In the heart of Hampshire, where the rolling hills kiss the sky and the tranquil lanes meander through fields dotted with wildflowers, there existed a small village, Sherfield English, whose quiet charm whispered of lives lived in the rhythm of nature’s breath. It was in this peaceful haven, so far from the bustling world of city and grandeur, that Louisa Roude came into the world on a misty day in 1805, her first cries mingling with the whispers of the land that would forever be her home.

Her parents, William Roude and Anstice Long, both shaped by the soil of their ancestors, must have cradled her in a world steeped in simplicity, a life rooted in the rich soil of tradition, where every stone and tree bore the mark of a hundred years. In this world, a life like Louisa’s, humble, unadorned by the trappings of fame, might seem inconsequential to the casual observer. Yet, as we trace the faint threads of her existence through the tangle of parish records and the whispers of old documents, we uncover the undeniable truth, simplicity does not equate to insignificance.

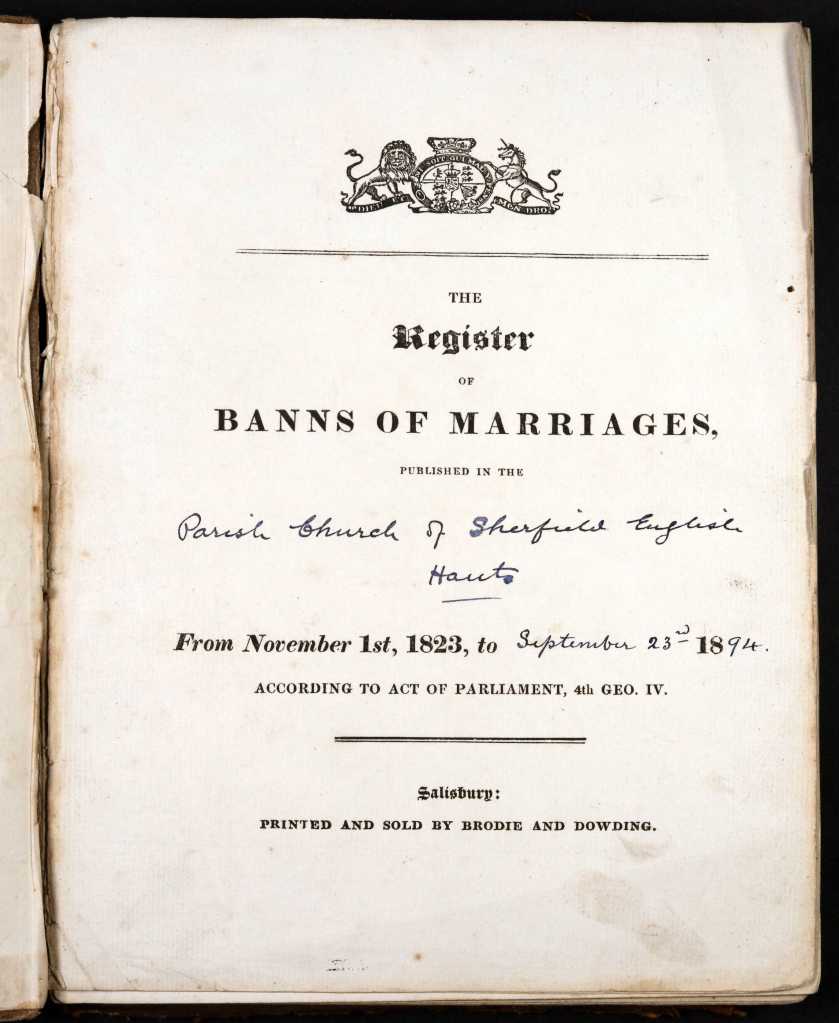

In tracing Louisa's steps, we venture not only into the past but into the very soul of our own heritage. With each name, each date, each fleeting detail captured in the delicate ink of parish registers, we rediscover the essence of what it means to belong. The painstaking hours spent deciphering faded handwriting, the relentless search for connections in crumbling records, these are the emotions of uncovering our own stories, the fragments of lives that build the mosaic of who we are today. It is a journey that stirs within us a deep and ancient longing, for in each record we find not just a name, but the pulse of a life once lived.

The Roude name itself, so fluid in its form, Roud, Roude, Rowde, seems to echo the transient nature of time, shifting like the tides of memory, each iteration a delicate reminder of the family’s enduring presence amidst change. And though Louisa’s life may have been marked by the quiet challenges of rural existence, it was a life woven with resilience and dignity, a quiet defiance against the forces of time that sought to erase her from the pages of history. For in her simplicity, there was a grace that transcended circumstance, a quiet beauty in her ordinary days.

As we embark upon the unfolding of Louisa’s story, we begin to see the importance of every detail, every moment, those often overlooked fragments that form the very fabric of life itself. For in the life of Louisa Roude, there was meaning in the everyday, a profound dignity in the humblest of existences, and a story waiting to be told through the prism of time.

Welcome back to the year 1805, Sherfield English, Hampshire, England. It is a year of great change and great uncertainty, set against a backdrop of global conflicts and domestic struggles. As we step into the world of this quiet Hampshire village, we find ourselves at the crossroads of an era marked by the echoes of war, the rise of industrialization, and the deeply entrenched class divides that shaped the lives of all who lived in it.

In 1805, England was under the rule of King George III, who, though beloved by many for his loyalty to the country, was also burdened by the heavy toll of mental illness. His reign, which had begun in 1760, was reaching a turbulent and challenging point, as political and social unrest simmered beneath the surface. The country was embroiled in the Napoleonic Wars, with much of Europe under the threat of Napoleon Bonaparte’s ambitions. The tension of war reached far beyond the royal court, shaping the thoughts and conversations of everyday people. George III’s son, the Prince of Wales, had assumed many of his father’s duties by now, though the King’s condition meant that the future of the monarchy seemed uncertain.

At the helm of government was the Prime Minister, Henry Addington, who had taken office in 1801 and remained in power through 1805. Addington’s government was known for its attempts to balance the pressures of war, with a focus on diplomacy, military spending, and domestic stability. His tenure was not without controversy, as his leadership style was often seen as ineffective when faced with the might of Napoleon's forces and the increasingly strained economy. His conservative approach to politics stood in stark contrast to the simmering calls for reform and change from a growing population of discontented citizens.

In Parliament, the year 1805 was marked by tensions between the ruling class and the growing voices of dissent. While the aristocracy and the landed gentry maintained a strong hold on power, the industrial revolution was beginning to shift the balance of society. The working class, while still largely rural and agrarian, was slowly becoming more concentrated in urban areas, giving rise to new forms of social organization. The political elite, however, were slow to acknowledge these shifts, continuing to pursue policies that favored the landed interests and the status quo. Reform movements, particularly those advocating for wider suffrage and better working conditions, had begun to stir, though it would be many years before significant change would come.

The divide between the rich and poor in 1805 England was stark. The wealthiest members of society lived lives of luxury and grandeur, enjoying estates that were symbols of their family’s power and history. They had access to the finest food, clothing, and education, and their homes were palaces of comfort and opulence. Meanwhile, the poor, particularly those in the rural countryside like Sherfield English, lived lives of grinding hardship. Many worked as farm laborers, dependent on the whims of nature and their landlords. Housing for the poor was basic, often little more than a small cottage with a thatched roof or a single-room dwelling shared by multiple generations. These homes were cold in the winter, damp in the spring, and poorly ventilated, making them breeding grounds for disease.

In the middle stood the growing merchant and professional classes, whose fortunes were tied to the expanding empire and the industrial revolution. They lived in modest, but comfortable homes, often with access to better schooling and opportunities than the working class. However, the gap between these different social strata was rigid, and upward mobility was often difficult to achieve. Social norms dictated that a person’s position in life was largely determined by birth, and those born into the lower classes were unlikely to rise above their station, even with hard work.

Fashion in 1805 reflected these social distinctions, with the wealthiest members of society donning elaborate clothing, often made of the finest silks and wool, while the poor wore simpler garments made from rough, homespun fabrics. For men, the high collars and tailored waistcoats of the Regency era were in full swing, while women’s dresses were characterized by high waistlines and flowing skirts, inspired by the classical ideals of ancient Greece. The middle class often imitated the fashions of the aristocracy, though their clothing was more practical and less ostentatious.

Transportation in 1805 was slow and arduous by modern standards. The wealthy traveled in grand carriages, drawn by horses, often accompanied by servants. They could afford the luxury of long journeys, whether to London or to their estates. For the working class, travel was a rare and expensive luxury. The roads, poorly maintained and often impassable during bad weather, made even short journeys a significant hardship. Horses were essential for transportation, but the poor could only afford to walk or occasionally travel by cart.

The atmosphere in England during this time was one of uncertainty, particularly in rural areas like Sherfield English. The Napoleonic Wars loomed large in the minds of many, and the threat of invasion, while not immediate, was a constant worry. The air was thick with gossip and rumors, particularly surrounding the movements of the French and the strategies of the British navy. The Battle of Trafalgar, which took place in October of 1805, would be one of the most significant naval engagements of the century, but in the months leading up to it, the future seemed uncertain, and the outcome of the war was not yet clear.

Heating and lighting in 1805 were as much about survival as comfort. Wealthier homes might have multiple fireplaces, with servants constantly tending the fires to keep rooms warm. In poorer homes, however, a single hearth might be the only source of heat, and it was often difficult to maintain warmth during the cold winters. Candles, made from tallow or beeswax, were the primary source of light, though they cast little more than a faint glow. The poor often had to make do with whatever light they could scrape together.

Hygiene and sanitation were far removed from the standards we know today. Bathing was a rare event for most people, and many simply washed their hands and faces as best they could, but the idea of a daily shower was not even a distant dream. Public sanitation was rudimentary at best. Sewage often ran openly in the streets, and waste disposal was a problem that plagued both cities and the countryside. In the rural areas, people would often rely on wells and streams for drinking water, which could be contaminated with waste.

