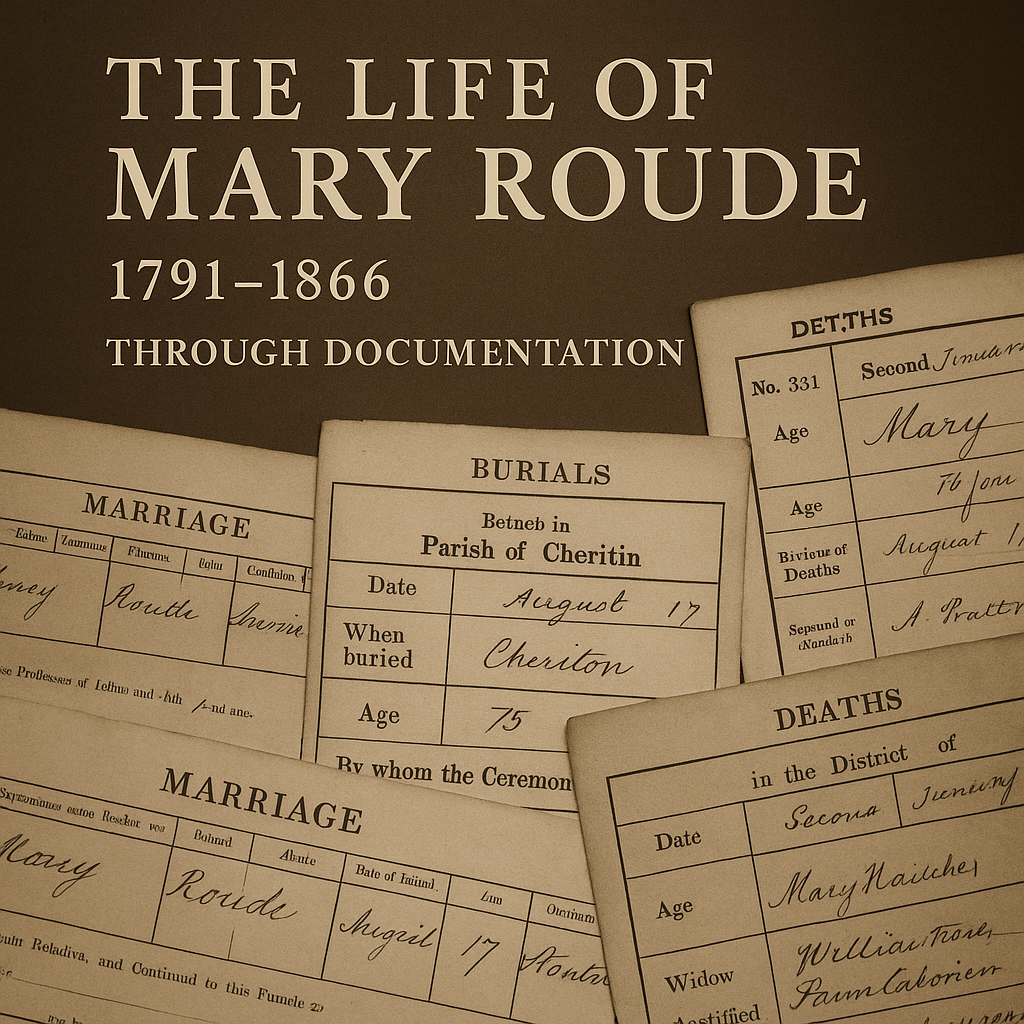

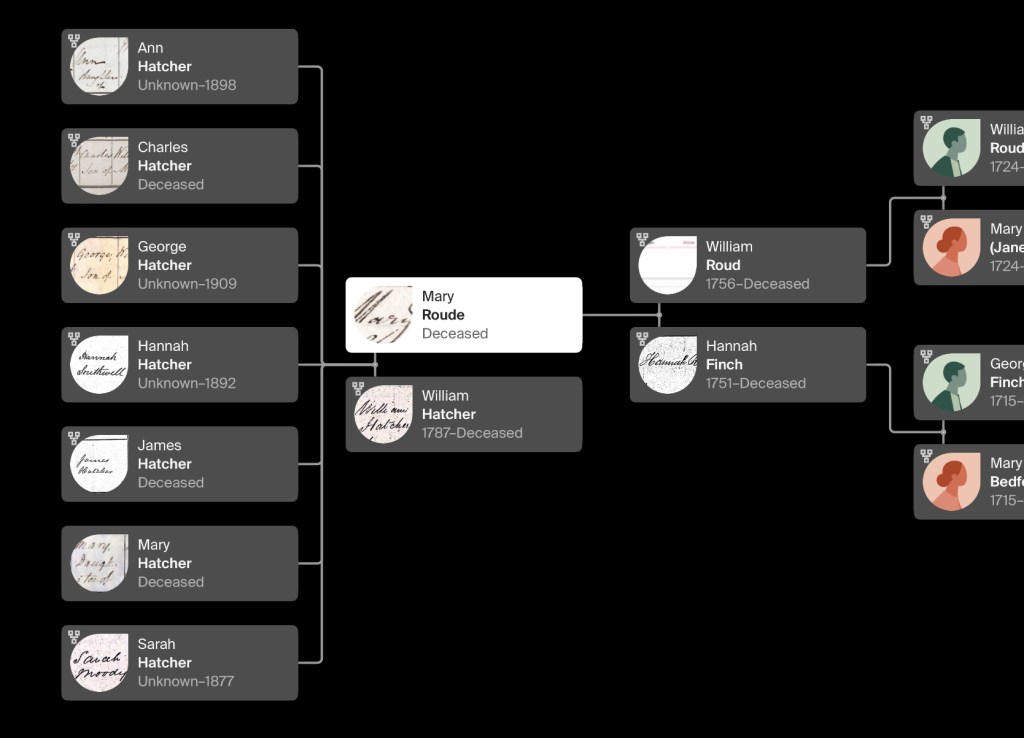

Tracing the threads of our ancestors’ lives is an emotional journey that intertwines history, memories, and the realisation of how little we truly know about those who came before us. My journey to understand my fourth-great-grandmother, Mary Roude (sometimes spelled Roud), has been one such pursuit, one that has both challenged me and deepened my appreciation for the resilience and lives of those who shaped my family tree.

Born around 1791 in the quaint village of Sherfield English, Hampshire, England, Mary’s life spans a time of great change and upheaval. It’s astonishing to imagine how she navigated a world that was far different from ours, one that lacked the conveniences and records we often take for granted today. Mary’s story, much like that of many from her time, was built on oral histories, and the sparse parish records that have survived. In an era before the census and civil registration of births, marriages, and deaths, piecing together the details of Mary’s life is a painstaking process, one that reminds us of how precious and fragile these connections can be.

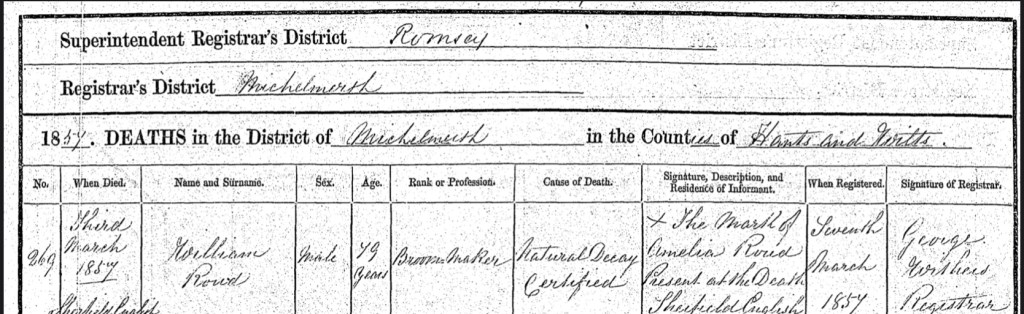

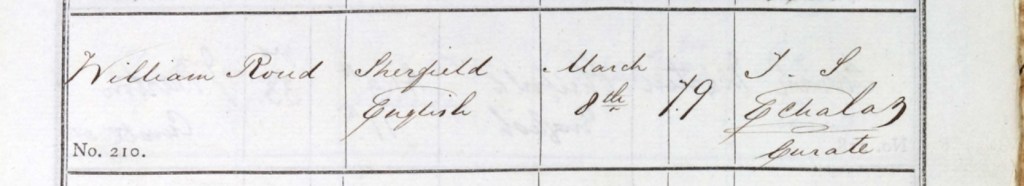

Her parents, William Roud and Hannah Finch, are names that echo faintly through time, preserved only by those few surviving records, and yet, the mystery of her story draws me in deeper with each passing year. How can one person’s life be so difficult to reconstruct from such limited resources? This is where the art and struggle of family history research comes alive, the thrill of discovery mixed with the heartache of pieces that don’t quite fit or have been lost to the ravages of time.

I hope to share Mary’s life, as best as I have been able to piece it together, drawing on the scant evidence and rich imagination that family historians use to bring the past to life. It is a labor of love and respect for the incredible woman who helped lay the foundation for the family I know today. As we navigate the challenges of genealogy, we also remember the importance of understanding and preserving the stories of those who came before us, even when their voices have long since been silenced. Their lives, no matter how incomplete our knowledge of them may be, continue to influence and inspire us, and the search for their stories is a journey that will never truly end.

Welcome back to the year 1791, Sherfield English, Hampshire, England. It is a year that stands at the crossroads of change, caught between the lingering influence of the 18th century and the dawning of new political, social, and industrial revolutions that would shape the future. In this year, Sherfield English, a small, rural village nestled in the county of Hampshire, was a quiet place, far removed from the bustling cities that had begun to modernize. Yet, in the broader context, it was a time of great transformation, both in England and across the world.

At the helm of the British monarchy in 1791 was King George III, whose reign had been marked by political turbulence and personal struggles with mental illness. His condition was beginning to worsen, and although he would remain king until his death in 1820, much of the power of the monarchy had already been ceded to his prime minister, William Pitt the Younger. Pitt, a brilliant and reform-minded politician, had been in office since 1783, and his leadership would have a significant impact on Britain’s direction during the final years of the 18th century.

In Parliament, the political scene was highly charged. The French Revolution had begun in 1789, and the radical shifts happening across the Channel were causing alarm in Britain. The establishment was deeply conservative, and the idea of revolutionary change, particularly in the form of democracy and equality, was viewed with suspicion. There was a marked divide between the Whigs, who leaned toward reform, and the Tories, who were more conservative in their approach to governance. This tension was mirrored in debates over Britain’s own social inequalities, as well as its imperial ambitions abroad.

For the common people, life in 1791 was starkly divided between the wealthy elite and the working poor. The rich, often living in the larger cities or grand estates in the countryside, enjoyed luxurious homes, fine clothing, and abundant food. They had access to the best education and enjoyed leisure activities such as hunting, theater, and art. Their lives were defined by privilege, but also by a sense of duty and responsibility toward the empire and society.

In contrast, the working class and the poor faced lives of hardship. The Industrial Revolution was starting to take root, but it hadn’t yet reached its full force, and the rural population still relied heavily on agriculture. For those living in the countryside, like those in Sherfield English, life was often centered around farming, manual labor, and tight-knit communities. However, conditions were difficult. Work was physically demanding, with long hours, little pay, and few rights. For the poorest, survival depended on the harvest and the support of family or parish. Many of the working class had little in terms of material wealth or opportunity, and the poor lived in squalid conditions.

Fashion in 1791 was characterized by elaborate and highly structured styles. The upper classes wore fine fabrics such as silks, velvets, and fine wool, with men often sporting coats with wide collars, waistcoats, and breeches. Women wore dresses with long flowing skirts, often featuring high waistlines (empire line), and intricate detailing such as lace and ribbons. However, for the poor and working classes, clothing was far more utilitarian. Garments were made from coarser fabrics and were often hand-me-downs or repaired and repurposed many times over.

Transportation in 1791 was slow and cumbersome. The roads were often in poor condition, and travel was usually by horseback, carriage, or foot. The wealthy could afford to travel long distances, but for the majority of people, travel beyond the local area was a rare and sometimes expensive event. The invention of the steam engine was still in its early stages, with the first railways not becoming commonplace until decades later.

Housing for the majority was modest. In villages like Sherfield English, people lived in small cottages, often with thatched roofs, made of timber or brick. These homes were simple, consisting of a few rooms, often with a large hearth for cooking and heating. The wealthier landowners or gentry could afford larger, more comfortable homes, with multiple rooms and finer furnishings, but even they would not have the modern comforts we take for granted today. Heating was typically done by coal or wood fires, with the cold, damp winters making it difficult to stay warm, especially in rural areas. Lighting was limited to oil lamps, candles, or tallow lights, which provided little illumination and were often smoky and dim.

Hygiene and sanitation in 1791 were rudimentary at best. For most people, washing was a rare occurrence, and the concept of personal hygiene was very different from today’s standards. Bathing was infrequent, and many people relied on communal water sources or streams for their daily needs. The lack of proper sanitation meant that waste disposal was often a problem, with open cesspits or waste being dumped in the streets, leading to the spread of disease. Diseases such as cholera, typhus, and dysentery were common in urban areas, but even in rural villages, the close quarters of family life and the lack of effective sanitation meant that health could deteriorate quickly.

Food in 1791 was largely based on what could be grown or raised locally. For the wealthy, meals were elaborate affairs, featuring meats, pies, puddings, and an array of vegetables. Spices and imported goods were a luxury. For the poor, meals were much simpler, often consisting of bread, cheese, and a small amount of meat or vegetables, depending on what could be afforded. Food preservation was an issue, and many people relied on salted or dried food to see them through the winter months.

Entertainment in 1791 was largely centered around social gatherings, music, and outdoor activities. The rich attended theaters, concerts, and balls, while the working class enjoyed simpler pleasures, such as festivals, fairs, or gatherings in taverns. For most people, however, leisure time was limited, and many spent their days working hard just to survive.

Religion was an important part of life in 1791, with the Church of England being the dominant faith. For many, religion was a source of comfort and community, with church services providing a sense of belonging and spiritual guidance. However, there were also tensions within the religious landscape, with dissenting groups, such as the Methodists, gaining followers. These tensions would later come to a head as calls for reform spread across the country.

The atmosphere in 1791 was one of uncertainty and change. The echoes of the American Revolution were still felt, and the French Revolution had just begun, shaking the foundations of European monarchies. In England, political debates over reform were intensifying, and there was a growing awareness of the need for change, especially in the face of the changing economic and social landscape brought about by industrialization. The air was thick with whispers of revolution, as many began to question the status quo, while others feared the chaos of upheaval.

