In the annuals of our family history lies a tale, a story that resonates across time, traversing generations to touch our hearts today.

As I continue to embark on my journey of discovery, I find myself drawn to the life of a remarkable individual, my third great-grandfather William George Willats, aka Biggun.

He was more than just a name etched in faded ink on yellowed pages, he was a living embodiment of resilience, tenacity, and unwavering spirit and the foundation of all his descendants lives.

In a world before ours, where progress was measured by different standards, my third great-grandfather breathed life into a narrative that continues to shape the fabric of our family.

As I delved into the archives, tracing the footsteps of generations long past, the fragments of his existence came into focus. Through faded documents, and stories handed down through the ages, a portrait begins to emerge, a portrait of a man who although had a rocky start in life, made his mark and captured my heart.

Born into an era of uncertainty, my third great-grandfather, faced a world steeped in change, its landscapes transformed by the relentless march of progress. Yet, in the midst of shifting tides, he forged his path with unwavering determination, carving out a life that would resonate with his descendants centuries later.

His story is not one of extravagant fame or great wealth, but rather a testament to the quiet heroism found in everyday lives.

And as I stand at the crossroads of time, the torch of remembrance now rests in my hands.

It is my privilege to illuminate the path he once walked, to honour his legacy and to ensure that his story endures. In weaving together the documents of his life, I hope I’ve captured the essence of a man who defied the constraints of his era and touched the lives of those around him with grace and resilience.

So without further ado, I give you,

The Life Of William George Willats (Biggun) –

The Early Years.

Welcome back to the year 1883, England.

Queen Victoria, sat upon the throne. It was the 16th parliament and George Hamilton-Gordon, 4th Earl of Aberdeen (Coalition) was prime minister.

The Crimean War started between the Russian Empire and an alliance of France, Britain, and the Ottoman Empire. The conflict arose due to disputes over religious rights in the Holy Land and Russia’s expansionist ambitions. The war lasted until 1856 and had a significant impact on European politics and military strategies.

The Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations, often referred to as the Crystal Palace Exhibition, was held in London from May 1 to October 15, 1851. However, it gained popularity and drew massive crowds throughout the year 1853. It showcased various industrial and cultural products from around the world and was a celebration of British industry and innovation.

The Public Health Act aimed to improve public health and sanitation by establishing local boards of health. These boards had the power to implement sanitary measures and regulations in their respective districts, including the construction of sewers, control of public nuisances, and provision of clean water.

Roger Tichborne, a British heir presumed to have been lost at sea, went missing. Years later, in 1866, an individual named Arthur Orton emerged claiming to be Roger Tichborne and started a legal battle for the Tichborne family fortune. The case gained immense public attention and became a famous legal dispute in British history, known as the Tichborne case.

The Royal Albert Hall, one of London’s most iconic concert venues, was officially opened on March 29, 1871. However, construction on the building began in 1867, and the foundation stone was laid in 1868. The hall was named in memory of Prince Albert, Queen Victoria’s husband, who had passed away in 1861.

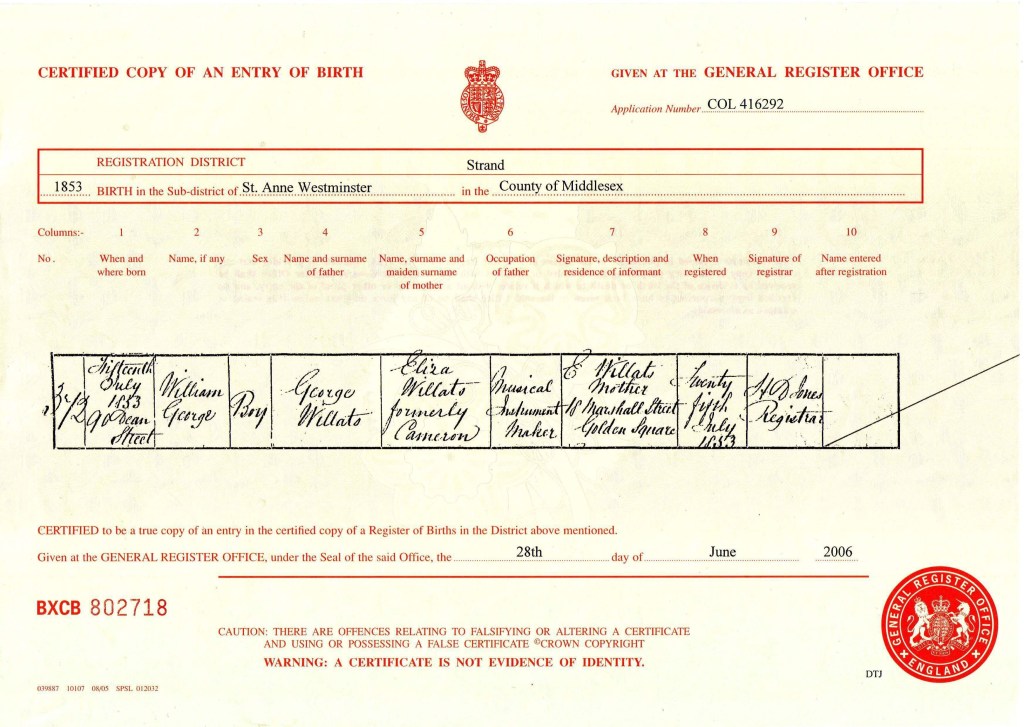

And on the 15th July 1853, at Number 90, Dean Street, St. Anne, Westminster, Middlesex, William George Willats was born.

William George was the Son of George Willats and Eliza Willats nee Cameron.

Williams mum, Eliza registered William’s birth on the 25th July 1853. She gave her husband George’s occupation as a Musical Instrument Maker and their abode as Number 18, Marshall Street, Golden Square, Soho, Westminster.

The name Soho is believed to derive from the cry “So-ho” which was heard around these parts back in the 17th century when it was a popular destination for the fox and hare hunting set. (A century earlier Henry VIII had turned the area into one of his royal parks). Its reputation as a slough of moral lassitude dates from the mid-19th century when it became a magnet for prostitution and purveyors of cheap entertainment. In the early part of the last century large numbers of new immigrants set up in business here and it evolved into a byword for a Bohemian mindset as the exotic and the louche fused together.

Until its surrender to the Crown in 1536 the area shown on fig. 26 had formed part of the estate of the Mercers’ Company, which in January 1559/60 was granted by Queen Elizabeth to William Dodington. In January 1618/19 Robert Baker, the tailor of Piccadilly Hall, acquired some twenty-two acres of this ground, including the close of four acres now to be considered, the title to which was later in dispute between two of his great-nephews, John and James Baker.

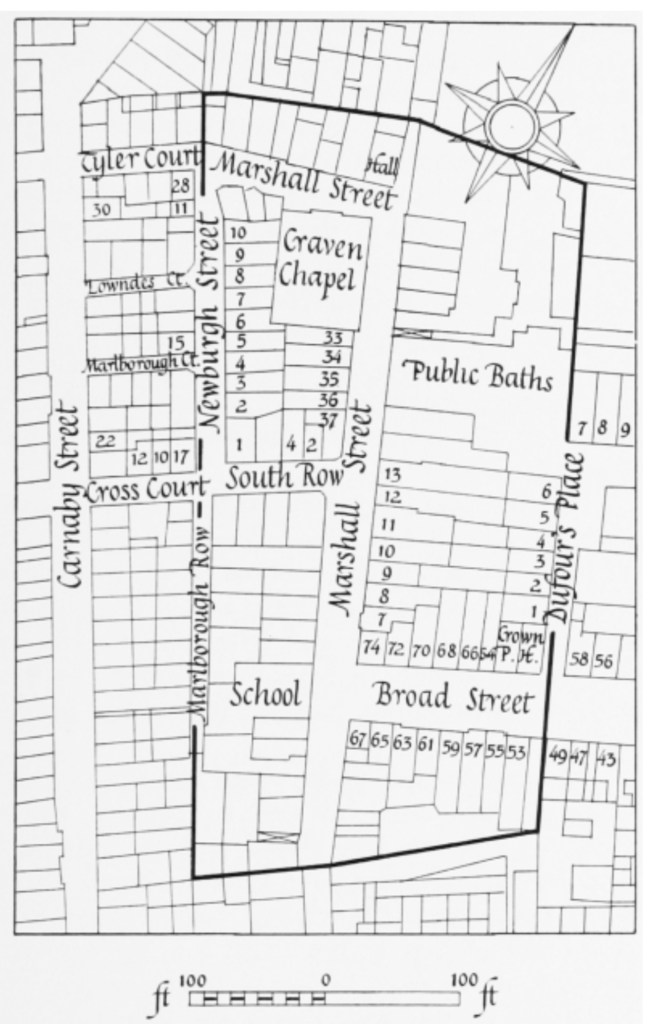

Marshall Street – Marshall Street probably takes its name from Hampstead Marshall, the seat of the Craven family in Berkshire. It was laid out for building in 1733 and the building leases were granted between August 1733 and September 1735. The street seems to have been completely built by 1736.

From 1827 to 1892 there was a National School on part of the site now occupied by the electricity station on the west side of the street.

The southern third of Marshall Street, between Broadwick and Beak Streets, is uninteresting; Nos. 3 and 4 on the east side, probably of the early nineteenth century, are much altered. From Broadwick to Ganton Street the west side is occupied by an electricity station. The east side contains seven houses (described below) which were erected in 1734–5 as part of the same development as Nos. 1–6 (consec.) Dufour’s Place and the western end of Broad (now Broadwick) Street. The west side of the northern third of Marshall Street, above Ganton Street, was rebuilt when Carnaby Market was closed and its buildings demolished in 1820–1; the houses here are described on page 202. Most of the east side of this part of the street is occupied by the Marshall Street Baths.

Each of these seven houses has three storeys and a garret, and originally the fronts were probably finished in stock brick, with a brick bandcourse above the ground storey. Shop-fronts have been inserted in all but Nos. 7 and 9. The fronts of Nos. 9–11 and 13 have been cement-rendered in a plain utilitarian manner, and that of No. 12 more decoratively stuccoed. Nos. 7–10 are the more modest, being two windows wide, Nos. 11, 12 and 13 are three windows wide, and Nos. 12 and 13 have mirrored fronts and a shared chimney-stack. The entrance passage, at one side in each case, led to a dog-legged staircase; later extensions filled in most of the back yards. The upper-storey plan was for one front room and a back room, with a closet beyond the back room.

At No. 11 the first-floor front room, with ovolo-moulded panelling, moulded dado-rail, and dentilled box-cornice, is unusually complete for this neighbourhood although in poor condition. This room has also kept its original four-panelled doors and white marble chimneypiece with panelled jambs and a shaped lintel, similarly panelled. The staircase has closed moulded strings, turned balusters, moulded handrail and column newels. On the back wall of the house, which has been whitewashed, the windows have flush frames.

No. 12 at ground level is now mainly a vehicle entrance to back premises. The stucco facing, the decoration of the first-floor windows and the main cornice suggest a date around 1840. These windows were given thin cornices on brackets, the central one being pedimented. The new main cornice was enriched with modillions and carried a balustrade between pedestals, but the balusters have since been taken out to give more light to the dormer windows.

At No. 13 the entrance passage still has, on the north wall, some sunk panelling with a moulded dado-rail and a small cornice. In the first-floor front room the panelling, although dilapidated, is complete, comprising raised-and-fielded panels with dado-rail, box-cornice and shutters. To the left of the Victorian chimneypiece, in the south wall, is a large cupboard with panelled doors and shaped shelves. The staircase is mainly nineteenth-century, except for the flight to the basement, which has closed moulded strings, turned balusters and a moulded handrail.

Marshall street Baths – Part of this site has been occupied by public baths and wash-houses since 1851–2. These were erected by the vestry of St. James’s, one of the first local authorities to take advantage of the Baths and Wash-houses Act of 1846. The seven commissioners appointed by the vestry to implement this legislation met for the first time in January 1847, but at first had difficulty in obtaining a suitable site. Eventually the vestry made available a parcel of freehold ground which they owned comprising No. 16 Marshall Street and part of the workhouse yard behind. Building work began in February 1851 and the new baths and wash-houses were first opened on 14 June 1852. The architect was Pritchard Baly of Buckingham Street, Adelphi, and the building contractor was H. W. Cooper of Wakefield Street, Regent’s Square.

In 1860 the commissioners took over Nos. 17 and 18 Marshall Street, which adjoined the original building to the north. These were then demolished to allow for the erection of an extension to the baths. This work was carried out between November 1860 and October 1861. The architect for this work was Charles Lee and the builder was William Palmer.

In 1891–2 further extensions were made to the baths when the adjoining Nos. 14 and 15 Marshall Street were rebuilt and incorporated into the building.

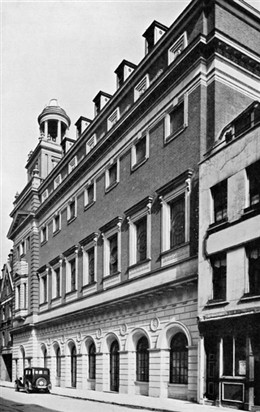

In 1928 the existing baths, together with the adjoining Nos. 7–10 Dufour’s Place, were demolished for the erection of the present building by the Westminster City Council at a cost of £173,000. Messrs. A. W. S. and K. M. B. Cross were the architects and Messrs. Bovis the building contractors (Plate 140d). The new building, which was opened on 17 April 1931, included a firstclass swimming bath 100 feet by 35 feet, a smaller second-class bath, slipper baths, public laundry, maternity and child welfare centre, and a highways depôt at the rear in Dufour’s Place. The two swimming baths have concrete semicircular barrel vaults containing glazed window panels. The larger bath has stepped ranges of seats along either side with dressing boxes at high level behind them. The walls are lined with Sicilian white and Swedish green marble, and the niche at the shallow end has a fountain with dolphin and merman figures by Walter Gilbert. The Marshall Street elevation is neo-Georgian, with a stone-faced arcaded ground floor, brick-faced upper floors with stone dressings, and an attic floor above a large cornice. A pedimented projecting bay at the northern end originally bore a belvedere above an extra storey.

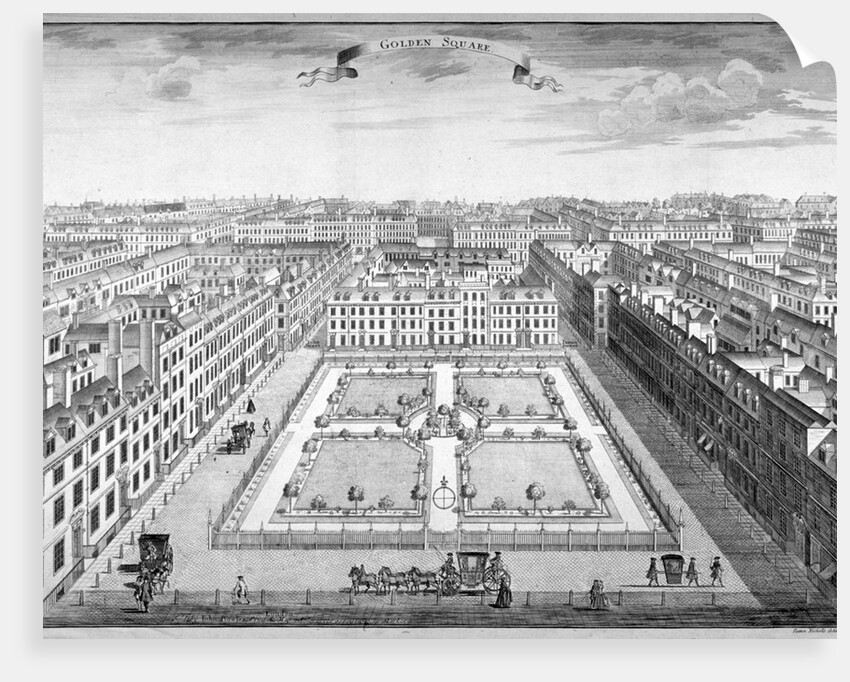

Golden Square, in Soho, the City of Westminster, London, is a mainly hardscaped garden square planted with a few mature trees and raised borders in Central London flanked by classical office buildings. Its four approach ways are north and south but it is centred 125 metres east of Regent Street and double that NNE of Piccadilly Circus. A small block south is retail/leisure street Brewer Street. The square and its buildings have featured in many works of literature and host many media, advertising and public relations companies that characterise its neighbourhood within Soho.

Originally the site of a plague pit, this west London square was brought into being from the 1670s onwards. The square was possibly laid down by Sir Christopher Wren; the plan bears Wren’s signature, but the patent does not state whether it was submitted by the petitioners or whether it originated in Wren’s office. It very rapidly became the political and ambassadorial district of the late 17th and early 18th centuries, housing the Portuguese embassy among others.

Second image, Golden Square, Westminster, London, 1754

Eliza and George Willats, baptised William George Willats, aka Biggun, on Saturday the 17th of December, 1853, at St Pancras, Middlesex, England.

They were residing at Diapers Place and George’s occupation as a Musical Instrument Maker.

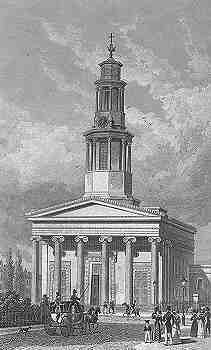

St Pancras Church is a Greek Revival church in St Pancras, London, built in 1819–22 to the designs of William and Henry William Inwood. The church is one of the most important 19th-century churches in England and is a Grade I listed building.

The church is on the northern boundary of Bloomsbury, on the south side of Euston Road, at the corner of Upper Woburn Place, in the borough of Camden. When it was built its west front faced into the south-east corner of Euston Square, which had been laid out on either side of what was then simply known as the “New Road”. It was intended as a new principal church for the parish of St Pancras, which once stretched almost from Oxford Street to Highgate. The original parish church was small ancient building to the north of New Road. This had become neglected following a shift in population to the north, and by the early 19th century services were only held there once a month, worship at other times taking place in a chapel in Kentish Town. With the northwards expansion of London into the area, the population in southern part of the parish grew once more, and a new church was felt necessary. Following the opening of the new Church, the Old Church became a chapel of ease, although it was later given its own separate parish. During the 19th century, many further churches were built to serve the burgeoning population of the original parish of St Pancras, and by 1890 it had been divided into 33 ecclesiastical parishes.