Food in 1805 was a simple affair for most people, with the diet largely based on bread, potatoes, and whatever vegetables could be grown in the garden or on the farm. Meat was a luxury enjoyed only by the wealthier classes, and even then, it was often salted or cured to preserve it. The poor might occasionally have a piece of pork or beef, but it was rare, and often their meals were more centered around stews or soups. Tea was a popular beverage, particularly among the middle and upper classes, though coffee was also enjoyed. For the working class, food could often be scarce, and meals were dependent on the harvest.

Entertainment in 1805 was a rare indulgence for most, with the wealthier classes enjoying theater performances, balls, and concerts, while the poor made do with whatever simple pleasures they could find. Pubs were common gathering spots in rural villages, and many evenings were spent socializing over a pint of ale. For children, the countryside provided ample opportunities for games and outdoor activities, though formal schooling was rare for the poor. Education, if it was provided at all, was often a privilege reserved for the children of the wealthy or those who could afford private tutors.

Religion played a central role in the lives of most people. The Church of England was the established church, and for the poor, church attendance was an important part of their weekly routine. The sermon was a space where ideas about morality, society, and government were passed down, and the church itself was a symbol of both community and authority. For the working class, religion provided comfort in the face of their struggles, while for the wealthy, it was often a marker of their social status.

Diseases were rampant in 1805, and with poor sanitation, outbreaks of illnesses like dysentery, tuberculosis, and smallpox were common. Medical knowledge was limited, and treatments were often ineffective or harmful. The rich could afford the best doctors, while the poor relied on herbal remedies or homegrown treatments. Life expectancy was short for many, and the specter of death from disease was a constant companion.

The environment, too, was being slowly shaped by the forces of industrialization. While the countryside in places like Sherfield English was still pristine and untouched by the factories that would soon dominate much of the landscape, the signs of change were already becoming visible. The smoke from the early factories and the expansion of coal mining were beginning to affect the air, and the landscape, though still green and lush, was on the brink of transformation.

In this world of contrasts, gossip flowed like a river, as it always does in close-knit communities. In the village of Sherfield English, as in every other corner of England, the lives of the rich and poor were often the subject of conversation, with every rumor and piece of news eagerly exchanged. It was in these stories, passed down through the generations, that the true spirit of the time was preserved.

As we look back on 1805, we see a world on the edge of transformation, a world that will soon be forever altered by the forces of industry, war, and social change. But in this moment, in this quiet corner of Hampshire, the lives of ordinary people like Louisa Roude are lived in the shadows of history, simple yet significant, as they go about their daily routines, unaware of the great changes that are on the horizon.

On Sunday, the 12th day of May, 1805, the village of Sherfield English stirred gently from its slumber, bathed in the soft glow of a spring morning. The air was cool, still kissed by the fresh scent of rain, and heavy with the delicate perfume of blossoms that fluttered in the breeze like whispered promises. The sky, a tender blue, stretched wide above a countryside that seemed to exhale a collective sigh of peace. The birds, blue tits, robins, finches, sang their songs from hedgerows and treetops, their melodies soaring and mingling with the rustling of leaves, as if the very earth itself was raising a prayer to the sky. In the meadows, the wildflowers had begun to unfurl, their petals glistening like jewels in the morning light, primroses, buttercups, bluebells, each one a fragile dancer swaying beneath the watchful gaze of a sky not yet bold with summer’s heat.

Children ran barefoot through the grass, their laughter echoing on the air, their small feet leaving footprints in the dew, weaving garlands of daisies and clutching ribbons for the village maypole. There was joy in every corner, a delicate sweetness in the air, for this was not yet the scorching heat of summer but the golden warmth that invited long walks down quiet lanes or idle hours spent among the first blooms of the garden.

And yet, amid this timeless spring morning, in a humble cottage tucked away among the hedgerows, a more profound beauty unfolded, gentle, eternal, and tender. William, now in his twenty-seventh year, stood near the hearth, his gaze fixed not on the world beyond the cottage walls, but on the miracle unfolding before him. His wife, Anstice, aged twenty-six, sat near the fire, her body still heavy with the weariness of childbirth, yet glowing with that quiet strength known only to mothers. In her arms, she cradled their third daughter, a newborn girl, pink and warm, still fresh with the breath of life. The soft, sacred sound of the infant’s tiny breaths filled the room, mingling with the crackle of the fire as Anstice gently whispered her name: Louisa Roude.

Louisa, my fourth great-grandmother, entered the world on this gentle spring day, not with the trappings of wealth or ease, but wrapped in the love of a family whose wealth was measured not in gold but in devotion. Anstice, familiar with the pains and joy of childbirth, had already borne two daughters, Mary and Sarah, and in that quiet strength, she knew well how to endure the ache of labor and cradle joy in the palm of her hands. She held Louisa close, her fingers tracing the tender curve of the newborn’s head, her own heartbeat steadying the rhythm of the moment. William, ever in awe, watched them both, his wife, the woman he had pledged his love to at Saint Leonard’s, and the child now cradled in her arms, a child who would carry his name, his hopes, his legacy.

In that single, sacred morning, as bluebells nodded their heads in the meadows and ribbons fluttered in the breeze, life took root once again. Louisa’s birth, quiet and serene, was a delicate act of renewal—a thread gently woven into the fabric of the Roude family, one that would stretch across generations, carrying with it her blood, her spirit, and her name into the hearts of those who would come long after.

Though her first cries were heard only by her parents and the flickering light of the hearth, the world outside seemed to pause in quiet reverence. The birds sang louder, the flowers bloomed brighter, the winds whispered softly, nature itself seemed to honor this new life, this child who, in time, would carry the soul of her family forward, leaving an imprint on the world just as the sun’s warmth imprinted the morning. In this simple, profound moment, Louisa began her journey, and with her, the unfolding story of a family whose echoes would ripple across the centuries.

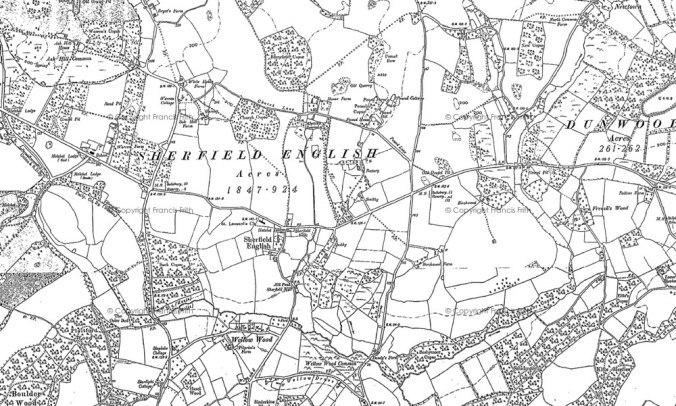

Sherfield English is a small village located in the Test Valley district of Hampshire, England. It lies just a few miles northwest of Romsey and is set within the picturesque Hampshire countryside, surrounded by farmland and natural beauty. The village has a rich history that spans several centuries and is deeply connected to the rural landscape of southern England.

The name "Sherfield" likely comes from Old English, where "scear" refers to a slope or hill and "feld" means open land or field, suggesting the village was established in an area with a prominent geographical feature. The addition of "English" to the name occurred later, distinguishing it from other similarly named places following the Norman Conquest of 1066.

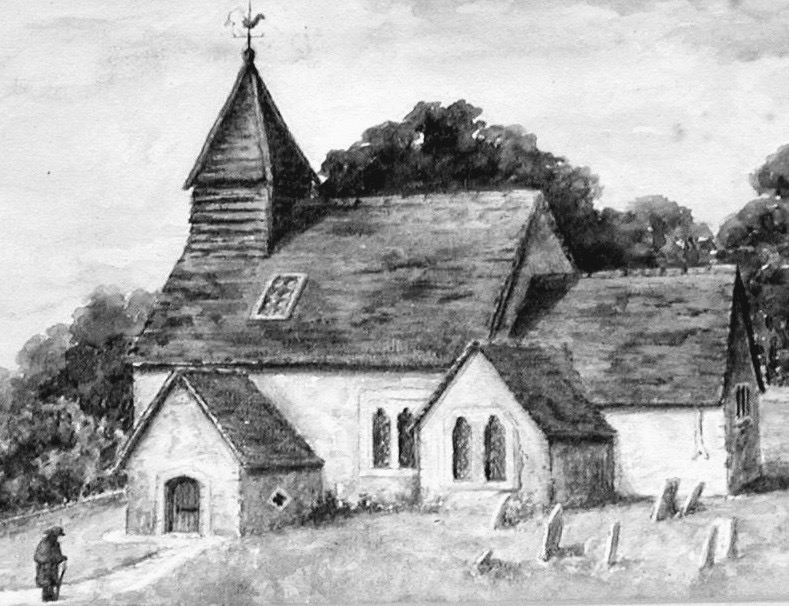

Sherfield English's development can be traced back to the medieval period, when it was primarily a farming community. The village's history reflects the broader agricultural heritage of Hampshire. It grew slowly but steadily, with most residents engaged in farming and agricultural work, a typical occupation for rural England at the time. The village’s centerpiece was the parish church, St. Leonard’s Church, which has served as a spiritual and social center for the community for many centuries. The church, with its origins dating back to the 12th century, is a key focal point of the village and reflects its long religious history.

In the 19th century, Sherfield English, like many rural areas, began to see changes brought on by population growth and the rise of industrialization. While the village remained largely agricultural, the expansion of transportation networks, particularly railways, brought new opportunities for trade and communication. This period also saw the construction of several cottages and houses in the village, leading to an increase in population.

The architecture of Sherfield English retains much of its historic character, with a mix of old cottages and larger homes. Despite the growth of nearby towns, the village has managed to maintain its rural charm and peaceful atmosphere, remaining a quiet, residential area. Its location, just a short distance from Romsey, offers a blend of tranquility and accessibility.

St. Leonard’s Church, at the heart of Sherfield English, has been integral to the community since its establishment. It was built in the 12th century, with subsequent renovations and expansions reflecting changing architectural styles and the evolving needs of the congregation. The church is dedicated to St. Leonard, the patron saint of prisoners and the mentally ill, and its role in the community has been central to the village's spiritual life. The churchyard around St. Leonard’s Church contains numerous gravestones, many of which date back several centuries, and the church remains an active site for worship, weddings, and other community events.

