In the bustling streets of London, amidst the whispers of history and the vibrant pulse of city life, there lived a man whose story danced through the epochs like a melody in the wind. His name was Frederick Howard Willats, a name woven into the fabric of London's narrative, yet often overlooked in the grand tapestry of time. But behind the veil of anonymity lay a life rich in love, struggle, and unwavering resilience.

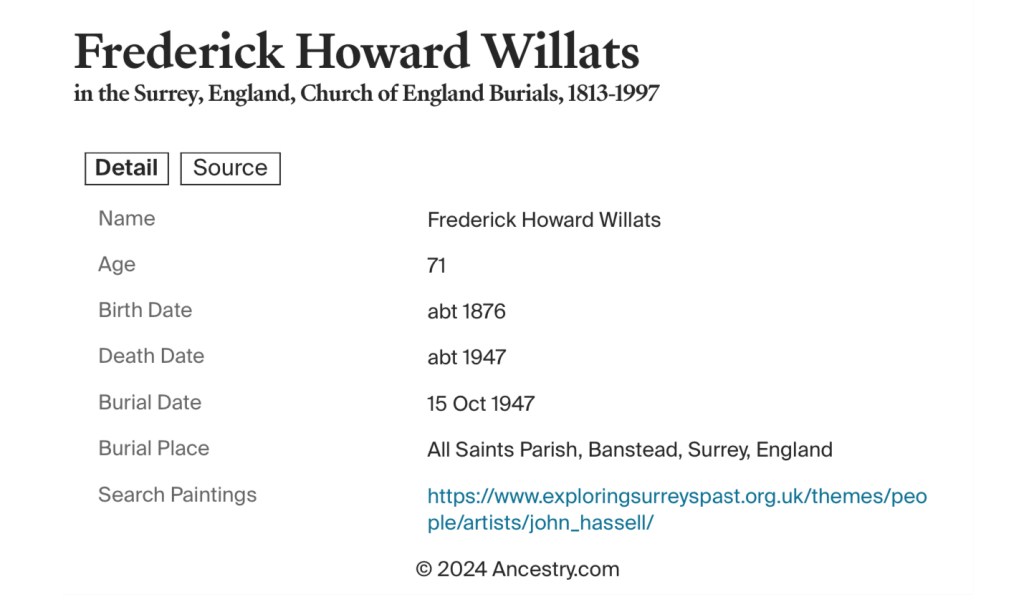

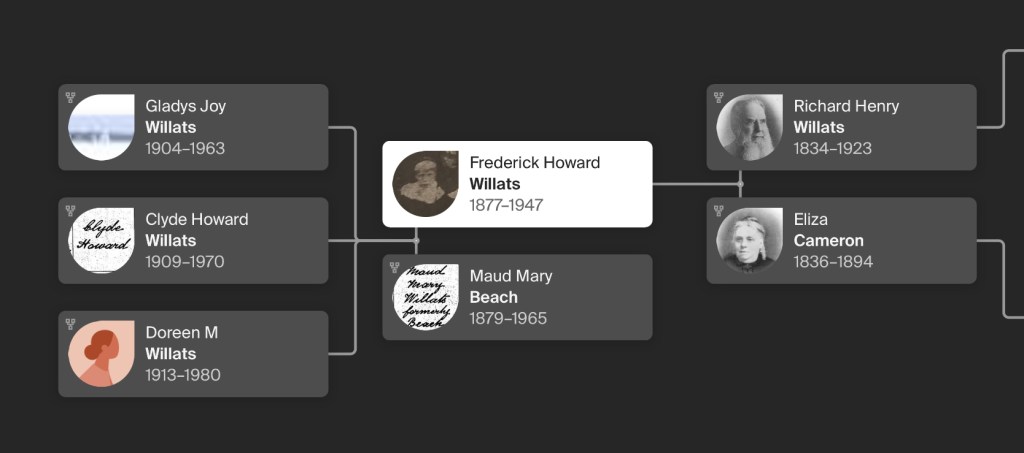

Born the youngest amidst a brood of twelve, Frederick emerged into the world as the culmination of dreams and aspirations, the product of generations past and the promise of generations yet to come. His parents, Eliza and Richard, sculpted the foundation of his existence with a love that defied the constraints of circumstance, nurturing him amidst the chaos of a bustling metropolis.

Yet Frederick's story began long before his own inception, entwined with the echoes of a familial past that stretched back through the annals of time. His mother, Eliza, bore him not only from her union with Richard but also from the legacy of a previous marriage, a bond that linked him to his uncle in both blood and spirit.

London became his playground, its streets his labyrinthine maze of discovery and wonder. From the cobbled alleyways to the towering spires, Frederick roamed with the curiosity of a child and the wisdom of a sage, absorbing the essence of his surroundings like a sponge thirsty for knowledge.

As he matured, Frederick carved his path through the urban landscape, his footsteps leaving an indelible mark upon the city he called home. Through toil and sweat, he earned his keep as a survivor, navigating the tumultuous currents of life with a steadfast determination that belied his tender years.

But amidst the hustle and bustle of London life, Frederick found solace in the arms of love. It was here, in the tender embrace of his beloved, that he discovered the true essence of his existence. Through the trials and tribulations of marriage, Frederick learned the delicate dance of compromise and compassion, weaving a tapestry of affection that bound him to his partner until death do them part.

And so, as we embark upon the second chapter of Frederick's journey, we delve deeper into the heart of his story, unraveling the threads of love, loss, and legacy that define his legacy. For in the life of Frederick Howard Willats, we find not only a man but a testament to the enduring power of the human spirit to triumph over adversity and to find beauty amidst the chaos of existence.

So without further ado I give you,

The Life of Frederick Howard Willats,

1877-1947,

Part 2,

Until Death Do Us Part.

Welcome back to the year 1904, London, England.

In 1904, London, England was amidst the Edwardian era, a period marked by prosperity, innovation, and shifting social dynamics. At the helm of the monarchy was King Edward VII, whose reign brought about a more relaxed and cosmopolitan atmosphere compared to his mother, Queen Victoria's, strict moral code. Parliament, led by Prime Minister Arthur Balfour, was navigating the complexities of a changing world, with issues such as colonialism, suffrage, and social welfare on the agenda.

Fashion in Edwardian London was characterized by elegance and opulence, especially among the upper classes. Women wore elaborate dresses with intricate detailing, while men donned tailored suits and top hats. The Gibson Girl aesthetic, with its emphasis on a tall, slender silhouette and upswept hair, was particularly popular.

Food in 1904 London reflected both tradition and innovation. While staples like roast beef and Yorkshire pudding remained favorites, the city's cosmopolitan nature introduced new culinary influences from around the globe. The rise of department stores like Harrods and Selfridges offered a wide array of exotic ingredients and delicacies to the affluent population.

Transportation underwent significant changes during this time, with the introduction of electric trams and the expansion of the London Underground. Horse-drawn carriages still traversed the streets, but the cityscape was increasingly dotted with automobiles, signaling the dawn of a new era in transportation.

The aroma of Edwardian London varied greatly depending on one's location. In the affluent neighborhoods of Mayfair and Kensington, the air might be perfumed with the scent of flowers from manicured gardens, while in the bustling East End, it could be tinged with the smell of industrial pollution and overcrowding.

Heating and lighting in Edwardian homes relied primarily on coal, which powered both fireplaces and gas lamps. While electricity was becoming more widespread, especially in wealthier households, many Londoners still relied on more traditional methods for warmth and illumination.

Sanitation was a pressing issue in 1904 London, particularly in the densely populated slums of the East End. The implementation of the Metropolitan Board of Works' sewage system had improved conditions somewhat, but overcrowding and poor infrastructure still contributed to the spread of disease.

Social standards in Edwardian London were rigidly stratified, with a clear distinction between the rich, working class, and poor. The upper classes enjoyed luxurious lifestyles filled with leisure pursuits and social gatherings, while the working class toiled in factories and workshops for meager wages. The impoverished residents of the slums struggled to make ends meet, living in squalid conditions with limited access to basic amenities.

Gossip was a popular pastime among London's elite, with society newspapers and gossip columns fueling the rumor mill. High-profile scandals and affairs captured the public's attention, providing fodder for lively dinner party discussions and salacious headlines.

The environment of Edwardian London was undergoing rapid change, as industrialization and urbanization transformed the cityscape. Parks and green spaces provided oases of tranquility amidst the hustle and bustle of urban life, while pollution and overcrowding posed significant challenges to public health and well-being.

Entertainment options in 1904 London were diverse, catering to a wide range of tastes and preferences. The West End theaters showcased lavish productions and musicals, while music halls and variety shows provided more populist forms of entertainment. Sporting events like horse racing and cricket were also immensely popular, drawing crowds of spectators from all walks of life.

The climate in London during 1904 would have been typical for the time of year, with cool temperatures in the winter months and milder weather in the spring and summer. Rainfall was common throughout the year, contributing to the city's lush greenery and verdant parks.

Important historical events and figures of 1904 London include the Anglo-French Entente, a diplomatic agreement between Britain and France aimed at countering German expansionism; the founding of the London School of Economics by Fabian Society members Sidney and Beatrice Webb; and the publication of Joseph Conrad's novel "Nostromo," which explored themes of imperialism and corruption in a fictional South American country.

As we know from part one of Frederick's life story through documentation, Frederick had just married his sweetheart, Maude Mary Beach the year before on Saturday the 19th September 1903 at St. John’s Church, Highbury Vale, Islington, London, England.

Married life in 1903 England was a reflection of the societal norms and expectations deeply entrenched in the fabric of Victorian society. For newlyweds, the confirmation of marriage marked not only a union of hearts but also a merging of destinies, with each partner expected to adhere to their prescribed roles within the marriage.

For Frederick and his bride, the expectations placed upon his wife were often defined by the rigid gender roles of the time. As the patriarch of the household, Frederick was expected to provide for his family financially, acting as the primary breadwinner whose duty it was to ensure the welfare and stability of his household.

Conversely, his wife's role was predominantly confined to the domestic sphere, where her responsibilities revolved around maintaining the home and caring for the needs of her husband and children. From cooking and cleaning to tending to the emotional well-being of her family, the wife's duties were exhaustive and unyielding, with little room for deviation from societal expectations.

Moreover, the expectations placed upon Frederick's wife extended beyond the confines of the home. She was also expected to embody the virtues of piety, modesty, and submission, adhering to the societal standards of femininity that dictated her behavior and appearance.

In terms of marital expectations, Frederick's wife was anticipated to be a supportive and dutiful partner, whose primary role was to complement and bolster her husband's endeavors. Her loyalty and devotion were seen as essential components of a successful marriage, with her husband's reputation and social standing often hinging upon her ability to fulfill these expectations.

However, despite the rigid delineation of gender roles, the dynamics of marriage in 1903 England were not without their complexities. While Frederick held the reins of authority within the household, his wife wielded her influence in more subtle yet profound ways, shaping the atmosphere of the home and exerting her influence over familial matters.

In essence, the married life of Frederick and his wife in 1903 England was a delicate balancing act between tradition and evolution, where societal expectations intersected with the intricacies of personal dynamics and individual aspirations. And amidst the constraints of convention, their union forged a bond that transcended the confines of time, embodying the enduring spirit of love and partnership that defines the essence of marriage itself.

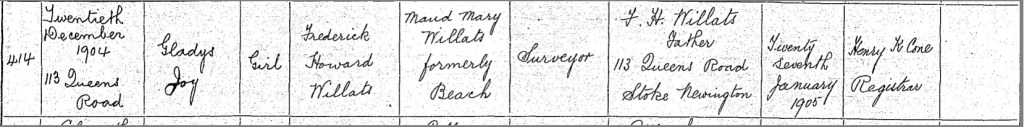

Before long, Maude found herself expecting a child, bringing new joy and anticipation into their lives. On a crisp winter day, Tuesday, December 20, 1904, their daughter, Gladys Joy Willats, made her debut into the world. She was born at the family’s home, a modest but warm residence at Number 113 Queens Road, in Stoke Newington, Hackney, Middlesex, England.

It was Frederick who proudly registered her birth over a month later, on January 27, 1905, at the local registry office in Hackney. On the official record, he listed his profession as a surveyor and confirmed their address as Number 113 Queens Road.

The family must have felt the weight of this milestone, not just as new parents but as residents of a bustling neighborhood with its own rhythm and history. While the address is documented as Queens Road at the time, there’s some reason to believe that in the years since, this street has been renamed Queens Drive. This detail, though small, is a poignant reminder of how even places that hold personal significance can evolve and change with the passage of time.

In 1904, London was undergoing significant urban development and expansion, creating a high demand for skilled professionals like surveyors. The role of a surveyor during this time was crucial in various aspects of construction, infrastructure development, and land management. Surveyors were responsible for measuring and mapping land, assessing property boundaries, and providing technical expertise in construction projects.

Securing a job as a surveyor in 1904 London was typically competitive and required a combination of qualifications, skills, and practical experience. While formal education in surveying was not as standardized as it is today, many surveyors obtained their knowledge through apprenticeships or on-the-job training under experienced practitioners. These apprenticeships provided hands-on experience and exposure to various surveying techniques and tools.

Qualifications for surveyors in 1904 often included a strong foundation in mathematics, geometry, and drafting skills. Practical knowledge of surveying instruments such as theodolites, chains, and levels was essential. Additionally, familiarity with local laws and regulations regarding land use and property rights was important for conducting surveys accurately and ethically.

Advancement in the surveying profession during this time often involved a combination of experience, reputation, and further education. As surveyors gained expertise and built a reputation for accuracy and reliability, they could attract more clients and take on larger projects. Some may have pursued additional qualifications or certifications to specialize in specific areas of surveying, such as hydrographic surveying or cadastral mapping.

Networking and establishing connections within the industry were also crucial for career advancement. Building relationships with architects, engineers, developers, and government officials could lead to new opportunities and collaborations on significant projects.

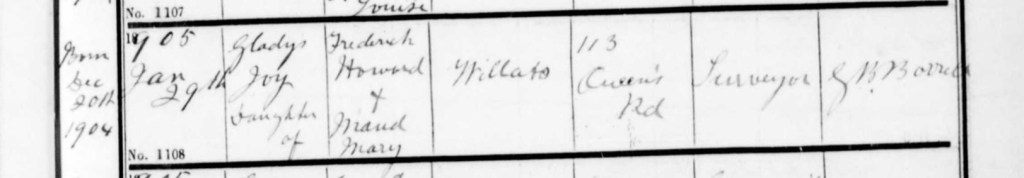

On a Sunday morning, the 29th day of January, 1905, Frederick and Maud brought their precious daughter, Gladys Joy Willats, to be baptized. The ceremony took place at the serene and welcoming Saint John the Evangelist Church, nestled near Brownwood Park on Gloucester Drive, Hackney, Middlesex, England. It must have been a heartfelt moment, filled with both solemnity and hope, as they stood together before the altar, entrusting their little one to the care of faith and community.

Frederick’s profession was recorded as a surveyor, a detail that hints at the stability and care he worked to provide for his growing family. Their home, lovingly listed as Number 113 Queens Road, was undoubtedly the hub of their new life as parents. It’s easy to imagine them, proud and perhaps a little awed, marking this special day in their journey with gratitude and love.

The Church of England church was originally known as Saint John, South Hornsey. The church was consecrated in 1874 and became known as Saint John the Evangelist, Brownswood Park. The name was changed to Saint John the Evangelist, Finsbury Park some time after 1955 in order to more accurately reflect the location of the church.

The church was also associated with Gloucester Drive, in the parish of Hackney.

Far across the Atlantic, life was unfolding in ways both joyous and bittersweet for the Willats family.

On Wednesday, June 17, 1908, Frederick’s brother, Arthur Charles Willats, a 43-year-old widower and salesman, began a new chapter. He married Ruth Gadsby, a 30-year-old spinster and actress, in a ceremony held at Niagara Falls, Welland, Niagara, Ontario, Canada.

It must have been a day of mixed emotions. For Arthur, it marked a new beginning, a chance to build a future after the loss of his first wife. For Frederick, their father Richard, and the rest of the family left behind in England, it must have been difficult not to be there to share in the celebration. The separation, dictated by oceans and the constraints of early 20th-century travel, would have been keenly felt. Letters, perhaps a photograph, and the hope of a future reunion were all they had to bridge the distance.

Niagara Falls in 1908 was already a destination that inspired awe and wonder. The thundering cascade of water symbolized natural beauty and power, and by this time, the area had grown into a bustling hub for travelers. The establishment of hydroelectric power plants and railroads had transformed the surrounding region, making it a beacon of progress and possibility. It’s easy to imagine how the setting might have added a sense of grandeur and romance to Arthur and Ruth’s special day.

While Frederick and the family in England celebrated from afar, they must have sent their heartfelt wishes, knowing that this union was not just about a wedding but a testament to resilience, hope, and the enduring ties of family.

