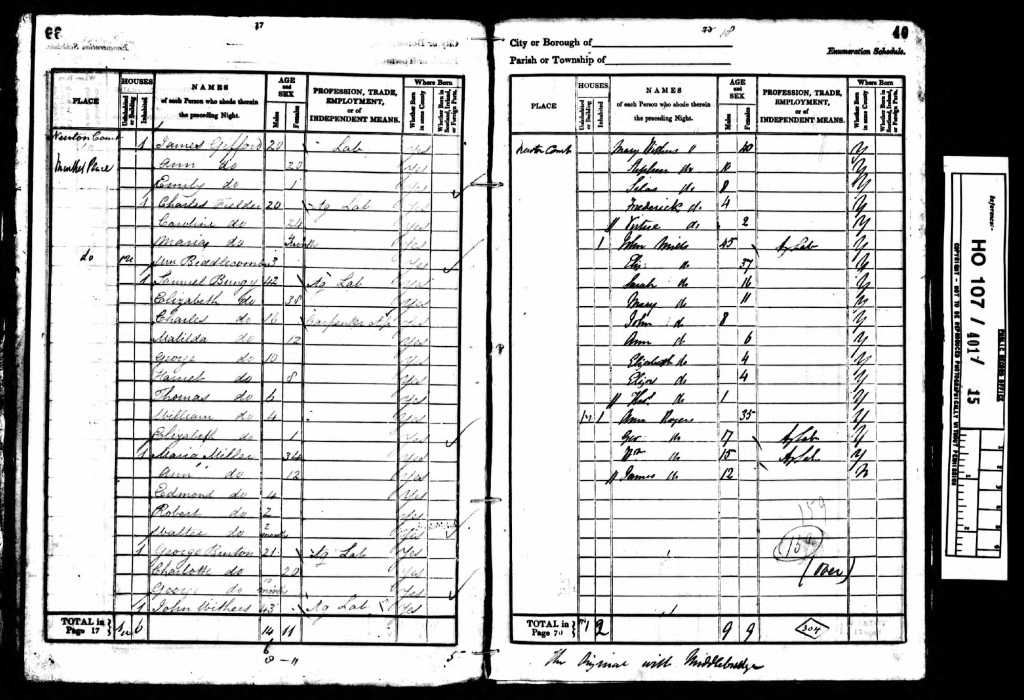

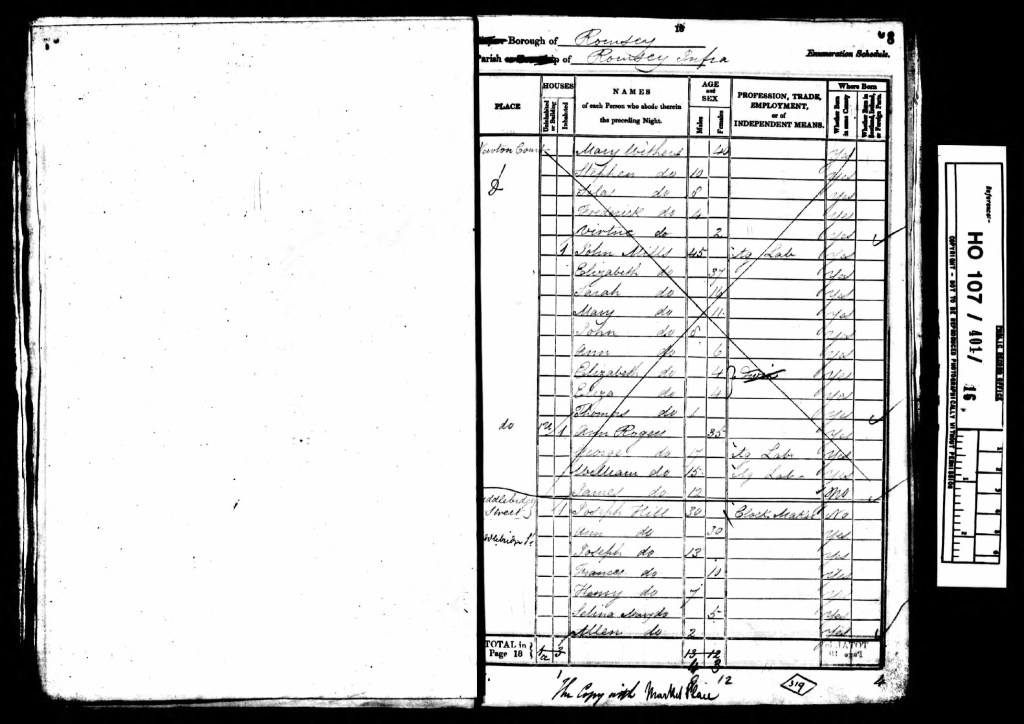

As the long evening of Sunday the 6th day of June 1841 settled over Romsey, the soft hush of summer brushed through Newton Court, carrying the scents of tilled earth and distant meadows. Inside their modest home, ten-year-old Stephen Withers sat with his family, their lives quietly etched into the first full population census that Britain would keep.