Sherfield English is also steeped in local folklore, and like many historic English villages, it has its share of ghost stories and rumored hauntings. St. Leonard’s Church, with its long history, is often the focal point of these tales. Some locals have reported strange occurrences in and around the churchyard, such as the sensation of being watched or hearing unexplained sounds like distant footsteps or murmurs. There are also stories about church bells ringing at night without anyone in the building to ring them, adding to the eerie reputation of the church. While these accounts remain largely anecdotal, they contribute to the village’s sense of mystery and intrigue.

In addition to the church, other old buildings in the village, such as historic houses and inns, are also said to be associated with ghostly activity. Some residents have claimed to see shadowy figures in certain rooms or have experienced cold drafts in areas of these older properties. These stories, while not officially documented, persist as part of the village's folklore and add to the character of Sherfield English.

Today, Sherfield English remains a picturesque and peaceful village, with a small but active community. The surrounding countryside offers opportunities for outdoor activities such as hiking, cycling, and birdwatching, making it an attractive location for those seeking a rural lifestyle while still being close to Romsey and other nearby towns. The village's historical charm, combined with its natural beauty and connection to local traditions, continues to make it a unique place to live and visit.

On Sunday, the 2nd day of June, 1805, the village of Sherfield English awoke beneath a soft, silvery light, as though the earth itself was stretching gently into the day. The rising sun, a tender orb, cast its golden haze over the fields where the dew still clung to the tall grasses and hedgerows, sparkling like scattered glass, each droplet a tiny prism reflecting the first whispers of dawn. Swallows, swift and graceful, darted low over the winding lanes, their wings a blur, their songs a gentle accompaniment to the distant toll of the church bell, calling the faithful to Saint Leonard’s for morning service.

From the thatched cottages, smoke curled upward in gentle spirals, a warm invitation to hearths already stirred in preparation for the day. The simple ritual of breakfast was underway, perhaps a bowl of porridge or the scent of fresh bread rising from the oven. Mothers, with careful hands and patient hearts, dressed their children in their finest clothes, brushing dust from hems, smoothing the linen, making sure each little one was presentable for the sacred day. Fathers, in well-worn coats, gathered prayer books with solemn reverence and shepherded their families along the narrow, winding paths leading to the cool stone of the churchyard.

The village moved slowly, its steps deliberate and steeped in the reverence of the day. The scent of wild roses and hawthorn wafted on the air, mingling with the low hum of bees already busy at work, gathering nectar from the blooms that kissed the morning’s light. The world, it seemed, exhaled in a peaceful harmony. For a few quiet hours, time seemed to slow, and the weight of the outside world fell away, leaving only the rhythm of tradition and faith.

But on this particular Sunday, there was something more, a deeper significance, a celebration, a new beginning. It was no ordinary Sunday for William and Anstice, for beneath the cool stone arches of Saint Leonard’s Church, their precious daughter, Louisa, was to be baptized. Born just weeks earlier, on the 12th of May, her arrival had already filled her family’s world with a new kind of light, a warmth and love that had woven itself into the fabric of their lives. The quiet, gentle joy of her birth had ripened into this sacred moment, the tender blessing of her baptism marking not just the beginning of her earthly life, but the start of her spiritual journey.

With the congregation gathered in the cool stone embrace of the church, the air heavy with the weight of centuries-old tradition, Reverend J. Wane stood at the altar, his voice steady and comforting as he spoke not only of scripture but of continuity, the unbroken chain that binds families to one another, to their faith, and to the land. It was a moment filled with the weight of generations, the touch of holy water a sacred link between past, present, and future.

Louisa, in the arms of her mother, her tiny form nestled against the warmth of Anstice’s chest, was gently welcomed into the Christian faith. The soft murmur of prayers filled the space, a sound as old and familiar as the village itself, and the gentle touch of holy water marked the beginning of her spiritual journey. In that moment, time itself seemed to pause, as if the world outside the stone walls of the church held its breath, honoring the significance of a new life, a new soul embarking on its path through this world.

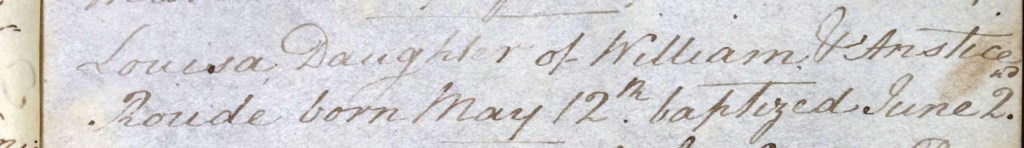

After the service, as the last prayer echoed through the cool stone walls, Reverend J. Wane carefully recorded Louisa’s details in the church register, the quill moving across the page with careful precision. He wrote the simple but profound words:

"Louisa, Daughter of William & Anstice Roude, born May 12th, baptized June 2."

These words, though they seemed like mere formalities, held the weight of love and legacy, marking not just the passage of time but the beginning of a new chapter in the life of Louisa, and in the lives of those who would carry her name and memory forward. In that small, timeless moment, her life, so tender and new, was woven forever into the fabric of her family, her faith, and the village that cradled her from the very start.

Saint Leonard’s Church in Sherfield English, Hampshire, has a rich history that stretches back over many centuries. The church has been a central part of the village’s religious and community life, and its history reflects the broader development of the area from medieval times to the present. The original Saint Leonard’s Church is believed to have been built in the early medieval period, likely during the Norman era, around the 12th century. The church would have been a simple structure, typical of rural churches of the time. As was common with churches in small villages, it was likely constructed with local materials such as stone and timber, with a simple design reflecting the needs of the local community. The church was dedicated to Saint Leonard, a popular saint during the medieval period who was often invoked for protection and for his association with prisoners and captives. Saint Leonard’s cult was widespread across England, and many churches were named in his honor. The original church at Sherfield English served as a focal point for the small agricultural community, providing a place for worship, social gatherings, and important life events such as baptisms, marriages, and funerals. The church would have also been a place where the villagers came together for communal activities, and it played an essential role in maintaining the spiritual and social fabric of the community. Over time, the church likely underwent several modifications and additions, particularly in the 14th and 15th centuries, as the village expanded and the needs of the local population grew. These changes were likely driven by the growing wealth of the parish as the agricultural economy strengthened. In the 19th century, however, the old church began to show signs of wear and was no longer able to adequately serve the growing population of Sherfield English. By the early 1800s, the church building had become dilapidated and was deemed inadequate for the needs of the parish. At this point, the decision was made to construct a new church to better serve the community. The new Saint Leonard’s Church was built in 1840, a year that saw the completion of many church restoration projects across rural England, driven in part by the Victorian era’s focus on reviving medieval architectural styles. The new church was built on a site adjacent to the old church, though some sources suggest that it may have been on the same footprint or nearby. The architect responsible for the design of the new church was likely influenced by the popular Gothic Revival style of the time, which was characterized by pointed arches, stained-glass windows, and spires. The new church was intended to accommodate the needs of the growing population of Sherfield English, and it was designed to be larger and more architecturally impressive than its predecessor. The construction of the new church was part of a broader trend of church building and restoration during the Victorian period, a time when many rural churches were being rebuilt or restored to reflect the prosperity of the period. The old Saint Leonard’s Church, after the new one was completed, was demolished, as was often the case with churches that were deemed structurally unsound or inadequate for modern use. It is common for older church buildings to be torn down when a new structure is built, particularly if the old building no longer meets the needs of the local population or has fallen into disrepair. It is likely that the materials from the old church were repurposed for the new construction, as was the custom at the time, though no records have definitively confirmed this. Today, Saint Leonard’s Church stands as a beautiful example of Victorian church architecture, with its stained-glass windows, pointed arches, and graceful tower. The church continues to serve the community, offering regular worship services, community events, and providing a space for reflection and connection. The church is also known for its picturesque setting within the village, surrounded by well-kept churchyards and the rolling countryside of Hampshire. The new church, while a product of the 19th century, retains the essence of the old church’s purpose to serve as a spiritual hub for the village of Sherfield English.

The surname Roud, often spelled as Roude, has its origins in England, and like many surnames, its history is rooted in the cultural and social dynamics of the medieval period. The surname is relatively rare and likely evolved from a combination of geographical, occupational, or descriptive factors.

The surname Roud is believed to be of Anglo-Saxon or Old French origin, with several theories regarding its development. One possibility is that it may have derived from a geographical location, such as a town or settlement named "Roud" or "Roude," which would have been based on a place name in early medieval England. This is a common source of many surnames, as people often adopted the name of the place where they lived or were originally from.

Another theory is that the surname Roud could be derived from a Middle English word "roud" or "rood," meaning a cross or a structure resembling a cross. This word would have been used to describe a place near a religious monument, such as a cross at a crossroads or a small church, often found in rural areas. If this is the case, the surname may have originated as a name for someone who lived near such a landmark or worked as a caretaker of it.

The variation in spelling, such as "Roude," could reflect changes in regional dialects and spelling conventions over time, as English orthography was not standardized until much later. The shift in vowel sounds and spelling was common as surnames were passed down orally and written differently depending on the scribe or the region.

As with many surnames, the name Roud would have been passed down through generations, and early bearers of the surname would have likely lived in rural communities or towns where such names were adopted based on occupation, location, or personal characteristics. The surname would have been relatively uncommon and might have been concentrated in specific areas, particularly in the southern or southwestern parts of England, though this can vary depending on migration patterns and historical records.

In terms of historical records, variations of the surname can be found in some early parish registers and tax records, but the surname Roud, or Roude, has not been widely documented in historical nobility or aristocracy. This suggests that the name was likely borne by common folk, particularly in rural communities, rather than by people of noble birth. It is possible that individuals with the surname Roud may have been farmers, laborers, or tradespeople, though there is no specific evidence linking the name to any particular occupation.

The name's presence in the historical record, however, is a reminder of the social structure of medieval and early modern England, where surnames often denoted a person’s origins, occupation, or relationship to a specific place. Over time, people with the surname Roud may have migrated, and the name may have spread across different regions of England and beyond, particularly during the periods of population movement and the expansion of the British Empire.