Back in England, the summer of 1909 brought its own moment of celebration for the Willats family.

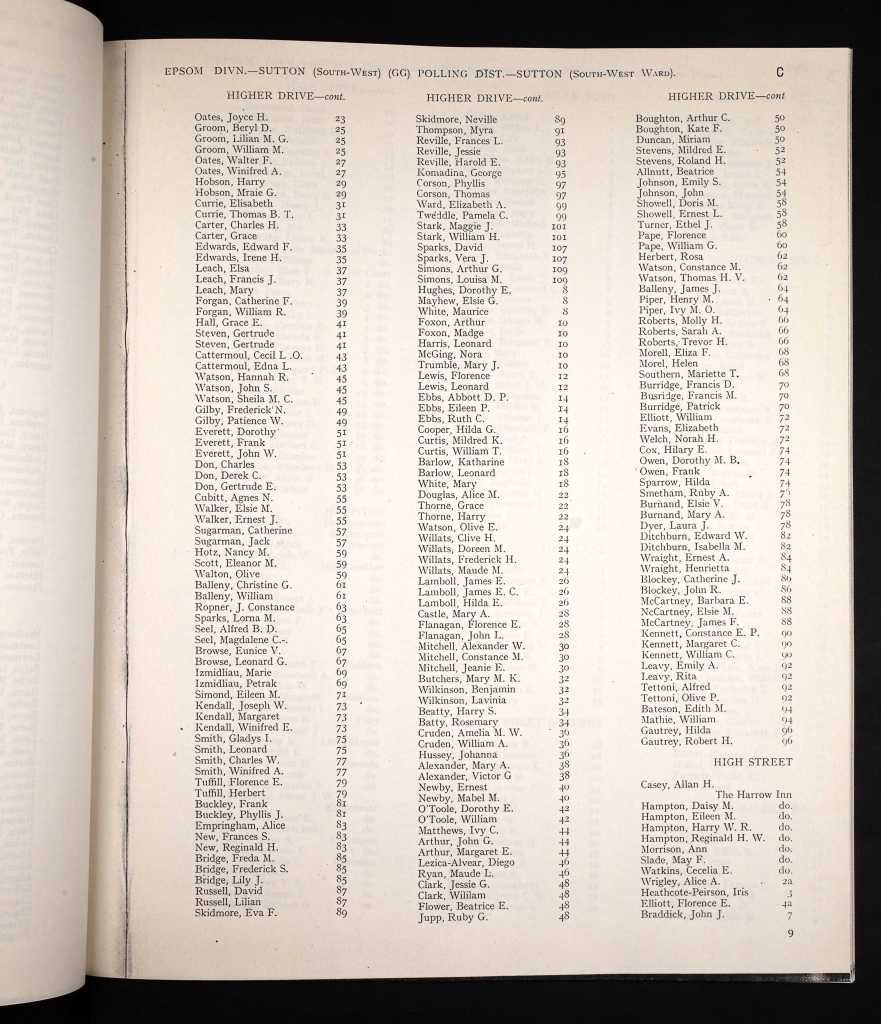

On a warm Saturday, July 24, 1909, Frederick’s younger brother, Percy Sidney Willats, exchanged vows with Sophie Ann Smart, marking the beginning of their life together. The couple, 33 and 25 years old respectively, chose the Register Office in Edmonton, Middlesex, England, for their ceremony, a choice that may reflect a desire for simplicity or practicality amidst the bustle of their lives.

Standing by their side as witnesses were E.P. Willats, likely fredericks brother Edwin Paul, lending a steady presence, and J.H. Champion.

Percy listed his occupation as an auctioneer, following in the professional footsteps of their father, Richard Henry Willats, who was also an auctioneer. Sophie’s father, John Smart, was noted as a market gardener, a role that speaks to a life connected to the earth and the rhythms of growth and harvest.

The newlyweds gave their address as Number 11 The Quadrant, Winchmore Hill, Edmonton, a home that would now serve as the foundation for their future together. One can imagine the couple, filled with hope and anticipation, beginning to weave their lives into the fabric of this quiet suburban neighborhood.

For the family, this wedding must have been a bright moment, a chance to gather, celebrate, and look toward the future. Amid the realities of daily life and responsibilities, it was a reminder of the bonds that tied them together and the enduring importance of love, commitment, and family traditions.

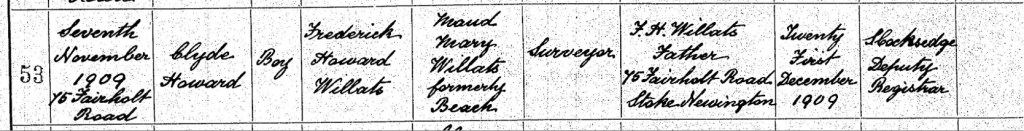

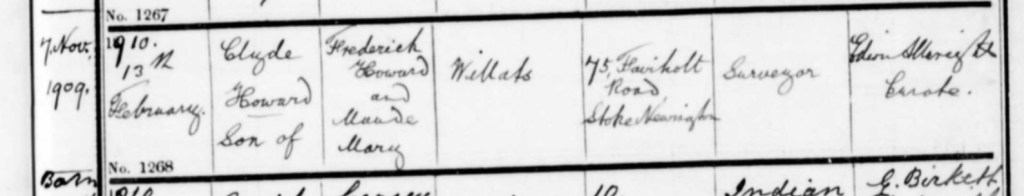

Just a few short months after Percy and Sophie’s wedding, Frederick and Maud were blessed with a joyous occasion of their own. On a crisp Sunday, November 7, 1909, their son, Clyde Howard Willats, was born, filling their home with the unmistakable joy and wonder that only the arrival of a child can bring. He came into the world at Number 75 Fairholt Road, Stoke Newington, Middlesex, England, a place that was surely brimming with excitement as the couple welcomed their second child.

The moment of his birth, no doubt, was one of mixed emotions, tired yet overjoyed, filled with awe at the new life they had created.

Frederick, as any proud father would, registered Clyde’s birth on December 21, 1909. In doing so, he marked this milestone with a quiet pride, listing his occupation as a surveyor, just as he had done for their daughter, Gladys, a few years earlier.

Their home at Number 75 Fairholt Road must have felt all the more special with the new addition, a place now full of the sounds and warmth of a growing family.

Clyde’s arrival brought new life to the Willats household, and Frederick and Maud must have felt a renewed sense of hope and joy for the future, knowing their little boy would grow up surrounded by love and the familiar embrace of their close-knit family.

Fairholt Road is a residential street located in Stoke Newington, which was historically part of Middlesex but is now in the London Borough of Hackney. The road itself is part of an area that underwent significant change from the late 19th century onwards, transforming from more rural and undeveloped land into a desirable suburban neighborhood with large Victorian homes and wider streets. This area became popular with the middle class and professionals who were drawn to its proximity to central London but appreciated its quieter, more residential nature.

The name "Fairholt" is believed to be a relatively modern invention, possibly inspired by the presence of trees or wooded land in the area during its early development. In the mid-to-late 1800s, the area around Stoke Newington was transformed with the construction of residential streets like Fairholt Road, which reflected the growing prosperity of the area. This period saw the construction of elegant terraced houses, many of which still stand today, characterized by their Victorian architecture with decorative brickwork and larger windows. These homes were built for the rising middle class, professionals, and businesspeople who were settling in this part of North London as it became a more established suburban area.

The development of Fairholt Road was part of a broader movement that reshaped Stoke Newington from a rural village to an urban district. While the southern parts of Stoke Newington remained more densely populated with smaller homes, the northern areas, where Fairholt Road is located, became home to those who sought more space and comfort. The expansion of railways and the growth of local amenities also made this area increasingly attractive to those looking to live away from the city’s hustle but still within easy reach of London.

While there is no specific historical record detailing notable families who lived at Number 75 Fairholt Road, the street itself has been associated with the broader history of Stoke Newington, a place that attracted many distinguished figures. Notable residents of Stoke Newington include artists, writers, and social reformers such as William Morris, the famous designer and writer, and Arthur Rackham, the renowned illustrator. Though they may not have resided directly on Fairholt Road, their influence in the surrounding areas speaks to the kind of community that lived here—a mixture of intellectuals, artists, and professionals who shaped the cultural and social landscape of the neighborhood.

The history of Fairholt Road itself is reflective of Stoke Newington’s transformation into a thriving urban suburb. Over the years, the street would have witnessed many changes, from the early days of its development to the growth of London itself in the 20th century. While specific details about the residents of Number 75 Fairholt Road may be harder to find, the road as a whole stands as a reminder of the area’s past, with its Victorian homes and quiet, tree-lined atmosphere continuing to tell the story of how Stoke Newington evolved into the vibrant area it is today.

On a quiet Sunday, the 13th day of February, 1910, Frederick and Maud gathered with loved ones for a deeply personal and sacred moment, Clyde Howard Willats’ baptism. The ceremony took place at St. John the Evangelist Church in Finsbury Park, Hackney, a place of solace and significance where the young family embraced their faith and welcomed their precious son into the fold of the community.

As they stood together in the church, the weight of the moment surely felt profound, Clyde, just a few months old, held close in his parents’ arms as they made promises for his future, hopeful and filled with love. On the official record, Frederick’s occupation was listed as a surveyor, and their home was noted as Number 75 Fairholt Road, Stoke Newington, a detail that tied the family to their neighborhood, the place where their children would grow and where life’s milestones would continue to unfold.

Interestingly, Clyde’s birth date was recorded as February 7, 1910, just days before his baptism. Whether there was an error in the documentation or a deliberate decision to celebrate him sooner, it’s clear that the Willats family felt the weight of the moment. The baptism marked more than just a religious ritual, it was a symbol of hope, renewal, and the start of a new chapter in their lives as parents. As Frederick and Maud held their son, they must have felt a deep sense of pride and tenderness, knowing that this day, like the birth of Clyde himself, was a milestone to be cherished for years to come.

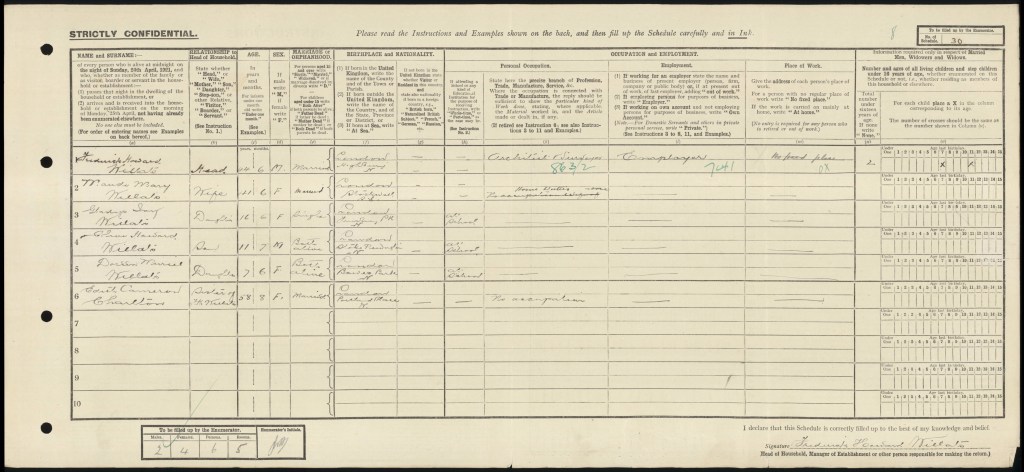

On the day of the 1911 census, Sunday, April 2nd, Frederick and his wife Maud were surrounded by family and loved ones in their home at Number 75 Fairholt Road, Stoke Newington, Middlesex. It was a busy household, with their two children, Gladys Joy and little Clyde, filling the rooms with the sounds of childhood. Maud’s mother, Emma Beach, a widow, also lived with them. Emma, who had once been a publican, was now enjoying her retirement after years of hard work in the pub trade. Maud’s aunt, the unmarried Mary Ann Baker, shared the space as well, providing a steady, familiar presence in the home.

In addition to family, the household included their 15-year-old domestic servant, Florence Mable Pellatt. Florence, no doubt, helped with the day-to-day duties around the house, contributing to the smooth running of their busy family life.

Number 75 Fairholt Road was a spacious home, with eight rooms providing ample space for this close-knit family and their domestic servant. It must have been a place filled with activity, warmth, and the quiet hum of family life.

Frederick worked diligently as a surveyor and valuer of property, a profession that required both precision and an eye for detail, much like the care he took in providing for his family. Maud, who had been married to Frederick for seven years, was the heart of the home, balancing the duties of a mother and wife with grace.

According to the census, Frederick and Maud had two children, Gladys and Clyde, and both were still living. The couple must have reflected on the joy and challenges of the years they had shared, their home now bustling with the energy of growing children and extended family. Despite the everyday duties and responsibilities, there was likely a deep sense of contentment in their lives, as they shared a home full of love, family, and the promise of the future.

Stoke Newington.

Two years after the bustle of their life at Fairholt Road, Frederick and Maud’s family grew once again with the arrival of their second daughter, Doreen Muriel Willats. It was Thursday, December 4th, 1913, when Doreen made her entrance into the world, bringing new joy to the home that had by now shifted to Number 67, Lyndhurst Road, Wood Green, Edmonton, Middlesex. The family had recently settled into this new address, and it must have felt like the perfect place to welcome another little one into their lives.

The house at Lyndhurst Road was probably filled with a sense of anticipation and love as Maud gave birth to her daughter. As with Gladys and Clyde, Doreen’s arrival no doubt brought with it an overwhelming sense of hope and excitement for the future. Frederick, still working as a respected auctioneer and surveyor, was no doubt proud of his growing family and the home he and Maud were making together.

Maud registered Doreen's birth on January 22nd, 1914, at the local registry office in Edmonton, Middlesex. She must have taken great care in filling out the details, knowing that each milestone in their children’s lives would be a cherished memory. Doreen, the new little light in their lives, would no doubt be doted on by her older siblings, Gladys and Clyde, as well as by their extended family, who had always been close-knit and supportive.

At Number 67 Lyndhurst Road, Maud and Frederick had built a home full of love and promise. It was a fresh start, a new chapter for the family to embrace, and with the arrival of Doreen, they were reminded of the beauty of family and the joy of new beginnings.

Wood Green,

Edmonton

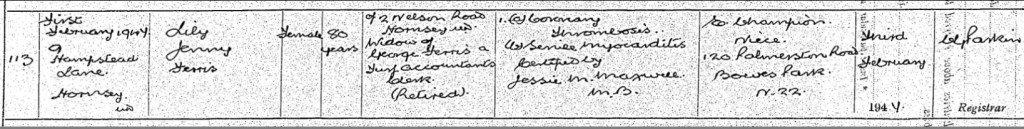

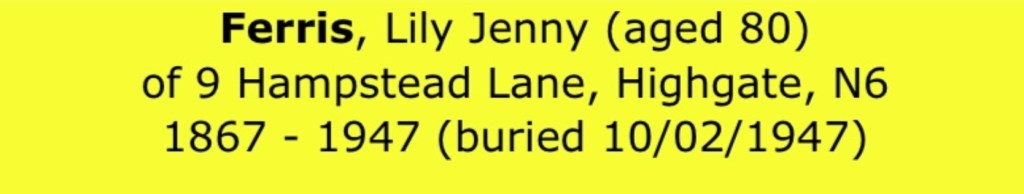

After years of hardship, Frederick’s sister, Lilly Jenny Neilson (née Willats), experienced a moment of profound joy and new beginnings. At 43 years old, Lilly had already faced immense personal struggles, having been left destitute by her first husband. So, when she married 41-year-old bachelor George Campbell Ferris on Saturday, October 23rd, 1915, it was a day of celebration and relief for her and her family. The wedding took place at the Register Office in Islington, London, a simple yet significant venue that marked the beginning of a new chapter in Lilly’s life.

For Lilly, this marriage was especially meaningful. After the loss of her first marriage and the challenging circumstances that followed, the union with George must have felt like a much-needed ray of hope. The joy of finding love again after so much struggle would have been a source of great happiness not just for Lilly but also for her family, who had seen her endure so many hardships. For Frederick, in particular, this was a moment to see his sister find happiness and security once again.

Lilly gave her address as 35 Yesbury Road, while George’s was 87 Winchester Street. His occupation was listed as a commercial clerk, and though this was not a glamorous title, it represented a stable livelihood. George’s father, George Coell Ferris, had been a commercial traveller, though he was now deceased. Lilly’s father, Richard Henry Willats, was an auctioneer, a profession passed down to Frederick. The family’s connection to these professions spoke to a strong work ethic and a sense of perseverance.

The witnesses to their union were Claude Eayes and J.E. Bailie, whose presence on this special day was surely a reminder of the close-knit network of friends and family who stood by Lilly. For Lilly, this marriage was not just the joining of two lives but the culmination of her resilience and the promise of a brighter future ahead. It was a joyous occasion for the Willats family, as they celebrated not only Lilly’s newfound happiness but the strength that had carried her through years of difficulty.