The Church was built primarily to serve the newly built up areas close to Euston Road, especially parts of the well-to-do district of Bloomsbury. The building of St Pancras church was agreed in 1816. After a competition involving thirty or so tenders, designs by the local architect William Inwood, in collaboration with his son Henry William Inwood was accepted. The builder was Isaac Seabrook. The first stone was laid by the Duke of York at a ceremony on 1 July 1819. It was carved with a Greek inscription, of which the English translation was “May the light of the blessed Gospel thus ever illuminate the dark temples of the Heathen”.

The church was consecrated by the Bishop of London on 7 May 1822, and the sermon was preached by the vicar of St Pancras, James Moore. The total cost of the building, including land and furnishings, was £76,679, making it the most expensive church to be built in London since the rebuilding of St Paul’s Cathedral. It was designed to seat 2,500 people.

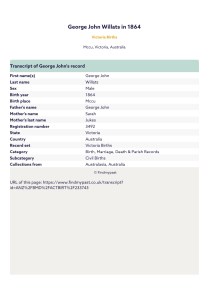

Between Biggun’s birth and the year, 1855, Biggun’s parents George and Eliza’s marriage broke down.

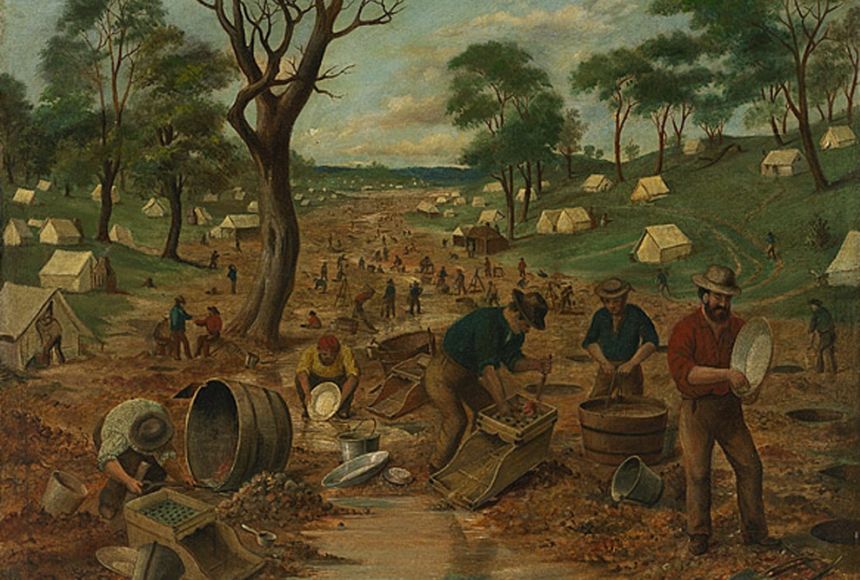

His father George John Willats, left the United Kingdom, in the search for gold, in Australia, and he started a new life there.

In the meantime, back in the United Kingdom, his mum Eliza started a relationship with her Brother Inlaw, Biggun’s uncle, Richard Henry Willats. Richard kindly took over the role of Biggun’s father and it wasn’t long before Biggun’s mum Eliza and his Uncle/stepfather Richard, were expecting and Biggun had a half-sibling.

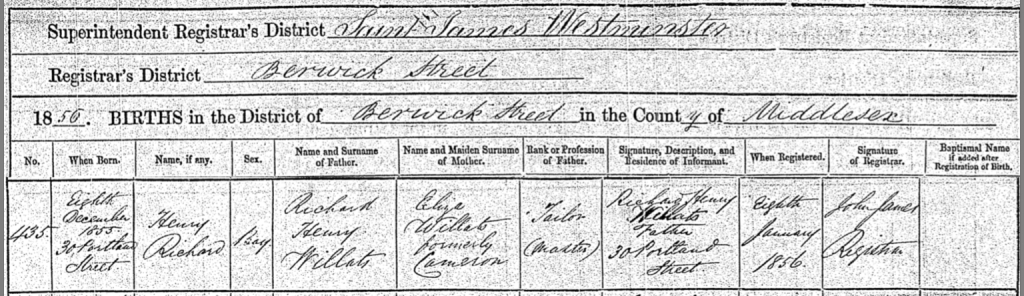

Biggun’s half-brother, Henry Richard Willats, was born on Saturday the 8th of December, 1855, at Number 30 Poland Street, Berwick Street, St James, Westminster, Middlesex, England. Henry’s Father Richard Henry Willats, registered his birth on, Tuesday the 8th of January, 1856. Richard gave his occupation as a Tailor and their abode as Number 30 Portland Street.

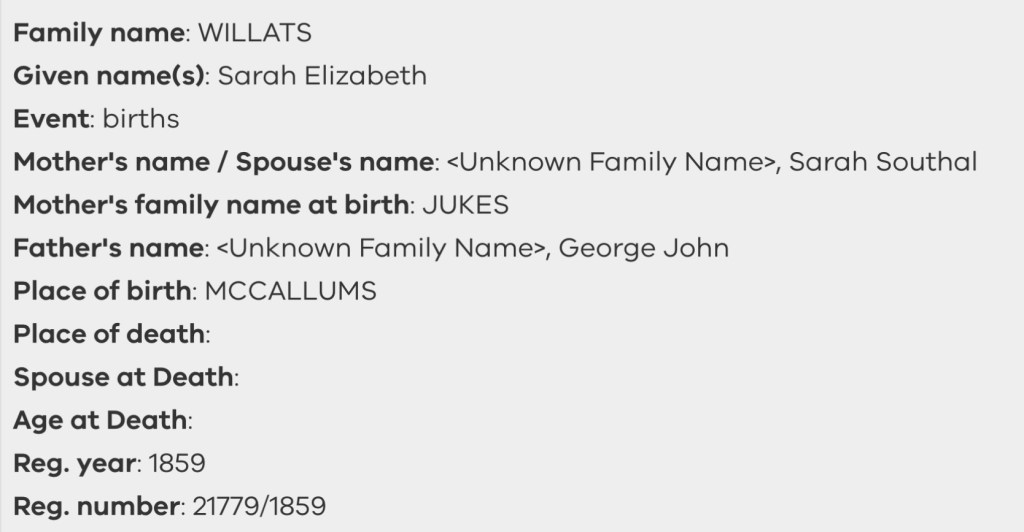

Across the other side of the world, Biggun’s father, George John Willats married Sarah Elizabeth Southall Jukes, in Victoria, Australia, in 1856.

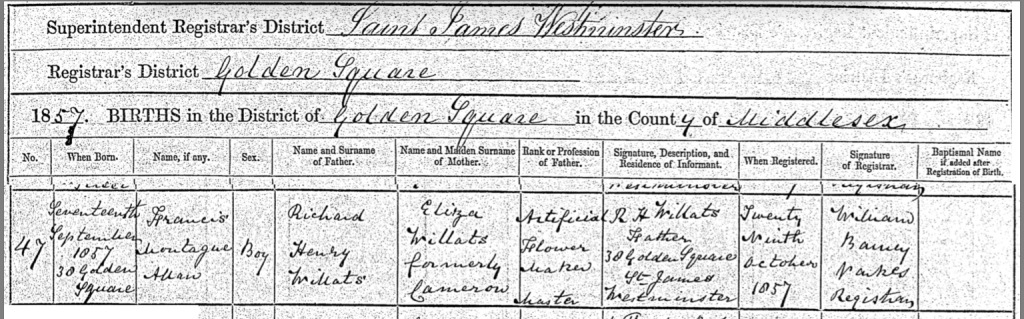

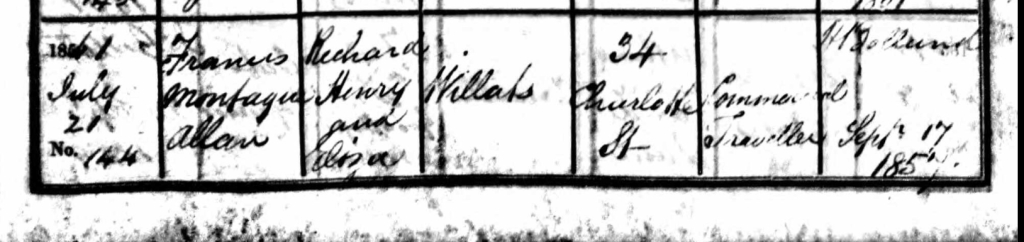

Bigguns brother, Francis Montague Allen Willats, was born on Thursday the 17th of September, 1857, at Number 30 Golden Square, St. James, Westminster, Middlesex, England. Richard Henry, registered Francis birth, on the 29th of October 1857. He gave his occupation as a Master Artificial Flower Maker and his abode as 30 Golden Square, St. James, Westminster.

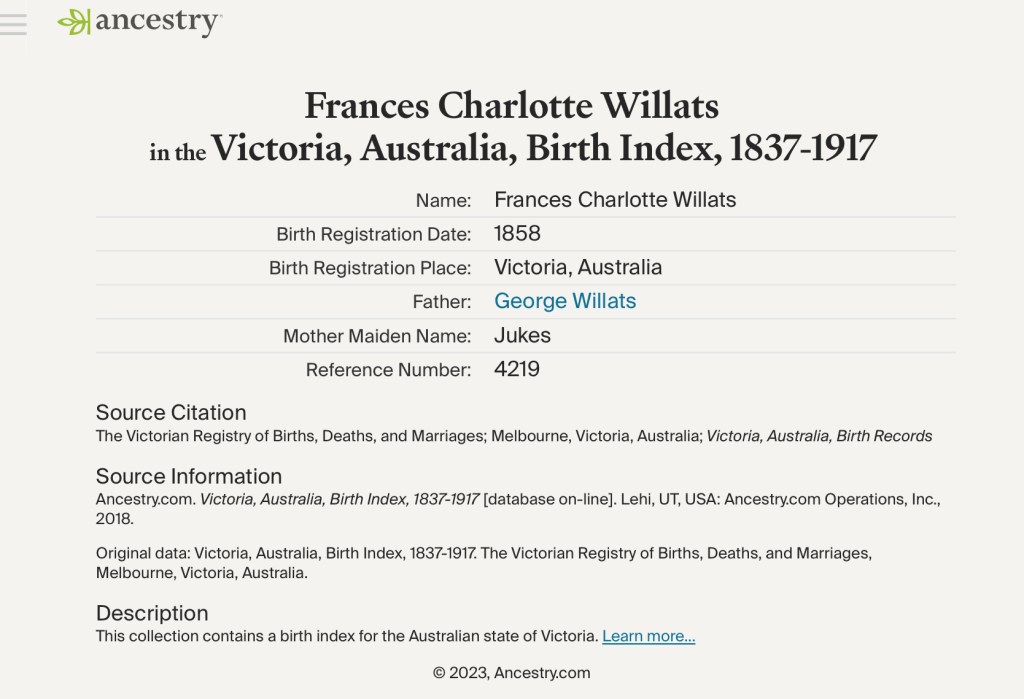

And across the pond, Biggun’s Biological father George John and his new wife Sarah Elizabeth Southall Willats nee Duke were starting their own family and Biggun’s half-sister, Frances Charlotte Willats, was born in 1858, in Victoria, Australia. I believe she was born in McCullum’s, Victoria, Australia, possibly McCallum’s Creek.

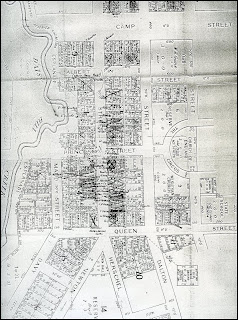

McCallum Creek in west Victoria starts below Gordon Hill at an elevation of 374m and ends at an elevation of 191m merging with the Tullaroop Creek.

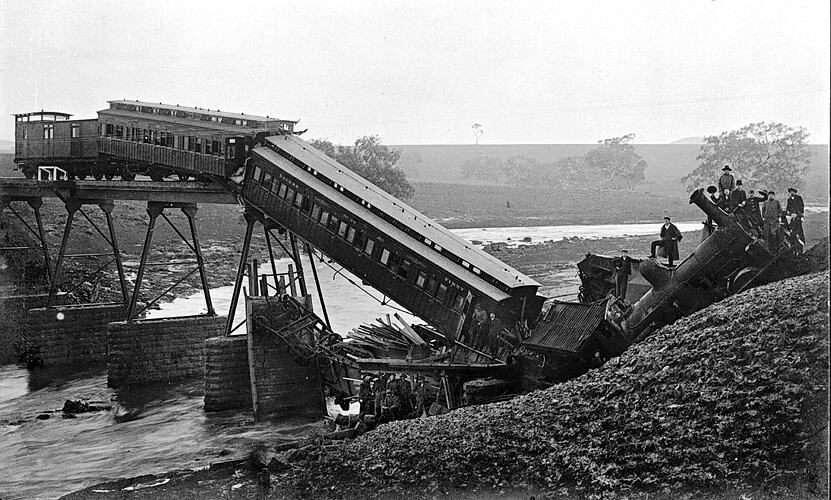

When researching McCallum, all I seem to be able to find is information and photos of, a train accident resulting from the failure of the bridge at McCallum’s Creek. The bridge had been weakened by floodwaters. Several people posed beside the train, part of which is balanced between the collapsed bridge and the river bank.

Biggun’s half- sister, Sarah Elizabeth Willats was born in 1859 in Amherst, Mccullum’s, Victoria, Australia, to Sarah Elizabeth Southall Jukes, when she was roughly 21 years old and George John Willats, when he was roughly 27 years.

(I will order both Frances and Sarah’s birth certificates, as soon as I can, but they are rather expensive compared to English certificates, which aren’t cheap either.)

Amherst is a former municipality and gold rush town situated within the Shire of Central Goldfields in Victoria, Australia. Much of the original township has been destroyed by fire, and little remains other than Amherst Cemetery at 235 Avoca Road, Talbot.

Amherst is located 5 kilometres (3.1 mi) west of Talbot and 173 kilometres (107 mi) north west of Melbourne. In its heyday, Amherst was situated in the middle of a gold belt 11 kilometres (6.8 mi) long and 1.5 kilometres (0.93 mi) wide.

Nowadays, the size of Amherst is approximately 33.7 square kilometres (13.0 sq mi). Four parks cover nearly 7% of this total area. The town mostly resembles an uneven paddock with little to show for its colourful and significant history.

Nevertheless, Amherst is surrounded by old gold workings, and there is State forest to the north. The Amherst vineyard was planted in 1989 on land 20 kilometres (12 mi) south east of Avoca. The Amherst Winery markets its ‘Daisy Creek’ red and white wine. Evidence of the gold diggings can be seen around the vineyard in the quartz-rich soil.

The town of Amherst originally began as a mining settlement referred to as Daisy Hill or occasionally Daisy Hill Creek, which extended through the village. The actual location of Daisy Hill is still not known as it is often confused with a land division nearby in the Paddy Ranges known as the Daisy Hill Block, which was an earlier squatter survey lease in the Pyrenees. Additionally, the Colonial Police Troopers were stationed in 1849 on the highway to Maryborough at a place widely referred to as Daisy Hill. Furthermore, newspapers of that era often loosely referred to Clunes Station, 10 miles (16 km) east as the “Pyrenees”.

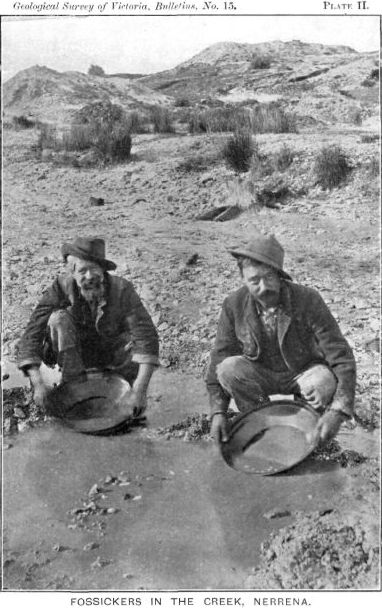

The two main colonial towns of Geelong and Melbourne had experienced gold fever hype since the California Gold Rush began in 1848. Daisy Hill (Amherst) gained notoriety due to an illegitimate gold rush in 1849 when exiled shepherd and former Parkhurst prison inmate Thomas Chapman sold 38 ounces of gold to Collins Street, Melbourne jeweller Charles Bretani. This sparked a rush to the area. Chapman vanished soon after the sale, and uncertainty surrounds where the nugget was actually found, or whether it was stolen. The settlement of Daisy Hill (later named Amherst) is not to be confused with the contemporary town of Daisy Hill, Victoria. Amherst is now virtually deserted.

In May 1852, a separate verifiable discovery of gold was made at Daisy Hill. During the Victorian gold rush era, the location quickly became known as an extremely lucrative diggings, and tens of thousands of miners rushed to the area. Between 1852 and 1855, gold was found at a number of locations.

Back in the United Kingdom, Bigguns half-sister, Charlotte Ellen Willats, was born on Wednesday the 10th of August, 1859, at Number 56, Bunton Street, St Pancras, Middlesex, England. Eliza registered Charlotte’s birth on Tuesday the 13th of December, 1859. She gave Richards occupation as a Commercial Traveller and their abode as, Number 56, Bunton Street, Saint Pancras.

Richard and Eliza, baptised Biggun’s sister, Charlotte Ellen Willats, on Thursday the 1st of September, 1859, at the Saint Pancras Church, Saint Pancras, London, England.

Richard’s occupation was given as an Engraver and their abode as, Mabledon Row.