In modern times, the surname Roud or Roude is quite rare. However, it continues to be found among descendants who carry on the legacy of their ancestors, even if the surname has undergone slight variations in spelling or pronunciation. As with many older surnames, the historical context of Roud is shaped by its connection to the land and the people who lived on it.

The name Louisa is of Latin origin, derived from the male name Louis, which itself comes from the Old French Loois, a form of Clovis, which is derived from the Germanic elements hlod, meaning "fame," and wig, meaning "war" or "battle." Therefore, Louisa is often interpreted as "famous warrior" or "renowned in battle."

The name Louisa has a rich history in the United Kingdom, particularly as it became popular during the 18th and 19th centuries. While it is a feminine form of Louis, it was adopted widely as an independent name for girls, especially in the Victorian era. Louisa gained prominence as a result of its association with European royalty, where names like Louis and Louisa were commonly used. One of the most notable early bearers of the name in British history was Princess Louisa of Great Britain (1724–1751), the daughter of King George II and Queen Caroline. Her royal lineage contributed to the popularity of the name within British aristocracy and beyond.

The name Louisa became particularly fashionable during the 19th century, coinciding with the rise of the Romantic period, when classical and elegant names were highly favored. Writers, poets, and artists were often drawn to names with historical significance and a certain grace, and Louisa fit that ideal. One notable figure was Louisa May Alcott, the American author of Little Women, whose influence helped bring the name to wider prominence in English-speaking countries, including the UK. Though she was American, her works were widely read in the UK, and her character, Louisa, became synonymous with the name’s ideal of strength, femininity, and grace.

In the UK, Louisa became a popular name for girls from the 18th century onward, though it reached its height of popularity during the 19th century, a time when names with soft, melodic sounds were often chosen for daughters. The name had an air of refinement and nobility, partly due to its royal and literary associations, and it was often favored by middle and upper-class families. As was common during this time, many daughters were named after grandmothers, aunts, or other relatives, and Louisa, with its noble and literary connotations, became a popular choice for those seeking to continue a family tradition or honor a loved one.

In the 20th century, the popularity of Louisa as a name began to decline somewhat, but it has never disappeared entirely. It has remained a classic, timeless name that is occasionally revived in different generations, often chosen for its elegance, simplicity, and historical roots. The name Louisa continues to be used in the UK today, though it is less common than it once was.

The name Louisa, with its gentle yet strong sound, has a sense of dignity and grace that has helped it maintain its appeal for centuries. Whether through its royal associations, its literary legacy, or its classical roots, Louisa remains a name that evokes a sense of refinement, beauty, and history.

On Sunday, the 27th day of December, 1807, as the final days of the year settled quietly over Sherfield English, the village seemed to hold its breath, wrapped in the stillness of a winter morning. The pale, weak sun hung low in the sky, casting a soft, ethereal glow over fields hushed by frost, and the village lay beneath a blanket of cold silence, as if nature itself had paused to reflect. But inside a modest, fire-warmed cottage, nestled among the frosted hedgerows, the stillness was broken by the first cry of a newborn, sharp and clear, heralding the arrival of a new soul. It was Louisa’s newborn brother, James, whose small, fragile form brought with him the promise of life and renewal.

Within the warmth of the cottage, time seemed to stretch and pause, holding the moment with reverence. Anstice, though weary from the effort of childbirth, radiated a quiet strength. She cradled James to her chest, his tiny, fluttering heartbeat steady against the calm rhythm of her own. The love and bond between mother and child was palpable in the air, a tender thread woven in that sacred space between breaths. Beside them, William, Louisa’s father, stood near, his heart full, overcome with a quiet, awestruck joy. In his eyes, the miracle of life was reflected in the new baby, in the gentle, loving arms of his wife, and in the warmth of their humble home.

Though wealth did not fill their cottage, love and hope were abundant, filling every corner of the room. This was the kind of richness that could not be measured in coins or fine things, but in the moments of tenderness and the promise of a future yet to unfold. In the quiet hum of the hearth, amid the frost-kissed world outside, the Roude family embraced the miracle of new life, and the winter morning became one not just of endings, but of beginnings, as hope was once again born anew in their hearts.

On Sunday, the 31st day of January, 1808, a pale winter sun cast its soft, muted light through the windows of Saint Leonard’s Church in Sherfield English, the quiet rays touching the cold stone walls and illuminating the sacred space with a serene, almost ethereal glow. Within the church, a tender and solemn moment unfolded, a moment that would be woven into the very fabric of the village’s history.

Louisa’s brother James, the infant son of William and Anstice Roude, who had been born just weeks earlier on the 27th of December, 1807, was brought to the altar for his baptism. In the arms of his mother, Anstice, who had already borne the quiet joy of motherhood once again, James was cradled with all the tenderness a mother could offer. Surrounded by the quiet reverence of family, friends, and the steady presence of community, the small babe was received into the Christian faith, a ritual that echoed through the centuries, one that tied him, in that fragile moment, to the enduring tradition of his ancestors.

The baptism was performed by the devoted Rector, J. Wane, whose gentle, steady hand offered the blessing of faith. His voice, low and filled with the weight of years, filled the cool church air as he spoke words of hope and grace over the newborn child. And as the sacred water touched his brow, James's journey into the arms of the Christian community began, the quiet reverence of the ceremony enveloping him in warmth and sanctity.

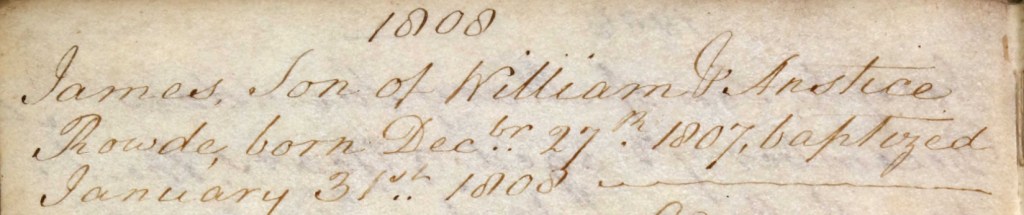

After the ceremony, with care and precision, Reverend Wane inscribed the sacred event into the church register for Sherfield English, each word marking the beginning of James’s life in the eyes of both God and community.

"James, Son of William & Anstice Rowde, born Dec 27th, 1807, baptized January 31st, 1808."

With those simple words inked on the page, James’s life became an indelible part of the parish’s long and storied history, his name forever etched in the records of those who had come before him and those who would follow. In a church that had witnessed centuries of baptisms, weddings, and farewells, this gentle beginning was one more thread in the intricate tapestry of faith and community.

Louisa, spirit seemed to hover in the air that day. Though she was not the focus of the ceremony, her presence was deeply felt. Louisa, who had only just turned three, had witnessed the arrival of her brother into their world with wide, curious eyes and an open heart. She was a quiet witness to this sacred moment, perhaps not yet able to fully grasp its significance, but surely feeling the weight of it in the warmth of her mother’s arms and the reverent hush of the gathered congregation.

she was the silent witness, the loving sister whose spirit would forever be woven into the tapestry of her brother’s life. Her own journey, though young, was already so intertwined with his. Her presence, filled with love and the gentle grace of a child, made this baptism not just a sacred rite for James, but a moment that marked the continuing unfolding of a family’s story, one that was rooted in love, faith, and the deep connection between them all.

In the quiet of that winter day, as the last of the candles flickered low, the church became a place not only of worship but of remembrance. For in this sacred space, Louisa's story, and the story of her family, was being inscribed with every whispered prayer, every loving touch, every baptism, and every solemn moment shared within these walls.

As the small congregation gathered their coats and left the warmth of the church, the sun outside was low in the sky, casting long shadows across the snow-dusted ground. But within Saint Leonard’s, there was only light, a soft, enduring light that shone in the quiet grace of a child’s baptism, a sacred beginning in a place that had held so many before, and would continue to cradle the lives of many more.

On Tuesday, the 29th day of October, 1811, as autumn leaves drifted softly to the ground, the village of Sherfield English seemed to hold its breath beneath a sky brushed in the rich hues of evening. The air, crisp with the promise of winter, carried the scent of earth and fallen leaves, yet within the humble cottage of the Roude family, the warmth of the hearth did little to ease the tension that filled the room. Louisa’s mother Anstice, aged 32, labored through the long hours of the day, her breath shallow and her hands gripping tightly at the edge of the bed. Each wave of pain came like a tide, fierce and unyielding, her body trembling, her face pale but determined.

At her side stood William, her devoted husband, 34 years old, his presence a steady anchor in the midst of the storm. His rough hands were damp with worry, and his eyes, filled with helplessness, never left her. He whispered reassurances to her, though the pain was too great for words to soothe. His gaze, full of love and concern, sought to offer what little comfort he could, but it was the strength of Anstice that carried them both through those long hours.

As the day turned to dusk, and the last light of the autumn sun gently faded over the hedgerows, a cry broke the stillness, rising clear and pure into the quiet evening air. The struggle was over, and Louisa's newborn brother, William Roude, had arrived. In that moment, all the pain and tension melted into awe. Anstice, weak but radiant, cradled her son against her chest, the warmth of his tiny body a precious comfort against the chill of the evening. Tears slipped down her cheeks, not from sorrow, but from the overwhelming wave of love that filled her heart.

Nearby, Louisa, now six years old, stood close, her wide eyes full of wonder as she gazed upon the tiny figure in her mother’s arms. Her face, still so young but already full of the quiet wisdom of a child who had witnessed both the joys and the struggles of family life, was awash with a quiet tenderness. She reached out with small, hesitant hands, her heart swelling with love for this new brother, this new piece of her world. Though she was still a child, Louisa understood, perhaps more than her years should have allowed, the delicate miracle that was unfolding before her. In that moment, her world expanded, her role within their family deepened, and the fierce bond of siblinghood began to form, as delicate and precious as the newborn babe before her.

William, overcome with the raw miracle of birth, knelt beside them, his heart swelling with love for both Anstice and the newborn child. The cottage, simple and weather-worn, had never felt so full of life, so full of love. The soft crackle of the fire seemed to echo the pulse of the new life that had entered their world. Outside, the night air was still, as if the earth itself had paused to honor this fragile moment.