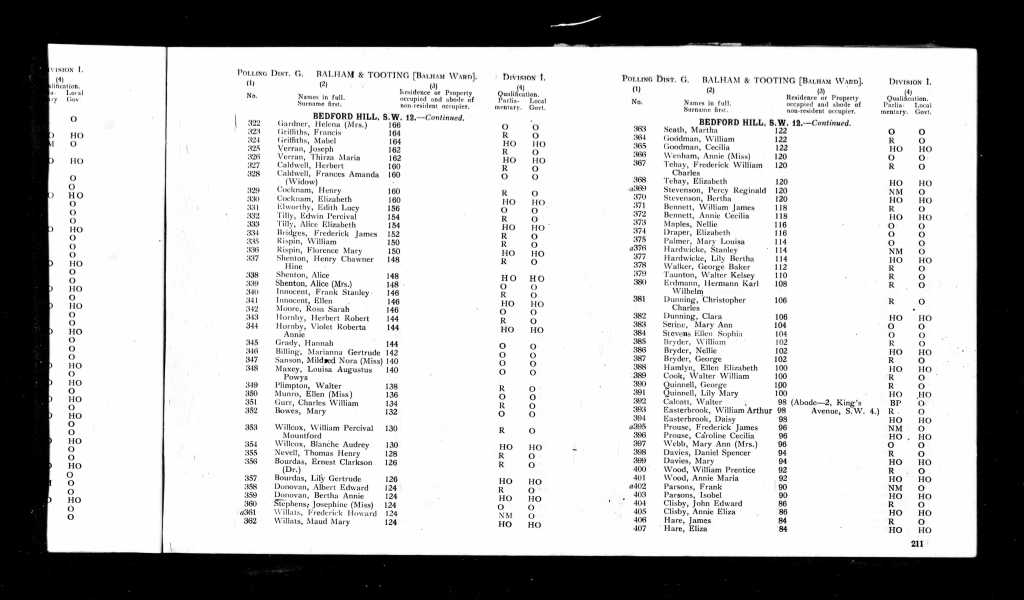

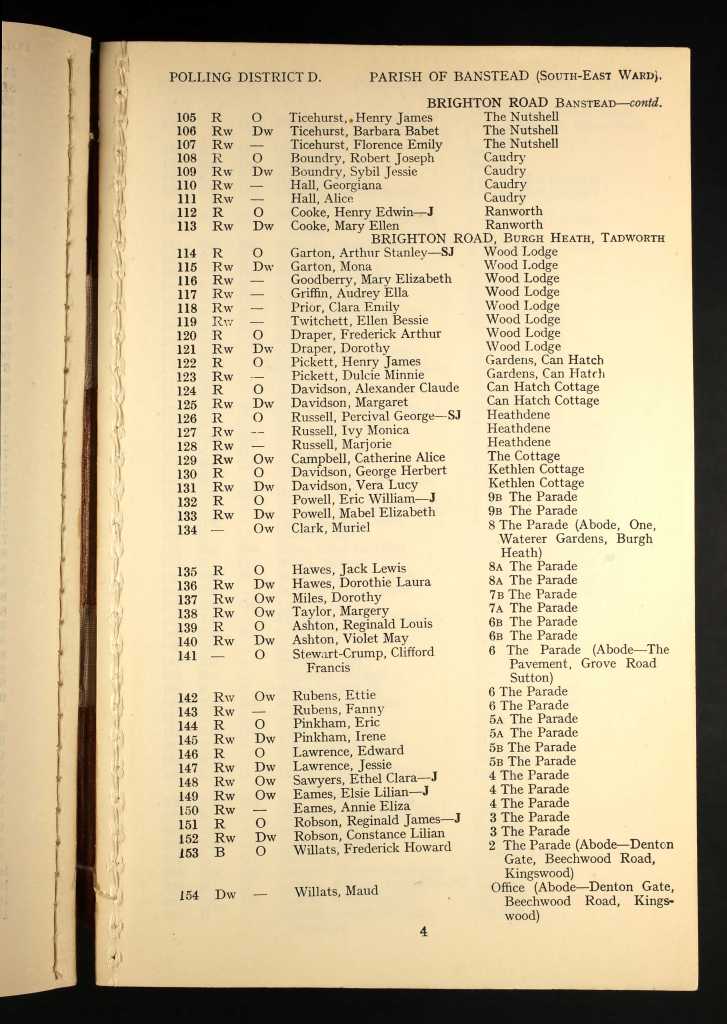

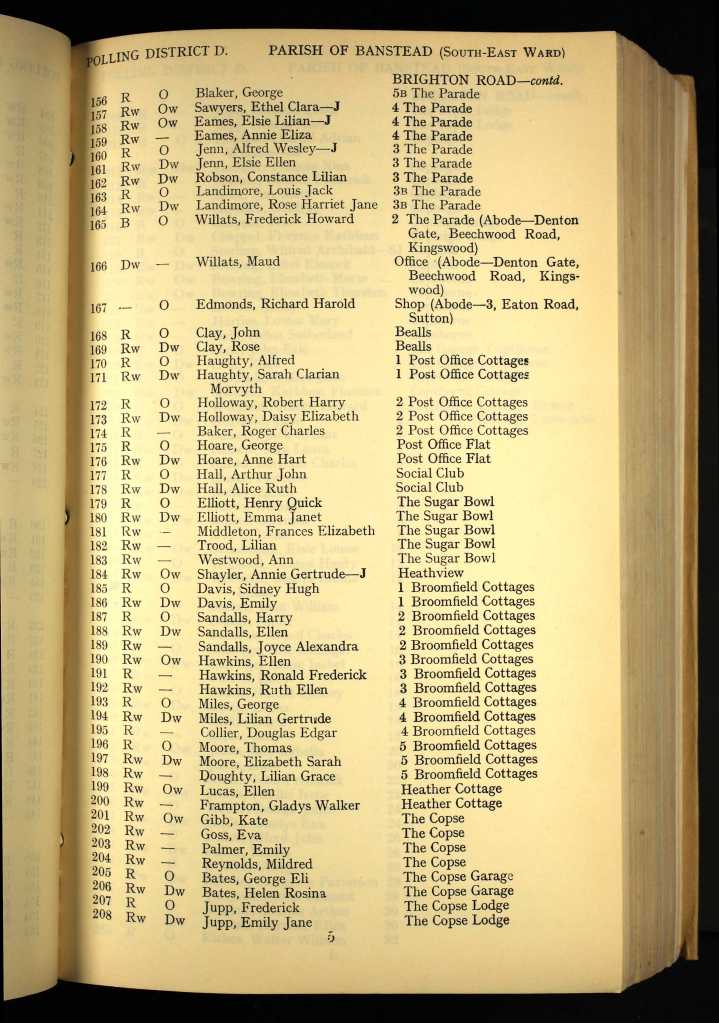

By 1918, Frederick and Maud had made another new home, this time at Number 124, Bedford Hill, in the bustling area of Wandsworth, Balham, London. The 1918 Electoral Register confirms that this was their residence during that year, marking another chapter in their journey together.

Moving to Bedford Hill must have been an exciting change for Frederick and Maud. Balham, a lively part of London, offered the couple and their growing family a fresh environment, perhaps with new opportunities and experiences. Frederick, continuing his work as a surveyor, and Maud, ever the heart of their home, had likely settled in this area hoping to provide their children with the best life possible.

As they settled into this new space, their home would have been filled with the sounds of life, children growing up, the familiar hum of domestic life, and the presence of family. The move to Bedford Hill was not just a geographical change but a new setting for their ongoing story, as they worked to build a stable and loving environment for their family during such a transformative period in history. It was a place where, no doubt, they made memories that would be cherished for years to come.

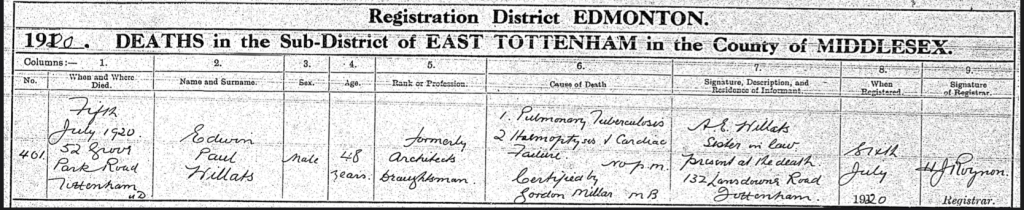

Two years after settling at Bedford Hill, the Willats family was struck by an unimaginable sorrow that would leave an indelible mark on their lives. Frederick’s brother, 48-year-old Edwin Paul Willats, an Architects Draftsman, passed away on Monday, July 5th, 1920. The grief that followed must have been profound for Frederick and all who loved Edwin, as his death at Number 52, Grove Park Road, Tottenham, Edmonton, was an overwhelming loss for the family.

Edwin had been battling pulmonary tuberculosis and hemoptysis cardiac failure, illnesses that would have caused him immense pain and suffering in the final months of his life. The slow decline, the quiet moments of uncertainty, and the painful struggle must have weighed heavily on him, and on his family, who watched helplessly as his health deteriorated. It’s heart-wrenching to think of the pain he endured, and equally sorrowful to imagine how his loved ones, particularly Frederick, must have felt, knowing that the brother he had shared so much with was slipping away.

Frederick’s sister-in-law, Amelia Ellen Willats (née High), of 132 Landsdowne Road, Tottenham, was with him in his final moments, providing what comfort and care she could during this difficult time. She was the one who had the painful responsibility of registering Edwin's death the following day, Tuesday, July 6th, 1920, in Edmonton. That act of registering his death, in the midst of the heartbreak, would have been a solemn reminder of the finality of it all.

For Frederick and his family, Edwin’s passing was only the beginning of a series of painful losses that would tear through them in the coming years. Each loss, like a heavy blow, would leave its mark, yet through it all, the Willats family would have had to summon the strength to carry on, despite the crushing grief. The pain of losing Edwin, a brother, a son, and an integral part of their lives, would forever change the family dynamic, and the scars from these losses would never fully fade.

But even in the midst of such overwhelming sorrow, it is clear that the Willats family, like so many who came before and after, found ways to endure. The love they shared, the memories of better days, and the unspoken bond between them would, perhaps, provide some solace in the darkest moments. Their strength through such hardship is a testament to their resilience, and a reminder that, even in the deepest pain, the ties of family can help carry them through.

Pulmonary tuberculosis (TB) and hemoptysis due to cardiac failure are two significant health concerns that, though distinct, can sometimes be related in the context of a patient’s overall health. These conditions each have their own complex histories and pathophysiologies, but they also occasionally intersect when one exacerbates the other.

Pulmonary tuberculosis is a contagious bacterial infection primarily affecting the lungs, though it can spread to other parts of the body. It is caused by *Mycobacterium tuberculosis*, a slow-growing bacterium that can persist in the body for years, often in a latent form. The history of tuberculosis dates back centuries, with references to a disease resembling TB found in ancient Egyptian mummies, and it was known in the 19th century as "consumption" due to the weight loss and wasting it caused in those affected. The understanding of tuberculosis began to improve in the late 19th century, particularly after the identification of *Mycobacterium tuberculosis* by Robert Koch in 1882. His discovery led to a revolution in the diagnosis and treatment of the disease. Despite this breakthrough, TB remained a global health threat, especially in the 20th century, due to overcrowding, poor living conditions, and the advent of antibiotic-resistant strains.

The main symptoms of pulmonary tuberculosis include a persistent cough, chest pain, night sweats, fever, weight loss, and fatigue. In some cases, people with advanced pulmonary TB may experience hemoptysis, which is the coughing up of blood. This occurs because the infection damages lung tissue, causing blood vessels in the lungs to rupture. Hemoptysis is a serious complication and is often a sign that the disease has progressed significantly, possibly leading to the need for more aggressive treatments like surgery or a prolonged course of antibiotics. The treatment of TB typically involves a combination of antibiotics, such as isoniazid, rifampin, and pyrazinamide, over several months, and the advent of drug-resistant strains has created new challenges for TB management.

Hemoptysis is also a key symptom that can arise in various conditions beyond tuberculosis, and its relationship with cardiac failure is an important one. Cardiac failure, particularly left-sided heart failure, can lead to a backup of blood in the pulmonary circulation, resulting in increased pressure in the blood vessels of the lungs. This increased pressure can cause the fragile vessels in the lungs to burst, leading to blood in the airways, which is then coughed up as hemoptysis. In cases of congestive heart failure, the heart’s inability to pump blood effectively causes fluid to accumulate in the lungs, leading to pulmonary edema, a condition that can also result in hemoptysis.

The historical understanding of heart failure dates back to the early days of medicine, but it wasn’t until the 19th century that the mechanistic understanding of cardiac failure began to evolve. The term "heart failure" was first used in the medical literature in the early 1800s, but the pathophysiology was largely unknown until the 20th century. In the 20th century, especially after the advent of modern diagnostic technologies such as echocardiography and chest X-rays, it became clearer how heart failure could lead to fluid buildup in the lungs, and ultimately to symptoms like shortness of breath and hemoptysis.

While TB and heart failure are separate conditions, the coexistence of both in a single patient can significantly complicate diagnosis and treatment. In regions with high TB prevalence, chronic cardiac failure may be exacerbated by TB-related damage to the lungs or vice versa. For example, a patient with active TB who also has left-sided heart failure may face an increased risk of hemoptysis as a complication of both conditions. The overlap of these two diseases makes management more challenging, as treatment for heart failure may exacerbate the progression of tuberculosis, while anti-TB treatments can have cardiovascular side effects.

In terms of treatment, managing a patient with both pulmonary tuberculosis and cardiac failure requires a careful, multidisciplinary approach. Treatment for TB typically involves a prolonged course of antibiotics, and for heart failure, medications like diuretics, beta-blockers, and ACE inhibitors are often used to reduce fluid buildup and help the heart pump more effectively. The simultaneous management of both conditions requires close monitoring, as certain drugs used for TB treatment can interact with heart failure medications, and the effects of one disease can influence the other. Hemoptysis in this context often signals a worsening of either the pulmonary tuberculosis or the heart failure and may necessitate emergency intervention, such as the use of vasodilators, respiratory support, or, in severe cases, surgical interventions.

The history of both diseases reflects the progress made in understanding their underlying mechanisms and treatment strategies, though both remain global health issues. Tuberculosis continues to be a major concern in many parts of the world, particularly in low-income countries where it remains the leading cause of death from a single infectious agent. Cardiac failure, on the other hand, is increasingly common in high-income countries, where lifestyle factors like diet and exercise, as well as an aging population, contribute to its prevalence. The intersection of these two diseases represents a significant challenge in modern medicine, requiring integrated care to optimize patient outcomes.

