In the quiet embrace of a family home, nestled within the heart of All Souls, Middlesex, a new chapter unfurled on an ominous Friday, the 13th of January, 1865. Within the walls of Number 37, Charlotte Street, Marylebone, a child was born, a child destined to inscribe his name into the annals of our family’s legacy. This child was Walter James Willats, a beacon of a bygone era whose life story, though veiled in the mists of time, resonates through the corridors of our heritage. The mere mention of Friday the 13th often conjures superstitions and whispered tales of ill omens, but for Walter, this date was the herald of his entrance into a world brimming with possibilities and woven with the threads of an era in transition. Amidst the gentle hum of a household steeped in history, his first cries echoed, weaving him into the intricate tapestry of our ancestry. Within the confines of Middlesex, young Walter embarked upon a journey that intersected with the pulse of an evolving era, where horse-drawn carriages traversed cobbled streets, and the heartbeat of London reverberated with the hustle and bustle of progress. His life story, though shrouded in the veils of time, bears witness to a landscape of moments, moments that breathed life into the narrative of our family’s past. As we embark on this odyssey to uncover the life and times of Walter James Willats, we are not merely recounting history; we are unraveling the essence of a man whose footsteps echoed through an era marked by perseverance, courage, and a spirit unyielding in the face of the unknown. Join me in this pilgrimage through time, where the pages of history unveil the chapters of a life lived amidst the whispers of a changing world, a life that still echoes within the corridors of our heritage. So without further ado I give you.

The Life Of

Walter James Willats,

1865-1929,

The Early Years.

Welcome to the year 1865, Marylebone, England. Nestled within Middlesex, Marylebone in 1865 is a bustling district pulsating with life, albeit with a distinct Victorian charm. Queen Victoria, in the 28th year of her reign, casts her regal presence over the nation, while the esteemed Lord Palmerston serves as Prime Minister, guiding the affairs of the country through a tumultuous period.

Parliament, the epicenter of political discourse, echoes with debates ranging from matters of empire to the plight of the working class. The Reform Act of 1867 looms on the horizon, promising expanded suffrage and political representation.

Fashion in Marylebone reflects the prevailing Victorian sensibilities, with women adorning themselves in voluminous skirts and corsets, while men favor tailored suits and top hats. Yet, amidst the elegance, there exists a stark dichotomy between the opulence of the elite and the modest attire of the working class.

Electricity and sanitation are emerging concerns in the city. Gas lamps still illuminate the streets at night, casting an ethereal glow over cobblestone pathways. Meanwhile, efforts to improve sanitation aim to combat the pervasive stench of sewage that often permeates the air.

The atmosphere in Marylebone is one of both progress and tradition. The clatter of horse-drawn carriages intermingles with the sounds of bustling markets and street vendors hawking their wares. Aromas waft through the air, from the scent of freshly baked bread to the pungent tang of industrial smoke.

Entertainment flourishes in Marylebone, offering respite from the rigors of daily life. Music halls and theaters showcase the talents of actors and musicians, while public houses provide a convivial atmosphere for socializing and gossiping.

Transportation options include horse-drawn omnibuses and the newly introduced steam trains, offering swift travel to and from the city center. Gossip abounds in Marylebone, with whispers of scandal and intrigue circulating among the social elite and working-class alike.

The disparity between the rich and the working class is glaringly evident in Marylebone. While the affluent reside in elegant townhouses and enjoy lavish amenities, the poor struggle to make ends meet in cramped tenements, often facing dire living conditions and limited opportunities for advancement.

Nutrition and health vary widely depending on social class. The wealthy indulge in elaborate feasts featuring delicacies from around the world, while the working class subsists on simpler fare such as bread, cheese, and ale. Health concerns are prevalent, with infectious diseases such as cholera and tuberculosis claiming lives with alarming frequency.

Against this backdrop of daily life, Marylebone bears witness to significant historical events. The end of the American Civil War in 1865 brings relief and uncertainty in equal measure, while the ongoing debate over parliamentary reform promises to reshape the political landscape for years to come.

In 1865, Charlotte Street, Marylebone, within the All Souls district of Middlesex, England, is where our life story begins.

Charlotte Street, exudes an atmosphere steeped in Victorian charm and bustling activity. The street, lined with elegant Georgian and Victorian townhouses, serves as a microcosm of the broader society of the time.

Here, amidst the polished facades and wrought-iron railings, residents of varying social classes coexist, each contributing to the tapestry of life in Marylebone. The affluent denizens of the neighborhood inhabit the stately homes, their windows adorned with lace curtains and flower boxes, while the working class resides in more modest accommodations, tucked away in the back alleys and mews.

Charlotte Street is alive with the sounds of daily life. Horse-drawn carriages clatter along the cobblestone thoroughfare, their hooves echoing off the brick facades. Pedestrians bustle along the sidewalks, their footsteps mingling with the chatter of street vendors and the calls of children at play.

At night, gas lamps cast a soft glow over the street, illuminating the way for revelers returning from the theaters and music halls that dot the neighborhood. Public houses hum with activity, their doors thrown open to welcome patrons seeking respite from the rigors of the day.

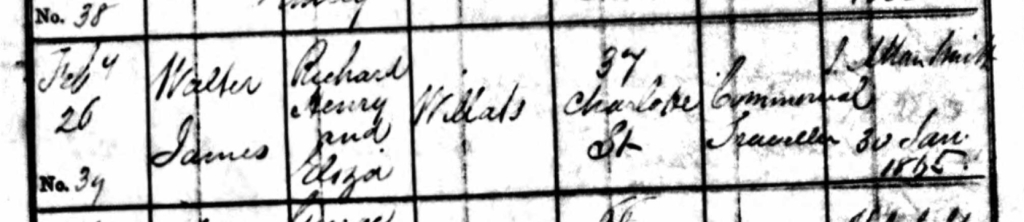

It was behind one of Charlotte Streets doors that, Walter James Willats, was born on Friday the 13th January 1865, at the families home, Number 37, Charlotte Street, Marylebone, All Souls, Middlesex, England, to my fourth Great Granduncle, Richard Henry Willats, my 4th Great-Granduncle and Eliza Willats nee Cameron, my fourth Great-Grandmother who had previously been married to my fourth Great-Grandfather, George John Willats, whom was Richard Henry Willats’ Brother (Walter James’ uncle).

Walters father Richard Henry Willats, registered Walters birth on Thursday the 9th of March 1865.

He gave his occupation as a commercial traveller and their abode as, 37, Charlotte Street.

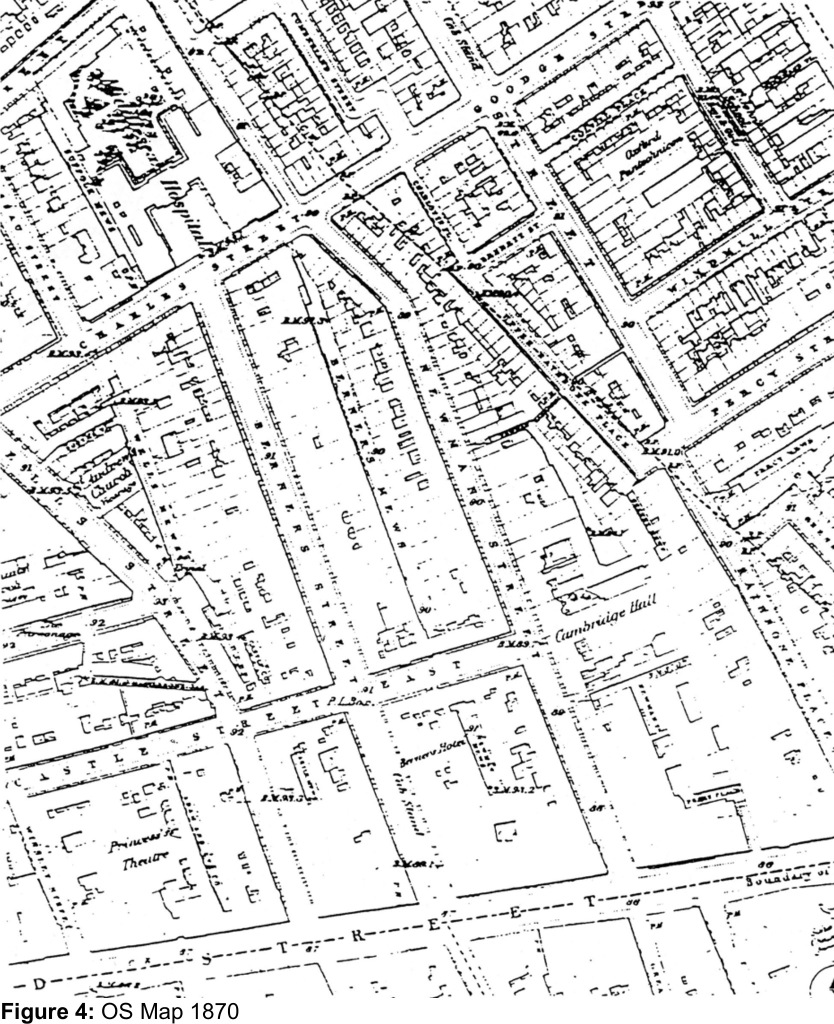

Charlotte street which seems to have been named after Queen Charlotte runs from south to north from Percy Street to Howland Street. The original Charlotte Street extended to Goodge Street, and from thence to Tottenham Street it was called Lower Charlotte Street, the remainder being known as Upper Charlotte Street. In 1766 building was proceeding on its western side as shown by a lease from the Goodge Brothers to William Franks, gentleman, of Gerrard Street (afterwards of Percy Street, q.v.), of ground adjoining west on ground late Marchant’s Waterworks, south on ground whereon is late erected a chapel also let to him and north on Bennett Street. The Waterworks are shown on Rocque’s Plan of London (1746), and Percy Chapel stood on the west side of Charlotte Street immediately opposite the end of Windmill Street. Charlotte Street is typical of the late 18th-century development of this area and its present condition is therefore described in this section in some detail. The houses have been re-numbered twice since they were first numbered, the present sequence running from south to north, with the odd numbers on the west and the even on the east side. The progress of erection was in the same direction and except for the breaks at the cross streets the houses were (before the war) in uninterrupted rows like those in Percy Street.

Charlotte Street, West side: Nos. 33 to 47, up to Goodge Street Nos. 33 and 35 have been demolished after war damage. No. 37 has a modern shop but the upper two storeys are of 18th-century stock brick with blank middle windows. Nos. 39, 41 and 43 are modern. No. 47, The Northumberland Arms, shows ancient brickwork in the upper storeys, but the windows, two in each storey, have architraves and segmental arched heads, and the former third storey has been converted into two storeys of less height with smaller windows. The ground storey has mid 19th-century windows and a south doorway, all divided and flanked by fluted pilasters with rosette-carved caps under a moulded cornice. The north side to Goodge Street is similar.

In 1865, the birth of a child in England was an event that carried significant social, legal, and familial implications, deeply influenced by the customs and practices of the time. The process of childbirth itself was largely a domestic affair, typically taking place at home. The majority of births were attended by a midwife rather than a physician, especially in rural areas and among the lower classes. Midwives were often women from the community who had experience in childbirth but no formal medical training. Wealthier families might employ a doctor to attend the birth, especially if complications were anticipated.

The experience of childbirth varied greatly depending on social class. In wealthier households, the mother might have access to better nutrition, cleaner living conditions, and more comfortable surroundings, which could contribute to a safer and more comfortable delivery. In contrast, poorer women often faced higher risks due to inadequate nutrition, unsanitary conditions, and limited access to medical care. Infant and maternal mortality rates were significantly higher than they are today, reflecting the lack of advanced medical knowledge and technology.

Once the baby was born, it was customary to promptly register the birth with civil authorities. The Births and Deaths Registration Act of 1836, which came into effect in 1837, mandated the civil registration of all births in England and Wales. This act required that births be registered within 42 days. Parents would go to the local registrar's office to record the details of the birth, including the date and place of birth, the name of the child, and the names of the parents. This registration process was crucial for legal purposes, as it provided official recognition of the child's identity and rights.

In addition to civil registration, many families had their children baptized shortly after birth, which served both religious and practical purposes. Baptism often took place within a few weeks of the child's birth and was recorded in the parish register. This record provided an additional layer of documentation that could be used for legal and genealogical purposes. Baptism was also seen as essential for the child's spiritual well-being, marking their entry into the Christian community and providing them with godparents who would play a significant role in their religious upbringing.

The naming of the child was an important aspect of both the civil registration and baptismal processes. Names were often chosen based on family traditions, religious significance, or in honor of relatives. The name given at baptism was considered the child's Christian name and was used in both religious and civil contexts. Some families followed the custom of naming children after saints or biblical figures, reflecting the religious influences on their lives.