In Sherfield English, life might have felt more removed from the events unfolding on the world stage, but the ripples of change were still being felt. The world around Mary Roude was one of simplicity and hardship, but it was also one of community, faith, and resilience. The challenges of survival in a world without modern comforts were great, but the bonds of family and tradition helped to anchor people, even as the winds of history began to shift around them.

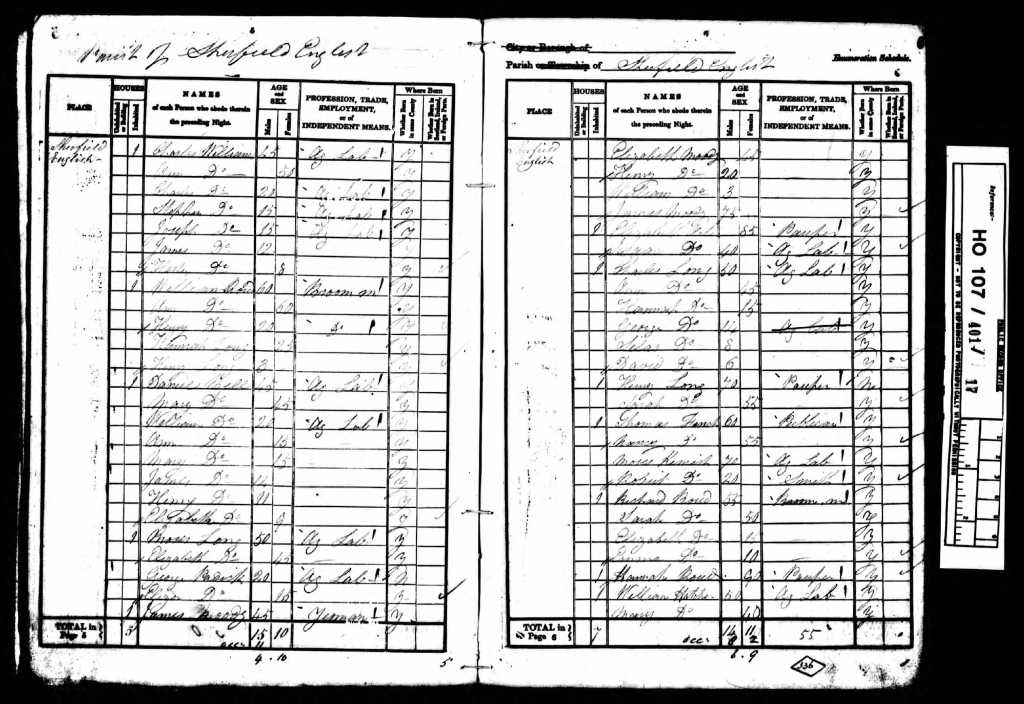

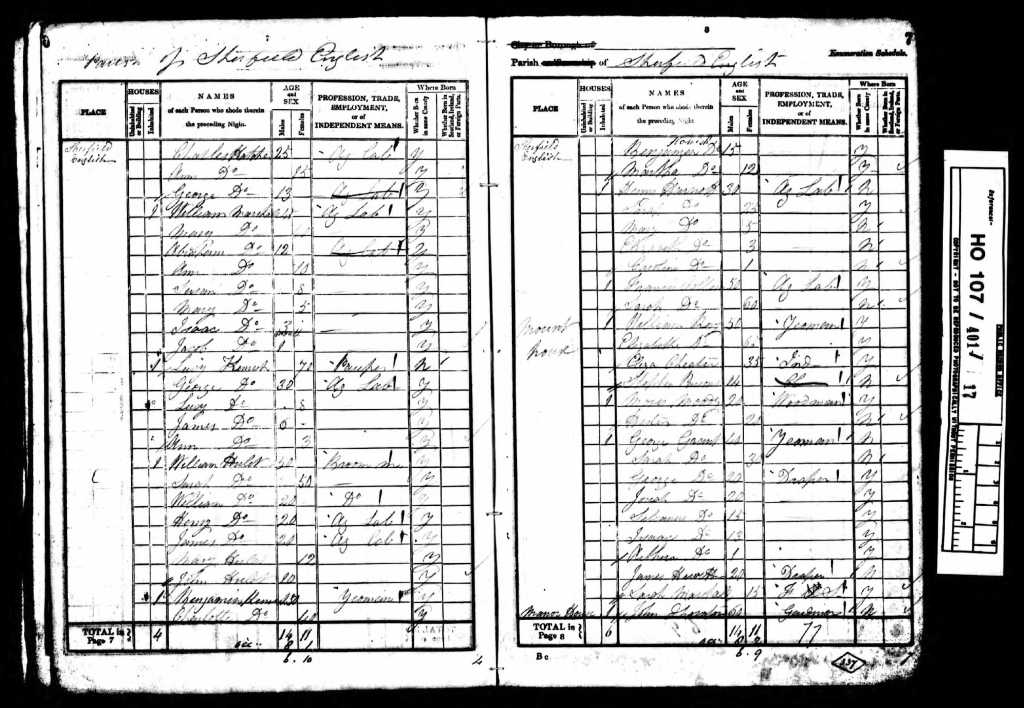

Mary Roude was born in 1791 in the peaceful village of Sherfield English, Hampshire, to William and Hannah Roud. Her father, William, was approximately 34 years old at the time of her birth, while her mother, Hannah, was around 39. Though the exact date of Mary’s birth remains a mystery, it is suggested by census records that she was born around 1791 in Sherfield English. These records, though offering a glimpse into Mary’s life, only provide us with rough approximations. The 1841 census, for instance, places her birth year as approximately 1801, while the 1851 and 1861 censuses confirm the year as 1791, but always with a slight degree of uncertainty.

Mary was the youngest of five siblings. Her three brothers, William, born before the 7th day of September, 1777, James, born before the 13th day of April, 1780, and Richard, born before the 22nd day of May, 1785, were older than she, growing up in a world shaped by the same traditions and challenges that would define Mary’s own life. Her only sister, Hannah, was born before the 8th day of September, 1782, completing a family of siblings who shared the same quiet rural upbringing in Hampshire. Together, they would have formed a close-knit family, bound by the ties of siblinghood and the steady rhythm of life in the countryside, even as each one embarked on their own path in the world.

Yet, tragedy and struck the Roud family when Mary’s brother James passed away in early April 1781. He was laid to rest at Saint Leonard’s Churchyard in Sherfield English, on Friday, the 13th day of April 1781. It must have been a heart-wrenching loss for the family. The grief of such a young life lost would have left a lasting imprint on Mary’s childhood, as she grew up in the shadow of that sorrow. The church where James was laid to rest, the original church at the heart of Sherfield English, would have been a place that marked the passage of time for Mary and her family, a place of both solemnity and faith, as they honored their loved ones and prayed for their futures.

Though the history of Mary’s family is rooted in these bare dates and names, the essence of her life exists in the connections between them, the love and responsibility between parents and children, the shared duties of family, and the unspoken strength of rural life in a time when records were few and far between. It is in these small, personal details that we begin to understand the richness of Mary Roude’s story.

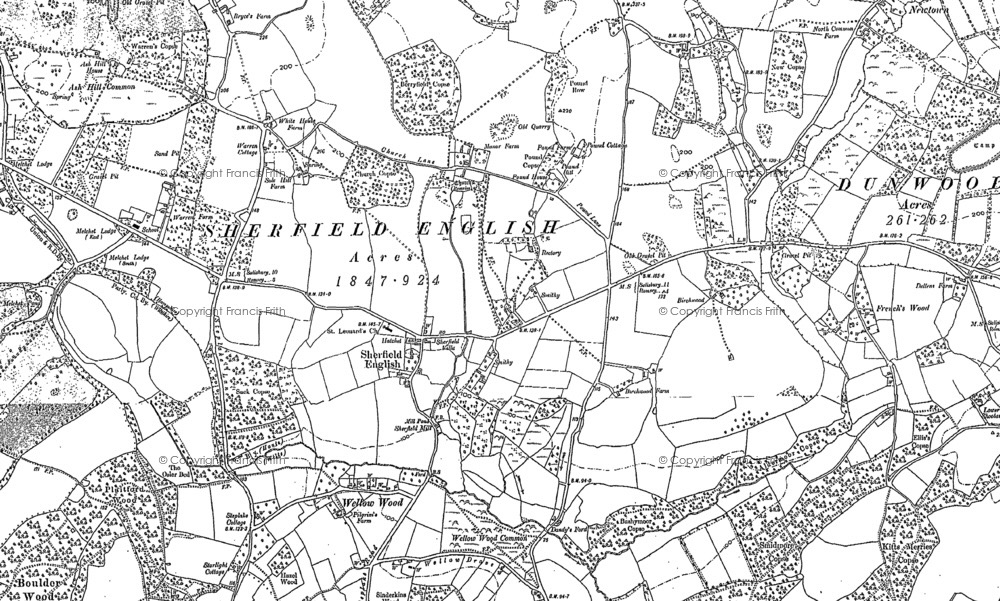

Sherfield English is a small village located in the Test Valley district of Hampshire, England. It lies just a few miles northwest of Romsey and is set within the picturesque Hampshire countryside, surrounded by farmland and natural beauty. The village has a rich history that spans several centuries and is deeply connected to the rural landscape of southern England.

The name "Sherfield" likely comes from Old English, where "scear" refers to a slope or hill and "feld" means open land or field, suggesting the village was established in an area with a prominent geographical feature. The addition of "English" to the name occurred later, distinguishing it from other similarly named places following the Norman Conquest of 1066.

Sherfield English's development can be traced back to the medieval period, when it was primarily a farming community. The village's history reflects the broader agricultural heritage of Hampshire. It grew slowly but steadily, with most residents engaged in farming and agricultural work, a typical occupation for rural England at the time. The village’s centerpiece was the parish church, St. Leonard’s Church, which has served as a spiritual and social center for the community for many centuries. The church, with its origins dating back to the 12th century, is a key focal point of the village and reflects its long religious history.

In the 19th century, Sherfield English, like many rural areas, began to see changes brought on by population growth and the rise of industrialization. While the village remained largely agricultural, the expansion of transportation networks, particularly railways, brought new opportunities for trade and communication. This period also saw the construction of several cottages and houses in the village, leading to an increase in population.

The architecture of Sherfield English retains much of its historic character, with a mix of old cottages and larger homes. Despite the growth of nearby towns, the village has managed to maintain its rural charm and peaceful atmosphere, remaining a quiet, residential area. Its location, just a short distance from Romsey, offers a blend of tranquility and accessibility.

St. Leonard’s Church, at the heart of Sherfield English, has been integral to the community since its establishment. It was built in the 12th century, with subsequent renovations and expansions reflecting changing architectural styles and the evolving needs of the congregation. The church is dedicated to St. Leonard, the patron saint of prisoners and the mentally ill, and its role in the community has been central to the village's spiritual life. The churchyard around St. Leonard’s Church contains numerous gravestones, many of which date back several centuries, and the church remains an active site for worship, weddings, and other community events.

Sherfield English is also steeped in local folklore, and like many historic English villages, it has its share of ghost stories and rumored hauntings. St. Leonard’s Church, with its long history, is often the focal point of these tales. Some locals have reported strange occurrences in and around the churchyard, such as the sensation of being watched or hearing unexplained sounds like distant footsteps or murmurs. There are also stories about church bells ringing at night without anyone in the building to ring them, adding to the eerie reputation of the church. While these accounts remain largely anecdotal, they contribute to the village’s sense of mystery and intrigue.

In addition to the church, other old buildings in the village, such as historic houses and inns, are also said to be associated with ghostly activity. Some residents have claimed to see shadowy figures in certain rooms or have experienced cold drafts in areas of these older properties. These stories, while not officially documented, persist as part of the village's folklore and add to the character of Sherfield English.

Today, Sherfield English remains a picturesque and peaceful village, with a small but active community. The surrounding countryside offers opportunities for outdoor activities such as hiking, cycling, and birdwatching, making it an attractive location for those seeking a rural lifestyle while still being close to Romsey and other nearby towns. The village's historical charm, combined with its natural beauty and connection to local traditions, continues to make it a unique place to live and visit.

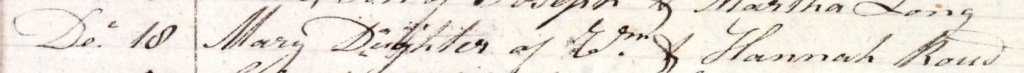

On the crisp, winter morning of Sunday, the 18th day of December 18th, 1791, a small but significant moment in Mary's life took place in the humble yet sacred space of Saint Leonard’s Church, Sherfield English, Hampshire. The chill of the season would have hung in the air as Mary’s parents, William and Hannah Roud, walked the short distance to the church, a place that would become woven into the fabric of her life. Their daughter, only a few months old, was about to undergo the Christian sacrament of baptism, a rite that held deep spiritual significance in an age where religion anchored the lives of even the smallest village communities.

As Mary was cradled in her mother’s arms, William and Hannah would have entered the simple stone church, its pews likely filled with a few local villagers who, like the Roud family, found solace in the rituals that connected them to something far greater than the fleeting struggles of their daily lives. The flickering light of candles would have cast a soft glow upon the stone walls, and the low murmur of quiet prayers might have drifted through the room, filling the air with a sense of reverence. The church, with its centuries-old foundations, was a place of continuity, where generations before Mary had come to seek the blessing of the divine, and where, in this moment, she, too, would begin her own sacred journey.

The baptism itself, as it would have been in 1791, was a solemn and communal act. The curate, William Watson, would have been standing near the altar, dressed in the traditional vestments of his office, perhaps a white alb or a black cassock, his face calm and focused on the ritual at hand. Baptism in this period was performed by sprinkling or pouring water over the child’s head, a practice that connected Mary to the ancient traditions of the Church. This simple yet profound act symbolized her entrance into the Christian faith and the community of believers.

With her parents standing by, Mary would have been held by her mother, as her father stood close, each of them offering prayers of thanksgiving and hope for their child’s future. The curate would have dipped his fingers into the font of holy water, drawing the water in his hand and gently sprinkling it over Mary’s head as he recited the sacred words: "I baptize thee in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit." The church, though small, would have resonated with the weight of these words, as the community shared in this important moment. The water, cool and pure, would have marked Mary as a member of the church and the village, a child of God, and a part of the long lineage of her ancestors who had come before her.

