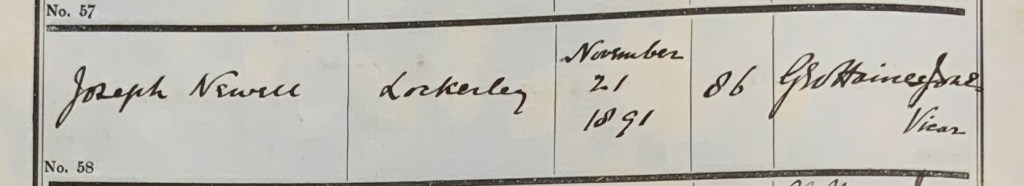

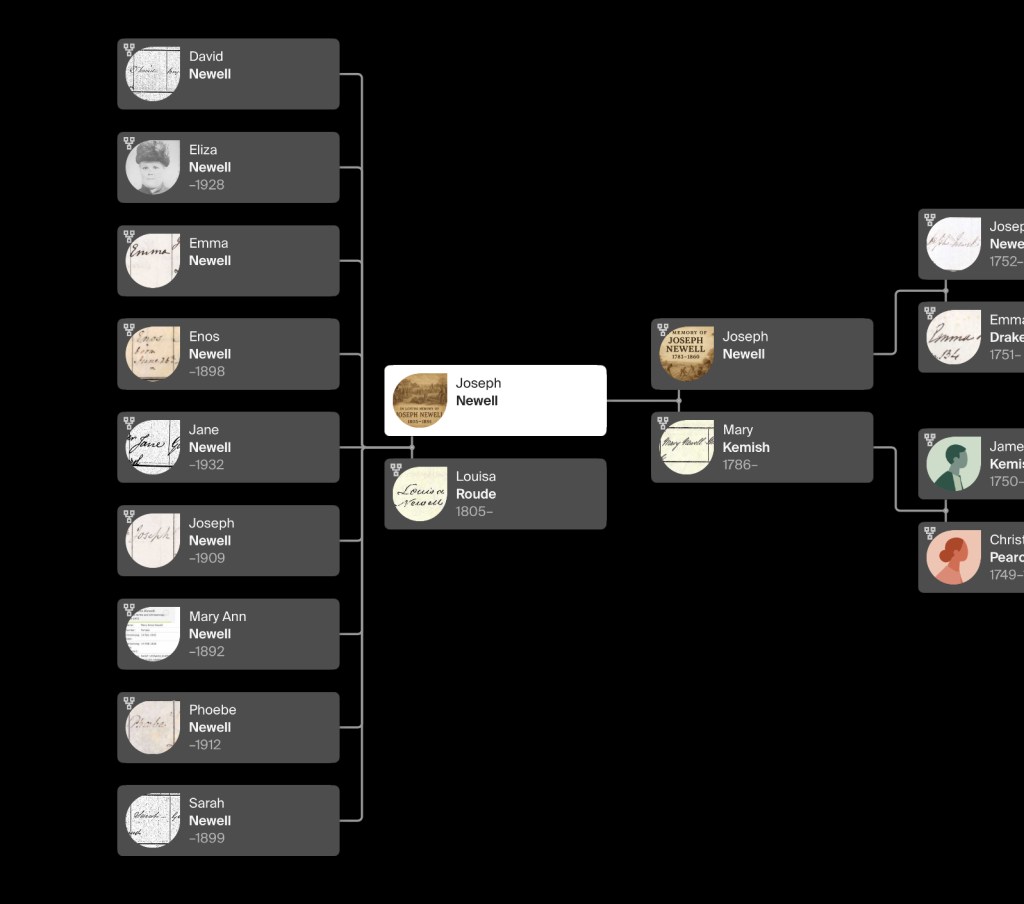

As the years unfolded before him, Joseph Newell found himself standing at the precipice of a new chapter, one that would carry him through the trials, triumphs, and quiet moments that life would offer in the decades ahead. His wedding to Louisa had marked the beginning of a new journey, a path he walked with a heart full of hope and the promise of a love that would guide him through the years to come. In the wake of that momentous day, when vows were exchanged in the simple yet profound sanctuary of Saint Leonard’s Church, Joseph had no way of knowing just how much would change, nor how much would remain steadfast.

The days ahead were filled with the same rhythm he had known in his youth, work on the land, tending to the needs of his family, and the ongoing bond of faith and community that had shaped his early life. But this was a new kind of life, a life built with Louisa at his side, their love woven into the fabric of their shared story. As seasons turned and years passed, Joseph would experience the joys of fatherhood, the heartache of loss, and the steady hum of daily life. Yet, through it all, there would be a quiet strength, an unwavering commitment to family, to faith, and to the land that had seen him grow from boy to man, from laborer to husband, and eventually, to father.

Through it all, Joseph knew that the story he was living was one of both ordinary and extraordinary moments. The love he shared with Louisa would be his anchor, a constant in the ebb and flow of life. And in time, as the sun set on each day, Joseph would look back at the life he had built with a sense of peace, knowing that his journey had been one well-lived, a life full of quiet joys, deep love, and the enduring bonds of family. His story, though humble, was a testament to the power of love, of patience, and of perseverance, values that would guide him until the very end.

In the twilight years of his life, as the seasons continued to pass with the same steady rhythm, Joseph would reflect on everything he had lived through, from the birth of his children to the simple pleasures of a life shared with Louisa, and the steady pulse of the land he had always known. As his story moved toward its inevitable conclusion, he would do so with the grace that had carried him through so many years, steadfast, with love in his heart and the knowledge that his place in this world had been one of deep connection and quiet strength.

Welcome back to the year 1828, Awbridge, Hampshire, England. It is a time of great change and transition, both in the small rural village of Awbridge and across the country. The world Joseph Newell inhabits is one that is deeply shaped by tradition and the rhythms of rural life, but it is also on the cusp of a new era.

The monarch in 1828 is King George IV, who ascended the throne in 1820 after the death of his father, King George III. George IV is known for his extravagant lifestyle and personal indulgences, but his reign is marked by political and social upheaval. The monarchy is increasingly seen as an institution that must adapt to the changing times, as the country moves away from the older, more traditional ways of governance.

The prime minister at the time is the Duke of Wellington, a figure who is both respected and controversial. Though his military accomplishments have earned him admiration, his political career has been marked by a reluctance to embrace change. The government in 1828 is slow to address the demands of reform, which are beginning to stir across the nation. Parliament is still heavily dominated by the wealthy elite, with only a small percentage of the population being able to vote. It is a time of growing discontent, as the working and poorer classes begin to push for more rights and representation. The social and political climate is tense, but the government remains largely conservative, slow to embrace the ideas of reform and social change that will come to define the following decades.

In the world that Joseph inhabits, the differences between the rich, the working class, and the poor are sharply defined. The wealthy landowners, the gentry, live in large, grand estates, where their lives are dominated by luxury and leisure. They dress in fine fabrics, and their homes are furnished with the finest furniture and decor. The working class, like Joseph and his family, live in small cottages, often struggling to make ends meet. They are employed on the land, working as laborers, and their lives are shaped by the rhythms of farming. The poor, those who are unable to find steady work or land to farm, live in even more dire circumstances. They may reside in squalid conditions in the cities, struggling to survive in a world that offers them little opportunity.

Fashion in 1828 reflects the differences in social class. For the wealthy, clothing is elaborate and fashionable, with men wearing coats with long tails, waistcoats, and breeches, while women wear dresses with high collars and full skirts, often made from fine silks and decorated with lace. The working class, on the other hand, dress simply in durable, practical clothing. Joseph and Louisa, like most in their position, wear sturdy woolen garments designed for work, but they also take pride in looking presentable when they attend church or social gatherings.

Transportation in 1828 is still slow by modern standards, with most people traveling by foot, horseback, or in horse-drawn carts. The roads are often muddy and uneven, and it can take hours or even days to travel short distances. The railway is beginning to take shape in some areas, but it is still in its infancy and not yet a common mode of transportation in rural villages like Awbridge. The postal system, though improving, still relies on slow, horse-drawn mail coaches to deliver letters and parcels, often taking several days for messages to travel from one place to another.

Housing in 1828 is often cramped and basic, especially for the working class. Many live in small cottages with thatched roofs, single rooms for families, and minimal furnishings. The wealthy live in large, well-appointed homes with many rooms, servants, and elaborate furnishings. In the rural areas, most homes have a central hearth for heating, but there is no indoor plumbing or modern conveniences. The working class may have to fetch water from a well, and outdoor privies are common.

Heating and lighting are still very rudimentary by today’s standards. Most homes rely on open fires for warmth, and the air is often filled with smoke. Candles made from tallow or beeswax provide the only illumination in the evenings, and lanterns are used when traveling after dark. The wealthy may have oil lamps, but they are a luxury not available to most.

Hygiene and sanitation in 1828 are primitive, especially for the working class. Bathing is infrequent, and the poor often have to make do with a quick wash in a basin. There are no public toilets, and sanitation is rudimentary at best. Waste is disposed of in cesspits or thrown into the streets in some cities, creating unsanitary and often dangerous conditions. In rural areas like Awbridge, the lack of modern sanitation is less apparent, but conditions are still challenging.

Food in 1828 is basic for the working class, with much of their diet consisting of bread, potatoes, and simple stews. Meat is a luxury, often reserved for special occasions. The wealthier classes, however, have access to a greater variety of food, including fresh fruits, meats, and imported goods. Vegetables, dairy, and grains make up the bulk of the diet for most, with meat being eaten infrequently.

Entertainment in 1828 is largely centered around community gatherings, music, and local events. In rural villages like Awbridge, Sunday church services are a central part of social life, and gatherings in the local pub are a common form of entertainment. The wealthy attend theaters, balls, and other social events, while the working class enjoys simpler pleasures, such as village fairs or storytelling. Music, played on simple instruments like fiddles or flutes, provides entertainment for those who cannot afford expensive performances.

Diseases in 1828 are a constant threat, with medical knowledge still in its infancy. Illnesses like tuberculosis, smallpox, and cholera are common, and many people live in fear of outbreaks. The lack of sanitation and proper medical care makes it difficult to control the spread of disease, and the poor are especially vulnerable. There are no vaccines or antibiotics, and treatments are rudimentary at best.

The environment in 1828 is still largely unspoiled, with vast areas of farmland and natural landscapes. The industrial revolution is beginning to take hold in some parts of the country, but in rural villages like Awbridge, life is still shaped by agriculture. The air is fresh, and the countryside is alive with the sounds of nature. However, this would soon change as industrialization and urbanization begin to affect the environment in the coming decades.

Gossip in 1828 spreads quickly through small villages, where everyone knows everyone else’s business. Social gatherings, like church services and village fairs, provide ample opportunities for the exchange of news and rumors. In the absence of modern communication, word-of-mouth is the primary means of sharing information.

Schooling in 1828 is still a luxury for many, especially for the children of the working class. Education is often reserved for the wealthier families who can afford to send their children to school. For most children, education consists of basic reading, writing, and arithmetic, taught at home or in small local schools. The concept of compulsory education is still a long way off, and many children begin working at a young age to help support their families.

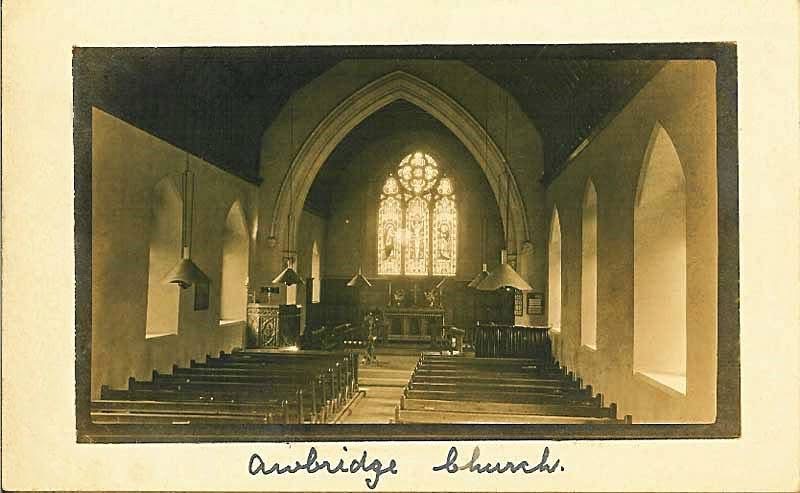

Religion in 1828 is a central part of life for most people. The Church of England is the dominant religious institution, and most people in rural areas like Awbridge attend church regularly. Religion provides not just spiritual guidance but also a sense of community and identity. Sunday services are a time for reflection and worship, and the church is a focal point of social life. The rector or curate plays an important role in village life, offering not just religious guidance but also helping to mediate disputes and offer counsel.