The birth of a child was usually celebrated with family and community gatherings. These celebrations varied in scale depending on the family's social status and resources. For many, it was a time to reinforce social bonds and welcome the new member into the community. Gifts and well-wishes were commonly exchanged, and the event provided an opportunity for relatives and friends to offer support to the new parents.

Women's postpartum period, known as "lying-in," involved a period of rest and recovery. This could last from a few weeks to a month, during which the mother was expected to stay mostly in bed and be cared for by family members or hired help. The practices surrounding lying-in were rooted in the belief that rest was crucial for the mother's recovery and to prevent postpartum complications.

The birth of a child also had significant legal implications. The child's birthright, inheritance, and legitimacy were closely tied to the circumstances of their birth. Marital status was a crucial factor; children born to married parents had clear legal rights and inheritance claims, whereas illegitimacy could result in social stigma and legal disadvantages. The legitimacy of a child could affect their social standing, inheritance rights, and future prospects, highlighting the importance placed on marriage and family structure in Victorian England.

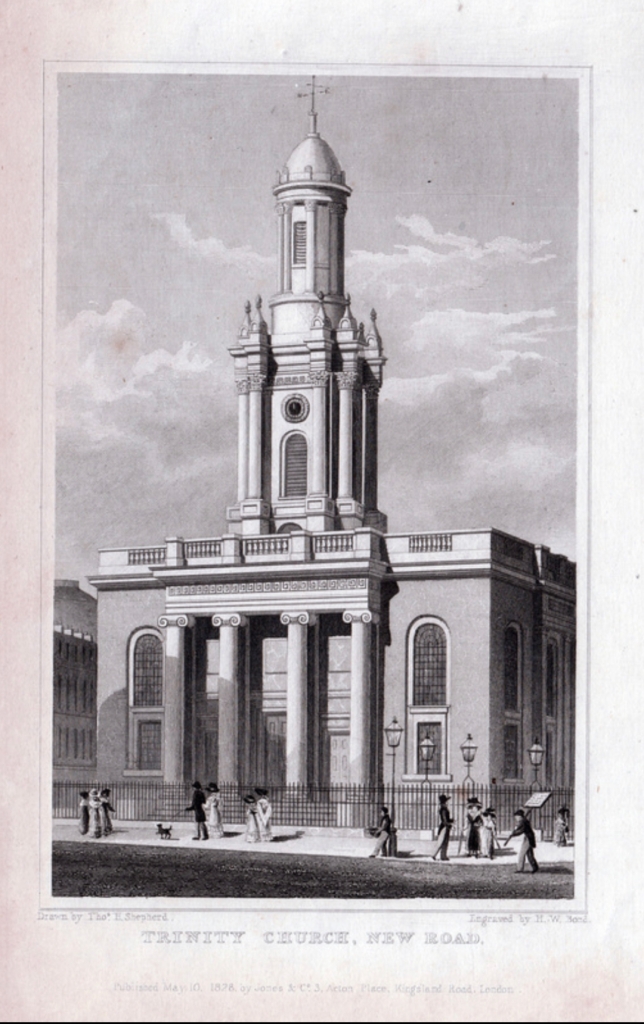

Walter James Willats, was baptised on Sunday the 26th of February, 1865, at Holy Trinity Church, Marylebone Road, Marylebone, Middlesex, England.

Richards’s occupation was given as a commercial traveller and their abode was 37 Charlotte Street.

Holy Trinity Church, in Marylebone, Westminster, London, is a Grade I listedformer Anglican church, built in 1828 and designed by John Soane. In 1818 Parliament passed an act setting aside one million pounds to celebrate the defeat of Napoleon. This is one of the so-called “Waterloo churches” that were built with the money. The building has an entrance off-set large Ionic columns. There is a lantern steeple, similar to St Pancras New Church, which is also on Euston Road to the east. George Saxby Penfold was appointed as the first Rector, having previously taken on much the same task as the first Rector of Christ Church, Marylebone. The first burial took place in the vault of the church in 1829, and the last was that of Sir Jonathan Wathen Waller in 1853. It has an external pulpit facing onto Marylebone Road, erected in memory of the Revd. William Cadman MA (1815-1891), who was rector of the parish from 1859 – 1891, renowned for his sonorous voice and preaching. By the 1930s, the use of the church had declined, and from 1936 it was used as a book warehouse by the newly founded Penguin Books. A children’s slide was used to deliver books from the street into the large crypt. In 1937 Penguin moved out to Harmondsworth, and the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge (SPCK), an Anglican missionary organisation, moved in. It was their headquarters until 2006, when they relocated to Tufton Street, Westminster (they have since moved again to Pimlico). In 2018 the church became the location of the world’s first wedding department store, The Wedding Gallery, based on the ground floor and basement level. The first floor is used as an events space operated by One Events and known as “One Marylebone”. The former church stands on a traffic island by itself, bounded by Marylebone Road at the front, and Albany Street and Osnaburgh Street on either side; the street at the rear north side is Osnaburgh Terrace.

In 1865, baptisms and christenings in England were deeply rooted in religious tradition, particularly within the Church of England, which was the established church at the time. Baptism was considered a sacrament essential for salvation and an entry into the Christian faith, and it was almost universally practiced for infants, reflecting the widespread belief in original sin and the necessity of baptism for the remission of this sin.

The process of baptism typically took place in a church and involved a series of ritualistic steps. The infant would be brought to the church by their parents and godparents, who were selected to help guide the child's religious upbringing. The ceremony was often incorporated into the regular Sunday service or held as a separate event. The officiating priest would use a font, a basin usually situated near the entrance of the church, filled with holy water. During the ceremony, the priest would ask the godparents to renounce Satan and all sinful desires on behalf of the child and to affirm their belief in the core tenets of Christianity as outlined in the Apostles' Creed.

The actual act of baptism involved the priest pouring water over the infant's head, reciting the Trinitarian formula: "I baptize you in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Ghost." This ritual signified the child's cleansing from original sin and their formal admission into the Christian community. In the Church of England, the ceremony was often referred to as a christening, emphasizing the naming aspect of the ritual. The name given to the child during this ceremony was considered their Christian name and was used in both religious and civil contexts.

Godparents played a crucial role in the baptism ceremony. Traditionally, there would be two godparents of the same sex as the child and one of the opposite sex. The godparents made solemn promises to ensure the child would be brought up in the Christian faith, attending church and learning the catechism. These promises were taken seriously, as godparents were expected to act as spiritual mentors throughout the child's life.

The importance of baptism was reflected in civil registration laws of the time. The Births and Deaths Registration Act of 1836, which came into effect in 1837, mandated the civil registration of births, but many families still relied heavily on church baptismal records as a primary means of documenting a child's birth and name. These records were meticulously kept by parish churches and were crucial for legal and genealogical purposes.

Baptism also had social and cultural significance beyond its religious implications. It was a major event in the life of a family, often accompanied by gatherings and celebrations. The ceremony provided an opportunity for the community to welcome the new member and for families to reinforce social bonds. In rural areas, where the local church often served as the center of community life, baptisms were significant communal events.

While the Church of England was predominant, other Christian denominations, such as Roman Catholics, Methodists, and Baptists, also practiced baptism but with variations in theology and practice. Roman Catholics, like Anglicans, baptized infants and followed a similar liturgical form. Methodists also practiced infant baptism but placed a strong emphasis on the personal faith journey that would follow as the child grew. Baptists, on the other hand, rejected infant baptism in favor of believer's baptism, arguing that baptism should be reserved for those who could consciously profess their faith, typically resulting in the baptism of older children and adults.

Walter’s parents Richard Henry Willats and Eliza Willats nee Cameron finally decided to marry. Their banns were read, at St John the Evangelist, Smith Square, London, England, on the Sunday the 9th and Sunday the 16th of April, by W.S. Bruce and again on Sunday the 23rd of April, 1865, by J. Graham.

St John’s Smith Square is a redundant church in the centre of Smith Square, Westminster, London. In 1710, the long period of Whig domination of British politics ended as the Tories swept to power under the rallying cry of “The Church in Danger”. Under the Tories’ plan to strengthen the position of the Anglican Church and in the face of widespread damage to church buildings after a storm in November 1710, Parliament concluded that 50 new churches would be necessary in the cities of London and Westminster. An Act of Parliament in 1711 levied a tax on coal imports into the Port of London to fund the scheme and appointed a commission to oversee the project. Archer was appointed to this commission alongside, amongst others, Hawksmoor, Vanburgh and Wren. The site for St. John’s was acquired from Henry Smith (who was also Treasurer to the Commissioners) in June 1713 for £700 and building commenced immediately. However, work proceeded slowly and the church was finally completed and consecrated in 1728. In total, the building had cost £40,875. The church was built by Edward Strong the Younger a friend of Christopher Wren the Younger.

Mrs. Eliza Willats nee Cameron, and Mr. Richard Henry Willats married on Thursday the 4th of May, 1865, at, St Margarets, Westminster, London, England. Richard was a Bachelor. Eliza was listed as a widower, which is rather strange as her first husband George John Willats (Charlotte’s uncle/Richard Henry Willats brother) was one of their witnesses and didn’t die until later that year. Their other witness was, Edith’s Aunt/Eliza’s sister, Mary Cameron. Eliza and Richard, were residing at 10 North Street. Richard was working as a, Commercial Traveller. Eliza’s Father, Allen Cameron was working as a Tailor and Richard’s Father, George John Willats, was working as a Wood Craver. I have no idea as to how Richard and Eliza were able to marry, as it was strictly forbidden to marry a brothers wife even a deceased brother. Family story’s state that, a sympathetic member of the clergy came to their rescue and had the first marriage annulled. I guess we will never know for sure but it seems that maybe something fishy was going on as George John married Sarah Elizabeth Southall Jukes, in Victoria, Australia, in 1856 (11 years before Richard and Eliza wed.

St. Margaret’s, known as ‘the Church on Parliament Square’, is a 12th-century church next to Westminster Abbey. It’s also sometimes called ‘the parish church of the House of Commons’. The Church of St Margaret, Westminster Abbey, is in the grounds of Westminster Abbey on Parliament Square, London, England. It is dedicated to Margaret of Antioch, and forms part of a single World Heritage Site with the Palace of Westminster and Westminster Abbey. The church was founded in the twelfth century by Benedictine monks, so that local people who lived in the area around the Abbey could worship separately at their own simpler parish church, and historically it was within the hundred of Ossulstonein the county of Middlesex. In 1914, in a preface to Memorials of St. Margaret’s Church, Westminster, a former Rector of St Margaret’s, Hensley Henson, reported a mediaeval tradition that the church was as old as Westminster Abbey, owing its origins to the same royal saint, and that “The two churches, conventual and parochial, have stood side by side for more than eight centuries – not, of course, the existing fabrics, but older churches of which the existing fabrics are successors on the same site. In 1863, during preliminary explorations preparing for this restoration, Scott found several doors overlaid with what was believed to be human skin. After doctors had examined this skin, Victorian historians theorized that the skin might have been that of William the Sacrist, who organized a gang that, in 1303, robbed the King of the equivalent of, in modern currency, $100 million. It was a complex scheme, involving several gang members disguised as monks planting bushes on the palace. After the stealthy burglary 6 months later, the loot was concealed in these bushes. The historians believed that William the Sacrist was flayed alive as punishment and his skin was used to make these royal doors, perhaps situated initially at nearby Westminster Palace. Subsequent study revealed the skins were bovine in origin, not human.

In 1865, the laws of marriage in England were governed by a combination of civil and ecclesiastical regulations, which were largely influenced by earlier legislative reforms and established church doctrines. The legal framework for marriage was shaped by acts such as the Marriage Act of 1836 and the Marriage and Registration Act of 1856, which introduced significant changes to the way marriages were conducted and recorded.

The Marriage Act of 1836 was pivotal because it allowed non-Anglican Christians and other dissenters to marry in their own registered places of worship. This act also made civil marriages possible, conducted in registry offices, for those who did not wish to marry in a religious ceremony. Before this act, marriages had to occur in an Anglican church to be legally recognized. Under this act, specific formalities were required for a marriage to be valid. These included the posting of banns, a public announcement of the intended marriage on three consecutive Sundays in the parishes of both parties. Alternatively, a couple could obtain a common license, which expedited the process but involved a fee. For those needing even more urgency, a special license from the Archbishop of Canterbury allowed marriage at any time and place.

The Marriage and Registration Act of 1856 refined these procedures by implementing stricter regulations to prevent clandestine and fraudulent marriages. This act mandated a more detailed system of registration, requiring all marriages to be recorded with local civil authorities, ensuring comprehensive documentation at both local and national levels.

The legal age for marriage without parental consent was set at 21. However, boys as young as 14 and girls as young as 12 could marry with parental consent, although such young marriages were rare and generally discouraged. Parental consent was crucial for those under 21; without it, the marriage could be annulled.