There they are: Stephen, his father John, now forty-three, his mother Mary, just turned forty, his younger brothers Silas, aged eight, little Frederick, barely four years old, and tiny Virtue, only two. A simple household on the edge of a small town, one of thousands across England, yet to me, it feels as though their names burn a little brighter than the rest, shining through the haze of years.

John’s occupation was given plainly enough: agricultural labourer. A man of the land, his back bowed to the rhythm of the seasons, working the fields that rolled beyond Newton Lane, tending to the endless cycle of sowing and harvest that sustained both town and family.

And yet, as often happens when piecing together the fragile record of lives past, a small mystery tugs at the heart of the story. Two census returns survive for the family that night. In one, John is listed faithfully among them, the head of the household, the steady hand. In the other, he is strangely absent, as if the ink that should have marked his place was somehow washed away by time. Was it a simple clerical error, a hurried copyist’s slip, or something more? Was John perhaps working late in the fields or called away at the last moment? We cannot know for certain. The past, it seems, sometimes leaves us only questions where we long for answers.

Still, in both records, the heart of the family beats steadily. The young Withers children, gathered close, their mother Mary anchoring them all with quiet strength. And Stephen, standing at the threshold of boyhood and manhood, beginning already to learn what it would mean to work, to endure, and to belong to a world that asked much and promised little.

Through a single evening’s snapshot, blurred and imperfect though it may be, we glimpse them. Not as names on a page, but as living souls, breathing the same warm June air, dreaming under the same old Romsey sky.

Newton Court, located on Newton Lane in Romsey, Hampshire, has now been demolished. While specific historical records about Newton Court are limited, its presence on Newton Lane, a street with a rich architectural heritage, suggests it may be part of the area's historical fabric.

Newton Lane itself is home to several listed buildings, including a Grade II listed structure known as the "East to West Wing Behind Number 31," which was designated in 1972. This indicates the historical significance of properties along the lane.

In recent years, Newton Lane has seen developments that blend historical preservation with modern living. For instance, a semi-derelict building, formerly a carpet shop, was converted into three contemporary dwellings with courtyard gardens, respecting the conservation area's character.

Today, Newton Lane comprises a mix of residential properties, including houses and flats, reflecting both its historical roots and modern adaptations. The area remains a sought-after location within Romsey, balancing heritage with contemporary living.

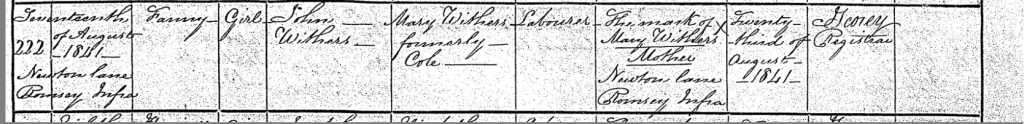

On a warm summer’s day, Tuesday the 17th day of August 1841, a new life entered the world in the quiet lanes of Romsey. Fanny Withers, a daughter, was born to John and Mary at their home on Newton Lane. She was the youngest yet, a new light in their growing family. Just a few days later, on the 23rd day of August, Mary, her mother, took the delicate step of registering Fanny’s birth in Romsey, a task that would forever mark the moment in history.

The birth register, inked in precise but simple letters, recorded: Fanny Withers, a girl, the daughter of John Withers, a labourer, and Mary Withers, formerly Cole, of Newton Lane, Romsey. Mary, her mother, signed the document in the only way she could, with her mark, an “X,” a symbol of the life she had lived and the strength she carried in quiet, everyday ways.

It’s easy to imagine Mary in those days, perhaps tired after giving birth to yet another child, but ever resolute in fulfilling her role. A mark, an “X,” that could stand for so much more than just a signature. It is a testament to her resilience, to the way she navigated the world with limited means, but always with an indomitable spirit. Though her name may not have been written in flowing script, her presence in this record is undeniable.