In 1828, life is defined by a delicate balance between tradition and the forces of change. It is a time when the gap between the rich and the poor is stark, but also one when new ideas are beginning to stir. The country may be on the brink of industrialization, but in rural villages like Awbridge, the pace of life remains slow and steady. For Joseph Newell, and many others like him, life is shaped by the land, the seasons, and the deep connections that bind family and community together. The winds of change may be beginning to blow, but for now, the simplicity of life in the countryside endures.

In the late summer of 1828, Joseph and Louisa were beginning to settle into their life together in Awbridge, nestled in their new home. Joseph had always felt a deep connection to the land, to the village, and to the rhythms of rural life, but now, with Louisa by his side, everything felt different. It was as though a new chapter was unfolding before him, one that was full of promise and a fair bit of uncertainty. The future, once a distant thought, now felt immediate, pressing in with the sweetness of new beginnings and the weight of what was to come.

At the same time, the joy of their own new life together was mirrored by the arrival of a new child in Joseph’s family. His beloved mother, Mary, had just given birth to another son. Charles Newells. Joseph’s heart swelled with affection as he thought of the new life that had just been brought in to their family, his brother, Charles. The idea of becoming an older brother again, to a child born to his mother in her later years, filled Joseph with a sense of awe. Mary had always been a pillar of strength in Joseph’s life, and now, in her maturity, she was brought yet another child into the world, a symbol of her enduring love and resilience.

While Joseph’s wife Louisa was heavily pregnant with their first child, the two women, Mary and Louisa, had spent much of the late summer together. Louisa, eager and filled with questions, was learning the ways of motherhood from the woman who had raised Joseph and his siblings with such steady hands. Louisa sought advice and comfort from Mary, her own uncertainty about childbirth softened by Mary’s calm, reassuring presence. As Mary shared her wisdom, telling Louisa of what to expect, of the ways to prepare, and how to care for a newborn, Louisa began to feel a sense of confidence settle within her. Joseph could see the bond growing between them, as if Louisa were being gently guided on her own journey into motherhood, with the warmth and care of the woman who had shown him what it meant to love and nurture.

Watching this quiet exchange between the two women, Joseph couldn’t help but feel a deep sense of gratitude. He knew that soon, his life would change forever. The joy of being a brother had already shaped him, but now, as Louisa’s due date approached, he would soon step into the unknown role of fatherhood. He felt both the excitement and the weight of the responsibility that came with it. But before his own child was born, Joseph would have the opportunity to cherish his new brother, Charles, whose arrival felt like a quiet blessing. The idea that his mother, now older, was still bringing life into the world made Joseph’s heart swell with affection and admiration. Mary’s strength, resilience, and love had shaped him into the man he was, and now, seeing Louisa preparing for motherhood with her guidance, Joseph felt a sense of reassurance. He knew that Louisa, too, would rise to the challenges of motherhood with the same grace and strength that had marked Mary’s life.

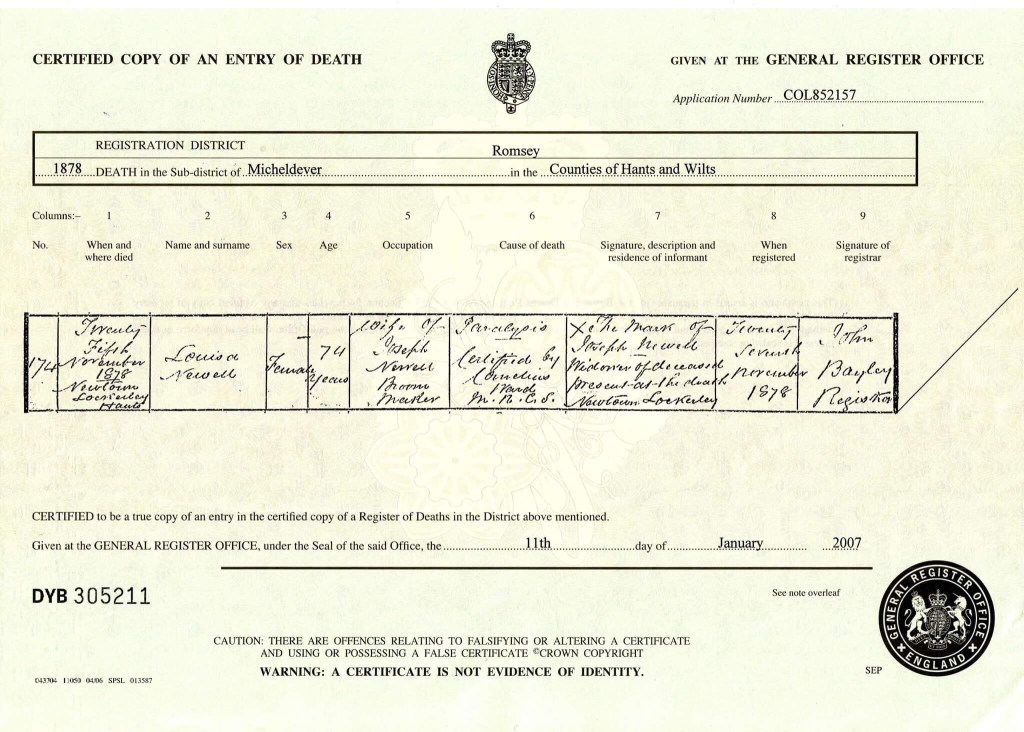

As Louisa leaned on Mary’s steady guidance, growing more confident in what to expect, Joseph saw in them both a shared strength, a bond that transcended the years between them. The quiet moments spent with Mary were a comfort to Louisa, as she prepared herself for the journey of motherhood that lay ahead. And as Joseph reflected on the arrival of his new brother, he knew that the Newell family was growing, not just in number, but in love, connection, and tradition.

For Joseph, this time was a moment of reflection. A time to pause and take in the fullness of his life. He thought of the love that had shaped him, the woman who was soon to be the mother of his child, and the mother who had raised him with such care. The world Joseph had always known, the village, the land, the family, was richer, fuller, and more deeply rooted than ever. With Louisa by his side and Charles sleeping peacefully in his mother’s arms, Joseph couldn’t help but feel an overwhelming sense of gratitude for the life he had and the future he was about to build.

Though the exact date of Charles' birth and his location are not definitively known, the censuses provide a rough outline: in 1841, Charles is listed as born in Hampshire, and the later censuses (1851, 1861, 1871, 1881, 1891, and 1901) consistently show him as born in Awbridge in 1829, although some records list him as being born in 1849. These discrepancies are common in census records, as the passage of time often muddles specific details, but what mattered most to Joseph was the arrival of his new brother, who would soon become an important part of his life and his children’s lives.

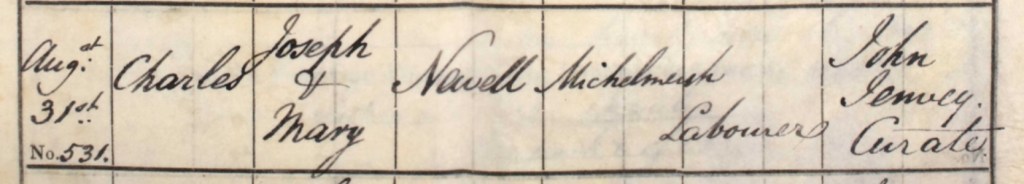

On a warm summer’s day, Sunday the 31st day of August, 1828, Joseph, his wife Louisa, and their family made their way from Awbridge to St. Mary’s Church in Michelmersh. Louisa, heavily pregnant with their first child, walked beside Joseph, her hand resting gently on her belly, as they made their way through the familiar lanes of their village. The day was peaceful, filled with the soft hum of summer, and the air was filled with the promise of both new beginnings and memories of the past. The purpose of their visit was not only for Sunday service but also for the baptism of Joseph’s baby brother, Charles, the new addition to the family who would soon be welcomed into the Christian faith.

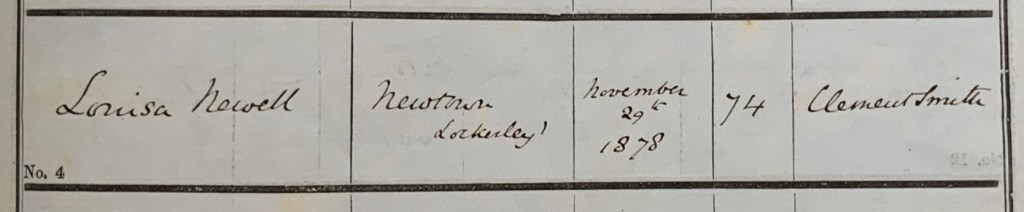

The church stood before them, its weathered stone walls bathed in sunlight, and as they entered the cool, quiet space, Joseph could feel the weight of the moment. His parents, Joseph and Mary, stood together at the baptismal font, their hands clasped in prayer as they prepared to mark the beginning of their son's spiritual journey. Joseph had been baptised there many years before, and now, it was Charles’ turn. The ceremony was led by Curate John Jemvey, whose steady voice filled the church with reverence as the sacred waters were poured over Charles’ small head. The soft sound of the water mingled with the quiet murmur of the congregation, as Charles’ name was spoken aloud, and his family, Joseph, Mary, Louisa, and the others, watched on with hearts full of love.

Once the baptism was complete, and the ceremony came to a close, Joseph and his family left the church, their thoughts turning to the past. As they made their way across the church grounds, they most likely visited the grave of Joseph’s sister, Mary, who had passed away in her youth, a baby in arms. Standing together in the stillness, they offered silent prayers, remembering her and honoring her memory in the quiet, reverent space beneath the towering trees. It was a moment of reflection, of connection to both the past and the present, as they stood as a family, bound by love and faith.

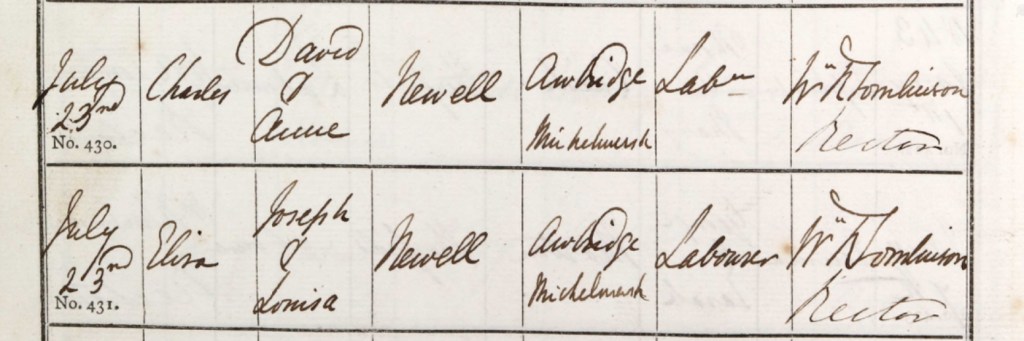

Meanwhile, Curate Jemvey had returned to his duties. At the back of the church, he carefully filled in the baptismal register for baptism solemnised in the parish of Michelmersh, in the county of Southampton in the year 1828. He wrote:

31st August 1828, Charles Newells, son of Joseph and Mary Newell, labourer, of Michelmersh.

With a final flourish, he signed his name, the ink slowly drying on the page, a permanent record of the day. Having completed the formalities, he joined his congregation in the churchyard, stepping out into the warmth of the summer day, where the sounds of village life could be heard in the distance.

For Joseph, this day held both joy and sorrow, a celebration of his brother's new life in the faith, and a quiet moment to remember those lost too soon. Yet, as he looked at his family gathered around him, Louisa, his parents, his siblings, he couldn’t help but feel a deep sense of gratitude. They were together, they were strong, and they were bound not just by blood, but by faith, tradition, and the enduring love that had carried them through all the seasons of life.

In the autumn of 1828, Hampshire, England, was a breathtaking tapestry of colours, vibrant oranges, deep reds, soft browns, and golden ambers filled the countryside as the land prepared itself for the coming of winter. The trees swayed in the crisp breeze, shedding their leaves, while the scent of earth and wood filled the air. It was in this season of change that Joseph and Louisa welcomed their first child into the world, a son. The birth took place in their modest home in the quaint village of Awbridge, a place Joseph had known all his life, a place now made even more meaningful by the presence of his new family.

Louisa, though exhausted from the pains of childbirth, was filled with a quiet joy as she cradled their son. The air in the room was thick with the weight of the moment, the beginnings of new life, the start of a new chapter. Louisa handed the newborn to Joseph, who took him in his arms with a look of absolute pride and love. He could hardly believe that this tiny, perfect child was now his son, their son, the beginning of a new generation. In that moment, Joseph knew that this child would not only carry the Newell name forward but would also carry the name of Joseph, as his father and grandfather had before him, a legacy of strength, humility, and love that had been passed down through the generations.