Marriage laws also included restrictions on consanguinity and affinity, prohibiting marriages between close blood relatives and certain in-laws. These prohibitions were rooted in biblical teachings and included bans on marrying direct relatives such as siblings, parents, and children, as well as certain in-laws. Specifically, the law did not permit a man to marry his deceased brother's wife, a regulation based on Levitical laws. This prohibition against marrying a deceased brother's wife was firmly upheld, reflecting societal and religious norms that governed familial relationships and marriage suitability.

Divorce laws in 1865 were complex and largely inaccessible to most people. The Matrimonial Causes Act of 1857 had established a civil divorce court, allowing for divorces outside of private Acts of Parliament, but the grounds for divorce were biased against women. A man could divorce his wife on the grounds of her adultery alone, whereas a woman had to prove her husband's adultery in addition to other faults like cruelty, desertion, or bigamy. The costs associated with divorce were high, making it primarily an option for the wealthy.

Married women had very limited legal rights due to the doctrine of coverture, which subsumed a woman's legal rights and obligations under those of her husband upon marriage. Married women could not own property in their own name, enter into contracts independently, or sue or be sued separately from their husbands. This situation began to change with the Married Women's Property Act of 1870, which allowed married women to keep earnings and inherit property independently, but in 1865, a woman's legal identity was still heavily restricted by her marital status.

In essence, the marriage laws in England in 1865 were defined by a blend of religious and civil requirements, strict procedures to ensure the validity of marriages, and significant limitations on the rights of married women. Restrictions on marrying certain relatives, including a deceased sibling’s spouse, were firmly in place, reflecting the period’s moral and religious standards. Although legal reforms were underway, much of the legal framework remained rooted in traditional views of marriage and family, with gradual changes beginning to reflect evolving social attitudes and civil liberties.

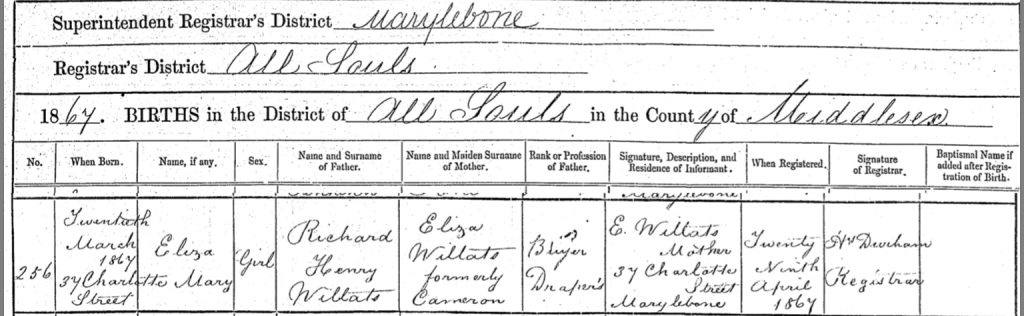

A few years later, Walter’s sister, Eliza Mary Willats was born on Wednesday the 20th of March, 1867, at Number 37 Charlotte Street, All Paul’s, Marylebone, Middlesex, England. Eliza’s Father Richard Henry Willats, was working as a Buyer of Diamonds, at the time of her birth. Eliza mother Eliza Willats nee Cameron, registered Eliza’s birth on Monday the 29th April 1867.

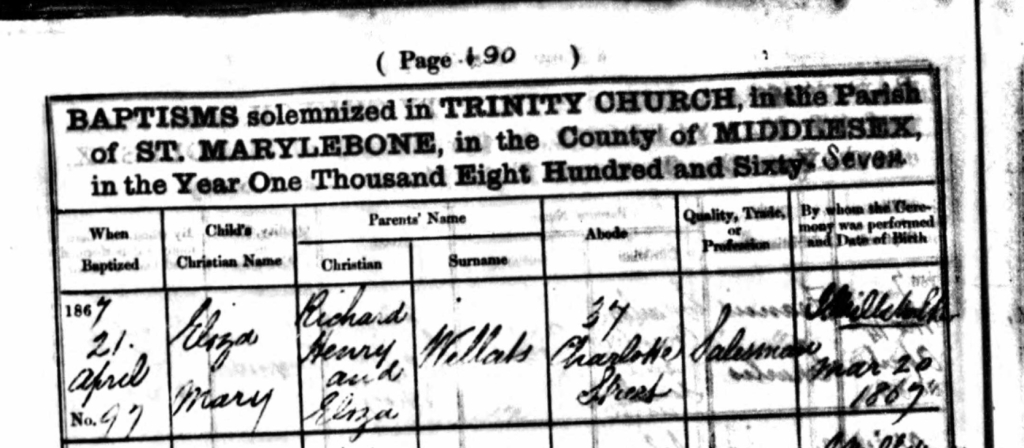

Richard and Eliza baptised Eliza Mary, on the 21st of April 1867, at Holy Trinity Church, Marylebone Road, Marylebone, Middlesex, England. Richards occupation was given as Saleman and their abode as, 37 Charlotte Place.

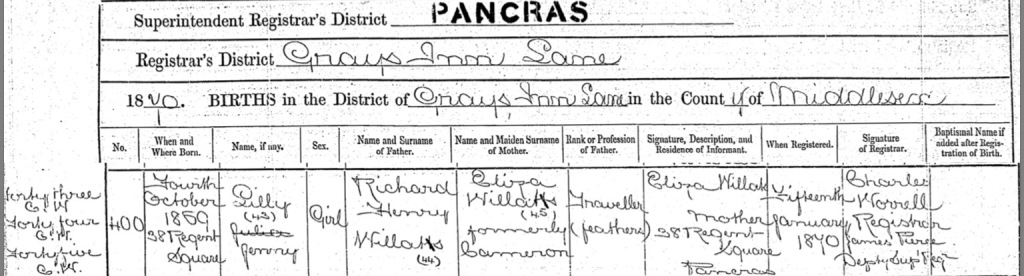

Walter’s sister, Lilly Jenny Willats was born on Monday the 4th of October, 1869, at, Number 38, Regent Square, Greys Inn Lane, Pancras, Middlesex, England. Lily’s mother Eliza Willats nee Cameron, registered her birth on Saturday the 15th of January 1870. She gave Lily’s Father Richard Henry Willats, whose occupation was listed as a Traveller ( Feathers) and their abode as Number 38, Regent Square, Pancras.

Regent Square is a public square and street in the London Borough of Camden in London, England. It is located near Kings Cross and Bloomsbury.

Regent Square was laid out around a large garden in the historic Harrison Estate and first occupied in 1829, forming a garden square similar to more famous ones to the west in Bloomsbury. The southern side of the square is composed of its original buildings, and is Grade II listed in its entirety. Also listed is the phone box within the square gardens themselves.

Regent Square was home to the National Scotch Church (the ‘Caledonian Church’) – the first purpose-built Scottish Gaelic Presbyterian church in London – which was built between 1824 and 1827. In 1843, it became an English Presbyterian church. The square was also home to St Peter’s Church, a Church of England church. Both churches were struck by bombs in World War II and subsequently demolished.

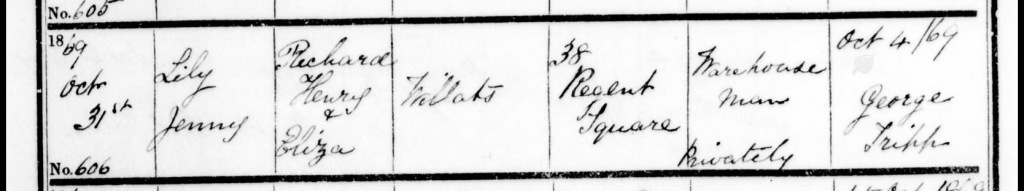

Lily Jenny Willats, was baptised on Sunday the 31st of October 1869, at Saint Peter Church, Saint Pancras, London, England. It was a private baptism. Their father Richard’s occupation was given as Warehouse Man and their abode as 38 Regent Square.

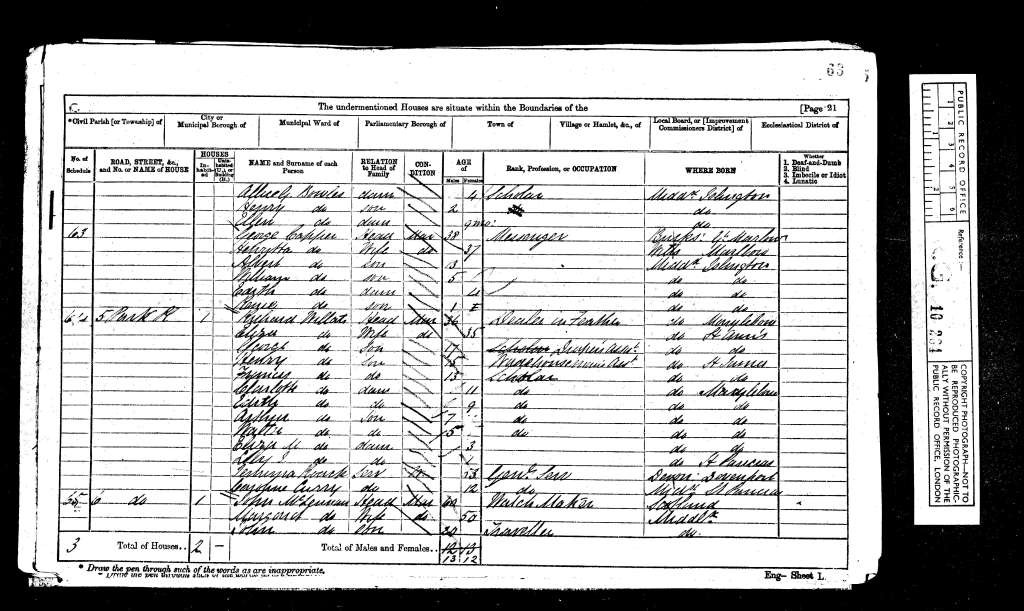

Walter, his parents Richard, and Eliza, and his siblings, Francis, Henry, Eliza, Lillian, Edith, George and Charlotte, were residing at, Number 5, Park Road, Islington, Middlesex, England, on Sunday 2nd April 1871. Richard was working as a Dealer in feathers.

The family had two General Servants, residing with them, Jemima Roac and Caroline Curry.

5 Park Place, London is a 3 bedroom freehold terraced house – it is ranked as the 3rd most expensive property in N1 3JU, with a valuation of £1,432,000. Since it last sold in July 2016 for £1,450,000, its value has decreased by £18,000. It is now a sleek contemporary townhouse within a private gated mews, arranged over three floors with an allocated parking space.

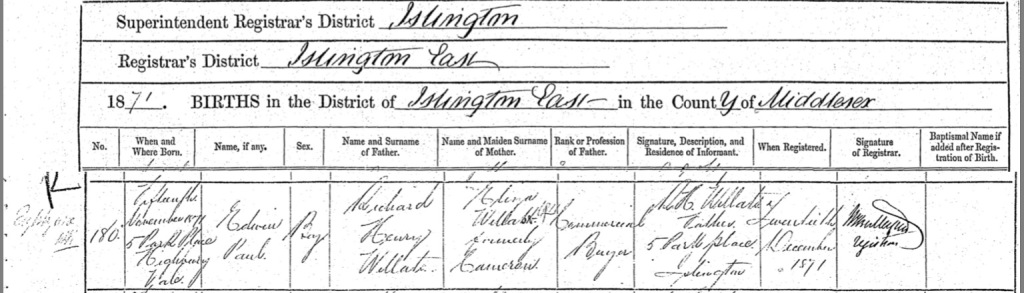

Walter’s brother, Edwin Paul Willats, was born on Wednesday the 8th of November, 1871, at Number 5, Park Place, Highbury, Islington, Middlesex, England. Edwin father Richard Henry Willats, registered Edwins birth on Wednesday December 20th 1871. He gave his occupation as a Commercial Buyer and their abode as, Number 5, Park Place, Islington.

Richard and Eliza, baptised their son, Edwin Paul Willats, on Friday the 8th of December 1871, at St. Mary’s Church, Islington, Middlesex, England. Richards occupation was given as a Warehouse Man and their abode as 5 Park Place.

The Church of St Mary the Virgin is the historic parish church of Islington, in the Church of England Diocese of London. The present parish is a compact area centered on Upper Street between Angel and Highbury Corner, bounded to the west by Liverpool Road, and to the east by Essex Road/Canonbury Road. The church is a Grade II listed building.

The churchyard was enlarged in 1793. With the rapid growth of Islington, it became full and closed for burials in 1853. It was laid out as a public garden of one and a half acres in 1885.