And little Fanny, just a baby, was added to the growing tapestry of the Withers family, a family tied to the land, to the rhythms of work and home, and to the quiet promise of another generation. In the years that would follow, Fanny would grow up alongside her siblings, Stephen, Silas, Frederick, and Virtue, in the heart of Romsey, a small town that had seen many lives, many births, many hopes. But on that day in 1841, the future was still unwritten, and the world was wide open for Fanny, a small girl who would one day carry the name of Withers into the unfolding story of the family.

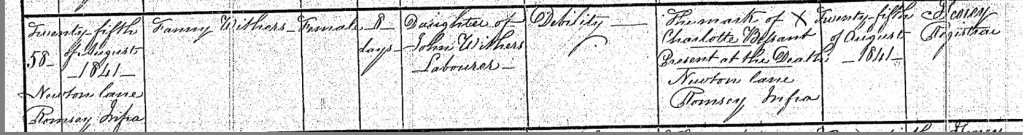

Just eight days after her birth, little Fanny Withers, the newest light in the Withers family, was taken from this world. On Wednesday, the 25th day of August 1841, she passed away in the home on Newton Lane, Romsey, where she had been born.

Her death was recorded with a heavy heart, as was the custom of the time, and the words written in the register reflect a quiet sadness. An infant, so tiny, so fragile, with a life so short that it seemed barely begun. The registrar, whose name has been lost to time, noted simply that Fanny had died of Debility, a word that in itself speaks of the fragility of early life, of bodies too weak to withstand the trials of the world.

Charlotte Bessant, a resident of Newton Lane, was present at Fanny's death, a witness to the sorrow of the Withers family, and it was Charlotte who, with a simple mark of an “X,” signed the death certificate, a silent gesture that connected her to this family’s grief.

It is heart-wrenching to think of Mary, Fanny's mother, enduring the loss of her daughter so soon after her birth. The grief must have been deep, the pain unspoken yet felt in every corner of their home. For a mother, to lose a child, especially one so young, so full of potential, is a sorrow that echoes across generations.

Though Fanny’s life was short, it leaves an indelible mark on the family story. Her passing is a reminder of the fragile nature of life in those days, where every joy was tempered with the ever-present shadow of loss. The Withers family would carry the memory of their lost daughter, a brief but meaningful part of their lives, etched forever in the records that survive. And in the passing of this tiny soul, there is a quiet acknowledgement of love, loss, and the passage of time.

Debility refers to a state of physical weakness or frailty, often resulting from prolonged illness, aging, or certain medical conditions. It is a term historically used to describe a general lack of strength or vitality in the body. Debility could manifest in various ways, such as extreme fatigue, reduced mobility, and an overall inability to perform daily tasks that require physical exertion. The causes of debility are numerous and can range from chronic diseases like tuberculosis or heart conditions to nutritional deficiencies, mental health disorders, and other debilitating conditions.

In the context of 19th-century medicine, debility was often used as a diagnosis for a wide range of symptoms that doctors might have trouble attributing to a specific illness or condition. It was a common diagnosis for patients who presented with prolonged tiredness or weakness without a clear cause. People suffering from debility in the 1800s often had to endure long periods of bed rest or confinement, and treatment for this condition was largely based on rest, diet, and sometimes the use of tonics or other herbal remedies believed to restore energy and strength.

The perception of debility varied depending on the social and economic context. For the wealthy or middle class, debility might have been seen as a sign of overwork, stress, or indulgence, as well as an indicator of the need for rest or rejuvenation through travel or a change of environment. For the poor or working class, debility was often a result of harsh working conditions, poor nutrition, or lack of proper medical care. In those days, the poor were more likely to experience long-term illnesses that drained their energy, and debility in this population was often a consequence of these social and economic disadvantages.

In modern times, the term debility is less commonly used, replaced by more specific medical diagnoses that describe the underlying causes of the condition, such as chronic fatigue syndrome, muscular dystrophy, or post-viral syndrome. However, the general concept of debility, as a result of illness, injury, or old age, still remains relevant in the context of healthcare and the management of chronic conditions.

In the past, the treatment for debility involved a combination of rest, a balanced diet, and various medical remedies aimed at improving physical strength and stamina. However, these treatments were often inadequate for people suffering from conditions that required more targeted care. The death rate from conditions that led to debility was higher in earlier centuries because of limited medical knowledge and the lack of effective treatments for chronic conditions.