Though we do not know the exact day of Joseph’s birth, the censuses offer us glimpses into the year and location. The 1841 census places his birth year and location as 1828, Hampshire. The 1851 census lists it as 1829, in Sherfield English, while the 1861 census marks it as 1830, still in Hampshire. By 1871, Joseph is listed as having been born in Awbridge in 1848, but the more consistent records from 1881, 1891, and 1901 all place his birth year around 1829, still in Awbridge. Though the exact details are somewhat unclear, what is certain is that Joseph was born into a family that had long been established in Hampshire, a family whose roots ran deep in the soil of this land.

For Joseph and Louisa, the birth of their son was a momentous occasion. It was not just the arrival of a new life, but a reaffirmation of their place in the world, their connection to the land, and the generations that had come before them. Their son, Joseph, was now a part of that legacy, bound to the same land that had shaped his father and grandfather. As the autumn leaves fell outside, Joseph knew that the season of change had brought with it something beautiful, a new life, a new future, and the continuation of a name that had carried so much history.

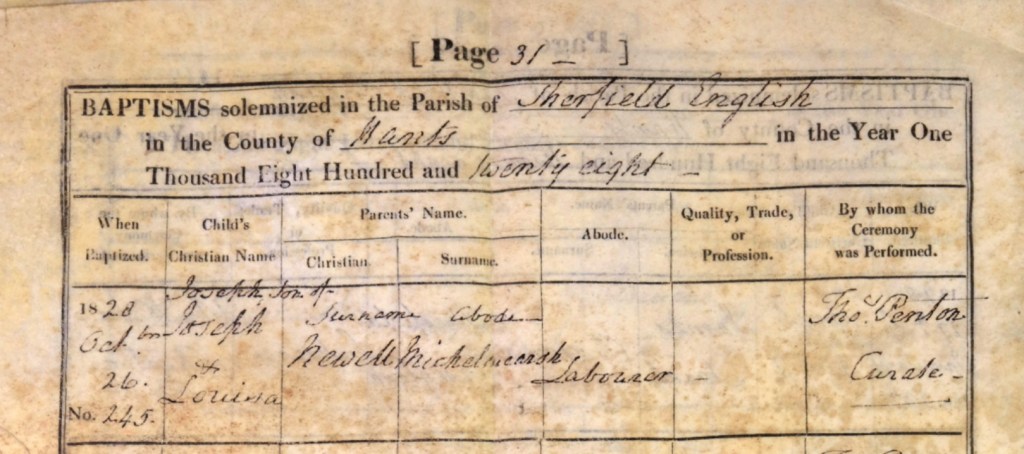

On Sunday, the 26th of October, 1828, a significant event took place at the old Saint Leonard’s Church in Sherfield English, Hampshire, England. Joseph Newell, the infant son of Joseph and Louisa Newell, was baptised within the humble walls of this historic parish church. At the time, the Newell family resided in Michelmersh, a quiet village just a short distance away, where Joseph Senior worked as a labourer, a common and respectable trade in the rural communities of the era. Despite their modest means, the baptism was an event filled with profound meaning, marking not just the spiritual beginning of young Joseph’s life, but also his connection to the faith and traditions of his family and community.

The baptism was solemnly performed by Reverend Thomas Pentin, the curate who served the parish. With reverence and warmth, the water was poured over the infant’s forehead, the simple ritual binding Joseph to the long-standing traditions of the Church of England. The small, sacred moment was witnessed by close family members and the local parish community, an intimate gathering, yet one with far-reaching significance. In this place, generations before had gathered to worship, celebrate, and share in life’s milestones, and now Joseph, their newest member, was linked to that same history.

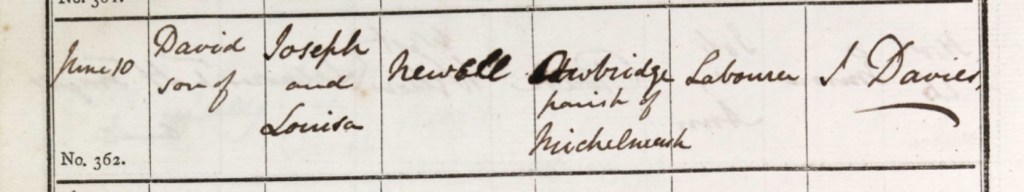

Reverend Pentin carefully filled out the baptismal register after the ceremony, noting the key details of the baptism. In his, elegant handwriting, he recorded:

“1828, October 26th, No. 245, Joseph Newell, son of Joseph and Louisa, surname Newell, abode Michelmersh.”

With a final flourish, he signed his name in the register, leaving a permanent record of this sacred moment.

Though simple, the occasion was an affirmation of faith and tradition, one that would ripple through the lives of Joseph and Louisa for years to come. The solemnity of the ceremony held an unspoken promise of belonging, not only to the Church of England but to the enduring legacy of faith, family, and community that had been passed down through the generations in this rural corner of Hampshire. In this quiet, sacred space, Joseph’s baptism at Saint Leonard’s Church stood as a beautiful connection to a past rich with history, and to a future full of hope, love, and the shared bond of family.

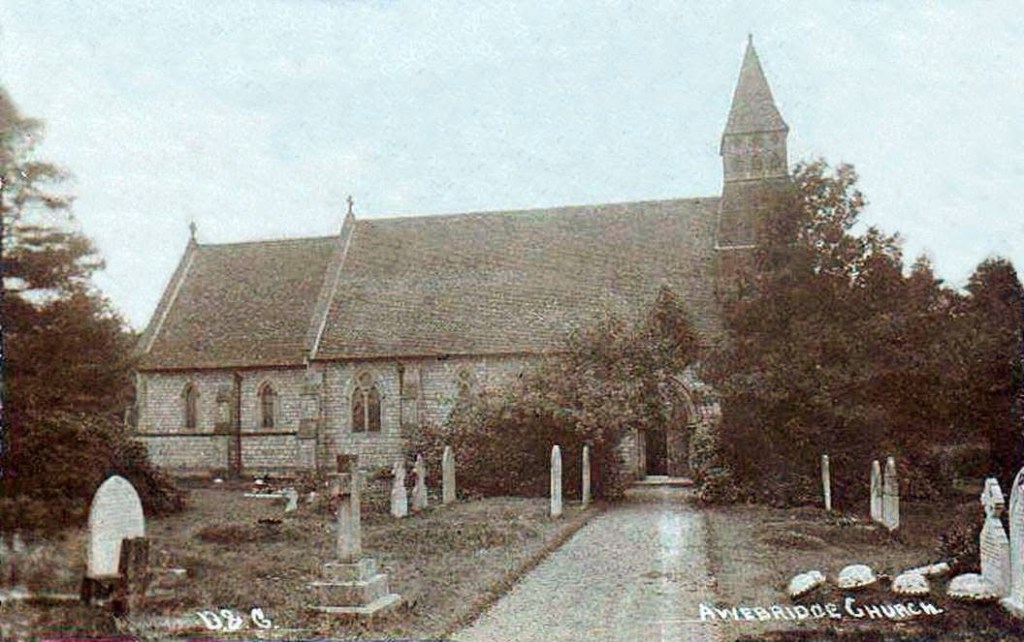

Saint Leonard’s Church in Sherfield English, Hampshire, has a rich history that stretches back over many centuries. The church has been a central part of the village’s religious and community life, and its history reflects the broader development of the area from medieval times to the present. The original Saint Leonard’s Church is believed to have been built in the early medieval period, likely during the Norman era, around the 12th century. The church would have been a simple structure, typical of rural churches of the time. As was common with churches in small villages, it was likely constructed with local materials such as stone and timber, with a simple design reflecting the needs of the local community. The church was dedicated to Saint Leonard, a popular saint during the medieval period who was often invoked for protection and for his association with prisoners and captives. Saint Leonard’s cult was widespread across England, and many churches were named in his honor. The original church at Sherfield English served as a focal point for the small agricultural community, providing a place for worship, social gatherings, and important life events such as baptisms, marriages, and funerals. The church would have also been a place where the villagers came together for communal activities, and it played an essential role in maintaining the spiritual and social fabric of the community. Over time, the church likely underwent several modifications and additions, particularly in the 14th and 15th centuries, as the village expanded and the needs of the local population grew. These changes were likely driven by the growing wealth of the parish as the agricultural economy strengthened. In the 19th century, however, the old church began to show signs of wear and was no longer able to adequately serve the growing population of Sherfield English. By the early 1800s, the church building had become dilapidated and was deemed inadequate for the needs of the parish. At this point, the decision was made to construct a new church to better serve the community. The new Saint Leonard’s Church was built in 1840, a year that saw the completion of many church restoration projects across rural England, driven in part by the Victorian era’s focus on reviving medieval architectural styles. The new church was built on a site adjacent to the old church, though some sources suggest that it may have been on the same footprint or nearby. The architect responsible for the design of the new church was likely influenced by the popular Gothic Revival style of the time, which was characterized by pointed arches, stained-glass windows, and spires. The new church was intended to accommodate the needs of the growing population of Sherfield English, and it was designed to be larger and more architecturally impressive than its predecessor. The construction of the new church was part of a broader trend of church building and restoration during the Victorian period, a time when many rural churches were being rebuilt or restored to reflect the prosperity of the period. The old Saint Leonard’s Church, after the new one was completed, was demolished, as was often the case with churches that were deemed structurally unsound or inadequate for modern use. It is common for older church buildings to be torn down when a new structure is built, particularly if the old building no longer meets the needs of the local population or has fallen into disrepair. It is likely that the materials from the old church were repurposed for the new construction, as was the custom at the time, though no records have definitively confirmed this. Today, Saint Leonard’s Church stands as a beautiful example of Victorian church architecture, with its stained-glass windows, pointed arches, and graceful tower. The church continues to serve the community, offering regular worship services, community events, and providing a space for reflection and connection. The church is also known for its picturesque setting within the village, surrounded by well-kept churchyards and the rolling countryside of Hampshire. The new church, while a product of the 19th century, retains the essence of the old church’s purpose to serve as a spiritual hub for the village of Sherfield English.

As the early morning mist lifted from the meadows, the sun’s gentle warmth began to glint off the dew-laced hedgerows, and the sounds of birdsong stirred in the surrounding oak and ash trees. The lanes, still rutted from cartwheels and softened by spring rain, carried the scent of damp earth, wild garlic, and budding bluebells. The nearby River Test, which wound lazily through the landscape, trickled with renewed life, a reflection of the season’s awakening.

The cottages, their thatched roofs darkened by the winter past, began to dry in the light of the rising sun, smoke curling lazily from chimneys as families inside stirred and began their day. At the edge of the fields, farmers and laborers, clad in coarse smocks and sturdy boots, bent to their planting or turned the soil with horse and plough, their movements rhythmic and sure. The air was fresh and cool, yet promising warmth, and the gentle hum of bees began to return, flitting between primroses and the early blossoms of hawthorn trees.

In the gardens, children, barefoot and curious, helped gather eggs from hens, their laughter mingling with the crow of a distant rooster. Inside the modest homes, the comforting smells of baking bread or stewing turnips wafted through the air, offering a sense of continuity in a world that seemed to turn with the steady rhythm of the seasons.

It was in the cozy walls of Joseph’s parents’ home in Awbridge, during the spring of 1830, that Joseph’s baby brother, George, was born. The house, filled with the warmth of family and the sounds of village life, welcomed a new life into its fold. The world outside, with its blooming flowers and growing fields, mirrored the growth of the Newell family, as Joseph's family expanded once again.

Although an exact date for George’s birth remains unknown, the censuses offer a glimpse into his life and the year of his birth. The 1841 census lists his birth year as 1831 in Hampshire, while the 1851, 1861, 1881, 1891, and 1901 censuses consistently mark his birth year as 1830 in Awbridge, Hampshire. Interestingly, the 1871 census places his birth in Romsey, Hampshire, but all records point to the same central theme: George was a son of Awbridge, born in the spring of 1830, a child who would grow up alongside Joseph in the village that had shaped their lives.

For Joseph, George's birth brought a quiet joy, marking another step in the growth of his family and the continuation of the Newell name. It was a simple moment in the flow of village life, but one that would shape Joseph’s world as he watched his brother grow alongside him and his own infants in, Joseph, in the familiar rhythms of Awbridge, surrounded by the same land, the same community, and the same enduring legacy of family.