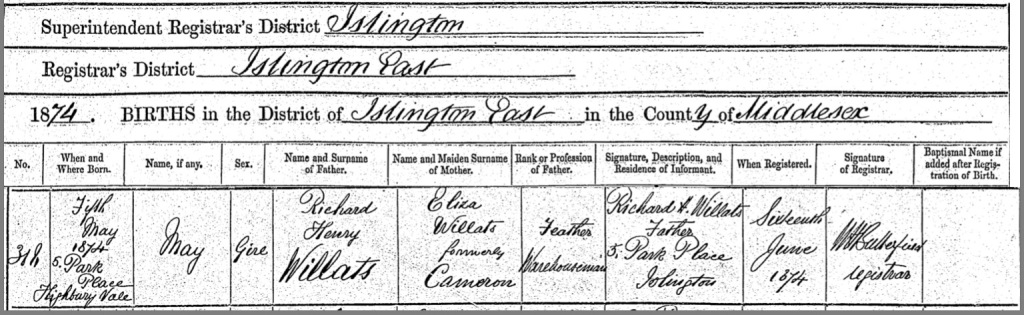

Walter’s sister, May Claretta Willats, was born on Tuesday the 5th of May, 1874, at 5 Park Place, Highbury, East Islington, England.

May’s father Richard Henry Willats registered May’s birth on Tuesday the 16th of June 1874. He gave his occupation as a Feather Warehouseman and their abode as 5 Park Place, Islington.

May was baptized on, Sunday the 9th of August, 1874, at Christ Church, Highbury, Islington, Middlesex, England. Richard gave his occupation as a Manufacturer and their abode as, Highbury.

Christ Church, Highbury is an Anglican church in Islington, north London, next to Highbury Fields.

The site was given by John Dawes, a local benefactor and landlord, and the church was built by Thomas Allom in a cruciform shape with a short chancel, transepts, and nave from 1847 to 1848. Bridget Cherry and Nikolaus Pevsner write that Christ Church Highbury ‘is a successful and original use of Gothic for a building on a cruciform plan with broad octagonal crossing. The cross-plan with broad nave and crossing were popular for churches in the low church tradition where an effective auditorium for the spoken word was preferred to a plan designed for an elaborate liturgy.’

Since then, several changes have been made to the church, including the addition of a balcony in 1872, and new rooms for children’s work and fellowship in 1980.

The church was opened in 1848 by Reverend Matthew Anderson Collisson, son of Irishman Daniel Marcus Collisson and his wife Catherine.

A special service booklet was published to celebrate the occasion: “On the Consecration of the New Church at Highbury, Dedicated to the Saviour as ‘Christ’s Church'”, Reverend M A Collisson.

Walter’s brother, Percy Sidney Willats was born on Wednesday the 1st of September 1875, at Number 9, Park Place, Highbury, Islington, Middlesex, England. His father Richard Henry Willats, registered Percy’s birth on Saturday the 9th October, 1875, in Islington. He gave his occupation as a, Fancy Warehouseman and their abode as, 9, Park Place, Islington.

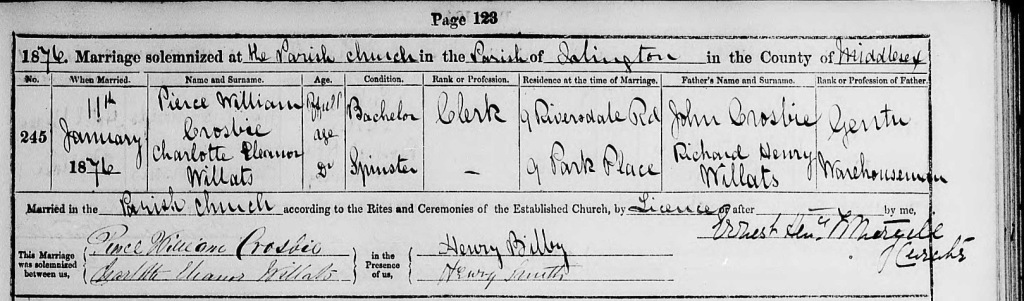

Walter’s Sister, Charlotte secretly married my licence a young Bachelor named Peirce William Crosbie, on the 11th of January 1876, at St Mary Church, Islington, Middlesex, England. They both stated they were of full age, even though Charlotte was only 16. Their witnesses were, Henry Billey and Henry Smith. Charlotte gave her abode as, 9 Park Place and Pierce gave his As 9 Riverdale Road. Pierces occupation was given as a Clark. They gave their fathers names and occupations as, Richard Henry Willats, a Warehouseman and John Crosbie a Gentu.

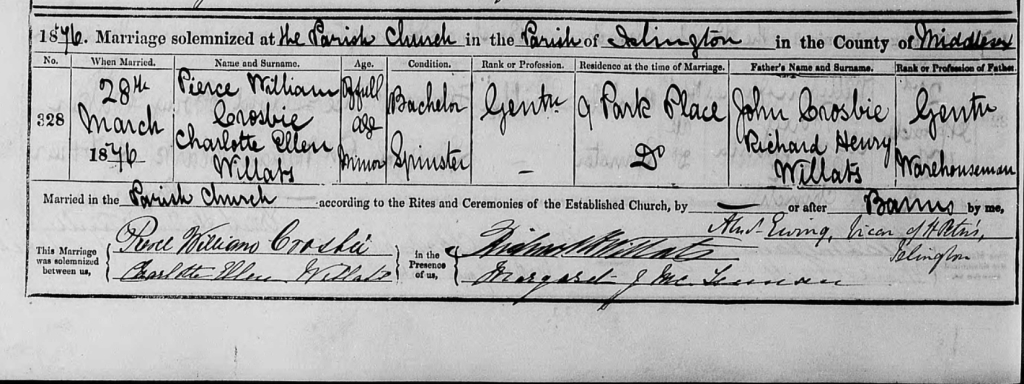

Walter’s sister, Charlotte Ellen Willats married bachelor, Pierce William Crosbie, for a second time, this time not in private. They married on Tuesday the 28th of March, 1876, in St Mary’s Church, Islington, Middlesex, England. Charlotte was a minor and Pierce was of full age. Pierces occupation was given as a Gentu. They gave their residence as 9 Park Place and gave their fathers names and occupations as, Richard Henry Willats, a Warehouseman and John Crosbie a Gentu. Their witnesses were Richard Willats and Charlottes future sister in-law Margaret Jane McLennon.

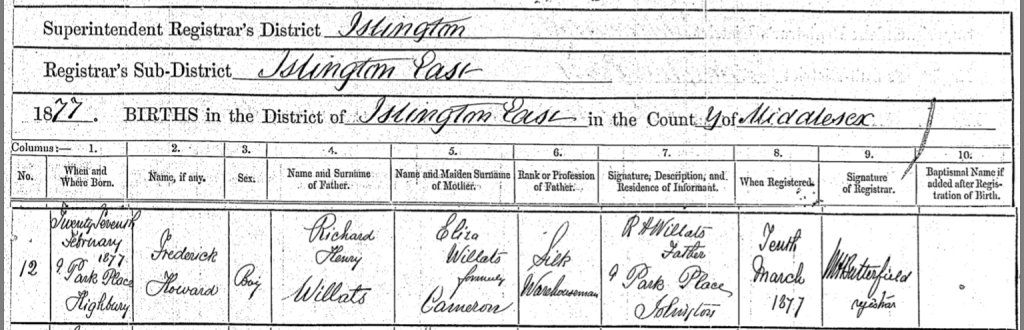

Walter’s brother, Frederick Howard Willats was born on on Tuesday the 27th of February 1877 at, Number 9, Park Place, Highbury, Islington, Middlesex, England. His father Richard Henry Willats registered Frederick’s birth on Saturday the 10th March 1877. Richard gave his occupation as a Silk Warehouseman, and their abode as, 9 Park Place, Islington.

Walter’s brother 24-year-old, bachelor, and publican, Henry Richard Willats married 23 year old, spinster, Amelia Etheredge, daughter of John Etheredge, on Tuesday the 30th of March, 1880 at All Saints Church, West Ham, Essex, England. Henry gave his residence as West Ham and Amelia as, Saint Paul’s, Shadwell. They gave their fathers names and occupations as, Richard Henry Willats, a Licensed Victualler and John Etheredge, an Engineer. Their witnesses were Charles Henry Etheredge and Alice Catherine Etheredge.

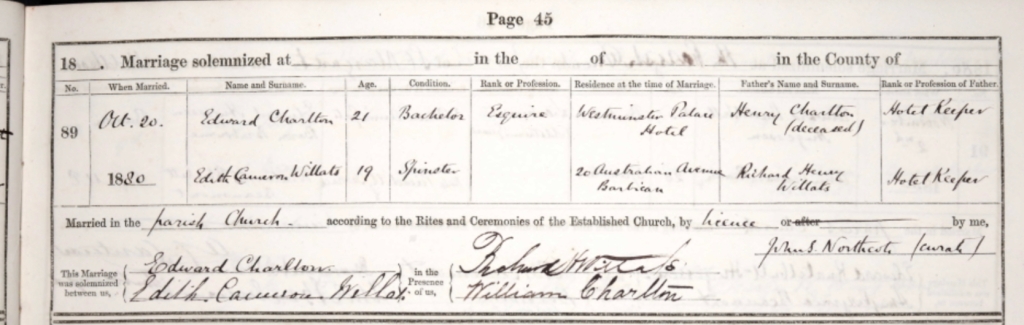

Walter’s sister, Edith Cameron Willats married 21-year-old Bachelor, Edward Charlton, an Esquire, on Wednesday the 20th of October, 1880, at St Margaret Church, George Hanover Square, Westminster, London, England. They gave their fathers names and occupations as, Richard Henry Willats, a Hotel Keeper and Henry Charlton, a Hotel Keeper. Edith gave her residents as, 20 Australian Avenue, Barbican, Silk Street, St Giles, Westminster, London, EnglandAnd Edward gave his as Westminster Palace Hotel. Their witnesses were, Richard Willats and William Charlton.

The 1881 census was taken on Sunday the 3rd April 1881. The census shows, Walter, his parents Richard, Eliza, and his siblings, Frank, Arthur, Eliza, Lillian, Edwin, May, and Sidney, were residing at number 61, Ambler Road, Islington, London & Middlesex, England. They had a guest named Henry Anstey staying with them. Richard was a Publican, out of business. Frank was a General agent, Arthur a Clerk solicitors, Walter a Clerk stock exchange and Eliza, Lillian, Edwin, May and Sidney were scholars. Henry Anstey was an Enumerator (no occ).

Walter’s brother 23-year-old, bachelor, Francis Montague Allen Willats, married 25-year-old, spinster, Margaret Jane McLennon, at St John’s Church, Hornsey, Middlesex, England, on Wednesday the 6th of July, 1881. Francis was working as an agent at the time of his marriage. They gave their fathers names and occupations as Richard Henry Willats, an Agent and John McLennon, a Chronometer Maker. Francis gave his abode as, 145 Blackstock Road and Margaret gave hers as, 84, Finsbury Park Road. Their witnesses were John McLennon and Jessie McLennon.

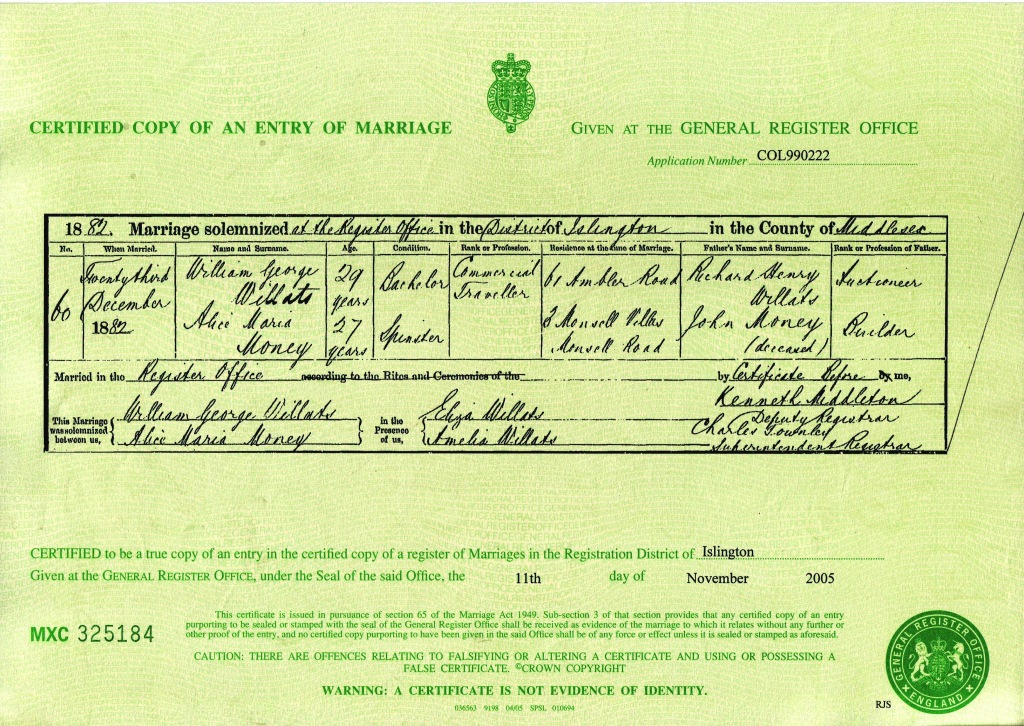

Walter’s brother 29-year-old, bachelor William George Willats, a Commercial Traveller, married 27-year-old spinster, Alice Maria Money, at The Register Office, Islington, Middlesex, England, on Saturday the 23rd of December, 1882. William gave his occupation as a Commercial Traveller. They gave their fathers names and occupations as, Richard Henry Willats, an Auctioneer, and John Money (deceased) a Builder. Their witnesses were, Eliza Willats and Amelia Willats.