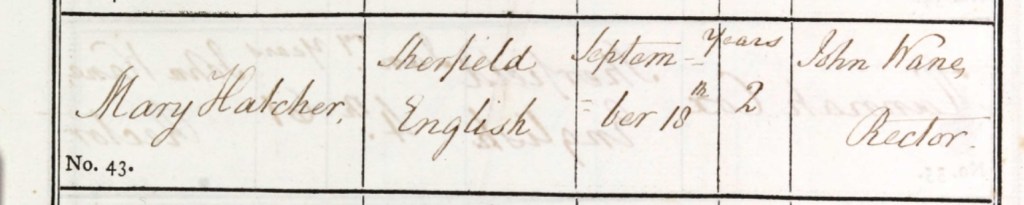

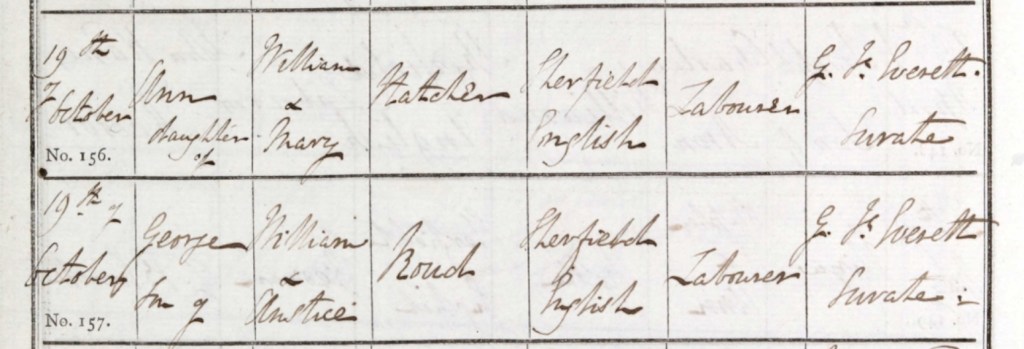

Curate William Watson, with careful attention to detail, recorded the event in the parish register, his handwriting precise and neat in the way only those with a devotion to their work would manage. Under the heading of "Baptisms, Marriages, and Burials," Watson wrote, "Dec 18th Mary daughter of Wm. and Hannah Roud." This simple entry, composed in 1791, would remain a vital piece of history, passed down through the ages to eventually connect Mary to the generations that followed her. For her parents, this record would stand as proof of their daughter's place in the eyes of both God and the community, a mark of continuity in a world where records were few, and each written word had an enduring weight.

After the baptism, Mary’s parents would have stood together in quiet reflection, holding their daughter close, perhaps offering their own silent prayers for her health and happiness. The congregation, if present, would have gently offered their blessings, knowing that this was not just a ritual, but a profound affirmation of life and faith. The bonds of the Roud family, already strong through the shared experience of parenthood and the loss of Mary’s older brother James just months before, were now further solidified by this sacrament, a symbol of faith, family, and the enduring presence of divine grace in their lives.

The church, its stone walls a silent witness to so many such moments, stood as a backdrop to Mary’s story. Saint Leonard’s Church, where her brother James had been laid to rest in the spring of 1781, would continue to be a place of solace for Mary and her family in the years to come, a reminder of the spiritual and familial connections that tied them to one another and to the village they called home.

In the years that followed, as Mary grew, she would carry with her the significance of that baptismal day, the water that had touched her forehead, the prayers that had been said over her, and the unspoken promises made by her parents, to protect and guide her in a world that would one day be hers to navigate. It was a day like no other, yet like countless other baptisms that had been performed in the same church over the centuries, marking the beginning of Mary’s journey in the world, grounded in faith, surrounded by family, and rooted in a community that would be her home.

The name Mary has a long and significant history, deeply rooted in various cultures and religious traditions. It has remained one of the most widely used names across different countries and time periods, often associated with purity, grace, and reverence.

The name Mary is derived from the Hebrew name Miryam (מִרְיָם), though the exact meaning of the name is uncertain. Some scholars suggest it means "sea of bitterness," "rebelliousness," or "wished-for child," while others believe it may be related to the Egyptian name Mery, meaning "beloved" or "love."

The name Mary is most famously associated with the Virgin Mary, the mother of Jesus in Christian tradition. The Virgin Mary's role in Christianity has made the name Mary one of the most revered names, especially in Catholicism, where the Virgin Mary is considered the ultimate symbol of purity, motherhood, and compassion. The name has been used in various forms in different languages, including Maria in Spanish and Italian, Marie in French, and Miriam in Hebrew.

In the Christian Bible, Mary is often depicted as a humble and obedient figure, and her role in the New Testament has greatly influenced the name’s popularity in Christian communities. Over the centuries, the name Mary has become synonymous with virtuous womanhood, devotion, and maternal love.

In addition to its religious significance, the name Mary has been widely used in both royal and common circles. It was a popular name among European royalty, with numerous queens and princesses bearing the name. Queen Mary I of England, also known as "Bloody Mary," and her granddaughter, Queen Mary II of England, are two notable examples. Mary Stuart, better known as Mary, Queen of Scots, also contributed to the name's historical prominence.

The name Mary remained extremely popular throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries, particularly in English-speaking countries. In the United States, it was the most popular name for girls for many decades, especially in the early 1900s. During this period, it was seen as a classic, timeless name, and it was commonly chosen for its association with religious and cultural ideals of womanhood.

Over time, the popularity of the name Mary has waned, though it still retains a strong presence and continues to be used across many cultures. In the 20th century, variations of the name such as Maria and Marie became more common, but Mary remains a timeless and beloved name in both Christian and secular contexts.

The surname Roud, often spelled as Roude, has its origins in England, and like many surnames, its history is rooted in the cultural and social dynamics of the medieval period. The surname is relatively rare and likely evolved from a combination of geographical, occupational, or descriptive factors.

The surname Roud is believed to be of Anglo-Saxon or Old French origin, with several theories regarding its development. One possibility is that it may have derived from a geographical location, such as a town or settlement named "Roud" or "Roude," which would have been based on a place name in early medieval England. This is a common source of many surnames, as people often adopted the name of the place where they lived or were originally from.

Another theory is that the surname Roud could be derived from a Middle English word "roud" or "rood," meaning a cross or a structure resembling a cross. This word would have been used to describe a place near a religious monument, such as a cross at a crossroads or a small church, often found in rural areas. If this is the case, the surname may have originated as a name for someone who lived near such a landmark or worked as a caretaker of it.

The variation in spelling, such as "Roude," could reflect changes in regional dialects and spelling conventions over time, as English orthography was not standardized until much later. The shift in vowel sounds and spelling was common as surnames were passed down orally and written differently depending on the scribe or the region.

As with many surnames, the name Roud would have been passed down through generations, and early bearers of the surname would have likely lived in rural communities or towns where such names were adopted based on occupation, location, or personal characteristics. The surname would have been relatively uncommon and might have been concentrated in specific areas, particularly in the southern or southwestern parts of England, though this can vary depending on migration patterns and historical records.

In terms of historical records, variations of the surname can be found in some early parish registers and tax records, but the surname Roud, or Roude, has not been widely documented in historical nobility or aristocracy. This suggests that the name was likely borne by common folk, particularly in rural communities, rather than by people of noble birth. It is possible that individuals with the surname Roud may have been farmers, laborers, or tradespeople, though there is no specific evidence linking the name to any particular occupation.

The name's presence in the historical record, however, is a reminder of the social structure of medieval and early modern England, where surnames often denoted a person’s origins, occupation, or relationship to a specific place. Over time, people with the surname Roud may have migrated, and the name may have spread across different regions of England and beyond, particularly during the periods of population movement and the expansion of the British Empire.

In modern times, the surname Roud or Roude is quite rare. However, it continues to be found among descendants who carry on the legacy of their ancestors, even if the surname has undergone slight variations in spelling or pronunciation. As with many older surnames, the historical context of Roud is shaped by its connection to the land and the people who lived on it.

Saint Leonard’s Church in Sherfield English, Hampshire, has a rich history that stretches back over many centuries. The church has been a central part of the village’s religious and community life, and its history reflects the broader development of the area from medieval times to the present. The original Saint Leonard’s Church is believed to have been built in the early medieval period, likely during the Norman era, around the 12th century. The church would have been a simple structure, typical of rural churches of the time. As was common with churches in small villages, it was likely constructed with local materials such as stone and timber, with a simple design reflecting the needs of the local community. The church was dedicated to Saint Leonard, a popular saint during the medieval period who was often invoked for protection and for his association with prisoners and captives. Saint Leonard’s cult was widespread across England, and many churches were named in his honor. The original church at Sherfield English served as a focal point for the small agricultural community, providing a place for worship, social gatherings, and important life events such as baptisms, marriages, and funerals. The church would have also been a place where the villagers came together for communal activities, and it played an essential role in maintaining the spiritual and social fabric of the community. Over time, the church likely underwent several modifications and additions, particularly in the 14th and 15th centuries, as the village expanded and the needs of the local population grew. These changes were likely driven by the growing wealth of the parish as the agricultural economy strengthened. In the 19th century, however, the old church began to show signs of wear and was no longer able to adequately serve the growing population of Sherfield English. By the early 1800s, the church building had become dilapidated and was deemed inadequate for the needs of the parish. At this point, the decision was made to construct a new church to better serve the community. The new Saint Leonard’s Church was built in 1840, a year that saw the completion of many church restoration projects across rural England, driven in part by the Victorian era’s focus on reviving medieval architectural styles. The new church was built on a site adjacent to the old church, though some sources suggest that it may have been on the same footprint or nearby. The architect responsible for the design of the new church was likely influenced by the popular Gothic Revival style of the time, which was characterized by pointed arches, stained-glass windows, and spires. The new church was intended to accommodate the needs of the growing population of Sherfield English, and it was designed to be larger and more architecturally impressive than its predecessor. The construction of the new church was part of a broader trend of church building and restoration during the Victorian period, a time when many rural churches were being rebuilt or restored to reflect the prosperity of the period. The old Saint Leonard’s Church, after the new one was completed, was demolished, as was often the case with churches that were deemed structurally unsound or inadequate for modern use. It is common for older church buildings to be torn down when a new structure is built, particularly if the old building no longer meets the needs of the local population or has fallen into disrepair. It is likely that the materials from the old church were repurposed for the new construction, as was the custom at the time, though no records have definitively confirmed this. Today, Saint Leonard’s Church stands as a beautiful example of Victorian church architecture, with its stained-glass windows, pointed arches, and graceful tower. The church continues to serve the community, offering regular worship services, community events, and providing a space for reflection and connection. The church is also known for its picturesque setting within the village, surrounded by well-kept churchyards and the rolling countryside of Hampshire. The new church, while a product of the 19th century, retains the essence of the old church’s purpose to serve as a spiritual hub for the village of Sherfield English.

Saint Leonard Church

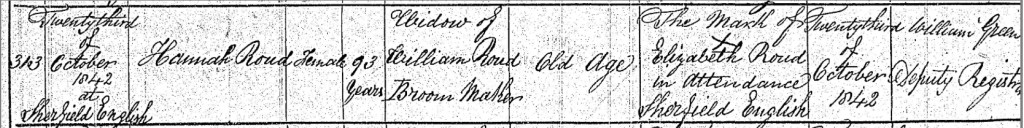

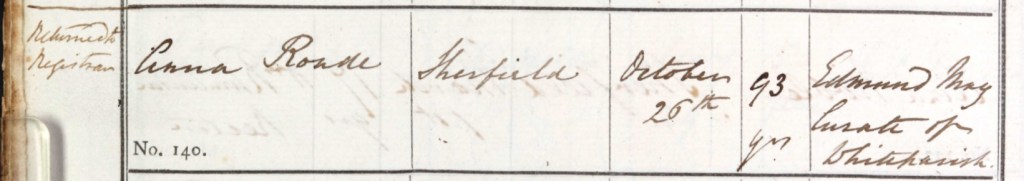

When Mary was barely even a year old, tragedy struck her family. In the early days of December 1792, her father, William Roud, passed away. The pain of losing a father at such a young age is something that Mary could never have fully understood, yet the loss would have shaped her life in ways that would echo through the years. William, at just 35 years old, left behind his wife, Hannah, and their five children, each one now forced to navigate the world without the steady presence of their father.

It is likely that William’s death took place in the family home in Sherfield English, a simple cottage where life had once been filled with the warmth of family and the comforting sounds of daily routines. The Roud household would have been a place of work and togetherness, where William’s presence was a guiding force. His untimely death, however, would have left a painful void, a loss that Mary, as the youngest, would never have had the chance to fully comprehend, but which would reverberate through the lives of her mother and siblings.

For Hannah, the grief of losing her husband would have been overwhelming. In an era where women had limited resources and the challenges of raising children often fell squarely on their shoulders, the death of William likely left her with a heavy burden. She would have been left to care for Mary and her older children alone, with the weight of her responsibilities compounded by the loss of the man who had been her partner in life and work. The community around them in Sherfield English, though tightly-knit and supportive, could not fill the hole left by such a personal tragedy.

In the weeks and months that followed, Mary’s life, though still so young and fragile, would have been irrevocably changed. The loss of her father would not only have shaped her early years, but it would also have set the tone for her understanding of family, of love, and of the resilience needed to carry on in the face of hardship. Her mother, despite the grief, would have had to find strength in order to provide for her children, and the deep well of love she had for them would have become the anchor that held them all together through the storm of loss.

For Mary, this early loss became part of the foundation of her life. It was a tragedy she would never have understood in her infancy, but one that would follow her in the subtle, unspoken ways that grief and memory shape a person over the years. Though she would grow up without the steady presence of her father, his memory, and the life he had built with her mother, would continue to guide the family even after he was gone. And as Mary’s own life unfolded, this loss would remain a shadow that added depth to the woman she would become, strong, resilient, and, above all, deeply rooted in the enduring ties of family.

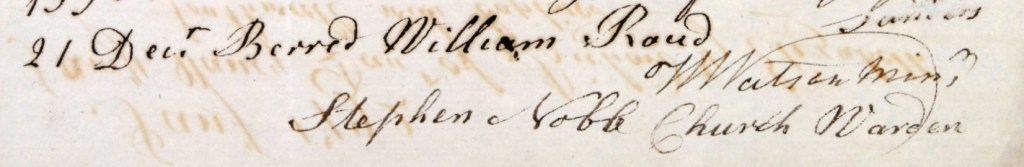

On Friday, the 21st day of December, 1792, the village of Sherfield English gathered once again at Saint Leonard’s Churchyard to lay to rest one of their own. William Roud, Mary’s father, passed away earlier that year, leaving behind a grieving family who would forever carry his memory. At the age of 35, William’s life was cut short, and as winter’s chill settled over the landscape, the Roud family found themselves facing yet another sorrowful goodbye.

William was laid to rest at Saint Leonard’s Churchyard, the same sacred ground where his son, James, had been buried over a decade earlier in 1781. The churchyard, steeped in quiet reverence, became a place where the Roud family’s grief would be bound together, each grave marking not just a loss, but the passage of time, the unfolding of their family’s history, and the enduring presence of those they loved.

