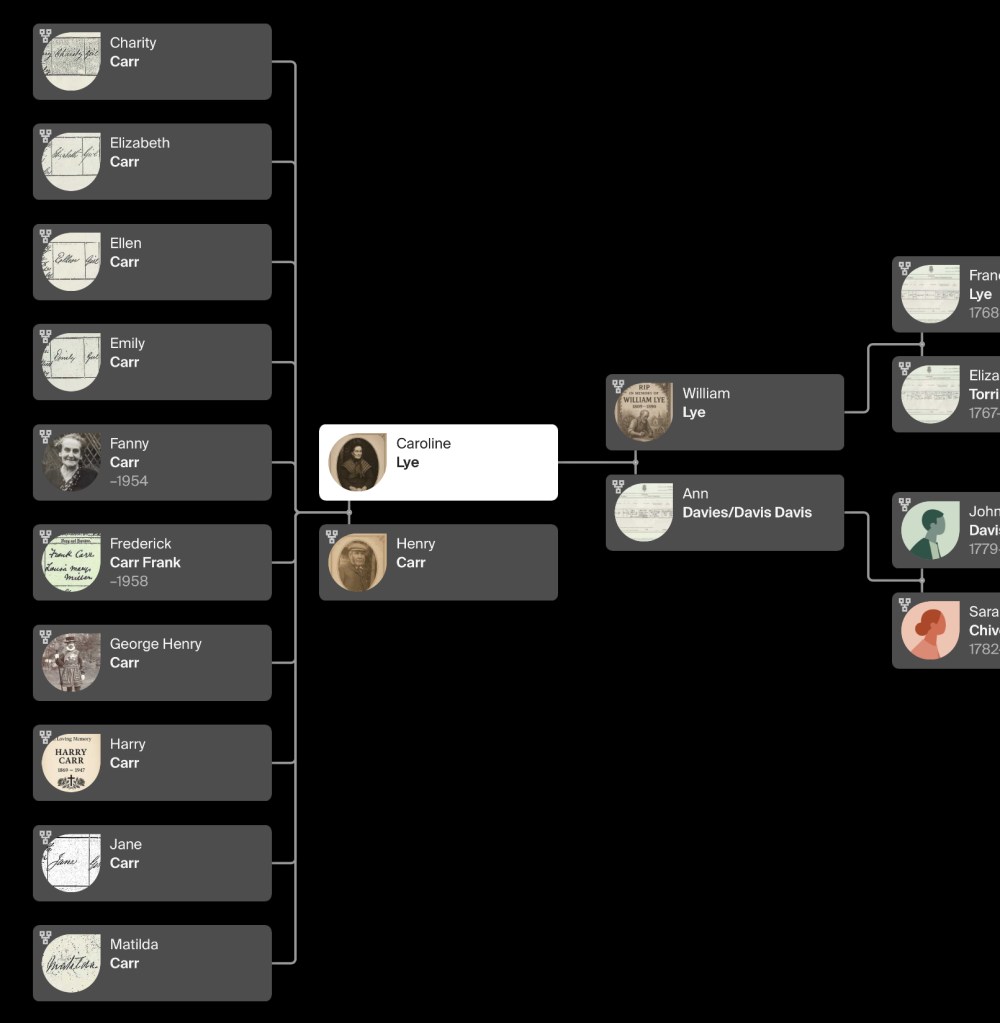

As we turn the page to the second chapter of Caroline Lye's life, we step into a world where love, loss, and the passage of time unfold with quiet grace and undeniable strength. "The Life of Caroline Lye 1831–1912: Until Death Do Us Part Through Documentation" is a journey through the years that shaped Caroline into the woman who would bear witness to both the joys and sorrows of family, a woman whose legacy is etched in the very fabric of her descendants' lives.

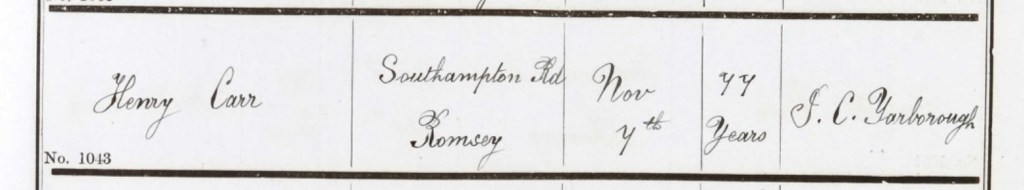

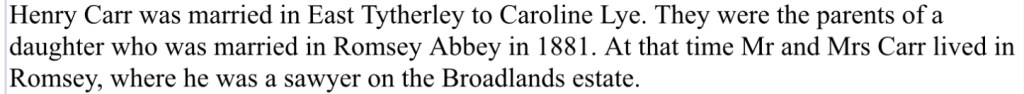

After the vows exchanged on the 3rd day of October, 1850, at St. Peter’s Church, Caroline began her new life as a wife, with all the promise and uncertainty that marriage brings. In the arms of her husband, Henry Carr, she found both a partner and a new chapter, one where the quiet joys of shared moments would be woven into the tapestry of her family’s story. Together, they built a life, with all its complexities and beauty, as they navigated the challenges of rural England in the 19th century.

But as the years passed, the life Caroline had begun with Henry was marked by both triumphs and hardships, and in every chapter of her life, the world around her was shifting. Through the trials of motherhood, the moments of celebration, and the inevitable losses that come with age, Caroline’s story continued, her resilience, faith, and love at the heart of it all. The documentation that follows is not just a record of dates and events; it is a testament to the quiet strength of a woman who faced the passage of time with courage and grace, whose life continues to resonate through the lives of those who came after her.

In this second part of Caroline’s journey, we will walk alongside her through the years, tracing the steps of a woman whose life, though deeply rooted in the simplicity of her time, was rich with meaning, with connection, and with an enduring legacy of love. We will see her through the documents that recorded her life. And as we reflect on her life from her marriage to her final days, we will honor not only the woman she was but the story she left behind, one that still breathes in the hearts of those who carry her name.

Welcome back to the year 1851, Lockerley, Hampshire, England. The year finds the country in a time of both progress and stark contrast, reflecting the complex social and economic landscape of Victorian England. At the top of this changing society stands Queen Victoria, who ascended the throne in 1837. Her reign, which would last until 1901, is marked by great social and technological transformation. By 1851, she had already firmly established herself as a symbol of British imperial strength and moral propriety. Her personal influence, as well as the expanding British Empire, set the tone for the country's ambitions.

In the political realm, the Prime Minister in 1851 was the Conservative politician, the Earl of Derby, who had taken office for his first term in 1852. His party’s influence was significant, although it was a period when political shifts were occurring due to rising calls for social reforms and changes to the British electoral system. The Whigs, a more liberal political faction, had seen their power rise in previous decades, but it was now the Tories who held sway, navigating the complex balance between reform and tradition.

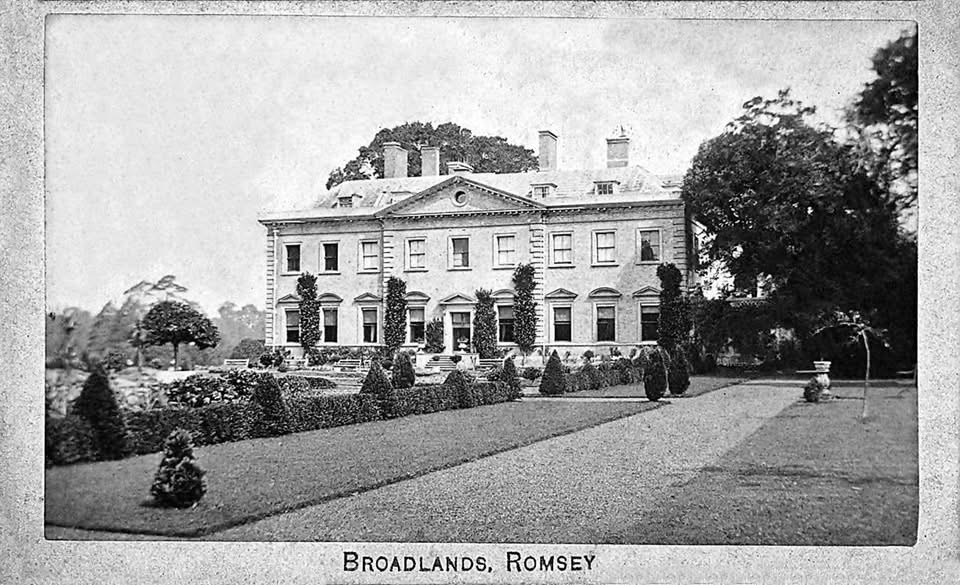

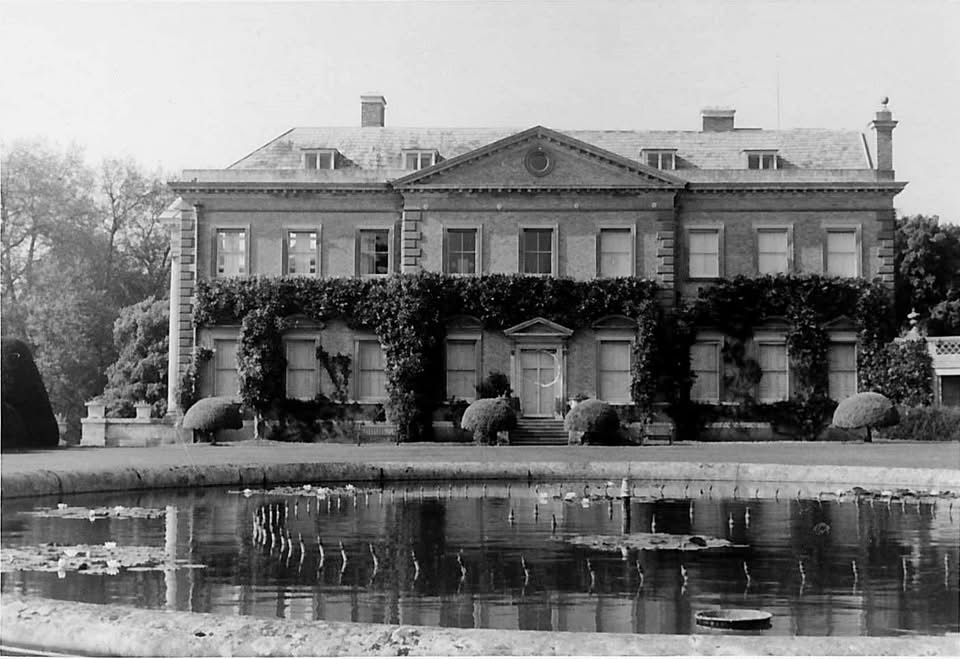

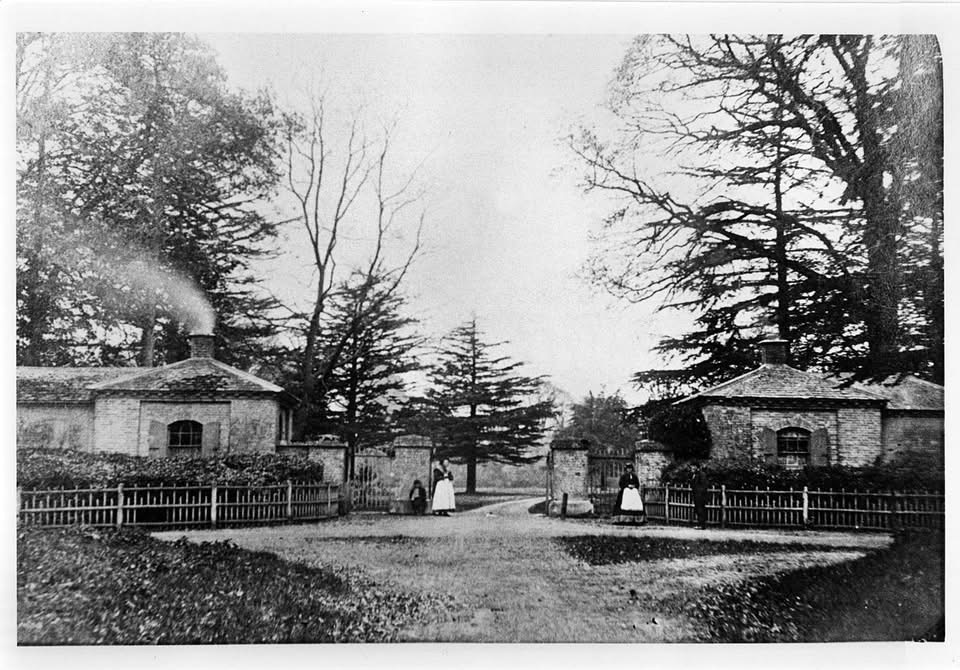

The parliamentary landscape was slowly evolving, though the political system in 1851 still reflected the influence of the aristocracy and landowners. The Reform Act of 1832 had made some strides toward greater representation, but it was still a time when only a small percentage of the population had the right to vote. Most working-class people, particularly in rural areas like Lockerley, were excluded from direct political participation. The gaps between the classes were significant, with the aristocracy and wealthy landowners commanding the most power, while the growing industrial middle class and the working class often had limited influence. In the countryside, the divide between the rich and the poor was particularly pronounced, with the wealthy residing in grand estates, while the majority of people in villages like Lockerley lived in modest cottages or on farms, often struggling to make ends meet.