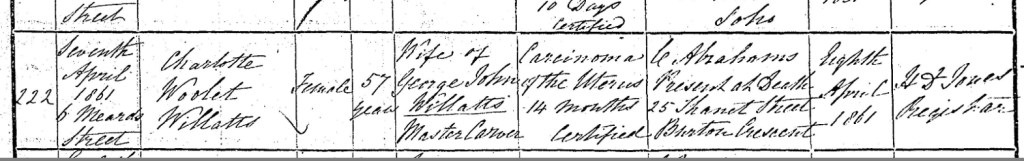

Sorrowfully, Biggun’s paternal, Grandmother, Charlotte Woollet Willats nee Carter, wife of George John Willats, a master craver and mother of 8, passed away on, Sunday the 7th of April, 1861, at number 6, Meard Street, Soho, Westminster, London, England when she was 58 years old.

Charlotte died from Cancernora of the Uterus, 14 months.

Charlotte’s daughter, Charlotte Abraham nee Willats, was present and registered Charlotte’s death on Monday the 8th of April, 1861.

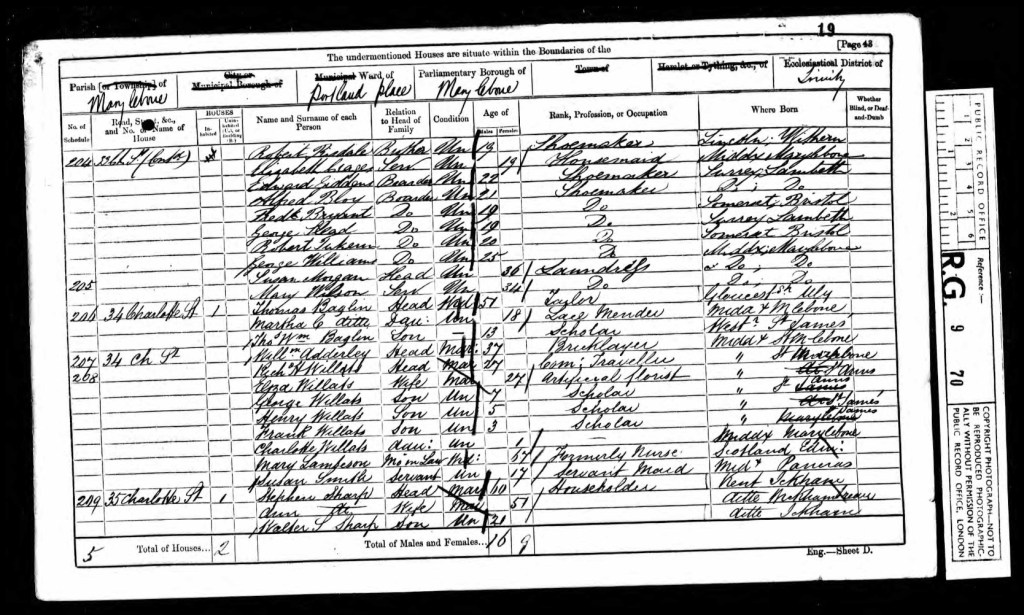

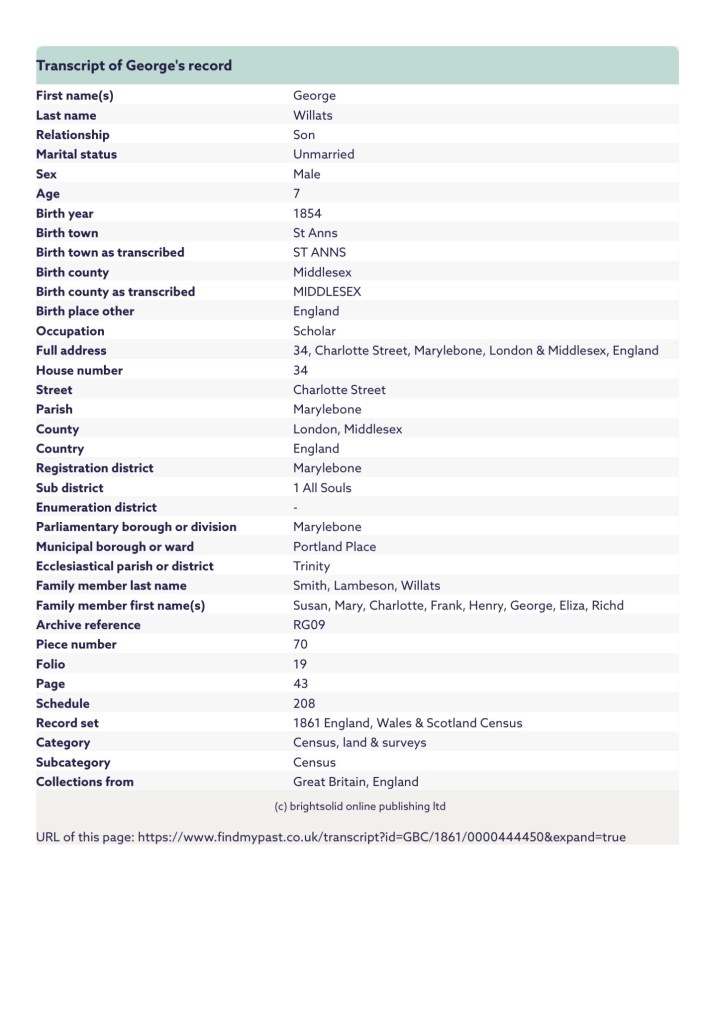

The 1861 census was held on the same day as Biggun’s Grandmothers death, the 7th April, 1861. It shows Biggun, residing at 34, Charlotte Street, Marylebone, Middlesex, England, with his parents, Richard and Eliza and siblings, Henry, Frank, and Charlotte, his grandmother Mary Falconer and a servant, Susan Smith.

Richard was working as a commercial traveller, and Eliza was an Artificial florist.

Charlotte Street, seems to have been named after Queen Charlotte and runs from south to north from Percy Street to Howland Street. The original Charlotte Street extended to Goodge Street, and from thence to Tottenham Street it was called Lower Charlotte Street, the remainder being known as Upper Charlotte Street. In 1766 building was proceeding on its western side as shown by a lease from the Goodge Brothers to William Franks, gentleman, of Gerrard Street (afterwards of Percy Street, q.v.), of ground adjoining west on ground late Marchant’s Waterworks, south on ground whereon is late erected a chapel also let to him and north on Bennett Street. The Waterworks are shown on Rocque’s Plan of London (1746), and Percy Chapel stood on the west side of Charlotte Street immediately opposite the end of Windmill Street (see below, p. 21). Charlotte Street is typical of the late 18th-century development of this area and its present condition is therefore described in this section in some detail. The houses have been re-numbered twice since they were first numbered, the present sequence running from south to north, with the odd numbers on the west and the even on the east side. The progress of erection was in the same direction and except for the breaks at the cross streets, the houses were (before the war) in uninterrupted rows like those in Percy Street.

The ground floor shop fronts are modern unless otherwise described. No. 16, the Fitzroy Tavern, is all modern. Original brickwork is seen in Nos. 18, 20, 28, 32 and 36, but with a few variations, while Nos. 22, 24, 26, 30 and 34 have been cemented. The first floor windows of No. 20 have lowered sills and iron balconies. The fourth storeys of Nos. 18 and 20 are later additions, the latter higher than the former. The cement face of No. 22 is of a mid-late 19th-century design. Nos. 24 and 26 have architraves to the windows, and the first-floor window sills are at floor level with balconies: the top storey has a cornice and parapet behind which are mansard roofs with dormer windows. The ground storey of No. 24 has the two original window openings, fitted with casements and a roundheaded south doorway. The top storey of No. 28 is modern, the wall having been rebuilt from about 2 feet above the second floor windows; the first floor sills are at floor level. The windows of No. 30 are the original openings, with the first-floor sills lowered all have architraves. The two storeys above the shop of No. 32 are original but the top two storeys are later: they have been damaged and the windows are at present unglazed. The ground floor front may be of early 19th-century design with a middle and a south doorway but the actual windows are later. The south door is eight-panelled. The cementing of No. 34 resembles that of Nos. 24 and 26 but the sills have not been lowered. The shop front—a middle window between side doorways—is probably older than that of No. 32. The two top storeys of No. 36 are built of later and larger bricks than the lower. The north side, to Colville Place, is cemented in the ground storey and of ancient brickwork above and is unpierced.

The hollow cornice of No. 9 is repeated in a number of lower rooms and passages of this row but not in all. The staircases also differ. For instance Nos. 20 and 22 have the original stairs with plain newels, turned balusters with a square block and cut strings with shaped brackets but to No. 18 is plainer with a straight string and in No. 26 the cut strings have no brackets and the handrail finishes with a spiral over the lowest newel.

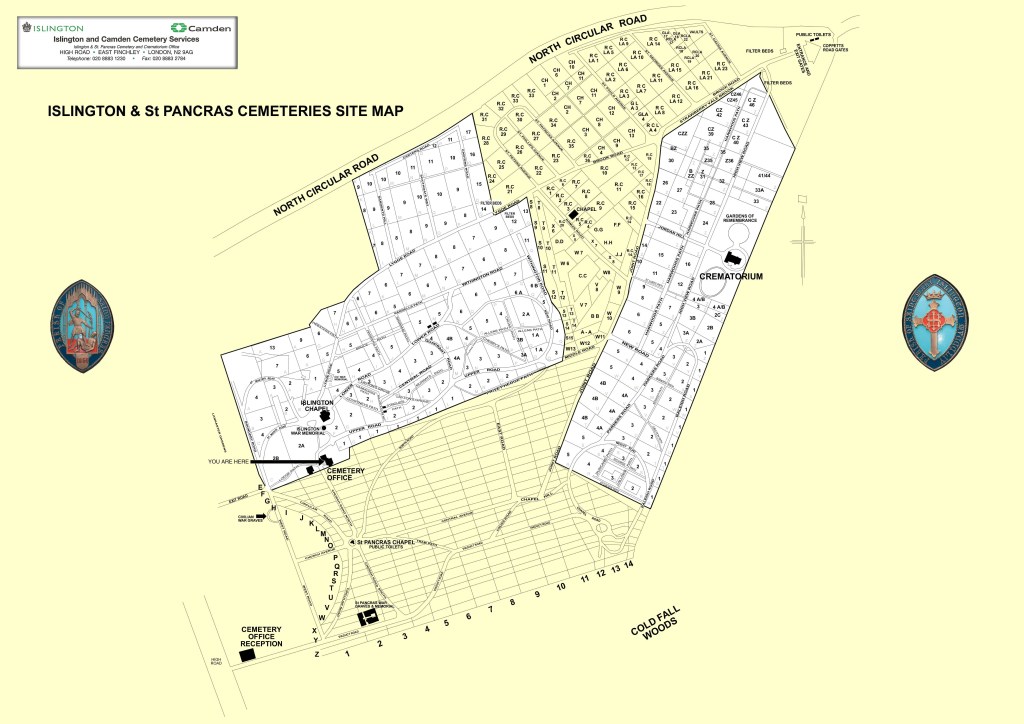

The Willats family, laid Charlotte, to rest at, St Pancras Cemetery, Camden, London, England, on Friday the 12th of April 1861, in grave Z10/72, with 17 Others.

They were, Henry Edward Deacon, Mary Randall, Mary Ann Rachel Toure, John Smallwood and Emily Fossett, who were buried on the 12th of February 1880. John Mayhew, who was buried on the 11th of February 1880. Ann Smith, who was buried on the 10th of February 1880. John Union Parsler, George Baker, who were buried on the 9th of February 1880. Sarah Ewens, and Emma Arnold, were buried on the 15th of April 1861. Isaac Skelton, and Rachel Jones, buried on the 14th of April 1861, Mary Holloway, buried on the 13th of April 1861. Emily Greene, Edward Bush, and Henry Tudor were buried on the 11th of April 1861.

St Pancras Cemetery is also known as East Finchley Cemetery and Islington and St Pancras Cemetery, with Islington Crematorium.

Islington and St Pancras Cemetery is a 190-acre cemetery in East Finchley, three miles to the northwest of Alexandra Palace.

The cemetery actually comprises two separate burial grounds – Islington and St Pancras – which together have around 1 million interments, making it the largest cemetery in the UK in terms of the number of burials. The site is classed as a Grade II English Heritage-listed building.

The cemetery was established in 1854, after the St Pancras Burial Board purchased 88 acres on Finchley Common – land which was previously known as Horseshoe Farm. This became London’s first municipally-owned cemetery. A further 94 acres were purchased in 1877, after which the cemetery was split into sections for Islington (north-west and eastern boundary) and Camden (centre, north and south west). Although the boundary no longer exists its remains can still be seen.

Since the site opened there have been around 812,000 burials, 56,000 cremations and a number of reinternments from other demolished graveyards.

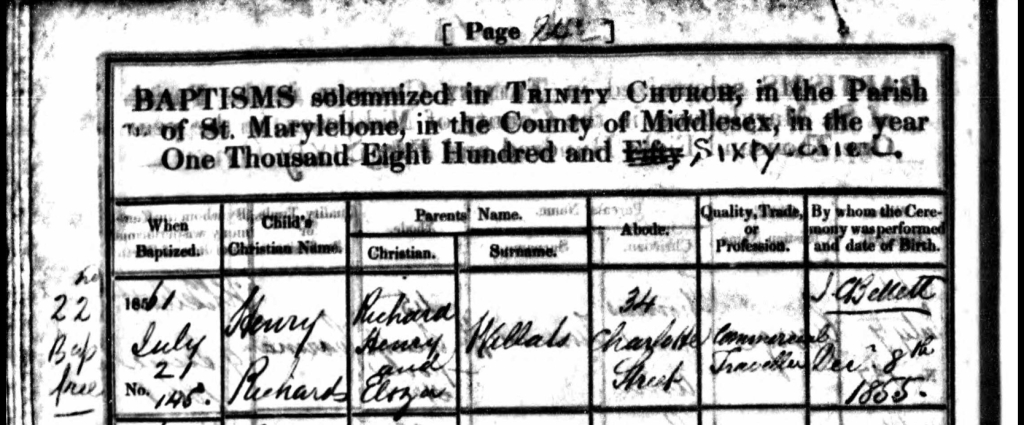

The family had reason to celebrate when Biggun’s brothers, Henry Richard Willats and Francis Montague Allen Willats, were baptised on Sunday the 21st of July, 1861, at the Holy Trinity Church, Marylebone Road, Westminster, London, England.

Their father, Richard, gave his occupation as a commercial traveller and their abode, as 34 Charlotte Street.

Holy Trinity Church, in Marylebone, Westminster, London, is a Grade I listed former Anglican church, built in 1828 and designed by John Soane. In 1818 Parliament passed an act setting aside one million pounds to celebrate the defeat of Napoleon. This is one of the so-called “Waterloo churches” that were built with the money. It has an external pulpit facing onto Marylebone Road, erected in memory of the Revd. William Cadman MA (1815-1891), who was rector of the parish from 1859 – 1891, renowned for his sonorous voice and preaching. The building has an entrance off-set with four large Ionic columns. There is a lantern steeple, similar to St Pancras New Church, which is also on Euston Road to the east.

George Saxby Penfold was appointed as the first Rector, having previously taken on much the same task as the first Rector of Christ Church, Marylebone. The first burial took place in the vault of the church in 1829, and the last was that of Sir Jonathan Wathen Waller in 1853.

By the 1930s, the use of the church had declined, and from 1936 it was used as a book warehouse by the newly founded Penguin Books. A children’s slide was used to deliver books from the street into the large crypt. In 1937 Penguin moved out to Harmondsworth, and the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge (SPCK), an Anglican missionary organisation, moved in. It was their headquarters until 2006, when they relocated to Tufton Street, Westminster (they have since moved again to Pimlico). The church is currently[when?] the location of the world’s first wedding department store, The Wedding Gallery, which is based on the ground floor and basement level. The first floor is used as an events space operated by one event and known as “One Marylebone”.

The former church stands on a traffic island by itself, bounded by Marylebone Road at the front, and Albany Street and Osnaburgh Street on either side; the street at the rear north side is Osnaburgh Terrace.

Biggun sister, Edith Cameron Willats, was born on Sunday the 20th of October, 1861, at 34 Charlotte Street, Marylebone, Middlesex, England.

Richard Henry, registered Edith’s birth on Monday the 25th of November, 1861, in Marylebone.

He gave his occupation as a Commercial Traveller and their abode as, Number 34 Charlotte Street, Marylebone.

Across the pond, Biggun’s biological father, George John and Step-Mum, Sarah, welcomed their third daughter into their home, hearts and family, in 1862, in McCallums, Victoria, Australia. They named her Ann Rebecca Willats.

And back in London, Biggun’s brother, Arthur Charles Willats, was born on Saturday the 11th of July, 1863, at Number 37, Charlotte Street, Marylebone, Middlesex, England. Richard Henry registered Arthur’s birth on the 21st of August 1863. Richard’s occupation was given as a, Commercial Traveller and their abode as Number 37, Charlotte Street, Marylebone.

Biggun’s brother, Arthur Charles and his sister, Edith Cameron Willats, were baptised on Sunday the 9th of August 1863, at Holy Trinity Church, Marylebone Road, Westminster, Middlesex, England.

Richard’s occupation was given as a Traveller and their abode was Number 37, Charlotte Street.

Biggun’s family just kept growing.

Down under in sunny Australia , Biggun’s half-brother, George John Willats, who was named after their father, George John Willats, was born at some point in the year 1864, in Mc Callum, Victoria, Australia. He was most likely born in, Amherst, Mccullum’s, Victoria, Australia.

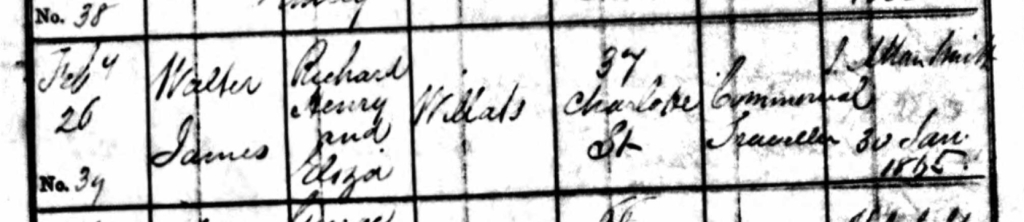

Back in the London, Biggun, welcomed another new brother, on Friday the 13th of January, 1865. Eliza and Richard, named him, Walter James Willats.