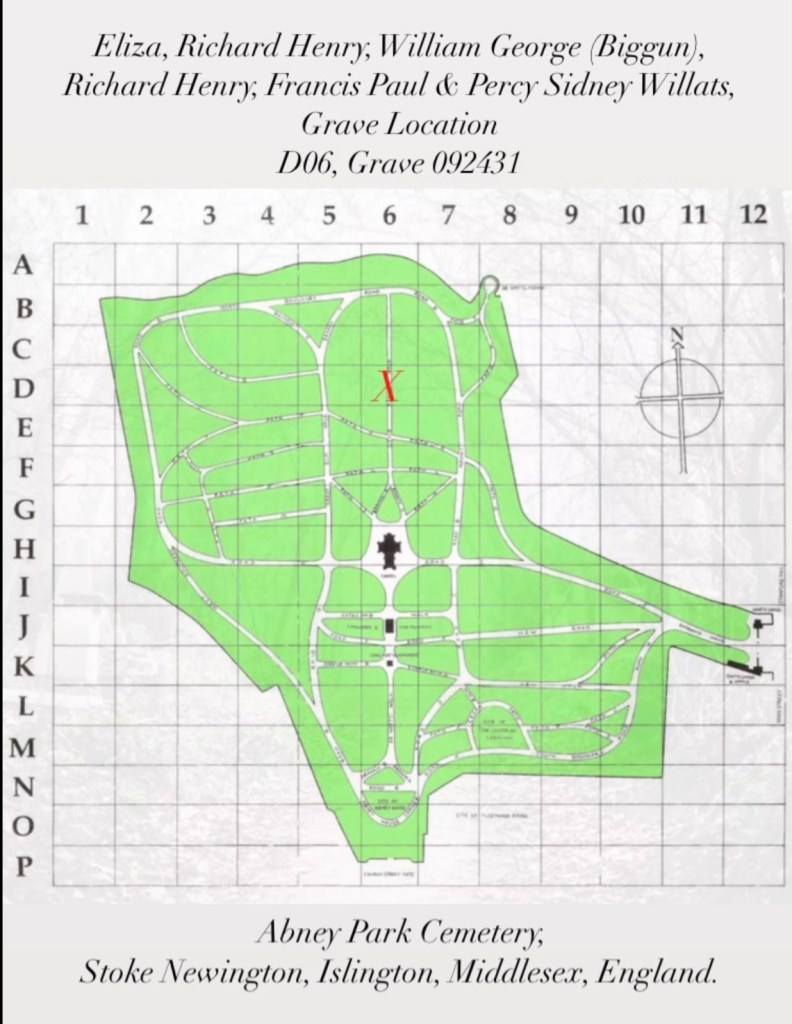

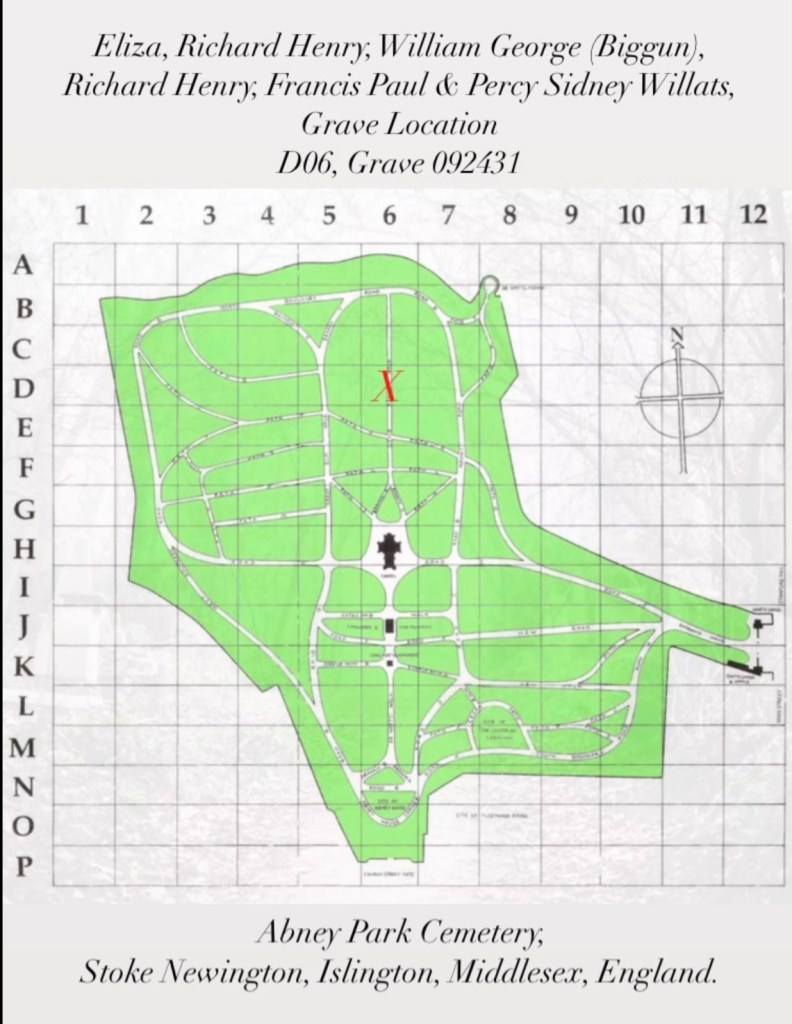

On a somber Saturday, the 10th day of July, 1920, the Willats family and their close friends gathered to lay Edwin Paul Willats to rest at Abney Park Cemetery in Stoke Newington, Hackney. The pain of saying goodbye was immense, as they stood together in grief, but also in love, honoring Edwin’s life and the memories he had left behind. He was laid to rest in Section D06, Index 7S03, a place where he would be remembered forever.

In a quiet, heart-wrenching act of finality, Edwin was buried alongside those who had gone before and after him, his young family members, including Baby Willats, little Daisy Jean Maria, Constance Margaret Thora, and Sophia Ann Willats, as well as Edward Charlton. The cemetery, a peaceful resting place, now held the remains of loved ones who had been taken too soon, each with their own untold stories. The family, who had already faced so much loss, could only find solace in the thought that they were reunited in one place, where the grief of this world could no longer reach them.

For those who mourned Edwin’s passing, the act of laying him to rest was not just an end but a deeply emotional acknowledgment of all the love, memories, and heartbreak that had shaped his life. The pain was undoubtedly overwhelming, as they said their final goodbyes, but they also carried with them the hope that Edwin, like the others he now lay with, would be at peace.

The Willats family was once again struck by devastating sorrow, this time with the loss of Frederick’s brother, 63-year-old Francis Montague Allan Willats. On Sunday, September 19th, 1920, Francis passed away at his home in Wymondley Heathgate, Hendon, Middlesex. The pain of his passing must have been particularly hard for the family, as they had already endured so much grief in the preceding months.

Francis had been battling chronic interstitial hepatitis for several years, a condition that would have caused him ongoing discomfort and, ultimately, led to his decline. Though the illness had been a long, silent struggle, the family could only watch as it slowly took its toll, knowing how much it must have weighed on Francis. The loss of him, after such a long and painful battle, was not just the death of a beloved brother, father, and husband, but a heavy moment of finality for those who loved him.

In his final moments, Francis was surrounded by his family, and his son, Allen Montague Willats, was there to witness his passing. It was Allen who had the difficult and heartbreaking task of registering his father's death on Tuesday, September 22nd, 1920, in Hendon. No doubt, Allen was filled with sorrow, not only for the loss of his father but for the weight of having to take on the responsibility of documenting this painful end.

For Frederick and the entire Willats family, Francis’ death was another wound in a period already scarred by grief. Each loss was felt deeply, leaving an aching void that no words could fill. And yet, in their pain, they continued to carry forward the love and memories of those who had gone before them. The Willats family, bound by both love and sorrow, would have held on to each other in the face of these heartbreaking times, finding strength in their shared grief and the enduring bonds of family.

On Tuesday, 21st of September, 1920, the Willats family gathered in quiet sorrow to lay to rest Frederick’s brother, Francis Montague Allan Willats. The grief they felt must have been profound as they said their final goodbye to a beloved family member, knowing the pain of loss all too well by that point. Francis was laid to rest at Highgate Cemetery in Camden, London, a peaceful resting place where so many of their loved ones had found their final home. His grave, marked with the reference /40479, would become a solemn place for reflection, where family and friends could remember the man they had lost.

Francis was not buried alone. His resting place was shared with the remains of several other dearly loved family members: Frances Jessie Willats, Allan Montague Willats, Dorothy Beaumont Willats, Margaret Eliza Craddock, David Allan Willats, and Margaret Jane Willats. There, too, was the grave of War Hero Horace Lennan Willats, who had served with valor. These names, each one a beloved member of the family, rested side by side in a final act of unity, as if to offer a sense of comfort in knowing that those who had passed before would not be alone.

The pain of losing Francis must have been unbearable, but as they stood at the graveside, perhaps there was some solace in knowing that he was surrounded by family, those who had gone before him, and those who would continue to carry his memory forward. The cemetery, with its quiet beauty, was a place where grief could be shared, where the family could gather to mourn, but also to honor the legacy of a life well lived. It was a moment of profound loss, but also a reminder of the deep connections that bound them, even in death.

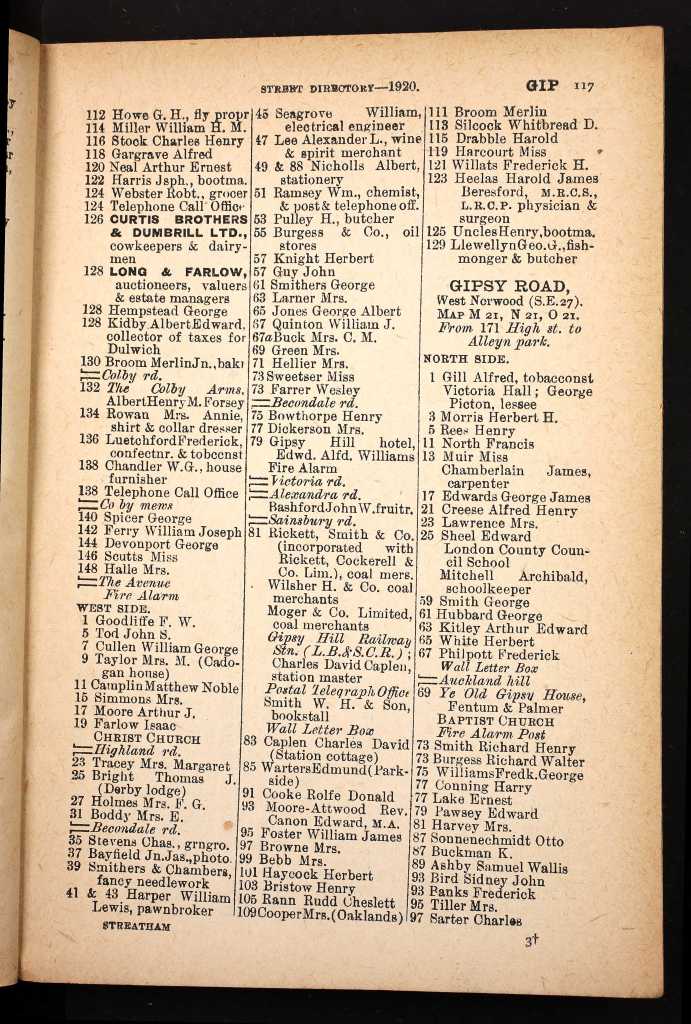

In 1920, Frederick and his family were living at Number 121 Gipsy Road in the Norwood area of Lambeth, London. The City Directory from that time confirms this address, marking another chapter in their life. Gipsy Road, with its quiet residential charm, would have offered the family a fresh space to settle into, as Frederick continued his work as a surveyor.

For Frederick, this move to Norwood might have represented a new beginning, perhaps a chance to put down roots in a vibrant part of London. The area was a mix of suburban peace and access to the bustling heart of the city, giving the family a balance of both worlds. Living in a community that offered both tranquility and convenience, the home at Number 121 would have become a place where Frederick, Maud, and their children could continue to build their lives together, surrounded by the familiar sounds of the city and the comfort of family.

Though the years had already been marked by hardship, the family’s resilience was evident as they carried on, making their home in Norwood with the same strength and determination that had always guided them. For Frederick, Gipsy Road was not just an address, but a place where his family could grow, heal, and look toward the future.

The 1920 London, England, Electoral Register, also confirms, Fredrick and Maud, were residing at, Number 121 Gipsy Road, Norwood, Lambeth, London , England, in 1920.

Gipsy Road, located in the Norwood area of Lambeth, London, has a rich and varied history. It runs through the southern part of Lambeth, an area that has evolved over centuries from rural farmland to the bustling, residential urban neighborhood it is today. The road itself is part of a broader history that intertwines with the development of Lambeth and the larger South London area.

Historically, Lambeth was a parish in the county of Surrey, before it was absorbed into Greater London in the late 19th century. During the 18th and 19th centuries, the area saw a significant transformation, especially with the arrival of the railways in the mid-19th century, which spurred rapid urban development. Prior to this, parts of what is now Norwood, including areas around Gipsy Road, were more rural in nature, characterized by open fields and countryside. The advent of industrialization, however, brought increased demand for housing and infrastructure, changing the landscape dramatically.

The name "Gipsy Road" itself may stem from the road's historical association with travelers or Romani people, a group sometimes referred to as "gypsies" in common parlance. However, it is important to note that the exact origin of the name is not definitively recorded, and like many roads in London, it could simply be a reflection of local usage or a descriptor of the people who lived or passed through the area at the time.

By the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Gipsy Road had become part of the urban fabric of Norwood, which was in the process of being developed into a more established residential area. The construction of homes in this part of South London catered to the middle classes, and streets like Gipsy Road were lined with terraced houses, with an increasing number of shops, businesses, and schools springing up to serve the growing population.

In the 1920s, when Frederick and his family lived on Gipsy Road, the area was part of a post-Victorian expansion, and the local architecture likely reflected the era’s desire for practicality and space. The road was well-connected to the rest of London, with easy access to transport links, allowing people like Frederick, who worked as a surveyor, to live in relative comfort while still commuting into central London for work.

Over the years, the character of Gipsy Road has evolved along with its surrounding area. Today, it remains a significant part of the Norwood area, a mixture of residential properties, schools, and small businesses. While the area has modernized, the history of Gipsy Road and its role in the development of Lambeth and South London is still reflected in the many homes and buildings that line its streets.

Living on Gipsy Road in 1920 would have meant being part of a dynamic and changing community, one that was beginning to embrace the conveniences of modern life while still holding onto remnants of its more rural past. For Frederick and his family, it would have been a place of both opportunity and belonging, where they could continue to build their lives amidst the vibrant changes happening around them.

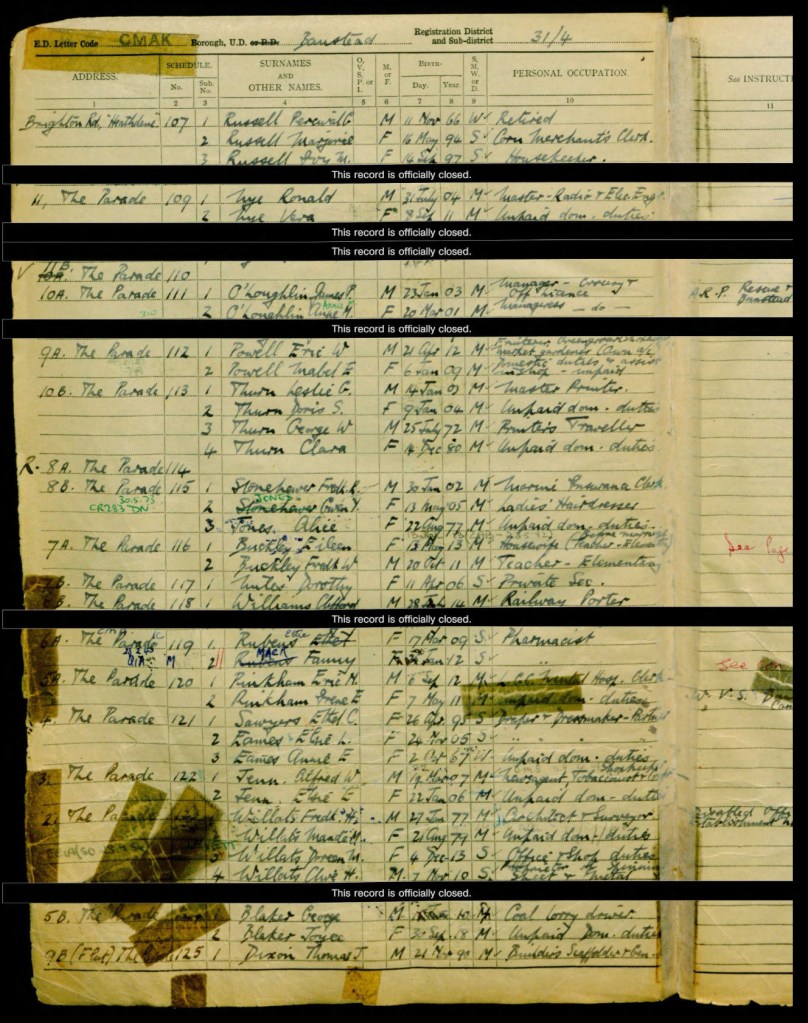

On Sunday, the 19th day of June, 1921, the Willats family was counted in the 1921 census, a snapshot of their lives during a time of both change and quiet stability. At that moment, Frederick and his wife Maud, along with their three children, Gladys, Claud, and Doreen, and Frederick’s sister Edith Cameron Charlton (née Willats), were living at Winton, a modest five-room dwelling located on Gordon Avenue in the coastal town of Bognor, Sussex.

The home at Winton would have been filled with the sounds of everyday life: the laughter and energy of the children, the hum of Maud’s steady care, and the quiet presence of Edith, Frederick’s sister, who at the time was not employed. The family, though far from their previous London homes, found a place in this tranquil town by the sea, embracing the slower pace of life that Bognor offered.

Frederick, ever the dedicated professional, worked as an architectural surveyor. Though he had no fixed place of work, his role as an employer marked him as a man of responsibility, providing for his family while navigating a career that likely required travel and flexibility. The census also noted that he had two minor dependents, his children, whom he cared for deeply and whom he and Maud worked tirelessly to raise.

Maud, like so many mothers of the time, dedicated herself fully to her home and family, managing the household duties with grace and care. Her work as a housewife was no less demanding, creating a warm and nurturing environment for her children and welcoming Frederick’s sister Edith into their home.

Gladys, Claud, and Doreen, the bright young scholars of the family, were all attending school, their futures ahead of them, filled with promise. The quiet pride that Frederick and Maud must have felt for their children’s education would have been immeasurable, as they were no doubt eager to see the children thrive in the world they were shaping for them.

In their small, five-room home at Winton, the Willats family found a new rhythm of life. Though separated from the bustle of London, they were connected by the bonds of family, their love and care for one another providing strength and support through every change.