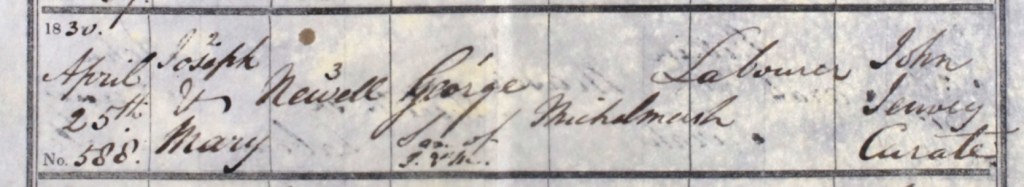

On Sunday, the 25th day of April in the year 1830, the parish of Michelmersh in Hampshire stirred gently beneath a soft spring sun. The morning air was fresh, carrying the scent of damp grass and wild primroses blooming along the hedgerows. At the heart of the village stood the ancient stone church of St. Mary’s, its square Norman tower rising proudly above the treetops, and its bells calling the faithful to worship. Families from the surrounding cottages and farms made their way along muddy tracks and well-worn footpaths, dressed in their Sunday best, bonnets neatly tied, boots brushed, and shawls drawn against the lingering chill of the morning.

Inside St. Mary’s, the cool stone walls echoed faintly with the rustle of prayer books and murmured greetings. The flicker of candlelight caught the worn edges of the wooden pews and the brass fixtures around the simple font that had seen centuries of baptisms. The scent of candle wax mingled with the earthy aroma of the spring day, grounding the sacredness of the moment. On this particular morning, the congregation gathered with quiet reverence to witness the baptism of George, the son of Joseph and Mary Newell, and brother to Joseph.

Curate John Jemvey, clad in his white surplice and black stole, led the service with steady calm, his voice ringing clear through the ancient church as he read the baptismal liturgy from the Book of Common Prayer. His words seemed to fill every corner of the space, connecting those present to centuries of worship. The baptismal font, worn smooth by generations of faithful hands, was filled with clean holy water, its surface shimmering in the light of the candles. Jemvey cradled the infant George in his arms, his face soft with the quiet solemnity of the occasion. Gently, he poured the water over the child’s forehead in the name of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost, as the congregation looked on with a mixture of solemnity and joy. In that moment, the church, though small, felt vast with the weight of tradition, the gathering of the faithful in prayer, and the new life being brought into the fold of the Christian community.

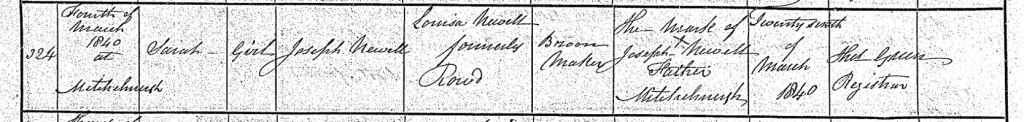

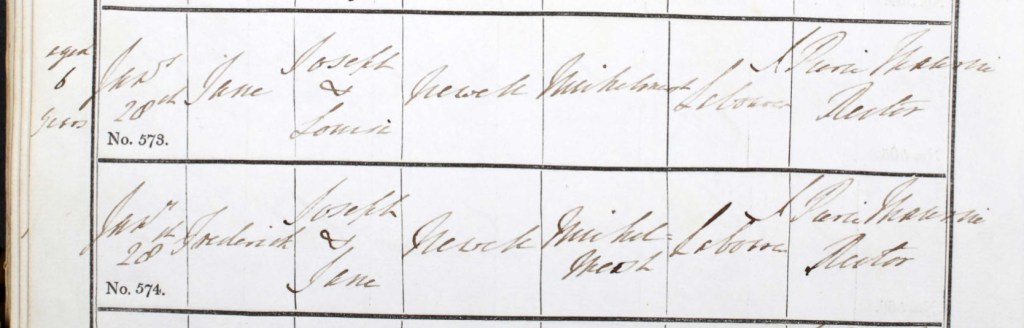

The moment was quietly profound, marking the beginning of George’s life within the church and the wider community. After the blessing, Jemvey carefully recorded the details in the parish register with steady penmanship, his hand moving gracefully over the page. 1830 April 25th, No. 588, George Newell, Son of Joseph and Mary, Michelmersh, Labourer. The ink dried as the congregation lifted their final hymn, voices rising beneath the old wooden beams and stone arches of St. Mary’s, a song of joy and thanksgiving for the new life baptised into their midst.

Outside, the churchyard shimmered with the fresh green of new leaves, and the spring day continued on, carrying with it the echo of prayers and the soft coos of a newly baptized babe. The world outside the stone walls of St. Mary’s was full of life, but in that moment, the church stood as a quiet sanctuary, filled with the sacred promise of faith, family, and community, a promise that would guide George’s life from that day forward.

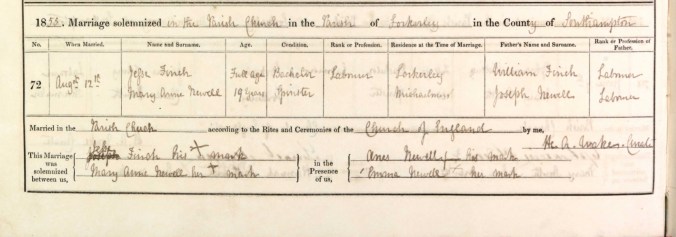

Autumn leaves were falling from the trees, the flowers displaying their final burst of color for the year, as the fields of Michelmersh, Hampshire, were in full swing. The season’s work was being carried out with steady hands and familiar rhythms, and in the midst of it all, Joseph, aged about 25, and his wife Louisa, aged about 26, were creating a life together in their cozy home. Along with their young son, also named Joseph, they made their home in the heart of this picturesque village. It was during this season, when the harvest was winding down and the crisp air of autumn settled in, that the Newells welcomed a new addition to their family, their daughter Emma. Her birth, though the exact date remains unknown, marked a new chapter for the young family, their hearts swelling with the joy of this little girl. The joy of her arrival was a quiet but significant moment in their lives, one that bound the family even more tightly together in the warmth of their home. The census records provide us with a rough idea of Emma’s birth year and location. The 1841 census shows her birth year as 1830 in Hampshire, while the 1851 census places her birth year in 1831 in Sherfield English. The 1871 census lists her as born in Awbridge, and in 1881, she is marked as born in Romsey, which suggests that she spent her life in the area, moving between these nearby towns, though it’s clear that Hampshire remained her home. Emma’s arrival added to the Newells’ deep connection to the land, the community, and the rhythm of rural life in Hampshire. Though her birth date remains elusive, the joy she brought to Joseph and Louisa, along with the growing family, is clear, a family built on love, hard work, and a deep sense of place.

Joseph and Louisa Newell, with their hearts full of love and joy, brought their daughter Emma to be baptised on Sunday, the 19th day of December, 1830, at the old, original Saint Leonard’s Church in Sherfield English, Hampshire. The winter air was cool and crisp, and the quiet of the village seemed to amplify the sacredness of the day. The church, with its timeworn stone walls and tall, graceful tower, stood as a symbol of enduring faith, the perfect place for the baptism of a child born into a family so deeply connected to the land and community.

The ceremony was led by Reverend Thomas Pentin, the curate of the parish, who, with his steady hand and calm demeanor, performed the rites of baptism. His voice, both strong and reassuring, filled the church as he gently poured water over young Emma’s forehead, marking the beginning of her spiritual journey. The congregation, gathered in quiet reverence, witnessed this sacred moment, a milestone not just for the Newell family, but for the community of Sherfield English, where generations before had been baptised and gathered in faith.

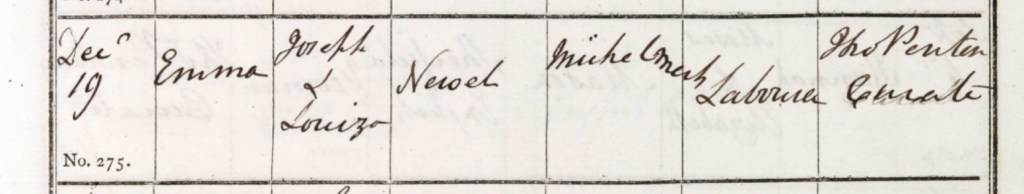

After the ceremony, Reverend Pentin carefully filled out the baptismal register, recording the important details with the precision and care that such moments warranted. In his clear handwriting, he filled in the boxes for the baptism solemnized in the parish of Sherfield English, in the county of Southampton, in the year 1830. The register reads:

Dec 19th, No. 275, Emma, Joseph and Louisa, Newel, Michelmersh, Labourer.

Though Reverend Pentin spelled the surname as "Newel" instead of "Newell," his steady hand captured the significance of the day, Emma’s name now recorded alongside her parents’, marking her place in both the church and the long history of her family.

With the baptism completed, the Newell family left the church, their hearts filled with quiet gratitude for the new life that had been blessed and the new chapter that had begun for Emma. Outside, the chill of winter began to settle, but inside, the warmth of family, faith, and love lingered, a reminder of the enduring legacy that Emma, like the generations before her, would carry forward.

Spring had come to the quiet village of Michelmersh in Hampshire, with the cuckoo’s cheerful song stirring the villagers from their slumber and lambs frolicking in the fields, their joyful leaps a sign of the season's renewal. The year was 1833, and the days were growing longer as the harvest was being planted. The land, freshly awakened after the long winter months, was filled with the promise of growth and new beginnings. It was a season of change, not just for the fields but for Joseph and Louisa as well, for they were celebrating the arrival of their second daughter, Phoebe.

Phoebe's birth was a moment of joy, filling the Newell household with the sounds of a newborn's cry and the playful patter of toddlers' feet echoing through the humble walls of their cottage. The family, now expanding with each passing year, was thriving in the rhythm of village life. The birth of Phoebe was a new chapter for Joseph and Louisa, marking the growth of their family in the same way the land around them was flourishing with the promise of the future.

Though Phoebe’s exact birth date remains a mystery, the census records offer us clues about the year and location of her birth. According to the 1841 census, Phoebe was born in 1832 in Hampshire, while the 1851 census lists her birth year as 1832 in Romsey. The 1861 census places her birth year as 1833 in Michelmersh, and the 1871 census marks it as 1834 in Michelmersh. Later records in the 1881 and 1891 censuses list her as born in 1834, in Awbridge, spelled as "Awebridge" in both years. By the 1901 and 1911 censuses, Phoebe was again recorded as being born in Michelmersh, reflecting the family’s steady connection to the land they had always called home.

Phoebe’s arrival, like the blooming of the spring flowers around their cottage, brought renewal to Joseph and Louisa’s lives. Each census record traces her growth, from the young girl of Michelmersh to the woman who would help carry forward the legacy of the Newell family. The years passed, and the Newell household continued to grow, but Phoebe’s early years in that small cottage, filled with laughter and the cries of new life, would always be a cherished memory for her parents and the community.

On Sunday, the 19th day of May, 1833, Joseph, Louisa, and their children, Joseph, Emma, and baby Phoebe, made the journey from their home in Michelmersh to the old, original Saint Leonard’s Church in Sherfield English for Sunday service. This was no ordinary Sunday, it was a day of great significance, a day when they would welcome their youngest daughter, Phoebe, into the Christian faith and the community. The journey, though not far, would have felt like a momentous occasion, one marked by the quiet anticipation of what was to come.

As they entered the ancient church, with its weathered stone walls, a sense of reverence would have settled over the Newell family. This was the same church where generations before had been baptised, married, and buried, and now, in its hallowed space, Phoebe would join that long line of faithful souls. The service, led by Thomas Pentin, the curate of the parish, was filled with the solemnity and joy of the sacrament.

Curate Pentin, dressed in his white surplice and black stole, gently cradled Phoebe in his arms, preparing to perform the baptism. With a steady hand and a calm voice, he poured water over Phoebe’s forehead in the name of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit, marking her as a child of God. The congregation, gathered with quiet reverence, witnessed the baptism with joy and solemnity, knowing that Phoebe was now part of the wider community of faith.

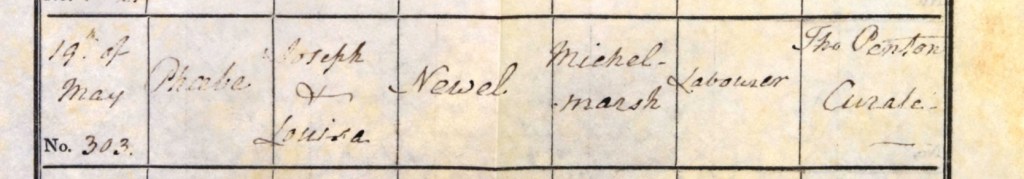

After the service, Reverend Pentin carefully filled out the baptism register, recording the important details with steady penmanship. His words in the register would be a lasting record of Phoebe’s place in the parish of Sherfield English:

"19th May 1833, Phoebe Newell, daughter of Joseph Newell, a labourer, and Louisa Newell, of Michelmarsh, was baptised in the parish of Sherfield English, in the county of Southampton."