The year 1851 is a time of great contrasts between the rich, working-class, and poor. The rich lived in luxurious mansions or country estates, enjoying the benefits of wealth, education, and social standing. They had the means to travel comfortably, often by private carriage or in the growing network of railways, which began to revolutionize travel in the mid-19th century. The working class, on the other hand, had more limited prospects, working long hours in factories, on farms, or in trades. Their homes were modest, often overcrowded, and not equipped with the comforts that the wealthy enjoyed. At the bottom of the social ladder were the poor, many of whom lived in squalid conditions, particularly in the burgeoning industrial cities where overcrowding and unsanitary conditions led to disease outbreaks. In rural areas like Lockerley, while life was not as harsh as in the urban slums, many people still lived in basic conditions, working on the land for a subsistence income.

Fashion in 1851 was heavily influenced by the Victorian ideal of propriety and elegance, especially among the middle and upper classes. For women, this meant long dresses with high collars, full skirts, and corsets to achieve the desired "hourglass" figure. Dresses were often made of rich fabrics, such as silk and velvet, adorned with lace and intricate patterns. For men, the fashion was more understated but still formal, with tailored suits, waistcoats, top hats, and cravats. Working-class clothing was simpler, made of durable fabrics like wool and linen, and less ornamented. Fashion served as a clear marker of class, with the wealthy able to afford more elaborate and refined styles, while the poor wore what they could afford, often having only one or two sets of clothes.

Transportation in 1851 was undergoing a revolution, with the railway system expanding rapidly. The Great Exhibition of 1851, held in London, showcased not only the achievements of British industry but also the incredible advancements in transportation. For the wealthy, carriages were still the primary means of travel, though railways were increasingly used for longer journeys. In rural areas like Lockerley, travel by horse-drawn cart was the norm for most people, while wealthier families might occasionally travel by train to larger towns and cities. Railways were making travel faster, more efficient, and more affordable, though still out of reach for the poorest in society.

Housing in 1851 was highly stratified. The wealthy lived in grand homes, many of which had elaborate interiors with heated rooms and gas lighting. In contrast, the majority of people, especially the working class, lived in modest cottages, often with little more than basic furnishings and open hearths for warmth. In industrial towns, housing for the working class was overcrowded, with entire families sometimes sharing a single room. In rural areas like Lockerley, people often lived in small, simple cottages made of stone or brick, with thatched roofs or slates. These homes were functional but lacked many of the comforts we take for granted today.

The atmosphere of 1851 was a blend of optimism and anxiety. The Industrial Revolution was transforming England, and the country was experiencing unprecedented growth. There was a sense of progress, especially in the cities, where the rise of factories, new technologies, and modern inventions were changing the landscape. However, the poor living conditions, particularly in the slums, were a stark contrast to the wealth and prosperity of the elite. The vast inequality between the classes was ever-present, and many working-class people began to demand better working conditions, wages, and living standards.

Heating and lighting were rudimentary by modern standards. In the wealthier homes, coal-burning fireplaces provided heat, while gas lighting had started to become more common in urban areas. In rural homes, like those in Lockerley, heating was usually achieved with open fires or stoves, which were often inefficient. Lighting was typically provided by candles or oil lamps. The lack of indoor plumbing meant that water had to be fetched from a well or a pump, and waste was often disposed of in simple privies or cesspits.

Sanitation in 1851 was still in its infancy. In rural areas, the lack of proper sewage systems led to water contamination, and disease outbreaks were common. In the cities, the rapid population growth exacerbated the problem, with cramped living conditions, poor waste management, and limited access to clean water leading to frequent outbreaks of cholera, typhus, and other diseases. The importance of sanitation was just beginning to be understood, but effective systems were still many years away from being fully implemented.

Food in 1851 was largely based on what could be grown locally, especially in rural areas. For the wealthy, meals were abundant and diverse, with access to meats, fruits, and vegetables from both the country and imported goods. For the working class, food was much simpler, with bread, potatoes, and basic meats being staples of their diet. The poor often struggled to afford enough food, and malnutrition was common. The advent of the railways had begun to make food more widely available, but for the majority, meals were basic and focused on sustenance rather than variety.

Entertainment in 1851 was often tied to social class. The wealthy attended the theater, balls, operas, and concerts, enjoying the cultural riches of the time. The working class, however, found entertainment in more communal settings, such as fairs, local pubs, and church gatherings. The Great Exhibition of 1851 was a significant event, bringing the best of British industry and innovation to the public, and marking a moment of national pride and technological marvels.

Diseases were a constant threat in 1851, particularly for the poor. Cholera, smallpox, and tuberculosis were common, and the lack of effective medical treatments meant that many people succumbed to these illnesses. The rise of industrialization and urbanization contributed to the spread of diseases, with overcrowded living conditions creating the perfect breeding grounds for infection.

The environment in 1851 was beginning to show the effects of the Industrial Revolution. In the cities, the air was polluted with smoke from factories, and rivers became contaminated with waste. In the countryside, however, rural life was largely unchanged, with farming continuing as the primary occupation. The rise of factories and coal mining was starting to impact the landscape, and there was a growing awareness of the environmental costs of industrialization.

Gossip and news were vital forms of entertainment and information in 1851, especially in rural communities like Lockerley. With limited access to formal news outlets, people relied on word-of-mouth to share local happenings, rumors, and stories. Newspapers were becoming more widely available, but they were often geared towards the middle and upper classes. In villages, gossip played a central role in the social fabric, as it allowed people to stay connected with the happenings of their community and the wider world.

Schooling in 1851 was still not universal. Education was often determined by social class, with the wealthy able to afford private tutors or send their children to better schools, while the working class often had limited access to education. For the poor, education was often informal and focused on basic literacy and practical skills. It was not until later in the century that compulsory education would become more widespread.

Religion in 1851 remained a central aspect of life for many people, particularly in rural areas like Lockerley. The Church of England was the dominant religious institution, with many people attending services regularly. However, other denominations, such as Methodism, were also growing in influence, especially among the working class. Religion provided comfort, community, and a moral framework for life, and Sunday services were an important social occasion.

In conclusion, 1851 was a time of immense change and contrast. The country was caught between the old and the new, with the industrialization of cities and the continued importance of agriculture in rural areas. The wealthy enjoyed a life of luxury and comfort, while the working class faced difficult living and working conditions. The year was marked by both progress and hardship, with significant advancements in technology, transport, and industry, but also widespread inequality, disease, and social unrest. Life in Lockerley, Hampshire, reflected this broader national experience, as rural traditions continued to coexist with the early stages.

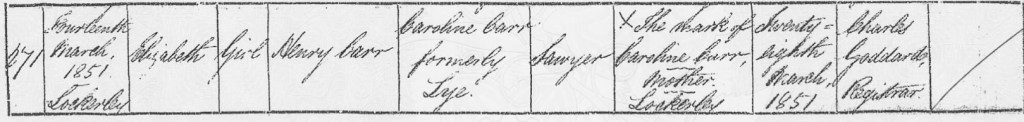

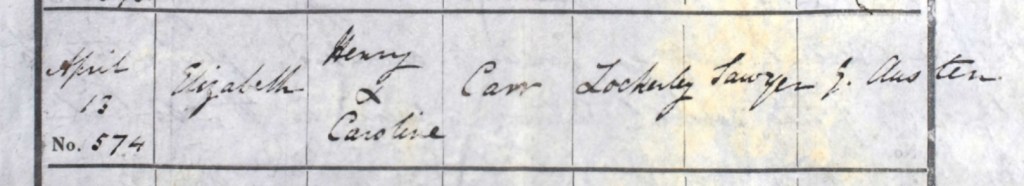

On Friday, the 14th day of March, 1851, Caroline and Henry Carr were blessed with the birth of their daughter, Elizabeth, in the village of Lockerley, Hampshire. This new life, so full of promise, added another layer of joy to their growing family. The arrival of Elizabeth was a moment that would forever mark the Carr household, and her birth set the stage for a new chapter in Caroline and Henry’s lives as parents.

Caroline, with the loving duty of a mother, registered Elizabeth’s birth on Saturday, the 29th day of March, 1851. The registration took place in Stockbridge, where Registrar Charles Goddard carefully logged the details of Elizabeth’s arrival. The official entry in the birth register reads, “On the 14th of March 1851, Elizabeth Carr, a girl, was born in Lockerley, to Henry Carr, a sawyer, and Caroline Carr, formerly Lye, of Lockerley.”

In this simple yet profound record, we see the beginning of Elizabeth’s story, a story intertwined with the legacy of Caroline and Henry. For Caroline, this moment of registering her daughter’s birth was both a legal necessity and an emotional milestone. Her mark, an "X," signed at the bottom of the document, was a quiet reflection of the many sacrifices she made throughout her life, a mother’s strength evident in her enduring care for her children, even if formal education and literacy were not accessible to her.

As Caroline signed this document with her mark, her heart must have swelled with love and hope for her daughter’s future, even as she remained grounded in the humble simplicity of their rural life. Elizabeth, their firstborn, would go on to carry their name, their hopes, and their legacy. The moment of her birth and the documentation that followed would forever be woven into the fabric of Caroline’s own story, a symbol of the continuation of life, love, and family through the generations.

Giving birth in 1851 would have been a vastly different experience for Caroline compared to what we know today. Childbirth in rural England during the mid-19th century was a time of both intimacy and hardship. Caroline, at just 19 years old, would have faced the challenges of a birth without the medical advancements that we take for granted today. There were no pain-relieving medications, no epidurals, and often no skilled doctors or midwives, but rather women like Caroline would rely heavily on the support of close family members, friends, or local women in the community who had experience with childbirth.

Most births took place at home, in familiar surroundings, with the help of a midwife or an experienced woman who was often guided more by tradition than by formal medical training. There were no sterile environments, and the process was full of uncertainty, especially given the high maternal and infant mortality rates of the time. For Caroline, there was likely fear mingled with excitement, but little reassurance from the medical community. The idea of ‘waiting for the doctor’ simply wasn’t an option for many women in rural areas, as doctors were few and far between, and even less accessible for those who were not wealthy.

Motherhood in 1851 would have been a role defined by duty, sacrifice, and constant care. There were no modern conveniences to ease the burdens of daily life. For Caroline, caring for a newborn like Elizabeth would have meant long hours of nursing, washing, and the physical demands of a household. There would have been little time for personal rest, as most women of the time were responsible not only for their children but for maintaining the home. Cooking, cleaning, and even managing the garden would have fallen on Caroline’s shoulders, in addition to caring for her baby.

In many ways, Caroline’s life as a mother would have been shaped by necessity rather than choice. The pace of life was slower, but the work was relentless. Her role as a mother would have been deeply tied to the survival of her family, with her emotional and physical energy focused on providing for her children in ways that were often invisible to the world. There were no modern conveniences like washing machines or electric stoves, every chore was more labor-intensive. Yet, despite the hardships, motherhood was also a deeply communal experience, often shared with other women in the village who had experienced similar struggles and triumphs.

Her role as a mother was one of constant learning, there was little formal parenting advice, and what knowledge there was came from tradition, the wisdom of older generations, and the practical experience of living within a community. The emotional support for Caroline likely came from the women closest to her, and her sense of motherhood was shaped not just by her immediate family but by the larger village network around her. She would have been expected to raise her child with an unwavering sense of responsibility, while also tending to the physical and economic needs of her household.

In many ways, Caroline’s motherhood in 1851 was a quiet but vital force, woven deeply into the fabric of her family’s survival. It was shaped by the limitations and realities of her time, where every day was marked by hard labor, and every milestone with her child was a triumph of strength and endurance. Today, motherhood may be shaped by different challenges, but the emotional core of nurturing and raising a child, as Caroline did, remains timeless.

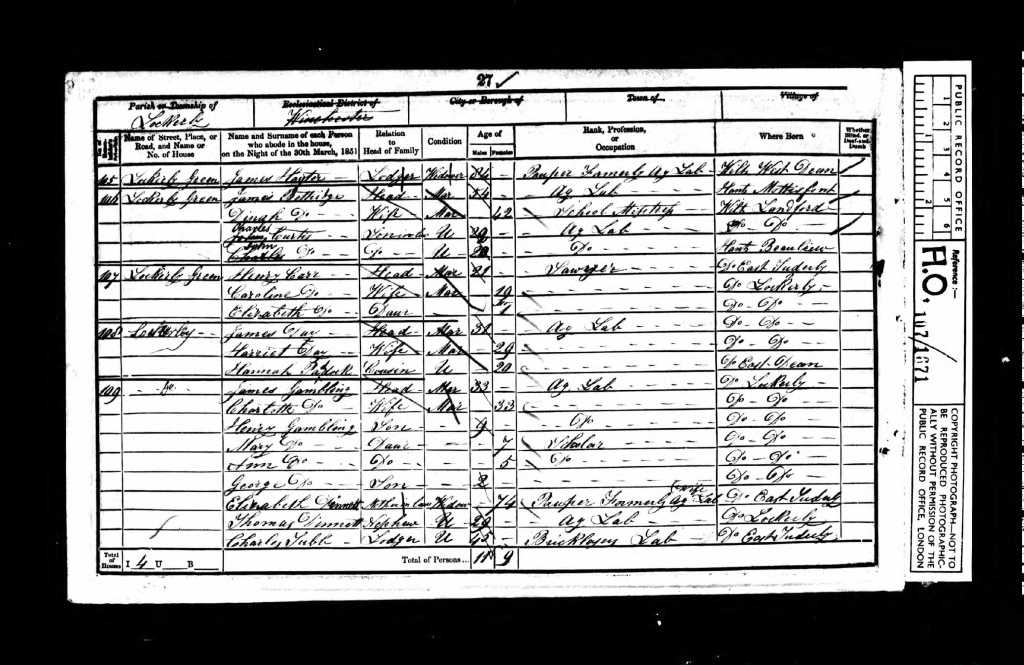

On the eve of the 1851 census, Sunday, the 30th day of March, 1851, Caroline, now 19 years old, and her husband, 21-year-old Henry, found themselves settled in the village of Lockerley, Hampshire, at Lockerley Green. Their lives had taken a new shape, and in this quiet corner of rural England, they were beginning to build their family. Caroline, still a young mother, cradled their newborn daughter, Elizabeth, who had arrived just a month earlier, on the 14th of March.