The UK 1921 census was a significant milestone in the history of census-taking in the United Kingdom. Conducted on the night of April 19th, 1921, it was the first national census after the First World War and provided crucial insights into the population and social structure of the country during a period of significant change.

Unlike previous censuses, which were traditionally conducted every ten years, the 1921 census was unique because it was the only census between 1911 and 1951 due to the disruption caused by World War I and its aftermath. As a result, it captured a snapshot of British society in the aftermath of a global conflict and during a period of social and economic transformation.

The census collected a wide range of information about individuals and households across England, Wales, Scotland, and Ireland (which was part of the UK at the time). This included demographic data such as age, sex, marital status, occupation, and place of birth, as well as details about housing conditions and amenities.

One notable aspect of the 1921 census was the introduction of a separate schedule for military personnel stationed overseas, reflecting the significant role of the British Empire in World War I and its aftermath.

The data collected in the census was used for various purposes, including government planning, social policy development, and historical research. It provided valuable insights into population trends, urbanization, industrialization, and changes in family structure and household composition.

Access to the 1921 census records was restricted for several decades due to privacy concerns, but in January 2022, the records were released to the public by The National Archives in England and Wales, the National Records of Scotland, and the Public Record Office of Northern Ireland. This historic release allowed researchers, genealogists, and historians to delve into the rich trove of data and gain a deeper understanding of life in the UK during the early 20th century.

On Monday, the 27th day of November, 1922, Frederick's brother, 67-year-old Henry Richard Willats, passed away at his home on 23 Barnmead Road in Beckenham, Bromley, Kent. His death, after a prolonged illness, was the result of chronic nephritis, which had affected him for ten long years, compounded by the recent onset of cardiac failure in the final months. For Frederick and his family, the loss of Henry must have been a profound sorrow, as they had witnessed his gradual decline and endured the pain of knowing the end was near.

Henry, once a respected director of limited companies, had spent much of his life immersed in business and family, and his passing marked the end of a significant chapter in the Willats family’s story. For his loved ones, particularly Frederick, the grief was no doubt compounded by the years of his brother’s illness, which had slowly stolen the vitality from the man they once knew.

Walter James Willats, another of Frederick’s brothers, was present at the time of Henry’s passing. Walter, who had lived on Lansdowne Road in London, took on the difficult task of registering Henry’s death in Bromley, on the very same day as his brother’s passing. The fact that Walter was there, at his brother’s side during those final moments, is a poignant reminder of the bonds that held the Willats family together, despite the heartache and distance that life often placed between them.

Henry’s death, though expected, left an emptiness that would be felt deeply by his family. It was not just the loss of a brother, but the closing of a long chapter of shared experiences and memories. For Frederick, the weight of grief would have been heavy, as he mourned not only his brother but the man he had once known, whose presence had shaped their lives in ways that were now fading into memory. And yet, in this sorrow, there must have been comfort in the thought that Henry was finally at rest, free from the years of illness that had weighed so heavily on him.

On Friday, the 1st day of December, 1922, the Willats family came together in quiet sorrow to lay to rest their beloved Henry Richard Willats. At Abney Park Cemetery, a place of peace and reflection, they gathered to honor his life, surrounded by the history of their family. It was a deeply emotional moment for all who knew him, one that marked the end of Henry's journey and the beginning of his eternal rest.

His final resting place, within the family grave, symbolized not only his connection to the Willats family but also the many loved ones who had gone before him. Buried alongside Henry were others who had been cherished members of the family: Baby Thornton, Florence Jose Western (née Willats), the brave War Hero Harry Ashley Willats, William Western Thornton, and Amelia Willats. Each name, each life, represented a bond that could not be severed by time or death.

As they lowered Henry into the earth, the family was no doubt comforted by the thought that he would rest forever in the company of those who had loved him. This shared grave, filled with so many of their family members, would serve as a lasting reminder of their enduring connection, a place where their memories, love, and grief could all be held together, where the past and present met in quiet tribute.

For Frederick and his family, this day was not just about loss; it was also a testament to the strength of their ties, a reminder that even in death, they would never be truly separated from the ones they loved. The cemetery, though a place of sadness, also held the beauty of legacy, where each life, no matter how short or long, continued to live on in the hearts of those who remained.

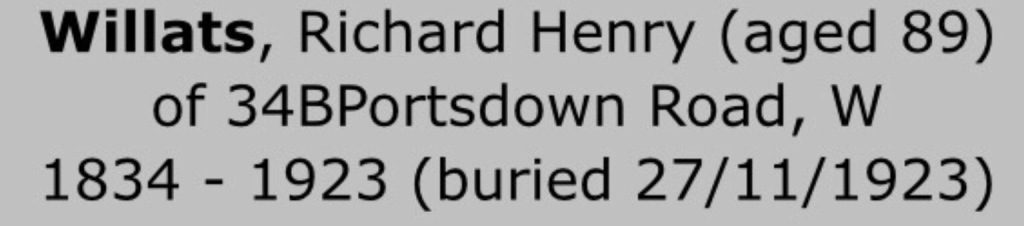

It is with profound sadness that we remember the passing of Frederick’s beloved father, Richard Henry Willats, who left this world on Thursday, the 22nd day of November, 1923, at the age of 89. Richard’s life, long and full of history, came to its natural close after a struggle with bronchitis and the frailty brought on by senility, the inevitable decline that often accompanies old age. Though his body grew weaker, the wisdom and experience he had carried throughout his years remained a lasting imprint on all who knew him.

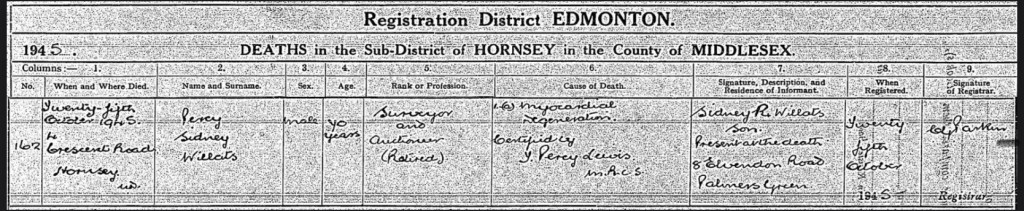

Richard passed away at 34B Portsdown Road, Paddington, London, surrounded by the inevitable quiet of old age. His son Percy Sidney Willats, who had been there by his father’s side, was the one to register Richard’s death on Saturday, the 24th day of November, 1923. Percy, always dutiful and devoted, recorded the loss of his father, noting Richard’s occupation as a retired auctioneer and surveyor. This simple line in the official record, however, could not capture the depth of Richard’s legacy, a man who had contributed so much to his family and to his profession.

For Frederick, this loss was likely an especially painful one. Losing a father is always an aching sorrow, even when death is anticipated in old age. Yet, for all the years they had together, the finality of Richard’s passing would have brought a quiet grief, one felt deeply by his children. The death of a patriarch is a heavy moment in a family’s history, and Frederick would have mourned not just the loss of a father, but the loss of the figure who had shaped his own life and guided the family through the years.

Though Richard’s passing marked the end of a life well-lived, his memory would live on in his children, in the stories they would share of him, and in the values he passed on. And while the sadness of his death hung heavy over his family, there was also a sense of peace in knowing that Richard had lived a full life and was now at rest, free from the frailty that old age had brought.

With heavy hearts, the remaining members of the Willats family gathered together to lay their cherished father, Richard Henry Willats, to rest on Tuesday, the 27th day of November, 1923. He was buried at Abney Park Cemetery, a peaceful resting place in Stoke Newington, London, where his story, and the story of his family, would continue even in death.

Richard was laid to rest in grave number 092431, in Plot D06, beside his beloved wife, Eliza Willats (née Cameron), who had passed before him, and later their sons, Francis Paul Willats and Percy Sidney Willats. Also laid to rest alongside him was his stepson and nephew, William George Willats—each one a vital part of the family’s enduring history.

The decision to place Richard in this shared family grave was deeply symbolic. The plot had originally been purchased by Richard himself after the death of his wife, Eliza. In a way, Richard had already ensured that, when his time came, he would be reunited with those he had loved most dearly. The family grave, once a solemn reminder of loss, had become a symbol of love and continuity, a place where the bonds of family transcended time and the pain of separation was softened by the knowledge that they would be together once more.

As the Willats family stood together at that gravesite, there most have been a sense of bittersweet comfort, knowing that Richard, Eliza, and along with William, were now reunited in eternal rest. Their love story, though it had been interrupted by life’s inevitable hardships and separations, was now able to continue in the afterlife, a love that would never fade, even in death. This final resting place, shared by so many generations, became a testament to the enduring nature of family, love, and the unbreakable ties that bind us, even beyond the physical world.

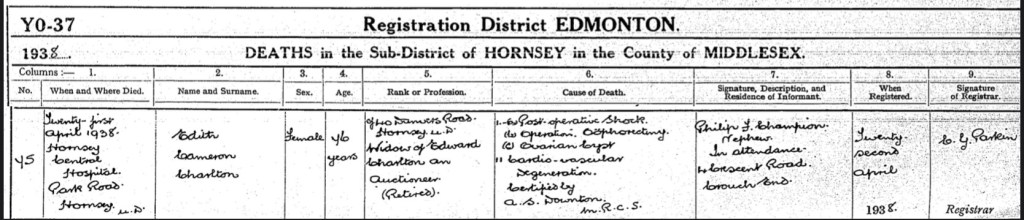

The Willats family was once again struck by the deep sorrow of loss when Frederick’s sister, Charlotte Ellen Crosbie (née Willats), passed away on Saturday, the 5th day of April, 1924, at the age of 64. Charlotte, who had been a widow since the death of her husband, medical student Pierce William Crosbie, had lived through much hardship. Her death, caused by cardiac disease (mitral) and hemiplegia, marked the end of a life that had already known its share of trials and suffering.

Charlotte’s passing, at her home on Number 34 Portsdown Road, Paddington, was a quiet, somber moment for the family. For those who loved her, particularly her sister Edith Cameron Charlton (née Willats), the pain of her loss must have been overwhelming. Edith, who was present at her sister’s side in her final moments, took on the difficult responsibility of registering Charlotte’s death on Monday, the 7th of April, 1924. The act of registering Charlotte’s death was not just an administrative task, but a final step in acknowledging the end of her earthly journey, one that had been marked by both quiet courage and unspoken suffering.

For Frederick, the loss of another sister must have been a particularly painful blow. With each death that came in the family, the weight of grief grew heavier, and the family seemed to be drawn further into a period of unrelenting sorrow. Charlotte’s passing would have left a void, not just in the immediate family, but in the hearts of all who knew her, a woman who had lived through so much, yet had never lost her strength.

The Willats family, who had already endured so much loss, now faced another chapter of mourning. And while Charlotte’s death was another heavy moment in their shared history, it was also a reminder of the love that had bound them all together, and the memories that would live on in the hearts of those she left behind. As they mourned her passing, they would also remember her life, a life of resilience, of love, and of the indelible mark she had left on her family.

Charlotte's life story is truly fascinating. If you're interested in learning more, you can explore the details I've uncovered through documentation in the Willats section of Intwined.

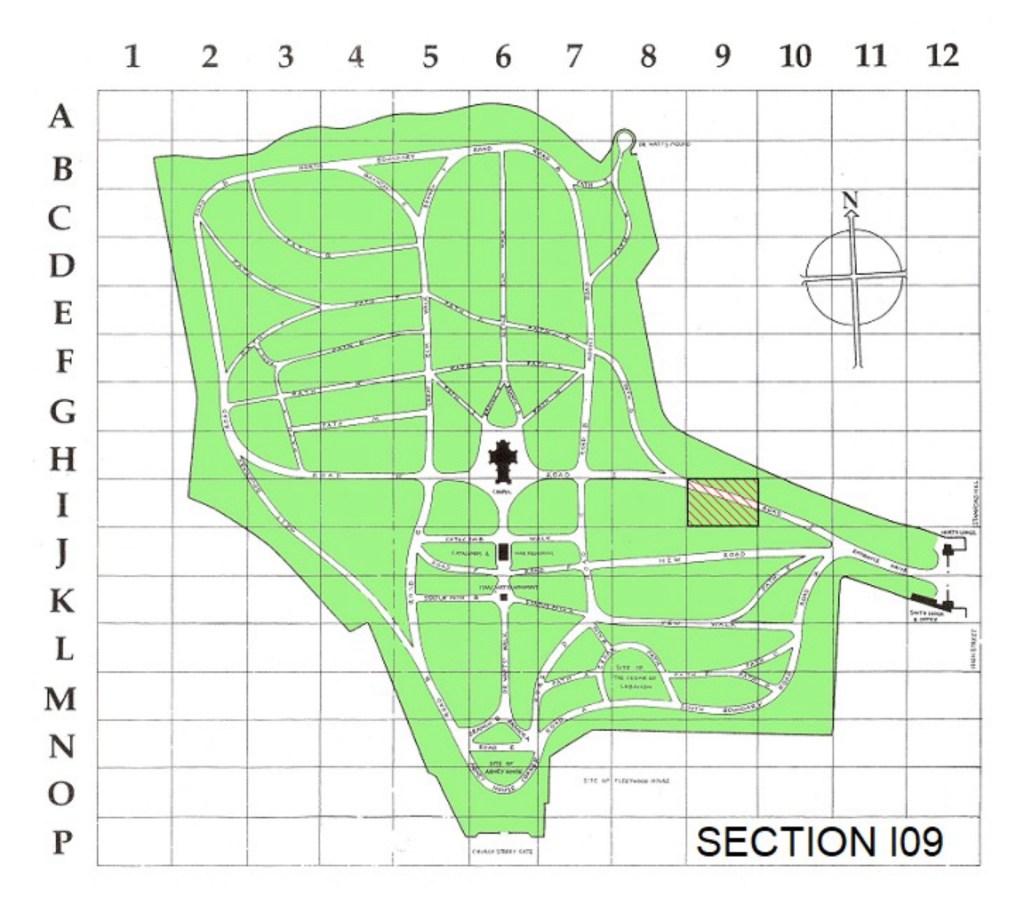

On Wednesday, the 9th day of April, 1924, Charlotte Ellen Crosbie was laid to rest by her siblings in the peaceful surroundings of Abney Park Cemetery, 215 Stoke Newington High Street, Stoke Newington, London, England. Her final resting place, in grave 127434 (possibly renumbered to 17434, with the grave reference Sec. I09, Index 7S08), became a place where the love and memory of Charlotte would endure, alongside those who had passed before her.

Charlotte’s family, though heartbroken, took comfort in the thought that she would be reunited in the afterlife with other loved ones, those who had already left the world too soon. Alongside her in this shared family grave lay Baby Crosbie, Amina Eliza Kathleen Reichert (née Charlton), Mabel Cameron Woollett Willats, and Eliza Smith, Charlotte's dear companion. These individuals, too, were beloved members of the family, whose lives, though brief or quiet, had left an indelible mark on the hearts of those who knew them.

For Charlotte’s siblings, this moment would have been deeply emotional. The pain of burying yet another sister, so full of life and spirit, was made all the more poignant by the shared sense of loss that accompanied her passing. As they stood at the graveside, they would have reflected on the bonds of love that tied their family together, a love that even death could not sever.

Though the grief of her loss weighed heavily on them, the family would also have been comforted by the thought that Charlotte, now resting beside those she had loved, would forever be part of their family’s story. The cemetery, a place of sorrow, was also a place of memory, where the lives of the departed were honored and cherished, and where love transcended the physical world. And so, Charlotte’s memory would live on, carried in the hearts of those who had known her, and in the lasting legacy of family, love, and remembrance.

In 1924, Frederick and Maud (listed as Mary Maud) were living in the peaceful town of Horley, Surrey, at a place called Mayfair, Mason Bridge Road. This was a significant chapter for the family, as they settled in an area that offered a quieter pace of life compared to the bustling streets of London. Horley, located to the south of towns like Reigate and Redhill, sat on the border with West Sussex, close to the thriving town of Crawley and the ever-growing Gatwick Airport.

For Frederick and Maud, Horley would have been a place of both peace and opportunity. The town had its own small economy, with business parks, a shopping center, and a long high street, making it a practical choice for those looking to balance suburban tranquillity with access to necessary amenities. And while the pace of life in Horley was slower, it didn’t lack in connectivity. The town was well-served by both rail and bus services, making commuting to London and other nearby towns relatively easy.

For Maud, who had spent much of her life in busy urban settings, moving to Horley must have been a welcome change. It was a place where she could enjoy the quiet of the countryside, yet still remain closely connected to the outside world. As for Frederick, it would have been a place that suited his work and offered a more relaxed environment for his family to grow and thrive.