Across the pond in Buffalo United States of America, Walter’s brother, Arthur Charles Willats married Josephine Mary Conley in 1886 when he was 23 years old. Unfortunately at present I haven’t come across any documentation for their marriage only census records and births of their children. Being in the United Kingdom, research in America isn’t the easiest especially ordering certificates etc.

Walter James, was mentioned in an article called, “THE GREAT BOND ROBBERY.” which was printed in “The Morning Post” newspaper, on Wednesday the 29th of August 1888.

It reads,

THE GREAT BOND ROBBERY.

At the Guildhall Police-court yesterday, before Mr. Alderman Phillips, Mortimer R. Casey was brought up on remand, charged with having, on the 28th of October last, stolen, with personai violence, a bag containing Uruguay, Ohio, and Mississippi Bonds, valued at £10,800, also with stealing and receiving two Spanish bonds, valued at £1,904 12:.

Mr. H. G. Abrahams, solicitor, appeared on behalf of Messrs. Alexander Wilson and Sons, the prosecutors.

Alderman Phillips, on taking his seat, said that as the case seemed to be one which would undoubtedly go for trial, he hoped, in the interests of public business, the evidence would be put before the court as briefly as possible.

Detective-sergeant Taylor produced a letter signed by the prisoner, and addressed to Mr. George Ripley, in which the prisoner said :—"The 120 Ohio-Mississippi Shares you hold on my account are the property of Messrs. Alexander Wilson and Sons, of this city. "

Mr. Leslie Wilson, a member of the firm of Alexander Wilson and Sons, stockbrokers, 69, Cornhill, was next examined. He said that he received £7,000 worth of Uruguay 5 per Cent. Bonds on the 28th of October, 1887. On the 15th of September, 1887, witness received 190 Ohio and Mississippi Shares in his stock-book. The nominal value of these bonds was £3,500. He had not checked the bonds seized at the prisoner's lodgings with those in his book. He handed those bonds to his clerk James Watson, on the 28th of October in order that he might get the money for them.

James Dunber Lyell Watson said — I am a clerk in the employ of Messrs. Alexander Wilson and Sons. On the 28th ot October, 1887, Mr. Leslie Wilson instructed me to deliver 190 Obio Shares and £7,000 worth of Uruguay Bonds to various members of the Stock Exchange. I took them to Mr. George Cawston's. I was carrying the bonds in a bag which had the name of the firm on it. I went into Mr. Cawston's office, and as I was walking down the steps there was a man in front. As I turned round the angle of the staircase he raised his arms and went for my throat, having in one hand something that glittered like a knife. He cut me under the chin and took the bag me.

Do you mean he made a blow at you?—He went at me with both arms up. I slipped over, or fell down the staircase, and when I got up the thief had got clear away,

Was the bag gone? — Yes.

Did you see him snatch the bag?—No, I can't tell how it went.

Were you on the ground?-Not when it was taken.

Do you recognise the prisoner as the man? —Only as far as his stature goes; I don't recognise his features.

Mr. Phineas Hands, of 16, Strand, money changer and banker, was next examined. He stated that about the 28th of October, 1887, certain Uruguay bonds were presented to him for exchange. There was a large number of them.

He informed the person who presented them that he could not give the money, but would inquire if they were in order. Two coupons were left in witness's office by the person who presented the bonds, and witness requested that person to call again. He handed the two coupons to the police next day. The man did not ask him to buy the bonds.

Mr. Frederick Hargreaves, of 377, Strand, money changer, was then called. He said that the prisoner, whom he recognised, brought in on the 23rd of October several coupons of the Uruguay Loan and asked witnesses to cash them. He thought there were from seven to 10. Witness said that as the prisoner was a stranger he could not cash them at once. Besides, they were not payable for three months. Prisoner said he was in the habit of cashing coupons before they were due, and witness said he had better go to Reimart's, in Coventry-street. Witness gave notice to the police of what had happened a day or two afterwards, as soon as he knew of the robbery.

Mr. Thomas George Cartmell, cashier at Messrs. Reimart's, bankers and money changers, 14, Coventry-street, was next exaxined. He said he did not recogmise the prisoner. On the afternoon of the robbery a man presented some Uruguay coupons for the purpose of having them discounted. There were several coupons, some being for £100 bonds and others for £500 bonds. Witness said he could not cash them, as they were not due. The police communicated with witness next day.

This being the case for the prosecution, the charge against the prisoner was read over, and having been duly cautioned and asked whether he had anything to say, the prisoner said he should object to some of the evidence, but should not do so now.

Alderman Phillips-Do you wish to call any witnesses?— No sir.

Not as to character, but as to the charge against you?— No Sir.

Alderman Phillips - Then all that is left for me to do in this case is to commit you for trial.

Mr. Abrahams then preferred against the prisoner the further charge of having stolen and received two Spanish 4 per Cent. Bonds of £952 6s. each, belonging to Messrs.

Schaap and Hilburn.

Sergeant Taylor said that on the 20th of August, when he arrested the prisoner on the other charge, on searching his lodgings, 29. Westmoreland-road, Bayswater, he there found the two Spanish bonds of the 4 per Cent. Loan, produced, each of the nominal value of £952 6s. At the same time the Uruguay Bonds were aiso found. Prisoner said,

"I found them at a certain place, and all I wish is to tell the truth about them." He made no further statement.

Mr. Magnus Levi Schaap, of the firm of Schaap and Hilburn, 2, Drapers'-gardens, stated that he purchased two 4 per Cent. Spanish Bonds in Apil last, and they were to be delivered on the 12th of that month-the account day. The cheque for £1,290 7s. 4d. (produced) was given for the bonds, and witness sold them the same day.

Witness caused a search to be made for the bonds in his office on the 12th of April, and they could not be found.

Mr. Arthur Fuller, a clerk in the employ of Messrs. Wilson, Montague, and Co., stockbrokers, stated that on the 12th of April last he went to the oftice of Messrs.

Schaap and Hilburn with two 4 per Cent. Spanish Bonds of $952 6s. each, which he duly delivered to Messrs. Schaap and Hiiburn's clerk. The name of that clerk was Willats.

He saw the clerk open the bonds, call them out to another clerk, and put them in a basket behind him.

Mr. Walter James Willats, clerk to Messrs. Schaap and Hilburn, corroborated the evidence of the last witness.

He added that he could not recognise the prisoner Wilson.

Montague's ticket was attached to the bonds when he received them, and he put the name of Mr. Lambrinudi to them when he put them in the basket. They were to be delivered to Mr. Lambrinudi. When the bonds were missed witness made inquiry about them.

Mr. Alfred Capern, a clerk in the employment of Messrs. Birch and Co., stockbrokers, stated that on the 12th of April he was in the employment of Messrs. Schaap and Hilburn. He was present when the witness Fuller received the bonds deposed to, and marked in the book the particulars of the bonds. The basket in which the bonds were placed was taken out of the room to the general office by Mr. Willats, he believed. He could not recognise the prisoner as having been in Messrs. Schaap and Hilburn's office.

Mr. Abrahams said he could prove that other bonds had to be purchased and handed over to Mr. Lambrinudi in lieu of those that were lost.

Mr. Alderman Phillips said he did not think it necessary to produce such evidence.

This was the case against the prisoner on the second charge, and as he had nothing to say, but reserved his defence, he was committed for trial.

The prisoner said he desired the benefit of counsel, but was poor and had no means.

Mr. Alderman Phillips said that the prisoner must make his application to the court at which he would be tried.

Mr. Abrahams said he would see that the matter was mentioned in the proper quarter.

A further application by the prisoner for the money found in his possession was at once acquiesced in, the prosecution offering no objection.

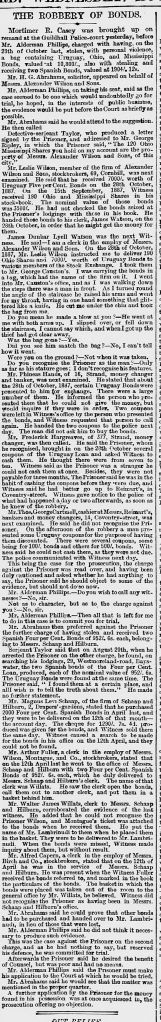

Walter was mentioned in an article called “THE ROBBERY OF BONDS.” which was printed on page 2 of “The London Evening Standard”, newspaper on Wednesday the 29th of August 1888.

It reads as follows,

THE ROBBERY OF BONDS.

Mortimer R. Casey was brought up on remand at the Guildhall Police-court yesterday, before Mr. Alderman Phillips, charged with having, on the 28th of October last, stolen, with personal violence, a bag containing Uruguay, Ohio, and Mississippi Bonds, valued at 10,800/., also with stealing and receiving two Spanish Bonds, valued at 1904/ 12s.

Mr. H. G. Abrahams, solicitor, appeared on behalf of Messrs. Alexander Wilson and Sons.

Mr. Alderman Phillips, on taking his seat, said as the case seemed to be one which would undoubtedly go for trial, he hoped, in the interests of public business, the evidence would be put before the Court as briefly as possible.

Mr. Abrahams said he would attend to the suggestion.

He then called Detective-serjeant Taylor, who produced a letter signed my the prisoner, and addressed to Mr. George Ripley, in which the prisoner said, “The 120 Ohio Mississippi Shares you hold on my account are the property of Messrs. Alexander Wilson and Sons, of this city.

Mr. Leslie Wilson, member of the firm of Alexander Wilson and sons, stockbrokers, 69, Cornhill, was next examined. He said that he received 7000/. worth of Uruguay Five per cent. Bonds on the 28th October, 1887. On the 15th September, 1887, Witness

received 190 Ohid ans Mississippi Shares in his stock-book. The normal value of these bonds was 3500/. He had not checked the bonds seized at the prisoner lodgings with those I. His book. He handed those bonds to his clark, James Watson, on the 28th October, in order that he might get the money for them.

James Dunbar Lyell Watson was the next Witness. He said-I am a clerk in the employ of Messrs. Alexander Wilson and Sons. On the 28th of October, 1887, Mr. Leslie Wilson instructed me to deliver 190 Ohio Shares and 7000/ worth of Uruguay Bonds to various members of the Stock Exchauge. I took them to Mr. George Causton’s. I was carrying the bonds in a bag, which had the name of the firm on it. I went into Mr. Causton’s office, and as I was walking down the steps there was a man in front.

As I turned round the angle of the staircase he raised his arms and went for my throat, having in one hand something that glittered like a knife. He cut me under the chin and took the bag from me.

Do you mean he made a blow at you ?—He went at me with both arms up. I slipped over, or fall down the staircase. I can not say which, and when I got up the thief had got clear away.

Was the bag gone?-Yes.

Did you see him snatch the bag? —No, I can’t tell how it went.

Were you on the ground?-Not when it was taken.

Do you recognise the Prisoner as the man?-Only as far as his stature goes; I don’t recognise his features.

Mr. Phineas Hands, of 16, Strand, money changer and banker was next examined. He stated that about the28th of October, 1887, certain Uruguay Bonds were presented to him to exchange. There were a large number of them. He informed the person who presented them that he could not give the money, but would inquire if they were in order. Two coupons were left in Witness’s office by the person who presented them, and the witness requested that the person to call again. He handed the two coupons to the police next day. The man did not ask him to buy the bonds.

Mr. Frederick Hargreaves, of 377, Strand, money changer, was then called. He said the Prisoner, whom he recognised, brought in on the 28th October several coupons of the Uruguay Loan and asked Witness to cash them. He thought there were from seven to ten.

Witness said as the Prisoner was a stranger he could not cash them at once. Besides, they were not payable for three months. The Prisoner said he was in the habit of cashing coupon before they were due, and Witness said he better go up to Reimart’s in Coventry-street. Witness gave notice to the police of what had happened a day or two afterwards, as soon as he knew of the robbery.

Mr. Thos. George Cartmell, cashier at Messrs, Reimart’s, bankers and money changers, 14, Coventry-street, was next examined. He said de did not recognise the prisoner. On the afternoon of the robbery a man presented some Uruguay coupons for the purpose of having them discounted. There were several coupons, some being for 100/. bonds and others for 500/. bonds.

Witness said he could not cash them, as they were not due.

The police communicated with Witness next day.