Henry, following in his father’s footsteps, worked as a sawyer, a trade that was essential in their village. His hands, strong from his work, would shape the timber that built not just the homes of their community but the very foundation of their family’s future. It was a life defined by hard work, simplicity, and the steady rhythm of the rural world around them.

Their neighbors, James and Dinah Betteridge, were also part of the tight-knit community that made Lockerley feel like home. The Betteridges, no doubt, were among the first to welcome Caroline and Henry into the village, sharing in the quiet joys and struggles of village life. In the warm embrace of this community, Caroline and Henry, with their infant daughter, were forging their path, a path that would be shaped by the love they had for one another and the hope they held for Elizabeth’s future.

As the census was taken the following day, it marked not just a moment of legal record-keeping but a snapshot of their lives, a family at the very beginning of their journey, surrounded by neighbors who would become like family, in a village where the bonds of community were as strong as the timber Henry worked with every day.

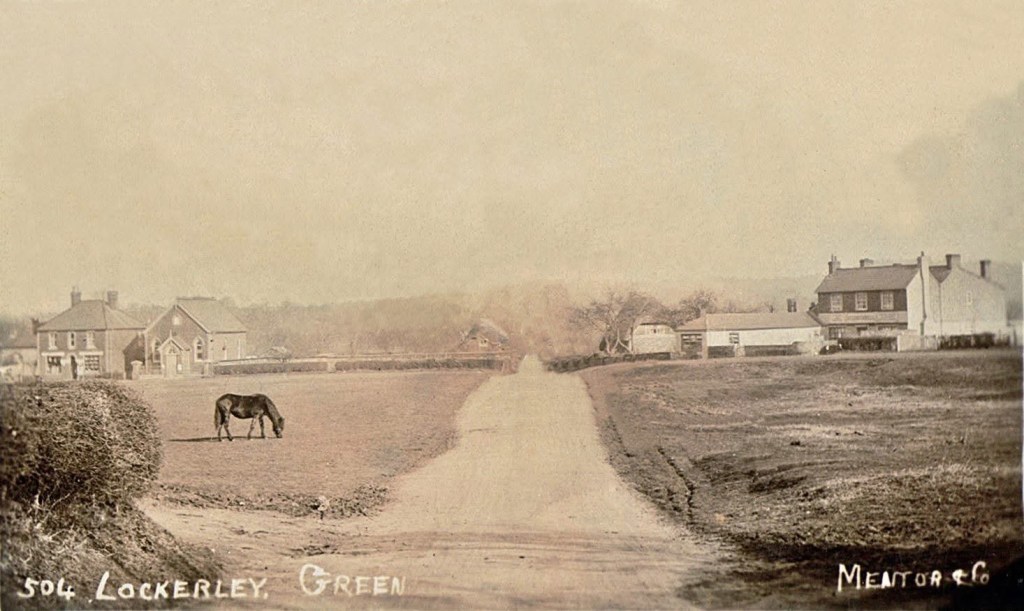

Lockerley Green is a picturesque area located in the village of Lockerley, Hampshire, nestled within the scenic Test Valley region. The village of Lockerley has a long history, and Lockerley Green, with its tranquil rural setting, serves as a central and defining feature of the village. The Green is a small, open area surrounded by a mixture of residential homes and farmland, giving it a peaceful, village-like atmosphere.

The history of Lockerley Green is closely intertwined with the development of the village itself. Lockerley has been inhabited for centuries, with evidence of settlement going back to the medieval period. The village grew up around its agricultural roots, and like many rural English villages, the Green likely served as a central meeting point for the local community. In the past, village greens were often used for a variety of communal activities, including grazing livestock, hosting markets, and holding festivals or fairs. Though the exact historical uses of Lockerley Green are not well-documented, it likely served these communal functions as part of village life.

During the 19th century, as rural communities began to shift with the rise of industrialization and the expansion of the British rail network, Lockerley remained a largely agricultural community. The Green, being centrally located within the village, would have been an area where locals gathered for social and religious events. Lockerley’s status as a small, rural village meant that changes came slowly, and the Green continued to serve as a quiet, open space for its residents.

The surrounding landscape of Lockerley Green is characterized by its rural charm, with rolling hills, fields, and woodlands that form part of the picturesque landscape of the Test Valley. The Green itself is typically bordered by traditional cottages, farms, and the occasional more modern development, but much of the original rural character has been maintained. The area is known for its natural beauty, attracting visitors and local residents alike who enjoy walking, cycling, or simply appreciating the tranquility of the countryside.

The Green has become an important symbol of the village’s character, representing the peaceful and close-knit community that defines Lockerley. While it may not have the same level of historical monuments or landmarks as larger towns or cities, Lockerley Green plays a key role in the village's everyday life. It serves as a focal point for various local events, such as community gatherings, village fêtes, and annual celebrations. These events help strengthen the sense of community and allow residents to come together in this historic part of the village.

Though Lockerley itself does not have a wealth of famous historical buildings or events, it is steeped in the charm of rural England. The village has retained much of its agricultural character, and the Green stands as a reminder of the enduring rural traditions that have shaped the area. The Green is also part of the larger landscape of Hampshire, which is renowned for its beauty and historical depth, making Lockerley a quintessential example of rural English life.

On Sunday, the 13th day of April, 1851, Caroline and Henry Carr’s daughter, Elizabeth, was baptized at St. John’s Church in Lockerley, Hampshire. This sacred moment, held in the peaceful surroundings of the church, marked another important milestone in Elizabeth’s young life. The ceremony was conducted by S. Austen, who, with care and reverence, performed the baptism that would formally welcome Elizabeth into the Christian community.

The baptismal register records this occasion with simplicity but profound significance, "On the 13th of April 1851, at St. John’s Church, Lockerley, Hampshire, England, Elizabeth, the daughter of Henry Carr, a sawyer, and Caroline Carr, of Lockerley, was baptized." Elizabeth’s baptism was logged as number 574, a testament to the many families who, like the Carrs, marked their children’s lives with this sacred tradition.

For Caroline and Henry, this moment would have been filled with hope for their daughter’s future, as well as a sense of connection to their faith and community. The baptism not only celebrated the arrival of their daughter into the Christian faith but also solidified her place within the legacy of their family. It was a quiet but lasting symbol of the love they held for Elizabeth and the community’s embrace of her into its fold.

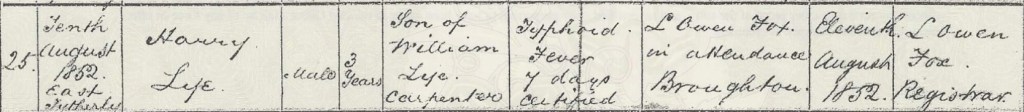

On Tuesday, the 10th day of August, 1852, Caroline's world was forever changed by the loss of her precious younger brother, Harry Lye. Just three years old, Harry had fought a brave battle against Typhoid Fever for seven agonizing days. For Caroline, the joy of childhood that she had once shared with him was now drowned in sorrow. The laughter that had once filled their home was replaced by the haunting silence of his absence, a silence that echoed through the very heart of their family.

L. Owen Fox, the registrar from Broughton, had been by Harry’s side in his final moments. He was not just an official but a quiet witness to the passing of a child, and his presence at the bedside made the loss all the more personal. The following day, Wednesday, the 11th of August, 1852, L. Owen Fox, meticulously recorded the tragic event in the death register: "Harry Lye, 3-year-old son of William Lye, a carpenter, died after seven days of being gravely ill with Typhoid Fever and died from the disease on the 10th of August, 1852, in East Tytherley." The registrar’s words, though official and necessary, seemed so distant compared to the raw emotion that Caroline and her family must have felt in that moment.

For Caroline, losing Harry was not just the death of a sibling, it was the loss of the warmth and joy he brought to their family. It was the absence of his smile, the quietness of his once-giddy voice, and the pain of knowing he would never again call her name. In the days that followed, the house in East Tytherley would have felt empty, as though the very air had changed. The grief was overwhelming, but it was also one of those quiet, unspoken sorrows that is carried for a lifetime. She would have found herself looking at the door, half-expecting him to run in with his bright eyes and laughter, but the silence would return, reminding her of the little brother she had lost.

The presence of the registrar by Harry's bedside must have added an extra layer of sadness. His role, while necessary, would have been a poignant reminder of how quickly life could be taken, of how death could strike so suddenly and so ruthlessly. Caroline would remember those final moments with her brother, and though time would pass, the memory of losing him at such a tender age would remain woven into the fabric of her life, a loss that never fully healed, but stayed with her as a quiet, tender ache in her heart.

I’ve never come across a certificate indicating that the registrar was present at the time of death. Could he have been a friend of the family? Or possibly a relative? Perhaps it had something to do with Typhoid Fever, or maybe I’ll never know for certain.

What I understand, though, is that it was very uncommon for a registrar to be present at the time of death. In fact, registrars typically did not witness the death itself. Their role was to officially record the death after being informed by a family member, friend, or someone close to the deceased.

When a death occurred, it was usually a relative or a neighbor who would register it with the local registrar. In rural areas, where medical professionals were few and far between, it was often a close family friend or a neighbor who took on the responsibility of registering the death. The registrar would then log the details, including the cause of death, which was provided by the family or, in some cases, by a doctor if one had been consulted.

Nursing a child stricken with Typhoid Fever in 1852 was an agonizing experience for any mother, and for Caroline’s mother, Ann, it must have been especially harrowing as she watched her young son, Harry, fade away. At just three years old, Harry’s fight with the disease would have been a heartbreaking ordeal. Ann, with no real understanding of the disease's severity beyond its devastating symptoms, would have done her best to comfort him in any way she could.

Typhoid Fever in the mid-19th century was a cruel disease. The symptoms, high fever, abdominal pain, weakness, and the unmistakable rose-colored rash, would have been alarming, but there was little Ann could do other than offer cold compresses, keep Harry hydrated, and hope against hope for his recovery. The lack of effective treatments meant that Ann’s role was not one of healing, but of offering whatever comfort she could as her son slipped further into illness.

Although Caroline may not have been the primary caregiver due to her own responsibilities, it is certain that she would have been there for her mother. The emotional toll on Ann, watching her child suffer and knowing that there was little she could do to help him, would have been overwhelming. Caroline, still young herself, would have provided comfort to Ann, offering her strength and emotional support as they both waited in helplessness and dread. Caroline's presence would have been a small solace, a quiet support as they both faced the brutal reality that Typhoid Fever, a disease they barely understood, was taking Harry's life.

In their home, visits would have been restricted, not just for the family’s protection, but also to prevent the spread of Typhoid Fever, which was highly contagious. The isolation would have been difficult, but necessary. There were no guidelines or medical advice to follow beyond the instinct to keep others away from the sickroom and to take basic precautions, perhaps washing hands, trying to keep the space clean, and keeping Harry as comfortable as possible. But the cold, hard truth was that even these measures were insufficient to stop the disease from ravaging Harry’s small body.

Ann’s every moment would have been filled with fear, concern, and exhaustion as she watched her son’s condition worsen. As his mother, she would have felt both the physical weight of caring for him and the emotional toll of helplessness. Caroline, in her own way, would have felt the burden of her brother’s illness and their mother's distress. She may not have been able to intervene in the way she so desperately wished, but she would have done her best to offer the kind of comfort and companionship that only a daughter could provide during such an agonizing time.

By the time Harry passed away, Ann would have been left not only with the pain of losing a child but with the memory of those heartbreaking days spent caring for him, knowing that there was little anyone could do to save him. It was a loss that would reverberate through the family, leaving an indelible mark on both Ann and Caroline. For both mother and daughter, it would be a grief that could never truly be healed, but instead would be carried with them quietly and deeply, as they both moved through life with the shadow of Harry’s death lingering in their hearts.

Typhus fever is a group of infectious diseases caused by bacteria of the genus *Rickettsia*. The disease is typically transmitted to humans through the bite of an infected arthropod, such as lice, fleas, or ticks. There are several types of typhus, with the two most well-known being epidemic typhus (often called louse-borne typhus) and endemic or murine typhus (transmitted by fleas). While typhus is now less common in developed countries due to improved living conditions and modern medicine, it has historically been a significant cause of mortality and illness, particularly in crowded or unsanitary conditions.

The history of typhus fever spans centuries, with the disease causing widespread outbreaks, particularly during times of war, famine, and social upheaval. Epidemic typhus, in particular, has been linked to times of social collapse and poor hygiene, as it is transmitted by body lice, which thrive in crowded, unhygienic conditions. It was often associated with large populations living in close quarters, such as in military camps, refugee populations, or places affected by famine and war. Typhus outbreaks were especially common in Europe during the 17th and 18th centuries and continued into the 19th and early 20th centuries.

Epidemic typhus was particularly devastating during the Napoleonic Wars and World War I, where soldiers, refugees, and civilians lived in overcrowded conditions that promoted the spread of lice, which acted as vectors for the disease. During these outbreaks, typhus fever could kill a significant portion of the affected population. One of the most notable events in the history of typhus fever was the devastating outbreak among Russian soldiers and civilians during the Russian Revolution and the subsequent Russian Civil War in the early 20th century. Typhus also played a significant role in the suffering of populations during World War II, particularly in concentration camps, where unsanitary conditions contributed to the rapid spread of the disease.