This new chapter in Horley would have been bittersweet, as it marked a time of settling into a new life while, no doubt, holding onto the memories and legacies of the past. It was a place of fresh beginnings for Frederick and Maud, a place where they could continue to build their lives together, with their children and family by their side, creating new memories in a town that connected them to the wider world while offering them a sense of peace.

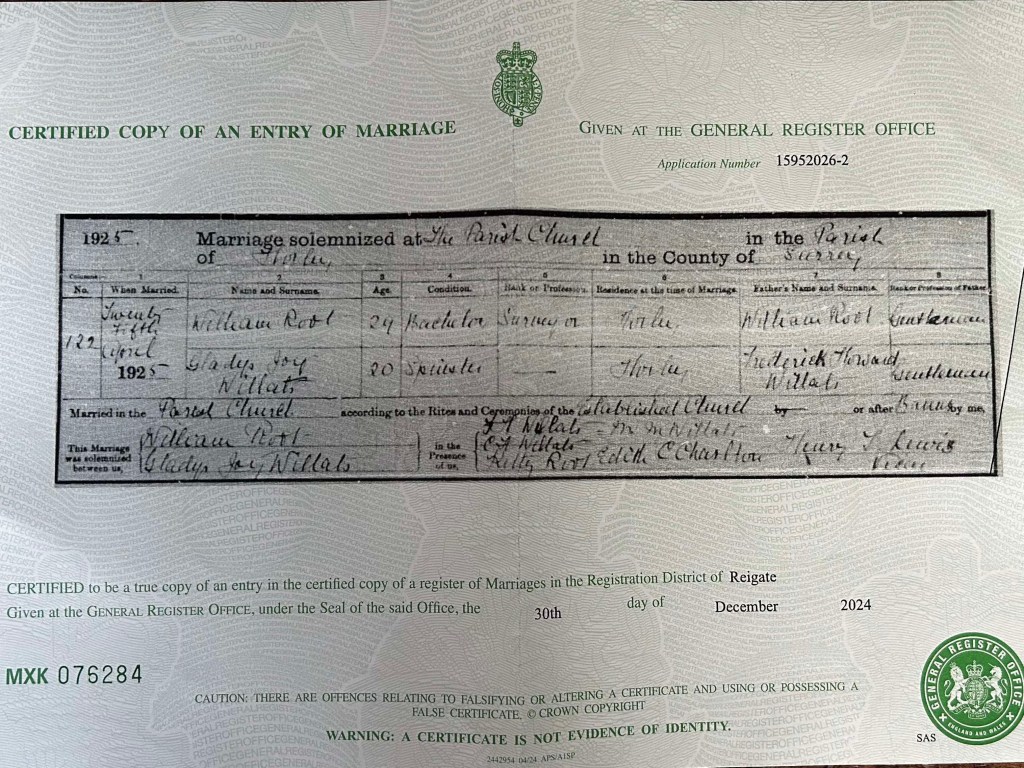

Frederick and Maud’s hearts must have been brimming with love and pride on the 25th day of April 1925, when their 20-year-old daughter, Gladys Joy Willats, stood before family and friends to exchange vows with 29-year-old William Root, a man of courage and resilience. The ceremony took place in the parish church of Horley, St. Bartholomew’s, Horley,Surrey, England, a setting steeped in timeless beauty and tranquility that perfectly mirrored the significance of the day.

For Frederick, watching his beloved Gladys step into this new chapter must have been both joyous and poignant. She had grown from the little girl he had guided and protected into a young woman of grace and determination, ready to embark on her journey with William. Standing as a witness to her commitment, alongside her brother Clyde Howard Willats and her mother Maud Mary Willats, Frederick's presence was more than symbolic, it was an affirmation of his unwavering support and love for his daughter as she began this new phase of her life.

The wedding was a true family affair, with witnesses including Gladys’s paternal aunt, Edith C. Charlton, and William’s sister, Katy Root. It must have been deeply meaningful for both families to come together, affirming the bond not just between Gladys and William but also between their respective families.

The couple’s union was blessed by the love and prayers of those closest to them and was officiated by Rev. Henry Lewis. The details, like their shared abode in Horley and the honorable professions of their fathers, Frederick Howard Willats as a gentleman and William Root as a gentleman, spoke to the respectability and grounding of both families.

As Gladys and William exchanged vows, Frederick likely felt a swell of gratitude, knowing his daughter had found a partner to cherish and support her. And while there may have been a bittersweet moment of realization that his little girl was now creating a home of her own, this would have been outweighed by the joy of seeing her surrounded by love and embarking on a life full of promise and shared dreams.

Frederick’s role as a witness to Gladys’s wedding was not just about signing a document, it was a reflection of his enduring presence in her life, standing by her side as she took one of life’s most significant steps. The day must have been filled with tender moments, laughter, and the deep, abiding love of family, a day that Frederick and all who attended would remember with great fondness and joy for years to come.

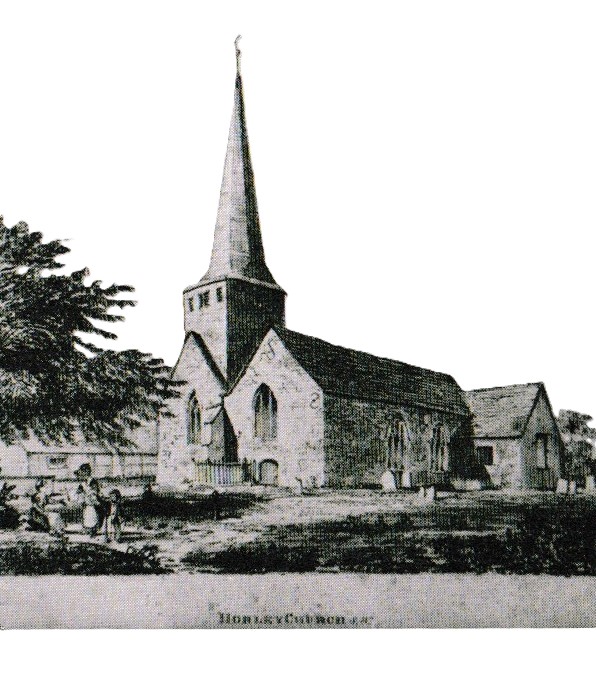

St. Bartholomew's Church, affectionately known as St. Bart's, serves as the Parish Church of Horley, Surrey. The church's origins trace back to the mid-12th century, with the earliest known rector, Walter, recorded in 1218. Originally dedicated to a different patron, the church was rededicated to St. Bartholomew in 1565.

The current structure predominantly dates from the 14th century, featuring a narrow wood-shingled bell turret and spire. Significant restorations were undertaken in 1881–82 by architect A.W. Blomfield, and a south aisle was added in 1900. Further modifications in 1991 introduced upper rooms adjacent to the bell tower, enhancing the church's facilities.

A notable interior feature is the life-size Reigate stone effigy of a knight, believed to be Sir Roger Salaman, dating from around 1315. This effigy is significant for depicting the transitional period in knightly armor from mail to plate.

The church's organ, constructed by Bishop and Son of London in the late 19th century, was originally a single-keyboard instrument located in the gallery at the back of the North Aisle. It was expanded to two keyboards following the addition of the South Aisle in 1900.

St. Bart's is also associated with Henry Webber (1849–1916), a former churchwarden and founding member of what is now Horley Town Council and Surrey County Council. At the age of 67, he is believed to have been the oldest man to die on the Somme during World War I, having joined his sons on the front line despite his age.

In 2018, the parish commemorated 800 years of established clergy at the Church Road site, highlighting its longstanding presence in the community.

Today, St. Bartholomew's continues to serve as a vibrant center for worship and community activities, maintaining its historical legacy while adapting to contemporary needs.