This being the case for the prosecution, the charge against the Prisoner was read over, and having been duly cautioned and asked whether he had anything to say, the prisoner said he should object to some of the evidence, but should not do so now.

Mr. Alderman Phillips.-Do you wish to call any witnesses? —No, sir.

Not as to character, but as to the charge against you?—No, sir.

Mr. Alderman Phillins.Then all that is left for me to do in this case is to commit you to trial.

Mr. Abrahams then preferred against the Prisoner the further charge of having stolen and received two Spanish Four per Cent. Bonds of 9521. 6s. each, belonging to Messrs. Schaap and Hilburn.

Serjeant Taylor said that on August 20th, when he arrested the Prisoner on the other charge, he found, on searching his lodgings, 2, Westmoreland-road, Bays-water, the two Spanish bonds of the Four per Cent. Loan, produced, each of the normal value of 952/. 6s. The Uruguay Bonds were found at the same time. The prisoner said, “I found them at a certain place, and all I wish is to tell the truth about them.”

He made no further statement.

Mr. Magnus Levi Schaap, of the firm of Schaap and Hilburn, 2 Drapers’- gardens, stated that he purchased 2000 Four per Cent. Spanish Bonds in April last, and they were to be delivered on the 12th of that month- the accounts day. The cheque for 1290/. 7s. 4d. produced was given for the bonds in his office on the 12th April, and they could not be found.

Mr. Arthur Fuller, a clerk in the employ of Messrs. Wilson, Montague, and Co., stockbrokers, stated that on the 12th April last he went to the office of Messrs. Schaap and Hilburn with two Four per Cent. Spanish Bonds of 9521. 63. each, which he duly delivered to Messrs. Schaap and Hilburn’s clerk.

The name of that clerk was Willats. He saw the clerk open the bonds, call them out to another clerk, and put them in a basket behind him.

Mr. Walter James Willats, clerk to Messrs. Schaap and Hilburn, corroborated the evidence of the last witness. He added that he could not recognise the Prisoner Wilson, and Montague’s ticket was attached to the bonds when he received them.

He put the name of Mr. Lambrinudi to them when he placed them in the basket. They were to be delivered to Mr. Lambrinudi. When the bonds were missed, Witness made inquiry about them, but without result.

Mr. Alfred Capern, a clerk in the employ of Messrs. Birch and Co., stockbrokers, stated that on the 12th of April he was in service of Messrs. Schaap and Hilburn. He was present when the Witness Fuller recieved the bonds referred to, and marked in the book the particulars of the bonds. The basket in which the bonds were placed was taken out the room to the general office by Mr. Willats, he believed. Witness did not recognize the prisoner as having been in Messes. Schaap and Hilburn’s office.

Mr. Abrahams said he could prove that other bonds had to be purchased and handed over to Mr. Lambrinudi, in lieu of those that were lost.

Mr. Alderman Phillips said he did not think it necessary to produce such evidence.

This was the case against the Prisoner on the second charge, and as he had nothing to say, but reserved his defence, he was committed for trial.

Afterwards the Prisoner said he desired the benefit of Counsel, but was poor and had no means.

Mr. Alderman Phillips said the Prisoner must make his application to the Court at which he would be tried.

Mr. Abrahams said he would see that the matter was mentioned in the proper quarter.

A further application by the Prisoner for the money found in his possession was at once acquiesced in, the prosecution offering no objection.

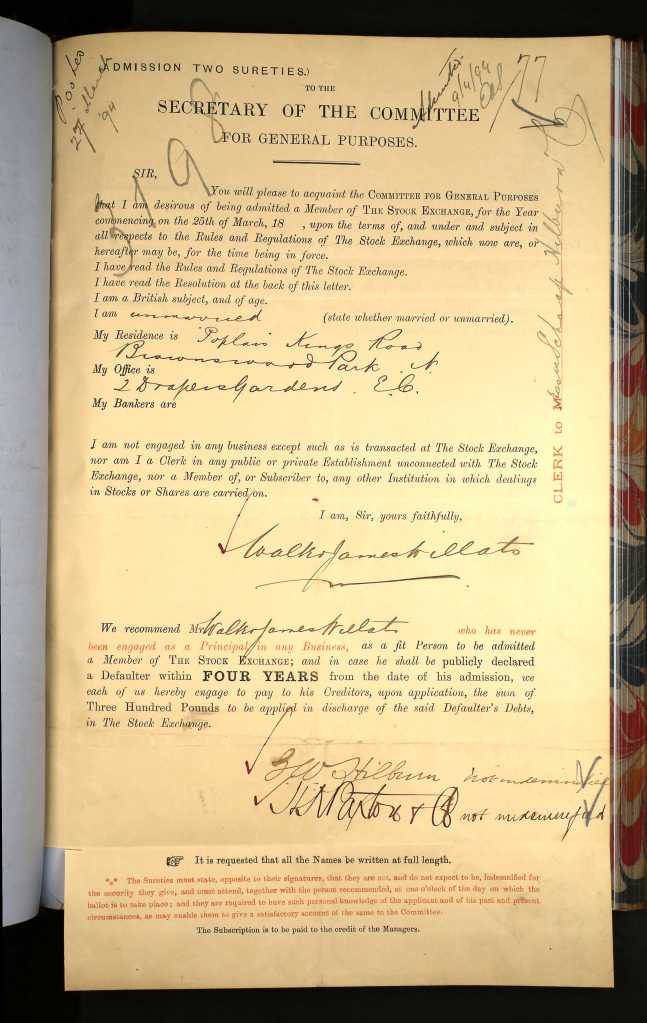

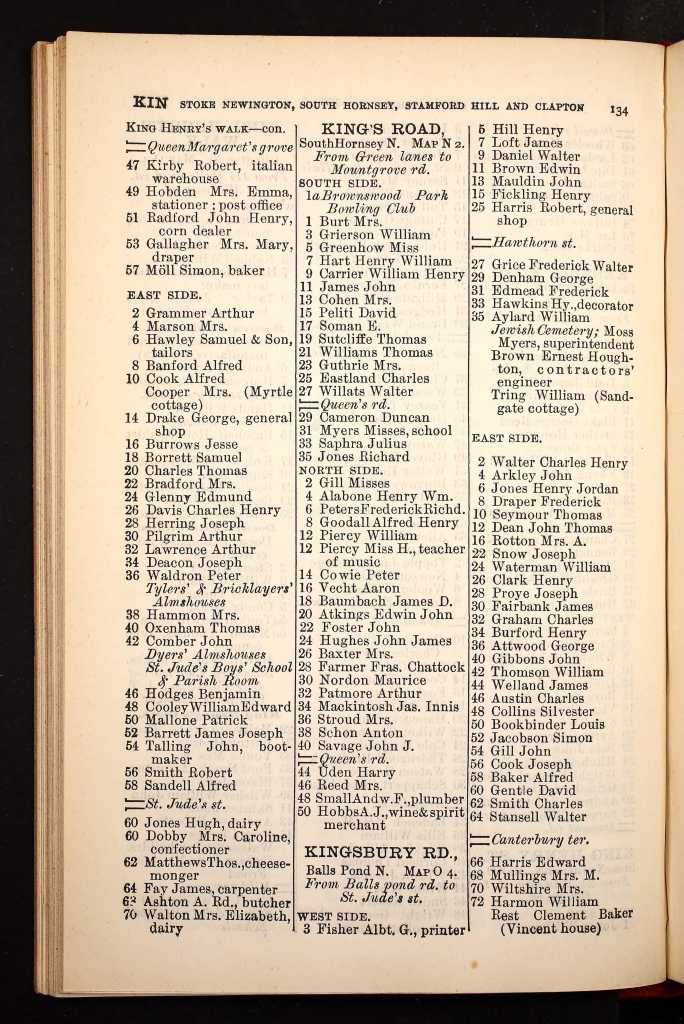

From the 1766 - 1946 UK, City and County Directories, we know, Walter was residing at Number 27, Kings Road, Finchley Park, Islington, Middlesex, England, in 1890.

Walter, his parents Eliza, and Richard and Walter’s siblings, May, Sidney, Mary, Frederick, Lily and Edwin, were residing at Number 27, Kings Road, Hornsley, Islington, Middlesex, England, on Sunday the 5th of April, 1891. Walter was working as a Stockbroker Clarke, his father Richard was working as a Self Employed Survivor, and his brother Edwin was working a Survivors Clarke.

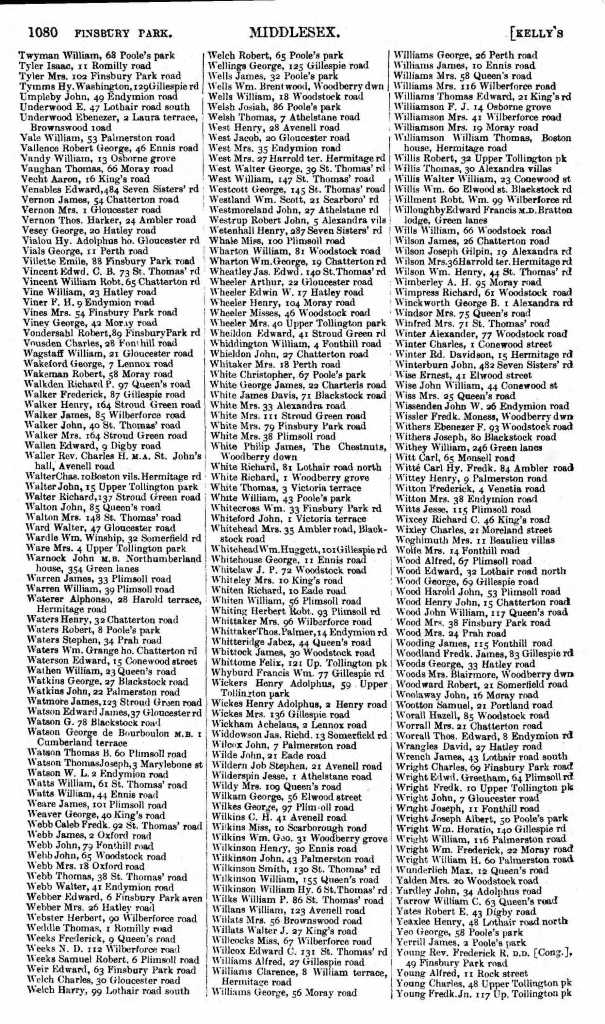

Walter’s 1894 London, England, Stock Exchange Membership Applications, shows us that, Walter was residing at Poplain Kings Road, Brownwood Park, South Hornsey, Edmonton, Middlesex, England in 1894. His office address was, Number 2 Drapers Gardens.

The 1894 London, England, City Directories, confirms that Walter was residing at Number 27, Kings Road, Brownwood Park, South Hornsey, Edmonton, Middlesex, England in 1894.

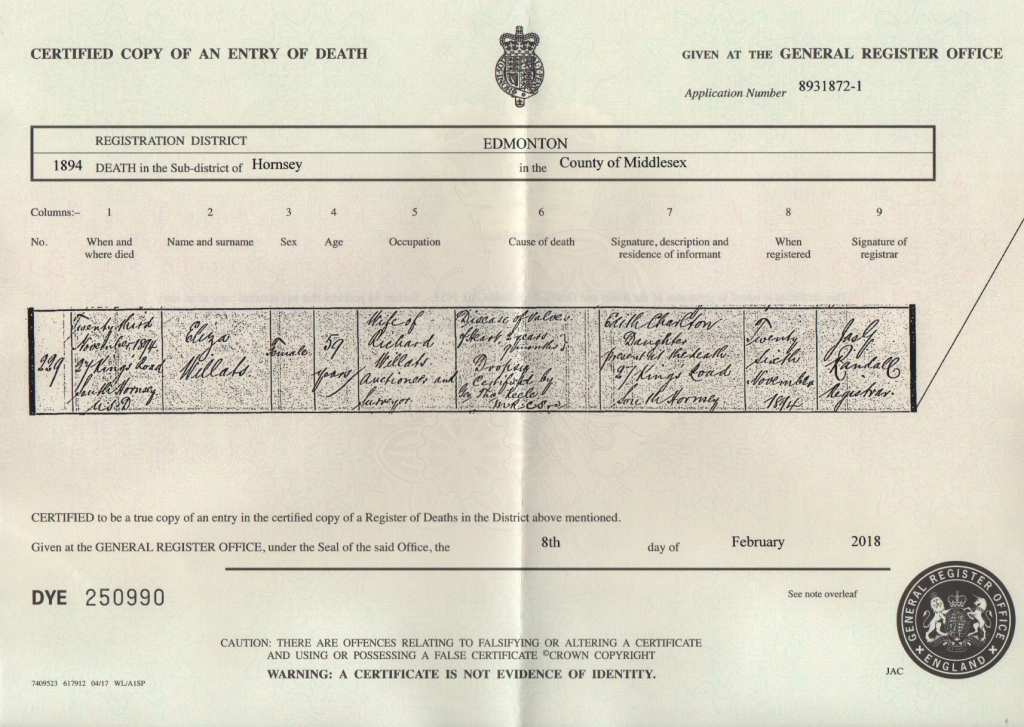

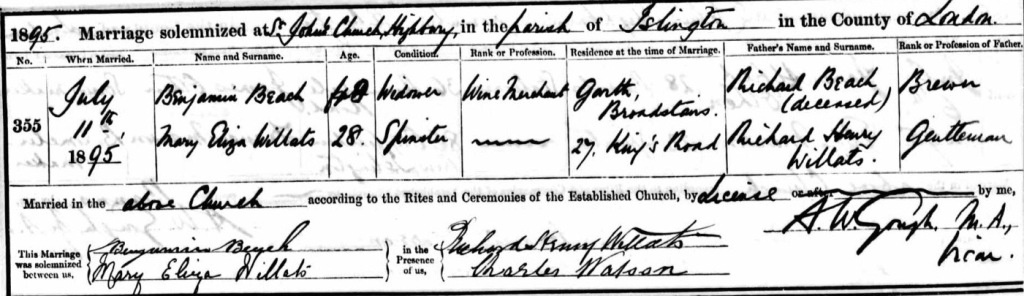

Walter’s mum, Eliza, passed away on Friday the 23rd of November 1894, at Number 27, Kings Road, South Hornsey, Edmonton, Middlesex, England, when she was 59 years old. Eliza died from, disease of valves of the heart two years nine months and dropsy. Her daughter Edith Charlton of Number 27, Kings Road, South Hornsey, was present and registered Eliza’s death on the 26th of November 1894.