The symptoms of typhus fever vary depending on the type, but they generally include high fever, chills, headache, muscle aches, and a rash. In epidemic typhus, the rash typically starts on the trunk and spreads outward. In severe cases, patients may experience confusion, delirium, and organ failure, which can lead to death if not treated promptly. The incubation period for typhus fever usually lasts from 7 to 14 days after infection, depending on the species of *Rickettsia* causing the illness.

Treatment for typhus fever has greatly improved since the discovery of antibiotics. Before the advent of antibiotics, there were no effective treatments for typhus, and the disease was often fatal, especially in severe cases. In the 20th century, the development of antibiotics like chloramphenicol, tetracycline, and doxycycline made it possible to treat and cure typhus infections. Modern antibiotics are highly effective when given early in the course of the illness, dramatically reducing the risk of complications and death. This has made typhus much less of a public health concern in most parts of the world today, though outbreaks still occur in regions with inadequate sanitation and healthcare infrastructure.

In addition to antibiotics, efforts to control typhus outbreaks have focused on controlling the insect vectors that spread the disease. Improving hygiene, reducing the population of lice, fleas, and ticks, and enhancing public health infrastructure have been key in reducing the transmission of typhus in many areas. These preventive measures have been particularly important in combating endemic typhus, which remains more common in certain regions, especially where rats, fleas, and poor living conditions contribute to its spread.

The development of the first vaccine for typhus came in the 20th century. Typhus vaccines, though not widely used in general populations, have been important for military personnel, workers in high-risk areas, and those in humanitarian crises. These vaccines help provide immunity in environments where typhus is likely to spread, such as in refugee camps, areas affected by natural disasters, or during wartime.

Typhus fever's historical significance cannot be overstated. In earlier centuries, it was one of the leading causes of death, particularly in conditions where people lived in overcrowded and unsanitary environments. Major outbreaks, especially during times of war and famine, had devastating effects on civilian populations and military personnel alike. Typhus became a symbol of the profound impact that unsanitary living conditions could have on human health. It also highlighted the critical importance of controlling insect vectors, improving sanitation, and developing effective treatments.

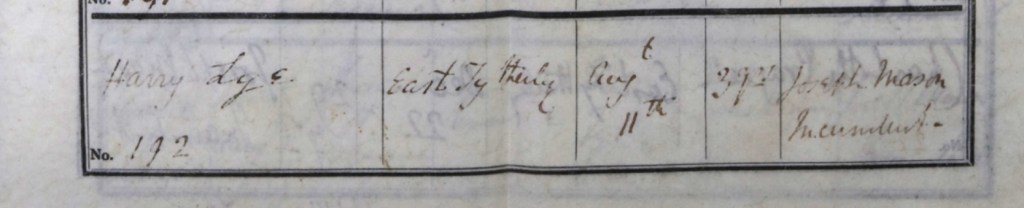

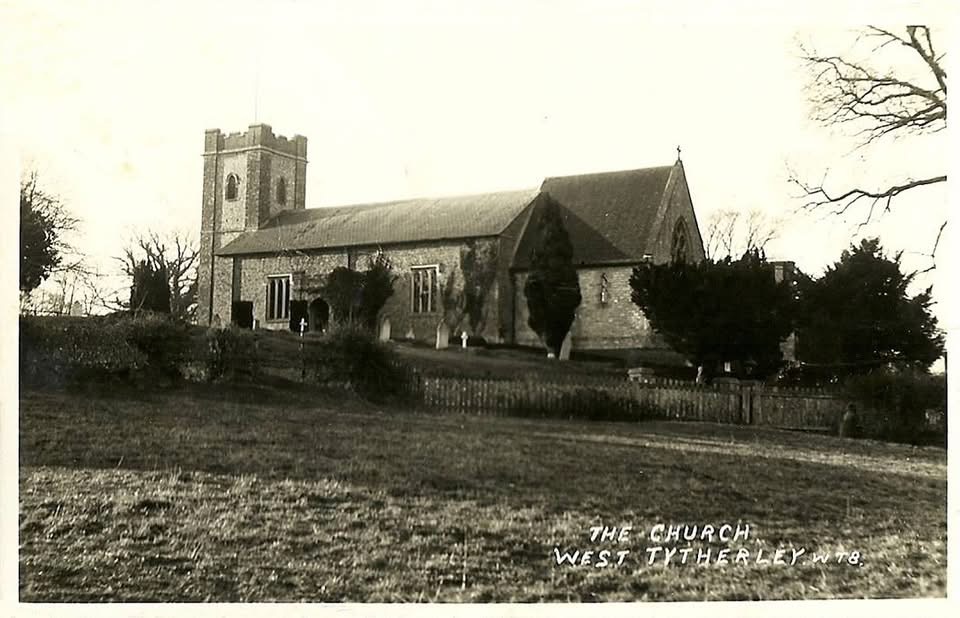

On Wednesday, the 11th day of August, 1852, Caroline’s young brother, Harry Lye, was laid to rest in the peaceful grounds of St. Peter’s Churchyard, East Tytherley, Hampshire. At just three and three-quarters years old, Harry’s life was tragically cut short by the cruel hand of Typhoid Fever, leaving a profound sorrow in the hearts of his family.

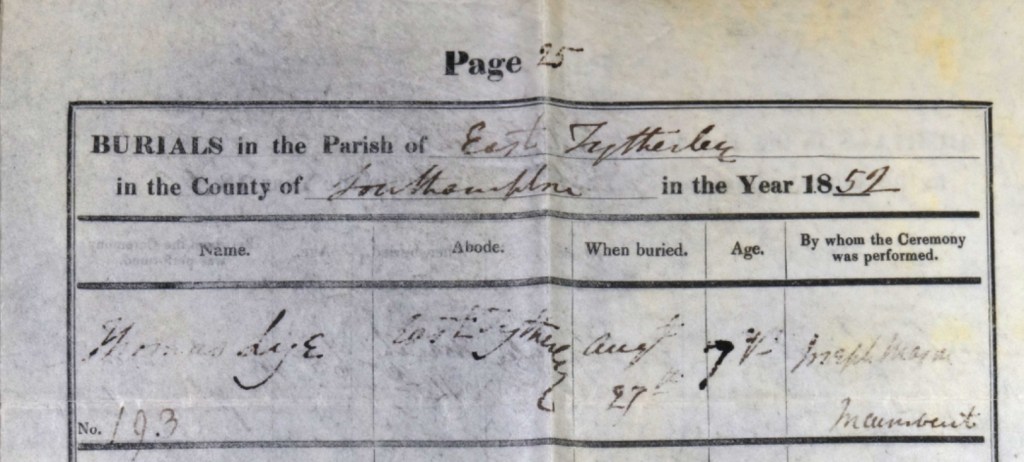

The burial, performed by Incumbent Joseph Mason, was a somber occasion. The parish churchyard, surrounded by the quiet countryside, became the final resting place for a child whose life had been full of promise but was taken too soon. Joseph Mason logged the details of Harry’s burial in the register, recording, “3 and 3/4-year-old Harry Lye of East Tytherley was buried on August 11th, 1852, in the parish of East Tytherley in the county of Southampton.”

This moment in the life of Caroline and her family marked the end of Harry’s brief but loved existence. The pain of burying a child so young was beyond measure, and the echo of his absence would resonate throughout their lives, as they carried his memory with them always. The quiet churchyard of St. Peter’s became the place where Harry’s spirit would rest, forever tied to the family and the village he had known, even if only for a short time.

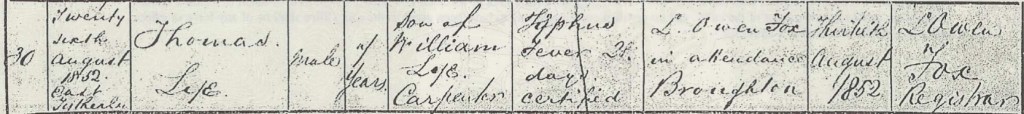

Just days after the loss of her brother Harry, Caroline’s heart was shattered once again. On Thursday, the 26th day of August, 1852, her 7-year-old brother, Thomas Lye, passed away in East Tytherley after battling Typhus Fever for 28 agonizing days. The house that had already felt the weight of grief from Harry's death was now filled with an even deeper sorrow. Thomas, full of youthful promise, was taken by the same cruel fate that had claimed Harry, and the family’s sense of loss grew even more unbearable.

L. Owen Fox, the registrar from Broughton, was once again there, in the quiet moments of Thomas’s final days, witnessing the agony of a mother losing another child to the grip of disease. On the 30th day of August, 1852, just days after Thomas’s passing, Registrar Fox registered his death, recording the grim details with somber precision. He wrote, “7-year-old Thomas Lye, son of William Lye, a carpenter, died after 28 days of being gravely ill with Typhus Fever on 26th August 1852 in East Tytherley. His death was certified.”

For Caroline, this loss of Thomas, following so closely on the heels of Harry’s death, must have felt like an unimaginable weight. To lose not one, but two young siblings in the span of just a few weeks was a grief that could scarcely be understood. The register, with its stark and formal words, could never capture the depth of Caroline’s sorrow, nor the anguish felt by the Lye family. They had already been shattered by the loss of Harry, and now, with Thomas gone, the family was left in a sea of heartache, struggling to come to terms with the cruel, untimely deaths of two beloved children.

Caroline would have felt the loss of Thomas as deeply as she had Harry, the two young brothers now forever absent from her life. The pain of burying a child, a sibling, was an ache that would never fade. And in the coming days, as the family laid Thomas to rest, their hearts would be forever marked by the devastating toll that disease had taken on their family, leaving behind only memories and the grief of what could have been.

The heartbreak for Caroline and her family deepened even further when, on Friday the 27th day of August, 1852, just 16 days after the burial of her younger brother Harry, they laid to rest Thomas Lye, aged just 7. The loss of two young children within such a short span of time was a sorrow that would have seemed too much for any mother or father to bear. Their home in East Tytherley, already heavy with grief, would have felt even emptier with Thomas's passing.

Incumbent Joseph Mason of St. Peter's Church in East Tytherley performed the burial and service, guiding the family through this painful moment. In the burial register, Mason recorded the details with the same formality as he had for Harry, “Thomas Lye, of East Tytherley, the son of William Lye, a carpenter, was buried on the 27th August 1852, in the parish of East Tytherley in the county of Southampton.” These words, though official and necessary, seemed hollow in comparison to the devastation that Caroline and her family must have felt as they laid their beloved Thomas to rest in the quiet churchyard.

The grief of losing two children so young, so close together, was unimaginable. Caroline, still a young woman, had to witness the loss of both her brothers, leaving her with a sense of incomprehensible sorrow. The quiet churchyard, where Thomas was buried, became a final resting place for a child whose future was stolen too soon, and for a family that would never fully recover from such heartache. Their grief was marked not just in the burial registers, but in the silence that followed, a silence that would linger with them forever.

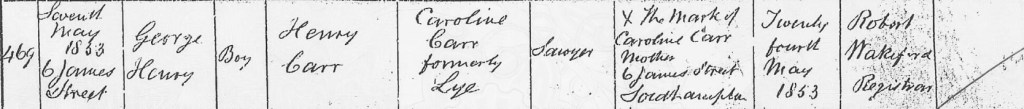

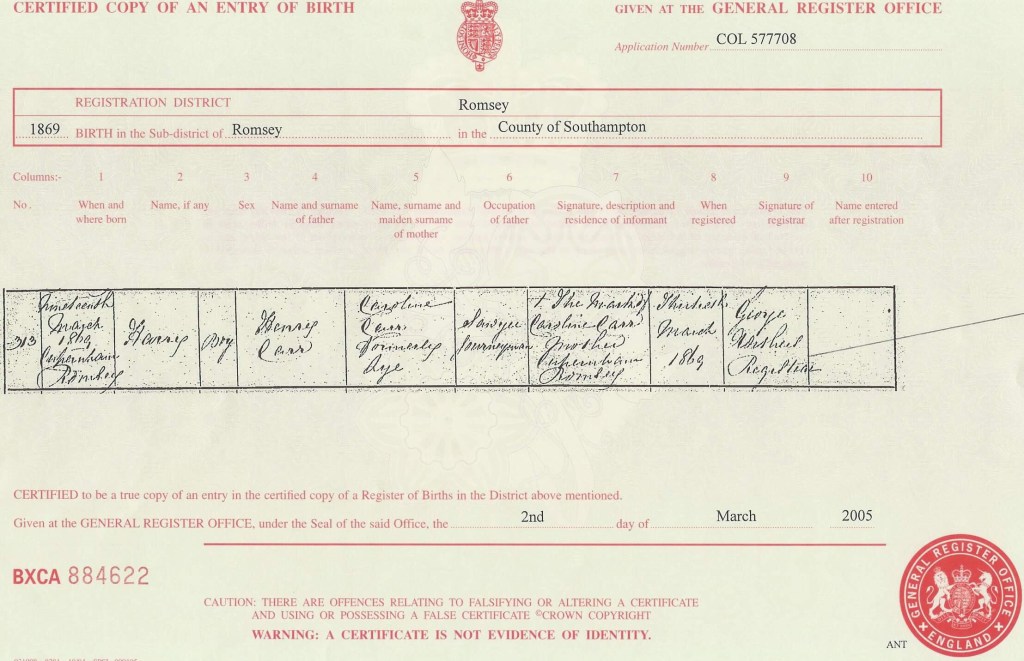

On Saturday, the 7th day of May, 1853, Caroline and Henry Carr welcomed their son, George Henry Carr, into the world. The birth took place at Number 6, James Street, in the bustling town of Southampton, Hampshire, a moment of joy amidst the trials and heartache that had defined their lives in the years prior. For Caroline, the arrival of George was a light in the darkness, a new beginning after the losses she had suffered, and a symbol of hope for the future.