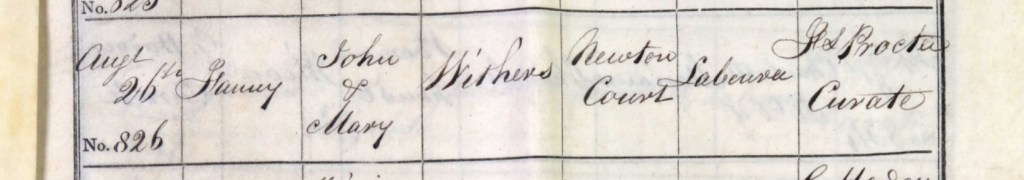

The tragic loss of little Fanny Withers is marked in the most poignant of ways, by the baptism that took place the day after her death. On Thursday, the 26th day of August 1841, Fanny was baptised at Romsey Abbey, just one day after her passing. The decision to baptise her so close to her death reflects the deep love and devotion of her parents, John and Mary, as they sought comfort in their faith and gave their daughter what could be her final blessing.

Curate Francis Procter, who had overseen many baptisms at the Abbey, was the one to perform this service for Fanny. In the burial register, Procter noted that Fanny Withers, daughter of John and Mary Withers of Newton Court, was baptised on that day, August 26th, 1841. The very same day that her small body would be laid to rest, her spirit was tenderly welcomed into the fold of the Christian faith, a ritual of comfort and solace amidst the overwhelming grief.

Francis Procter himself had a distinguished career within the Church. Ordained as a deacon in 1836 and as a priest in 1838, Procter served at Romsey Abbey from 1840 until 1842. His time at the Abbey was one of compassion, guiding the congregation through moments of joy and sorrow alike. But, after his time in Romsey, Procter chose to step away from parochial ministry and took on an academic role as a fellow and assistant tutor at St Catharine's College in Cambridge. Eventually, he would return to parish life as the Vicar of Witton in Norfolk, where he served until his death. While his career moved on to different paths, it’s clear that his time at Romsey Abbey, and especially his involvement in the Withers family’s journey, remained significant to both his ministry and the community he served.

For John and Mary, the baptism of their daughter was both an act of faith and an expression of love in the face of overwhelming sorrow. It’s a reminder that, even in the briefest of lives, the bonds of family and faith endure, and their echoes stretch across time.

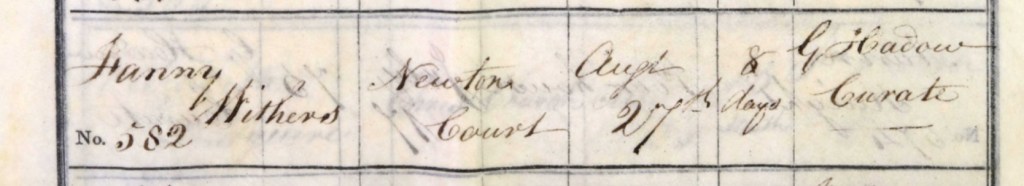

The passing of young Fanny Withers, just eight days after her birth, is a heartbreaking chapter in the Withers family’s story. On Friday, the 27th day of August 1841, Fanny was laid to rest, either in the hallowed grounds of Romsey Abbey or at the Romsey Old Cemetery on Botley Road, where many of Romsey’s residents found their final resting place. The exact location of her grave remains uncertain, but what is known is that her brief life left a lasting imprint on the hearts of her family and the community.

Curate G. Hadow, serving at Romsey Abbey, performed Fanny’s burial service and recorded the event in the Abbey’s burial register. The entry notes that Fanny Withers, the infant daughter of John and Mary Withers from Newton Court, was laid to rest on the 27th of August, 1841, a day after her baptism. Her loss, so deeply felt, was marked with the solemn dignity of a Christian burial, a final act of love and remembrance for a life that had been so fleeting.

In this moment of grief, we are reminded of the profound bond between family and faith. For John and Mary, the pain of losing their daughter must have been unbearable, yet their devotion to her life, however short, was unwavering. They gave her the comfort of baptism, and in return, Fanny was given a place of rest, surrounded by the beauty and history of Romsey. Though her time in the world was brief, her story is forever woven into the tapestry of the Withers family history, a poignant reminder of the fragility of life and the enduring strength of love.