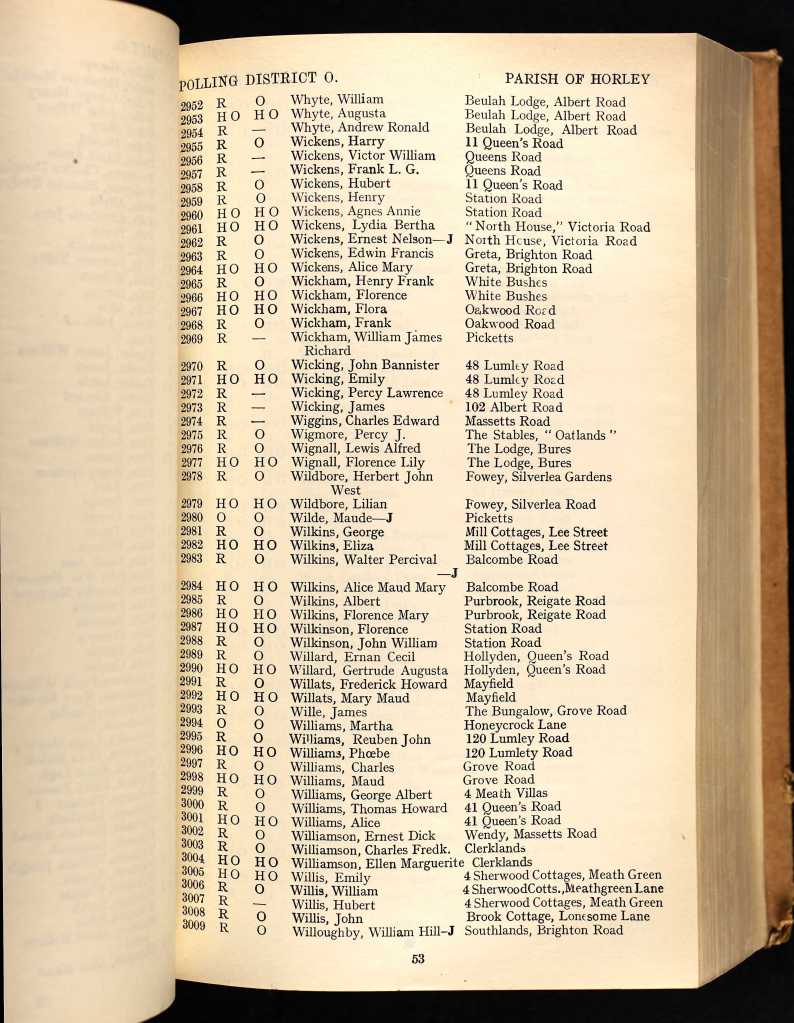

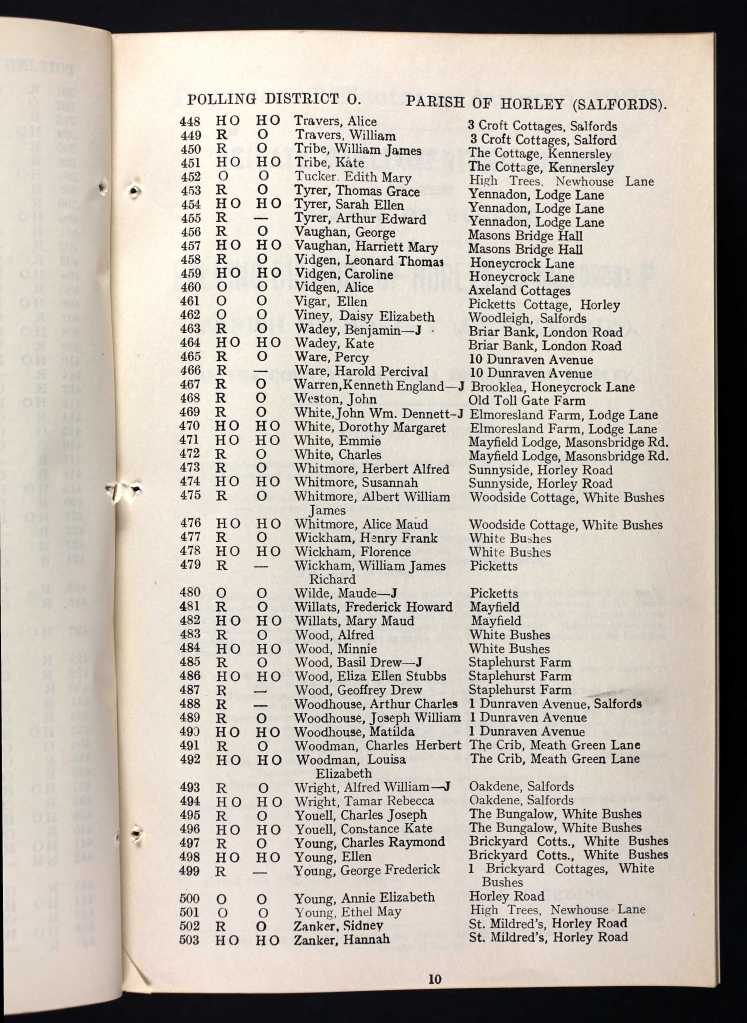

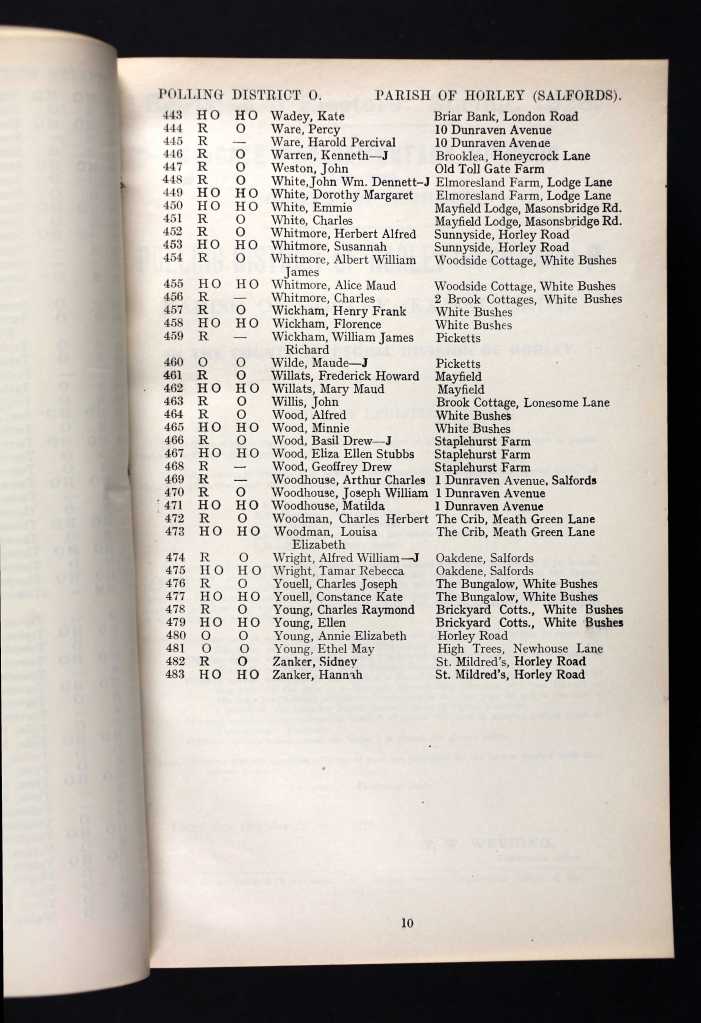

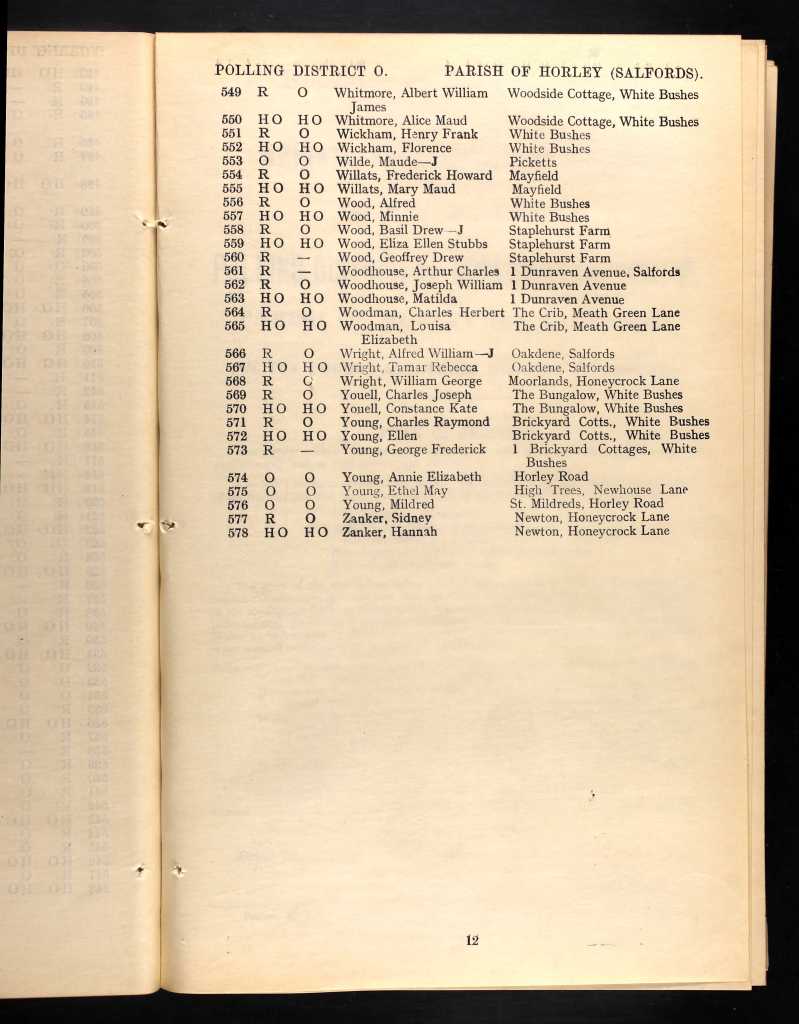

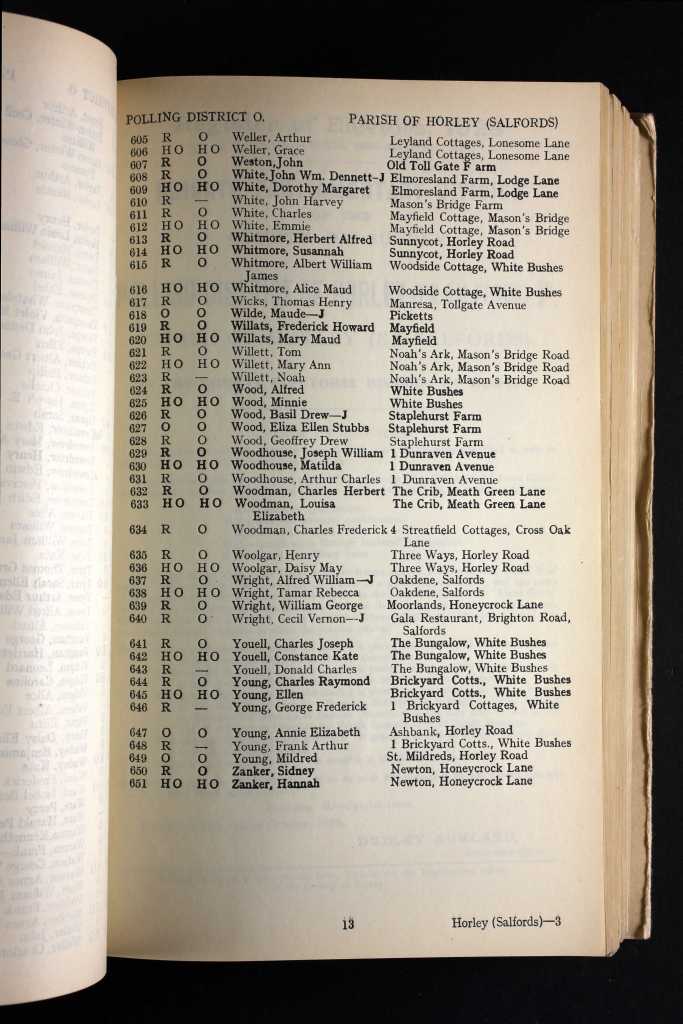

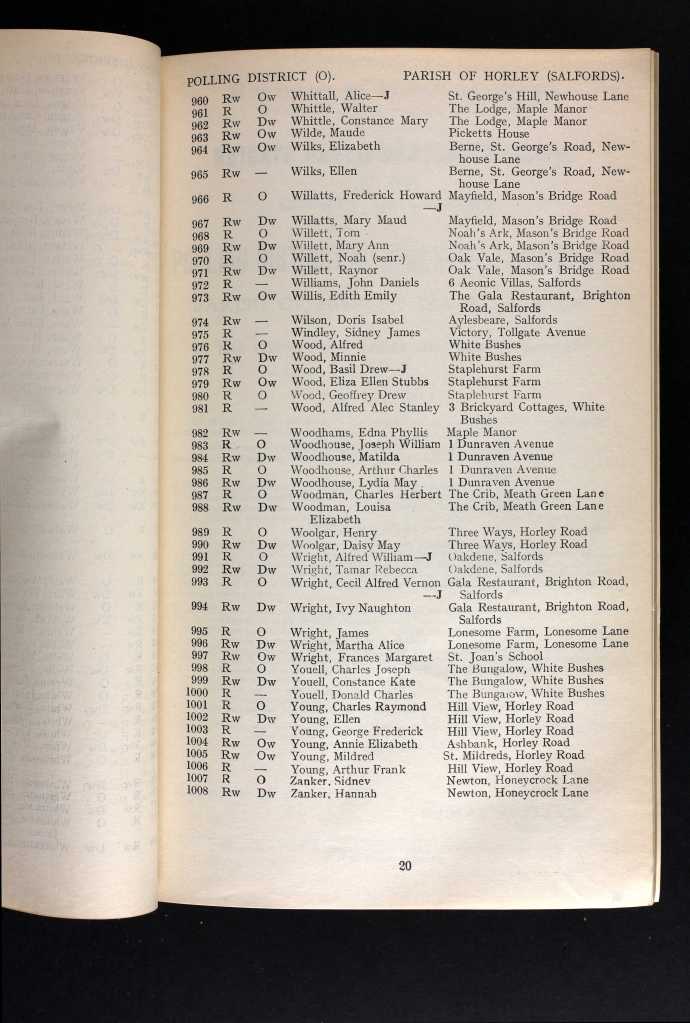

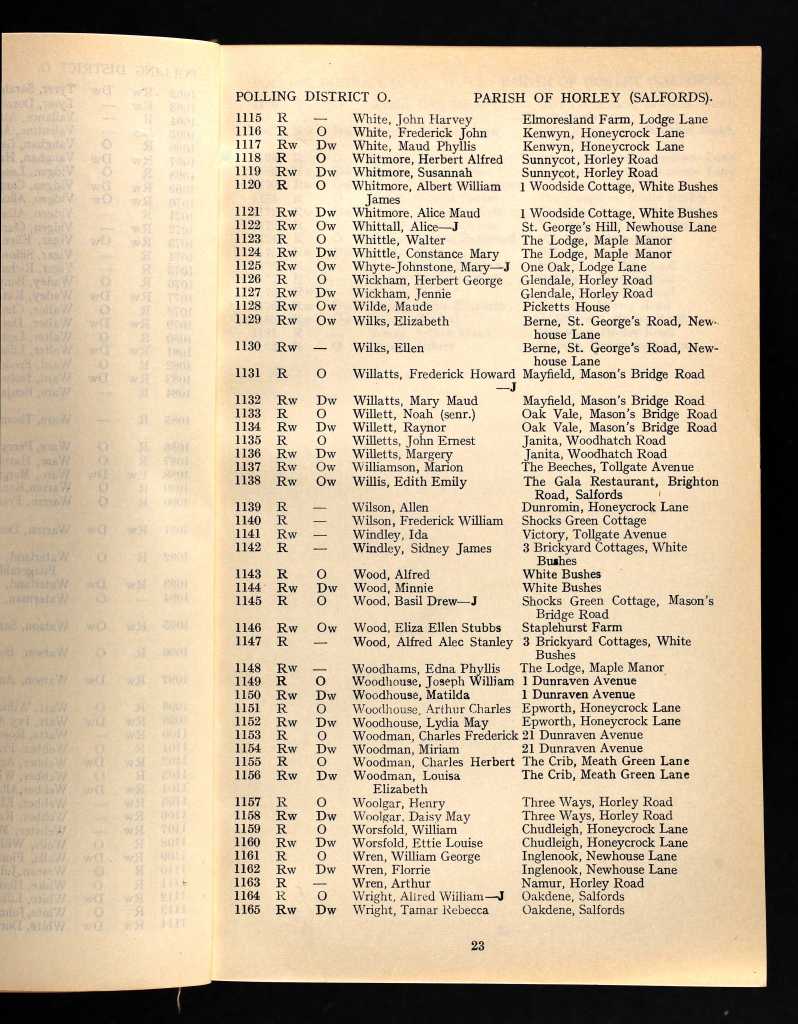

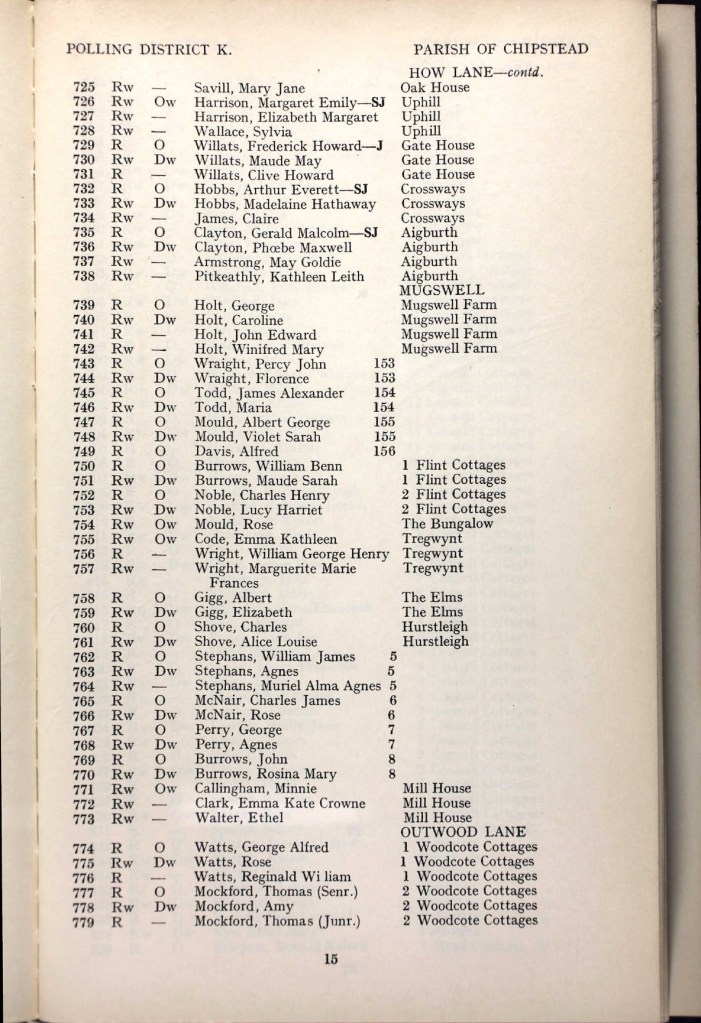

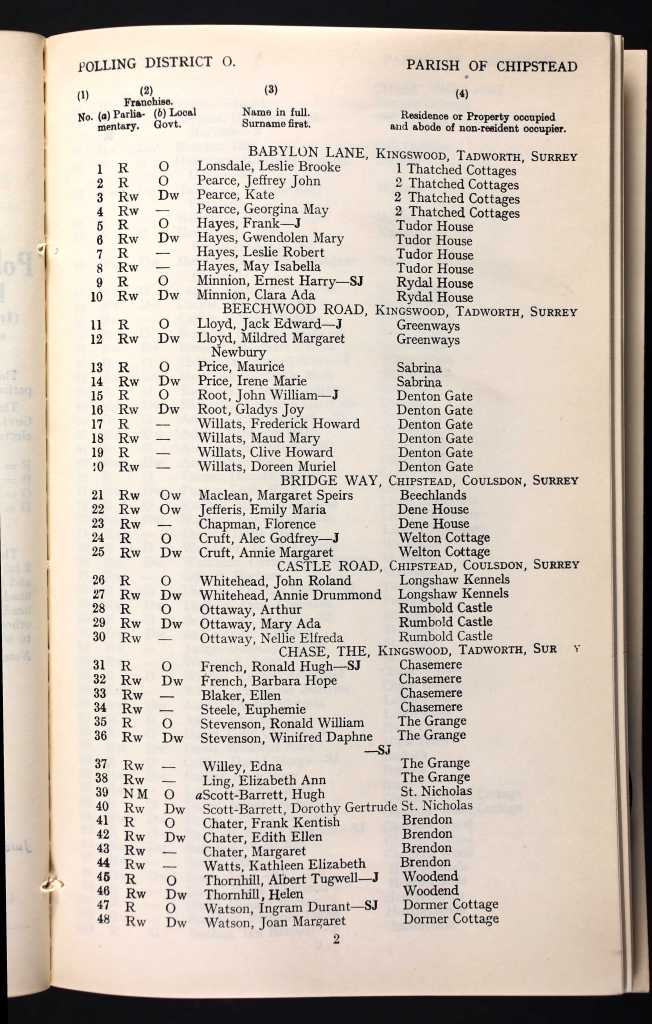

The two 1925 Surrey, England, Electoral Registers, one for polling district O and the other from polling district N, confirm Frederick and Maud, were still residing at, Mayfair, Mason Bridge Road, Horley, Surrey, England, in 1925.

Maud was once again listed under the name, Mary Maud.

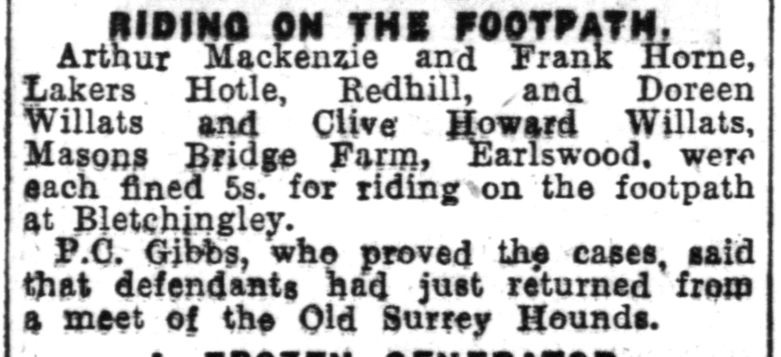

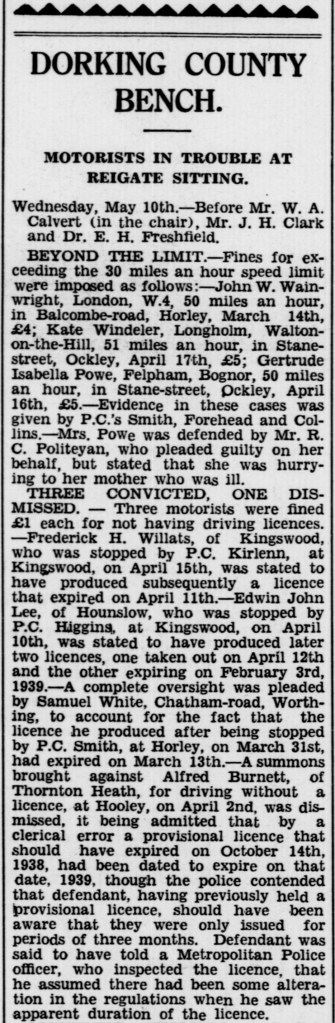

On the 24th day of December, 1926, the Kent & Sussex Courier carried an amusing yet slightly troubling mention of Frederick and Maud’s children, Clyde and Doreen. The article described an incident where the two siblings, along with others, found themselves in a bit of trouble in Bletchingley.

The report stated that Clyde and Doreen, along with Arthur Mackenzie and Frank Horne, had been riding on the footpath at Bletchingley, an offense for which they were each fined 5 shillings. At the time, they had just returned from a meet of the Old Surrey Hounds, a popular fox hunting group. The officer who proved the case, P.C. Gibbs, described the event, bringing attention to the youthful misstep of Clyde and Doreen, who were no doubt enjoying the excitement of the day.

While this moment might have been a source of embarrassment at the time, it also shows a lighthearted and mischievous side to the Willats children, a reminder that, even in a time of strict rules and expectations, they were still able to live with a sense of joy and adventure. Though it was a minor incident, it would have certainly been talked about within the family, perhaps with a few laughs, as they recalled how their children, despite their best efforts to stay out of trouble, were caught up in a harmless bit of youthful rebellion.

From the two 1926 Surrey, England, Electoral Registers, both for polling district O, we know Frederick and Maud, were still residing at, Mayfair, Mason Bridge Road, Horley, Surrey, England, in 1926.

Maud was once again listed under the name, Mary Maud.