Caroline, as was customary, registered George’s birth on Tuesday the 24th day of May, 1853. The official record was logged by Registrar Robert Wakeford, who noted the details of the birth with care. In the birth register, it was recorded, “On the 7th of May 1853, at 6, James Street, George Henry Carr, a boy, was born to Henry Carr, a sawyer, and Caroline Carr, formerly Lye, of 6, James Street, Southampton.”

Caroline, as was often the case for women of her time, signed the official document with her mark, an “X,” a poignant reminder of the limitations of formal education for many in rural and working-class families. Though she may not have been able to write her name, her love for George and her strength as a mother were beyond measure.

For Caroline and Henry, George’s birth was more than just the arrival of a new child, it was a moment of joy that balanced the deep sorrow they had known. It was a chance for them to rebuild, to create new memories, and to hold in their arms the future they had worked so hard to protect. As the years passed, George would carry their hopes and dreams forward, a living testament to the strength and love that Caroline had always shown, despite the trials that life had placed before her.

James Street in Southampton, Hampshire, is a thoroughfare with a rich history, reflecting the city's evolution from medieval times to the present day. Located in the St Mary's area, the street has witnessed significant developments over the centuries.

Historically, Southampton was a bustling port town, and James Street was likely part of the urban fabric that supported maritime trade and the city's growth. In the 19th century, the area underwent industrialization, with the establishment of various businesses and residential developments. Notably, the building firm Joseph Bull and Sons, established in 1832, had a presence on James Street, contributing to the construction boom during that era.

In the mid-20th century, James Street became a focal point for community activities. For instance, a street party was held on June 2, 1953, to celebrate Queen Elizabeth II's coronation, highlighting the area's vibrant community spirit.

Architecturally, James Street features a mix of residential and commercial buildings, with many properties dating back to the mid-20th century. The area predominantly comprises flats, with a significant proportion being social housing. The housing stock includes mid-century flats built between 1936 and 1979, reflecting the post-war development of the city.

Regarding myths and hauntings, there are no widely documented paranormal activities associated with James Street. While many historic areas have local legends or ghost stories, no specific tales of hauntings have been recorded for this particular street. The absence of such stories may be due to the street's relatively modern development and the continuity of its use as a residential and commercial area, which can sometimes deter the development of folklore and ghostly legends.

Today, James Street continues to serve as a vital part of Southampton's urban landscape, embodying the city's dynamic history and its ongoing transformation.

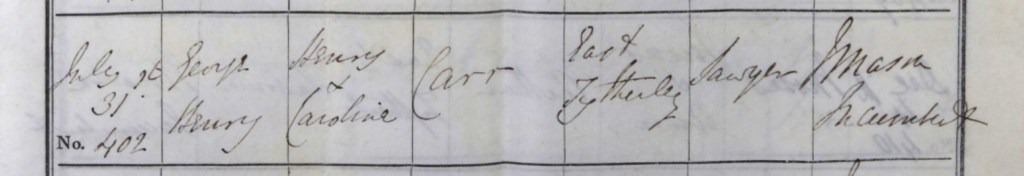

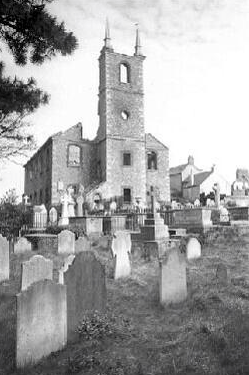

On a warm summer’s morning, Sunday the 31st day of July, 1853, Caroline and Henry Carr gathered at St. Peter’s Church in East Tytherley to baptise their son, George Henry Carr. The small, serene church, nestled in the heart of their beloved village, became the sacred place where George was formally welcomed into the Christian faith. The ceremony, carried out by Junior Curate J. Marsh, was a tender moment for the young family, marking a new chapter in their lives after the sorrow they had experienced in recent years.

The baptismal register, now a cherished record of their family’s history, captures the simplicity and significance of the event, “On the 31st of July 1853, at the parish church of East Tytherley, George Henry Carr, son of Henry Carr, a sawyer, and Caroline Carr, of East Tytherley, was baptised.”

For Caroline and Henry, this baptism was more than a religious rite; it was a moment of joy, a celebration of new life and the enduring strength of their family. After the painful losses they had endured, the baptism of their son was a chance to look toward the future, to build a new legacy, and to share their love and faith with the next generation. In the quiet warmth of the summer day, surrounded by the village community, George’s baptism was a symbol of hope, of faith renewed, and of the love that Caroline and Henry would continue to pour into their growing family.

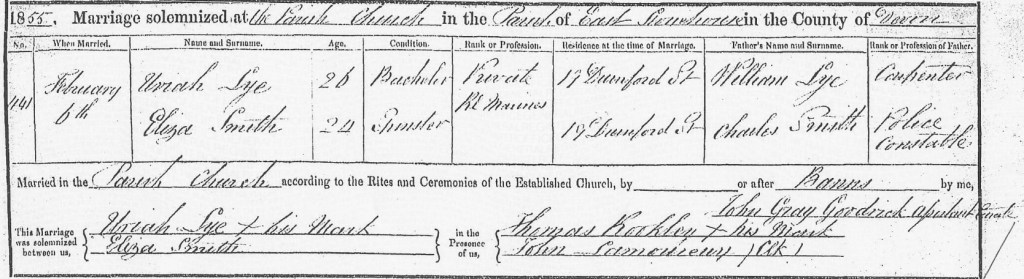

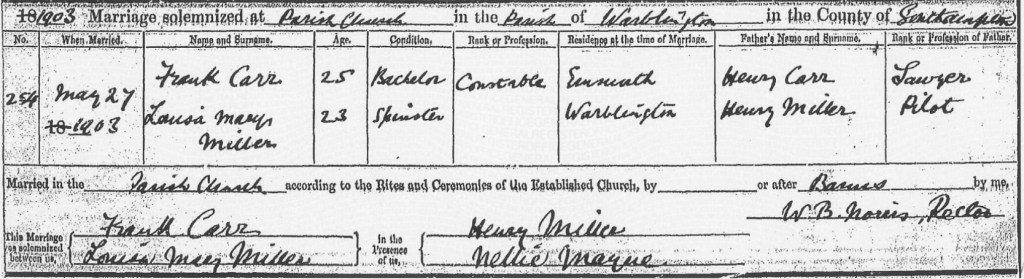

On Tuesday, the 6th day of February, 1855, Caroline’s brother, Uriah Lye, took a momentous step in his life as he married Eliza Smith at St. George’s Church in East Stonehouse, Devon. The ceremony was performed by John Gray Goodrick, who carefully recorded the union in the marriage register, marking the beginning of a new chapter for Uriah and Eliza.

The register entry reads, "On the 6th February 1855, at the parish church of East Stonehouse in the county of Devon, 26-year-old bachelor Uriah Lye, a private in the Royal Marines, of 19 Dunford Street, son of William Lye, a carpenter, married 24-year-old spinster Eliza Smith, of 19 Dunford Street, daughter of Charles Smith, a Police Constable." Their witnesses were Thomas Rookley and John (surname unclear), and both Uriah and Thomas signed the document with their marks, an "X," a quiet reflection of their lack of formal education in a time when literacy was not universal.

For Caroline, the marriage of her brother Uriah was not just a family event, it was a reminder of how life moves forward, of how her siblings were building their own futures, and of the changes that were gradually unfolding within the family. Uriah’s marriage to Eliza, set against the backdrop of military life, symbolized both a personal commitment and a new chapter of responsibility. And as the couple started their life together, the bond between family members only grew, with each event in their lives, like this one, woven into the broader tapestry of the Lye family’s shared history.

St. George's Church, located in East Stonehouse, Devon, is a significant and historic place of worship in the region. The church has played an important role in the religious and social life of the community for centuries, serving as a spiritual center for the people of East Stonehouse and the surrounding areas. Situated in the heart of East Stonehouse, which is now part of Plymouth, the church is an enduring landmark that reflects the area's historical development.

The history of St. George’s Church dates back to the 18th century, with the church being built in the early 1700s to serve the growing population of East Stonehouse. At the time, East Stonehouse was expanding as a result of the development of the naval base in Plymouth, which brought both military personnel and civilians to the area. The construction of St. George’s Church was part of this broader expansion of infrastructure to meet the needs of the growing population.

The church itself was designed in the classical style, which was popular during the 18th century. The building’s architecture reflects the design trends of the period, with clean lines, a simple yet elegant exterior, and a well-proportioned structure. Over time, the church underwent several changes and improvements, with additions made to accommodate the growing congregation and to update the building's design as architectural tastes evolved.

One of the key historical events in the life of St. George’s Church was its role in serving the spiritual needs of the local community during times of conflict. As the area was closely linked to the naval activities of Plymouth, St. George’s Church was a place where sailors, military personnel, and their families gathered for worship. The church also played an important role in the local community, hosting various ceremonies, including weddings, christenings, and funerals. Many of the sailors and military personnel who passed through East Stonehouse would have worshipped in the church, marking significant moments in their lives before embarking on voyages or serving overseas.

St. George’s Church also played a role in the social history of the area. Over the centuries, it became a focal point for community gatherings, offering a space for local events, socializing, and support. The church's close association with the Royal Navy, given its location in East Stonehouse, contributed to its importance as a communal hub during both peacetime and conflict.

In addition to its role as a place of worship and community gathering, St. George’s Church has been involved in significant historical events over the years. The church, like many in the region, witnessed the challenges of World War II. During the war, Plymouth, including East Stonehouse, was heavily bombed due to its strategic location near naval installations. St. George’s Church, though damaged during the bombing raids, survived the war and continued to serve the community in the post-war years.

The church has also been a place of reflection and remembrance, particularly for the military and naval personnel who lived and worked in East Stonehouse. Over the years, St. George's has been a site for memorials and commemorations of those who lost their lives in service to the country. These memorials often include plaques, stained-glass windows, and inscriptions that honor those who served in the Royal Navy and the armed forces.

Architecturally, St. George’s Church is known for its simple yet striking design. It features a classic rectangular shape, a tall spire, and large windows that allow natural light to flood the interior. The church’s interior is equally elegant, with pews arranged around a central altar, and a well-crafted organ that has provided music for countless services over the years. The building has been well-maintained, with ongoing restoration efforts ensuring its preservation as a historical and architectural treasure.

Over the years, the area surrounding St. George's Church has evolved significantly. East Stonehouse, once a bustling district in its own right, became part of the larger city of Plymouth in 1914. As Plymouth expanded and modernized, the church remained an important focal point in the community. Today, it continues to serve as an active parish church, providing a place for regular services, weddings, baptisms, and funerals. It also hosts various community events, bringing people together for both religious and social occasions.

In terms of rumors of hauntings or paranormal activity, St. George's Church, like many old buildings with a long history, has been the subject of occasional ghost stories and local legends. Some visitors and residents have reported feelings of unease or strange occurrences within the church or its grounds, which is common in buildings with centuries of history. However, there are no widely known or substantiated accounts of hauntings at St. George’s Church. The church, with its rich history and connection to the community, remains a place of reverence and peace.

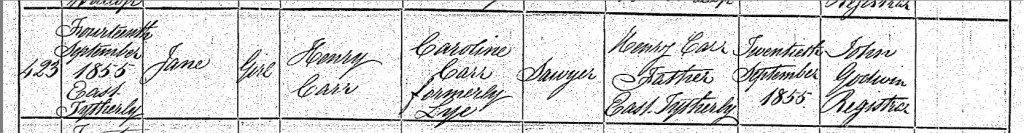

On the 14th day of September, 1855, a new life filled the home of Caroline and Henry Carr, bringing with it the softest joy and the sweetest promise of the future. Their daughter, Jane Carr, was born in the peaceful village of East Tytherley, Hampshire, a little girl who would forever change the rhythm of their lives. For Caroline, this moment was both a quiet and profound milestone, a breath of new hope in the ever-evolving journey of motherhood. With each birth, her heart expanded, and the love she held for her growing family blossomed even more deeply.

In the days that followed, on Thursday, the 20th day of September, 1855, Henry, ever devoted to his family, registered Jane’s birth. The birth was logged by Registrar John Godwin, who carefully recorded the event in the official register, ensuring Jane’s arrival was preserved in time, “On the 14th of September 1855, at East Tytherley, Jane Carr, a girl, was born to Henry Carr, a sawyer, and Caroline Carr, formerly Lye, of East Tytherley.” The simple elegance of the words may seem understated, but for Caroline, they held the weight of her deepest love for her daughter, a love that would grow with each passing day.

Caroline’s role as a mother was ever-changing, ever-deepening, as she embraced each new chapter in her family’s story. Jane’s arrival was not just the birth of a daughter; it was the continuation of Caroline’s story, the echo of her own childhood now mirrored in the soft laughter and bright eyes of her little girl. The world felt anew with Jane in it, and for Caroline, there was an undeniable sense of the power of love, the kind of love that nurtures, that binds, and that makes life worth every sacrifice. Each day with Jane, each moment of motherhood, was a testament to the strength of her heart.

As the years unfolded, Caroline’s life, once shaped by the trials of her past, began to take new form in the tenderness of these quieter moments. The love of her family, her children, and her steadfast husband, Henry, became the cornerstone of her world. Through the pages of the registers and the milestones recorded in ink, Caroline's story continued to blossom in ways that were as ordinary as they were extraordinary. And though life often pressed its burdens upon her, it was these moments, these tender chapters, that would carry her through to the next page of her life’s unfolding.