As the evening stretched on and the warmth of the fire filled the room, Louisa, her gaze never straying far from her newborn brother, took in the sight of her mother holding him so gently, her own heart brimming with newfound understanding. She knew, even at her tender age, that a new chapter had begun, one that would forever weave her into the life of her brother, William. In the quiet glow of that autumn evening, amid the soft sigh of the hearth and the silent hum of the world outside, the Roude family was once again made whole, and Louisa, with her growing heart, stepped further into the story of their shared love, their shared life.

On Sunday, the 26th day of January, 1812, the quiet stillness of Saint Leonard’s Church in Sherfield English seemed to hold its breath, wrapped in the weight of centuries of tradition and faith. The cold winter air outside contrasted with the warmth that lingered inside, where flickering candlelight cast soft shadows on the ancient stone walls, and the scent of aged wood mingled with the sacred quiet. It was here, beneath these timeless arches, that Louisa’s parents, William and Anstice, brought their infant son, William, to be baptised, a tender moment marking the first step of his spiritual journey.

Born on the 29th of October the previous year, little William had spent his first winter cradled in the warmth of his family’s modest cottage, his tiny life nurtured by the love and care of his parents, and the tender attentions of his older siblings, including Louisa. Now, as the congregation gathered in hushed reverence, his name would be spoken before God, before his community, and before the family who had already poured so much love into his small life. Louisa, now six years old, stood by her parents’ side, her young face soft with curiosity, her wide eyes reflecting the gravity of the moment. Though her understanding was still that of a child, there was something deep in her heart that felt the sacredness of the occasion, and she knew that her brother was taking another step toward belonging, not just to their family, but to something far greater.

The cool baptismal waters, held in the silver font, were poured gently over William’s brow by the rector, a steady hand whose voice echoed through the stone walls as he spoke words of blessing, invoking faith and protection over this new life. The water, both cool and sacred, marked the beginning of William’s spiritual journey, an act that would forever tie him to the generations before him and those yet to come. Louisa, her hand perhaps resting on her father’s arm, watched with a quiet reverence as the ritual unfolded, the importance of it settling in her heart as she stood, silently proud of the brother whose name was now etched in the sacred history of the church.

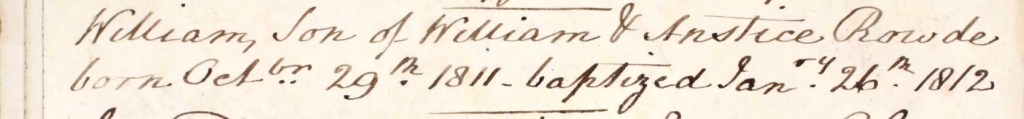

After the baptism was completed, the rector carefully inscribed the sacred moment into the parish register, the quill flowing across the paper with deliberate care.

"William, son of William and Anstice Rowde, born Octbr 29th 1811 baptized Janry 26th 1812."

Though the surname was written slightly differently, Rowde instead of the usual Roude or Roud, it was still unmistakably theirs, a small variation that could never diminish the significance of the day. The name, like the child it belonged to, was part of a larger story, a story that had begun long before William’s birth, and one that would stretch far beyond it, as the threads of time wove their way through the Roude family. In that hallowed space, amid whispered prayers and flickering candlelight, William was received into faith, and his place in the family’s unfolding narrative was gently sealed.

For Louisa, the baptism of her brother was a moment not just of witnessing a sacred rite, but of feeling the subtle, profound weight of family and faith drawing them all closer together. The day’s significance would remain with her, etched into her memory, as she stood beside her parents,her gaze filled with a tender love for the brother she would watch grow, always a part of this family, always tied to the legacy of those who had loved him from the moment of his first cry.

In the soft unfolding of spring in the year 1814, as the hedgerows of Sherfield English burst into bloom and the fields began to stir with new life, the village seemed to awaken in harmony with the season. The air, fresh with the scent of wildflowers, carried a sense of renewal, and beneath the pale blue sky, the Roude household too was blessed with the sweetest of arrivals. Within the weathered walls of their modest Hampshire home, Louisa’s mother, Anstice, aged thirty-six, labored through the quiet hours of the day, her breath steady, her heart full with the anticipation of a new life.

As the sun dipped low, casting a golden glow over the cottage, Anstice gave birth to a daughter. They named her Hannah. The name, like a familiar refrain, had echoed through the generations of the Roude family. Perhaps it was chosen in honor of William’s own mother, also named Hannah, or perhaps it was a tribute to his sister. The name held deep significance, a thread woven through their family’s history, and now, that thread would live on once more, cradled in the tiny, fragile form of this new life.

Hannah, with her downy hair and the sweet, tender cry that filled the whole cottage, brought a new sense of purpose to the home. Louisa, standing at her mother’s side, gazed with wide, soft eyes at the tiny sister now resting in her mother’s arms. There was a quiet, unspoken understanding in Louisa’s gaze, a recognition of the deep bond that would form between them. In that fragile moment, the family grew once again, and with the arrival of Hannah, their world expanded, not just with a new mouth to feed, but with a new heart to love.

The name “Hannah” had now been passed down through time, its significance far beyond the simple syllables. It carried with it the weight of legacy, of love, of generations that had lived and loved before, and now, it would find its home in this new child, whose presence brought a sense of continuity, of remembrance, of connection. In the warmth of the cottage, with the quiet hum of the world outside, the Roude family was reminded once again that life, like the seasons, was in a constant state of renewal, of endings and beginnings, of names that lived on through the passing years.

As the days stretched on and the soft warmth of spring enveloped their little home, Louisa, now with her own tender understanding of the world, watched as her family grew yet again. She could feel it in the very air of the cottage, a new purpose, a new joy, cradled in the arms of her mother, in the tiny hands of her new sister. The arrival of Hannah was more than just the birth of a child, it was the continuation of a story, a shared thread in the tapestry of their lives, a gentle reminder of the love that would always bind them, across time and generations.

On Sunday, the 29th day of May, 1814, in the gentle warmth of late spring, when the air carried the scent of fresh blooms and the days stretched long with the promise of summer, the stone walls of Saint Leonard’s Church in Sherfield English once again bore witness to a sacred and joyous moment. The village, quiet and humble, seemed to hold its breath as Louisa’s sister, Hannah, was brought lovingly to the font. Her small, fragile life, so new and full of promise, was now cradled in the arms of faith beneath the vaulted silence of the ancient church.

The Roude family’s abode, simple and modest, nestled among the green fields of Hampshire, stood in quiet contrast to the significance of the day. Their home, a place of warmth and love, was a far cry from the grand stone edifice where, on this holy morning, Hannah would be received into the Christian faith. This baptism marked not just the beginning of her spiritual journey, but her entrance into a long-standing community of faith and tradition that had sustained generations before her.

William, their father, a labourer by trade, stood with quiet pride and reverence as he watched the rector, John Wane, pour holy water upon Hannah’s brow. The water, cool and sacred, seemed to carry with it not only the blessings of the church but the hopes of her parents for the life that lay ahead. It was a simple, beautiful moment, one marked by the silent prayers of a father who, though humble in occupation, understood the depth of the occasion and the lasting impact of this ritual.

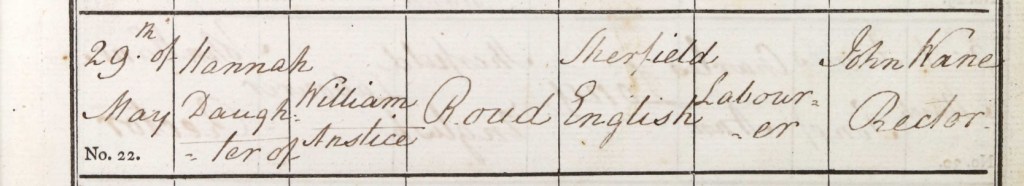

As the ceremony came to its gentle close, Rector Wane, with steady hand and deep respect for the sacredness of the moment, carefully recorded the details in the official parish register. His quill, dipped in ink, moved steadily across the page, capturing the significance of this day for posterity.

BAPTISMS solemnized in the Parish of Sherfield-English in the County of Hants, in the Year One thousand eight hundred and fourteen.

No.: 22

When Baptized: 29th of May

Child’s Christian Name: Hannah, Daughter of

Parents Names: William and Anstice Roud

Abode: Sherfield English

Quality, Trade, Profession: Labourer

By whom the Ceremony was Performed: John Wane, Rector.

With these simple but profound words, the quiet, tender moment of Hannah’s baptism was recorded, her name now woven into the tapestry of Sherfield English’s history. It was a moment of deep meaning for the Roude family, a step not only for Hannah but for the legacy of their faith. In the flickering candlelight of the church, amid whispered prayers and the sacred echo of the rector’s voice, a new life had been marked, and the Roude family’s story continued to unfold, one chapter at a time, beneath the sheltering arms of tradition and love.

In the enchanting days of early spring, 1817, when the last chill of winter finally yielded to the soft warmth of the sun and the first buds of blossom unfurled against the still-cold earth, the village of Sherfield English seemed to hold its breath. The hedgerows stirred once more with birdsong, and the promise of renewal hung in the air like the faintest of dreams. It was in this season of quiet rebirth that Louisa, her parents William and Anstice, and her siblings, who already filled their humble cottage with the laughter, the bustle, and the warmth of family life, welcomed yet another new soul into their fold.

They named her Eleanor, a name as gentle on the tongue as a soft spring breeze, graceful in its cadence, and imbued with a timeless strength that spoke of quiet resilience and enduring beauty. Eleanor, though still so small, would carry that strength with her, just as the name would carry the echoes of those who had come before.

The Roude cottage, though worn by the years and the steady march of seasons, glowed with life that spring. The fire in the hearth crackled gently, its warmth a constant companion against the lingering bite of early spring’s coolness. The walls, which had witnessed the full range of human experience, laughter, tears, lullabies, and whispered prayers, now stood once again as silent witnesses to the miracle of new beginnings. Eleanor Roude, born in the still-cold air of March or April, was cradled in that familiar space, not the first child to be rocked in the cradle beside the fire, but in that moment, the very centre of their world.