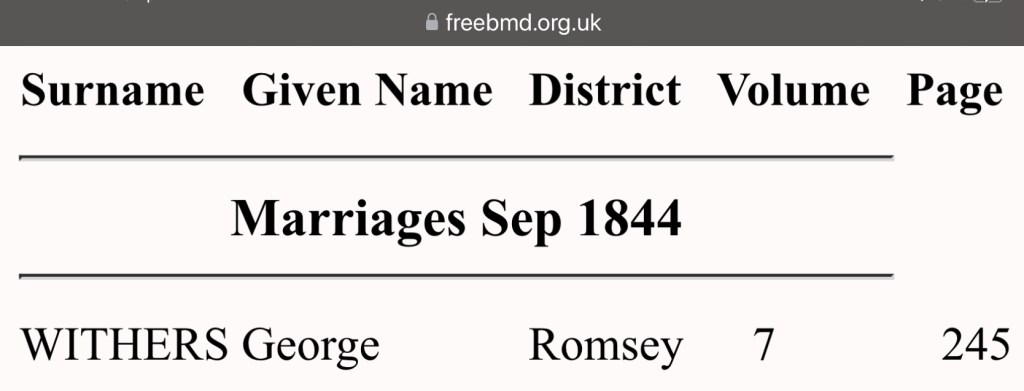

Stephen’s brother, Twenty-three-year-old George Withers married widow Jane Small, formerly Mitchell, in Romsey, Hampshire, England, on Sunday, the 28th day of July, 1844. As with other parts of this life story, I want to be open and honest with you. Due to the ever-increasing costs of research, subscription fees, and the sheer number of certificates needed for each individual, I have had to make the difficult decision, through gritted teeth, not to purchase every marriage certificate, including George and Jane’s. It is a decision I have not made lightly. I feel the absence of these documents keenly, as my heart wants every story to be complete and fully documented, but the realities of cost and the need to continue writing the broader tapestry of my family's history have forced my hand. I am truly sorry and hope you can understand the position I am in. For those who would like to have an official copy of George and Jane’s marriage certificate, it can be ordered using the following General Register Office reference: Gro Ref - Marriages, September Quarter, 1844, WITHERS, George, SMALL, Jane, Romsey, Volume 7, Page 245. Even without every document in hand, George’s story, and indeed Stephen’s, will continue to be told with as much heart, care, and respect as possible.