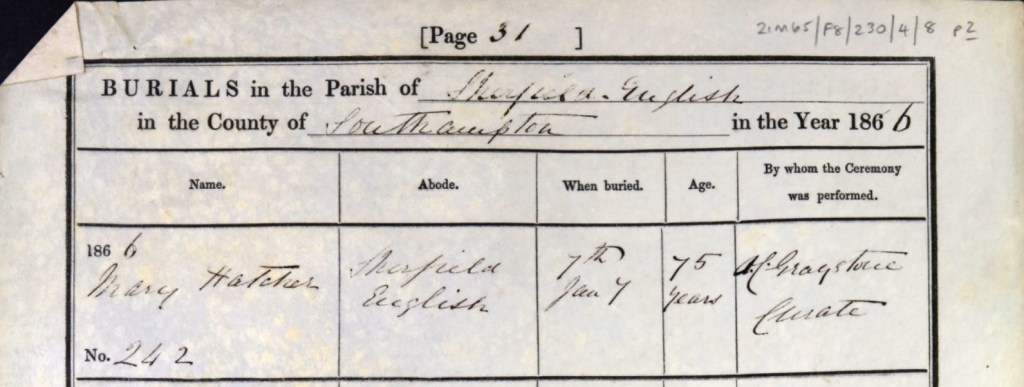

The burial was performed by the minister, W. Watson, whose hand would have once again recorded this moment in the parish register, an entry that would remain for future generations to uncover. The simple notation in the register reads: “21 Dec Buried William Roud.” Though brief, this entry is a testament to a life that once filled the Roud household with strength and presence, a life now reduced to a name on a page. It is in these moments, these records of finality, that the lives of our ancestors are both immortalized and marked by the inevitability of loss.

At William’s burial, Stephen Nobb, the churchwarden, was present, as was customary in such occasions. The churchwarden’s role in overseeing the church and its grounds made him a constant presence during these solemn rites, ensuring that the traditions of the community were upheld. As the churchwarden, Stephen would have stood as a symbol of the steady continuity of life in Sherfield English, a keeper of both physical and spiritual boundaries.

For Mary, her father’s burial marked the end of an era, a final farewell to the father she had never truly known. Yet, as she grew, the memory of William, her father’s presence in the community, and his place in the churchyard would shape the woman she would become. The churchyard, now home to both her brother James and her father, would serve as a quiet reminder of the love and loss that defined the foundation of Mary’s early life. Each visit to Saint Leonard’s Church would have brought with it the weight of these memories, woven into the fabric of her own story, even as she carried on, moving through life in the way that all those before her had done, holding her family, her faith, and her resilience close to her heart.

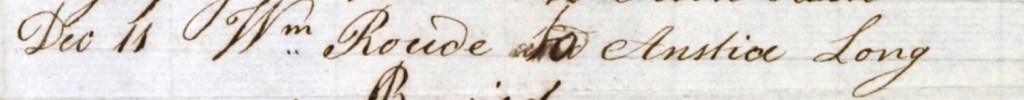

On Wednesday, the 11th day of December, 1799, a significant moment in the history of the Roud family took place within the hallowed walls of Saint Leonard’s Church in Sherfield English. William Roude, Mary’s older brother (my 4th Great-Granduncle and my 5th Great-Grandfather), was married to Anstice Long (my 5th Great-Grandmother), a woman who would become an integral part of the Roud family legacy. At 22 years old, William stood alongside Anstice, ready to begin a new chapter of his life, one that would eventually bring children, change, and new memories to the family that had already weathered much.

The wedding ceremony was conducted by Minister Thomas William, who, with steady hands and careful words, united the couple in the sacred bond of marriage. As was customary at the time, the marriage would have taken place before a small but meaningful gathering of family and friends, a community bound together by shared faith and tradition. The vows exchanged in that moment would have been filled with the weight of promises, expectations, and hopes for a future built together.

In the parish register, under the section for baptisms, marriages, and burials for the year 1799, Minister Thomas William carefully recorded the event with a single, simple line: “Dec 11 Wm. Roude to Anstice Long.” The brevity of this entry does not diminish its significance. It is a quiet acknowledgment of a pivotal moment in Mary’s life and in the history of her family. The few words written on the page capture a life-altering commitment, a union that would create new branches on the family tree.

At the time of William and Anstice’s marriage, Jason Ball and William Nobble were the church wardens, entrusted with the care of the church and its sacred ceremonies. Their role in the church, overseeing the practical details of worship and ceremony, would have been integral to ensuring that everything ran smoothly on that important day.

For Mary, her brother William’s marriage marked the beginning of a new chapter, not just for him, but for the entire family. As the Roud family grew, each marriage, each new birth, and each celebration would be a reminder of the unbroken threads of love, faith, and history that continued to weave through the generations. The union between William and Anstice, formed in the quiet reverence of Saint Leonard’s Church, would become another cherished part of the tapestry of Mary’s own life, a reminder that in the ebb and flow of time, family, love, and commitment endure.

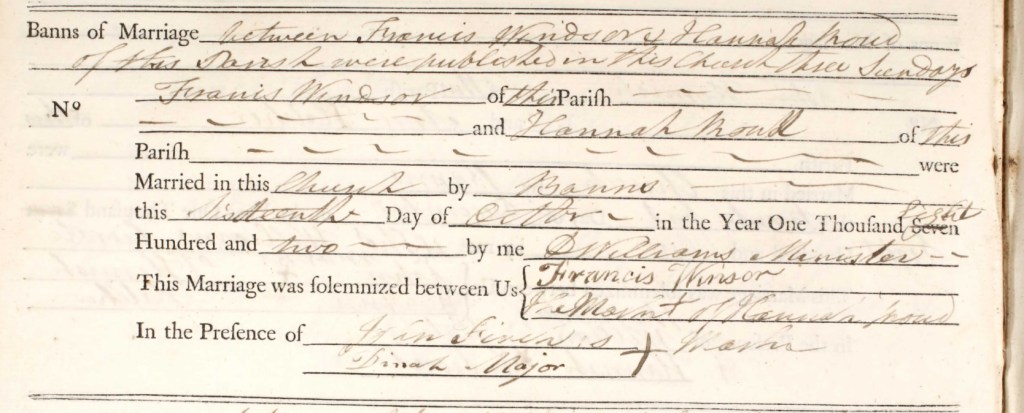

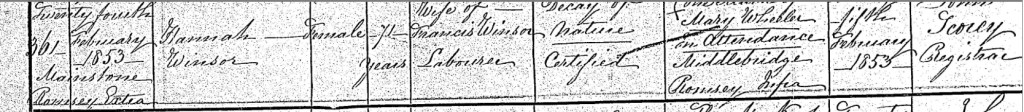

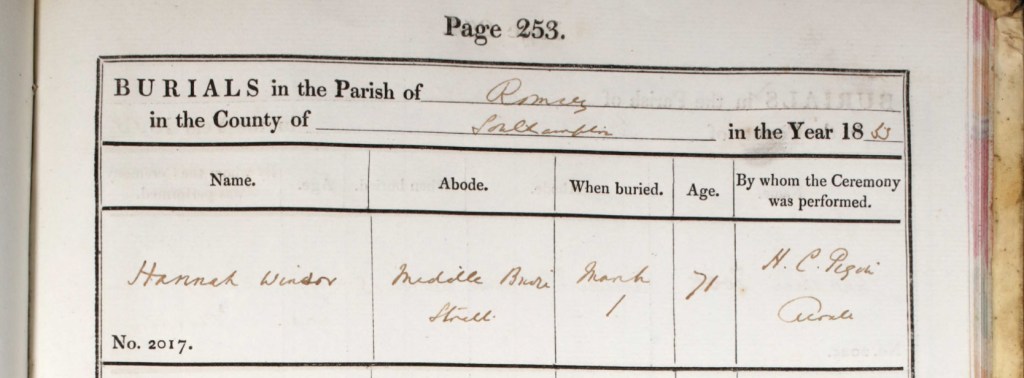

On Saturday the 16th day of October 1802, Mary’s sister, Hannah Roude, was married to Francis Winsor in a ceremony that took place at the beloved Saint Leonard’s Church in Sherfield English. At the tender age of 20, Hannah began a new chapter in her life, joining hands with Francis in the bond of matrimony. The atmosphere at the church would have been filled with a quiet reverence, as this union was not just a personal commitment, but a moment woven into the fabric of the community's shared faith and tradition.

The marriage ceremony was performed by Minister D. Williams, who, as the official witness, ensured that the sacred rite was conducted according to the established customs of the time. The banns of marriage, a public declaration made three Sundays prior to the wedding, had been read aloud in the church, notifying the congregation of the couple's intention to marry. This was a necessary part of the process, ensuring that no one could come forward to object, and that all were aware of the union being formed.

In the parish register, under the section for marriages, the details of Hannah and Francis’s wedding were recorded with care. The entry reads as follows:

“Banns of Marriage between Francis Windsor & Hannah Roude of this Parish were published in this Church three Sundays.

Francis Windsor of this Parish and Hannah Roude of this Parish were Married in this Church by Banns this Eighteenth Day of October in the Year One Thousand Seven Hundred and Two by me D. Williams Minister.

This Marriage was solemnized between Us,

Francis Windsor,

Hannah Roude,

In the Presence of

John Finch,

Dinah Major.”

This record, though simple, captures the significance of the moment:

the union of two individuals in the eyes of God, witnessed by family and community, and solemnized within the sacred space of Saint Leonard’s Church. The presence of John Finch and Dinah Major, who signed as witnesses, marked the occasion, grounding the event in the collective memory of the village. Their signatures, added to the register, are a reminder of the role that each person played in supporting the couple as they began their married life together.

For Hannah, this marriage to Francis Winsor would have been a turning point, a new path forward in the company of her husband. As the years went on, their lives would have intertwined with the fabric of family and community, filled with the quiet joys and struggles of rural life in Hampshire. And for Mary, her sister’s wedding was yet another reminder of the changing seasons of her own life, of the ongoing march of time and the unbroken ties of family that would continue to shape her future.

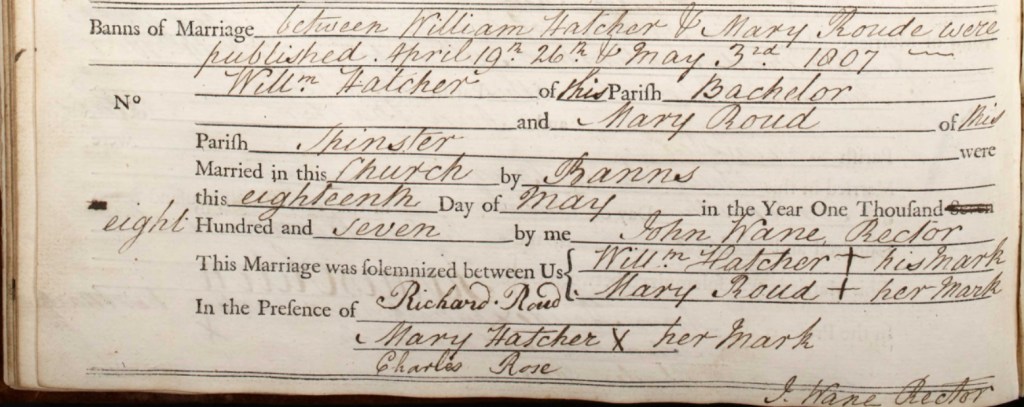

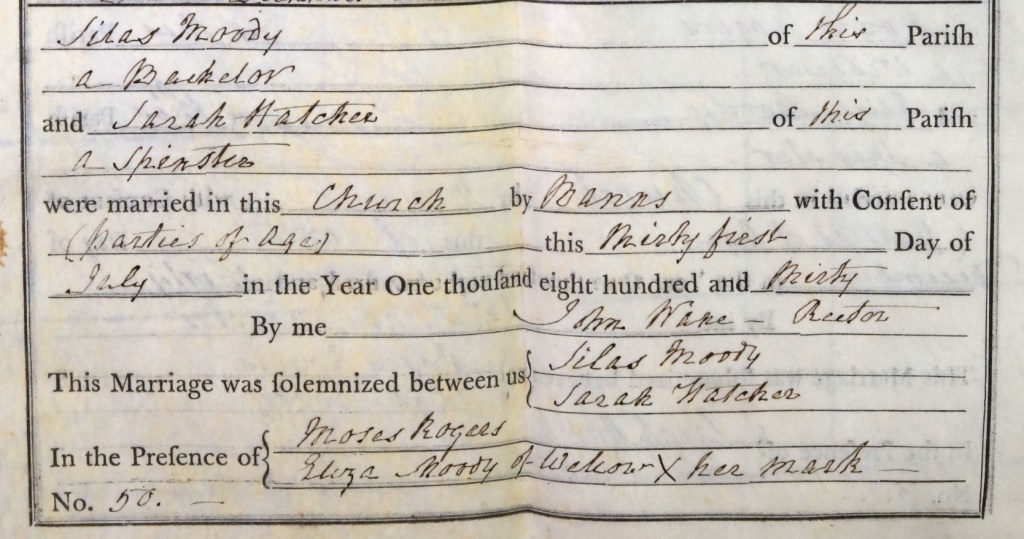

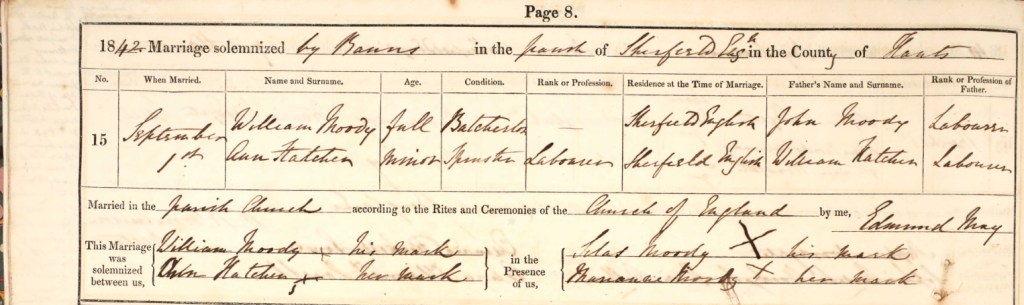

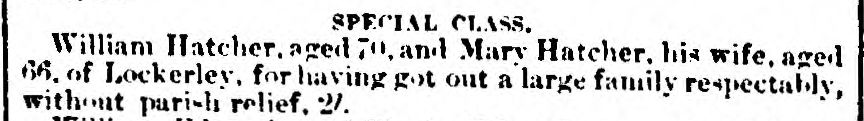

On Monday, the 18th day of May, in the year 1807, within the humble and familiar walls of Saint Leonard’s Church in Sherfield English, Hampshire, Mary Roud, a spinster of the parish, stood quietly beside William Hatcher, a bachelor, as they pledged their lives to one another in marriage. It was a simple, yet profoundly meaningful moment, a union of two local souls, coming together in faith and love before their community. The church, filled with the faint scent of candles and the timeless presence of those who had come before, bore witness to this new beginning.