Eliza gave birth at their home, 37, Charlotte Street, Marylebone, All Souls, Middlesex, England.

Richard registered Walters birth on the 9th of March 1865. He gave his occupation as a commercial traveller and their abode as, 37, Charlotte Street.

Biggun’s brother, Walter James, was baptised on Sunday the 26th February, 1865, at Holy Trinity Church Marylebone Road, Marylebone, Middlesex, England.

Richards’s occupation was given as a commercial traveller and their abode was 37 Charlotte Street.

Biggun’s Mum, Eliza Willats nee Cameron, and his uncle/Stepfather Richard Henry Willats finally wed on Thursday the 4th of May, 1865.

They married at, St Margarets, Westminster, London, England.

Richard was a Bachelor.

Eliza was listed as a widower, which is rather strange as her first husband George John Willats (Richard Henry Willats’s brother) didn’t die until later that year.

Their witnesses were, George John Willats, (Biggun’s father and Eliza’s first husband) and Eliza’s sister, Mary Cameron.

Eliza and Richard, were residing at 10 North Street.

Richard was working as a, Commercial Traveller.

Eliza’s Father, Allen Cameron was working as a Tailor and Richard’s Father, George John Willats, was working as a Wood Craver.

Their banns were read, at St John the Evangelist, Smith Square, London, England, on the Sunday 9th and Sunday 16th of April, by W.S. Bruce and again on Sunday the 23rd of April, 1865, by J. Graham.

St John’s Smith Square is a redundant church in the centre of Smith Square, Westminster, London.

In 1710, the long period of Whig domination of British politics ended as the Tories swept to power under the rallying cry of “The Church in Danger”. Under the Tories’ plan to strengthen the position of the Anglican Church and in the face of widespread damage to church buildings after a storm in November 1710, Parliament concluded that 50 new churches would be necessary in the cities of London and Westminster. An Act of Parliament in 1711 levied a tax on coal imports into the Port of London to fund the scheme and appointed a commission to oversee the project. Archer was appointed to this commission alongside, amongst others, Hawksmoor, Vanburgh and Wren. The site for St. John’s was acquired from Henry Smith (who was also Treasurer to the Commissioners) in June 1713 for £700 and building commenced immediately. However, work proceeded slowly and the church was finally completed and consecrated in 1728. In total, the building had cost £40,875. The church was built by Edward Strong the Younger a friend of Christopher Wren the Younger.

In the 18th century

And St. Margaret’s, known as ‘the Church on Parliament Square’, is a 12th-century church next to Westminster Abbey. It’s also sometimes called ‘the parish church of the House of Commons’.

The Church of St Margaret, Westminster Abbey, is in the grounds of Westminster Abbey on Parliament Square, London, England. It is dedicated to Margaret of Antioch, and forms part of a single World Heritage Site with the Palace of Westminster and Westminster Abbey.

The church was founded in the twelfth century by Benedictine monks, so that local people who lived in the area around the Abbey could worship separately at their own simpler parish church, and historically it was within the hundred of Ossulstonein the county of Middlesex. In 1914, in a preface to Memorials of St. Margaret’s Church, Westminster, a former Rector of St Margaret’s, Hensley Henson, reported a mediaeval tradition that the church was as old as Westminster Abbey, owing its origins to the same royal saint, and that “The two churches, conventual and parochial, have stood side by side for more than eight centuries – not, of course, the existing fabrics, but older churches of which the existing fabrics are successors on the same site.

In 1863, during preliminary explorations preparing for this restoration, Scott found several doors overlaid with what was believed to be human skin. After doctors had examined this skin, Victorian historians theorized that the skin might have been that of William the Sacrist, who organized a gang that, in 1303, robbed the King of the equivalent of, in modern currency, $100 million. It was a complex scheme, involving several gang members disguised as monks planting bushes on the palace. After the stealthy burglary 6 months later, the loot was concealed in these bushes. The historians believed that William the Sacrist was flayed alive as punishment and his skin was used to make these royal doors, perhaps situated initially at nearby Westminster Palace. Subsequent study revealed the skins were bovine in origin, not human.

You can read more about, St Margaret’s here.

in the grounds of Westminster Abbey on Parliament Square, London, England

As I have mentioned before, I have no idea as to how Richard and Eliza were able to marry, as it was strictly forbidden to marry a brother’s wife even a deceased brother.

Family stories state that a sympathetic member of the clergy came to their rescue and had the first marriage annulled.

I guess we will never know for sure but it seems that maybe something fishy was going on as George John married Sarah Elizabeth Southall Jukes, in Victoria, Australia, in 1856 (11years before Richard and Eliza wed. George and Sarah, went on to have 4 Children. George John, stayed in Australia until his death, visiting England frequently.

Mournfully, Biggun’s biological father, George John Willats, died in 1865 in Victoria, Australia.

I truly wonder how his death effected Biggun.

Did he know George John Willats, as his father or his uncle?

We know he visited his father when Biggun was in his 20’s but I sadly know nothing about their relationship, which saddens my soul.

I soulfully hope they had a love-filled relationship and that there wasn’t any bitterness between them, due to George leaving Biggun to be brought up, loved and adored by his mum and uncle/step-father Richard.

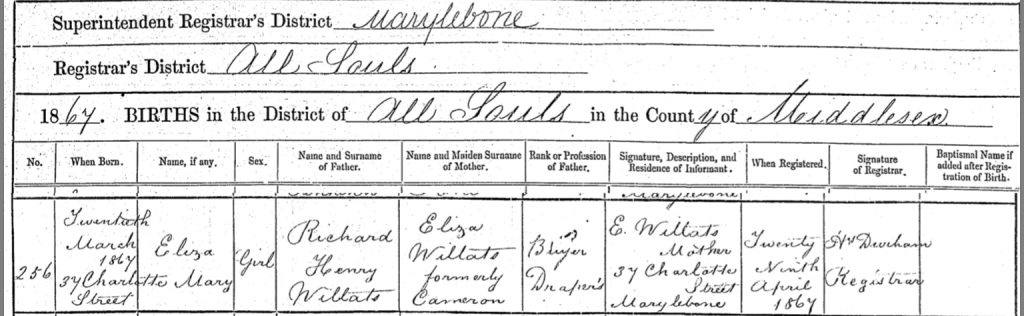

A few years later, Biggun’s mum Eliza, was once again in the family way and gave birth to a baby girl whom they called, Eliza Mary Willats.

Eliza Mary was born on Wednesday the 20th of March, 1867, at Number 37 Charlotte Street, All Paul’s, Marylebone, Middlesex, England.

Her Father Richard was working as a Buyer of Diamonds, at the time of her birth.

Eliza registered Eliza’s birth on Monday the 29th April 1867.

Eliza Mary was known as Polly.

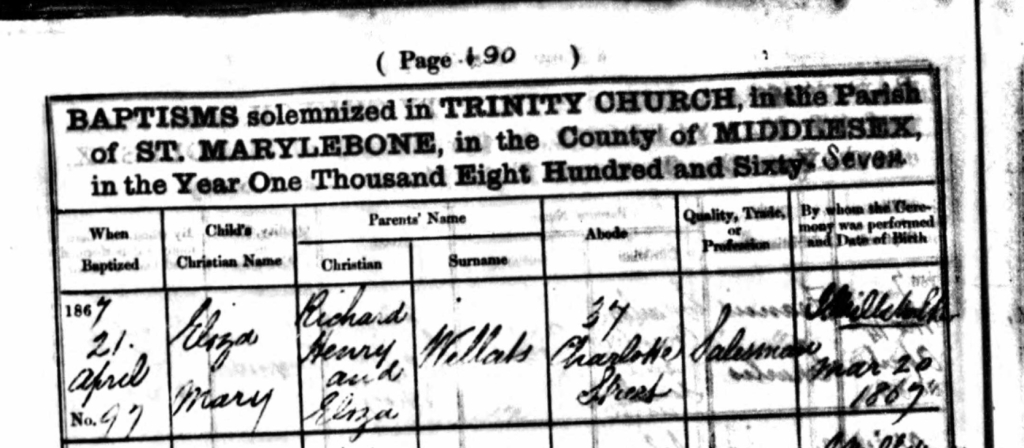

Biggun, Richard, Eliza, and family, baptised Eliza Mary, on Sunday the 21st of April 1867, at Holy Trinity Church, Marylebone Road, Marylebone, Middlesex, England. Richards’s occupation was given as Saleman and their abode as, 37 Charlotte Street.

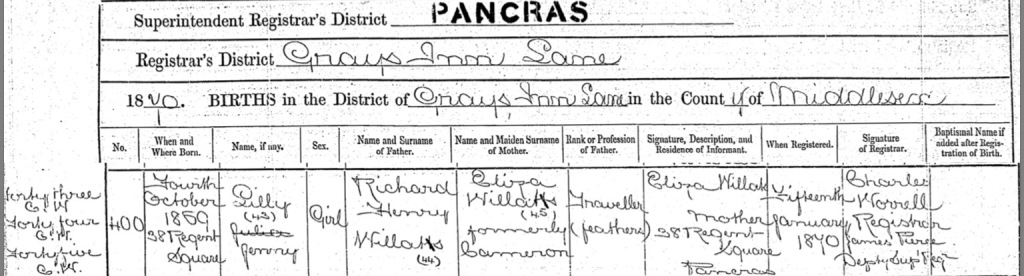

Biggun’s mum, Eliza, was once again in the family way and she gave birth to her 9th child, Richard and her, 4th Daughter, on Monday the 4th of October, 1869, at, Number 38, Regent Square, Gray’s Inn Lane, Pancras, Middlesex, England.

Eliza and Richard named her, Lilly Jenny Willats.

Richards, occupation was listed as a Traveller ( Feathers). Eliza registered her birth on Friday the 15th of January 1869.

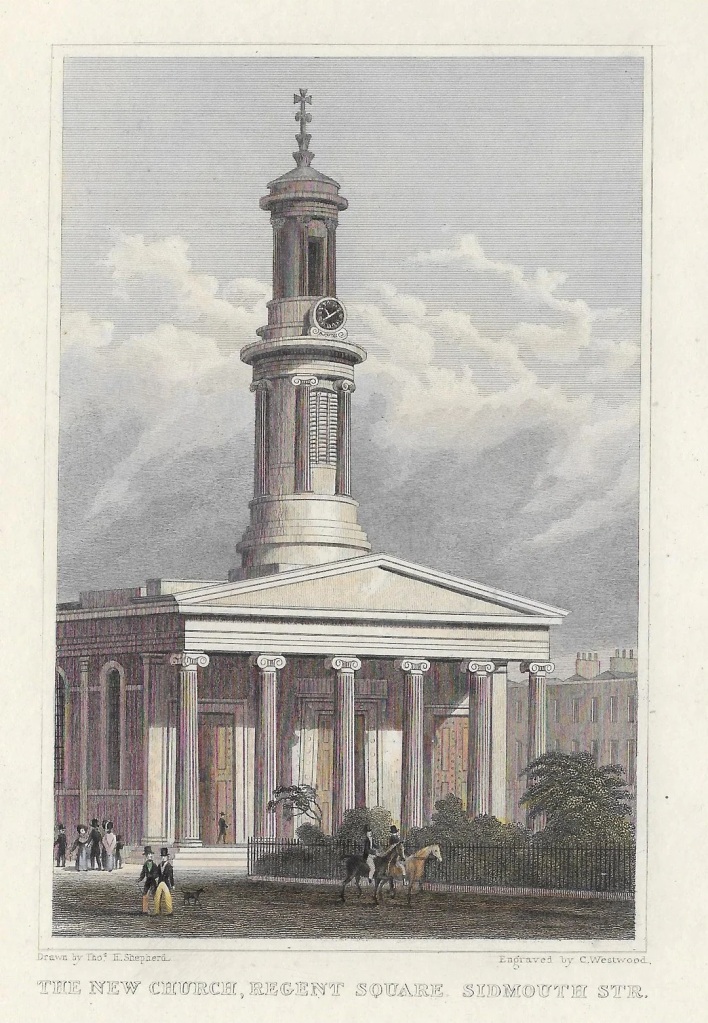

Regent Square is a public square and street in the London Borough of Camden in London, England. It is located near Kings Cross and Bloomsbury. Regent Square was laid out around a large garden in the historic Harrison Estate and first occupied in 1829, forming a garden square similar to more famous ones to the west in Bloomsbury. The southern side of the square is composed of its original buildings and is Grade II listed in its entirety. Also listed is the phone box within the square gardens themselves.

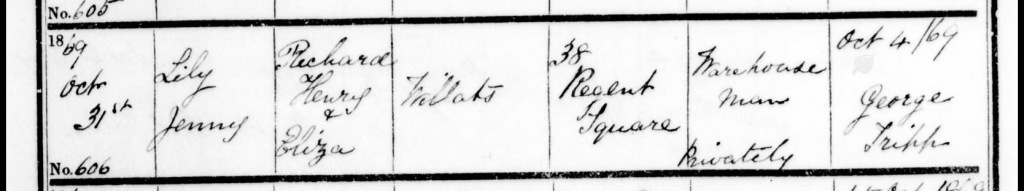

Lillian Jenny Willats, was baptised on Sunday the 31st October, 1869, at Saint Peter Church, Saint Pancras, London, England. It was a private baptism. Her baptism shows that Richard was working as a Warehouse Man and their abode was, Number 38, Regent Square.

Devastatingly Saint Peters in Regent Square was hit by bombs in the war and had to be demolished. Unfortunately there doesn’t seem to be much information about it online. From the below image, it was a very impressive building.

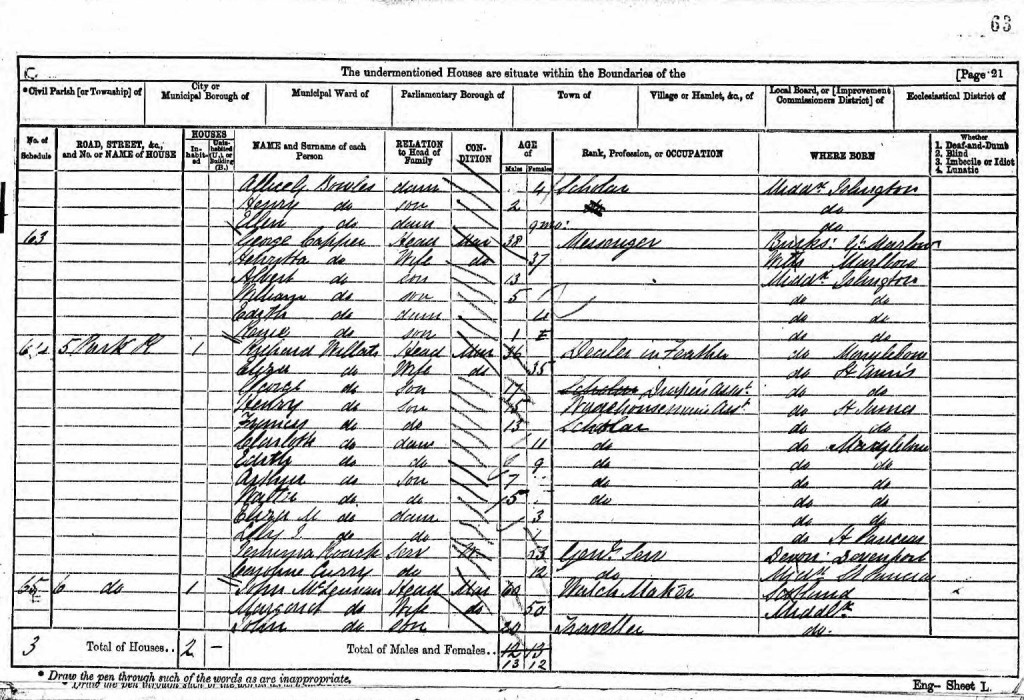

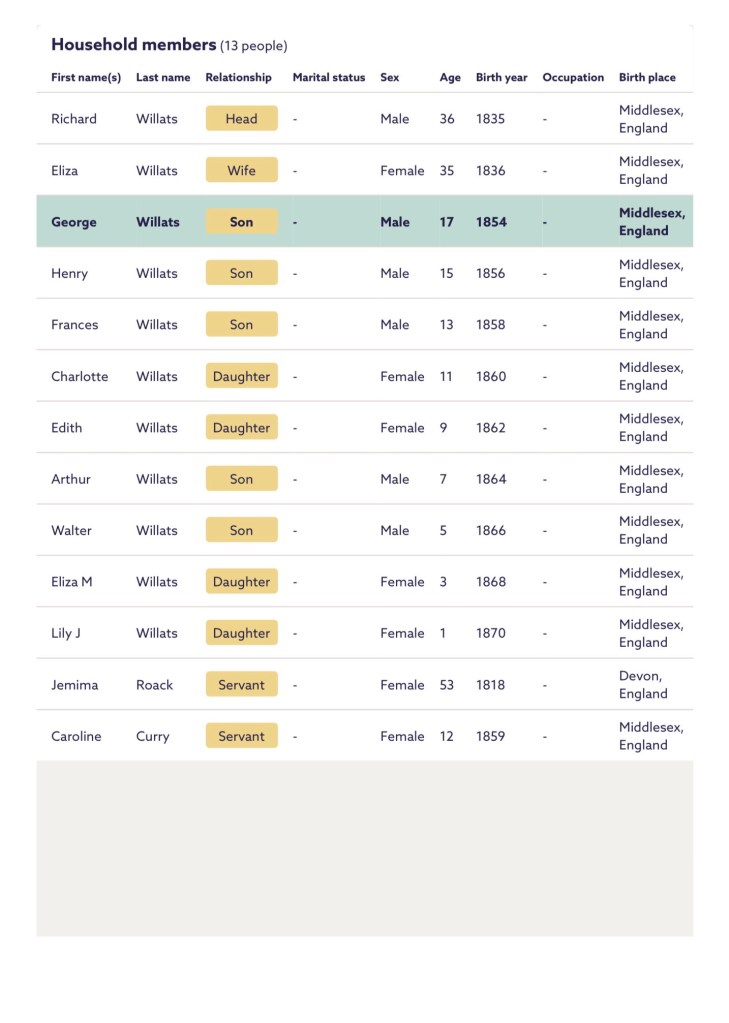

Biggun, his parents Richard, and Eliza, and his siblings, Walter, Henry, Eliza, Francis, Lillian, Edith, and Charlotte, were residing at, Number 5, Park Road, Islington, Middlesex, England, on Sunday the of 2nd April 1871, when the census was taken.