Though the cottage was modest and their lives filled with quiet struggles and simple joys, there was no measure of wealth or renown that could surpass the richness of the love that bound them together. Each new life that entered that home was a testament to the enduring bond that connected parent to child, sibling to sibling, and each generation to the one before it. The Roude family, though not marked by fortune or outward acclaim, was rich in something far more profound, the deep, enduring love that passed from hand to hand, from heart to heart, through the turning of seasons and the lengthening of years.

As the world outside blossomed, so too did the Roude family grow, not in outward wealth, but in the quiet strength of their connections. Each day was a small, sacred unfolding, marked not by grand events, but by the steady pulse of love, the gentle rhythms of family life, and the beauty of a world that, though ever changing, remained rooted in the timeless cycle of renewal. And in the stillness of that spring, as the birds sang their praises and the earth itself seemed to breathe again, the Roude family embraced the promise of a new beginning, cradling their little Eleanor in their arms as the seasons turned, carrying them gently forward into the future.

On Sunday, the 18th day of May, 1817, as spring unfolded gently across the Hampshire countryside, painting the world in soft hues of green and gold, Louisa’s sister Eleanor was carried to Saint Leonard’s Church in the heart of Sherfield English. The air was fragrant with the bloom of wildflowers, and the gentle hum of the village seemed to fade as the family entered the sacred space. Inside the church, the stillness of the sanctuary enveloped them, broken only by the quiet murmur of prayer and the faint rustle of the family’s movements. Here, beneath the ancient stone arches, Rector John Wane welcomed the Roude family to the baptismal font, where they would mark the beginning of Eleanor’s spiritual journey.

Wrapped in a simple gown, Eleanor, so small and fragile, blinked up at the flickering candlelight, her wide eyes taking in the world with the innocence of one just beginning to experience it. The holy water, cool and sacred, was gently poured upon her brow, and in that moment, she was received into the faith of her ancestors. The significance of the ritual, though quiet, was immense, her place was now secure, not just in her family, but within the community of believers who had gathered here, within the unbroken line of tradition that spanned generations.

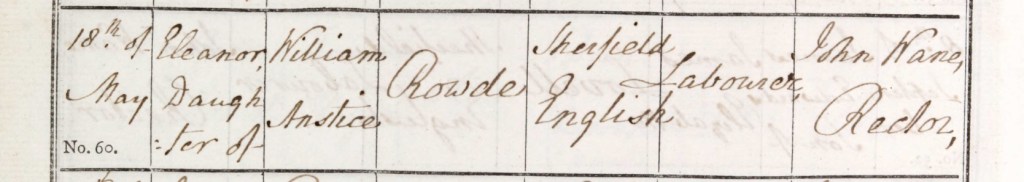

Rector Wane, with the grace and solemnity of his calling, recorded the baptism in the parish register, the quill moving carefully across the paper, preserving for all time this small but sacred moment.

BAPTISMS solemnized in the Parish of Sherfield English in the County of Hants in the Year One thousand Eight hundred and Seventeen.

No. 60

When Baptized: 18th of May

Child’s Christian Name: Eleanor

Parents' Names: William and Anstice Rowde

Abode: Sherfield English

Quality, Trade, or Profession: Labourer

By whom the Ceremony was Performed: John Wane, Rector.

But then, as the ink dried on that sacred line, Eleanor seems to vanish from the pages of history.

There is no further record of her, no marriage, no burial, no trace in the census returns or any surviving parish documents. Her name appears just once, in that single line of ink, and then the pages fall silent around her.

What became of Eleanor? That is a question suspended in time, a mystery that lingers in the space between memory and oblivion. Did she die young, her burial lost or unrecorded, fading into the margins of forgotten lives? Was she taken in by another family, her name altered or even forgotten in later records? Or perhaps she lived quietly, her story simply never written down, never passed along, her existence erased by the passage of time.

For now, her name is a delicate thread, one that only appears once in the story of her family. But though she is lost to the official records, Eleanor’s presence lingers, held in the hearts of those who loved her. What we know is this: she was loved. She was blessed. She was cradled in her mother’s arms, gazed upon by her father with pride, and welcomed into the fold of her faith beneath the same roof where generations of her kin had stood before her. She was, in those fleeting moments, as real and cherished as any other child born into the Roude family.

And so, as long as her name is spoken, and her story, however incomplete, is sought with care, Eleanor Rowde has not been lost. She remains part of the tapestry of the Roude family’s enduring history. She is remembered in the spaces between the lines, in the silence that calls out for answers, and in the hearts of those who, though they may never know the full story, carry her name forward through time.

Within the quiet village of Sherfield English, where the fields rolled softly beneath the pale green veil of late spring, the humble cottage of the Roude family was once again lit from within, not merely by the flicker of candles but by the quiet miracle of new life. It was the year 1820, and the days had begun to lengthen, casting warm light over the village as Louisa’s mother, Anstice, now forty-one, labored through the hours of birth. In the stillness of that moment, another child was brought forth, an infant son, small and fragile, yet full of the promise that new life always brings.

This baby boy, cradled in his mother’s arms, was born into a life steeped in the simple, sacred rhythms of family, faith, and the earth. His name, Henry, was not given in ceremony, but in the quiet, sacred stillness of the home that had cradled so many before him. His name was spoken by Anstice, her voice low with the weight of love, as his father, William, stood close, his heart swelling with quiet pride, as he gazed upon the newest addition to their family.

Outside, the world moved on as it always had, the hedgerows bloomed in a riot of color, the larks soared high above the fields, and the gentle hum of the village continued. The earth beneath their feet turned in its steady, timeless rhythm, indifferent to the small miracle unfolding within the cottage. But within those weathered walls, time seemed to pause. There, a name had been given, a name that would carry with it the love of a mother and father, and the quiet strength of a family deeply rooted in the soil of Sherfield English.

Henry, a name carried forth on the breath of love, into the waiting story of the Roude family, a story shaped by generations of hard work, deep faith, and a love that only deepened with each new life that came into the fold. In that tender moment, as Anstice cradled Henry close and William stood by her side, the world outside faded away. For in the quiet of that spring afternoon, a new life had begun, and with it, a new chapter was written in the book of the Roude family, a chapter full of quiet, enduring love and the promise of all that was to come.

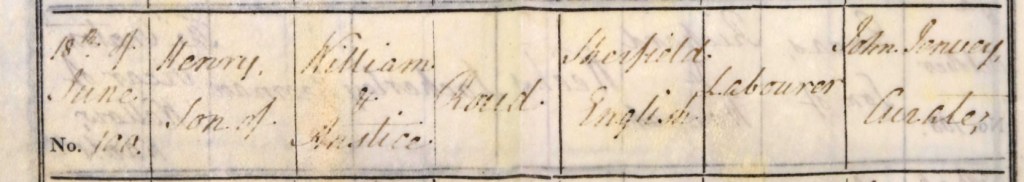

On Sunday, the 18th day of June, 1820, beneath the familiar arches of Saint Leonard’s Church in Sherfield English, the Roude family gathered once again to welcome new life into the fold, surrounded by the quiet reverence of their village. Louisa’s youngest brother, Henry, was carried gently to the baptismal font by his parents, William and Anstice. His tiny form was wrapped in soft linen, his eyes wide and curious, taking in the dappled light that filtered through the tall windows, casting a serene glow across the ancient stone of the church. The world outside, vibrant with the fullness of summer, seemed to pause for a moment as this small life was embraced by faith and family.

The summer hedgerows, thick with bloom, lined the churchyard, and the air was filled with the scent of warm earth and ripening wheat, a season of life in every sense, a time when nature itself seemed to echo the arrival of new beginnings. William, a labourer by trade, stood with a quiet, grounded strength, his presence as steady as the years of hard work that had shaped him in the fields surrounding their village. Anstice, by his side, carried both joy and a quiet weariness in her gaze, the love of a mother who had known both the sweetness and the fragility of life. Her heart was full as she gazed at Henry, the new life she had brought into the world, a little boy whose future now seemed to shine with possibility. Louisa and her siblings, standing nearby, looked on with pride and unwavering love, their faces bright with the joy of this sacred moment.

The ceremony was performed by John Irwin, the curate of Saint Leonard’s Church, whose voice filled the space with a tenderness befitting the occasion. He spoke Henry’s name with care, as if sealing it into the history of their family and village, before baptizing him in holy water. With each drop, Henry was received into the faith of his ancestors, bound now not only by blood but by the traditions of those who had come before him. The quiet, sacred ritual was recorded in the parish register with a few simple yet profound words:

BAPTISMS solemnized in the Parish of Sherfield English in the County of Hants in the Year One thousand eight hundred and twenty.

No. 120

When Baptized: 18th of June

Child’s Christian Name: Henry

Parents' Names: William and Anstice Roud

Abode: Sherfield English

Quality, Trade, or Profession: Labourer

By whom the Ceremony was Performed: John Irwin, Curate.

And with those few words, written in ink now gently fading with the passage of time, another chapter in the life of a humble village family was tenderly preserved for generations to come. In the simple, sacred act of baptism, Henry’s name was not only spoken, but etched into the ongoing story of the Roude family, a story shaped by love, faith, and the steady rhythm of life in Sherfield English. Each name inscribed in the register, each moment marked with care, formed the quiet legacy of a family whose lives, though modest in measure, were rich with love and purpose. Through these words, through this moment, Henry’s place in that history was forever secured, his story now part of a tapestry woven through the years.

At just nineteen years old, Louisa’s sister Sarah's life was tragically cut short, a cruel reminder of the fragility of youth in an era where illness, accident, or the quiet fading of life too often claimed the young. Whether it was a fever that took her, a sudden accident, or the slow, unnoticed decline that so often stole lives in those years, the cause of Sarah's death remains lost to time, as does the exact date of her passing. Yet, despite the lack of detail, the sorrow that followed her loss was no less profound, for the absence of a child, a sister, a friend, leaves a wound that no record can capture.