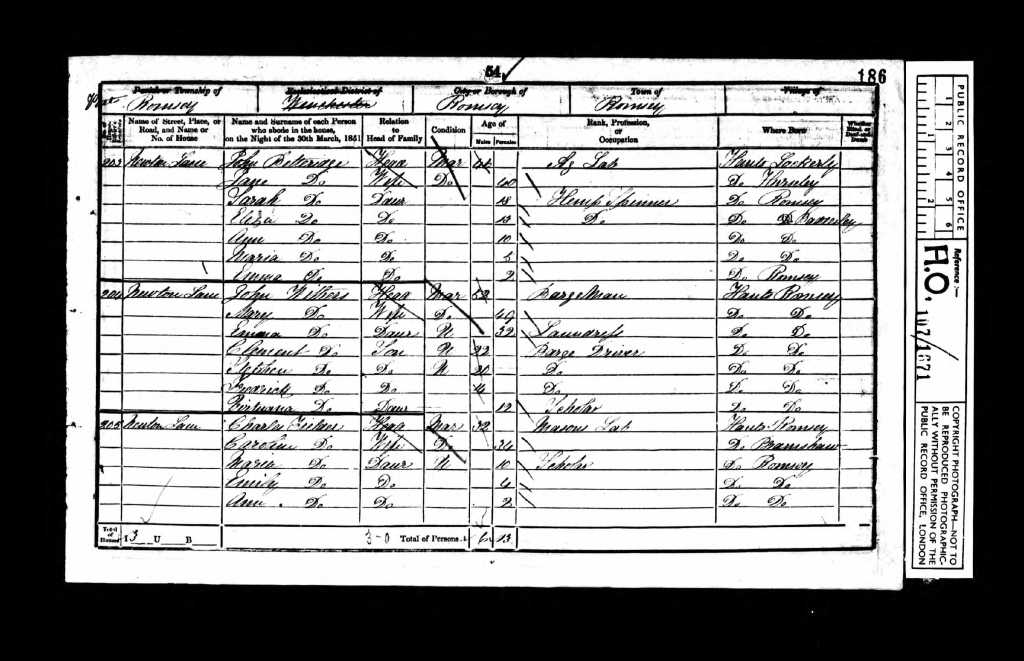

On the eve of the 1851 census, Sunday the 30th day of March, 20-year-old Stephen, his parents 52-year-old John and 49-year-old Mary, and his siblings Emma, aged 32, their sons Clement, aged 22, Frederick, aged 14, and his youngest sister, Virtue, aged 12, were residing at Newton Lane, Romsey, Hampshire, England. John was working as a bargeman, a profession that tied him closely to the waterways running through the heart of Hampshire. Emma earned her living as a laundress, while Stephen, Clement, and Frederick followed in their father’s footsteps, working as barge drivers. Virtue, still just a young girl, was attending school as a scholar, preparing for whatever future lay ahead. Their lives, though modest, were clearly built on hard work, family ties, and a quiet resilience rooted in the rhythms of daily life along the river.

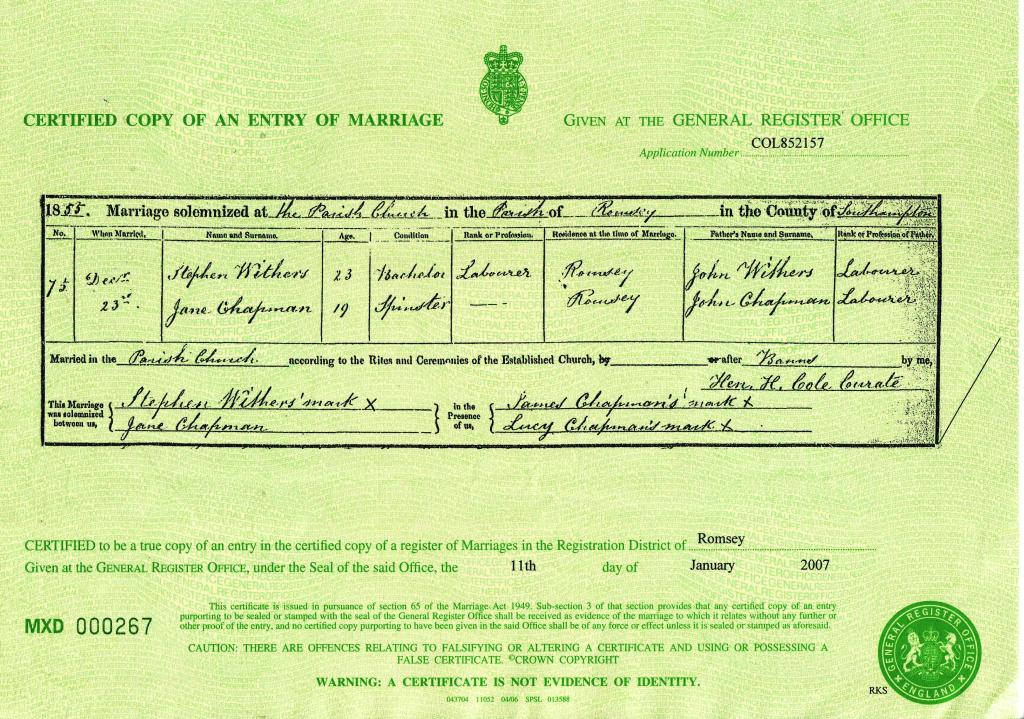

By the age of 23, bachelor Stephen Withers, a labourer from Romsey, fell in love and married 19-year-old spinster Jane Chapman, also from Romsey, on Sunday, the 23rd day of December 1855, at Romsey Abbey, Romsey, Hampshire, England. Curate Henry H Cole performed the ceremony and recorded their information in the marriage register. He noted that Stephen was the son of John Withers, a labourer, and Jane was the daughter of John Chapman, a labourer. Their witnesses were James and Lucy Chapman, who both signed their names with their mark, an "X." Stephen also signed with his mark, an "X."

Romsey Abbey, located in the heart of Romsey, Hampshire, is a significant and historic site with a rich and layered past. Originally built as a Saxon nunnery in the 8th century, it was founded by King Henry I in 907 AD as a Benedictine abbey. The abbey later became a priory and was associated with the prestigious order of St. Benedict. Over the centuries, the abbey was expanded and renovated, eventually becoming the magnificent structure seen today. The abbey's architectural style reflects its long history, incorporating elements from the Saxon, Norman, and later periods.