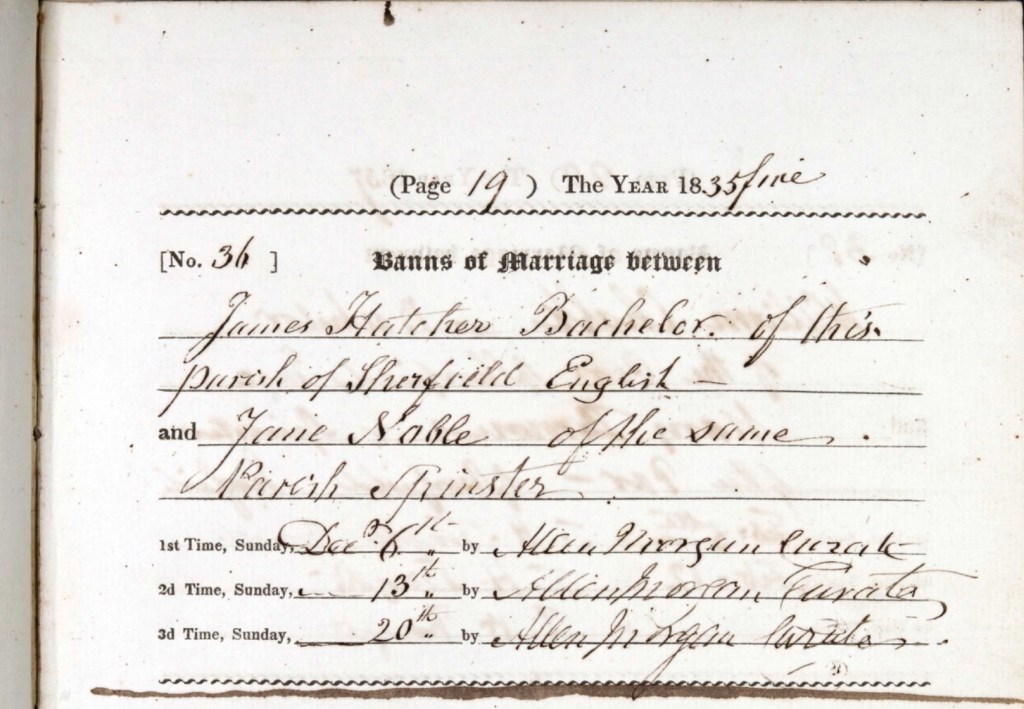

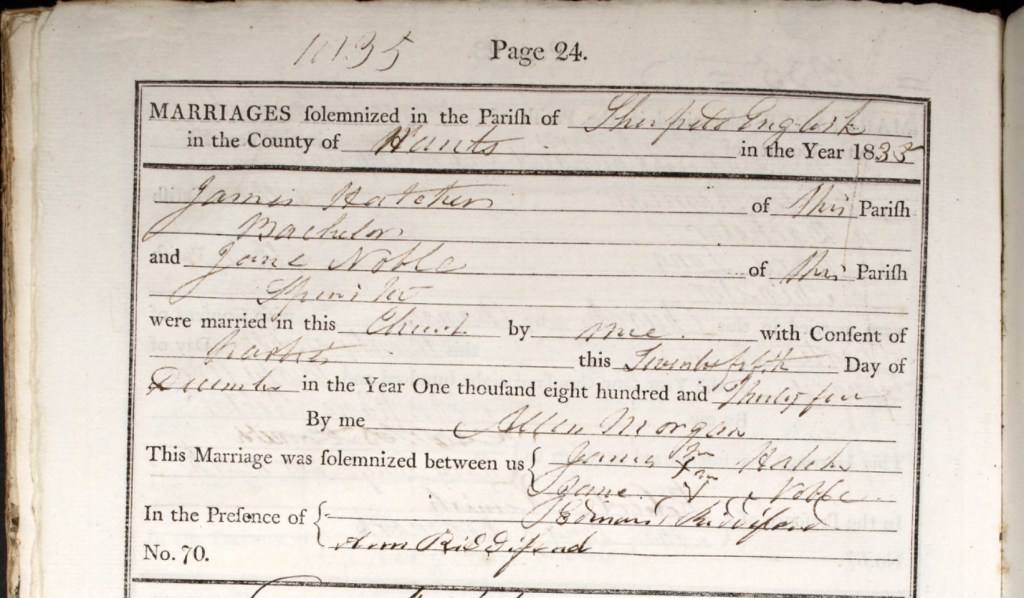

The banns of marriage had been read aloud over three successive Sundays, April 19th, April 26th, and May 3rd, giving the community the opportunity to witness and prepare for the joining of William and Mary. The tradition of publishing banns was not just a formality, but a public declaration of intent, ensuring that all were aware and had the chance to object if there was reason. It was an important step in the path of commitment, both for the couple and for the parish they called home.

In a ceremony led by Rector John Wane, the couple stood before their witnesses, each marking the moment in their own way. Mary, though she did not sign her name, marked the marriage register with a simple "X" her mark not a symbol of illiteracy, but a powerful testament to her life. In a time when women were often defined by their roles as daughters, wives, and mothers, Mary’s humble gesture carried with it a quiet strength. It spoke not only of her commitment to William, but of the simplicity and depth of love during those years. Her courage and devotion, deeply rooted in faith and family, were evident in that simple mark, a symbol of a life bound by love, faith, and hope for a future shared with another.

With her family by her side, Mary made her vows, a quiet promise to walk together through life with William, in the presence of God and their community. Her brother, Richard Roud, stood as a witness, his presence both a familial anchor and a quiet support for his sister on this significant day. And though Mary did not sign her name, the marks of others, those who stood by her, were recorded with care. Among the witnesses were Mary Hatcher, perhaps a relation to William, and Charles Rose, whose names are forever etched in the register as part of the circle of family and friends that supported this union.

The entry in the parish register reads:

“Banns of Marriage between William Hatcher & Mary Roud were published April 19th, 26th & May 3rd, 1807. William Hatcher of this Parish Bachelor and Mary Roud of this Parish Spinster were Married in this Church by Banns this eighteenth Day of May in the Year One Thousand Eight Hundred and Seven by me John Wane, Rector. This Marriage was solemnized between Us: William Hatcher X his mark,

Mary Roud X her mark.

In the Presence of: Richard Roud,

Mary Hatcher X her mark,

Charles Rose.”

Mary’s simple mark in the registry was not a sign of a lack of education or strength, but rather a poignant and powerful symbol of her commitment, her faith, and her trust in the future. In a time when women’s choices were often limited, her choice to marry William Hatcher was an act of courage, a pledge not only of love, but of her place in the world. It was a moment that carried with it not just a promise of companionship, but the shared hope of a future built together, rooted in family, faith, and the enduring strength of love.

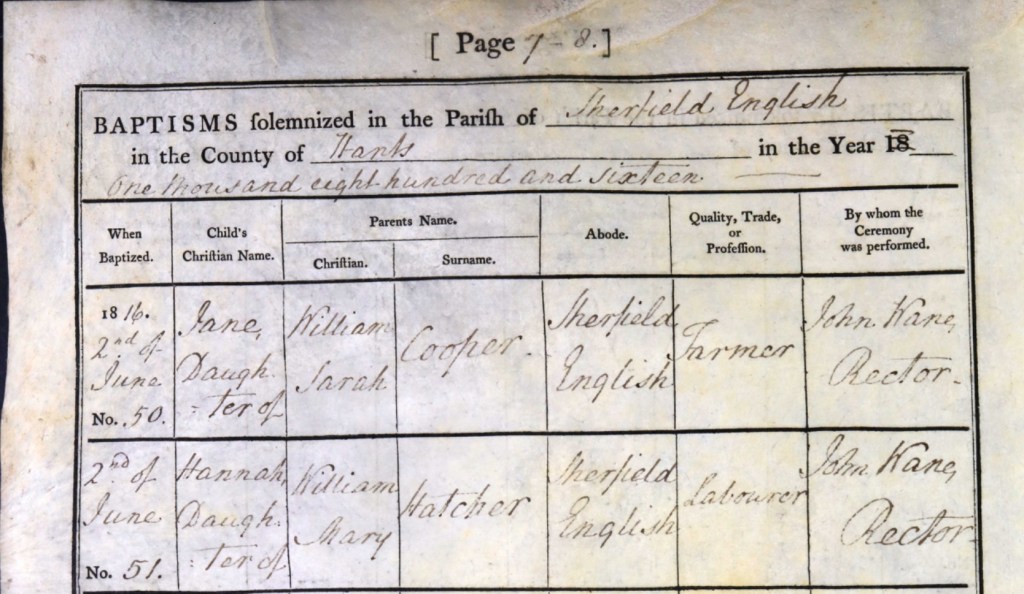

The year 1808 brought a new chapter to Mary Roud’s life, one that would forever change the course of her story. At the tender age of about 16, Mary, now Mary Hatcher, stood at the threshold of motherhood, her life already transformed by the marriage to William Hatcher, the man she had pledged her heart to in May of 1807. William, only a few years older than Mary at about 21, had become her companion in life, and together they were about to embark on the journey of parenthood.

In the quiet rural village of Sherfield English, Hampshire, Mary gave birth to her first child, a baby girl they named Sarah Hatcher. The details surrounding Sarah’s birth, though shrouded in the passage of time, paint a poignant picture of what life must have been like for Mary in the early 19th century. Though Sarah’s exact birth date remains uncertain, census records offer a faint outline of her arrival, likely in 1808, as suggested by the entries in 1841, 1851, 1861, and 1871, which note her birth in Sherfield English and estimate her year of birth as 1811, 1808, or 1807 depending on the record.

The birth of Sarah would have been a moment of both joy and fear, the emotions that often accompany the arrival of a firstborn. Childbirth in the early 1800s was a perilous journey for any woman, especially for a young girl like Mary, still finding her way in the world. The pain of labor would have been raw and unrelenting, and Mary would have relied on the experience and support of other women, her mother, perhaps, or her neighbour’s, who would have guided her through the process in the way that women have done for centuries. The absence of modern medicine and the fear of complications made each birth a dangerous gamble, one that Mary and William would have faced together, praying for the health of their newborn child.

In the small, close-knit community of Sherfield English, the birth of a child was an event that brought families together. While the harsh realities of rural life made things difficult, there would also have been joy in the air, the excitement of a new life, a new beginning, and the continuity of family. Mary, in the solitude of her home, would have held Sarah in her arms for the first time, gazing at her tiny daughter, knowing that this moment would change everything. The overwhelming emotions of motherhood, love, fear, protectiveness, must have rushed through Mary’s heart, her life now irrevocably bound to this tiny being she had brought into the world.

As Mary adjusted to the demands of motherhood, her world would have become focused on the needs of her growing family. The days would have been filled with the quiet rhythm of feeding, rocking, and caring for Sarah, while also continuing the responsibilities that came with running a household. William, her husband, would have worked alongside her, tending to the land, providing for the family, but the burden of daily life would have largely fallen on Mary’s shoulders. Still, as difficult as these years were, there was no shortage of love between the young couple, and their bond would have only deepened as they shared the joys and struggles of raising a child.

In the years that followed, the world around Mary would slowly begin to change. But in the early days of Sarah’s life, as Mary held her daughter in her arms, it was not the future that occupied her thoughts but the small moments of daily life. The soft cries of a newborn, the warmth of her baby nestled against her chest, the quiet moments of comfort and connection, these were the things that made up her world.

Though time has obscured much of Mary’s life, and the specific details of Sarah’s birth and early years remain elusive, the essence of Mary’s motherhood is still palpable. She was a young woman, surrounded by the love and support of her family and community, stepping into the unknown with a sense of purpose and devotion. Her story, marked by the birth of her first child, is one that reflects the quiet strength of women in a time when life was often uncertain, but where love and family provided an unshakable foundation.

Mary’s experience giving birth in 1808 was far from easy, but it was an experience marked by the deep resilience of a mother’s love. Through her, Sarah’s story began, and with each new day, Mary’s life and the lives of those around her were shaped by the bonds of family, the promise of a brighter future, and the quiet beauty of the lives they built together in the heart of Sherfield English.

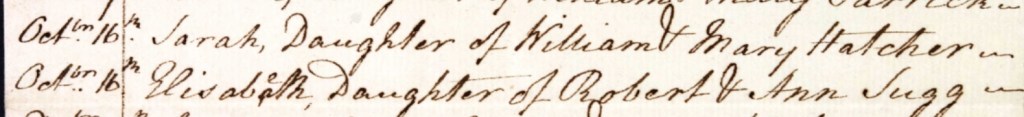

On a crisp autumn day, when the rich-colored leaves gently floated to the earth and the trees stood bare, Mary and William Hatcher stood before God and their community at Saint Leonard’s Church in Sherfield English, Hampshire, to have their daughter, Sarah, baptised. It was Sunday, the 16th day of October, 1808, and the small church, with its stone walls and centuries of history, was filled with the soft light of a late autumn sun, casting a golden hue over the proceedings.

Rector John Wane, a steady figure in the life of the village, led the Sunday service with quiet reverence. As the congregation gathered in the familiar pews, the air would have been thick with the weight of the sacred ritual. Mary, still a young mother, cradled her precious daughter Sarah, her heart full of both love and hope for her child’s future. William, by her side, would have stood with the quiet pride of a father, witnessing the moment his daughter was formally welcomed into the fold of their faith.

The baptism of Sarah was shared with another child, Elizabeth Jugg, daughter of Robert and Ann Jugg. It was a communal act of faith, a joining of families under the watchful eyes of the church and its rector. As the ceremony unfolded, the sacred words of baptism echoed through the church, binding the children to their family, to their community, and to the long line of ancestors who had come before them.

After the service had ended, Rector John Wane carefully recorded the baptism in the parish register for the year, documenting this sacred moment for history. In his elegant script, he wrote with simplicity yet profound meaning:

“Oct 16th Sarah daughter of William and Mary Hatcher.”

These few words, simple and brief, captured the essence of the day, Sarah’s entrance into the faith, her place in the world, and her connection to a family that would nurture and protect her for the years to come. Mary and William’s hearts swelled with pride and hope as they stood in that small, sacred space, their daughter now marked by this ritual, forever linked to her heritage, her faith, and her parents’ love.