The passing of Sarah Rowde in the summer of 1822 cast a long, haunting shadow over her family’s modest cottage in Sherfield English. Within the walls that had once echoed with the warmth of her laughter, there would now be silence where her voice once rang. The chair where she had sat, perhaps by the hearth or at the table, would remain empty, the spaces she once filled left still and untouched. The work she had left unfinished, her tasks set aside, became quiet reminders of what could have been. In the kitchen, the garden, the quiet corners of their home, her absence would have been felt deeply, like an ache that lingered in the very air they breathed.

For Louisa, the loss of Sarah was especially hard to bear. As the elder sister, Sarah had always been a figure of strength and guidance in Louisa’s life, someone to look up to with quiet admiration. Louisa, still a young girl herself, had often turned to Sarah for support, for wisdom, for comfort. Sarah had not only been her sister but also a companion and caretaker, helping their mother, Anstice, with the younger siblings, sharing in the care of their home and family. Louisa would have looked to Sarah for guidance in the day-to-day tasks, the small routines of life, whether it was gathering the firewood, helping with the washing, or simply offering a kind word when the weight of the world felt heavy.

With Sarah gone, Louisa’s world felt suddenly smaller, quieter, the space where her sister had been a comforting presence now painfully hollow. She would have felt the loss in every corner of their home, in every moment when she reached out for Sarah’s hand, only to find it no longer there. No longer would Sarah’s gentle voice fill the quiet, nor would Louisa be able to rely on her sister's steady presence as they grew up together. The shared moments of sisterhood, the small smiles across a room, the whispered secrets, were now gone.

Though Sarah’s name may now be unspoken in the records of time, she was far from forgotten. Her memory lived on in the hearts of those who loved her, her parents, her siblings, and all who had known the warmth of her presence. Louisa, too, would carry the loss of her sister in the quiet spaces of her heart, in the moments where she would have expected Sarah’s voice, her laughter, her companionship. The love that bound Sarah to her family did not vanish with her passing; instead, it became an invisible thread, woven into the fabric of their lives.

In the years that followed, as the family grew and life moved forward in the unrelenting way it does, Sarah’s memory would remain an unspoken presence, woven into the family’s story even though time had washed away the details. She had been loved, and in that love, she was carried forward, not in the records of history, but in the lives of those who remembered her, in the small, quiet ways that a life continues long after it has passed. For Louisa, Sarah would always be more than a name in the past, she would be a sister, a guide, and an enduring presence in the quiet corners of her heart.

On Tuesday, the 30th day of July, 1822, a solemn stillness settled over Saint Leonard’s Churchyard in Sherfield English as Louisa’s sister, Sarah Rowde, was gently laid to rest. The warm summer air, which had once carried the hum of life, now seemed heavy with grief, and the world around the churchyard stood still. Birdsong no longer filled the air, nor did the breeze carry its usual comfort. Instead, a silence had taken root, one that could not be soothed by the gentle rhythm of nature. Sarah’s passing had left an emptiness that reached deep into the very heart of their family’s home, a silence that could not be filled.

Born into the humble embrace of a labourer’s family, Sarah had known the simplicity and strength of village life. Her days had been shaped by the changing seasons, by the steady rhythm of work in the fields, and by the quiet beauty of the hedgerows that framed her world. She had lived a life defined by quiet resilience and love, a life woven into the fabric of her family, the land, and the village itself. But her death, as so many did in those fragile years, had come too soon, cutting short the promise of a future that could never be realised.

Though her time was brief, Sarah’s presence had left an indelible mark on Louisa, on her siblings, on their parents, and on the community that had watched her grow from a child into a young woman. Her laughter, her kindness, and her quiet strength would be remembered long after she was gone. Yet, on that summer day, as Louisa stood beside her sister’s grave, it was impossible to imagine a world without Sarah in it. The grief was overwhelming, suffocating, a heavy weight Louisa did not know how to carry. She had never felt emotions so deeply fierce, so all-consuming.

As Sarah was lowered into the earth beneath the gently swaying trees, Louisa’s heart ached in ways she had never known before. She had never seen the devastation of loss so clearly, so plainly, in the faces of her parents. Her mother’s eyes, filled with an unspoken sorrow, and her father’s stoic expression, so full of quiet pain, left Louisa unsure of how to move forward. How could she help them? How could she stand strong, be the steady presence they so desperately needed, when her own heartbreak consumed her every hour? How could she pretend to be the pillar of support when the weight of grief was so much heavier than she had ever imagined?

She stood there, struggling to hold back tears, torn between the desire to be strong for her family and the realisation that she was breaking inside. She had always looked to Sarah for strength, for guidance, for companionship. Now, in the midst of this unimaginable loss, Louisa had no one to turn to, no sister beside her to offer a comforting word or a quiet smile. The grief felt like a chasm, one she couldn’t cross, one that seemed to swallow everything around her.

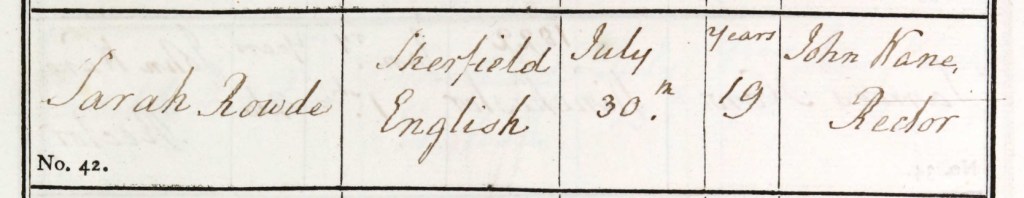

In the parish register, under the section for BURIALS in the Parish of Sherfield English in the County of Hants in the Year One thousand eight hundred and twenty two, there was the simple record of Sarah’s death, a few words that marked the end of her life but could never truly capture the depth of the sorrow that followed her passing.

No. 42

Name: Sarah Rowde

Abode: Sherfield English

When Buried: July 30th

Age: 19 years

By whom the Ceremony was performed: John Wane, Rector.

But for Louisa, this record was not just a name, a date, or an age, it was a reminder of the sister she had lost, of the future that would never be, and of the heavy burden of grief that she would carry with her always. As she looked down at Sarah’s grave, the world seemed to hold its breath, and Louisa was left alone with the weight of loss, unsure how to carry on, unsure how to heal. The absence of her sister would echo through every corner of her life, a reminder that some wounds never truly fade. But in the quiet, in the moments where the world stood still, Louisa would remember Sarah, not just as a name in a register, but as a sister, a friend, and a part of her heart that would remain with her always.