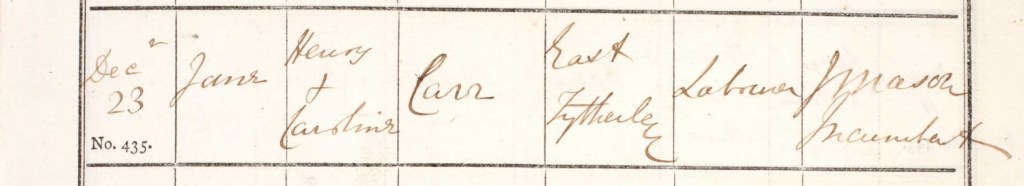

On the Sunday, the 23rd day of December, 1855, under the soft glow of winter’s light, Caroline and Henry Carr brought their precious daughter, Jane, to St. Peter’s Church in East Tytherley, where the quiet ritual of baptism would bind her to her faith, her family, and her community. The crisp air outside contrasted with the warmth of the church, where Jane’s delicate spirit was welcomed with love and reverence.

Incumbent Joseph Mason, with steady hands and a heart full of compassion, performed the baptism, carefully marking this sacred moment in the church’s register. The entry, though simple, carries with it the depth of Caroline’s love for her daughter, and the hope she held for Jane’s future, “On Sunday 23rd December 1855, at the Parish church of East Tytherley, Jane Carr, daughter of Henry Carr, a labourer, and Caroline Carr, of East Tytherley, was baptised.”

For Caroline, this was more than just a religious ritual; it was a promise. A promise to her daughter, to raise her with the same strength, love, and grace that had been passed down to Caroline from her own mother. It was a moment to reflect on the family’s bond, and to acknowledge the beauty of bringing new life into the world, a life that would, in time, create its own ripples in the river of history. As Jane was baptized, surrounded by the warmth of the church and the love of her parents, Caroline knew that this day would be a milestone forever etched in her heart. In the quiet embrace of faith, there was a sense of peace, and for Caroline, it was the moment she began to see the future she had dreamed for her family unfolding before her.

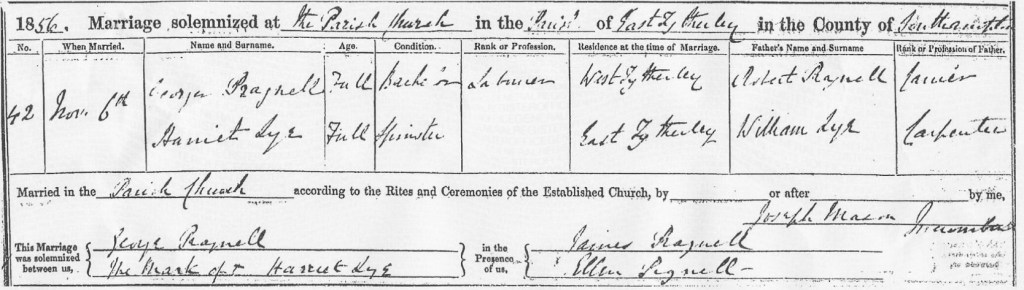

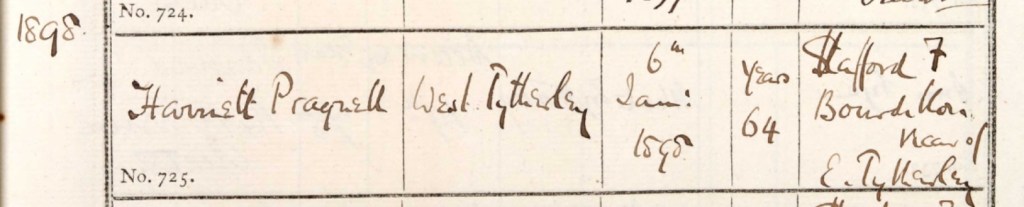

On Thursday, the 6th day of November, 1856, Caroline’s sister, Harriet Adelaide Lye, stepped into a new chapter of her life, one filled with hope and the promise of a shared future, as she married George Pragnell at St. Peter’s Church in East Tytherley. The day, likely crisp with the freshness of autumn, was marked by the gentle sounds of the church, where the ceremony was performed by Minister Joseph Mason. The church, a place that had witnessed the significant moments of the Lye family’s history, now stood as the backdrop for Harriet’s wedding, where she would join hands with George to begin their life together.

In the marriage register, Joseph Mason carefully documented the event, recording, “On the 6th November 1856, at the parish church of East Tytherley, in the county of Southampton, Spinster Harriet Lye, of East Tytherley, daughter of William Lye, a carpenter, married bachelor George Pregnell, a labourer of West Tytherley, the son of Robert Pregnell, a joiner.” Their witnesses, James and Ellen Pregnell, stood by their side, sharing in the joy of this union that would intertwine the Lye and Pregnell families. Harriet, like so many before her, signed the official document with her mark, an “X,” a quiet symbol of her strength and her place in a world where formal education and literacy were not always a given.

For Caroline, this moment in her sister’s life would have been one of both joy and reflection. Harriet, having grown up alongside Caroline in the small but rich community of East Tytherley, was now beginning a life of her own. It was a beautiful moment of change and growth, a moment filled with both excitement and the promise of all the adventures yet to come. As the Lye family witnessed the union of Harriet and George, it was a reminder of the passage of time, the shifting of roles, and the deep, unbroken bonds that held their lives together. In that church, on that autumn day, a new chapter began for Harriet, and her family shared in that new beginning with her, knowing that it would shape their future in ways they could only begin to understand.

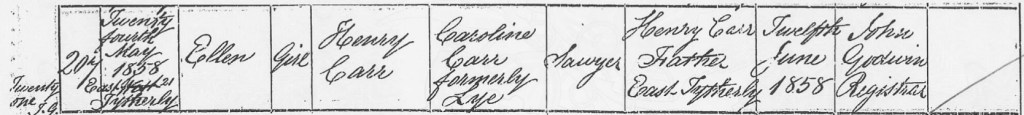

On Monday, the 24th day of May, 1858, Caroline and Henry Carr were blessed with the birth of their daughter, Ellen Carr, in the quiet village of East Tytherley, Hampshire. As the seasons shifted and the warmth of spring settled over the land, Ellen's arrival brought a fresh sense of joy and renewal to their home. For Caroline, this was another moment of quiet wonder, as she held her newborn daughter in her arms, knowing that this little one would soon become an irreplaceable part of their family.

Henry, ever devoted to his growing family, registered Ellen’s birth on Saturday, the 12th of June, 1858. The formal process took place in Stockbridge, where Registrar John Godwin recorded the event with care. The official entry in the birth register reads, “On Monday, 24th May 1858, at East Tytherley, Hampshire, England, Ellen Carr, a girl, was born to Henry Carr, a sawyer, and Caroline Carr, formerly Lye, of East Tytherley.”

As Caroline signed the document with her mark, an “X,” it was a quiet reflection of the many sacrifices and struggles of her life, yet it was also a symbol of her immense strength and the deep love she held for her children. Ellen's birth added yet another layer to Caroline's role as a mother, a role that she embraced fully despite the challenges and heartaches she had faced. Each new child was a new opportunity to share her love, her wisdom, and her dreams, and with Ellen, her heart swelled with the promise of what was to come.

Ellen’s arrival, so carefully recorded in the register, was more than just a legal document, it was the beginning of a new chapter in Caroline and Henry’s life, a chapter filled with the laughter of children, the quiet rhythm of family life, and the enduring love that bound them all together. In the simple act of bringing a new life into the world, Caroline once again found herself rooted in the legacy of her family, watching as the next generation began to weave its own story into the fabric of their history.

As the morning sun glistened over the rolling fields of East Tytherley, casting a golden glow on the quiet village, Caroline and Henry made their way to St. Peter’s Church, hearts full of love for their daughter, Ellen. On Sunday, the 8th day of August, 1858, they brought their little girl to the church, eager to mark her place in the faith and in the legacy of their family. The air was crisp with the beauty of summer, and the church, nestled among the gentle hills of Hampshire, stood as a witness to another significant moment in their lives.

Incumbent Joseph Mason, with a steady hand and a heart full of grace, performed the baptism, a sacred ritual that would bind Ellen to her family, her faith, and the village she would grow up in. The ceremony, though quiet and humble, carried with it the weight of generations of tradition, and for Caroline and Henry, it was a moment of deep connection to their roots, their love, and their future.

In the baptism register, Joseph Mason recorded the event with simplicity and reverence, “On the 8th August 1858, at the parish church of East Tytherley, Ellen Carr, daughter of Henry Carr, a sawyer, and Caroline Carr, of East Tytherley, was baptised.”

For Caroline, this baptism was a quiet promise, a promise to raise Ellen with the same love and care that had been passed down to her. It was a day that marked the beginning of Ellen’s journey in the world, a journey that would be shaped by the love of her family and the strength of the community around her. As Caroline and Henry stood together in that sacred place, they knew that their daughter’s life, like their own, would be woven into the rich fabric of East Tytherley, with love, faith, and family at its core.

The loss of Caroline's brother, Uriah Lye, in 1858, though shrouded in the mysteries of time and distance, must have been a profound moment of sorrow for her and her family. The details of his death in Australia remain elusive, but the pain of losing a sibling, especially one so far from home, would have left an indelible mark on Caroline's heart. Though Uriah had ventured across the world, likely seeking new opportunities or perhaps following a dream, his passing must have felt like a distant echo, a reminder of the family and the life he had left behind in East Tytherley.

For Caroline, this loss was different from others. It was not the loss of a sibling she could visit, nor one she could mourn with the same closeness as those who had passed in her own village. The distance between her and Uriah, both in miles and in the years since he had left, added an extra layer of sadness to his departure. But despite the separation, the bond between siblings never truly fades. Caroline would have held onto the memory of Uriah, with his place in her life now a part of her own personal history.

The gap in the records of Uriah's life is a reflection of the challenges that Caroline, and many like her, faced in an era where communication was slow, and distant losses often remained shrouded in uncertainty. Yet, in the quiet moments of her life, Caroline would have carried the memory of her brother with her, a figure whose presence in her past had shaped the woman she became. Even in the absence of details, Uriah’s legacy would live on in the stories shared by those who loved him, and in the space he once filled within Caroline's heart.

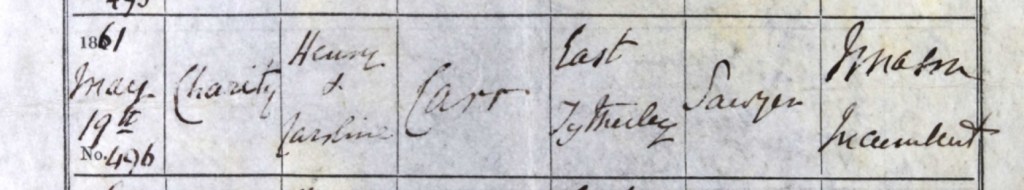

As a new year unfolded and the winter frost turned the fields of East Tytherley into a picturesque landscape, Caroline and Henry Carr welcomed their daughter, Charity Carr, into the world in East Tytherley, Hampshire, on Friday, the 25th day of January, 1861. In the quiet of their home, amidst the gentle winter chill, Charity’s arrival brought a new light into their lives, a fresh chapter in their family’s story. The birth of a child is always a moment of great significance, but for Caroline, Charity's birth was a new opportunity to nurture, to love, and to embrace motherhood once again.

Caroline, ever the devoted mother, registered Charity’s birth on Wednesday, the 27th day of February, 1861. The formalities were carried out by Deputy Registrar John Morgan, who diligently recorded the details of Charity’s birth in the official register. The entry reads simply, “On the 25th January 1861 at East Tytherley, Charity Carr, a girl, was born to Henry Carr, a sawyer, and Caroline Carr, formerly Lye, of East Tytherley.”

Caroline signed the official document with her mark, an "X," a quiet but powerful symbol of the many years of hard work, love, and sacrifice that had shaped her life. Though Caroline's education was not formal, her heart was rich with the love and care she gave to her family. In the early days of Charity’s life, Caroline would have given everything to ensure her daughter knew the warmth and love of a mother’s embrace.

Charity’s birth, recorded in the official pages of history, was a gift to her family, a new life to nurture, to guide, and to watch grow. For Caroline, the birth of Charity represented both the continuation of her family’s legacy and a symbol of hope for the future, a future that was filled with new opportunities, new joys, and new memories to create together. As her family continued to grow, Caroline’s love for each child would remain her guiding light, lighting the path ahead for Charity, just as it had for Caroline herself.