For Mary, the baptism of Sarah was not just a moment in time but a reflection of her deep devotion to her family, to her faith, and to the life she was building alongside William. The church, with its centuries-old walls and the generations of people who had walked through its doors, bore witness to this quiet moment in their lives, marking Sarah’s place in the long line of history that began with her parents. It was an act of both love and hope, a promise that no matter what the future held, Sarah would always be surrounded by the embrace of her family and faith.

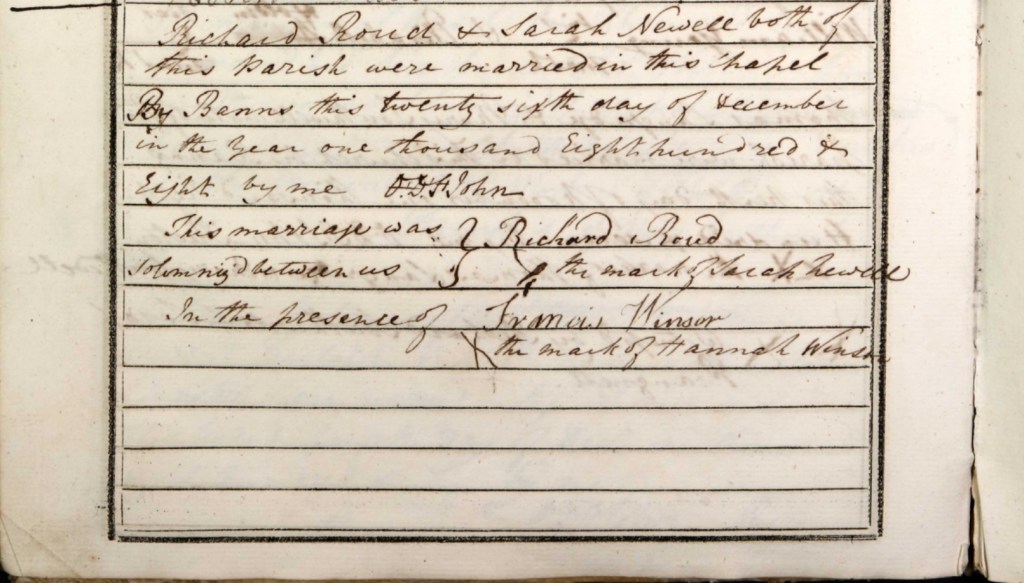

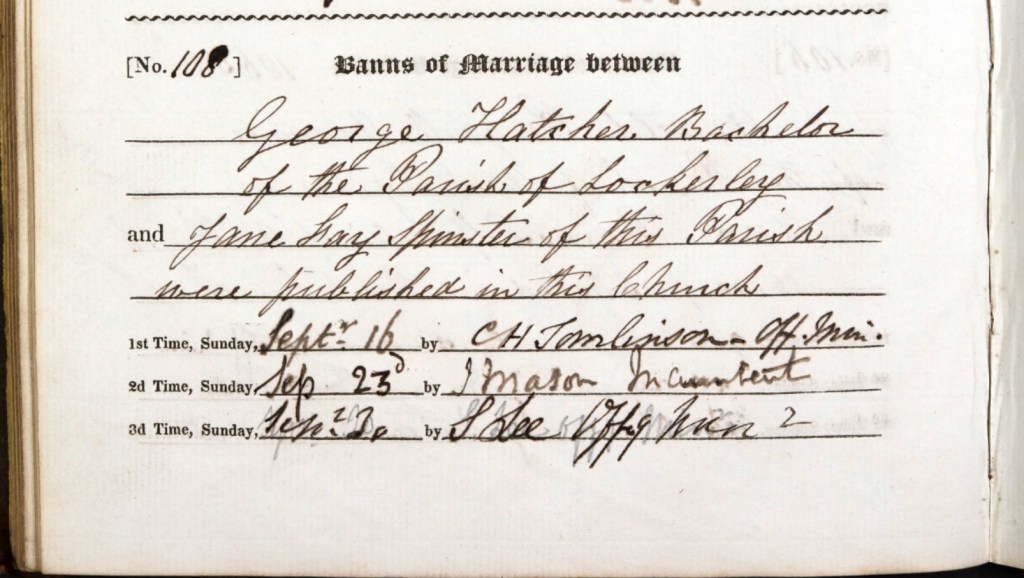

On the frosty Sunday, the 26th day of December, 1808, the village of Lockerley lay wrapped in the stillness of winter, its bare trees dusted with the first breath of snow. Within the humble yet sacred walls of Saint John’s Church, the quiet of the season was broken only by the soft murmur of voices, the rustle of coats, and the warmth of family gathered together for a momentous occasion. It was here, in this familiar chapel, that Mary’s brother, Richard Roud, stood beside his bride-to-be, Sarah Newell, ready to pledge his life to hers.

The day was cold, the winter air likely thick with the visible breath of those gathered, yet within the church, the warmth of love and devotion filled the space. Richard, a man of quiet strength and humility, stood firm in his resolve, ready to make his vows. Beside him was Sarah Newell, the daughter of Joseph and Emma Newell née Drake (my sixth great-grandparents), whose grace and inner strength had been passed down through generations. Sarah was not just a bride, she was a continuation of a legacy, her own family, like Richard’s, steeped in the values of faith, love, and the steadfast ties of community.

As the ceremony unfolded, the significance of this union went beyond mere formality. This was the joining of two souls, bound not only by their love for each other but by the shared history and kinship that defined their lives. Richard and Sarah’s hands joined in solemn promise, their lives now intertwined in a bond that would carry them through the years to come. The vows were exchanged, sealed with the quiet power of commitment, and witnessed by two important figures, Mary’s and Richard’s sister, Hannah Winsor, and her husband, Thomas Winsor. Their presence was more than a formality, it wove a deeper fabric of family and connection into the sacred space of the church.

The ceremony was conducted by clergyman W. H. John, who, with careful reverence, entered the details of their union into the parish register. His hand recorded the moment for posterity, knowing that these names, Richard Roud and Sarah Newell, would become part of the long, winding thread of their family's history.

The entry in the register reads:

“Richard Roud & Sarah Newell, both of this Parish, were married in this Chapel by Banns this twenty-sixth day of December in the Year one thousand eight hundred & eight by me, W. H. John. This marriage was solemnized between us:

Richard Roud,

the mark X of Sarah Newell,

In the presence of:

Thomas Winsor,

the mark X of Hannah Winsor.”

This moment, though now faded into the yellowed pages of time, was far more than a simple entry in a dusty register. It was the beginning of a new chapter in a long lineage, a legacy built on love, strength, and kinship. In the years that followed, Richard and Sarah would forge a life together, one marked by both challenges and joys. But even as time has moved forward, their union continues to echo through the generations, a testament to the enduring power of family, love, and the shared history that connects us all.

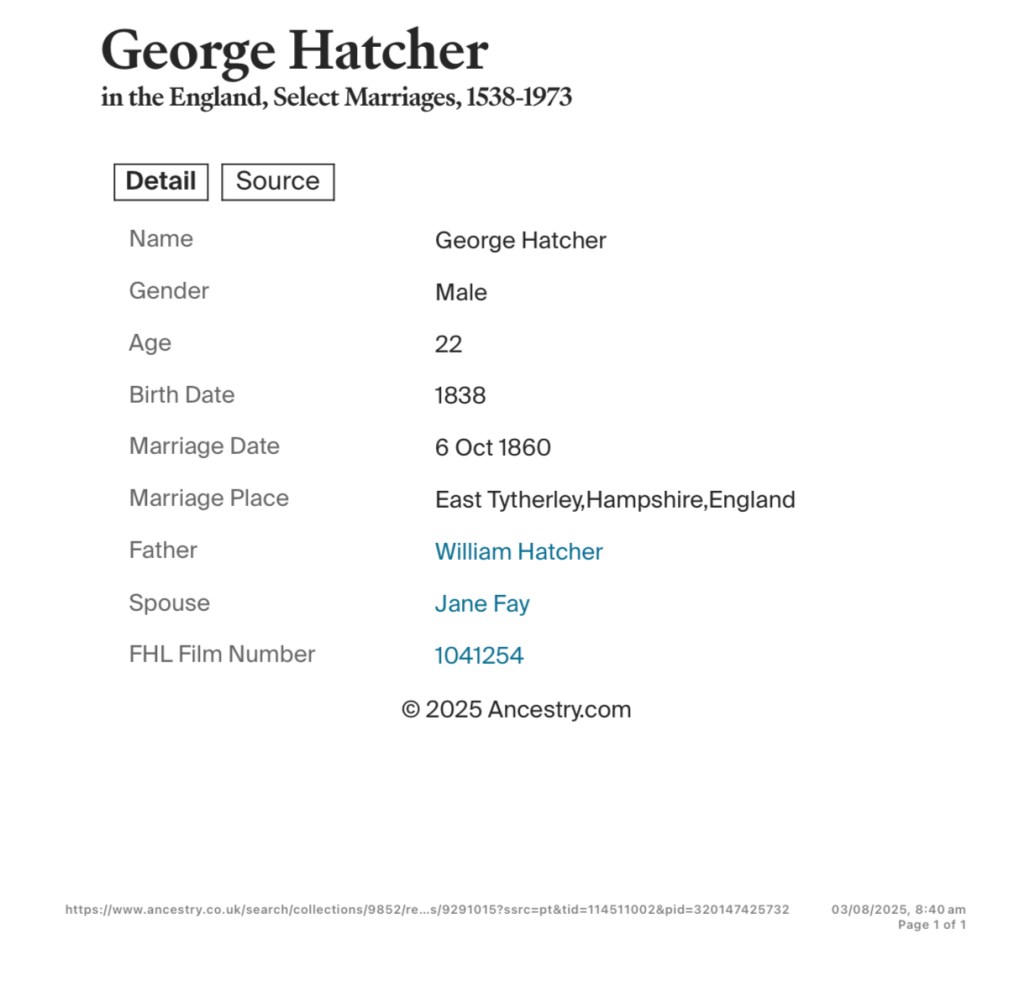

St. John’s Church in Lockerley, Hampshire, is a charming and historic church that has served the local community for centuries. Located in the heart of the picturesque village of Lockerley, which lies in the Test Valley, the church is an important part of the area’s history, culture, and spiritual life.

The history of St. John’s Church dates back to the medieval period, though the current structure reflects several stages of development over the centuries. The original church was likely built around the 12th century, though records from that time are sparse. The church’s dedication to St. John the Evangelist indicates its religious association with the Christian tradition, particularly with the apostle John, one of the most prominent figures in the New Testament. The church’s early history is tied to the broader religious and agricultural practices of the village, which has been a rural community for much of its existence.

Over the centuries, St. John’s Church was subject to several expansions and renovations. The original Norman structure would have been relatively simple, reflecting the needs of a small rural community. However, as Lockerley grew and developed, particularly during the medieval and post-medieval periods, the church was modified to accommodate a larger congregation and to reflect the changing architectural styles of the time. One of the most notable periods of change came in the 19th century, when the church was rebuilt in the Victorian era.

The current building of St. John’s Church was constructed in 1889–90 under the direction of the architect J. Colson, in a style that blends both Gothic and Perpendicular Gothic elements. This period saw significant growth in the Test Valley, and Lockerley, with its proximity to the town of Romsey, benefitted from an expanding population and increased prosperity. The design of the church reflects the period's architectural tastes, with soaring arches, intricate stained-glass windows, and the use of local materials that give the church a distinctive character.

St. John’s Church is a relatively large and impressive building for a rural village church. The structure features a chancel with an outshot, a nave with transepts, and a southwest tower that adds a sense of grandeur to the village’s skyline. The church’s stained-glass windows, depicting various scenes from the Bible, are particularly beautiful, and they provide a striking contrast to the stonework of the building. The wooden roof of the nave, designed with king-post trusses on arch-braces, is another notable feature of the interior, displaying the craftsmanship of the period.

Over the years, St. John’s Church has been at the center of life in Lockerley, hosting regular religious services, weddings, baptisms, and funerals. The churchyard is the final resting place for many of the village’s residents, with gravestones marking the passage of time and offering a sense of continuity to the village’s history. The church continues to play an important role in the spiritual life of the community, offering a space for worship, reflection, and prayer.

In addition to its role as a place of worship, St. John’s Church has also served as a venue for significant community events. The church is a place where people come together to mark important milestones, both religious and personal. Many of the village’s residents, both past and present, have been married, baptized, or buried in the church, giving it a special place in the collective memory of Lockerley.

The churchyard itself is a peaceful and tranquil space, with the graves of local families dotting the landscape. These graves serve as a reminder of the long history of Lockerley, and they provide a connection to the past. The churchyard is not only a site of historical importance but also a beautiful setting for reflection, surrounded by the natural beauty of the Hampshire countryside.

As for rumors of hauntings, like many historic churches, St. John’s has been the subject of local legends and ghost stories. However, there are no widely documented or substantiated paranormal occurrences associated with the church. Given the long history of the building and the village, it is not unusual for local folklore to suggest the presence of spirits or supernatural events. In many cases, such stories are passed down through generations, often becoming part of the cultural fabric of a place. While there may be occasional whispers or tales shared by the community about unexplained occurrences, there is no firm evidence to suggest that the church is haunted.

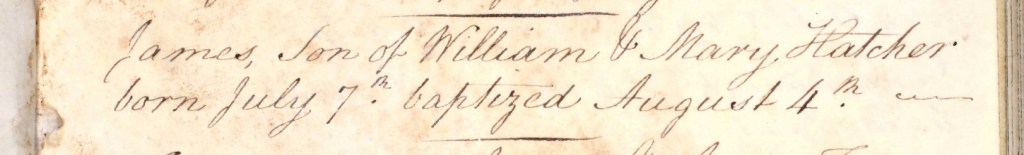

As the summer sun bathed the fields of Sherfield English, the landscape was alive with the vibrant colors of blooming flowers swaying gently in the breeze. The air was filled with the sweet melodies of birdsong, and the rich fields of corn, wheat, and barley swayed in abundance under the warmth of the summer sky. It was amidst this peaceful and fertile setting, on Sunday, the 7th day of July, 1811, that 19-year-old Mary, with her heart full of love and hope, gave birth to a bonnie baby boy. Her life, already deeply entwined with the rhythms of the land and the village, was about to change forever as she welcomed her second child, a son, whom she and William named James Hatcher.

Mary, still so young at 19, had already walked the path of motherhood once before, and now, with the birth of little James, she stepped once again into the world of sleepless nights and endless care, but also into a world of boundless joy. William, now about 24, stood by her side as the proud father of their growing family. Together, they marveled at their son, knowing that with him, their love and their legacy had expanded. James was more than just a child; he was a promise of the future, a living connection to the generations that had come before him and the ones that would follow.