It shows that Biggun was working as a Drapers Assistant, his Stepfather/Uncle Richard, was working as a Dealer in feathers and Henry was working as a Warehouseman Assistant.

The family had two General Servants, residing with them, Jemima Roac and Caroline Curry.

5 Park Place, London is a 3-bedroom freehold terraced house – it is ranked as the 3rd most expensive property in N1 3JU, with a valuation of £1,432,000. Since it last sold in July 2016 for £1,450,000, its value has decreased by £18,000. It is now a sleek contemporary townhouse within a private gated mews, arranged over three floors with an allocated parking space. You can see what it looks like here.

Biggun’s Grandfather, George John Willats sadly died, on Saturday the 29th of April, 1871, at Number 53, Marshall Street, Golden Square, Westminster, London and Middlesex, England, aged 66. He died from Bronchitis. Maria Silvester of 53 Marshall Street, was present and registered his death on Thursday the 4th of May, 1871. She gave George’s occupation as a Pianoforte maker.

I do have a copy of his death certificate, which I was kindly gifted, so unfortunately I can not share it here but you can order your own copy of the certificate or a PDF certificate with the below information.

George John Willats was laid to rest, on Wednesday the 3rd May 1891, at Pancras Cemetery, Camden, London, England, in gave E10/39 with 12 other dear souls.

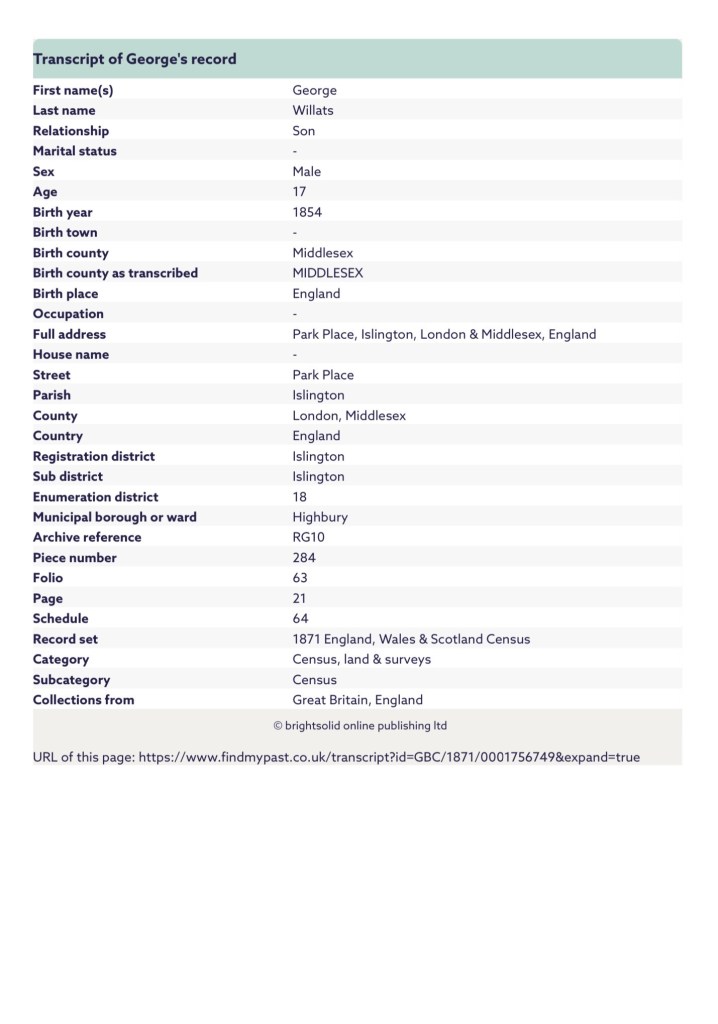

Biggun’s mum, Eliza, childbearing days were still in full flow and gave birth to hers and Richards 5th Son, Edwin Paul Willats, on Wednesday the 8th of November, 1871, at Number 5, Park Place, Highbury, Islington, Middlesex, England. Richard was working as a Commercial Buyer and he registered Edwin’s birth on Wednesday, December 20th 1871.

Biggun’s brother Edwin was baptised on Friday the 8th of December 1871, at the Parish Church of St Mary the Virgin, Islington, Middlesex, England. Richard’s occupation was listed as a Workhouse Man and their abode as 5 Park Place.

The Church of St Mary the Virgin is the historic parish church of Islington, in the Church of England Diocese of London. The present parish is a compact area centered on Upper Streetbetween Angel and Highbury Corner, bounded to the west by Liverpool Road, and to the east by Essex Road/Canonbury Road. The church is a Grade II listed building.

The churchyard was enlarged in 1793. With the rapid growth of Islington, it became full and closed for burials in 1853. It was laid out as a public garden of one and a half acres in 1885.

You can read more about St Mary’s here.

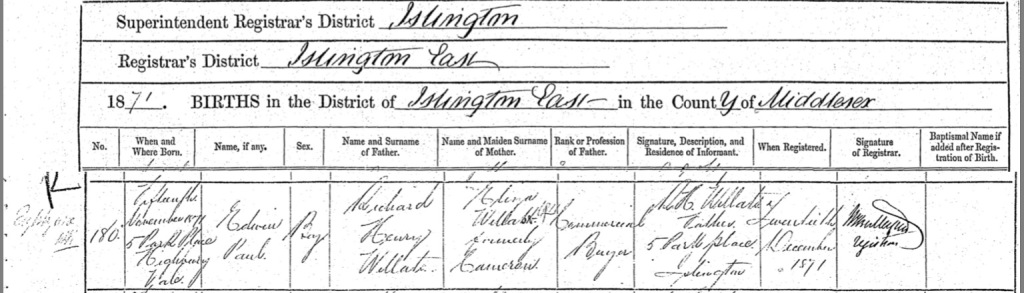

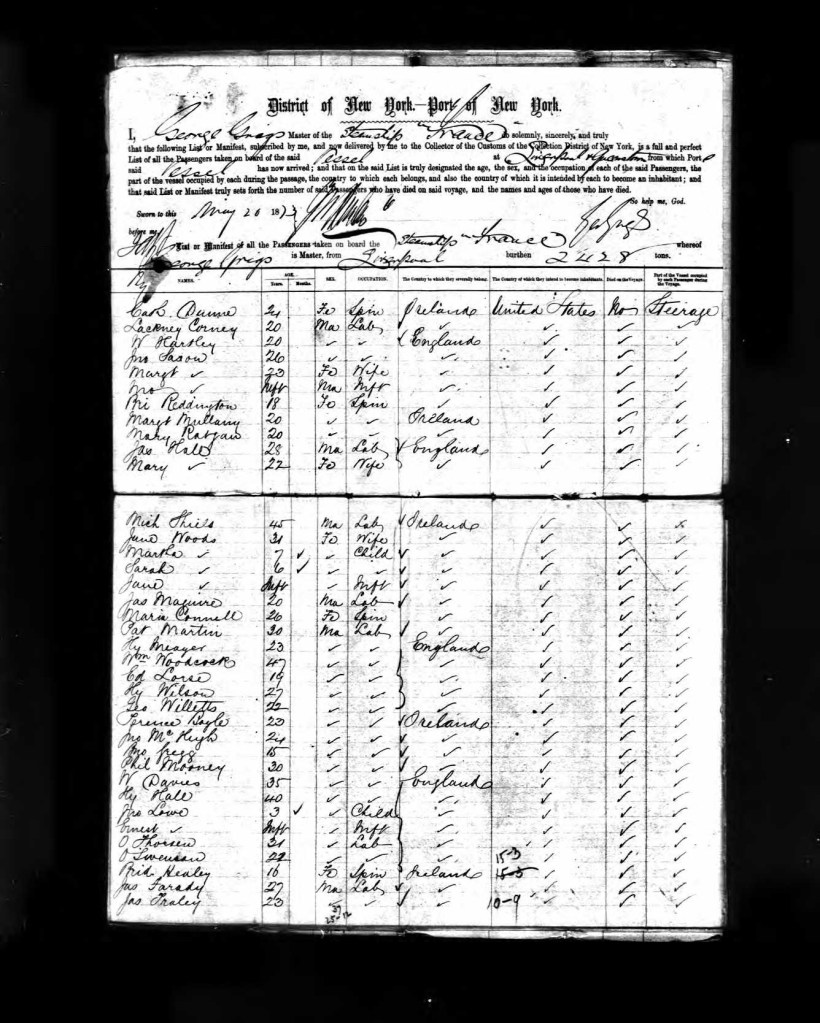

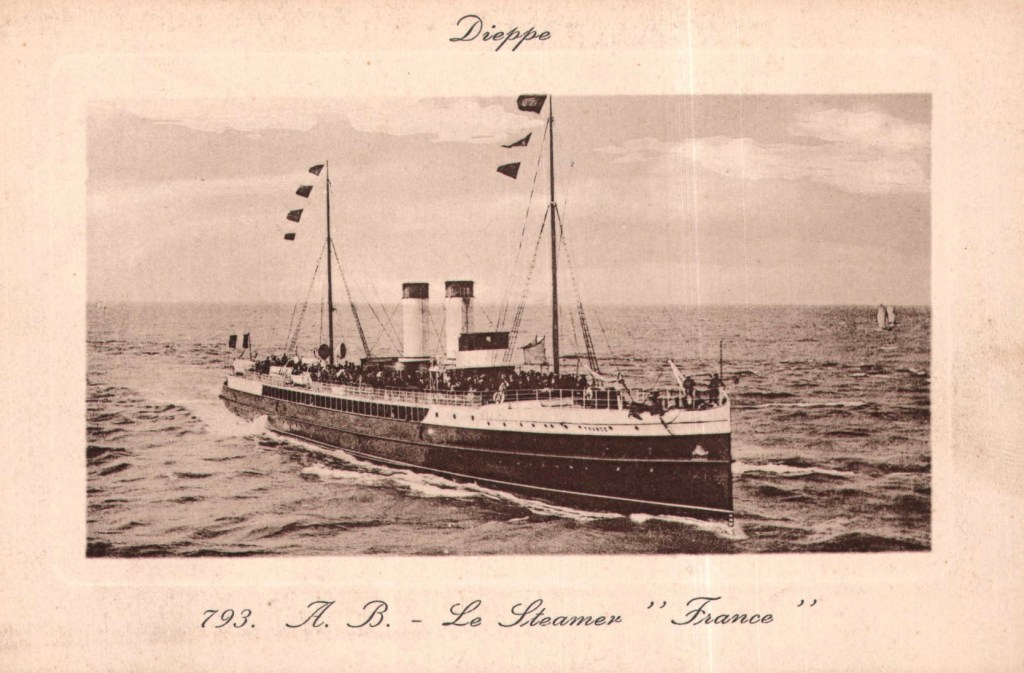

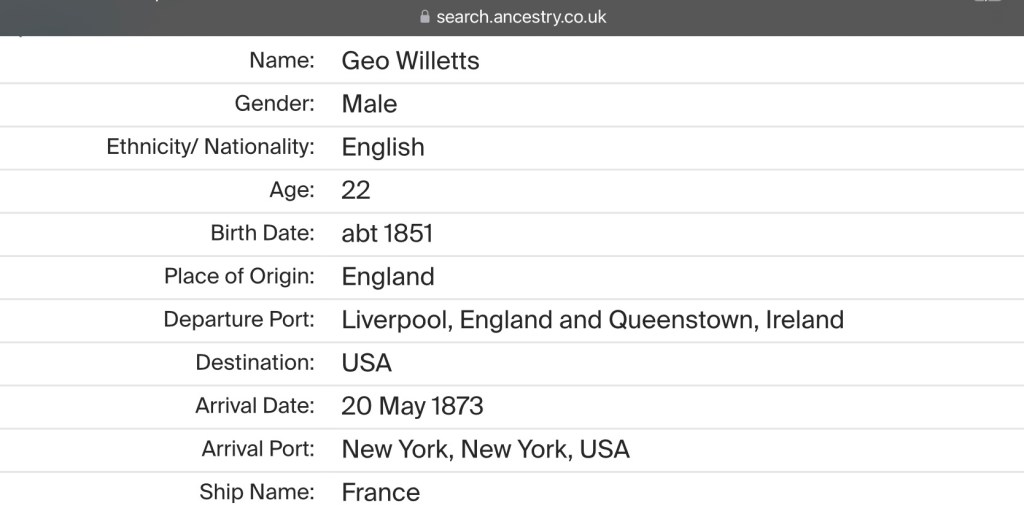

On Tuesday the 20th of May 1873, Biggun arrived at New York, United States of America, after travelling from Liverpool, London, England, aboard the, A. B. Steamer Le “France”.

There doesn’t seem to be much online about the “French” steamer, but you can see what it looked like in the photo below. However, The Caird Library holds five continuous editions, the third of which was published in 1973. This edition mentions that typical passage times from New York to the English Channel for a well-found sailing vessel of about 2000 tons was around 25 to 30 days, with ships logging 100-150 miles per day on average. The Caird Library holds five continuous editions, the third of which was published in 1973. This edition mentions that typical passage times from New York to the English Channel for a well-found sailing vessel of about 2000 tons was around 25 to 30 days, with ships logging 100-150 miles per day on average. Travel by sea in the late 18th & early 19th centuries was arduous, uncomfortable, and at times extremely dangerous. Men, women and children faced months of uncertainty and deprivation in cramped quarters, with the ever-present threat of shipwreck, disease and piracy.

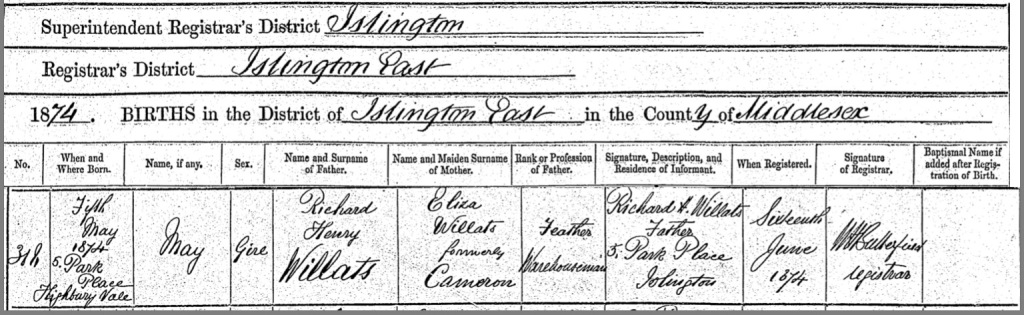

Biggun’s parents, Richard and Eliza, welcomed their 5th Daughter into the world on Tuesday the 5th of May, 1874, at 5 Park Place, Highbury, East Islington, England.

They named her May Claretta Willats.

Richard’s occupation was given as a Feather Warehouseman and he registered May’s birth on Tuesday the 16th of June 1874.

May Claretta was baptised on, the 9th of August, 1874, at Christ Church, Highbury, Islington, Middlesex, England. Richard gave his occupation as a Manufacturer and their abode as, Highbury. Christ Church, Highbury, is an Anglican church in Islington, north London, next to Highbury Fields.

Christ Church, Highbury, is an Anglican church in Islington, north London, next to Highbury Fields.

The site was given by John Dawes, a local benefactor and landlord, and the church was built by Thomas Allom in a cruciform shape with a short chancel, transepts, and nave from 1847 to 1848. Bridget Cherry and Nikolaus Pevsner write that Christ Church Highbury ‘is a successful and original use of Gothic for a building on a cruciform plan with broad octagonal crossing. The cross-plan with broad nave and crossing was popular for churches in the low church tradition where an effective auditorium for the spoken word was preferred to a plan designed for an elaborate liturgy.’

Since then, several changes have been made to the church, including the addition of a balcony in 1872, and new rooms for children’s work and fellowship in 1980.

On Wednesday the 1st September 1875, Biggun’s mum, Eliza gave birth to Percy Sidney Willats, at Richards and Eliza’s family home, Number 9, Park Place, Highbury, Islington, Middlesex, England. Richard gave his occupation as a, Fancy Warehouseman and their abode as, 9, Park Place, Islington, when he registered Percy’s birth on Saturday the 9th October, 1875, in Islington.

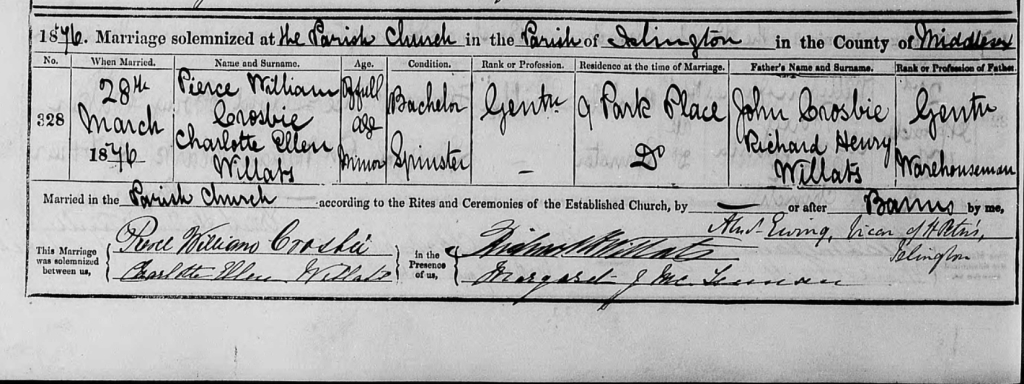

Biggun’s sister, spinster Charlotte Ellen Willats married bachelor, Pierce William Crosbie, on Tuesday the 28th of March, 1876, in St Mary’s Church, Islington, Middlesex, England. Charlotte was a minor and Pierce was of full age. Pierces occupation was given as a Gentu. They gave their residence as 9 Park Place and gave their fathers names and occupations as, Richard Henry Willats, a Warehouseman and John Crosbie a Gentu. Their witnesses were Richard Willats and Charlotte’s future sister-in-law Margaret Jane McLennon.