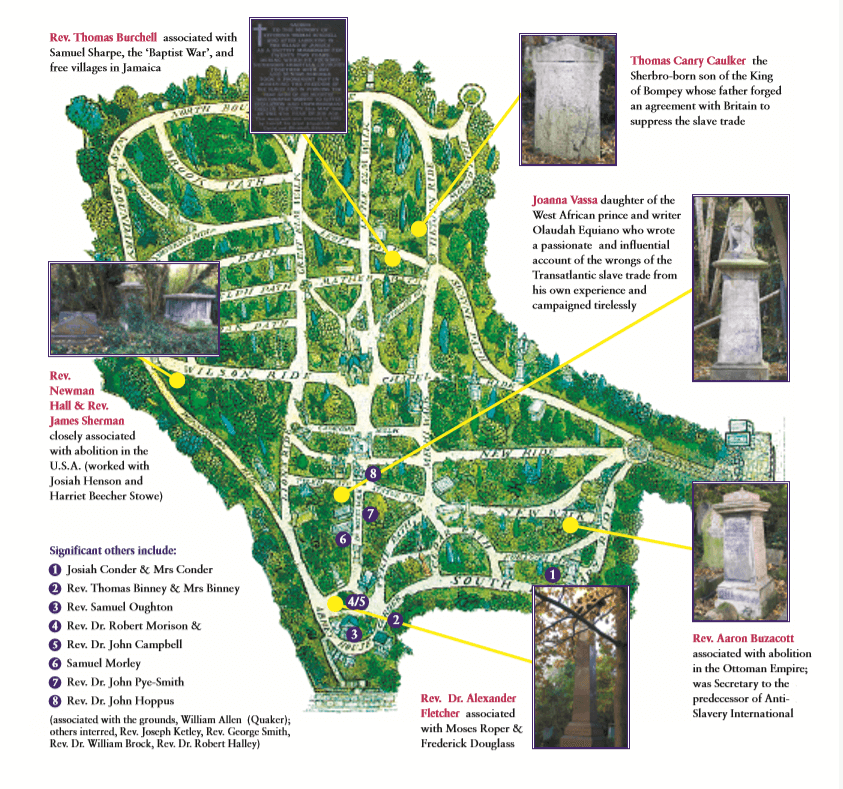

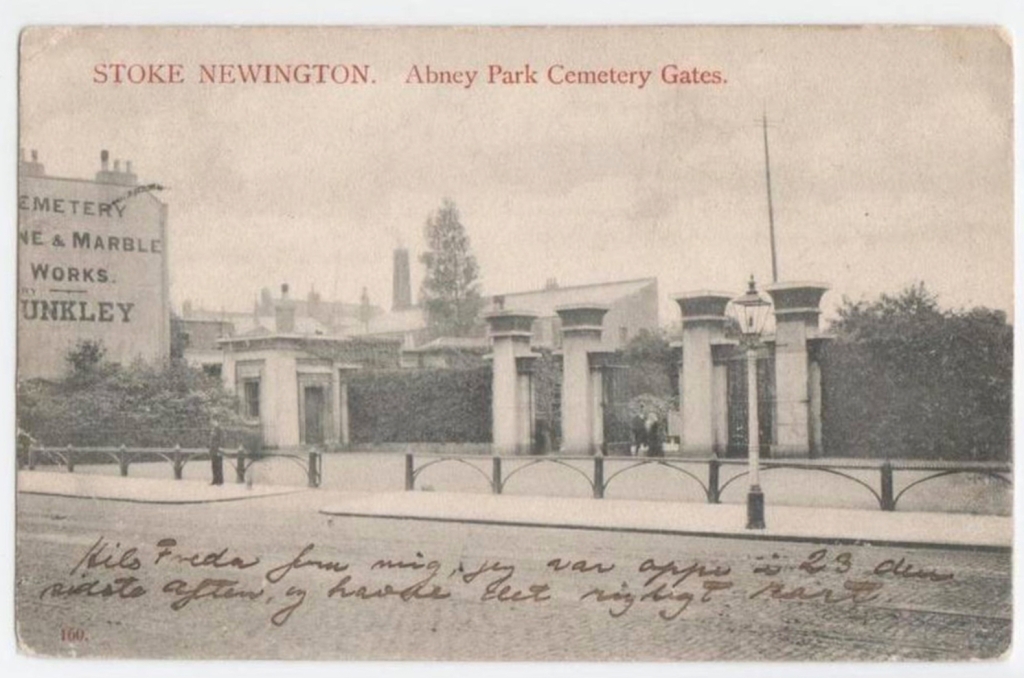

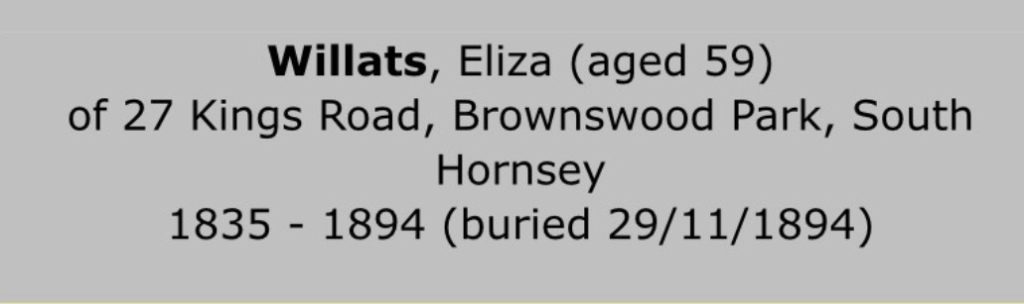

The Willats family, family, laid Eliza to rest, in, Abney Park Cemetery, Stoke Newington, Middlesex, England, on Thursday the 29th of November, 1894, in D06, Grave 092431. Her abode was given as, Number 27, Kings Road, Brownswood Park.

When Eliza died Walter’s father, Richard Henry, purchased 2 graves in Abney Park Cemetery, which was then the beautiful garden of a big house turned into a private cemetery. Each grave cost, 3 guineas and took six interments.

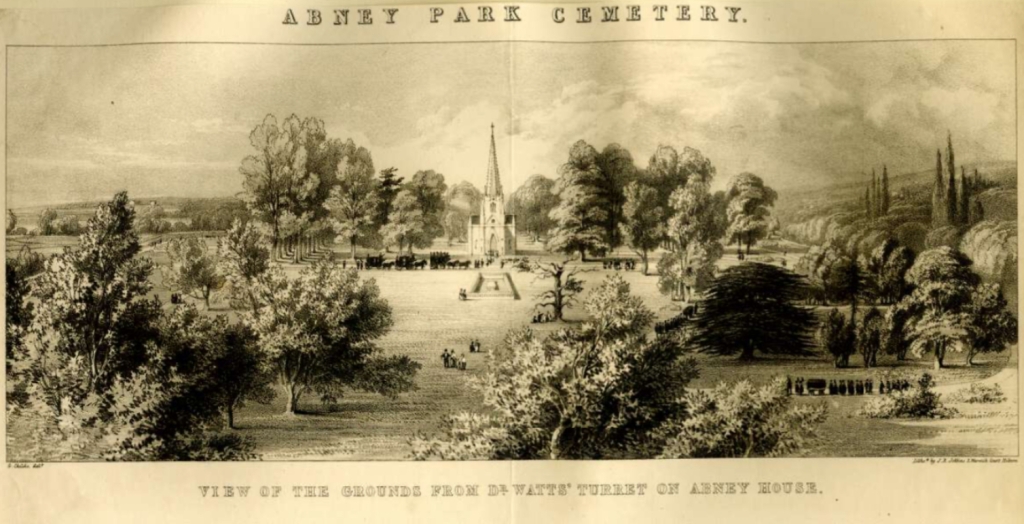

Abney Park Cemetery, located in Stoke Newington, North London, is one of the "Magnificent Seven" garden cemeteries established in the Victorian era. Opened in 1840, this historic cemetery has a unique charm, blending natural beauty with rich history, and serves as a testament to Victorian funerary customs and urban planning.

The cemetery was originally conceived as a non-denominational burial ground, a revolutionary idea at the time. This progressive approach was largely influenced by its founders, George Collison and the Nonconformist philanthropist, Sir Thomas Abney. Unlike many other cemeteries of the era, Abney Park was designed to accommodate people of all faiths and social standings, reflecting the inclusive ethos of its creators. This vision is evident in the diversity of the monuments and graves scattered throughout its grounds.

One of the most striking features of Abney Park Cemetery is its layout. Designed as an arboretum and a landscaped garden cemetery, it offers a peaceful retreat from the hustle and bustle of city life. The cemetery is home to a wide variety of trees and plants, carefully selected to create a serene and contemplative environment. Visitors can stroll along winding paths lined with towering oaks, weeping willows, and ancient yews, all contributing to the cemetery's tranquil atmosphere. The Victorian fondness for botany is evident in the carefully curated flora, making it not just a place of remembrance, but also a sanctuary for nature enthusiasts.

At the heart of Abney Park Cemetery stands the Gothic chapel, an architectural gem designed by William Hosking. Although now a ruin, the chapel remains a poignant symbol of the cemetery's historical and cultural significance. Its crumbling walls and ivy-covered façade evoke a sense of melancholy beauty, reminiscent of Romantic literature and art. The chapel originally served as a place for funeral services and was a focal point for the community, embodying the cemetery's role as a public space for reflection and mourning.

The graves and monuments at Abney Park Cemetery tell countless stories of Victorian life and death. The cemetery is the final resting place of many notable figures, including the famous hymn-writer Isaac Watts, who significantly influenced English hymnody. His tomb, along with those of other prominent individuals like the anti-slavery campaigner and poet James Stephen, and the pioneering feminist and social reformer Annie Besant, make the cemetery a historical treasure trove.

Despite its serene beauty, Abney Park Cemetery has faced challenges over the years. By the mid-20th century, the cemetery had fallen into neglect, with many graves and monuments succumbing to the ravages of time and nature. However, the Abney Park Trust, established in the 1990s, has worked tirelessly to restore and maintain the cemetery, ensuring its preservation for future generations. Their efforts have transformed the cemetery into a cherished green space, a haven for wildlife, and a site of historical education and community events.

Today, Abney Park Cemetery is a place where history, nature, and community intersect. It offers a unique glimpse into Victorian attitudes towards death and remembrance, while also serving as a green oasis in the heart of London. Visitors can explore its winding paths, discover its rich history, and enjoy its natural beauty, making it a poignant and peaceful retreat.

In addition to its role as a burial ground, Abney Park Cemetery also hosts a variety of events and activities throughout the year. From guided historical tours to wildlife walks and educational workshops, there are numerous opportunities for visitors to engage with the cemetery's rich heritage and diverse ecology. These events help to keep the spirit of the cemetery alive, fostering a sense of community and continuity amidst the tranquil surroundings.

Abney Park Cemetery stands as a testament to the enduring legacy of the Victorian era's approach to death, nature, and urban space. Its blend of historical significance, architectural beauty, and natural tranquility make it a unique and valuable part of London's cultural landscape. As a place of remembrance and reflection, it continues to offer solace and inspiration to all who visit.