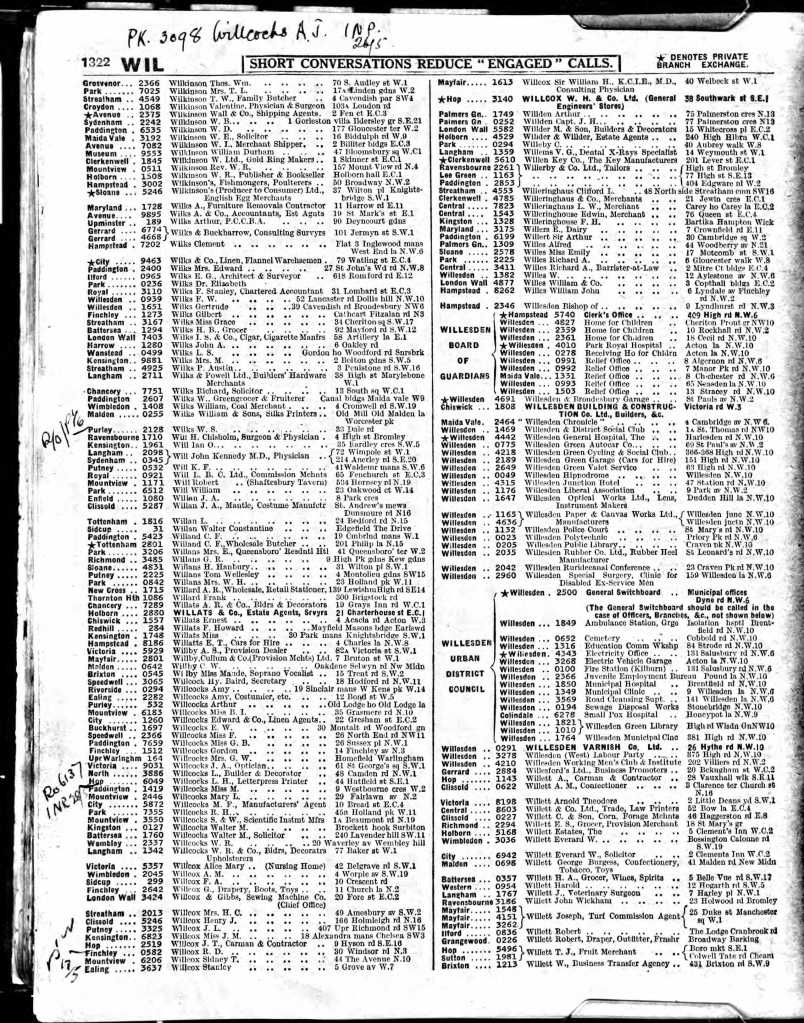

In 1926, the records from the 1880-1984 British Phone Books confirm that Frederick and Maud were residing at Mayfair, Mason Bridge Road, Earlswood, Surrey, England. This time, the address was listed with Earlswood instead of Horley, though both towns were so closely linked by proximity and community. It must have been a peaceful place for Frederick and his family to call home, away from the noise of the city but still with access to the world beyond.

What stands out from the listing is that Frederick’s phone number was listed as Redhill...284, a direct connection to the local area that must have felt like an essential link to the outside world, perhaps a lifeline for both business and personal matters. The phone number, though simple by today’s standards, represented a sense of modernity in a rapidly changing world.

The entry also mentions Willats and Co Estate Agents, Surveyors, under the address of Number 21, Charterhouse Street, Holborn, with a phone number of Holborn...2880. This was the professional side of Frederick’s life, a significant part of his identity as an estate agent and surveyor. Running a business in Holborn, one of the heartbeats of London, would have been both a challenge and an opportunity for Frederick, as he balanced his home life in the quieter countryside with the demands of the city’s professional world. The duality of his life, reflected in both the personal and business addresses, speaks to the hard work and determination Frederick put into both his career and family life, ensuring that he provided for those he loved, all while navigating the changing landscape of the early 20th century.

The 1927 Surrey, England, Electoral Registers confirms Frederick and Maud were still residing at Mayfair, Mason Bridge Road, Horley, Surrey, England in 1927. Maud was listed under the name Mary Maud.

And so does the 1928 Surrey, England, Electoral Registers.

In 1929, the Willats family was struck by yet another profound loss. Frederick’s brother, 64-year-old Walter James Willats, a stockbroker by trade, passed away on Friday, the 29th day of March, 1929, at his home at Number 163 Camden Road, St Pancras, London. Walter’s passing was due to a combination of Myocarditis, Bronchitis, and Cardiac Failure, leaving a heavy sorrow upon the family who had already endured so much.

Walter’s death marked the end of an era for the Willats siblings, as he was a figure of resilience in the family, navigating the complexities of his profession and personal life. His nephew, P. Champion, who was living at the same address, was with him in his final moments and took on the solemn responsibility of registering Walter’s death on the 2nd day of April, 1929, in St Pancras, London.

Though Walter had lived through many challenges, his passing left an undeniable hole in the Willats family, a loss that would ripple through the years. At present, Walter’s final resting place remains unknown, adding to the mystery of his life and death. Perhaps his family found comfort in knowing he was surrounded by loved ones in his final days, but still, the grief of losing him lingered deeply within the hearts of those who had known and cared for him.

For those who remember him, the memories of Walter, the brother, the stockbroker, the uncle, are cherished and bittersweet. It was a loss that would have been felt by his siblings, including Frederick, and his extended family, and one that left a void that would remain as they continued to endure the trials of their lives.

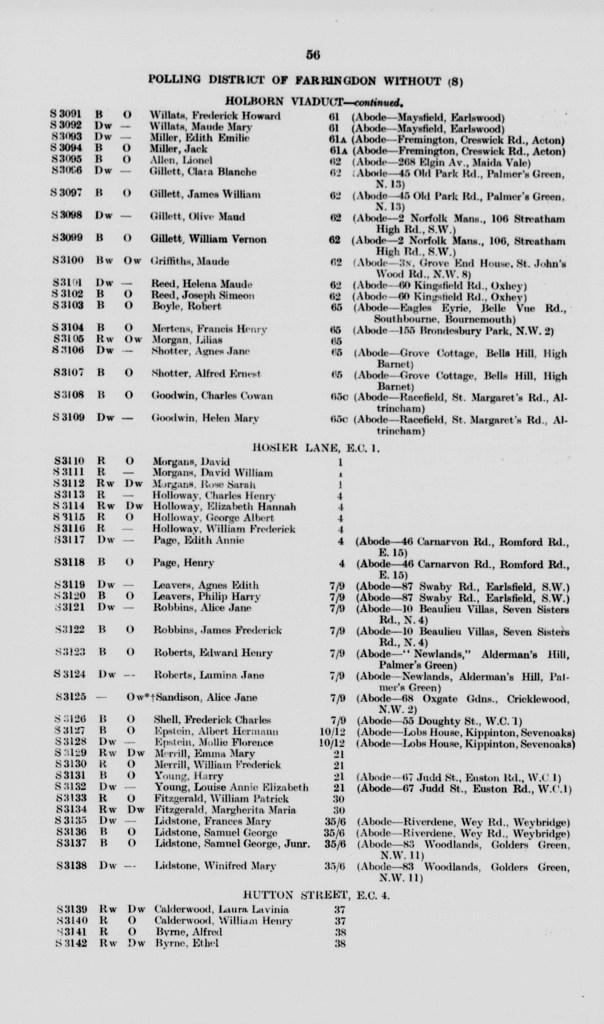

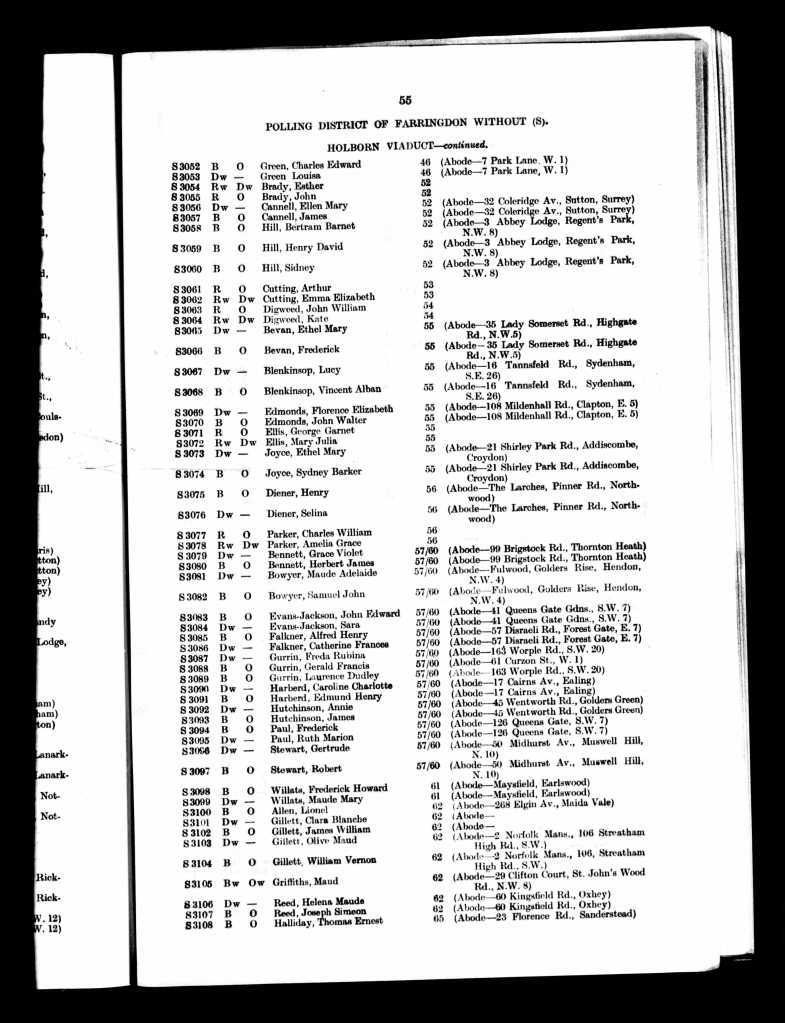

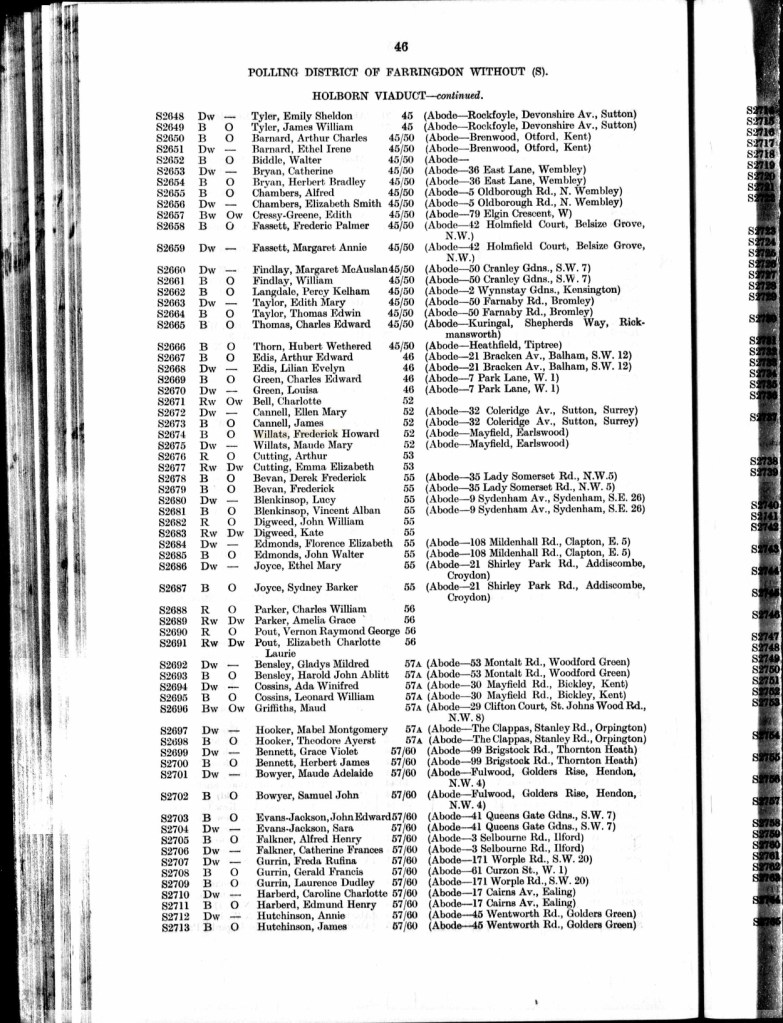

In 1930, the Electoral Register reveals that Frederick and Maud had a non-residential address at Number 61 Holborn Viaduct, Farringdon, London, England. This location, nestled in the heart of London, was part of the professional side of their lives. It may have been connected to Frederick's work, perhaps a place where he conducted business, met clients, or maintained some presence in the bustling city.

At the same time, the couple's home was listed as Number 61 Maysfield, Earlswood, London, England. This address, in the quieter surroundings of Earlswood, was where their family would have found comfort and solace. The contrast between the two addresses, a busy urban location in Holborn Viaduct and a peaceful residential home in Earlswood—speaks to the balancing act of their lives. While they had to navigate the demands of city life and business, their hearts remained with their home, where they could retreat to the peace and familiarity of family.

For Frederick and Maud, it must have been a unique time. They were clearly rooted in both worlds, anchored by family, but also reaching out to the broader world of work and opportunity. The non-residential address may have been a reminder of their professional commitments, but it was the warmth and stability of their home in Earlswood that provided the foundation of their lives.

The 1930 Surrey, England, Electoral Registers, confirmes that Frederick and Maud, were residing at, Mayfair, Mason Bridge Road, Horley, Surrey, England, in 1930.

Maud was listed under the name, Mary Maud.

So does the 1931 Electoral Register.

And The 1932 Surrey, England, Electoral Registers, also shows Frederick and Maud, were still residing at, Mayfair, Mason Bridge Road, Horley, Surrey, England, in 1932. Maud was listed under the name, Mary Maud.

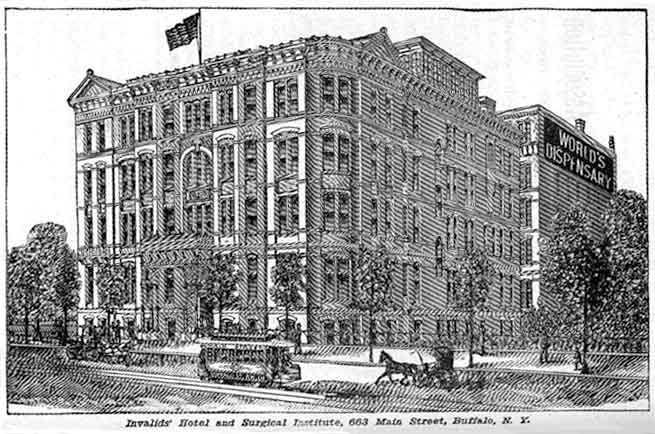

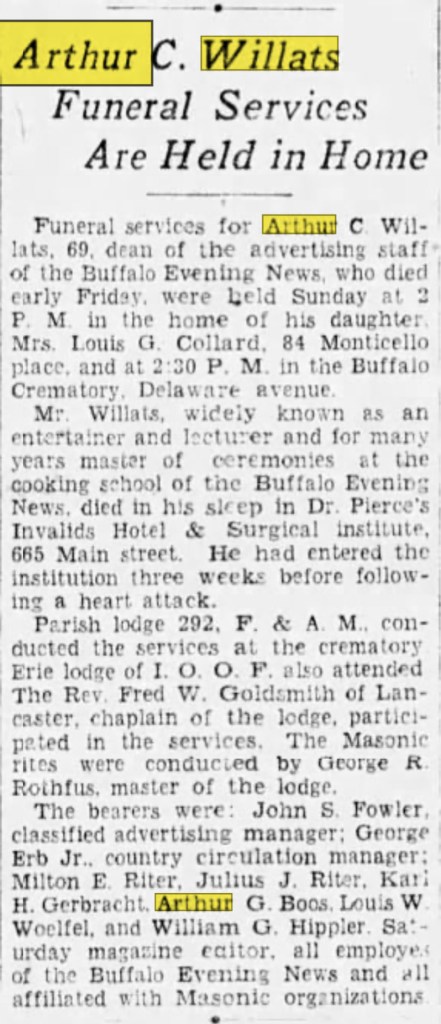

Heartbreakingly, Frederick’s beloved brother, Arthur Charles Willats, passed away on Friday, the 2nd day of June, 1933, at the age of 69. Arthur’s death left a profound emptiness in the hearts of those who knew him, not only in his family but within the wider community that had admired his life and work. He passed away from a heart attack at Dr. Pierce’s Invalids Hotel and Surgical Institute, located at 665 Main Street in Buffalo, Erie, New York.

Arthur’s journey through life had been rich with passion and purpose. A former Shakespearean actor, he had once graced the stage with his performances, capturing the hearts of many with his talent. As he made his way to Buffalo at the age of 17, his journey continued with a long-standing career as a lecturer and a newspaperman. He had spent decades enriching others' lives, first through his work at the Buffalo Cyclorama and later as a staff member of the Buffalo Evening News for 40 years. In more recent years, he even extended his reach through radio, sharing his insights and knowledge with a new generation.

Arthur’s passing was not just the loss of a brother to Frederick, but the loss of a figure who had touched so many lives. His contributions, his spirit, and his personality will always be remembered by those who were lucky enough to have known him. The Niagara Falls Gazette paid tribute to his remarkable life in an article on the day of his passing:

*"ARTHUR WILLATS DIES – Buffalo Newspaperman, Lecturer, Former Actor Succumbs to Heart Attack."*