With a final flourish, he signed his name, ensuring that Phoebe’s place in the history of the church and the community was marked forever.

As the Newell family left Saint Leonard’s Church, their hearts would have been full, not just with the joy of Phoebe’s baptism but with the sense of connection to the generations that had come before them. The church, its stones warm with the glow of the morning sun, had once again witnessed the continuation of life, faith, and community. And for Joseph, Louisa, and their children, the day was a beautiful reminder that their family was now forever part of something much larger, bound by faith, love, and tradition.

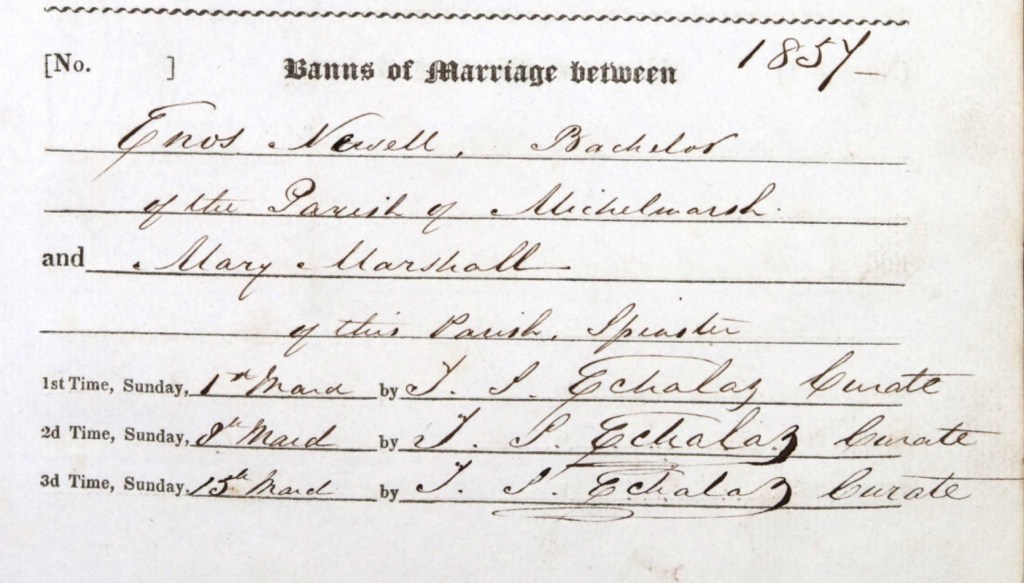

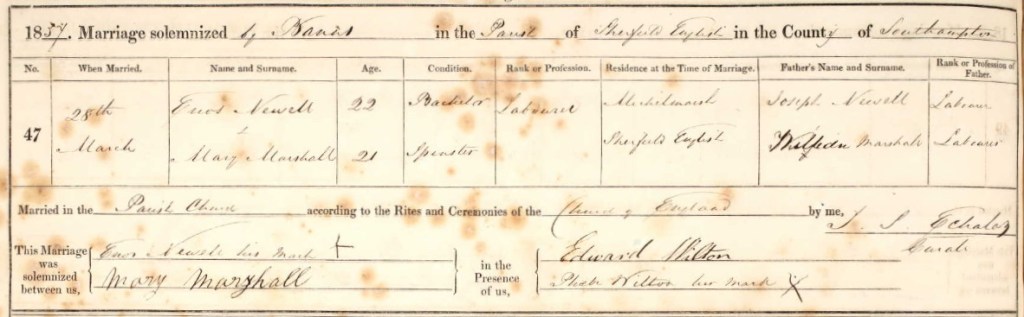

On a warm summer’s day, Saturday the 28th day of June, 1834, the village of Michelmersh was alive with the soft hum of rural life. The air was thick with the scent of fresh hay, and the buzzing of bees filled the fields that stretched beyond Joseph and Louisa’s home. It was a season of growth, both in the land and in their lives, as they were about to welcome another child into their fold. Joseph, now 29, and Louisa, 30, had already seen the births of their first few children, Joseph, Emma, and Phoebe, but this day marked the arrival of their son, Enos Newell.

Though the exact location of Enos’s birth cannot be pinpointed with certainty, the census records and his baptism offer us glimpses into his early years. His baptism states that the family was residing in Michelmersh, which suggests that the child was likely born there. The world outside, with its blooming wildflowers and the steady rhythm of the village, would have been full of promise for Joseph, Louisa, and their growing family. Yet inside their humble home, the quiet joy of a newborn’s first cries would have filled the air, as Joseph, holding his son, experienced that indescribable feeling of fatherhood once again, a love that grew with each child.

Joseph, already a seasoned father, must have felt the weight and beauty of the moment. He had worked hard alongside his father as a labourer, and now, with Louisa by his side, they were raising a family in the village he had known all his life. Their home, though small, was filled with the sounds of life, the laughter of older children, the soft cooing of the newborn Enos, and the steady rhythm of daily chores. As he held Enos in his arms for the first time, Joseph’s heart swelled with pride, knowing that his son would grow up in the same close-knit community, tied to the same traditions of hard work, faith, and family that had shaped Joseph’s own life.

Though the census records provide some mixed details about Enos's birth, they tell the story of a child growing up in a family that moved between Michelmersh, Sherfield English, and Awbridge. The 1841 census places Enos’s birth in Hampshire, with the family residing in Awbridge Hamlet. The 1851 census lists him as born in Sherfield English, while the 1861 and 1871 records show his birth in Michelmersh. The 1881 and 1891 censuses also place him in Awbridge. These inconsistencies are likely due to the fluidity of rural life at the time, families moved often, and records were not always precise, but they do paint a picture of a child who grew up in the heart of Hampshire, surrounded by family and the land that Joseph knew so well.

As the years went by, Enos became a part of Joseph’s growing legacy, a son who would carry forward the name Newell and the values of his father. Joseph’s life was shaped by his family, by the seasons that dictated their work, and by the love he shared with Louisa. Each child born into that home, including Enos, brought a new layer of meaning to Joseph’s life. With every laugh, every cry, and every moment spent as a father, Joseph’s heart grew fuller, his life richer.

Joseph must have looked at his son Enos, so small and fragile in those early days, and felt the weight of his own history. He had come from humble beginnings, worked hard with his own hands, and now he was raising children who would continue to build upon that foundation. It was a quiet joy, one that could only be felt in the stillness of a father’s heart as he held his newborn son. For Joseph, Enos’s birth was another chapter in the story of his life, a life deeply tied to the land, to his family, and to the simple but profound joy of seeing his children grow and flourish.

Under the warm, golden glow of the summer sun, Sunday the 20th day of July, 1834, felt like a day of profound significance in the life of Joseph. The fields around his home in Michelmersh were lush with the fullness of the season, the gentle hum of life in the village echoing the deep sense of growth and renewal in his own family. That morning, Joseph, along with his wife Louisa, their children Joseph, Emma, Phoebe and Enos, and their closest family and friends, made their way together to Saint Leonard’s Church in Sherfield English. The journey, though familiar, was one filled with the weight of anticipation, the baptism of their youngest son, Enos, was to take place that day.

As the family gathered in the cool stone church, the quiet reverence of the space seemed to envelop them. The walls of Saint Leonard’s Church, worn and ancient, had witnessed countless milestones, births, marriages, and baptisms of the families in the village for generations. Now, it was Joseph and Louisa’s turn to bring their son into the fold of the community.

The air was thick with the smell of old wood, incense, and the weight of centuries of faith as the ceremony began. C. H. Hodgson, the Vicar of the Cathedral, Sarum, presided over the service with calm dignity, his voice ringing clearly through the church. Joseph, his heart swelling with pride and tenderness, watched as the vicar took Enos in his arms, holding him gently over the baptismal font. The soft splash of water against Enos’s forehead marked the beginning of his spiritual journey.

For Joseph, it was a moment of deep emotion. He had known the weight of hard work, of labouring long hours in the fields, but here, in the quiet of the church, with his newborn son in the arms of the vicar, Joseph felt the immense weight of love, love for his family, for the new life that Enos represented, and for the quiet promise that this child, like the generations before him, would be carried through life by faith, family, and the community they had built together.

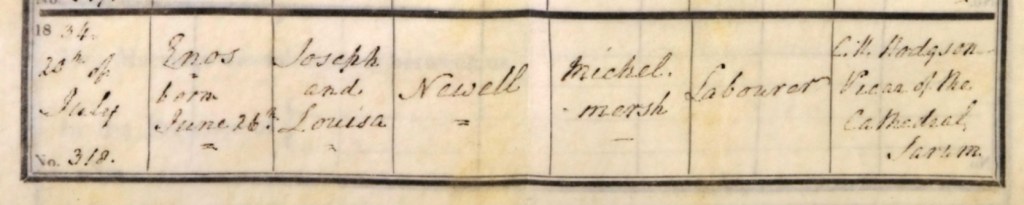

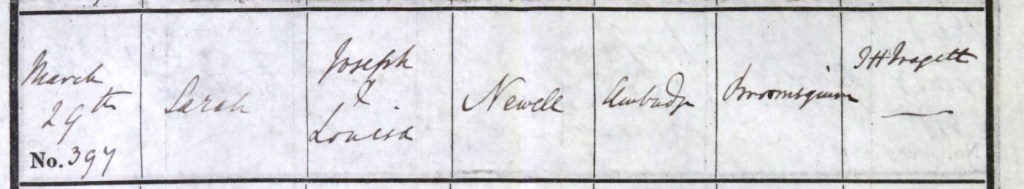

After the service and baptism, Joseph and Louisa, along with their loved ones, must have felt a deep sense of peace. The day had been marked by joy, a new chapter in their lives as parents, and a continuation of the legacy that had been built over generations. The vicar, after the service, took great care in recording Enos’s baptism in the parish register. In his neat hand, he filled in the details:

"1834 20th July No 318, Enos, Born June 26th, Joseph and Louisa, Newell, Michelmersh, Labourer."

The vicar signed his name, C. H. Hodgson, Vicar of the Cathedral, Sarum, a permanent record of the day Enos was welcomed into the Christian faith and the heart of the community.

As Joseph looked down at his son Enos, he must have felt a quiet pride. His life, though shaped by the rhythms of hard work, was now also defined by moments of grace, like the one he had just witnessed. Enos’s baptism was a milestone not just for the child, but for Joseph himself, a reminder that amid the toil of life, there were moments of joy, of family, and of love that bound them all together. As they made their way home from the church, Joseph knew that this day would live on in his heart forever, a moment that connected the past, the present, and the future of the Newell family.

In 1836, as the winter winds blew cold and the grey sky hung heavy over the village fields of Awbridge, Hampshire, Joseph Newell’s beloved wife Louisa had just given birth for the fifth time. Their third daughter, Mary Ann Newell, had arrived, and the air in their cozy home was filled with the sweet sound of a newborn’s cry. Joseph, Louisa, and their other children gathered around the tiny bundle with wonder, marveling at the new life that had joined their family. Despite the grey mist rolling over the fields and the chill in the air, warmth filled the cottage, where the fire in the grate crackled cheerfully, a pot of stew simmered on the stove, and the smell of fresh bread teasingly filled the room, making their stomachs growl in anticipation.

Winter may have been long and the days short, but spirits were high in the Newell household. Joseph and Louisa, though no strangers to the hardships of life, found joy in these small moments of happiness. The children, wide-eyed and curious, looked over their new sister, excited by the addition to their growing family. The warmth of love and contentment surrounded them, and for that moment, the struggles of life seemed far away. In the quiet of their home, it was easy to forget the cold winds outside and the challenges life often threw at them. Inside, they were rich with love, family, and a sense of togetherness that could not be measured by anything more than the happiness in their hearts.

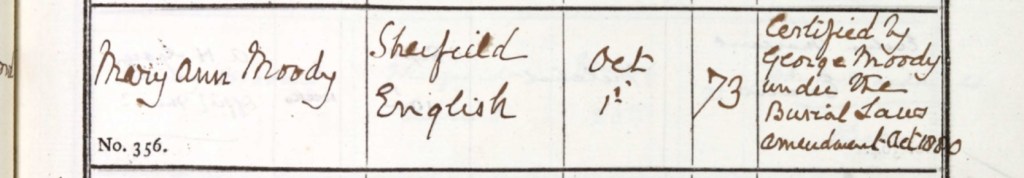

Although the exact date and location of Mary Ann’s birth remain a mystery, the census records provide us with a rough idea of when and where she was born. The 1841 census lists her birth year as 1836 in Hampshire, while the 1851 census places her birth year as 1837 in Sherfield English. The 1881 census marks her as being born in 1837 in Awbridge, and the 1891 census shows her birth year as 1839 in Michelmersh. While these dates and locations vary slightly, they tell the story of a child who grew up in the heart of Hampshire, surrounded by the love and care of her family.