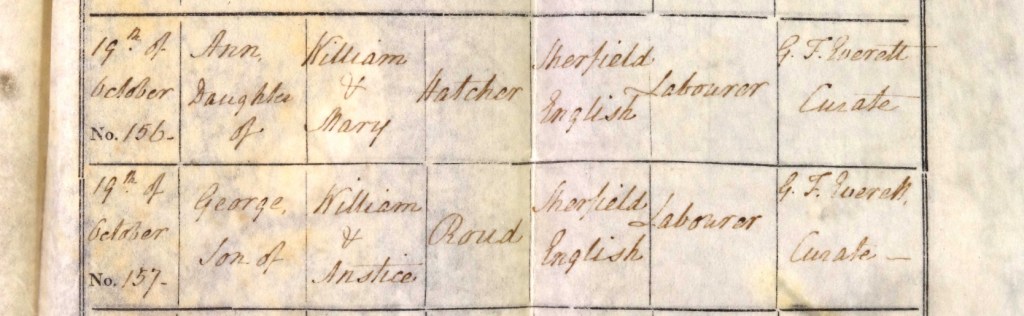

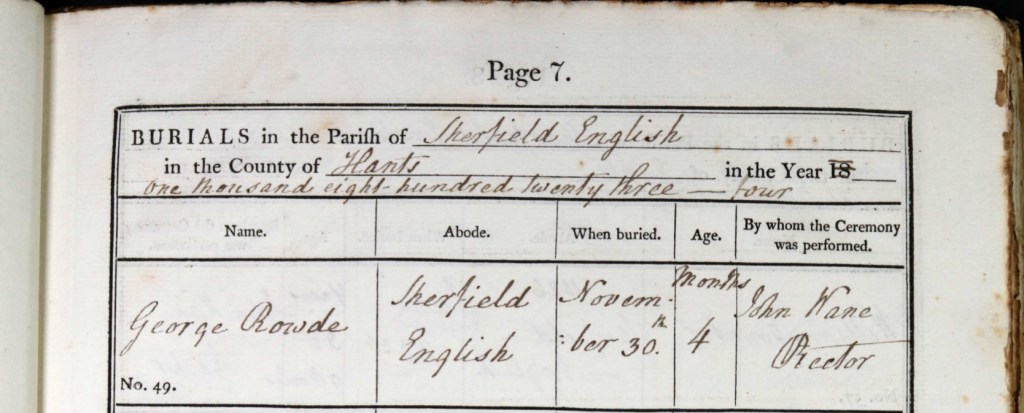

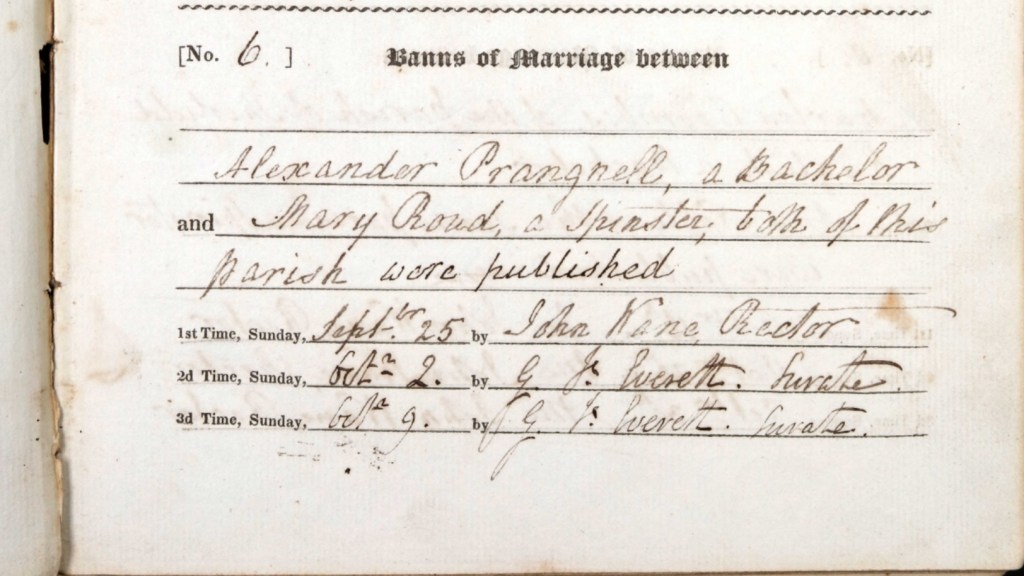

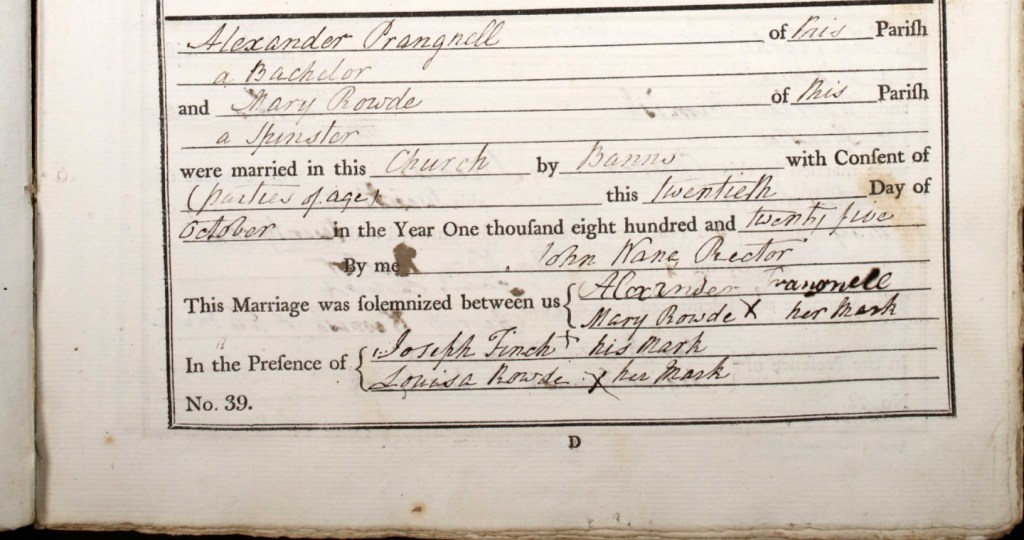

Under the mellow golden light of autumn, on Sunday the 19th day of October, 1823, Louisa’s baby brother George was brought forward to be baptised at Saint Leonard’s Church in Sherfield English. The trees along the village lanes had begun to turn, their leaves drifting softly down onto the foot-worn path that led to the ancient church door. Inside, the familiar stone walls were filled with warmth from family gathered in reverence, and the sacred ritual of baptism began to unfold. George, cradled lovingly in his parents’ arms, was carried to the font, symbolic of new life and sacred beginnings. His tiny form, fragile and innocent, was baptized by Curate G. F. Everett, who spoke his name with solemn care and gently marked his forehead with holy water.

Louisa felt her heart swell with quiet joy, knowing that this new chapter, this new life, would bring healing to their family, still scarred by the loss of Sarah.

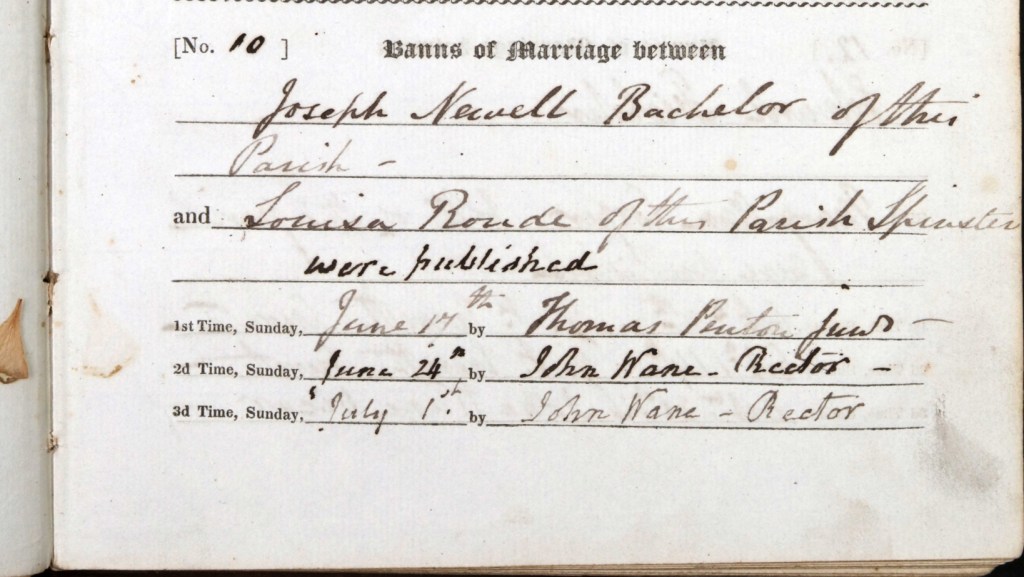

Yet George was not baptised alone that day. His cousin, Ann Hatcher, the daughter of William and Mary Hatcher (née Roud), William being their father’s sister’s son, stood beside him at the font. This was not merely a baptism but a gathering of generations, a family moment elevated by the sacred ritual. Two cousins, side by side, were blessed beneath the same roof of faith, a powerful symbol of continuity, of family, and of the ties that bound them all.

In this shared moment, two branches of the same rooted tree reached toward the future. Ann, born to Mary, once a girl who had run barefoot through these very fields, now stood as a mother, her daughter’s baptism a living testament to the strength of their family’s bond. For William, seeing his sister’s child and his own newborn son blessed in the same sacred space must have stirred something profound, a quiet acknowledgment that the circle of life, in all its fullness, was folding gently inward, then outward again, carrying with it the legacy of both past and future.

As the service came to its close, Curate Everett, with care and devotion, inscribed both names into the parish register, marking the moment in history with a few simple, yet deeply significant, words.

BAPTISMS solemnized in the Parish of Sherfield English in the County of Hants in the Year One Thousand Eight Hundred and Twenty Three No.: 156 When Baptized: 19th October

Child’s Christian Name: Ann

Parents’ Names: William & Mary Hatcher

Abode: Sherfield English

Quality, Trade, or Profession: Labourer

By whom the Ceremony was Performed: G. F. Everett, Curate.

And

No.: 157

When Baptized: 19th October

Child’s Christian Name: George

Parents’ Names: William and Anstice Roud

Abode: Sherfield English

Quality, Trade, or Profession: Labourer

By whom the Ceremony was Performed: G. F. Everett, Curate

Two names, two children, two families forever entwined, not only by blood but by the sacred rites of that Sunday morning. For Louisa, watching her new baby brother and her cousin Ann be baptised together, it was a moment of quiet wonder, a realisation that in their shared baptism, the threads of their family were woven ever tighter, binding them across time and generations. This day, this sacred moment, would forever be a symbol of family, faith, and the enduring love that ran through them all, linking past and future in one unbroken circle.

As the service ended and the last of the candles flickered softly in the dimming light of the church, Louisa stood in quiet reflection, her heart full of gratitude for the new life that had entered their family. George, small and vulnerable, was the first child her family needed in the wake of their loss, the first new life to help heal the fragile wounds left behind. In that moment, Louisa made a quiet vow to herself, a promise that she would protect him, love him, and care for him with all the tenderness she could offer. She would watch over him, as Sarah once might have, and in her heart, she swore to shield him from the sorrow that had touched their family so deeply.

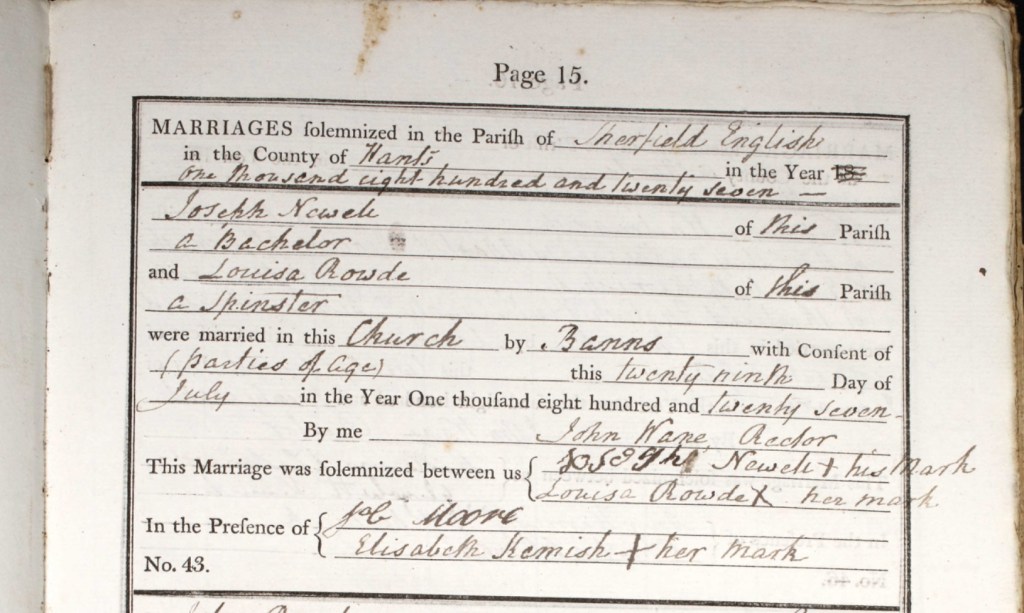

As the family gathered to leave the church, Louisa could not help but glance back at the font, the place where George had been baptised into their faith, into their legacy. He was no longer just a tiny infant, but a living testament to the resilience of their family, a reminder that even in the wake of loss, love could still grow, still bloom, and still bring new hope to the world. In George, Louisa saw not just a brother, but the beginning of healing, and she vowed to protect that promise for as long as she lived.