The birth took place at their home in Sherfield English, where Mary and William had built their life together, surrounded by the familiar sights and sounds of the countryside. The house, humble but filled with the warmth of family, became the place where their little James would take his first breaths, his first cries, and where Mary would hold him close, just as she had done with her firstborn, Sarah. The bond between mother and child, deep and unwavering, was formed in that simple, sacred space, a place that would become rich with the memories of James's first years.

As Mary gazed down at her newborn son, she could not have known the life he would lead, but she knew, with certainty, that he would grow up surrounded by the love and support of his family. In a time when life was hard, when survival was often a struggle, there was no greater blessing than the gift of a child. And for Mary, James was not just a baby, he was a symbol of the enduring strength of family, of love, and of the quiet resilience that had been passed down through the generations.

In the fields around them, the harvest would come, as it always did, bringing with it the promise of abundance, just as James’s arrival promised a future of hope and joy for Mary and William. As summer flowers bloomed and the crops flourished, so too did their family, with James becoming a bright new thread in the tapestry of their lives.

On a warm summer's day in 1811, in the quiet village of Sherfield English, on the 4th day of August, Mary and William, carried their son James gently through the familiar doors of Saint Leonard’s Church, the same place where they had spoken their vows only a few years before. The stone walls of the ancient parish church, weathered by time and faith, bore witness as little James was baptized, welcomed not only into the Hatcher family but also into the enduring embrace of the Church and community. For Mary and William, it was a sacred offering of their child to God, a prayer for guidance, protection, and a life shaped by love and resilience. That quiet August day, etched into the parish register in delicate script, marked the beginning of James’s story, deeply rooted in faith, family, and the rural heart of Hampshire.

The clergyman whose name unfortunately isn’t mentioned in the baptism register, carefully wrote James‘s information for baptisms in Sherfield English in the year 1811.

James, Son of William & Mary Hatcher, born July 7th, baptized August 4th.

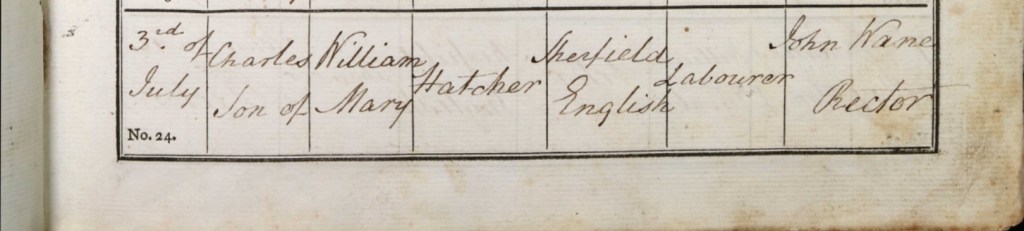

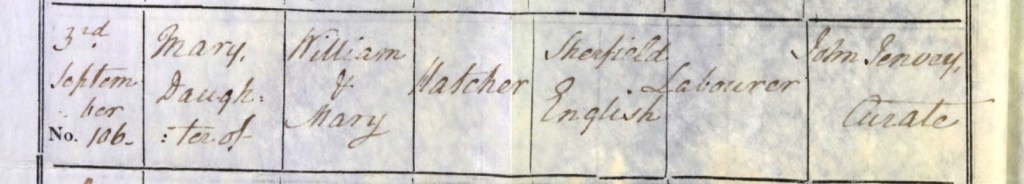

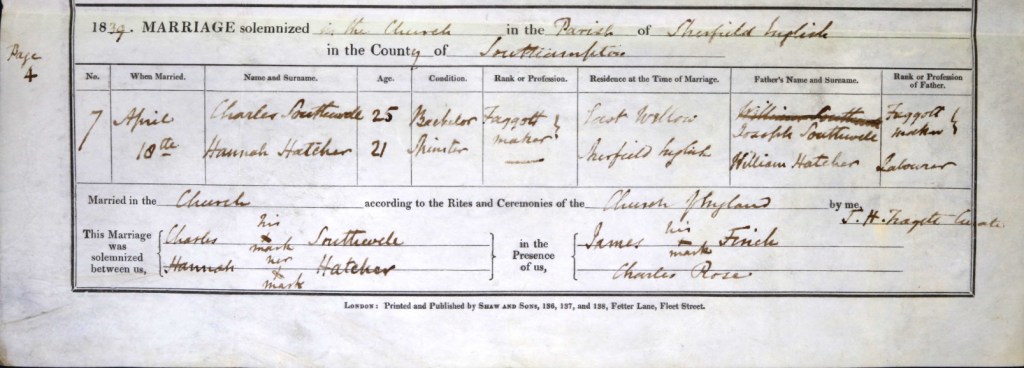

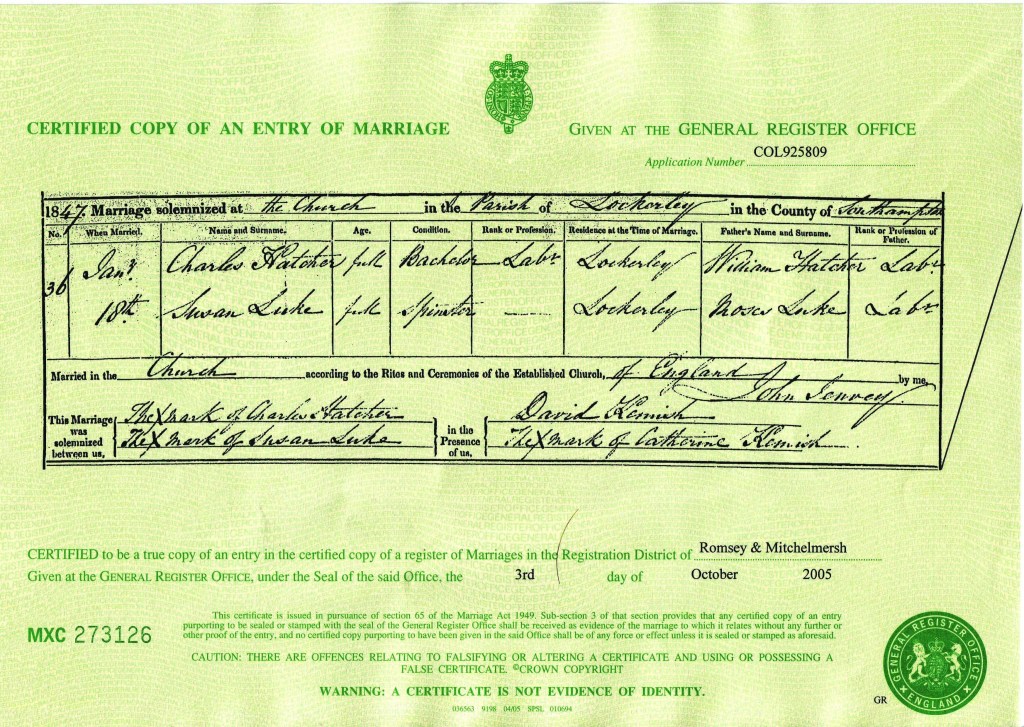

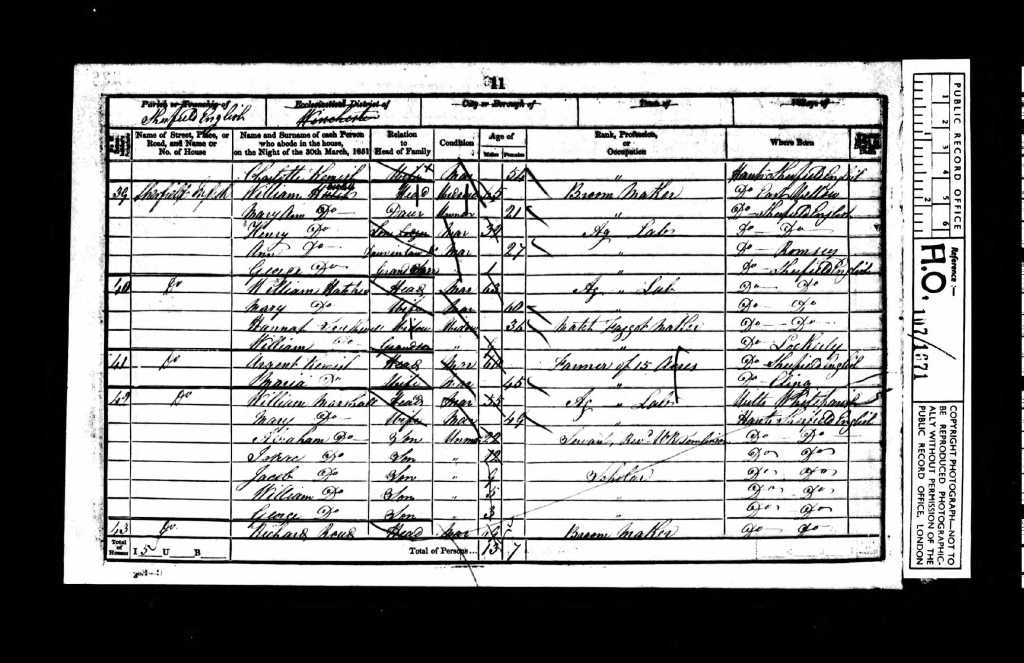

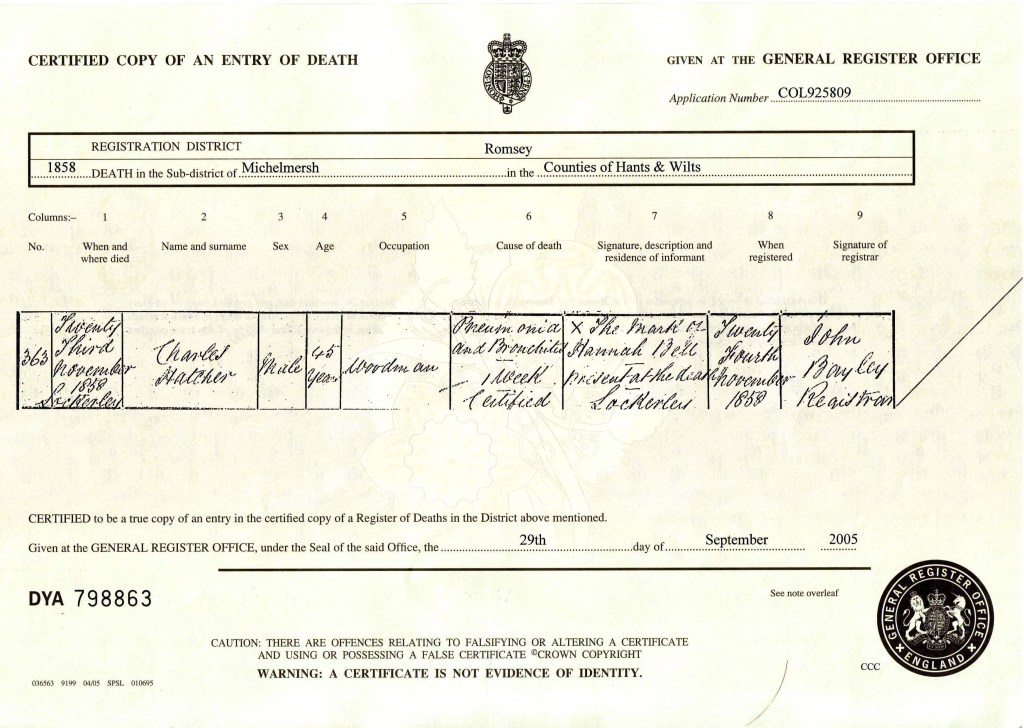

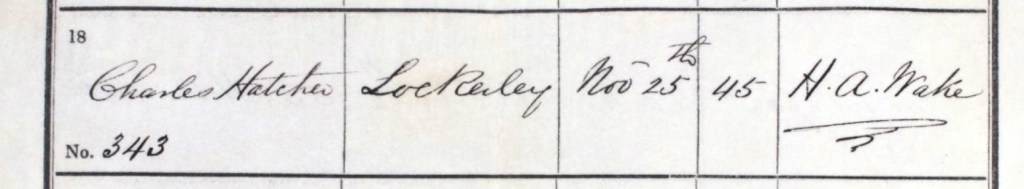

In the late spring, when the air was thick with the scent of fresh blooms and the promise of summer, Mary found herself once again on the threshold of motherhood. It was in the quiet, familiar surroundings of their humble home in Sherfield English, Hampshire, that she gave birth to a handsome baby boy, Charles Hatcher (my 3rd Great-Grandfather), in the early summer of 1814. At 22 years old, Mary had already experienced the trials and joys of motherhood twice before, with Sarah and James, but each birth, despite the familiarity of it, still held its own challenges.

Her husband, William, about 27 at the time, stood by as Mary gave birth, caring for their other two children, Sarah and James, while Mary was surrounded by the comforting presence of the women of her family, possibly even some close friends and neighbors. These women, bound by the shared experience of motherhood and community, would have provided Mary with the support she needed during the arduous process of childbirth. Despite this network of love and care, the physical pain and emotional strain of labor never became easier for Mary. Each birth was a raw and transformative experience, one that shaped her in ways words can hardly express.

Charles, though his exact date of birth remains elusive, was likely born in the late spring or early summer of 1814. Census records, though imprecise, give us some insight into his arrival, 1841 places his birth around 1816 in Hampshire, while the 1851 census narrows it down further, suggesting 1815 in Sherfield English. These entries, though rough estimates, offer us a glimpse into the year and location of Charles's birth, but it is the deeper, more intimate details of his arrival that Mary would have carried with her, her exhaustion, her joy, and her overwhelming love for the new life she had brought into the world.

As Mary cradled her newborn son, her heart filled with a quiet joy, knowing that her family had grown once again. William, no doubt, shared her pride, his heart swelling with the love he felt for Mary and their children. Their home, modest though it was, was full of life, laughter, and the unspoken bond that tied them together. Sarah and James, no longer the only children, would have been eager to meet their new brother, and in the months and years to come, the siblings would share in the joys and challenges of growing up in the rural landscape of Sherfield English.

For Mary, the arrival of Charles was not just another addition to her family, but a reminder of the strength, love, and resilience that had carried her through each chapter of her life. As she looked down at her son, she saw not only the future of her family but also the continuation of her own journey as a mother, a woman, and a person forever intertwined with the land, the community, and the love she shared with her husband and children.