For Joseph, Mary Ann’s birth was another moment of joy in a life filled with both challenges and blessings. Each child was a reminder of the enduring strength of his family and the love that held them all together. And as the winter winds howled outside their home in Awbridge, Joseph knew that no matter the struggles they faced, the warmth of his family would always be their greatest comfort.

Valentine's Day, celebrated annually on February 14th, is traditionally a day devoted to love and affection. Its origins trace back to ancient Rome, where mid-February was marked by the festival of Lupercalia, a fertility celebration that welcomed the coming of spring and involved various rituals meant to ensure health and fertility. Over time, the Christian church adapted these festivities, giving rise to St. Valentine’s Day, named after a third-century Roman saint. According to legend, St. Valentine performed weddings for soldiers forbidden to marry and ministered to Christians who were persecuted under the Roman Empire.

By the Middle Ages, Valentine’s Day became associated with romantic love, particularly after the 14th-century English poet Geoffrey Chaucer famously linked the day with the mating season of birds, further cementing the tradition of expressing affection and love. Over the centuries, the holiday evolved, with people exchanging gifts such as flowers, chocolates, and handwritten valentines. Today, Valentine's Day is celebrated worldwide and has become an essential cultural and commercial occasion dedicated to love, romance, and appreciation.

For the Newell family, Sunday, the 14th day of February, 1836, was a special Valentine’s Day indeed. While the world outside was filled with the symbols of love and affection, within the quiet, humble walls of the parish church of Sherfield English, Joseph and Louisa celebrated a deeply personal milestone. On this day, their daughter, Mary Ann, was welcomed into the Christian faith through the sacrament of baptism. The Sunday service, which had already gathered the faithful for prayer and reflection, was marked by the soft reverence of the moment.

W. H. Tomlinson, the Officiating Minister, led the ceremony with solemn care and warmth, performing the sacred ritual as Joseph and Louisa looked on with pride and hope for their daughter’s future in the faith. The congregation, gathered in the familiar warmth of the old stone church, witnessed the sacred act, joining in the blessing of Mary Ann’s life as a new member of the Christian community.

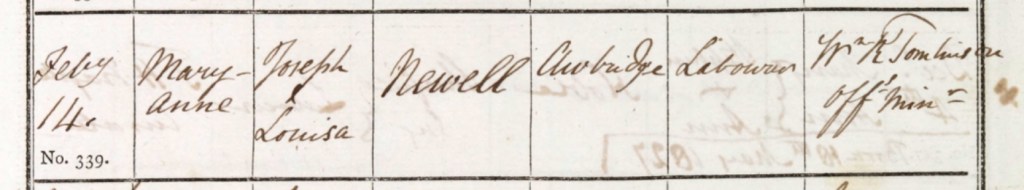

After the service, Reverend Tomlinson recorded the details of Mary Ann’s baptism in the parish register, his pen capturing the significance of the day. With steady hand, he wrote:

"14th February 1836, Mary Ann Newell, daughter of Joseph and Louisa Newell, labourer, Awbridge, was baptised at the parish church of Sherfield English in the county of Southampton."

Once all the details were recorded, he signed his name, completing the formal entry in the church’s long history of baptisms.

For Joseph and Louisa, the baptism of their daughter Mary Ann on Valentine’s Day was not just a religious event, it was a day that symbolised the love and care they held for their growing family. As much as the day was about faith and tradition, it was also a reflection of their deep connection to one another and to the community that supported them. It was, in its own way, a celebration of love, not just the romantic love marked by flowers and chocolates, but the deep, enduring love of family, faith, and the shared joy of welcoming new life into the world.

In the spring of 1838, Joseph watched his sister, Rhoda, (also spelled Roda) a young spinster from the parish of All Saints, Southampton, stand at the threshold of a new chapter in her life. It was a time of change, not only for Rhoda but for Joseph as well, who had always shared a special bond with her. Rhoda, though quietly reserved and humble, had always been a pillar of strength within their family. Her soft smile and steady presence had been a constant, and now, as she prepared to marry James Kemish, a bachelor from the nearby parish of East Wellow, Joseph couldn't help but feel a swell of emotion. This was not just a milestone for Rhoda, it was a family moment, a turning point in the shared journey of their lives.

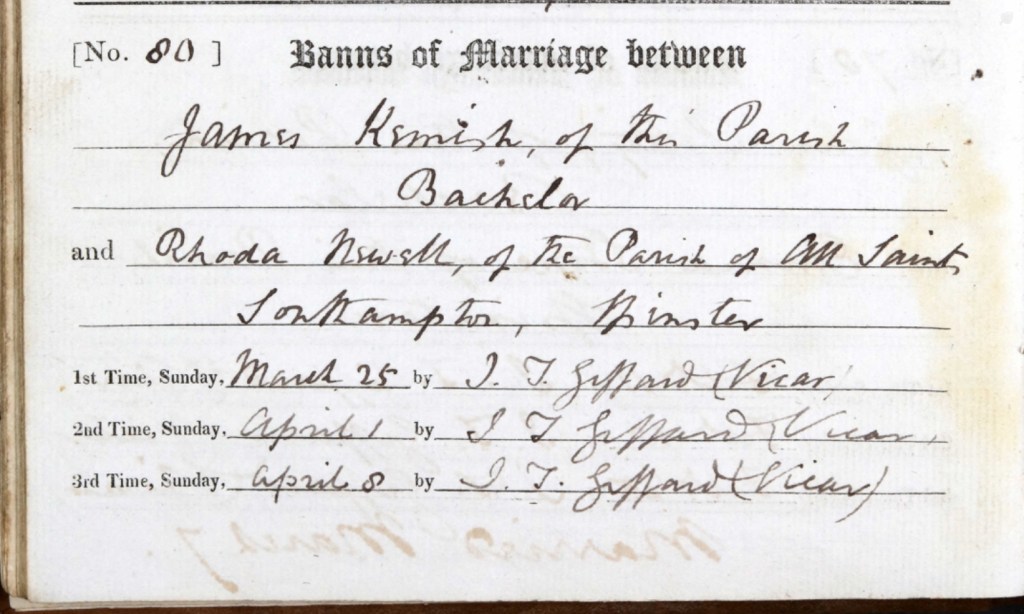

The news of Rhoda’s forthcoming marriage was formally announced through the reading of banns, a long-standing tradition in the Church of England that would bind her and James in the sacred commitment of marriage. The banns were read aloud in church over three consecutive Sundays: Sunday, March 25th; Sunday, April 1st; and Sunday, April 8th, 1838. As the vicar, J. T. Giffard, stood at the pulpit and called out their names, Joseph must have felt the weight of those moments, hearing his sister’s name linked with James’s in the ritual that had marked the beginning of countless marriages before hers. Each reading felt like a quiet drumbeat, bringing Rhoda closer to the altar, to the promise of a shared life with James, and to the forging of a new family.

Joseph could feel the significance of the banns, the rhythm of his sister’s life moving forward. Rhoda had always carried herself with grace and faith, and now, as the congregation gathered to hear the announcement of her intentions, Joseph knew that her journey toward marriage was not only a personal milestone but also a reflection of the quiet strength and unwavering faith she had always carried. It was as if, in those moments, Rhoda was stepping into a new chapter, not alone, but with the love and support of her family and the wider community.

The banns were recorded in the parish register, each announcement marking the sacred intent of Rhoda and James to be joined together. The entry read:

[No. 80] Banns of Marriage between James Kemish, of this Parish, Bachelor, and Rhoda Newell, of the Parish of All Saints, Southampton, Spinster

1st Time, Sunday, March 25, by J. T. Giffard, Vicar 2nd Time, Sunday, April 1, by J. T. Giffard, Vicar 3rd Time, Sunday, April 8, by J. T. Giffard, Vicar

As Joseph stood in the pews on those Sundays, hearing the words of the banns echo through the church, he must have been filled with a mixture of pride and bittersweet emotion. Rhoda, his dear sister, was about to embark on her own journey, one that would take her into the arms of a new family and a new life. Yet, in the quiet of those moments, Joseph found comfort in the knowledge that Rhoda's journey, though leading her to James, was also bound by the unspoken ties of love and faith that had always bound their family together.

For Joseph, this was a time of reflection, a time to acknowledge how the seasons of life brought change, but also how love and faith provided the foundation for these changes. Rhoda’s marriage would mark a new chapter, but it would also strengthen the bond they shared as siblings, a bond rooted in the faith of their upbringing, in the love of their parents, and in the quiet understanding that life, with all its changes, was always tethered to the warmth and strength of family.

As the banns were read and Rhoda moved closer to the altar, Joseph felt a profound sense of pride in his sister’s strength and grace, knowing that she was stepping into a future that was as full of promise as the spring that had arrived with her marriage. It was a future shaped by love, faith, and the unbreakable ties of family, and Joseph knew that this was only the beginning of a beautiful new chapter for Rhoda and for their family.

Saint Margaret's Church in East Wellow, Hampshire, is a beautiful and historic parish church that has stood as a central spiritual and community landmark for many centuries. Located in the picturesque surroundings of the Test Valley, the church is an integral part of East Wellow, a village with a rich history tied to the local agricultural community and its connections to the broader historical developments of Hampshire.

The history of Saint Margaret’s Church can be traced back to the 12th century, with the earliest known reference to the church appearing in the Domesday Book of 1086. The church was built during a time when many villages in England were establishing places of worship and community gathering, and it has since played a significant role in the religious and social life of the village. The church’s name, "Saint Margaret," likely refers to Saint Margaret of Antioch, a Christian martyr whose feast day is celebrated in June. Saint Margaret was revered in medieval Christian communities, particularly in England, where many churches were dedicated to saints who had strong associations with faith and protection.

Saint Margaret’s Church has seen several architectural modifications over the centuries, but much of the original Norman structure remains, particularly in the form of the church’s solid stone walls and simple, unpretentious design. The church was built in the Romanesque style, typical of early medieval churches, and it would have been a simple, functional building intended to serve the needs of the local population. Over time, as the church became a focal point for the growing community, various changes were made to accommodate the increasing number of parishioners and to reflect the evolving architectural tastes of the time.

During the 13th century, the church underwent its first major expansion, as many churches did during the medieval period. This expansion likely included the addition of a chancel and the extension of the nave, as well as the inclusion of larger windows to allow more light into the building. As was common in many rural churches, St. Margaret’s was at the heart of village life, providing not only a place for worship but also a space for social and community activities. During this time, the churchyard would have also served as the burial ground for local residents, with gravestones marking the lives of those who had contributed to the local community.

Over the centuries, the church continued to evolve, particularly during the Victorian era when many older churches were restored or rebuilt. In the 19th century, Saint Margaret’s Church underwent significant restoration work under the direction of Victorian architects who were dedicated to preserving medieval structures. During this time, the church was modernized with the addition of stained-glass windows, new pews, and other decorative features that reflected the Gothic Revival style that was popular during the period. The restoration also helped to maintain the integrity of the church’s structure, ensuring that it remained a functioning place of worship for generations to come.

One of the most notable features of Saint Margaret’s Church is its beautiful churchyard, which is the final resting place for many generations of Wellow residents. The churchyard is home to a variety of graves and memorials, some of which date back to the medieval period. The gravestones, many of which are carved with intricate symbols and inscriptions, provide insight into the lives of the people who lived in Wellow and the surrounding area over the centuries. The churchyard is not only a place of remembrance but also serves as a peaceful and tranquil area, surrounded by trees and greenery, where locals and visitors alike can reflect and appreciate the history of the village.

In addition to its religious functions, Saint Margaret’s Church also played an important role in the social life of East Wellow. Like many churches in rural England, Saint Margaret’s was the center for various community events, including festivals, fairs, and charitable activities. The church was a space where people came together to celebrate important events in the church calendar, such as Christmas, Easter, and harvest festivals. These occasions were important not only for their religious significance but also as social events where the community could gather and bond.

Saint Margaret’s Church has been a part of the local community for over 900 years, and it continues to be an active place of worship and community gathering. The church holds regular services, including Sunday worship, as well as special events like weddings, christenings, and funerals. It remains a beloved part of East Wellow, serving as a reminder of the village’s deep historical and spiritual roots. The church also hosts occasional concerts, events, and educational programs, continuing its role as a cultural and social center for the village.

As for rumors of hauntings or supernatural occurrences, like many historic churches, Saint Margaret’s Church has been the subject of local folklore and ghost stories. While there are no widely known or documented cases of hauntings, the church's long history, the age of its structure, and the quiet, serene atmosphere of the churchyard may naturally lead to tales of mysterious happenings or eerie experiences. Churches with such a long history often become part of local ghost lore, and their dark corners and ancient gravestones sometimes inspire imagination and stories passed down through generations.