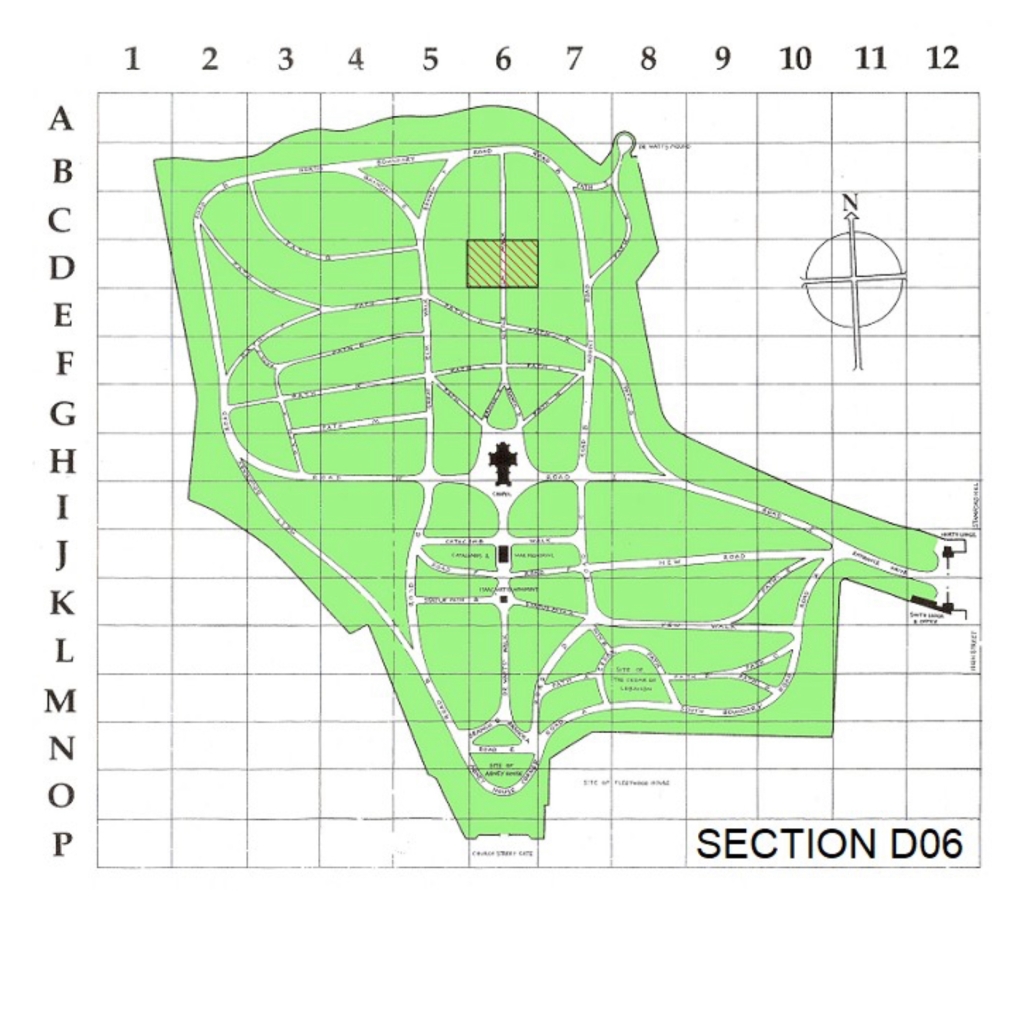

Thankfully Walter and his family had a reason to celebrate when Walter’s sister, 28-year-old, spinster, Eliza Mary Willats, married 48-year-old Widower, and wine merchant, Benjamin Beach, the following year, on Thursday the 11th of July 1895, at St John’s Church, Highbury, Islington, Middlesex, England. Mary gave her residence as, 27 Kings Road and Benjamins as . (If you can work it out, please let me know.) They gave their father’s names and occupations as, Richard Beach (deceased) a Brewer and Richard Henry Willats, a Gentleman. Their witnesses were, her father Richard Henry Willats and Charles Watson. Eliza was using the name Mary Eliza Willats (her maiden name.).

Walters sister wasn’t the only person who had found love. Walter himself had found the love of his life and by 1896 was courting. But what was courting/dating aka stepping out like in 1896?

Dating in 1896 was quite different from modern dating, with strict social norms and elaborate customs that governed interactions between men and women. The period was characterized by formality and a strong adherence to Victorian social codes.

Young men and women rarely spent time alone together without supervision. Courtship was often a family affair, with parents or chaperones playing an essential role in overseeing interactions to ensure propriety. These interactions were typically limited to formal occasions such as balls, dinner parties, and church events, where the presence of a chaperone was guaranteed.

Public displays of affection were frowned upon, and physical contact was minimal, often limited to a brief touch of hands during a dance.

The attire worn during courtship reflected the era's emphasis on propriety and status. Women typically donned long dresses made of luxurious fabrics like silk or velvet, often adorned with lace, ribbons, and other embellishments. Their outfits were complemented by accessories such as gloves, bonnets, and parasols. The dresses featured high necklines and long sleeves, emphasizing modesty. Men, on the other hand, wore formal suits or frock coats, complete with waistcoats, cravats, and top hats. The style was elegant and conservative, reflecting the formality of the occasion and the seriousness of courtship.

Courtship rituals involved a series of carefully orchestrated steps. Initially, a young man would express his interest in a young woman by visiting her home and paying respects to her family. These visits were formal and often included engaging in polite conversation and partaking in tea. If the family approved of the young man, he would be invited to accompany the family to social events, where he could spend more time with the young woman under the watchful eyes of her parents or chaperones.

Letters played a significant role in Victorian courtship, allowing couples to express their feelings more freely than in person. These letters were often elaborate, filled with flowery language and poetic expressions of affection. The exchange of letters was a vital part of the courtship process, allowing couples to deepen their emotional connection while maintaining propriety.

Engagements were taken very seriously and were often considered almost as binding as marriage itself. Once a couple decided to become engaged, they would announce it formally to their families and friends. Engagements could be long, allowing the couple to continue getting to know each other while preparing for their future together. Breaking off an engagement was a serious matter and could result in social disgrace for both parties, especially the woman.

Throughout the courtship process, the role of social class and status was paramount. Marriages were often seen as alliances that could enhance the family's social standing or economic stability. As such, young people were encouraged to court and marry within their social class. Marriages based on love alone were considered idealistic but not always practical, given the period's social and economic constraints.

In summary, dating in 1896 London was a highly structured and formal affair, characterized by strict social norms, elaborate customs, and a strong emphasis on propriety and social status. The process was meticulously supervised, with a significant role played by family and social conventions to ensure that interactions between young men and women were conducted with the utmost decorum.

Walter’s courtship must have gone well and was soon engaged to be married to the love of his life Amelia High.

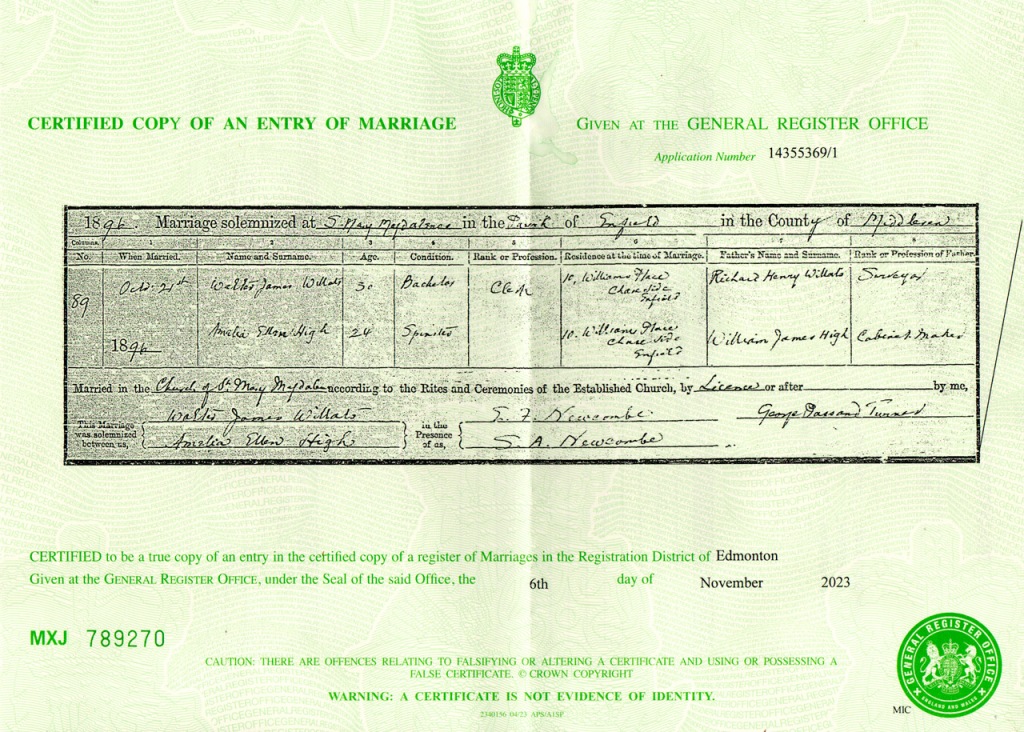

21-year-old, bachelor, Walter James Willats and 21 years and upwards, spinster, Amelia High, Marriage Bonds were licensed on Tuesday 20th October 1896, at St Mary Magdalene, Enfield, Middlesex, England.

Their marriage licence reads as follows.

DIOESE OF LONDON.

20th October 1896

APPEARED PERSONALLY, Walter James Willats of the parish. of St Mary Magdalene Enfield in the County of Middlesex a Bachelor aged Twenty one years and upwards and prayed a Licence for the Solemnization of Matrimony in the parish church of St Mary Magdalene Enfield aforesaid between him and Amelia Ellen High of the same parish a spinster of the age of Twenty-one years and upwards and made Oath that he believeth that there is no Impediment of Kindred or Alliance, or of any other lawful cause, nor any Suit commenced in any Ecclesiastical Court to bar or hinder the Proceeding of the said Matrimony, according to the tenor of such Licence. And he further made Oath, that he the said Appearer hath had his usual Place of abode within the said parish of St Mary Magdalene Enfield. for the space of Fifteen days last past

Walter James Willats

Sworn before me

F S May Swn:

30-year-old, Bachelor, Walter James Willats, a Clark, married 24-year-old spinster, Amelia Ellen High on Wednesday 21st October 1896, at the church of St Mary Magdalene, Enfield, Middlesex, England.

They gave their residence at the time of their marriage as, Number 10, William Place, Chase Side, Enfield.

They gave their fathers names and occupations as, Richard Henry Willats, a Surveyor and William James High, a cabinet Maker.

Their witnesses were, E. F. Newcombe and S. A. Newcombe.

St Mary Magdalene, Enfield, is a Church of England church in Enfield, London, dedicated to Jesus’ companion, Mary Magdalene. The building is grade II* listed with Historic England. The church was built as a memorial to Philip Twells, MP and city banker, by his wife Georgiana Twells, who employed the architect William Butterfield. The foundation was stone was laid in 1881 and the church opened in 1883. The artist Charles Edgar Buckeridge painted the ceiling and east wall of the sanctuary and after his early death the side walls were painted by Nathaniel Westlake. The walls and ceiling were conserved in 2012 by Hirst Conservation with the help of local donations and the Heritage Lottery Fund. The stained-glass windows are by Heaton, Butler and Bayne.

The tower originally contained 8 change ringing bells cast by John Warner & Sons for the new church in 1883, however these were replaced in 1999, as they were too heavy for the tower and were causing damage. The church installed a new, lighter ring of 8 bells cast by the Whitechapel Bell Foundry, and the older, larger bells were bought by Grace Church Cathedral in Charleston, United States, where they were installed and augmented to 10 with two new treble bells cast in the same year, also by Whitechapel.

As we draw the curtains on the first chapter of Walter James Willats' life journey, we find ourselves immersed in the vibrant tapestry of 19th-century London. From his humble beginnings on Charlotte Street in Marylebone, All Souls, Middlesex, England, Walter embarked on a odyssey that would ultimately lead him to the hallowed halls of the London stock exchange.

As we've traced Walter's early years, we've unearthed the foundations upon which his future successes would be built, a tenacious spirit, an unwavering determination, and a hunger for opportunity.

From his upbringing in the bustling streets of London to the pivotal moments that shaped his path, Walter's story serves as a testament to the resilience and ambition that defined his generation.

As we bid adieu to this chapter of Walter's life, we carry forward the lessons learned and the stories shared, eager to delve deeper into the intricacies of his remarkable journey. Join us as we continue to unravel the enigmatic tapestry of Walter James Willats' life, exploring the triumphs, tribulations, and timeless tales that await in the chapters yet to come.

Until next time,

Toodle pip.

Yours Lainey.

🦋🦋🦋

I have brought and paid for all certificates,

Please do not download or use them without my permission.

All you have to do is ask.

Thank you.