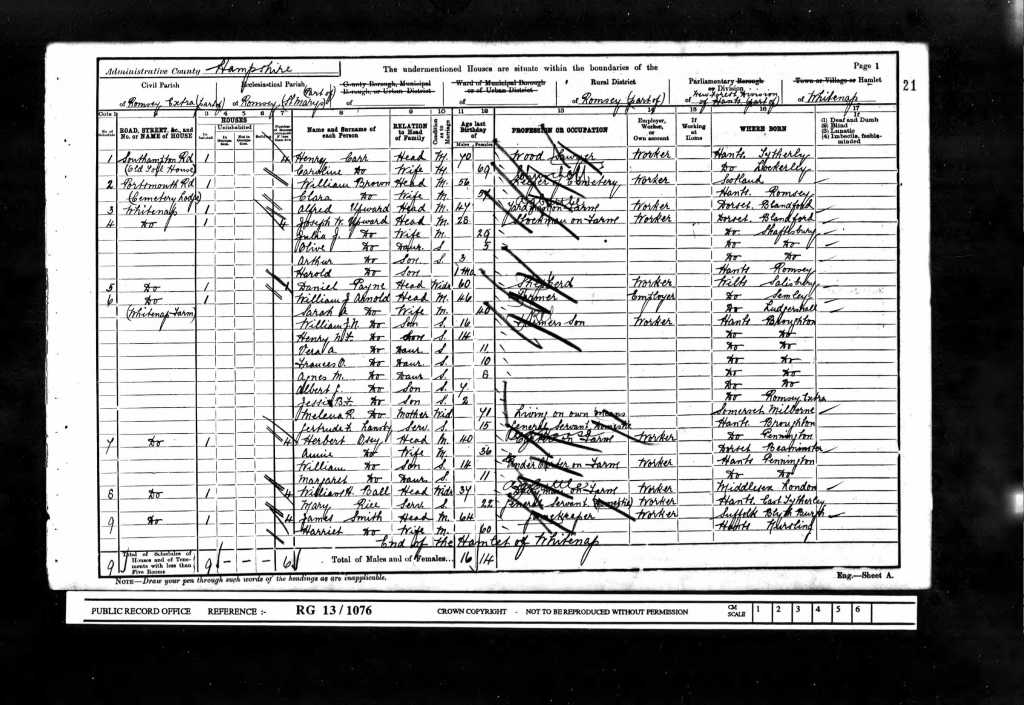

On the eve of the 1861 census, Sunday the 7th day of April, Caroline, now 30 years old, and her husband, 31-year-old Henry, were living in a home full of life and love at Number 7, Goldsmid Common, East Tytherley, Hampshire. Their children, Elizabeth, 10; George Henry, 8; Jane, 6; Ellen, 3; and the newborn Charity, just 1 month old, filled the house with the bustling energy of family life. The air of the home would have been filled with the sounds of laughter, the rhythms of daily life, and the quiet hum of motherhood as Caroline navigated her ever-growing family.

Next door, at Number 6, Henry’s parents, John and Elizabeth, were settled in their own home, accompanied by Henry’s brother, William, and his wife, Eliza, and their daughter, Nancy. The proximity of their families created a sense of togetherness and support, with the two households woven together by shared love, history, and work. Both Henry and William worked as sawyers of wood, continuing the family’s trade, while their father, John, had once worked as a sawyer as well, a legacy passed down through the generations.

In the surrounding neighborhood, the children, Elizabeth, George Henry, Jane, and Ellen, were scholars, likely attending the local school and learning the foundations that would carry them through life. It was a time of both hard work and hope, where each child had the potential to grow, to learn, and to contribute to their tight-knit community. Caroline’s role as a mother was one of nurturing, guiding her children as they learned and explored the world around them.

At Number 8, James Arthur, an agricultural laborer, and his family resided, marking the quiet yet vital diversity of the small community. These close-knit families, each with their own roles in the village, shared the same space and contributed to the fabric of East Tytherley, from the work in the fields to the lessons in the schoolroom.

Henry and his family occupied the entirety of Number 7, while his parents, John and Elizabeth, filled their home at Number 6. The close quarters of the two households served as a reminder of the importance of family in the 19th-century rural life, a place where every member of the family played an essential role, and where the bonds of love and support were felt in every shared meal, every hour of work, and every tender moment of care.

For Caroline, this snapshot of their lives, recorded in the census, reflected the beauty of her world, the simple joys and the steadfast love of family that would shape her children’s futures and provide the steady foundation for her own.

Goldsmid Common is a rural area located in East Tytherley, a small village in Hampshire, England, within the scenic Test Valley. The common is part of the larger rural landscape of the area, which is known for its natural beauty and tranquil atmosphere. East Tytherley itself is a modest, peaceful village that has retained much of its historic rural character, and Goldsmid Common is one of the areas that adds to its charm.

The history of Goldsmid Common is closely tied to the broader development of the region. East Tytherley, like many other rural villages in Hampshire, has roots going back to the medieval period. The village name itself suggests a Saxon origin, and it would have been a small agricultural community for much of its early history. Common land such as Goldsmid Common played an important role in rural village life, particularly during the medieval and early modern periods.

In the past, commons were areas of land that were shared by the local community for grazing livestock, gathering firewood, and other communal uses. They were often central to the social and economic life of rural villages. Goldsmid Common likely served such purposes historically, providing essential resources for the people of East Tytherley and the surrounding area. Commons were typically not enclosed and remained open for the use of local people, offering shared space for animals, crops, and leisure activities.

By the 19th century, with the rise of enclosures and changes in land use due to agricultural improvements, many common lands were gradually enclosed or repurposed. While the exact details of the enclosure of Goldsmid Common are not well documented, it is likely that, like many others, it saw changes as land use evolved in the area. The rise of industrial agriculture and changes in farming practices led to a shift in the way the land was utilized, and many commons began to shrink or become less accessible to the public.

Today, Goldsmid Common is a quiet, rural area that contributes to the peaceful, natural environment of East Tytherley. The common is an open space that is now used for local enjoyment, whether through walking, wildlife watching, or simply appreciating the beauty of the Hampshire countryside. The surrounding area remains largely agricultural, with rolling hills, woodlands, and fields contributing to the area's charm.

Goldsmid Common remains an important part of East Tytherley’s rural identity, offering residents and visitors alike a place to connect with nature. The common's continued existence as an open space speaks to the traditional rural values of the area, which have persisted even as the landscape has changed over time. While it may not have the same historical landmarks or major events as larger towns or cities, Goldsmid Common plays an important role in maintaining the village's connection to its agricultural roots and its rural heritage.

On the fresh spring morning of Sunday the 19th day of May, 1861, as the daffodils swayed gently in the morning breeze, Caroline and Henry made their way to St. Peter’s Church in East Tytherley with hearts full of love and anticipation. The air was crisp, and the beauty of the day mirrored the joy they felt as they brought their youngest daughter, Charity, to be baptised in the sacred waters of their village church. This was a moment that carried not just the weight of tradition, but also the hopes and dreams they held for their daughter’s future.

Incumbent Joseph Mason, a man of deep faith and experience, performed the baptism with reverence. Joseph Mason, known not only as the Vicar of East Tytherley but also as the former Chaplain to the Forces in the Crimea, stood before the family with a sense of solemnity and care. His presence, shaped by the weight of his own past, added an air of significance to the ceremony, as Caroline and Henry looked on, their hearts swelling with love for Charity.

In the baptism register, Joseph Mason recorded the simple yet profound details of the event, “On Sunday, 19th May 1861, at the Parish church of East Tytherley, Charity Carr, daughter of Henry Carr, a sawyer, and Caroline Carr, of East Tytherley, was baptised.”

For Caroline, this was a day of quiet joy, the promise of a bright future for her daughter sealed in the waters of faith. As she stood in that church, with the soft light streaming through the windows and the presence of her beloved community surrounding her, she knew that this moment would be one of the many that would shape Charity’s life. The baptism was more than a ceremony, it was a blessing, a moment of connection between past, present, and future, where love, faith, and family intertwined in the most beautiful of ways. And as the spring breeze whispered through the churchyard, Caroline could feel the warmth of her family’s love surrounding her, a love that would guide Charity’s journey in this world.

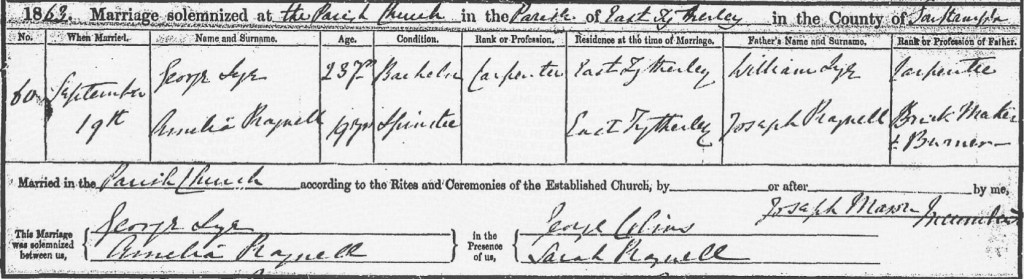

On a crisp autumn day, as the leaves dressed in shades of gold and amber, Caroline’s brother, George Lye, embarked on a new chapter of his life. On Saturday, the 19th day of September, 1863, he stood at the altar of St. Peter’s Church in East Tytherley, Hampshire, ready to marry his beloved Amelia Pregnell. The air was thick with the scent of the changing season, and the church, bathed in the warm glow of the autumn sunlight, became the backdrop for a union that would forever intertwine their futures.

The ceremony was performed by Minister Joseph Mason, whose steady presence guided the couple through this momentous occasion. His hands, as they recorded the details in the marriage register, ensured that this moment,marked by love, hope, and the promise of a shared life, would be preserved in history. The register entry reads simply, yet beautifully, “On the 19th September 1863, at the parish church of East Tytherley, in the county of Southampton, 23-year-old bachelor George Lye, a carpenter of East Tytherley, son of William Lye, a carpenter, married 19-year-old spinster, Amelia Pregnell of East Tytherley, the daughter of Joseph Pregnell, a brick maker and burner.”

Their witnesses, George Colin’s and Sarah Pregnell, stood by their side, bearing witness to a love that was strong and full of promise. As the couple exchanged vows, surrounded by the beauty of the autumn day and the warmth of their families, Caroline, no doubt, watched with a full heart, seeing her brother begin a new journey, much like the seasons changing around them. The day was a reflection of both the beauty and the simplicity of life, a reminder that love, no matter the season, is something that flourishes and grows. For George and Amelia, this marriage was not just a union of two hearts but the beginning of a shared future, a future that would forever be marked by the love and support of their families, and the roots of East Tytherley, which held them close.