During the medieval period, the abbey played a central role in the religious and cultural life of the community. It became a place of pilgrimage, attracting many visitors due to its spiritual significance. In 1539, as part of the dissolution of the monasteries under King Henry VIII, the abbey was closed, and its lands and property were seized by the crown. However, the abbey church was spared demolition and was repurposed as a parish church, continuing to serve the local community.

Romsey Abbey is particularly known for its stunning architecture, including its soaring nave and intricate stained glass windows, which have been preserved and are still admired today. The abbey's grounds are also home to a range of historical features, such as ancient tombs and memorials to local dignitaries. It is not only an important religious site but also a cultural landmark for Romsey, representing centuries of history.

One of the more mysterious aspects of Romsey Abbey is the presence of underground tunnels. These tunnels are believed to date back to the abbey's monastic origins and were likely used for various purposes, such as transporting goods, accessing secret rooms, or even as escape routes in times of trouble. Local legend suggests that some of these tunnels stretch beneath the town, linking the abbey to other important buildings in the area. While the exact purpose of the tunnels remains unclear, they have become the subject of fascination and speculation over the years. The entrances to these tunnels are said to be hidden, and some stories suggest that they were sealed off long ago, further fueling the air of mystery surrounding them.

In addition to the tunnels, Romsey Abbey is also known for its supposed hauntings. Over the centuries, there have been numerous reports of strange occurrences within the abbey's walls. Visitors and staff have claimed to hear unexplainable footsteps echoing through the nave, the faint sound of chanting, and even sightings of spectral figures. One of the most well-known ghosts associated with the abbey is the spirit of a former monk, said to roam the church at night. This apparition is often described as a cloaked figure who vanishes when approached. Some believe that the haunting is connected to the abbey's turbulent history, including the dissolution of the monasteries and the many lives lost during those times of upheaval.

Romsey Abbey also has its share of myths and legends. One tale involves the "Golden Cup," a legendary artifact that was said to have been hidden within the abbey during the medieval period. According to the myth, the cup contained great spiritual power, and many sought to find it. However, the cup was never recovered, and it is said to have been lost in the depths of the abbey's secret passages and tunnels. The myth of the Golden Cup has added to the sense of intrigue surrounding the abbey, and it remains a popular story among locals and visitors alike.

Throughout its history, Romsey Abbey has been home to many notable figures, but perhaps the most prominent clergyman associated with the abbey is Canon H.P. Evans, who served as the rector in the early 20th century. Canon Evans was known for his deep dedication to the church and his efforts to restore and preserve the abbey, ensuring that it remained an active and vibrant place of worship. Under his leadership, significant repairs were made to the abbey's structure, and the church continued to play a central role in the life of Romsey. His work is remembered fondly, and he is often credited with saving the abbey from decline.

Today, Romsey Abbey stands as a testament to the area's rich history, attracting visitors from all over the world who come to admire its architecture, learn about its past, and perhaps experience some of the mysteries that have surrounded it for centuries. Whether you are drawn to its history, its spiritual significance, or the tales of ghosts and hidden tunnels, Romsey Abbey offers a fascinating glimpse into the past.

As I close this first part of Stephen's story, I am reminded of the quiet resilience that defined his life and the lives of those who came before him. Through the documents and records, we glimpse the humble yet profound journey of a man whose life was shaped by hard work, love, and the bonds of family. While we may not have every certificate or every answer, the story we have gathered so far is one of steadfastness, connection, and a deep-rooted sense of place.

This story is not just about names and dates, but about the people behind them, their struggles, their dreams, and the marks they left on the world. Stephen, like many of us, was a product of his time and circumstances, yet his story, like so many others, continues to live on through these records. Each detail, no matter how small, weaves together the fabric of his life and the lives of those around him, creating a legacy that transcends the years.

I hope that as you read through these pages, you can feel the heartbeat of the past, not just in the facts and figures, but in the quiet moments of love, loss, and perseverance that resonate across the generations. This is only the beginning of Stephen's story, and I look forward to continuing this journey through the records and memories that will bring more of his life into the light. Thank you for joining me in this exploration of the past, and for allowing me to share this deeply personal and meaningful history with you.

Until next time, Toodle pip,

Yours Lainey.

🦋🦋🦋

I have brought and paid for all certificates,

Please do not download or use them without my permission.

All you have to do is ask.

Thank you.