Around the year 1876, Biggun met a lady called Alice Maria Money, daughter of, John Money, a House Painter and Plumber and Mary Ann Money nee Skelton.

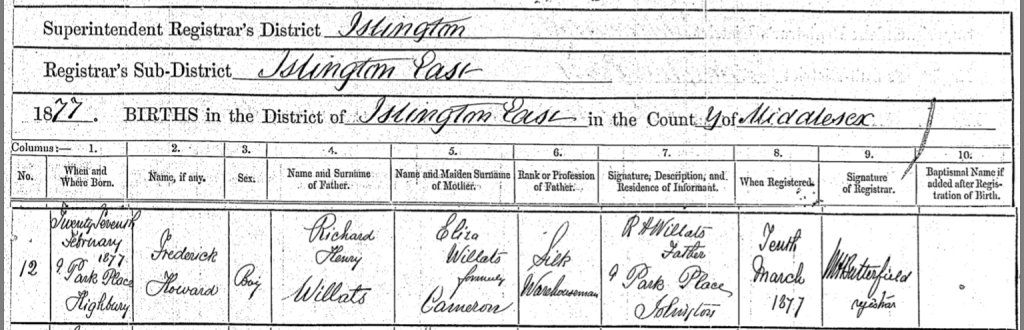

After many, many years of bearing children, Eliza, Biggun’s mum, gave birth to her 13th Child, a baby boy, on Tuesday the 27th of February 1877, at Number 9, Park Place, Highbury, Islington, Middlesex, England.

Richard and Eliza named him, Frederick Howard Willats.

Richard gave his occupation as a Silk Warehouseman, and their abode as, 9 Park Place, Islington, when he registered Frederick’s birth on the 10th of March 1877.

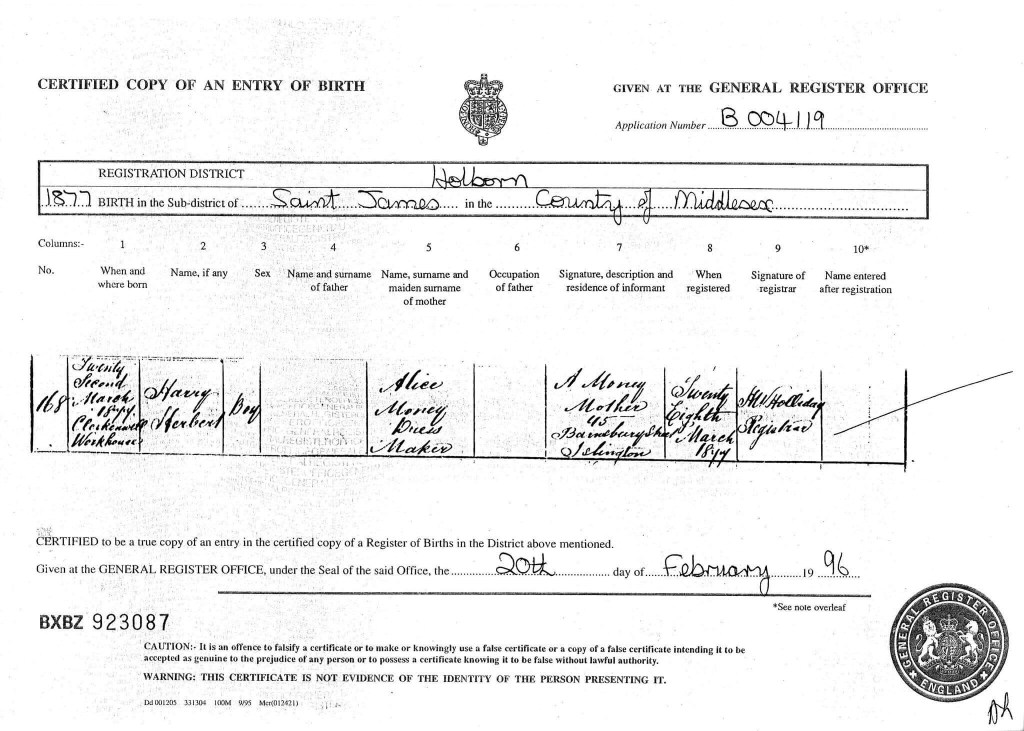

Biggun’s girlfriend/lady friend/partner, Alice Maria gave birth on Thursday the 22nd of March 1877, to a son in Clerkenwell Workhouse, Farringdon Road, Middlesex, England.

She named him, Harry Herbert Money.

Alice registered Harry’s birth on the 28th March 1877, in Holborn.

Alice gave her occupation is as a Dress Maker and her residence as Number 45, Bandbury Street, Islington, Middlesex, England.

Through DNA we can now prove that Harry is Biggun’s child.

The Clerkenwell Workhouse stood on Coppice Row, Farringdon Road, in London. The original workhouse was built in 1727 but that building was replaced by one twice as large in 1790. It was described by The Lancet in 1865 as one of the two worst in London, and “fit for nothing but to be destroyed” which it was in 1883.

In September 1865, Clerkenwell was the subject of one of a series of articles in the medical journal, The Lancet, investigating conditions in London workhouses and their infirmaries. The report revealed Clerkenwell as having some of the worst conditions of any workhouse infirmary in London. It reads,

CLERKENWELL INFIRMARY.

The infirmary of St. Martin-in-the-Fields be very bad, there can be no question that the infirmary of Clerkenwell is worse, in fact, we here touch the lowest point in the scale of metropolitan workhouse hospitals.

The parish of Clerkenwell elect its guardians and manages its workhouse under special local Act of Parliament, and it has certainly abused to the uttermost the opportunities for evading necessary reforms which are created by this position of affairs. The workhouse, in which there exists no trace of a proper separate infirmary, is a tall, gloomy brick building, consisting of two long parallel blocks separated from each other by a flagged court-yard not more than fifteen or twenty feet wide. The front and principal block do enjoy one fair outlook towards a wide street, but in other respects, the whole house is closely environed with buildings only less gloomy and unwholesome looking than itself. The hinder block, especially, wears an aspect of squalid poverty and meanness; and it is very old, dating from 1729. Both blocks are four stories in height. Entering either part of the house, we are at once struck with the frowsiness of the atmosphere that meets us; and we find the cramped winding staircases, interrupted by all manner of inconvenient landings and doors, which in these old buildings render the stairs a special nuisance, instead of an effective source of ventilation for the building, as they should be. Detailed examination of the sick ward implies detailed inspection of the whole house; for the sick, infirm, insane, and “able-bodied” wards are jumbled side by side, and the whole place presents the dismal appearance of a prison hospital — not such as one meets with in civil life, but the sort of makeshift which might perhaps be seen in a garrison town in war-time, except that in the latter situation one would not be annoyed by the shrieks and laughter of noisy lunatics — one of the special features of the Clerkenwell establishment.

The master is an excellent officer, accustomed all his life to the management of sick people, and with the valuable experience of a model prison (in which he formerly officiated) on matters of sanitary precaution ; and his efforts are well seconded by his wife, the matron. These officers work well with the surgeon, Dr. J. Brown, and the most zealous endeavours are made by them to remedy defects which are really irremediable. They have one paid nurse under them, who is an experienced and valuable woman, and with her assistance, as much supervision as possible is given to the incapable paupers who do the real bulk of the nursing. As far as the strictly medical service goes, the sharp supervision of the superior officers seems to prevent the possibility of any such scandalous inattention to the wants of the sick as was noticed at Shoreditch ; but the discovery which we made, that the disgusting practice of washing in the “chambers” was carried on in several of the infirm wards, sufficiently showed the character of the pauper attendants, and prepared us for the very qualified encomium of the master, who informed us that they were, on the whole, a sober, well-conducted set so long as they were never allowed outside the workhouse doors for a moment.

But it is the character of the wards, and their degree of fitness for hospital purposes, that we must chiefly pay attention to. It is necessary first to mention the elements of which the population is made up: in a total number of 560, which represents a crowded state of the house, there would be about 250 sick, and 280 infirm (including about 80 insane). This amount of population exceeds the Poor-law Board’s estimate by 60, and the consequence is a reduction of the cubic space per bed, on the average of all the sick wards, to 429 feet, which of itself implies a dangerous state of things. But this imperfect allowance of entire space is aggravated greatly by the low pitch of the wards, the very insufficient number of windows (which are only on one side, except in a few wards), and the absence of any free currents of air circulating through the house. Subsidiary ventilation has been attempted with much perseverance by the surgeon and the master, and a great mitigation is, doubtless, effected of what would be otherwise an intolerable and very fatal nuisance ; but still the atmosphere of the wards is very impure, and if the vigilance of the nurses, as is certain to be the case, at times relaxes, so as to allow the closing of ventilating orifices, a very dangerous foulness of air must ensue. And besides the deficiency of the wards generally in ventilation, there are some which are almost unique, we should fancy, for their badness in this respect. The four tramp wards (two male and two female) afford the following allowances respectively of cubic space — 120 ft., 240 ft., 198 ft., and 184 ft. — to each sleeper : and two of these apartments may dispute the palm successfully, for gloom and stifling closeness, even with the St. Martin’s tramp wards. In one there is actually no window at all, but only a bit of perforated zinc over the door, and a solitary ventilator of very doubtful utility. In these nasty places the “casuals” lie upon straw beds, spread upon a sort of wooden gridiron framework, and they must needs huddle so close as to be almost in contact with each other. (N.B. At Clerkenwell the tramps are not washed before being allowed to lie down.) The master is well aware how improper a lodgment these wards afford ; but, with the existing workhouse, it is impossible for him to find better accommodation for so many vagrants as he is obliged to admit.

Not to linger too long over the sanitary abominations of this house, we may mention one which seems to us most scandalous and disgraceful, but which the guardians, one can hardly help thinking, must have been led to establish by a sort of sentimental feeling. They placed the parish dead-house in a snug corner of the yard before-mentioned, and with a ventilation capable of wafting reminiscences of departed parishioners to the inmates of the wards whose windows overlook the mournful edifice.

Perhaps the most painful consequence of the inefficient lodgment which the house affords to its motley population is the impossibility of classification, even where this is most urgently needed. The arrangements for the insane afford a shocking example of this. Such a spectacle as is presented by the two wards in which the more serious male and female insane cases are treated is not often to be seen in these days of enlightened alienist management. The women’s ward, in particular, offers an instance of thoughtless cruelty which nothing call excuse the guardians for permitting. Twenty-one patients live entirely in this ward, which affords them an allowance of only 459 cubic feet each ; and the mixture of heterogenous cases which ought never to be mingled is really frightful. There is no seclusion ward for acute maniacs, and accordingly we saw a poor wretch who for five days had been confined to her bed by means of a strait-waistcoat, during the whole of which time she had been raving and talking nonsense, having only had two hours’ sleep : and there was the prospect of her remaining several days longer in the same condition. There were several epileptics in the ward, and one of them had a, fit while we were present, and there were imbeciles and demented watching all this with curious, half-frightened looks, which said very plainly how injurious the whole scene must be to them. We are willing to suppose that the guardians of Clerkenwell are unconscious of the great cruelty of allowing this wardful of women, who never ought to be associated, to sit gazing helplessly at each other, with no amusement but needlework, which they probably hate ; or of leaving a melancholic patient whom we saw in the male ward (and whose condition was assuredly improvable) to mope, with his head in his hands, the livelong day. For our own part, we have never seen a sight which more thoroughly shocked us by its suggestions of the unlimited power of stupidity to harass and torment the weak and sensitive. But assuredly the stupidity and the ignorance are in this case a fresh crime, for no one who undertakes to manage the insane has any right to plead ignorance of the conditions necessary to their welfare.

The defects of the Clerkenwell Workhouse are so manifest, the house is so clearly unfitted for the purpose to which it is applied, that it might be supposed that nothing but intentional cruelty could lead the guardians to the policy of retaining it. They have bad many opportunities in past years of selling their property for a sum which would readily have purchased a site in their own parish, and paid the expenses of a proper new building. But they have constantly refused to take advantage of this, and have continued their present residence till it is now almost certain that when they are forced to a removal they will have to take their workhouse out of the parish.

We sum up our observations, therefore, in the same tone as that in which we concluded our report on St. Martin’s. There is no remedy for the evils of Clerkenwell Workhouse but immediate removal, and the sooner the guardians put their house in order with a view to that course the better.

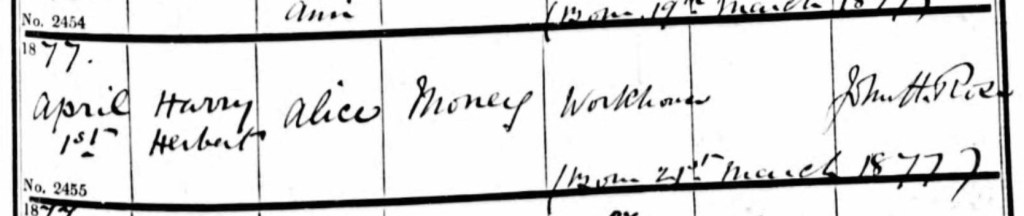

Harry Herbert Money, was baptised on Sunday the 1st of April 1877, at St. James Church, Clerkenwell, Middlesex, England. Harry’s and Alice’s abode was given as “Workhouse.” I think there is a great possibility that Biggun was not present.

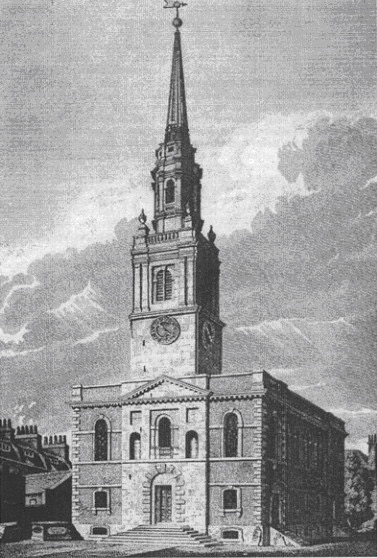

St James Church, Clerkenwell, is an Anglican parish church in Clerkenwell, London, England. By 1788 the old church, which was a medley of seventeenth and eighteenth century sections in various styles grafted onto the remains of the mediaeval nunnery church, presented an appearance of picturesque and dilapidated muddle. In that year an act of parliament was passed for the rebuilding of the church, the money to be provided by the sale of annuities. The architect was a local man, James Carr, and he produced a building which is pre-eminently a preaching-house but with carefully planned and harmonious detail clearly influenced by Wren and Gibbs. The new church was dedicated by Bishop Beilby Porteus in 1792. The upper galleries were added in 1822 for the children of the Sunday School, founded in 1807 and still flourishing; the back parts of the upper galleries were for the use of the poor. The tower and spire were restored in 1849 by W. P. Griffith and Sir Arthur Blomfieldrestored the church and rearranged the ground floor in 1882; both works were done very well. Inside, a noteworthy feature is the curved acoustic wall at the west end. The wall at the east end originally had painted panels in the Venetian window frame; the stained glass in the east windows is by Heaton, Butler and Bayne, 1863. The organ was built in 1792 by George Pike England to replace the one by Richard Bridge, which he took in part exchange. The new organ had three manuals, toe pedals and a Spanish mahogany case. This, together with much of England’s pipe work, still survives. The rococo detail is noteworthy, especially the carved drapery over the pipes. The organ was rebuilt by Noel Mander of Mander Organs in 1978, returning to the original style after some drastic alterations made in 1928. It now has 2 manuals and pedals and 22 speaking stops. There is a fine peal of eight bells in the tower, dating from 1791, though all the bells were recast in 1928. A print of the church, based on a drawing by Samuel Rawle, featured as the frontispiece of The European Magazine, volume 36, published 1 August 1799.

Alice gave birth to George Edwin Money, on Tuesday the 12th of August, 1879, at Number 29 Nichlos Street, Hoxton Old Town, Shoreditch, Middlesex, England.

No Father was named on his birth certificate, but DNA proves, that William George (Biggun) was his father.

Alice registered George Edwin’s birth on Tuesday the 23rd September 1879.

She gave her occupation as a Domestic Servant and her residence as, Number 29, Nicholas Street, Hoxton Old Town, Shoreditch, Middlesex, England.

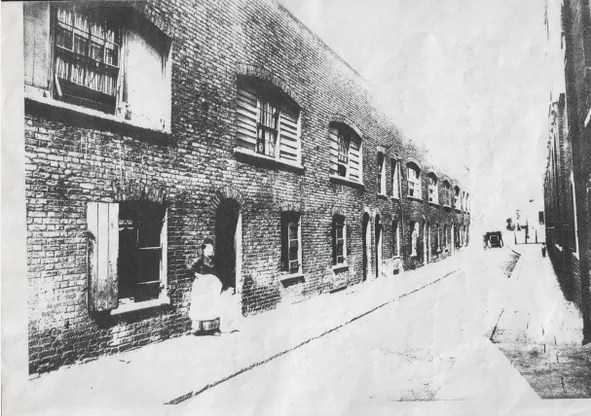

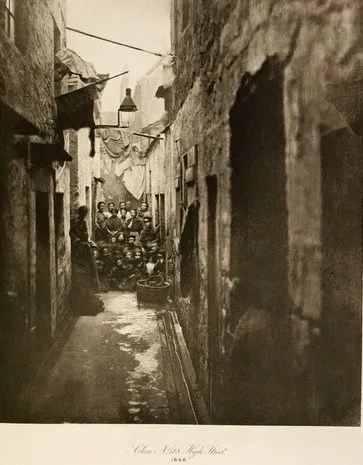

Nichols Street, I believe is now called Old Nichol Street, Shoreditch, was the worst of the Victorian slums. How awful it would have been to live in the slums of London. We really don’t know how lucky we are.