As the vibrant spring flowers bloomed and the cuckoo sang its joyful song, Joseph stood at a quiet crossroads in his life, watching his beloved sister, Rhoda Newell, prepare to step into a new chapter of her own. At 27 years old, Rhoda was far from her roots in Awbridge, the village that had shaped their childhood and their lives. She was about to marry James Kemish, the love of her life, in a ceremony that would bind them together and forever change their paths.

It was Thursday, the 12th day of April, 1838, when Rhoda and James were married at All Saints Church in Southampton, Hampshire. For Joseph, this was a bittersweet moment. The church stood proud and timeless, a symbol of the enduring faith and tradition that had always been part of their lives. As Rhoda stood before the altar, Joseph must have felt a mixture of pride and sorrow, knowing that his sister was about to embark on a journey that would take her away from the home they had shared, from the fields of Awbridge, and into a new life with James.

James Kemish’s roots were firmly planted in the villages of Romsey Extra, where he had grown up. Residing in East Wellow, he was the son of James Kemish and Mary Kemish, formerly Drake. His life was steeped in the quiet traditions of rural Hampshire, where faith, hard work, and a deep connection to the land had shaped him. In marrying Rhoda, he was not just taking on a wife but was also joining the Newell family, a family that Joseph had watched grow, struggling together, celebrating together, and now witnessing Rhoda’s new chapter with a mixture of joy and a touch of sadness.

Joseph must have been flooded with memories as he watched his sister prepare for her wedding. The bond they shared, shaped by years of growing up together, was a deep and enduring one. He had been there through her childhood, her triumphs, and her challenges. And now, as Rhoda stood on the cusp of this new life, Joseph’s heart must have felt heavy. He would no longer see her as often, would no longer share the same close proximity to her laughter and companionship. Yet, in that moment, Joseph knew that Rhoda was stepping into a future filled with love and promise, guided by the same strength and grace that had always defined her.

The marriage ceremony itself, held in the grand old church, would have been a simple yet profound expression of love. James and Rhoda pledged themselves to one another, not just as husband and wife, but as two souls joined together, their futures forever intertwined. Rhoda’s life, once firmly rooted in Awbridge, was now bound to a new village, a new home, and a new family. Joseph watched as the vows were exchanged, knowing that this was a moment that marked a shift in their family’s story.

For Joseph, this wedding was more than just the union of two people, it was the beginning of a new era. Rhoda, the sister who had shared so much of his life, was now moving forward, carving out a future of her own with James. Yet in the bittersweetness of that moment, Joseph couldn’t help but feel immense pride for the woman Rhoda had become. She was strong, loving, and ready for this new chapter, and James was the one who would walk alongside her.

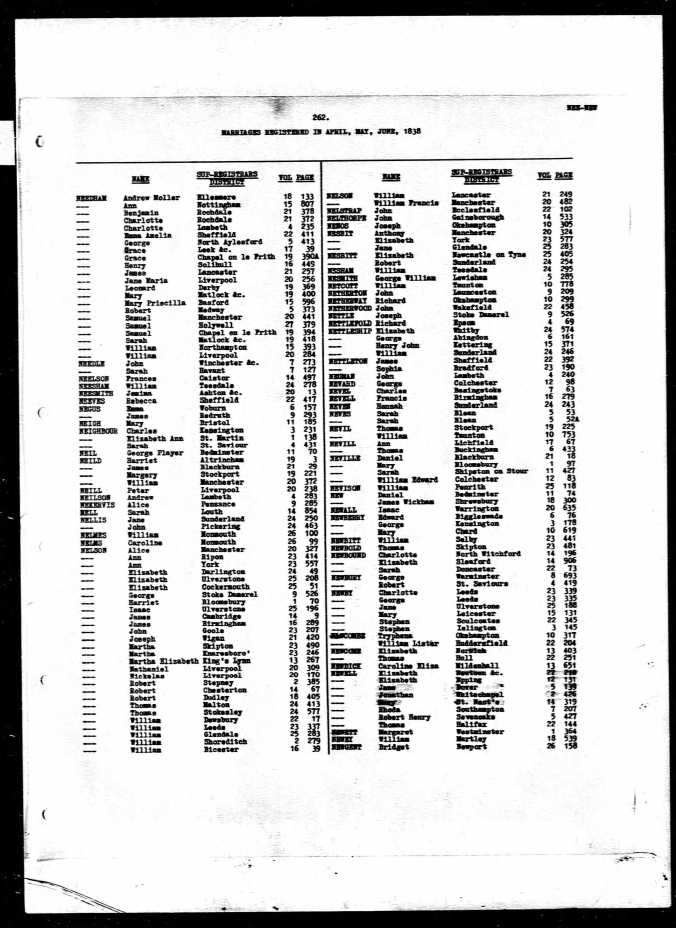

Unfortunately, due to the rising costs of family research subscriptions and certificates, I have had to make the difficult decision not to purchase the marriage certificates throughout Joseph’s life story. However, for those interested in exploring this further, the marriage certificate for Rhoda Newell and James Kemish can be ordered with the following GRO reference:

GRO Reference - Marriages Jun 1838, NEWELL, Rhoda and KEMISH, James. Southampton, Volume 7, Page 207.

As Joseph looked on that spring day, he knew that his sister’s marriage was not just the union of two people, but a symbol of the ever-changing nature of life itself. Love had taken Rhoda away from their family home in Awbridge, but Joseph knew that the bonds they shared,those of family, love, and the land,would remain with her wherever she went. The memory of that day would stay with Joseph, a reminder of the deep, unbreakable ties that family provides, and the bittersweet beauty of watching a loved one begin a new chapter, full of hope and promise.

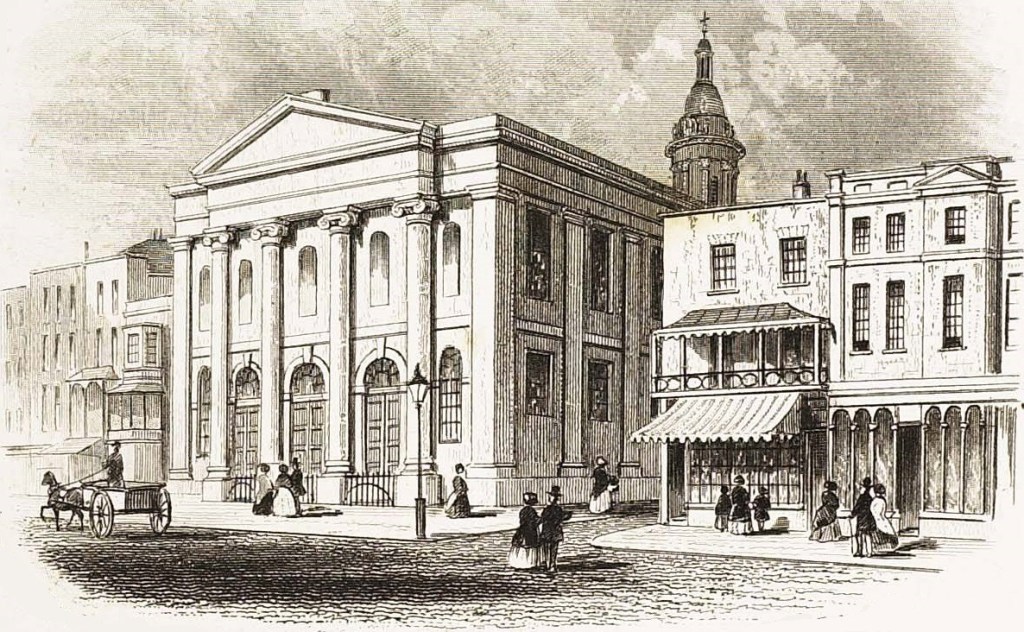

All Saints Church in Southampton, Hampshire, is one of the city's significant landmarks, with a rich history that dates back to medieval times. Situated in the heart of Southampton, this church has been a focal point for both religious and social life, adapting and evolving over the centuries to meet the needs of the community.

The history of All Saints Church can be traced back to the 13th century, although there are indications that a church had existed on the site even earlier. The exact date of its founding is unclear, but the first documented mention of the church appears in records from the late medieval period. The church was likely established as part of the town’s growing population and its increasing importance as a port town. Southampton, during this time, was a bustling port, and the church played an important role in the spiritual life of both the local population and the sailors who frequented the town.

The church was originally a parish church, serving the growing community of Southampton. Its location in the center of the town, close to the bustling harbor, made it an important gathering place for worship, as well as a space for significant social and community events. During the medieval period, churches like All Saints were not only places of religious worship but also served as community hubs, where people came together for local meetings, to hear news, and to mark key life events like baptisms, marriages, and funerals.

Architecturally, All Saints Church is a fine example of Gothic design, though it has been altered and restored over the centuries. The building has a simple yet striking design, featuring pointed arches, ribbed vaults, and large windows. Over time, the church underwent several extensions and modifications, particularly in the 14th and 15th centuries, as Southampton’s population grew. These changes helped accommodate the increasing number of people attending services and participating in the life of the church. The tower of the church, added later, became a defining feature of its skyline, offering a view of the city and the harbor.

During the late 16th and 17th centuries, the church, like many others in England, was affected by the social and political upheavals of the time, particularly the English Civil War and the subsequent rise of Puritanism. Many churches across England suffered from neglect, disrepair, and even desecration during these periods. All Saints Church, however, managed to survive through these difficult times, though it likely saw a reduction in the number of parishioners attending services during periods of conflict and religious tension.

In the 19th century, All Saints Church underwent a significant restoration, following the Victorian-era passion for restoring medieval buildings. This period saw the church receiving new stained-glass windows, and many of the internal features were updated to reflect the Gothic Revival style that was popular at the time. The restoration efforts helped to preserve the church’s historical integrity while also meeting the needs of a growing and more diverse population.

The church’s location in the heart of Southampton made it an important place for civic life, and it has seen its fair share of historical events. Over the years, the church has hosted memorials, concerts, and public gatherings, becoming a symbol of the town’s resilience and cultural identity. One of the key moments in the church’s history occurred during World War II. During the Blitz, Southampton, as a major port city, was heavily bombed, and All Saints Church was damaged by bombings in 1940. The church, like many others in the city, suffered from the destruction brought by air raids. However, the church was later restored, and its resilience during the war became a symbol of the city’s endurance through hardship.

Today, All Saints Church continues to serve as an active place of worship and community engagement. It is one of the oldest buildings in Southampton, offering a space for reflection and connection in the heart of a city that has grown and evolved significantly since its medieval roots. The church remains a popular venue for weddings, baptisms, and other religious ceremonies, while also hosting cultural events, concerts, and exhibitions. Its striking architecture and historical significance make it an important landmark in Southampton, a reminder of the city’s long and varied history.

In addition to its religious functions, All Saints Church is a place of historical interest. Its proximity to the bustling city center and the harbor means that it continues to be a part of the daily life of Southampton, and it attracts visitors and tourists who are drawn to its architectural beauty and historical significance. The churchyard, with its centuries-old gravestones, serves as a reminder of the generations of people who have lived, worked, and died in Southampton, contributing to the rich history of the city.