Life in the quiet village of Sherfield English moved with the slow, deliberate rhythm of the land. The scent of cut hay lingered in the warm summer air, and the bells of Saint Leonard’s Church, worn smooth by generations of faithful hands, rang gently through the Hampshire countryside, marking the passing of time in the same familiar way they had for centuries. It was here, in this timeless space, that on Sunday, the 3rd day of July, 1814, a new name was spoken before God, and that name was forever etched into the pages of history: Charles Hatcher, son of William and Mary Hatcher.

The day was no grand celebration, but a simple Sunday service, as ordinary and humble as any other. Yet, within the cool, timeworn walls of Saint Leonard’s Church, it carried the weight of generations. This was the moment when Mary and William brought their son, Charles, before the congregation, not in the expectation of fanfare but in the quiet, solemn grace of a baptism, one that bound the child to faith, to family, and to the traditions of their community.

Mary, a mother shaped by years of hard work and quiet devotion, held her infant son gently in her arms, stepping forward to the font. The love she felt for him was immeasurable, but so was her understanding of the importance of this sacred ritual. She was offering him not only as her child but as a child of faith, a member of a larger community, and a part of the hope that the future would bring. Beside her stood William, his hands weathered and rough from the labor of the land. He was simply recorded as a “Labourer” of Sherfield English, and in those two words, his whole life was encapsulated. A labourer, yes, but in his simplicity, there was dignity, pride, and an unspoken strength that came from hard work and the quiet love of his family.

The baptism was solemnised by John Wane, the Rector of the parish, a man who had, over the years, presided over countless milestones in the lives of families like the Hatcher and Roud/e families, marriages, baptisms, and farewells. His steady hand had written their stories in the parish register, and now he stood once more, marking the moment when a new soul was welcomed into the community of faith.

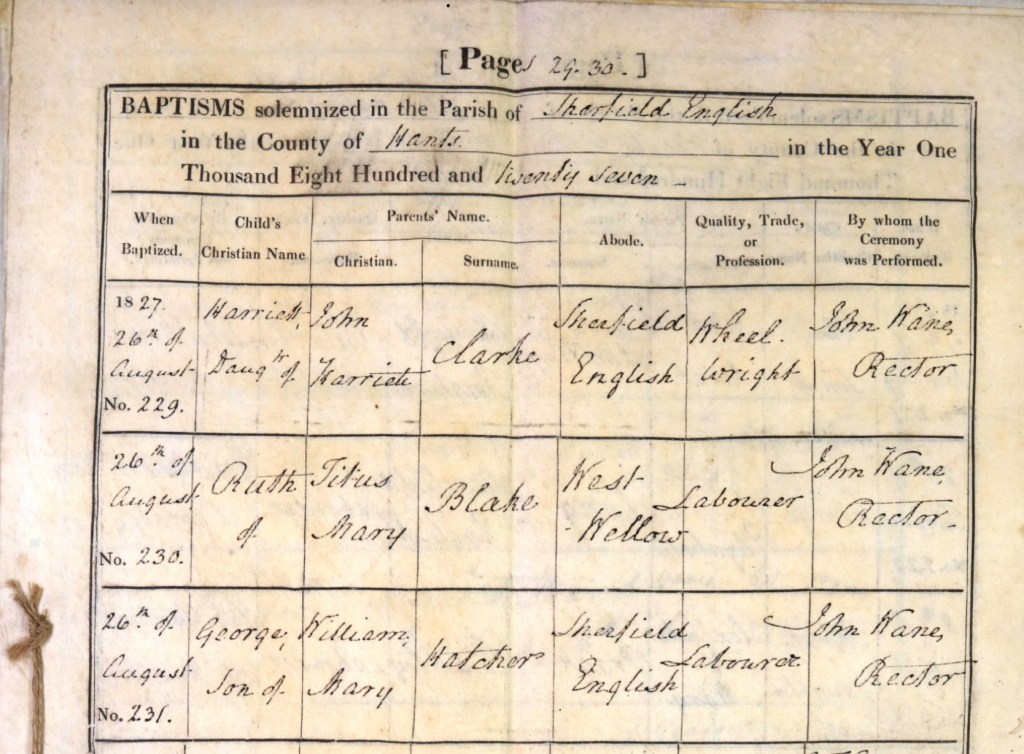

The entry in the register, inscribed in the rector’s steady script, reads:

“BAPTISMS solemnized in the Parish of Sherfield-English in the County of Hants in the Year One Thousand Eight Hundred and Fourteen.

When Baptised: 3rd July No. 24

Child’s Christian Name: Charles, Son of

Parents Name: William and Mary Hatcher,

Abode: Sherfield English,

Quality Trade or Profession: Labourer

By Whom the Ceremony was Performed: John Wane, Rector”

Entry No. 24, though seemingly just another line in a ledger, was so much more. It was a moment of grace, a quiet ritual that welcomed Charles into the life of the parish, into the ancient rhythm of a faith that had long sustained the people of Sherfield English.

Though Charles was born into modest means, he was rich in what mattered most. He was surrounded by the love of his parents, the strength of his community, and the enduring legacy of family that would carry him through life. He was blessed not with riches of gold or land but with something far more enduring, the love of those who came before him, the faith that had been passed down through generations, and the quiet understanding that family is the foundation of all things.

For Mary and William, the baptism of Charles was a simple but profound moment, one that solidified their role as parents, not just to a child of their own but to a child of the community, one who would grow up alongside his siblings, Sarah and James, and become a part of the legacy that had been built by those who came before him. The quiet grace of that day, written forever in the parish register, is a testimony to the love, faith, and family that would continue to shape Charles’s life and the lives of those who came after him, including me.

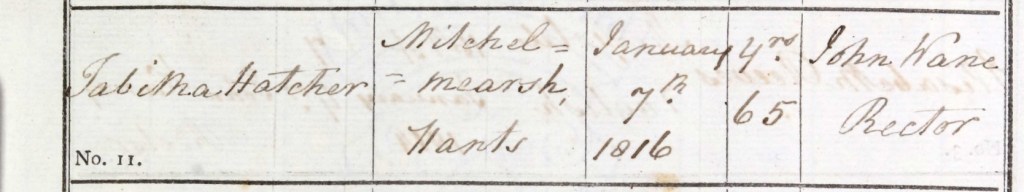

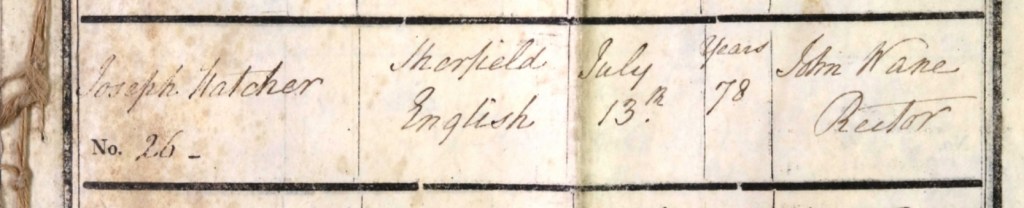

The year was 1816, and the cold January winds howled relentlessly around the village of Mitchelmersh, Hampshire, biting into the heart of the land with the sharpness only winter can bring. The village, typically so quiet and peaceful, now seemed to reflect the sorrow that had entered the homely walls of Mary’s in-laws' house, the warmth of hearth and family was now dimmed by a heavy grief. Mary’s beloved mother-in-law, Tabitha Hatcher (née Gardener), had passed away, leaving a silence that no words could fill.

Mary, her heart consumed by the deepest grief, found herself struggling to console not only her husband, William, but also her father-in-law, Joseph Hatcher, whose loss was perhaps the heaviest of all. Tabitha had not only been a mother-in-law to Mary, she had been a friend, a mentor, and a steadfast presence in her life. Their relationship had grown over the years, as Mary had come to know and cherish the woman who had shaped William into the man he had become.

Tabitha had been there through so many pivotal moments in Mary’s life. She had most likely been by Mary’s side during the births of her children, offering advice and comfort, guiding her through the joys and hardships of motherhood. As Mary had navigated the challenges of raising children in the rural rhythms of their community, Tabitha had been there to offer wisdom on what it meant to be a woman, to nurture her children, and to keep a home filled with warmth and love. She had taught Mary the delicate balance between running a household, preparing meals, caring for her children, and maintaining the spotless, welcoming home that was such an integral part of their life.

In the quiet moments, when Mary sat beside her mother-in-law’s bedside, it was clear that their bond ran deeper than just the obligations of family. It was a bond of love and mutual respect, forged through the shared work of caring for their family, supporting one another, and sustaining the values that had been passed down through generations. Tabitha’s passing was not just the loss of a mother-in-law, but the loss of a beloved teacher, a steady hand that had guided Mary through the most formative years of her life as a wife and mother.

Mary, though filled with sorrow, must have carried within her a profound sense of gratitude for the lessons Tabitha had imparted, the quiet wisdom that had shaped her into the woman she had become. And as she tried to console William and Joseph, she likely felt the weight of not only her grief but the responsibility of continuing the traditions that Tabitha had passed down, a legacy of love, family, and resilience that would now be carried forward through Mary and her children. Tabitha’s memory, like the winds of January that swept through the village, would leave a lasting mark on their lives, shaping them long after she had gone.

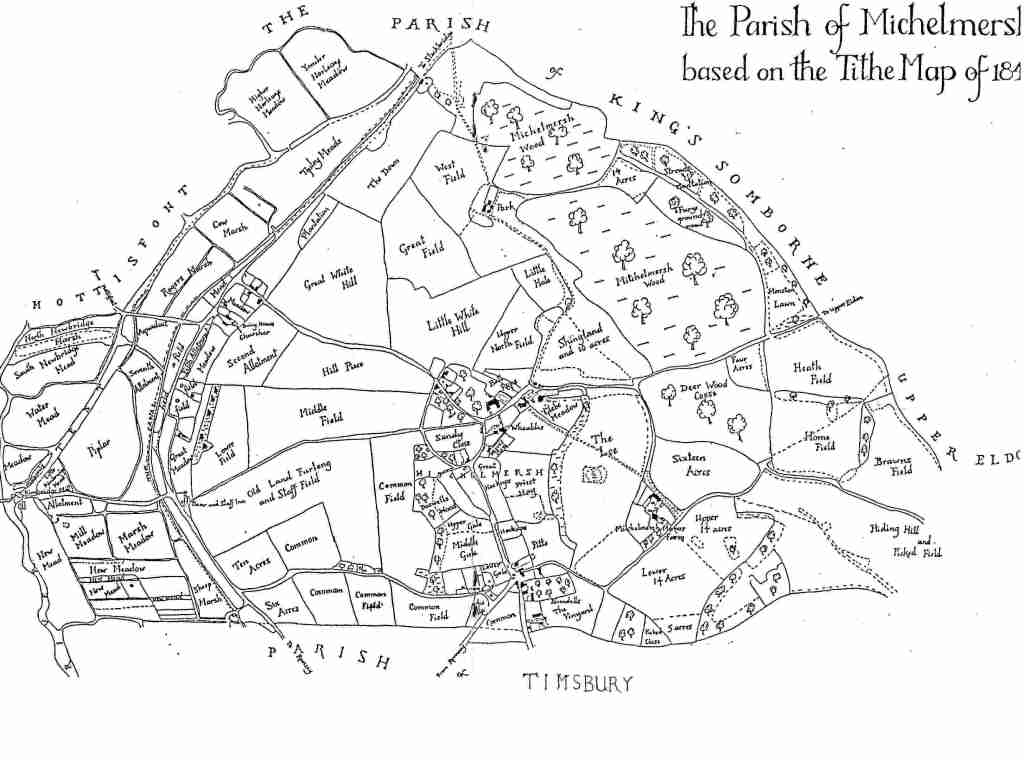

Michelmersh, a small village located in Hampshire, England, lies in the picturesque Test Valley, an area known for its rural charm and natural beauty. The village is steeped in history, and its development has been closely tied to the agricultural heritage of the region. Though it is now a quiet village, Michelmersh’s roots go back to medieval times, and its story is one of gradual transformation from a rural settlement to a part of the modern Hampshire landscape.

The origins of Michelmersh can be traced to the Saxon period, when it was likely a small agricultural settlement. The name "Michelmersh" is believed to derive from Old English, with "Michel" meaning "great" and "mersc" referring to a marsh or wetland area. This suggests that the village may have been originally located near marshy ground or a significant water source, an aspect that likely influenced its early settlement and development.

During the medieval period, Michelmersh was part of a larger manor system that was prevalent in England. The village was connected to the wider network of agricultural estates that characterized much of England at the time, with its economy largely based on farming, particularly the cultivation of crops and the raising of livestock. The presence of a local church, St. Mary’s Church, would have been central to village life during this period, serving as both a spiritual center and a communal gathering place.

In the Domesday Book of 1086, which recorded a detailed survey of England commissioned by William the Conqueror, Michelmersh is mentioned as part of the land held by the Norman lords. The records from this time show that the village, like many others, was a small yet thriving agricultural community, though it would have been under the control of a local lord. Over the centuries, the land would pass through the hands of various noble families, contributing to the shaping of the village's future.

During the 16th and 17th centuries, Michelmersh, like much of rural England, experienced significant changes as the English economy shifted. The rise of enclosed farming and the increasing importance of trade and commerce during the early modern period altered the social and economic fabric of many rural communities. Michelmersh saw the construction of larger homes and farmsteads, and as agriculture remained a cornerstone of village life, there was a growing emphasis on improving farming methods and land management.

The 18th and 19th centuries brought further transformations to Michelmersh, particularly with the onset of the Industrial Revolution. While the village itself remained largely agricultural, nearby towns like Romsey began to experience industrial growth. The arrival of the railway in Romsey, for example, contributed to changes in trade and transportation, which in turn affected rural areas like Michelmersh. During this period, the village remained a peaceful and rural community, though it likely saw an increase in population as people sought work in nearby towns or on larger farms.

The 20th century brought more changes to Michelmersh, especially as rural communities like it began to adapt to the demands of modern life. Agriculture continued to be an important part of the local economy, but the development of modern roads, schools, and social services allowed for better integration into the growing town networks. The construction of new homes and the expansion of residential areas saw Michelmersh become a part of the broader Romsey area, although it retained its character as a small village.

Today, Michelmersh is a quiet residential area that still holds much of its historical charm. Many of the original buildings, including the church, have been preserved, and the village is surrounded by farmland and open countryside, contributing to its appeal as a rural retreat. The local population is small, but the community remains active and engaged, with many residents valuing the village's historical connections and its peaceful surroundings.

Michelmersh’s location in the Test Valley ensures that it continues to benefit from the natural beauty of the area, with the River Test flowing through the region and providing opportunities for outdoor activities such as walking, cycling, and fishing. The village’s historical roots in agriculture continue to be a significant part of its identity, even as it has become more residential in character.