The Old Nichol’ was a Victorian slum – a rabbit warren of streets and passageways, situated just on the border between Shoreditch, Bethnal Green and he City.

Described by Sarah Wise in ‘The Blackest Streets: the life and death of a Victorian Slum’, the streets were so narrow that people had to ‘turn sideways, and move crablike along’. It was also a criminal enclave… with its strange geography assisting a street robber or sneak thief in his dash to safety.

Speculative builders had leased land from aristocratic owners, who didn’t care what was done with their land as long as it remained profitable. Wise continues: ‘Instead of using traditional mortar, the speculative builders found a cheaper lime-based substance derived from the by-products of soap-making. This ‘cement’ was known as Billysweet, and quickly became infamous for never thoroughly drying out, and so leading to sagging, unstable walls… Most of the early-1800s houses had no foundations, their floorboards being laid onto bare earth; cheap timber and half-baked bricks of ash-adulerated clay were used. Roofs were badly pitched, resulting in rotting rafters and plasterwork, with this damp from above joining the damp seeping upwards for the earth to create permanently soggy dwellings.’

A two-roomed tenement in Ann’s Place, a little court off the western edge of Boundary Street, is described by Sarah Wise: ‘walls are running with damp, and the meagre fire burning in the grate has drawn some of the moisture out of the plaster, creating a small local fog. This is home to a married couple with six children. There is no bed, and when you ask them how they sleep, the wife replies, ‘Oh, we sleep about the room how we can’. Walk through a hole in the wall into the second room and you’ll see the husband and two adolescent sons making uppers for boots. They are so busy they don’t even look up or gesture; they are haggard and hollow-cheeked.’

Demolition of The Old Nichol slums began in 1893, and the building of the new ‘Boundary Street Estate’ started in 1895.

Biggun’s brother, 24-year-old, bachelor, and publican, Henry Richard Willats married 23 year old, spinster, Amelia Etheredge, daughter of John Etheredge, on Tuesday the 30th of March, 1880 at All Saints Church, West Ham, Essex, England. Henry gave his residence as West Ham and Amelia as, Saint Paul’s, Shadwell. They gave their fathers names and occupations as, Richard Henry Willats, a Licensed Victualler and John Etheredge, an Engineer. Their witnesses were Charles Henry Etheredge and Alice Catherine Etheredge.

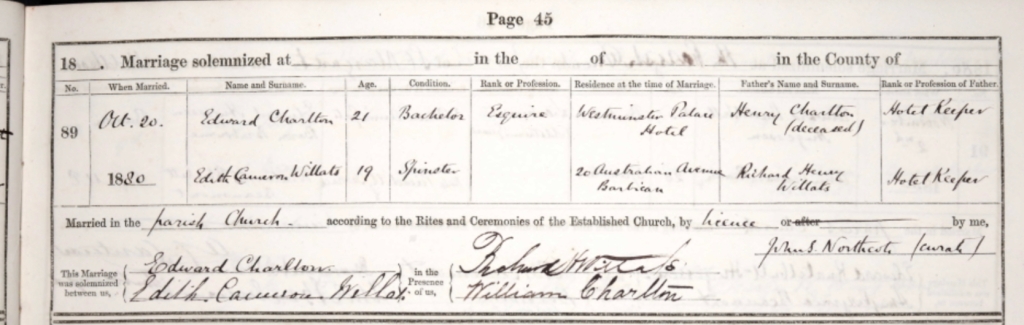

And Biggun’s sister, 19-year-old, spinster, Edith Cameron Willats married 21-year-old Bachelor, Edward Charlton, an Esquire, on Wednesday the 20th of October, 1880, at St Margaret Church, George Hanover Square, Westminster, London, England. They gave their fathers names and occupations as, Richard Henry Willats, a Hotel Keeper and Henry Charlton, a Hotel Keeper. Edith gave her residents as, 20 Australian Avenue, Barbican, Silk Street, St Giles, Westminster, London, England and Edward gave his as Westminster Palace Hotel. Their witnesses were, Richard Willats and William Charlton.

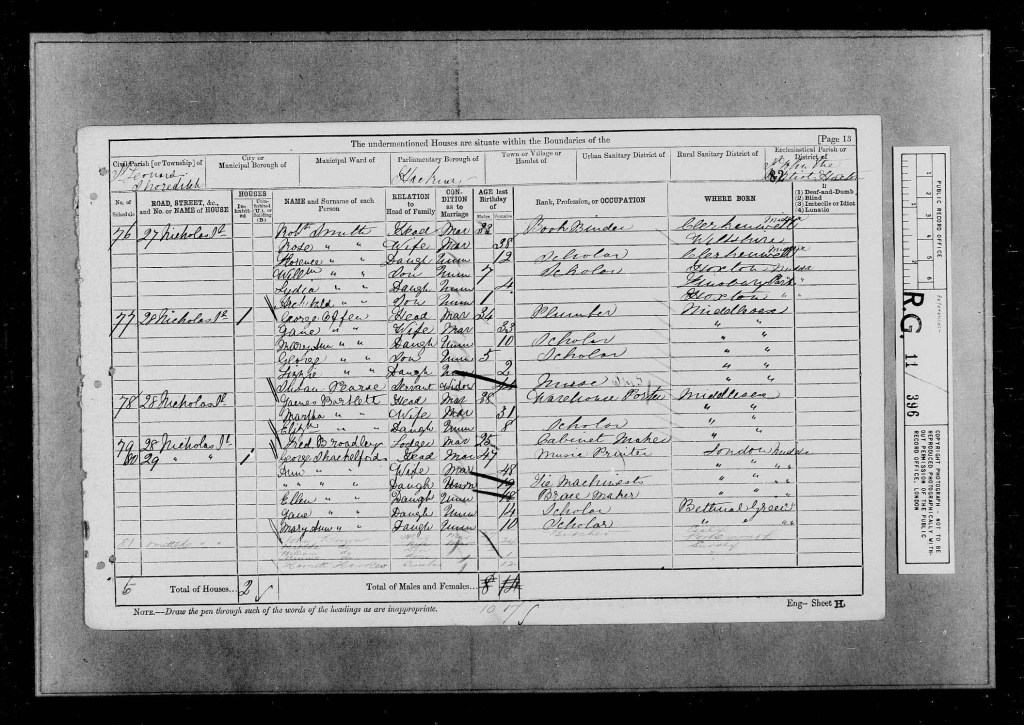

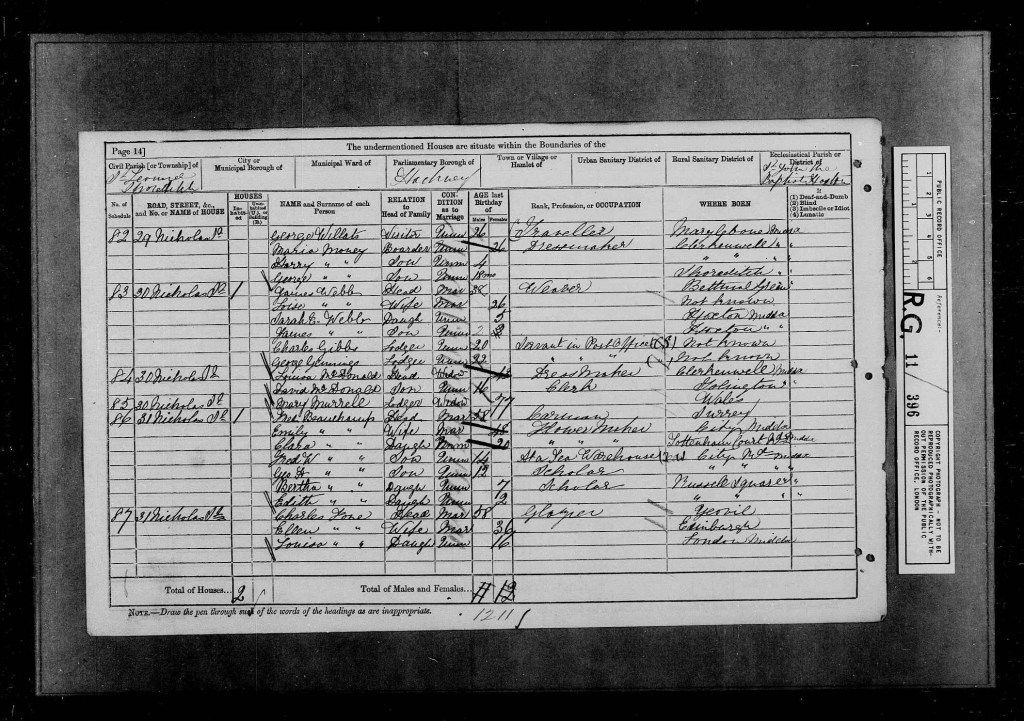

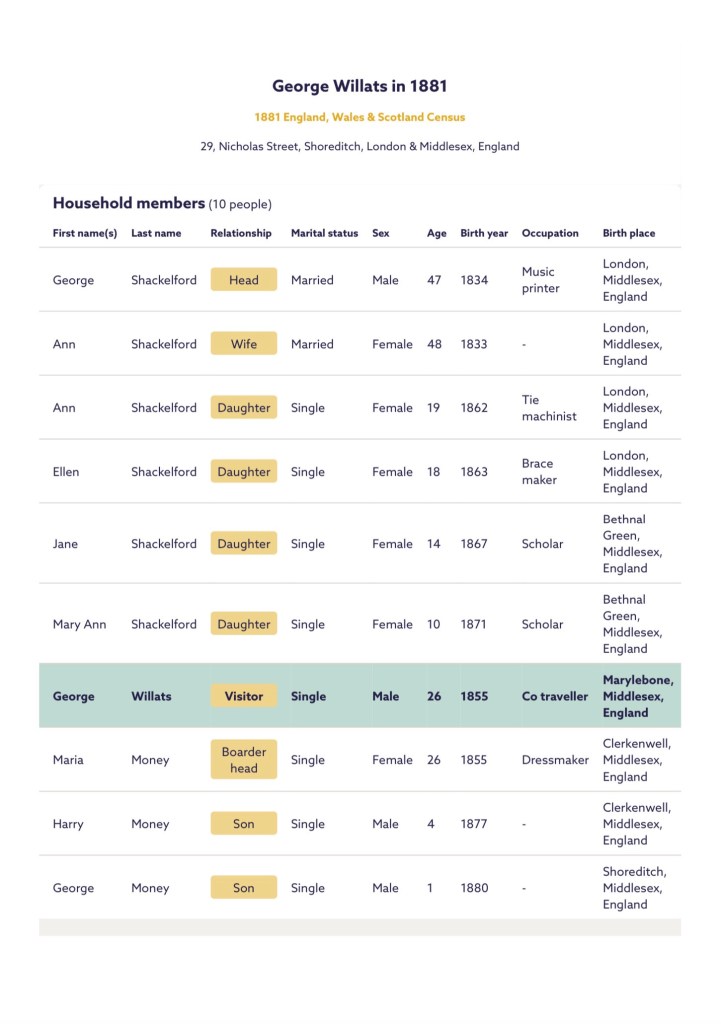

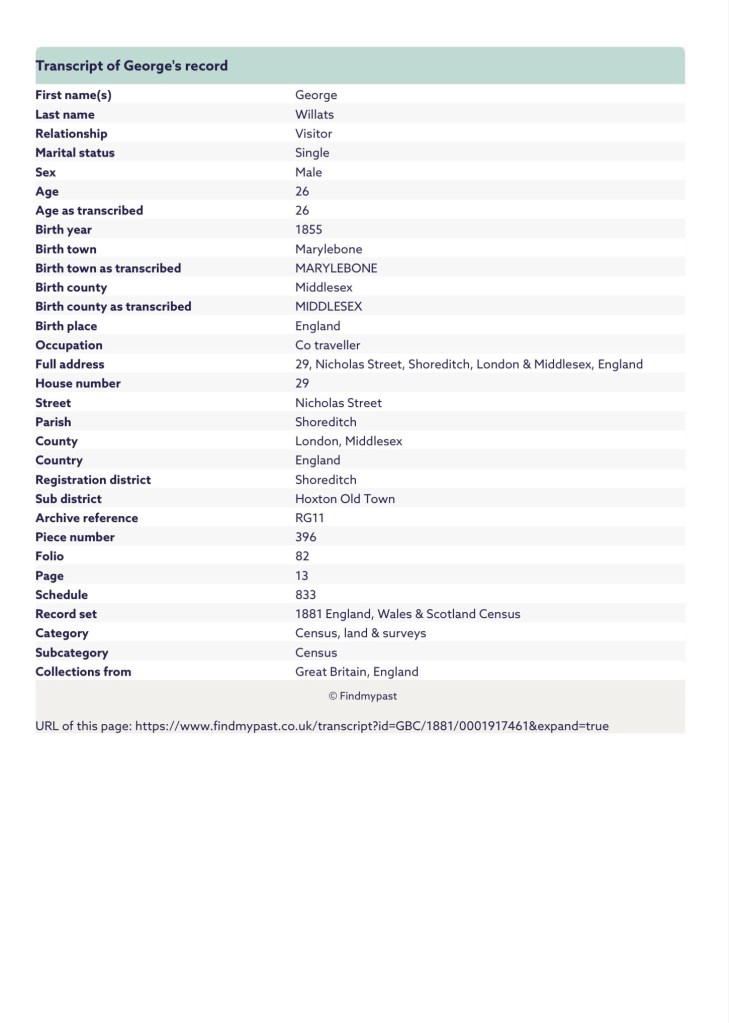

The 1881 census was held on the eve of Sunday the 3rd of April 1881. It shows that Biggun was visiting Number 29, Nicholas Street, St Leonard, Shoreditch, London, England, where Alice Maria Money and their two sons Harry and George Money, were boarding at the home of George Shackelford.

Biggun was working as a commercial traveller and Alice Maria was a Dressmaker.

Alice was named under her middle name Maria.

The occupation of commercial traveller emerged during the eighteenth century in the form of bagmen, who rode on horseback to distribute goods to trade customers who were either retailers or manufacturers. As such they were distinct from peddlers who sold goods directly to the public at fairs. They displayed goods, samples or trade catalogues to customers; obtained orders; and collected and remitted payments on previous orders. Moreover, commercial travellers were important sources of intelligence about the affairs of their customers, the activities of competitors and the general state of business. Their role in Britain attracted attention from pioneering individual studies by Jeffreys, Payne and Westerfield, but generally, business historians treated them as largely invisible foot-soldiers, their qualities and effectiveness were assumed, in effect, to reflect general characteristics of firms, industries or economies. Critical appraisals of British entrepreneurship compared British travellers unfavourably with multilingual and well-resourced German salesmen capturing British export markets, particularly in engineering.

Equally the innovative marketing techniques of large-scale American corporations were taken as markers of British backwardness in some consumer goods trades. For Chandler or Friedman, small and medium-sized British companies lacked the capacity to develop their marketing capabilities and larger firms were too cautious to undertake the required combination of innovations in production, marketing and managerial hierarchies. From these perspectives, British salesmen were either poorly equipped in terms of education and expertise or deprived of the key tools of a modernising trade by conservative employers who took no interest in or actively rejected new practices.

In these analyses the key issues were the organisational structures within

which commercial travellers operated and the character of their sales practices. Structurally salesmen either worked for wholesalers or agencies, who distributed goods on behalf of many producers or they were employed directly by manufacturers. The use of wholesalers or agency houses was well-established by 1850 with some specialising on overseas trade. Chapman emphasised the key role of merchant houses, especially in London, for Britain’s textile trade. Where industries clustered in particular districts, such as the Sheffield cutlery, West Midland hardware or Birmingham jewellery trades, wholesalers were closely linked to the numerous small and medium-sized enterprises. These industrial districts allowed small manufacturers to reap the advantages of specialisation in production and access to skilled labour and to draw on the services of the wholesalers to maximise the distribution of their products in an alternative paradigm to that of volume production and distribution within a single large firm. For manufacturers, selling via wholesalers reduced overhead costs plus the time and expense required to establish connections with large numbers of individual retailers. In the most direct defence of British sales methods, Nicholas argued that merchant houses were highly effective mechanisms for reducing risks in distributing generic products, that manufacturers deployed their own travellers or those of agencies in a sophisticated way and that extensive overseas branch networks were evidence of initiative and enterprise. More recently, Hannah emphasised that decentralised systems of production and distribution were well-adapted to serving the densely-clustered urban economy in Britain supported by sophisticated transport, and financial and commercial infrastructures.

Nonetheless by 1900 some manufacturers were directly hiring their own salesmen particularly in the grocery and branded consumer goods sectors, textiles and drapery, which were also among the first mover industries in North America and Europe. Where a manufacturer had a distinctive brand, establishing their own salesforce increased their capacity to influence the effort devoted to their selling own goods compared with agents who represented several brands. Closer contact with customers offered greater scope to promote repeat business and to acquire information about market conditions. Not all industries were suited to direct marketing by manufacturers, particularly where products remained essentially generic, hence the persistence of wholesalers and agents. And not all firms possessed the scale, capital or initiative required to engage salesmen, so in many sectors, direct selling by manufacturers co-existed with the use of wholesalers and agents.

The entry of manufacturers into wholesaling via their own salesmen has also been associated with the modernisation of sales methods that, arguably, changed the appearance, style and behaviour of salesmen, a shift encapsulated in the shift from the commercial traveller to the sales representative.

Biggun’s brother, 23-year-old, bachelor, Francis Montague Allen Willats, married 25-year-old, spinster, Margaret Jane McLennon, at Saint John the Evangelist, Gloucester Drive, Finsbury Park, Hornsey, Middlesex, England, on Wednesday the 6th of July, 1881. Francis was working as an agent at the time of his marriage. They gave their fathers names and occupations as Richard Henry Willats, an Agent and John McLennon, a Chronometer Maker. Francis gave his abode as, 145 Blackstock Road and Margaret gave hers as, 84, Finsbury Park Road. Their witnesses were John McLennon and Jessie McLennon.