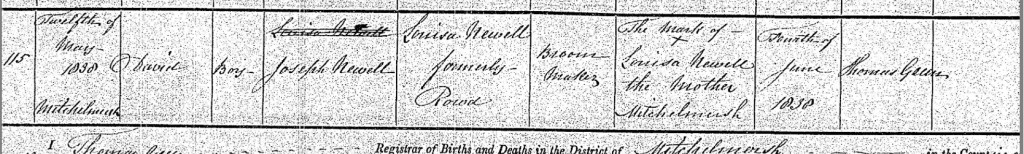

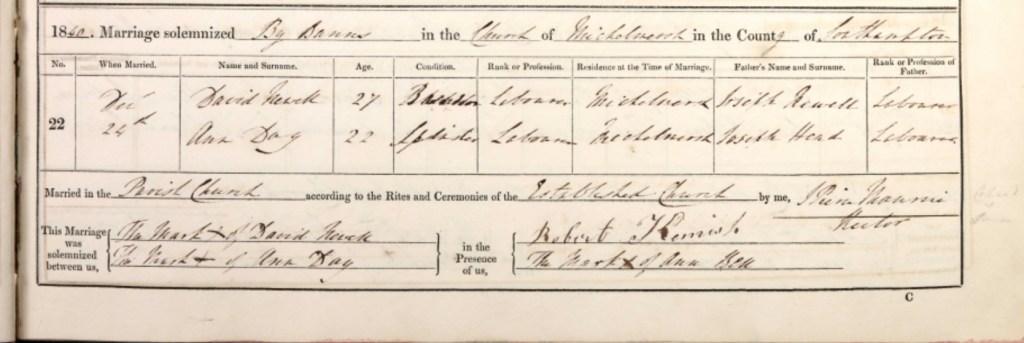

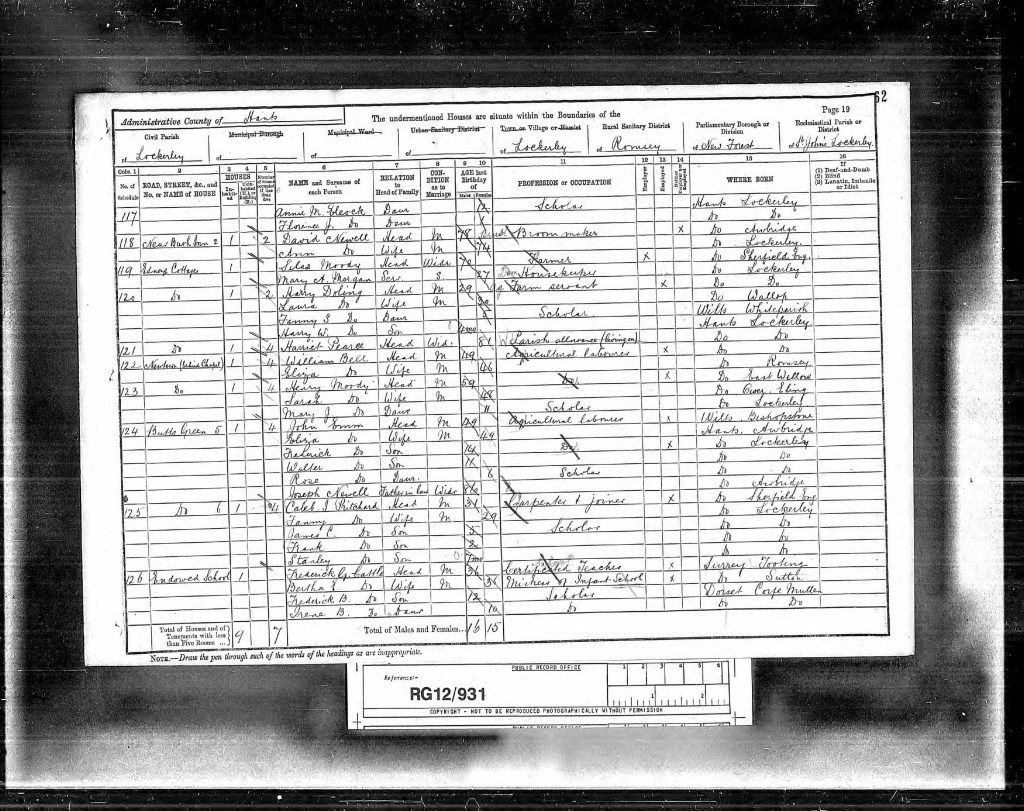

Spring had finally arrived, bringing with it the warmth and renewal that seemed to breathe new life into everything around Joseph and Louisa. The air was filled with the sweet scent of blooming flowers, and the gentle flutter of butterflies dancing in the spring breeze added to the beauty of the season. It was during this time of renewal that Joseph and Louisa welcomed their son, David Newell, into the world on Saturday, the 12th day of May, 1838, in their home in Michelmersh, Hampshire.

David's arrival was a moment of joy for the family, a new life added to their growing circle. The sounds of a newborn’s cry echoed in their home, mixing with the laughter of their other children, and filling the house with the promise of a future full of love and hope. Joseph, who had always worked hard as a broom maker, looked at his newborn son with pride and gratitude. Louisa, exhausted yet overjoyed, held David close, knowing that this little one would be another cherished part of their family’s story.

As was the custom, Louisa traveled to Romsey to register David’s birth on Monday the 4th day of June, 1838. The journey, though not long, would have given Louisa a moment to reflect on the significance of the day, the birth of her son and the continuation of the Newell family. At the local registrar’s office, Thomas Green was in attendance to document David’s birth. He recorded the important details carefully in the birth register, noting that David Newell, a boy, was born to Joseph Newell, a broom maker, and Louisa Newell, formerly Rowd, on the 12th of May, 1838, in Michelmersh.

With the formalities complete, Louisa signed the document with a mark, a simple “X” as was often the case for many women of the time who were not able to write their names. Yet, in that humble mark, Louisa’s commitment to her family and her love for her new son were clear.

The registration of David’s birth was a quiet, formal moment, but it carried the weight of something much deeper, a new chapter in the Newell family’s life. For Joseph and Louisa, it was a reminder of the continuity of life, of the love that had brought them together and the new life they had created. David’s birth was another link in the chain of their family’s story, and as they moved forward, Joseph knew that this spring, this season of new beginnings, would always hold a special place in his heart. The memory of David’s arrival, like the butterflies in the garden, would stay with him forever, a symbol of the joy and renewal that family brings.

The sky was a perfect blue, the early summer sun warming the earth, casting a gentle light over the fields and the quiet village of Sherfield English. On Sunday, the 10th day of June, 1838, a tender and sacred moment unfolded as David Newell, the young son of Joseph and Louisa, was brought forward for baptism at Saint Leonard’s Church. The air was still and full of reverence, as the Newell family, residents of Awbridge in the parish of Michelmersh, gathered in the historic church for the occasion. Their hearts were full, not just with pride in their son, but with the deep connection they felt to the land and the traditions that had shaped their lives for generations.

Joseph, a humble labourer, and his wife Louisa stood side by side, their hands clasped in quiet devotion, their hearts united in the love for their child. In the soft glow of the church, the atmosphere was sacred, filled with the gentle echo of whispered prayers and the sound of soft footsteps across the stone floors. Reverend J. Davies, the vicar of the parish, stood before them, ready to perform the sacred rite of baptism. His voice, calm and steady, filled the church as he began the ceremony, welcoming young David into the Christian faith with words that had been spoken for centuries in churches like this one. It was a moment rich with history, full of hope for the future, and grounded in the simple, enduring faith that had carried families like theirs through time.

As David was gently held in his mother’s arms and the water was poured over his forehead, Joseph and Louisa could feel the weight of the moment, their son now part of a larger family, a family bound not just by blood but by shared faith, love, and tradition. The quiet joy of the ceremony seemed to fill the space, wrapping the Newell family in warmth and peace.

After the service, Reverend J. Davies carefully filled in the baptism register with precise handwriting, ensuring that the details of the day would be recorded for posterity. He wrote:

"10th June 1838, David Newell, son of Joseph Newell, a labourer, and Louisa Newell of Awbridge, was baptised in the parish of Sherfield English, in the county of Southampton."

With a final flourish, he signed his name at the bottom of the page, completing the record of the sacred event.

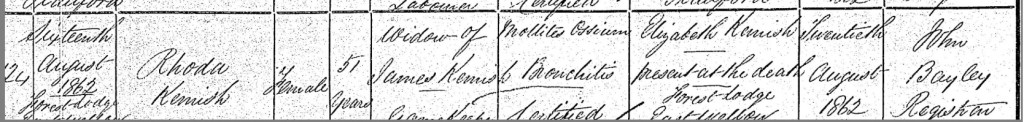

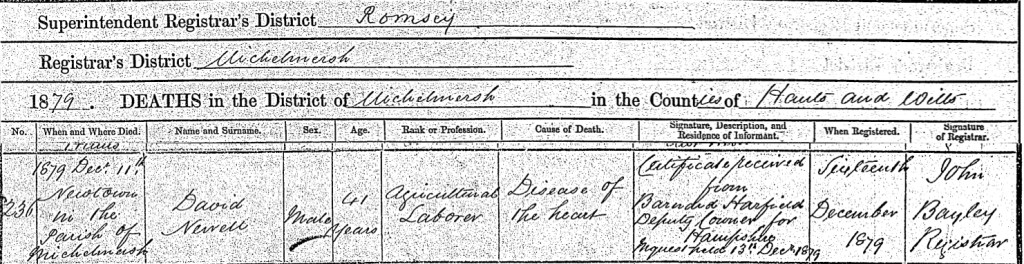

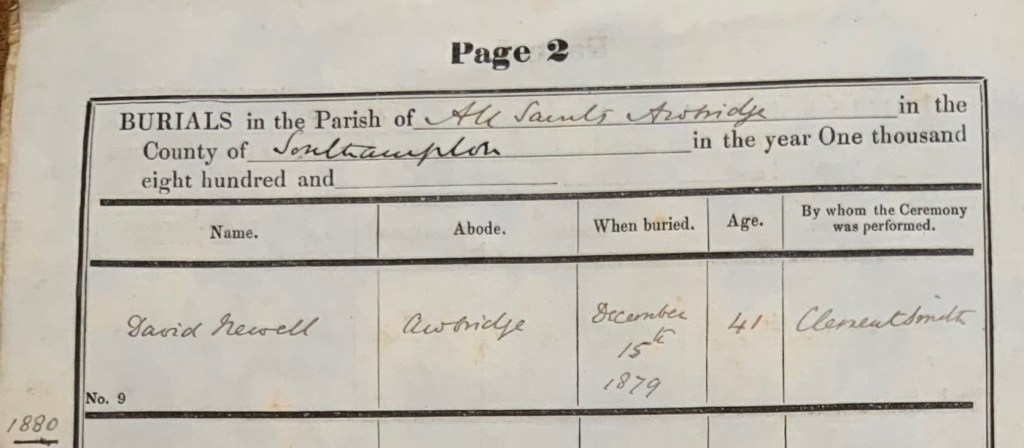

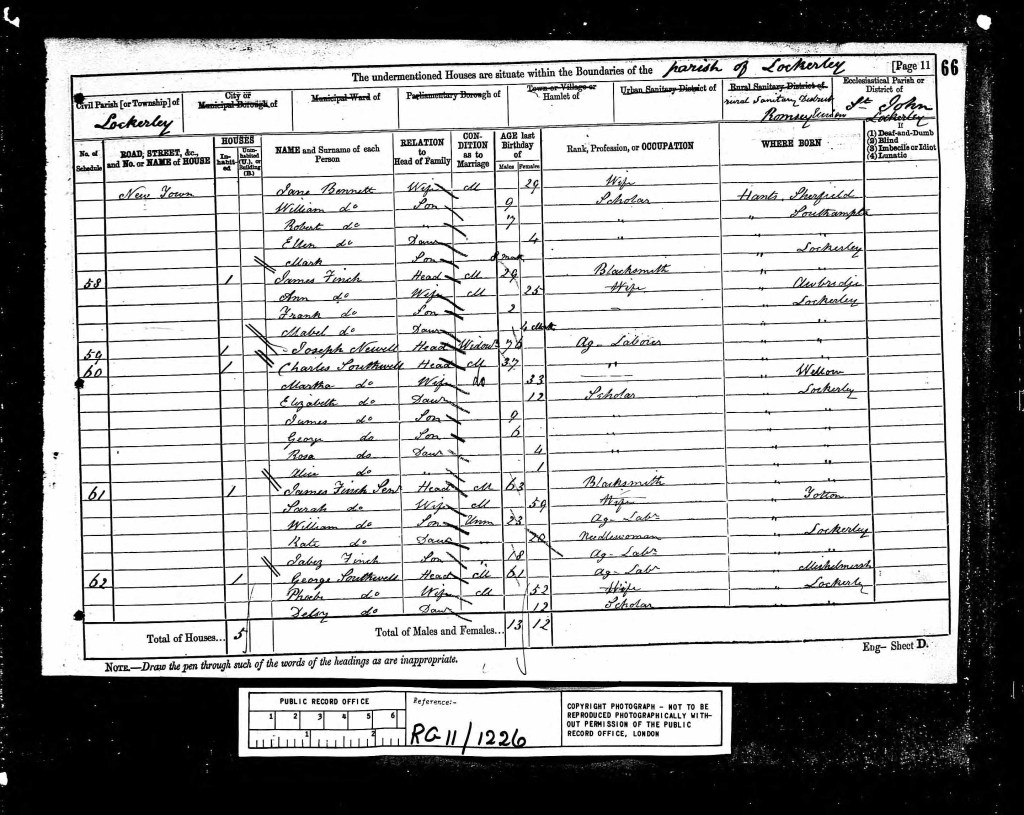

As the Newells left the church, the sun continued to shine brightly, casting long shadows across the village as they made their way home. The ceremony had been simple, but it was filled with meaning, a moment that would remain in their hearts for years to come. For Joseph and Louisa, it was not just the beginning of David’s spiritual journey, but the continuation of their own. In that quiet church, surrounded by family, tradition, and faith, they had marked the start of a new chapter for their son, one that was rooted in the same values that had shaped their lives and would continue to shape the lives of their children for generations to come.