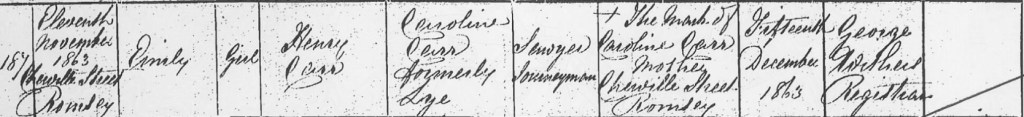

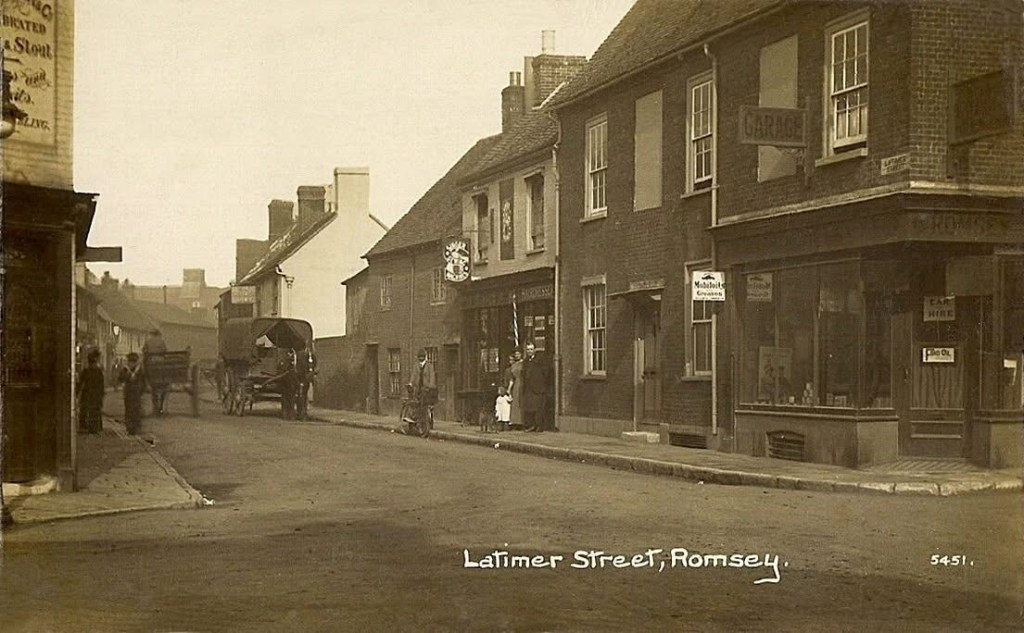

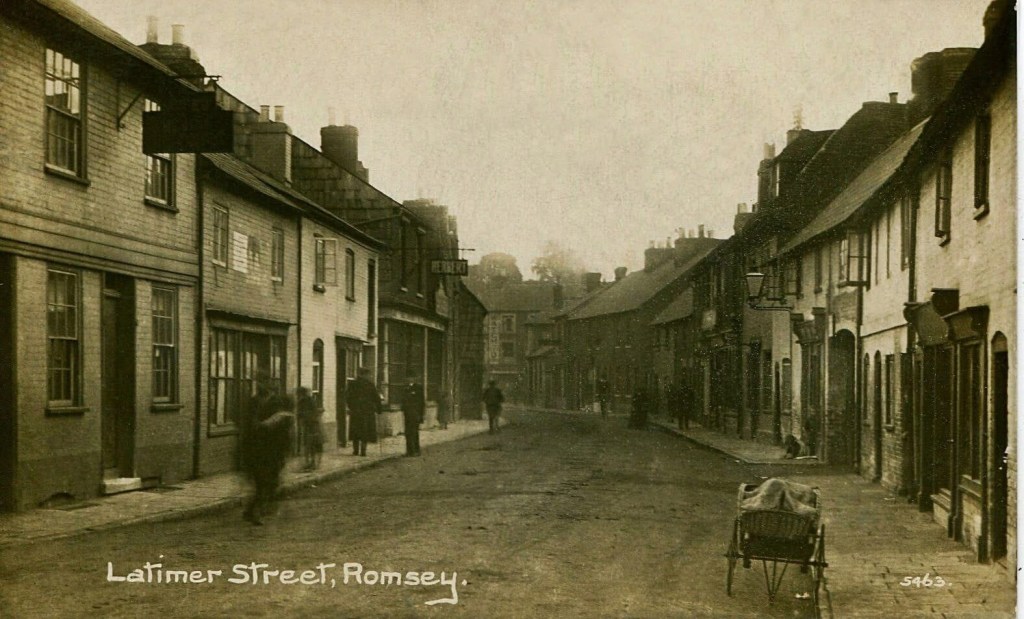

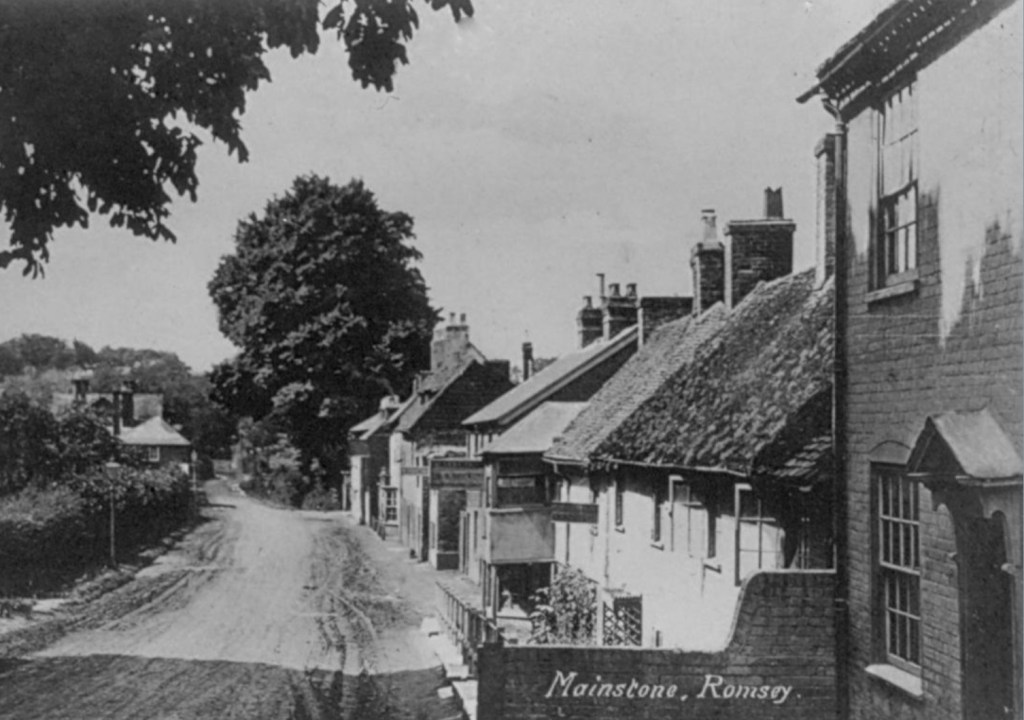

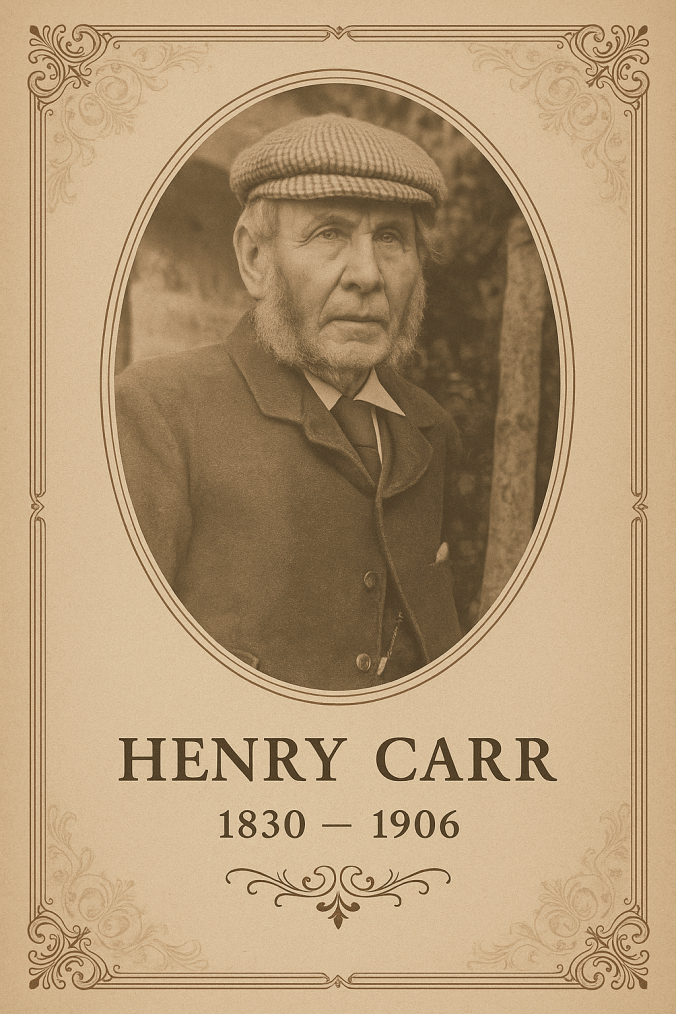

As the autumn days drew to a close, and the trees stood bare, their branches reaching toward the pale sky, Caroline and Henry’s lives were once again filled with the joy of new beginnings. On Wednesday, the 11th day of November, 1863, in their new home on Cherville Street in Romsey, Hampshire, Caroline gave birth to their daughter, Emily Carr. The crisp air outside was filled with the lingering smoke from chimneys, a comforting sign of warmth amidst the season’s change. Emily’s arrival, just as the world around her seemed to sleep in preparation for winter, was a fresh reminder of the hope and beauty that could still spring forth, even in the quietest of times.

Caroline, as was her custom, registered Emily’s birth on Tuesday, the 15th day of December, 1863, in Romsey. The details were recorded by Registrar George Withers, who carefully documented the moment, “On the 11th November 1863, at Cherville Street, Romsey, Emily Carr, a girl, was born to Henry Carr, a sawyer journeyman, and Caroline Carr, formerly Lye, of Cherville Street, Romsey.”

In the usual manner, Caroline signed the official document with her mark, an “X,” a humble testament to her strength and dedication, a mother who cared for her children with love and sacrifice, even when formal education had not been her path. As Emily’s name was logged in the register, it marked the continuation of a family’s story, one that had seen its fair share of challenges but had always emerged stronger, richer, and full of love.

For Caroline and Henry, the birth of Emily was not just the arrival of a daughter, it was a new chapter, a fresh breath of life in a new home. Romsey, with its quiet streets and tranquil surroundings, would be the backdrop to Emily’s early years, where she would grow up surrounded by the love of her parents and the ever-present history of her family. And for Caroline, the days would unfold, not just as a mother of one more child, but as the keeper of her family's legacy, one that would continue to thrive in the hearts of each new generation.

Cherville Street is a historic street located in Romsey, Hampshire, England. Romsey itself has a rich history, dating back to Roman times, and Cherville Street is one of the older streets in the town, bearing witness to its development over centuries. The town is well-known for its proximity to the River Test and its association with the famous Romsey Abbey, a significant historical and religious site.

Cherville Street, like many streets in Romsey, reflects the town’s evolution from a rural settlement to a market town. The street likely began as a small rural path, which developed as Romsey grew in prominence during the medieval period. The town's market status, which dates back to the 12th century, likely influenced the development of streets like Cherville Street, where merchants and townspeople would have conducted business.

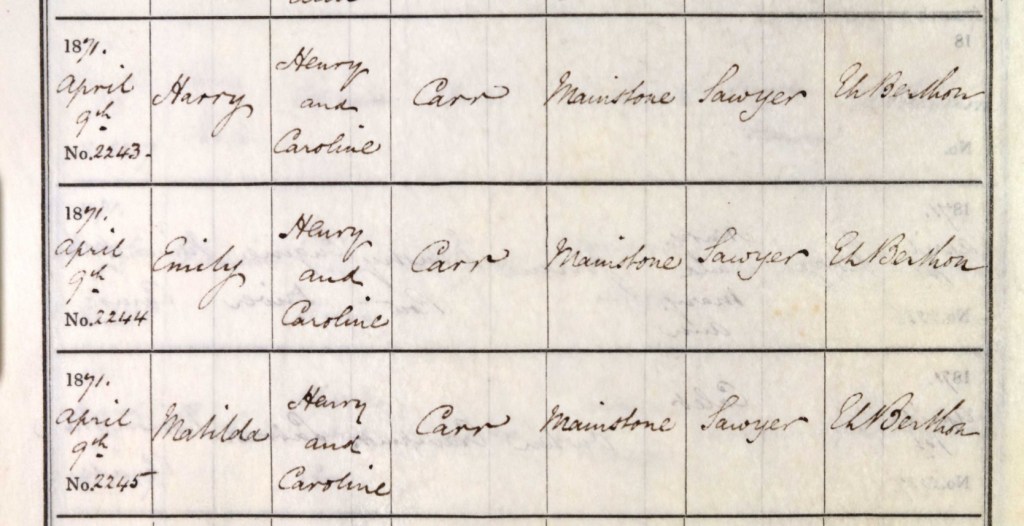

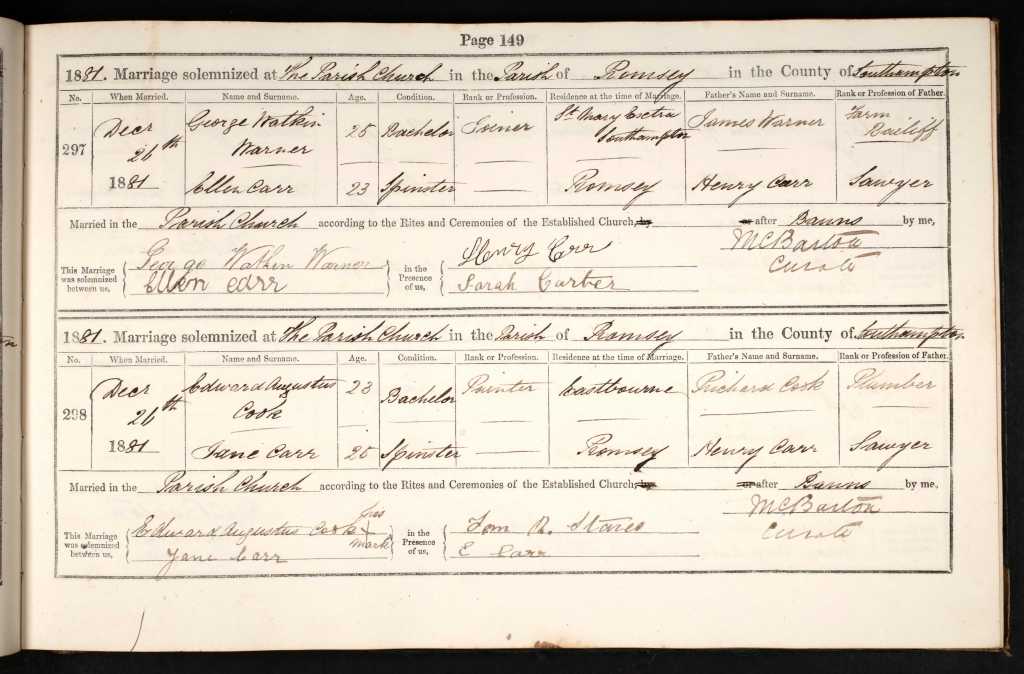

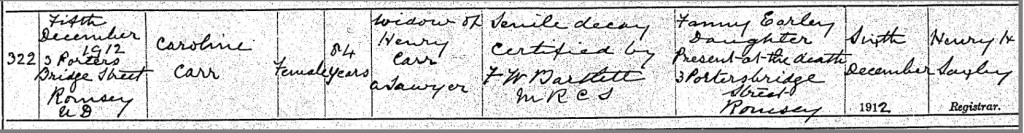

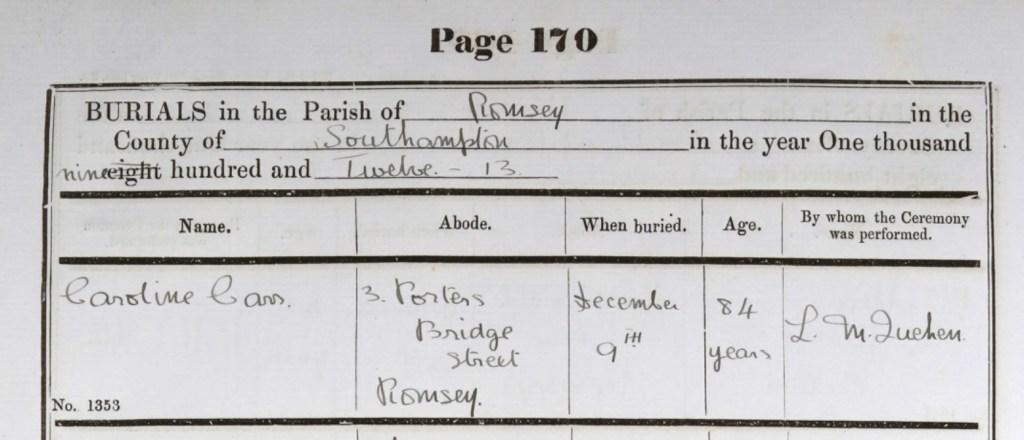

During the Middle Ages, Romsey, and by extension, Cherville Street, would have seen its share of trade, particularly related to wool and other agricultural products. The nearby Romsey Abbey, established in the 9th century and rebuilt in the 12th century, would have had a strong influence on the area, with much of the surrounding land once belonging to the abbey. This ecclesiastical presence shaped the town and, by extension, the development of streets such as Cherville Street.