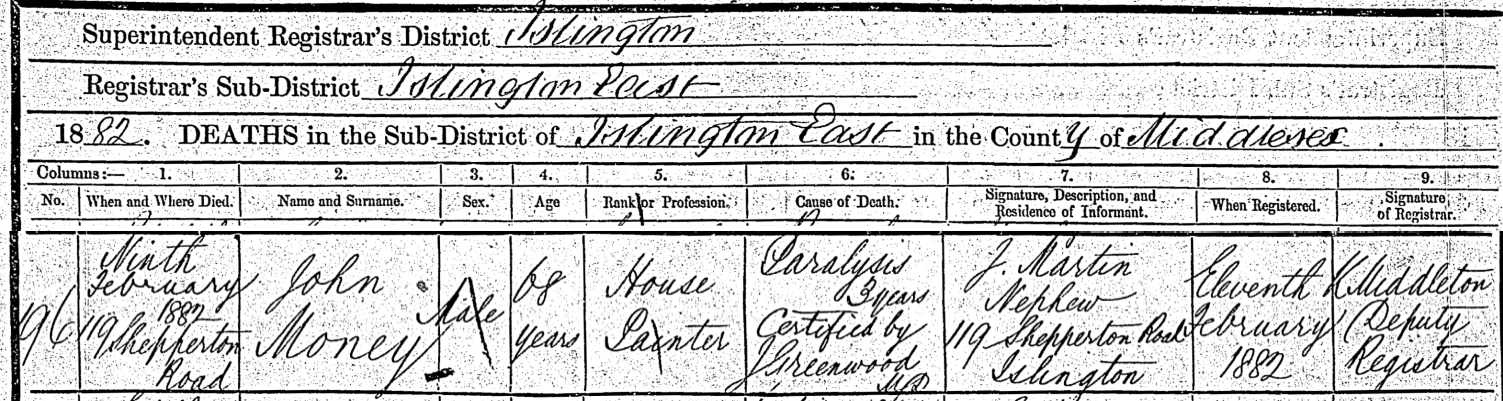

Alice’s father John Money, died on February the 9th of 1882, when he was 68 years old at Number 119, Shepperton Road, Islington, Middlesex, England. His cause of death was from Paralysis, 3 years. John’s nephew, J Martin, registered his death on the 11th of February 1882. John’s profession was given as House Painter on his death certificate.

You may be wondering why I have mentioned Alice’s fathers death. Well, it’s believed he had a massive part to play in why Alice and Biggun hadn’t already married and had their children born into wedlock. Family stories have it that John Money was for some unknown reason was totally against their union and refused them to be together. So we believe his death played its part in what was to come of Biggun and Alice.

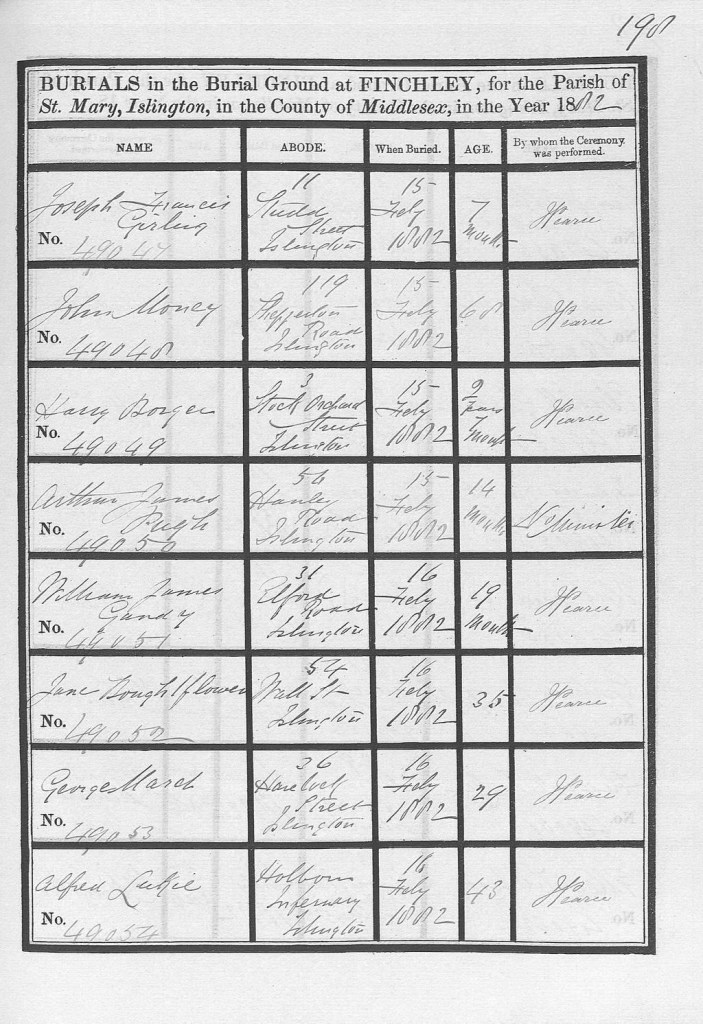

Alice Maria, and her family, laid Alice’s father, John Money, to rest on the 15th of February, 1882, at Islington Cemetery, Islington, Middlesex, England, in Grave Reference – Z/3/10669. He was buried with 10 other lost souls, Mary Ann White, Alice Coleman, John Pace, Mabel Louisa Jenkins, Flora Rosanna Morris, William George Demmon, Hannah Robinson, George March, Charlotte Hammerton and Ann Usher.

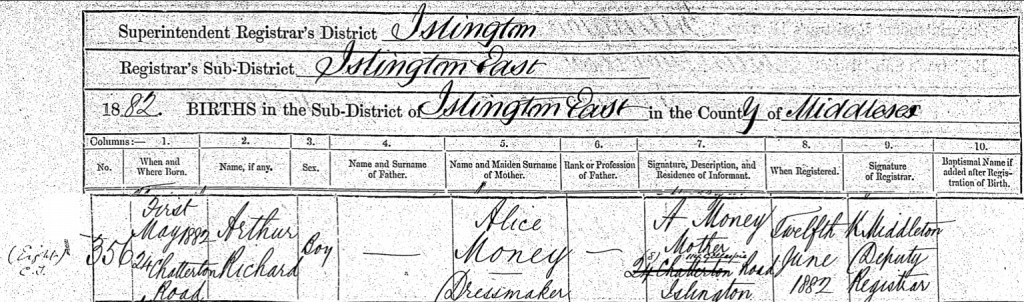

Biggun and Alice Maria, were once again expecting and had a 3rd Son, out of wedlock.

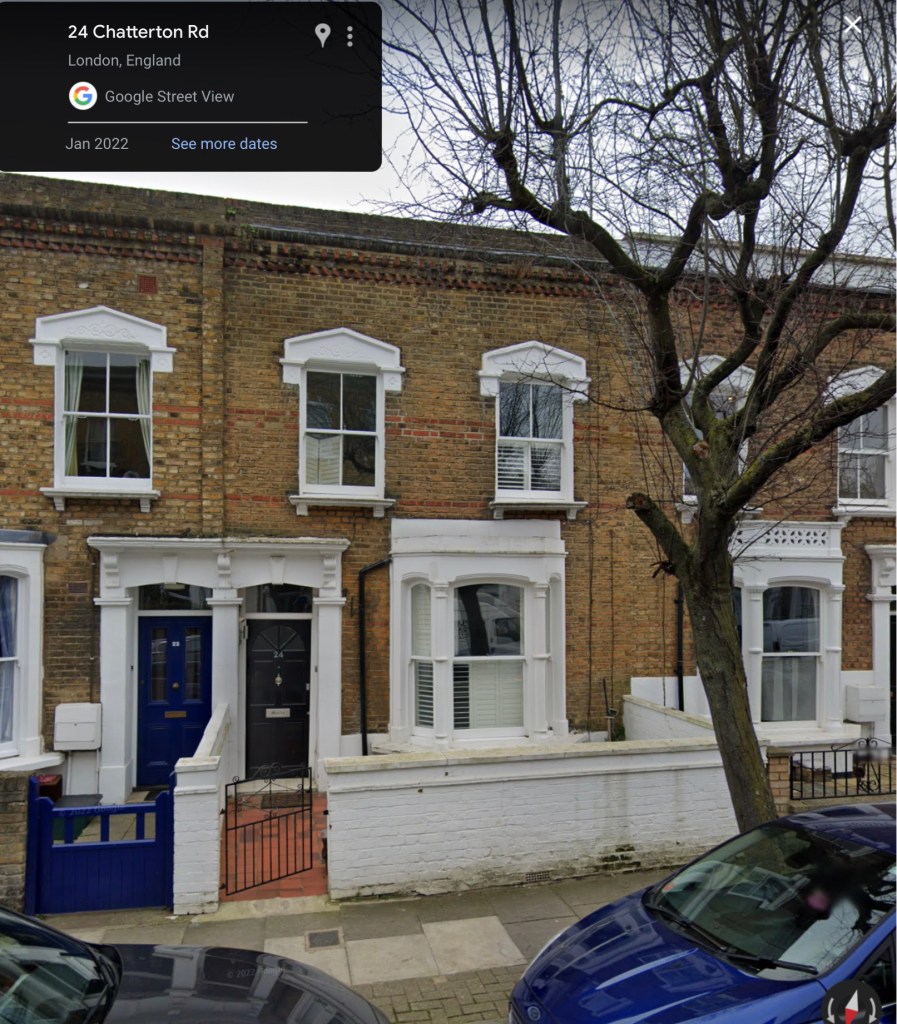

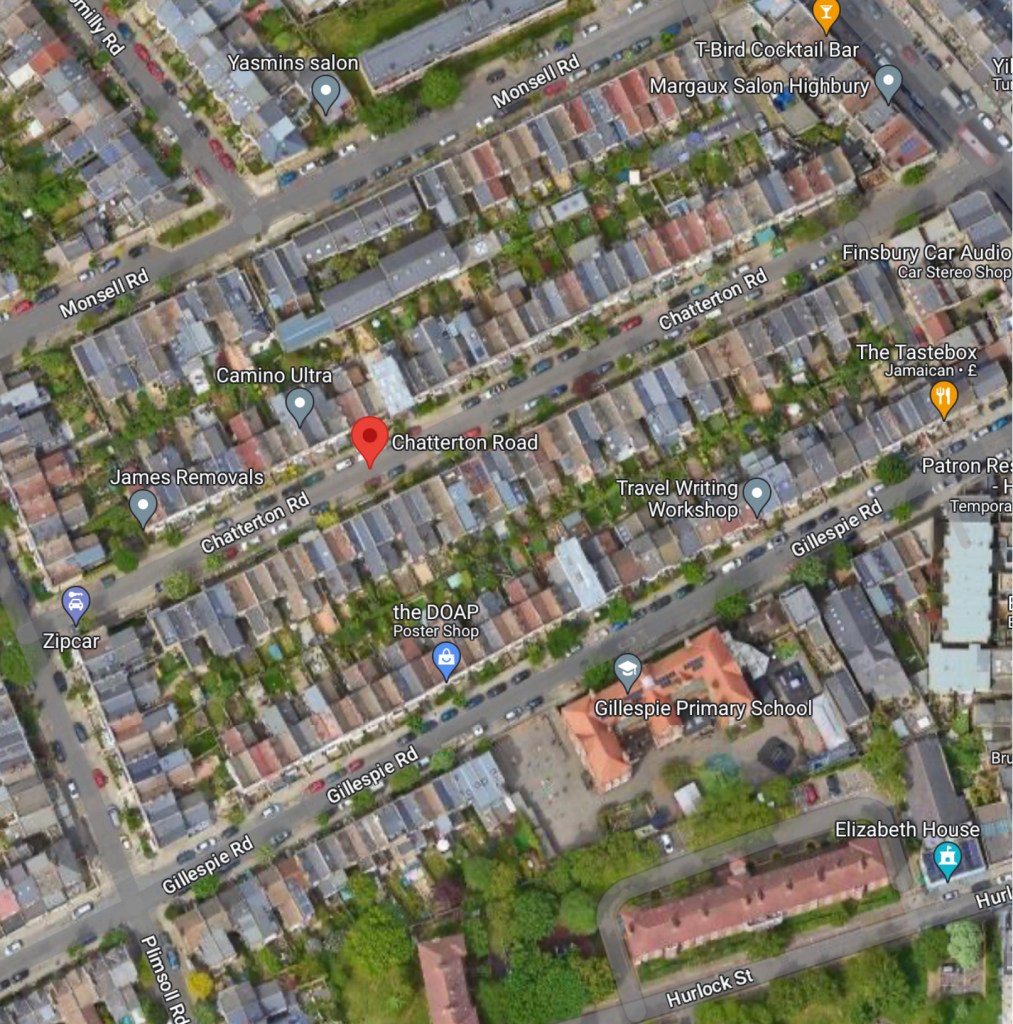

Arthur Richard Money was born on Monday the 1st of May, 1882, at 24 Chatterton Road, Islington, Middlesex, England.

Alice registered Arthur’s birth on the 12th of June, 1882, in Islington.

She gave her occupation as a dressmaker and her abode as, 11, Gillespie Road, Islington.

Alice once again, did not name the father, but we are 100% sure Biggun was Arthur’s biological father.

DNA is a fascinating thing.

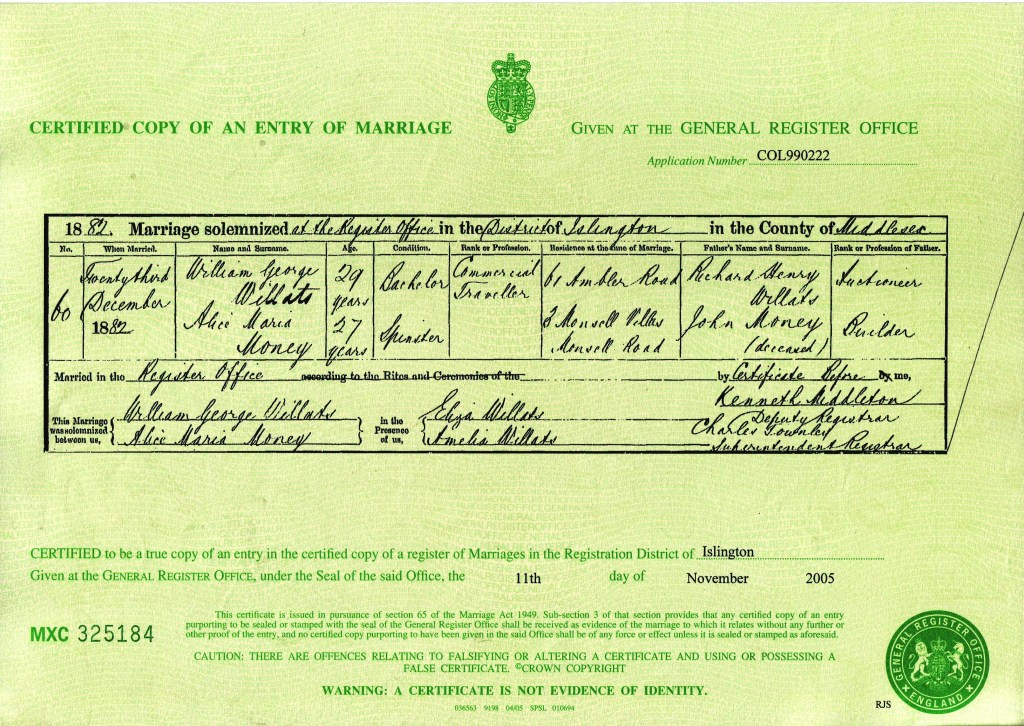

29-year-old, bachelor William George Willats, a Commercial Traveller, married 27-year-old spinster, Alice Maria Money, at The Register Office, Islington, Middlesex, England, on Saturday the 23rd of December, 1882.

William gave his occupation as a Commercial Traveller. William gave his abodes as, 61 Almbler Road and Alice’s as, Number 3, Monsell Villas, Monsell Road, Islington.

They gave their fathers names and occupations as, Richard Henry Willats, an Auctioneer, and John Money (deceased) a Builder.

Their witnesses were, Eliza Willats and Amelia Willats.

As I close the first chapter all about of my 3rd great grandfather Biggun’s childhood, I am filled with a profound sense of wonder and connection. Exploring the tales of his early years has been a journey of discovery, weaving together the threads of history and family lore. In retracing his footsteps, I have been transported to a time long past, where innocence and simplicity embraced each other, and the seeds of his future were sown.

Through the fragments of faded documents, I have caught glimpses of a world that shaped his character, instilling in him values and wisdom that transcended generations. It is in these treasured moments that I find a deep appreciation for the resilience and determination that marked his path.

As I reflect on my 3rd great-grandfather’s childhood, I am reminded of the power of heritage, the importance of preserving our stories, and the impact of the past on our present. Each anecdote and reminiscence has enriched my understanding of who I am and where I come from, fostering a stronger connection to my roots and a profound sense of gratitude for those who came before me.

Though the era may have changed, the essence of childhood remains timeless—a time of imagination, curiosity, and boundless dreams. As I bid farewell to this chapter of the past, I carry with me the legacy of my 3rd great-grandfather’s youth—a legacy that continues to shape and inspire my own journey.

As I step back into the present, I am filled with a newfound sense of purpose to honour the spirit of those who paved the way for us and to continue cherishing the stories that make us who we are. My 3rd great-grandfather’s childhood is etched forever in our family’s history, an irreplaceable part of our collective identity.

May the stories of his early years continue to live on, inspiring generations to come, and reminding us all of the enduring power of our shared heritage.

With this, I bid you farewell and hope to see you back here soon for the second instalment of Biggun’s life journey.

Too-da-loo for now.

🦋🦋🦋

I have brought and paid for all certificates,

Please do not download or use them without my permission.

All you have to do is ask.

Thank you.

Pingback: The Life Of Lilly Jenny Willats, 1869-1947, The Early Years, Through Documentation. | Intwined

Pingback: The Life Of, Edwin Paul Willats, 1871-1920, The Early Years Through Documentation. | Intwined

Pingback: The Life Of, May Willats, 1874-1934, The Early Years, Through Documentation. | Intwined